Abstract

V3 enzyme immunoassays have been shown to discriminate effectively between human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) subtypes. The aim of this study was to investigate the feasibility of V3 serotyping for HIV-2 infection. We serotyped 29 sera with three peptides, corresponding to the V3 loop of subtypes A, B, and D of HIV-2. Sera were collected from HIV-2-infected patients, whose infecting strains were sequenced and subjected to phylogenetic analysis. Our results indicate that HIV-2 serotyping using V3 peptides is not relevant. V3 serotyping data were not consistent with genotyping results. The V3-A and V3-D peptides displayed poor discrimination, and the V3-B peptide was not representative of circulating viruses. Comparison of amino acid sequences and serotype reactivities demonstrated the importance of positions 309 and 314, located on either side of the tip of the V3 loop, in antibody binding.

Human immunodeficiency virus type 2 (HIV-2) is the second retrovirus causing immunodeficiency in humans. Its existence was first suspected in Senegalese individuals in 1985 (3), and it was isolated from a West African patient suffering from AIDS in 1986 (9). The HIV-2 epidemic, unlike that of HIV-1, has remained largely restricted to West Africa (8, 13, 23, 25, 29, 31, 36), although some cases in Central Africa (12, 16, 19) and East Africa (17) have been reported. This virus has been detected in Europe (14, 15; I. Loussert-Ajaka, D. Descamps, F. Simon, F. Brun-Vézinet, M. Ekwalanga, and S. Saragosti, Letter, Lancet 346:912–913, 1995), reflecting historical links with the areas of endemicity, and in a limited number of cases in Argentina and the United States (18, 24). HIV-2 has also been found in India (26). Analysis of the genetic divergence of HIV-2 isolates has led to their classification into seven phylogenetic subtypes, designated A to G (8, 13, 37). Unlike HIV-1, for which data on strain diversity and molecular epidemiology are abundant, little is known about the variation and geographic distribution of HIV-2 subtypes. Only subtypes A and B appear to be prevalent. Subtype A, which contains most of the HIV-2 strains characterized to date, has been identified in almost all western African countries (25, 31, 36). Subtype B viruses seem to be much more limited geographically and have been reported mainly in Côte d'Ivoire and Ghana (5, 13, 27, 33). Subtypes C, D, E, and F are represented only by partial sequences of single viral genomes; they have been identified in Liberia (subtype C and D) (13) and Sierra Leone (subtype E and F) (8, 13). The new subtype, G, is represented by the full-length genomic sequence of a strain collected in Côte d'Ivoire from an asymptomatic blood donor (37).

In the last few years, extensive molecular epidemiological surveys have been performed to study the global distribution of HIV-1 subtypes. Such molecular epidemiological studies are also needed to monitor dynamics and changes in the distribution of HIV-2 subtypes in countries where the virus is endemic and emerging subtypes outside West Africa. It has been suggested that subtype A may be more pathogenic than subtype B (13), and it may therefore be necessary to discriminate between these subtypes. HIV-2 subtyping is currently conducted by sequencing genomic fragments amplified by PCR. Although this reference method makes direct subtype classification possible, it is time-consuming, expensive, and difficult to generalize and does not permit the rapid analysis of numerous samples. Only 14 HIV-2 full genome sequences and 60 partial or complete env sequences were available at the end of 1997 (http://hiv-web.lanl.gov/HTML/alignments.html), most belonging to subtype A (51 of the 60 env sequences). Our aim was to study the feasibility of V3 serotyping for HIV-2. This is a rapid and simple laboratory method already widely used in HIV-1 subtyping (1, 2, 6, 32, 35). Indeed, V3 enzyme immunoassays, particularly a subtype-specific enzyme immunoassay (SSEIA) involving blocking with an excess of peptide in the liquid phase developed in our laboratory (2), have been shown to be very effective and useful for discriminating between a limited number of serotypes. The correlation between genotyping and V3 serotyping is well defined (7), and its limitations have been characterized (28).

In this present study, we carried out V3 serotyping for 29 serum samples by SSEIA and compared the results obtained with data generated by sequencing and phylogenetic analysis.

Serum samples were collected at Bichat Hospital (Paris, France). Geographical origin was known for 28 patients: West African countries (total, 22; Burkina Faso, n = 1; Cape Verde Islands, n = 5; Côte d'Ivoire, n = 6; Ghana, n = 1; Guinea-Bissau, n = 1; Mali, n = 4; Senegal, n = 4), Morocco (n = 1), France (n = 4), and the French West Indies (n = 1). Each sample was genotyped by sequencing and phylogenetic analysis of the env gene as follows. DNA was extracted from fresh peripheral blood mononuclear cells with phenol chloroform, precipitated with ethanol, and quantified spectrophotometrically. HIV-2 DNA was amplified by nested PCR after long PCR as previously described (11). The PCR products were purified using a gel extraction kit (Qiagen, Chatsworth, Calif.). Sense and antisense DNA templates were then used as a matrix for the corresponding primers in a dye terminator kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.). Sequencing reactions were performed on an automated DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems 373A). Multiple alignments of DNA sequences were generated using the CLUSTAL W program (34). Gaps were eliminated from the sequences and a pairwise matrix was generated with the DNADIST program (PHYLIP package, version 3.5c; Department of Genetics, University of Washington, Seattle). Tree topology was inferred by neighbor joining with the Kimura two-parameter distance matrix (PHYLIP) and a transition-transversion ratio of 2. Bootstrap analysis was performed with the SEQBOOT, DNADIST, NEIGHBOR, and CONSENS programs. For tree construction, we also included the env sequences of the following reference isolates: HIV-2 subtype A (ROD, NIHZ, ST, ISY, and BEN), subtype B (UCI, EHOA, D205, and C2238), and subtype D (DF0784) and simian immunodeficiency virus strains MNE, MM251, STM, STAK1, and SMMPBJ from the Los Alamos National Laboratory database (20). There were 21 genotype A samples and 8 genotype B samples (10). V3 sequences were available for all 29 samples.

Serum samples were serotyped with HIV-2 SSEIA using three 29-amino-acid peptides corresponding to the V3 consensus sequences of the gp125 of the two prevalent subtypes of HIV-2, A and B, and subtype D (21, 22). We included subtype D because the strains of simian immunodeficiency virus that infect sooty mangabeys belong to this clade (13). Subtypes C, E, F, and G were not included, because consensus sequences for the gp125 and Env regions of subtypes C and E, respectively, were not available and subtypes F and G had not yet been identified when we initiated the study.

The peptides were produced as previously described (28), and their sequences were as follows: V3-A, NKTVVPITLMSGLVFHSQPINKRPRQAWC; V3-B, NKTVVPIRTVSGLLFHSQPINKRPRQAWC; and V3-D, NKTVLPVTIMSGLVFHSQPINDRPKQAWC.

The HIV-2 SSEIA was performed as previously described for HIV-1 (2). Briefly, the wells of microtiter plates were coated with an equimolar mixture of the three V3 peptides (0.8 μg/ml each, 100 μl per well). Each serum sample was tested in five wells in the presence of various blocking solutions. We first added 10 μl of a 100-μg/ml solution of V3 peptide corresponding to the A, B, or D subtype to wells 1 to 3, respectively. We added 10 μl of a 100-μg/ml solution of an equimolar mixture of the three peptides (theoretically 100% blocking) to well 4 and 10 μl of serum dilution buffer (theoretically 0% blocking) to well 5. We added 100 μl microliters of diluted serum (1:100) to each well and incubated the plates for 30 min at room temperature. Peroxidase-conjugated anti-human immunoglobulin G (1:5,000, 100 μl; TAGO, Burlingame, Calif.) was added, and the plates were incubated for 30 min at room temperature. The reaction product was revealed by adding 100 μl of substrate and incubating for 15 min at room temperature. Optical density (OD) at 492 nm was determined. Reactivity was calculated as the percent inhibition of binding induced by each of the three peptides for every serum sample, using the following formula: [(OD without blocking − OD in presence of peptide x) (OD without blocking − OD in presence of all three peptides)] × 100. The HIV-2 SSEIA therefore indicates immunodominant subtype reactivity as the peptide with the strongest blocking and gives a serological profile, defined by the three values for inhibition (percent inhibition by peptide A, percent inhibition by peptide B, percent inhibition by peptide D).

Two (one of genotype A and one of genotype B) of the 29 samples (6.9%) did not react and were considered nontypeable. Twelve of the 20 reactive HIV-2 genotype A samples were identified as serotype A (60%), but all were strongly cross-reactive (over 90% inhibition) with peptide D (Table 1). Three genotype A samples reacted predominantly with peptide D but had strong cross-reactivity with peptide A, whereas the five remaining genotype A samples were equally reactive with peptides A and D (25%). Only one of the seven reactive genotype B samples was correctly identified, the other six being identified as serotype D. We further analyzed this serotype/genotype misidentification using the amino acid sequences of the V3 region, which were available for the 27 reactive samples. Samples were grouped according to the SSEIA results, and the V3 sequences of the corresponding strains were aligned to enable us to correlate amino acid sequences with serological reactivity (Table 2). Twenty-four of the 26 samples reacting with peptide A or D or both had TXM at positions 308 to 310, characteristic of peptides V3-A and V3-D. None of our strains had the RTV motif characteristic of peptide V3-B. This suggests that positions 308 to 310 could be considered essential for serotype reactivity and may account for the lack of reactivity of peptide V3-B (Table 2). Position 309 seems to be particularly involved: a valine or isoleucine residue in place of leucine at this position was associated with dominant reactivity with peptide V3-D. Position 314 may also play a role in seroreactivity. The only sample (9641) identified as serotype B and sample 96339 (from the mother of patient 9641), which cross-reacted strongly with peptide V3-B, had the leucine residue of the peptide V3-B sequence, whereas peptides A and D had a valine at this position (Table 2).

TABLE 1.

Genotype, V3 serotype, and serological profile of the 27 serum samples reactive with HIV-2 V3 peptidesa

| Sample | Genotype | V3 serotypeb | Reactivity with peptidec

|

Geographical origind | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| V3-A | V3-B | V3-D | ||||

| 96150 | A | A∗D | Complete | Low | High | CV |

| 96323 | A | A∗D | Complete | Low | High | CI |

| 97222 | A | A∗D | Complete | Low | High | M |

| 145 | A | A∗D | Complete | Low | High | S |

| 96199 | A | A∗D | Complete | Low | High | CV |

| 96202 | A | A∗D | Complete | Low | High | BF |

| 96203 | A | A∗D | Complete | Low | High | CV |

| 96205 | A | A∗D | Complete | Low | High | G |

| 96310 | A | A∗D | Complete | Low | High | S |

| 96327 | A | A∗D | Complete | Low | High | CV |

| 96329 | A | A∗D | Complete | Low | High | GB |

| 97223 | A | A∗D | Complete | Low | High | CI |

| 96206 | A | D∗A | High | Absent | Complete | F |

| 96207 | A | D∗A | High | Low | Complete | M |

| 96328 | A | D∗A | High | Absent | Complete | F |

| 95152 | A | AD | Complete | Moderate | Complete | S |

| 96144 | A | AD | Complete | Moderate | Complete | ? |

| 96325 | A | AD | Complete | Low | Complete | F |

| 96326 | A | AD | Complete | Low | Complete | M |

| 96330 | A | AD | Complete | Moderate | Complete | Mc |

| 9647 | B | D | Absent | Low | Complete | WI |

| 96200 | B | D | Moderate | Low | Complete | CI |

| 96306 | B | D | Moderate | Low | Complete | S |

| 96309 | B | D | High | Low | Complete | M |

| 97244 | B | D | Moderate | Low | Complete | F |

| 96339 | B | D | Moderate | High | Complete | CI |

| 9641 | B | B | Moderate | Complete | Low | CI |

Samples are grouped according to the genotype results determined by sequencing of the env gene and phylogenetic analysis. Subgroups are defined according to serotype results.

A∗D, dominant reactivity with peptide A and strong cross-reactivity (over 90% inhibition) with peptide D; AD, indeterminate serotype, as reactivity was identical with V3-A and V3-D.

The serological profile of each sample is shown. Complete (100%) inhibition indicates immunodominant reactivity; cross reactivities are defined as high (90 to 99%), moderate (75 to 89%), low (50 to 74%), or absent (<50%) inhibition.

BF, Burkina Faso; CI, Côte d'Ivoire; CV, Cape Verde Islands; G, Ghana; GB, Guinea-Bissau; M, Mali; Mc, Morocco; S, Senegal; F, France; WI, West French Indies; ?, unknown.

TABLE 2.

Partial amino acid sequences of the V3 loop of the 27 reactive samples, grouped according to genotype

| HIV-2 sequence or sample | Genotype | V3 serotypea | V3 loop sequence (positions 301 to 330)b |

|---|---|---|---|

| V3-A consensus | N K T V V P I T L M S G L V F H S Q P . I N K R P R Q A W C | ||

| V3-B consensus | - - - - - - - R T V - - - L - - - - - . - - - - - - - - - - | ||

| V3-D consensus | - - - - L - V - I - - - - - - - - - - . - - D - - K - - - - | ||

| 96150 | A | A∗D | - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - T - - . - - - - - - - - - - |

| 96323 | A | A∗D | - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - . - - T - - - - - - - |

| 97222 | A | A∗D | - - - - - - V - - - - - - I - - - - - . - - T - - T - - L - |

| 145 | A | A∗D | - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - . - - T - - - - - - - |

| 96199 | A | A∗D | - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - . - - Q - - - - - - - |

| 96202 | A | A∗D | - - - - - - - - - - - - A R - - - R - V L - R K - K - - - - |

| 96203 | A | A∗D | - - - - - - - - - L - - - - - - - - - - - - E - - - - - - - |

| 96205 | A | A∗D | - - - - - - - - - - - - - I - - - - - . - - - - - - - - - - |

| 96310 | A | A∗D | - - - - - - - - - - - - - I - - - - - . - - - - - - - - - - |

| 96327 | A | A∗D | - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - . - - - - - - - - - - |

| 96329 | A | A∗D | - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - . - - - - - - - - - - |

| 97223 | A | A∗D | - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - . - - R - - K - - - - |

| 96206 | A | D∗A | - - - - - - - - - - - - - M - - - - - . - - - - - - - - - - |

| 96207 | A | D∗A | - - - - - - - - - - - - - I - - - - - . - - - - - - - - - - |

| 96328 | A | D∗A | - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - . - - N - - - - - - - |

| 95152 | A | AD | - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - . - - - - - - - - - - |

| 96144 | A | AD | - - - - L - - - - - - - - - - - - - - . - - - - - - - - - - |

| 96325 | A | AD | - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - . - - - - - - - - - - |

| 96326 | A | AD | - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - . - - - - - - - - - - |

| 96330 | A | AD | - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - . - - R - - - - - - - |

| 9647 | B | D | - - - - - - - - V - - - - I - - - - - . - - N - - - - - - - |

| 96200 | B | D | - - - - - - - - V - - - I - - - - - - . - - T - - - - - - - |

| 96306 | B | D | - - - - - - - - V - - - - - - - - - - . - - E - - - - - - - |

| 96309 | B | D | - - - - A - - - I - - - - I - - - - - . - - R - - - - - - - |

| 97244 | B | D | - - - - - - - - V - - - - I - - - - - . - - - - - - - - - - |

| 96339 | B | D | - - - - K - - - I A - - - L - - - - - . - - T - - - - - - - |

| 9641 | B | B | - - - - K - - - I A - - - L - - - - - - - - T K - - - - - - |

A∗D, dominant reactivity with peptide A and strong cross-reactivity with peptide D; AD, indeterminate serotype, as reactivity was identical with V3-A and V3-D.

Residues are numbered according to the work of Björling et al. (4). The sequences of peptides V3-A, V3-B, and V3-D, corresponding to the consensus V3 loop sequences of each subtype, are those used in the SSEIA. The sequence of the V3-A peptide was used as a reference. Dots indicate insertions, and dashes indicate residue identity. Position 309, which is involved in the difference in reactivity between genotype A and B samples, is in bold, except in the cases of the V3-B consensus and sample 9641, where the amino acid at that position is not concerned by seroreativity to A or D. The residues immediately after the dots are residues 320 and 322.

The aim of this study was to determine whether V3 serotyping of HIV-2 infection was efficient and relevant. HIV-2 subtyping is currently less important than that of HIV-1 group M, which is pandemic with a heterogeneous wide distribution of many subtypes. For HIV-2, only subtypes A and B are prevalent and the epidemic is more restricted. However, efficient tools could be useful for discriminating simply and rapidly between these two subtypes, if they prove to have different biological properties (13).

We serotyped 29 sera, using three peptides, corresponding to the V3 loop of subtypes A, B, and D, based on env gene analysis. We found that serotyping using the V3 region was not relevant. This is due to the strong similarity between the V3-A and V3-D peptide sequences (Table 2). This work indicates that discordance in subtyping for B samples may be related to the amino acid sequence of the peptide, which seems to be unrepresentative of the viruses in circulation. The V3 consensus sequence of subtype B that we used was deduced from the three isolates available at the start of the study. The seven sequences available in this study suggest that the V3 sequences of subtype B viruses are actually more similar to those of subtypes A and D. Our study confirms previous conclusions reported for HIV-1: a limited number of serotypes with closely related amino acid sequences exist, and two phylogenetically different subtypes can share antigenicity due to similarity in their V3 loops (28). However, whereas it is possible to discriminate a limited number of serotypes for HIV-1, the higher level of conservation of the V3 sequences in HIV-2 isolates than in HIV-1 isolates makes this more difficult for HIV-2.

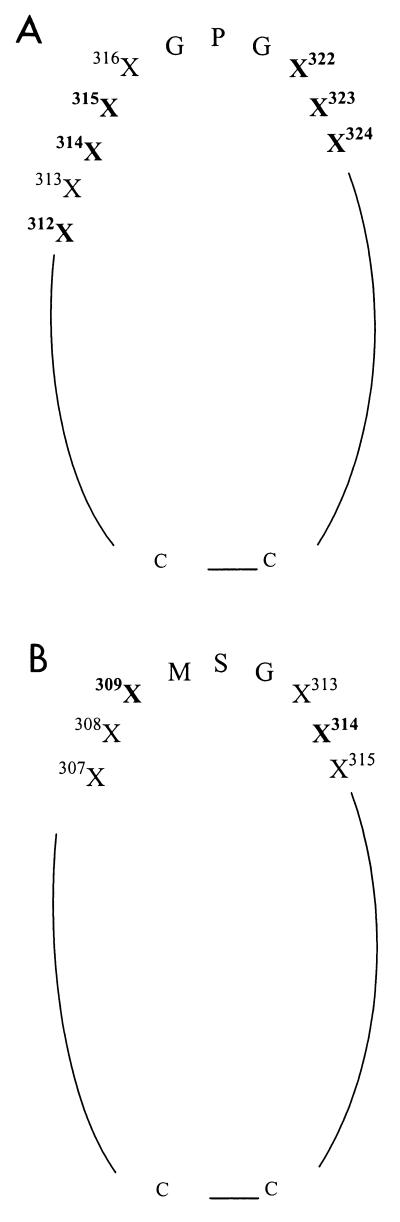

Analysis of amino acid sequences from 27 samples included in this study demonstrated the importance of positions 309 and 314 for the specificity of seroreactivity. Comparison with key amino acids specific to HIV-1 V3 subtypes showed that the residues involved in HIV-2 seroreactivity are also located on either side of the tip of the V3 loop (Fig. 1). This observation indicates that the sides of the tip of the V3 loop of both HIV-1 and HIV-2 include residues critical for antibody binding.

FIG. 1.

Simplified representation of the positions essential for subtype-specific antigenicity and seroreactivity of the V3 loops of HIV-1 (A) and HIV-2 (B). Critical positions are in bold. Residues are numbered according to the work of Ratner et al. (30) (A) and Björling et al. (4) (B). For more details of the positions critical for HIV-1 antigenicity, see reference 28.

In conclusion, this study shows that V3 serotyping is of limited value for HIV-2. This is due to the high level of similarity between the V3 sequences of the different subtypes. Other regions should be studied if the serological subtyping of HIV-2 becomes necessary.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Agence National de Recherche sur le SIDA (ANRS, Paris; France) and the European Commission. J.-C. Plantier was supported by a doctoral fellowship from Sidaction.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barin F, Couroucé A M, Pillonel J, Buzelay L the Retrovirus Study Group of the French Society of Blood Transfusion. Increasing diversity of HIV-1M serotypes in French blood donors over a 10-year period (1985–1995) AIDS. 1997;11:1503–1508. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199712000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barin F, Lahbabi Y, Buzelay L, Lejeune B, Baillou-Beaufils A, Denis F, Mathiot C, M'Boup S, Vithayasai V, Dietrich U, Goudeau A. Diversity of antibody binding to V3 peptides representing consensus sequences of HIV type 1 genotypes A to E: an approach for HIV type 1 serological subtyping. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 1996;12:1279–1289. doi: 10.1089/aid.1996.12.1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barin F, M'Boup S, Denis F, Kanki P, Allan J S, Lee T H, Essex M. Serological evidence for virus related to simian T-lymphotropic retrovirus III in residents of West Africa. Lancet. 1985;ii:1387–1389. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(85)92556-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Björling E, Broliden K, Bernardi D, Utter G, Thorstensson R, Chiodi F, Norrby E. Hyperimmune antisera against synthetic peptides representing the glycoprotein of human immunodeficiency virus type 2 can mediate neutralization and antibody-dependent cytotoxic activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:6082–6086. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.14.6082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brennan C A, Yamaguchi J, Vallari A S, Hickman R K, Devare S G. Genetic variation in human immunodeficiency virus type 2: identification of a unique variant from human plasma. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 1997;13:401–404. doi: 10.1089/aid.1997.13.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheingsong-Popov R, Williamson C, Lister S, Morris L, Van Harmelen J, Bredell H, Wood R, Sonnenberg P, van der Ryst E, Martin D, Weber J. Usefulness of HIV-1 V3 serotyping in studying the HIV-1 epidemic in South Africa. AIDS. 1998;12:949–966. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheingsong-Popov R, Lister S, Callow D, Kaleebu P, Beddows S, Weber J the WHO Network for HIV Isolation and Characterization. Serotyping of HIV type 1 infections: definition, relationship to viral genetic subtypes, and assay evaluation. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 1998;14:311–318. doi: 10.1089/aid.1998.14.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen Z, Luckay A, Sodora D L, Telfer P, Reed P, Gettie A, Kanu J M, Sadek R F, Yee J, Ho D D, Zhang L, Marx P A. Human immunodeficiency virus type 2 (HIV-2) seroprevalence and characterization of a distinct HIV-2 genetic subtype from the natural range of simian immunodeficiency virus-infected sooty mangabeys. J Virol. 1997;71:3953–3960. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.5.3953-3960.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clavel F, Guétard D, Brun-Vézinet F, Chamaret S, Rey M A, Santos-Ferreira M O, Laurent A G, Dauguet C, Katlama C, Rouzioux C, Klatzmann D, Champalimaud J L, Montagnier L. Isolation of a new human retrovirus from West African patients with AIDS. Science. 1986;233:343–346. doi: 10.1126/science.2425430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Damond F, Apetrei C, Robertson D L, Souquière S, Leprêtre A, Matheron S, Plantier J C, Brun-Vézinet F, Simon F. Variability of human immunodeficiency virus type 2 (HIV-2) infecting patients living in France. Virology. 2001;280:19–30. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Damond F, Loussert-Ajaka I, Apetrei C, Descamps D, Souquière S, Lepretre A, Matheron S, Brun-Vézinet F, Simon F. Highly sensitive method for amplification of human immunodeficiency virus type 2 DNA. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:809–811. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.3.809-811.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Delaporte E, Janssen W, Peeters M, Buve A, Dibanga G, Perret J L, Ditsambou V, Mba J R, Courbot M C, Georges A, Bourgeois A, Samb B, Henzel D, Heyndrickx L, Fransen K, van der Groen G, Larouze B. Epidemiological and molecular characteristics of HIV infection in Gabon, 1986–1994. AIDS. 1996;10:903–910. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199607000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gao F, Yue L, Robertson D L, Hill S C, Hui H, Biggar R J, Neequaye A E, Whelan T M, Ho D D, Shaw G M, Sharp P M, Hahn B H. Genetic diversity of human immunodeficiency virus type 2: evidence for distinct sequence subtypes with differences in virus biology. J Virol. 1994;68:7433–7447. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.11.7433-7447.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heredia A, Vallejo A, Soriano V, Silva A, Mansinho K, Fevereiro S, Mas A, Gutierrez M, Epstein J S, Hewlett I K. Phylogenetic analysis of HIV type 2 strains from Portugal. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 1998;14:471–473. doi: 10.1089/aid.1998.14.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heredia A, Vallejo A, Soriano V, Aguilera A, Mas A, Epstein J S, Hewlett I K. Genetic analysis of an HIV type 2 subtype B virus from a Spanish individual with AIDS. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 1997;13:899–900. doi: 10.1089/aid.1997.13.899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heredia A, Vallejo A, Soriano V, Gutierrez V, Puente S, Epstein J S, Hewlett I K. Evidence of HIV-2 infection in Equatorial Guinea (Central Africa): partial genetic analysis of a subtype B virus. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 1997;13:439–440. doi: 10.1089/aid.1997.13.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kanki P J, De Cock K M. Epidemiology and natural history of HIV-2. AIDS. 1994;8:S85–S93. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Libonatti O, Avila M, Zlatkes R, Pampuro S, Martinez Peralta L, Rud E, Wainberg M, Salomon H. First report of HIV-2 infection in Argentina. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1998;18:190–191. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199806010-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mauclère P, Loussert-Ajaka I, Damond F, Fagot P, Souquière S, Monny Lobe M, Mbopi Keou F X, Barré-Sinoussi F, Saragosti S, Brun-Vézinet F, Simon F. Serological and virological characterization of HIV-1 group O infection in Cameroon. AIDS. 1997;11:445–453. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199704000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Myers G, Korber B, Foley B, Jeang K T, Mellors J W, Wain-Hobson S. Human retroviruses and AIDS 1996: a compilation and analysis of nucleic acid and amino acid sequences. Los Alamos, N.Mex: Theoretical Biology and Biophysics Group, Los Alamos National Laboratory; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Myers G, Korber B, Hahn B H, Jeang K T, Mellors J W, McCutchan F E, Henderson L, Pavlakis G N. Human retroviruses and AIDS 1995: a compilation and analysis of nucleic acid and amino acid sequences. Los Alamos, N.Mex: Theoretical Biology and Biophysics Group, Los Alamos National Laboratory; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Myers G, Korber B, Wain-Hobson S, Jeang K T, Henderson L, Pavlakis G N. Human retroviruses and AIDS 1994: a compilation and analysis of nucleic acid and amino acid sequences. Los Alamos, N.Mex: Theoretical Biology and Biophysics Group, Los Alamos National Laboratory; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Norrgren H, Marquina S, Leitner T, Aaby P, Melbye M, Poulsen A G, Larsen O, Dias F, Escanilla D, Andersson S, Albert J, Naucler A. HIV-2 genetic variation and DNA load in asymptomatic carriers and AIDS cases in Guinea-Bissau. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1997;16:31–38. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199709010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O'Brien T R, George J R, Holmberg S D. Human immunodeficiency virus type 2 infection in the United States. JAMA. 1992;267:2775–2779. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peeters M, Janssens W, Fransen K, Brandful J, Heyndrickx L, Koffi K, Delaporte E, Piot P, Gershy-Damet G M, van der Groen G. Isolation of simian immunodeficiency viruses from two sooty mangabeys in Côte d'Ivoire: virological and genetic characterization and relationship to other HIV type 2 and SIVsm/mac strains. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 1994;10:1289–1294. doi: 10.1089/aid.1994.10.1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pfützner A, Dietrich U, von Eichel U, von Briesen H, Brede H D, Maniar J K, Rübsamen-Waigmann H. HIV-1 and HIV-2 infections in a high-risk population in Bombay, India: evidence for the spread of HIV-2 and presence of a divergent HIV-1 subtype. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1992;5:972–977. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pieniazek D, Ellenberger D, Janini L M, Ramos A C, Nkengasong J, Sassan-Morokro M, Hu D J, Coulibally I M, Ekpini E, Bandea C, Tanuri A, Greenberg A E, Wiktor S Z, Rayfield M A. Predominance of human immunodeficiency virus type 2 subtype B in Abidjan, Ivory Coast. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 1999;15:603–608. doi: 10.1089/088922299311132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Plantier J C, Damond F, Lasky M, Sankalé J L, Apetrei C, Peeters M, Buzelay L, M'Boup S, Kanki P, Delaporte E, Simon F, Barin F. V3 serotyping of HIV-1 infection: correlation with genotyping and limitations. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1999;20:432–441. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199904150-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Poulsen A G, Aaby P, Gottschau A, Kvinesdal B B, Dias F, Molbak K, Lauritzen E. HIV-2 infection in Bissau, West Africa, 1987–1989: incidence, prevalences, and routes of transmission. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1993;6:941–948. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ratner L, Haseltine W, Patarca R, Livak K J, Starcich B, Josephs S F, Doran E R, Rafalski J A, Whitehorn E A, Baumeister K, Ivanoff L, Petteway S R, Jr, Pearson M L, Lautenberger J A, Papas T S, Ghrayeb J, Chang N T, Gallo R C, Wong-Staal F R. Complete nucleotide sequence of the AIDS virus, HTLV-III. Nature. 1985;313:277–284. doi: 10.1038/313277a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sharp P M, Robertson D L, Gao F, Hahn B. Origins and diversity of human immunodeficiency viruses. AIDS. 1994;8(Suppl. 1):S27–S42. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sönnerborg A, Durdevic S, Giesecke J, Sällberg M. Dynamics of the HIV-1 subtype distribution in the Swedish HIV-1 epidemic during the period 1980 to 1993. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 1997;13:343–345. doi: 10.1089/aid.1997.13.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Takehisa J, Isei-Kwasi M, Ayisi N K, Hishida O, Miura T, Igarashi T, Brandful J, Ampofo W, Netty V B, Mensah M, Yamashita M, Ido E, Hayami M. Phylogenetic analysis of HIV type 2 in Ghana and intrasubtype recombination in HIV type 2. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 1997;13:621–623. doi: 10.1089/aid.1997.13.621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thompson J D, Higgins D G, Gibson T J. Clustal W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wasi C, Herring B, Raktham S, Vanichseni S, Mastro T D, Young N L, Rubsamen-Waigmann H, von Briesen H, Kalish M L, Luo C C, Pau C P, Baldwin A, Mullins J I, Delwart E L, Esparza J, Heyward W L, Osmanov S. Determination of HIV-1 subtypes in injecting drug users in Bangkok, Thailand, using peptide-binding enzyme immunoassay and heteroduplex mobility assay: evidence of increasing infection with HIV-1 subtype E. AIDS. 1995;9:843–849. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199508000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xiang Z, Ariyoshi K, Wilkins A, Dias F, Whittle H, Breuer J. HIV-2 pathogenicity is not related to subtype in rural Guinea Bissau. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 1997;13:501–505. doi: 10.1089/aid.1997.13.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yamaguchi J, Devare S G, Brennan C A. Identification of a new HIV-2 subtype based on phylogenetic analysis of full-length genomic sequence. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 2000;16:925–930. doi: 10.1089/08892220050042864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]