Abstract

The challenges faced by parents raising children with cerebral palsy (CP) have been well explored in the literature. However, little attention has been paid to the experiences of parents raising children with CP in low-income countries, such as Ghana. Objective: Therefore, the objective of this study was to explore parents’ experiences of raising children with CP, specifically focusing on the relationships between spouses and between children with CP and their typically developing siblings. Method: Qualitative semi-structured interviews were conducted with 40 parents, who were purposively selected from the largest tertiary hospital in Ghana. Results: The results revealed that typically developing children accept their siblings with CP as their equals and even take up domestic responsibilities to lessen the burden on their parents. However, the parents reported experiencing marital and extended family conflict, financial burden and negative attitudes from spouses, resulting in family tensions. Conclusion: The implications of these findings for policy-making have also been discussed.

Keywords: Relationship, siblings, cerebral palsy, family, Ghana

Introduction

Cerebral palsy (CP) is a non-progressive syndrome of posture and motor impairment that results from an injury to the central nervous system (Koman et al. 2004). The global prevalence of CP is estimated at 1–3.5 per 1000 live births (Bulekbayeva et al. 2017). CP diagnoses are generally definitive and vary from one child to another. CP usually manifests in early childhood and affects motor and cognitive functioning, resulting in mild to severe impairment. For e.g. CP may be associated with speech, language, feeding, oro-dental, visual, cognitive, hearing, and behavioral impairments. It is also the most common cause of severe physical impairment in childhood (McAdams and Juul 2011). Although much is known about parents experiences of the burden associated with the caregiving of children diagnosed with CP in high-income countries, in low-income countries such as Ghana, family experiences are seldom reported (Dan and Paneth 2017). In the Ghanaian context, because of the existence of attitudinal, institutional, architectural, transportation, and information barriers against individuals with disabilities (Anthony 2011, Naami 2014, Opoku et al. 2017a, 2018), there is an intense advocacy campaign aimed at promoting the acceptance of children with disabilities at the family and societal levels. However, there is a paucity of empirical research on the impact that having a child with CP has on family relationships.

The importance of family relationships to a child’s development cannot be over emphasized. Family relationships influence children’s development across their lifespan (Hoffnung et al. 2016, White et al. 2016). Parents possess requisite life experiences and resources to shape the development of their children. Parents determine the rules at home and influence their children’s life path (Hoffnung et al. 2016). Most importantly, the ability of parents to provide for their children’s basic needs impacts significantly on family relationships (Hoffnung et al. 2010). Therefore, supporting parents has the propensity to lower tensions as well as create an enabling environment for children to develop their potential. Moreover, the relationship between siblings has been identified as a source of social support and as a primary source of companionship, friendship and mentorship to each other (Hoffnung et al. 2016). As such, it has been established that the number of siblings does not correlate with parental stress (Rentinck et al. 2006). For e.g. older sisters serve as role models to younger ones, as they help them with problem-solving and socialization within the larger community (Hoffnung et al. 2013). When a child is diagnosed with a disability, such as CP, parents may look to typically developing siblings for caregiving assistance and emotional support (Whittingham et al. 2011).

In this study, family refers to individuals who are related by blood or who share a common ancestry (Clark 1999). In Ghana, two family systems exist concurrently: nuclear and extended family systems (Aboderin 2004, Kpoor 2015). The nuclear family is made up of couples and children living together and providing for themselves. The extended family refers to all blood relations from the maternal and paternal lineages (Agyemang et al. 2018, Ofori-Dua 2014, Oppong 1977). Importantly, because of the culture of communality and collective responsibility in Ghana, the nuclear family is a sub-set of the extended family (Kutsoati and Morck 2014, Ofori-Dua 2014, Oppong 1977). Although many married couples live away from extended family members, they share responsibilities and the former regularly call on members of the latter for emotional and psychological support in times of adversity (Agyemang et al. 2018, Kpoor 2015, Oppong 1977). Children are raised to identify with both the extended and nuclear family systems. The culture of reciprocity also requires that children are taken care of so that they can grow to become responsible adults who can then take care of other members from either family (Clark 1999, Oppong 1977). While growing up, there is division of labor among children, the aim of which is to nurture them to become responsible. Specifically, older siblings are expected to support parents with household chores, such as cooking and taking care of younger siblings, sometimes even working to supplement the family income (Aboderin 2004, Kutsoati and Morck 2014). Therefore, every member plays a role in enhancing the well-being of the family.

Anecdotal evidence on Ghana suggests that children with disabilities and their families are victims of marginalization (Baffoe 2013). Disability is viewed as a curse inflicted upon children with impairments and their families or as punishment from heaven or ancestors for the sins of a family member (Anthony 2011, Baffoe 2013, Kassah et al. 2012, 2014, Opoku et al. 2015, 2017b). These deep-rooted negative convictions and attitudes about persons with disabilities and their family members impede their educational and social inclusion in society (Opoku et al. 2018). As a result, persons with disabilities receive limited support from family members and society to partake in life-improving activities such as education, training and employment (Naami et al. 2012, Opoku et al. 2017a). The barriers to their participation as equal members of society have contributed to extreme poverty among persons with disabilities (Opoku et al. 2018, Senayah et al. 2018).

International advocacy towards achieving inclusive societies seeks to promote and protect the rights of persons with disabilities to education, training, and employment (United Nations 2006). Determining family relationships and the experiences of rearing a child with CP is particularly important in a Ghanaian context, where there are pre-conceived supernatural and superstitious cultural beliefs about the causes of disability, resulting in negative attitudes towards children with disabilities and their parents (Baffoe 2013). Given the family-based expectations of children in Ghana (Clark 1999, Ofori-Dua 2014) and the functional limitations of children with CP (McAdams and Juul 2011), there is a need to understand the relationships among spouses, siblings, and children with CP so as to inform policy directions.

Parental experiences

Empirical studies have reported mixed reactions from parents in terms of their experiences of raising their children with disabilities. A few studies have reported positive caregiving experiences (Blacher and Baker 2007, Green 2007, Grossman and Gruenewald 2017, Myers et al. 2009, Omiya and Yamazaki 2017, Rajan and John 2017). For instance, some parents have intimated that the experience of raising children with disabilities has been a source of strength and encouragement to them and has enabled them to value life (Green 2007, Myers et al. 2009). Others have indicated that the difficulties they face in attending to the needs of their children have made them resilient and helped them develop a thorough understanding of humanity and service. Thus, the success stories of some parents regarding raising their children with disabilities could be shared with others who are struggling so as to lessen their burden and to develop positive attitudes towards raising their children with disabilities (Kimura and Yamazaki 2016, Zuurmond et al. 2019). Sharing such information could perhaps equip them with useful information to support their children to overcome the many barriers they encounter.

Many studies have documented the considerable challenges faced by parents of children with CP (e.g. Cheshire et al. 2010, Eker and Tüzün 2004, Garip et al. 2017, Hiebert-Murphy et al. 2011, Khayatzadeh et al. 2013, Kuo and Geraci 2012, Ludlow et al. 2012, Navarausckas et al. 2010, Tseng et al. 2016). In Ghana, as well as other contexts, some of the challenges encountered by parents of children with disabilities include marital conflicts; higher stress levels; time pressures when implementing positive parenting strategies; and increased daily parenting tasks, such as conducting therapy exercise, administering medication, providing assistance with mobility, and organizing equipment and appointments (Hiebert-Murphy et al. 2011, Polack et al. 2018, Rentinck et al. 2006, Whittingham et al. 2011, Zuurmond et al. 2018, 2019). Parental stress has been found to be influenced by the presence of behavior problems in children with CP, the number of hospitalizations and the low socio-economic status of parents (Rentinck et al. 2006). These challenges have contributed to discussions on ways to improve the living conditions of parents and their children with CP. For instance, it has been found that the higher the income of parents, the more they are satisfied with their marriage, the higher their quality of life, and the lower their stress levels with respect to caring for their children with CP (Khayatzadeh et al. 2013). Unfortunately, in Ghana many children with disabilities and their families are usually poor and are rarely supported (Naami et al. 2012, Opoku et al. 2017a). In Ghana, more recent studies have reiterated the importance of caregiving training on the well-being of parents and on improving child nutrition and health. However, this training may not be available to all parents and typically developing siblings.

Due to the barriers encountered by parents of children with disabilities, suggestions have been made for them to rely on informal social support from typically developing children, relatives, society, and other parents who have children with similar conditions (Button et al. 2001, Tseng et al. 2016, Zuurmond et al. 2019). Such social networks and satisfaction with social support are found to be positively related to improved parental mental health (Rentinck et al. 2006). It is believed that in times of adversity, close relatives, and members of society will encourage and provide them with emotional support. However, little seems to have been done to educate society about the contributions they can make towards raising children with CP. This is as a result of the isolation, marginalization and discrimination perpetuated against the parents of children with CP, who have to shoulder all caregiving burdens (Huang et al. 2010, 2012, Zuurmond et al. 2019). Due to societal exclusion, parents are unable to work, as they have to devote their time entirely to care for their children with CP. Consequently, some parents are unable to earn money to supplement the income of the other spouse (Brehaut et al. 2004, Davis et al. 2010, Glasscock 2000, Huang et al. 2010). Because of limited social support and the drain on family income, parents struggle with caregiving, which sometimes creates tension in the home (Huang et al. 2012). Moreover, due to the inability of parents to acquire the requisite skills to raise children with CP, they are at risk of stress and poor health outcomes (Garip et al. 2017, Pimm 1996, Polack et al. 2018; Tseng et al. 2016; Zuurmond et al. 2018). It is vital for policy-makers to devise means of supporting parents to overcome these challenges.

Although the parents of children with CP encounter several barriers and poorer health outcomes, the contribution of typically developing children towards the development of their sibling with CP has received some attention in the literature (Dew et al. 2008, Kuo and Geraci 2012). For instance, while parents appear to have negative attitudes towards raising children with disabilities, siblings seem positive about living with a brother or sister with a disability (Dew et al. 2008). Since children with CP rarely display social interaction (Dallas et al. 1993), they need continuous assistance and peaceful homes to acquire basic skills for independent living. Interestingly, positive interactions between typically developing siblings and children with CP improves the rehabilitation of the latter as they demonstrate improvements in basic life skills (Craft et al. 1990). This highlights the need for understanding between siblings to enable them to support each other. Additionally, in an Australian study, Dew et al. (2014) found that the ability of typically developing children and their siblings with CP to live and grow up together does impact their future relationship. Typically developing siblings continue to perform parental roles and support their brothers or sisters with CP. This means that creating a peaceful co-existence between siblings and children with CP can impact future relations and support. In a similar qualitative study in Australia, Mophosho et al. (2009) found that though typically developing siblings had a preference for children with CP to be able to play with them and actively engage in the activities they performed, they showed them love and continued to protect their sibling with CP. Thus, when given the appropriate training and caregiving strategies, children can support their sibling with CP in overcoming barriers.

It has also been reported that children with CP have a negative impact on their siblings. For example, studies have reported that the presence of a child with CP affects the relationship between parents and typically developing siblings (Craft et al. 1990; Huang et al. 2010, Louis and Kumar 2016, Navarausckas et al. 2010). In particular, typically developing siblings have to grow up on their own, as they take control of their lives without depending on their parents (Huang et al. 2012). Due to the enormity of the work involved in caring for a child with CP, typically developing siblings have little time to share their experiences with their parents (Huang et al. 2010). Elsewhere, other studies have reported that siblings are rarely involved in the lives of children with disabilities, making it difficult to support them (Harland and Cuskelly 2000, Kuo 2014). The preoccupation of parents who are caring for children with disabilities while sidelining their siblings sometimes contributes to aggressive behaviors among the latter (Ross and Cuskelly 2006). These studies, however, were conducted in predominantly high-income countries, where there are social support structures to promote the rehabilitation of children with CP. According to Dan and Paneth (2017), despite the high prevalence of children with CP, little attention has been paid to their welfare in low-income countries. In low-income contexts, such as Ghana, it is necessary to understand the attitude of typically developing siblings towards children with CP so as to ascertain ways to facilitate their acceptance in society. The study draws on interviews with the parents of children with CP, sharing their views about their relationship with their spouses as well as that between typically developing children and their sibling with CP in Ghana.

Methods

Study participants

The data for this study were collected at the main pediatric neurology clinic within the Korle-Bu Teaching Hospital in Accra, the capital of Ghana, from November 2013 to April 2014. This hospital is the largest tertiary hospital in the provision of specialist care in the country. The study sample included parents of children diagnosed with CP attending the neurological clinic at the Korle-Bu teaching hospital. Purposive sampling was used to select 40 participants for the study. This sampling technique was adopted because it allowed for the flexibility of selecting parents who have children with CP. The selection criteria were based on the following: the parent is the primary caregiver of the child with CP attending the clinic; the child has a sibling and is less than 18 years old; the child has been formally diagnosed with CP; and the parent is willing to provide consent to participate in the study. Participants were excluded if they did not have other children; were unable to visit the hospital for treatment, and if the child with CP was 18 years or above.

Study design and approach

A descriptive qualitative design (Babbie 2011) was adopted because we wanted to understand the relationships between spouses and between children with CP and their siblings in Ghana. To address the objectives of the study, a semi-structured interview guide was developed from the literature (e.g. Craft et al. 1990, Dallas et al. 1993, Glasscock 2000, Kuo and Geraci 2012, Ross and Cuskelly 2006) for the data collection and face-to face interviews were held. The issues covered in the interview guide included the relationship between spouses, the impact of the diagnosis of a child with CP on families, and the relationship between siblings. The first author kept a fieldwork journal to document observations made during the interviews and to reflect on personal experiences during the data collection process that might affect the validity of the data.

Data collection tools and procedure

The study and its protocols were approved by the Committee on Human Research, Publication and Ethics (CHRPE) of the School of Medical Sciences, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST), the Komfo Anokye Teaching Hospital (KATH) Institutional Review Board, and the Head of Department of Child Health, Korle Bu Teaching Hospital, Accra. The clinical records of the prospective participants were reviewed by the authors to ascertain proof of diagnosis. The list of prospective participants who satisfied all the inclusion criteria was given to the hospital administration, who contacted them on our behalf. A list of parents who agreed to take part in the study was then given to us for follow up. We then sent invitations to the parents through calls and text messages. Arrangements were made for data collection on clinic days during the study period. Sixty-three parents were contacted, but 23 were excluded either because their child with CP did not have siblings or because they did not consent to participate.

On the days of the interviews, after the participants and their children were attended to by health professionals, they were ushered into an office, where the interviews were conducted. The study objectives were discussed with the caregivers and the researchers informed them of the potential risks and benefits of the study. They were informed that sharing their experiences could impact their psychological well-being. The participants were then counselled to mitigate those effects. They were assured that they had every right to withdraw from the study without any consequences and that their identity would remain anonymous throughout the reporting of the findings of the study. Each participant signed a written consent form prior to the interviews, which were recorded with an audiotape and lasted between 30 min and an hour.

Data analysis

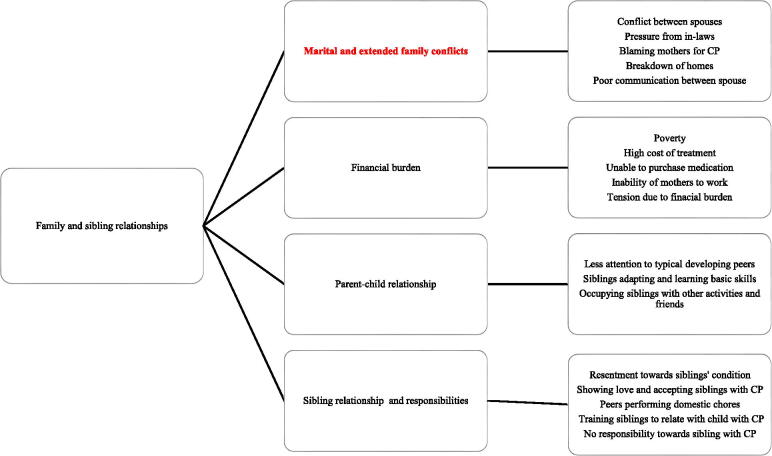

The second author transcribed all the interviews and placed calls to thank the participants and to discuss key issues emerging from the data. All participants were given the chance to clarify issues discussed and to consent to the use of their data in this study. We performed a thematic analysis according to the following guidelines: reading, coding and developing the framework, sorting and mapping, categorization, and writing the report (Babbie 2011, Creswell and Guetterman 2015). We read the interviews to become familiar with the content and later discussed the key themes emerging from the data. These themes, as well as themes developed from the literature, were used as a priori themes (see Figure 1). To elaborate on the guidelines, the first and second authors coded two interviews and met to discuss the codes assigned to their interviews. Where there was disagreement, we discussed until we reached a consensus on the final content. The remaining interviews were coded by the first author, who developed a coding framework. The codes were then sorted under the a priori themes. The differences and similarities between the codes were noted and discussed among the authors. The second author then extracted texts and developed the story line. The first draft was written and reviewed by the authors for a consensus opinion, after which the final draft was written.

Figure 1.

Coding structure derived from the thematic analysis.

Results

Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the study participants. Overall, 40 primary caregivers took part in the study, of which 87% (n = 35) were female and 12.5% (n = 5) were male. The majority of the participants (60%, n = 24) were aged between 30 and 40 years; many participants (40%, n = 16) had a junior high school qualification; most participants (75%, n = 30) were married at the time of the interview, and 20% (n = 50) of the caregivers interviewed were self-employed.

Table 1.

Distribution of demographic characteristics of participants.

| Category characteristics | Frequency (N = 40) | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 5 | 13 |

| Female | 35 | 87 | |

| Age | 20–30 | 5 | 13 |

| 30–40 | 24 | 60 | |

| 40–50 | 8 | 20 | |

| 50–60 | 3 | 7 | |

| Highest level of education | Tertiary | 7 | 18 |

| Diploma/certificate | 9 | 22 | |

| Senior high | 8 | 20 | |

| Junior high | 16 | 40 | |

| Occupation | Formal employment | 10 | 25 |

| Self-employed | 20 | 50 | |

| Unemployed | 10 | 25 | |

| Marital status | Married | 30 | 75 |

| Divorced | 1 | 3 | |

| Separated | 3 | 7 | |

| Widow | 1 | 3 | |

| Single | 5 | 13 | |

| Relationship of caregiver to child | Mother | 32 | 80 |

| Father | 5 | 13 | |

| Grandmother | 3 | 7 | |

Marital and extended family conflicts

Thirty of the 40 (n = 75%) participants in the study reported that some conflicts in their marriages arose after their child was diagnosed with CP. Almost all the mothers complained about negative attitudes from their husbands and extended family members towards them. It emerged that the mothers were blamed for the conditions of their children, hence the resentments towards them. While some said that their husbands continued to cater for their children, others said that they had been abandoned, receiving no support from their husbands. Some participants recounted as follows:

He left us. He just left home and never returned. He abandoned his responsibilities and blamed the condition on me since I carried the baby. I moved to my parent’s house so I could get a helping hand with ‘D’. (Mother V)

I ‘lost’ my husband the moment I gave birth to him (child with CP). He is now the one financing the child’s welfare but wants nothing to do with me anymore. (Mother Q)

As Christians, we understand that god gave us this child. So I always encourage my wife to be strong and trust god for everything. I always praise god and thank him for giving us this child… I don’t fight with my wife. (Father B3).

A few participants recounted that the amount of time, energy, and finances required to cater for their child with CP usually resulted in tension and conflict at home. Others reported that this gave them little or no time to spend alone as couples.

It is a very difficult situation when it comes to the relationship. There is virtually no ‘us’ anymore because you don’t have a normal life as you and your husband. Our routine conversations are now all about ‘P’. Sometimes, I think about what he (husband) would be going through. As a mother, I have gotten used to the caregiver role. He helps a lot, but I take the lead and he just follows. I think in this situation, you either ‘gel’ or you fall apart as a couple. (Mother X)

Many participants recounted that family tensions are not limited to their nuclear families but also included their extended families. While the fathers talked about acceptance of their children by their families, the mothers said that their in-laws urged them to kill their children. Their refusal to do so has contributed to strained relationships between them and their in-laws.

…I had witnessed what they did to children with abnormalities in our community. After some time, my father called me again, this time with my husband and insisted that the ritual be done and that it was a taboo to keep such a child in the family. He said the ritual was long overdue. Two nights after that meeting, my husband helped me pack my belongings and sneaked me to the station to take a bus with our two children and leave. I have not set foot in my community in Town X since then. My husband visits when he can. (Mother U)

My mother in-law also realized this. It was after this event that her attitude towards me changed. She had been helpful with the two other children I had, but after realizing Baby K had some abnormality, she distanced herself and informed other family members about the condition. One day, she commented that the way Baby K was behaving, it could happen that I had given birth to an ‘nsumba’ (river child in Fante). Days after that comment was made, she told me that it was an embarrassment to have such a child in the family. (Mother E)

Financial burden on families

When asked about the financial effect of caring for the child with CP, all 40 (100%) participants admitted that it had a huge toll on them. They all complained of the high cost of medication, since they were not covered by the National Health Insurance Scheme. Some participants explained that rehabilitation falls outside the treatment coverage of health insurance. This means that all costs associated with health care and medication are an out-of-pocket expenditure for these parents. A few participants also complained about the unavailability and cost of equipment, especially wheelchairs for their children. Some caregivers with toddlers also noted the prohibitive cost of assistive devices, making them inaccessible.

There are about three medicines the doctors always prescribe for him, but none is covered by the health insurance. I have to buy these medicines every month. The hospitals also do not provide assistive devices to help them move. If I need it, I will have to go and get it myself, but I cannot afford it. (Father B1)

Almost all the participants maintained that caring for a child with CP has negatively impacted their finances and their ability to provide for other family members. It emerged that they spend considerable amounts of money on transportation to health facilities, medicine, and health-related costs. Some female participants revealed that they were unable to work to supplement the family income.

I must admit it is a very difficult situation for the family especially when it comes to finances. As the father, this major task is on me, as the mother is unable to work because she has to take care of our sweet daughter. I am only a young graduate who found a job and just got married a little over a year ago. I must say, I have spent all my savings on our daughter’s care. I have sold my car and now take public transport just to be able to afford the care for her. (Father B3)

The district general hospitals do not have this kind of clinic, so we have no option but to travel the distance to access it and it is even more costly when we have to charter a vehicle because most public vehicles will not let you board their vehicle when you have a child with such a condition. The other children are suffering because we don’t have much to support them. (Mother B)

Some participants discussed that the astronomical financial expenditure in catering for a child with CP has led to tension in the home.

It’s not easy being the only financial provider. I’m not working and my husband gets annoyed when the bills are going up. I know that’s not how he is. He behaves like that out of frustration. He spends a lot of his earnings on him. (Mother M)

We can’t give our children the happy life that we aspired to. Now the financial commitment is too much for us. No one will help us, so we have to channel most of our resources to caring for her. There are things they need to be happy, but we are unable to provide for them as parents. (Mother C)

Effect on parent-child relationships

The participants agreed that the birth of their child with CP affected their relationship with their other children. They mentioned a tendency to devote less parental attention to their typically developing children, as their child with CP made extreme demands on their time and energy. Three participants shared their experiences with the following comments:

After ‘J’ dropped [was born], things changed. I think they appreciated my stress with ‘J’ and the fact that I always had to handle him. They’d rather ask to help me with ‘J’. I hardly had time and a good composure to play with them like before; I would be exhausted by the time they return from school. (Mother R)

Baby ‘K’ (child with CP) is almost always with me. Unfortunately, it makes the other two siblings feel neglected. My husband has been helping with them, but in a way, I have a feeling they are missing their motherly love. Now they call daddy more often when they need help. I’m missing out on their development. (Mother E)

The participants stated that as they did not have time for their typically developing children, these children tried to learn everything themselves. The children realized the situation and were able to adapt.

It was quite difficult for ‘P’ (typically developing sibling) as she was growing up. I cannot remember the day I taught her how to walk, talk, anything…. She learnt everything herself. With ‘P’, I think she was ignored a lot. She coped with the situation, while I was taking care of ‘N’ (child with CP). (Mother X)

The participants spoke about some of the strategies they adopted to keep their typically developing children occupied in order to make time for siblings with CP. Some recounted as follows:

I switch on the TV for them to watch so that they don’t disturb me. They could learn bad manners from TV, but that’s the only option I have. They want you to be part of their life, but that’s not happening in my home. (Mother I)

We have neighbors, so after school, I tell them to go and play with them. I don’t want them to be bored in the house; that’s why I allow them to go out to play with the other kids. There is so much agitating and crying when they refuse to go out. (Mother W)

Sibling relationships and responsibilities

The caregivers shared their perceptions on how the presence of a brother or sister with CP had impacted the sibling relationships. They reported that their ‘normal’ children demonstrated anger or resentment because of the condition of the child with CP, even though they often showed love, respect, and a preparedness to help their brother or sister with CP. They confirmed signs of sadness or depression in their children as a result of the impact of the child with CP on family life. Although siblings were unhappy to see their brothers and sisters suffer, they accepted them as equal members of the family. The descriptions below are expressions of depression or sadness in typically developing siblings, as recounted by two participants:

I pick up a lot of anger from the questions he (older brother) asks me about ‘J’ (child with CP). He (older brother) is angry because he cannot play with ‘J’ the way he wants to. He expresses a lot of frustration when questioning about his movement and I try as much as possible to explain the condition to him. (Mother R)

As children, and boys especially, most of their games involve running around the house, which is what ‘T’ misses whenever he wants to play with his brother. Sometimes, out of frustration, he would ask me repeatedly when his brother would be able to walk. I try to vary the answers I give him so that he doesn’t lose hope in his brother… this sometimes brings tears to my eyes because I know how he feels. (Mother S)

While some participants said that they have trained typically developing siblings on how to relate or play with their sibling with CP, few said they had not. Additionally, some participants shared that the presence of a child with CP had resulted in greater responsibility on other children. These siblings sense of responsibility for the brother or sister with CP was expressed as follows:

‘T’ (younger brother) is very protective of ‘K’ (brother with CP). There was a time when they were little and had gone on vacation. ‘T’ would join us at the hospital for physiotherapy sessions. When he met the nurses, he would say, ‘this is my brother, we have come here to exercise because he cannot walk’. Whenever we had the chance to go out together, he was always the one to introduce his brother and help push his wheelchair as well. Whenever he was given a gift or something personal, the next question after ‘thank you’ was always to ask for his brother’s. (Mother S)

Some participants recounted that their typically developing children now perform most of the household chores, such as cooking and washing, to allow them to cater for their sibling with CP, thus allowing them the time to support their children with CP. The following quotations represent parental extracts:

Oh, they do all the cleaning and dress themselves up for school. At times, I will be awake all night, since ‘N’ won’t sleep, so I will be sleepy in the morning. They won’t disturb me, since they know what I have been through. (Mother X)

I thank God for these kids because they have been good and very responsible. I travel almost every week, leaving them at home with their father. They don’t cause trouble and they help each other while I’m away. (Mother X)

Conversely, many parents discussed that they did not assign roles to siblings. The following quotations summarize the experiences of two participants:

I don’t allow the other siblings to support baby ‘K’. They may hurt him, so I have taken up such responsibilities while they perform other duties. Children can be rough at times and I have to protect him from them. It’s working for us. (Mother E)

They [siblings] can’t support him. I struggle to cater for him. I don’t want to get them involved because I see it as my duty. They are young and maybe one day when they grow up, they will support him. I’m satisfied with what they have been doing (being responsible) and how they have understood the situation. (Mother S)

Discussion

The family is the first agent of socialization and as such, a fluid relationship between family units has a meaningful impact on the inclusion of children with CP in society (Hoffnung et al. 2013, 2016). This study set out to explore parent’s experiences of raising a child with CP, with much focus on the relationships between spouses and between children with CP and their typically developing siblings. Interestingly, the participants revealed that while adults seemed to be grappling with the presence of children with CP within families, typically developing siblings appeared to accept them and showed them love with time.

The participant’s responses showed that there were tensions between spouses following the CP diagnosis of their children. This finding corroborates those of previous studies, which maintained that the presence of children with CP in families led to tension and confusion between spouses (Huang et al. 2012, Rentinck et al. 2006, Zuurmond et al. 2018). In this study, the tension was not limited to the nuclear family but transcended to the extended family. This tension between the participants and their in-laws can be attributed to the Ghanaian communal culture, whereby the nuclear and extended family share both the identity of individuals with disabilities and the responsibility to care for children with disabilities. Traditionally, children with disabilities have been regarded as liabilities and there is no expectation for them to grow up as responsible adults who can provide for other members of the family (Anthony 2011, Baffoe 2013, Opoku et al. 2018). The rejection of children with CP, especially by fathers and in-laws, can be attributed to negative attitudes towards children with disabilities in Ghanaian society, which is due to the cultural understanding of disability. Moreover, the birth of children with disabilities is perceived as a calamity, rending them unwelcome in many societies (Avoke 2002). It is unsurprising that some participants recounted that their husbands had left them after the birth of a child with CP. Similarly, in-laws began to distance themselves from the participants – disassociating themselves from the ‘disgrace’ associated with children with CP. Presumably, they were aware of the cultural consequences of having children with CP, propelling them to sever ties with the participants. It is possible that spouses, in-laws, and communities lack understanding of the principal causes of CP, which explains their reluctance to associate themselves with many participants. Many Ghanaians believe that disability is brought on by spiritual influences (Avoke 2002). Therefore, to foster an inclusive society, it is important for communities to be educated on the principal causes of disabilities so as to promote acceptance of children with CP as equal members of society.

The study also revealed some of the negative financial effects implied in having a child with CP in the family. Many participants recounted spending huge portions of their income on hospital visits and on purchasing medication. This finding partly corroborates those of previous studies, which highlighted that the presence of a child with CP has negative effects on family income (Brehaut et al. 2004, Davis et al. 2010, Glasscock 2000). In the Ghanaian context, having a child with a disability affects the relationship between parents and the larger community. Therefore, the participants might be unable to receive support from society because of their close association with their children. Although the extended family provides financial and emotional support to members (Oppong 1977), having a child with a disability may deny parents such assistance. Specifically, despite the existence of informal social networks in Ghanaian communities, where people share food, problems, and responsibilities (Kpoor 2015, Ofori-Dua 2014), parents of children with CP may not benefit from this form of support. This is because families with such children are described as cursed and are usually isolated from society (Anthony 2011, Avoke 2002, Kassah et al. 2012). This tends to place all the burden of caregiving on one spouse, who must work to earn income to sustain the family. It is unsurprising that some participants narrated that their husbands developed negative attitudes towards their children because all their earnings were being spent on medical expenses.

The cordial relationship between children with CP and their siblings was also discussed by many participants. They recounted that typically developing siblings recognized children with CP as equal members of the family. Most importantly, the participants narrated that siblings wanted to involve children with CP in play and other social activities. However, they were annoyed and resented the impact of the impairment on their sibling’s capabilities. This finding is consistent with those of previous studies, which reported on the acceptance and willingness of the siblings of children with CP to support the latter in acquiring daily living skills (Dew et al. 2014, Mophosho et al. 2009). This finding appears to reinforce the need to expose typically developing children and children with disabilities to each other. For e.g. inclusive education has been trumpeted as one of the means through which children with disabilities and typically developing peers could co-exist (Opoku et al. 2015, 2018). Perhaps, typically developing siblings might eschew the negative attitudes towards children with disabilities, accepting them as equal members of society and embracing a willingness to assist them in acquiring basic living skills. Siblings might offer protection to children with CP and advocate for their participation in society. Moreover, in an attempt to create an inclusive society, policy-makers could explore ways to involve the siblings of children with disabilities in policy-making.

In the study, it emerged that siblings took on some responsibilities at home to enable their parents to care for children with CP. Although some participants recounted their inability to perform their parenting roles, the siblings of children with CP were prepared to lessen the burden on their parents by performing household chores. This finding is consistent with those of previous studies, which reported that siblings of children with CP play a vital role at home in enhancing the caregiving experiences of parents (Craft et al. 1990, Kuo and Geraci 2012). These siblings might have witnessed the daily struggles of their parents and did not want to compound the situation. They appeared to have taken responsibility for their well-being, enabling the participants to support their brother or sister with CP. Previous studies have reported that typically developing siblings may be unhappy with the presence of children with CP (Huang et al. 2012, Navarausckas et al. 2010); however, in this study, the participants said that their typically developing children seemed to understand their condition and were willing to perform responsibilities for them. Siblings might be in a better position to educate society about children with CP and to encourage society to accept them and their parents as equal members.

Despite the acceptance of children with CP by typically developing siblings, a participant admitted that she did not assign caregiving duties to them. She recounted that she feared that the siblings might manhandle their brother or sister with CP and was reluctant to allow the siblings to be involved in the daily lives of the child with CP. This suggests that siblings may grow up with little knowledge about ways to cater for children with CP. This finding is consistent with those of studies, which reported that parents rarely involved siblings in the caregiving of children with disabilities (Harland and Cuskelly 2000, Kuo 2014). This can affect the relationship between siblings in later life, as typically developing children might not be wholly involved in the lives of their children with disabilities. If typically developing children are deeply involved in raising a sibling with CP, they might be more aware of their strengths and weaknesses and might continue to assist them in adulthood. In a previous study, Dew et al. (2014) found that the involvement of typically developing siblings in the early lives of children with CP enabled them to provide continuous support to the latter. The participants may wish to reconsider their decision and assign caregiving roles to typically developing siblings. This would enable them to develop deeper relationships, with the possibility of growing up to support each other.

Limitations

The results of this study should be interpreted with extreme caution due to several limitations. It is impossible to generalize the study findings because of the narrow non-probability sampling approach adopted for the recruitment of the participants and the small sample size used. The participants were recruited from the main referral hospital in Ghana and we did not know whether there were differences in family experiences in terms of whether the participants sought healthcare for their children. Also, this study relied on the voices of parents and we could not verify whether the perceptions of children with CP and typically developing siblings differed from those voices. We recommend that future studies explore the perceptions of family relationships from the perspectives of children with CP and their typically developing siblings. There is also a need for future studies to explore the health and well-being of parents of children with CP as well as the impact of children with CP on their sibling’s health and well-being.

Conclusion and policy implications

Despite the negative effects of caregiving on family income and the inability of participants to perform their duties towards their typically developing siblings, there seemed to be cordial relationships between children with CP and their siblings. This confirms the result of a review study by Dew et al. (2008), who found that parents were more likely to be negative about their relationship with their children with disabilities, while siblings were more likely to be positive. Although there were tensions between participants, in-laws, and spouses with regard to the presence of children with CP, the typically developing siblings seemed to accept their brothers and sisters as equal members of the family. However, some participants discussed that they rarely assigned roles to typically developing siblings in the day-to-day care of their children with CP. According to Dew et al. (2014), the involvement of children in the lives of siblings with disabilities will enable them to provide support across the lifespan of the latter. First, the results of this study appear to substantiate the need for policy-makers to design programs that involve the siblings of children with CP in daily life activities. This could enhance understanding between siblings as well as facilitate the inclusion of children with CP in society.

Second, there is a need for government to engage communities, social workers, families, and siblings about the capabilities of children with CP. To address the problems of social stigma, family breakdown, financial burden, and isolation, which were recounted by the participants, there is a need for the government of Ghana, through its Ministry of Gender, Children, and Social Protection, to establish formal support services for parents. Professional support workers can work in partnership with parents and siblings to identify their needs and priorities for the development of an effective intervention plan that equips them with effective parenting skills (Rentinck et al. 2006, Whittingham et al. 2011). This would help promote the acceptance of children with CP and encourage families to support their rehabilitation. Third, due to the negative impact of raising children with CP on family income, it is important for the government and charity organizations to assist parents either with cash to cover medical bills or through social services for recreational purposes. Government or charity organizations can also establish family centers that provide comprehensive evidence-based parenting interventions to empower parents with effective parenting practices (Whittingham et al. 2011, Zuurmond et al. 2018, 2019). These suggestions could lessen the burden on parents and enable them to provide for typically developing siblings in a holistic and inclusive manner.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Aboderin, I. 2004. Decline in material family support for older people in urban Ghana, Africa: Understanding processes and causes of change. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 59, 128–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agyemang, F. O., Asamoah, P. K. B., and Obodai, J.. 2018. Changing family systems in Ghana and its effects on access to urban rental housing: A study of the Offinso municipality. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Anthony, J. 2011. Conceptualising disability in Ghana: Implications for EFA and inclusive education. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 15, 1073–1086. [Google Scholar]

- Avoke, M. 2002. Models of disability in the labeling and attitudinal discourse in Ghana. Disability and Society, 17, 769–777. [Google Scholar]

- Babbie, E. 2011. The basics of social research. 5th ed. Belmont: Wadsworth. [Google Scholar]

- Baffoe, M. 2013. Stigma, discrimination and marginalization: Gateways to oppression of persons with disabilities in Ghana, West Africa. Journal of Educational and Social Research, 3, 187–198. [Google Scholar]

- Blacher, J. and Baker, B. L.. 2007. Positive impact of intellectual disability on families. American Journal on Mental Retardation, 112, 330–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brehaut, J. C., Kohen, D. E., Raina, P., Walter, S. D., Russell, D. J., Swinton, M., O'Donnell, M. and Rosenbaum, P.. 2004. The health of primary caregivers of children with cerebral palsy: How does it compare with that of other Canadian caregivers? Pediatrics, 114, e182–e191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulekbayeva, S., Daribayev, Z., Ospanova, S. and Vento, S.. 2017. Cerebral palsy: A multidisciplinary, integrated approach is essential. The Lancet Global Health, 5, e401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Button, S., Pianta, R. C. and Marvin, R. S.. 2001. Partner support and maternal stress in families raising young children with cerebral palsy. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 13, 61–81. [Google Scholar]

- Cheshire, A., Barlow, J. H. and Powell, L. A.. 2010. The psychosocial well-being of parents of children with cerebral palsy: A comparison study. Disability and Rehabilitation, 32, 1673–1677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark, G. 1999. Negotiating Asante family survival in Kumasi, Ghana. Africa, 69, 66–86. [Google Scholar]

- Craft, M. J., Lakin, J. A., Oppliger, R. A., Clancy, G. M. and Vanderlinden, D. W.. 1990. Siblings as change agents for promoting the functional status of children with cerebral palsy. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 32, 1049–1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W. and Guetterman, T.C.. 2015. Educational research: Planning, conducting and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research. 6th ed. New York, NY: Pearson Education. [Google Scholar]

- Dallas, E., Stevenson, J. and McGurk, H.. 1993. Cerebral‐palsied children’s interactions with siblings—II. Interactional structure. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 34, 649–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dan, B. and Paneth, N.. 2017. Making sense of cerebral palsy prevalence in low-income countries. The Lancet Global Health, 5, e1174–e1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis, E., Shelly, A., Waters, E., Boyd, R., Cook, K. and Davern, M., 2010. The impact of caring for a child with cerebral palsy: quality of life for mothers and fathers. Child: Care, Health and Development 36, 63–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dew, A., Balandin, S. and Llewellyn, G.. 2008. The psychosocial impact on siblings of people with lifelong physical disability: A review of the literature. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 20, 485–507. [Google Scholar]

- Dew, A., Llewellyn, G. and Balandin, S.. 2014. Exploring the later life relationship between adults with cerebral palsy and their non-disabled siblings. Disability and Rehabilitation, 36, 756–764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eker, L. and Tüzün, E. H.. 2004. An evaluation of quality of life of mothers of children with cerebral palsy. Disability and Rehabilitation, 26, 1354–1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garip, Y., Ozel, S., Tuncer, O. B., Kilinc, G., Seckin, F. and Arasil, T.. 2017. Fatigue in the mothers of children with cerebral palsy. Disability and Rehabilitation, 39, 757–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasscock, R. 2000. A phenomenological study of the experience of being a mother of a child with cerebral palsy. Pediatric Nursing, 26, 407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green, S. E. 2007. “We’re tired, not sad”: Benefits and burdens of mothering a child with a disability. Social Science and Medicine, 64, 150–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman, M. R. and Gruenewald, T. L.. 2017. Caregiving and perceived generativity: A positive and protective aspect of providing care? Clinical gerontologist, 40, 435–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harland, P. and Cuskelly, M.. 2000. The responsibilities of adult siblings of adults with dual sensory impairments. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 47, 293–307. [Google Scholar]

- Hiebert-Murphy, D., Trute, B. and Wright, A.. 2011. Parents' definition of effective child disability support services: implications for implementing family-centered practice. Journal of Family Social Work, 14, 144–158. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffnung, M., Hoffnung, R., Seifert K., Burton Smith, R., Hine A., Ward, L., Pause C. and Swabey, K.. 2010. Lifespan development: A topical approach. Milton Qld: John Wiley and Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffnung, M., Hoffnung, R., Seifert K., Hine A., Burton Smith, R., Hine, A., Ward, L. and Pause C.. 2013. Lifespan development: A chronological approach. 2nd ed. Milton Qld: John Wiley and Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffnung, M., Hoffnung, R., Seifert K., Hine A., Ward, L., Pause C., Swabey, K., Yates, K. and Burton Smith, R.. 2016. Lifespan development. 3rd ed. Milton Qld: John Wiley and Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y. P., Kellett, U. M. and St John, W.. 2010. Cerebral palsy: Experiences of mothers after learning their child’s diagnosis. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 66, 1213–1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y. P., Kellett, U. and St John, W.. 2012. Being concerned: Caregiving for Taiwanese mothers of a child with cerebral palsy. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 21, 189–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassah, A. K., Kassah, B. L. L. and Agbota, T. K.. 2012. Abuse of disabled children in Ghana. Disability and Society, 27, 689–701. [Google Scholar]

- Kassah, B. L. L., Kassah, A. K. and Agbota, T. K.. 2014. Abuse of physically disabled women in Ghana: Its emotional consequences and coping strategies. Disability and Rehabilitation, 36, 665–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khayatzadeh, M. M., Rostami, H. R., Amirsalari, S. and Karimloo, M.. 2013. Investigation of quality of life in mothers of children with cerebral palsy in Iran: Association with socio-economic status, marital satisfaction and fatigue. Disability and Rehabilitation, 35, 803–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura, M., and Yamazaki, Y.. 2016. Mental health and positive change among Japanese mothers of children with intellectual disabilities: Roles of sense of coherence and social capital. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 59, 43–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koman, A., Smith, B. and Shilt, J.. 2004. Cerebral palsy. The Lancet, 63, 1619–1931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kpoor, A. 2015. The nuclearization of Ghanaian families. Current Politics and Economics of Africa, 8, 435. [Google Scholar]

- Kutsoati, E. and Morck, R.. 2014. Family ties, inheritance rights, and successful poverty alleviation: Evidence from Ghana. Cambridge, MA: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kuo, Y. C. and Geraci, L. M.. 2012. Sister’s caregiving experience to a sibling with cerebral palsy – The impact to daughter-mother relationships. Sex Roles, 66, 544–557. [Google Scholar]

- Kuo, Y. C. 2014. Brothers’ experiences caring for a sibling with Down syndrome. Qualitative Health Research, 24, 1102–1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludlow, A., Skelly, C., and Rohleder, P.. 2012. Challenges faced by parents of children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Health Psychology, 17, 702–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louis, P. T. and Kumar, N.. 2016. Perceived parental differential treatment, cognition, behaviour and family cohesiveness among siblings of children with cerebral palsy? A family-mediated intervention to understand ‘displaced’ children. International Journal on Disability and Human Development, 15, 243–250. [Google Scholar]

- McAdams, R. M., and Juul, S. E.. 2011. Cerebral palsy: Prevalence, predictability, and parental counselling. NeoReviews, 12, 564–679. [Google Scholar]

- Mophosho, M., Widdows, J. and Gomez, M. T.. 2009. Relationships between adolescent children and their siblings with cerebral palsy: A pilot study. Journal on Developmental Disabilities, 15, 81–87. [Google Scholar]

- Myers, B. J., Mackintosh, V. H., and Goin-Kochel, R. P.. 2009. “My greatest joy and my greatest heart ache:” Parents’ own words on how having a child in the autism spectrum has affected their lives and their families’ lives. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 3, 670–684. [Google Scholar]

- Naami, A., Hayashi, R. and Liese, H.. 2012. The unemployment of women with physical disabilities in Ghana: Issues and recommendations. Disability and Society, 27, 191–204. [Google Scholar]

- Naami, A. 2014. Breaking the barriers: Ghanaians’ perspectives about the social model. Disability, CBR and Inclusive Development, 25, 21–39. [Google Scholar]

- Navarausckas, H. D. B., Sampaio, I. B., Urbini, M. P., and Costa, R. C. V.. 2010. " Hey, I´ m here too"!: The psychological aspects from the point of view of the siblings of a child with cerebral palsy in the family nucleus. Estudos de Psicologia (Campinas), 27, 505–513. [Google Scholar]

- Ofori-Dua, K. 2014. Extended family support and elderly care in Bamang, Ashanti region of Ghana. PhD. Department of Social Work University of Ghana.

- Omiya, T. and Yamazaki, Y.. 2017. Positive change and sense of coherence in Japanese mothers of children with congenital appearance malformation. Health Psychology Open, 4, 2055102917729540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opoku, M. P., Badu, E., Amponteng, M. and Agyei-Okyere, E.. 2015. Inclusive education at the crossroads in Ashanti and Brong Ahafo regions in Ghana: Target not achievable by 2015. Disability, CBR and Inclusive Development, 26, 63–78. [Google Scholar]

- Opoku, M. P., Alupo, B. A., Gyamfi, N., Odame, L., Mprah, W. K., Torgbenu, E. L. and Badu, E.. 2017a. The family and disability in Ghana: Highlighting gaps in achieving social inclusion. Disability, CBR and Inclusive Development, 28, 41–59. [Google Scholar]

- Opoku, M. P., Gyamfi, N., Badu, E. and Mprah, W. K.. 2017b. ‘They think we are all beggars’: The resilience of a person with disability in Ghana. Journal of Exceptional People, 2, 6–17. [Google Scholar]

- Opoku, M. P., Swabey J-F, K., Pullen, D. and Dowden, T.. 2018. Assisting individuals with disabilities via the United Nations’ sustainable development goals: A case study in Ghana. Sustaining Development, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Oppong, C. 1977. A note from Ghana on chains of change in family systems and family size. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 615–621. [Google Scholar]

- Pimm, P. L. 1996. Some of the implications of caring for a child or adult with cerebral palsy. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 59, 335–341. [Google Scholar]

- Polack, S., Adams, M., O'banion, D., Baltussen, M., Asante, S., Kerac, M. and Zuurmond, M. (2018). Children with cerebral palsy in Ghana: Malnutrition, feeding challenges, and caregiver quality of life. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 60, 914–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajan, A. M. and John, R.. 2017. Resilience and impact of children’s intellectual disability on Indian parents. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities, 21, 315–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rentinck, I. C. M., Ketelaar, M., Jongmans, M. J. and Gorter, J. W.. 2006. Parents of children with cerebral palsy: A review of factors related to the process of adaptation. Child: Care, Health and Development, 33, 161–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross, P. and Cuskelly, M.. 2006. Adjustment, sibling problems and coping strategies of brothers and sisters of children with autistic spectrum disorder. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 31, 77–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senayah, A. E., Mprah, W. K., Opoku, M. P., Edusei, A. K. and Torgbenu, E. L.. 2018. The accessibility of health services to young deaf adolescents in Ghana. International Journal of Health Planning Management, 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng, M. H., Chen, K. L., Shieh, J. Y., Lu, L., Huang, C. Y. and Simeonsson, R. J.. 2016. Child characteristics, caregiver characteristics, and environmental factors affecting the quality of life of caregivers of children with cerebral palsy. Disability and Rehabilitation, 38, 2374–2382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. 2006. Convention on the rights of persons with disabilities and optional protocol. New York: Author. [Google Scholar]

- White F., Hayes, B. and Livesey, D.. 2016. Developmental psychology: From infancy to adulthood. 4th ed. Melbourne: Pearson Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Whittingham, K., Wee, D., Sanders, M., and Boyd, R.. 2011. Responding to the challenges of parenting a child with cerebral palsy: A focus group. Disability and Rehabilitation, 33, 1557–1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuurmond, M., O’Banion, D., Gladstone, M., Carsamar, S., Kerac, M., Baltussen, M. and Polack, S.. 2018. Evaluating the impact of a community-based parent training programme for children with cerebral palsy in Ghana. PloS one, 13, 1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuurmond, M., Nyante, G., Baltussen, M., Seeley, J., Abanga, J., Shakespeare, T., Collumbien, M. and Bernays, S. (2019). A support programme for caregivers of children with disabilities in Ghana: Understanding the impact on the wellbeing of caregivers. Child: Care, Health and Development, 45, 45–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]