Abstract

Background

Recent studies show increasing mortality rates of geriatric femoral neck fracture patients with delays in operative treatment greater than 48 hours from injury. A less extensively studied area in this population is the effect of length of inpatient hospital stay (LOS) on outcomes. The purpose of this study was to determine the association of LOS after arthroplasty for geriatric femoral neck fractures with 30-day mortality risk.

Methods

This study is a retrospective review using the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS-NSQIP), a nationally validated, outcomes-based database incorporating data from over 700 geographically diverse medical centers. It included 9005 patients, 65 years of age or older, who underwent either hemiarthroplasty or total hip arthroplasty for a femoral neck fracture between 2011 and 2018. Using multivariate analysis, risk of 30-day mortality based on surgery-to-discharge time was determined, expressed as odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Results

After controlling for sex, BMI, age, surgical procedure, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification, and discharge location, the risk of mortality after discharge was increased with longer post-surgical length of stay [OR 2.5, P < .001].

Conclusion

Prolonged LOS after arthroplasty for geriatric femoral neck fractures is associated with increased 30-day mortality risk. Efforts made to target and mitigate modifiable risk factors responsible for delaying discharge may improve early outcomes in this population.

Keywords: Femoral neck fractures, Hip fractures, Length of stay, Mortality risk

1. Introduction

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), over 300,000 people aged 65 years or older in the United States (US) are hospitalized annually for a hip fracture.1 Due to the growing geriatric population, the total number of hip fractures is expected to increase in the coming decades.2, 3, 4 Mortality rates in this population have been reported to be as high as 30% at 1 year and projected annual health care costs are expected to reach almost US $10 billion by the year 2040.2 As a result of these devastating physical and financial consequences, The International Geriatric Fracture Society has made addressing these concerns a chief public health issue.5

Outcomes related to time-to-surgery have been well studied. While there remains some inconsistencies in the literature, most high-powered studies show increasing mortality rates with delays in operative treatment of greater than 48 hours.6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 A less extensively studied area of elderly hip fractures is the effect of length of inpatient hospital stay (LOS) on early outcomes. The current literature presents conflicting reports with regard to mortality rates in particular. Recent studies out of Europe and Asia show increasing mortality rates with decreased length of inpatient hospital stay at 30 days and 1 year after discharge, while a single-state study from the United States (US) showed increasing mortality rates with increased LOS at 30 days after discharge.12, 13, 14 While this data may in part reflect differences in national healthcare systems, the stark inconsistencies are significant and suggest the need for further research in this area. Therefore, a comprehensive nationwide analysis on the effect of increasing post-surgical LOS on mortality rates in geriatric femoral neck fractures would be of value.

The main objective of this study was to determine the effect of LOS after arthroplasty for geriatric femoral neck fractures on 30-day mortality after discharge, using a validated national outcomes database.

2. Methods

The study population was generated using the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS-NSQIP) database between the years of 2011 and 2018. A search was performed using Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes 27125 (hemiarthroplasty, hip, partial) and 27130 (total hip arthroplasty). Patients aged 65 years or older were included, and those patients with ASA 5 (15 patients), without ASA score recorded (23 patients), without discharge location recorded (39 patients), discharged to hospice (34 patients), who died in the hospital (302 patients), and discharge greater than 2 weeks post-surgery were excluded. Using these criteria, a total of 9005 patients remained for analysis. This study was exempt from institutional review board (IRB) approval because of the de-identified nature of the database.

The demographic variables age, sex, body mass index (BMI), and ASA class were used. Discharge location including home, acute inpatient rehab (AIR), or skilled nursing facility (SNF) was also obtained. Length of stay is recorded as number of days in the hospital following surgery. Data was then analyzed to determine the risk of mortality for the 30-day period following hospital discharge.

2.1. Statistical analysis

The data analysis was completed using SAS (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina, USA). Univariate analysis was conducted using Pearson's chi-squared for categorical or Fisher's exact test. Statistical significance was set at a P value less than 0.05. A multivariate logistic regression model was built using death after discharge as the outcome variable. The primary explanatory variable of interest was number of days from surgery to discharge. Additional covariates were included to control for the effect of age, sex, BMI, ASA score, discharge location, and procedure type. The model was created with forced entry of variables chosen based upon prior studies and those that were felt to be clinically important. Discharge location was collapsed into the three most clinically meaningful categories (home, acute rehab, skilled nursing facility). ASA score was collapsed into two categories (1–2 and 3–4) due to the relative scarcity of ASA 1 hip fracture patients. Patients discharged greater than 14 days after surgery were excluded as these were considered outliers.

3. Results

Of the 9005 patients included in our analysis, the average age was 81.0 (±7.5) years and the average BMI was 24.6 kg/m2 29.1% percent were male and 70.9% were female. 75.4% of patients were classified as CPT 27125 (hemiarthroplasty, hip, partial) and 24.6% were classified as CPT 27130 (total hip arthroplasty). A summary of mortality in the study population based on patient demographics and comorbidities using a univariate analysis is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient demographics. Univariate analysis using Pearson's chi-squared and fisher's exact test.

|

Death |

P |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Patients | No | % | Yes | % | |

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 6534 | 97.96 | 136 | 2.04 | 0.0003 |

| Male | 2648 | 96.71 | 90 | 3.29 | |

| Age | <.0001 | ||||

| 65–74 yr | 2060 | 98.9 | 23 | 1.1 | |

| 75–84 yr | 3430 | 98.48 | 53 | 1.52 | |

| 85–89 yr | 2001 | 96.85 | 65 | 3.15 | |

| 90–99 yr | 1691 | 95.21 | 85 | 4.79 | |

| BMI | 0.0006 | ||||

| Underweight | 4155 | 97.4 | 111 | 2.6 | |

| Normal | 634 | 95.63 | 29 | 4.37 | |

| Overweight | 2399 | 98.2 | 44 | 1.8 | |

| Obese 1 | 750 | 98.81 | 9 | 1.19 | |

| Obese 2 | 220 | 98.65 | 3 | 1.35 | |

| Obese 3 | 103 | 98.1 | 2 | 1.9 | |

| CPT | <.0001 | ||||

| (27125) Hemiarthroplasty | 6887 | 97.15 | 202 | 2.85 | |

| (27130) THA | 2295 | 98.97 | 24 | 1.03 | |

| ASA Classification | <.0001 | ||||

| 1 | 62 | 100 | 0 | 0 | |

| 2 | 1924 | 99.74 | 5 | 0.26 | |

| 3 | 5769 | 97.85 | 127 | 2.15 | |

| 4 | 1427 | 93.82 | 94 | 6.18 | |

| Discharge location | <.0001 | ||||

| Home | 1819 | 98.64 | 25 | 1.36 | |

| Rehab | 2637 | 98.58 | 38 | 1.42 | |

| SNF | 4726 | 96.67 | 163 | 3.33 | |

| Length of stay after OR (days) | <.0001 | ||||

| 0 to 3 | 4405 | 98.33 | 75 | 1.67 | |

| 4 to 7 | 3805 | 97.09 | 114 | 2.91 | |

| 8 to 14 | 972 | 96.33 | 37 | 3.67 | |

Table 2 demonstrates how preoperative and postoperative variables affected the risk of mortality post-discharge, expressed as odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). With multivariate analysis, factors found to be significantly associated with an increased risk of death at 30 days post-discharge included ages 85–89 or 90 and older [OR 2.05, P < .05 and OR 2.8, P < .0001], ASA class of 3 or 4 [OR 7.2, P < .001], discharge delays of 8–14 days after surgery [OR 2.5, P < .01] and male sex [OR 1.6, P < .01].

Table 2.

Factors predicting death after discharge for patients undergoing treatment for femoral neck fracture, a multivariate logistic regression analysis.

|

Analysis of Maximum Likelihood Estimates |

Odds Ratio Estimates |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | P | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | |

| Sex | Female | Reference | ||

| Male | 0.0035 | 1.559 | 1.157–2.1 | |

| Age | 65–74 yr | Reference | ||

| 75–84 yr | 0.0036 | 1.078 | 0.638–1.821 | |

| 85–89 yr | 0.0365 | 2.052 | 1.221–3.448 | |

| 90–99 yr | <.0001 | 2.801 | 1.678–4.677 | |

| BMI | Underweight | 0.44 | 0.583 | 0.38–0.893 |

| Normal | Reference | |||

| Overweight | 0.4633 | 0.431 | 0.264–0.703 | |

| Obese 1 | 0.2054 | 0.334 | 0.155–0.719 | |

| Obese 2 | 0.5856 | 0.381 | 0.113–1.287 | |

| Obese 3 | 0.9856 | 0.509 | 0.118–2.205 | |

| ASA Classification | 1 or 2 | Reference | ||

| 3 or 4 | <.0001 | 7.226 | 2.953–17.685 | |

| CPT | (27125) Hemiarthroplasty | Reference | ||

| (27130) THA | 0.0438 | 0.629 | 0.401–0.987 | |

| Discharge Location | Home | Reference | ||

| Rehab | 0.0221 | 0.765 | 0.439–1.335 | |

| SNF | 0.0008 | 1.53 | 0.95–2.463 | |

| Length of Stay after OR (days) | 0 to 3 | Reference | ||

| 4 to 7 | 0.444 | 1.759 | 1.28–2.418 | |

| 8 to 14 | 0.0027 | 2.453 | 1.571–3.83 | |

4. Discussion

The benefits of the prompt surgical treatment of geriatric femoral neck fractures are widely recognized in the orthopaedic community.6,9,10,14,17 Numerous high-powered studies have shown superior outcomes with early operative fixation, and in turn, the most current evidence-based guidelines recommend surgery within 48 hours of admission.5,18 Less clear is the effect of postoperative LOS on outcomes in this population. Recent reports have shown disparate results, and to the knowledge of the research team for this study, no current study has examined the effect of surgery-to-discharge time on early mortality rates, specifically. This study aimed to address these inconsistencies in recent investigations and fill this gap in the current literature, specifically in those patients who underwent either total or partial hip replacement.

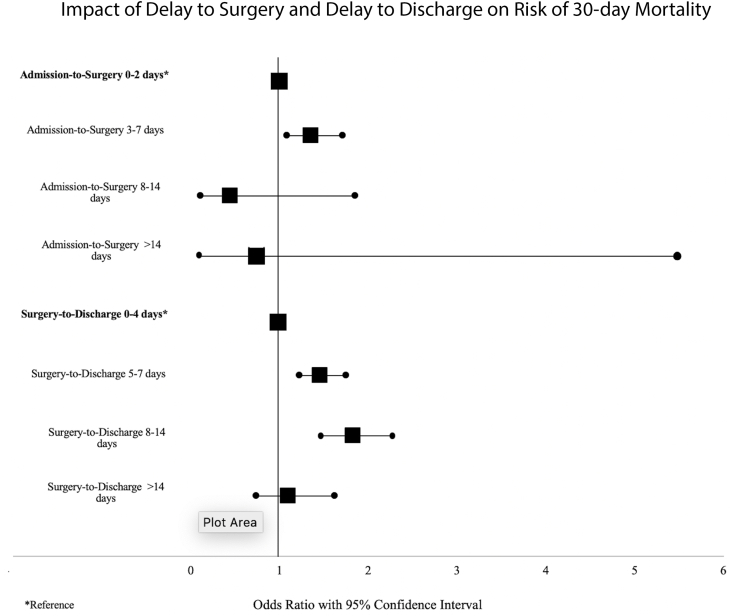

The results of this study demonstrate that increasing time to discharge after surgical fixation significantly increased mortality risk (Fig. 1).9,18 Similar studies in the current literature have yielded conflicting reports. In a large investigation out of Sweden, a decreased LOS after hip fracture was associated with an increased risk of death at 30 days, among patients with a LOS 10 days or fewer.14 Comparable outcomes were noted in Korea, where 1-year mortality rates were increased in elderly hip fracture patients discharged within 10 days of hospital admission.12 In contrast, a study of New York state patients found that hospital stays of 11–14 days after hip fracture were associated with a 32% increased odds of death at 30 days, compared to a LOS of 1–5 days.12 The outcomes in the current study are more in line with the aforementioned American data. It is important to mention that the inconsistencies between the two studies in America and those in Europe/Asia are likely due to differences in healthcare structure between countries. Countries like the US, United Kingdom, and Australia have tiered healthcare systems; patients are often discharged from hospitals to acute, subacute, or long-term care facilities for continued rehabilitation prior to being discharged home.19 This study further exemplifies this difference by demonstrating that 53.6% of the patient population studied was discharged to a skilled nursing facility (SNF) before going home. Other studies have defined this observation that many older patients in the United States are frequently discharged to SNFs given that SNFs have been shown to reduce readmission rates.20,21 Hospital systems in the US especially began to favor discharge to SNFs after the Affordable Care Act prompted Medicare to implement payment reforms tailored to reducing the rates of readmission.22 Other nations, including Sweden, Korea and Japan, provide most of the postoperative care and rehabilitation in the hospitals prior to being discharged home or to other non-medical care facilities.13,23

Fig. 1.

Impact of delay to surgery and delay to discharge on risk of 30-day mortality.

Another significant finding of this study includes the increased risk of mortality in patients with higher ASA classifications. In a retrospective review of 197 geriatric hip fracture patients, Donegan et al. found that patients in ASA class 3 or 4 were at significantly higher risk for postoperative medical complications.24 Data from this study corroborate this finding by demonstrating that patients classified as ASA 3 or 4 had a greater risk of mortality at 30 days. Other risk factors for increased mortality in the current study were increasing age and decreasing BMI; these factors, which are in accord with prior investigations, likely are a reflection of decreased overall fitness for surgery and the rigors of post-surgical rehabilitation.25,26

Authors of similar studies investigating the effect of LOS on 30-day mortality have performed analyses using the admission-to-discharge time period for their LOS calculations. The current study is unique in its use of the surgery-to-discharge time period as a variable of interest; this was chosen in an effort to eliminate possible pre-surgical confounding factors. With this methodological change, the ability to target modifiable risk factors specific to the post-surgical, in-hospital period is enhanced.

Results of the current study suggest the merit of investigation into delays to discharge after femoral neck fracture surgery in the elderly. With the prevalence of elderly hip fractures increasing, it is imperative to identify modifiable factors in the post-operative, pre-discharge period that may contribute to this delay so that targeted interventions can be conducted.1,27 Prompt involvement of multidisciplinary programs (including those involving social workers), effective discharge planning, timely transfers, and social support outside of the hospital (especially support involving help with functional capacities, residential status, transportation, follow-up, and medications) have been shown to reduce length of hospital stay and readmissions.28, 29, 30 It is important to note that this study's findings do not advocate for accelerated discharge, but rather avoiding significant discharge delays.

Understanding the results of this study in the context of its limitations is critical. First, it is a retrospective review of a national database, making it challenging to understand specific patient characteristics and factors that influence treatment. Second, this study focused on fixation of femoral neck fractures only. While this allowed us to analyze a more homogenous population, the results cannot necessarily be extrapolated to all hip fractures. Third, the data on outcomes is limited to 30-days post operatively as the ACS-NSQIP database only collects up to 30 days worth of post-operative data. Lastly, this study did not control for inpatient postoperative complications. It is possible that a contributing factor to the increased 30-day mortality risk in patients with a delayed discharge was a serious inpatient complication, such as myocardial infarction or pulmonary embolus. However, the contrary is also possible, and represents the crux of our study; delayed discharge, initially independent of an inpatient complication, can be a contributing factor to an eventual inpatient complication. Controlling for inpatient complications would have prevented us from capturing this result. By excluding inpatient deaths and patients discharged to hospice, we have attempted to exclude the sickest postoperative patients.

5. Conclusion

This study demonstrated that prolonged LOS after the surgical treatment of geriatric femoral neck fractures increases mortality risk within 30 days post-discharge. Though several factors associated with prolonged LOS after geriatric femoral neck fracture surgery are non-modifiable, it is essential to identify modifiable factors in the surgery-to-discharge time period in order to apply targeted interventions and effect positive change on outcomes. While the current study does not advocate for accelerated discharge, efforts to mitigate prolonged LOS after femoral neck fracture surgery may provide early mortality benefits in the geriatric population.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that there is no potential conflict of interest relevant to this article.

References

- 1.Hip fractures among older adults. 2016. https://www.cdc.gov/homeandrecreationalsafety/falls/adulthipfx.html Web site Updated.

- 2.Bhandari M., Devereaux P.J., Tornetta P., et al. Operative management of displaced femoral neck fractures in elderly patients. an international survey. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(9):2122–2130. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.00535. 87/9/2122 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garcia A.E., Bonnaig J.V., Yoneda Z.T., et al. Patient variables which may predict length of stay and hospital costs in elderly patients with hip fracture. J Orthop Trauma. 2012;26(11):620–623. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0b013e3182695416. [doi] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Siegmeth A.W., Gurusamy K., Parker M.J. Delay to surgery prolongs hospital stay in patients with fractures of the proximal femur. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87(8):1123–1126. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.87B8.16357. 87-B/8/1123 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.About." IGFS, www.geriatricfracture.org/about.html. Accessed 14 June 2021.

- 6.McGuire K.J., Bernstein J., Polsky D., Silber J.H. The 2004 marshall urist award: delays until surgery after hip fracture increases mortality. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;428(428):294–301. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000146743.28925.1c. 294-301. 00003086-200411000-00044 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Majumdar S.R., Beaupre L.A., Johnston D.W., Dick D.A., Cinats J.G., Jiang H.X. Lack of association between mortality and timing of surgical fixation in elderly patients with hip fracture: results of a retrospective population-based cohort study. Med Care. 2006;44(6):552–559. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000215812.13720.2e. [doi] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weller I., Wai E.K., Jaglal S., Kreder H.J. The effect of hospital type and surgical delay on mortality after surgery for hip fracture. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87(3):361–366. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.87b3.15300. [doi] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mitchell S.M., Chung A.S., Walker J.B., Hustedt J.W., Russell G.V., Jones C.B. Delay in hip fracture surgery prolongs postoperative hospital length of stay but does not adversely affect outcomes at 30 days. J Orthop Trauma. 2018;32(12):629–633. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0000000000001306. [doi] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seong Y.J., Shin W.C., Moon N.H., Suh K.T. Timing of hip-fracture surgery in elderly patients: literature review and recommendations. Hip Pelvis. 2020;32(1):11–16. doi: 10.5371/hp.2020.32.1.11. [doi] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moran C.G., Wenn R.T., Sikand M., Taylor A.M. Early mortality after hip fracture: is delay before surgery important? J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(3):483–489. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.01796. 87/3/483 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nikkel L.E., Kates S.L., Schreck M., Maceroli M., Mahmood B., Elfar J.C. Length of hospital stay after hip fracture and risk of early mortality after discharge in New York state: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2015;351:h6246. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h6246. [doi] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yoo J., Lee J.S., Kim S., et al. Length of hospital stay after hip fracture surgery and 1-year mortality. Osteoporos Int. 2019;30(1):145–153. doi: 10.1007/s00198-018-4747-7. [doi] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nordstrom P., Gustafson Y., Michaelsson K., Nordstrom A. Length of hospital stay after hip fracture and short term risk of death after discharge: a total cohort study in Sweden. BMJ. 2015;350:h696. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h696. [doi] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lefaivre K.A., Macadam S.A., Davidson D.J., Gandhi R., Chan H., Broekhuyse H.M. Length of stay, mortality, morbidity and delay to surgery in hip fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2009;91(7):922–927. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.91B7.22446. [doi] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Management of hip fractures in the elderly: timing of surgical intervention. performance measure and technical report from the american academy of orthopaedic surgeons. 2018. https://aaos.org/globalassets/quality-and-practice-resources/hip-fractures-in-the-elderly/hip-fx-timing-measure-technical-report.pdf Updated.

- 19.Johansen A., Wakeman R., Boulton C., Plant F., Roberts J., Williams A. A national hip fracture database: national report 2013 from london royal college of physicians. 2013. https://www.nhfd.co.uk/20/hipfractureR.nsf/0/CA920122A244F2ED802579C900553993/$file/NHFD%20Report%202013.pdf Updated.

- 20.Allen L.A., Hernandez A.F., Peterson E.D., et al. Discharge to a skilled nursing facility and subsequent clinical outcomes among older patients hospitalized for heart failure. Circ Heart Fail. 2011;4(3):293–300. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.110.959171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Werner R.M., Coe N.B., Qi M., Konetzka R.T. Patient outcomes after hospital discharge to home with home health care vs to a skilled nursing facility. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(5):617–623. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.7998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coe Norma B., et al. 12 Mar. 2019. “Patients Discharged to Home Care vs. Nursing Facilities Have Higher Rates of Hospital Readmissions.” Penn Medicine.www.pennmedicine.org/news/news-releases/2019/march/patients-discharged-to-home-care-vs-nursing-facilities-have-higher-rates-of-hospital-readmissions Penn Medicine. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kitamura S., Hasegawa Y., Suzuki S., et al. Functional outcome after hip fracture in Japan. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1998;348(348):29–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Donegan D.J., Gay A.N., Baldwin K., Morales E.E., Esterhai J.L., Mehta S. Use of medical comorbidities to predict complications after hip fracture surgery in the elderly. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(4):807–813. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.I.00571. [doi] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sheehan K.J., Sobolev B., Guy P. Mortality by timing of hip fracture surgery: factors and relationships at play. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2017;99(20) doi: 10.2106/JBJS.17.00069. [doi] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fantini M.P., Fabbri G., Laus M., et al. Determinants of surgical delay for hip fracture. Surgeon. 2011;9(3):130–134. doi: 10.1016/j.surge.2010.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miyamoto R.G., Kaplan K.M., Levine B.R., Egol K.A., Zuckerman J.D. Surgical management of hip fractures: an evidence-based review of the literature. I: femoral neck fractures. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2008;16(10):596–607. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200810000-00005. 16/10/596 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Preyde M., Brassard K. Evidence-based risk factors for adverse health outcomes in older patients after discharge home and assessment tools: a systematic review. J Evid Base Soc Work. 2011 Oct 26;8(5):445–468. doi: 10.1080/15433714.2011.542330. 10.1080/15433714.2011.542330. PMID: 22035470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shepperd S., Lannin N.A., Clemson L.M., McCluskey A., Cameron I.D., Barras S.L. Discharge planning from hospital to home. Cochrane Review. 2003 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000313.pub4. January 31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kosse N.M., Dutmer A.L., Dasenbrock L., Bauer J.M., Lamoth C.J. Effectiveness and feasibility of early physical rehabilitation programs for geriatric hospitalized patients: a systematic review. BMC Geriatr. 2013;13:107. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-13-107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]