Abstract

Eating disorders are multifaceted problems with various risk factors, including the sociocultural context, social media, society's beauty standards, personality, and genetics. The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has been a cause of stress among university students, as well as inducing changes in their physical activity and eating habits.

Objective

The objectives of this study were to evaluate the changes in body mass index and risk of developing eating disorders among university students during the COVID 19 pandemic.

Methods

This was a cross-sectional study of 1004 female students recruited from a university in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Data were collected from December 2020 to March 2021 through a self-administered questionnaire comprising three parts: sociodemographic items, the Eating Attitudes Test, and an evaluation of behavioral changes during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Results

Most participants were aged 18–24 years, single, lived with their parents, and had a moderate to high family income. There was a significant relationship between the risk of developing eating disorders and marital status (p < 0.001). College type (p < 0.003), fast food consumption (p = 0.010), and engaging in exercise (p < 0.001) were also significant factors. Based on categorizations of risk levels derived from the literature, about 31.5% of the participants had a high risk of developing eating disorders.

Conclusion

According to our results, eating disorders are relatively common among Saudi female undergraduate students. Thus, educational programs that aim to increase this population's awareness concerning appropriate nutrition and body weight are needed.

Keywords: BMI, COVID-19, Eating disorders, KSA, Pandemic

الملخص

أهداف البحث

تتأثر اضطرابات الأكل بالعديد من العوا مل، بما في ذلك العوامل الاجتماعية والثقافية، ووسائل التواصل الاجتماعي، ومعايير الجمال في المجتمع، والشخصية، والعوامل الوراثية. كانت جائحة (كوفيد-١٩) سببا للتوتر بين طلاب الجامعات وتسبب ذلك بإحداث تغيرات في نشاطهم البدني وعاداتهم الغذائية. كانت أهدافهذهالدراسةهيتقييمالتغيراتفيمؤشركتلةالجسموخطرالإصابةباضطراباتا لأكلبينطالباتالجامعةخلالجائحة (كوفيد-١٩).

طرق البحث

كانت هذه دراسة مقطعية شملت 1004 طالبة جامعية سعودية. تم جمع البيانات من ديسمبر 2020 إلى مارس 2021 من خلال استبانة تم نشرها على منصات التواصل الاجتماعي. تتألف الاستبانة من ثلاثة أجزاء: العناصر الاجتماعية والديموغرافية، واختبار مواقف الأكل، وتقييم التغيرات في السلوكيات خلال جائحة (كوفيد-١٩).

النتائج

تراوحت أعمار معظم المشاركات بين 18 و24 عاما، وكانوا غير متزوجات ويعشن مع والديهن. كان لدى معظم المشاركات دخل متوسط إلى مرتفع (67.5٪). تم العثور على علاقة ذات دلالة إحصائية بين خطر اضطرابات الأكل والحالة الاجتماعية. كما كان نوع الكلية، واستهلاك الوجبات السريعة، والانخراط في التمارين الرياضية من العوامل المهمة أيضا. استنادا إلى تصنيفات مستويات الخطر المستمدة من البحث، كان حوالي 31.5 ٪ من المشاركين معرضين لخطر الإصابة باضطرابات الأكل.

الاستنتاجات

وفقا لنتائجنا، فإن اضطرابات الأكل شائعة نسبيا بين الطالبات السعوديات الجامعيات. وبالتالي، هناك حاجة إلى برامج تعليمية تهدف إلى زيادة وعي السكان فيما يتعلق بالتغذية المناسبة ووزن الجسم.

الكلمات المفتاحية: اضطرابات التغذية والأكل, مؤشر كتلة الجسم, كوفيد -19, الجائحة, المملكة العربية السعودية

Introduction

Eating disorders are serious health conditions identified by abnormal eating habits and related thoughts and emotions.1 Harmful dieting behaviors can result in major complications, such as anxiety disorder, depression, cardiovascular symptoms, infections, and suicide attempts, in early adulthood. In bulimia, for example, the upper gastrointestinal system can be damaged by vomiting, and stomach acid can erode the enamel of the teeth; it can also alter the menstrual cycle.2,3

Eating disorders and behaviors are affected by both external factors, such as the sociocultural context (e.g., comparison with peers, family, and friends), social media, and society's beauty standards, as well as internal factors, such as personality traits, low self-esteem, genetics, and biology.4,5 The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic and the consequent government-mandated quarantine measures have emerged as a crucial risk factor for mental health problems. Among some people, anxiety provoked by the pandemic has led to the adoption of many unhealthy coping mechanisms, including stress eating.6, 7, 8, 9 By contrast, there are those who have become more conscious about their health, focusing on exercise and a healthy diet.10,11

The early detection of eating disorders can help prevent disease progression and reduce the likelihood of serious complications.12 This is especially important during the COVID-19 pandemic, which, as previously mentioned, has generated widespread stress and led to dramatic changes in eating habits and physical activity routines.13

Previous studies have demonstrated a high prevalence of eating disorders among Saudi female university students.14 However, to our knowledge, no studies have evaluated this tendency during the COVID-19 outbreak. Therefore, in this study, we aimed to fill the research gap by measuring the prevalence of eating disorders among female university students during the COVID-19 outbreak.

Materials and Methods

Design

This study employed a cross-sectional design. The estimated sample size needed was 1000, based on a power of 0.95, and the expected prevalence of eating disorders among female university students during the COVID-19 outbreak is 35.4%, with ±5% as margin of error.15 Data collection continued until we reached the estimated sample size plus 40% to compensate for any incomplete surveys. This study was approved by the concerned institutional review board (20-0507), and all participants provided written informed consent.

Data collection

The sample comprised 1004 Saudi female undergraduate students from the various colleges affiliated to a single university in Riyadh. The exclusion criteria were 1) students with health conditions and 2) students who took any medications that could affect their weight. The data for the final survey were collected from December 2020 to March 2021 through a three-part questionnaire. The Google Form link to the self-administered questionnaire was distributed using WhatsApp and Telegram; the questionnaire could only be accessed using student IDs.

The first part of the questionnaire included sociodemographic items, such as age, nationality, marital status, height, and weight. The second part consisted of the Eating Attitudes Test, a standardized 26-item self-report questionnaire developed by Garner and Garfinkel in 197916 and translated to Arabic and validated by Al-Adawi et al., in 2002.17 Each question is answered on a six-point Likert scale. For questions 1–25, the answers “always,” “usually,” and “often” are scored 3, 2, and 1, respectively, while “never,” “rarely,” and “sometimes” are scored 0. For question 26, that is, “Enjoy trying new rich foods,” the answers “always,” “usually,” and “often” are scored 0 and “never,” “rarely,” and “sometimes” are scored 3, 2, and 1, respectively. The total scores range from 0 to 78. Scores under 20 indicate a minimal risk of developing an eating disorder, while scores of 20 or above indicate a high risk of developing an eating disorder.

Third part of the questionnaire designed to assess changes in food consumption and physical activity during COVID-19 pandemic, a self-made questionnaire composed of 13 questions was developed in English by a bilingual panel comprising of three healthcare professionals, the English version was translated to the Arabic language. A back translation to English was subsequently performed by two English-speaking translators. A pilot survey was made and distributed to 40 participants.

Anthropometrics

Based on body mass index (BMI), calculated as kg/m2 (18), participants were divided into five categories—underweight (BMI of <18.5 kg/m2), normal weight (BMI of 18.5–24.9 kg/m2), and overweight (BMI of 25–29.9 kg/m2)—and three classes of obesity, namely, class 1 (BMI of 30–34.9 kg/m2), class 2 (BMI of 35–39.9 kg/m2), and class 3 (BMI ≥40 kg/m2).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 20.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive statistics—frequency, count, and percentage—were used to determine the associations between categorical variables and the risk of developing eating disorders and BMI. The chi-square test was used followed by adjusted standardized residuals with Bonferroni correction post-hoc test. The level of significance was set at p < 0.050 (two tailed).

Results

Table 1 shows the participants' demographic characteristics. The majority of the participants were aged 18–20 years (n = 513, 51.1%), single (n = 933, 92.9%), middle children (n = 508, 51.0%), and living with their parents (n = 885, 88.0%). Most had a monthly family income of more than SAR15,000 (n = 458, 45.6%), followed by SAR10,001–SAR15,000 (n = 220, 21.9%). As for parents’ educational level, most had a university education [fathers: (n = 388, 38.6%), mothers: (n = 405, 40.3%), followed by a secondary education [fathers: (n = 185, 18.4%), mothers: (n = 220, 21.9%)].

Table 1.

Participants’ sociodemographic profile (N = 1004).

| Demographical charactaristics | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| Less than 18 | 62 | 6.20% |

| 18–20 | 513 | 51.10% |

| 20–22 | 217 | 27.00% |

| 22–24 | 105 | 10.50% |

| More than 24 | 53 | 5.30% |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 933 | 92.90% |

| Married | 64 | 6.40% |

| Divorced | 7 | 0.70% |

| Widowed | 0 | 0.00% |

| Order in family | ||

| Oldest | 290 | 0.29% |

| Middle | 508 | 0.51% |

| Youngest | 197 | 0.20 |

| Only child | 9 | 0.01 |

| Living with | ||

| Parents | 885 | 0.88% |

| Husband | 51 | 0.05% |

| Alone | 23 | 0.025 |

| Other | 45 | 0.05% |

| Family monthly income | ||

| Less than 5000 | 114 | 11.40% |

| 5000–10,000 | 212 | 21.10% |

| 10,001–15,0000 | 220 | 21.90% |

| More than 15,000 | 458 | 45.60% |

| Father education | ||

| Illiterate | 23 | 2.30% |

| Elementary | 63 | 6.30% |

| Intermediate | 92 | 9.20% |

| Secondary | 185 | 18.40% |

| Institute | 94 | 9.40% |

| University | 388 | 38.60% |

| Postgrad | 159 | 15.80% |

| Mother education | ||

| Illiterate | 46 | 4.60% |

| Elementary | 107 | 10.70% |

| Intermediate | 111 | 11.10% |

| Secondary | 220 | 21.90% |

| Institute | 68 | 6.80% |

| University | 405 | 40.30% |

| Postgrad | 47 | 4.70% |

| Distribution of colleges | ||

| Health collages | 343 | 34.20% |

| Science collages | 327 | 32.60% |

| Litreature collages | 231 | 23.00% |

| Admistrative collages | 103 | 10.30% |

| BMI | ||

| Underweight | 217 | 21.60% |

| Normal weight | 526 | 52.40% |

| Overweight | 180 | 17.90% |

| Obesity class I | 47 | 4.70% |

| Obesity class II | 17 | 1.70% |

| Obesity class III | 5 | 0.50% |

Table 2 displays the factors associated with the distribution of weight status. The distribution of weight status was found to be significantly associated with marital status and living arrangements (p < 0.001). Regarding marital status, of those with a normal weight, most were either single (n = 496, 53.7%) or married (n = 29, 46.8%), while among those who were overweight, most were divorced (n = 4, 57.1%). Regarding living arrangements, of those with a normal weight, most lived either with their parents (n = 478, 54.6%) and husbands (n = 18, 36.7%) or alone (n = 15, 65.2%). Of those who were underweight, most lived with others (n = 17, 38.6%). Further, a notable proportion of those living with their husbands was overweight (n = 14, 28.6%). High proportions of overweight participants were from the colleges of science (n = 81, 24.8%) and literature (n = 47, 21.1%).

Table 2.

Distribution of weight status across several factors.

| Factors | Weight status |

P-value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Underweight | Normal weight | Overweight | Obesity Class I | Obesity Class II | Obesity Class III | ||

| Marital status | |||||||

| Single | 210 (21.2%) | 496 (50%) | 161 (16.2%) | 37 (3.7%) | 15 (1.5%) | 4 (0.4%) | <0.001∗ |

| Married | 5 (0.5%) | 29 (2.9%) | 15 (1.5%) | 10 (1.0%) | 2 (0.2%) | 1 (0.1%) | |

| Divorced | 2 (0.2%) | 1 (0.1%) | 4 (0.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Total | 217 (21.9%) | 526 (53.0%) | 180 (18.1%) | 47 (4.7%) | 17 (1.7%) | 5 (0.5%) | |

| Living with | |||||||

| Parents | 189 (19.1%) | 478 (48.2%) | 157 (15.8%) | 35 (3.5%) | 13 (1.3%) | 4 (0.4%) | <0.001∗ |

| Husband | 4 (0.4%) | 18 (1.8%) | 14 (1.4%) | 10 (1%) | 2 (0.2%) | 1 (0.1%) | |

| Alone | 7 (0.7%) | 15 (1.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Other | 17 (1.7%) | 15 (1.5%) | 9 (0.9%) | 1 (0.1%) | 2 (0.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Total | 217 (21.9%) | 526 (53%) | 180 (18.1%) | 47 (4.7%) | 17 (1.7%) | 5 (0.5%) | |

| Family monthly income | |||||||

| Less than 5000 | 23 (2.3%) | 54 (5.4%) | 29 (2.9%) | 6 (0.6%) | 2 (0.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.457 |

| 5000–10,000 | 45 (4.5%) | 109 (11.0%) | 42 (4.2%) | 12 (1.2%) | 2 (0.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| 10,001–15,0000 | 49 (4.9%) | 119 (12.0%) | 30 (3.0%) | 11 (1.1%) | 7 (0.7%) | 2 (0.2%) | |

| More than 15,000 | 100 (10.1%) | 244 (24.6%) | 79 (8.0%) | 18 (1.8%) | 6 (0.6%) | 3 (0.3%) | |

| Total | 217 (21.9%) | 526 (53.0%) | 180 (18.1%) | 47 (4.7%) | 17 (1.7%) | 5 (0.5%) | |

| Fast food consumption | |||||||

| Decreased | 50 (17.2%) | 152 (52.2%) | 68 (23.4%) | 15 (5.2%) | 4 (1.4%) | 2 (0.7%) | 0.010∗ |

| Slightly decreased | 35 (17.9%) | 117 (60.0%) | 32 (16.4%) | 6 (3.1%) | 3 (1.5%) | 2 (1.0%) | |

| No change | 51 (28.0%) | 100 (54.9%) | 18 (9.9%) | 8 (4.4%) | 4 (2.2%) | 1 (0.5%) | |

| Slightly increased | 55 (28.8%) | 92 (48.2%) | 29 (15.2%) | 10 (5.2%) | 5 (2.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Increased | 26 (19.5%) | 65 (48.9%) | 33 (24.8%) | 8 (6.0%) | 1 (0.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Total | 217 (21.9%) | 526 (53.0%) | 180 (18.1%) | 47 (4.7%) | 17 (1.7%) | 5 (0.5%) | |

| Exercise | |||||||

| Walking | 59 (16.3%) | 192 (53.2%) | 78 (21.6%) | 21 (5.8%) | 7 (1.9%) | 4 (1.1%) | <0.001∗ |

| Swimming | 3 (14.3%) | 14 (66.7%) | 1 (4.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (14.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Home workout | 63 (17.5%) | 202 (56.1%) | 74 (20.6%) | 17 (4.7%) | 4 (1.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Gym | 16 (27.6%) | 28 (48.3%) | 11 (19.0%) | 3 (5.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Other | 76 (40.2%) | 88 (46.6%) | 15 (7.9%) | 6 (3.2%) | 3 (1.6%) | 1 (0.5%) | |

| Total | 217 (21.9%) | 524 (53.0%) | 179 (18.1%) | 47 (4.8%) | 17 (1.7%) | 5 (0.5%) | |

| Collage | |||||||

| Health collages | 84 (38.7%) | 197 (37.5%) | 38 (21.1%) | 12 (25.5%) | 9 (52.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.003∗ |

| Science collages | 69 (31.8%) | 153 (29.1%) | 81 (45.0%) | 16 (34%) | 5 (29.4%) | 2 (40.0%) | |

| Literature collages | 39 (18.0%) | 121 (23%) | 47 (26.1%) | 12 (25.5%) | 2 (11.8%) | 2 (40.0%) | |

| Administrative collages | 25 (11.5%) | 55 (10.5%) | 14 (7.8%) | 7 (14.9%) | 1 (5.9%) | 1 (20.0%) | |

| Total | 217 (100.0%) | 526 (100.0%) | 180 (100.0%) | 47 (100.0%) | 17 (100.0%) | 5 (100.0%) | |

| Age | |||||||

| Less than 18 | 16 (7.4%) | 33 (6.3%) | 8 (4.4%) | 2 (4.3%) | 2 (11.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.005∗ |

| 18–20 | 129 (59.4%) | 273 (51.9%) | 74 (41.1%) | 18 (4.3%) | 11 (64.7%) | 1 (20.0%) | |

| 20–22 | 44 (20.3%) | 143 (27.2%) | 64 (35.6%) | 15 (31.9%) | 2 (11.8%) | 2 (40.0%) | |

| 22–24 | 23 (10.6%) | 52 (9.9%) | 20 (11.1%) | 6 (12.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (20.0%) | |

| More than 24 | 5 (2.3%) | 25 (4.8%) | 14 (7.8%) | 6 (12.8%) | 2 (11.8%) | 1 (20.0%) | |

| Total | 217 (100.0%) | 526 (100.0%) | 180 (100.0%) | 47 (100.0%) | 17 (100.0%) | 5 (100.0%) | |

| Order in family | |||||||

| Oldest | 64 (29.5%) | 144 (27.4%) | 58 (32.2%) | 12 (25.5%) | 9 (52.9%) | 3 (60.0%) | 0.164 |

| Middle | 112 (51.6%) | 277 (52.7%) | 76 (42.2%) | 26 (55.3%) | 5 (29.4%) | 2 (40.0%) | |

| Youngest | 41 (18.9%) | 97 (18.4%) | 45 (25.0%) | 9 (19.1%) | 3 (17.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Only child | 0 (0.0%) | 8 (1.5%) | 1 (0.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Total | 217 (100.0%) | 526 (100.0%) | 180 (100.0%) | 47 (100.0%) | 17 (100.0%) | 5 (100.0%) | |

| Father education | |||||||

| Illiterate | 1 (0.5%) | 11 (2.1%) | 5 (2.8%) | 3 (6.4%) | 1 (5.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | <0.005∗ |

| Elementary | 15 (6.9%) | 26 (4.9%) | 17 (9.4%) | 4 (8.5%) | 1 (5.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Intermediate | 34 (15.7%) | 36 (6.8%) | 19 (10.6%) | 2 (4.3%) | 1 (5.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Secondary | 48 (22.1%) | 89 (16.9%) | 35 (19.4%) | 11 (23.4%) | 2 (11.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Institute | 20 (9.2%) | 44 (8.4%) | 23 (12.8%) | 4 (8.5%) | 1 (5.9%) | 1 (0.0%) | |

| University | 69 (31.8%) | 231 (43.9%) | 53 (29.4%) | 14 (29.8%) | 9 (52.9%) | 4 (80.0%) | |

| Postgrad | 30 (13.8%) | 89 (16.9%) | 28 (15.6%) | 9 (19.1%) | 2 (11.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Total | 217 (100.0%) | 526 (100.0%) | 180 (100.0%) | 47 (100.0%) | 17 (100.0%) | 5 (100.0%) | |

| Mother education | |||||||

| Illiterate | 3 (1.4%) | 21 (4.0%) | 17 (9.4%) | 4 (8.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (20.0%) | <0.000∗ |

| Elementary | 25 (11.5%) | 46 (8.7%) | 26 (14.4%) | 8 (17.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Intermediate | 24 (11.1%) | 55 (10.5%) | 17 (9.4%) | 7 (14.9%) | 7 (41.2%) | 1 (20.0%) | |

| Secondary | 52 (24.0%) | 128 (24.3%) | 28 (15.6%) | 7 (14.9%) | 1 (5.9%) | 1 (20.0%) | |

| Institute | 9 (4.1%) | 40 (7.6%) | 12 (6.7%) | 3 (6.4%) | 4 (23.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| University | 94 (43.3%) | 215 (40.9%) | 69 (38.3%) | 14 (29.8%) | 5 (29.4%) | 2 (40.0%) | |

| Postgrad | 10 (4.6%) | 21 (4.0%) | 11 (6.1%) | 4 (8.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Total | 217 (100.0%) | 526 (100.0%) | 180 (100.0%) | 47 (100.0%) | 17 (100.0%) | 5 (100.0%) | |

∗ Significant at level 0.05.

Table 3 demonstrates the distribution of risk of developing eating disorders across several factors. A significant association with the distribution of risk for developing eating disorders was noted across different colleges (p < 0.003). The participants with the highest risk of developing an eating disorder belonged to the college of literature (n = 94, 40.7%), while those with the lowest risk belonged to the college of health (n = 253, 73.8%).

Table 3.

Distribution of risk for developing eating disorders across factors.

| Factors | Risk for developing eating disorder |

P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low risk | High risk | Total | ||

| Marital status | ||||

| Single | 635 (63.2%) | 298 (29.7%) | 933 (100.0%) | 0.413 |

| Married | 47 (4.7%) | 17 (1.7%) | 64 (100.0%) | |

| Divorced | 6 (0.6%) | 1 (0.1%) | 7 (100.0%) | |

| Total | 688 (68.5%) | 316 (31.5%) | 1004 (100.0%) | |

| Living with | ||||

| Parents | 610 (60.8%) | 275 (27.4%) | 885 (100.0%) | 0.655 |

| Husband | 36 (3.6%) | 15 (1.5%) | 51 (100.0%) | |

| Alone | 14 (1.4%) | 9 (0.9%) | 23 (100.0%) | |

| Other | 28 (2.8%) | 17 (1.7%) | 45 (100.0%) | |

| Total | 688 (68.5%) | 316 (31.5%) | 1004 (100.0%) | |

| Family monthly income | ||||

| Less than 5000 | 78 (7.8%) | 36 (3.6%) | 114 (100.0%) | 0.772 |

| 5000–10,000 | 147 (14.6%) | 65 (6.5%) | 212 (100.0%) | |

| 10,001–15,0000 | 156 (15.5%) | 64 (6.4%) | 220 (100.0%) | |

| More than 15,000 | 307 (30.6%) | 151 (15%) | 458 (100.0%) | |

| Total | 688 (68.5%) | 316 (31.5%) | 1004 (100.0%) | |

| Fast food consumption | ||||

| Decreased | 199 (67.2%) | 97 (32.8%) | 296 (100.0%) | 0.039∗ |

| Slightly decreased | 145 (73.2%) | 53 (26.8%) | 198 (100.0%) | |

| No change | 129 (70.5%) | 54 (29.5%) | 183 (100.0%) | |

| Slightly increased | 136 (71.2%) | 55 (28.8%) | 191 (100.0%) | |

| Increased | 79 (58.1%) | 57 (41.9%) | 136 (100.0%) | |

| Total | 688 (68.5%) | 316 (31.5%) | 1004 (100.0%) | |

| Exercise | ||||

| Walking | 258 (70.5%) | 108 (29.5%) | 366 (100.0%) | <0.001∗ |

| Swimming | 10 (47.6%) | 11 (52.4%) | 21 (100.0%) | |

| Home workout | 235 (65.1%) | 126 (34.9%) | 361 (100.0%) | |

| Gym | 33 (54.1%) | 28 (45.9%) | 61 (100.0%) | |

| Other | 151 (78.6%) | 41 (21.4%) | 192 (100.0%) | |

| Total | 687 (68.6%) | 314 (31.4%) | 1001 (100.0%) | |

| Collage | ||||

| Health collages | 253 (36.8%) | 90 (28.5%) | 103 (100.0%) | 0.003∗ |

| Science collages | 228 (33.1%) | 99 (31.3%) | 327 (100.0%) | |

| Literature collages | 137 (19.9%) | 94 (29.7%) | 231 (100.0%) | |

| Administrative collages | 70 (10.2%) | 33 (10.4%) | 343 (100.0%) | |

| Total | 688 (100.0%) | 316 (100.0%) | 1004 (100.0%) | |

| Age | ||||

| Less than 18 | 40 (5.8%) | 22 (7.0%) | 62 (6.2%) | 0.846 |

| 18–20 | 350 (50.9%) | 163 (51.6%) | 513 (51.1%) | |

| 20–22 | 187 (27.2%) | 84 (26.6%) | 271 (27.0%) | |

| 22–24 | 76 (11.0%) | 29 (9.2%) | 105 (10.5%) | |

| More than 24 | 35 (5.1%) | 18 (5.7%) | 53 (5.3%) | |

| Total | 688 (100.0%) | 316 (100.0%) | 1004 (100.0%) | |

| Order in family | ||||

| Oldest | 199 (28.9%) | 91 (28.8%) | 290 (28.9%) | 0.448 |

| Middle | 352 (51.2%) | 156 (49.4%) | 508 (50.6%) | |

| Youngest | 133 (19.3%) | 64 (20.3%) | 197 (19.6%) | |

| Only child | 4 (0.6%) | 5 (1.6%) | 9 (0.9%) | |

| Total | 688 (100.0%) | 316 (100.0%) | 1004 (100.0%) | |

| Father education | ||||

| Illiterate | 14 (2.0%) | 9 (2.8%) | 23 (2.3%) | 0.238 |

| Elementary | 51 (7.4%) | 12 (3.8%) | 63 (6.3%) | |

| Intermediate | 68 (9.9%) | 24 (7.6%) | 92 (9.2%) | |

| Secondary | 124 (18.0%) | 61 (19.3%) | 185 (18.4%) | |

| Institute | 64 (9.3%) | 30 (9.5%) | 94 (9.4%) | |

| University | 265 (38.5%) | 123 (38.9%) | 388 (38.6%) | |

| Postgrad | 102 (14.8%) | 57 (18.0%) | 159 (15.8%) | |

| Total | 688 (100.0%) | 316 (100.0%) | 1004 (100.0%) | |

| Mother education | ||||

| Illiterate | 32 (4.7%) | 14 (4.4%) | 46 (4.6%) | 0.010 |

| Elementary | 90 (13.1%) | 17 (5.4%) | 107 (10.6%) | |

| Intermediate | 76 (11.0%) | 35 (11.1%) | 111 (11.1%) | |

| Secondary | 142 (20.6%) | 78 (24.7%) | 220 (21.9%) | |

| Institute | 44 (6.4%) | 24 (7.6%) | 68 (6.8%) | |

| University | 277 (40%) | 128 (40.5%) | 405 (40.3%) | |

| Postgrad | 27 (3.9%) | 20 (6.3%) | 47 (4.7%) | |

| Total | 688 (100.0%) | 316 (100.0%) | 1004 (100.0%) | |

∗Significant at level 0.050.

Table 4 shows the association of the distribution of weight status and risk of developing eating disorders with fast food consumption and performing exercises during the COVID-19 pandemic. A significant difference in the distribution of weight status was noted by both fast food consumption (p = 0.010) and performance of exercise (p < 0.001). The highest proportions of participants who were overweight (33) (24.8%) and belonged to obesity class 1 (8) (6.0%) were among those with increased fast food consumption. A higher rate of overweight participants was observed among those who walked (n = 78, 21.6%), performed home workouts (74) (20.6%), and went to the gym (n = 11, 19.0%) compared with those who went swimming (1) (4.8%) and performed other types of exercise (n = 15, 7.9%). The distribution of risk of developing an eating disorder also significantly varied by fast food consumption (p < 0.050) and performance of exercise (p < 0.001). Those with increased fast food consumption (n = 57, 41.9%) were at the highest risk of developing an eating disorder, while those with slightly decreased consumption (n = 145, 73.2%) were at the lowest risk. The highest risk of developing an eating disorder was among those who went swimming (n = 11, 52.4%), while the lowest was among those who practiced exercises other than those mentioned (n = 151, 78.6%).

Table 4.

The distribution of weight status and risk for developing eating disorders in fast-food consumption and performance of exercise during COVID-19 pandemic.

| Factors | Collage |

P-Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health collages | Science collages | Literature collages | Administrative collages | Total | ||

| BMI | ||||||

| Underweight | 84 (38.7%) | 69 (31.8%) | 39 (18.0%) | 25 (11.5%) | 217 (100.0%) | 0.003∗ |

| Normal weight | 197 (37.5%) | 153 (29.1%) | 121 (23.0%) | 55 (10.5%) | 526 (100.0%) | |

| Overweight | 38 (21.1%) | 81 (45.0%) | 47 (26.1%) | 14 (7.8%) | 180 (100.0%) | |

| Obesity Class I | 12 (25.5%) | 16 (34.0%) | 12 (25.5%) | 7 (14.9%) | 47 (100.0%) | |

| Obesity Class II | 9 (52.9%) | 5 (29.4%) | 2 (11.8%) | 1 (5.9%) | 17 (100.0%) | |

| Obesity Class III | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (40.0%) | 2 (40.0%) | 1 (20.0%) | 5 (100.0%) | |

| Total | 340 (34.3%) | 326 (32.9%) | 223 (22.5%) | 103 (10.4%) | 992 (100.0%) | |

| Risk of developing eating disorder | ||||||

| High risk | 90 (28.5%) | 99 (31.3%) | 94 (29.7%) | 33 (10.4%) | 316 (100.0%) | 0.003∗ |

| Low risk | 253 (36.8%) | 228 (33.1%) | 137 (19.9%) | 70 (10.2%) | 688 (100.0%) | |

| Total | 343 (34.2%) | 327 (32.6%) | 231 (23.0%) | 103 (10.3%) | 1004 (100.0%) | |

∗Significant at level 0.050.

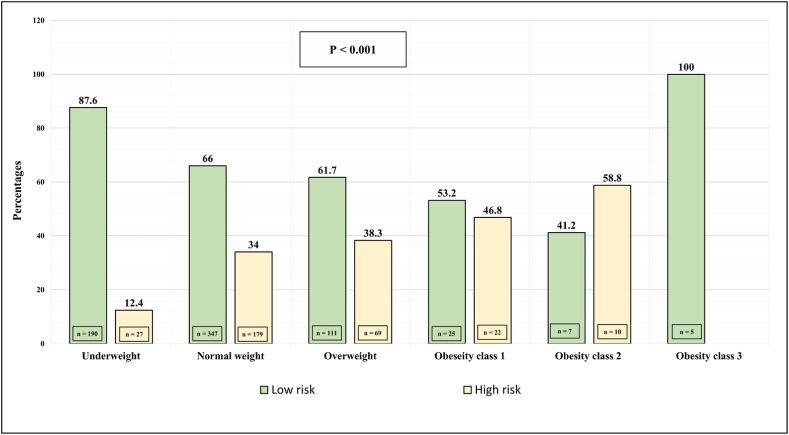

Figure 1 displays the comparison of risk of developing eating disorders across BMI categories. A significant difference in this risk was observed across the BMI classes (p < 0.001): the highest risk was among participants in obesity class 2 (n = 10, 58.8%) and class 1 (n = 22, 46.8%), while the lowest risk was among participants in obesity class 3 (n = 5, 100%) and those who were underweight (n = 190, 87.6%).

Figure 1.

Comparison of risk of developing eating disorders across body mass index categories. Significance level was set at alpha = 0.050. The numbers in the table denote frequency (%).

Discussion

Eating disorders most often occur during the late stage of adolescence or early adulthood and are associated with the physical, social, and psychological maturation of adolescents.18 The COVID-19 pandemic has been identified as a contributing factor in the occurrence of psychiatric disorders.19 Eating serves as a coping strategy, diverting attention away from feelings of anxiety and despair, resulting in changes in eating patterns and behaviors.20 In this study, we aimed to evaluate the changes in BMI and risk of developing eating disorders across several factors among female students from a single university during the COVID-19 pandemic. As per the results, a sizable proportion of the participants were at an elevated risk of developing eating disorders. Further, marital status was significantly associated with weight status, with more than half of divorced participants being overweight.

Quiles Marcos et al. reported the influence of family and peers on eating behaviors and body image dissatisfaction among females.21 Even in the Saudi context, peers can become a source of external pressure on female university students to lose weight.14 We found a relatively elevated risk of developing eating disorders among female university students, which could be attributed to the fact that the majority lived with their parents and had siblings.

Regarding the association between lifestyle changes during the COVID-19 pandemic and eating disorders, our results revealed that the highest risk of developing eating disorders was among those who increased their fast food consumption and went swimming, while the lowest was among those who engaged in other forms of exercise. These observations are consistent with the finding that eating disorders are more prevalent among athletes than the general population, female than male athletes, and among those who participate in leanness-dependent and weight-dependent sports such as swimming.22 Further, our result that there was no association between the risk of developing eating disorders and with whom the participants were eating was in agreement with that of Badrasawi et al., who showed that eating disorders were not associated with whether an individual ate alone or with family; however, Badrasawi et al. also showed that eating disorders were not correlated with fast food consumption, which contradicts our results.23 In our study, the highest proportion of participants with an elevated risk of developing eating disorders was among those living alone, which is consistent with Martínez-González et al.24 Our finding that participants from the literature college had the highest risk of developing eating disorders is inconsistent with Alwosaifer et al.,14 who found no significant risk among different specialty colleges. This could be explained by the fact that literature students may have experienced the ramifications of the lockdown to a greater degree than their counterparts from other colleges given that their curricula have no laboratory/practical onsite component.

Cobb et al. found that an increase in spousal BMI affects women's BMI and that their obesity status and BMI changes are associated depending on whether they live together and share similar behaviors.25 These findings are consistent with our results, according to which the highest BMIs were among divorced participants. This could be explained by the fact that divorced women might experience poor mood and psychiatric states, triggering emotional eating as a coping mechanism.26 This is consistent with Dooley-Hash et al., who found an association between eating disorders and depression in females.27 Moreover, our study is consistent with Alwosaifer et al.,14 who found no significant association between monthly family income and BMI.

Our study assessed the association between changes in food consumption and exercise habits and the risk of developing eating disorders. The results demonstrated a significant relationship between fast food consumption during the pandemic and BMI, which is similar to AlTamimi et al.'s finding that a higher intake of fast food is a risk factor for obesity.28 We also observed a significant association between type of exercise practiced during the pandemic and BMI. Overweight participants generally walked, performed home workouts, and went to the gym compared with those who went swimming and practiced other types of exercise. This could be explained by the nature of the motivation to engage in each type of exercise. The former might be motivated by the desire to lose weight, whereas the latter by the desire to practice their hobby or compete. Interestingly, the distribution of the risk of developing eating disorders was significantly different across participants practicing diverse types of exercise, with the highest risk found among those who went swimming and the lowest among those who practiced other exercises.

First, although the study provides evidence regarding the risk of eating disorders among female students at one university, this is also a limitation as the results are not representative of female university students across KSA. Therefore, the results cannot be generalized to other settings. Eating disorders are relatively rare among the general population and patients tend to deny and avoid professional help. This limits the value of community studies, which can underestimate the occurrence of eating disorders in the population. Therefore, future epidemiological studies should use psychiatric case registers or medical records from hospitals.13 Second, as most participants had a moderate to high family income, future studies should be conducted on those with low socioeconomic status. Third, we used self-reported height and weight data to calculate BMI, which may pose a concern as individuals tend to report themselves as thinner, healthier, and more active than they are. More controlled studies are needed to assess causality between eating disorders and sociodemographic profiles. In future studies, assessments of dietary habits (number of meals and snack consumption) and psychological and psychiatric assessment using validated questionnaires will add value. Lastly, the preexisting baseline prior to the pandemic was not evaluated for comparison.

Conclusion

The main aim of our study was to investigate the tendency toward eating disorders among female students from a single university during the COVID-19 outbreak. Our results showed an elevated risk of developing eating disorders among the students. Interestingly, this elevated risk was particularly noticeable among those who increased their fast-food consumption and who went swimming during the pandemic, and among those from the college of literature. Despite some limitations, our results emphasize the need for nutritional support and education on proper eating behaviors for female university students that can be offered by dietary specialists. We recommend developing educational programs to increase the level of awareness regarding appropriate nutrition in relation to body weight. An optional course at the university will also be useful.

Source of funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for- profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Princess Norah bint Abdulrahman University Institutional Review Board in December of 2020, with a log number of 20-0507.

Authors contributions

JA designed and conducted the study and provided the research materials. DA collected, organized, and interpreted the data. SA wrote the initial and final drafts of the manuscript. SAA analyzed the data and revised the final draft of the manuscript. GE and RAA contributed in writing the final draft and critically revised he manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors have critically reviewed and approved the final draft and are responsible for the content and similarity index of the manuscript.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Al-Adawi for sharing the Arabic version of the EAT-26 questionnaire and Amel Fayed for her helpful comments.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Taibah University.

References

- 1.Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research Eating disorders. Mayo Clinic. 2018 February 22 https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/eating-disorders/symptoms-causes/syc-20353603 Retrieved December 7, 2021, from. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mehler P.S., Rylander M. Bulimia Nervosa - medical complications. J Eat Disord. 2015;3:12. doi: 10.1186/s40337-015-0044-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mitchell J.E., Specker S.M., de Zwaan M. Comorbidity and medical complications of bulimia nervosa. J Clin Psychiatr. 1991;52(Suppl):13–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mitchell J.E., Seim H.C., Colon E., Pomeroy C. Medical complications and medical management of bulimia. Ann Intern Med. 1987;107:71–77. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-107-1-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kendler K.S., Walters E.E., Neale M.C., Kessler R.C., Heath A.C., Eaves L.J. The structure of the genetic and environmental risk factors for six major psychiatric disorders in women. Phobia, generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, bulimia, major depression, and alcoholism. Arch Gen Psychiatr. 1995;52:374–383. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950170048007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tavolacci M.P., Ladner J., Déchelotte P. Sharp increase in eating disorders among university students since the COVID-19 pandemic. Nutrients. 2021;13:3415. doi: 10.3390/nu13103415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leung J., Chung J.Y.C., Tisdale C., Chiu V., Lim C.C.W., Chan G. Anxiety and panic buying behaviour during COVID-19 pandemic-a qualitative analysis of toilet paper hoarding contents on Twitter. Int J Environ Res Publ Health. 2021;18:1127. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18031127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lakhan R., Agrawal A., Sharma M. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and stress during COVID-19 pandemic. J Neurosci Rural Pract. 2020;11:519–525. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1716442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Al-Musharaf S. Prevalence and predictors of emotional eating among healthy young Saudi women during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nutrients. 2020 Sep 24;12(10):2923. doi: 10.3390/nu12102923. PMID: 32987773; PMCID: PMC7598723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Di Renzo L., Gualtieri P., Pivari F., Soldati L., Attina A., Cinelli G., et al. Eating habits and lifestyle changes during COVID-19 lockdown: an Italian survey. J Transl Med. 2020;18:229. doi: 10.1186/s12967-020-02399-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shah M., Sachdeva M., Johnston H. Eating disorders in the age of COVID-19. Psychiatry Res. 2020;290:113122. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rowe E. Early detection of eating disorders in general practice. Aust Fam Physician. 2017;46:833–838. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alhusseini N., Alqahtani A. Covid-19 pandemic's impact on eating habits in Saudi Arabia. J Public Health Res. 2020;9:1868. doi: 10.4081/jphr.2020.1868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alwosaifer A., Alawadh S., Wahab M., Boubshait L., Almutairi B. Eating disorders and associated risk factors among Imam Abdulrahman bin Faisal University preparatory year female students in Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 2018;39:910–921. doi: 10.15537/smj.2018.9.23314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abd El-Azeem Taha AA, Abu-Zaid HA, El-Sayed Desouky D. Eating disorders among female students of Taif University, Saudi Arabia. Arch Iran Med (n.d.). Retrieved December 26, 2021, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29688736/. [PubMed]

- 16.Garner D.M., Garfinkel P.E. The Eating Attitudes Test: an index of the symptoms of anorexia nervosa. Psychol Med. 1979 May;9(2):273–279. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700030762. PMID: 472072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Al-Adawi S., Dorvlo A.S., Burke D.T., Moosa S., Al-Bahlani S. A survey of anorexia nervosa using the Arabic version of the EAT-26 and “gold standard” interviews among Omani adolescents. Eat Weight Disord. 2002;7:304–311. doi: 10.1007/BF03324977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.World Health Organization . World Health Organization; 2021 December 7. Body mass index - BMI.https://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/disease-prevention/nutrition/a-healthy-lifestyle/body-mass-index-bmi Retrieved December 7, 2021, from. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guessoum SB, Lachal J, Radjack R, Carretier E, Minassian S, Benoit L, Moro MR. Adolescent psychiatric disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown. Psychiatr Res (n.d.). Retrieved December 26, 2021, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32622172/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Potenza MN, Yau YHC. Stress and eating behaviors. Minerva Endocrinol (n.d.). Retrieved December 26, 2021, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24126546/. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Quiles Marcos Y., Quiles Sebastián M., Pamies Aubalat L., Botella Ausina J., Treasure J. Peer and family influence in eating disorders: a meta-analysis. Eur Psychiatr. 2012;28:199–206. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2012.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sundgot-Borgen J., Torstveit M. Prevalence of eating disorders in elite athletes is higher than in the general population. Clin J Sport Med. 2004;14:25–32. doi: 10.1097/00042752-200401000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Badrasawi M., Zidan S. Binge eating symptoms prevalence and relationship with psychosocial factors among female undergraduate students at Palestine Polytechnic University: a cross-sectional study. J Eat Disord. 2019;7:33. doi: 10.1186/s40337-019-0263-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martinez-Gonzalez M., Gual P., Lahortiga F., Alonso Y., Irala-Estevez J., Cervera S. Parental factors, mass media influences, and the onset of eating disorders in a prospective population-based cohort. Pediatrics. 2003;111:315–320. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.2.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cobb L., McAdams-DeMarco M., Gudzune K., Anderson C., Demerath E., Woodward M., et al. Changes in body mass index and obesity risk in married couples over 25 years. Am J Epidemiol. 2015;183:435–443. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwv112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sbarra D.A., Emery R.E., Beam C.R., Ocker B.L. Marital dissolution and major depression in midlife. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2014;2:249–257. doi: 10.1177/2167702613498727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dooley-Hash S., Adam M., Walton M., Blow F., Cunningham R. The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in adult emergency department patients. Int J Eat Disord. 2019;52:1281–1290. doi: 10.1002/eat.23140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.AlTamimi A.A., Albawardi N.M., AlMarzooqi M.A., Aljubairi M., Al-Hazzaa H.M. Lifestyle behaviors and socio-demographic factors associated with overweight or obesity among Saudi females attending fitness centers. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2020;13:2613–2622. doi: 10.2147/DMSO.S255628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]