Abstract

Background

The Plasmodium falciparum dihydrofolate reductase (PfDHFR) inhibitors pyrimethamine and cycloguanil (the active metabolite of proguanil) have important roles in malaria chemoprevention, but drug resistance challenges their efficacies. A new compound, P218, was designed to overcome resistance, but drug-susceptibility data for P falciparum field isolates are limited.

Methods

We studied ex vivo PfDHFR inhibitor susceptibilities of 559 isolates from Tororo and Busia districts, Uganda, from 2016 to 2020, sequenced 383 isolates, and assessed associations between genotypes and drug-susceptibility phenotypes.

Results

Median half-maximal inhibitory concentrations (IC50s) were 42 100 nM for pyrimethamine, 1200 nM for cycloguanil, 13000 nM for proguanil, and 0.6 nM for P218. Among sequenced isolates, 3 PfDHFR mutations, 51I (100%), 59R (93.7%), and 108N (100%), were very common, as previously seen in Uganda, and another mutation, 164L (12.8%), had moderate prevalence. Increasing numbers of mutations were associated with decreasing susceptibility to pyrimethamine, cycloguanil, and P218, but not proguanil, which does not act directly against PfDHFR. Differences in P218 susceptibilities were modest, with median IC50s of 1.4 nM for parasites with mixed genotype at position 164 and 5.7 nM for pure quadruple mutant (51I/59R/108N/164L) parasites.

Conclusions

Resistance-mediating PfDHFR mutations were common in Ugandan isolates, but P218 retained excellent activity against mutant parasites.

Keywords: malaria, Plasmodium falciparum, antifolate resistance, PfDHFR

Mutations in Plasmodium falciparum dihydrofolate reductase mediate resistance to established inhibitors. P218, designed to circumvent resistance, was highly active against malaria parasites freshly isolated in Uganda, with only modest decreases in activity against mutant parasites resistant to older inhibitors.

Mutations in Plasmodium falciparum dihydrofolate reductase (PfDHFR) are common, and they compromise the antimalarial activities of inhibitors of this enzyme, notably pyrimethamine, a component of sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine (SP), and cycloguanil, the active metabolite of proguanil [1]. With current levels of resistance, PfDHFR inhibitors are generally no longer recommended for the treatment of malaria, but SP is recommended by the World Health Organization and widely used for chemoprevention in Africa, in particular as intermittent preventive therapy in pregnancy and, with amodiaquine, as seasonal malaria chemoprevention in children [2]. Proguanil is used, in combination with atovaquone, for chemoprophylaxis in travelers to malarious areas [3]. In this context, a promising new approach is the design of PfDHFR inhibitors that circumvent resistance mediated by mutations in parasites now circulating in Africa.

Plasmodium falciparum dihydrofolate reductase, which is part of the bifunctional dihydrofolate reductase-thymidylate synthase ([DHFR-TS] PF3D7_0417200) enzyme, converts dihydrofolic acid to tetrahydrofolic acid, which is required by enzymes necessary for deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) synthesis. Three PfDHFR mutations, 51I, 59R, and 108N, are very common in P falciparum across Africa [1] and mediate stepwise increases in resistance to pyrimethamine and cycloguanil [4]. An additional mutation, 164L, mediates higher-level resistance to pyrimethamine and cycloguanil [5, 6]. The PfDHFR 164L mutation has been very uncommon in Africa [7], but modest prevalence has been identified in some areas, including southwestern Uganda [8]. An increase in 164L mutation prevalence in Uganda in recent years [9, 10] emphasizes the relevance of the design of novel PfDHFR inhibitors that circumvent existing resistance mechanisms.

Exploration of the crystal structures of wild-type (WT) and mutant PfDHFR and mutagenesis experiments identified specific mechanisms of resistance to pyrimethamine and cycloguanil and enabled target-specific design of inhibitors acting against both WT and mutant parasites [1, 11–13]. Among novel inhibitors recently under development is P218, a 2,4-diaminopyrimidine [14, 15]. P218 has a flexible pyrimidine side-chain, enabling the drug to anchor to the conserved D54 residue in both WT and mutant parasites, as well as a carboxylate group forming hydrogen bonds with another conserved residue, R122, leading to tighter inhibitor-enzyme binding than for pyrimethamine [14, 16]. A 5-atom linker helps to prevent interaction with residue 108, for which mutation to asparagine mediates resistance [16]. By residing almost entirely in the dihydrofolate substrate pocket, P218 is less likely than other inhibitors to be affected by small steric changes that result from amino acid substitutions, and it has been shown to have potent activity against WT and mutant strains of P falciparum [14]. Unlike the case with other available inhibitors, binding of P218 to PfDHFR is only minimally affected by the 164L mutation [16]. Favorable enzyme selectivity, good safety and tolerability, and chemoprevention efficacy in initial trials led to interest in P218 as a novel chemopreventive agent [14, 17, 18]. However, the relatively short half-life of P218 challenged utility for chemoprevention, and recently this led to a pause in development.

In addition to initial promising results showing activity of P218 against P falciparum laboratory strains with various PfDHFR mutations, it is of interest to determine its activity against parasites of varied genotypes circulating in the field. We therefore examined ex vivo susceptibilities to P218, the PfDHFR inhibitors pyrimethamine and cycloguanil, and the cycloguanil prodrug proguanil of P falciparum isolates collected from Tororo and Busia districts, Uganda, and explored associations between pfdhfr genotypes and drug-susceptibility phenotypes for these isolates.

METHODS

Samples for Study

Subjects over 6 months of age presenting between July 2016 and June 2020 at the outpatient clinics of Tororo District Hospital, Tororo District or Masafu General Hospital, Busia District with clinical suspicion for malaria and a positive Giemsa-stained blood film for P falciparum and without signs of severe disease were enrolled after informed consent, as previously described [19]. Blood was collected in a heparinized tube before initiation of treatment with artemether-lumefantrine, following national guidelines. The studies were approved by the Makerere University Research and Ethics Committee, the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology, and the University of California, San Francisco Committee on Human Research.

Ex Vivo Drug-Susceptibility Assays

Samples with parasitemias ≥0.3% were placed into culture after removal of plasma and buffy coat. Aliquots of blood samples were stored on Whatman 3MM filter paper for molecular analysis. Pyrimethamine, cycloguanil, proguanil, and P218 (all provided by Medicines for Malaria Venture) were prepared as 50 mM (for pyrimethamine) and 10 mM (for all others) stock solutions in dimethyl sulfoxide. Stock solutions were stored at −20°C, and working solutions were freshly prepared within 24 h of susceptibility tests and stored at 4°C.

Drug-susceptibility assays were performed as previously described [19]. Drugs were serially diluted 3-fold in 96-well assay plates in complete media (Roswell Park Memorial Institute [RPMI] 1640 medium supplemented with 25 mM HEPES, 0.2% NaHCO3, 0.1 mM hypoxanthine, 100 µg/mL gentamicin, and 0.5% AlbuMAX II; Invitrogen) before adding parasite culture to reach a parasitemia of 0.2% and hematocrit of 2% in a volume of 200 µL. Drug-free and parasite-free controls were included. Plates were incubated for 72 hours in a humidified modular incubator under 90% N2, 5% CO2, and 5% O2 at 37°C, and parasite growth was then quantified based on SYBR Green fluorescence, as previously described [19]. In brief, after the 72-hour incubation, plates were frozen at −80°C and thawed, and, after mixing, 100 µL from each well was transferred to a black 96-well plate containing 100 µL/well SYBR Green lysis buffer (20 mM Tris buffer, 5 mM EDTA, 0.008% saponin, 0.08% Triton X-100, and 0.2 µL/mL SYBR green I), plates were incubated for 1 hour in the dark at room temperature, and fluorescence was measured with a FLUOstar Omega plate reader ([BMG LabTech] 485-nm excitation/530-nm emission). Laboratory control strains Dd2 and 3D7 (BEI Resources) were assessed monthly. Half-maximal inhibitory concentrations (IC50s) were derived by plotting fluorescence intensity against log drug concentration and fitting to nonlinear curves using a 4-parameter Hill equation in Prism 8.4 (GraphPad Software), with modifications for graphs with limited curve fit or incomplete curves as previously described [19]. Well-to-well variability and signal-to-noise ratios were assessed for each plate using the Z-factor test statistic: Z = 1-((3SDinfected + 3SDuninfected)/(signalinfected-signaluninfected)) [20]. Results with poor curve fit (typically Z < 0.5) or obvious poor fit on visual inspection were discarded.

Sequencing of Ugandan Plasmodium falciparum Deoxyribonucleic Acid

DNA was extracted from dried blood spots using Chelex-100. For dideoxy sequencing, pfdhfr was amplified by 2 nested polymerase chain reactions (PCRs) using primers we designed to specifically target pfdhfr-TS, PfDHFR_F1_R1_f (ACTAGCCATTTTTGTATTCCCA) and PfDHFR_F1_R1_r (CATATGACATGTATCT TTGTCATCATTC) for round 1, and PfDHFR_F1_R2_f (CTCCTTTTTATGATGGAACAAGTC) and PfDHFR_F1_R2_r (CATCGCTAACAGAAATAATTTG) for round 2 for the upstream region, and PfDHFR_F2_R1_f (GAGGTTCCGTTGTTTATCAAG) and PfDHFR_F2_R1_r (CTTAACCGTTCAG GTAATTTTGTCATC) for round 1, and PfDHFR_F2_R2_f (CAAATTATTTCTGTTAGCGATG) and PfDHFR_F2_R2_r (CAATGGATATGGCTGCTTAATATTG) for round 2 for the downstream region. The PCR products were purified with Ampure beads (Beckman Coulter) and sequenced by standard dideoxy techniques. Sequences were analyzed with CodonCodeAligner (CodonCode Corporation), with the 3D7 pfdhfr sequence as reference.

For a subset of samples, collected in 2016–2018, pfdhfr sequences were determined using molecular inversion probe (MIP) capture and deep sequencing [9, 21]. The MIP panel and pfdhfr-specific probes were designed using MIPTools software (v.0.19.12.13; https://github.com/bailey-lab/MIPTools) [9]. The MIP capture, library preparation, and sequencing were performed as previously described [9]. MIPTools was used to analyze raw sequencing data [9, 21]. Sequencing reads are available in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Sequence Read Archive (accession numbers PRJNA655702, PRJNA660547, and MZ485499-MZ485781).

Determination of GTP Cyclohydrolase I Gene Copy Number

Plasmodium falciparum GTP cyclohydrolase I (pfgchI) gene copy numbers were determined using SYBR Green-based quantitative PCR of extracted blood spot DNA. Assays were set up in triplicate, with Dd2, D6, and V1/S laboratory strain DNA as controls, and each isolate was tested in at least 3 independent experiments. Amplification of pfgchI and the housekeeping gene seryl-tRNA synthetase (PF3D7_0717700) was performed as previously described, with the exceptions that a final primer concentration of 1 µM and an ABI Prism 7500 real-time PCR machine were used [22]. Relative copy numbers were determined by subtracting the computed tomography (CT) value for the target gene from the CT for the housekeeping gene for each primer pair and converting the ∆CT to 2∆CT.

Statistical Analysis

Correlations between susceptibilities to different drugs were analyzed with the Spearman-rank test using Prism 8.4. Associations between genotypes and drug susceptibilities were analyzed with the Mann-Whitney U test using Prism 8.4. P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Varied Susceptibilities of Ugandan Isolates to PfDHFR Inhibitors

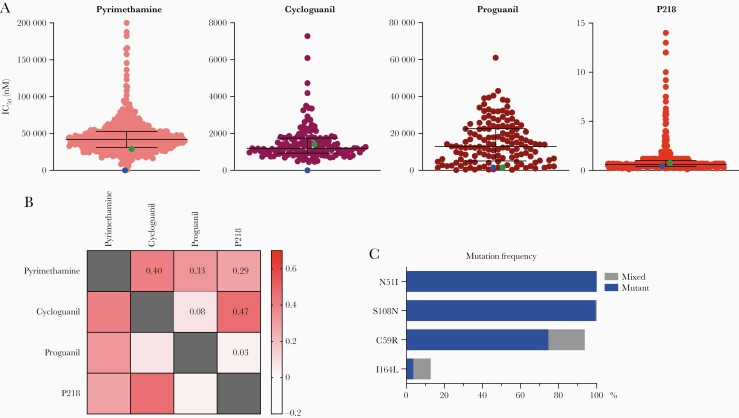

We studied ex vivo susceptibilities of 559 isolates from Tororo and Busia districts, collected from 2016 to 2020, to pyrimethamine and P218; 151 isolates, collected in 2018, were also studied for susceptibilities to cycloguanil and proguanil. We observed a range of susceptibilities to the tested compounds (Figure 1A, Table 1). Susceptibilities to pyrimethamine (median IC50 42 100 nM) and cycloguanil (median IC50 1200 nM) indicated high-level resistance. These results contrasted with those for the 3D7 strain (Table 1), which has WT pfdhfr sequence, but were similar to those for the Dd2 strain, which has 3 PfDHFR mutations. Susceptibilities to proguanil, which does not exert antimalarial effects via direct PfDHFR inhibition, demonstrated a wide range; unlike the case for pyrimethamine and cycloguanil, proguanil susceptibilities were similar between the 3D7 and Dd2 strains, which both had median IC50s approximately 10-fold lower than those of tested Ugandan isolates. Susceptibilities to P218 were consistently in the low nanomolar range, with a median IC50 of 0.6 nM, and similar results for 3D7 and Dd2. Evaluation of correlations between susceptibilities to the tested compounds showed correlations (r > 0.25) for results between pyrimethamine and cycloguanil, proguanil, or P218 and between cycloguanil and P218 (Figure 1B). Our results indicate varied susceptibilities to pyrimethamine, cycloguanil, and proguanil, but consistently potent susceptibility to P218 for Ugandan isolates.

Figure 1.

Susceptibilities to tested inhibitors, correlations of susceptibilities, and genotypes of Ugandan isolates. (A) Ex vivo susceptibilities of Ugandan Plasmodiumfalciparum isolates. Each point represents an individual isolate. Horizontal bars show medians and interquartile ranges. Green and blue points show means for Dd2 and 3D7 strain parasites, respectively. (B) Heat map demonstrating correlations. Spearman’s coefficients (r) are indicated numerically and by the color scale. (C) Mutation frequencies. Frequencies, including isolates with pure mutant (blue) and mixed wild-type/mutant (gray) genotypes, are shown. IC50, half-maximal inhibitory concentration.

Table 1.

Inhibitor Susceptibilities of Ugandan Plasmodium falciparum Isolates and Laboratory Control Strains

| Ugandan Isolates | Laboratory Strains | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inhibitor | Na | Median IC50 (nM) | IC50 Range (nM) | 3D7 (Median IC50, nM (n)) | Dd2 (Median IC50, nM (n)) |

| Pyrimethamine | 528 | 42 100 | 998–200 000 | 27 (40) | 28 900 (40) |

| Cycloguanil | 151 | 1200 | 450–7300 | 4.8 (9) | 1400 (8) |

| Proguanil | 141 | 13 000 | 190–61 000 | 1600 (8) | 1700 (7) |

| P218 | 545 | 0.6 | 0.1–14 | 0.4 (38) | 0.7 (39) |

Abbreviations: IC50, half-maximal inhibitory concentrations.

aTotal number of isolates tested.

Pfdhfr Genotypes of Ugandan Isolates

Mutations in PfDHFR are associated with malaria treatment failure for sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine [4, 23]. To determine whether mutations in PfDHFR were associated with decreased ex vivo susceptibility to the tested inhibitors in Ugandan P falciparum isolates, we sequenced pfdhfr from 383 isolates with varied susceptibilities to the tested compounds. Of these isolates, 383 carried the 51I (100% pure mutant) and 108N (99.5% pure mutant, 0.5% mixed WT/mutant) mutations, and 359 (93.7%) had an additional 59R mutation either as a pure mutant (286, 79.7%) or in a mixed genotype (73, 20.3%) (Figure 1C, Table 2). The high prevalence of this triple mutant genotype was consistent with results from prior studies of Ugandan isolates [9, 10]. More importantly, 12.8% of isolates also harbored an additional mutation, 164L, which was previously much less common in eastern Uganda [10, 24], and has been linked to high-level resistance to pyrimethamine [4]. Two isolates harbored the 51I, 108N, and 164L mutations, but lacked the 59R mutation. Additional PfDHFR mutations (V8G, A16V, C60W, K117N, T229K) were found uncommonly, none in more than 2 of the 383 studied isolates. Overall, most isolates had double (51I, 108N) or triple (51I, 108N, 59R) PfDHFR mutations, and 12.3% carried the quadruple (51I, 108N, 59R, 164L) mutation (Table 2).

Table 2.

Inhibitor Susceptibilities of Ugandan Isolates With Different Haplotypes

| Median IC50 (nM (n)) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PfDHFR Haplotypesa | Nb | Pyrimethamine | Cycloguanil | Proguanil | P218 |

| 51I/108N | 22 | 30 200 (22) | 700 (4) | 24 500 (3) | 0.9 (22) |

| 51I/108N/59R | 312 | 41 800 (292) | 1200 (117) | 14 000 (111) | 0.6 (301) |

| 51I/108N/59R/164L | 47 | 101 700 (39) | 2100 (19) | 9200 (17) | 2.6 (44) |

| 51I/108N/59R/164Lmix | 35 | 53 900 (29) | 1500 (16) | 7400 (14) | 1.4 (33) |

| 51I/108N/59R/164Lpure | 12 | 129 500 (10) | 4700 (3) | 17 800 (3) | 5.7 (10) |

| 51I/108N/164L | 2 | 32 200 (2) | - | - | 1.9 (2) |

aIsolates with mixed and pure mutant haplotypes except where separated, as indicated with subscript, into mixed (164Lmix) or pure mutant (164Lpure) at codon 164.

bTotal number of isolates with each haplotype.

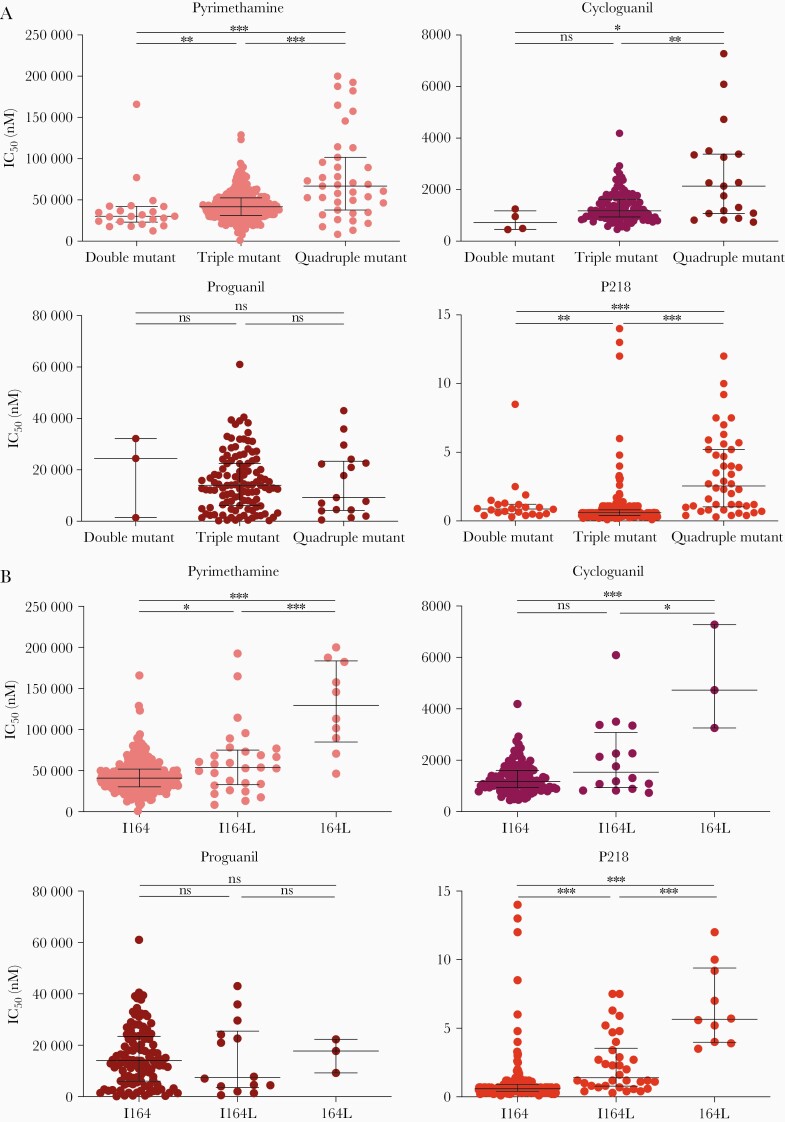

Decreased Susceptibility of Ugandan Isolates to PfDHFR Inhibitors Associated With Mutations in PfDHFR

Double, triple, and quadruple mutant pfdhfr genotypes have been associated with decreased susceptibility to pyrimethamine and cycloguanil [1, 25]. To examine associations in Ugandan isolates, we compared susceptibilities of parasites with different pfdhfr genotypes. For pyrimethamine and cycloguanil, susceptibility decreased with increasing numbers of PfDHFR mutations (Figure 2A, Table 2). For proguanil, no association was seen between genotypes and drug susceptibility. For P218, as noted above, all parasites were highly susceptible, but quadruple mutants had significantly lower susceptibilities than double or triple mutants. Compared with isolates with WT sequence at codon 164, those pure mutants at this codon had ~2.5-fold decreased susceptibility to pyrimethamine, ~5-fold decreased susceptibility to cycloguanil, and ~10-fold decreased susceptibility to P218; for all comparisons, quadruple mutant parasites with mixed I164L genotypes had intermediate drug susceptibilities (Figure 2B, Table 2). Of note, the 2 isolates that had a triple mutant genotype without the 59R mutation (51I/108N/164L haplotype) had similar susceptibilities to pyrimethamine as the double and triple mutants without the 164L mutation, and similar susceptibilities to P218 as the mixed quadruple mutant (Table 2).

Figure 2.

Associations between pfdhfr genotypes and susceptibilities to PfDHFR inhibitors. (A) Ex vivo susceptibilities to the tested inhibitors are shown for double (51I/108N), triple (51I/108N/59R), and quadruple (51I/108N/59R/164L) mutants with both mixed and pure genotypes. Horizontal bars show medians and interquartile ranges. (B) Ex vivo susceptibilities to the tested inhibitors are shown for isolates with wild-type (I164) or quadruple mutant haplotypes with either mixed (I164L) or pure mutant (164L) sequence at codon 164. Statistical analysis: Mann-Whitney U test: *, P < .05; **, P < .01; ***, P < .001. IC50, half-maximal inhibitory concentration; ns, not significant.

These data corroborate impacts of PfDHFR mutations on susceptibility to PfDHFR inhibitors [4] and demonstrate that these mutations impact also on susceptibility to P218, albeit with only modest decreases in susceptibility in quadruple mutant parasites.

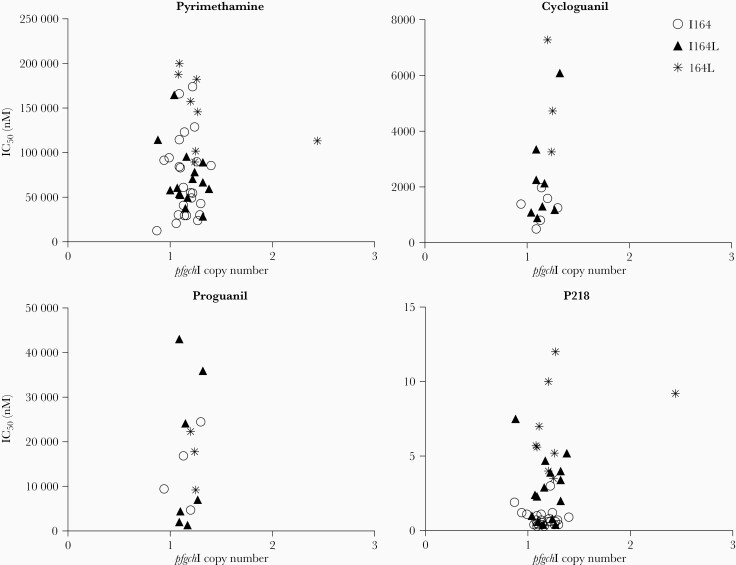

PfgchI Copy Number Was Not Associated With Drug Susceptibility or Specific Genotypes in Ugandan Isolates

Parasites carrying mutations in PfDHFR have a fitness disadvantage [26, 27]. To counteract this disadvantage, the parasite appears in some settings to increase copy number of the GTP cyclohydrolase I (pfgchI; PF3D7_1224000) gene, presumably to increase expression of the first enzyme in the folate synthesis pathway and thereby maximize flux through the pathway [22, 26, 28, 29]. Of 51 Ugandan isolates evaluated, one, a pure quadruple mutant, harbored 2 copies of pfgchI; this isolate had unremarkable susceptibilities to pyrimethamine and P218 (Figure 3). Control parasites had expected pfgchI copy numbers (D6, WT PfDHFR, 1 copy; Dd2, triple mutant PfDHFR, 2 copies; and V1/S, quadruple mutant PfDHFR, 4 copies). Although our analysis was limited by the scarcity of isolates with increased pfgchI copy number, the single isolate with 2 copies of pfgchI did not demonstrate IC50s remarkably different from those of the single copy isolates for pyrimethamine or P218.

Figure 3.

PfgchI copy numbers, inhibitor susceptibilities, and genotypes of Ugandan isolates. Each point represents a single isolate, and shapes indicate the genotype at codon 164: circles represent wild-type ([WT] I164), triangles represent mixed WT/mutant (I164L), and asterisks represent pure mutant (164L) parasites. IC50, half-maximal inhibitory concentration.

DISCUSSION

Point mutations in PfDHFR have been linked to P falciparum resistance to PfDHFR inhibitors [1]. To understand the impacts of PfDHFR polymorphisms in P falciparum circulating in Uganda on activities of PfDHFR inhibitors, we tested ex vivo susceptibilities to 4 compounds, pyrimethamine, cycloguanil, its prodrug proguanil, and the new inhibitor P218, and assessed associations between these susceptibilities and pfdhfr genotypes. We identified markedly decreased susceptibilities, compared with the 3D7 reference strain, to pyrimethamine, cycloguanil, and proguanil. In contrast, susceptibilities to P218 showed only modest differences between the reference strain and Ugandan isolates. More importantly, although parasites with quadruple PfDHFR mutations were significantly less susceptible to P218 than parasites with fewer mutations, even these parasites were susceptible at low nanomolar concentrations. Thus, P218 was highly active against all tested P falciparum genotypes circulating in Uganda.

Consistent with other recent reports [9, 10], the majority of the samples from Eastern Uganda were PfDHFR triple mutant parasites (51I/108N/59R), and the prevalence of quadruple mutant (51I/108N/59R/164L) parasites was approximately 13%. Considering that the prevalences of key mutations in PfDHPS, the target of sulfadoxine, were also high in recently studied Ugandan isolates [9, 10], these results have important policy implications. Antifolates are no longer recommended for the treatment of malaria, but the standard of care across Africa remains intermittent preventive therapy during pregnancy (IPTp) with SP. However, with high prevalence of PfDHFR mutations, the antimalarial protective efficacy of IPTp with SP is low [30, 31], and additional mutations are selected by use of SP [32]. In West Africa, where IPT with SP is recommended in children in Sierra Leone and monthly seasonal malaria chemoprevention with SP plus amodiaquine is widely used, the prevalence of key PfDHFR/PfDHPS mutations is lower than in East Africa, but increasing prevalence may similarly threaten the protective efficacies of SP-based regimens [33].

Mutations in PfDHFR are likely acquired stepwise and lead to a steady decrease in susceptibility [26, 34]. As expected, our results showed that the established PfDHFR inhibitors pyrimethamine and cycloguanil had limited activity against mutant Ugandan P falciparum isolates, with activity lowest against quadruple mutant parasites. Proguanil, which does not directly inhibit PfDHFR, but acts as a prodrug for cycloguanil, also showed poor activity against Ugandan isolates, although activity was not associated with the number of PfDHFR mutations, and the basis for resistance to proguanil is unknown. In light of the limited abilities of existing PfDHFR/PfDHPS inhibitors to treat or prevent malaria when multiple target mutations are present, it is encouraging that P218, a next-generation PfDHFR inhibitor, offered potent activity against mutant parasites.

Mutations in PfDHFR lead to structural changes in the protein, a prerequisite for decreased inhibitor binding [11]. The S108N mutation reduces binding affinity for pyrimethamine and cycloguanil, and the N51I and I164L substitutions additively decrease binding of the inhibitors by changing the conformation of the enzyme [12, 35]. P218 was designed to overcome resistance by including a flexible pyrimidine side-chain and a carboxylate group to form hydrogen bonds with the conserved D54 and R122 residues, respectively [14, 16]. Mutations at position D54 have not been observed in field isolates; mutagenesis experiments showed that mutation to any other amino acid reduced enzyme activity [36]. The 59R mutation favors formation of another stable bond with P218 [14, 16]. Thus, P218 was highly active against Ugandan double and triple mutant parasites. The binding of P218 is additionally stabilized by a hydrogen bond to residue I164, which is slightly weakened in the 164L mutant [16], consistent with the slight decrease in P218 susceptibility seen for Ugandan quadruple mutant isolates. However, unlike pyrimethamine, P218 binds primarily inside the dihydrofolate substrate pocket [14], leading to decreased impact of mutations on P218 sensitivity. The target-based design of P218, with a flexible side chain enabling inhibition of parasites with wild-type or mutant PfDHFR, has been extensively described and illustrated by Yuthavong et al [14] and recently reviewed [37]. Despite drug development complexities, the favorable drug qualities, antimalarial potency, and chemopreventive efficacy of P218 warrant further structure-based design of optimized PfDHFR inhibitors. In this regard, recent studies have focused on a hybrid inhibitor with dual binding to PfDHFR mutant and WT parasites and a fragment-based approach that identified 3 new chemotypes that target the PfDHFR active site [38, 39].

To overcome fitness costs associated with PfDHFR mutations, P falciparum can increase expression of the first enzyme of the folate pathway, PfGCHI [22, 26–29]. Previous studies in Southeast Asia found an association between presence of the PfDHFR 164L mutation and pfgchI amplification [29, 40]. Whole-genome analysis revealed high prevalence of pfgchI promoter amplification but not gene amplification in East African P falciparum samples [41]. We identified pfgchI gene amplification in 1 Ugandan isolate but no clear association between pfgchI amplification and pfdhfr genotype or decreased inhibitor susceptibility. At present, the relevance of pfgchI or promoter amplification in Ugandan P falciparum is unknown.

CONCLUSIONS

Our study provided comprehensive data on susceptibilities to PfDHFR inhibitors, genotypes of P falciparum currently circulating in Uganda, and associations between these phenotypes and genotypes. We noted generally poor activities of pyrimethamine and cycloguanil consistent with, as seen previously [9], very high prevalence of triple mutant parasites, and increasing prevalence of quadruple mutant parasites in eastern Uganda. However, it is reassuring that susceptibilities to P218 remained excellent, with the modest decreases in susceptibility seen with quadruple mutant parasites very unlikely to have clinical consequences. Thus, our data suggest caution regarding continued use of SP for malaria chemoprevention but confidence that novel PfDHFR inhibitors can circumvent resistance mechanisms present in parasites now circulating in Africa.

Notes

Acknowledgments. We thank study participants and staff members of the clinics where samples were collected.

Author contributions. O. K., P. K. T., T. K., M. O., O. B., S. O., and S. A. R. assisted in study design, performed ex vivo IC50 assays, and archived data. S. L. N., M. D., and J. L. provided project administrative and logistical support. O. K., S. A. R., M. D. C., O. A., and J. A. B. performed and analyzed genotyping studies. O. K. and R. A. C. verified and analyzed data and performed statistical analysis. O. K. and P. J. R. wrote a draft, and all authors contributed to writing of the final version of this manuscript.

Financial support. This work was funded by the National Institutes of Health (Grants R01AI139179 and R01AI075045) and the Medicines for Malaria Venture ([MMV] RD/15/0001).

Potential conflicts of interests. M. D. is employed by MMV, who is cofunding the work performed in this study. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

Presented in part: American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, November 2020, Virtual Presentation; Women in Malaria Conference, March 2021, virtual presentation.

Contributor Information

Oriana Kreutzfeld, University of California, San Francisco, California, USA.

Patrick K Tumwebaze, Infectious Diseases Research Collaboration, Kampala, Uganda.

Oswald Byaruhanga, Infectious Diseases Research Collaboration, Kampala, Uganda.

Thomas Katairo, Infectious Diseases Research Collaboration, Kampala, Uganda.

Martin Okitwi, Infectious Diseases Research Collaboration, Kampala, Uganda.

Stephen Orena, Infectious Diseases Research Collaboration, Kampala, Uganda.

Stephanie A Rasmussen, Dominican University of California, San Rafael, California, USA.

Jennifer Legac, University of California, San Francisco, California, USA.

Melissa D Conrad, University of California, San Francisco, California, USA.

Sam L Nsobya, Infectious Diseases Research Collaboration, Kampala, Uganda.

Ozkan Aydemir, Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island, USA.

Jeffrey A Bailey, Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island, USA.

Maelle Duffey, Medicines for Malaria Venture, Geneva, Switzerland.

Roland A Cooper, Dominican University of California, San Rafael, California, USA.

Philip J Rosenthal, University of California, San Francisco, California, USA.

References

- 1. Peterson DS, Milhous WK, Wellems TE. Molecular basis of differential resistance to cycloguanil and pyrimethamine in Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1990; 87:3018–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. World Health Organization. WHO Guidelines for malaria. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Malaria: How to choose a drug to prevent Malaria. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/malaria/travelers/drugs.html. Accessed 20 May 2021.

- 4. Gregson A, Plowe CV. Mechanisms of resistance of malaria parasites to antifolates. Pharmacol Rev 2005; 57:117–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kiara SM, Okombo J, Masseno V, et al. In vitro activity of antifolate and polymorphism in dihydrofolate reductase of Plasmodium falciparum isolates from the Kenyan coast: emergence of parasites with Ile-164-Leu mutation. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2009; 53:3793–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Peterson DS, Milhous WK, Wellems TE. Molecular basis of differential resistance to cycloguanil and pyrimethamine in Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1990; 87:3018–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Naidoo I, Roper C. Mapping ‘partially resistant’, ‘fully resistant’, and ‘super resistant’ malaria. Trends Parasitol 2013; 29:505–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lynch C, Pearce R, Pota H, et al. Emergence of a dhfr mutation conferring high-level drug resistance in Plasmodium falciparum populations from southwest Uganda. J Infect Dis 2008; 197:1598–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Asua V, Conrad MD, Aydemir O, et al. Changing prevalence of potential mediators of aminoquinoline, antifolate, and artemisinin resistance across Uganda. J Infect Dis 2021; 223:985–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Asua V, Vinden J, Conrad MD, et al. Changing molecular markers of antimalarial drug sensitivity across Uganda. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2019; 63:e01818-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yuthavong Y, Yuvaniyama J, Chitnumsub P, et al. Malarial (Plasmodium falciparum) dihydrofolate reductase-thymidylate synthase: structural basis for antifolate resistance and development of effective inhibitors. Parasitology 2005; 130:249–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Yuvaniyama J, Chitnumsub P, Kamchonwongpaisan S, et al. Insights into antifolate resistance from malarial DHFR-TS structures. Nat Struct Biol 2003; 10:357–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Peterson DS, Walliker D, Wellems TE. Evidence that a point mutation in dihydrofolate reductase thymidylatesynthase confers resistance to pyrimethamine in falciparum malaria. Proc Natl Acad Sci 1988; 85:9114– 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yuthavonga Y, Tarnchompooa B, Vilaivanb T, et al. Malarial dihydrofolate reductase as a paradigm for drug development against a resistance-compromised target. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012; 109:16823–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tse EG, Korsik M, Todd MH. The past, present and future of anti-malarial medicines. Malar J 2019; 18:93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Abbat S, Jain V, Bhartam PV. Origin of the specificity of inhibitor P218 towards wild-type and mutant PfDHFR: a molecular dynamics analysis. J Biomol Struct Dyn 2015; 33:1913–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chughlay MF, Rossignol E, Donini C, et al. First-in-human clinical trial to assess the safety, tolerability and pharmacokinetics of P218, a novel candidate for malaria chemoprotection. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2020; 86:1113–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chughlay MF, El Gaaloul M, Donini C, et al. Chemoprotective antimalarial activity of P218 against Plasmodium falciparum: a randomized, placebo-controlled volunteer infection study. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2021; 104:1348–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tumwebaze PK, Katairo T, Okitwi M, et al. Drug susceptibility of Plasmodium falciparum in eastern Uganda. Lancet Microbe 2021; 2:e441–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zhang JH, Chung TD, Oldenburg KR. A simple statistical parameter for use in evaluation and validation of high throughput screening assays. J Biomol Screen 1999; 4:67–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Aydemir O, Janko M, Hathaway NJ, et al. Drug-resistance and population structure of Plasmodium falciparum across the Democratic Republic of Congo using high-throughput molecular inversion probes. J Infect Dis 2018; 218:946–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Heinberg A, Siu E, Stern C, et al. Direct evidence for the adaptive role of copy number variation on antifolate susceptibility in Plasmodium falciparum. Mol Microbiol 2013; 88:702–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Dorsey G, Dokomajilar C, Kiggundu M, Staedke SG, Kamya MR, Rosenthal PJ. Principal role of dihydropteroate synthase mutations in mediating resistance to sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine in single-drug and combination therapy of uncomplicated malaria in Uganda. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2004; 71:758–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tumwebaze P, Tukwasibwe S, Taylor A, et al. Changing antimalarial drug resistance patterns identified by surveillance at three sites in Uganda. J Infect Dis 2017; 215:631–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Basco LK, de Pécoulas PE, Wilson CM, Le Bras J, Mazabraud A. Point mutations in the dihydrofolate reductase-thymidylate synthase gene and pyrimethamine and cycloguanil resistance in Plasmodium falciparum. Mol Biochem Parasitol 1995; 69:135–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kümpornsin K, Modchang C, Heinberg A, et al. Origin of robustness in generating drug-resistant malaria parasites. Mol Biol Evol 2014; 31:1649–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Brown KM, Costanzo MS, Xu W, Roy S, Lozovsky ER, Hartl DL. Compensatory mutations restore fitness during the evolution of dihydrofolate reductase. Mol Biol Evol 2010; 27:2682–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kidgell C, Volkman SK, Daily J, et al. A systematic map of genetic variation in Plasmodium falciparum. PLoS Pathog 2006; 2:e57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Nair S, Miller B, Barends M, et al. Adaptive copy number evolution in malaria parasites. PLoS Genet 2008; 4:e1000243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kajubi R, Ochieng T, Kakuru A, et al. Monthly sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine versus dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine for intermittent preventive treatment of malaria in pregnancy: a double-blind, randomised, controlled, superiority trial. Lancet 2019; 393:1428–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kakuru A, Jagannathan P, Muhindo MK, et al. Dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine for the prevention of malaria in pregnancy. N Engl J Med 2016; 374:928–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Nayebare P, Asua V, Conrad MD, et al. Associations between malaria-preventive regimens and Plasmodium falciparum drug resistance-mediating polymorphisms in Ugandan pregnant women. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2020; 64:e01047–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Partnership A-S. Effectiveness of seasonal malaria chemoprevention at scale in West and Central Africa: an observational study. Lancet 2020; 396:1829–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lozovsky ER, Chookajorn T, Brown KM, et al. Stepwise acquisition of pyrimethamine resistance in the malaria parasite. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009; 106:12025–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kamchonwongpaisan S, Quarrell R, Charoensetakul N, et al. Inhibitors of multiple mutants of Plasmodium falciparum dihydrofolate reductase and their antimalarial activities. J Med Chem 2004; 47:673–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sirawaraporn W, Sirawaraporn R, Yongkiettrakul S, et al. Mutational analysis of Plasmodium falciparum dihydrofolate reductase: the role of aspartate 54 and phenylalanine 223 on catalytic activity and antifolate binding. Mol Biochem Parasitol 2002; 121:185–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Calic PPS, Mansouri M, Scammells PJ, McGowan S. Driving antimalarial design through understanding of target mechanism. Biochem Soc Trans 2020; 48:2067–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hoarau M, Vanichtanankul J, Srimongkolpithak N, Vitsupakorn D, Yuthavong Y, Kamchonwongpaisan S. Discovery of new non-pyrimidine scaffolds as Plasmodium falciparum DHFR inhibitors by fragment-based screening. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem 2021; 36:198–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Tarnchompoo B, Chitnumsub P, Jaruwat A, et al. Hybrid inhibitors of malarial dihydrofolate reductase with dual binding modes that can forestall resistance. ACS Med Chem Lett 2018; 9:1235–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sugaram R, Suwannasin K, Kunasol C, et al. Molecular characterization of Plasmodium falciparum antifolate resistance markers in Thailand between 2008 and 2016. Malar J 2020; 19:107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Turkiewicz A, Manko E, Sutherland CJ, Diez Benavente E, Campino S, Clark TG. Genetic diversity of the Plasmodium falciparum GTP-cyclohydrolase 1, dihydrofolate reductase and dihydropteroate synthetase genes reveals new insights into sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine antimalarial drug resistance. PLoS Genet 2020; 16:e1009268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]