Abstract

In the event of a major accidental or intentional radiation exposure incident, the affected population could suffer from total- or partial-body exposures to ionizing radiation with acute exposure to organs that would produce life-threatening injury. Therefore, it is necessary to identify markers capable of predicting organ-specific damage so that appropriate directed or encompassing therapies can be applied. In the current work, gene expression changes in response to total-body irradiation (TBI) were identified in heart, lungs and liver tissue of Göttingen minipigs. Animals received 1.7, 1.9, 2.1 or 2.3 Gy TBI and were followed for 45 days. Organ samples were collected at the end of day 45 or sooner if the animal displayed morbidity necessitating euthanasia. Our findings indicate that different organs respond to TBI in a very specific and distinct manner. We also found that the liver was the most affected organ in terms of gene expression changes, and that lipid metabolic pathways were the most deregulated in the liver samples of non-survivors (survival time,45 days). We identified organ-specific gene expression signatures that accurately differentiated non-survivors from survivors and control animals, irrespective of dose and time postirradiation. At what point did these radiation-induced injury markers manifest and how this information could be used for applying intervention therapies are under investigation.

INTRODUCTION

An intentional or accidental mass casualty radiation event could expose large populations to lethal and sub-lethal doses of ionizing radiation. Such scenarios would require rapid triaging to optimally utilize limited local resources (1). Determining radiation dose-sensitive biomarkers for total- and partial-body exposures is an ongoing effort. While the traditional dicentric chromosome assay (DCA) remains the most accurate parameter for whole-body dose differentiation, results are not available for 3–4 days. Even with the newer, innovative, fully automated platforms used to perform DCA and micronucleus assays, results are not expected to be available sooner than the third day (2–4). Research in the last decade has identified several protein and gene expression signatures for conducting rapid total-body irradiation (TBI) biodosimetry in model organisms ranging from mice to non-human primates (5–20). Efforts are ongoing to design an easy-to-use and highly accurate assay, based on such biological parameters, for conducting biodosimetry in total- and partial-body exposures. A remarkable gene expression-based biodosimetry test called REDI-Dx has been developed to distinguish clinically relevant doses of 2 and 6 Gy with high sensitivity and specificity (18). This test compared favorably with a hypothetical model biodosimeter and could potentially process 600 samples in a 24 h time frame. While most research in the field of biodosimetry is focused on identifying biomarkers for TBI, it is also crucial to guide medical management for mitigating and treating specific organ syndromes (21). Organ-specific biomarkers can assist with medical triage and management by helping distinguish the extent of organ injury, which may require intervention within the first few days of exposure. Such crucial information combined with a platform like REDI-Dx could help identify and mitigate or prevent acute damage to organs.

Cytogenetic assays such as the DCA can help ascertain partial-body exposures as follows: Appearance of chromosomal aberrations in peripheral blood lymphocytes as a function of dose is known to follow a Poisson distribution (22). In a non-uniform radiation exposure, which is possible in a scenario involving a heterogenous population and initial flash of radiation obscured by buildings or other objects, a higher variance than those predicted by Poisson distribution (23) is observed. An analysis of the distribution of chromosomal aberrations observed in peripheral blood lymphocytes could therefore provide information about the extent of partial-body exposures. While useful and informative for predicting percentage of the body exposures, cytogenetic analysis from peripheral blood lymphocytes fails to provide any information about which organ systems are critically exposed. Furthermore, cytogenetic analysis requires highly specialized laboratories and personnel that might not possess the high throughput required for immediate medical management in a mass casualty incident. Therefore, finding new, easily assayable markers for early intervention to mitigate injury is crucial.

Clinical symptoms can give valuable information about specific organ systems damaged by acute radiation exposure. For example, presence of bloody diarrhea suggests involvement of the gastrointestinal system, while neutropenia and thrombocytopenia indicate damage to the hematopoietic system (24, 25). Localized skin erythema, blistering and pigmentation could indicate exposure to underlying organs; however, skin injuries could also be caused by low-penetrating exposure, making it difficult to ascertain the extent of injury to internal organs (26). Furthermore, exposure of certain organs, such as the heart, to low but medically significant doses may go unnoticed for lack of overt and early signs of damage. By the time clinical symptoms manifest, the affected organs may have already suffered irreparable damage that could have been identified by early biomarkers and mitigated by preemptive medical management.

There are few published studies that explore the possibility of identifying blood-based RNA and protein markers of partial-body irradiation. Nine plasma-based biochemical markers and hematological parameters were found to discriminate total- and partial-body-irradiated baboons (27). Meadows et al. have identified gene expression signatures from peripheral blood after total-and partial-body irradiation in mice (28). Peripheral blood signatures for partial-body irradiation were found to depend on the anatomic site irradiated. The TBI signatures differed from the partial-body irradiation signatures, suggesting that multiple signatures are needed to accurately access the radiation status of the affected individual. Prediction models built from a TBI mouse model, based on several plasma proteins in mice, were able to predict partial-body exposures to the trunk with an accuracy of 67% and an exposure to both trunk and limbs with an accuracy of 100% (15).

These studies provide useful information but do not unequivocally establish markers capable of ascertaining partial-body exposures and identifying the most affected organs from total- and partial-body exposure. In the current study, we explored organ-specific effects of radiation injury and identification of organ-specific markers of radiation damage. This study is a continuation of efforts to develop minipigs as an alternative large animal model for radiation biodosimetry studies (6). We hypothesized that ionizing radiation exposure can cause specific gene expression changes in different organs that might correlate with the extent of organ damage. We identified gene expression changes inherent to lung, liver and heart tissues in response to TBI in the Göttingen minipig hematopoietic and gastrointestinal injury model.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal Husbandry and Treatment

Male Göttingen minipigs (Sus scrofa domesticus), aged 5–6 months, were used for this study. Animals were housed in humane conditions in a laboratory accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC) at the Armed Forces Radiobiology Research Institute (AFRRI, Bethesda MD). The AFRRI Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) approved all animal experiments and all efforts were made to minimize animal suffering. Animals received unilaterally, sequentially, total midline body doses of 1.7, 1.9, 2.1 or 2.3 Gy (n = 6/dose) of TBI at a dose rate of 0.5–0.6 Gy/min using a cobalt-60 (60Co) source in the AFRRI Cobalt-60 Radiation Facility. Animals were anesthetized with an intramuscular (IM) injection of Telazol ®VR (100 mg/ml, 2 mg/kg) and xylazine (50 mg/ml, 1 mg/kg) before placing in a sling for the duration of irradiation. The two sources were raised sequentially with a lateral geometry of exposure. The unilateral sequential exposure is derived from the setup of the AFRRI Cobalt-60 Radiation Facility, which contains two sets of 60Co rods that are lifted sequentially to generate a field. Dose rates were determined using an alanine/ESR (electron spin resonance) dosimetry system (American Society for Testing and Material Standard E 1607) contained in water-filled cylindrical pig phantoms. The AFRRI’s dose calibration curves are based on alanine dosimeters irradiated at either the National Institute of Standards and Technology (Gaithersburg, MD) or the National Physical Laboratory (Teddington, England). This provides direct traceability of AFRRI’s doses to the national radiation standards. Dose rates in phantoms were converted to the dose rate for the animals by accounting for the decay of the 60Co source, the small difference in mass energy-absorption coefficients for water and soft tissue, and size of the animal. The radiation field was uniform within ±2%. Additionally, real-time dosimetry of the output dose was measured using an ion chamber system. The doses chosen were previously estimated to correspond to LD10/45 (1.7 Gy), LD25/45 (1.9 Gy), LD50/45 (2.1 Gy) and LD75/45 (2.3 Gy). With a limited number of animals per dose group (n = 6), the observed LD values (LD100/45, LD50/45, LD33/45 and LD0/45, respectively, for 2.3 Gy, 2.1 Gy, 1.9 Gy and 1.7 Gy) in our study were close to the predicted survival values. Three sham-irradiated animals served as controls (total of 27 animals). The animals were followed up for 45 days. During the 45-day study period, pigs were assessed at least twice daily for signs of pre-established criteria that necessitated unscheduled euthanasia. Prior to euthanasia, anesthesia was induced with 5–2% isoflurane and animals received an IM injection of xylazine and Telazol (as described above). Euthasolt® (sodium pentobarbital) was intravenously (IV) injected for euthanasia. Unscheduled euthanasia was necessitated if one absolute criterion (non-responsiveness, dyspnea, loss of ≥20% body weight, hypothermia) or four non-absolute criteria (hyperthermia, anorexia, anemia, vomiting/diarrhea, lethargy, seizures/vestibular signs, prolonged hemorrhage) were observed. Organ samples were collected at the time of necropsy within 1 h of euthanasia (scheduled or unscheduled). Samples intended for RNA extraction were transferred to dry ice and later stored at −80°C until further processing. Samples intended for histopathological assessment were dropped into 10% zinc buffered formalin.

Histopathology

Tissues fixed in zinc-buffered 10% formalin at necropsy were trimmed, embedded in paraffin blocks and sectioned. All organ sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) to determine the presence of hemorrhage and other lesions. All slides were assessed by a board-certified histopathologist.

RNA Isolation

Samples were bathed in liquid nitrogen and pulverized into a fine powder using a mortar and pestle. Approximately 100 lg of powdered sample was lysed with 700 μl of QIAzol® lysis buffer (QIAGEN®, Valencia, CA) and homogenized by passing the sample through a QIAshredder spin column (QIAGEN). RNA extraction was performed using standard miRNeasy mini kits (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Quality and quantity of the RNA samples were assessed using a DeNovix® DS-11 NanoDrop™ spectrophotometer (Wilmington, DE) and an Agilent bioanalyzer using the RNA 6000 Nano LabChip® (Santa Clara, CA).

Microarray Experiment

Microarrays were performed in two batches. Batch 1 was comprised of the three control animals (sham 1), and 1.7, 2.1 and 2.3 Gy irradiated animals. Batch 2 was comprised of the same three control animals (sham 2) and 1.9 Gy irradiated animals. Following the manufacturer’s protocol, total RNA was reverse transcribed after priming with a DNA oligonucleotide containing the T7 RNA polymerase promoter 5′ to a d(T)24 sequence. After second-strand cDNA synthesis and purification of double-stranded cDNA, in vitro transcription was performed using T7 RNA polymerase. The quantity and quality of the cRNA was assayed using spectrophotometry and an Agilent bioanalyzer as indicated for RNA isolation. cRNA was fragmented to uniform size and hybridized to porcine (V2) gene expression microarrays (Agilent Technologies). Slides were washed and scanned on an Agilent SureScan microarray scanner. Expression values were extracted using Agilent Feature Extraction software.

Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was performed using GeneSpring GX software (Agilent Technologies). Data normalization and batch-effect correction were performed in GeneSpring using the COMBAT-Quantile method (29). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed along the dose and survival variables separately; results were then filtered using a Benjamini Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR) of q < 0.005 for heart and liver samples and q < 0.05 for lung samples. A less stringent q value threshold was selected for lung samples as there were fewer differentially expressed probes for the lung tissue. A post hoc analysis to test group mean differences along both dose and survival variables was performed using the Tukey’s honestly significant difference (HSD) method (P < 0.005 for heart and lung samples; P < 0.05 for lung samples). Absolute fold change cutoff was set to 2. Principal component analysis (PCA) plots were generated from the whole probe set, reducing the data down to four principal components. Hierarchical clusters were generated using Euclidean distant metric with complete linkage rule. Naïve Bayes and decision tree classification models were developed to predict survival classes (survivor, non-survivor and control groups) from differential gene expression. The predictive models involved feature selection of the most predictive probes for each classification problem and leave-one-out cross validation to validate the down-selected probe sets and estimate model accuracy for future generalization.

Ingenuity Pathway Analysis

Core and comparison analyses were performed in Ingenuity® Pathway Analysis (IPA®; QIAGEN). IPA does not support Sus scrofa IDs; therefore, corresponding human, rat and mouse gene symbols were used in all analyses. Pathways and function terms that satisfied an absolute z score of more than 2 and P value of less than 0.01 were predicted to be altered based on the gene expression data.

RESULTS

Extensive Abnormalities in the Organs of Non-Surviving Animals Revealed by Histopathology

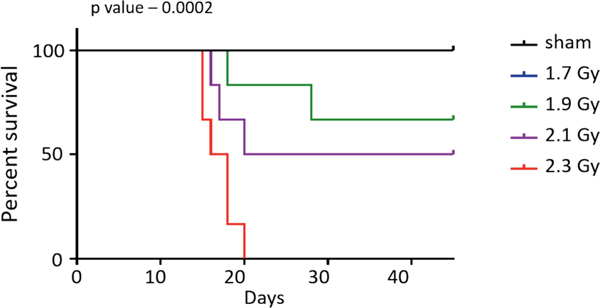

The irradiated minipigs were followed for a maximum of 45 days, at which point all surviving animals were sacrificed (Fig. 1). All six treated with 1.7 Gy survived for 45 days. Two animals exposed to 1.9 Gy died before 45 days while four survived up to 45 days. Of the six animals irradiated with 2.1 Gy, three survived 45 days and three died earlier. All animals irradiated with 2.3 Gy died before the 45-day period. Extensive morphological abnormalities were observed in various organs of the non-survivors at the time of necropsy (Table 1). Some of the recurrent abnormalities observed in the non-survivors were: moderate to severely diffuse and hypocellular bone marrow; moderate to minimal multifocal hemorrhage and edema in the lungs; degeneration of the epicardium and/or myocardium in the heart along with multifocal hemorrhage; multifocal hemorrhage and congestion in the GI tract; and diffuse lymphocytolysis and moderate to severe congestion in the spleen. Two non-survivors displayed multifocal and mild hepatocellular degeneration. In three non-survivors, multifocal and moderate hemorrhage was observed in the kidneys. In contrast, all survivors displayed abnormalities only in the bone marrow and spleen, with normal morphology observed in all other organs assessed. Most survivors had minimally diffuse and hypocellular bone marrow and moderate-to-diffuse congestion in the spleen. We observed dependence of hematological parameters, recorded at the time of necropsy, on the survival state of the animal (Supplementary Fig. S10A–C; https://doi.org/10.1667/RADE-20-00123.1.S1). Similar survival dependence was also observed for liver-specific enzymes, ALT (alanine aminotransferase) and GGT (gamma-glutamyl transferase) (Supplementary Fig. S10D and E), Perl’s iron staining in hepatocytes and Kupffer cells (Supplementary Fig. S10F and G) and Fraser-Lendrum staining in lungs and heart (Supplementary Fig. S10H and I).

FIG. 1.

Kaplan-Meir survival curve for the animals studied. Time is plotted along the x-axis and percentage survival along y-axis; P value was determined using log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test.

TABLE 1.

H&E Staining Based Histology of Sections Prepared from Paraffin-Embedded Blocks of Listed Organs from Minipigs after Sacrifice

| Animal ID no. | Dose (Gy) | Survival (yes = 1, no = 0) | Survival (no. of days) | Bone marrow | Lung | Heart | GI | Liver | Kidney | Urinary bladder | Spleen |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||

| 5489921 | 2.3 | 0 | 15 | Hypocellular, diffuse, severe | WNL | WNL | Hemorrhage and congestion, multifocal, mild | No significant findings | Hemorrhage, multifocal, moderate | WNL | Lymphocytolysis, diffuse, moderate, with splenic congestion |

| 5493758 | 2.3 | 0 | 16 | Hypocellular, diffuse, severe | Hemorrhage and edema, multifocal, mild | Degeneration and necrosis, multifocal, minimal, with hemorrhage | Hemorrhage and congestion, multifocal, mild-moderate | WNL | WNL | WNL | Congestion, diffuse, moderate-severe |

| 5491160 | 2.3 | 0 | 18 | Hypocellular, diffuse, severe | Hemorrhage and edema, multifocal, mild | Hemorrhage, multifocal, severe | Hemorrhage, multifocal, mild | Hepatocellular degeneration and necrosis, multifocal, mild | Hemorrhage, multifocal, minimal | WNL | Lymphoid depletion, diffuse, moderate |

| 5492132 | 2.3 | 0 | 18 | Hypocellular, diffuse, severe | Hemorrhage and edema, multifocal, mild. | Myocardium: Degeneration, multifocal, mild with minimal fibrosis; Epicardium: Hemorrhage, multifocal, moderate | Hemorrhage, focally extensive, moderate, with edema | WNL | WNL | WNL | Congestion, diffuse, moderate |

| 5508305 | 2.3 | 0 | 15 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| 5508186 | 2.3 | 0 | 20 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| 5489556 | 2.1 | 0 | 20 | Hypocellular, diffuse, severe | Hemorrhage, multifocal mild | Epicardium: Hemorrhage, multifocal, severe | Hemorrhage and congestion, multifocal, mild | WNL | WNL | WNL | Lymphocytolysis, diffuse, moderate, with splenic congestion |

| 5507457 | 2.1 | 0 | 16 | Hypocellular, diffuse, moderate | Hemorrhage and edema, multifocal, mild | WNL | WNL | WNL | WNL | WNL | Congestion, diffuse, severe |

| 5493952 | 2.1 | 0 | 16 | Hypocellular, diffuse, severe | Edema, multifocal, minimal | Degeneration, multifocal, minimal, with hemorrhage | Hemorrhage and congestion, multifocal, mild-moderate | WNL | Hemorrhage, multifocal, moderate | Hemorrhage, multifocal, moderate | Congestion, diffuse, severe |

| 5493766 | 2.1 | 1 | 45 | Hypocellular, diffuse, minimal | WNL | WNL | WNL | WNL | WNL | WNL | Congestion, diffuse, severe |

| 5502145 | 2.1 | 1 | 45 | Hypocellular, diffuse, minimal | WNL | WNL | WNL | WNL | WNL | WNL | Congestion, diffuse, severe |

| 5502145 | 2.1 | 1 | 45 | Hypocellular, diffuse, minimal | WNL | WNL | WNL | WNL | WNL | WNL | Congestion, diffuse, severe |

| 5489734 | 1.9 | 0 | 18 | Hypocellular, diffuse, severe | Hemorrhage and edema, multifocal, moderate | Epicardium: Hemorrhage, multifocal, severe | Hemorrhage, multifocal, mild | Hepatocellular degeneration (glycogen type), multifocal, mild | No significant findings | WNL | Lymphoid depletion, diffuse, moderate |

| 5403532 | 1.9 | 0 | 28 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| 5507295 | 1.9 | 1 | 45 | Hypocellular, diffuse, moderate. | WNL | WNL | WNL | WNL | WNL | WNL | |

| 5493112 | 1.9 | 1 | 45 | Hypocellular, diffuse, minimal | WNL | WNL | WNL | WNL | WNL | WNL | Hypoplasia, diffuse, moderate, with diffuse congestion |

| 5507384 | 1.9 | 1 | 45 | Hypocellular, diffuse, moderate | WNL | WNL | WNL | WNL | WNL | WNL | Severe splenic congestion |

| 5490775 | 1.9 | 1 | 45 | Hypocellular, diffuse, moderate | WNL | WNL | WNL | WNL | WNL | WNL | Congestion, diffuse, moderate |

| 5492492 | 1.7 | 1 | 45 | Hypocellular, diffuse, minimal | WNL | WNL | WNL | WNL | WNL | WNL | Congestion, diffuse, severe |

| 5493481 | 1.7 | 1 | 45 | Bone marrow: Hypocellular, diffuse, minimal | WNL | WNL | WNL | WNL | WNL | WNL | Hypoplasia, diffuse, severe, with diffuse congestion |

| 5503117 | 1.7 | 1 | 45 | Hypocellular, diffuse, minimal | WNL | WNL | WNL | WNL | WNL | WNL | Congestion, diffuse, severe |

| 5506698 | 1.7 | 1 | 45 | Hypocellular, diffuse, mild | WNL | WNL | WNL | WNL | WNL | WNL | Lymphoid hypoplasia, multifocal, severe, with moderate congestion |

| 5507236 | 1.7 | 1 | 45 | Hypocellular, diffuse, mild | WNL | WNL | WNL | WNL | WNL | WNL | Lymphoid hypoplasia, multifocal, severe, with severe congestion |

| 5491551 | 1.7 | 1 | 45 | Hypocellular, diffuse, moderate | WNL | WNL | WNL | WNL | WNL | WNL | Congestion, diffuse, severe |

Notes. Animals that died are indicated in bold face. No histological studies were performed on three animals from the list: nos. 5508305, 5508186 and 5503532. WNL = within normal limits; ND = not determined

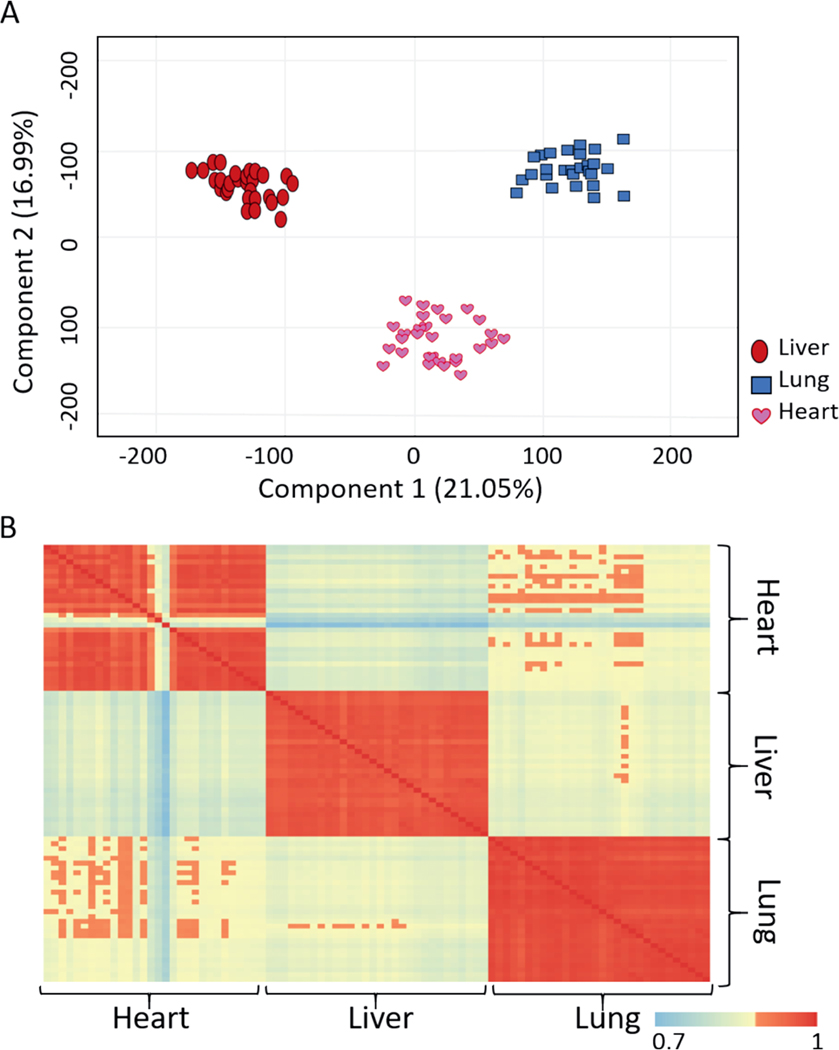

Unique Gene Expression Profiles Observed in Heart, Lung and Liver Samples

Microarray data were analyzed along dose and survival variables. The number of probes that passed the filtering criteria for either dose or survival variable at each statistical analysis step is listed in Table 2 for all the organs. PCA was performed using the normalized intensity values and before applying any filtering criteria illustrating the specificity of heart, lung, and liver gene expression profiles (Fig. 2), regardless of the dose administered to the minipig. All samples clustered into groups according to the tissue type (Fig. 2A). A similar observation was made by computing Pearson’s correlation coefficients between the samples using the normalized unfiltered data (Fig. 2B).

TABLE 2.

Stepwise Summary of the Microarray Data

| No. of probes passing filtering criteria |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heart |

Liver |

Lung |

||||

| Dose | Survival | Dose | Survival | Dose | Survival | |

|

| ||||||

| Filtering criteria passed | q < 0.005 | q < 0.005 | q < 0.05 | q < 0.005 | q < 0.05 | q < 0.05 |

| Passed ANOVA; MTC-Benjamini Hochberg | 399 | 1,067 | 1,036 | 4,024 | 126 | 1,440 |

| Passed fold change (|FC| > 2) | 166 | 937 | 809 | 3,346 | 104 | 1,175 |

Notes. Data were analyzed along dose and survival variables. One-way ANOVA followed by Benjamini Hochberg test for multiple testing correction was performed along either dose or survival in the tissue types separately; absolute fold change value was set at 2.

FIG. 2.

Differences in the gene expression profiles of different organs. Panel A: 2-D principal component analysis was performed in GeneSpring to visualize differences among all tissue samples based on the normalized data values. Panel B: Pearson’s correlation coefficients matrices show the extent of correlation across all samples based on the normalized data values. Correlation coefficient values ranged from 0.7 and 1.

Larger Gene Expression Differences were Observed along Survival Variables than between the Dose Classes

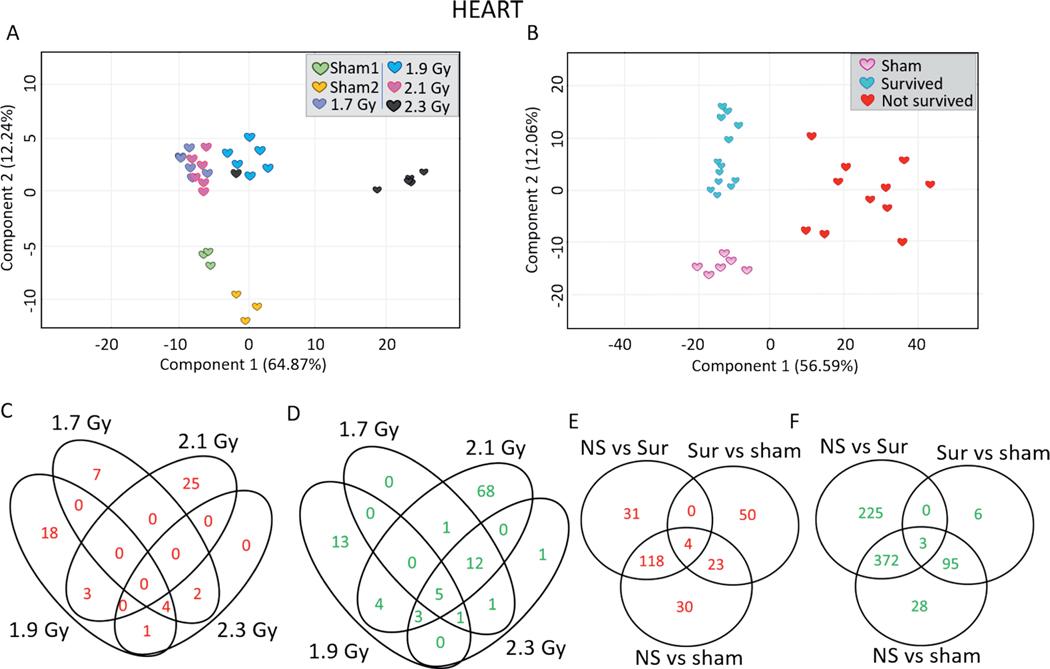

Heart.

PCA using only the heart samples illustrated the similarity in gene expression within the survived, non-survived, and control animal groups (Fig. 3B). The dose group PCA did not illustrate the same neatness of separation (Fig. 3A). In response to 1.7, 1.9, 2.1 and 2.3 Gy, different numbers of probes were upregulated (13, 26, 28 and 7 probes, respectively) and downregulated (20, 26, 94 and 23 probes, respectively) (Fig. 3C and D). The list of dose-dependently regulated probes in the heart samples is shown in Supplementary Table S1 (https://doi.org/10.1667/RADE20-00123.1.S2). Gene expression of 175 probes was significantly differentially induced in non-survivors compared to control animals; 153 probes were significantly differentially induced in non-survivors compared to survivors; 118 probes were significantly induced in the non-surviving animals compared to both control and surviving animals (Fig. 3E). A total of 600 probes were significantly differentially repressed in non-survivors compared to control animals; 498 probes were significantly differentially repressed in non-survivors compared to survivors; 372 probes were significantly differentially repressed in non-survivors compared to both control and surviving animals (Fig. 3F). The list of survival-dependently regulated probes in the heart samples is shown in Supplementary Table S2 (https://doi.org/10.1667/RADE-20-00123.1.S3). To capture inter-animal variabilities, scatter plots were generated for the top 10 most highly induced annotated probes in non-survivors compared to both control and surviving animals (Supplementary Fig. S1; https://doi.org/10.1667/RADE-20-00123.1.S1). These probes were ACKR4 (atypical chemokine receptor 4), MT1A (metallothionein 1A), ACP5 (acid phosphatase 5), GPNMB (glycoprotein NMB), HMOX1 (heme oxygenase 1), PDK4 (pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 4), ARNTL (aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator like), CHIA (chitinase acidic), CD163 (cluster of differentiation 163) and SERPINE1 (serpin family E member 1). The top 10 most significantly differentially repressed probes of non-survivors versus control and survivors were CRABP (cellular retinoic acid binding protein 1), INHA (inhibin A), MASP1, FBXL22, RASGEF1A (RasGEF domain family member 1A), KCNJ3 (potassium inwardly rectifying channel subfamily J member 3), ANGPT1 (angiopoietin 1), NREP (neuronal regeneration-related protein), C1QTNF3 (complement C1q <tumor necrosis factor-related protein 3) and CPNE6 (copine 6) (Supplementary Fig. S2; https://doi.org/10.1667/RADE-20-00123.1.S1). The complete list of probes differentially expressed in the hearts of non-survivors compared to the hearts of both survivors and control animals is provided in Supplementary Table S3 (https://doi.org/10.1667/RADE20-00123.1.S4).

FIG. 3.

Differential gene expression profiles in the minipig heart samples along dose and survival variables. 2-D principal component analysis was performed in GeneSpring to visualize differences among different heart samples along (panel A) dose and (panel B) survival variables. Panel C: Venn diagram comparing the lists of the upregulated probes in the heart samples in response to all doses compared to sham-irradiated animals. Panel D: Venn diagram comparing the lists of the downregulated probes in the heart samples across all the doses compared to sham-irradiated animals. Panel E: Venn diagram comparing the lists of upregulated probes among non-survivors, survivors and sham-irradiated animals. Panel F: Venn diagram comparing the lists of downregulated probes among non-survivors, survivors and control animals. Upregulated probes passed the criteria of Tukey’s HSD P < 0.005 and FC > 2 while downregulated probes passed the criteria of Tukey’s HSD P < 0.005 and FC < −2.

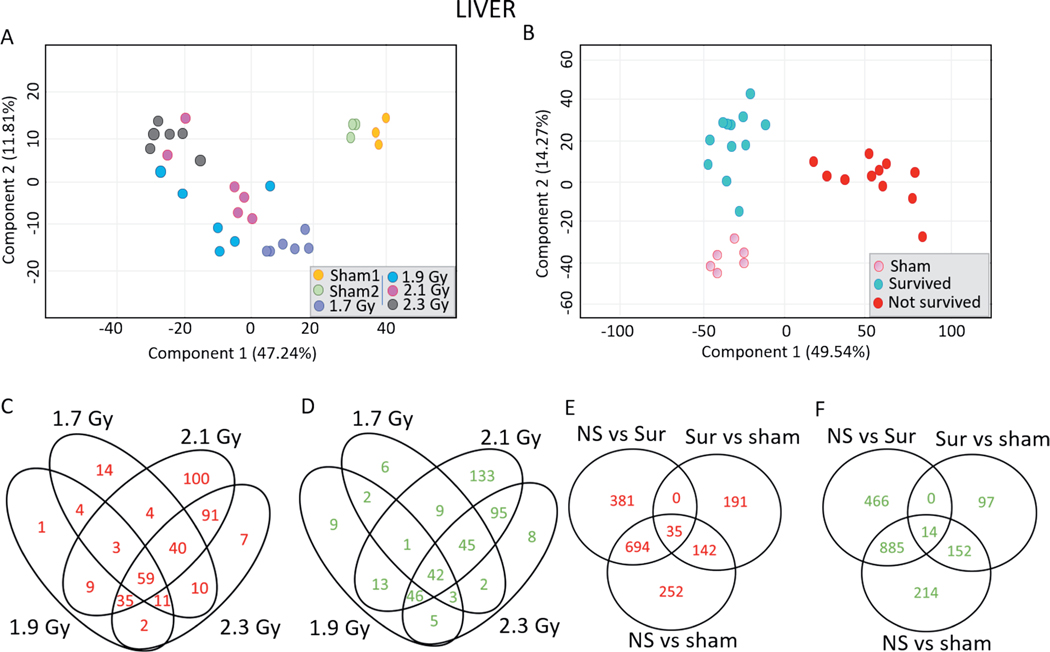

Liver.

Liver gene expression in response to TBI follows a similar pattern to that observed in the heart, as PCA again illustrated greater similarity in gene expression profiles within the survived, non-survived, and control animal groups compared to the similarities within the dose groups (Fig. 4A and B). In response to 1.7, 1.9, 2.1 and 2.3 Gy, different numbers of probes were upregulated (145, 124, 341 and 275 probes, respectively) and downregulated (110, 121, 344 and 246 probes, respectively) in the liver (Fig. 4C and D). The list of dose-dependently regulated probes in the liver samples is shown in Supplementary Table S4 (https://doi.org/10.1667/RADE-20-00123.1.S5). A total of 59 probes were upregulated, and 42 probes were downregulated in all the dose groups compared to sham-irradiated animals. Expression of 1,123 probes was found to be significantly differentially overexpressed in the liver samples of non-survivors compared to control animals; 1,120 probes were overexpressed in non-survivors compared to survivors; and 694 probes were overexpressed in the non-survivors compared to both control animals and survivors (Fig. 4E). There were 1,265 probes significantly downregulated in the non-survivors compared to control animals while 1,365 probes were significantly downregulated in the non-survivors compared to the survivors, of which 885 probes were also downregulated in the non-survivors compared to control animals (Fig. 4F). The list of survival-dependently regulated probes in the liver samples is shown in Supplementary Table S5 (https://doi.org/10.1667/RADE-20-00123.1.S6). The top 10 most significantly induced probes in the liver samples of non-survivors compared to both control animals and survivors were SLC38A1 (solute carrier family 38 member 1), EPO (erythropoietin), SAA3 (serum amyloid A3), SAA2 (serum amyloid A), NNMT (nicotinamide N-methyltransferase), GDF15 (growth and differentiation factor 15), SYT16 (synaptotagmin), HAL (histidine ammonia-lyase), UPK1B (uroplakin 1B) and GATA3 (GATA binding protein 3) (Supplementary Fig. S3; https://doi.org/10.1667/RADE-20-00123.1.S1). The top most significantly downregulated probes in the non-survivors compared to control and surviving animals were DIO2 (iodothyronine deiodinase 2), CYP2B22 (cytochrome P450 2B22), TTC23L (tetratricopeptide repeat domain 23 like), PNPLA3 (patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing protein 3), PHGDH (phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase), ACSS2 (acyl Co-A synthetase), SCD (stearoyl-CoA desaturase), PAQR7 (progestin and adipoQ <receptor family member 7), CYP2C42 (cytochrome P450 2C42) and ALB (albumin) (Supplementary Fig. S4). The complete list of probes differentially expressed in the livers of non-survivors compared to the livers of both survivors and control animals is provided in Supplementary Table S6 (https://doi.org/10.1667/RADE-20-00123.1.S7).

FIG. 4.

Differential gene expression profiles in the minipig liver samples along dose and survival variables. 2-D principal component analysis was performed in GeneSpring to visualize differences among different liver samples along (panel A) dose and (panel B) survival variables. Panel C: Venn diagram comparing the lists of the upregulated probes in the liver samples in response to all doses compared to control animals. Panel D: Venn diagram comparing the lists of the downregulated probes in the liver samples across all the doses compared to control animals. Panel E: Venn diagram comparing the lists of upregulated probes among non-survivors, survivors and control animals. Panel F: Venn diagram comparing the lists of downregulated probes among non-survivors, survivors and control animals. Upregulated probes passed the criteria of Tukey’s HSD P < 0.005 and FC > 2, while downregulated probes passed the criteria of Tukey’s HSD P < 0.005 and FC < −2.

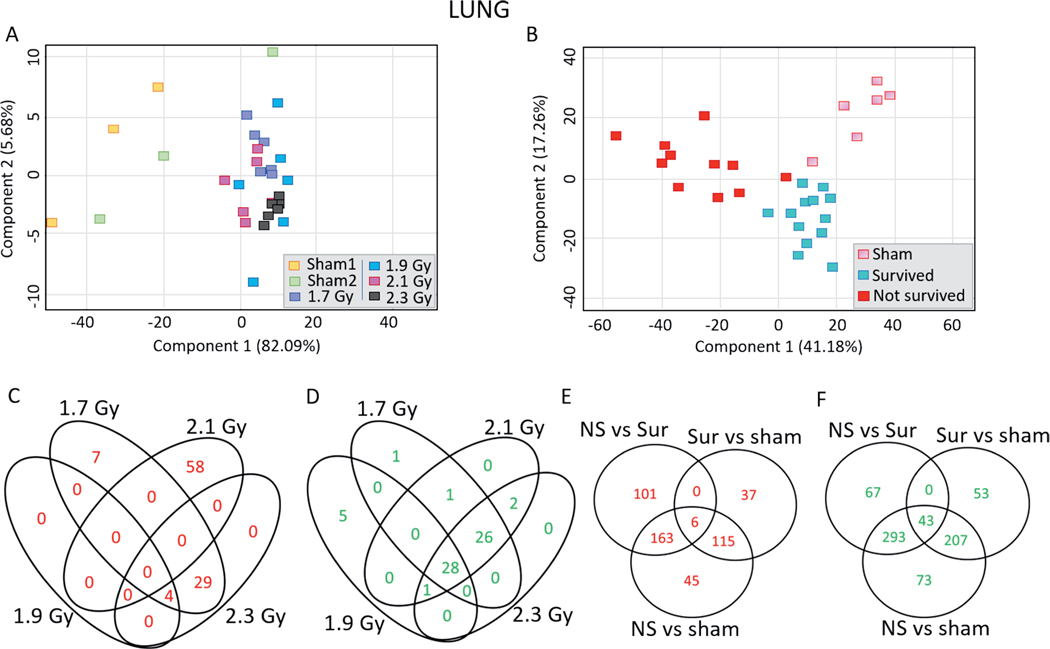

Lungs.

PCA of the lung samples illustrated similarities in differential gene expression between the dose groups: the different dose groups were separated from the sham animals but inseparable from each of the other doses (Fig. 5A). Survivors, non-survivors and control animals also clustered separately, though with less distinction than the heart and liver analyses (Fig. 5B). In response to 1.7, 1.9, 2.1 and 2.3 Gy, different numbers of probes were upregulated (40, 4, 58 and 33 probes, respectively) and downregulated (56, 34, 58 and 57 probes, respectively) in the lung samples (Fig. 5C and D). The list of dose-dependently regulated probes in the lung samples is provided in Supplementary Table S7 (https://doi.org/10.1667/RADE-20-00123.1.S8). There were 329 probes significantly differentially induced in the lung samples of non-survivors compared to control animals, while 270 probes were induced in the non-survivors compared to survivors and 163 probes induced in the non-survivors compared to both control animals and survivors (Fig. 5E). Expression of 616 probes was significantly differentially downregulated in the non-survivors compared to the control animals, while 403 probes were downregulated in the non-survivors compared to the survivors and 293 probes were downregulated in the non-survivors compared to both control animals and survivors (Fig. 5F). The list of survival dependently-regulated probes in the lung samples is provided in Supplementary Table S8 (https://doi.org/10.1667/RADE-20-00123.1.S9). The most significant and highly induced probes in non-survivors compared to both control animals and survivors were HAL (histidine ammonia-lyase), TPO (thyroid peroxidase), SHMT1 (serine hydroxymethyltransferase), LPL (lipoprotein lipase), PDK4 (pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 4), ARNTL (aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator like), ART3 (ADP-ribosyltransferase 3), CD163 (cluster of differentiation 163), GALNT15 (N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase 15) and MAPK10 (mitogen activated protein kinase 10) (Supplementary Fig. S5; https://doi.org/10.1667/RADE-20-00123.1.S1). The most significant and highly downregulated probes in non-survivors compared to both control animals and survivors were CLEC1B (C-type lectin domain family 1 member B), WISP2 (WNT1 inducible signalling pathway), CMTM5 (CKLF-like MARVEL transmembrane domain-containing protein 5), TRIM55 (tripartite motif containing 55), XIRP2 (xin actin binding repeat containing 2), GP1BB (glycoprotein Ib platelet subunit beta), TF (transferrin), SMPX (small muscle protein X-linked), ABCC8 (ATP binding cassette subfamily C member 8) and MMP9 (matrix metallopeptidase 9) (Supplementary Fig. S6; https://doi.org/10.1667/RADE-20-00123.1.S1). The complete list of probes differentially expressed in the lung samples of non-survivors compared to the lung samples of both survivors and control animals is provided in Supplementary Table S9 (https://doi.org/10.1667/RADE-20-00123.1.S10).

FIG. 5.

Differential gene expression profiles in the minipig lung samples along dose and survival variables. 2-D principal component analysis was performed in GeneSpring to visualize differences among different liver samples along (panel A) dose and (panel B) survival variables. Panel C: Venn diagram comparing the lists of the upregulated probes in the lung samples in response to all doses compared to sham-irradiated animals. Panel D: Venn diagram comparing the lists of the downregulated probes in the lung samples across all the doses compared to sham-irradiated animals. Panel E: Venn diagram comparing the lists of upregulated probes among non-survivors, survivors and sham-irradiated animals. Panel F: Venn diagram comparing the lists of downregulated probes non-survivors, survivors and sham-irradiated animals. Upregulated probes passed the criteria of Tukey’s HSD P < 0.005 and FC > 2, while downregulated probes passed the criteria of Tukey’s HSD P < 0.005 and FC >, −2.

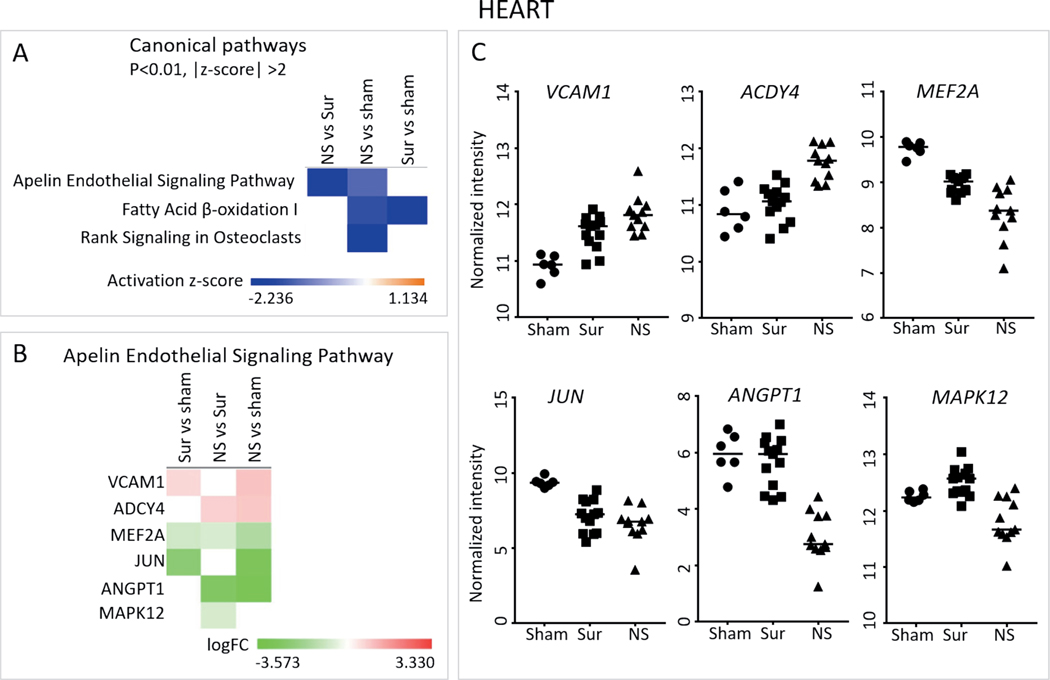

Apelin Endothelial Signaling Pathway Predicted to be Downregulated in the Hearts of Non-Survivors

To identify pathways deregulated in a survival-dependent manner, the significantly differentially expressed gene lists from the heart samples were analyzed using the IPA core analysis. Fatty acid β-oxidation was predicted to be downregulated in all irradiated animals compared to control animals, and RANK signaling in osteoblasts was downregulated in the non-survivors compared to control animals (Fig. 6A). The apelin endothelial signaling pathway was downregulated in non-survivors compared to both control animals and survivors (Fig. 6A). The six genes belonging to the apelin endothelial signaling pathway which were differentially regulated were VCAM1 (vascular cell adhesion molecule-1), ADCY4 (adenylate cyclase 4), MEF2A (myocyte-specific enhancer factor 2A), JUN (Jun proto-oncogene), ANGPT1 (angiopoietin 1) and MAPK12 (mitogen activated protein kinase 12) (Fig. 6B and C). Of these, MEF2A, JUN, ANGPT1 and MAPK12 were downregulated in the non-survivors compared to both survivors and control animals. Notably, no pathway was predicted to be activated in either the survivors or the non-survivors compared to control animals.

FIG. 6.

Canonical pathways differentially regulated in the hearts of non-survivors. Panel A: The three gene lists comprising the comparisons of non-survivors vs. survivors, non-survivors vs. control and survivors vs. control animals from the heart gene expression data were analyzed using IPA to identify pathways differentially regulated among them. Heat map showing the three canonical pathways that passed the P < 0.01 and absolute z-score > 2 cutoffs. Panel B: Heat map showing the log fold change values of genes belonging to the apelin endothelial signaling pathway across the three different comparisons. Panel C: Scatter plots show the normalized intensity values over all the control animals, survivor and non-survivor samples of the genes in panel B. Median intensity values are represented with a horizontal line. Closed circles, squares and triangles represent control animals, survivors and non-survivors, respectively.

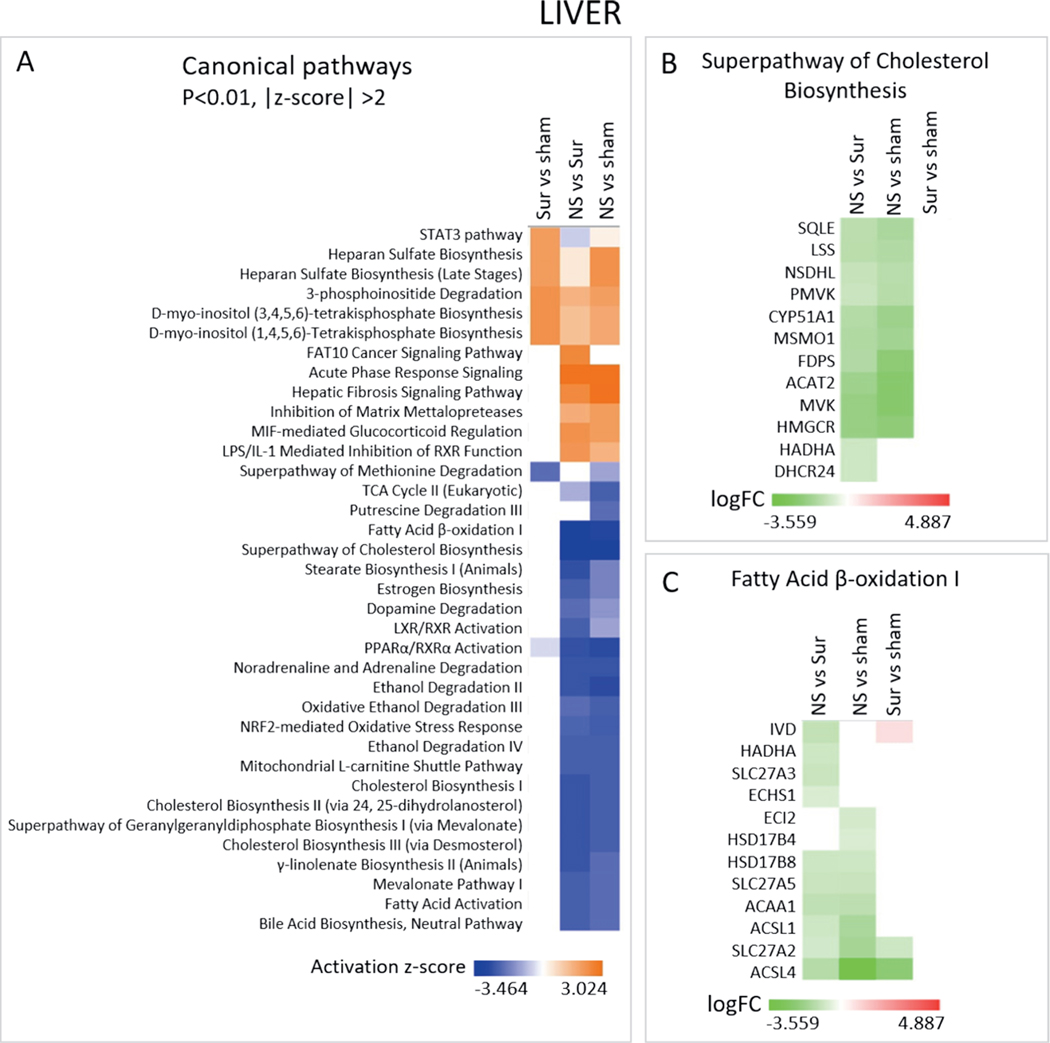

Lipid Metabolism-Related Pathways were Downregulated in the Livers of Non-Survivors

Lipid metabolism-related canonical pathways, such as cholesterol biosynthesis, fatty acid β-oxidation, estrogen biosynthesis and mevalonate biosynthesis, were predicted to be downregulated in the liver samples of non-survivors compared to both survivors and control animals (Fig. 7A). Superpathway of cholesterol biosynthesis and fatty acid β-oxidation I were predicted to be the most deactivated as they had the lowest z score (Fig. 7A). Twelve genes belonging to the superpathway of cholesterol biosynthesis were downregulated in the non-survivors compared to both survivors and control animals (Fig. 7B and Supplementary Fig. S7; https://doi.org/10.1667/RADE-20-00123.1.S1) and 12 genes involved in fatty acid β-oxidation I were also downregulated in the non-survivors compared to both survivors and control animals (Fig. 7C and Supplementary Fig. S8; https://doi.org/10.1667/RADE-20-00123.1.S1). Lipid metabolism and storage processes were also predicted as downregulated in the liver samples of non-survivors compared to both survivors and control animals in the “Diseases and Biofunctions” sub-analysis, while the “Toxicological Functions” analysis identified both activated and deactivated functions related to hepatocyte injury in the non-survivors compared to both survivors and control animals (Supplementary Fig. S9A and B; https://doi.org/10.1667/RADE-20-00123.1.S1). Interestingly, genes leading to increased levels of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) were found to be induced more in the liver samples of non-survivors compared to both survivors and control animals (Supplementary Fig. S9C).

FIG. 7.

Canonical pathways differentially regulated in the livers of non-survivors. Panel A: The three gene lists comprising the comparisons non-survivors vs. survivors, non-survivors vs. controls and survivors vs. controls from the liver gene expression data were analyzed using IPA to identify pathways differentially regulated among them. Heat map shows the canonical pathways that passed the P < 0.01 and absolute z-score > 2 cutoffs. Panel B: Heat map depicting the log fold change values of genes belonging to the superpathway of cholesterol biosynthesis across the three different comparisons. Panel C: Heat map showing the log fold change values of genes belonging to the fatty acid β-oxidation I pathway.

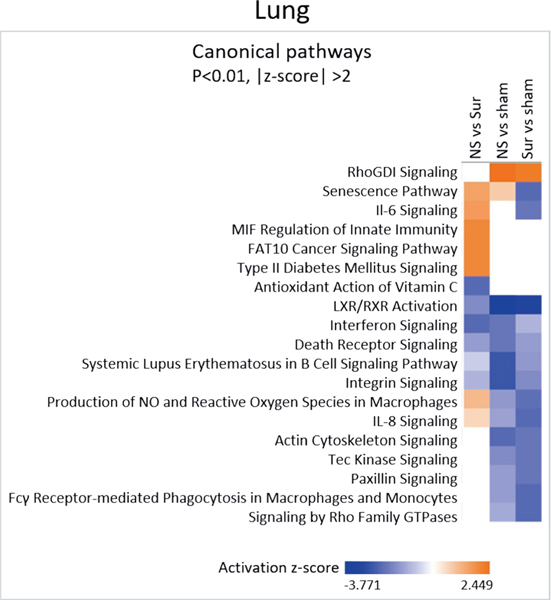

Immune-Related Signaling Pathways were Downregulated in the Lungs of All Irradiated Animals

Immune function-related pathways such as IL-8 signaling, death receptor signaling and phagocytosis in macrophages and monocytes were downregulated in the lung samples of both non-survivors and survivors compared to control animals (Fig. 8). No pathways were deregulated only in the non-survivors compared to both survivors and control animals.

FIG. 8.

Canonical pathways differentially regulated in the lungs of non-survivors. The three gene lists comprising the comparisons non-survivors vs. survivors, non-survivors vs. controls and survivors vs. controls from the lung gene expression data were analyzed using IPA to identify pathways differentially regulated among them. Heat map shows the canonical pathways that passed the P < 0.01 and absolute z-score > 2 cutoffs.

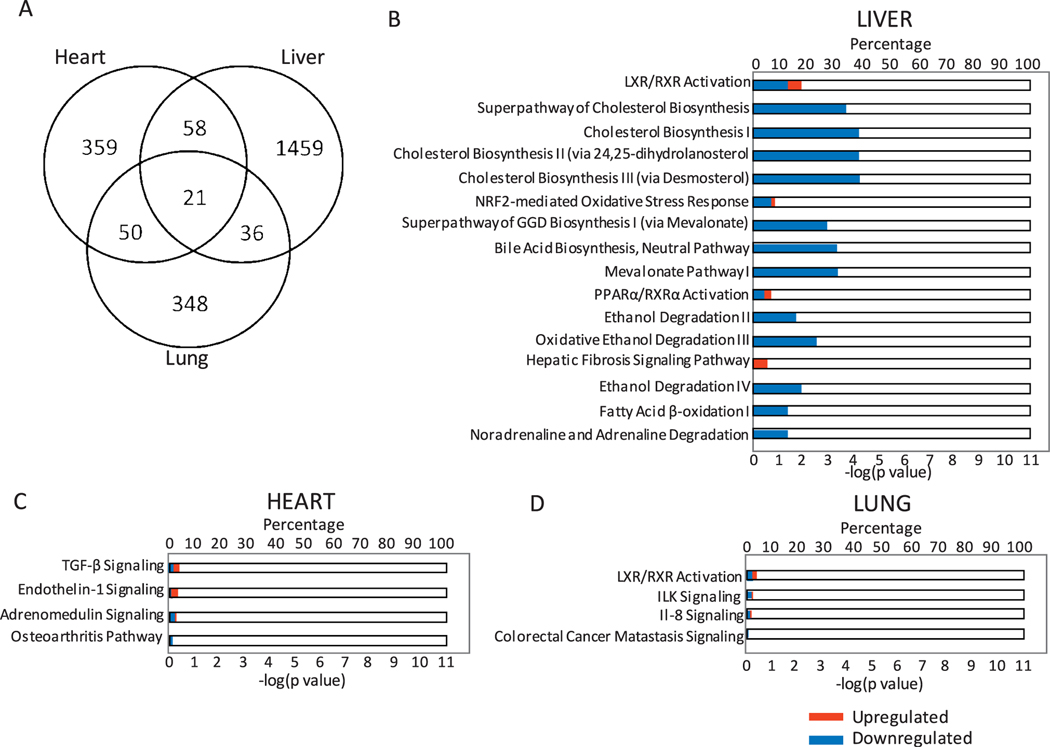

Non-Overlapping Gene Expression Profiles in the Three Different Organs of Non-Survivors

It was initially observed that organs have distinct gene expression profiles (Fig. 2). To further understand whether there is any similarity in the radiation response among the three organs of the non-survivors, we compared the gene expression profiles differentially expressed in non-survivors to both survivors and control animals across the three tissue types (Fig. 9A; comparison of the Supplementary Tables S1–S3). Only 21 probes were found to be differentially regulated in all the organs tested of the non-survivors compared to both survivors and control animals. The majority of the differentially expressed genes did not overlap across any of the organ types, with 359, 1,459 and 348 probes exclusively regulated in the heart, liver and lung samples, respectively. Canonical pathways affected by these exclusive genes were identified for the three organs using IPA. The 1,459 probes deregulated only in the liver samples of non-survivors were involved mostly in cholesterol biosynthesis pathways. Other predicted signaling pathways affected included ethanol degradation, fatty acid β-oxidation and LXR/RXR activation, among others (Fig. 9B). Interestingly, most of these probes were downregulated, resulting in a net deactivation of the respective pathways. The heart-exclusive probes were involved in TGF-β signaling, endothelin-1 signaling, adrenomedullin signaling and the osteoarthritis pathway (Fig. 9C). The liver-exclusive probes were involved in LXR/RXR activation, ILK signaling, IL-8 signaling and colorectal cancer metastasis signaling (Fig. 9D).

FIG. 9.

Inter-organ comparison of the non-survivors with survivors and control animals. Panel A: Venn diagram shows the number of unique and overlapping probes among the heart, liver and lung tissues of the non-survivors compared to both survivors and control animals. Panel B: Canonical pathway terms associated with the 1,459 probes unique to the liver samples of non-survivors compared to both survivors and control animals. Panel C: Canonical pathway terms associated with the 359 probes unique to the heart samples of non-survivors compared to both survivors and control animals. Panel D: Canonical pathway terms associated with the 348 probes unique to the lung samples of non-survivors compared to both survivors and control animals. In panels B, C and D, the upper x-axis represents the percentage of genes from the related pathway found in the corresponding probe list. The lower x-axis represents the enrichment P value. Red corresponds to upregulated genes and blue corresponds to downregulated genes.

Prediction Models Built to Differentiate Non-Survivors, Survivors and Sham-Irradiated Animals

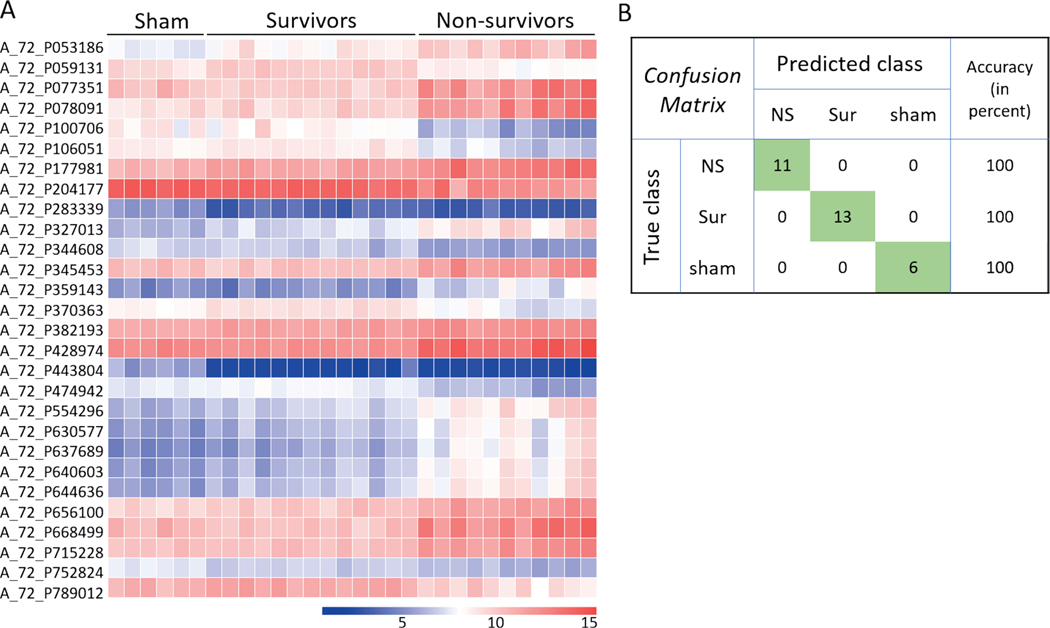

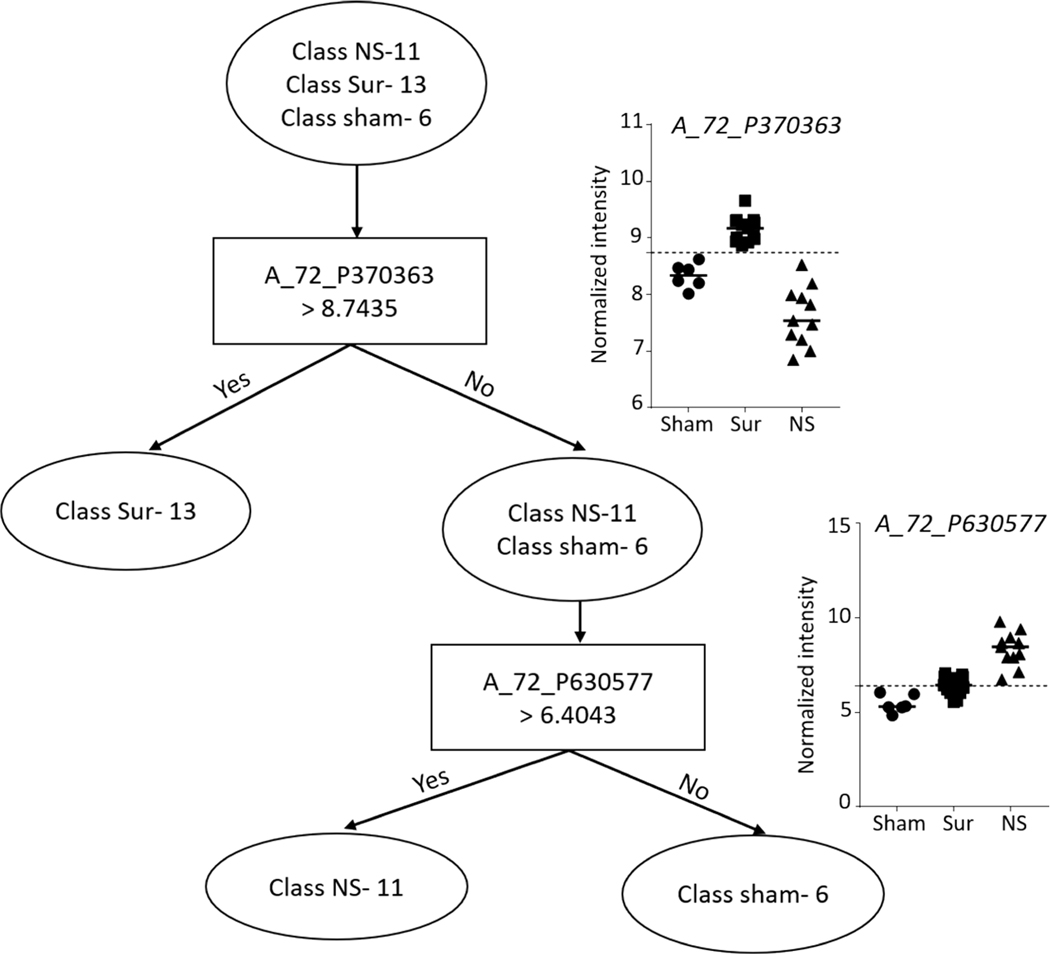

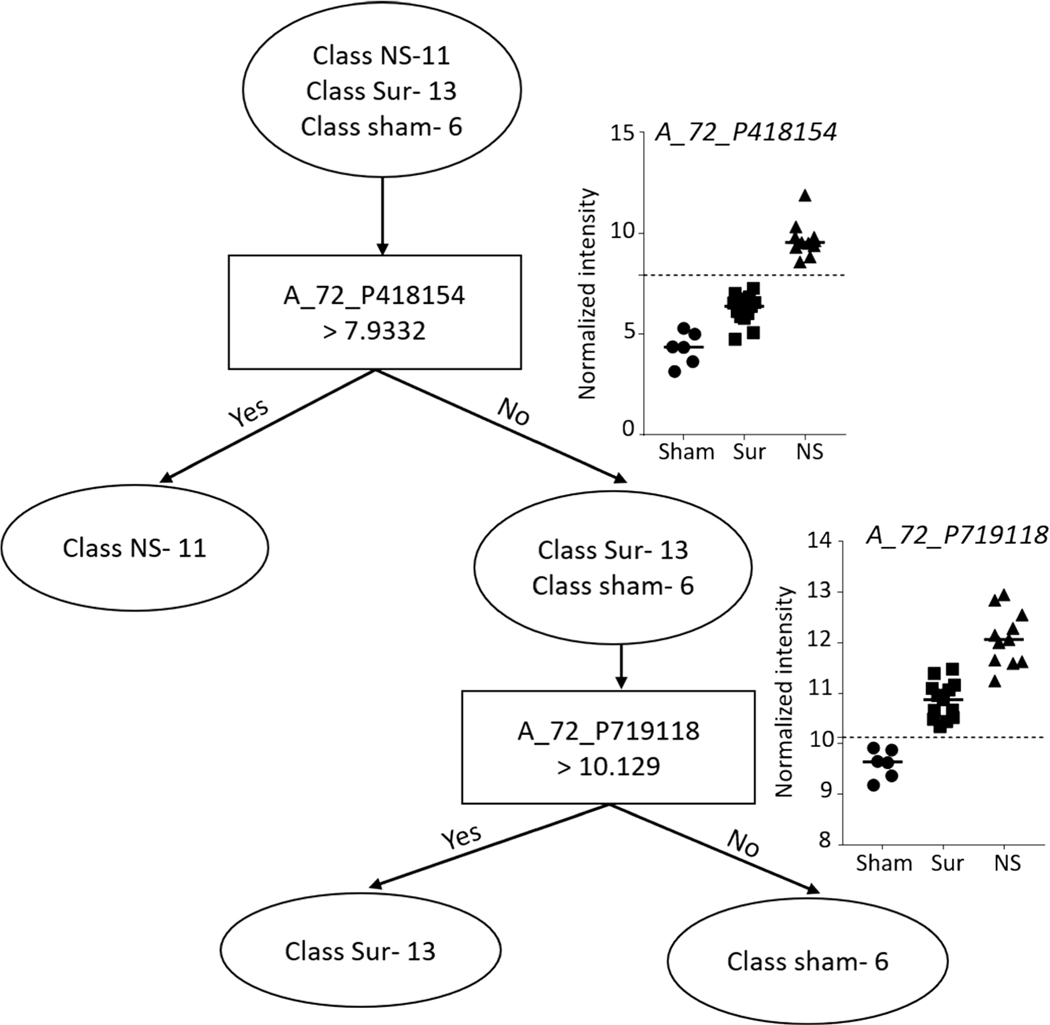

Heart.

Prediction analysis was performed using the naïve Bayes classification algorithm and decision tree classifier. A total of 28 probes (P < 10−6, |FC|>2) were selected to build a naïve Bayes classifier of survivor, non-survivor and control groups using only the heart samples. Cross-validated model accuracy was estimated at 100% (Fig. 10). A decision tree based on two probes resulted in clear separation of the three different classes into three branches (Fig. 11).

FIG. 10.

Naïve Bayes classifier based on heart gene expression data for differentiating non-survivors from survivors and control animals. Panel A: Heat map showing the expression intensities across all samples of the 28 probes on which the naïve Bayes classifier was built and tested in GeneSpring. Probes were selected based on the cutoffs: P ≤ 10−6 and |FC| > 2. Panel B: Confusion matrix showing the prediction accuracies of the three classes based on the classifier in panel A.

FIG. 11.

Decision tree classifier on heart gene expression data for differentiating non-survivors from survivors and control animals. Decision tree algorithm-built classifier comprising two probes in GeneSpring to separate the three classes into three clear branches. The graphs at the branches show the intensity values of the selected probes across all the samples.

Liver.

Prediction analysis was performed using the naïve Bayes classification algorithm and decision tree classifier. A total of 24 probes (P < 10–7, |FC|>2) were selected to build a naïve Bayes classifier from the liver samples to predict all three classes, i.e., non-survivors, survivors and control, with 100% accuracy (Fig. 12). A decision tree based on two probes resulted in clear separation of the three different classes into three branches (Fig. 13).

FIG. 12.

Naïve Bayes classifier based on liver gene expression data for differentiating non-survivors from survivors and control animals. Panel A: Heat map showing the expression intensities across all samples of the 24 probes on which the naïve Bayes classifier was built and tested in GeneSpring. Probes were selected based on the cutoffs: P ≤ 10−7 and |FC| > 2. Panel B: Confusion matrix showing the prediction accuracies of the three classes based on the classifier in panel A.

FIG. 13.

Decision tree classifier on liver gene expression data for differentiating non-survivors from survivors and control animals. Decision tree algorithm-built classifier comprising two probes in GeneSpring to separate the three classes into three clear branches. The graphs at the branches show the intensity values of the selected probes across all the samples.

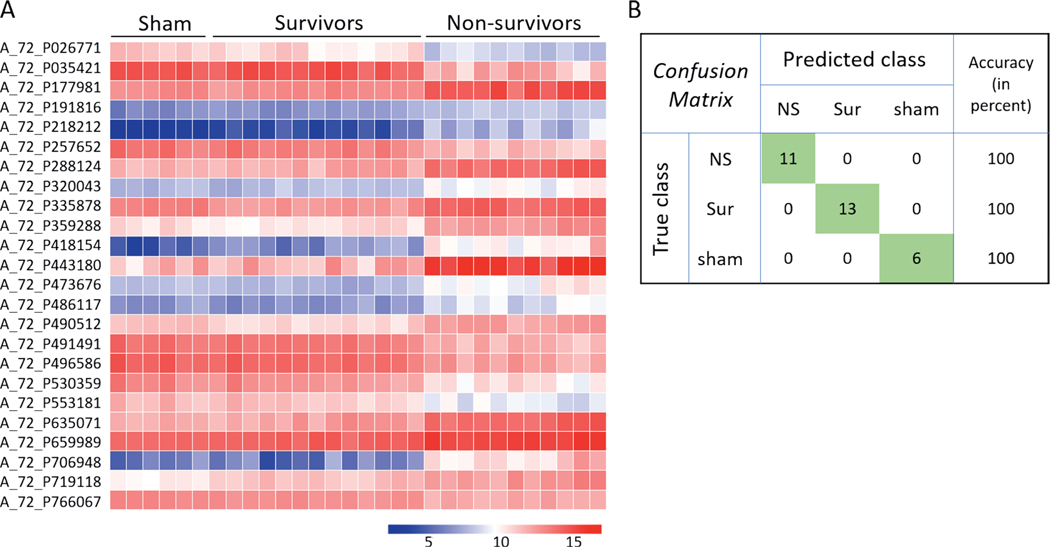

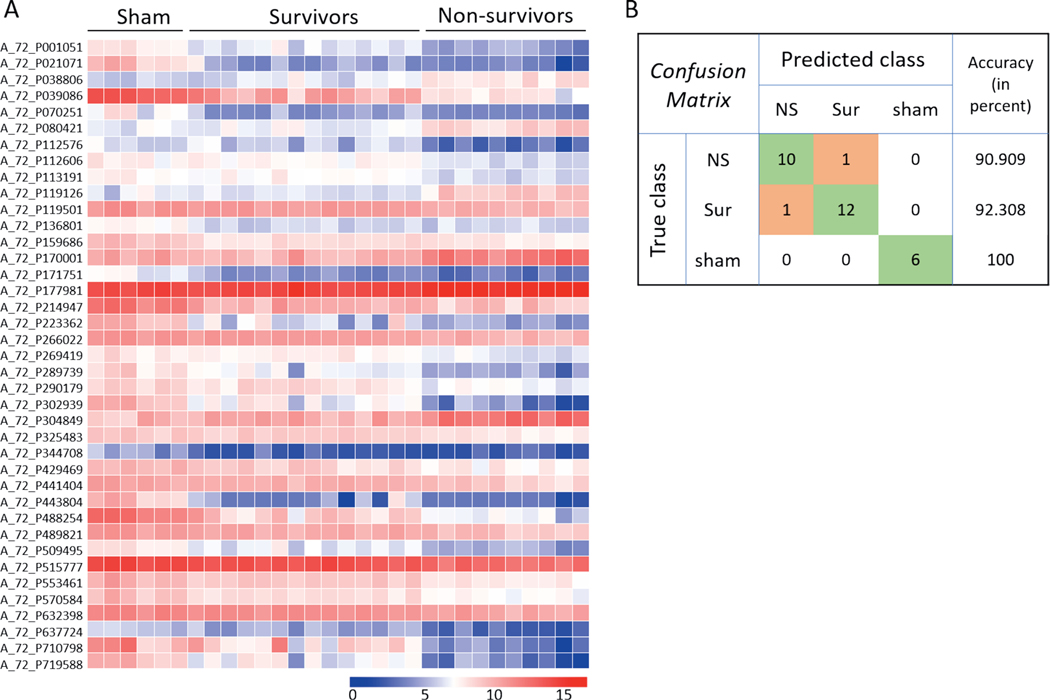

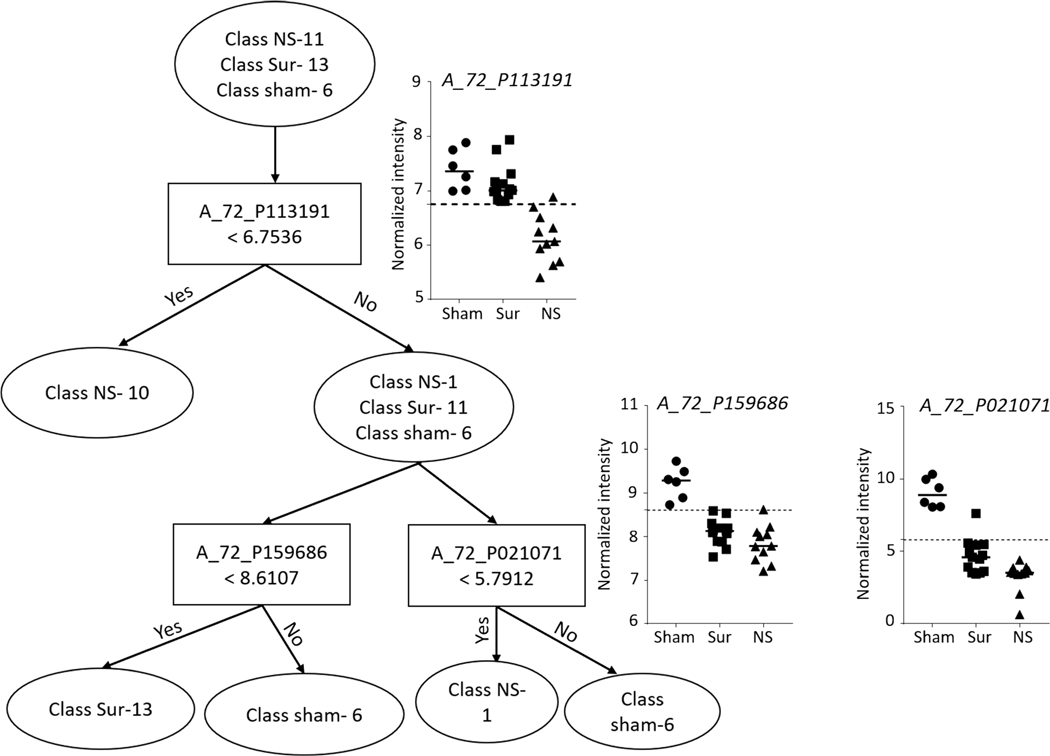

Lung.

Prediction analysis was performed using the naïve Bayes classification algorithm and decision tree classifier. A total of 39 probes (P < 10−3, |FC|>2) were selected to build a naïve Bayes classifier from the lung samples to predict all the control samples with 100% accuracy, while non-survivors and survivors were predicted with accuracies of 90.9 and 92.3%, respectively (Fig. 14). A decision tree based on three probes resulted in separation of the three different classes into five branches (Fig. 15).

FIG. 14.

Naïve Bayes classifier based on lung gene expression data for differentiating non-survivors from survivors and control animals. Panel A: Heat map showing the expression intensities across all samples of the 39 probes on which the naïve Bayes classifier was built and tested in GeneSpring. Probes were selected based on the cutoffs: P ≤ 103 and |FC| > 2. Panel B: Confusion matrix showing the prediction accuracies of the three classes based on the classifier in panel A.

FIG. 15.

Decision tree classifier on lung gene expression data for differentiating non-survivors from survivors and control animals. Decision tree algorithm-built classifier comprising three probes in GeneSpring to separate the three classes into five branches. The graphs at the branches show the intensity values of the selected probes across all the samples.

DISCUSSION

While rigorous efforts are underway to identify blood-based markers for total- and partial-body irradiations, until now no attempts have been made to assess specific damage to vital organs using gene expression profiles. The current work highlights the gene expression profile changes in heart, liver and lungs in response to TBI in a Göttingen minipig model. The data showed that each organ displayed a distinct gene expression profile. Furthermore, the data showed that responses to radiation for both surviving and non-surviving animals are also distinct for different organs. These findings explain the observation that peripheral blood signatures depend on the anatomic site irradiated after partial-body irradiation (28).

A larger number of gene expression changes were observed when animals were compared by survival status rather than radiation dose for all three organs. The organs of non-surviving animals displayed gene expression perturbations compared to both surviving and control animals. It is possible that the differences observed were due to different time points postirradiation at which organs were collected (between days 15 and 28 for the non-survivors, and after day 45 for both survivors and control animals). However, the homogeneity of gene expression observed within the non-surviving class despite varying time points of organ harvest suggests otherwise. Moreover, of the 11 decedents, two animals died at day 15, two at day 16, one at day 17s, three at day 18, two at day 20 and one at day 28. Therefore, comparisons could not be made separately for each day of survival since ‘n’ per day would be too small to perform robust statistical analysis.

The differences between the three survival classes within each tissue sample were so pronounced that the gene signatures identified for predicting survival class (non-survivors, survivors or control) using naïve Bayes algorithm yielded 100% accuracies for both heart and liver data and >90% accuracy for lung data. Naïve Bayes is a type of probabilistic classifier based on the Bayes theorem and assumes independence between the features. The models were cross-validated using an iterative train/test approach called leave-one-out cross validation (LOOCV), where the data is iteratively divided into training and test sets for deriving the optimal generalizable model for class prediction. Since microarrays were performed in two batches and same controls were included in both batches, duplication of control samples could have led to an overestimation of prediction accuracies. Nonetheless, the signatures identified by this approach could potentially pave the way for triaging irradiated individuals for organ-specific damage. It is essential to note, however, that these differences are derived from animals (non-survivors particularly) whose conditions had considerably deteriorated. It remains to be tested whether these signatures would hold true at earlier time points when medical countermeasures could theoretically be delivered to mitigate progression of injury. Additionally, the decision trees constructed for heart and liver were each comprised of two probes, while the tree constructed for lung was comprised of three probes. The decision trees are based entirely on the given set of data and might be overfit to this specific dataset.

We observed survival-dependent changes in histopathological and clinical parameters (Supplementary Fig. S10; https://doi.org/10.1667/RADE-20-00123.1.S1). To examine if gene expression signatures for predicting survival correlated with these parameters as well, we computed Pearson’s correlation coefficients for all probes in the organ-specific signature with the same organ’s histological parameter (Supplementary Table S10; https://doi.org/10.1667/RADE-20-00123.1.S11). The greatest correlation was observed between the lung gene expression signature and FL staining of the lung tissue (30 out of 39 probes were either positively or negatively correlated with the FL grade in the lung tissue). It is an interesting correlation since morphologically, lungs of most survivors and decedents had displayed abnormalities and no distinctions could be made based solely on lung morphology (Table 2). In the liver, six probes of the total 24 in the liver gene expression signature significantly correlated with the Perl’s iron staining grade found in the Kupffer cells. Liver tissue did not display gross morphological abnormalities as well (Table 2), while we did observe depression in normal liver functions (Supplementary Fig. S10D–F; https://doi.org/10.1667/RADE-20-00123.1.S1). It follows that the captured gene expression changes in the liver might predate occurrence of gross histological changes, suggesting that mere absence of morphological abnormalities does not discount the fact that the organ might still be severely damaged. In the heart tissue, five of the 28 probes in the heart-specific gene expression signature significantly correlated with the FL staining in the heart. It is not surprising since fibrin accumulation in the hearts was not significantly dependent on survival status. On the other hand, hearts of non-survivors did display gross morphological abnormalities compared to survivors (Table 2).

The liver was identified as the most affected organ in the non-survivors in response to TBI based on differential gene expression profiling. This finding is not surprising since radiation-induced liver disease has long been identified as a limiting factor in the use of radiotherapy for liver cancers (30–32). Liver proteome was also affected in neonatal mice that received low-dose TBI (33). Radiation-induced liver injury has previously been identified in Göttingen minipigs (34).

Several genes related to detoxification pathways (e.g., ethanol oxidation) were found to be downregulated in the liver samples of non-surviving animals compared to surviving and control animals. Several genes encoding enzymes involved in lipid metabolism and that are abundantly expressed in the livers of healthy individuals, such as acetyl CoA synthetase (35) and stearoyl CoA desaturase (36), were also found to be highly downregulated in response to TBI in liver samples of non-surviving animals. This explains why lipid metabolism-related pathways and processes were predicted by the IPA analysis to be deregulated in the liver samples of non-survivors. These differences might lead us to believe that the non-survivors could not cope with the damage sustained from radiation, thus causing their morbidity. However, the opposite could be equally true; animals were dying and, therefore, their detoxification and metabolic pathways were depressed. It is difficult to establish cause-and-effect statements from these observations. Nonetheless, these contrasts are noteworthy because morphologically most non-survivors did not display overt morphological abnormalities. At the same time, we observed a survival-dependent decrease in the plasma levels of liver function enzymes, ALT and GGT, suggesting loss of normal liver function in the deceased animals. Moreover, higher levels of iron found in both hepatocytes and Kupffer cells also suggested that the livers of the deceased animals were not functioning optimally.

Although several genes were differentially regulated in the heart samples of non-survivors compared to both survivors and control animals, the apelin endothelial signaling pathway was the only pathway predicted to be downregulated in the non-survivors compared to both survivors and control animals. Interestingly, apelin has previously been associated with cardiovascular diseases (37, 38). Apelin signaling has been shown to be widely expressed in the vascular endothelium and required for endothelial polarization (38, 39). Deactivation of this pathway might therefore be correlated to hemorrhage observed in hearts of non-survivors, possibly as a result of the endothelium degeneration, which has long been associated with radiation induced cardiotoxicity (40, 41). These observations are particularly interesting in light of recently reported findings where Göttingen minipigs were shown to develop resistance to the radioprotective hormone, insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1), in response to TBI (42). Selective IGF1 resistance was associated with hemorrhage in the heart and derailed endothelial homeostasis. Administration of granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) restored sensitivity to IGF1 in the vascular endothelium of the heart, which contributed toward its beneficial effects (43). Apelin endothelial signaling pathway could be explored as another therapeutic target for maintaining endothelial integrity in the heart.

Several genes identified in our study as differentially expressed in heart tissues of the non-surviving animals have previously been linked with cardiovascular diseases. For instance, ACKR4 along with other atypical chemokine receptors were found associated with atherosclerosis (44). Plasma levels of glycoprotein NMB (GPNMB) were significantly reduced in a mouse model of heart failure (45). Elevated PAI1 (plasminogen activator inhibitor1, SERPINE1 gene) levels in blood were associated with coronary heart disease (46).

Immune function-related pathways were found repressed in the lung samples of both survivors and non-survivors compared to the control animals. This is surprising since lung tissue has been known to display an enhanced immune response to various challenges including radiation (47, 48). It is possible that the delayed time point of organ collection when bone marrow has already suffered considerable depletion led to this depression in the immune response in lungs. None of these pathways appear to be differentially regulated in the non-survivors compared to both survivors and control animals. This suggests that contrary to heart and liver where distinct pathways appear to be regulated exclusively in the non-survivors, lungs of all irradiated animals were equally stressed even though morphological abnormalities were observed in the lung samples of non-survivors only. This discrepancy could arise for the following reason: Sus scrofa genome annotations are not comprehensive (49, 50) and pathway predictions were based on the available annotations. It is possible that there are differences in terms of pathways activated between the survivors and non-survivors which were not captured here for lack of complete annotation of the minipig genome.

In this study, we explored gene expression changes inherent to specific organs in TBI Göttingen minipigs. Our work has highlighted that the liver is the most affected organ in terms of gene expression changes and lipid metabolism-related pathways are the most deregulated pathways in the liver samples of non-surviving animals. This information could be used to design therapeutic interventions for rescuing liver function in these animals with potential for application in humans. We are in the process of investigating such interventions using a liver-on-a-chip model in the lab. Histological and gene expression differences observed in the hearts of non-surviving animals suggest that the heart is a major target of radiation-induced injury. We also plan to explore applicability of these signatures for identification of organ damage from serum/plasma. Toward that end, we are continuing to develop circulating RNA markers for conducting biodosimetry (16, 17). Several published studies have identified circulating non-coding RNAs associated with cardiovascular illnesses (51, 52). Concurrent studies in our laboratory are also focused on finding organ-specific circulating coding and non-coding RNA markers of radiation injury. We hypothesize that gene signatures and non-coding RNA signatures, together or separately, would enable prediction of radiation-induced specific organ damage from serum/plasma samples. How soon these markers would manifest after radiation exposure and how this knowledge would be used in medical management are questions that are also being investigated. We contend that studying molecular responses in normal tissue after TBI could provide valuable information in identifying potential targets for mitigation of radiation injury. These findings could also have application in clinical radiation therapy in addition to their utility in assessing extensive partial- and whole-body exposures.

Supplementary Material

Table S1. List of probes differentially expressed in a dose-dependent manner in heart samples of minipigs.

Table S2. List of probes differentially expressed in a survival-dependent manner in heart samples of minipigs.

Table S3. List of probes differentially expressed in the heart samples of non-survivors compared to both survivors and sham-irradiated animals.

Table S4. List of probes differentially expressed in a dose-dependent manner in liver samples of minipigs.

Table S5. List of probes differentially expressed in a survival-dependent manner in liver samples of minipigs.

Table S6. List of probes differentially expressed in liver samples of non-survivors compared to both survivors and sham-irradiated animals.

Table S7. List of probes differentially expressed in a dose-dependent manner in lung samples of minipigs.

Table S8. List of probes differentially expressed in a survival-dependent manner in lung samples of minipigs.

Table S9. List of probes differentially expressed in lung samples of non-survivors compared to both survivors and sham-irradiated animals.

Table S10. Pearson’s correlation coefficients computed between genes in survival signatures and histological grades for each organ.

Fig. S1. Ten most highly induced annotated probes in heart samples of non-survivors compared to both survivors and sham-irradiated animals.

Fig. S2. Ten most highly downregulated annotated probes in heart samples of non-survivors compared to both survivors and sham-irradiated animals.

Fig. S3. Ten most highly induced annotated probes in the liver samples of non-survivors compared to both survivors and sham-irradiated animals

Fig. S4. Ten most highly downregulated annotated probes in the liver samples of non-survivors compared to both survivors and sham-irradiated animals.

Fig. S5. Ten most highly induced annotated probes in the lung samples of non-survivors compared to both survivors and sham-irradiated animals.

Fig. S6. Ten most highly downregulated annotated probes in the lung samples of non-survivors compared to both survivors and sham-irradiated animals.

Fig. S7. Genes belonging to the superpathway of cholesterol biosynthesis downregulated in the liver samples of non-survivors compared to both survivors and sham-irradiated animals.

Fig. S8. Genes belonging to the fatty acid β-oxidation I pathway downregulated in the liver samples of non-survivors compared to both survivors and sham-irradiated animals.

Fig. S9. IPA-identified ‘‘diseases and biofunctions’’ and ‘‘toxicological functions’’ differentially regulated in the livers of non-survivors.

Fig. S10. Linear regression analysis of hematological, clinical and histological parameters along survival variables.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This project was funded by the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) (IAA no. XRC-16002). We thank Dr. Eric Bernhard for his critical comments on the manuscript which helped us improve the writing. We are also grateful to Genus Biosystems for help with microarrays. We thank Gryphon Scientific for statistical support and Dr. Kevin Camphausen, Branch Chief, Radiation Oncology Branch, CCR, NCI for institutional help.

Footnotes

Editor’s note. The online version of this article (DOI: https://doi.org/10.1667/RADE-20-00123.1) contains supplementary information that is available to all authorized users.

REFERENCES

- 1.Coleman CN, Koerner JF. Biodosimetry: Medicine, science, and systems to support the medical decision-maker following a large scale nuclear or radiation incident. Radiat Prot Dosimetry 2016; 172:38–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Royba E, Repin M, Pampou S, Karan C, Brenner DJ, Garty G.RABiT-II-DCA: A fully-automated dicentric chromosome assay in multiwell plates. Radiat Res 2019; 192:311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Repin M, Pampou S, Garty G, Brenner DJ. RABiT-II: A fully-automated micronucleus assay system with shortened time to result. Radiat Res 2019; 191:232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Repin M, Pampou S, Brenner DJ, Garty G. The use of a centrifuge-free RABiT-II system for high-throughput micronucleus analysis. J Radiat Res 2020; 61:68–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jacob NK, Cooley JV, Yee TN, Jacob J, Alder H, Wickramasinghe P, et al. Identification of sensitive serum microRNA biomarkers for radiation biodosimetry. PLoS One 2013; 8:e57603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moroni M, Maeda D, Whitnall MH, Bonner WM, Redon CE. Evaluation of the gamma-H2AX assay for radiation biodosimetry in a swine model. Int J Mol Sci 2013; 14:14119–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lucas J, Dressman HK, Suchindran S, Nakamura M, Chao NJ, Himburg H, et al. A translatable predictor of human radiation exposure. PLoS One 2014; 9: e107897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ha CT, Li XH, Fu D, Moroni M, Fisher C, Arnott R, et al. Circulating interleukin-18 as a biomarker of total-body radiation exposure in mice, minipigs, and nonhuman primates (NHP). PLoS One 2014; 9:e109249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moroni M, Port M, Koch A, Gulani J, Meineke V, Abend M. Significance of bioindicators to predict survival in irradiated minipigs. Health Phys 2014; 106:727–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deperas-Kaminska M, Bajinskis A, Marczyk M, Polanska J, Wersall P, Lidbrink E, et al. Radiation-induced changes in levels of selected proteins in peripheral blood serum of breast cancer patients as a potential triage biodosimeter for large-scale radiological emergencies. Health Phys 2014; 107:555–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jones JW, Bennett A, Carter CL, Tudor G, Hankey KG, Farese AM, et al. Citrulline as a biomarker in the non-human primate total-and partial-body irradiation models: Correlation of circulating citrulline to acute and prolonged gastrointestinal injury. Health Phys 2015; 109:440–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bujold K, Hauer-Jensen M, Donini O, Rumage A, Hartman D, Hendrickson HP, et al. Citrulline as a biomarker for gastrointestinal-acute radiation syndrome: Species differences and experimental condition effects. Radiat Res 2016; 186:71–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Phillips M, Cataneo RN, Chaturvedi A, Kaplan PD, Libardoni M, Mundada M, et al. Breath biomarkers of whole-body gamma irradiation in the Göttingen minipig. Health Phys 2015; 108:538–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sproull M, Kramp T, Tandle A, Shankavaram U, Camphausen K. Serum amyloid A as a biomarker for radiation exposure. Radiat Res 2015; 184:14–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sproull M, Kramp T, Tandle A, Shankavaram U, Camphausen K. Multivariate analysis of radiation responsive proteins to predict radiation exposure in total-body irradiation and partial-body irradiation models. Radiat Res 2017; 187:251–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aryankalayil MJ, Chopra S, Levin J, Eke I, Makinde A, Das S, et al. Radiation-induced long noncoding RNAs in a mouse model after whole-body irradiation. Radiat Res 2018; 189:251–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aryankalayil MJ, Chopra S, Makinde A, Eke I, Levin J, Shankavaram U, et al. Microarray analysis of miRNA expression profiles following whole body irradiation in a mouse model. Biomarkers 2018; 23:689–703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jacobs AR, Guyon T, Headley V, Nair M, Ricketts W, Gray G, et al. Role of a high throughput biodosimetry test in treatment prioritization after a nuclear incident. Int J Radiat Biol 2020; 96:57–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blakely WF, Bolduc DL, Debad J, Sigal G, Port M, Abend M, et al. Use of proteomic and hematology biomarkers for prediction of hematopoietic acute radiation syndrome severity in baboon radiation models. Health Phys 2018; 115:29–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Singh VK, Newman VL, Romaine PL, Hauer-Jensen M, Pollard HB. Use of biomarkers for assessing radiation injury and efficacy of countermeasures. Expert Rev Mol Diagn 2016; 16:65–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Acute radiation syndrome. Washington, DC: Radiation Emergency Medical Management, Department of Health and Human Services; 2020. (https://bit.ly/3kgACo1) [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li Y, Shirley BC, Wilkins RC, Norton F, Knoll JHM, Rogan PK.Radiation dose estimation by completely automated interpretation of the dicentric chromosome assay. Radiat Prot Dosimetry 2019; 186:42–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Romero I, García O, Lamadrid AI, Gregoire E, Gonzalez JE,Morales W, et al. Assessment of simulated high-dose partial-body irradiation by PCC-R assay. J Radiat Res 2013; 54:863–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dorr AH, Abend M, Blakely WF, Bolduc DL, Boozer D, Costeira T, et al. Using clinical signs and symptoms for medical management of radiation casualties – 2015 NATO exercise. Radiat Res 2017; 187:273–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moroni M, Lombardini E, Salber R, Kazemzedeh M, Nagy V, Olsen C, et al. Hematological changes as prognostic indicators of survival: Similarities between Göttingen minipigs, humans, and other large animal models. PLoS One 2011; 6:e25210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Prasanna PGS, Blakely WF, Bertho J-M, Chute JP, Cohen EP, Goans RE, et al. Meeting report: Synopsis of partial-body radiation diagnostic biomarkers and medical management of radiation injury workshop. Radiat Res 2010; 173:245–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Valente M, Denis J, Grenier N, Arvers P, Foucher B, Desangles F, et al. Revisiting biomarkers of total-body and partial-body exposure in a baboon model of irradiation. PLoS One 2015; 10:e0132194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meadows SK, Dressman HK, Daher P, Himburg H, Russell JL, Doan P, et al. Diagnosis of partial body radiation exposure in mice using peripheral blood gene expression profiles. PLoS One 12; 5:e11535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Muller C, Schillert A, Rothemeier C, Tregouet D-A, Proust C, Binder H, et al. Removing batch effects from longitudinal gene expression – Quantile normalization plus ComBat as best approach for microarray transcriptome data. PLoS One 2016; 11:e0156594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim J, Jung Y. Radiation-induced liver disease: Current understanding and future perspectives. Exp Mol Med 2017; 49:e359–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Munoz-Schuffenegger P, Ng S, Dawson LA. Radiation-induced liver toxicity. Semin Radiat Oncol 2017; 27:350–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Benson R, Madan R, Kilambi R, Chander S. Radiation induced liver disease: A clinical update. J Egypt Natl Canc Inst 2016; 28:7–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bakshi M V, Azimzadeh O, Barjaktarovic Z, Kempf SJ, Merl-Pham J, Hauck SM, et al. Total body exposure to low-dose ionizing radiation induces long-term alterations to the liver proteome of neonatally exposed mice. J Proteome Res 2015; 14:366–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kjaergaard K, Weber B, Alstrup AKO, Petersen JBB, Hansen R,Hamilton-Dutoit SJ, et al. Hepatic regeneration following radiation-induced liver injury is associated with increased hepatobiliary secretion measured by PET in Göttingen minipigs. Sci Rep 2020; 10:10858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huang Z, Zhang M, Plec AA, Estill SJ, Cai L, Repa JJ, et al.ACSS2 promotes systemic fat storage and utilization through selective regulation of genes involved in lipid metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2018; 115:E9499–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.ALJohani AM, Syed DN, Ntambi JM. Insights into stearoyl-CoAdesaturase-1 regulation of systemic metabolism. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2017; 28:831–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wysocka MB, Pietraszek-Gremplewicz K, Nowak D. The role of apelin in cardiovascular diseases, obesity and cancer. Front Physiol 2018; 9:1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhong JC, Zhang ZZ, Wang W, McKinnie SMK, Vederas JC, Oudit GY. Targeting the apelin pathway as a novel therapeutic approach for cardiovascular diseases. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis 2017; 1863:1942–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kwon HB, Wang S, Helker CSM, Rasouli SJ, Maischein HM, Offermanns S, et al. In vivo modulation of endothelial polarization by Apelin receptor signalling. Nat Commun 2016; 7:11805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Boerma M, Kruse JJCM, Van Loenen MM, Klein HR, Bart CI, Zurcher C, et al. Increased deposition of von Willebrand factor in the rat heart after local ionizing irradiation. Strahlenther Onkol 2004; 180:109–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Boerma M, Zurcher C, Esveldt I, Schutte-Bart CI, Wondergem J. Histopathology of ventricles, coronary arteries and mast cell accumulation in transverse and longitudinal sections of the rat heart after irradiation. Oncol Rep 2004; 12:213–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kenchegowda D, Legesse B, Hritzo B, Olsen C, Aghdam S, KaurA, et al. Selective insulin-like growth factor resistance associated with heart hemorrhages and poor prognosis in a novel preclinical model of the hematopoietic acute radiation syndrome. Radiat Res 2018; 190:164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Legesse B, Kaur A, Kenchegowda D, Hritzo B, Culp WE, Moroni M. Neulasta regimen for the hematopoietic acute radiation syndrome: Effects beyond neutrophil recovery. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2019; 103:935–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gencer S, Van Der Vorst EPC, Aslani M, Weber C, Doring Y, Duchene J. Atypical chemokine receptors in cardiovascular disease. Thromb Haemost 2019; 119:534–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lin LY, Chang SC, O’Hearn J, Hui ST, Seldin M, Gupta P, et al. Systems genetics approach to biomarker discovery: GPNMB and heart failure in mice and humans. G3 (Bethesda) 2018; 8:3499–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Song C, Burgess S, Eicher JD, O’Donnell CJ, Johnson AD, Huang J, et al. Causal effect of plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1 on coronary heart disease. J Am Heart Assoc 2017; 6:e004918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Huang Y, Zhang W, Yu F, Gao F. The cellular and molecularmechanism of radiation-induced lung injury. Med Sci Monit 2017; 23:3446–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lesueur P, Escande A, Thariat J, Vauleon E, Monnet I, Cortot A, et al. Safety of combined PD-1 pathway inhibition and radiation therapy for non-small-cell lung cancer: A multicentric retrospective study from the GFPC. Cancer Med 2018; 7:5505–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Warr A, Affara N, Aken B, Beiki H, Bickhart DM, Billis K, et al. An improved pig reference genome sequence to enable pig genetics and genomics research. Gigascience 2020; 9:giaa051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.e!Ensembl. Pig (Sscrofa 11.1). Pig assembly and gene annotation. Ensembl genome browser 99; 2020. (https://bit.ly/3kgHj9D)

- 51.Zhao C, Lv Y, Duan Y, Li G, Zhang Z. Circulating non-codingRNAs and cardiovascular diseases. Adv Exp Med Biol 2020; 1229:357–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Viereck J, Thum T. Circulating noncoding RNAs as biomarkers of cardiovascular disease and injury. Circ Res 2017; 120:381–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. List of probes differentially expressed in a dose-dependent manner in heart samples of minipigs.

Table S2. List of probes differentially expressed in a survival-dependent manner in heart samples of minipigs.

Table S3. List of probes differentially expressed in the heart samples of non-survivors compared to both survivors and sham-irradiated animals.

Table S4. List of probes differentially expressed in a dose-dependent manner in liver samples of minipigs.

Table S5. List of probes differentially expressed in a survival-dependent manner in liver samples of minipigs.

Table S6. List of probes differentially expressed in liver samples of non-survivors compared to both survivors and sham-irradiated animals.

Table S7. List of probes differentially expressed in a dose-dependent manner in lung samples of minipigs.

Table S8. List of probes differentially expressed in a survival-dependent manner in lung samples of minipigs.

Table S9. List of probes differentially expressed in lung samples of non-survivors compared to both survivors and sham-irradiated animals.

Table S10. Pearson’s correlation coefficients computed between genes in survival signatures and histological grades for each organ.

Fig. S1. Ten most highly induced annotated probes in heart samples of non-survivors compared to both survivors and sham-irradiated animals.

Fig. S2. Ten most highly downregulated annotated probes in heart samples of non-survivors compared to both survivors and sham-irradiated animals.

Fig. S3. Ten most highly induced annotated probes in the liver samples of non-survivors compared to both survivors and sham-irradiated animals

Fig. S4. Ten most highly downregulated annotated probes in the liver samples of non-survivors compared to both survivors and sham-irradiated animals.

Fig. S5. Ten most highly induced annotated probes in the lung samples of non-survivors compared to both survivors and sham-irradiated animals.

Fig. S6. Ten most highly downregulated annotated probes in the lung samples of non-survivors compared to both survivors and sham-irradiated animals.

Fig. S7. Genes belonging to the superpathway of cholesterol biosynthesis downregulated in the liver samples of non-survivors compared to both survivors and sham-irradiated animals.

Fig. S8. Genes belonging to the fatty acid β-oxidation I pathway downregulated in the liver samples of non-survivors compared to both survivors and sham-irradiated animals.

Fig. S9. IPA-identified ‘‘diseases and biofunctions’’ and ‘‘toxicological functions’’ differentially regulated in the livers of non-survivors.

Fig. S10. Linear regression analysis of hematological, clinical and histological parameters along survival variables.