Abstract

Background

Long-term opioid treatment in patients with chronic pain is often ineffective and possibly harmful. These patients are often managed by GPs who are calling for a clear overview of effective opioid reduction strategies for primary care.

Aim

To evaluate effectiveness of opioid reduction strategies applicable in primary care for patients with chronic pain on long-term opioid treatment.

Design and setting

Systematic review of controlled trials and cohort studies performed in primary care from inception date to 15 January 2021.

Method

Literature search conducted in EMBASE, MEDLINE, Web of Science, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, CINAHL, Google Scholar, and PsycINFO. Studies evaluating opioid reduction interventions applicable in primary care among adults on long-term opioid treatment for chronic non-cancer pain were included. Risk of bias was assessed using the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool (version 2) (RoB 2) or the Risk of bias in non-randomized studies — of interventions (ROBINS-I) tool. Narrative synthesis was performed because of clinical heterogeneity in study designs and types of interventions.

Results

In total, five randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and five cohort studies were included (N = 1717, range n = 35 to n = 985) exploring various opioid reduction strategies. Of these, six studies had high/critical RoB, three moderate RoB, and one low RoB. Three cohort studies: investigating a GP-supervised opioid taper (critical ROBINS-I), an integrative pain treatment (moderate ROBINS-I), and group medical visits (critical ROBINS-I) demonstrated significant between-group opioid reduction.

Conclusion

Results carefully point in the direction of a GP supervised tapering and multidisciplinary group therapeutic sessions to reduce long-term opioid treatment. However, because of high risk of bias and small sample sizes, no firm conclusions can be made demonstrating the need for more high-quality research.

Keywords: chronic pain, family practice, opioid, opioid epidemic, patient care, systematic review

INTRODUCTION

Where opioids once were the panacea to chronic non-cancer pain (CNCP), today the negative effects of opioids are well known. Short-term side effects of opioids include, among others, sedation and respiratory depression.1 Opioids, also when prescribed by a doctor, are addictive in nature and may lead to tolerance, dependence, and addiction.2–4 Various observational studies suggest a dose-dependent association between long-term opioid treatment (LTOT) and an increased risk of myocardial infarction, fractures, falls, and even all-cause mortality.5,6 In addition, a growing amount of evidence indicates no difference in short-term effectiveness of opioid and non-opioid therapy for CNCP.5 Research on long-term effectiveness of opioids on CNCP is still scarce, but limited available evidence suggests merely a weak effect of LTOT on pain relief in CNCP.7–9 Considering these serious harms and limited effectiveness, clinical guidelines on the management of CNCP no longer recommend opioid treatment.8,10–12

Key to turning the tide against the opioid epidemic is to reduce LTOT in patients with CNCP. In the US the estimated prevalence of LTOT among patients with CNCP ranges between approximately 1 and 9%.13 GPs have by default become responsible for reducing LTOT because of waiting lists at addiction clinics and pain centres. Yet, qualitative research among GPs report that GPs around the world feel ill equipped to reduce opioid use in these patients.14,15 In other words, GPs playing a pivotal role in the opioid epidemic call for a clear overview of effective opioid reduction strategies that they can safely use in primary care.

Recently, three systematic reviews were published on effectiveness of opioid reduction strategies in CNCP;16–18 two of these reviews searched the literature up to 2017, whereas several trials have been published in more recent years.19–24

In addition, all three reviews looked at all available opioid reduction strategies and, thus, also included strategies that are not applicable in primary care. The present systematic review was specifically aimed at evaluating the most recent evidence on effectiveness of opioid reduction strategies for patients with CNCP on LTOT that are applicable in primary care.

METHOD

This systematic review is reported according to the Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.25 The review protocol was pre-registered in PROSPERO (CRD42021236399).

How this fits in

| Though GPs are key players in tackling the opioid crisis, they feel ill equipped to reduce long-term opioid treatment (LTOT) in patients with chronic pain. This systematic review aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of opioid reduction strategies for primary care. The results from this systematic review suggest that multidisciplinary GP-supervised and multidisciplinary group-based therapeutic sessions may be effective in reducing and discontinuing LTOT. However, because of high risk of bias and small sample sizes, no strong conclusions can be made, demonstrating the need for further high-quality research in this field. |

Data source and search strategy

Searches were carried out in EMBASE, MEDLINE (Ovid), Web of Science Core Collection, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, CINAHL, Google Scholar, and PsycINFO, from inception date to 15 January 2021 without restriction on language. The complete search strategy is presented in Supplementary Box S1. Backward citation tracking of eligible studies and backward snowballing of recent reviews16–18 were performed.

Selection of studies

Studies evaluating opioid reduction interventions applicable in primary care among adults on LTOT for CNCP were included. The first and second authors (reviewers) independently screened the articles by title and abstract using eligibility criteria presented in Box 1. All studies deemed eligible by at least one reviewer were read in full for eligibility by the same two reviewers. Where consensus between reviewers was not reached, a third reviewer (fifth author) was consulted.

Box 1.

Eligibility criteria

| Study inclusion criteria |

| Randomised controlled trial or cohort study with control group |

| Evaluates an intervention aimed to facilitate opioid dose reduction or discontinuation |

| Performed on patients aged ≥18 years |

| Performed on patients with chronic non-cancer pain, that is, non-cancer pain lasting>3 months |

| Performed receiving long-term opioid treatment prescribed by, and legally obtained through, a physician |

| Performed in primary care or intervention is applicable in primary care |

| Reports on opioid reduction in mg morphine equivalent daily dose (MEDD) |

| Published and presented in full text |

|

|

| Study exclusion criteria |

| Includes pregnant patients |

| Includes patients with an oncological diagnosis |

| Includes patients receiving palliative treatment |

| Includes patients with acute or subacute pain, that is, pain lasting <3 months |

| Includes patients with opioid treatment <3 months |

Data extraction and risk of bias assessment

Study characteristics were extracted by the first author and checked by the second. Outcome data were extracted independently by both the first and second authors using a standardised extraction form. Data extracted included, among others, intervention characteristics; comparison characteristics; primary outcome measures (mean opioid dose in mg morphine equivalent daily dose [MEDD] at baseline and end-of-intervention and/or mean opioid dose change); and secondary outcome measures (opioid discontinuation rates, incidence of adverse events, withdrawal symptoms, physical functioning, measures of mental wellbeing, and overall quality of life). For cohort studies, outcome data at the last available timepoint when still receiving the intervention were extracted and, for studies that did not report outcome at end-of-intervention, outcome data at the next available timepoint were extracted.

The first and second authors independently assessed risk of bias of the included studies using the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool (version 2) (RoB 2) for randomised controlled trials26 and Risk of bias in non-randomized studies — of interventions tool (ROBINS-I) for non-randomised studies.27 Disagreements between reviewers were solved by consensus.

Data synthesis

Due to substantial clinical heterogeneity in type of interventions and study designs, though a priori planned, meta-analysis was not possible and a narrative synthesis approach was adopted following the Synthesis without meta (SWiM) analysis guideline.28 Effectiveness of interventions is presented as between-group differences and/or (if between-group differences were not available or if the outcome at baseline was significantly different between the groups) as within-group difference. Adjusted analysis correcting for baseline imbalances were presented if these resulted in a different conclusion.

RESULTS

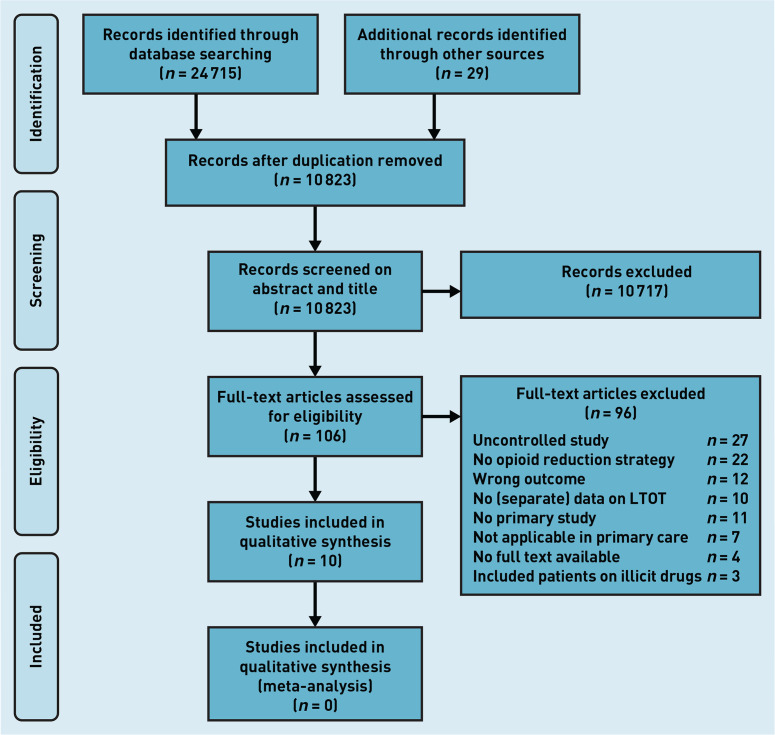

The search initially retrieved 10 823 studies after removing duplicates. Of these, 106 studies were selected based on their abstracts and titles, and read in full. The corresponding authors of seven of these studies were contacted through mail because information on inclusion criteria was missing. All but one author responded to this mail. After review, 10 studies19–24, 29–32 met the inclusion criteria and were included in this review (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart: selection process for systematic review on opioid reduction for patient with chronic pain in primary care. LTOT = long-term opioid treatment.

Study characteristics

The 10 included studies comprised N = 1717 (range n = 35 to n = 985) patients. Five studies19,21,29,31,32 were randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and five studies20,22,23,24,30 were cohort studies. A variety of opioid reduction methods, from tapering protocols to alternative care strategies, were explored. Supplementary Table S1 includes a summary of studies and patient characteristics included in this systematic review.

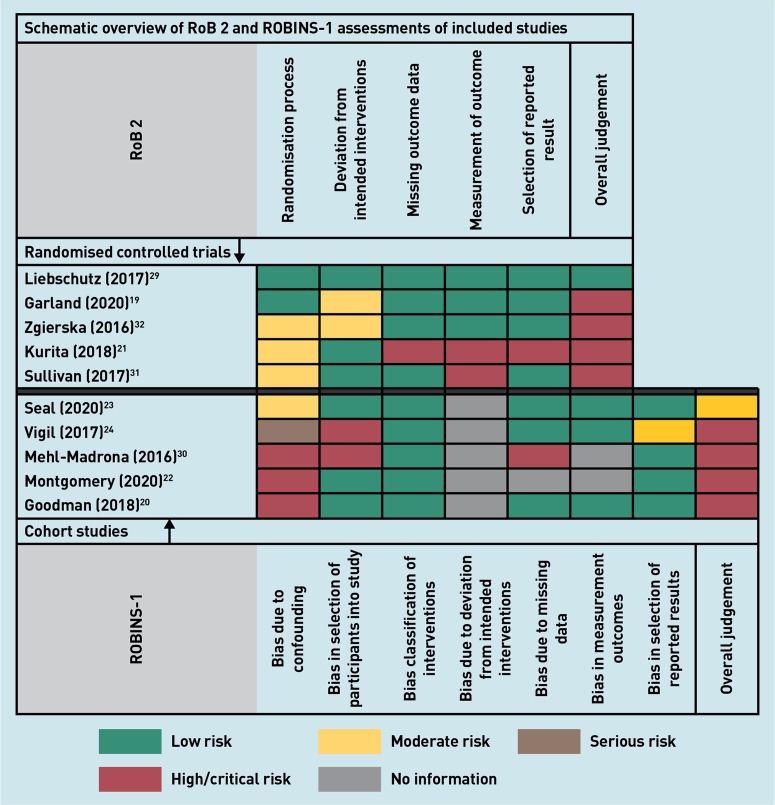

Risk of bias

One RCT29 had low risk of bias, two RCTs19,32 had some concerns because of non-blinding of research participants and research staff, and the two remaining RCTs21,31 had high risk of bias (Figure 2). One cohort study23 had moderate risk of bias; the remaining four studies20,22,24,30 had a critical risk of bias (Figure 2). Complete RoB 2 and ROBINS-I assessments of the included cohort studies are presented in Supplementary Boxes S2 and S3.

Figure 2.

Schematic overview of RoB 2 and ROBINS-1 assessments of included randomised controlled trials and cohort studies. RoB 2 = Cochrane risk-of-bias tool. ROBINS-1 = Risk of bias in non-randomized studies — of interventions tool.

Narrative summary of results

None of the included RCTs demonstrated a significant between-group difference in opioid dose. Three out of the five relatively small cohort studies,20,23,30 one with a moderate risk in bias (n = 294) and two with a critical risk in bias (n = 84 and n = 41), demonstrated a significant between-group difference in opioid reduction favouring the experimental intervention groups. The interventions researched by these cohort studies varied from multidisciplinary pain treatment,23 group therapeutic sessions,30 to an individually tailored taper plan.20

Narrative synthesis per study

A narrative synthesis of the included studies, primary outcomes, and a brief discussion of secondary outcomes is presented below. An overview and thorough explanation of outcomes is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Schematic overview of study results on primary and secondary outcomes

| Study | Study design | n (total) | Intervention versus control | Risk of biasa | Primary outcome | Secondary outcomes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Opioid dose,b,c mg mean difference (95% CI and/or P-value) | Discontinuation rate, %b (95% CI and/or P-value) | Paind (95% CI and/or P-value) | Physical functionb (P-value) | Mental wellbeingb (95% CI) | |||||

| Liebschutz (2017)29 | RCT | 985 | TOPCARE versus electronic decision tool | Low risk | 6.5 (P = 0.31) | −4.5 (P= 0.08) | |||

| Garland (2020)19 | RCT | 95 | MORE versus active support group | Some concerns | 110.6e,f | ||||

| Zgierska (2016)32 | RCT | 35 | Meditation-cognitive behavioural therapy versus usual care for CNCP | Some concerns | 5.7 (−34.3 to 45.7)g | 0.9 (0.01 to 1.7)g | 1.9 (−5.5 to 9.3)g | −0.4 (−5.2 to 4.4)g | |

| Kurita (2018)21 | RCT | 35 | Taper off versus usual care | High risk | 74.2 (P= 0.446)h | −0.2 (P= 0.968) | |||

| Sullivan (2017)31 | RCT | 35 | Taper support intervention versus usual care | High risk | 57.91f,i | 0.68 (0.64 to 2.01; P= 0.30)j | |||

| Seal (2020)23 | Cohort | 294 | Integrative pain team treatment versus usual primary care | Moderate | 38.7 mg (P= 0.03)k | ||||

| Vigil (2017)24 | Cohort | 66 | Medical cannabis programme versus usual care | Critical | −0.1 mg (P= 0.0974) | −37.1 (P<0.001) | |||

| Mehl-Madrona (2016)30 | Cohort | 84 | Group medical visit versus usual care | Critical | 53.7f,l | −19 (P<0.001) | |||

| Montgomery (2020)22 | Cohort | 47 | Battlefield acupuncture versus usual care | Critical | 18.85f | 0 (P= 0.15) | |||

| Goodman (2018)20 | Cohort | 41 | Individually tailored opioid taper versus treatment in medical pain clinic | Critical | 118.26 (23.23 to 213.31; P= 0.018) | ||||

RCTS were assessed using the RoB 2 tool and cohort studies were assessed using ROBINS-I.

Mean between-group difference comparing control with intervention group at end-of-intervention, unless stated differently.

Measured in mg of morphine equivalent daily dose (MEDD).

Pain severity on a numeric rating scale (NRS).

Measured at 4 weeks after intervention was completed.

P-values or confidence interval were not reported.

This value is a mean change difference comparing control with intervention.

Because of excessive drop-out rate, data assessment was performed at 3.5 months’ follow-up.

In an adjusted analysis for baseline imbalances, the mean between-group difference in MEDD was −42.9 mg (95%CI = −92.42 to 6.62, P=0.09).

Numbers based on the adjusted analysis for baseline imbalances.

Of note, participants in the integrative pain team group reported higher opioid misuse rates and were diagnosed more often with an opioid use disorder. In adjusted analysis controlling for these and other baseline imbalances using a mixed-effects linear regression model, the between-group difference remained significant with a mean between-group difference of 38.2, 95%CI = 13.0 to 63.5 mg, P<0.01.

The within-group differences comparing opioid dose at end-of-intervention with baseline were significant, mean difference intervention group −49.7 mg MEDD, mean difference control group +14.0 mg MEDD, both with P<0.001. Note that, initially, 207 participants attended the intervention, yet the analysis of the intervention’s effect was performed using data from the 42 participants who had attended the intervention for at least 6 months. CI = confidence interval. CNCP = chronic non-cancer pain. MORE = Mindfulness-oriented recovery enhancement. RCT = randomised controlled trial. RoB 2 = Cochrane risk of bias tool (version 2). ROBINS-1 = Risk of bias in non-randomized studies — of interventions tool. TOPCARE = Transforming opioid prescribing in primary care.

Description of results in RCTs

Liebschutz (2017).29

In this cluster RCT (n = 985), 1 year of an intervention, Transforming opioid prescribing in primary care (TOPCARE), consisting of nurse care management, electronic registry, academic detailing, and electronic decision tools was compared with 1 year of electronic decision tools only. There was no significant between-group difference in opioid dose at end-of-intervention (mean difference 6.5 mg MEDD, P = 0.31). An adjusted regression analysis accounting for baseline imbalances demonstrated a statistically significant lower opioid use in the TOPCARE group (mean difference [standard deviation] 6.8 [SD 1.6] mg MEDD, P<0.001). Additionally, a non-statistically significant difference in opioid discontinuation among the groups was reported.

Garland (2020).19

In this RCT (n = 95), Mindfulness-oriented recovery enhancement (MORE), consisting of 8 weekly 2-hour mindfulness group sessions and daily 15-minute mindfulness practices at home, was compared with an active support group in which the group sessions consisted of discussions on chronic pain and opioid reduction. In both groups there was no explicit call made to reduce opioid treatment. The study did not report on opioid dose at end-of-intervention, but at 1 month after intervention. The between-group mean difference was 110.6 mg MEDD in favour of the intervention (confidence intervals and P-values not provided). An intention-to-treat analysis using a linear mixed model with an interaction of group and time demonstrated a statistically significant between-group difference (P = 0.006).

Zgierska (2016).32

In this RCT (n = 35), patients were randomised to either meditation-cognitive behavioural therapy, consisting of 2-hour weekly group sessions and encouragement in formal mindfulness, or usual care. At the end-of-intervention period, groups did not significantly differ in opioid dose change (mean difference 5.7 mg MEDD, 95% confidence interval (CI) = −34.3 to 45.7). Additionally, a significant between-group change in pain severity was reported in favour of the experimental intervention. There was no significant between-group difference in change in physical function or in perceived stress.

Kurita (2018).21

In this RCT (n = 35), all included participants were (if needed) switched to sustained-release opioid therapy, after which they were randomised to either a taper-off intervention group or usual care. The intervention consisted of motivational talks and weekly or bi-weekly 10% reduction of opioid dose until discontinuation. Because of a large participant drop-out, outcome assessments were performed at 3.5 months. The mean between-group difference in opioid use was not statistically significant (mean difference 74.2 mg MEDD, P = 0.446). Additionally, the study reported no significant between-group difference in pain severity.

Sullivan (2017).31

In this RCT (n = 35), participants interested in tapering their opioid dose were randomly assigned to either a taper support intervention or usual care. The intervention consisted of one visit with a physician followed by 17 weekly sessions in cognitive behavioural therapy for chronic pain with a physician assistant followed by weekly dose reduction of 10%. Between-group mean difference was 57.91 mg MEDD in favour of the taper support intervention (confidence interval and P-value not reported). Adjusted analysis for baseline imbalances reported a non-significant between-group difference in MEDD (mean difference −42.9 mg MEDD, 95% CI = −92.42 to 6.62, P = 0.09) and pain severity.

Description of results in cohort studies

Seal 2020.23

In this cohort study (n = 294), participants receiving consultations from an integrated pain team, consisting of primary care providers with training in pain management, pain pharmacists, and pain psychologists, were compared with participants receiving usual primary care (moderate ROBINS-I). At 6 months the mean between-group difference in opioid reduction was statistically significant in favour of the experimental intervention (mean difference 38.7 mg MEDD, P<0.03).

Vigil 2017.24

In this cohort study (n = 66), participants enrolled in a medical cannabis programme were compared with participants who had declined the offer to enrol in the programme. The difference in opioid dose was non-statistically significant between groups (mean 0.1 mg MEDD, P = 0.974). The patients in the cannabis programme were significantly more likely to discontinue their opioid treatment.

Mehl-Madrona 2016.30

In this cohort study (n = 84), participants attending group medical visits (GMVs) at least twice monthly, in which non-pharmacological, complementary, and alternative therapy were encouraged for the treatment of pain, were matched with participants receiving usual care in the same age decile, with same major diagnosis, same sex, and within 25% in mg MEDD (critical ROBINS-I). At end-of-intervention (range 6 months to 2.5 years) a statistically significant mean between-group difference of 53.7 mg MEDD was reported in favour of the intervention (CI and P-value were not reported). Additionally, a statistically significant difference in between-group discontinuation rate in favour of the intervention was reported. Differences in pain severity and quality of life were only reported for the intervention group, both demonstrating a statistically significant within-group change.

Montgomery (2020).22

In this cohort study (n = 47), battlefield acupuncture (BFA), a unique five-point auricular acupuncture procedure, was compared with usual care in patients on long-term opioid pain contract. The study reported a non-significant between-group mean difference of 18.85 mg MEDD (CI and P-value not provided). Of note, both groups increased opioid dose over the course of the study (mean difference BFA +3.9 mg MEDD, control +8.7 mg MEDD, CI and P-values not provided). The study reported no significant difference in pain severity.

Goodman (2018).20

In this cohort study (n = 41), patients had a conversation with their family GP discussing opioid cessation, after which they could choose either individually tailored opioid tapering by their family GP or further pain treatment at a medical pain clinic (critical ROBINS-I). A statistically significant between-group difference in opioid use in favour of the GP-supervised tapering was reported (mean difference 118.26 mg MEDD, 95% CI = 23.23 to 213.31, P = 0.018). However, the groups differed significantly in mean opioid dose at baseline with a higher opioid dose in the control group (mean difference 142.15 mg MEDD, 95% CI = 51.69 to 232.62, P = 0.005). Within-group difference comparing opioid dose at baseline with opioid dose at end-of-intervention demonstrated a significant reduction in the GP-supervised tapering group (mean difference 14.85 mg MEDD, 95% CI = 5.58 to 24.12, P = 0.003) and a non-significant reduction in the control group (mean change 38.74 mg MEDD, 95% CI = −42.88 to 120.368, P = 0.324).

DISCUSSION

Summary

A total of five RCTS and five cohort studies were included in this systematic review. Studies were generally small and overall risk of bias was high. One RCT was graded low-risk bias29 (RoB 2 tool) but none of the cohort studies received this grading (ROBIN-S tool). There were some overarching principles explored: five studies19,23,30–32 used psychological interventions as part of the intervention, four studies19,23,30,32 explored the effect of therapeutic group sessions, and three studies20,21,31 looked at opioid tapering. None of the RCTs demonstrated a significant between-group difference in opioid dose. Three out of the five cohort studies20,23,30 demonstrated a significant between-group difference in opioid reduction favouring the experimental intervention groups.

The results from this systematic review suggest that multidisciplinary GP-supervised and multidisciplinary group-based therapeutic sessions may be effective in reducing and discontinuing LTOT. However, because of high risk of bias and small sample sizes, no strong conclusions can be made, demonstrating the need for further high-quality research in this field.

Strengths and limitations

Conclusions of this systematic review are not without limitations. A comparison of study results was proposed by extracting between-group difference at end-of-intervention. However, in two studies, by Garland et al19 and Kurita et al,21 these results were not provided. In Kurita et al (2018),21 because of loss of follow-up the extraction timepoint was brought forward, that is, before the end-of-intervention was reached, causing possible bias away from the null. Whereas, in Garland et al (2020),19 the extraction timepoint was 10 weeks after intervention, creating possible bias towards the null.

The generalisability of findings presented in this review to countries outside of the US is limited, since all but one study was performed in the US. It cannot be simply assumed that effectiveness of strategies for patients with CNCP on LTOT is the same all over the world, especially since the opioid crisis in the US has been found to be very different compared with Europe and the rest of the world.33 Moreover, to compare effectiveness equally and objectively among all included studies, 12 studies were excluded as they did not report opioid dose reduction in MEDD. However, though excluded from this review, they might have reported on effective opioid reduction interventions.

Finally, studies were excluded if they were considered not applicable in primary care, which was at the discretion of the first and second reviewers, who based their opinions on the types of strategies that would be applicable in the Netherlands and Denmark. Since primary care services vary from country to country, studies might have been included (or excluded) that could not (or could) have been implemented in the primary care of other countries.

Comparison with existent literature

This systematic review included one RCT19 that was not included in two most recent systematic reviews.17,18 Additionally, four new cohort studies,20,22–24 which had not been included in the most recent systematic review,16 were included. Hence, this review is, to the authors’ knowledge the most up-to-date review discussing intervention effectiveness in studies exploring opioid reduction strategies for patients with CNCP on LTOT applicable in primary care. Moreover, this is the first review that has included only studies on opioid reduction strategies that are applicable in primary care.

Though this review specifically explored reduction strategies applicable in primary care, the overall conclusion is in line with other recent reviews,16–18 namely that no strong conclusions can be made regarding the benefit of opioid reduction strategies for people with CNCP due to overall high risks of bias and small sample sizes. With five new and recent studies identified,19,20,22–24 the presented review demonstrates a fast growth of studies exploring opioid reduction strategies.

Implications for research and practice

This review demonstrates the need for more high-quality research on opioid reduction strategies for patients with CNCP on LTOT. The fact that multiple research protocols for future research in this field were identified while scanning abstracts and titles34–37 can be seen as a step in the right direction. These upcoming studies should build on lessons learned. Future research should include high-quality RCTs, blinded for patients or at least for research personnel, where possible, to reduce risks of bias. In addition, large drop-out rates, demonstrated by some included studies,19,21,30 can be expected and studies should opt for larger sample sizes than strictly needed to secure sufficient statistically powerful end results. In addition, it would be worthwhile for pilot trials to evaluate methods of retaining patients before performing large-scale trials and to investigate, through qualitative evaluations, the reasons for patient drop-out.

Moreover, to successfully evaluate a reduction strategy, patient outcomes, such as pain severity and quality of life, should be assessed throughout the study to map the risks and benefits of opioid reduction strategies as these outcome measures are important topics in patient–doctor conversations on reducing opioids.16 Moreover, to increase generalisability of results, studies should be performed in more countries around the world.

Considering increasing waiting lists at pain clinics and rehabilitation centres, the positive outcome of Goodman et al,20 might inspire GPs to start with individually tailored opioid taper plans with patients who are receptive to that idea while taking the study’s limitations into consideration. Likewise, study results of Seal et al23 and Mehl-Madrona et al30 carefully point in the direction of multidisciplinary group therapeutic sessions with a role for non-pharmacological pain treatments. High drop-out rates in some studies19,21,30 suggest a need for close monitoring of patients when reducing their opioid treatment. Here, time is of the essence, something that is not always available in general practice. A role for nurse practitioners, as was proposed by Liebschutz et al,29 may be a solution; however, this will have to be investigated in more depth.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Elise Krabbendam, biomedical information specialist from the Erasmus MC Medical Library, for developing and updating the search strategy.

Funding

This research is part of a project financed by a grant from the Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development (ZonMW, grant number: 80-83911-98-1150). No other funds were received. The funders had no role in the design and conduct of this study.

Ethical approval

Not required.

Data

Systematic review protocol is available at PROSPERO 2021 CRD42021236399: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42021236399. Extraction forms are available from the corresponding author. The complete search strategy is available in Supplementary Box S1. The complete RoB 2.0 assessments and complete ROBINS-1 assessments are available in Supplementary Boxes S2 and S3, respectively.

Provenance

Freely submitted; externally peer reviewed.

Competing interests

The authors have declared no competing interests.

Discuss this article

Contribute and read comments about this article: bjgp.org/letters

REFERENCES

- 1.Benyamin R, Trescot AM, Datta S, et al. Opioid complications and side effects. Pain Physician. 2008;11(2 Suppl):S105–S120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martell BA, O’Connor PG, Kerns RD, et al. Systematic review: opioid treatment for chronic back pain: prevalence, efficacy, and association with addiction. Ann Intern Med. 2007 doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-2-200701160-00006.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fishbain DA, Cole B, Lewis J, et al. What percentage of chronic nonmalignant pain patients exposed to chronic opioid analgesic therapy develop abuse/addiction and/or aberrant drug-related behaviors? A structured evidence-based review. Pain Med. 2008 doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2007.00370.x.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Højsted J, Sjøgren P. Addiction to opioids in chronic pain patients: a literature review. Eur J Pain. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2006.08.004.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chou R, Hartung D, Turner J, et al. Opioid treatments for chronic pain; comparative effectiveness review no 229. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2020. Report number 20-EHC011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chou R, Turner JA, Devine EB, et al. Ann Intern Med. 2015. The effectiveness and risks of long-term opioid therapy for chronic pain: a systematic review for a National Institutes of Health Pathways to Prevention Workshop. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Manchikanti L, Vallejo R, Manchikanti KN, et al. Effectiveness of long-term opioid therapy for chronic non-cancer pain. Pain Physician. 2011;14(2):E133–E156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Häuser W, Schug S, Furlan AD. The opioid epidemic and national guidelines for opioid therapy for chronic noncancer pain: a perspective from different continents. Pain Rep. 2017 doi: 10.1097/PR9.0000000000000599.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tucker HR, Scaff K, McCloud T, et al. Harms and benefits of opioids for management of non-surgical acute and chronic low back pain: a systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2020 doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2018-099805.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC Guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain — United States, 2016. JAMA. 2016 doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.1464.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . Chronic pain (primary and secondary) in over 16s: assessment of all chronic pain and management of chronic primary pain NG193. London: NICE; 2021. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng193 (accessed 29 Dec 2021). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Häuser W, Morlion B, Vowles KE, et al. European clinical practice recommendations on opioids for chronic noncancer pain — Part 1: Role of opioids in the management of chronic noncancer pain. Eur J Pain. 2021 doi: 10.1002/ejp.1736.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Häuser W, Petzke F, Radbruch L, Tölle TR. The opioid epidemic and the long-term opioid therapy for chronic noncancer pain revisited: a transatlantic perspective. Pain Manag. 2016 doi: 10.2217/pmt.16.5.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kennedy MC, Pallotti P, Dickinson R, Harley C. ‘If you can’t see a dilemma in this situation you should probably regard it as a warning’: a metasynthesis and theoretical modelling of general practitioners’ opioid prescription experiences in primary care. Br J Pain. 2019 doi: 10.1177/2049463718804572.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kennedy LC, Binswanger IA, Mueller SR, et al. ‘Those conversations in my experience don’t go well’: a qualitative study of primary care provider experiences tapering long-term opioid medications. Pain Med. 2018 doi: 10.1093/pm/pnx276.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frank JW, Lovejoy TI, Becker WC, et al. Patient outcomes in dose reduction or discontinuation of long-term opioid therapy: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2017 doi: 10.7326/M17-0598.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eccleston C, Fisher E, Thomas KH, et al. Interventions for the reduction of prescribed opioid use in chronic non-cancer pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;(11):CD010323. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010323.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mathieson S, Maher CG, Ferreira GE, et al. Deprescribing opioids in chronic non-cancer pain: systematic review of randomised trials. Drugs. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s40265-020-01368-y.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garland EL, Hudak J, Hanley AW, Nakamura Y. Mindfulness-oriented recovery enhancement reduces opioid dose in primary care by strengthening autonomic regulation during meditation. Am Psychol. 2020 doi: 10.1037/amp0000638.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goodman MW, Guck TP, Teply RM. Dialing back opioids for chronic pain one conversation at a time. J Fam Pract. 2018;67(12):753–757. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kurita GP, Højsted J, Sjøgren P. Tapering off long-term opioid therapy in chronic non-cancer pain patients: a randomized clinical trial. Eur J Pain. 2018 doi: 10.1002/ejp.1241.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Montgomery AD, Ottenbacher R. Battlefield acupuncture for chronic pain management in patients on long-term opioid therapy. Med Acupunct. 2020 doi: 10.1089/acu.2019.1382.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seal KH, Rife T, Li Y, et al. Opioid reduction and risk mitigation in VA primary care: outcomes from the integrated pain team initiative. J Gen Intern Med. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-05572-9.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vigil JM, Stith SS, Adams IM, Reeve AP. Associations between medical cannabis and prescription opioid use in chronic pain patients: a preliminary cohort study. PLoS One. 2017 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0187795.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Page MJ, Moher D, Bossuyt PM, et al. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021 doi: 10.1136/bmj.n160.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019 doi: 10.1136/bmj.l4898.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ. 2016 doi: 10.1136/bmj.i4919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Campbell M, McKenzie JE, Sowden A, et al. Synthesis without meta-analysis (SWiM) in systematic reviews: reporting guideline. BMJ. 2020 doi: 10.1136/bmj.l6890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liebschutz JM, Xuan Z, Shanahan CW, et al. Improving adherence to long-term opioid therapy guidelines to reduce opioid misuse in primary care: a cluster-randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Mehl-Madrona L, Mainguy B, Plummer J. Integration of complementary and alternative medicine therapies into primary-care pain management for opiate reduction in a rural setting. J Altern Complement Med. 2016 doi: 10.1089/acm.2015.0212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sullivan MD, Turner JA, DiLodovico C, et al. Prescription opioid taper support for outpatients with chronic pain: a randomized controlled trial. J Pain. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2016.11.003.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zgierska AE, Burzinski CA, Cox J, et al. Mindfulness meditation and cognitive behavioral therapy intervention reduces pain severity and sensitivity in opioid-treated chronic low back pain: pilot findings from a randomized controlled trial. Pain Med. 2016 doi: 10.1093/pm/pnw006.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Verhamme KMC, Bohnen AM. Are we facing an opioid crisis in Europe? Lancet Public Health. 2019 doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(19)30156-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cunningham CO, Starrels JL, Zhang C, et al. Medical Marijuana and Opioids (MEMO) Study: protocol of a longitudinal cohort study to examine if medical cannabis reduces opioid use among adults with chronic pain. BMJ Open. 2020 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-043400.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Darnall BD, Mackey SC, Lorig K, et al. Comparative effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy for chronic pain and chronic pain self-management within the context of voluntary patient-centered prescription opioid tapering: the EMPOWER study protocol. Pain Med. 2020 doi: 10.1093/pm/pnz285.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Manchira Krishnan S, Gc VS, Sandhu HK, et al. Protocol for an economic analysis of the randomised controlled trial of Improving the Well-being of people with Opioid Treated CHronic pain: I-WOTCH Study. BMJ Open. 2020 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-037243.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lasser KE, Shanahan C, Parker V, et al. Multicomponent intervention to improve primary care provider adherence to chronic opioid therapy guidelines and reduce opioid misuse: a cluster randomized controlled trial Protocol. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2015.06.018.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]