Abstract

Regulatory T (Treg) cells constitute a dynamic population that is critical in autoimmunity. Treg cell therapies for autoimmune diseases are mainly focused on enhancing their suppressive activities. However, recent studies demonstrated that certain inflammatory conditions induce Treg cell instability with diminished FoxP3 expression and convert them into pathogenic effector cells. Therefore, the identification of novel targets crucial to both Treg cell function and plasticity is of vital importance to the development of therapeutic approaches in autoimmunity. In this study, we found that conditional Pp6 knockout (cKO) in Treg cells led to spontaneous autoinflammation, immune cell activation, and diminished levels of FoxP3 in CD4+ T cells in mice. Loss of Pp6 in Treg cells exacerbated two classical mouse models of Treg-related autoinflammation. Mechanistically, Pp6 deficiency increased CpG motif methylation of the FoxP3 locus by dephosphorylating Dnmt1 and enhancing Akt phosphorylation at Ser473/Thr308, leading to impaired FoxP3 expression in Treg cells. In summary, our study proposes Pp6 as a critical positive regulator of FoxP3 that acts by decreasing DNA methylation of the FoxP3 gene enhancer and inhibiting Akt signaling, thus maintaining Treg cell stability and preventing autoimmune diseases.

Keywords: Akt, DNA methyltransferase 1 (Dnmt1), FoxP3, Protein phosphatase 6 (Pp6), Regulatory T (Treg) cells, Stability

Abbreviations: FoxP3, Forkhead box protein P3; WT, wild type; EAE, experimental allergic encephalomyelitis; TCR, T cell receptor; CTV, CellTrace Violet; Rag1, recombination-activating protein 1; TSDR, Treg-specific demethylated region

Introduction

Recent studies have reported that FoxP3+ regulatory T (Treg) cells are not a terminally differentiated cell population with a fixed phenotype; they display some degree of plasticity and/or instability under certain inflammatory conditions.1 Although the functional stability of Treg cells is a controversial issue, some groups have observed that under specific inflammatory conditions, natural and induced regulatory T (iTreg) cells lose FoxP3 expression and acquire a pathogenic phenotype with the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines, becoming so-called “exFoxP3” Treg cells.2,3 FoxP3 is a key marker for Treg cells, and its stable expression is required for Treg cell maintenance and immunosuppression.4 Loss of FoxP3 in Treg cells partially causes autoimmune diseases in mice and humans.5,6 Genetic mutation of FoxP3 leads to the scurfy phenotype in mice, which includes fatal autoimmunity.7 The mutation of human FoxP3 causes immune dysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, and X-linked syndrome (IPEX).8

Protein phosphatase 6 (Pp6) belongs to the serine/threonine protein phosphatase family.9 Pp6-specific deletion in Treg cells led to marked impairment of Treg cell induction and increased Ang II-induced blood pressure elevation in mice.10 However, the exact function of Pp6 in Treg cells remains elusive. In this study, we found that conditional Pp6 knockout (cKO) in Treg cells led to diminished levels of FoxP3, which inspired us to explore the underlying mechanism.

Recent studies revealed that FoxP3 stability depends on the demethylation of the CpG motif in the FoxP3 locus, especially in the Treg cell-specific demethylated region (TSDR).11,12 Three kinds of DNA methyltransferase (Dnmt) enzymes are responsible for DNA methylation: Dnmt1, Dnmt3a, and Dnmt3b.13 In mice, Dnmt1 deficiency in Treg cells weakens their suppressive function, while Dnmt3a deficiency does not, suggesting that Dnmt1 is critical to Treg cells.14 Upon TCR signaling, Dnmt1 is upregulated to mediate FoxP3 expression by enhancing CpG methylation.15 Treg cells in patients with abdominal arterial aneurysm, a disease that shares many features with autoimmune diseases, have a significantly higher DNA methylation rate of Dnmt1 levels than the control group.16 Elevated methylation levels of Treg cell-conserved noncoding sequences in the FoxP3 locus abrogate FoxP3 expression, leading to severe autoimmune disease.17 However, the dynamic modulation of CpG motif methylation and activity control of Dnmt in Treg cells remain elusive. Here, we report that Pp6 could bind and dephosphorylate Dnmt1, hence decreasing CpG motif methylation at the FoxP3 locus.

FoxP3 is negatively controlled by the PI3K/Akt pathway, which is a critical inhibitory signal restraining FoxP3 expression in Treg cells.37 Akt hyperactivation contributes to Treg cell reduction and plasticity.18 Interestingly, several phosphatases restrict the PI3K/Akt cascade by dephosphorylating key proteins. Protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) mainly reduces mTOC1 activity by dephosphorylating S6 protein, with a negligible effect on phosphorylation of Akt at Ser473 and Thr308 in mouse CD4+ T cells.19,20 Conditional knockdown of Pp6 in T cells activates TCR terminal signals, such as MAPKs, AKT, and NF-κB, leading to enhanced T cell activation and a decreased proportion of Treg cells in Pp6fl/fl-Lckcre mice.24 However, whether Pp6 modulates the phosphorylation of Akt at Ser473/Thr308 and FoxP3 expression in Treg cells remain unexplored.

In view of the known Pp6 regulation of Treg cells and FoxP3 expression, in this study, we used Pp6 conditional deletion in Treg cells of (Pp6fl/fl-FoxP3GFP-cre, cKO) mice and determined the possible role of Pp6 in Treg cell function and stability and depict the mechanisms. We showed that Pp6 conditional knockout (cKO) in Treg cells led to spontaneous autoinflammation in mice and diminished FoxP3 expression in Treg cells. Loss of Pp6 in Treg cells impaired their immunosuppressive function and exacerbated experimental colitis and EAE. Mechanistically, Pp6 deficiency increased CpG motif methylation of the FoxP3 locus by impairing the dephosphorylation of Dnmt1 and enhancing Akt signaling, leading to reduced FoxP3 in Treg cells. We identified Pp6 as a critical positive regulator of FoxP3 that maintains Treg cell stability and prevents autoimmune diseases.

Materials and methods

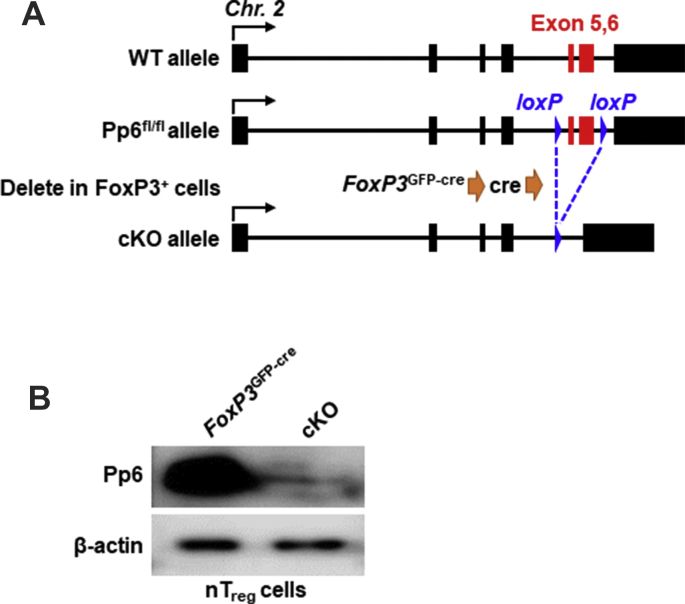

Mice

Pp6fl/fl mice bearing loxP-flanked exons 5–6 of the Pp6 gene were hybridized with FoxP3GFP-cre mice to gain the specific cre-mediated deletion of Pp6 in FoxP3+ cells (Pp6fl/fl-FoxP3GFP-cre, cKO) mice. Genotype identification of the cKO mice by RT-PCR was shown in our previous paper.10 The background of FoxP3GFP-cre mice was described as previous study21,22 and the FoxP3GFP-cre mice were kindly provided by Dr. Zhou Xuyu (Institute of Microbiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Shanghai, China). The background of Pp6fl/fl mice was described in previous study23 and the Pp6fl/fl mice were kindly provided by Dr. Tao Wufan (National Center for International Research of Development and Disease, School of Life Sciences, Fudan University, Shanghai, China). Rag1−/− mice were obtained from the Model Animal Research Center of Nanjing University.

All in vivo and in vitro experiments were performed on 6- to 13-week-old mice. All mice were kept under specific pathogen-free (SPF) conditions in compliance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals with the approval (SYXK-2018-0027) of the Scientific Investigation Board of Shanghai Jiaotong University School of Medicine. Mice used in disease models were euthanized by CO2 inhalation when recommended to ameliorate any further suffering.

Cell culture

EL-4 cells were cultured in DMEM high glucose (HyClone) with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. All cells were grown at 37 °C, 5% CO2.

Flow cytometric analysis

Single-cell suspensions from mouse tissues were prepared in PBS containing 2% FBS. Cells were fixed and permeabilized with a Cytofix/Cytoperm kit (BD Biosciences) or FoxP3/Transcription Factor Staining Buffer Set (eBioscience). For surface marker analysis, cells were stained with the indicated antibodies (Abs) in PBS containing 2% FBS. Intracellular staining was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. The following antibodies were used: anti-mouse CD4 APC-cy7, anti-mouse CD25 BV421/PE, anti-mouse FoxP3 APC, anti-mouse CD62L APC, anti-mouse CD44 PE, anti-mouse IFN-γ PE, anti-mouse IL-17A APC, anti-CD4 APC, and anti-Foxp3 PE from BioLegend. The anti-mouse/rat Ki67 was purchased from ebioscience. The anti-Akt-pSer473 rabbit antibody and anti-Akt-pThr308 rabbit antibody were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology as primary antibodies, and the donkey anti-rabbit AF594 secondary antibody was purchased from Invitrogen. Finally, the cells were washed, resuspended, and analyzed with a BD LSRFortessa X-20 flow cytometer.

ELISA

Quantitative analysis of IL-17A and IFN-γ in plasma of mouse was performed by ELISA using commercially available kits (Mouse IL-17A: Anogen, #MEC1001, mouse Interferon-Gamma (IFN-γ): Anogen, #MEC1002).

Histological analysis

The mouse tissue and organ samples were fixed in formalin and embedded in paraffin. Sections (6 μm) were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Image analysis was performed using a Leica SP8 X confocal microscope.

Western blot analysis

Cells were directly lysed by RIPA lysis buffer (Beyotime) on ice, and proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE gels. Separated proteins were transferred to a PVDF membrane (Millipore), and the membrane was incubated for 1 h in TBS buffer (20 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 500 mM NaCl) containing 5% BSA and 0.1% Tween 20 at room temperature. The membranes were incubated with primary antibody overnight at 4 °C and subsequently washed three times with TBS buffer containing 0.1% Tween 20. Then, the membranes were incubated with HRP secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature. After washing and incubation with HRP substrate, signals were detected by an Amersham Imager 600 (GE). The following antibodies were used: anti-Pp6 (Millipore/Santa Cruz), anti-Akt (Cell Signaling Technology), anti-Akt-pSer473 (Cell Signaling Technology), anti-Akt-pThr308 (Cell Signaling Technology), anti-Actin (Beyotime), anti-pStat5 (Cell Signaling Technology), anti-FoxP3 (Abcam), anti-pJak3 (Cell Signaling Technology), anti-pSmand2/3 (Cell Signaling Technology), and anti-Smand2/3 (Abcam).

Induction of experimental allergic encephalomyelitis (EAE)

EAE was induced by complete Freund's adjuvant (CFA)-MOG35–55 peptide immunization (China Peptides Biotechnology) and scored daily. Briefly, cKO/control mice were injected subcutaneously into the base of the tail with a volume of 200 μl containing 300 μg MOG35–55 peptide emulsified in CFA (Sigma–Aldrich). Mice were also injected intravenously with 200 ng of pertussis toxin (Merck-Calbiochem) on days 0 and 2 postimmunization. All the reagents used for in vivo experiments were free of endotoxin. Mice were monitored daily for the development of disease, which was scored according to the following scale: 0, no symptoms; 0.5, partial limp tail; 1, complete limp tail; 2, the mouse was paralyzed in one hind limb; 3, both hind limbs were paralyzed, mouse drags hind limbs when crawling forward; 4, the mouse lost the use of both forelimbs, leaving the mouse immobile; 5, moribund and the body curled up; and 6, death.

Adaptor transfer

For adoptive transfer, freshly isolated CD4+ CD25- CD45RBhi T cells from WT C57 mice and CD4+ CD25+ GFP+ Treg cells from FoxP3GFP-cre or cKO mice were obtained by FACS Sorting. Rag1−/− mice were coinjected with CD4+CD25−CD45RBhi T cells (5 × 105) and control/cKO nTreg cells (2 × 105) i.v. and weighed every day.

Treg cell induction

Mice were sacrificed, their spleens were removed and gently dissociated into single-cell suspensions. Naïve T cells were isolated using the MojoSort Mouse CD4 Naïve T Cell Isolation Kit (BioLegend). T cells were cultured in U-bottom 96-well plates with RPMI 1640 culture medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco), 2 mM l-glutamine, 1% antibiotic-antimycotic (Gibco), 10 mM HEPES (Gibco), 1× nonessential amino acids (Gibco), 1 mM sodium pyruvate (Gibco), and 55 μM β-mercaptoethanol (Gibco). Naïve T cells were activated with plate-bound anti-CD3 (3 μg/ml; Bio X Cell) and soluble anti-CD28 (2 μg/ml; Bio X Cell) antibodies. Treg cell differentiation was achieved by the indicated concentration of recombinant human TGF-β (R&D). The Akt inhibitor MK-2206 and afuresertib were purchased from MedChemExpress (MCE). Cells were cultured for 72 h and detected by flow cytometry.

Immunoprecipitation

To determine the interaction between Pp6 and Dnmt1 or Akt, EL-4 cells were lysed by RIPA buffer or WB-IP buffer (Beyotime). Equal amounts of lysates were incubated with protein A/G magnetic beads (Bimake) and antibodies, including Pp6 antibody (Millipore), Dnmt1 antibody (Abcam), or Akt antibody (Cell Signaling Technology). The prepared mixture was incubated overnight at 4 °C with agitation. The mixture was washed three times with PBS or lysis buffer and boiled in sample buffer. Then, the prepared immunoprecipitation complex was eluted for Western blot analysis to determine the interacting protein levels. Total cell protein was used as an input. The specificity of antibodies used for immunoprecipitation was routinely validated by using a negative control IgG.

Phos-tag SDS/PAGE

Briefly, for Mn2+ Phos-tag SDS/PAGE, 50 μM acrylamide-pendant Phos-tag ligand (APExBIO) and 100 μM MnCl2 were added to a 6% separating gel before polymerization. Phos-tag SDS/PAGE was performed as described previously.24

Bisulfite sequencing PCR

Genomic DNA was denatured, modified with sodium metabisulfite, purified, and desulfonated. The FoxP3 upstream enhancer CpG motif located −5.7 kb from the TSS was PCR amplified using 5′-AATGTGGGTATTAGGTAAAATTTTT-3’ (forward) and 5′-AAACCCTAAAACTACCTCTAAC-3’ (reverse) primers. The TSDR located −2.5 kb from the CDS was PCR amplified using 5′-AGGAAGAGAAGGGGGTAGATA-3’ (forward) and 5′-AAACTAACATTCCAAAACCAAC-3’ (reverse) primers. PCR products were separated on agarose gels, excised, and cloned into the pGEM-T easy vector (Promega). Recombinant plasmid DNA from the individual bacterial colonies was purified and sequenced.

Statistics

The data were analyzed with GraphPad Prism 8 and are presented as the mean ± s.e.m. Student's t-test was used when two conditions were compared, and analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni or Newman–Keuls correction was used for multiple comparisons. Error bars indicate the mean ± s.e.m. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant (ns = not significant, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001).

Results

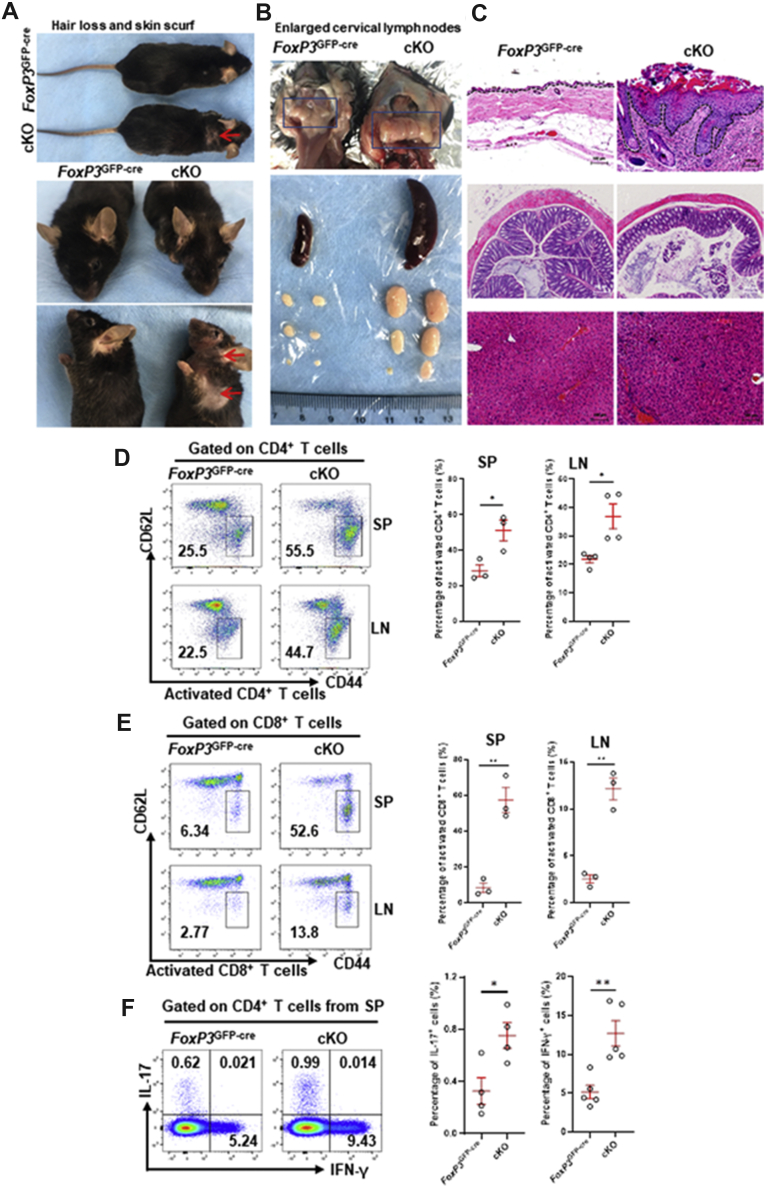

Mice with Pp6 conditional deletion in Treg cells spontaneously develop autoimmunity

We previously reported that Pp6 is a critical regulator in the differentiation of Treg cells that regulates Ang II-induced blood pressure elevation.10 To investigate the role of Pp6 in Treg-related autoimmune diseases, we generated mice with conditional Pp6 knockout in Treg cells (Pp6fl/fl-FoxP3GFP-cre, cKO) (Fig. S1A). Depletion of Pp6 was confirmed with high efficiency in Treg cells by Western blot (Fig. S1B). We compared cKO mice with FoxP3GFP-cre control mice, and found that cKO mice at 3 months of age developed inflammatory symptoms similar to scurfy mice (FoxP3 mutant mice)7: hair loss in head and neck, thickening and roughening of skin, skin scurf, and acanthoid (Fig. 1A); considerably enlarged spleens and lymph nodes (Fig. 1B), increased inflammatory cell infiltration, and distinct inflammatory patterns in skin (top), colon (middle) and liver (bottom) by histological analysis (Fig. 1C). Together, these data suggest that specific deletion of Pp6 in CD4+FoxP3+ Treg cells leads to spontaneous autoinflammation.

Figure 1.

Pp6fl/fl-FoxP3GFP-cre mice spontaneously develop autoimmunity and inflammation. Comparison of the FoxP3GFP-cre (control) mouse to the Pp6fl/fl-FoxP3GFP-cre (cKO) mouse (three months of age). (A) Autoimmune signatures appeared in the cKO mouse. Hair loss and skin scurf are marked by red arrows. (B) The spleens and lymph nodes of cKO mice were significantly enlarged. Enlarged cervical lymph nodes are marked by blue boxes. (C) Representative hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining of skin (top), colon (middle) and liver (bottom) sections from cKO/control mice. The dotted line indicates the border between the epidermis and the dermis; scale bar. Scar bars, 100 μm or 200 μm. Representative sections from four mice are shown. (D–H) Spleen (SP) or lymph node (LN) single-cell suspensions from cKO/control mice were probed by flow cytometry with the indicated antibodies. Representative flow cytometric analysis of CD62L and CD44, showing the activated CD4+ T cell (D) and activated CD8+ T cell (E) percentages after gating on CD4+ T cells or CD8+ T cells, respectively. Representative flow cytometric analysis of IL-17 and IFN-γ after gating on CD4+ T cells, showing the proportion of Th1 and Th17 cells (F). Data are representative of 3–4 independent experiments. Quantification of cells on the right. (G) Release of IL-17A and IFN-γ from the plasma of control/cKO mice. The plasma was recovered and the concentrations of IL-17A and IFN-γ were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Data are presented as the mean ± s.e.m.of 6 independent experiments. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01 by Student's t-test. Error bars indicate the mean ± s.e.m.

Prompted by these autoinflammatory phenotypes, we further compared the activation state of immune cells derived from cKO mice and FoxP3GFP-cre control mice by flow cytometry. We found that the percentages of activated CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (CD4+ CD44hi CD62Llow T cells and CD8+ CD44hi CD62Llow T cells) were markedly increased in the spleens and lymph nodes of cKO mice (Fig. 1D, E), and the percentages of Th17 and Th1 cells were also elevated in the spleens of cKO group (Fig. 1F). We also examined the plasma level of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-17A and IFN-γ by ELISA, and found cKO mice developing autoinflammation spontaneously have higher level of IL-17A, but no change of IFN-γ in plasma in comparison to control mice (Fig. 1G). Collectively, our data demonstrates that conditional ablation of Pp6 in Treg cells leads to the spontaneous development of autoimmunity and inflammation in mice.

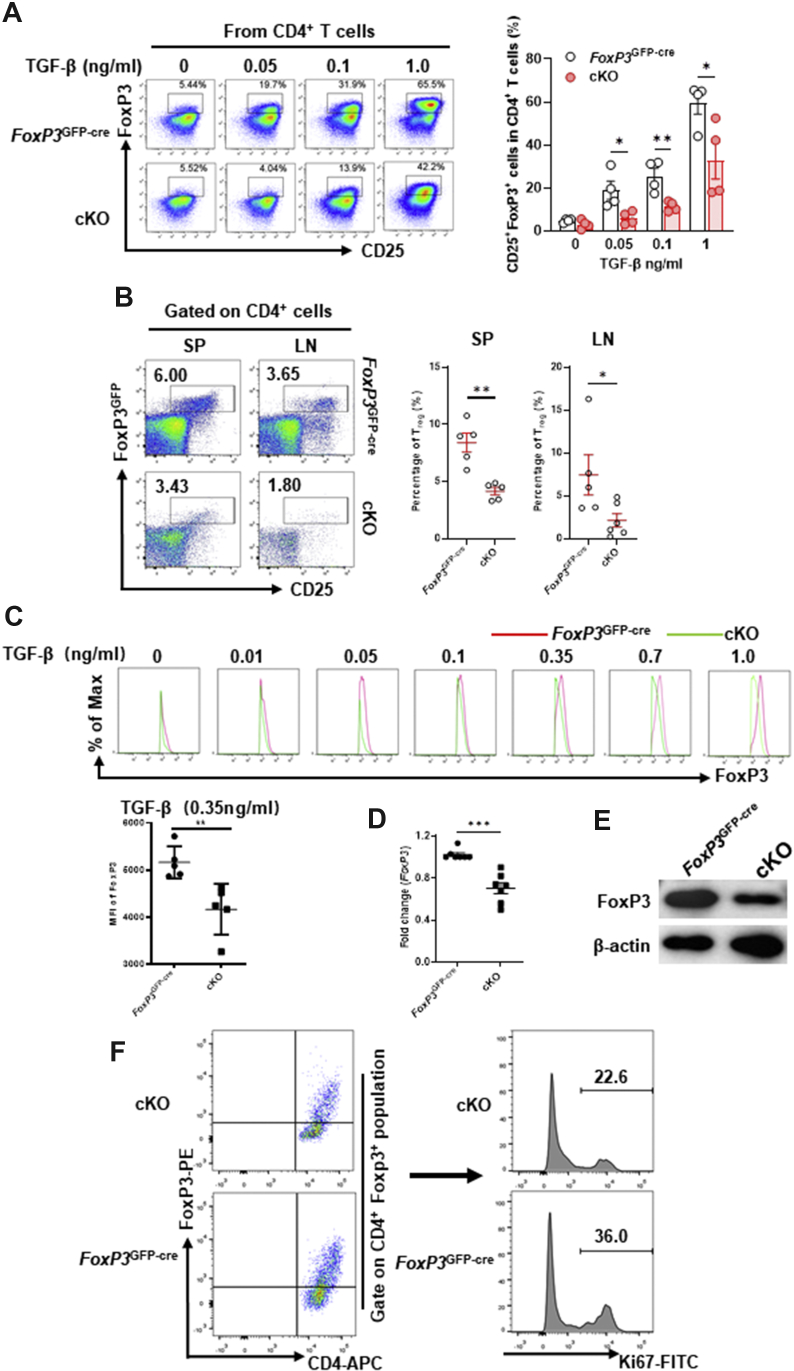

Pp6 deficiency leads to diminished FoxP3 expression in Treg cells

Next, we sought to better define the role of Pp6 as a modulator of Treg cell development. First, we found that the lack of Pp6 markedly inhibited Treg cell differentiation from naïve CD4+ T cells of cKO mice compared with Foxp3GFP−Cre controls in vitro (Fig. 2A), which is consistent with our previous study.10 Our in vivo results further demonstrated that cKO mice present a much lower proportion of natural Treg (nTreg) cells in the spleen and lymph nodes (Fig. 2B). Second, we investigated the expression of FoxP3 in iTreg cells derived from control and cKO mice and found that FoxP3 protein levels in cKO iTreg cells were lower than those in control iTreg cells, and that this reduction was TGF-β concentration dependent (Fig. 2C). Moreover, both FoxP3 mRNA and protein levels were markedly decreased in cKO iTreg cells (Fig. 2D, E). Third, we examined the proliferative function of iTreg cells derived from control and cKO mice by flow cytometry and found that Ki67 expression in cKO iTreg cells (CD4+ Foxp3+ populations) were lower than those in control iTreg cells (Fig. 2F). These results suggest that Pp6-deficient Treg cells appear to have unstable expression of FoxP3 and strongly indicate that Pp6 is a critical regulator that maintains the stability of FoxP3 and the functional stability of Treg cells.

Figure 2.

Pp6 deficiency reduces FoxP3 expression in Treg cells. Naïve CD4+ T cells isolated from the spleen of cKO/control mice were induced to differentiate into Treg (iTreg) cells in vitro with different concentrations of TGF-β. Flow cytometric staining for CD25 and FoxP3 after gating on CD4+ T cells; numbers in panels demonstrate the proportion of iTreg cells (CD4+ CD25+ FoxP3+) in each. Statistical chart showing the quantification of iTreg cell percentages (n = 4). (B) Flow cytometric detection of CD25 and FoxP3GFP after gating on CD4+ T cells, showing the proportion of nTreg cells isolated from cKO/control mouse spleens and lymph nodes (statistical charts on the right). (C–E) The expression of FoxP3 in iTreg cells derived from control and cKO mice was investigated by flow cytometric staining for FoxP3 after gating on CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ T cells, statistical chart showing FoxP3 MFI at 0.35 ng/ml TGF-β concentration (C, n = 3–5), RT-PCR (D, n = 7), and Western blot (E, data are representative of three independent experiments). (F) The expression of Ki67 in iTreg cells (CD4+ Foxp3+ populations) derived from control and cKO mice was investigated by flow cytometric staining for anti-CD4 APC, anti-Foxp3 PE and anti-Ki67 FITC after gating on CD4+ FoxP3+ T cells. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01 by Student's t-test. Error bars the indicate mean ± s.e.m.

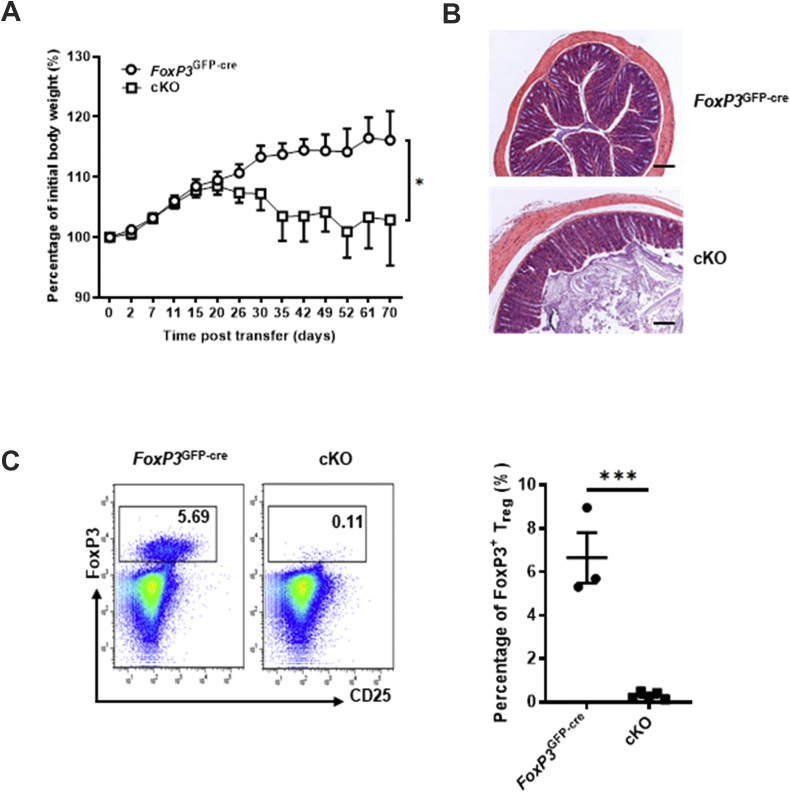

Loss of Pp6 in Treg cells impairs their immunosuppressive function in vivo and exacerbates experimental colitis

Decreased FoxP3 levels indicate an impaired function of Treg cells. To evaluate whether the immunosuppression of Pp6−/− Treg cells is disrupted in cKO mice, we established a mouse adoptive transfer colitis model. Rag1−/− mice that received WT naïve T cells and Pp6−/− Treg cells had significant weight loss and colon tissue damage, while the adoptive transfer of control Treg cells protected mice from colitis (Fig. 3A, B). Consistently, the numbers of FoxP3+ Treg cells in the spleens of mice adoptively transferred with Pp6−/− Treg cells were dramatically decreased at the end of this model (on day 70), suggesting that Pp6 is very important to maintaining the Treg cell population (Fig. 3C). These data indicated that Pp6 deficiency in Treg cells aggravated the colitis development induced by effector T cells and suffered from disabled Treg cell immunosuppressive function.

Figure 3.

Impaired immunosuppressive function of Pp6−/− Treg cells in vivo. We constructed an adoptive transfer colitis mouse model in Rag1−/− mice (coinjected naïve T cells isolated from C57 WT mice with Treg cells sorted from either FoxP3GFP-cre control mice or cKO mice) and built two groups of mice: FoxP3GFP-cre and cKO. (A) Body weight changes of the above two groups of colitis model mice (n = 10). ∗P < 0.05 by Two-way ANOVA. (B) Representative H&E histology images of colons from the above two groups of colitis model mice on day 70 (bars represent 200 μm). Representative sections from six mice are shown. (C) Flow cytometric staining for CD25 and FoxP3 after gating on CD4+ T cells, showing the proportion of Treg cells from the spleen of the above two groups of colitis model mice on day 70. Statistical chart of the above two groups of colitis model mice showing the quantification of Treg cell percentages (n = 3 or 5). ∗∗∗P < 0.001 by Student's t-test. Error bars indicate the mean ± s.e.m.

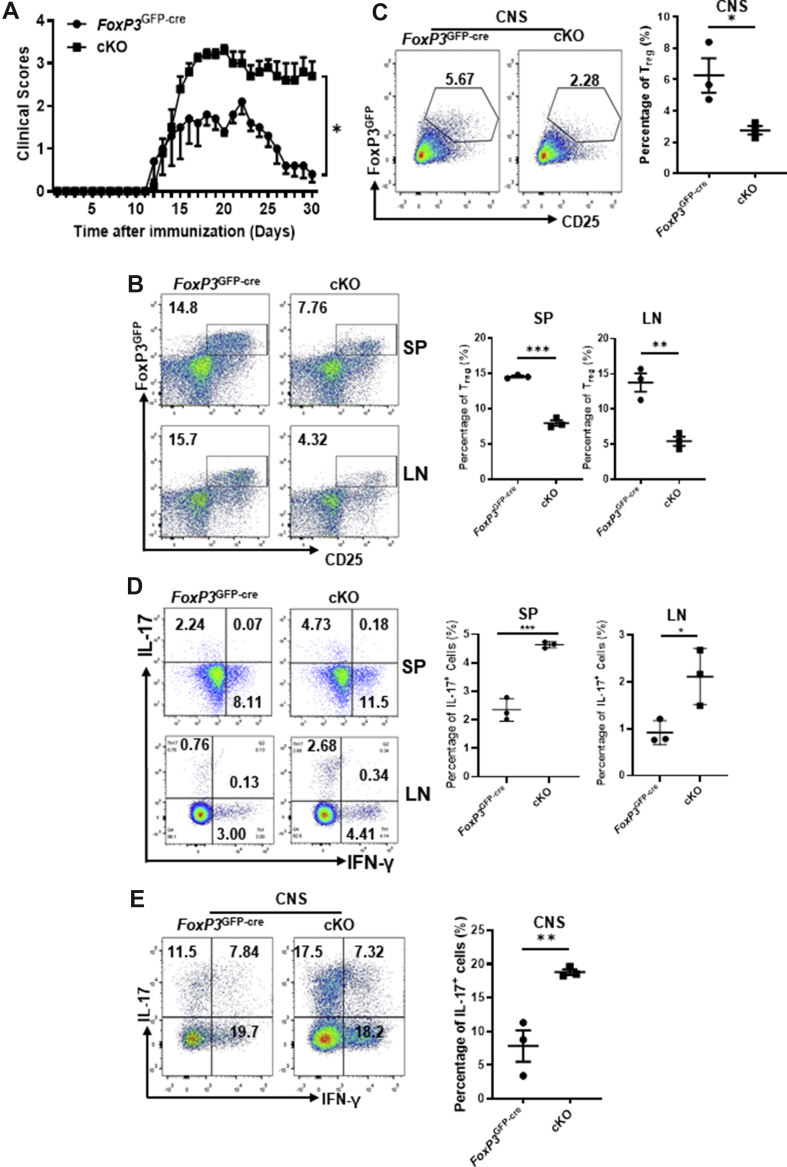

Loss of Pp6 in Treg cells exacerbates autoimmune disease

To further define the role of Pp6 in Treg-related autoimmune disease, we took advantage of experimental allergic encephalomyelitis (EAE), a classical model of autoimmunity immunosuppressed by Treg cells that is widely used to examine Treg cell functions. EAE was established, and clinical manifestations started to appear on day 10 upon immunization in FoxP3GFP-cre and cKO mice. We found that the disease score of the cKO group was significantly higher than that of the control group (Fig. 4A). Furthermore, flow cytometry results showed that the CD25+ FoxP3+ Treg cells decreased in the spleen, lymph nodes, and CNS of the cKO EAE model mice (Fig. 4B, C). Correspondingly, the proportion of Th17 cells in the above three organs of cKO mice was higher than that in the control group, while the proportion of Th1 cells remained unchanged (Fig. 4D, E). These results suggest that the development of Treg cells in cKO mice is impaired and fails to inhibit the overactivated immune response mediated by effector T cells, eventually leading to a more severe EAE outcome.

Figure 4.

Loss of Pp6 in Treg cells exacerbates EAE. We constructed an EAE mouse model in cKO and FoxP3GFP-cre (control) mice for two groups: cKO and FoxP3GFP-cre. (A) The clinical scores of cKO and FoxP3GFP-cre mice were investigated during the progression of mouse EAE (n = 5). ∗P < 0.05 by Two-way ANOVA. (B, C) Flow cytometric detection of CD25 and FoxP3GFP after gating on CD4+ T cells, showing the proportion of Treg cells from the spleen (SP), lymph nodes (LN) (B) or central nervous system (CNS) (C) of the above two groups of EAE model mice. Statistical chart showing the quantification of Treg cell percentages (n = 3). (D, E) Flow cytometric staining for IL-17 and IFN-γ after gating on CD4+ T cells, showing the proportion of Th1 and Th17 cells from SP and LN (D), CNS (E) of the above two groups EAE model mice. Statistical chart showing the quantification of Th17 and Th1 cell percentages (n = 3). ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001 by Student's t-test. Error bars indicate the mean ± s.e.m.

Pp6 deficiency increased CpG motif methylation at the FoxP3 locus by impairing dephosphorylation of Dnmt1 in Treg cells

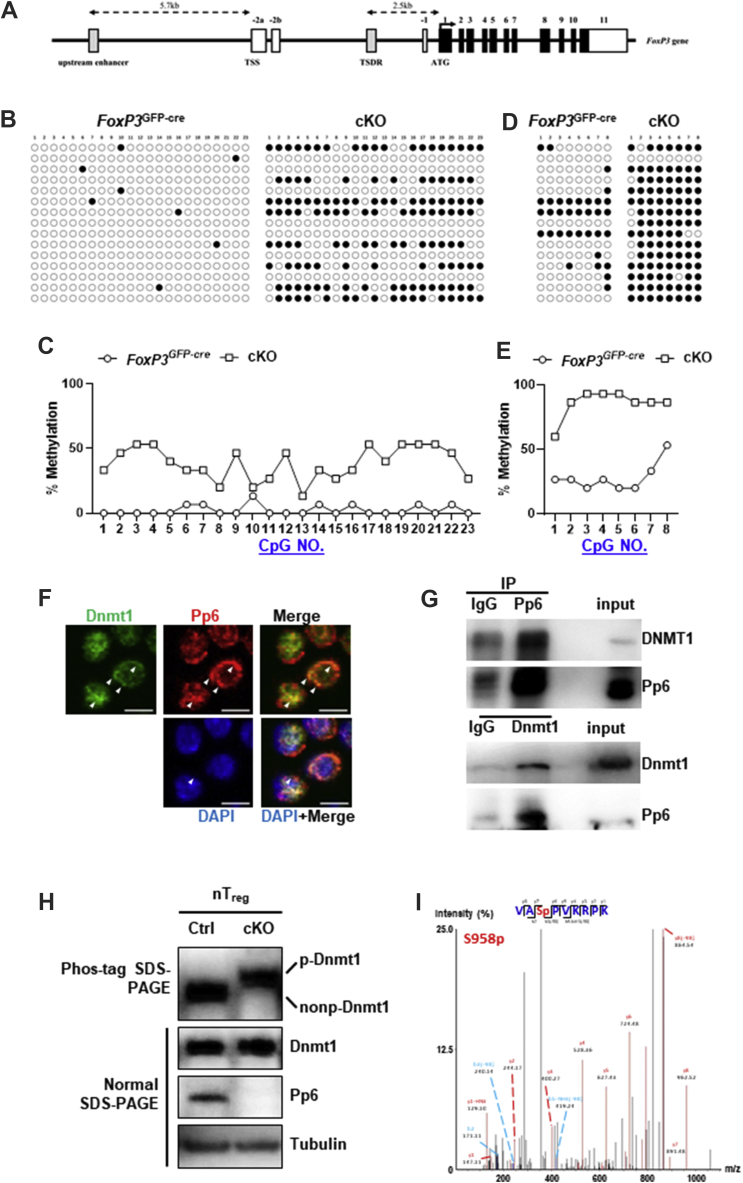

Our data strongly suggest the instability of FoxP3 expression and fragility of Treg cells in Pp6 knockout mice. The transcriptional initiation of FoxP3 is mediated by several signaling pathways, while CpG motif methylation of the FoxP3 locus controls the stability of FoxP3 expression.25 To elucidate the mechanism, we investigated the level of CpG motif methylation of the FoxP3 locus in cKO Treg cells. We analyzed the methylation levels of canonical and noncanonical CpG motifs by bisulfite sequencing PCR (BSP). Specifically, the FoxP3 upstream enhancer is located −5.7 kb from the TSS, containing 23 CpGs as the noncanonical CpG motif, and the Treg-specific demethylated region (TSDR) is located −2.5 kb from the CDS, containing 8 CpGs as the canonical CpG motif (Fig. 5A). In WT mice, both CpG motifs are methylated in naïve T cells and effector T cells but demethylated in nTreg cells.26,27 In contrast, we found that the DNA methylation of CpG in the upstream enhancer and TSDR were both increased in cKO nTreg cells (Fig. 5B–E).

Figure 5.

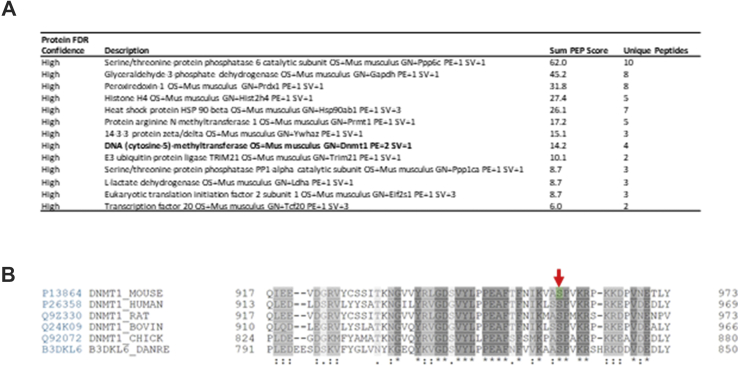

Pp6 deficiency increased the CpG motif methylation of the FoxP3 locus and bated the dephosphorylation of Dnmt1 in Treg cells. (A) Schematic view of the FoxP3 locus depicting the positioning of upstream enhancers and Treg-specific demethylated regions (TSDRs). (B) Assessment of DNA methylation of the upstream FoxP3 enhancer CpG island in cKO and FoxP3GFP-cre nTreg cells was determined by bisulfite sequencing PCR (BSP). Open circles indicate demethylated CpG, and closed circles indicate methylated CpG. (C) Statistical chart showing the quantification of methylated CpG percentage for each site. (D) Assessment of TSDR DNA methylation in cKO and FoxP3GFP-cre nTreg cells was determined by BSP. Open circles indicate demethylated CpG, and closed circles indicate methylated CpG. (E) Statistical chart showing the quantification of methylated CpG percentage for each site. (F) CD4+ T cells isolated from WT mouse spleens were fixed and immunostained with Pp6 (red), Dnmt1 (green) and DAPI (blue). Colocalized Pp6 and Dnmt1 were displayed in merge (yellow) by confocal microscopy. The bar represents 5 μm. (G) Cell lysates from EL-4 cells were subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP) using anti-Pp6 or anti-Dnmt1 antibodies, followed by immunoblotting with anti-Pp6 or anti-Dnmt1 antibodies, respectively. (H) nTreg cells isolated from cKO and FoxP3GFP-cre (Ctrl) mice were lysed and analyzed by Phos-tag SDS-PAGE and normal SDS-PAGE Western blot. The blots were probed with antibodies against Pp6, Dnmt1 and tubulin. (I) The mass spectrum data show the phosphorylation site of the Dnmt1 protein extracted from EL-4 cells.

To determine how Pp6 modulates CpG motif methylation of FoxP3 locus events, we first looked for Pp6 binding proteins by immunoprecipitating overexpressed Pp6 in the mass spectrum and found a Pp6 binding candidate, Dnmt1 (Fig. S3A), which is an enzyme for DNA methylation and has been considered an critical factor for Treg cell development.14,27 To verify Dnmt1 as a substrate of Pp6 and confirm their interactions in vivo, we first immunostained endogenous Dnmt1 and Pp6 in CD4+ T cells and detected the signals by confocal microscopy. As expected, Dnmt1 (green) and Pp6 (red) were frequently colocalized in both the cytoplasm and nuclei, as shown in merged images (yellow) (Fig. 5F). Second, for the protein–protein interaction, we immunoprecipitated Pp6 or Dnmt1 from EL-4 cell lysates and then detected both endogenous Pp6/Pp6 and Dnmt1/Dnmt1 by Western blot (Fig. 5G). Together, these results demonstrate that Pp6 colocalized and directly interacted with Dnmt1. Third, we detected Dnmt1 phosphorylation in Ctrl/cKO nTreg cell lysates using the Phos-tag SDS-PAGE system, which could shift the phosphorylated protein above the nonphosphorylated protein in the gel. The results clearly showed that Dnmt1 was phosphorylated in cKO cells compared to control cells (Fig. 5H). To further identify the specific phosphorylation site of Dnmt1, we identified by mass spectrometry that Ser958 was the phosphorylation site of Dnmt1 in EL-4 T cells (Fig. 5I). Interestingly, pSer958 is in a p-serine-proline sequence, a motif reported as a proline-directed (phospho-Ser-Pro) dephosphorylation site of Pp6.28 In homology analysis, the nearby protein sequence of Ser958 shows high homology among humans, mice, rats, bovines, chickens, and zebrafish, especially Ser958 and Pro959, which are in the Pp6 dephosphorylation site motif (Fig. 3B). These results indicate that pSer958 is an important phosphorylation site of Dnmt1 in T cells and is highly likely to be the dephosphorylation site of Pp6.

Together, our data shows that Pp6 probably dephosphorylates Dnmt1 in Treg cells and impairs CpG motif methylation of the FoxP3 locus, which leads to stable expression of FoxP3 and functional Treg cell development. Ultimately, these actions balance the immune system and avoids autoimmunity development.

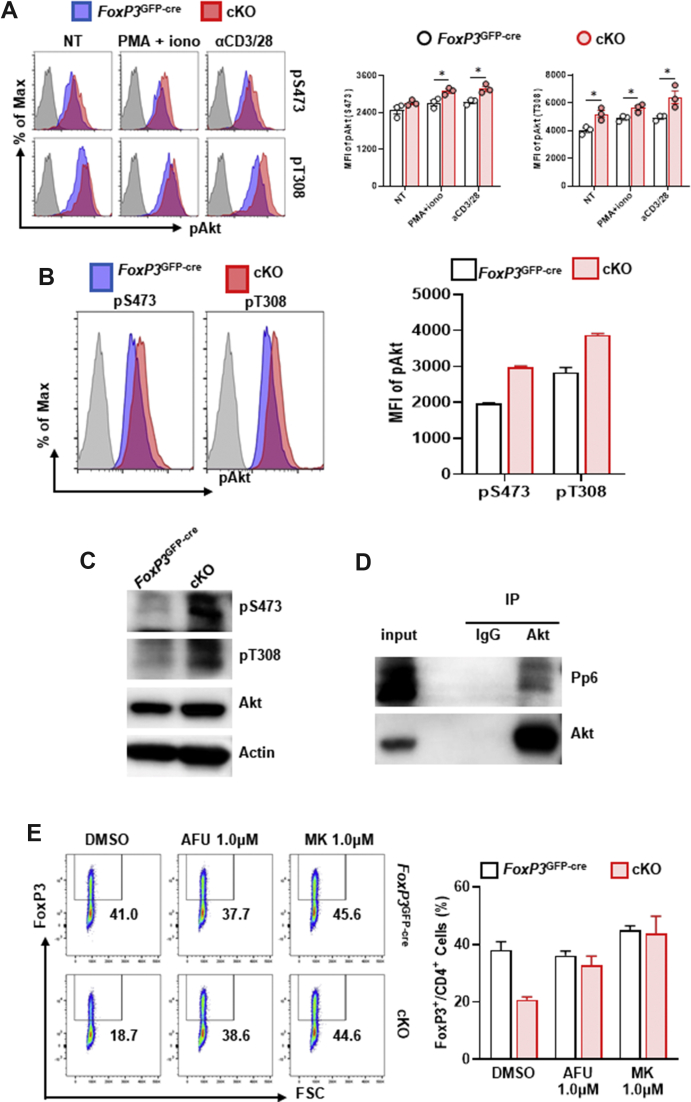

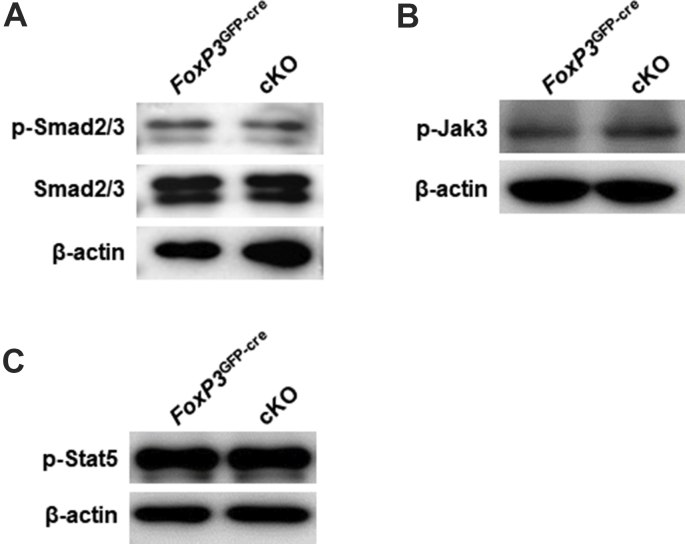

Loss of Pp6 enhances Akt signaling, leading to diminished levels of FoxP3 in Treg cells

FoxP3 is inhibited by the Akt pathway, which is a key event for Treg cell stability.18,37 Therefore, we assessed phosphorylated Akt at S473 and T308 by flow cytometry in FoxP3+ CD4+ Treg cells from control/cKO mouse spleens. Under stimulation with PMA/ionomycin or anti-CD3/CD28, both pS473 and pT308 were significantly increased (Fig. 6A). Consistently, FoxP3+ CD4+ cKO iTreg cells displayed hyperactivated Akt at pS473 and pT308 compared with the control group (Fig. 6B, D). Furthermore, we detected an endogenous interaction between Akt and Pp6 by Western blot in the EL-4 mouse T cell line (Fig. 6C). To confirm whether the effect of Pp6 in Treg cells depends on Akt activation, we used two kinds of inhibitors of Akt (afuresertib [AFU] and MK-2206 [MK])29,30 to treat iTreg cells in vitro and found that inhibition of Akt rescued the iTreg cell proportion in the cKO group to the same level as that in the control group (approximately 20%–40%). Conversely, iTreg cells in the control group showed no difference from Akt inhibitor treatment (Fig. 6E), indicating an inactivated Akt signal in normal Treg cells. Here, we demonstrate that Pp6 is able to restrict Akt phosphorylation and that Pp6 deficiency impairs FoxP3 expression through excessive Akt signaling.

Figure 6.

Loss of Pp6 enhances Akt signaling, leading to impaired FoxP3 in Treg cells. (A) Representative histograms of phosphorylation levels of pAKT-S473 and T308 after gating on FoxP3+ CD4+ T cells from cKO or control mouse spleens under different activation conditions; Iono (ionomycin), αCD3/28 (anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 antibodies). Statistical charts on the right, n = 3. (B, C) Naïve CD4+ T cells isolated from the spleen of cKO/control mice were induced to differentiate into Treg (iTreg) cells in vitro. The phosphorylation levels of pAKT-S473 and T308 in iTreg cells were measured by flow cytometry after gating on FoxP3+ CD4+ T cells (B) and Western blot (C), statistical chart on the right. (D) Endogenous immunoprecipitation was performed using an anti-Akt antibody from EL-4 cells, followed by immunoblotting with anti-Pp6 or anti-Akt antibodies. (E) iTreg cells from cKO/control mice were treated with DMSO, afuresertib (AFU) or MK-2206 (MK). Flow cytometric detection of FoxP3 after gating on CD4+ T cells. Statistical chart showing the proportion of iTreg cells. Data are representative of two independent experiments. ∗P < 0.05 by Student's t-test. Error bars indicate the mean ± s.e.m.

Collectively, our data shows that Pp6 diminishes pAkt at S473 and T308 in Treg cells, which maintains FoxP3 expression and functional Treg cell development. Pp6 is a critical factor that balances the immune system and prevents the development of autoimmunity.

Discussion

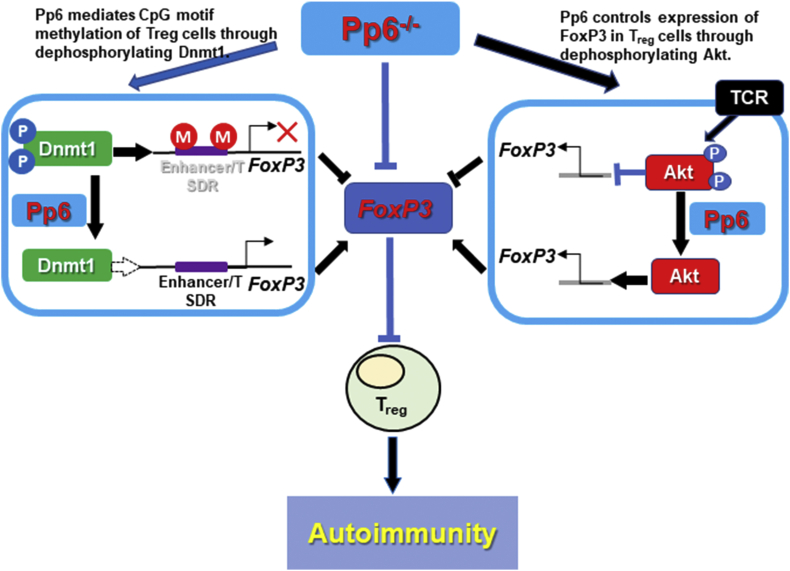

In this study, using mice with conditional Pp6 deletion in Treg cells, we showed that Pp6 is an essential positive regulator of FoxP3, maintains Treg cell stability and prevents autoimmune diseases by decreasing DNA methylation of the FoxP3 gene enhancer and inhibiting Akt signaling (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

Scheme for Pp6 as a critical positive regulator of FoxP3 that dephosphorylates Dnmt1 and inhibits Akt signaling to maintain Treg cell stability and prevent autoimmunity. Pp6 decreased DNA methylation of the FoxP3 gene enhancer and Treg-specific demethylated region (TSDR) by dephosphorylating Dnmt1, resulting in increased FoxP3, and Pp6 abated phosphorylation of Akt, leading to enhanced FoxP3 in Treg cells.

Both FoxP3 expression and establishment of a Treg cell-specific hypomethylation pattern are indispensable for Treg cell stability and function.31 DNA methylation is generally catalyzed by one or more DNA methyltransferase (Dnmt) enzymes: Dnmt1, Dnmt3a, and Dnmt3b. Among them, Dnmt1 binds preferentially to hemimethylated DNA and re-establishes DNA methylation after its replication.32 Ablation of Dnmt1, but not Dnmt3a, decreased the numbers and function of peripheral Treg cells in vivo and impaired the conversion of naïve T cells to FoxP3+ Treg cells in vitro.14 More importantly, mice with conditional knockout of Dnmt1 in FoxP3+ Treg cells died of autoimmunity by 3–4 weeks of age unless they were rescued by perinatal transfer of WT Treg cells.14 These published data highlight that Dnmt1 is a critical regulator of FoxP3+ Treg cell development, stability, and function.

Kinase and phosphatase are the Yin and Yang proteins modified via phosphorylation and dephosphorylation. The human genome encodes 518 protein kinases but only approximately 200 phosphatases (approximately 30 protein serine/threonine phosphatases).33,34 Researchers generally pay more attention to protein kinases than protein phosphatases and consider the dephosphorylation of protein phosphatases to be a nonspecific physiological function. However, phosphatases also have a wide range of important functions, such as in the cell cycle, inflammation, immune response, DNA repair, cancer, and almost all physiological processes.9 In this study, we identified Pp6 as a critical protein phosphatase that dephosphorylates Dnmt1 in Treg cells and impairs CpG motif methylation of the FoxP3 locus, leading to stable expression of FoxP3 and functional Treg cell development. We previously reported that activation of the NF-κB signaling pathway is responsible for decreased expression levels of Pp6 in chronic inflammation35; targeted therapy to maintain Pp6 expression therefore harbors therapeutic potential for autoimmune diseases.

TCR signaling and constitutive Akt activation antagonize FoxP3 induction.36 Compared with kinases, research on phosphatases involved in Akt dephosphorylation is limited. PHLPP1/2 were reported to dephosphorylate Akt at Ser473 but not at Thr308,18,38 and PP2A is mainly responsible for mTOC1 dephosphorylation.19,20 Very interestingly, we demonstrated here that Pp6 directly interacts with Akt, and Pp6 knockout dramatically elevates the phosphorylation of Akt at Ser473 and Thr308, which strongly suggests that Pp6 is able to dephosphorylate pAkt at Ser473 and Thr308. Our findings prove the importance of Pp6 in Akt signaling mediation and reveal the network of the PI3K-Akt-mTOR pathway in Treg cells. Given that the PI3K-Akt-mTOR signaling network regulates FoxP3 expression and Pp6 is able to stabilize FoxP3, we suggest that Pp6 agonists could be considered for the treatment of autoimmune diseases or transplant rejection therapy. Conversely, Pp6 antagonists would also have potential benefits in antitumor immunotherapy.

In contrast to the TGF-β signaling pathway, which acts as an on/off switch, the methylation of the TSDR is generally reported to stabilize FoxP3 expression,25 but its regulation is not clear. In our study, compared with control Treg cells, Pp6-deficient Treg cells had enhanced DNA methylation of the upstream enhancer and TSDR, which is an unstable epigenetic state for Treg cells associated with Treg cell plasticity. However, Akt signaling was reported to have a negative role in DNA methylation mediation.39 Thus, our data indicate that the Akt signal is not responsible for the increased DNA methylation of the FoxP3 locus in Pp6-deficient Treg cells. Nevertheless, we found that Pp6 dephosphorylates Dnmt1 and impairs CpG motif methylation at the FoxP3 locus, stabilizing FoxP3 expression in Treg cells. The detailed regulatory network of Pp6, Akt, and Dnmt1 requires further investigation.

In conclusion, our results suggest that Pp6 decreased DNA methylation of the FoxP3 gene enhancer and abated phosphorylation of Akt, leading to stable expression of FoxP3 in Treg cells. Therefore, Pp6 may be a potential therapeutic target for the treatment of autoimmune diseases.

Author contributions

W.C., (Wei CAI) and J.Z., (Junxun ZHANG) (First authors), H.W., (Honglin WANG) and Q.L. (Qun LI) (Corresponding authors) designed the project, W.C., J.Z., H.Z., XX.L., and F.L. performed the experiments; Y.S., Z.X., J.B., Q.Y., Z.W., L.S., X.C., S.T., Y.W., L.F., H.W., and Q.L. analyzed the data, J.Z., Q.L., and H.W. wrote the manuscript, Q.L., and H.W. supervised the study. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict of interests

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Funding

This work is supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82070509, 81930088, 81725018), Innovative Research Team of High-Level Local Universities in Shanghai, and the Natural Science Foundation of Shanghai Science and Technology Committee, China (No. 20ZR1447400).

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. ZHOU Xuyu (Institute of Microbiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Shanghai, China) for kindly providing FoxP3GFP-cre mice. We thank Dr. TAO Wufan (National Center for International Research of Development and Disease, School of Life Sciences, Fudan University, Shanghai, China) for kindly providing Pp6fl/fl mice.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chongqing Medical University.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gendis.2021.07.005.

Contributor Information

Honglin Wang, Email: honglin.wang@sjtu.edu.cn.

Qun Li, Email: liqun@sibs.ac.cn.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

Suppl FigS1.

Suppl FigS2.

Suppl FigS3.

References

- 1.Pompura S.L., Dominguez-Villar M. The PI3K/AKT signaling pathway in regulatory T-cell development, stability, and function. J Leukoc Biol. 2018;103:1065–1076. doi: 10.1002/JLB.2MIR0817-349R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schallenberg S., Tsai P.Y., Riewaldt J., Kretschmer K. Identification of an immediate Foxp3(-) precursor to Foxp3(+) regulatory T cells in peripheral lymphoid organs of nonmanipulated mice. J Exp Med. 2010;207(7):1393–1407. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhou X., Bailey-Bucktrout S.L., Jeker L.T., et al. Instability of the transcription factor Foxp3 leads to the generation of pathogenic memory T cells in vivo. Nat Immunol. 2009;10(9):1000–1007. doi: 10.1038/ni.1774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bailey-Bucktrout S.L., Bluestone J.A. Regulatory T cells: stability revisited. Trends Immunol. 2011;32(7):301–306. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2011.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wing J.B., Tanaka A., Sakaguchi S. Human FOXP3(+) regulatory T cell heterogeneity and function in autoimmunity and cancer. Immunity. 2019;50(2):302–316. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li Z., Li D., Tsun A., Li B. FOXP3+ regulatory T cells and their functional regulation. Cell Mol Immunol. 2015;12(5):558–565. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2015.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yilmaz O.K., Haeberle S., Zhang M., Fritzler M.J., Enk A.H., Hadaschik E.N. Scurfy mice develop features of connective tissue disease overlap syndrome and mixed connective tissue disease in the absence of regulatory T cells. Front Immunol. 2019;10:881. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wildin R.S., Ramsdell F., Peake J., et al. X-linked neonatal diabetes mellitus, enteropathy and endocrinopathy syndrome is the human equivalent of mouse scurfy. Nat Genet. 2001;27(1):18–20. doi: 10.1038/83707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ohama T. The multiple functions of protein phosphatase 6. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res. 2019;1866(1):74–82. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2018.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li X., Cai W., Xi W., et al. MicroRNA-31 regulates immunosuppression in Ang II (Angiotensin II)-induced hypertension by targeting Ppp6C (protein phosphatase 6c) Hypertension. 2019;73(5):e14–e24. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.118.12319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Polansky J.K., Kretschmer K., Freyer J., et al. DNA methylation controls Foxp3 gene expression. Eur J Immunol. 2008;38(6):1654–1663. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hori S. Developmental plasticity of Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. Curr Opin Immunol. 2010;22(5):575–582. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2010.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen Z.X., Riggs A.D. DNA methylation and demethylation in mammals. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(21):18347–18353. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R110.205286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang L., Liu Y., Beier U.H., et al. Foxp3+ T-regulatory cells require DNA methyltransferase 1 expression to prevent development of lethal autoimmunity. Blood. 2013;121(18):3631–3639. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-08-451765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li C., Ebert P.J., Li Q.J. T cell receptor (TCR) and transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) signaling converge on DNA (cytosine-5)-methyltransferase to control forkhead box protein 3 (foxp3) locus methylation and inducible regulatory T cell differentiation. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(26):19127–19139. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.453357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xia Q., Zhang J., Han Y., et al. Epigenetic regulation of regulatory T cells in patients with abdominal aortic aneurysm. FEBS Open Bio. 2019;9(6):1137–1143. doi: 10.1002/2211-5463.12643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garg G., Muschaweckh A., Moreno H., et al. Blimp1 prevents methylation of Foxp3 and loss of regulatory T cell identity at sites of inflammation. Cell Rep. 2019;26(7):1854–1868. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.01.070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu Y., Xu Y., Sun J., et al. AKT hyperactivation confers a Th1 phenotype in thymic Treg cells deficient in TGF-β receptor II signaling. Eur J Immunol. 2014;44(2):521–532. doi: 10.1002/eji.201243291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Apostolidis S.A., Rodríguez-Rodríguez N., Suárez-Fueyo A., et al. Phosphatase PP2A is requisite for the function of regulatory T cells. Nat Immunol. 2016;17(5):556–564. doi: 10.1038/ni.3390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kasper I.R., Apostolidis S.A., Sharabi A., Tsokos G.C. Empowering regulatory T cells in autoimmunity. Trends Mol Med. 2016;22(9):784–797. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2016.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee E.C., Yu D., Martinez de Velasco J., et al. A highly efficient Escherichia coli-based chromosome engineering system adapted for recombinogenic targeting and subcloning of BAC DNA. Genomics. 2001;73(1):56–65. doi: 10.1006/geno.2000.6451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhou X., Jeker L.T., Fife B.T., et al. Selective miRNA disruption in T reg cells leads to uncontrolled autoimmunity. J Exp Med. 2008;205(9):1983–1991. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ye J., Shi H., Shen Y., et al. PP6 controls T cell development and homeostasis by negatively regulating distal TCR signaling. J Immunol. 2015;194(4):1654–1664. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1401692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sugiyama Y., Hatano N., Sueyoshi N., et al. The DNA-binding activity of mouse DNA methyltransferase 1 is regulated by phosphorylation with casein kinase 1delta/epsilon. Biochem J. 2010;427(3):489–497. doi: 10.1042/BJ20091856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huehn J., Polansky J.K., Hamann A. Epigenetic control of FOXP3 expression: the key to a stable regulatory T-cell lineage? Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9(2):83–89. doi: 10.1038/nri2474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Floess S., Freyer J., Siewert C., et al. Epigenetic control of the foxp3 locus in regulatory T cells. PLoS Biol. 2007;5(2):e38. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lal G., Zhang N., van der Touw W., et al. Epigenetic regulation of Foxp3 expression in regulatory T cells by DNA methylation. J Immunol. 2009;182(1):259–273. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.1.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rusin S.F., Schlosser K.A., Adamo M.E., Kettenbach A.N. Quantitative phosphoproteomics reveals new roles for the protein phosphatase PP6 in mitotic cells. Sci Signal. 2015;8(398):rs12. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aab3138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Manzella G., Schreck L.D., Breunis W.B., et al. Phenotypic profiling with a living biobank of primary rhabdomyosarcoma unravels disease heterogeneity and AKT sensitivity. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):4629. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-18388-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cheng Y., Ren X., Zhang Y., et al. eEF-2 kinase dictates cross-talk between autophagy and apoptosis induced by Akt Inhibition, thereby modulating cytotoxicity of novel Akt inhibitor MK-2206. Cancer Res. 2011;71(7):2654–2663. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ohkura N., Kitagawa Y., Sakaguchi S. Development and maintenance of regulatory T cells. Immunity. 2013;38(3):414–423. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.He X.J., Chen T., Zhu J.K. Regulation and function of DNA methylation in plants and animals. Cell Res. 2011;21(3):442–465. doi: 10.1038/cr.2011.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sacco F., Perfetto L., Castagnoli L., Cesareni G. The human phosphatase interactome: an intricate family portrait. FEBS Lett. 2012;586(17):2732–2739. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hunter T. Protein kinases and phosphatases: the yin and yang of protein phosphorylation and signaling. Cell. 1995;80(2):225–236. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90405-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yan S., Xu Z., Lou F., et al. NF-κB-induced microRNA-31 promotes epidermal hyperplasia by repressing protein phosphatase 6 in psoriasis. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7652. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sauer S., Bruno L., Hertweck A., et al. T cell receptor signaling controls Foxp3 expression via PI3K, Akt, and mTOR. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(22):7797–7802. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800928105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brognard J., Sierecki E., Gao T., Newton A.C. PHLPP and a second isoform, PHLPP2, differentially attenuate the amplitude of Akt signaling by regulating distinct Akt isoforms. Mol Cell. 2007;25(6):917–931. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Patterson S.J., Han J.M., Garcia R., et al. Cutting edge: PHLPP regulates the development, function, and molecular signaling pathways of regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2011;186(10):5533–5537. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang X., He X., Li Q., et al. PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling mediates valproic acid-induced neuronal differentiation of neural stem cells through epigenetic modifications. Stem Cell Reports. 2017;8(5):1256–1269. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2017.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]