Abstract

Histidine-rich glycoprotein (HRGP) is a relatively less known glycoprotein, but it is abundant in plasma with a multidomain structure, which allows it to interact with many ligands and regulate various biological processes. HRGP ligands includes heme, Zn2+, thrombospondin, plasmin/plasminogen, heparin/heparan sulfate, fibrinogen, tropomyosin, IgG, FcγR, C1q. In many conditions, the histidine-rich region of HRGP strengthens ligand binding following interaction with Zn2+ or exposure to low pH, such as sites of tissue injury or tumor growth. The multidomain structure and diverse ligand binding attributes of HRGP indicates that it can act as an extracellular adaptor protein, connecting with different ligands, especially on cell surfaces. Also, HRGP can selectively target IgG, which blocks the production of soluble immune complexes. The most common cell surface ligand of HRGP is heparan sulfate proteoglycan, and the interaction is also potentiated by elevated Zn2+ concentration and low pH. Recent reports have shown that HRGP can modulate macrophage polarization and possibly regulate other physiological processes such as angiogenesis, anti-tumor immune response, fibrinolysis and coagulation, soluble immune complex clearance and phagocytosis of apoptotic/necrosis cells. In addition, it has also been reported that HRGP has antibacterial and anti-HIV infection effects and may be used as a novel clinical biomarker accordingly. This review outlines the molecular, structural and biological properties of HRGP as well as presenting an update on the function of HRGP in various physiological processes.

Keywords: Angiogenesis, Histidine-rich glycoprotein, Macrophage polarization, Thrombospondin, Tumor

Introduction

Histidine-rich glycoprotein (HRGP) is an α2-plasma glycoprotein with single polypeptide chain structure and was first isolated in 1972, which has a mass of about 75 kDa.1,2 Many vertebrates' plasma contains HRGP, such as humans, mice, rats, chickens, rabbits, etc. Several invertebrates also have HRGP in their blood.2,3 Studies have confirmed that HRGP is mainly produced by liver parenchymal cells in mammals.4, 5, 6 However, it was found that HRGP can also be synthesized in immune cells such as monocytes and macrophages,7 and megakaryocytes.8 HRGP circulates in the blood with a moderately high concentration (about 100–150 μg/ml),6,9,10 and this protein can be secreted from activated platelets.8 The plasma levels of HRGP is lowest at birth and it will gradually increase with age.6 Compared with the contents of other amino acid residues, the rather high contents of histidine and proline residues in HRGP is probably the most significant feature of HRGP, each of them accounting for about 13% of the total amino acid contents respectively.11 Liver is the main site that HRGP concentrates, and there is little HRGP around blood vessels, macrophages or in tumor environment.12 The multidomain structure is one of the characteristics of HRGP, which enable HRGP to bind various ligands, interact with diverse cell surface receptors, and be implicated in regulating numerous biological processes, especially macrophage polarization, angiogenesis, immunity moderation and hemostasis. This review will briefly describe the structure and ligands of HRGP as well as focusing on the biological activities of HRGP and their underlying mechanisms.

Part 1 – A brief description of the molecular structure of HRGP

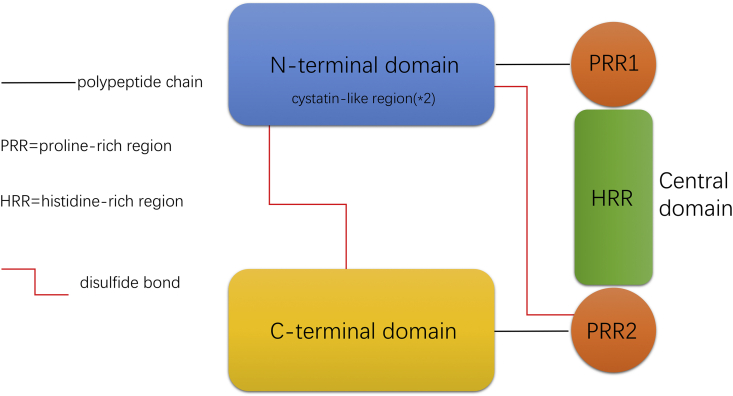

HRGP is a 507 amino acid4 multidomain polypeptide consisting of three main domains, including N-terminal domain, central domain and C-terminal domain. (1) The N-terminal domain contains two cystatin-like regions, which allows HRGP as a member of the cystatin superfamily. (2) The central domain is rich in proline and histidine residues, which can be simply divided into three part: one histidine-rich region (HRR) and two proline-rich regions (PRR). The two PRRs are located on either side of the HRR. In human form central domain, there are multiple consensus GHHPH pentapeptide tandem repeats. (3) The C-terminal domain and the central domain are connected to the cystatin-like regions in the N-terminal domain by disulfide bonds.13 The modular structure and disulfide bonds are represented as a diagram in Fig. 1. The most prominent feature of HRGP molecule is that it has abnormally high levels of histidine and proline residues, accounting for about 13% of the total amino acid content, respectively, and they are mainly concentrated in HRR and PRR.1,14,15 This is why HRGP is also called ‘histidine proline rich glycoprotein’ (HPRGP) (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Molecule structure of histidine-rich glycoprotein (HRGP). Human HRGP is comprised of three major domains; respectively, a N-terminal domain (two cystatin-like regions within it), a central domain and a C-terminal domain. In the central domain, the HRR (histidine-rich region) is flanked by two PRR (proline-rich region). The C-terminal domain and the central domain are connected to the cystatin-like regions in the N-terminal domain by disulfide bonds. GHHPH consensus regions are located in the HRR (not represented in the figure).

Part 2 – Ligands of HRGP and associated cell surface receptors

HRGP ligands

The multidomain structure gives HRGP the ability to bind to a variety of ligands, such as heme, Zn2+ and a few divalent metal cations, thrombospondin, plasmin/plasminogen, heparin/heparan sulfate, fibrinogen, tropomyosin, IgG, FcγR, C1q.13 High concentrations of Zn2+ and low pH can enhance the interaction between HRGP and its ligands under many conditions, such as in damaged tissues and tumor environments.16

HRGP cell surface receptors

HRGP has a multidomain structure and the ability to bind ligands, enabling it to bind to different cells through their surface receptors. Therefore, HRGP can bind to a wide variety of cells, including T lymphocytes,17,18 murine erythrocytes,19 EBV-transformed human B cells18 and platelets20,21 as well as endothelial,22 melanoma, ovarian,23 fibroblast,24 lymphoma25 and myeloid cell lines.26 Some receptors are mainly responsible for HRGP binding to cells, and can be broadly classified into the following four categories: heparan sulfate, tropomyosin, an unidentified 50–55 kDa protein on T cells and FcR.13 Heparan sulfate is the main receptor that mediates the binding between HRGP and cell surface, which is tightly related to the physiological function of HRGP. The interaction between HRGP and cell surface receptors provides a molecular basis for various physiological function of HRGP in vivo.

Part 3 – HRGP promotes macrophage M1 polarization and inhibits M2 polarization

Macrophage is one of the main components of innate immune system. Due to their different direction of polarization and corresponding physiological functions, macrophages can be divided into different phenotypes.27 In general, we divide macrophages into M1 and M2 phenotypes. Typically, M1 macrophage has proinflammatory effect, while M2 macrophage is an anti-inflammatory phenotype.28,29 At present, HRGP has been proved to reduce the polarization of M2 macrophages in both tumor and inflammatory environment, and may promote the polarization of M1 macrophages. However, the underlying mechanism has only been preliminarily explored in tumor environment. Moreover, HRGP does not affect the degree of macrophage infiltration while nearly only changing the macrophage phenotypes.12

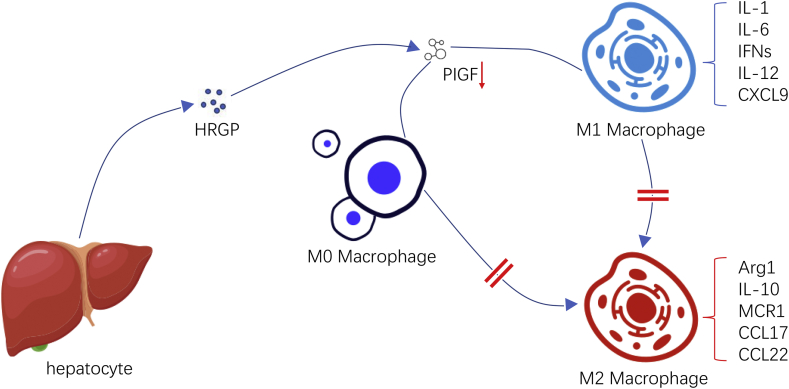

Charlotte et al demonstrated in mice tumor models that the effect of HRGP on macrophages was mediated by PIGF.12 PIGF (Placental growth factor) is a homologous of VEGF (vascular endothelial growth factor), which only interacts with VEGFR1 (vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 1) to regulate the intermolecular and intramolecular signal transduction of VEGF.30, 31, 32 In tumor microenvironment, PIGF is secreted mainly by TAM (tumor-associated macrophage) and then acts on TAM in an autocrine way, making TAM polarize toward the M2 phenotype. They found HRGP can down-regulate the expression of PIGF, thereby reducing the M2 polarization of TAM and promoting more TAM to polarize to the M1 phenotype. Interestingly, HRGP could not exert its effect on macrophage's polarization without the expression of PIGF or associated genes. However, while these studies identified down-regulation of PIGF as a downstream mechanism of HRGP's function, given its multidomain structure and binding characteristics, HRGP may also be involved in other pathways to affect this process.12 There are some other possible mechanisms for HRGP to influence M2 polarization. For example, in tumor environment, hypoxia conditions can stimulate M2-like polarization, and HRGP may indirectly influence TAM polarization by affecting oxygenation33 (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

In the tumor microenvironment, PIGF is secreted mainly by TAM and then acts on TAM in an autocrine pattern, polarizing TAM to the M2 phenotype. HRGP can downregulate the expression of PIGF, thereby reducing the M2 polarization of TAM and increasing the M1 polarization of TAM.

However, the views on whether the macrophages deviating from the polarization of M2 polarize toward the direction of M1 have not reached a consensus yet. In both inflammatory and tumor environments, experiments have demonstrated that HRGP can promote M1 polarization of macrophages.12,34,35 But some researchers believe that HRGP induces a “HRGP-specific” polarization pattern instead of re-inducing TAM into M1 phenotype. In fact, in tumor microenvironment, although HRGP down-regulates established M2 makers (Arg1, IL-10, MCR1, CCL17, CCL22)36,37 and up-regulates M1 makers (IL-1, IL-6, IFNs, IL-12, CXCL9),38 it also causes changes in gene expression, but these changes may not be typical. For example, HRGP down-regulates the expression of cytokines with pro-inflammatory activity such as TNF-α and IL-1β in M1-TAMs. IL-1β and TNF-α are M1-polarized macrophage-related cytokines,39 and this manner means that “HRGP-specific M1-TAMs” and “classical M1-polarized macrophages” may be different in tumor microenvironment. Nevertheless, under certain conditions, M1-TAMs expression of TNF-α36,40 and IL-1β39 may indeed decrease. In addition, since IL-1β promotes angiogenesis and metastasis,41 its reduction in HRGP+ tumors helps inhibit tumor metastasis and enhance vascular normalization.12 In general, HRGP-induced polarization gives TAMs the ability to inhibit tumor (vascular) growth and metastasis (Fig. 2).

The effect of HRGP on macrophage polarization also indirectly regulates tissue inflammation response. In chronic hepatitis, the high degree of hypoxia and expression of HIF-2α increase the concentration of HRGP, leading to up-regulation of M1 polarization and enhancing the pro-inflammatory effect of macrophages.35 This process means that HIF-2α produced under hypoxic condition of liver cells increases HRGP level, which promotes macrophage polarization toward M1, leading to further exacerbation of liver injury, making worse prognosis and more likely to progress to cirrhosis.34 Therefore, HRGP could be regarded as a therapeutic target and an indicator in liver inflammatory diseases.

From the above, as HRGP down-regulates anti-inflammatory and angiogenic M2-polarized macrophages and up-regulates pro-inflammatory and anti-tumor M1-polarized macrophages.12,34 HRGP or PIGF can be used as regulatory targets in the treatment of inflammation disease and tumor. For the role of M2-TAM, it can be speculated that TAM polarized re-induction and PIGF blocking strategy may serve as an anti-tumor approach.

Part 4 – HRGP enhances immune function

HRGP inhibits the formation of IIC (insoluble immune complex)

The secretion of autoantibodies, the formation of IIC and the resulting tissue damage are the typical pathological processes of autoimmune diseases including systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis.42,43 In these diseases, autoantibodies bind with autoantigens to form IIC, which deposit in tissues (such as kidney and joint) and cause subsequent tissue damage.44 C1q is one of the components of complement system, which can promote the formation of IIC by binding C2 domain to IgG. In vitro experiment found that HRGP could bind to C1q and IgG respectively through its N-terminal fragments, thus inhibiting their interaction and the formation of IIC.44

HRGP can also be involved in regulating the interaction between the rheumatoid factor and IgG.45 Rheumatoid factors can bind to Fc structures on IgG and play a vital role in the formation of IIC in certain autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis.46,47 HRGP can inhibit the Fc–Fc interaction and mask the rheumatoid factor recognition epitope on the IgG, thus inhibiting the formation of IIC.45 Moreover, HRGP can promote the partial dissolution of formed IIC.

These studies suggest that HRGP may function as an effective inhibitor of pathological immune complex formation and could be involved in novel therapeutic strategy in autoimmune diseases.

HRGP enhances clearance of necrotic/apoptotic cells

Under normal physiological conditions, necrotic and apoptotic cells are rapidly cleared from circulation and tissues by phagocytes to prevent exposure of intracellular antigens and immune stimulating molecules. HRGP's multidomain structure allows it to interact with the components of this process to regulate the clearance of necrotic/apoptotic cells.

HRGP has been proved to bidirectional regulate the expression of FcγR and its associated phagocytic effect in mice peritoneal macrophages. Under different treatment of HRGP, the expression level of FcγR and phagocytic function of peritoneal macrophages in mice were different. After HRGP treatment for 1–2 h, expression level of FcγR in macrophages increased, which promoted the phagocytosis of macrophages. However, after HRGP treatment for 16–48h, the expression level of FcγR decreased, resulting in declining phagocytosis of macrophages. In this process, both N-terminal and C-terminal domains of HRGP participate in the regulation of macrophage phagocytic function.48,49

Grogani et al demonstrated that HRGP can upregulate the phagocytic rate of human monocyte derived macrophages (HMDM) on apoptotic cells. HRGP was reported to act as the bridge between the FcγR Ⅰ expressed by HMDM and the DNA of apoptotic cells, which promotes phagocytosis of apoptotic cells by HMDM, and HRGP is the key physiological medium for macrophages to clear apoptotic cells. Therefore, HRGP-dependent clearance mechanisms may be activated earlier than other clearance systems such as C-reactive protein (CRP) or thrombospondin (TSP), because HRGP can enhance macrophage phagocytosis to apoptotic cells in both pathological and physiological conditions, while CRP or TSP mediated clearance mechanisms are mainly activated in the pathological state.50

Jones et al reported that although heparan sulfate was the most common cell ligand for HRGP, HRGP was able to bind to cytoplasmic ligands exposed by necrotic cells in a heparin sulfate independent manner. This interaction is mediated by the N-terminal fragment of HRGP and can enhance the phagocytosis of mononuclear cell lines to necrotic cells. Therefore, HRGP has the distinct characteristic of selective recognition of necrotic cells and may play a vital physiological role in vivo, which can promote the phagocytosis and clearance of necrotic cells by phagocytes.51

HRGP promotes anti-tumor immune response

In tumor microenvironment, the strength of the anti-tumor immune response is closely related to the tumor prognosis. The M2 polarization of tumor-associated macrophages (TAM) can inhibit the activity of DCs, cytotoxic T cells (CTL) and NK cells to inhibit the anti-tumor immune effect, which often predicts a poor prognosis of tumor. In contrast, TAM's M1 polarization can promote inflammation process, antigen presentation ability and tumor dissolution, which generally represents a better prognosis of tumor.39 Charlotte et al found that HRGP could indirectly regulate anti-tumor immune response by affecting the TAM phenotypes.12 In details, HRGP can up-regulate the infiltration degree of DCs, NK cells and CTLs, and enhance their antigen presenting ability and tumor cell lysis ability at the same time, all of which contribute to the inhibition of tumor growth.39 Although HRGP can bind to T cells and stimulate their adhesion in vitro, it is not clear whether HRGP has the ability to directly promote T cell proliferation and activation. Therefore, HRGP may indirectly regulate the immune response mainly through the change of cytokines. As mentioned above, it was reported that HRGP changed TAM polarization, inhibited the expression of cytokine IL-10, which reduced the inhibitory effect of IL-10 on DCs and macrophages mediated T cell activation.52 At the same time, up-regulating IL-6, IL-12 and IFN-β expression contribute to promote the proliferation of T cells and the activation of DCs/NKs.39,53 HRGP also enhanced the anti-tumor effect to a certain extent by improving perfusion and increasing the entry of immune cells into the tumor matrix and accelerating the clearance of dead tumor cells.16,54 Therefore, HRGP is a great endogenous immunomodulator to enhance the anti-tumor immune response.

Part 5 – HRGP's paradoxical effect on angiogenesis by promoting or inhibiting angiogenesis under different circumstances

Angiogenesis, which refers to the formation of new blood vessels from pre-existing capillaries, is one of the physiological processes necessary for tumor growth. Under normal physiological circumstances, mature vessels stay in a homeostasis, namely, an equilibrium state formed by angiogenic factors (such as VEGF) and antiangiogenic factors (such as TSP-1/TSP-2). Physiological and pathological conditions both can alter this balance and make an impact on angiogenesis.55 HRGP is not regarded as an angiogenic factor, but it can affect angiogenesis in many ways. At present, it is reported that HRGP has promoting or inhibiting effects on angiogenesis under different circumstances (Table 1).

Table 1.

Dual effect of HRGP on angiogenesis and anti-angiogenesis.

| Angiogenesis | HRGP can counteract the antiangiogenic effects of TSP-1, TSP-2 and BAI1 |

| HRGP may help plasminogen/plasmin bind to the cell surface and promote endothelial cell migration and movement, thereby promoting angiogenesis | |

| Anti-angiogenesis | HRGP can interfere with the interaction between FGFs and heparin sulfate, thus disrupting the binding between FGFs and FGF receptors, and then block the functions of FGFs. |

| HRGP inhibits heparinase-mediated FGFs release by masking the heparinase cleavage site on heparin sulfate in ECM | |

| HRGP acts as a direct anti-angiogenic agent by binding to tropomyosin on the cell surface and transmitting antiangiogenic signals. | |

| By skewing the polarization of TAM, HRGP reduces the expression of angiogenic cytokines and increases the expression of antiangiogenic cytokines, thus exerting an indirect effect on tumor blood vessels. |

Angiogenesis

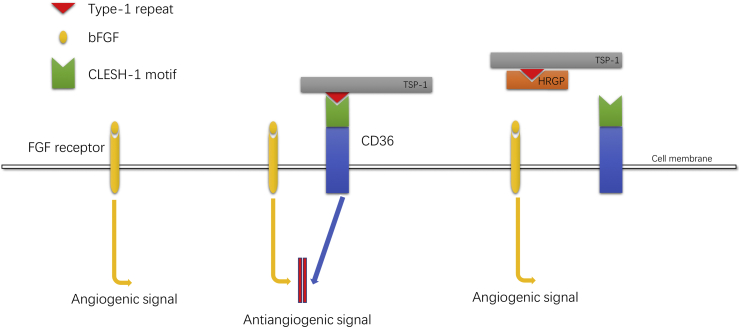

Simantov et al found that in certain tumor environments, HRGP inhibits the antiangiogenic effects of TSP-1 and TSP-2, thus promoting angiogenesis.56,57 TSP contains a large number of subtypes, TSP-1 and TSP-2 are two common subtypes of the thrombospondin family, which have significant antiangiogenic potential. These two proteins can act as inhibitors of endothelial cell proliferation, migration, and tube formation with multiple angiogenic stimuli, and inhibit angiogenic behavior in various in vivo models.58,59 Both TSP-1 and TSP-2 are identical trimeric glycoproteins with similar structures but different regulation and expression patterns. In response to vascular injury and cytokines, activated platelets secrete TSP-1, which will be deposited in the extracellular matrix by endothelial cell, smooth muscle cells, and fibroblasts.60 Differently, TSP-2 is mainly expressed by dermal fibroblasts, and under the circumstances of skin inflammation and skin carcinogenesis the protein TSP-2 is upregulated.61 The properdin-like type I repeat domains (also known as TSR domains) are the key domains for the antiangiogenic activity of both TSP-1 and TSP-2.57,62 CD-36 is an 88 kDa transmembrane glycoprotein expressed on a diversity of cells such as microvascular endothelial cell,63 which has been considered as the crucial antiangiogenic receptor for TSP-1 and TSP-2.57,64,65 The antiangiogenic activity of TSP-1 and TSP-2 requires the interaction of type I repeat domains on them and CLESH domains of the receptor CD-36 on vascular endothelial cells. HRGP also has the CLESH domains structure, which can interferes with the binding of TSP-1/TSP-2 to CD-36 (the binding of CLESH domains on HRGP and type I repeat domains on TSP-1/TSP-2 prevents the binding of TSP-1/TSP-2 to CD36) and inhibits the antiangiogenic signal transmission of TSP-1/TSP-2.56,57 From this point, HRGP's inhibition of the antiangiogenic ability of TSP-1/TSP-2 may be a promoting factor in tumor progression and metastasis (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Angiogenesis effect induced by basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) is blocked by TSP-1 through the interaction of the type-1 repeat with the CLESH-1 domain of the signal receptor CD36. HRGP also contains a CLESH-1 domain and can bind to TSP-1, preventing the interaction of TSP-1 with CD36, thereby blocking the anti-angiogenesis effect of TSP-1 (TSP-2 and BAI1 are similar mechanism diagrams).

Related follow-up experiments found that HRGP could also inhibit the antiangiogenic effect of brain angiogenesis inhibitor 1 (BAI1) by a similar mechanism.66 BAI1 is a brain-specific transmembrane protein expressed on brain glial cells with a length of 1584-amino acid. This protein is shown to have seven transmembrane fragments and a large extracellular domain. It is important that there are five TSR domains in the large extracellular domain of BAI1. Kaur et al67 have confirmed that the fragment which containing TSR domain is responsible for the antiangiogenic activity of BAI1 including inhibiting proliferation, migration, and tube formation of microvascular endothelial cell (MVEC). Similarly, TSR domain, also called vasculostatin or Vstat120, mediates BAI1 antiangiogenic effects by interacting with CD36 CLESH domains as we mentioned above.66 The CLESH domains of HRGP can specifically bind to Vstat120 (TSR domain) which eliminate the antiangiogenic effect of BAI1 through interfering with the interaction between Vstat120 and CD36 and counteracting the inhibition effect on endothelial cell migration and tube formation. In addition, in certain tumor models, HRGP accelerates glioblastoma tumor growth and contributes to tumor vascularity.66 Thus, HRGP may play a potential role in promoting tumor progression in some neoplasms. It is reasonable to speculate that the special structure of HRGP can make it interact with other molecules containing TSR domains to produce corresponding effects (Fig. 3).

Furthermore, HRGP has the ability to bind to plasminogen and cell surface receptors, which is strengthened by increasing Zn2+ concentration and decreasing pH. The plasminogen system combined on the cell surface contributes to promoting cell migration, including angiogenesis. Therefore, Allison et al found that HRGP may trap plasminogen/plasmin to the cell surface and potentially promote endothelial cell migration and movement during angiogenesis process, although this phenomenon may also assist many other cell types with invasion.13,23

Anti-angiogenesis

HRGP can prevent the heparan sulfate from acting as a coreceptor for diverse fibroblast growth factors (FGFs) by interacting with heparan sulfate on the endothelial cell surface. Under the interaction with heparin sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs) on the cell surface, FGFs then can bind to and activate FGF receptors, thus exerting FGFs biological activity. HRGP has the ability to compete with FGFs for cell surface heparin sulfate, thereby weakening FGFs activity to activate FGF receptors. Obviously, this inhibition is not only limited to angiogenesis, but also block FGF-dependent proliferation processes.13,24

HRGP could mask ECM (extracellular matrix) heparan sulfate's heparanase cleavage sites to block heparanase mediated release of angiogenesis growth factors (such as FGFs) from the ECM. Also, heparan sulfate is an important component of the ECM and the vasculature basal layer which functions as a barrier to the extravasation. Cleavage of heparan sulphate by heparanase may assist in the disassembly of the ECM and basal layer, and thereby facilitate cell migration. Similarly, this inhibition may not be limited to angiogenesis.13,68

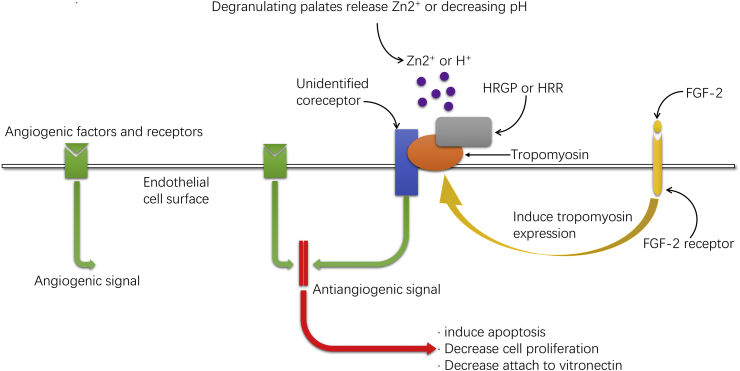

HRGP could also inhibit angiogenesis through its direct effect on vascular endothelial cells.22,69, 70, 71 Specifically, GHHPH consensus region within histidine-rich region (HRR) in HRGP mediates the antiangiogenic effect of HRGP.71 Additional studies demonstrated that tropomyosin is the key HRR-binding ligand on endothelial cells, and under conditions of increased Zn2+ and/or decreased pH the affinity is enhanced.22 Because tropomyosin has no transmembrane domain, other proteins on the endothelial cell membrane may assist tropomyosin in the transmission of antiangiogenic signals. Through this interaction, HRGP can induce activated endothelial cells apoptosis and thus downregulate cell proliferation to function as an antiangiogenic agent.70 Olsson et al also considered that HRGP may decrease the adhesion between endothelial cells and vitronectin as well as endothelial cell migration.69 The same research group69 found that treating fibrosarcoma mice model with HRGP resulted in downregulation of tumor angiogenesis and a shrink in tumor volume. Interestingly, peptides isolated from the HRR also demonstrate the ability to inhibit angiogenesis and tumor growth.71 Later Olsson et al found HRGP could induce tyrosine phosphorylation of focal adhesion kinase and its downstream substrate paxillin as well as destruction of actin stress fibers in endothelial cells and inhibit endothelial cells assemble to form vessel structures.72 Therefore, HRR, the special protein fragment from HRGP, could be applied as a novel anti-tumor and anti-angiogenesis substance (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

HRGP acts as a direct anti-angiogenic agent by binding to tropomyosin on the cell surface and transmitting antiangiogenic signals. Fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF-2) binds to its cell surface receptor and induces more expression of tropomyosin on the endothelial cell surface. The HRR domain of HRGP then binds to tropomyosin and transmits an antiangiogenic signal to the endothelial cells. Because tropomyosin has no transmembrane domain, other proteins on the endothelial cell membrane may assist tropomyosin in the transmission of antiangiogenic signals. Low pH or the presence of Zn2+ will enhance the interaction between HRR and tropomyosin. At physiological pH, this process is mainly dependent on the presence of Zn2+, with local increased free Zn2+ concentrations (about 10–50 μmol/L) which is provided by the degranulating platelets. Binding can also occur in the absence of Zn2+ in slightly acidic environment (pH ≈ 6.5). The antiangiogenic effect will induce increased apoptosis, decreased cell proliferation and migration, as well as decreased adhesion between endothelial cells and vitronectin. This figure was based on results discussed in Donate et al,71 Guan et al22 and Olsson et al.69

HRGP can normalize tumor blood vessels and promote tumor blood vessel maturation, which means HRGP has the effect of anti-abnormal angiogenesis.12 Typically, abnormal, hypoperfusion neovascularization is a characteristic of malignancy. These blood vessels impair blood perfusion, block drug delivery, and accelerate cancer cell metastasis.73,74 HRGP can be deposited into the tumor matrix through plasma and platelets,66 which can promote the normalization of tumor blood vessels, reduce the number of abnormal blood vessels, facilitate the maturation of tumor blood vessels, increase the stability and tightness of endothelial cells, promote the blood perfusion of tumor, thus improve the ischemia and hypoxia condition of tumor, reduce the edema and ischemic necrosis of tumor, and enhance the efficacy of chemotherapy drugs.12 At the same time, tighter and more stable tumor vascular endothelial cells help reduce tumor cell metastasis.74 In terms of mechanism, although angiogenesis is not regulated by PIGF in specific tumor models,75 HRGP down-regulation of PIGF expression is the main downstream pathway for HRGP to participate in tumor vascular regulation. Specifically, up-regulation of M2 derived-cytokines promoting angiogenesis (such as IL-10, CCL22, IL-1β, TNF-α) and down-regulation of M1 derived-cytokines inhibiting angiogenesis (such as IFN-β, CXCL10, IL-12) is one of the causes of abnormal blood vessels in tumors. HRGP can reduce the expression of PIGF to down-regulate the M2 polarization of TAM and up-regulate the M1 polarization, thus having an indirect effect on tumor blood vessels. Theoretically, both M1 and M2 phenotypes are involved in the regulation of blood vessels, but it was found that the regulation of blood vessels in tumors is mainly mediated by M2 phenotype, while M1 phenotype is not significantly involved in this process. Therefore, the role of HRGP in normalizing blood vessels and improving perfusion and oxygenation is mainly related to the down-regulation of M2 phenotype TAM. In addition to the indirect effect of HRGP on TAM polarization to regulate tumor blood vessels, HRGP can also have a direct effect on tumor vascular endothelial cells. However, studies have indicated that the indirect effect of HRGP may play a dominant role in tumor microenvironment.12

Part 6 – HRGP's dual effect on hemostasis by promoting or inhibiting hemostasis under different circumstances

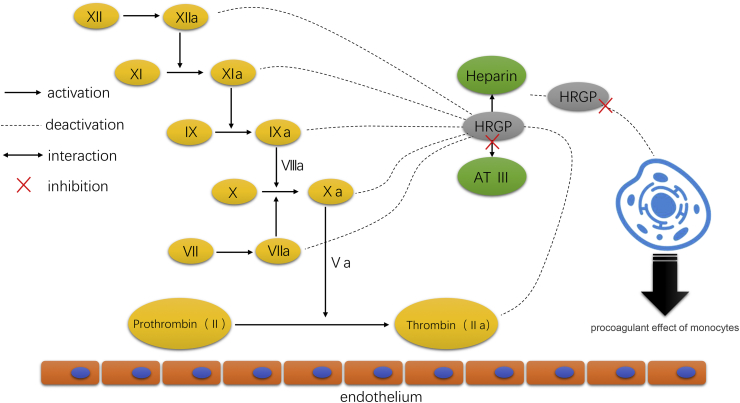

HRGP can interact with many components in the coagulation cascade to affect the coagulation system. Heparin is an important anticoagulant component in the coagulation system. HRGP can bind to heparin so that the heparin released by mast cells at the site of inflammation and thrombosis cannot inhibit the procoagulant effect of monocytes.76,77 HRGP can also interfere with the interaction between heparin and antithrombin Ⅲ, thus decreasing antithrombin Ⅲ anticoagulant effect.78, 79, 80 Therefore, HRGP may play a potential role in regulating the anticoagulant activity of heparin in vivo (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

In the anticoagulant system in vivo, heparin binds to antithrombin Ⅲ (AT-Ⅲ), forming heparin AT-Ⅲ complexes. Heparin enhances the anticoagulant activity of AT-Ⅲ, thus accelerating the inactivation of coagulation factors and inhibiting the coagulation cascade system. Also, HRGP can bind to heparin so that the heparin released by mast cells at the site of inflammation and thrombosis cannot inhibit the procoagulant effect of monocytes.

Ensslen et al successfully constructed HRGP-deficient mice model and in their model the exon 1 of the initial point of HRGP gene translation was absent, making mice blood free of HRGP. In the hemostasis test of this mice model, HRGP-deficient mice had higher antithrombin activity, shorter prothrombin time and less tail truncation bleeding time. The fibrinolytic system activity was also more powerful. We can speculate that HRGP has both anticoagulant and antifibrinolytic effects which may regulate platelet function in vivo.81

Plasminogen is a component of the fibrinolytic system that can be activated and dissolve fibrin clots. HRGP has been proved that it can bind to lysine binding sites on plasminogen, thereby interfering with interactions between plasminogen and other components of the fibrinolytic system (e.g. fibrin), making HRGP antifibrinolytic.14 This effect of HRGP may extend the duration of fibrin. Interestingly, however, other studies found that HRGP can promote the activation of plasminogen and thus enhance fibrinolysis.82,83 Although the soluble HRGP does not significantly influence plasminogen activation, fixed HRGP can bind to plasminogen and increase the affinity of tPA to plasminogen, thus amplifying the activation effect of tPA on plasminogen (convert to plasmin) by about 30 times, promoting the fibrinolytic effect on fibrin clots.83

Part 7 – Other effect of HRGP

HRGP activity is mainly regulated by Zn2+ concentration and pH

The physiological effects of HRGP are largely dependent on the concentration of Zn2+ and pH (H+).13 Generally speaking, increased Zn2+ concentration or decreased pH can promote the binding of HRGP to various ligands or cell surface receptors.13 Morgan et al described that when the pH of the microenvironment decreased, such as ischemia or hypoxia, the histidine side chain of HRGP would undergo protonation, enabling HRGP to bind tightly to negative charge GAG on the cell surface.84 Subsequent studies also demonstrated that the microenvironment with low pH and high Zn2+ concentration was favorable for HRGP binding and activation of plasminogen.23,83

HRGP has antibacterial activity

HRGP has antibacterial activity against both gram-positive bacteria (such as Enterococcus faecalis and Staphylococcus aureus) and gram-negative bacteria (such as Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa). In the study of E. faecalis, HRGP would induce E. faecalis cleavage in the presence of Zn2+ and low pH environment. Heparin, as a ligand of HRGP, can block the combination of HRGP and bacteria, thus neutralize the antibacterial activity of HRGP. Further studies indicated that the HRR structure and heparin binding domain of HRGP mediate its antibacterial effect, and the presence of low pH and high Zn2+ can enhance its antibacterial activity.85

HRGP inhibits HIV-1 infection and its antiviral activity

HRGP was reported to inhibit HIV-1 infection in a pH-dependent manner.86 As known to all, immune system is the main target of HIV. Ezequiel et al found that HRGP almost completely purged the infection of Ghost cells, Jurkat cells, CD4+ T cells, and macrophages by HIV-1 at a low pH (6.5–5.5) but not at a neutral pH. HRGP may interact with the heparan sulfate on the target cells, blocking the early post-binding step of HIV-1 infection. More significantly, by acting on the HIV particle itself, HRGP induced a toxic effect, which weakens viral infectivity. Vaginal sex is a high-risk transmission route of HIV-1. Because health women cervicovaginal secretions maintain low pH values, even after semen deposition, this finding implies that HRGP might participate in a innate antiviral mechanism in the genital tract mucosa. Interestingly, in conditions like low pH values, HRGP will also markedly inhibit the infection of other viruses, such as herpes simplex virus 2 and respiratory syncytial virus, suggesting that an acid environment may enable HRGP to exhibit broad antiviral activity.86

HRGP acts as a clinical biomarker

In clinical studies, HRGP may have the potential to be a biomarker for sepsis, embryo quality, and breast disease recognition.87, 88, 89 Interestingly, HRGP is one of the few plasma proteins that will markedly reduce (about 50%) during the last trimester of pregnancy, and this may reflect the state of the fetus.90 Although HRGP is not currently included in the laboratory tests as clinical biomarker, further research will find its predictive value for more diseases and conditions.

Summary

HRGP is a plasma protein with multidomain structure, whose interactions with many ligands and cells lay the foundation for its physiological function in vivo. In a way, it is a “paradoxical” molecule. HRGP can induce macrophage polarization toward M1 phenotype, with HRGP-specific M1 polarization in pattern in certain circumstances. When acting with different ligands, HRGP can promote or inhibit angiogenesis correspondingly. Also, in the coagulation system, HRGP can promote or inhibit coagulation and fibrinolysis under different conditions. More than that, HRGP has many other known or unknown functions. This is an interesting and mysterious molecule, and a lot of its underlying functions are waiting to be discovered.

Research involving human and/or animal rights

This Mini Review does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects.

Conflicts of interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

This project is supported by the (No. 20204Y0012) Project of Shanghai Municipal Health Commission; National Key R&D Program of China (No. 2017YFC0908100); W410170015, Cohort Study of HCC and Liver Diseases, Double First-Class Fundation, Shanghai Jiao Tong University; 2017ZZ01018, Overall Leverage Clinical Medicine Center, NHFPC Fundation.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chongqing Medical University.

Contributor Information

Kang He, Email: hekang929@163.com.

Qiang Xia, Email: xiaqiang@shsmu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Haupt H., Heimburger N. [Human serum proteins with high affinity for carboxymethylcellulose. I. Isolation of lysozyme, C1q and 2 hitherto unknown -globulins] Hoppe-Seyler's Z Physiol Chem. 1972;353(7):1125–1132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heimburger N., Haupt H., Kranz T., Baudner S. [Human serum proteins with high affinity to carboxymethylcellulose. II. Physico-chemical and immunological characterization of a histidine-rich 3,8S- 2 -glycoprotein (CM-protein I)] Hoppe-Seyler's Z Physiol Chem. 1972;353(7):1133–1140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nair P.S., Robinson W.E. Purification and characterization of a histidine-rich glycoprotein that binds cadmium from the blood plasma of the bivalve Mytilus edulis. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1999;366(1):8–14. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1999.1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koide T., Foster D., Yoshitake S., Davie E.W. Amino acid sequence of human histidine-rich glycoprotein derived from the nucleotide sequence of its cDNA. Biochemistry. 1986;25(8):2220–2225. doi: 10.1021/bi00356a055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drasin T., Sahud M. Blood-type and age affect human plasma levels of histidine-rich glycoprotein in a large population. Thromb Res. 1996;84(3):179–188. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(96)00174-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Corrigan J.J., Jr., Jeter M.A., Bruck D., Feinberg W.M. Histidine-rich glycoprotein levels in children: the effect of age. Thromb Res. 1990;59(3):681–686. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(90)90428-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sia D.Y., Rylatt D.B., Parish C.R. Anti-self receptors. V. Properties of a mouse serum factor that blocks autorosetting receptors on lymphocytes. Immunology. 1982;45(2):207–216. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leung L.L., Harpel P.C., Nachman R.L., Rabellino E.M. Histidine-rich glycoprotein is present in human platelets and is released following thrombin stimulation. Blood. 1983;62(5):1016–1021. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morgan W.T. Human serum histidine-rich glycoprotein. I. Interactions with heme, metal ions and organic ligands. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1978;535(2):319–333. doi: 10.1016/0005-2795(78)90098-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saito H., Goodnough L.T., Boyle J.M., Heimburger N. Reduced histidine-rich glycoprotein levels in plasma of patients with advanced liver cirrhosis. Possible implications for enhanced fibrinolysis. Am J Med. 1982;73(2):179–182. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(82)90175-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leung L. Histidine-rich glycoprotein: an abundant plasma protein in search of a function. J Lab Clin Med. 1993;121(5):630–631. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rolny C., Mazzone M., Tugues S., et al. HRG inhibits tumor growth and metastasis by inducing macrophage polarization and vessel normalization through downregulation of PlGF. Cancer Cell. 2011;19(1):31–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones A.L., Hulett M.D., Parish C.R. Histidine-rich glycoprotein: a novel adaptor protein in plasma that modulates the immune, vascular and coagulation systems. Immunol Cell Biol. 2005;83(2):106–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1711.2005.01320.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lijnen H.R., Hoylaerts M., Collen D. Isolation and characterization of a human plasma protein with affinity for the lysine binding sites in plasminogen. Role in the regulation of fibrinolysis and identification as histidine-rich glycoprotein. J Biol Chem. 1980;255(21):10214–10222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koide T., Odani S., Ono T. Human histidine-rich glycoprotein: simultaneous purification with antithrombin III and characterization of its gross structure. J Biochem. 1985;98(5):1191–1200. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a135385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blank M., Shoenfeld Y. Histidine-rich glycoprotein modulation of immune/autoimmune, vascular, and coagulation systems. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2008;34(3):307–312. doi: 10.1007/s12016-007-8058-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shatsky M., Saigo K., Burdach S., Leung L.L., Levitt L.J. Histidine-rich glycoprotein blocks T cell rosette formation and modulates both T cell activation and immunoregulation. J Biol Chem. 1989;264(14):8254–8259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saigo K., Shatsky M., Levitt L.J., Leung L.K. Interaction of histidine-rich glycoprotein with human T lymphocytes. J Biol Chem. 1989;264(14):8249–8253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parish C.R., Rylatt D.B., Snowden J.M. Demonstration of lymphocyte surface lectins that recognize sulphated polysaccharides. J Cell Sci. 1984;67:145–158. doi: 10.1242/jcs.67.1.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lerch P.G., Nydegger U.E., Kuyas C., Haeberli A. Histidine-rich glycoprotein binding to activated human platelets. Br J Haematol. 1988;70(2):219–224. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1988.tb02467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Horne M.K., 3rd, Merryman P.K., Cullinane A.M. Histidine-proline-rich glycoprotein binding to platelets mediated by transition metals. Thromb Haemost. 2001;85(5):890–895. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guan X., Juarez J.C., Qi X., et al. Histidine-proline rich glycoprotein (HPRG) binds and transduces anti-angiogenic signals through cell surface tropomyosin on endothelial cells. Thromb Haemost. 2004;92(2):403–412. doi: 10.1160/TH04-02-0073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jones A.L., Hulett M.D., Altin J.G., Hogg P., Parish C.R. Plasminogen is tethered with high affinity to the cell surface by the plasma protein, histidine-rich glycoprotein. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(37):38267–38276. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406027200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brown K.J., Parish C.R. Histidine-rich glycoprotein and platelet factor 4 mask heparan sulfate proteoglycans recognized by acidic and basic fibroblast growth factor. Biochemistry. 1994;33(46):13918–13927. doi: 10.1021/bi00250a047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Olsen H.M., Parish C.R., Altin J.G. Histidine-rich glycoprotein binding to T-cell lines and its effect on T-cell substratum adhesion is strongly potentiated by zinc. Immunology. 1996;88(2):198–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.1996.tb00005.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gorgani N.N., Parish C.R., Altin J.G. Differential binding of histidine-rich glycoprotein (HRG) to human IgG subclasses and IgG molecules containing kappa and lambda light chains. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(42):29633–29640. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.42.29633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Araujo J.A., Zhang M., Yin F. Heme oxygenase-1, oxidation, inflammation, and atherosclerosis. Front Pharmacol. 2012;3:119. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2012.00119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Naito Y., Takagi T., Higashimura Y. Heme oxygenase-1 and anti-inflammatory M2 macrophages. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2014;564:83–88. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2014.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weis N., Weigert A., von Knethen A., Brune B. Heme oxygenase-1 contributes to an alternative macrophage activation profile induced by apoptotic cell supernatants. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20(5):1280–1288. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-10-1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Autiero M., Waltenberger J., Communi D., et al. Role of PlGF in the intra- and intermolecular cross talk between the VEGF receptors Flt1 and Flk1. Nat Med. 2003;9(7):936–943. doi: 10.1038/nm884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carmeliet P., Moons L., Luttun A., et al. Synergism between vascular endothelial growth factor and placental growth factor contributes to angiogenesis and plasma extravasation in pathological conditions. Nat Med. 2001;7(5):575–583. doi: 10.1038/87904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fischer C., Mazzone M., Jonckx B., Carmeliet P. FLT1 and its ligands VEGFB and PlGF: drug targets for anti-angiogenic therapy? Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8(12):942–956. doi: 10.1038/nrc2524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lewis C.E., De Palma M., Naldini L. Tie2-expressing monocytes and tumor angiogenesis: regulation by hypoxia and angiopoietin-2. Cancer Res. 2007;67(18):8429–8432. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bartneck M., Fech V., Ehling J., et al. Histidine-rich glycoprotein promotes macrophage activation and inflammation in chronic liver disease. Hepatology. 2016;63(4):1310–1324. doi: 10.1002/hep.28418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morello E., Sutti S., Foglia B., et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor 2alpha drives nonalcoholic fatty liver progression by triggering hepatocyte release of histidine-rich glycoprotein. Hepatology. 2018;67(6):2196–2214. doi: 10.1002/hep.29754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Movahedi K., Laoui D., Gysemans C., et al. Different tumor microenvironments contain functionally distinct subsets of macrophages derived from Ly6C(high) monocytes. Cancer Res. 2010;70(14):5728–5739. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-4672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pucci F., Venneri M.A., Biziato D., et al. A distinguishing gene signature shared by tumor-infiltrating Tie2-expressing monocytes, blood “resident” monocytes, and embryonic macrophages suggests common functions and developmental relationships. Blood. 2009;114(4):901–914. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-01-200931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mantovani A., Sozzani S., Locati M., Allavena P., Sica A. Macrophage polarization: tumor-associated macrophages as a paradigm for polarized M2 mononuclear phagocytes. Trends Immunol. 2002;23(11):549–555. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(02)02302-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mantovani A., Sica A. Macrophages, innate immunity and cancer: balance, tolerance, and diversity. Curr Opin Immunol. 2010;22(2):231–237. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2010.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hagemann T., Lawrence T., McNeish I., et al. “Re-educating” tumor-associated macrophages by targeting NF-kappaB. J Exp Med. 2008;205(6):1261–1268. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Arteta B., Lasuen N., Lopategi A., Sveinbjornsson B., Smedsrod B., Vidal-Vanaclocha F. Colon carcinoma cell interaction with liver sinusoidal endothelium inhibits organ-specific antitumor immunity through interleukin-1-induced mannose receptor in mice. Hepatology. 2010;51(6):2172–2182. doi: 10.1002/hep.23590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cohen I.R. Biomarkers, self-antigens and the immunological homunculus. J Autoimmun. 2007;29(4):246–249. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2007.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wandstrat A.E., Carr-Johnson F., Branch V., et al. Autoantibody profiling to identify individuals at risk for systemic lupus erythematosus. J Autoimmun. 2006;27(3):153–160. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gorgani N.N., Parish C.R., Easterbrook Smith S.B., Altin J.G. Histidine-rich glycoprotein binds to human IgG and C1q and inhibits the formation of insoluble immune complexes. Biochemistry. 1997;36(22):6653–6662. doi: 10.1021/bi962573n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gorgani N.N., Altin J.G., Parish C.R. Histidine-rich glycoprotein prevents the formation of insoluble immune complexes by rheumatoid factor. Immunology. 1999;98(3):456–463. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1999.00885.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stewart J.J., Agosto H., Litwin S., et al. A solution to the rheumatoid factor paradox: pathologic rheumatoid factors can be tolerized by competition with natural rheumatoid factors. J Immunol. 1997;159(4):1728–1738. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Johnson P.M., Faulk W.P. Rheumatoid factor: its nature, specificity, and production in rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1976;6(3):414–430. doi: 10.1016/0090-1229(76)90094-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chang N.S., Leu R.W., Anderson J.K., Mole J.E. Role of N-terminal domain of histidine-rich glycoprotein in modulation of macrophage Fc gamma receptor-mediated phagocytosis. Immunology. 1994;81(2):296–302. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chang N.S., Leu R.W., Rummage J.A., Anderson J.K., Mole J.E. Regulation of macrophage Fc receptor expression and phagocytosis by histidine-rich glycoprotein. Immunology. 1992;77(4):532–538. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gorgani N.N., Smith B.A., Kono D.H., Theofilopoulos A.N. Histidine-rich glycoprotein binds to DNA and Fc gamma RI and potentiates the ingestion of apoptotic cells by macrophages. J Immunol. 2002;169(9):4745–4751. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.9.4745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jones A.L., Poon I.K., Hulett M.D., Parish C.R. Histidine-rich glycoprotein specifically binds to necrotic cells via its amino-terminal domain and facilitates necrotic cell phagocytosis. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(42):35733–35741. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504384200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Koppelman B., Neefjes J.J., de Vries J.E., de Waal Malefyt R. Interleukin-10 down-regulates MHC class II alphabeta peptide complexes at the plasma membrane of monocytes by affecting arrival and recycling. Immunity. 1997;7(6):861–871. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80404-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.DeNardo D.G., Andreu P., Coussens L.M. Interactions between lymphocytes and myeloid cells regulate pro- versus anti-tumor immunity. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2010;29(2):309–316. doi: 10.1007/s10555-010-9223-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hamzah J., Jugold M., Kiessling F., et al. Vascular normalization in Rgs5-deficient tumours promotes immune destruction. Nature. 2008;453(7193):410–414. doi: 10.1038/nature06868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dvorak H.F. Angiogenesis: update 2005. J Thromb Haemost. 2005;3(8):1835–1842. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01361.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Simantov R., Febbraio M., Crombie R., Asch A.S., Nachman R.L., Silverstein R.L. Histidine-rich glycoprotein inhibits the antiangiogenic effect of thrombospondin-1. J Clin Investig. 2001;107(1):45–52. doi: 10.1172/JCI9061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Simantov R., Febbraio M., Silverstein R.L. The antiangiogenic effect of thrombospondin-2 is mediated by CD36 and modulated by histidine-rich glycoprotein. Matrix Biol. 2005;24(1):27–34. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2004.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bornstein P. Thrombospondins as matricellular modulators of cell function. J Clin Investig. 2001;107(8):929–934. doi: 10.1172/JCI12749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Adams J.C., Lawler J. The thrombospondins. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect Biol. 2011;3(10) doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a009712. a009712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Frazier W.A. Thrombospondin: a modular adhesive glycoprotein of platelets and nucleated cells. J Cell Biol. 1987;105(2):625–632. doi: 10.1083/jcb.105.2.625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Streit M., Riccardi L., Velasco P., et al. Thrombospondin-2: a potent endogenous inhibitor of tumor growth and angiogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96(26):14888–14893. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.26.14888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Iruela-Arispe M.L., Lombardo M., Krutzsch H.C., Lawler J., Roberts D.D. Inhibition of angiogenesis by thrombospondin-1 is mediated by 2 independent regions within the type 1 repeats. Circulation. 1999;100(13):1423–1431. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.13.1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Febbraio M., Hajjar D.P., Silverstein R.L. CD36: a class B scavenger receptor involved in angiogenesis, atherosclerosis, inflammation, and lipid metabolism. J Clin Investig. 2001;108(6):785–791. doi: 10.1172/JCI14006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dawson D.W., Pearce S.F., Zhong R., Silverstein R.L., Frazier W.A., Bouck N.P. CD36 mediates the in vitro inhibitory effects of thrombospondin-1 on endothelial cells. J Cell Biol. 1997;138(3):707–717. doi: 10.1083/jcb.138.3.707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jimenez B., Volpert O.V., Crawford S.E., Febbraio M., Silverstein R.L., Bouck N. Signals leading to apoptosis-dependent inhibition of neovascularization by thrombospondin-1. Nat Med. 2000;6(1):41–48. doi: 10.1038/71517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Klenotic P.A., Huang P., Palomo J., et al. Histidine-rich glycoprotein modulates the anti-angiogenic effects of vasculostatin. Am J Pathol. 2010;176(4):2039–2050. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kaur B., Brat D.J., Devi N.S., Van Meir E.G. Vasculostatin, a proteolytic fragment of brain angiogenesis inhibitor 1, is an antiangiogenic and antitumorigenic factor. Oncogene. 2005;24(22):3632–3642. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Freeman C., Parish C.R. A rapid quantitative assay for the detection of mammalian heparanase activity. Biochem J. 1997;325(Pt 1):229–237. doi: 10.1042/bj3250229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Olsson A.K., Larsson H., Dixelius J., et al. A fragment of histidine-rich glycoprotein is a potent inhibitor of tumor vascularization. Cancer Res. 2004;64(2):599–605. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-1941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Juarez J.C., Guan X., Shipulina N.V., et al. Histidine-proline-rich glycoprotein has potent antiangiogenic activity mediated through the histidine-proline-rich domain. Cancer Res. 2002;62(18):5344–5350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Donate F., Juarez J.C., Guan X., et al. Peptides derived from the histidine-proline domain of the histidine-proline-rich glycoprotein bind to tropomyosin and have antiangiogenic and antitumor activities. Cancer Res. 2004;64(16):5812–5817. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lee C., Dixelius J., Thulin A., Kawamura H., Claesson-Welsh L., Olsson A.K. Signal transduction in endothelial cells by the angiogenesis inhibitor histidine-rich glycoprotein targets focal adhesions. Exp Cell Res. 2006;312(13):2547–2556. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2006.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Jain R.K. Normalization of tumor vasculature: an emerging concept in antiangiogenic therapy. Science. 2005;307(5706):58–62. doi: 10.1126/science.1104819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mazzone M., Dettori D., de Oliveira R.L., et al. Heterozygous deficiency of PHD2 restores tumor oxygenation and inhibits metastasis via endothelial normalization. Cell. 2009;136(5):839–851. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Van de Veire S., Stalmans I., Heindryckx F., et al. Further pharmacological and genetic evidence for the efficacy of PlGF inhibition in cancer and eye disease. Cell. 2010;141(1):178–190. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Leung L., Saigo K., Grant D. Heparin binds to human monocytes and modulates their procoagulant activities and secretory phenotypes. Effects of histidine-rich glycoprotein. Blood. 1989;73(1):177–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lijnen H.R., van Hoef B., Collen D. Interaction of heparin with histidine-rich glycoprotein and with antithrombin III. Thromb Haemost. 1983;50(2):560–562. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Leung L.L., Nachman R.L., Harpel P.C. Complex formation of platelet thrombospondin with histidine-rich glycoprotein. J Clin Investig. 1984;73(1):5–12. doi: 10.1172/JCI111206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lijnen H.R., Collen D. Turnover of histidine-rich glycoprotein during heparin administration in man. Thromb Res. 1983;30(6):671–676. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(83)90276-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lijnen H.R., Van Hoef B., Collen D. Histidine-rich glycoprotein modulates the anticoagulant activity of heparin in human plasma. Thromb Haemost. 1984;51(2):266–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Tsuchida-Straeten N., Ensslen S., Schafer C., et al. Enhanced blood coagulation and fibrinolysis in mice lacking histidine-rich glycoprotein (HRG) J Thromb Haemost. 2005;3(5):865–872. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01238.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Silverstein R.L., Nachman R.L., Leung L.L., Harpel P.C. Activation of immobilized plasminogen by tissue activator. Multimolecular complex formation. J Biol Chem. 1985;260(18):10346–10352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Borza D.B., Morgan W.T. Acceleration of plasminogen activation by tissue plasminogen activator on surface-bound histidine-proline-rich glycoprotein. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(9):5718–5726. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.9.5718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Morgan W.T. Interactions of the histidine-rich glycoprotein of serum with metals. Biochemistry. 1981;20(5):1054–1061. doi: 10.1021/bi00508a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Rydengard V., Olsson A.K., Morgelin M., Schmidtchen A. Histidine-rich glycoprotein exerts antibacterial activity. FEBS J. 2007;274(2):377–389. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2006.05586.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Dantas E., Erra Díaz F., Pereyra Gerber P., et al. Histidine-rich glycoprotein inhibits HIV-1 infection in a pH-dependent manner. J Virol. 2019;93(4) doi: 10.1128/JVI.01749-18. e01749–e18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Autenshlyus A.I., Golovanova A.V., Studenikina A.A., et al. Personalized approach to assessing mRNA expression of histidine-rich glycoprotein and immunohistochemical markers in diseases of the breast. Dokl Biochem Biophys. 2019;484(1):59–62. doi: 10.1134/S1607672919010162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kaihola H., Yaldir F.G., Bohlin T., Samir R., Hreinsson J., Akerud H. Levels of caspase-3 and histidine-rich glycoprotein in the embryo secretome as biomarkers of good-quality day-2 embryos and high-quality blastocysts. PLoS One. 2019;14(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0226419. e0226419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Nishibori M., Wake H., Morimatsu H. Histidine-rich glycoprotein as an excellent biomarker for sepsis and beyond. Crit Care. 2018;22(1):209. doi: 10.1186/s13054-018-2127-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Halbmayer W.M., Hopmeier P., Feichtinger C., Rubi K., Fischer M. Histidine-rich glycoprotein (HRG) in uncomplicated pregnancy and mild and moderate preeclampsia. Thromb Haemostasis. 1992;67(5):585–586. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]