Abstract

Objective

To compare the effect of Healthy for Two/Healthy for You (H42/H4U), a health coaching program, in prenatal care clinics that serve a racially and economically diverse population, on total gestational weight gain (GWG) (vs. usual care). We hypothesize that compared to usual prental care, intervention participants will have lower GWG and lower rates of gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM).

Methods

We report the rationale and design of a pragmatic, parallel arm randomized clinical trial with 380 pregnant patients < 15 weeks gestation with overweight or obesity from one of 6 academic and community-based obstetrics practices, randomized to either H42/H4U or usual prenatal care in a 1:1 ratio. The study duration is early pregnancy to 6 months postpartum. The primary outcome is total GWG, calculated as the difference between first clinic-assessed pregnancy weight and the weight at 37 weeks gestation. Key maternal and infant secondary outcomes include GDM incidence, weight retention at 6 months postpartum, infant weight, maternal health behaviors and wellness.

Conclusions

This pragmatic clinical trial embeds a pregnancy health coaching program into prenatal care to allow parallel testing compared to usual prenatal care on the outcome of total GWG. The real-world design provides an approach to enhance its sustainability beyond the trial with the goal to ultimately improve maternal/child health outcomes and reduce future obesity.

Trial registration:

The study was first registered at clinicaltrials.gov on 1/26/21 (NCT04724330).

Keywords: pregnancy, obesity, overweight, gestational weight gain, lifestyle intervention, postpartum weight retention

1. Introduction

Despite two decades of public health efforts to combat obesity, rates continue to rise and racial and socioeconomic disparities persist1,2. There is an urgent need for obesity prevention efforts to target young adults, particularly reproductive age women3–5. Twenty-three percent of women (vs. 13% of men) gain ≥ 20 kg in their childbeaing years, with the highest weight gain in African American women. Weight gain of ≥ 20 kg between 18 and 55 years is associated with the development of type 2 diabetes (DM) and greater mortality5.

Obesity prior to, during and after pregnancy has been implicated in worsening disparities in maternal mortality in the U.S., as obesity-related complications disproproprionately impact African American women.6–8 Excess gestational weight gain (GWG) and retaining pregnancy weight in the postpartum period are common,9,10 and associated with long-term obesity in women and their offspring, as well as short-term pregnancy complications, including gestational diabetes (GDM) and preeclampsia11–14. Because most people seek prenatal care and are motivated to have a healthy baby, pregnancy and the postpartum period provide “teachable moments” to promote healthy behaviors (i.e., improved diet, exercise) to limit GWG, sustain long-term healthy behaviors for their families, and reduce future obesity and DM15–17.

There is now strong evidence from the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) that limiting GWG is achievable and associated with improved exercise and dietary behaviors18. Importantly, the USPSTF recommends that clinicians “offer pregnant persons effective behavioral counseling interventions aimed at promoting healthy weight gain and preventing excess gestational weight gain in pregnancy (B recommendation).”19 Because previous studies were designed to test the efficacy of behavioral weight management on GWG, the interventions were resource intensive (i.e., in-person counseling and with limited technological components), without a focus on program implementation and sustainability in routine prenatal care settings and lacking intervention focus in the vulnerable postpartum period18,20. To address this critical evidence gap and meet the USPSTF recommendations, there is a need to integrate and test a practical, evidence-based lifestyle intervention in pregnancy and continuing postpartum.

Our team previously developed and pilot-tested the intervention, Healthy for Two/Healthy for You (H42/H4U), an innovative, evidence-based pregnancy/postpartum health coach intervention that utilizes remotely-delivered phone health coaching, a web-based platform with learning activities and mobile phone behavioral tracking to support obstetric providers and clinics to optimize care for pregnant people at highest risk for obesity and future DM 21. The two aims of this paper are to: 1) Describe the design of a pragmatic randomized clinical trial to evaluate the effectiveness of H42/H4U when integrated into prenatal and postpartum care on important maternal and infant outcomes, compared to usual care in a diverse, clinical population; 2) Highlight the features of the trial that enable its implementation into ‘real world’ prenatal clinical practice and workflows, i.e, recruitment by nurses, training of existing clinical staff to deliver health coaching and providing an accessible user-friendly web-based platform for patients to enable sustainable behavior change. Pragmatic clinical trials provide an opportunity to improve the efficiency of clinical trials using data from usual clinical care enounters (e.g., electronic health record [EHR] data) and support ‘real world’ evidence generation that could rapidly lead to its wider implementation and sustainability into clinical practice22,23. We applied the PRagmatic Explanatory Continuum Indicator Summary-2 (PRECIS-2) tool that has 9 domains to guide trialists, clinican and policymakers to make design decisions that facilitate integration of the trial into care and ultimately promote the healthcare relevance of its results24.

2. Methods

Healthy for 2/Healthy for You (H42/H4U) is a parallel arm, pragmatic randomized controlled trial in early pregnancy through 6 months after delivery (N=380) that tests the effectiveness of the H42/H4U health coaching program integrated into prenatal care compared with a usual care comparison group (maintain Health in Pregnancy; mHIP) among pregnant people enrolled from academic and community-based prenatal clinics in a single health system. The primary outcome is total gestational weight gain (GWG) (calculated as 37-week gestation weight minus baseline pregnancy [≤ 15 week gestation] weight). Maternal secondary outcomes include proportion of participants with excessive GWG, gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) incidence and postpartum weight retention at 6 months after delivery. Infant secondary outcomes include infant growth, measured by weight and length at birth, 4- and 6-months of age. Other outcomes include changes in maternal health behaviors (diet, physical activity, breastfeeding) and maternal wellness (depression, sleep and stress). The hypothesis is that women in the H42/H4U arm will have lower total GWG compared to usual care.

Approval was obtained fom the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine Institutional Review Board (11/9/2020).

2.2. Study eligibility and setting

We are recruiting and enrolling pregnant patients from 6 academic and community-based prenatal care clinics in and around the City of Baltimore that serve racially and economically diverse patient populations. In addition to including a multidisciplinary team throughout the trial design and implementation process, we conducted interviews and group meetings with clinical practice leaders, providers and staff at all 6 sites to ensure that the design of the trial was responsive to the needs of busy obstetrics practices25.

As a pragmatic trial, we are applying broad eligibility criteria24: 18 years of age or older, currently have a singleton pregnancy ≤ 15 weeks gestation with any parity status and BMI ≥ 25.0 kg/m2. We will focus on patients with overweight or obesity because of the high prevalence in our clinical populations and because of prior evidence showing an impact of interventions in this population at high risk for obesity-related chronic disease18. Due to budgetary constraints to adapt intervention materials, participants must be able to engage in coaching calls in the English language. Exclusion criteria are multiple fetuses, pre-gestational diabetes, poorly controlled blood pressure, active substance use (excluding marijuana use), eating disorder, psychiatric hospitalization in last 12 months or diagnosis of severe mental illness that is not well controlled. Participants are not required to own a smartphone or iPad for the study, as the study is able to loan them to participants in need and the number of loaners are being tracked to guide future implementation efforts.

2.3. Participant recruitment

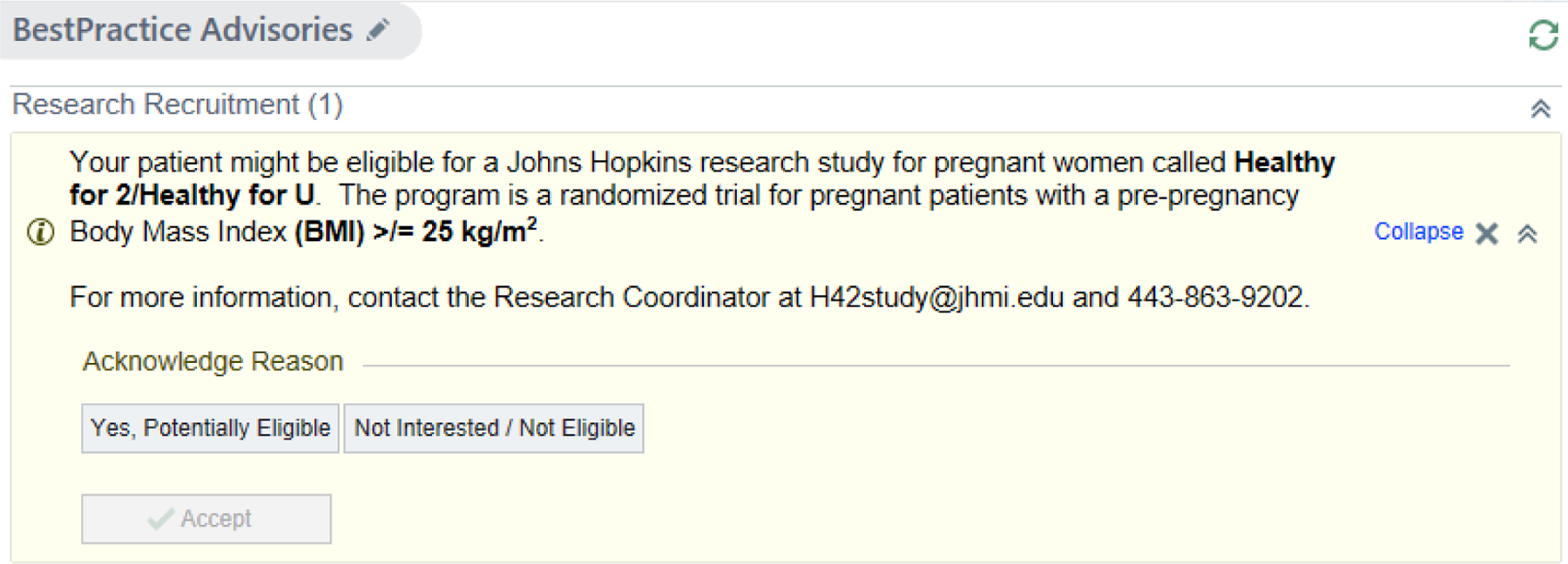

In close collaboration with clinical staff and providers, we designed the screening and recruitment procedures to emulate referral into a ‘real world’ clinical program, leveraging the “Nurse History Visit,” which most clinics have either through telemedicine or in-person. We designed a “Best Practice Advisory” (BPA) in the Epic electronic health record (EHR) to appear at the time of order entry to enable nurses to refer potentially eligible patients to study staff for further screening (see Figure 1). In addition, through conversations with the nurses at our involved clinics, we tailored referral methods to the workflows of the nurses using the Epic EHR, i.e, using features like Patient Lists and Secure Chat. In addition, we review the list of patients for whom the BPA was alerted but no action was taken to assess eligibility and then sent potentially eligible patients recruitment messages using the patient portal. Post-referral screening includes a brief screening process using the Epic EHR and then a phone call to the patient to confirm interest and eligibility. Following screening, eligible patients are consented electronically using a phone and online consent process.

Figure 1.

Screen shot of the Best Practice Advisory used to prompt clinic-based recruitment

2.4. Randomization and blinding

Because the included clinics’ populations are different and not comparable across sites, randomization is at the individual and not clinic (i.e., cluster) level. Because of the intervention intensity, risk of contamination to the usual care control group was deemed to be low. We designed a web-facilitated virtual randomization experience, with an option for in-person randomization as well. Randomization is stratified by practice and BMI (BMI ≥30.0 kg/m2 vs. 25.0–29.9 kg/m2), and within each stratum using randomly varying block sizes. Due to the nature of the lifestyle intervention, participants and health care providers and intervention team cannot be effectively blinded to randomization assignment. Data collectors will be blinded to assignment. Until the end of the trial, all non-intervention team, including study co-investigators and the safety officer will also remain blinded.

2.5. Intervention: Healthy for Two / Healthy for You (H42/H4U)

In addition to our prior formative research to design the intervention26, we are using a continuous quality improvement process. We are conducting mid-point interviews (aiming for 20–25) among racially and economically diverse intervention participants, selected because of their variation in level of platform and coach call engagement (inconsistent to “super” users). We use open ended questions about platform accessibility (including barriers to device or internet connection), ease of use, clarity of content, likeability, relevance and visual appeal (images, colors) and as well as their experience with coaching. We will also carry out 20 exit interviews following completion of the intervention to gain insight into their experiences.

Participants assigned to the H42/H4U intervention receive an approximately 10 month (early pregnancy to 3 months postpartum), remotely-delivered, behavioral lifestyle intervention including health coach phone contacts (with the option for videoconference) and an interactive web-based platform. H42/H4U was designed and pilot tested for feasibility, acceptability and signals of efficacy in clinical settings21. One of the most novel features of this trial is that the intervention is delivered “as in normal practice” by clinical staff and with the use of routinely available equipment (i.e., smart phones, work computers and phones)24.

Table 1 describes the components of the H42/H4U intervention. The core intervention components are remote health coaching, a web-based interactive tool for educational activities and tracking of health behaviors using a home scale, provided by the study (EatSmart digital bathroom scale) and the Fitbit mobile application for physical activity and weight tracking.

Table 1.

H42/H4U Description and Approach

| COACH Framework |

Commitment to self, baby and program: ● Focus on 3 keys to a healthy weight gain goals (healthy eating, exercise, and tracking) ● Completion of learning activities ● Maintain contact with your Coach ● Attend visits with your provider and follow medical advice. Omit/Limit foods and drinks: added sugar, red/processed meats, alcoholic + caffeinated drinks, “unsafe” foods during pregnancy. Add ● Vegetables, fruits, whole grains, nuts, legumes and seafood ● 150 minutes exercise per week (30 min/5 days/week) Communicate with your Coach, OB providers, and support team Honor Your Wellness ● Manage your stress and mood ● Get enough sleep |

| Program Components | |

| Health coaching | Starts as late as 15-weeks gestation to 3 months postpartum Phone calls using a patient-centered motivational interviewing approach (~20 mins) ● 7 weekly contacts in the 2nd trimester ● 1 contact in the 3rd trimester ● 1 contact postpartum ● Up to 2 optional additional contacts ● ~Optional quarterly topic groups (online) Coach case management meetings - twice monthly |

| Mobile phone and online behavioral tracking | Fitbit mobile app to track food and beverage intake and moderate-intensity exercise Weekly Weight Tracker with personalized feedback |

| Interactive online learning and goal setting platform | ● Learning activities focusing on nutrition, exercise, behavior change strategies, wellness (e.g., sleep, mood), long-term obesity prevention ● SMART goal setting activity28 |

| Prenatal care and EHR interface | Direct referral into program (Figure 1); EHR progress reports for providers |

| Obesity and Wellness Behavioral Goals | |

| Pregnancy weight | Within recommended total weight gain based on IOM recommendations48 |

| Postpartum 1 | Return to pre-pregnancy weight and continue to lose an additional 0.5 to 2 lb./week until reaching 5% of pre-pregnancy weight lost49,50 Promote breastfeeding51 |

| Physical activity | ≥150 min/week moderate-intensity exercise 27 |

| Diet | Diet patterns that are higher in vegetables, fruits, nuts, legumes, and fish and lower in added sugar, and red and processed meat 49,52 |

Communication around postpartum weight loss is focused on healthy weight loss consistent with current guidelines and not based on a timeframe of reaching a weight loss goal by 6 or 12 month after delivery

We have partnered closely with participating clinic managers to assist with identifying and training of health coaches, existing clinical staff (e.g., nurses, medical assistants, dietitians, midwives), who then complete training and coaching during their usual work hours. Coaches do not receive additional salary support for their coaching. To acknowledge their important contribution to the program, we provide them with certificates (for completion of training and the program), intructions on represent their new role as “Health Coach” on their resume, letters from the PI commending their work for their Human Resources files, “credit” towards research (required by some units in the hospital), as well as additional “cafeteria gift cards” and holiday-time “thank you’s” whenever possible. Each coach receives 6.5 hours of training focused on delivering the behavioral intervention using a motivational interviewing approach, with topics focused on gestational weight gain and postpartum weight loss guidelines, pregnancy and postpartum nutrition, exercise and wellness. Study-supported health coach managers provide support, oversight, quality control and feedback to the coaches, including case management meetings every other week and as needed, individually. We determined the number of coaching contacts based on prior studies, including our own, showing that high (i.e., 12 or more contacts) and moderate (3 to 11 contacts) intensity interventions were more effective for GWG than low intensity interventions18,21. The total number of planned contacts is 9 (“high-moderate”), with two additional optional “booster” contacts offered for participants who request or need more support. We also offer optional, supplemental, web-based groups led by Coach Managers and experts on topics (e.g., breastfeeding, gestational diabetes, managing holidays, mood/mindfulness). Health coaching contacts are ~ 20 minutes in length and occur weekly for the first 7 weeks in the second trimester, once in the third trimester, and once postpartum.

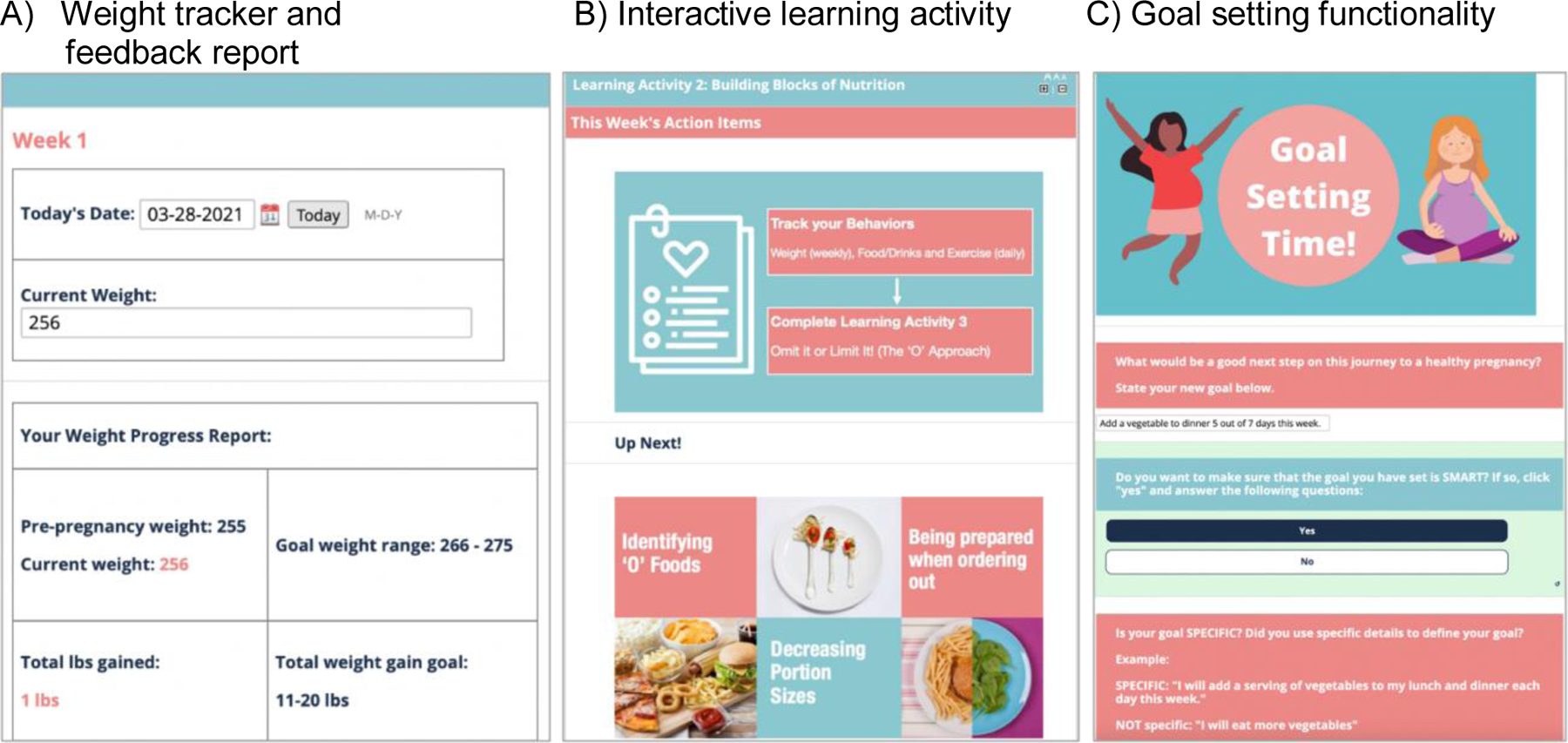

Figure 2 shows screen shots from the H42/H4U web-based platform, which was designed by our team to deliver educational learning activities timed with coach contacts and relevant to the pregnancy or postpartum phase of the intervention. Participants are offered a scale for home usage. Participants self-report weekly weights from their home scale using an email link called the Weekly Weight Tracker, which can be viewed by coaches (Figure 2). Participants receive guidance on downloading and using the mobile application and are advised, based on recommendations from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists27, to record moderate-intensity aerobic exercise in bouts of 10 minutes or more and track all food and beverages consumed daily. Prenatal care providers receive monthly progress updates via the Epic EHR to review patient progress, provide support and encourage participants to be actively engaged in the H42/H4U lifestyle intervention. The curriculum focuses on the core principles of the COACH model (Table 1) and behavioral strategies for lifestyle management, i.e., self-monitoring/tracking behaviors, controlling portion sizes, increasing exercise, communicating effectively, and problem solving21. Goal setting using SMART goals is also a key component of the intervention (Figure 2)28.

Figure 2.

Screen shots of the H42/H4U platform with panels A-C

Participants’ adherence to the intervention is based on completion of coach contacts and web-based learning activities and use of the weekly weight tracker. Participants are periodically asked to allow some of their calls to be audio-recorded for review to ensure the quality and consistency of the health coaching.

2.6. Usual care comparison group: maintain Health in Pregnancy (mHIP)

Women assigned to the comparison group, Maintain Health in Pregnancy (mHIP), will receive typical, guideline-based care in their prenatal care clinic. The current recommended American College of Obstetrics and Gynecologists’ prenatal visit schedule for uncomplicated pregnancies consists of a visit every 4 weeks until 28 weeks, every 2 weeks until 36 weeks, and weekly until delivery.29 “Usual Care” is a rational and important comparator in this study because it is the current standard of care; providing evidence of a meaningful improvement over standard care will demonstrate the effectiveness of the H42/H4U intervention. In the U.S., practice patterns for prenatal care visit frequency and intensity are similar, thus allowing for wide interpretability, applicability, and reproducibility.

2.6. Data Collection and Data Sources

Table 2 shows the measures, time-points and sources of data, described in more detail below. Data collection occurs during 3 time points in pregnancy (baseline, 24 and 37 weeks gestation) and 2 time points postpartum for mother and infant (4 and 6 months after delivery, based on timing of well-infant visits). Consistent with the PRECIS-2 guidance, we have designed data collection to be efficient and unobstrusive, i.e., obtained from EHR data and usual clinical care opportunities whenever possible with study staff validation and verification of key data (maternal height and weight)24. We created a process of continuous data collection, integrating EHR data from prenatal and infant visits into a database to enable both careful tracking for when key data might be missing (e.g., missing weight because a patient missed a visit or changed clinics outside of the health system) and to optimize data cleaning and processing for end of study analyses. We are also verifying calibration of scales in clinics and providing in-clinic trainings for medical assistants on standard methods for obtaining height and weight, especially at the first prenatal visit, which represents our baseline data collection source. Because of concern for inaccurate (or missing) heights in the EHR, our team collects in-person height for verification of the height and weight at one prenatal visit (24 weeks gestation). When weights are missing from the EHR our study staff conduct home visits to obtain measures for all data collection time points (37 weeks gestation; 4 and 6 months postpartum)

Table 2.

Schedule of measures and outcome assessments

| Procedures | Screen | BS/RZD | 24 wks. gest. | 37 wks. gest. (+ birth) | 4 mo. pp | 6 mo. pp |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal Anthropometric Measures | ||||||

| Height | EHR | EHR | EHR + staff assessed | EHR | EHR | EHR |

| Weight1 | EHR | EHR | EHR + staff assessed | EHR | EHR | EHR |

| Maternal Data | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Demographics | EHR | EHR | EHR | EHR | EHR | EHR |

| Encounter data including vital signs (weight, height, BP, Pulse), diagnoses, problem lists, past history | EHR | EHR | EHR | EHR | EHR | EHR |

| Laboratory tests | EHR | EHR | EHR | EHR | EHR | EHR |

| Medications | EHR | EHR | EHR | EHR | EHR | EHR |

| Labor and delivery course discharge summary | EHR | EHR | EHR | EHR | EHR | EHR |

| Infant Data | ||||||

| Demographics | EHR | EHR | EHR | |||

| Encounter data including vital signs (length, weight, head circumference), diagnoses, problem list) | EHR | EHR | EHR | |||

| Laboratory test results | EHR | EHR | EHR | |||

| Medications | EHR | EHR | EHR | |||

| Newborn, nursery or NICU discharge summary | EHR | |||||

| Online Questionnaires | ||||||

| Demographics and Family Characteristics | X | X | X | |||

| Smoking, Marijuana and Alcohol (PRAMS)53 | X | |||||

| COVID19 pandemic wellness and vaccine54 | X | X | ||||

| Usual source of care (PRAMS)53 | X | X | ||||

| Pregnancy Intention (PRAMS)53 | X | |||||

| Dietary Behaviors (DSQ)55 | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Physical activity (IPAQ-SF)56 | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Anxiety and Depression (EPDS)57 | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Perceived Stress Scale (MSPSS)58 | X | X | X | |||

| Sleep quality (PSQI)59 | X | X | X | X | ||

| Breastfeeding practices (CDC-IFPS and PRAMS)53 | X | X | X | X | ||

| Use of Community and Safety Net services (WIC) 53 | X | X | X | |||

| Use of Community and Safety Net services (Home Visiting) 53 | X | X | ||||

| Life Events Inventory, modified (SRRS)60 | X | X | ||||

| Experiences of Discrimination (MDR)61 | X | |||||

| Postpartum Visit Attendance and Social Support (PRAMS)53 | X | |||||

| Postpartum contraception (PRAMS)53 | X | X | ||||

| Infant overall health question53 | X | X | ||||

| Safety surveillance survey | X | X | X | X | ||

| Study Satisfaction Survey – for Intervention Group | X |

Abbreviations: BS=baseline; EHR=electronic health record; mo=month; NICU=neonatal intensive care unit; pp=postpartum; RZD=randomization

2.7. Retention strategies

Both intervention (H42/H4U integrated prenatal and postpartum care) and usual care groups have access to their own separate Facebook pages to promote communication, support and retention in the study. Participants are provided giftcards after each data collection visit: $10 at enrollment; $15 at 24-weeks, $20 at 37-weeks, $25 at 4 months postpartum and $40 at 6 months postpartum.

2.8. Safety Surveillance and monitoring

For active surveillance, we receive alerts in the Epic EHR to enable tracking for all maternal and infant hospitalizations, emergency room (ER) visits and labor and delivery triage evaluations. Participants complete a safety survey about recent hospitalizations or ER visits, problems with exercising or recent injuries. We also have a protocol to alert the team to scores indicating high levels of depressive symptoms based on survey timepoints. The study has an IRB and sponsor-approved Data Safety and Monitoring Plan and an independent Safety Officer to review study progress, intervention adherence and adverse events (mild, moderate, severe).

2.9. Analytic approach

2.9.1. Power and sample size

We based our sample size estimates on the following considerations: 1) 80% or greater follow-up rate for the main outcome of GWG; 2) Range of variance in the primary outcome of GWG; 3) Ability to detect effect sizes comparable to the published literature as well as our pilot data; 4) Two-sided type I α error=0.05; type II β error=0.20.

We expect to enroll at least 380 pregnant patients with overweight or obesity from prenatal care practices. Based on our past experience and review of prior studies, we anticipate 20% loss to follow-up for the 37-week visit, consequential to drop-out for various reasons. With this dropout rate and the assumption that the dropout is consistent with “missing at random”, we expect to retain an effective sample size of 304 participants for our primary outcome, by randomizing N=380 participants, with 190 participants in each arm. Standard deviations (SDs) for the minimum detectable differences (MDDs) evaluation were informed by previous studies of similar combined diet-physical activity behavioral interventions to limit weight gain in pregnancy18,20,30. The MDDs with 80% power range from 1.45 to 2.32 kg with corresponding SDs for GWG between 4.5 and 7.2 kg, under the assumption of 20% random attrition of the proposed sample size of 380. Based on prior studies’ effect sizes, we believe our sample size calculation is conservative and our trial is sufficiently powered to detect clinically relevant effect on GWG by H42/H4U intervention compared to usual care. For the binary maternal categorical outcomes, we calculated 80% power to detect the proportion who have excess GWG (with minimum detectable odds ratios range from 0.48–0.55) and incident GDM (with minimum detectable odds ratios range from 0.10–0.40). All power calculations were performed using the Power and Sample Size (PASS) software.

2.9.2. Statistical analysis plan

The main analyses for the primary and secondary outcomes will follow the intent-to-treat principle. The primary outcome is GWG. The main analysis will utilize a mixed effects regression approach to model baseline and 37-week weight and assess between group difference in mean of total GWG through inclusion of group indicator, time indicator, and their cross-product interaction term in the mean model. This modeling approach has the flexibility to account for the stratification variables used for stratified randomization, to properly address and utilize the correlation between baseline and 37-week weight measures with participant, and include needed covariates to produce valid inferences in presence of missing 37-week weight outcome under the missing at random assumption. Maternal secondary outcomes include the proportion with excessive GWG, GDM incidence, and postpartum weight retention at 4 and 6 months postpartum, calculated as the difference between weight assessed at 4 and 6 months postpartum and baseline (early pregnancy) weight. The between group difference for the binary secondary outcomes, proportion with excessive GWG and GDM incidence, will be compared using generalized estimated equations (GEE) based logistic regression models. We will also assess the between group difference in mean postpartum weight retention over time after delivery using a similar mixed effects modeling approach as the primary outcome, with extended visit indicators in the mean model to represent the 4 and 6 month data in the postpartum period, and appropriate group by visit indicators cross-product interaction terms to capture the postpartum weight retention between groups at those specific time points, while accounting for needed covariates. We will use an unstructured variance-covariance model to allow full flexibility of outcome variability over time and different pairwise outcome correlations within participant between visits for valid statistical inferences.

Similarly, the between group difference in the infant secondary outcomes of birth weight, weight and length at 4 and 6 months of age will be assessed using seperate mixed effects regression models. To assess infants’ weight gain trajectory from birth to 6 months, for example, we will develop a mixed effects model that includes the H42/H4U intervention arm indicator, 2 visit indicators and 2 visit by intervention cross-product interaction terms, as well as appropriate covariates in the mean model. We will again use an unstructured variance-covariance model to allow full flexibility of outcome variability over time and different pairwise outcome correlations within infant between visits for valid statistical inferences. Missing data will be addressed through proper statistical modeling or multiple imputation (e.g., for the GEE analyses) under the missing at random assumptions as the main analyses, supplemented by sensitivity analyses using plausible missing not at random assumptions to examine the roubustness of the main analyses results.

3. Discussion

The goal of this trial is to apply principles of pragmatic trial design, consistent with the PRECIS-2 tool, to address several notable research gaps that have emerged from the evidence base applying behavioral strategies to limit GWG and reduce postpartum weight retention20,24,31. Although prior studies show efficacy for impacting maternal and infant outcomes (e.g., gestational diabetes and infant macrosomia), few focused on program implementation and sustainability in prenatal care settings31. In addition, the various behavioral interventions were intentionally designed to be intensive, with in-person counseling sessions and even with meal replacements20,32, but even before the pandemic there has been a growing need for lower touch (i.e. remote delivery) and technology-based (e.g. online and mobile) interventions, adapted to engage diverse populations33. Finally, we designed H42/H4U to not only follow participants’ outcomes beyond delivery, but additionally to continue intervention into the vulnerable postpartum period when women need emotional support, as well as reinforcement of long-term preventive behaviors to reduce obesity risk34.

Health care systems are utilizing a wide range of “population health” approaches to improve health outcomes and reduce health care costs, often through care management and wellness health coaching 35. Although most health care systems do not yet have a workforce of health coaches, many insurance companies employ health coaches to deliver telephonic coaching programs at a low cost with measurable behavior change outcomes36,37. In this trial, in addition to testing the effectiveness of H42/H4U, our goal is to demonstrate the value of coaching skills for clinical staff (i.e., nurses, dietitians, medical assistants) and their managers, including the value of training and serving as health coaches to high risk patients. In fact, the value potentially goes beyond the benefits to the patients receiving coaching, as coaches learn strategies for behavior change, healthy diet and exercise that they can apply in their own lives, and have shared personal gratification with getting to know and counsel their patients38. Our team additionally plans to assess the implementation (i.e., costs, barriers, facilitators) of this prenatal care-based health coaching program in order to provide support for health coaching as a vital service we can offer to our patients. The cost analysis will be conducted from the perspective of an adopting organization or payer (e.g., Medicaid) to describe the monetary value for positive outcomes and promote insurance coverage of the program to enhance its future scalability.39

Another unique aspect of this trial is the multiple methods for utilizing the EHR to recruit diverse patients from our clinics, obtain outcomes, monitor data collection completeness and communicate with participants, providers and all clinical staff. For recruitment, we designed alerts through the use of Best Practice Advisories that are triggered when a potentially eligible patient presents for early pregnancy care, and enables nurses to directly refer these patients to the study team for further screening. We have additional “back-up” recruitment strategies using the EHR, including using the patient portal to message patients we might have missed. For obtaining outcomes data, we designed a “real time” constant flow of EHR encounter and labor and delivery information into our secure database, to enable us to run reports, assess quality and determine when key data collection timepoints are missing (e.g., so study staff can call participants and arrange home visits). We designed EHR reports from the intervention team to keep providers updated about which patients are enrolled in the intervention arm, and their progress to provide encouragement, which has been effective in other weight management trials 40. We also selected the “Fitbit” mobile tracking application because our health system has plans to integrate its data into the EHR, which will provide infrastructure for our intervention to view and report on these data to coaches.

Like many other studies funded early during the COVID-19 pandemic, we considered the limitations on in-person research in designing our screening procedures for recruitment and randomization, enabling both an in-person and remote process for each. We were fortunate that the H42/H4U intervention had already been intentionally designed to be delivered remotely, in response to prior input from patients about the need to reduce time burden and increase flexibility with coaching sessions. Because our study aims to recruit 50% African American and 40% participants with Medicaid, and also relies on referrals from clinic-based nurses, relationship-building with clinical staff has been a very important consideration when designing our recruitment methods. Because using patient-portal messaging alone could limit outreach to lower income patients 41 we have been working closely with clinican co-investigators, practice managers and clinical staff to integrate our recruitment processes directly into their workflows. The most challenging aspect of the pandemic for our project has been the shift in priorities, away from research and focused on day-to-day operations, like keeping our healthcare workers safe and healthy and keeping our clinics staffed. In fact, many of our clinics have experienced significant reductions in staff, due to budget cuts, attrition and staff illness, limiting our ability to fully engage with them, and also to recruit, train and retain health coaches, who need to spend time above and beyond their clinical duties coaching participants. In fact, a survey of healthcare workers from the Kaiser Family Foundation and The Washington Post reported that 30% considered no longer working in healthcare and more than 60% reported significant mental health concerns42. Ultimately, designing our protocol to have flexibility with virtual and in-person options, and to be responsive to the needs of our clinical partners, will strengthen the potential for the H42/H4U program to ultimately be sustained in our and other complicated health care systems, which are always changing43.

The childbearing years provide a window into our current and future health. However, preventive care opportunities are often missed44. To prevent obesity and reduce its intergenerational effects on children, there is a need to integrate and unify our systems of care, from prenatal care to the postpartum/early newborn transition into primary and pediatric care.15,34,45 46H42/H4U provides an example of a needed strategy that engages women early in pregnancy when they are motivated toward a healthy outcome, provides person-centered motivational interviewing throughout pregnancy and into the often-challenging postpartum period and is inclusive and response to the needs of our clinic-based population, with African American, low-income pregnant people who are at highest risk for maternal morbidity. If shown to be effective, the public health implications will be to expand access to H42/H4U into other health systems, as well as public health safety net programs like early home visiting47.

Conclusion

It is our goal that this study will advance a potentially powerful, prenatal care-based strategy to reduce obesity in young childbearing adults and thereby the intergenerational effects on their children. Our interdisciplinary team brings together engaged academic and community-based obstetricians and pediatricians, our health system’s population health program and researchers with experience in developing, testing and implementing behavioral interventions in both pregnant and non-pregnant adults in real world settings to enable wide dissemination.

Acknowledgments

We wish to express our gratitude to the obstetric nurses conducting the screening and recruitment, our faithful and enthusiastic health coaches, our clinic managers and our research support staff, Julie Kurtz, Josephine Peitz, Sejean Yang, Nikita Patlolla.

Funding

This study is funded by a grant from the NIH-NIDDK (1R18DK122416, PI: Wendy L. Bennett). The funder had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis and interpretation of data, in the writing of the report, and in the decision to submit this article for publication.

We acknowledge assistance for clinical data coordination and retrieval from the Core for Clinical Research Data Acquisition, supported in part by the Johns Hopkins) Institute for Clinical and Translational Research (UL1TR001079).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hales CM, Fryar CD, Carroll MD, Freedman DS, Ogden CL. Trends in Obesity and Severe Obesity Prevalence in US Youth and Adults by Sex and Age, 2007–2008 to 2015–2016. Jama Apr 24 2018;319(16):1723–1725. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.3060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ogden CL, Fryar CD, Hales CM, Carroll MD, Aoki Y, Freedman DS. Differences in Obesity Prevalence by Demographics and Urbanization in US Children and Adolescents, 2013–2016. Jama Jun 19 2018;319(23):2410–2418. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.5158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dietz WH. Obesity and Excessive Weight Gain in Young Adults: New Targets for Prevention. Jama Jul 18 2017;318(3):241–242. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.6119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dutton GR, Kim Y, Jacobs DR Jr., et al. 25-year weight gain in a racially balanced sample of U.S. adults: The CARDIA study. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md) Sep 2016;24(9):1962–8. doi: 10.1002/oby.21573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zheng Y, Manson JE, Yuan C, et al. Associations of Weight Gain From Early to Middle Adulthood With Major Health Outcomes Later in Life. Jama Jul 18 2017;318(3):255–269. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.7092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Creanga AA, Syverson C, Seed K, Callaghan WM. Pregnancy-Related Mortality in the United States, 2011–2013. Obstet Gynecol Aug 2017;130(2):366–373. doi: 10.1097/aog.0000000000002114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Creanga AA, Berg CJ, Syverson C, Seed K, Bruce FC, Callaghan WM. Race, ethnicity, and nativity differentials in pregnancy-related mortality in the United States: 1993–2006. Obstet Gynecol Aug 2012;120(2 Pt 1):261–8. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31825cb87a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moaddab A, Dildy GA, Brown HL, et al. Health Care Disparity and Pregnancy-Related Mortality in the United States, 2005–2014. Obstet Gynecol Apr 2018;131(4):707–712. doi: 10.1097/aog.0000000000002534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deputy NP, Sharma AJ, Kim SY. Gestational Weight Gain - United States, 2012 and 2013. MMWR Morbidity and mortality weekly report Nov 6 2015;64(43):1215–20. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6443a3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gunderson EP, Abrams B. Epidemiology of gestational weight gain and body weight changes after pregnancy. Epidemiol Rev 2000;22(2):261–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zheng Z, Bennett WL, Mueller NT, Appel LJ, Wang X. Gestational Weight Gain and Pregnancy Complications in a High-Risk, Racially and Ethnically Diverse Population. J Womens Health (Larchmt) Jun 19 2018;doi: 10.1089/jwh.2017.6574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Lederman SA, Alfasi G, Deckelbaum RJ. Pregnancy-associated obesity in black women in New York City. Maternal and child health journal Mar 2002;6(1):37–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moore Simas TA, Waring ME, Callaghan K, et al. Weight gain in early pregnancy and risk of gestational diabetes mellitus among Latinas. Diabetes Metab. Nov 9 2017;doi: 10.1016/j.diabet.2017.10.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hutchins F, Abrams B, Brooks M, et al. The Effect of Gestational Weight Gain Across Reproductive History on Maternal Body Mass Index in Midlife: The Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation. J Womens Health (Larchmt) Feb 2020;29(2):148–157. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2019.7839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blake-Lamb T, Boudreau AA, Matathia S, et al. Strengthening integration of clinical and public health systems to prevent maternal-child obesity in the First 1,000Days: A Collective Impact approach. Contemp Clin Trials Feb 2018;65:46–52. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2017.12.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Phelan S Pregnancy: a “teachable moment” for weight control and obesity prevention. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 2010;202(2):135.e1–135.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.06.008 [doi] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bennett WL, Coughlin JW. Applying a Life Course Lens: Targeting Gestational Weight Gain to Prevent Future Obesity. J Womens Health (Larchmt) Feb 2020;29(2):133–134. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2019.8254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cantor AG, Jungbauer RM, McDonagh M, et al. Counseling and Behavioral Interventions for Healthy Weight and Weight Gain in Pregnancy: Evidence Report and Systematic Review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA May 2021;325(20):2094–2109. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.4230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davidson KW, Barry MJ, Mangione CM, et al. Behavioral Counseling Interventions for Healthy Weight and Weight Gain in Pregnancy: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Jama May 25 2021;325(20):2087–2093. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.6949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peaceman AM, Clifton RG, Phelan S, et al. Lifestyle Interventions Limit Gestational Weight Gain in Women with Overweight or Obesity: LIFE-Moms Prospective Meta-Analysis. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md) Sep 2018;26(9):1396–1404. doi: 10.1002/oby.22250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coughlin JW, Martin LM, Henderson J, et al. Feasibility and Acceptability of a Remotely-Delivered Behavioral Health Coaching Intervention to Limit Gestational Weight Gain. Obesity Science & Practice 2020;n/a(n/a):21. doi: 10.1002/osp4.438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ford I, Norrie J. Pragmatic Trials. N Engl J Med Aug 4 2016;375(5):454–63. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1510059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tuzzio L, Larson EB, Chambers DA, et al. Pragmatic clinical trials offer unique opportunities for disseminating, implementing, and sustaining evidence-based practices into clinical care: Proceedings of a workshop. Healthc (Amst) Mar 2019;7(1):51–57. doi: 10.1016/j.hjdsi.2018.12.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Loudon K, Treweek S, Sullivan F, Donnan P, Thorpe KE, Zwarenstein M. The PRECIS-2 tool: designing trials that are fit for purpose. Bmj May 8 2015;350:h2147. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h2147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Norton WE, Loudon K, Chambers DA, Zwarenstein M. Designing provider-focused implementation trials with purpose and intent: introducing the PRECIS-2-PS tool. Implement Sci Jan 7 2021;16(1):7. doi: 10.1186/s13012-020-01075-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ayyala MS, Coughlin JW, Martin L, et al. Perspectives of pregnant and postpartum women and obstetric providers to promote healthy lifestyle in pregnancy and after delivery: a qualitative in-depth interview study. BMC Womens Health Mar 4 2020;20(1):44. doi: 10.1186/s12905-020-0896-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.ACOG Committee Opinion No. 650: Physical Activity and Exercise During Pregnancy and the Postpartum Period. Obstetrics and gynecology 2015;126(6):e135–42. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001214 [doi] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pearson ES. Goal setting as a health behavior change strategy in overweight and obese adults: a systematic literature review examining intervention components. Patient Educ Couns Apr 2012;87(1):32–42. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2011.07.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.American College of Gynecologists and the American Academy of Pediatrics. Guidelines for perinatal care 8th ed. 2017.

- 30.Skouteris H, Hartley-Clark L, McCabe M, et al. Preventing excessive gestational weight gain: a systematic review of interventions. Obesity reviews : an official journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity Nov 2010;11(11):757–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2010.00806.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cantor A, Jungbauer RM, McDonagh MS, et al. Counseling and Behavioral Interventions for Healthy Weight and Weight Gain in Pregnancy: A Systematic Review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force 2021. [PubMed]

- 32.Phelan S, Wing RR, Brannen A, et al. Randomized controlled clinical trial of behavioral lifestyle intervention with partial meal replacement to reduce excessive gestational weight gain. The American journal of clinical nutrition Feb 1 2018;107(2):183–194. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/nqx043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Daly LM, Horey D, Middleton PF, Boyle FM, Flenady V. The Effect of Mobile App Interventions on Influencing Healthy Maternal Behavior and Improving Perinatal Health Outcomes: Systematic Review. JMIR mHealth and uHealth Aug 9 2018;6(8):e10012. doi: 10.2196/10012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Essien UR, Molina RL, Lasser KE. Strengthening the postpartum transition of care to address racial disparities in maternal health. J Natl Med Assoc Nov 29 2018;doi: 10.1016/j.jnma.2018.10.016 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Wolever RQ, Jordan M, Lawson K, Moore M. Advancing a new evidence-based professional in health care: job task analysis for health and wellness coaches. BMC Health Serv Res Jun 27 2016;16:205. doi: 10.1186/s12913-016-1465-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eakin EG, Lawler SP, Vandelanotte C, Owen N. Telephone interventions for physical activity and dietary behavior change: a systematic review. American journal of preventive medicine May 2007;32(5):419–34. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Goode AD, Reeves MM, Eakin EG. Telephone-delivered interventions for physical activity and dietary behavior change: an updated systematic review. American journal of preventive medicine Jan 2012;42(1):81–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.08.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wolever RQ, Eisenberg DM. What is health coaching anyway?: Standards needed to enable rigorous research. Arch Intern Med Dec 12 2011;171(22):2017–8. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Neumann PJ, Sanders GD,Russell LB,Siegel JE,Ganiats TG Cost-Effectiveness in Health and Medicine Oxford University Press; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bennett WL, Gudzune KA, Appel LJ, Clark JM. Insights from the POWER practice-based weight loss trial: a focus group study on the PCP’s role in weight management. J Gen Intern Med Jan 2014;29(1):50–8. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2562-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bennett WL, Bramante CT, Rothenberger SD, et al. Patient Recruitment Into a Multicenter Clinical Cohort Linking Electronic Health Records From 5 Health Systems: Cross-sectional Analysis. J Med Internet Res May 27 2021;23(5):e24003. doi: 10.2196/24003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kirzinger AKA, Hamel L, Brodie M. Kaiser Family Foundation /The Washington Post Frontline Health Care Workers Accessed 11/30/2021, https://files.kff.org/attachment/Frontline%20Health%20Care%20Workers_Full%20Report_FINAL.pdf

- 43.Nash DM, Bhimani Z, Rayner J, Zwarenstein M. Learning health systems in primary care: a systematic scoping review. BMC Fam Pract Jun 23 2021;22(1):126. doi: 10.1186/s12875-021-01483-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bennett WL, Ennen CS, Carrese JA, et al. Barriers to and facilitators of postpartum follow-up care in women with recent gestational diabetes mellitus: a qualitative study. Journal of women’s health (2002) 2011;20(2):239–245. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2010.2233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McCloskey L, Bernstein J, The Bridging The Chasm C, et al. Bridging the Chasm between Pregnancy and Health over the Life Course: A National Agenda for Research and Action. Womens Health Issues May-Jun 2021;31(3):204–218. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2021.01.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Polk S, Edwardson J, Lawson S, et al. Bridging the Postpartum Gap: A Randomized Controlled Trial to Improve Postpartum Visit Attendance Among Low-Income Women with Limited English Proficiency. Womens Health Rep (New Rochelle) 2021;2(1):381–388. doi: 10.1089/whr.2020.0123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dodge KA, Goodman WB, Bai Y, O’Donnell K, Murphy RA. Effect of a Community Agency-Administered Nurse Home Visitation Program on Program Use and Maternal and Infant Health Outcomes: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw Open Nov 1 2019;2(11):e1914522. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.14522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Institute of Medicine, National Research Council Committee to Reexamine IOM Pregnancy Weight Gain. The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health. In: Rasmussen KM, Yaktine AL, eds. Weight Gain During Pregnancy: Reexamining the Guidelines National Academies Press (US) National Academy of Sciences.; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jensen MD, Ryan DH, Apovian CM, et al. 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and The Obesity Society. J Am Coll Cardiol Jul 1 2014;63(25 Pt B):2985–3023. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ferrara A, Hedderson MM, Brown SD, et al. The Comparative Effectiveness of Diabetes Prevention Strategies to Reduce Postpartum Weight Retention in Women With Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: The Gestational Diabetes’ Effects on Moms (GEM) Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial. Diabetes Care Jan 2016;39(1):65–74. doi: 10.2337/dc15-1254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.ACOG Committee Opinion No. 756 Summary: Optimizing Support for Breastfeeding as Part of Obstetric Practice. Obstet Gynecol Oct 2018;132(4):1086–1088. doi: 10.1097/aog.0000000000002891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee. Scientific Report of the 2020 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee: Advisory Report to the Secretary of Agriculture and the Secretary of Health and Human Services U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS), Centers for Disease Control and Promotion 2009.

- 54.University of Southern California Dornsife Center for Economic and Social Research. Understanding America Survey. Understanding Coronvirus in America. https://uasdata.usc.edu/index.php. Accessed 11/30/21.

- 55.National Cancer Institute DoCCPS-EaGRC. Dietary Screener Questionnaires (DSQ) in the NHANES 2009–10: DSQ https://epi.grants.cancer.gov/nhanes/dietscreen/dsq_english.pdf

- 56.Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjostrom M, et al. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc Aug 2003;35(8):1381–95. doi: 10.1249/01.Mss.0000078924.61453.Fb [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry Jun 1987;150:782–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 1983;24:386–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF 3rd, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res May 1989;28(2):193–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Holmes T, Rahe R. The Social Readjustment Rating Scale. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 1967;1(2):213–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Williams DR, Yu Y, Jackson JS, Anderson NB Racial Differences in Physical and Mental Health: Socioeconomic Status, Stress, and Discrimination. Journal of Health Psychology 1997;2(3):335–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]