Abstract

Small- and intermediate-conductance Ca2+-activated potassium (KCa2.x and KCa3.1) channels are activated exclusively by a Ca2+-calmodulin gating mechanism. Wild-type KCa2.3 channels have a Ca2+ EC50 value of ~0.3 μM, while the apparent Ca2+ sensitivity of wild-type KCa3.1 channels is ~0.27 μM. Heterozygous genetic mutations of KCa2.3 channels have been associated with Zimmermann-Laband syndrome and idiopathic noncirrhotic portal hypertension, while KCa3.1 channel mutations were reported in hereditary xerocytosis patients. KCa2.3_S436C and KCa2.3_V450L channels with mutations in the S45A/S45B helices exhibited hypersensitivity to Ca2+. The corresponding mutations in KCa3.1 channels also elevated the apparent Ca2+ sensitivity. KCa3.1_S314P, KCa3.1_A322V and KCa3.1_R352H channels with mutations in the HA/HB helices are hypersensitive to Ca2+, whereas KCa2.3 channels with the equivalent mutations are not. The different effects of the equivalent mutations in the HA/HB helices on the apparent Ca2+ sensitivity of KCa2.3 and KCa3.1 channels may imply distinct modulation of the two channel subtypes by the HA/HB helices. AP14145 reduced the apparent Ca2+ sensitivity of the hypersensitive mutant KCa2.3 channels, suggesting the potential therapeutic usefulness of negative gating modulators.

Keywords: HA/HB helices, S45A/S45B helices, KCa2.3 and KCa3.1 channels, negative gating modulator

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Small- and intermediate-conductance Ca2+-activated potassium (KCa2.x and KCa3.1) channels are voltage independent. Mammalian KCNN genes encode three KCa2.x channel subtypes, including KCa2.1 (SK1), KCa2.2 (SK2), KCa2.3 (SK3), and one KCa3.1 (IK or SK4) channel subtype. These channels are constitutively associated with the Ca2+-binding protein calmodulin (CaM). Both KCa2.x and KCa3.1 channels are activated by a unique Ca2+-CaM gating mechanism.1

Human heterozygous genetic mutations of KCa2.3 channels have been linked to Zimmermann-Laband syndrome (ZLS)2 and idiopathic noncirrhotic portal hypertension (INCPH)3. The ZLS-related (K269E, G350D and S436C) and INCPH-related (V450L) mutant channels exhibited faster kinetics of current activation by Ca2+ upon break-in with whole-cell patch-clamp recordings, and thus were inferred to have elevated apparent Ca2+ sensitivity2. The apparent Ca2+ sensitivity has not been determined quantitatively on any of these ZLS-related or INCPH-related mutant KCa2.3 channels. Meanwhile, heterozygous genetic mutations in KCa3.1, which underlies the so-called Gardos channel in erythrocytes, lead to hereditary xerocytosis. The Gardos channelopathy-related (V282M/E4, S314P5, A322V6 and R352H7–9) mutations were also speculated to cause hypersensitivity to Ca2+ of KCa3.1 channels, mostly based on more prominent responses of mutant channel current to an inhibitor TRAM-345,7,8 or a positive modulator NS3095,6. The apparent Ca2+ sensitivity has only been determined quantitatively on one of these Gardos channelopathy-related mutant channels, KCa3.1_R352H8.

A recent cryo-EM study revealed that the pore forming KCa3.1 channel subunits form a tetrameric structure, with the Ca2+ sensor protein CaM constitutively bound (Fig. 1A).10 In each channel subunit, there are six transmembrane α-helical domains that are denoted S1–S6. CaM interacts with the HA/HB helices, in addition to the linker between the S4 and S5 transmembrane domains (S4–S5 linker).10 The S4–S5 linker consists of two α-helices, S45A and S45B (Fig. 1B). The HA/HB helices from one channel subunit (green), the S45A and S45B helices from a neighboring channel subunit (yellow) and CaM (grey) closely interact with each other. Three of the Gardos channelopathy-related (S314P5, A322V6 and R352H7–9) missense mutations are located in the HA/HB helices, while the fourth one (V282M/E4) is located in the transmembrane S5 domain close to the pore.

Fig. 1. Channelopathy-causing mutations in the S45A/S45B helices and HA/HB helices of human KCa2.3 and human KCa3.1 channels.

(A) The S45A/S45B helices and HA/HB helices of human KCa3.1 channel cryo-EM structure with Ca2+ (PDB: 6cnn). Four CaM are shown in grey. Four channel subunits are shown in different colors (green, yellow, cyan, and magenta). (B) Ca2+ bound CaM (grey), HA and HB helices from one channel subunit (green), the S45A and S45B helices from a neighboring channel subunit (yellow) become a stable structural group. The Gardos channelopathy-related (S314P, A322V and R352H) mutations are shown as spheres (carbon atoms shown in red and nitrogen atoms shown in blue). (C) The S45A/S45B helices and HA/HB helices of a homology model of the human KCa2.3 channel was generated using the human KCa3.1 channel cryo-EM structure with Ca2+. Four CaM are shown in grey. Four channel subunits are shown in different colors (green, yellow, cyan, and magenta). (D) The ZLS-related (S436C) and INCPH-related (V450L) mutations are shown as spheres (carbon atoms shown in red).

Utilizing this cryo-EM structure of human KCa3.1 (PDB code: 6CNN) as a template, we generated a homology model of the human KCa2.3 channel (Fig. 1C). The INCPH-related (V450L) and one of the ZLS-related (S436C) mutations are located in the S45A/S45B helices (Fig. 1D), while the other two ZLS-related (K269E and G350D) mutations are found in the N-terminus and transmembrane domains, respectively.

We previously identified a valine-to-phenylalanine (V-to-F) mutation in the HA helix that causes Ca2+ hypersensitivity in the KCa2.1, KCa2.2 and KCa2.3 subtypes11, but the equivalent V-to-F mutation did not alter the apparent Ca2+ sensitivity in KCa3.1 channels.12 In contrast, an asparagine-to-alanine (N-to-A) mutation in the S45A/S45B helices increased the apparent Ca2+ sensitivity in both KCa2.2a and KCa3.1 channel subtypes.12 Thus, we speculate that the differential modulation of KCa2.3 and KCa3.1 channels may result more from effects mediated by the HA/HB helices than the S45A/S45B helices. Although KCa2.x and KCa3.1 channels are activated by the same Ca2+-CaM gating mechanism, they exhibit differences in their function, modulation and pharmacology.1 The KCa3.1 structures10 and KCa2.x homology models12–15 offer an opportunity to perform structure-function studies and examine the differences between the channel subtypes, which might reveal structural information useful for the design of subtype-selective biophysical tools12 and pharmacological tools16. To the best of our knowledge, Ca2+-hypersensitive human genetic mutations have only been reported in KCa2.3 and KCa3.1 channels, but not in KCa2.1 and KCa2.2 channels. Utilizing these disease-causing mutations in the HA/HB helices and the S45A/S45B helices as biophysical tools, we examined whether mutations in corresponding positions might influence KCa2.3 and KCa3.1 channels differentially.

Here, we quantified the elevated apparent Ca2+ sensitivity of KCa2.3 channels with the INCPH-related (V450L) and the ZLS-related (S436C) mutations in the S45A/S45B helices. Their equivalent mutations in the S45A/S45B helices of KCa3.1 channels also increased the apparent Ca2+ sensitivity. On the other hand, the Gardos channelopathy-related (S314P, A322V and R352H) mutations in the HA/HB helices elevated the apparent Ca2+ sensitivity of KCa3.1 channels, whereas their equivalent mutations in KCa2.3 channels did not change the apparent Ca2+ sensitivity. A negative gating modulator, AP14145, reduced the apparent Ca2+ sensitivity of the INCPH- and ZLS-related mutant KCa2.3 channels, suggesting its potential therapeutic usefulness.

Results

Mutations in the S45A/S45B helices of KCa2.3 and KCa3.1 channels

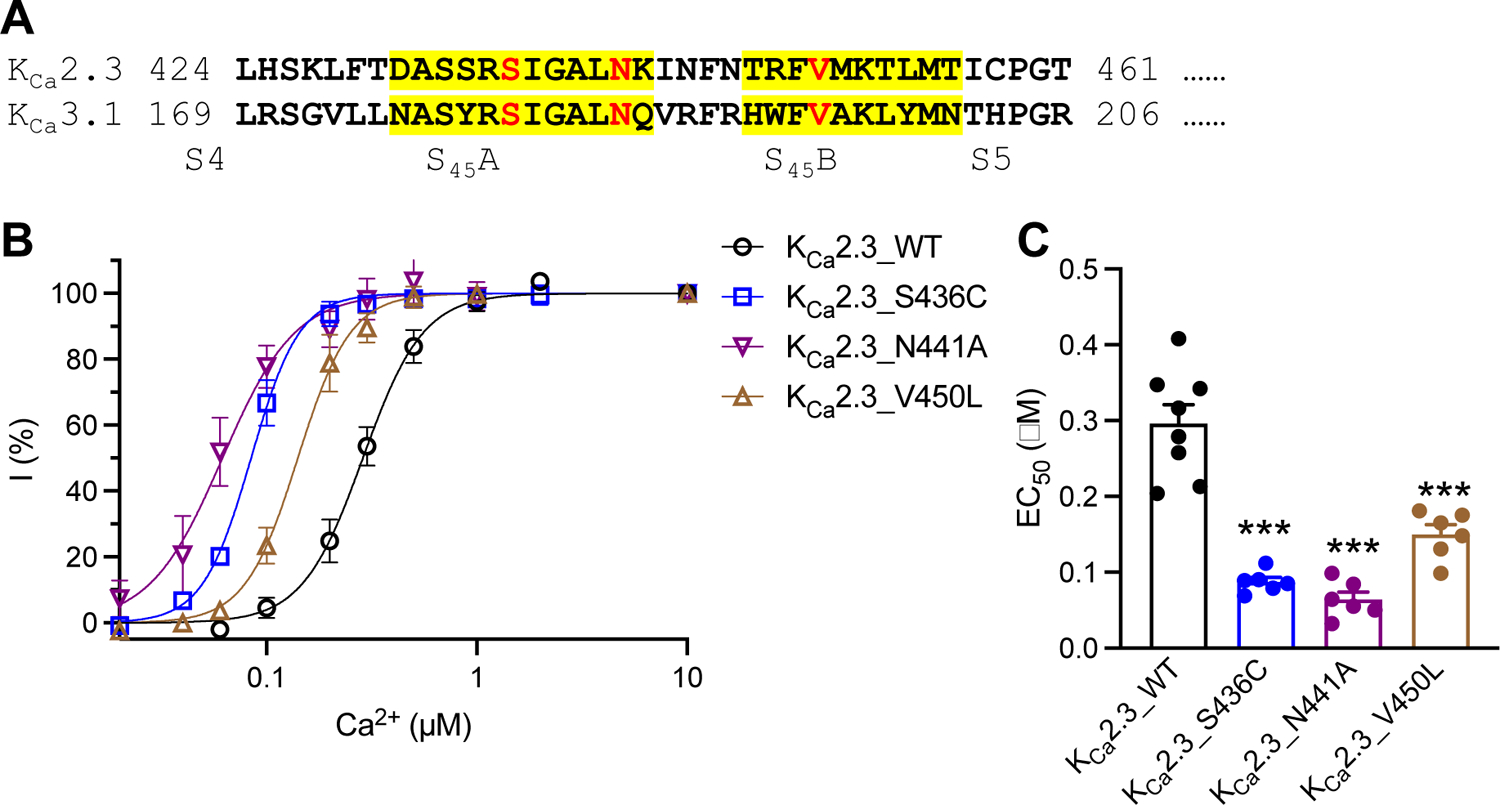

We previously identified an asparagine-to-alanine (N-to-A) mutation in the S45A/S45B helices that increased the apparent Ca2+ sensitivity in both KCa2.2a and KCa3.1 channel subtypes.12 We first investigated the equivalent N441A mutation, together with the ZLS-related S436C and INCPH-related V450L mutations in the S45A/S45B helices of KCa2.3 channels (Fig. 2A). In the study first describing these disease-associated mutations2, the kinetics of current activation by Ca2+ upon break-in during whole-cell patch-clamp recordings was used to infer an increase in apparent Ca2+ sensitivity. In order to quantify this increase in apparent Ca2+ sensitivity, we used the inside-out patch-clamp to measure the Ca2+-dependent activation of the mutant channels heterologously expressed in HEK293 cells (Fig. S1). With the inside-out patch configuration, we were able to measure the responses of the channels to various Ca2+ concentrations from the same patch and determine the apparent Ca2+ sensitivity of the mutant channels. Compared with wild-type (WT) KCa2.3 channel (EC50 = 0.30 ± 0.025 μM, n = 8), the S436C, N441A and V450L mutations effectively elevated the KCa2.3 channel apparent Ca2+ sensitivity (Fig. 2B). EC50 values for Ca2+ were 0.087 ± 0.0058 μM (n = 6, P < 0.0001), 0.064 ± 0.0098 μM (n = 6, P < 0.0001), and 0.15 ± 0.013 μM (n = 6, P < 0.0001), respectively (Fig. 2C and Table 1).

Fig. 2. The ZLS-related (S436C) and INCPH-related (V450L) mutations caused Ca2+ hypersensitivity of KCa2.3 channels.

(A) Amino acid sequence alignment of human KCa2.3 [GenBank: NP_002240.3] and human KCa3.1 [GenBank: NP_002241.1] at the S45A and S45B helices (highlighted in yellow). Amino acid residues mutated are shown in red font. (B) Activation by Ca2+ of the WT and mutant KCa2.3 channels carrying mutations in the S45A/S45B helices. (C) EC50 values for activation by Ca2+ of the WT and mutant KCa2.3 channels. *** P < 0.001 compared with WT. No asterisk means no statistical significance compared with WT.

Table 1.

Apparent Ca2+ sensitivity of WT and mutant channels.

| KCa2.3 | EC50 for Ca2+ (μM) | Hill coefficient | Statistics | KCa3.1 | EC50 for Ca2+ (μM) | Hill coefficient | Statistics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KCa2.3_WT | 0.30 ± 0.025 | 3.88 ± 0.59 | NA | KCa3.1_WT | 0.27 ± 0.012 | 2.87 ± 0.48 | N/A |

| KCa2.3_WT + AP14145 | 1.08 ± 0.10 | 1.34 ± 0.14 | P < 0.0001 vs KCa2.3_WT | ||||

| KCa2.3_K269E | 0.086 ± 0.013 | 3.45 ± 0.46 | P < 0.0001 vs KCa2.3_WT | ||||

| KCa2.3_K269E + AP14145 | 0.14 ± 0.011 | 3.15 ± 0.72 | P < 0.05 vs KCa2.3_K269E | ||||

| KCa2.3_G350D | 0.12 ± 0.013 | 4.19 ± 0.43 | P < 0.0001 vs KCa2.3_WT | ||||

| KCa2.3_G350D + AP14145 | 0.27 ± 0.025 | 3.86 ± 1.09 | P < 0.0001 vs KCa2.3_G350D | ||||

| KCa2.3_S436C | 0.087 ± 0.0058 | 4.37 ± 0.85 | P < 0.0001 vs KCa2.3_WT | KCa3.1_S181C | 0.10 ± 0.011 | 2.78 ± 0.25 | P < 0.0001 vs KCa3.1_WT |

| KCa2.3_S436C + AP14145 | 0.19 ± 0.026 | 2.28 ± 0.45 | P < 0.01 vs KCa2.3_S436C | ||||

| KCa2.3_N441A | 0.064 ± 0.0098 | 4.21 ± 1.09 | P < 0.0001 vs KCa2.3_WT | KCa3.1_N186A | 0.10 ± 0.0055 | 2.66 ± 0.45 | P < 0.0001 vs KCa3.1_WT |

| KCa2.3_V450L | 0.15 ± 0.013 | 4.15 ± 0.58 | P < 0.001 vs KCa2.3_WT | KCa3.1_V195L | 0.20 ± 0.020 | 4.08 ± 0.89 | P < 0.01 vs KCa3.1_WT |

| KCa2.3_V450L + AP14145 | 0.31 ± 0.061 | 3.01 ± 0.62 | P < 0.05 vs KCa2.3_V450L | ||||

| KCa2.3_V555F | 0.067 ± 0.0047 | 3.77 ± 0.20 | P < 0.0001 vs KCa2.3_WT | KCa3.1_V298F | 0.32 ± 0.032 | 3.39 ± 0.43 | P > 0.05 vs KCa3.1_WT |

| KCa2.3_V555F + AP14145 | 0.14 ± 0.015 | 2.81 ± 0.33 | P < 0.001 vs KCa2.3_V555F | ||||

| KCa2.3_A571P | 0.30 ± 0.027 | 2.75 ± 0.25 | P > 0.9999 vs KCa2.3_WT | KCa3.1_S314P | 0.064 ± 0.0033 | 4.07 ± 0.41 | P < 0.0001 vs KCa3.1_WT |

| KCa2.3_T579V | 0.25 ± 0.032 | 2.79 ± 0.47 | P = 0.5666 vs KCa2.3_WT | KCa3.1_A322V | 0.059 ± 0.0039 | 3.94 ± 0.29 | P < 0.0001 vs KCa3.1_WT |

| KCa2.3_R612H | 0.27 ± 0.014 | 2.78 ± 0.23 | P = 0.8339 vs KCa2.3_WT | KCa3.1_R352H | 0.085 ± 0.0081 | 3.66 ± 0.55 | P < 0.0001 vs KCa3.1_WT |

We then tested their equivalent mutations in KCa3.1 channels (Fig. S2). Three equivalent mutations S181C, N186A and V195L also increased apparent Ca2+ sensitivity of KCa3.1 channels (Fig. 3A). EC50 values for Ca2+ of the three mutants were 0.10 ± 0.011 μM (n = 7, P < 0.0001), 0.10 ± 0.0055 μM (n = 5, P < 0.0001), and 0.20 ± 0.020 μM (n = 5, P < 0.01), compared with WT KCa3.1 channels (EC50 = 0.27 ± 0.012 μM, n = 8, Fig. 3B and Table 1).

Fig. 3. The mutations equivalent to KCa2.3_S436C and KCa2.3_V450L caused Ca2+ hypersensitivity of KCa3.1 channels.

(A) Concentration-dependent activation by Ca2+ of the WT and mutant KCa3.1 channels carrying mutations in the S45A/S45B helices. (B) EC50 values for the activation of the WT and mutant KCa3.1 channels by Ca2+. ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001 compared with WT channels. No asterisk means no statistical significance compared with respective WT channels.

Mutations in the HA/HB helices of KCa2.3 and KCa3.1 channels

In our previous study, a valine-to-phenylalanine (V-to-F) mutation in the HA helix caused Ca2+ hypersensitivity in the KCa2.1, KCa2.2 and KCa2.3 subtypes11, but the equivalent V-to-F mutation did not alter the apparent Ca2+ sensitivity in KCa3.1 channels.12 Interestingly, a heterozygous V-to-F mutation in KCa2.3 (V555F) in a young child linked to ZLS was subsequently reported.17 We here investigated this newly reported ZLS-related mutation hypothesizing that it would display increased apparent Ca2+ sensitivity.

We investigated the KCa3.1_V298F mutation, together with the Gardos channelopathy-related (S314P5, A322V6 and R352H7–9) missense mutations located in the HA/HB helices of KCa3.1 channels (Fig. 4A and Fig. S3). Three Gardos channelopathy-related S314P, A322V and R352H mutations increased the apparent Ca2+ sensitivity of KCa3.1 channels (Fig. 4B). The EC50 values for Ca2+ of the three mutants were 0.064 ± 0.0033 μM (n = 9, P < 0.0001), 0.059 ± 0.0039 μM (n = 8, P < 0.0001), and 0.085 ± 0.0081 μM (n = 8, P < 0.0001), compared with WT KCa3.1 channels (EC50 = 0.27 ± 0.012 μM, n = 8, Fig. 4C and Table 1). Consistent with our previous report12, the V298F mutation did not change the apparent Ca2+ sensitivity compared with the WT KCa3.1 channels (Fig. 4C and Table 1).

Fig. 4. The Gardos channelopathy-related (S314P, A322V and R352H) mutations elevated Ca2+ sensitivity of KCa3.1 channels.

(A) Amino acid sequence alignment of human KCa2.3 [GenBank: NP_002240.3] and human KCa3.1 [GenBank: NP_002241.1] at the HA and HB helices (highlighted in green). Amino acid residues mutated are shown in red font. (B) Concentration-dependent activation by Ca2+ of the WT and mutant KCa3.1 channels carrying mutations in the HA/HB helices. (C) EC50 values for the activation of the WT and mutant KCa3.1 channels by Ca2+. *** P < 0.001 compared with WT channels. No asterisk means no statistical significance compared with respective WT channels.

We next tested the equivalent mutations in KCa2.3 channels (Fig. S4). Three equivalent mutations A571P, T579V and R612H did not alter the KCa3.1 channel apparent Ca2+ sensitivity (Fig. 5A). The EC50 values for Ca2+ of the three mutants were 0.30 ± 0.027 μM (n = 8, P > 0.9999), 0.25 ± 0.032 μM (n = 6, P = 0.5666), and 0.27 ± 0.014 μM (n = 11, P = 0.8339), compared with WT KCa2.3 channels (EC50 = 0.30 ± 0.025 μM, n = 8, Fig. 5B and Table 1). On the other hand, the V555F mutation increased the apparent Ca2+ sensitivity compared with the WT KCa2.3 channels (Fig. 5B and Table 1).

Fig. 5. The mutations equivalent to KCa3.1_S314P, KCa3.1_A322V and KCa3.1_R352H did not change apparent Ca2+ sensitivity of KCa2.3 channels.

(A) Activation by Ca2+ of the WT and mutant KCa2.3 channels carrying mutations in the HA/HB helices. (B) EC50 values for activation by Ca2+ of the WT and mutant KCa2.3 channels. *** P < 0.001 compared with WT. No asterisk means no statistical significance compared with WT.

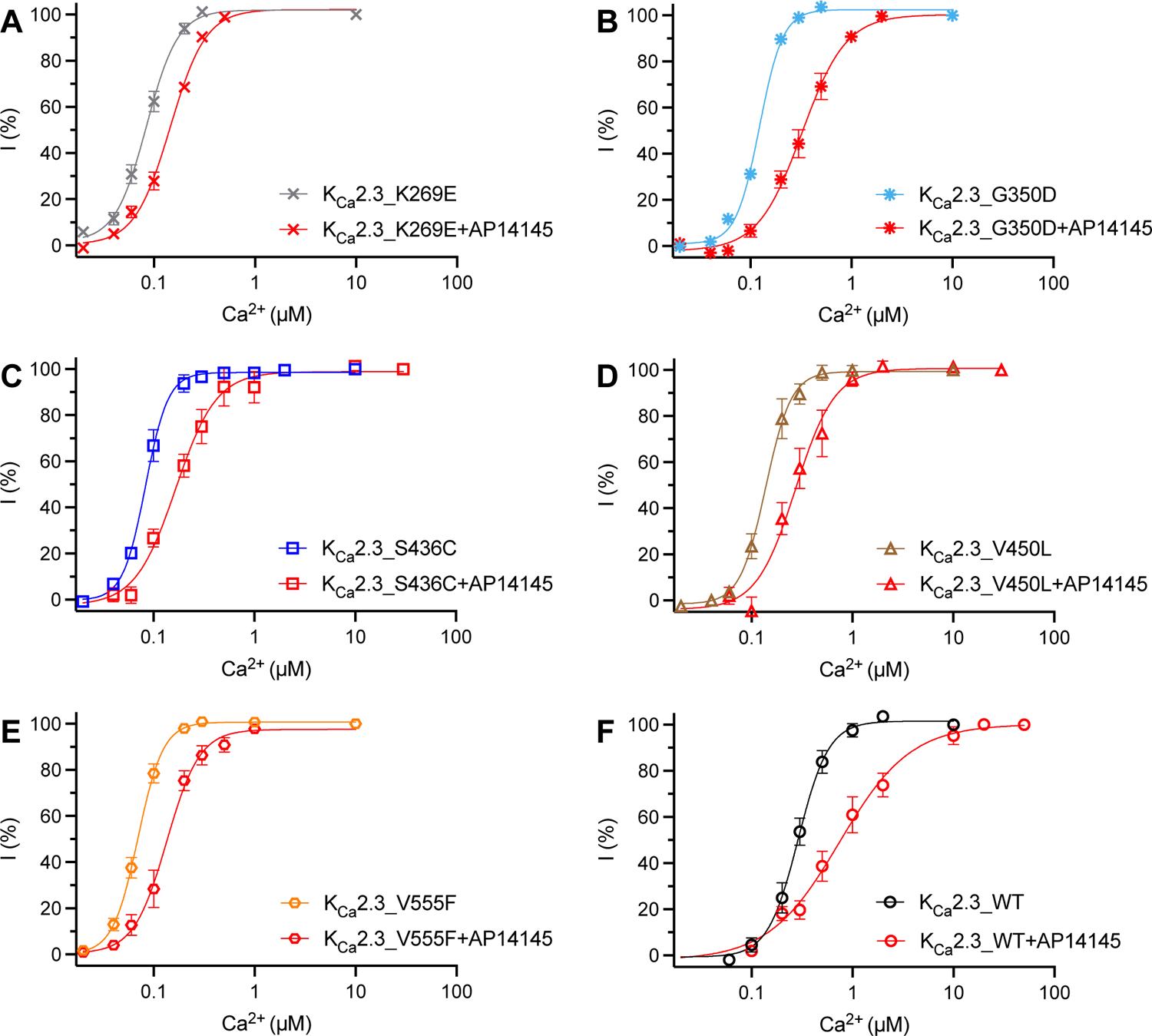

We then tested another two ZLS-related mutations, K269E in the N-terminus (Fig. 6A) and G350D in the transmembrane domains (Fig. 6B) of KCa2.3 channels. Both K269E and G350D mutations increased the apparent Ca2+ sensitivity of KCa2.3 channels, with EC50 values of 0.086 ± 0.013 μM (n = 6, P < 0.0001) and 0.12 ± 0. 013 μM (n = 8, P < 0.0001), respectively (Table 1).

Fig. 6. The effects of AP14145 on the Ca2+-dependent activation of WT and mutant KCa2.3 channels.

Activation by Ca2+ of the KCa2.3_K269E (A), KCa2.3_G350D (B), KCa2.3_S436C (C), KCa2.3_V450L (D), KCa2.3_V555F (E) and KCa2.3_WT (F) channels.

Effects of a negative gating modulator on the mutant KCa2.3 channels

AP3066318, a negative gating modulator of KCa2.3 channels, is currently in early clinical development for conversion of atrial fibrillation19. AP30663 is not commercially available. To explore potential pharmacological therapies for the diseases caused by mutant KCa2.3 channels, we tested the effects of a structurally related compound, AP1414520, on the WT and mutant KCa2.3 channels (Fig. 6A–F). AP14145 (10 μM) right-shifted the Ca2+ concentration-response curves of all the mutant and WT channels, indicating its effectiveness as a negative gating modulator. AP14145 induced a ~3.6-fold decrease in the apparent Ca2+ sensitivity of KCa2.3_WT channels (Fig. 6F, Table 1). Its effects on the mutant channels were somewhat less prominent. AP14145 changed the EC50 values for Ca2+ of KCa2.3_K269E, KCa2.3_G350D, KCa2.3_S436C, KCa2.3_V450L and KCa2.3_V555F channels by ~1.63, ~2.25, ~2.18, ~2.07 and ~2.09 folds, respectively (Fig. 6A–E, Table 1).

Discussion

KCa2.x/KCa3.1 channels are a unique group of potassium channels that are voltage-independent.21 Mutations in both KCa2.3 and KCa3.1 channels have been linked with genetic human disorders. We here quantified the effects of these mutations on the apparent Ca2+ sensitivity of the channels. The Gardos channelopathy-related KCa3.1_S314P5, KCa3.1_A322V6 and KCa3.1_R352H7–9 mutations in the HA/HB helices caused hypersensitivity to Ca2+, which could lead to increased K+ outflow and erythrocyte dehydration5,7,22,23.

The ZLS- and INCPH-related mutations in the S45A/S45B helices increased the apparent Ca2+ sensitivity of KCa2.3 channels. Exactly how the Ca2+ hypersensitivity of KCa2.3 channels leads to ZLS and INCPH is unclear. Increased KCa2.3 channel function in the central nervous system might be related to the defective cognitive function.24 Elevated KCa2.3 channel activity in the vascular endothelium is speculated to be involved in distal digital hypoplasia2. A previous report2 demonstrated faster time courses of channel activation upon breakthrough of the cell membrane to the whole-cell configuration with pipette solution containing 1 μM of Ca2+, implying higher apparent Ca2+ sensitivity of the ZLS- and INCPH-related mutant KCa2.3 channels. In this study, we quantitatively determined the EC50 values for Ca2+ of these mutant channels, using the inside-out configuration (Table 1). They are indeed hypersensitive to Ca2+, with the ZLS-related mutants being more sensitive to Ca2+ than the INCPH-related mutant channel. The reported ZLS2 and INCPH3 patients have heterozygous mutations in their KCNN3 alleles. Their KCa2.3 channels might be comprised of both WT and mutant subunits in the tetrameric channel architecture, which may be speculated to have apparent Ca2+ sensitivity higher than the WT but lower than the mutant channels reported in this study (Table 1).

The amino acid sequences of KCa2.3 at the S45A and S45B helices shares ~59% identity with the KCa3.1 channel (highlighted in yellow, Fig. 2A). These two channel subtypes share ~60% identity at the HA/HB helices (highlighted in green, Fig. 4A). When bound with Ca2+, CaM forms a stable structural group with the HA/HB helices, and the S45A/S45B helices from a neighboring KCa3.1 channel subunit (Fig. 1A,B)10. A homology model of the human KCa2.3 channels showed similar interactions (Fig. 1C,D). Our previous study addressed the crucial role of the interactions between CaM, the HA/HB helices and the S45A/S45B helices for the apparent Ca2+ sensitivity of the channels.12

In this study, we demonstrated that equivalent mutations in the S45A/S45B helices of KCa2.3 (KCa2.3_S436C, KCa2.3_N441A and KCa2.3_V450L) and KCa3.1 (KCa3.1_S181C, KCa3.1_N186A and KCa3.1_V195L) channels elevated the apparent Ca2+ sensitivity of both channel subtypes (Fig. 2 and Fig. 3). In contrast, mutations in the HA/HB helices of KCa3.1 (KCa3.1_S314P, KCa3.1_A322V and KCa2.3_R352H) channels caused Ca2+ hypersensitivity (Fig. 4), whereas their equivalent mutations in KCa2.3 (KCa2.3_A571P, KCa2.3_T579V and KCa2.3_R612H) did not alter the apparent Ca2+ sensitivity (Fig. 5). Furthermore, a mutation in the HA/HB helices of KCa2.3 (KCa2.3_V555F) channels caused Ca2+ hypersensitivity (Fig. 5), whereas its equivalent mutations in KCa3.1 (KCa3.1_V298F) did not change the apparent Ca2+ sensitivity (Fig. 4). As such, more synchronized changes in the apparent Ca2+ sensitivity of KCa2.3 and KCa3.1 channel subtypes were observed in response to equivalent mutations in the S45A/S45B helices. In contrast, these two channel subtypes often exhibited differential responses to equivalent mutations in the HA/HB helices. Given the involvement of KCa2.3 and KCa3.1 channels in genetic disorders, understanding the regulation of their apparent Ca2+ sensitivity is critical. With cryo-EM structures only available for KCa3.1 channels10, caution will be needed when performing structure-function studies of KCa2.x channel subtypes, especially for the HA/HB helices.

It was reported that the apparent Ca2+ sensitivity of KCa2.2 channels can be negatively regulated by the phosphorylation of CaM.25 Indeed, the apparent Ca2+ sensitivity of all KCa2.x/KCa3.1 channel subtypes can be reduced by the phosphorylation of CaM.26 As such, the EC50 values for Ca2+ determined in HEK293 cells may deviate from the apparent Ca2+ sensitivity of the channels expressed in other cell types (e.g. endothelial cells), as a result of the phosphorylation status.26 KCa3.1 is unique among these four subtypes in that its activation can be enhanced by the phosphorylation of a histidine residue (H358) in the HB helix27, possibly by antagonizing copper-mediated inhibition of the channel.28 This unique regulation of KCa3.1 by the phosphorylation of H358 in the HB helix may also echo this notion that KCa3.1 channels are modulated differently by the HA/HB helices from KCa2.x channels.

The pharmacology for KCa3.1 channel subtype has been well developed1. Senicapoc29 and TRAM-3430 inhibit KCa3.1 channels with IC50 values of ~11 nM and ~20 nM, respectively, with selectivity (200–1000-fold) towards IK channels over other channel subtypes. With excellent pharmacokinetic properties in humans, senicapoc has become a potential candidate for the treatment of Gardos channelopathy, a subset of hereditary xerocytosis.31 A clinical trial (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04372498) is studying senicapoc in patients with hereditary xerocytosis caused by KCa3.1 channel mutations. On the other hand, no pharmacological treatment has been explored for ZLS and INCPH caused by KCa2.3 channel mutations. AP14145, which is equipotent in modulating KCa2.2 and KCa2.320, with no effect on KCa3.1, has been reported to treat atrial fibrillation in pigs32 and goats33. A structurally related compound, AP3066318, is currently in early clinical development for conversion of atrial fibrillation19. Our results indicated that AP14145 right-shifted the Ca2+ concentration-response curves (Fig. 6) and reduced the apparent Ca2+ sensitivity (Table 1) of the mutant KCa2.3 channels. The KCa2.3_V450L mutant channel with an EC50 value for Ca2+ of 0.15 ± 0.013 μM (Table 1) is associated with INCPH. This patient with KCa2.3_V450L mutation was not classified as ZLS3. Among the ZLS-related mutant channels, KCa2.3_G350D is the least sensitive to Ca2+ with an EC50 value of 0.12 ± 0.013 μM (Table 1). As such, it can be inferred that mutations that elevate apparent Ca2+ sensitivity to < 0.12 μM can be associated with ZLS. AP14145 was able to reduce the apparent Ca2+ sensitivity of the ZLS-related mutant channels to 0.14 ± 0.011 μM (KCa2.3_K269E + AP14145), 0.27 ± 0.025 μM (KCa2.3_G350D + AP14145), 0.19 ± 0.026 μM (KCa2.3_S436C + AP14145) and 0.14 ± 0.015 μM (KCa2.3_V555F + AP14145, Table 1), implying the potential therapeutic usefulness of negative KCa2 channel gating modulators. The KCNN3 gene encoding KCa2.3 channels has only very recently been associated with ZLS2 and INCPH3. To the best of our knowledge, there are currently no transgenic mouse models for these disorders. Future development of animal models will enable preclinical studies for therapeutic options.

Materials and Methods

Electrophysiology

The effect of mutations on the apparent Ca2+ sensitivity of KCa2.3 and KCa3.1 channels was investigated as previously described.12,15,26 Briefly, mutations were introduced to human KCa2.3 and human KCa3.1 channels using QuickChange II site-directed mutagenesis kit (Agilent) or through molecular cloning services (Genscript). The WT and mutant channel cDNAs, constructed in the pIRES2-AcGFP1 vector (Clontech) were transfected into HEK293 cells by the calcium–phosphate method. AP14145 was purchased from Tocris Bioscience. KCa2.3 and KCa3.1 currents were recorded 1–2 days after transfection, with an Axon200B amplifier (Molecular Devices) at room temperature.

pClamp 10.5 (Molecular Devices) was used for data acquisition and analysis. The resistance of the patch electrodes ranged from 3–5 MΩ. The pipette solution contained (in mM): 140 KCl, 10 Hepes (pH 7.4), 1 MgSO4. The bath solution containing (in mM): 140 KCl, 10 Hepes (pH 7.2), 1 EGTA, 0.1 Dibromo-BAPTA, and 1 HEDTA was mixed with Ca2+ to obtain the desired free Ca2+ concentrations, calculated using the software by Chris Patton of Stanford University (https://somapp.ucdmc.ucdavis.edu/pharmacology/bers/maxchelator/webmaxc/webmaxcS.htm). The Ca2+ concentrations were verified using a Ca2+ calibration buffer kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Briefly, a standard curve was generated using the Ca2+ buffers from the kit and a fluorescence Ca2+ indicator. Then the Ca2+ concentrations of our bath solutions were determined through interpolation on the standard curve.

Currents were recorded using an inside-out patch configuration. The inside-out patch configuration allows us to measure the response of the channels to various Ca2+ concentrations from the same patch and effectively compare the apparent Ca2+ sensitivity of WT and mutant channels. The intracellular face was initially exposed to a zero-Ca2+ bath solution, and subsequently to bath solutions with a series of Ca2+ concentrations. Currents were recorded by repetitive 1-s-voltage ramps from − 100 mV to + 100 mV from a holding potential of 0 mV. One minute after switching of bath solutions, ten sweeps with a 1-s interval were recorded. The integrity of the patch was examined by switching the bath solution back to the zero-Ca2+ buffer. Data from patches, which did not show significant changes in the seal resistance after solution changes, were used for further analysis. To construct the concentration-dependent positive modulation of channel activities, the current amplitudes at − 90 mV in response to various concentrations of Ca2+ were normalized to that obtained at maximal concentration of Ca2+. The normalized currents were plotted as a function of the concentrations of Ca2+. EC50 values and Hill coefficients were determined by fitting the data points to a standard concentration–response curve (Y = 100/(1 + (X/EC50)^ − Hill)). The data analysis was performed using pClamp 10.5 (Molecular Devices) in a blinded fashion. All data are shown as mean ± SEM unless otherwise indicated. One-way ANOVA and Tukey’s post hoc tests were used for data comparison of three or more groups. The Student’s t-test was used for data comparison if there were only two groups.

Computational modeling

We built homology model for the human KCa2.3 channel based on a cryo-EM structure of KCa3.1 channel (PDB Code: 6CNN). Sequence alignment among KCa2.3 and KCa3.1 channels was generated by Clustal Omega server (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalo/). The sequence identity between KCa2.3 and KCa3.1 is 46.6%, which makes the KCa3.1 Cryo-EM structure an excellent structural template to generate homology models for the KCa2.3 channels. We used the MODELLER program34 to generate 10 initial homology models for KCa2.3 channel based on the KCa3.1 structural template, and selected the one with the best internal DOPE score from the program.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Disease-causing mutations elevated the apparent Ca2+ sensitivity of KCa2.3 channels

Disease-causing mutations elevated the apparent Ca2+ sensitivity of KCa3.1 channels

KCa2.3 and KCa3.1 channels are regulated differentially by the HA/HB helices

AP14145 reduced the Ca2+ sensitivity of disease related mutant KCa2.3 channels

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Misa Nguyen, Young Hur, and Lucia Basilio for technical assistance. M.Z. was supported by a Scientist Development Grant 13SDG16150007 from American Heart Association, a YI-SCA grant from National Ataxia Foundation and a grant 4R33NS101182-03 from NIH.

Abbreviations

- N-to-A

Asparagine-to-alanine

- Ca2+

Calcium

- CaM

Calmodulin

- INCPH

Idiopathic noncirrhotic portal hypertension

- KCa3.1 or IK

Intermediate-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels

- KCa2.x or SK

Small-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels

- V-to-F

Valine-to-phenylalanine

- WT

Wild-type

- ZLS

Zimmermann-Laband syndrome

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest

none.

CRediT author statement

Razan Orfali: Investigation

Young-Woo Nam: Methodology, Investigation

Hai Minh Nguyen: Conceptualization, Investigation

Mohammad Asikur Rahman: Investigation

Grace Yang: Investigation

Meng Cui: Investigation

Heike Wulff: Conceptualization, Resources, Writing-Reviewing and Editing

Miao Zhang: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Writing-Original Draft

References

- 1.Brown BM, Shim H, Christophersen P & Wulff H Pharmacology of small- and intermediate-conductance calcium-activated potassium channels. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 60, 219–240 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bauer CK et al. Gain-of-Function Mutations in KCNN3 Encoding the Small-Conductance Ca(2+)-Activated K(+) Channel SK3 Cause Zimmermann-Laband Syndrome. Am J Hum Genet 104, 1139–1157 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koot BG, Alders M, Verheij J, Beuers U & Cobben JM A de novo mutation in KCNN3 associated with autosomal dominant idiopathic non-cirrhotic portal hypertension. J Hepatol 64, 974–7 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Glogowska E, Lezon-Geyda K, Maksimova Y, Schulz VP & Gallagher PG Mutations in the Gardos channel (KCNN4) are associated with hereditary xerocytosis. Blood 126, 1281–4 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fermo E et al. Gardos channelopathy: functional analysis of a novel KCNN4 variant. Blood Adv 4, 6336–6341 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mansour-Hendili L et al. Multiple thrombosis in a patient with Gardos channelopathy and a new KCNN4 mutation. Am J Hematol (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fermo E et al. ‘Gardos Channelopathy’: a variant of hereditary Stomatocytosis with complex molecular regulation. Sci Rep 7, 1744 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rapetti-Mauss R et al. A mutation in the Gardos channel is associated with hereditary xerocytosis. Blood 126, 1273–80 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andolfo I et al. Novel Gardos channel mutations linked to dehydrated hereditary stomatocytosis (xerocytosis). Am J Hematol 90, 921–6 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee CH & MacKinnon R Activation mechanism of a human SK-calmodulin channel complex elucidated by cryo-EM structures. Science 360, 508–513 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nam YW et al. A V-to-F substitution in SK2 channels causes Ca(2+) hypersensitivity and improves locomotion in a C. elegans ALS model. Sci Rep 8, 10749 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nam YW et al. Hydrophobic interactions between the HA helix and S4–S5 linker modulate apparent Ca(2+) sensitivity of SK2 channels. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 231, e13552 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shim H et al. The Trials and Tribulations of Structure Assisted Design of KCa Channel Activators. Front Pharmacol 10, 972 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ledford HA et al. Different arrhythmia-associated calmodulin mutations have distinct effects on cardiac SK channel regulation. J Gen Physiol 152(2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nam YW et al. Subtype-selective positive modulation of KCa2 channels depends on the HA/HB helices. Br J Pharmacol, 1–13 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.El-Sayed NS et al. Structure-Activity Relationship Study of Subtype-Selective Positive Modulators of KCa2 Channels. J Med Chem (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gripp KW et al. Syndromic disorders caused by gain-of-function variants in KCNH1, KCNK4, and KCNN3-a subgroup of K(+) channelopathies. Eur J Hum Genet 29, 1384–1395 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bentzen BH et al. Mechanisms of Action of the KCa2-Negative Modulator AP30663, a Novel Compound in Development for Treatment of Atrial Fibrillation in Man. Front Pharmacol 11, 610 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gal P et al. First Clinical Study with AP30663 - a KCa 2 Channel Inhibitor in Development for Conversion of Atrial Fibrillation. Clin Transl Sci 13, 1336–1344 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Simo-Vicens R et al. A new negative allosteric modulator, AP14145, for the study of small conductance calcium-activated potassium (KCa 2) channels. Br J Pharmacol 174, 4396–4408 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xia XM et al. Mechanism of calcium gating in small-conductance calcium-activated potassium channels. Nature 395, 503–507 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Picard V et al. Clinical and biological features in PIEZO1-hereditary xerocytosis and Gardos channelopathy: a retrospective series of 126 patients. Haematologica 104, 1554–1564 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaestner L, Bogdanova A & Egee S Calcium Channels and Calcium-Regulated Channels in Human Red Blood Cells. Adv Exp Med Biol 1131, 625–648 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martin S et al. SK3 Channel Overexpression in Mice Causes Hippocampal Shrinkage Associated with Cognitive Impairments. Mol Neurobiol 54, 1078–1091 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bildl W et al. Protein kinase CK2 Is coassembled with small conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels and regulates channel gating. Neuron 43, 847–858 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nam YW et al. Differential modulation of SK channel subtypes by phosphorylation. Cell Calcium 94, 102346 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Srivastava S et al. Histidine phosphorylation of the potassium channel KCa3.1 by nucleoside diphosphate kinase B is required for activation of KCa3.1 and CD4 T cells. Mol Cell 24, 665–675 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Srivastava S et al. Histidine phosphorylation relieves copper inhibition in the mammalian potassium channel KCa3.1. Elife 5(2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stocker JW et al. ICA-17043, a novel Gardos channel blocker, prevents sickled red blood cell dehydration in vitro and in vivo in SAD mice. Blood 101, 2412–8 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wulff H et al. Design of a potent and selective inhibitor of the intermediate-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel, IKCa1: a potential immunosuppressant. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97, 8151–6 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rapetti-Mauss R, Soriani O, Vinti H, Badens C & Guizouarn H Senicapoc: a potent candidate for the treatment of a subset of hereditary xerocytosis caused by mutations in the Gardos channel. Haematologica 101, e431–e435 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Citerni C et al. Inhibition of KCa2 and Kv11.1 Channels in Pigs With Left Ventricular Dysfunction. Front Pharmacol 11, 556 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gatta G et al. Effective termination of atrial fibrillation by SK channel inhibition is associated with a sudden organization of fibrillatory conduction. Europace 23, 1847–1859 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sali A & Blundell TL Comparative protein modelling by satisfaction of spatial restraints. J Mol Biol 234, 779–815 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.