Abstract

To establish successful infection in cells, it is essential for hepatitis C virus (HCV) to overcome intracellular antiviral responses. The host cell mechanism that fights against the virus culminates in the production of interferons (IFNs), IFN-stimulated genes (ISGs) and pro-inflammatory cytokines as well as the induction of autophagy and apoptosis. HCV has developed multiple means to disrupt the host signaling pathways that lead to these antiviral responses. HCV impedes signaling pathways initiated by pattern-recognition receptors (PRRs), usurps and uses the antiviral autophagic response to enhance its replication, alters mitochondrial dynamics and metabolism to prevent cell death and attenuate IFN response, and dysregulates inflammasomal response to cause IFN resistance and immune tolerance. These effects of HCV allow HCV to successful replicate and persist in its host cells.

Keywords: hepatitis C virus, innate immune responses, RIG-I signaling, Toll-like receptors, autophagy, mitophagy, inflammasomes

Introduction

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is one of the most important human pathogens. There are approximately 58 million people worldwide that are chronically infected by HCV, with about 1.5 million new cases every year. People infected by HCV often become chronic carriers of the virus. The chronic infection by HCV may be asymptomatic. However, it can progress into severe liver diseases including cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). The development of direct acting antiviral (DAA) drugs in 2011 and their subsequent use greatly improved the therapeutic outcomes for HCV patients [1], achieving a sustained virological response (SVR) rate of >90%. DAA drugs target HCV non-structural proteins including the NS3/4A protease, NS5A, and the NS5B RNA-dependent RNA polymerase [2], all of which are essential for HCV replication. However, the high cost of these DAAs limits their availability for many patients. In contrast to DAAs, the development of HCV vaccines has encountered extreme difficulties due mainly to the high viral mutation rate, which has a frequency of approximately 10−3 base substitutions per site per year [3]. The resolution of acute HCV infection requires efficient innate and adaptive immune responses. However, HCV evades the host immune system and establishes persistent infection in approximately 75-85% of patients it infects. Many reports in the past had examined the mechanisms by which HCV interferes with host immune responses. In this article, we will focus on the interaction between HCV and intracellular antiviral responses.

Pattern-recognition receptors and HCV-induced innate immune response

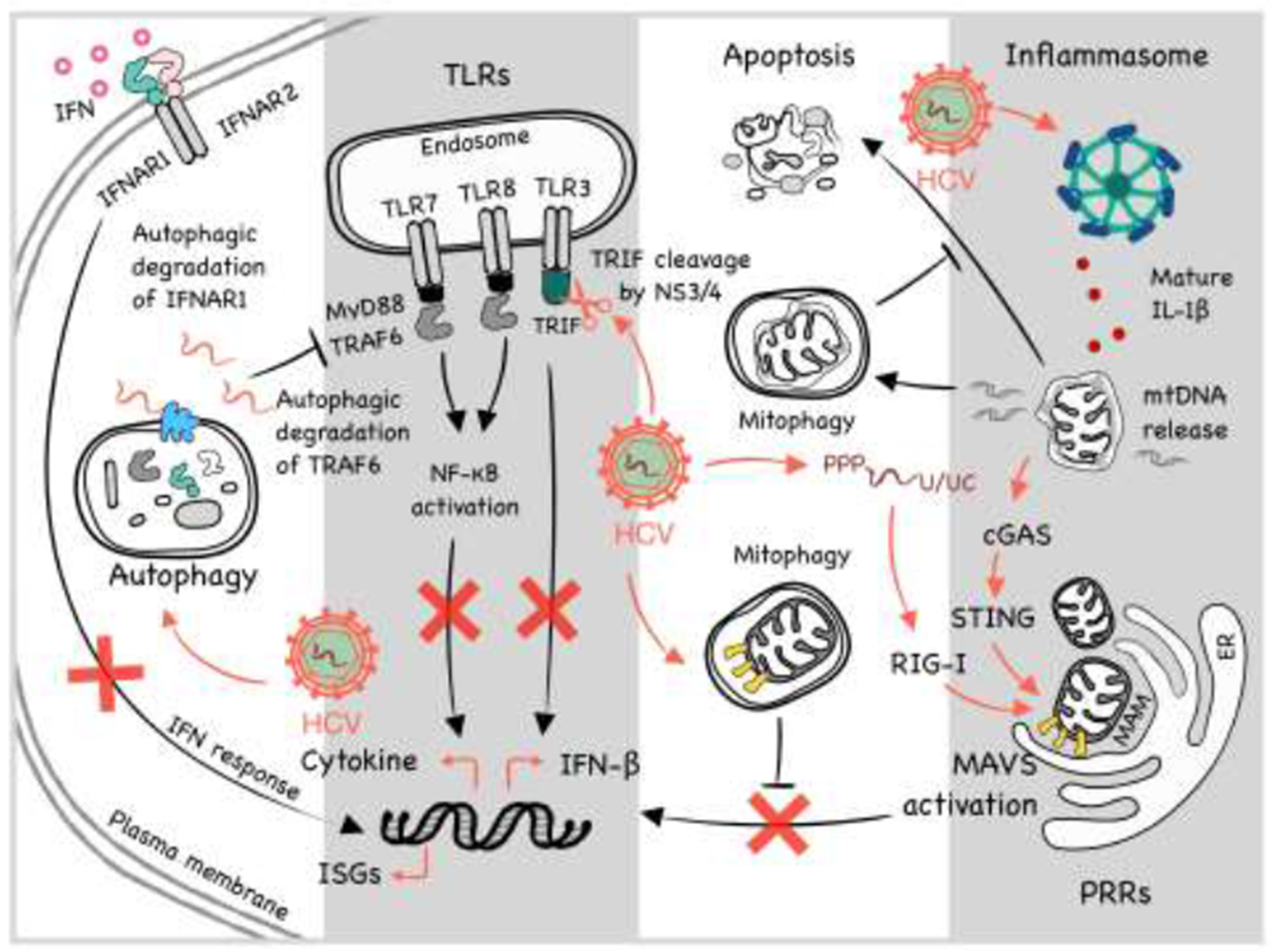

Pattern-recognition receptors (PRRs) sense non-self-molecular signatures called pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) to trigger antiviral responses. The three classes of PRRs include the retinoic acid inducible gene-I (RIG-I)-like receptors (RLRs), toll like receptors (TLRs), and nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain (NOD)-like receptors (NLRs). RLRs include RIG-I, melanoma differentiation antigen 5 (MDA5), and the laboratory of genetics and physiology 2 (LGP2) [4]. RIG-I and MDA5 recognize double-stranded RNA (dsRNA), although the specific PAMPs that they detect are different [5]. HCV PAMPs for RIG-I is the 5’-PPP double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) and the 3’ poly U/UC sequence in the genomic RNA [6] (Figure 1). The CARD domain of RIG-I interacts with and activates the mitochondrial adaptor protein MAVS (also known as IPS-1, VISA or Cardif) on the mitochondrial membrane, which then further recruits TRAF3 and TRAF6. This leads to the activation of the downstream TBK1, which then phosphorylates IRF-3 followed by the homo-dimerization and translocation of IRF-3 into the nucleus to induce the expression of the interferon (IFN)-β gene. LGP2, which lacks the CARD domain, binds to RNA and synergizes with MDA5 signaling [4], resulting in the production of IFNs.

Figure 1.

Illustration of interaction between HCV and various cellular pathways including IFN signaling, TLR signaling, apoptosis, autophagy, mitophagy and inflammasomes in cells. Please see text for details.

The HCV-infected liver produces type I and III IFNs and upregulates the expression of IFN-stimulated genes (ISGs). Type I IFN-α binds to the IFN-α receptor (IFNAR) 1 and 2. Type II IFN-γ binds to IFNGR1 and IFNGR2, and Type III IFN-λ binds to IFNLR and IL-10Rβ. Type I and III IFNs share the intracellular signaling molecules including STAT proteins. The antiviral functions of the IFNs are mediated by ISGs, which include ISG15, the GTPase myxovirus resistance 1 (Mx1), ribonuclease L (RNaseL), 2’,5’-oligoA synthase (OAS) and protein kinase RNA-activated (PKR) [7]. HCV NS3/4A, the viral serine protease complex, plays multiple roles in overcoming the antiviral effect of IFNs. NS3/4A blocks the RIG-I signaling by cleaving the adaptor protein MAVS [8]. A point mutation at cysteine-508 (Cys-508) of MAVS, which rendered MAVS resistant to cleavage by NS3/4A, restored the interferon production in cells infected by HCV or harboring an HCV subgenomic RNA replicon [9,10]. The mitochondria-associated membrane (MAM) at the endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-mitochondria contact site serves as the MAVS signaling platform (see below). In another study, NS3/4A was shown to cleave peroxisome-associated MAVS to block the RIG-I antiviral signaling from peroxisomes [11]. The localization of NS3/4A to peroxisomes was not dependent on MAVS, although the presence of MAVS was preferred [11].

While TLR1, TLR2, TLR4, TLR5 and TLR6 are expressed on the cell surface and recognize PAMPs from bacteria, fungi, or viruses, TLR3, TLR7, TLR8 and TLR9 reside in endosomes and recognize intracellular viral nucleic acids (Figure 1). TLR3 recognizes dsRNA, TLR7 and TLR8 recognizes single-stranded RNA (ssRNA), and TLR9 detects DNA with unmethylated CpG sites. Most TLRs signal through MyD88 while TLR3 signaling is mediated by Toll/interleukin-1 receptor/resistance domain-containing adaptor-inducing IFN (TRIF). TLR signaling activates nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) and IFN regulatory factors (IRFs). NF-κB induces inflammatory cytokines, and IRFs induce IFN production. The induction of IFN-β after the activation of TLR7 could suppress HCV replication [12]. Our lab also found that HCV induced the expression of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) via TLR7 and TLR8 in hepatoma cells and primary human hepatocytes [13]. This induction of TNF-α was biphasic, with the initial phase peaking at 2 hours post infection and subsiding at about 8 hours, followed by the second-phase induction at around 24 hours post-infection. TNF-α is required for type I interferon signaling in HCV-infected cells, as the silencing of either TNF-α or its receptor TNFR1 abrogated the expression of IFN-α receptor 2 (IFNAR2) and desensitized HCV-infected cells to type I IFNs. It should be noted that TNF-α had also been shown to promote HCV infection through a paracrine mechanism to disrupt the tight junctions and promote the entry of the virus into polarized hepatocytes [14]. HCV could also induce the autophagic degradation of IFN-α receptor, IFNAR1, to disrupt the IFN signaling [15].

Although host cells could produce TNF-α via TLR7/8 to support IFN signaling [13], HCV could also disrupt the TLR signaling. HCV could induce autophagic degradation of TRAF6 [16,17], which is an important adaptor molecule for TLR7/8 signaling. The HCV protease complex NS3/4A could also cleave TRIF, an important adaptor in the TLR3 signaling pathway [18]. Similarly, the HCV protein NS4B could disrupt TLR3-mediated interferon signaling by inducing the degradation of TRIF via caspase-8 [19]. NS5A could also bind to MyD88 and inhibit TLR signaling [20]. In 293T cells, NS3/4A bound to TBK1 and interfered with its association with IRF-3 [21].

Protein kinase R (PKR), a dsRNA-activated kinase, is an antiviral protein induced by IFNs. Viral infections and dsRNA can also activate PKR, which will then phosphorylate and inactivate eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 (eIF2) α, a protein factor required for the cap-dependent translation of mRNAs. Although HCV E2 and NS5A by direct binding were implicated in the inhibition of PKR [22,23], others found that HCV infection or the expression of NS5B alone activated PKR and eIF2α phosphorylation, resulting in the suppression of expression of IFNs, ISGs, and MHC class I [24–27]. Meanwhile, the translation of HCV RNA genome was not affected, as it is cap-independent and mediated by the Internal Ribosome Entry Site (IRES) located in the 5’ untranslated region (UTR) of the genome.

Autophagy and HCV-induced innate immune response

Autophagy is a catabolic process by which damaged organelles and protein aggregates are removed. This process involves the formation of a double-membrane vesicle termed autophagosomes, which sequester part of the cytoplasm. Autophagosomes mature by fusing with lysosomes. The cargos of autophagosomes are then digested by lysosomal enzymes for recycling. Autophagy is also used by cells to remove intracellular microbial pathogens in a process known as xenophagy. The specific removal of viruses by autophagy is termed virophagy [28]. HCV infection induces autophagy [17,29]. However, it was able to subvert this intracellular antiviral response and use it to support its replication. HCV-induced autophagy is dependent on its induced endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress and the unfolded protein response (UPR), which is triggered by three different ER stress sensors known as the activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6), the inositol-requiring enzyme 1 (IRE1), and the double-stranded RNA-activated protein kinase-like ER kinase (PERK) [17]. The silencing of ATF6, IRE1 or PERK to disrupt UPR or the silencing of autophagy-related proteins Atg5, Atg7, and Atg12 suppressed the replication of HCV [17,30–32]. HCV uses autophagy to benefit its replication in several ways. First, HCV utilizes the autophagic membranes as the sites for its RNA replication [17,33] (Figure 1). Second, HCV delays the maturation of autophagosomes early in infection to maximize its RNA replication. Third, HCV uses autophagic membranes to facilitate the interaction between its E2 envelope protein and apolipoprotein E (ApoE) for the production of infectious HCV particles [34]. Fourth, autophagy regulates type I interferon response (Reviewed in [35]), and the disruption of the UPR-autophagy pathway by silencing UPR- or autophagy-related genes inhibited HCV replication with a concurrent increase in ISG expression [30]. Finally, HCV-induced autophagy also impedes the innate immune response by stimulating autophagic degradation of TRAF6, an important signal transducer that activates NF-κB and the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines [16,17].

Mitophagy and HCV-induced innate immune response

Mitochondria play an important role in the control of viral infections. They produce reactive oxygen species (ROS), which was shown to suppress HCV replication [36,37], and trigger apoptosis, which eliminates HCV-infected cells [38]. A low Ca2+ level in the mitochondrial matrix is needed to maintain the activity of matrix dehydrogenases and oxidative phosphorylation for the production of ATP, and Ca2+ overload can lead to mitochondrial fragmentation, disruption of ATP synthesis, and apoptosis [39,40]. HCV causes Ca2+ overload inside the mitochondria, which is followed by an enhanced production of ROS and the formation of mitochondrial permeability transition pore (MPTP), leading to apoptosis [38].

HCV promotes mitochondrial fission via upregulation of dynamin-related protein (Drp1) and the Drp1 receptor mitochondrial fission factor (Mff) [41]. Fragmented and dysfunctional mitochondria are removed by mitophagy, a mitochondria-selective autophagy, which is also induced by HCV [41] (Figure 1). Mitophagy is initiated by the stabilization of PINK1, a protein kinase, on the outer mitochondrial membrane and the recruitment of the E3 ubiquitin ligase Parkin by PINK1. Parkin ubiquitinates outer mitochondrial membrane proteins to trigger mitophagy. The silencing of PINK1 or Parkin decreases HCV replication, indicating a positive role of mitophagy in HCV replication [42]. The role of mitophagy in HCV replication was further supported by the observation that the inhibition of mitochondrial fission and mitophagy by Drp1 silencing suppressed HCV secretion with a concomitant increase in innate immune response and apoptosis [41].

MAM is a distinct membrane compartment that links mitochondria to the ER. The HCV NS3/4A protease complex targets MAVS at this synapse, not on mitochondria, to disrupt the RIG-I signaling [43]. Pila-Castellanos et al. recently demonstrated that the infection by influenza virus induced mitochondrial fusion, which was beneficial for the viral replication [44]. The authors argued that mitochondrial fusion resulted in the loss of MAMs where MAVS relayed the RIG-I signaling, and failure in maintaining MAMs following the fusion compromised innate immunity. With the use of Mito-C, a novel pro-fission compound, they were able to restore MAMs, increase IFN production, and enhance viral clearance [44]. Similarly, the silencing of mitofusin 2 (MFN2), which mediates mitochondrial fusion [45], enhanced the IFN-β promoter activity up to 24 hours post infection and reduced the permissiveness of cells to HCV infection [43].

Inflammasomes, HCV-induced innate immune response and IFN resistance

Inflammasome is a multiprotein complex composed of a NOD-like receptor (NLRs) such as NLRP3, the adaptor protein apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a CARD (ASC), and the effector protease caspase-1. PAMPs, toxins, environmental irritants, and damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) can activate inflammasomes [46]. The assembly of inflammasomes leads to the activation of caspase 1, which then cleaves and activates IL-1β and IL-18 for their release from cells, and gasdermin D (GSDMD) to induce pyroptosis [46,47]. In response to HCV infection, the NLRP3 inflammasome is activated in hepatocytes and macrophages to induce the release of IL-1β [48,49]. In chronic HCV patients, the IL-1β level is elevated [50]. Further analysis indicated that Kupffer cells were the major source of IL-1β, and HCV could enter macrophages to trigger TLR7 signaling to activate inflammasomes and the release of IL-1β [50]. The HCV core protein was necessary and sufficient for IL-1β production from macrophages, and this process required Ca2+ mobilization and phospholipase C activation [50,51]. Interestingly, HCV-infected cells displayed apoptosis as well as pyroptosis, the caspase-1/GSDMD-mediated cell death [52]. Daussy et al. examined the role of inflammasome components on the HCV-induced Golgi fragmentation [49], typically found in apoptotic cells [53]. They found NLRP3 silencing inhibited the HCV-mediated Golgi fragmentation while ASC silencing triggered Golgi fragmentation even in the surrounding non-infected cells [49]. Inefficient pyroptosis possibly led to apoptosis of infected cells.

Type I IFNs could repress the NLRP1- and NLRP3-dependent IL-1β production via IL-10 production [54]. Aarreberg et al. showed that IL-1β induced the release of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) into the cytoplasm, which is then detected by cyclic GMP-AMP synthase (cGAS), a cytosolic DNA senser (Figure 1). Subsequent generation of the second messenger cyclic GMP-AMP (cGAMP) led to STING activation followed by the activation of IRF-3 and NF-κB, which mediated the production of IFNs and other cytokines [55]. Thus, the ongoing interplay between IL-1β and IFN in the microenvironment of HCV-infected cells may contribute to an extended inflammation state, immune tolerance, IFN resistance and the development of liver cirrhosis and HCC [56,57]. In addition, the expression of HCV proteins, lipid accumulation, ROS, ER stress and other organelle stresses may exacerbate the inflammatory response induced by HCV. Dysfunctional lipid metabolism associated with HCV infection leads to steatosis and detrimental liver damages [58]. The interaction between HCV NS5A and the α and β subunits of the mitochondrial trifunctional protein (MTP), which catalyzes the last 3 steps of mitochondrial lipid β-oxidation, was shown to be associated with the reduction of lipid β-oxidation and the suppression of MTP expression [59]. This depletion of MTP reduced the responsiveness of HCV-infected cells to IFN-α [59]. HCV core had also been shown to increase lipid accumulation and activate the NLRP3 inflammasome [51,60,61].

Conclusion

An effective host innate immune response plays a critical role in the clearance of viral infections. During the past decades, studies provided mechanistic insights on how HCV evades the host innate immune response to establish chronic infection in patients. Cleavage of TRIF and MAVS by the HCV NS3/4A protease complex interferes with TLR3 and RIG-I signaling pathways, respectively, hindering the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and IFNs (Figure 1). Since these cytokines and IFNs are important antiviral factors, the suppression of their expression is critical for HCV to persist inside its host cell. In addition, autophagy, which is supposed to control viral infection, is usurped and used by HCV to promote its replication. Similarly, mitophagy removes dysfunctional mitochondria, thereby preventing premature apoptotic cell death and promote HCV persistence. Mitochondrial fusion-induced loss of MAMs and its associated MAVS is yet another way to suppress the RIG-I-dependent induction of IFNs.

HCV can induce inflammasomes for the production of IL-1β, and Kupffer cells appear to be the major source of IL-1β in HCV patients. IL-1β can induce the expression of IFNs, which in turn can inhibit the formation of inflammasomes to repress the production of IL-1β. The prolonged interplay between IL-β and IFN can lead to chronic liver inflammation and severe liver diseases as well as IFN resistance. HCV can also perturb mitochondrial metabolism to desensitize HCV-infected cells to IFN-α. These activities of HCV provide an explanation to why most patients infected by HCV failed to clear this viral infection and ultimately develop severe liver diseases including steatosis, cirrhosis and HCC, and why most of HCV patients are not responsive to IFN therapies.

Highlights.

HCV disrupts signaling pathways initiated by pattern recognition receptors.

HCV subverts and uses the antiviral autophagic response to support its replication.

HCV perturbs mitochondrial dynamics to suppress apoptosis and interferon response.

HCV dysregulates inflammasomal response to cause interferon resistance.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health [grant numbers DK094652].

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of Interest:

None.

References and recommended reading

Papers of particular interest, published within the period of review, have been highlighted as:

• of special interest

•• of outstanding interest

- 1.Gotte M, Feld JJ: Direct-acting antiviral agents for hepatitis C: structural and mechanistic insights. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016, 13:338–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Majumdar A, Kitson MT, Roberts SK: Systematic review: current concepts and challenges for the direct-acting antiviral era in hepatitis C cirrhosis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Major ME, Mihalik K, Fernandez J, Seidman J, Kleiner D, Kolykhalov AA, Rice CM, Feinstone SM: Long-term follow-up of chimpanzees inoculated with the first infectious clone for hepatitis C virus. J Virol 1999, 73:3317–3325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- • 4.Sung PS, Shin EC: Interferon Response in Hepatitis C Virus-Infected Hepatocytes: Issues to Consider in the Era of Direct-Acting Antivirals. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This article provides an updated review of recent studies on type I and type III IFNs signaling in HCV-infected hepatocytes and the impact of direct-acting antivirals on IFN responses to HCV infection.

- 5.Stetson DB, Medzhitov R: Type I interferons in host defense. Immunity 2006, 25:373–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saito T, Owen DM, Jiang F, Marcotrigiano J, Gale M Jr.: Innate immunity induced by composition-dependent RIG-I recognition of hepatitis C virus RNA. Nature 2008, 454:523–527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sadler AJ, Williams BR: Interferon-inducible antiviral effectors. Nat Rev Immunol 2008, 8:559–568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Foy E, Li K, Sumpter R Jr., Loo YM, Johnson CL, Wang C, Fish PM, Yoneyama M, Fujita T, Lemon SM, et al. : Control of antiviral defenses through hepatitis C virus disruption of retinoic acid-inducible gene-I signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2005, 102:2986–2991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li XD, Sun L, Seth RB, Pineda G, Chen ZJ: Hepatitis C virus protease NS3/4A cleaves mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein off the mitochondria to evade innate immunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2005, 102:17717–17722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cao X, Ding Q, Lu J, Tao W, Huang B, Zhao Y, Niu J, Liu YJ, Zhong J: MDA5 plays a critical role in interferon response during hepatitis C virus infection. J Hepatol 2015, 62:771–778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferreira AR, Magalhaes AC, Camoes F, Gouveia A, Vieira M, Kagan JC, Ribeiro D: Hepatitis C virus NS3-4A inhibits the peroxisomal MAVS-dependent antiviral signalling response. J Cell Mol Med 2016, 20:750–757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee J, Wu CC, Lee KJ, Chuang TH, Katakura K, Liu YT, Chan M, Tawatao R, Chung M, Shen C, et al. : Activation of anti-hepatitis C virus responses via Toll-like receptor 7. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2006, 103:1828–1833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee J, Tian Y, Chan ST, Kim JY, Cho C, Ou JH: TNF-alpha Induced by Hepatitis C Virus via TLR7 and TLR8 in Hepatocytes Supports Interferon Signaling via an Autocrine Mechanism. PLoS Pathog 2015, 11:e1004937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fletcher NF, Sutaria R, Jo J, Barnes A, Blahova M, Meredith LW, Cosset FL, Curbishley SM, Adams DH, Bertoletti A, et al. : Activated macrophages promote hepatitis C virus entry in a tumor necrosis factor-dependent manner. Hepatology 2014, 59:1320–1330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chandra PK, Bao L, Song K, Aboulnasr FM, Baker DP, Shores N, Wimley WC, Liu S, Hagedorn CH, Fuchs SY, et al. : HCV infection selectively impairs type I but not type III IFN signaling. Am J Pathol 2014, 184:214–229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chan ST, Lee J, Narula M, Ou JJ: Suppression of Host Innate Immune Response by Hepatitis C Virus via Induction of Autophagic Degradation of TRAF6. J Virol 2016, 90:10928–10935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sir D, Chen WL, Choi J, Wakita T, Yen TS, Ou JH: Induction of incomplete autophagic response by hepatitis C virus via the unfolded protein response. Hepatology 2008, 48:1054–1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li K, Foy E, Ferreon JC, Nakamura M, Ferreon AC, Ikeda M, Ray SC, Gale M Jr., Lemon SM: Immune evasion by hepatitis C virus NS3/4A protease-mediated cleavage of the Toll-like receptor 3 adaptor protein TRIF. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2005, 102:2992–2997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- • 19.Liang Y, Cao X, Ding Q, Zhao Y, He Z, Zhong J: Hepatitis C virus NS4B induces the degradation of TRIF to inhibit TLR3-mediated interferon signaling pathway. PLoS Pathog 2018, 14:e1007075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This article demonstrates that HCV NS4B could activate caspase-8 to downregulate TRIF to suppress the TLR3 signaling.

- 20.Bowie AG, Unterholzner L: Viral evasion and subversion of pattern-recognition receptor signalling. Nat Rev Immunol 2008, 8:911–922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Otsuka M, Kato N, Moriyama M, Taniguchi H, Wang Y, Dharel N, Kawabe T, Omata M: Interaction between the HCV NS3 protein and the host TBK1 protein leads to inhibition of cellular antiviral responses. Hepatology 2005, 41:1004–1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gale MJ Jr., Korth MJ, Tang NM, Tan SL, Hopkins DA, Dever TE, Polyak SJ, Gretch DR, Katze MG: Evidence that hepatitis C virus resistance to interferon is mediated through repression of the PKR protein kinase by the nonstructural 5A protein. Virology 1997, 230:217–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taylor DR, Shi ST, Romano PR, Barber GN, Lai MM: Inhibition of the interferon-inducible protein kinase PKR by HCV E2 protein. Science 1999, 285:107–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garaigorta U, Chisari FV: Hepatitis C virus blocks interferon effector function by inducing protein kinase R phosphorylation. Cell Host Microbe 2009, 6:513–522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arnaud N, Dabo S, Maillard P, Budkowska A, Kalliampakou KI, Mavromara P, Garcin D, Hugon J, Gatignol A, Akazawa D, et al. : Hepatitis C virus controls interferon production through PKR activation. PLoS One 2010, 5:e10575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kang W, Sung PS, Park SH, Yoon S, Chang DY, Kim S, Han KH, Kim JK, Rehermann B, Chwae YJ, et al. : Hepatitis C virus attenuates interferon-induced major histocompatibility complex class I expression and decreases CD8+ T cell effector functions. Gastroenterology 2014, 146:1351–1360 e1351–1354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- • 27.Suzuki R, Matsuda M, Shimoike T, Watashi K, Aizaki H, Kato T, Suzuki T, Muramatsu M, Wakita T: Activation of protein kinase R by hepatitis C virus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. Virology 2019, 529:226–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This report showed that HCV NS5B could bind to and activate PKR to suppress the expression of MHC class I.

- 28.Sumpter R Jr., Sirasanagandla S, Fernandez AF, Wei Y, Dong X, Franco L, Zou Z, Marchal C, Lee MY, Clapp DW, et al. : Fanconi Anemia Proteins Function in Mitophagy and Immunity. Cell 2016, 165:867–881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ait-Goughoulte M, Kanda T, Meyer K, Ryerse JS, Ray RB, Ray R: Hepatitis C virus genotype 1a growth and induction of autophagy. J Virol 2008, 82:2241–2249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ke PY, Chen SS: Activation of the unfolded protein response and autophagy after hepatitis C virus infection suppresses innate antiviral immunity in vitro. J Clin Invest 2011, 121:37–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang J, Kang R, Huang H, Xi X, Wang B, Wang J, Zhao Z: Hepatitis C virus core protein activates autophagy through EIF2AK3 and ATF6 UPR pathway-mediated MAP1LC3B and ATG12 expression. Autophagy 2014, 10:766–784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fahmy AM, Labonte P: The autophagy elongation complex (ATG5-12/16L1) positively regulates HCV replication and is required for wild-type membranous web formation. Sci Rep 2017, 7:40351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sir D, Kuo CF, Tian Y, Liu HM, Huang EJ, Jung JU, Machida K, Ou JH: Replication of hepatitis C virus RNA on autophagosomal membranes. J Biol Chem 2012, 287:18036–18043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim JY, Ou JJ: Regulation of Apolipoprotein E Trafficking by Hepatitis C Virus-Induced Autophagy. J Virol 2018, 92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tian Y, Wang ML, Zhao J: Crosstalk between Autophagy and Type I Interferon Responses in Innate Antiviral Immunity. Viruses 2019, 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Choi J, Lee KJ, Zheng Y, Yamaga AK, Lai MM, Ou JH: Reactive oxygen species suppress hepatitis C virus RNA replication in human hepatoma cells. Hepatology 2004, 39:81–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Choi J, Ou JH: Mechanisms of liver injury. III. Oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of hepatitis C virus. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2006, 290:G847–851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Scrima R, Piccoli C, Moradpour D, Capitanio N: Targeting Endoplasmic Reticulum and/or Mitochondrial Ca(2+) Fluxes as Therapeutic Strategy for HCV Infection. Front Chem 2018, 6:73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Strubbe-Rivera JO, Chen J, West BA, Parent KN, Wei GW, Bazil JN: Modeling the Effects of Calcium Overload on Mitochondrial Ultrastructural Remodeling. Appl Sci (Basel) 2021, 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Krols M, Bultynck G, Janssens S: ER-Mitochondria contact sites: A new regulator of cellular calcium flux comes into play. J Cell Biol 2016, 214:367–370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim SJ, Syed GH, Khan M, Chiu WW, Sohail MA, Gish RG, Siddiqui A: Hepatitis C virus triggers mitochondrial fission and attenuates apoptosis to promote viral persistence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014, 111:6413–6418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kim SJ, Syed GH, Siddiqui A: Hepatitis C virus induces the mitochondrial translocation of Parkin and subsequent mitophagy. PLoS Pathog 2013, 9:e1003285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Horner SM, Liu HM, Park HS, Briley J, Gale M Jr.: Mitochondrial-associated endoplasmic reticulum membranes (MAM) form innate immune synapses and are targeted by hepatitis C virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011, 108:14590–14595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- •• 44.Pila-Castellanos I, Molino D, McKellar J, Lines L, Da Graca J, Tauziet M, Chanteloup L, Mikaelian I, Meyniel-Schicklin L, Codogno P, et al. : Mitochondrial morphodynamics alteration induced by influenza virus infection as a new antiviral strategy. PLoS Pathog 2021, 17:e1009340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This report demonstrated that the alteration of mitochondrial dynamics by influenza virus was associated with the RIG-I immune signaling complex and affected its antiviral activity.

- 45.Schrepfer E, Scorrano L: Mitofusins, from Mitochondria to Metabolism. Mol Cell 2016, 61:683–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wu X, Dong L, Lin X, Li J: Relevance of the NLRP3 Inflammasome in the Pathogenesis of Chronic Liver Disease. Front Immunol 2017, 8:1728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yu P, Zhang X, Liu N, Tang L, Peng C, Chen X: Pyroptosis: mechanisms and diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2021, 6:128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen W, Xu Y, Li H, Tao W, Xiang Y, Huang B, Niu J, Zhong J, Meng G: HCV genomic RNA activates the NLRP3 inflammasome in human myeloid cells. PLoS One 2014, 9:e84953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- •• 49.Daussy CF, Monard SC, Guy C, Munoz-Gonzalez S, Chazal M, Anthonsen MW, Jouvenet N, Henry T, Dreux M, Meurs EF, et al. : The Inflammasome Components NLRP3 and ASC Act in Concert with IRGM To Rearrange the Golgi Apparatus during Hepatitis C Virus Infection. J Virol 2021, 95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This report demonstrated that the inflammasome component ASC resides and interacts with IRGM at the Golgi. Upon HCV infection, ASC dissociates from IRGM and the Golgi to cause Golgi fragmentation.

- 50.Negash AA, Ramos HJ, Crochet N, Lau DT, Doehle B, Papic N, Delker DA, Jo J, Bertoletti A, Hagedorn CH, et al. : IL-1beta production through the NLRP3 inflammasome by hepatic macrophages links hepatitis C virus infection with liver inflammation and disease. PLoS Pathog 2013, 9:e1003330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- • 51.Negash AA, Olson RM, Griffin S, Gale M Jr.: Modulation of calcium signaling pathway by hepatitis C virus core protein stimulates NLRP3 inflammasome activation. PLoS Pathog 2019, 15:e1007593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This report demonstrated that the HCV core protein could mobilize the calcium signaling pathway in macrophages to activate NLRP3 inflammasomes for the production of IL-1β. This mobilization of calcium signaling is dependent on phospholipase C.

- 52.Kofahi HM, Taylor NG, Hirasawa K, Grant MD, Russell RS: Hepatitis C Virus Infection of Cultured Human Hepatoma Cells Causes Apoptosis and Pyroptosis in Both Infected and Bystander Cells. Sci Rep 2016, 6:37433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bottone MG, Santin G, Aredia F, Bernocchi G, Pellicciari C, Scovassi AI: Morphological Features of Organelles during Apoptosis: An Overview. Cells 2013, 2:294–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Guarda G, Braun M, Staehli F, Tardivel A, Mattmann C, Forster I, Farlik M, Decker T, Du Pasquier RA, Romero P, et al. : Type I interferon inhibits interleukin-1 production and inflammasome activation. Immunity 2011, 34:213–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Aarreberg LD, Esser-Nobis K, Driscoll C, Shuvarikov A, Roby JA, Gale M Jr.: Interleukin-1beta Induces mtDNA Release to Activate Innate Immune Signaling via cGAS-STING. Mol Cell 2019, 74:801–815 e806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schwerk J, Negash A, Savan R, Gale M Jr.: Innate Immunity in Hepatitis C Virus Infection. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2021, 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Burke TP, Engstrom P, Chavez RA, Fonbuena JA, Vance RE, Welch MD: Inflammasome-mediated antagonism of type I interferon enhances Rickettsia pathogenesis. Nat Microbiol 2020, 5:688–696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Diamond DL, Syder AJ, Jacobs JM, Sorensen CM, Walters KA, Proll SC, McDermott JE, Gritsenko MA, Zhang Q, Zhao R, et al. : Temporal proteome and lipidome profiles reveal hepatitis C virus-associated reprogramming of hepatocellular metabolism and bioenergetics. PLoS Pathog 2010, 6:e1000719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Amako Y, Munakata T, Kohara M, Siddiqui A, Peers C, Harris M: Hepatitis C virus attenuates mitochondrial lipid beta-oxidation by downregulating mitochondrial trifunctional-protein expression. J Virol 2015, 89:4092–4101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Abid K, Pazienza V, de Gottardi A, Rubbia-Brandt L, Conne B, Pugnale P, Rossi C, Mangia A, Negro F: An in vitro model of hepatitis C virus genotype 3a-associated triglycerides accumulation. J Hepatol 2005, 42:744–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Piodi A, Chouteau P, Lerat H, Hezode C, Pawlotsky JM: Morphological changes in intracellular lipid droplets induced by different hepatitis C virus genotype core sequences and relationship with steatosis. Hepatology 2008, 48:16–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]