Abstract

Sedentary behavior increases the risk for multiple chronic diseases, early mortality, and accelerated cognitive decline in older adults. Interventions to reduce sedentary behavior among older adults are needed to improve health outcomes and reduce the burden on healthcare systems. We designed a randomized controlled trial that uses a self-affirmation manipulation and gain-framed health messaging to effectively reduce sedentary behavior in older adults. This message-based intervention lasts 6 weeks, recruiting 80 healthy but sedentary older adults from the community, between the ages of 60 and 95 years. Participants are randomly assigned to one of two groups: 1) an intervention group, which receives self-affirmation followed by gain-framed health messages daily or 2) a control group, which receives daily loss-framed health messages only. Objective physical activity engagement is measured by accelerometers. Accelerometers are deployed a week before, during, and the last week of intervention to examine potential changes in sedentary time and physical activity engagement. Participants undertake structural and functional (resting and task-based) MRI scans, neuropsychological tests, computerized behavioral measures, and neurobehavioral inventories at baseline and after the intervention. A 3-month follow-up assesses the long-term maintenance of any engendered behaviors from the intervention period. This study will assess the effectiveness of a novel behavioral intervention at reducing sedentarism in older adults and examine the neurobehavioral mechanisms underlying any such changes.

Keywords: sedentary behavior, randomized controlled trial, self-affirmation, positive messaging, affective psychology, fMRI

Introduction

Sedentarism is an epidemic among older adults, given that they spend an average of over 8 hours being sedentary daily [1,2]. Moreover, physical inactivity has increased sharply during the COVID-19 pandemic [3]. The potential health risks of leading a sedentary lifestyle are well established. Time spent sedentary (as measured by metabolic equivalents of task (MET) ≤ 1.5 [4]), is positively associated with increased risk for all-cause mortality, cardiovascular disease, cancer, and type 2 diabetes [5,6] and negatively associated with cognitive status in later life [7,8]. Moreover, physical inactivity costs healthcare systems approximately 53.8 billion international dollars each year [9]. Consequently, developing effective strategies to motivate reductions in sedentary time in older adults will significantly improve their health and well-being, as well as reduce the costs associated with healthcare.

Although improving awareness and conveying knowledge about exercise is important, these educational manipulations might be ineffective if the health information is perceived to be threatening which can evoke defensiveness [10]. Investigating how to make health information persuasive for behavioral change in older adults is important but underexplored. Self-affirmation manipulations are potential strategies that have been found to be effective in decreasing defensiveness and increasing receptiveness to potentially threatening health messages in younger and middle-aged adults [11,12]. Underpinned by a psychological process whereby one reflects on their core values, self-affirmation can help promote greater self-integrity and improve adaptations to threatening circumstances [13], leading to less defensiveness and greater action initiation in response to potentially threatening health messages [14]. Although a self-affirmation manipulation has not been examined in older adults, the underlying neural mechanism provides evidence of its potential effectiveness in older adults. Greater activation in brain regions that are critical for self-referential processing (e.g., ventromedial prefrontal cortex [VMPFC]) and positive valuation (e.g., ventral striatum [VS]) were associated with greater changes in sedentary behavior following a self-affirmation manipulated behavioral intervention for young and mid-aged adults [11,12]. These regions have previously been shown to be key nodes associated with self-affirmation [12,15–17]. Moreover, the medial prefrontal cortex is relatively spared during aging [18–20]. Thus, there is reason to posit that interventions that tap into self-referential processes would be effective in reducing time spent in sedentary in older adults.

There is growing evidence for a positivity effect in aging; this is an age-related shift favoring cognitive processing of positive over negative stimuli [21–23]. In older adults, positively-framed health messages (e.g., ‘Walking has important cardiovascular health benefits’) have previously been shown to be more effective at promoting walking compared to negatively-framed messages (e.g., ‘Not walking enough can lead to increased risk for cardiovascular disease’) [24]. In a follow-up analysis, those in the positive-framed group demonstrated greater memory for the intervention compared to the negative-framed control group[25]. Therefore, we predict that positive framing can add onto the effect of self-affirmation manipulation on behavior change; in other words, increasing the persuasiveness and bolstering the memory of health information both improve the intervention effect on behavior change. In this study, we combine daily positively framed health messages with a self-affirmation manipulation to take advantage of both of these techniques in an effort to enhance behavior change with regard to physical activity. Although positively-framed persuasive messages enhance physical activity in older adults, the underlying brain networks supporting this behavior are presently unknown. This study seeks to address this knowledge gap.

Study aims

The primary aim of the DASH study is to test the efficacy of self-affirmation plus gain-framed messaging to reduce sedentary time, as well as secondary outcomes related to sedentary behavior change. The primary outcome, sedentary time (i.e., time spent in sitting and lying), is quantified by objectively measuring average sedentary time across a period of at least 7 days, measured during multiple weeks across the intervention. The secondary outcomes include physical activity engagement, sleep, mood, cognitive functions, and structural and functional brain connectivity in self-referential and reward networks. This is a pilot study for a novel behavioral intervention with self-affirmation and positive messaging that will elucidate the individual differences and brain mechanisms underlying behavioral change. Therefore it represents a Stage I intervention within the context of the NIH Stage Model for Behavioral Intervention Development [26].

As an exploratory aim, we also investigate whether individual differences in baseline behavioral and brain metrics predict behavioral change and outcomes.

Methods

Study design

The DASH study is a stratified block randomized controlled trial. After reading and signing informed consent, recruited participants are randomized to either a self-affirmation plus gain-framed daily messaging group (intervention) or a loss-framed daily messaging only group (control) with a ratio of 1:1. Due to the constraints of in-person assessment during the COVID-19 pandemic, onsite participation in the MRI scans before and after the intervention is optional. Therefore, we stratify the randomization by MRI participation (yes/no) to ensure the same distribution of MRI and behavioral-only participants across the two groups. Loss-framed messages were chosen as a control group (over neutral messaging) as they provide the same contextual information as the gain-framed messages (only framed in a negative way), compared to neutral messages which contain factual information (see Figure 3B for an example of gain- versus loss-framed messages). All participants are informed about the randomization but blinded to the group assignment. Participants are informed that the study aims to examine whether a 6-week program promotes brain health and behavior. However, it is not possible to blind experimenters, as they view the intervention related materials and give instructions during the assessments. The randomization scheme is prepared by the Harvard Catalyst Biostatistical Group using a stratified permuted block method with random blocks. All experimenters are blinded to the block size. Sealed envelopes are provided to the investigator and stored at the designated site. This trial is registered on clinicaltrials.gov with an identifier NCT04315363. This study received ethical approval from Northeastern University Institutional Review Board (IRB).

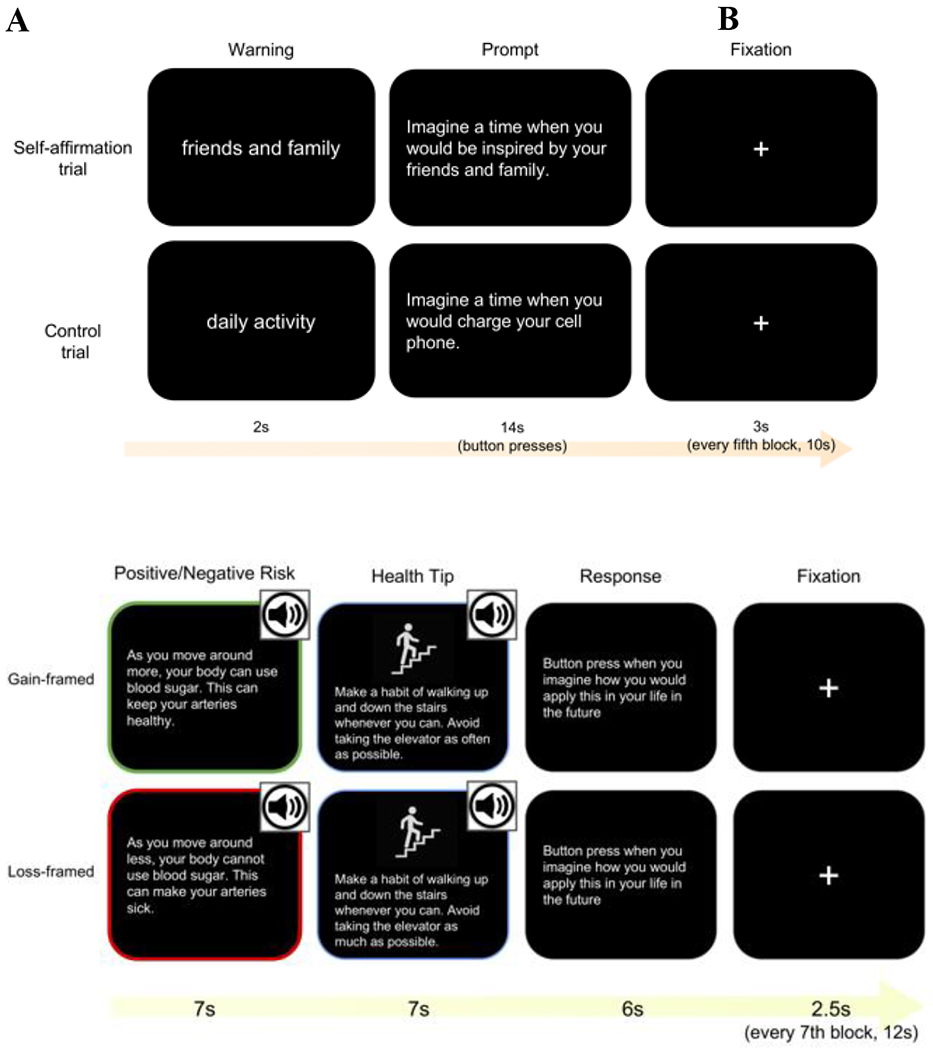

Figure 3.

Graphic representation of the self-affirmation manipulation (A) and health message (B) fMRI tasks.

Participants

We plan to recruit 80 sedentary older adults for this study between the ages of 60 and 95 years that engage in less than 150 minutes of moderate-to-vigorous-intensity aerobic exercise per week and more than 8 hours of sitting time per day, as assessed with a self-report during an initial phone screening. Full inclusion and exclusion criteria are described in Table 1. We plan to recruit a diverse population that is balanced across race, sex, and socioeconomic status. The study is advertised via promotional flyers in and around the Boston area and local senior citizen centers as well as online advertisements through websites such as Craigslist and Facebook. Potential participants are screened by phone. The Telephone Interview of Cognitive Status (TICS) is used initially to screen cognitive function. Sitting Time questionnaire [27] and International Physical Activity Questionnaire [28] are used for screening physical activity engagement and sedentary behavior. Potential participants are asked a series of questions relating to the inclusion/exclusion criteria and past medical history. MRI participants are also screened for additional criteria related to MRI safety and potential research confounds. An upper weight limit is set based on the capacity of the onsite scanner. Individuals with insulin dependence and psychotropic medications are excluded from the MRI participation to avoid their confounding effects on brain activation.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| • Men and women of all ethnicities/races and socioeconomic status, 60-95 years • Normal or corrected-to-normal vision based on the minimal 20/20 standard in order to complete the cognitive tasks (below 20/20 vision) • Body Mass Index (BMI) over 20 and less than 40 • Able to speak, read, and write English fluently • Ambulatory without significant pain or the assistance of walking devices • No diagnosis of a neurological disease • Passing the Telephone Interview of Cognitive Status (TICS) as cognitively normal (i.e., score >= 26) • No contraindications to MRI imaging* • Under 150 minutes per week of moderate and vigorous intensity physical activity • Sitting time more than 8 hours per day • Regular access to a computer or smartphone with internet • Weight under 275 pounds* • Reliable transportation to the Northeastern University campus for 2 visits* • No involvement in conflicting research studies currently or recently |

• Changes in treatment (e.g., medication) with current diagnosis of a DSM-V1 Axis I or II disorder in the past 6 months • History of major psychiatric illness including schizophrenia, bipolar disorder (not including major depression and anxiety) • Current treatment for cancer – except non-melanoma skin • Neurological condition (e.g., multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, cognitive impairment, stroke, or traumatic brain injury). • Type I Diabetes • Type II Diabetes if unstable or controlled by insulin* • History of alcohol or substance abuse in the last 5 years • Current treatment for congestive heart failure, angina, uncontrolled arrhythmia, or other cardiovascular condition • A blood clot in the legs in the last 2 years • Myocardial infarction, coronary artery bypass grafting, angioplasty, or other cardiac event in the past year • Regular use of an assisted walking device • Claustrophobia* • Use of psychotropic medications* |

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth edition;

Criteria with * are only for screening MRI participants

Intervention

Study timeline

An illustration of the study timeline can be seen in Figure 1. Each participant undergoes a baseline session (T1) one week before the beginning of the intervention. Informed consent is obtained at baseline, during which participants specify whether they opt to participate in the MRI scans or not. Randomization takes place after obtaining informed consent (T1) and participants are assigned into either the intervention or control group. During the T1 visit, the participants also undergo baseline testing including neuropsychological tests and neurobehavioral inventories, which take about 3 hours in total. In order not to prime exercise for the baseline physical activity level, inventories that are related to exercise and self-perception are not administered during T1 visit. At baseline, participants wear an activPAL monitor on their thigh to assess postural aspects of sedentary behavior including time spent sitting and lying and a wrist-worn accelerometer on their non-dominant hand to assess physical activity (see physical activity monitoring). Both monitors are worn for a week. One week later (T2), physical assessments and the remaining neurobehavioral inventories related to exercise and self-perception will be administrated, which takes about 1.5 hours.

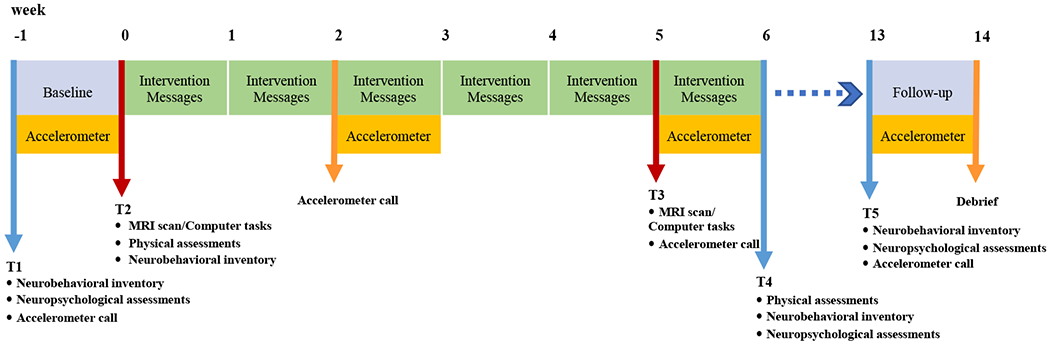

Figure 1.

Study timeline. Baseline assessments (neurobehavioral inventories, neuropsychological assessments, and MRI) are performed prior to 6-weeks of intervention. Accelerometers collect sedentary behavior and physical activity data for 1-week periods, 4 times across the study (pre, during, immediately post and 3-month follow up).

MRI participants undergo pre-intervention MRI, which takes about 1.5 hours and marks the onset of the intervention, while behavioral-only participants complete the same fMRI tasks remotely. The intervention lasts 6 weeks, during which participants receive daily intervention messages via email or smartphone. Participants are fitted with the accelerometers again for a one-week mid-intervention period (week 3). The post-intervention visit (T3) is scheduled at the beginning of the last intervention week (week 5), during which MRI participants perform post-intervention MRI scanning and behavioral-only participants perform the corresponding tasks. After the last intervention week (T4), participants repeat the neurobehavioral inventories, neuropsychological tests and physical assessments. A three-month follow-up visit (T5) is performed at week 14, in which participants complete neuropsychological assessments and neurobehavioral inventories for a third time, and a final week of accelerometer data is collected. All sessions except MRI scanning are administrated remotely through online surveys and computer tasks. Three accelerometer calls are administered by two research assistants, for the purpose of giving instructions and answering questions about accelerometers. The estimated overall participation time is 16 hours, which may vary across individuals. To minimize attrition, each assessment session (i.e., T1, T2, T3, T4, T5) is self-paced and has been divided into smaller visits, each of which lasts no longer than 2 hours. During each visit, participants take breaks every 20 minutes to minimize the risk of fatigue.

Daily messaging

The 6-week intervention consists of daily messages via email using the online software oTree, an open-source platform for implementing messaging survey, which allows for accessibility via desktop or smartphone [29]. Unique links are assigned each participant at enrollment.

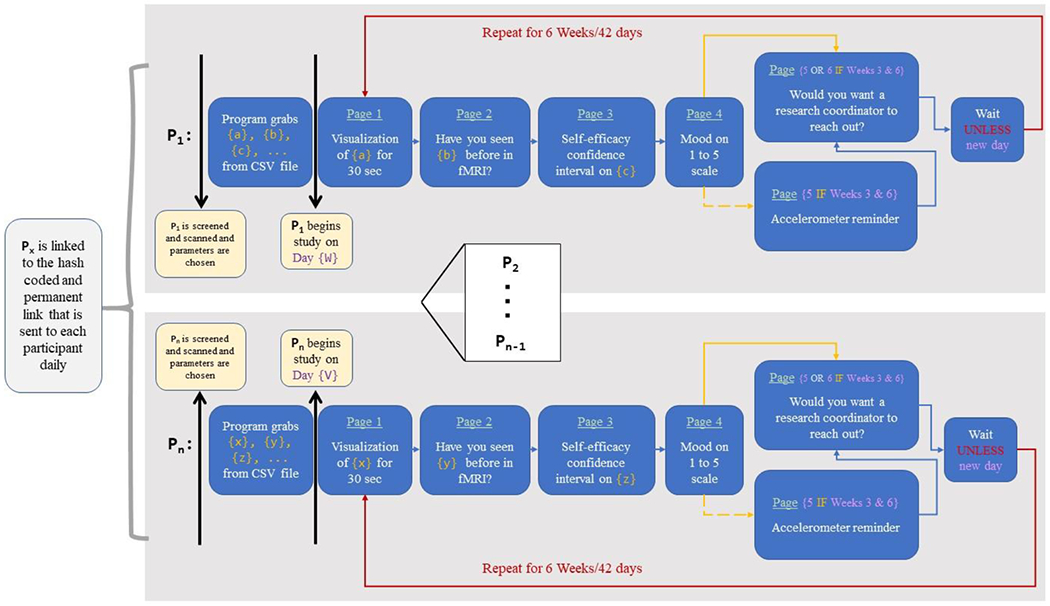

Each day, all participants receive daily messages. Participants will be asked to rank 8 core values based on personal importance (i.e., politics, religion, family and friends, creativity, money, independence, humor, and spontaneity) during baseline assessment (T1). Participants in the intervention group receive daily prompts to reflect on their highest-ranked core value vividly (e.g., think of a time when you are inspired by your family) followed by a gain-framed message about being physically active (e.g., walking is good for your health). The control group will receive daily prompts to reflect on an everyday activity (e.g., think of a time when you charge your phone) as well as the same content of daily messages but in a loss-framed way (e.g., being sedentary is harmful to your health). These daily self-affirmation and health messages will consist of a combination of the same messages used in the fMRI tasks and novel messages. The Walk-BEST Workbook, a guideline to improve walking safely and effectively (https://physiobiometrics.com/), has been used as a reference source of health messages. At the same time, participants will be tested on their memory for health messages from the fMRI task. The participant will then rate their mood and confidence in implementing the health tips, the goal of which is to examine the changing of well-being and self-efficacy of physical activity throughout the intervention. During weeks 3 and 6, they also receive daily reminders to continue wearing their accelerometers. This daily message survey setup is displayed in Figure 2. The researcher’s contact information is displayed on each survey page to enhance compliance. To monitor the participation adherence, participants’ responses are tracked and those that do not complete the survey by a specified time of day are contacted the following day by research assistants to prevent technical failures. The time spent on the daily message intervention including the healthy messages and survey questions is recorded by the daily message system, no response to the survey questions or responses under 3 seconds to the self-affirmation probe are considered as non-compliance.

Figure 2.

Messaging system setup and logic. Each participant (represented by Px, where x designates the participant number) receives their unique link. In that link, they follow a series of pages each day that contains their unique questions and parameters based upon the inputted comma-separated values (CSV) file. The system does not initiate until the participant begins on their first day and then repeats for 42 days (6 weeks) for the duration of the daily messaging intervention. The process occurs synonymously for all other participants. Links that are not activated simply remain idle until a participant is assigned that link

Measurements and materials

Physical activity monitoring

Time spent sedentary as the primary outcome will be measured with an activPAL inclinometer (activPAL, PAL Technologies, Glasgow, UK). Sleep quality, duration, and physical activity engagement will be measured as secondary outcomes using an GT9X Link accelerometer (ActiGraph LLC, Pensacola, FL). Participants will be wearing two motion sensors at week 0 (between T1 and T2), week 3 (mid-intervention), week 6 (between T3 and T4) and week 14 (T5), 24 hours/day for seven continuous days (see Figure 1). To measure sedentary time, an activPAL monitor is attached on the mid-anterior surface of the right thigh. This device is used to measure postural aspects of sedentary behavior, including time spent lying and sitting, standing, and the number of sit-to-stand transitions. An accelerometer will be worn on the non-dominant wrist to improve compliance and allow for the assessment of sleep characteristics. Total time spent in physical activity, as well as time spent in light, moderate and vigorous intensities, are measured. Sitting and standing time as measured with an activPAL correlate highly with the direct observation (the gold standard) in classifying sitting and standing in older adults (rs ≥ .95) [30]. ActiGraph accelerometers can reliably estimate daily physical activity based on a minimum of 4 valid days of wear (i.e., 70-80%) [31] and physical activity energy expenditure as assessed against a gold standard (i.e., doubly labeled water; rs =[0.34-0.64]) [32]. ActivPAL can reliably estimate sedentary time based on a minimum of 5 days of wear [33]. The use of both devices affords accurate and sensitive measures of both sedentary behavior and physical activity. Participants are also asked to complete a sleep log and record times when they remove and replace the devices during each day (e.g., before and after taking shower). Sleep parameters will be captured through ActiGraph accelerometers.

To ensure compliance, there is a conference call prior to each of the three accelerometer weeks, during which the participants will be instructed how to wear the devices correctly. Tutorials for wearing devices are sent out prior to the meeting. During these weeks, participants also receive accelerometer reminders each day at the end of the health message intervention survey and they are instructed to respond to question of whether they are wearing the devices on that day (see Figure 2). A research assistant will reach out if they respond no or do not respond, to prevent any technical issue.

Neurobehavioral inventory

A battery of neurobehavioral inventories will be administered at baseline (T1), post-intervention (T4) and follow-up (T5)), listed in Table 2. We have included inventories on sleep quality, depression and anxiety as our secondary outcomes to detect change after the intervention. We also aim to phenotype individual differences in personality traits, physical status, socioeconomic status, general and exercise-related motivation and self-efficacy, all considered as covariates, which potentially predict individual differences in intervention effect of participants. All inventories will be administrated through the RedCap survey interface remotely. To enhance the compliance, researchers stay online while participants fill out the questionnaires and answer any questions they may have. The researchers are muted, and video is disabled to minimize experimenter effect. Each measure is described in Table 2.

Table 2.

Neurobehavioral inventory

| Name | Description |

|---|---|

| Barriers Self-Efficacy Scale[34] *, † | A 13-item questionnaire that assesses how confident people are to exercise when facing challenges (e.g., bad weather) |

| Pittsburg Sleep Quality Index[35] *, † | A 10-item questionnaire that measures sleep quality |

| Temporal Experience of Pleasure Scale[36] | An 18-item questionnaire that assesses people’s ability to experience pleasure |

| Apathy Evaluation Scale[37] * | An 18-item questionnaire that assesses the degree of motivation lacking caused by disease |

| Modified Fatigue Impact Scale[38] *, † | A 21-item questionnaire that asks about how fatigue affects daily life |

| Exercise Self Efficacy Scale[39] *, † | A 10-item questionnaire that assesses self-perception about capability to exercise |

| Short-form International Physical Activity Questionnaire[28] *, † | A 7-item questionnaire that asks about current amount of physical activity |

| Growth Mindset Scale[40] Modified for Fitness *, † |

A 3-item questionnaire that assesses belief that fitness is fixed or can be changed |

| Exercise Motivation Inventory[41] † | A 51-item questionnaire that assesses motivation to exercise |

| Grit Scale Survey[42] † | An 8-item questionnaire that measures the sustained effort and passion to pursue a goal |

| Life Orientation Test Revised[43] * | A 10-item questionnaire that measures optimism |

| Purpose in Life Test [44] | A 10-item questionnaire that measures meaning and purpose in life |

| Elderly Motivation Scale[45] *, † | An 84-item questionnaire that assess intrinsic and extrinsic motivation of older adults |

| Neuroticism Extraversion Openness Five Factor Inventory[46] | A 60-item questionnaire that examine personality from Openness, Extraversion, Neuroticism, Agreeableness and Conscientiousness |

| UCLA Loneliness Scale[47] * | A 14-item questionnaire that measures level of loneliness |

| Assets and Debt[48] | A 10-item questionnaire that measures socioeconomic situation |

| Self-Regulation for Exercise[49] *, † | A 16-item questionnaire that measures sense of control for exercising |

| Mobile Device Proficiency Questionnaire - Short form[50] | A 16-item questionnaire that assesses the proficiency of using mobile device |

| Gratitude Questionnaire-6[51] † | A 7-item questionnaire that assesses tendency to experience gratitude |

| Geriatric Anxiety Inventory[52] * | A 20-item questionnaire for anxiety screening |

| Geriatric Depression Scale[53] * | A 15-item questionnaire for depression screening |

| Modified Differential Emotions Scale[54]* | A 20-item questionnaire that assesses mood and feelings |

| Future Time Perspective[55] | A task asking participant to generate autobiographical details of one’s future |

| Visual Analogue Pain Scale [56] | A single analogue scale stretching from “no pain” to “pain as bad as it could be” |

| Edinburgh Handedness Inventory – Short Form [57] | A 4-item questionnaire for preference in hand using |

Measurements with * are re-tested after intervention, and measurement without * are only tested at baseline.

Measurements with † are tested after the baseline accelerometer week, and measurements without † are tested before the baseline accelerometer week.

Physical assessments

All physical assessments will be administrated remotely. Blood pressure and resting heart rate will be measured using Omron Bronze blood pressure monitor series 3 (https://omronhealthcare.com/products/3-series-upper-arm-blood-pressure-monitor-bp7100/). Age, sex, body mass index, resting heart rate, and self-reported physical activity levels are used to calculate an estimated cardiorespiratory fitness, which has been validated in previous studies [58,59]. Participants will be instructed to perform 6 minute walk, chair stand and arm curl, and 8-Foot Up and Go from the Senior Fitness Test [60], as well as gait speed and balance test from the Short Physical Performance Battery [61] remotely through video conferences, to assess physical function before and after the intervention. Each participant receives a package containing a blood-pressure cuff, yarn measured for each walking course, tape and a phone stand. Prior to the physical assessment session, participants are instructed through a conference call to prepare by: (1) identifying the correct length of the yarns based on the standard distance for 6-minute walk and 8-Foot Up and Go test, and placing them in position at home using tape, and (2) finding the best angle to place the camera (phone or laptop) to make sure it covers the whole course. Researchers observe participants’ movements during a video call and use stopwatches to time the tests. To prevent accidents, participants are asked to remove any obstacles in the room, and place chairs near the course in case they need rest. As an emergency protocol, researchers prepare the following information and make sure it is easily accessible during the session: each participant’s health history without ID, non-emergency police number that corresponds with the participant’s address, and the cross-streets and address of the participant’s location. In addition, participants will be asked if they have another individual who could be present in the home for testing in the event of an emergency. If they have someone who can be present, the participant will be asked to provide that individual’s name and have them located within earshot during the test.

Neuropsychological measures

A battery of standard neuropsychological assessments and computerized behavioral cognitive paradigms will be performed at T1 (baseline), T3 (post 6-week intervention) and T5 (3-months follow-up). Global cognitive function will be assessed using the Montreal Cognitive Assessment-Blind (MoCA-B), a modified MoCA test which can be administrated through phone [62]. Verbal fluency through Semantic Category Verbal Fluency test, Reasoning through Number Series Completion task, and episodic memory through Rey Auditory-Verbal Learning test are measured via telephone based on the Brief Test of Adult Cognition by Telephone (BTACT) [61]. With consent of participants, audio of MoCA and BTACT tests are recorded over the phone. Executive function through the Trail Making Test part B, processing speed via the Trail Making Test part A, Digit Symbol Matching test and Simple Reaction Time task, sustained attention and motor speed via Continuous Performance Task, and working memory via digit span forwards and backwards are measured through TestMyBrain (www.testmybrain.org), an online tool for remote neuropsychological tests [62]. Researchers stay online while participants perform computerized tasks to answer any questions and address any technical issues.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

To assess whether reductions in sedentary behavior results in changes to brain structure and function, participants will undergo structural and functional MRI at the end of week 0 (T2) and 6-weeks, post-intervention (T3). Data acquisition will be undertaken using a 3 Tesla Siemens PRISMA scanner and 64-channel coil. Sequences collected include high-resolution three-dimensional (3D) Magnetization-Prepared Rapid Acquisition with Gradient Echo (MPRAGE) T1-weighted (T1w) and T2-weighted (T2w) sequences (Sagittal, 0.8 mm isotropic resolution, TE/TI/TR = 2.31/1000/2500 ms, Field of View (FOV) 256 mm, 208 slices), a high resolution multi-shell Diffusion-Weighted imaging (DWI) white matter sequence (Resolution: 2.5 × 2.5 × 2.5 mm, TE/TR = 95.6/2800 ms, Multiband factor = 4, b-values of 1500, 3000 s/mm2, 64 gradient directions), a resting state Echo Planar Imaging (EPI) scan (Resolution: 2 × 2 × 2 mm, TE/TR = 37/800 ms, Multiband factor = 8 (CMRR EPI sequence [60–63]), 72 slices, 600 measurements) and three task-evoked EPI scans (Resolution: 2 × 2 × 2 mm, TE/TR = 37/800 ms, Multiband factor = 8, 72 slices, 413, 534 or 627 measurements). Data will undergo quality control assessments for sequence accuracy (naming standards, correct number of volumes per sequence and correct sequence parameters). Data are then converted to NIfTI format and structured per the Brain Imaging Data Structure (BIDS). A visual inspection of the data is performed and a quantitative quality control using MRIQC[65] will be done to calculate signal-to-noise measurements for each sequence. Data will then be preprocessed using fmriprep, which includes the basic preprocessing steps such as skull stripping, registration, normalization, noise component extraction, and segmentation [66]. Participants will perform three behavioral tasks during the scanning session. Stimuli will be displayed on a Windows system computer for all tasks. Participants will use a gamepad for responding to the task in the scanner. The behavioral tasks are:

Self-affirmation task:

During the initial T1 assessments, participants are asked to rank eight core values in terms of personal importance (i.e., politics, religion, family and friends, creativity, money, independence, humor, and spontaneity). The task follows a block design containing a self-affirmation manipulation. There will be 21 value trials, during which the intervention group will be asked to reflect on their highest-ranked core value; the control group on the other hand will be asked to reflect on their lowest-ranked core value. As a within-subjects control and interleaved throughout the blocks, participants in both groups will also be asked to reflect on value-neutral statements of everyday activity for 21 control trials. During each trial, a cue (value or everyday activity) is displayed for 2s, and then the prompt is displayed for 14s (e.g., imagine a time when you are inspired by your friends and family; imagine a time when you charge your phone, for value trials and everyday activity trials respectively), during which participants are asked to reflect and press the button each time when they think of an example of the prompts. The reaction time and the number of button presses for each trial are recorded. For a more detailed description of this task see [12]. For examples of the self-affirmation manipulation see Figure 3A. This task is programmed in PsychoPy software [67,68]. The same task is administrated through Pavlovia (https://pavlovia.org/) for behavioral-only participants.

Health messages task:

This task also follows a block design where participants will receive either a gain (intervention group)- or loss (control group)-framed health message followed by a health tip. The informational content of the health tip is the same for both groups. As a within-subjects control block, a factual everyday activity message followed by a control tip will be interleaved throughout the blocks. There are 21 health messages and 21 factual everyday activity control messages for both groups. During each trial, participants view the message for 7s and tip for 13s and then press the button when they have imagined how they can apply the tip in their life. They have 6s to respond. The reaction time of the button press is recorded for each trial. For examples of the health messages and health tips see Figure 3B. This task is programmed in PsychoPy software [67,68]. The same task is administrated through Pavlovia (https://pavlovia.org/) for behavioral-only participants.

Monetary incentive delay (MID) task:

This task follows the Research Domain Criteria (RDoC; https://www.nimh.nih.gov/research/research-funded-by-nimh/rdoc/index.shtml) construct of reward Anticipation and Responsiveness. For each trial a star in the center of the screen will appear for ~.227 seconds preceded by either a cue (i.e., “+”, “−” or “0”). Then they are asked to press the button as soon as possible once they see a star appeared on the screen (considered a “hit”, as opposed to a “miss”). In the “+” condition, a hit will gain them points and a miss will not change their score. In the “−” a hit means their score will not change but a miss will lose them points. In the “0” there is no change to their tally, regardless of their response. The latency of the star appearance will be adjusted throughout the task to achieve a hit rate of ~67%. The reaction time and accuracy of each trial are recorded. This task is programmed in Psychotoolbox-3 [69]. We use this task to localize brain regions related to reward valuation for individual participants. It is not administered for behavioral-only participants.

Data management

All research data are de-identified and only the research coordinator has access to identifiable information that is stored in a secure location. Data are stored electronically on password-protected servers behind university-protected firewalls. Data are stored in one of three ways; (1) MRI data (including tasks) and physical activity monitoring data are extracted from their respective software packages and uploaded directly to a secure data storage environment at a high-performance computing facility (Discovery cluster at Northeastern University). (2) All pen and paper inventories and neuropsychological assessments are scored and uploaded to REDCap[70]. Computerized neurobehavioral inventories are collected directly in REDCap and computerized neuropsychological assessments are uploaded to REDCap. (3) The oTree library is used to distribute the daily intervention messages and collect survey data. This system runs on a Heroku server, a cloud-based system that sends and receives hash-encrypted links. Collected anonymized data are stored on the messaging site behind an administrative login on the Heroku server.

Analysis plan

Power calculations were performed to statistically determine the target sample size of N=80 for this pilot study. The power is calculated in R based on a two-sample T-test model with our primary outcome, the percent of daily sedentary time assessed using an activPAL. We expected a similar baseline sedentary sample to the study by Falk et al., where participants were sedentary an average of 50.6% ± 14.0% of their time [11]. Our proposed sample size of 80 participants (40 per group) will allow us to detect a minimum detectable difference of 10.0% between the two groups (i.e., the group difference in averaged sedentary time/total valid awake time) at week 6 post intervention with a common standard deviation of 14.0% with 80% power and a two-sided alpha of 0.05, with 20% drop-out rate accounted. We expect that the ratio of sedentary time/total valid awake time in the self-affirmation + positive framing group will be 10.0% less than the control negative framing group, based on our power analysis.

After compiling all data across the 3 different data servers, data will be checked for completeness and correctness using frequency distributions (for missing data and out-of-range values). Group differences at baseline are examined for variables including demographic factors (i.e., age, sex, educational level, socioeconomic status, race/ethnicity), baseline sedentary time, self-report sitting time, and estimated fitness, in order to detect potential confounding factors. For the primary hypothesis that self-affirmation + gain-framed messages decrease sedentary time more so than loss-framed messages all outcome measures about sedentary behavior are first quantified using available software. Changes in sedentary behavior (% daily sitting and lying time, minutes/per day in physical activity, count of steps) over time (3 time points) are analyzed using linear mixed effect models to account for the correlated data and likely heterogeneous variability. Curvilinear changes across 3 time points are also considered and are analyzed by including quadratic effect terms in the models. These models will include a random intercept and slope to account for subject-specific changes as well as a group (2) x time (3) interaction fixed effect. This allows for modelling of the effect of our intervention as a function of both group and time as well as accounting for potential confounding covariates. All model assumptions will be tested both visually and formally and associations between covariates will be assessed to protect against multicollinearity. All valid data are included in the model initially, followed by per protocol analyses, in which the cases with (1) less than 4 valid days of ActiGraph or (2) less than 5 valid days of activPAL or (3) more than 2 days with non-compliance of daily message intervention are excluded in the analysis. For the final dataset, the multiple imputation by chained equations (MICE) will be used for imputing missing values with 10 imputations.

Analyses on the resting state and task-based fMRI analyses are considered secondary. Briefly they will be modelled using the general linear model approach. First-level analyses will include all necessary nuisance regressors to minimize the influence of motion artifacts, spatial smoothing and high pass filtering, as well as physiological aliasing for low frequency fluctuations in resting state data. To answer questions about the efficacy of the intervention and prediction of behavioral change, both a-priori ROI seed-based analyses of functional connectivity will be performed as well as data-driven whole brain multi-voxel pattern analyses, modularity analyses and graph theory per several previous publications using data-driven approaches to predict clinical outcomes [71–73]. Main contrasts will focus on group differences (SA + positive framing vs negative framing only). Besides the primary outcomes, adherence and drop-outs are also included in the prediction model as outcome variables, with psychosocial variables as predictors, to examine which individual characteristics affect adherence to the current intervention. Robust-prediction models of MRI data and psychosocial variables will be generated using cross-validation methods to improve generalizability of the results [74].

Discussion

Efficacious behavioral interventions to decrease sedentary behaviors in older adults will have a critical impact on disease prevention, quality of life and public health. The COVID-19 pandemic has further heightened the urgency to reduce sedentary due to increased inactiveness among older adults [3]. We have designed a 6-week pilot randomized controlled trial to examine the efficacy of daily self-affirmation and gain-framed messaging in decreasing sedentary time. Through increasing receptivity to health messages via reinforcement of self-referential and positive valuation networks, we hypothesize there will be a significant reduction in sedentary time in the intervention group, compared to the control group (who receives loss-framed messages only). Following the intervention, we will test the extent to which participants maintain any engendered physical activity behaviors at the 3-month follow-up. We will examine whether the intervention produces improvements in cognitive function (e.g., executive function, processing speed) and enhanced functional and structural brain connectivity, related to engendered behavioral changes in the intervention group. In an exploratory aim, we expect that psychosocial and cognitive variables, and MRI metrics of brain structure and function at baseline will predict behavioral change in the intervention group.

There are several notable limitations to this study, yet we have taken a number of measures to minimize their impact. First, this is a pilot study with only a moderate sample size. Nevertheless, a power analysis of our primary outcome measure was performed to ensure that a sample size of 80 is sufficient to detect a true effect with 80% power. Additionally, interpretations of individual component contributions of our intervention are to be taken with caution given we cannot disentangle the effect of gain-framed messaging from self-affirmation. Regarding the inclinometer and accelerometer-based assessments, we are limited to the collection of data for 3 periods of 1 week (i.e., not assessing accelerometry throughout the entire 6-week intervention). However, the use of two state-of-the-art devices allows us to accurately capture both sedentary time and physical activity, to get a more comprehensive picture of physical activity and sedentary behavior of participants. Furthermore, continued monitoring of daily engagement with the intervention is performed and a researcher will make contact with study participants to maximize compliance. Third, this study will recruit participants who are cognitively normal, ambulatory, MRI compatible, and have access to a smartphone or a computer. This sample selectivity should be considered when we interpret the results.

In summary, this 6-week pilot randomized control trial examines the effect of a novel behavioral intervention on reducing sedentary time in older adults, by combining self-affirmation and gain-framed messages. The results will provide preliminary evidence for the efficacy of self-affirmation manipulation prior to health messaging to decrease sedentary behaviors in older adults and at the same time, provide mechanistic insight into the engenderment of behavioral change in older adults. Such insight can be used to optimize future behavioral intervention development.

Acknowledgments

This work is conducted with support from an NIH/NIA Roybal grant # P30 AG048785, Harvard Catalyst Biostatistics Consulting Service, and Northeastern University. The Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Centre (National Centre for Research Resources and the National Centre for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCRR and the NCATS NIH, UL1 TR001102)) and financial contributions from Harvard University and its affiliated academic healthcare centers.

References

- [1].Harvey JA, Chastin SFM, Skelton DA, Prevalence of Sedentary Behavior in Older Adults: A Systematic Review, International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 10 (2013) 6645–6661. 10.3390/ijerph10126645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Harvey JA, Chastin SFM, Skelton DA, How Sedentary Are Older People? A Systematic Review of the Amount of Sedentary Behavior, Journal of Aging and Physical Activity. 23 (2015) 471–487. 10.1123/japa.2014-0164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Peçanha T, Goessler KF, Roschel H, Gualano B, Social isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic can increase physical inactivity and the global burden of cardiovascular disease, American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 318 (2020) H1441–H1446. 10.1152/ajpheart.00268.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Tremblay MS, Aubert S, Barnes JD, Saunders TJ, Carson V, Latimer-Cheung AE, Chastin SFM, Altenburg TM, Chinapaw MJM, Altenburg TM, Aminian S, Arundell L, Atkin AJ, Aubert S, Barnes J, Barone Gibbs B, Bassett-Gunter R, Belanger K, Biddle S, Biswas A, Carson V, Chaput J-P, Chastin S, Chau J, ChinAPaw M, Colley R, Coppinger T, Craven C, Cristi-Montero C, de Assis Teles Santos D, del Pozo Cruz B, del Pozo-Cruz J, Dempsey P, do Carmo Santos Gonçalves RF, Ekelund U, Ellingson L, Ezeugwu V, Fitzsimons C, Florez-Pregonero A, Friel CP, Fröberg A, Giangregorio L, Godin L, Gunnell K, Halloway S, Hinkley T, Hnatiuk J, Husu P, Kadir M, Karagounis LG, Koster A, Lakerveld J, Lamb M, Larouche R, Latimer-Cheung A, LeBlanc AG, Lee E-Y, Lee P, Lopes L, Manns T, Manyanga T, Martin Ginis K, McVeigh J, Meneguci J, Moreira C, Murtagh E, Patterson F, Rodrigues Pereira da Silva D, Pesola AJ, Peterson N, Pettitt C, Pilutti L, Pinto Pereira S, Poitras V, Prince S, Rathod A, Rivière F, Rosenkranz S, Routhier F, Santos R, Saunders T, Smith B, Theou O, Tomasone J, Tremblay M, Tucker P, Umstattd Meyer R, van der Ploeg H, Villalobos T, Viren T, Wallmann-Sperlich B, Wijndaele K, Wondergem R, on behalf of SBRN Terminology Consensus Project Participants, Sedentary Behavior Research Network (SBRN) – Terminology Consensus Project process and outcome, Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 14 (2017) 75. 10.1186/s12966-017-0525-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Biswas A, Oh PI, Faulkner GE, Bajaj RR, Silver MA, Mitchell MS, Alter DA, Sedentary Time and Its Association With Risk for Disease Incidence, Mortality, and Hospitalization in Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis, Ann Intern Med. 162 (2015) 123. 10.7326/M14-1651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Ekelund U, Steene-Johannessen J, Brown WJ, Fagerland MW, Owen N, Powell KE, Bauman A, Lee I-M, Does physical activity attenuate, or even eliminate, the detrimental association of sitting time with mortality? A harmonised meta-analysis of data from more than 1 million men and women, The Lancet. 388 (2016) 1302–1310. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30370-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Falck RS, Davis JC, Liu-Ambrose T, What is the association between sedentary behaviour and cognitive function? A systematic review, Br J Sports Med. 51 (2017) 800–811. 10.1136/bjsports-2015-095551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Rosenberg DE, Bellettiere J, Gardiner PA, Villarreal VN, Crist K, Kerr J, Independent Associations Between Sedentary Behaviors and Mental, Cognitive, Physical, and Functional Health Among Older Adults in Retirement Communities, J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 71 (2016) 78–83. 10.1093/gerona/glv103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Ding D, Lawson KD, Kolbe-Alexander TL, Finkelstein EA, Katzmarzyk PT, van Mechelen W, Pratt M, The economic burden of physical inactivity: a global analysis of major non-communicable diseases, The Lancet. 388 (2016) 1311–1324. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30383-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Good A, Abraham C, Measuring defensive responses to threatening messages: a meta-analysis of measures, Health Psychology Review. 1 (2007) 208–229. 10.1080/17437190802280889. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Falk EB, O’Donnell MB, Cascio CN, Tinney F, Kang Y, Lieberman MD, Taylor SE, An L, Resnicow K, Strecher VJ, Self-affirmation alters the brain’s response to health messages and subsequent behavior change, PNAS. 112 (2015) 1977–1982. 10.1073/pnas.1500247112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Cascio CN, O’Donnell MB, Tinney FJ, Lieberman MD, Taylor SE, Strecher VJ, Falk EB, Self-affirmation activates brain systems associated with self-related processing and reward and is reinforced by future orientation, Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 11 (2016) 621–629. 10.1093/scan/nsv136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Steele CM, The Psychology of Self-Affirmation: Sustaining the Integrity of the Self, in: Berkowitz L (Ed.), Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, Academic Press, 1988: pp. 261–302. 10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60229-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Cohen GL, Sherman DK, The Psychology of Change: Self-Affirmation and Social Psychological Intervention, Annual Review of Psychology. 65 (2014) 333–371. 10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Dutcher JM, Creswell JD, Pacilio LE, Harris PR, Klein WMP, Levine JM, Bower JE, Muscatell KA, Eisenberger NI, Self-Affirmation Activates the Ventral Striatum: A Possible Reward-Related Mechanism for Self-Affirmation, Psychol Sci. 27 (2016) 455–466. 10.1177/0956797615625989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Gusnard DA, Akbudak E, Shulman GL, Raichle ME, Medial prefrontal cortex and self-referential mental activity: Relation to a default mode of brain function, PNAS. 98 (2001) 4259–4264. 10.1073/pnas.071043098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Bartra O, McGuire JT, Kable JW, The valuation system: A coordinate-based meta-analysis of BOLD fMRI experiments examining neural correlates of subjective value, NeuroImage. 76 (2013) 412–427. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.02.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Gutchess AH, Kensinger EA, Schacter DL, Aging, self-referencing, and medial prefrontal cortex, Social Neuroscience. 2 (2007) 117–133. 10.1080/17470910701399029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Salat DH, Age-Related Changes in Prefrontal White Matter Measured by Diffusion Tensor Imaging, Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1064 (2005) 37–49. 10.1196/annals.1340.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Winecoff A, Clithero JA, Carter RM, Bergman SR, Wang L, Huettel SA, Ventromedial Prefrontal Cortex Encodes Emotional Value, Journal of Neuroscience. 33 (2013) 11032–11039. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4317-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Reed AE, Carstensen LL, The Theory Behind the Age-Related Positivity Effect, Front. Psychol. 3 (2012). 10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Mather M, Carstensen LL, Aging and attentional biases for emotional faces, Psychol Sci. 14 (2003) 409–415. 10.1111/1467-9280.01455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Mather M, Canli T, English T, Whitfield S, Wais P, Ochsner K, Gabrieli JDE, Carstensen LL, Amygdala responses to emotionally valenced stimuli in older and younger adults, Psychol Sci. 15 (2004) 259–263. 10.1111/j.0956-7976.2004.00662.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Notthoff N, Carstensen LL, Positive messaging promotes walking in older adults, Psychol Aging. 29 (2014) 329–341. 10.1037/a0036748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Notthoff N, Klomp P, Doerwald F, Scheibe S, Positive messages enhance older adults’ motivation and recognition memory for physical activity programmes, Eur J Ageing. 13 (2016) 251–257. 10.1007/s10433-016-0368-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Onken LS, Carroll KM, Shoham V, Cuthbert BN, Riddle M, Reenvisioning Clinical Science: Unifying the Discipline to Improve the Public Health, Clinical Psychological Science. 2 (2014) 22–34. 10.1177/2167702613497932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Marshall AL, Miller YD, Burton NW, Brown WJ, Measuring total and domain-specific sitting: a study of reliability and validity, Med Sci Sports Exerc. 42 (2010) 1094–1102. 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181c5ec18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Booth M, Assessment of Physical Activity: An International Perspective, Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport. 71 (2000) 114–120. 10.1080/02701367.2000.11082794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Chen DL, Schonger M, Wickens C, oTree—An open-source platform for laboratory, online, and field experiments, Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance. 9 (2016) 88–97. 10.1016/j.jbef.2015.12.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Grant PM, Ryan CG, Tigbe WW, Granat MH, The validation of a novel activity monitor in the measurement of posture and motion during everyday activities, Br J Sports Med. 40 (2006) 992–997. 10.1136/bjsm.2006.030262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Trost SG, Mciver KL, Pate RR, Conducting Accelerometer-Based Activity Assessments in Field-Based Research, Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 37 (2005) S531. 10.1249/01.mss.0000185657.86065.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Chomistek AK, Yuan C, Matthews CE, Troiano RP, Bowles HR, Rood J, Barnett JB, Willett WC, Rimm EB, Bassett DR, Physical Activity Assessment with the ActiGraph GT3X and Doubly Labeled Water, Med Sci Sports Exerc. 49 (2017) 1935–1944. 10.1249/MSS.0000000000001299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Aguilar-Farias N, Martino-Fuentealba P, Salom-Diaz N, Brown WJ, How many days are enough for measuring weekly activity behaviours with the ActivPAL in adults?, Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport. 22 (2019) 684–688. 10.1016/j.jsams.2018.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].McAuley E, The role of efficacy cognitions in the prediction of exercise behavior in middle-aged adults, J Behav Med. 15 (1992) 65–88. 10.1007/BF00848378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ, The Pittsburgh sleep quality index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research, Psychiatry Research. 28 (1989) 193–213. 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Gard DE, Gard MG, Kring AM, John OP, Anticipatory and consummatory components of the experience of pleasure: A scale development study, Journal of Research in Personality. 40 (2006) 1086–1102. 10.1016/j.jrp.2005.11.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Marin RS, Biedrzycki RC, Firinciogullari S, Reliability and validity of the apathy evaluation scale, Psychiatry Research. 38 (1991) 143–162. 10.1016/0165-1781(91)90040-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Fischer JS, LaRocca NG, Miller DM, Ritvo PG, Andrews H, Paty D, Recent developments in the assessment of quality of life in Multiple Sclerosis (MS), Mult Scler. 5 (1999) 251–259. 10.1177/135245859900500410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Kroll T, Kehn M, Ho P-S, Groah S, The SCI Exercise Self-Efficacy Scale (ESES): development and psychometric properties, International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 4 (2007) 34. 10.1186/1479-5868-4-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Dweck CS, Self-theories: Their Role in Motivation, Personality, and Development, Psychology Press, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- [41].Markland D, Ingledew DK, The measurement of exercise motives: Factorial validity and invariance across gender of a revised Exercise Motivations Inventory, British Journal of Health Psychology. 2 (1997) 361–376. 10.1111/j.2044-8287.1997.tb00549.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Duckworth AL, Quinn PD, Development and Validation of the Short Grit Scale (Grit–S), Journal of Personality Assessment. 91 (2009) 166–174. 10.1080/00223890802634290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Scheier MF, Carver CS, Bridges MW, Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): A reevaluation of the Life Orientation Test., Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 67 (1994) 1063–1078. 10.1037/0022-3514.67.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Steger M, Frazier P, Oishi S, Kaler M, The Meaning in Life Questionnaire: Assessing the Presence of and Search for Meaning in Life, Journal of Counseling Psychology. 53 (2006). 10.1037/0022-0167.53.1.80. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Vallerand RJ, O’connor BP, Construction et Validation de l’Échelle de Motivation pour les Personnes Âgées (EMPA), International Journal of Psychology. 26 (1991) 219–240. 10.1080/00207599108247888. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Harwood TM, Beutler LE, Groth-Marnat G, Integrative Assessment of Adult Personality, Third Edition, Guilford Press, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- [47].Russell D, Peplau LA, Cutrona CE, The revised UCLA Loneliness Scale: Concurrent and discriminant validity evidence, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 39 (1980) 472–480. 10.1037/0022-3514.39.3.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].American Community Survey Questionnaire, (2018). https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/.

- [49].Resnick B, Jenkins LS, Testing the Reliability and Validity of the Self-Efficacy for Exercise Scale, Nursing Research. 49 (2000) 154–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Roque NA, Boot WR, A New Tool for Assessing Mobile Device Proficiency in Older Adults: The Mobile Device Proficiency Questionnaire, J Appl Gerontol. 37 (2018) 131–156. 10.1177/0733464816642582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].McCullough ME, Emmons RA, Tsang J-A, The grateful disposition: A conceptual and empirical topography., Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 82 (2002) 112–127. 10.1037/0022-3514.82.1.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Pachana NA, Byrne GJ, Siddle H, Koloski N, Harley E, Arnold E, Development and validation of the Geriatric Anxiety Inventory, International Psychogeriatrics. 19 (2007) 103–114. 10.1017/S1041610206003504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL, Lum O, Huang V, Adey M, Leirer VO, Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: A preliminary report, Journal of Psychiatric Research. 17 (1982) 37–49. 10.1016/0022-3956(82)90033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Fredrickson BL, Chapter One - Positive Emotions Broaden and Build, in: Devine P, Plant A (Eds.), Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, Academic Press, 2013: pp. 1–53. 10.1016/B978-0-12-407236-7.00001-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Lang FR, Carstensen LL, Time counts: Future time perspective, goals, and social relationships., Psychology and Aging. 17 (2002) 125–139. 10.1037/0882-7974.17.1.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Huskisson E, Occasional Survey MEASUREMENT OF PAIN, (n.d.). /paper/Occasional-Survey-MEASUREMENT-OF-PAIN-Huskisson/1735527582a3dea37cf67459df1c22eb2588b16c (accessed September 11, 2020).

- [57].Veale JF, Edinburgh Handedness Inventory – Short Form: A revised version based on confirmatory factor analysis, Laterality. 19 (2014) 164–177. 10.1080/1357650X.2013.783045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Mailey EL, White SM, Wójcicki TR, Szabo AN, Kramer AF, McAuley E, Construct validation of a non-exercise measure of cardiorespiratory fitness in older adults, BMC Public Health. 10 (2010) 59. 10.1186/1471-2458-10-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Jurca R, Jackson AS, LaMonte MJ, Morrow JR, Blair SN, Wareham NJ, Haskell WL, van Mechelen W, Church TS, Jakicic JM, Laukkanen R, Assessing Cardiorespiratory Fitness Without Performing Exercise Testing, American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 29 (2005) 185–193. 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Rikli RE, Jones CJ, Senior Fitness Test Manual, Human Kinetics, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- [61].Guralnik JM, Simonsick EM, Ferrucci L, Glynn RJ, Berkman LF, Blazer DG, Scherr PA, Wallace RB, A Short Physical Performance Battery Assessing Lower Extremity Function: Association With Self-Reported Disability and Prediction of Mortality and Nursing Home Admission, J Gerontol. 49 (1994) M85–M94. 10.1093/geronj/49.2.M85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Wittich W, Phillips N, Nasreddine ZS, Chertkow H, Sensitivity and Specificity of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment Modified for Individuals who are Visually Impaired, Journal of Visual Impairment & Blindness. 104 (2010) 360–368. 10.1177/0145482X1010400606. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Tun PA, Lachman ME, Telephone assessment of cognitive function in adulthood: the Brief Test of Adult Cognition by Telephone, Age Ageing. 35 (2006) 629–632. 10.1093/ageing/afl095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Germine L, Nakayama K, Duchaine BC, Chabris CF, Chatterjee G, Wilmer JB, Is the Web as good as the lab? Comparable performance from Web and lab in cognitive/perceptual experiments, Psychon Bull Rev. 19 (2012) 847–857. 10.3758/s13423-012-0296-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Esteban O, Birman D, Schaer M, Koyejo OO, Poldrack RA, Gorgolewski KJ, MRIQC: Advancing the automatic prediction of image quality in MRI from unseen sites, PLoS One. 12 (2017). 10.1371/journal.pone.0184661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Esteban Oscar, Blair Ross, Markiewicz Christopher J, Berleant Shoshana L, Moodie Craig, Ma Feilong, Isik Ayse Ilkay, Erramuzpe Asier, Goncalves Mathias, Poldrack Russell A., Gorgolewski Krzysztof J., poldracklab/fmriprep: 1.0.0-rc5, (2017). 10.5281/zenodo.996169. [DOI]

- [67].Peirce JW, PsychoPy—Psychophysics software in Python, Journal of Neuroscience Methods. 162 (2007) 8–13. 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2006.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Peirce JW, Generating stimuli for neuroscience using PsychoPy, Front. Neuroinform. 2 (2009). 10.3389/neuro.11.010.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Kleiner M, What’s new in Psychtoolbox-3?, (n.d.) 89.

- [70].Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG, Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support, Journal of Biomedical Informatics. 42 (2009) 377–381. 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Whitfield-Gabrieli S, Ghosh SS, Nieto-Castanon A, Saygin Z, Doehrmann O, Chai XJ, Reynolds GO, Hofmann SG, Pollack MH, Gabrieli JDE, Brain connectomics predict response to treatment in social anxiety disorder, Mol. Psychiatry. 21 (2016) 680–685. 10.1038/mp.2015.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Doehrmann O, Ghosh SS, Polli FE, Reynolds GO, Horn F, Keshavan A, Triantafyllou C, Saygin ZM, Whitfield-Gabrieli S, Hofmann SG, Pollack M, Gabrieli JD, Predicting Treatment Response in Social Anxiety Disorder From Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging, JAMA Psychiatry. 70 (2013). 10.1001/2013.jamapsychiatry.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Baniqued PL, Gallen CL, Voss MW, Burzynska AZ, Wong CN, Cooke GE, Duffy K, Fanning J, Ehlers DK, Salerno EA, Aguiñaga S, McAuley E, Kramer AF, D’Esposito M, Brain Network Modularity Predicts Exercise-Related Executive Function Gains in Older Adults, Front. Aging Neurosci. 9 (2018). 10.3389/fnagi.2017.00426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Gabrieli JDE, Ghosh SS, Whitfield-Gabrieli S, Prediction as a Humanitarian and Pragmatic Contribution from Human Cognitive Neuroscience, Neuron. 85 (2015) 11–26. 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.10.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]