Abstract

Introduction

Thromboprophylaxis following total hip and knee arthroplasty is variable across institutions, but commonly consists of enoxaparin, and more recently rivaroxaban. We aimed to analyze the current evidence on the efficacy, safety and cost-effectiveness of rivaroxaban versus enoxaparin for thromboprophylaxis following TKA or THA.

Methods

This study was conducted according to PRISMA guidelines. Electronic database searches were performed using three databases from their dates of inception to June 2020. Relevant randomized controlled studies were identified, with data extracted and analyzed.

Results

From eight studies, 13,384 patients were included, with 5700 undergoing TKA and 7684 undergoing THA. There were 6629 patients receiving rivaroxaban and 6755 patients receiving enoxaparin. From the total cohort, rivaroxaban was associated with significantly lower rates of major VTE (p = 0.009) and DVT (p < 0.001) when compared to enoxaparin. There was no significant difference in bleeding complications between rivaroxaban and enoxaparin groups (p = 0.14). Subgroup analysis of patients undergoing THA demonstrated that rivaroxaban reduced risk of major VTE (p = 0.002) and DVT (p = 0.01) with no significant differences in any other complications. For those undergoing TKA, rivaroxaban significantly reduced the risk of DVT (p < 0.001) but was associated with higher rates of post-operative blood transfusion (p = 0.03). Cost-analysis revealed that rivaroxaban was superior to enoxaparin, with the medication cost needed to prevent one DVT being $1081 and $432 less with rivaroxaban for THA and TKA respectively

Conclusions

Rivaroxaban may be a safe and cost-effective alternative to enoxaparin for routine thromboprophylaxis following total knee or hip arthroplasty.

Keywords: Rivaroxaban, Enoxaparin, Cost, DVT, VTE, Embolism, Thromboprophylaxis

1. Introduction

Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) and total hip arthroplasty (THA) are becoming increasingly common in the developed world.1 They are highly effective operations that treat osteoarthritis of the knee and hip. However, patients undergoing these major orthopaedic operations are at increased risk of sustaining a venous thromboembolism, which can manifest as a deep vein thrombosis (DVT) or pulmonary embolism (PE).2

Worldwide, there is an estimated 1.6 million patients who are affected by VTE. Without any form of VTE prophylaxis, it has been shown that up to 60% of patients will sustain a VTE following major orthopaedic surgery.2, 3, 4 This has a significant impact on patient mortality and morbidity, as evidenced by the increased rates of wound complications, re-operation and prolonged hospital admissions.5,6 These post-operative complications also place a considerable economic burden on the healthcare system. In 2008, it was estimated that in Australia and New Zealand, VTEs cost an estimated $1.7 billion to the healthcare system.7 These costs can be as high as $10 billion a year in the United States to treat approximately 400,000 newly diagnosed VTE-related events.8

The pharmacological thromboprophylaxis regime following TKA and THA is variable across institutions, but commonly consists of low molecular weight heparin (e.g. enoxaparin) and more recently, direct factor Xa inhibitors (e.g. rivaroxaban). Rivaroxaban is increasingly being used across many countries as it has the advantage of being an oral therapy that requires no active monitoring. However, there is evidence that suggests that thromboprophylaxis with enoxaparin has a safer profile with a reduced risk of bleeding. This is particularly important as rivaroxaban has no effective and widely available reversal agent if major bleeding were to occur.9 Thus, it is important to balance the efficacy of these drugs in preventing VTEs with potential complications such as major bleeding. While there is a growing body of evidence regarding the clinical efficacy and safety profiles of various agents for thromboprophylaxis, the optimal agent of choice remains controversial.

Therefore, the aim of this current study was two-fold. The first was to synthesize and analyze the current evidence on the efficacy and safety of rivaroxaban versus enoxaparin for thromboprophylaxis following TKA or THA. Second, we aimed to perform a cost-analysis of thromboprophylactic medications used to prevent VTE-related events.

2. Methods

2.1. Search strategy

The study was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses guidelines (PRISMA).10 Electronic database searches were performed using Ovid Medline, PubMed and Cochrane CENTRAL from their dates of inception to June 2020. Using Boolean operators, the searches combined terms for pulmonary embolism, deep vein thrombosis, rivaroxaban, enoxaparin, total hip/knee arthroplasty and their abbreviations. The search was limited to human subjects and publications in the English language. Additionally, reference lists of included studies were further hand-searched for identification of potentially relevant studies.

2.2. Selection criteria

Eligible studies for this meta-analysis included patients receiving either enoxaparin or rivaroxaban for thromboprophylaxis following TKA or THA. Inclusion criteria were two-arm randomised controlled trials in patients over 18 years old undergoing elective TKA or THA. These studies were required to report complications including mortality, VTE, PE, DVT, bleeding events, requirement for transfusion, wound complications and need for re-admission.

All publications included were limited to those in the English language and involving human subjects. Conference presentations, case reports, reviews, editorials, and expert opinions were excluded.

2.3. Data extraction and critical appraisal

All the relevant data was extracted from the article text, figures and tables. Two investigators (J.X and D.C) independently reviewed and extracted data from the retrieved articles. Discrepancies between the two reviewers were resolved by discussion with senior authors to reach a consensus. The study characteristics extracted include study year, country, number of patients undergoing TKA or THA, along with number of patients received rivaroxaban or enoxaparin. Baseline data such as gender, age, BMI, past VTE and dosing regimen of rivaroxaban and enoxaparin were also extracted. Complications included major bleeding, any bleeding, transfusion, PE, DVT, major VTE (symptomatic PE or DVT), reoperation, wound complication and death. Major bleeding was defined as bleeding that was fatal, resulting in a fall of haemoglobin >20 g/L, requiring transfusion of >2 units of whole blood, or symptomatic in a critical area (intracranial, intraspinal, intraocular, retroperitoneal, intra-articular, pericardial or intramuscular with compartment syndrome).

2.4. Cost analysis

The average difference in cost for a full regimen of thromboprophylaxis with rivaroxaban and enoxaparin was calculated based on data obtained from the Australian Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS). The cost difference was determined, and cost analyses were conducted for all patients, and those undergoing only TKA and only THA. The corresponding number needed to treat (NNT) for efficacy outcomes was determined, in order to compare the cost required to prevent one VTE.

2.5. Statistical analysis

Review Manager version 5.3 software (Cochrane Collaboration, Software Update, Oxford, UK) was used to calculate 95% confidence intervals and relative risk ratios for efficacy and safety outcomes. Heterogeneity among studies was considered low when I2 values were <25%, and high when >50%. Relative risk was the primary summary statistic used for dichotomous outcomes. Random effects model was used in all cases due to its more conservative estimates and inherent differences in patient and surgical characteristics between studies.

3. Results

3.1. Search results

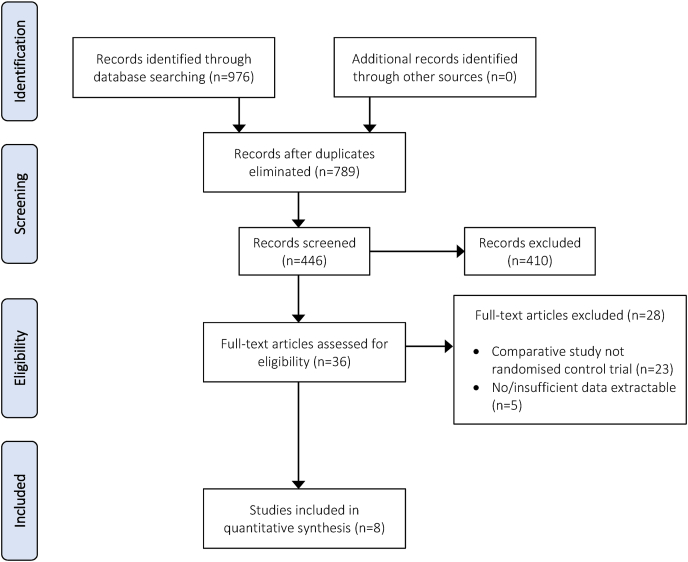

A total of 976 studies were identified according to the search strategy. By examining the study abstracts and removing duplicates 530 studies were excluded leaving 446 potentially relevant articles. After application of the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 8 randomized controlled trials comparing rivaroxaban and enoxaparin for thromboprophylaxis were deemed eligible (Fig. 1).11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18 Manual searching of references in each of the full-text articles did not yield further studies for inclusion.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow chart of systematic review assessing the efficacy and safety of enoxaparin vs rivaroxaban thromboprophylaxis.

3.2. Baseline characteristics

A total of 13,384 patients, with 5700 undergoing TKA and 7684 undergoing THA, were extracted from 8 studies. From these studies, 6629 received rivaroxaban and 6755 received enoxaparin. The median patient age was 70.9 years (range: 63–79 years). The proportion of females in the rivaroxaban group was 60.8% (range: 55.2–70.2%) and in the enoxaparin group was 59.3% (range: 52.9–66.3%). The dosing of rivaroxaban ranged from 10 mg once daily to twice daily for 5–39 days. The dosing of enoxaparin ranged from 30 to 40 mg either once daily or twice daily for 5–39 days. The follow-up time ranged from 9 to 75 days. The study characteristics are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of characteristics and demographics of studies.

| Author | Year | Study period | Country | Study type | Surgery |

Intervention |

No. female |

Age (range) - years |

BMI (range) - kg/m2 |

Dosing |

Duration post-op - days |

Follow-up | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TKA | THA | Riv | Enox | Riv | Enox | Riv | Enox | Riv | Enox | Riv | Enox | Riv | Enox | ||||||

| Turpie | 2005 | 2004 | Canada/USA | RCT | 207 | – | 103 | 104 | 66 | 57 | 67 (49–84) | 66 (47–83) | 31.8 | 31.8 | 10 mg BD | 30 mg BD | 5 to 9 | 5 to 9 | up to 60 days |

| Eriksson (1) | 2006 | 2004 | Europe | RCT | – | 265 | 133 | 132 | 80 | 78 | 65 (43–93) | 65 (27–82) | 27 (19–41) | 28 (20–40) | 10 mg BD | 40 mg OD | 5 to 9 | 5 to 9 | 9 days |

| Eriksson (2) | 2006 | 2004/2005 | Europe | RCT | – | 299 | 142 | 157 | 89 | 101 | 64 (27–87) | 66 (30–89) | 26.9 (18–49) | 27 (16–39) | 10 mg OD | 40 mg OD | 5 to 9 | 5 to 9 | 9 days |

| Eriksson | 2007 | 2003 | Europe | RCT | – | 230 | 68 | 162 | 22 | 88 | 65 (39–89) | 64 (30–92) | 27 (21–44) | 28 (19–44) | 10 mg BD | 40 mg OD | 5 to 9 | 5 to 9 | 9 days |

| Eriksson | 2008 | 2006 | Worldwide | RCT | – | 4433 | 2209 | 2224 | 1220 | 1242 | 63 (18–91) | 63 (18–93) | 27.8(16–53) | 27.9 (15–50) | 10 mg OD | 40 mg OD | 35 | 35 | 70 days |

| Kakkar | 2008 | 2006 | Worldwide | RCT | – | 2457 | 1228 | 1229 | 667 | 651 | 61 (18–93) | 62 (19–93) | 26.8 (16–55) | 27.1 (16–50) | 10 mg OD | 40 mg OD | 39 | 39 | up to 75 days |

| Lassen | 2008 | 2006 | Worldwide | RCT | 2459 | – | 1220 | 1239 | 867 | 821 | 68 (28–91) | 68 (30–90) | 29.5 (16–51) | 29.8 (16–54) | 10 mg OD | 40 mg OD | 14 | 14 | up to 15 days |

| Turpie | 2009 | 2006/2007 | Worldwide | RCT | 3034 | – | 1526 | 1508 | 1007 | 967 | 64 | 65 | 30.9 | 30.7 | 10 mg OD | 30 mg BD | 15 | 15 | up to 17 days |

BD – twice a day; OD – once a day; riv – rivaroxaban; enox – enoxaparin; TKA – total knee arthroplasty; THA – total hip arthroplasty.

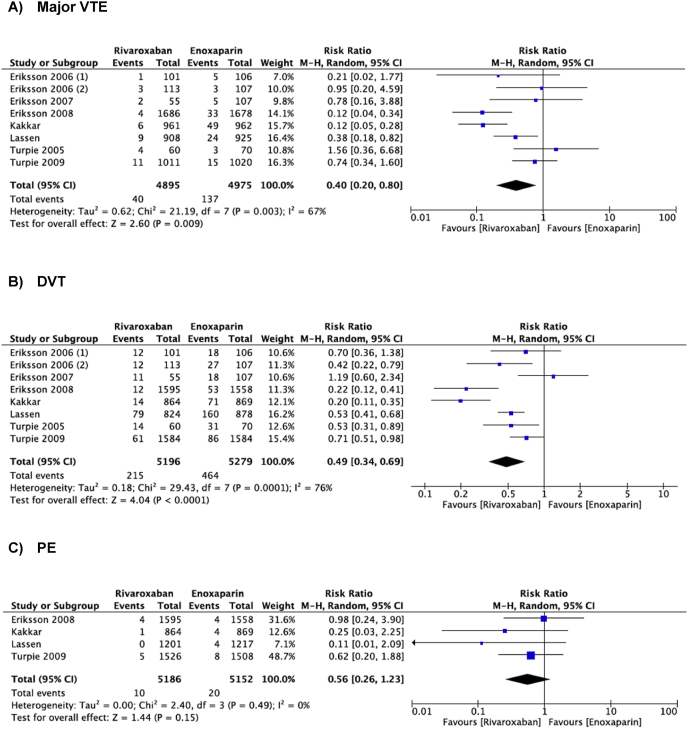

3.3. Efficacy outcomes

Eight studies reported on rates of major VTE (Fig. 2). Compared to enoxaparin, thromboprophylaxis with rivaroxaban was associated with significantly lower rates of major VTE following THA and TKA. (RR = 0.40, 95% CI = 0.20–0.80, I2 = 67%, P = 0.009). From the same studies, DVT rates were found to be significantly lower in those receiving rivaroxaban, compared to enoxaparin (RR = 0.49, 95% CI = 0.34–0.69, I2 = 76%, P < 0.0001). However, from 4 studies reporting on rates of PE, there was no significant difference in those receiving rivaroxaban or enoxaparin (RR = 0.56, 95% CI = 0.26–1.23, I2 = 0, P = 0.15).

Fig. 2.

Meta-analysis of the primary efficacy outcomes comparing rivaroxaban with enoxaparin for thromboprophylaxis after total hip or knee arthroplasty: a) Major venothrombotic event b) Deep vein thrombosis c) Pulmonary embolism.

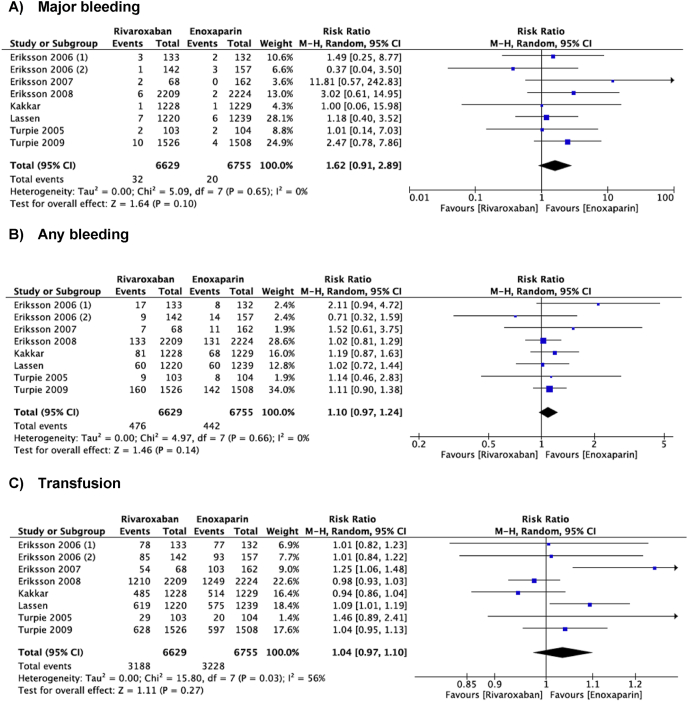

3.4. Safety outcomes

All eight studies reported on the primary safety outcomes (any bleeding, major bleeding, need for transfusion) (Fig. 3). No significant difference was observed in bleeding complications between rivaroxaban and enoxaparin groups (RR = 1.10, 95% CI = 0.97–1.24, I2 = 0%, P = 0.14). Regarding major bleeding events and need for transfusion, no significant difference was found when comparing rates of major bleeding (RR = 1.62, 95% CI = 0.91–2.89, I2 = 0%, P = 0.1) and transfusion (RR = 1.04, 95% = 0.97–1.10, I2 = 56%, P = 0.27) in patients receiving rivaroxaban or enoxaparin.

Fig. 3.

Meta-analysis of the primary safety outcomes comparing rivaroxaban with enoxaparin for thromboprophylaxis after total hip or knee arthroplasty. a) Major bleeding b) Any bleeding c) Blood transfusion.

3.5. Other complications

All-cause mortality was reported in four studies. No significant difference in mortality was demonstrated when comparing outcomes for those receiving rivaroxaban and enoxaparin (RR = 0.79, 95% CI% = 0.35–1.77, I2 = 0%, P = 0.57). Eight studies reported on wound complications with no significant difference found between groups receiving rivaroxaban and enoxaparin (RR = 0.98, CI% = 0.75–1.27, I2 = 0%, P = 0.87). Five studies reported the rates of reoperation with no significant difference between rivaroxaban and enoxaparin groups (RR = 1.94, CI% = 0.81–4.60, I2 = 0%, P = 0.14).

3.6. Subgroup analyses

Subgroup analysis revealed that for patients undergoing THA, rivaroxaban was associated with a reduced risk of major VTE (RR 0.25, 95% CI 0.10–0.62, P = 0.002) as well as DVT (RR 0.43, 95% CI 0.22–0.84, P = 0.01). There were no significant differences in the risk of bleeding or any other complication.

For those undergoing TKA, rivaroxaban thromboprophylaxis significantly reduced the risk of DVT (RR 0.58, 95% CI 0.48–0.71, P < 0.001). However, rivaroxaban was found to have significantly higher rates of post-operative blood transfusion compared to enoxaparin (RR = 1.07, 95% CI 1.01–1.14, P = 0.03). There was no significant difference between groups for all other outcome measures.

3.7. Cost analyses

According to the Australian Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS),19 the cost for a course of rivaroxaban following THA is $99.6 and following TKA is $39.8. For enoxaparin, the cost of a course following THA is $151.1 and following a TKA is $60.4.

For THA, the estimated NNT to prevent one DVT and major VTE was 21 and 38 respectively. This was comparable to TKA, which had an estimated NNT to prevent one DVT of 21. Based on NNT estimates, for those undergoing THA, the cost required to prevent one major VTE was found to be $3785 with rivaroxaban and $5742 for enoxaparin ($1957 less with rivaroxaban). In this group, the cost to prevent one DVT was $2092 with rivaroxaban and $3173 for enoxaparin ($1081 less with rivaroxaban). For those undergoing TKA, the cost to prevent one DVT was estimated to be $836 on rivaroxaban and $1268 for enoxaparin ($432 less with rivaroxaban).

4. Discussion

Venous thromboembolic events are major contributors to post-operative morbidity and mortality. It is recognized that patients undergoing major orthopaedic surgeries are at an increased risk, and the impact on health outcomes for these patients is paralleled by significant financial burdens on the healthcare system. As the number of TKA and THA surgeries are expected to increase worldwide, it is critical that routine thromboprophylaxis is optimized in regard to efficacy, safety, and cost-effectiveness.

The results of the present study demonstrate that overall, rivaroxaban is more effective than enoxaparin in preventing DVT and major VTE without increasing bleeding complications or all-cause mortality for patients undergoing total joint arthroplasty. Our subgroup analysis of patients undergoing only THA showed similar findings. For patients undergoing TKA, while rivaroxaban reduced the rate of DVT, it may increase bleeding risk as seen by the significantly higher rates of post-operative blood transfusion when compared to enoxaparin. Despite this, the medication cost of rivaroxaban required to prevent one DVT or VTE was less than that of enoxaparin (varying from $432 to $1957 less).

The greater efficacy of rivaroxaban in reducing major VTE when compared to enoxaparin has been demonstrated in multiple studies. However, beyond its efficacy, rivaroxaban has other non-financial benefits including its oral method of administration. A study on patient preference for VTE prophylaxis showed that the majority of patients preferred oral medications, citing needle phobia and pain from injection as reasons for potential non-compliance with subcutaneous injections.20 Often the demographic of patients requiring joint replacements are elderly and may have difficulties learning or performing self-injection at home. These patients would then require home nursing visits after discharge, which may be the case in up to 39% of patients receiving enoxaparin.21 The high oral bioavailability and predictable pharmacokinetics of rivaroxaban also makes it a safe medication to use in the greater population.22 Studies have also shown that rivaroxaban has no adverse effects on liver function.23 Additionally, unlike warfarin there is no need for any monitoring during the course of treatment.

The cost-effectiveness of rivaroxaban involves analysis of many factors. The first area to assess is the cost of drug acquisition, administration and monitoring. With rivaroxaban, it is superior in all these facets, being a cheaper medication than enoxaparin ($99.6 vs $151.1 post-THA course in Australia) and requiring less nursing time and hospital resources to administer. Calculations in the US healthcare system have estimated up to a 262 USD reduction in cost per patient using rivaroxaban as opposed to enoxaparin, primarily due to reduced drug acquisition costs and absence of home nurse visits.24 However, this analysis does not factor in any beneficial outcomes that would be achieved from a more effective medication. In a Swedish cohort that factored in the greater thromboprophylactic efficacy of rivaroxaban, they found that over 5 years, rivaroxaban was far more cost effective to the healthcare system than enoxaparin.25 Within the Canadian healthcare system, the improvement in quality-adjusted life years (QALY) with rivaroxaban compared to enoxaparin was $24,9777/QALY.18 This is significantly below the referenced cost-effectiveness threshold of $50,000/QALY.26,27 These improvement in QALY were similarly seen in studies conducted in three other large European cities.28

In the event of a symptomatic VTE, there are significant costs associated with the acute diagnosis and management, along with longer term complications. It is estimated that the initial management of DVTs and PEs cost around $9805 and $14,146 respectively during the initial hospital admission.29 However the rate of readmission can be as high as 14%, which can further burden the health system.29 Indirect costs following discharge such as general practitioner services, follow-up imaging and pathology, carer costs and physiotherapy must also be taken into account. Thus, other US-based studies have provided estimated costs of over $30,000 in the first year following symptomatic VTE, with longer-term costs further compounding the overall economic burden.8,30, 31, 32 One long term complication is post-thrombotic syndrome (PTS), which can affect up to 60% of patients within 2 years of a DVT. Studies have estimated that the overall cost of PTS management can be over $11,000.24,33,34 These studies also don't take into account the loss of productivity that occur with prolonged hospitalisation and premature death. These non-healthcare related financial costs have been estimated to cost the Australian health system around $1.57 billion.7

It is important to acknowledge the limitations in the present study. There was significant heterogeneity between studies, including the treatment regime of VTE prophylaxis. Not only were there variations in the treatment duration of post-operative anticoagulation, different dosing schemes were used too (40 mg enoxaparin daily vs 30 mg enoxaparin twice daily). Other factors not accounted for include use of concurrent mechanical prophylaxis and patient factors affecting thrombotic risk such as previous clotting events and post-operative mobility. This study has also not considered indirect, non-health related, and out-of-hospital costs in the economic analyses. These factors have a significant contribution to overall economic burden of VTE and need to be accounted for in further economic analyses.

5. Conclusions

The present meta-analysis demonstrated that rivaroxaban, compared to enoxaparin was associated with a significant reduction in the risk of VTE. While the risk of bleeding in THA was comparable between the anticoagulants, in TKA there appeared to be more patients requiring transfusion when taking rivaroxaban. Nevertheless, we found that the cost-effectiveness of rivaroxaban, factoring in its efficacy in reducing VTE, was much greater than that of enoxaparin. Thus, rivaroxaban may be a cost-effective and safe alternative for routine thromboprophylaxis following total knee or hip arthroplasty.

Declaration of competing interest

None of the authors have any conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Falck-Ytter Y., Francis C.W., Johanson N.A., et al. Prevention of VTE in orthopedic surgery patients: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of chest Physicians evidence-based clinical Practice guidelines. Chest. 2012;141:e278S–e325S. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-2404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Geerts W.H., Pineo G.F., Heit J.A., et al. Prevention of venous thromboembolism: the Seventh ACCP Conference on antithrombotic and thrombolytic therapy. Chest. 2004;126:338S–400S. doi: 10.1378/chest.126.3_suppl.338S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mohr D.N., Silverstein M.D., Murtaugh P.A., Harrison J.M. Prophylactic agents for venous thrombosis in elective hip surgery. Meta-analysis of studies using venographic assessment. Arch Intern Med. 1993;153:2221–2228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Friedman R.J. Extended thromboprophylaxis after hip or knee replacement. Orthopedics. 2003;26:s225–s230. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-20030202-05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shahi A., Bradbury T.L., Guild G.N., 3rd, Saleh U.H., Ghanem E., Oliashirazi A. What are the incidence and risk factors of in-hospital mortality after venous thromboembolism events in total hip and knee arthroplasty patients? Arthroplast Today. 2018;4:343–347. doi: 10.1016/j.artd.2018.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang L., Baser O., Wells P., et al. Predictors of hospital length of stay among patients with low-risk pulmonary embolism. J Health Econ Outcomes Res. 2019;6:84–94. doi: 10.36469/9744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Economics A. 2008. The Burden of Venous Thromboembolism in Australia. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grosse S.D., Nelson R.E., Nyarko K.A., Richardson L.C., Raskob G.E. The economic burden of incident venous thromboembolism in the United States: a review of estimated attributable healthcare costs. Thromb Res. 2016;137:3–10. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2015.11.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mueck W., Stampfuss J., Kubitza D., Becka M. Clinical pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profile of rivaroxaban. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2014;53:1–16. doi: 10.1007/s40262-013-0100-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D.G., Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA Statement. Open Med. 2009;3:e123–e130. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eriksson B.I., Borris L., Dahl O.E., et al. Oral, direct Factor Xa inhibition with BAY 59-7939 for the prevention of venous thromboembolism after total hip replacement. J Thromb Haemostasis : JTH. 2006;4:121–128. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01657.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eriksson B.I., Borris L.C., Dahl O.E., et al. Dose-escalation study of rivaroxaban (BAY 59-7939) - an oral, direct Factor Xa inhibitor - for the prevention of venous thromboembolism in patients undergoing total hip replacement. Thromb Res. 2007;120:685–693. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2006.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eriksson B.I., Borris L.C., Dahl O.E., et al. A once-daily, oral, direct Factor Xa inhibitor, rivaroxaban (BAY 59-7939), for thromboprophylaxis after total hip replacement. Circulation. 2006;114:2374–2381. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.642074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eriksson B.I., Borris L.C., Friedman R.J., et al. Rivaroxaban versus enoxaparin for thromboprophylaxis after hip arthroplasty. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2765–2775. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0800374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kakkar A.K., Brenner B., Dahl O.E., et al. Extended duration rivaroxaban versus short-term enoxaparin for the prevention of venous thromboembolism after total hip arthroplasty: a double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;372:31–39. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60880-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lassen M.R., Ageno W., Borris L.C., et al. Rivaroxaban versus enoxaparin for thromboprophylaxis after total knee arthroplasty. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2776–2786. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa076016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Turpie A.G., Lassen M.R., Davidson B.L., et al. Rivaroxaban versus enoxaparin for thromboprophylaxis after total knee arthroplasty (RECORD4): a randomised trial. Lancet. 2009;373:1673–1680. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60734-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Turpie A.G.G., Fisher W.D., Bauer K.A., et al. BAY 59-7939: an oral, direct Factor Xa inhibitor for the prevention of venous thromboembolism in patients after total knee replacement. A phase II dose-ranging study. J Thromb Haemostasis. 2005;3:2479–2486. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01602.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme. Australian Government; 2021. www.pbs.gov.au [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wong A., Kraus P.S., Lau B.D., et al. Patient preferences regarding pharmacologic venous thromboembolism prophylaxis. J Hosp Med. 2015;10:108–111. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Skedgel C., Goeree R., Pleasance S., Thompson K., O'Brien B., Anderson D. The cost-effectiveness of extended-duration antithrombotic prophylaxis after total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:819–828. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang H.F., Li S.S., Yang X.T., Xie Q., Tian X.B. Rivaroxaban versus enoxaparin for the prevention of venous thromboembolism after total knee arthroplasty: a meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltim) 2018;97 doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000013465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Borris L.C. Rivaroxaban, a new, oral, direct factor Xa inhibitor for thromboprophylaxis after major joint arthroplasty. Expet Opin Pharmacother. 2009;10:1083–1088. doi: 10.1517/14656560902835513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kwong L.M. Cost-effectiveness of rivaroxaban after total hip or total knee arthroplasty. Am J Manag Care. 2011;17:S22–S26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ryttberg L., Diamantopoulos A., Forster F., Lees M., Fraschke A., Bjorholt I. Cost-effectiveness of rivaroxaban versus heparins for prevention of venous thromboembolism after total hip or knee surgery in Sweden. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2011;11:601–615. doi: 10.1586/erp.11.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Diamantopoulos A., Lees M., Wells P.S., Forster F., Ananthapavan J., McDonald H. Cost-effectiveness of rivaroxaban versus enoxaparin for the prevention of postsurgical venous thromboembolism in Canada. Thromb Haemostasis. 2010;104:760–770. doi: 10.1160/TH10-01-0071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grosse S.D. Assessing cost-effectiveness in healthcare: history of the $50,000 per QALY threshold. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2008;8:165–178. doi: 10.1586/14737167.8.2.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Monreal M., Folkerts K., Diamantopoulos A., Imberti D., Brosa M. Cost-effectiveness impact of rivaroxaban versus new and existing prophylaxis for the prevention of venous thromboembolism after total hip or knee replacement surgery in France, Italy and Spain. Thromb Haemostasis. 2013;110:987–994. doi: 10.1160/TH12-12-0919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spyropoulos A.C., Lin J. Direct medical costs of venous thromboembolism and subsequent hospital readmission rates: an administrative claims analysis from 30 managed care organizations. J Manag Care Pharm. 2007;13:475–486. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2007.13.6.475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bergqvist D., Jendteg S., Johansen L., Persson U., Odegaard K. Cost of long-term complications of deep venous thrombosis of the lower extremities: an analysis of a defined patient population in Sweden. Ann Intern Med. 1997;126:454–457. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-126-6-199703150-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ruppert A., Steinle T., Lees M. Economic burden of venous thromboembolism: a systematic review. J Med Econ. 2011;14:65–74. doi: 10.3111/13696998.2010.546465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cao J.Y., Lee S.Y., Dunkley S., Adams M., Keech A. The case for extended thromboprophylaxis in medically hospitalised patients - not yet made. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2019;2047487319836572 doi: 10.1177/2047487319836572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ashrani A.A., Heit J.A. Incidence and cost burden of post-thrombotic syndrome. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2009;28:465–476. doi: 10.1007/s11239-009-0309-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.MacDougall D.A., Feliu A.L., Boccuzzi S.J., Lin J. Economic burden of deep-vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and post-thrombotic syndrome. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2006;63:S5–S15. doi: 10.2146/ajhp060388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]