Abstract

Little is known regarding coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccination rates in people with HIV (PWH), a vulnerable population with significant morbidity from COVID-19. We assessed COVID-19 vaccination rates among 6952 PWH in the Randomized Trial to Prevent Vascular Events in HIV (REPRIEVE) compared to region- and country-specific vaccination data. The global probability of COVID-19 vaccination through end of July 2021 was 55% among REPRIEVE participants with rates varying substantially by Global Burden of Disease (GBD) superregion. Among PWH, factors associated with COVID-19 vaccination included residence in high-income regions, age, white race, male sex, body mass index, and higher cardiovascular risk.

Clinical Trials Registration. NCT02344290.

Keywords: human immunodeficiency virus, COVID-19, vaccination, Global Burden of Disease region

Globally, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has taken the lives of more than 4.5 million people [1]. People with human immunodeficiency virus (PWH) are immunocompromised and have a higher risk of underlying comorbidities, placing them at high risk of COVID-related morbidity and mortality [2, 3]. However, little is known regarding global vaccination rates in this high-risk population. The Randomized Trial to Prevent Vascular Events (REPRIEVE) is a global primary cardiovascular prevention trial among PWH [4]. Data collected on COVID-19 vaccination rates in REPRIEVE afford a unique opportunity to assess such rates among PWH across global regions. Here we compare region- and country-specific vaccination rates among PWH enrolled in REPRIEVE to rates among the general population and assess, among PWH, characteristics associated with vaccination.

METHODS

The study was approved by the Mass General Brigham Human Research Committee and by the local institutional review boards of each site. Informed consent was obtained in writing from each participant. Race and ethnicity were self-reported using previously described National Institutes of Health definitions [5].

Vaccination Data

Vaccination was defined as at least 1 dose of any COVID-19 vaccine. REPRIEVE vaccination data were collected on the concomitant medication log updated at each study visit scheduled quarterly. The cumulative probability of vaccination was determined from monthly data between January 2021 and the end of July 2021 using Kaplan-Meier estimation. Participants without vaccination were censored at date of last contact. Comparison of targeted baseline characteristics, including age, race, natal sex, body mass index (BMI), atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk score by the 2013 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association pooled cohort equation [6], CD4 (nadir and baseline), duration of antiretroviral therapy (ART), and history of AIDS-defining illness associated with vaccination status was made via visual examination of the Kaplan-Meier curves and formally compared via log-rank tests. Because REPRIEVE is a large study with high power to detect small differences, conclusions were motivated by clinically meaningful effect sizes.

Vaccination rates among REPRIEVE participants were compared between Global Burden of Disease (GBD) superregions (high-income [United States, Canada, Spain], Latin America and Caribbean [Brazil, Haiti, Peru, Puerto Rico], Southeast/East Asia [Thailand], South Asia [India], Sub-Saharan Africa [Botswana, South Africa, Uganda, Zimbabwe]) and with country-specific vaccination rates among the general population, derived from public databases, including Our World in Data (OWD) [1], World Bank [7], and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) [8]. Note, the countries included for analysis represent only a subset of the GBD superregions. The OWD dataset is open access and aggregates country-specific data from governmental databases, including the World Health Organization (WHO) and the CDC, and is updated daily by employees of OWD. Data establishing background vaccination rates from the OWD database were compared to publicly available country-specific data from the WHO, showing significant concordance (see Supplementary Table 1 for sources of OWD data and comparison of country-specific data to WHO). For the United States, country-specific vaccination rates among individuals aged 40–74 years were obtained from public datasets from the CDC [8] for comparison against rates among REPRIEVE participants of comparable age. For other countries, public data were more limited, but we were able to determine rates among the population of individuals aged 15 years or older, to infer an eligible population for comparison. Overall population size for each country, as well as adult population 15 years of age and older was collected from the World Bank database. We utilized data on at least 1 vaccination given the multiplicity of regimens across regions and countries (Supplementary Table 2), to best harmonize the data and most accurately reflect vaccine rates over a given time period. Comparisons with public datasets used this same metric.

RESULTS

Study Population

In total, 7770 male and female PWH, aged 40–75 years, on stable ART, without known cardiovascular disease, and low-to-moderate ASCVD risk, were recruited into REPRIEVE [4]. Enrollment occurred between March 2015 and July 2019 in 12 countries. COVID-19 vaccination rates were determined in 6952 participants active in REPRIEVE as of 1 January 2021 (Supplementary Table 3), including participants in Brazil (n = 1042), Botswana (n = 273), Canada (n = 123), Haiti (n = 136), India (n = 469), Peru (n = 142), South Africa (n = 527), Spain (n = 198), Thailand (n = 582), Uganda (n = 175), the United States (n = 3162), and Zimbabwe (n = 123).

Cumulative Vaccination Rates Among REPRIEVE Participants

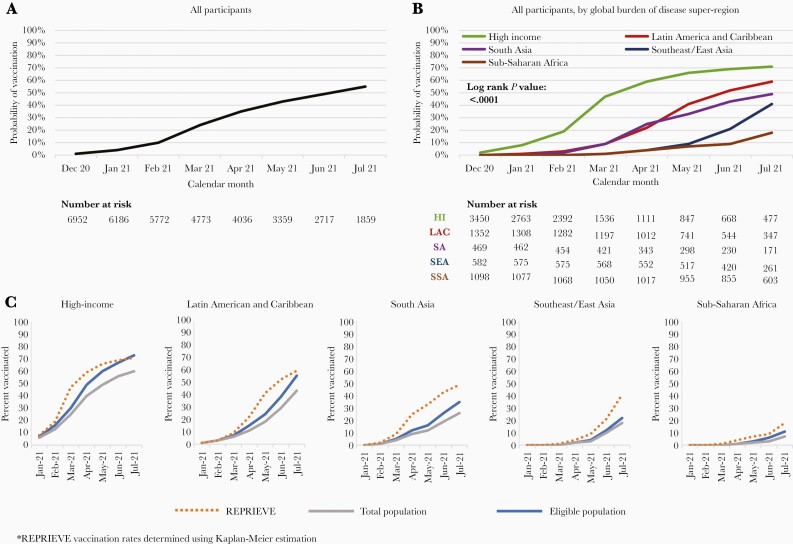

The cumulative vaccination rate among REPRIEVE participants through the end of July 2021 was 55% (Figure 1A), although rates varied substantially by GBD superregion and by country (Figure 1B and Supplementary Figure 1). Cumulative vaccination rates were highest in the high-income superregion (71%), followed by Latin America and the Caribbean (59%), South Asia (49%), Southeast/East Asia (41%), and Sub-Saharan Africa (18%). Country-specific rates varied dramatically, with vaccination rates highest in the United States, Peru, and Brazil at 72%, 69%, and 63%, and lowest in South Africa, Uganda, and Haiti at 18%, 3%, and 0%, respectively.

Figure 1.

Vaccination rates among Randomized Trial to Prevent Vascular Events in HIV (REPRIEVE) participants and the general population. A, Kaplan-Meier curve depicting probability of vaccination among REPRIEVE participants through July 2021. B, Kaplan-Meier curve depicting probability of vaccination among REPRIEVE participants by Global Burden of Disease (GBD) superregion. C, Comparisons of vaccination rates between people with HIV in REPRIEVE and the general and eligible populations among GBD superregions.

Comparison to Vaccination Rates Among the General Population

Vaccination rates were generally comparable among PWH in REPRIEVE compared to the general population in most GBD superregions (Figure 1C), although key differences were observed in comparison to the general population in specific countries (Supplementary Figure 1).

Characteristics Associated With Vaccination Among REPRIEVE Participants

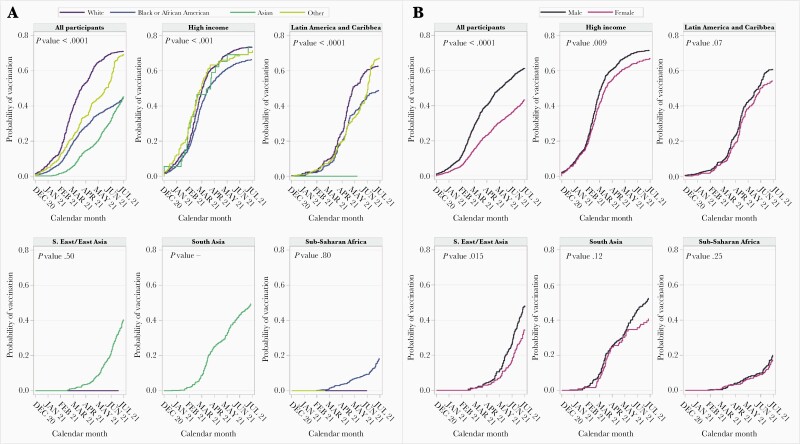

Among the overall REPRIEVE population, vaccinated participants were more likely to come from high-income GBD superregion countries and to be white, male, older, have a higher BMI, higher ASCVD risk score, and longer duration of ART, but did not differ by either nadir or baseline CD4 count (Supplementary Figures 2–8). Vaccination rates were overall higher among men in the high-income and the Southeast/East Asia regions with similar trends in Latin America and the Caribbean and South Asia. In the high-income GBD superregion, differences in vaccination rates by race were seen (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Cumulative probability of vaccination over time among Randomized Trial to Prevent Vascular Events in HIV (REPRIEVE) participants by race and sex. A, Vaccination rates among Global Burden of Disease (GBD) superregions by race. B, Vaccination rates among each GBD superregion by sex. Participants with no follow-up in 2021 are censored at 1 January 2021. X-axis tick marks indicate the end of a given month.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this analysis presents the first and largest investigation of vaccination rates among PWH. Among REPRIEVE participants, vaccination rates were greatest in high-income countries compared to low-income countries. For example, overall vaccine rates for PWH in REPRIEVE ranged from 71% in the high-income superregion to 18% in Sub-Saharan Africa, and by country from 72% in the United States to 0% in Haiti. Overall, vaccination rates mirrored rates for the general population in most GBD superregions, with specific differences seen in individual countries. These data allow a specific examination of rates among PWH, in the context of global rollout policies that differed by region and country (see Supplementary Table 2 for summary of country specific roll-out timelines). Moreover, these data permitted an examination of factors associated with COVID-19 vaccination for the first time among PWH.

Our data highlight major differences in COVID-19 across GBD superregions. Furthermore, our data demonstrate that COVID-19 vaccination rates among PWH are consistent with the general population in many regions and countries. This disparity in COVID-19 vaccination rates among PWH across income regions may increase morbidity from COVID-19 in the most vulnerable human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) populations. For example, the 2 countries with the largest share of deaths from HIV/AIDS (Botswana and South Africa) [9] demonstrated very low vaccination rates in general compared to high-income countries.

In our cohort, vaccinated PWH were more likely to be older, have more comorbidities, including higher BMI, and higher overall ASCVD risk, across most regions. Increased comorbidities among those receiving the vaccine may suggest that such participants were motivated out of concerns about COVID-related morbidity/mortality, and/or that physicians recommended the vaccination more often in this context, consistent with many public health recommendations [10]. Overall, women were less likely to receive the vaccination in high-income regions and Southeast/East Asia, with similar trends in most regions except Sub-Saharan Africa.

In the high-income superregion, with a significant representation of participants from the United States, vaccination rates were higher among whites than blacks. These data confirm lower vaccination rates for people of color living with HIV globally, for example in sub-Saharan Africa and Haiti, and also compared to whites within higher GBD superregions such as the United States [11]. Given data for higher morbidity from COVID-19 among people of color with HIV [2], this disparity is likely to have significant public health implications.

Our analysis was characterized by strengths and limitations. We established region and country-specific rates in a diverse, global population of PWH, with 66% people of color and 32% women. Given the design and data collected in REPRIEVE, we were able to assess vaccination rates in association with key demographics and well-established cardiovascular risk metrics. Vaccination rates for the general population were calculated for most countries and in most regions in a broadly defined eligible population (≥ 15 years of age), given data availability. For the large REPRIEVE population in the United States, we were able to compare to the general population aged 40–74 years. REPRIEVE participants were recruited as part of a large, multinational, primary ASCVD prevention trial and are representative of the global population of PWH on ART [12]. Decisions on vaccination were made by the individual participants in REPRIEVE, without a central recommendation or requirement from the study. Although participants were enrolled in a research cohort, the study population is reflective of a highly relevant global population of PWH, for whom vaccination data are critical. Moreover, the uniform study conditions and assessments in the cohort permitted determination of global rates and key comparisons across GBD regions. In this context, we observed tremendous differences in rates and key factors associated with vaccination across GBD regions, providing the first such data on PWH. Collection of COVID-19 vaccination data is ongoing in REPRIEVE. Future data collection will allow for further refinement of cumulative rates and examination of evolving COVID-19 vaccination patterns.

These data from REPRIEVE inform the field on the critical question of COVID-19 vaccination rates among PWH and highlight inequities in vaccination rates across GBD superregions. Furthermore, the data highlight subgroups among the larger global population of PWH who have low vaccine rates and should be targeted for vaccination.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at The Journal of Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Notes

Acknowledgments. The study investigators thank the study participants, site staff, and study-associated personnel for their ongoing participation in the trial. For a list of site Principal Investigators, please see Supplementary Table 4. In addition, we thank the following: the AIDS Clinical Trial Group (ACTG) for clinical site support; ACTG Clinical Trials Specialists for regulatory support; the data management center, Frontier Science Foundation, for data support; and the Center for Biostatistics in AIDS Research for statistical support.

Disclaimer . The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) or the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, the National Institutes of Health (NIH), or the Department of Health and Human Services.

Data sharing. Data will be shared in accordance with NIH policy.

Financial support. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant numbers U01HL123336 to the Clinical Coordinating Center, and U01HL123339 to the Data Coordinating Center); Kowa Pharmaceuticals; Gilead Sciences; Viiv; the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (grant numbers UM1 AI068636 to the ACTG Leadership and Operations Center, and UM1 AI106701 to the ACTG Laboratory Center); and National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (grant number P30DK 040561 to S. K. G.

Potential conflicts of interest. K. V. F. reports receiving an educational grant from Gilead, unrelated to this work. E. T. O. reports research funding to their institution from Gilead, ViiV Healthcare, and GSK; has been a paid consultant to Merck, ViiV Healthcare, and Theratechnologies; serves as chair of the Comorbidity Transformational Science Group for the NIH-funded ACTG, and is a member of the Scientific Review Committee for the NIH-funded HVTN unrelated to this work. M. V. Z. reports grant support through her institution from Gilead Sciences for the conduct of the study. J. A. A. reports institutional research support for clinical trials from Atea, Emergent Biosolutions, Frontier Technologies, Gilead Sciences, Glaxo Smith Kline, Janssen, Merck, Pfizer, Regeneron, and Viiv Healthcare; and personal fees for advisory boards from Glaxo Smith Kline and Merck, all outside the submitted work. M. T. L. reports research funding to their institution from AstraZeneca and MedImmune, unrelated to this work. C. M. reports personal fees from ViiV Healthcare and Gilead Sciences for participation in advisory board meetings unrelated to this work. C. J. F. reports grants from ViiV Healthcare, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Merck, CytoDyn, Amgen, Gilead, and Abbvie unrelated to this work. E. M. reports funding paid to their institution from Merck and ViiV Healthcare for research studies, and funding paid to them for educational activities and advisory boards from Janssen, Gilead Sciences, Merck, and ViiV Healthcare unrelated to this work. T. U. reports grants from the NIH/National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, the NIH/National Institute on Aging, and Kowa Pharmaceuticals paid to their institution unrelated to this work. H. J. R. reports grants from the NIH/National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and from the NIH/ NHLBI unrelated to this work. S. K. G. reports consulting fees from Viiv, Navidea, and Theratechnologies unrelated to this work. All other authors report no potential conflicts.

All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

Contributor Information

Evelynne S Fulda, Metabolism Unit, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

Kathleen V Fitch, Metabolism Unit, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

Edgar T Overton, Division of Infectious Diseases, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, Alabama, USA.

Markella V Zanni, Metabolism Unit, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

Judith A Aberg, Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, New York, USA.

Judith S Currier, Division of Infectious Diseases, University of California at Los Angeles, Los Angeles, California, USA.

Michael T Lu, Cardiovascular Imaging Research Center, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

Carlos Malvestutto, Division of Infectious Diseases, The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus, Ohio, USA.

Carl J Fichtenbaum, Department of Medicine for Translational Research, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, Ohio, USA.

Esteban Martinez, Hospital Clinic and University of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain.

Triin Umbleja, Center for Biostatistics in AIDS Research, Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

Pamela S Douglas, Duke Clinical Research Institute, Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, North Carolina, USA.

Heather J Ribaudo, Center for Biostatistics in AIDS Research, Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

Steven K Grinspoon, Metabolism Unit, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

References

- 1. Ritchie H, Mathieu E, Rodés-Guirao L, et al. Coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19). https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus. Accessed September 2, 2021.

- 2. Bhaskaran K, Rentsch CT, MacKenna B, et al. HIV infection and COVID-19 death: a population-based cohort analysis of UK primary care data and linked national death registrations within the OpenSAFELY platform. Lancet HIV 2021; 8:e24–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Childs K, Post FA, Norcross C, et al. Hospitalized patients with COVID-19 and human immunodeficiency virus: a case series. Clin Infect Dis 2020; 71:2021–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Grinspoon SK, Fitch KV, Overton ET, et al. ; REPRIEVE Investigators. Rationale and design of the Randomized Trial to Prevent Vascular Events in HIV (REPRIEVE). Am Heart J 2019; 212:23–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Douglas PS, Umbleja T, Bloomfield GS, et al. Cardiovascular risk and health among people with HIV eligible for primary prevention: insights from the REPRIEVE trial [published online ahead of print 16 June 2021]. Clin Infect Dis doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Goff DC Jr, Lloyd-Jones DM, Bennett G, et al. ; American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the assessment of cardiovascular risk: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2014; 129:S49–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. The World Bank. World Bank open data. https://data.worldbank.org/. Accessed September 2, 2021.

- 8. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID-19 vaccination demographics in the United States, National. https://data.cdc.gov/Vaccinations/COVID-19-Vaccination-Demographics-in-the-United-St/km4m-vcsb. Accessed September 2, 2021.

- 9. Roser M, Ritchie H. Our World in Data HIV/AIDS. https://ourworldindata.org/hiv-aids. Accessed September 2, 2021.

- 10. World Health Organization (WHO). WHO SAGE roadmap for prioritizing uses of COVID-19 vaccines in the context of limited supply. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Strully KW, Harrison TM, Pardo TA, Carleo-Evangelist J. Strategies to address COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and mitigate health disparities in minority populations. Front Public Health 2021; 9:645268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fichtenbaum CJ, Ribaudo HJ, Leon-Cruz J, et al. ; REPRIEVE Investigators. Patterns of antiretroviral therapy use and immunologic profiles at enrollment in the REPRIEVE trial. J Infect Dis 2020; 222:S8–S19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.