Abstract

Trauma is prevalent among children and adolescents, with youth of color generally reporting greater exposure compared to White youth. One factor that may account for this difference is racial stress, which can manifest into trauma symptoms. Although racial stress and trauma (RST) significantly impacts youth of color, most of the research to date has focused on adult populations. In addition, little attention has been given to the impact of the ecological context in how youth encounter and cope with RST. As such, we propose the Developmental and Ecological Model of Youth Racial Trauma (DEMYth-RT), a conceptual model of how racial stressors manifest to influence the trauma symptomatology of children and adolescents of color. Within developmental periods, we explore how individual, family, and community processes influence youth’s symptoms and coping. We also discuss challenges to identifying racial trauma in young populations according to clinician limitations and the post-traumatic stress disorder framework within the diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders—fifth edition (DSM-5). The article concludes with implications on applying DEMYth-RT in clinical and research settings to address RST for youth of color.

Keywords: Racial trauma, Racial stress, Children and adolescents, Ethnic minority, Ecological contexts

Substantial research has documented the profound effects of stressful life events and traumatic experiences on the psychological health and well-being of children and adolescents (e.g., Pine and Cohen 2002; Yule 2001). While many incidents of childhood trauma go unreported, statistics show that more than one in four children experience a traumatic stressor before adulthood (e.g., Costello et al. 2002). The prevalence of trauma exposure is higher among children and adolescents of color compared to their White counterparts, with many studies indicating that African American and Latinx youth often report the highest exposure (e.g., Buka et al. 2001; Hatch and Dohrenwend 2007; Hussey et al. 2006). Evidence also suggests that post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is prevalent among youth and young adults of color (e.g., Abram et al. 2004; Pole et al. 2008; Roberts et al. 2011). One factor that may explain higher rates of trauma exposure for youth is racial trauma, dangerous or frightening race-based events, stressors, or discrimination. Although racial trauma is similar to PTSD, and can lead to a PTSD diagnosis, it is distinct due to ongoing collective and individual injuries from exposure and re-exposure to racial stress, which can collectively become traumatic (Comas-Díaz et al. 2019). Racial trauma is likely underreported due to clinician lack of awareness, clinician bias and discomfort surrounding racial topics, and the narrow and exclusive scope of the diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders-fifth edition (DSM-5) PTSD criteria (e.g., Bryant-Davis and Ocampo 2006; Comas-Díaz 2016; Williams et al. 2018b).

Despite theoretical models (Carter 2007; Helms et al. 2012; Williams et al. 2018b) and empirical research (Carter 2007; Kaholokula 2016; Williams et al. 2018a) evidence documenting the consequences of racial trauma for adults, there is little research on children and adolescents’ racial trauma across developmental periods. In addition, given the importance of families and communities to the psychosocial development of children and adolescents, little consideration has been given to the influence of these ecologies in youth’s experience of, and coping with, racial trauma. Thus, in this article, we will begin by defining constructs and discussing the impact of racial stress and trauma (RST) on youth of color during three broad developmental periods (i.e., preschool/elementary, middle school, and high school). Furthermore, we will take an ecological approach to understand how RST impacts the child, family, and community and how these systems are integral to coping with RST. We bridge these gaps by introducing the Developmental and Ecological Model of Youth Racial Trauma (DEMYth-RT) and conclude with clinical and research recommendations to move the field forward.

Race and Racism Defined

Research literature has contended with the concept of race throughout time and disciplines (see Betancourt and López 1993). While one singular definition does not exist, it is important to understand the major arguments underlying race. At the center of the argument is the notion that because race is not a biological construct, it should not be proposed as a categorization in scientific research. Race scholars, however, note that the ramifications of perceived race are real, thus, categorizations are useful in codifying the systemic outcomes in relation to different groups (Smedley and Smedley 2005). Still some argue that races are biologically distinct and outcomes associated with the categorization lend themselves to hereditary and hierarchical findings (Plomin 2018). Within this conceptual paper, we agree with a definition posited by Helms et al. (2005) in that race is indeed real, but as a sociopolitical categorization that has been used to differentiate groups via phenotypical characteristics for hierarchical stratification (Helms et al. 2005). Of greatest importance to the discussion, however, is that there is a lack of biological evidence supporting inherent distinctions between racial groups. As such, evidence that appears to support group differences along racial lines is a function of sociodemography, or the interaction between groups and physical conditions (Williams and Jackson 2005). Along with other scholars, we propose that youth of color are members of both a racial group, the social construct which is acknowledged within the United States, and an ethnic group, people with a shared nationality, culture, language and/or religion (e.g., Cooper et al. 2005). Given that RST can be based on race (e.g., Black, White, Asian) and/or ethnicity (e.g., West Indian, Dominican, Japanese), we use racial–ethnic to be comprehensive.

Racial discrimination, or differential treatment toward individuals of a given race, may be particularly debilitating for members of stigmatized racial groups (Salter et al. 2018). Racism is the system by which racial discrimination thrives within the United States, and the system has typically benefited European Americans while harming members of other racial groups, including African, Latinx, Asian, and Native American Indians (ALANAs; LaVeist 1994). Although substantial literature exists regarding racial discrimination and wellness outcomes in adult populations (e.g., depression, anxiety, sleeplessness, hypertension, cardiovascular disease; Berger and Sarnyai 2015), Pachter and Garcia Coll (2009) illuminated the paucity of research focused on children. The majority of child-based studies exploring racial discrimination are focused on African American populations, in which upward of 90% experience racial discrimination as early as 8 years old (e.g., Pachter and Garcia Coll 2009; Priest et al. 2013). Compared to research on African American youth, there is less literature on racial discriminatory experiences of other ALANA youth, even with a growing Latinx and Asian American demography (Priest et al. 2013). As such, two things remain relatively overlooked regarding ALANA youth and racial discrimination: (1) how RST experiences may manifest across the lifespan for ALANA youth and (2) how the individual, family, and community systems influence youth’s exposure to, stress from, and coping response to RST.

Trauma During Childhood and Adolescence

Stressful life events and traumatic experiences can have a detrimental and lasting impact on the psychological health and well-being of children and adolescents (Arseneault et al. 2011; Copeland et al. 2007; Greeson et al. 2011). A traumatic event is a dangerous, frightening, or violent incident that involves actual or threatened death or a threat to the bodily integrity of self or others (American Psychiatric Association 2013, p. 271). For children, witnessing a traumatic event that threatens the safety or life of a loved one could be just as traumatic as a direct interpersonal incident given that children’s sense of security depends on the perceived safety of significant others in their lives. Experiencing a traumatic event can initiate lasting physical, physiological, emotional, psychological, or social effects that impact youth’s daily functioning and well-being (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA], 2014). One of the most commonly diagnosed trauma disorders is PTSD, which is a disabling condition that impacts cognitions, behaviors, and affect (Kessler et al. 1995; Yule 2001). Those diagnosed with PTSD engage in avoidance of situations, people, or reminders of their traumatic experience to lessen anxiety and distress. Children who have experienced traumatization and who may have a formal diagnosis of PTSD, or a similar trauma or stressor related disorder, often have co-occurring psychological sequelae (Copeland et al. 2007). Although there is burgeoning literature on childhood trauma, a significant amount of research on PTSD is adult-based, which may not directly apply to children and adolescents (Copeland et al. 2007).

Among community samples of children and adolescents, more than two-thirds of youth report experiencing at least one traumatic event by the age of 16 (e.g., Copeland et al. 2007; Costello et al. 2002). Although several studies indicate that a significant number of youth experience trauma, the prevalence is still underreported given that children and adolescents may be less likely to recognize trauma or report the trauma to safe adults. Furthermore, the estimates of exposure to trauma varies by racial–ethnic differences. ALANA groups report exposure to more traumatic events compared to their White counterparts (e.g., Buka et al. 2001; Hatch and Dohrenwend 2007), likely due in part to experiences of racism broadly (Jernigan and Daniel 2011; Williams et al. 2018b). Correspondingly, children and adolescents of color report more encounters with racial discrimination than White youth (Fisher et al. 2000; Romero and Roberts 1998; Seaton et al. 2008), contributing to differential experiences of racial stress and trauma. Trauma may be more disabling for youth of color who contend with traumatic experiences that may be overlooked (e.g., racism), thereby posing a threat to children’s physical integrity and psychological health.

Oversight of Racial Trauma

Despite evidence that individuals of color can be traumatized by historical, interpersonal, or vicarious encounters with racial discrimination within their communities, experiences with racial trauma may be misperceived, dismissed, or unacknowledged by clinicians (Bryant-Davis 2007; Carter 2007; Helms et al. 2012). Overlooked experiences of RST may include humiliating and shaming events, threats of harm and injury, and witnessing racial discrimination toward other ALANA people (Comas-Díaz et al. 2019). Significant evidence documents that different forms of racial stress are associated with physiological problems (e.g., Huynh 2012), substance use (e.g., Gibbons et al. 2004), conduct problems (Brody et al. 2006), and negative psychological symptoms (e.g., Assari et al. 2017), including trauma symptoms (e.g., Flores et al. 2010; Lewis et al. 2018) among youth and young adults of color. Of note, recent studies indicate that exposure to violence on electronic devices including the television and internet are linked with trauma symptoms and other psychological sequelae (Bernstein et al. 2007; Bor et al. 2018; Naeem et al. 2012; Tynes et al. 2012). This is particularly relevant to youth who report frequent use of technological devices and engagement on social media, including media coverage and discussion about racially stressful and traumatic incidents (Anyiwo under review; Quintana and McKown 2008). These events include, but are not limited to, viewing the unarmed killing of Black and Brown children by police on television or the Internet (Bor et al. 2018; Thomas and Blackmon 2015), witnessing the persistent use of racial epithets or racial teasing on social media (Tynes et al. 2015), and hearing about efforts to hurt or murder those from one’s racial background. Indeed, youth of color have reported negative psychosocial outcomes in response to vicarious racial stress (e.g., TV exposure, online encounters; Douglass et al. 2016), and Quintana and McKown (2008) note that vicarious exposure to racial discrimination may cause trauma symptoms and affect psychological adjustment.

Clinicians’ oversight, biases, and discomfort talking about issues of race can limit their initial ability to recognize whether children and adolescents’ experiences with RST warrant treatment or a PTSD diagnosis (Franklin et al. 2006; Pinderhughes 1989). Oversight of RST can impact the clinician’s ability to properly assess and diagnose the traumatic experience and lead to inappropriate treatment decisions. Clinician bias and discomfort discussing racial topics may also impact rapport and treatment outcomes (Pieterse 2018; Sue et al. 2010). Racial trauma may be unacknowledged due to a perception that it is “subjective” or unmeasurable, rendering the question whether racial events could in fact be traumatic (Bryant-Davis and Ocampo 2006; Carter 2007). However, similar to other traumas, an individual’s perception of whether an incident was traumatic is a critical element of treatment (Bryant-Davis 2007; Carter 2007; Helms et al. 2012). Clinicians’ lack of awareness on these issues and limited understanding of how racial trauma is applicable to the definition of PTSD may lead a misunderstanding of the etiology of trauma, invalidation of trauma, and cause some to erroneously believe that racial trauma is a “myth.”

Understanding Racial Trauma Within a DSM-5 Framework

Racial trauma can fit the definition of PTSD as defined by the DSM-5 when it involves a Criterion A event, such as a racially motivated assault. The DSM-5 also recognizes that reoccurring exposure to mildly traumatic incidents with enough frequency can contribute to PTSD as well, and this often the case with racial trauma (Williams et al. 2018b). However, as some scholars have previously noted, what is considered a Criterion A event is subjective and narrow (e.g., Holmes et al. 2016), and so one can suffer from racial trauma with or without the occurrence of such an event as defined by the DMS-5. Furthermore, research findings indicate that covert discrimination may be equally or even more distressing than overt discrimination (O’Keefe et al. 2015; Sue et al. 2007; Williams et al. 2018c). Covert discrimination can result in anxiety as people of color attempt to ascertain whether an unpleasant interpersonal experience was based on race and whether perpetrators are trustworthy or dangerous. Much like sexual harassment, where smaller, ongoing distressing experiences can culminate into traumatization (Larsen and Fitzgerald 2011; Palmieri and Fitzgerald 2005), ongoing racially discriminatory events can have a cumulative effect which may increase hypervigilance, avoidance, and contribute to PTSD symptoms or the development of a PTSD diagnosis (Williams et al. 2018b). Trauma-related symptoms such as anxiety, depression, and negative future outlook may be linked to experiences of covert discrimination, and subtle mistreatment in the form of microaggressions, which can be associated with trauma symptomology in young adults (Nadal et al. 2014; Williams et al. 2018c). Although several symptoms associated with PTSD may be evident in RST, others such as avoidance of dominant groups or cognitive distortions about safety based on race, may be challenging to identify. RST may also be challenging to address in racial environments in which children do not make the decision on where to live or attend school.

While not all racial traumas will lead to PTSD, for those who have historical and genetic vulnerabilities, racial events may have increased potential to lead to PTSD (Williams et al. 2018b; Gone et al. 2019). Historical and cultural trauma can be passed on to subsequent generations through both social and epigenetic mechanisms (e.g., Bierer et al. 2014; Kira 2010), and since traumatization is cumulative, prior traumas and racial oppression also increase risk of PTSD. These vulnerabilities result in a baseline of stress that is exacerbated by ongoing experiences of racial maltreatment (i.e., overt and/or covert racism). Following a triggering experience of racism, which likely includes a perceived threat to safety, life, or personhood, the individual experiences emotions associated with the traumatic event (e.g., fear, disbelief, anger). Subsequently, and possibly after having their experience invalidated and having no perceived safe space to process the encounter, the individual begins to experience the typical symptoms of PTSD (e.g., re-experiencing the event, avoiding trauma reminders, worsening cognitions and mood, altering arousal and hypervigilance for an extended period), causing significant distress or impairment that is not accurately explained or treated. Further, due to the marginalized status of the victim, avenues for professional help may be limited, thus maintaining or worsening traumatization. Collectively, these symptoms involve interpersonal experiences of racism and could result in an individual meeting full criteria for PTSD due to racial trauma.

Applying a Racial Trauma Diagnosis to Youth

In the same way, youth of different ages display differential trauma symptoms in response to traumatic experiences (e.g., Center for Substance Abuse Treatment 2014; Green et al. 1991), we propose that the experiences, interpretations, and resulting symptoms and behaviors of racial trauma may be different for children and adolescents, compared to adults, based on developmental stage. Although specific to racial discrimination, the Brown and Bigler (2005) developmental model of children’s perceptions of racial discrimination suggests that cognitive abilities, situational factors and individual differences, influence how youth perceive and make meaning of racially stressful situations. Applied to racial trauma, as youth develop cognitive skills and learn their social position within the world, their understanding and coping behaviors in response to racially traumatic situations are likely to shift.

The American Psychological Association Presidential Task Force on Traumatic Stress Disorder and Trauma in Children and Adolescents (2009) and the National Traumatic Stress Network (NCTSN 2017) both have acknowledged the potential stressful impact of racial discrimination for children and adolescents, but as previously noted, there is limited literature on racial trauma within childhood and adolescence. Sanders-Phillips (2009) highlighted that racial discrimination is a chronic form of violence and trauma that can influence child outcomes, exacerbate the effects of other forms of violence (e.g., community violence, domestic), and dampen parental and communal support. Although specific to African American children, to our knowledge, Jernigan and Daniel (2011) is the only other article that begins to conceptualize racial trauma for children to date. The scholars highlight the importance of the school context in experiencing and processing racial trauma, which is important given that youth’s encounters with and social support to manage racial stress come from multiple ecological contexts. As indicated by Helms et al. (2012), “Individual trauma and treatment need to be understood within the context of family, community, religion, culture, and sensitive to the sociopolitical history of racism in the community in which the traumatic event occurred” (p. 71). As such, the family and community contexts should also be considered in understanding racial trauma for ALANA children and adolescents.

The Developmental and Ecological Model of Youth Racial Trauma

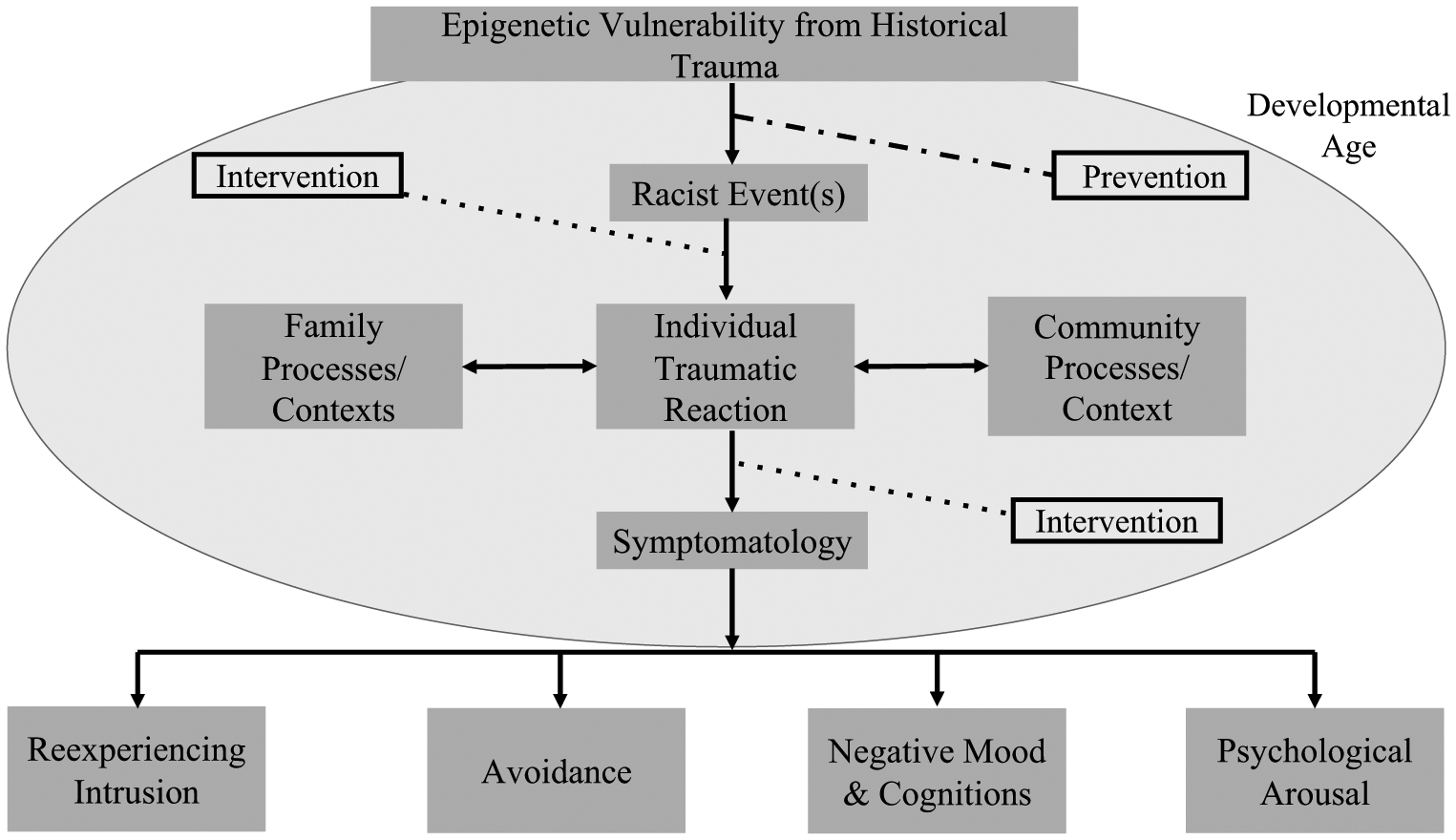

RST is a concerning and persistent problem for children and adolescents that can threaten physical safety, impede psychological integrity, and lead to a traumatic response (e.g., Jernigan and Daniel 2011; NCTSN 2017). The Developmental and Ecological Model of Youth Racial Trauma (DEMYth-RT), proposed here, highlights that the lack of awareness and acknowledgement of RST may lead some to believe that racial trauma is a “myth”, or widely held, but false idea. DEMYth-RT acknowledges the reality of racial trauma and the consequential psychological symptoms of ALANA youth. Within developmental periods, the model provides an ecological framework for how RST can impact family and community systems that the child is embedded within, with attention to how these systems are integral to youth’s interpretation and management of RST. In addition, the model illuminates how prevention and intervention approaches may interrupt the transmission of trauma from in vivo experiences and vicarious processes to youth’s psychological expression and well-being (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Developmental and Ecological Model of Youth Racial Trauma (DEMYth-RT)

Racial Trauma for Preschool and Elementary Children

Childhood (e.g., aged 3–5 years [preschool-kindergarten] and aged 6–11 years [elementary school]) is a critical time for physical, cognitive, language, and socioemotional development. According to the DSM-5, children 6 years of age and under may have different reactions to traumatic experiences compared to older children (e.g., bed wetting, loss or regression in developmentally appropriate functioning and behavior, numbing response) because of their limited ability to verbalize their feelings about threatening and dangerous events (Scheeringa et al. 2001; Three 2005). Yet, young children can be affected by stressful and traumatic experiences that threaten the safety and well-being of themselves or their caregivers (Yasik 2005). The impact of racial trauma may be particularly challenging for small children, who have the ability to recognize racial differences from as early as 3 months (Liu et al. 2011; Sangrigoli and De Schonen 2004), but lack the cognitive understanding and language to report and process racial discrimination. Given that preschool and elementary school age children implicitly assign positive and negative attributions to individuals based on race (Baron and Banaji 2006; Clark and Clark 1950; Spencer and Markstrom-Adams 1990), children can develop a racially targeted view of the world in which they begin to understand that skin color can be a threat to safety and security for themselves and their caregivers. Therefore, direct or vicarious experiences with RST may elicit trauma symptoms, fear, helplessness, and worry about the bodily integrity of themselves and their caregivers based on race.

In understanding how RST influences the family context for all children beginning in childhood, it is important to first acknowledge that historical trauma (e.g., slavery, genocide, mass-incarceration; SAMHSA 2014) affects genetics (e.g., Walters et al. 2011), impacts parenting behaviors (Heart 1999), and has implications for the family system (Danieli 1998; Degruy-Leary 1994; Wardi 1992). Historical trauma is defined as the “cumulative emotional and psychological wounding across generations and over the lifespan emanating from massive group trauma experiences” (Brave Heart 2003, p. 7), and must be accounted for with consideration to younger children and family dynamics. Beyond the consequences of historical trauma, parents must contend with their own encounters with racial stress, which are associated with a myriad of physical and mental health consequences (Geronimus 1996; Giscombé and Lobel 2005; Williams and Mohammed 2009). Parents’ racial stress concurrently impacts aspects of the family system, such as communication (Wardi 1992), parenting behaviors (Anderson et al. 2015), and parental problem solving (e.g., Brave Heart and DeBruyn 1998). In addition, racial trauma can influence caregivers’ emotional availability and cause cognitive pre-occupation, which may prevent them from protecting their children from RST (Lewis et al. 2018). Given that attachment to caregivers and family is important for the management of stressors (Smith and Carlson 1997), young children who perceive a lack of protection from caregivers may feel increasingly overwhelmed by the intensity of physical and emotional responses to racially traumatic experiences.

Daycares, neighborhoods, and schools are common contexts in which young children can experience RST. First, the loss of infants and children from racially traumatic incidents (e.g., racially motivated killings) can have profound consequences on communities including psychological pain, communal morale, human capacity (e.g., future leaders), and the ability to safeguard one’s culture and language (Evans-Campbell 2008). These experiences could lead to communal trauma responses, such as weakened social structures, social malaise, and traumatic grief (Evans-Campbell 2008). Such experiences may amplify the effect of a child’s direct or vicarious encounters with racial trauma within the community. In addition, children of color may begin to experience racism within the community from peers and this behavior is unlikely to be disguised or even recognized as wrong. Previous studies show that by the age of 6, White children can exhibit anti-Black bias, and younger children openly admit their bias (Baron and Banaji 2006). Further, some teachers express bias against children of color in a variety of ways (e.g., increased surveillance, discipline, and expulsions) that leave children of color recognizing differential treatment and preference attributed to race (Gilliam et al. 2016). Thus, children of color may be encountering regular experiences of unaddressed RST within their community from a very early age. However, it is also important to acknowledge that committed schools and teachers can play a role in intentionally combating RST for young children (NCTSN 2017). For example, school staff can promote racial pride, increase awareness and acknowledgement of race, and reduce the consequences of RST by creating a safe and empowering environment for students.

Elementary School Age Child Case Example

Recent immigrant children have a high prevalence of experiencing trauma (Jaycox et al. 2002), and some youth are refugees who fled their country of origin due to racially traumatic circumstances, such as fear of persecution due to race (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees 2001). To illustrate, Laura is a 5-year-old girl from Central America and lives with her relatives who migrated to the United States (US). Laura’s mother paid an acquaintance to transport her daughter on the journey to the US because her mother was worried about the pervasive gang violence targeting people of her ethnic group, who were considered “lower class” and were typically of a darker skin tone. As a result, her mother was worried for Laura’s safety as well as her own. Laura’s mother provided little warning about the journey because she was nervous, fearful, and did not know how to explain the unexpected move in a way she thought her daughter may understand. The separation was particularly hard because Laura and her mother had a strong attachment.

Laura witnessed traumatic events (e.g., death of others) along the way, and although she made it to her destination safely, she had a difficult time adjusting to the new environment. In addition, in her new school, children teased Laura for her “broken English,” dark skin, and ethnic facial features. At home, Laura was frequently reminded of her journey because of constant exposure to the news highlighting that people from her home country were being killed and detained. Her family often talked about the news and discussed concern about Laura’s mother making the journey to join them in the United States. Laura displayed a decreased appetite, heightened reaction to strangers, and was fearful of leaving the house. She had difficulty sleeping, often having nightmares of ethnically motivated violence (i.e., violence targeted at specific ethnic groups) that she witnessed at home and of the images she saw on television. Laura often interpreted what she saw on television literally without fully grasping the concept of images and videos being repeatedly replayed on television; as such, she kept thinking that the events on television were happening several times a day to people who looked like her and her mother. Laura’s family attributed her mood and odd behaviors to Laura missing her mother and to her difficult journey, and they believed that she would “snap out of it,” Although they were often concerned about her behavior, they did not want to take her to the doctor or a mental health professional out of fear that she would be deported because of her legal status. The family remained silent and hoped that Laura would begin “acting like a normal child” after more time passed.

Racial Trauma for Middle School Age Children

As children develop into early and middle adolescence (e.g., 12–14), they are often beginning or continuing to contend with the self in relation to group identities (e.g., Tajfel and Turner 1986). In addition to rapid physical growth, which, for some populations (e.g., Black boys), may contribute to exaggerated stereotyping (e.g., Goff et al. 2014), there are cognitive and psychological changes associated with the exploration of an autonomous identity. Increased cognitive maturity helps in the development of ALANA youth’s racial–ethnic identity (Quintana 2007), however, it may also reveal the ways in which RST impact the child as a member of their racial group. Youth may consciously or unconsciously internalize RST, which may lead to negative attributions about how they view their own racial group (i.e., private regard) and how they perceive others view their racial group (i.e., public regard) (e.g., see Sellers et al. 2006). School age ALANA children may exhibit a variety of reactions to trauma, particularly racial trauma (NCTSN 2008; Sanders-Phillips 2009). Although youth may have the cognitive ability to perceive differential treatment based on race, school age youth may not connect the experiences with their mood (e.g., trauma symptoms), behavior, and self-image. Of note, youth who have directly or vicariously experienced trauma may become preoccupied about their own safety or the safety of peers and family members (Greenwald 2014). Trauma experiences, including RST, may lead to distractibility and problems in school that could easily be misinterpreted by adults as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), phobias, or other anxiety disorders (e.g., Thompson and Massat 2005).

Regarding the family, school age ALANA adolescents and their caregivers often begin or adjust the content and frequency of racial socialization (i.e., communication regarding racial behaviors and attitudes; Coll and Pachter 2002; Hughes and Chen 1999; Hughes et al. 2006), during this stage of heightened racial awareness. For example, as youth move out of childhood, parents generally begin to have more conversations with their children about preparing for racial bias (Hughes and Chen 1999). Coping with RST is an additional task for families of color that extends beyond general coping socialization strategies (e.g., Anderson et al. 2018). Such a task may be seen as burdensome by some, given that parents must often contend with, reflect on, and resolve their own experiences with racial discrimination (Anderson and Stevenson 2019). Parents’ racial discrimination may influence the socialization messages parents convey to their children (Saleem et al. 2016) and could foster feelings of parental incompetency in assisting in the resolution of their adolescents’ racial stressors. Of note, new immigrant families may struggle in appropriately adjusting their racial socialization within a new context.

In addition, youth are often shaped by other socializing agents within their community during this developmental stage. Of greatest salience is social media, in which younger adolescents are beginning their foray (O’Keeffe and Clarke-Pearson 2011). Research has demonstrated the harm of online discrimination for youth (Tynes et al. 2015), which further questions whether the PTSD Criterion A components are inclusive of these “virtual world” (i.e., online) experiences. The racialized lens of bullying or harassment activities may be contributing to a more complex psychological injury or trauma. In the “physical world” (i.e., lived) community settings, the toll of RST may be exacerbated after the community contends with a loss of a young adolescent at the hands of law enforcement, for example, Tamir Rice—a 12-year-old boy with a toy gun, and Jason Pero—a 14-year-old boy shot on a reservation. While active forms of protest may be a way to cope with immediate calls for justice (e.g., Anyiwo et al. 2018; Hope and Jagers 2014), some youth may feel unmotivated, numb, or hopeless immediately following a tragic loss.

Middle School Age Child Case Example

The appropriation and misrepresentation of Native American Indian populations at schools and sporting events can precipitate RST for these youth (see Baca 2004; Friedman 2013). To illustrate, Jason is a 11-year-old Native American Indian boy who attends Savage Warrior middle school, which is predominantly White. At school, Jason often feels isolated as one of the few students of Native American Indian descent. His isolation becomes even more apparent during school-pep rallies and sporting events when the “Native American mascot” comes out waving a tomahawk and making a reverberating noise that seems to unite his peers in school spirit, but trigger physiological symptoms (e.g., sweating, heart-racing) for him. Jason is particularly triggered by such events given that he is the victim of online racial teasing and bullying. Jason often feels that both he and his culture are misunderstood and devalued. School is an unwelcoming and often hostile racial environment as Jason hears racial epithets and experiences racially targeted bullying. These situations elicit trauma symptoms (e.g., hypervigilance, depressive symptoms, nightmares) and decrease his focus in class. Jason believes that the portrayal of his culture is disrespectful and offensive, but he developed symptoms of internalized racism as evident through his self-critical thoughts, feelings of shame regarding his racial–ethnic identity, and anger that his physical features make it difficult to blend into the mainstream culture.

Racial Trauma for High School Age Youth

For high school-aged youth (i.e., 15–18 years), adolescence is marked by increased physical, social, and cognitive changes (e.g., Piaget et al. 1958; Steinberg and Morris 2001). During this developmental period, youth develop formal operational thought, deductive reasoning, and problem-solving skills. For ALANA youth, these changes coalesce with increased understanding of advanced forms of racism (e.g., institutional racism), exposure to racial discrimination, and ability to make meaning of racial encounters (Brown and Bigler 2005). Increased social comparison and sensitivity to others’ evaluations are also characteristic of adolescence (Krayer et al. 2007). As such, the experience of RST during this sensitive period could impact youth’s severity of trauma symptoms, sense of self, hope, and ability to heal from these incidents (Heard-Garris et al. 2018; Jernigan and Daniel 2011). Adolescents’ trauma symptoms may manifest similarly to adults, but could also include unique features such as rebellion, social withdrawal, increase in risky activities, delinquency, and other action-oriented responses to trauma (Hamblen 2001). Teens may also engage in different coping strategies and help-seeking behaviors (Chapman and Mullis 2000; Copeland and Hess 1995; Rickwood et al. 2005) to manage racial trauma. For example, some youth may cope with racial trauma by dissociating or compartmentalizing; however, if trauma symptoms go unaddressed during adolescence, youth may develop secondary symptoms. Similar to the literature on complex trauma, or experiences with multiple traumatic events (Cloitre et al. 2009; Cook et al. 2017, 2003), the accumulation of stressful racial encounters may prolong PTSD symptoms and sequelae, thus increase vulnerability to subsequent traumatic exposure and symptoms in later adolescence and adulthood.

Familial relationships for adolescent youth can be fraught with increasing tension over autonomy and cohesion (Steinberg 1990). Although peers play an increasing and often much larger role for youth during adolescence, ALANA youth may find it challenging to gain support regarding RST solely from same-age peers. Just as parents adjust their parenting strategies based on their child’s age and needs (Minuchin 1985), ALANA parents must adjust how they engage in mature conversations with their teenagers (Steinberg and Silk 2002) related to safety and racial discrimination (Coll and Pachter 2002; McAdoo 2002). For example, parents may provide more personal and historical explanations and discuss complex forms of racism (e.g., institutional), which can influence youth’s outcomes (Saleem and Lambert 2015), while also acknowledging the reality of adolescents’ desire for individuation and social interactions. Parents must contend with the reality that their children may face more discriminatory experiences outside of their supervision. Given that parents are worried about youth’s increase in risky behaviors during adolescence (Steinberg and Silk 2002), they may also worry about the contexts that youth of color find themselves in, particularly in relation to authority and race. Such conflict may prove challenging in helping older adolescents from a parental standpoint, however, older siblings, extended family, and natural mentors within the community may assist to fill this gap (Stanton-Salazar 1997).

The community (e.g., neighborhood, school) in which adolescents live has significant implications for the exposure and experience of RST. Given the increased autonomy of adolescents, youth may be more likely to directly witness or experience RST within their community, and for some youth, they may repeatedly witness incidents, even in spaces designed to be safe such as youth recreation centers or school (Jernigan and Daniel 2011). Given that adolescents have the cognitive capacity to recognize racial discrimination and the potentially damaging consequences for their lives and health, some youth may experience hypervigilance and frequent worry about RST within their community. This may be particularly true for teenagers who are more likely to have unsupervised use of electronic devices and exposure to social media content, including hate crimes and the killing of ALANA teens. Two examples are Jordan Edwards–a 15-year-old boy shot in the back of the head by a police officer–and Trayvon Martin—a 17-year-old boy shot by a neighborhood watch community member. While some adolescents may be proactive in pushing back against racially targeted violence within their community (e.g., protests, vigils, activism), attempts could lead to reoccurring RST exposure due to punitive law enforcement or community responses. Of note, aspects of the neighborhood such as social cohesion, may influence how youth manage racial stress by protecting against the effects of racial discrimination on youth’s depressive symptoms (Saleem et al. 2018).

High School Age Adolescent Case Example

Stereotypes (Pitner et al. 2003; Steele 1997) and the concept of “model-minority” can exacerbate feelings of RST throughout adolescence and into adulthood (Awad et al. 2019; Qin et al. 2008). As an example, Lee’s parents immigrated to the United States prior to Lee’s birth; his father immigrated from China and his mother from Palestine. Lee was raised with a tricultural identity (i.e., Chinese, Palestinian, American) due to his parents’ cultural socialization. Lee wanted to explore his passion of music production, but his parents encouraged him to remain focused on the advancement of his educational pursuits because they both immigrated for better educational opportunities as medical doctors. In high school, Lee was called upon frequently by teachers and asked for academic help from his peers, even though he did not perceive himself as academically gifted. The pressure of the “model-minority” stereotype caused significant stress and worry for Lee. In addition, the negative depiction of Palestine in the media contributed to an uncomfortable racial climate at school. He experienced frequent microaggressions and discrimination from peers, including questions such as “Why does your mother wear that wrap on her head?” and “Do you think your family knows any terrorists?” One day during class, Lee was sent to the principal’s office by a teacher for wearing a shirt representing Palestine. Lee was asked to change because it made others uncomfortable. Due to the racial climate and the stress that Lee was put under to perform by classmates, teachers, and parents, he began avoiding school, dissociating, having nightmares about being racially targeted, and experiencing worry and hypervigilance about his performance and race. These symptoms were misinterpreted as anxiety by teachers, who recommended a mental health consultation. Yet, Lee’s family was against the idea due to cultural mistrust and the minimization of Lee’s difficulties, which prevented him from accessing treatment. In Lee’s senior year, he continued feeling isolated from his peers and experienced frequent worries about being pulled over and arrested because of his race, given the number of videos online showing racial policing of Palestinians. He received no intervention for his stress and trauma-laden symptomatology, which had a significant impact on his academic engagement and achievement.

Prevention and Intervention Through Future Research and Clinical Practice

Attention to the important issue of RST is emerging within the research literature. Although empirical studies and accompanying measures still focus primarily on adult experiences (e.g., Carter 2007), scholars are calling for greater focus on youth experiences (e.g., Anderson and Stevenson 2019; Jernigan and Daniel 2011; Jones and Neblett 2016; Svetaz et al. 2018). In particular, Wade et al.’s (2014) exploration of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) in urban populations led to the theoretical expansion of ACEs to include items on discrimination, more fully conceptualizing the experiences of ALANA youth. There remains the need for investigators to examine whether the type of racial trauma and resulting symptoms differ for children of different racial–ethnic backgrounds. It is also necessary for researchers to examine racial trauma for children and adolescents to clarify the prevalence and effects of this psychological stressor on youth. For example, at the time this paper was written, scholars do not have an extensive understanding of how the racial criminalization and hostility along with the family separation at the United States and Mexico border will impact families immigrating to the United States (Dreby 2015). Appropriate data on RST for these families could bring to light the idea that such a separation is traumatic not only because families were forcefully divided, but also because of the conditions of detainment facilities and political and ethnic-racial motives behind such policies. As such, research utilizing language-specific interviews will be vital in capturing the totality of experiences faced by these youth and their families, particularly with regard to their race, immigration status, and the current geopolitical environment.

Arguably, one of the most important clinical questions regarding the treatment of any presenting problem is how to conceptualize and treat symptomatology in different racial–ethnic groups. While some scholars argue for cultural adaptation to existing universal interventions (Bernal and Domenech Rodríguez 2012), others argue the need for targeted interventions created with cultural specificity of the stressor (Pieterse 2018). Still others consider a focus on ethnicity and race within universal interventions to promote positive psychosocial outcomes with diverse youth (e.g., Umaña-Taylor et al. 2018). Although programming approaches for ALANA populations differs, what is less known is in what capacity the topics of race and racism are effectively managed across health care and community settings. The literature indicates this is an area of challenge for many clinicians (Owen et al. 2014; Sue et al. 2010). While scholarship may contend with the notion of clinician’s cultural competence, few studies have conceptualized racial trauma as a focus of this practice with clients (e.g., Pieterse 2018). Interventions which consider how parents can address the RST experienced by children have emerged in recent years (Coard et al. 2004). For example, engaging, managing, and bonding through race [EMBRace] (Anderson et al. 2018), specifically focuses on African American clients and utilizes racial socialization as a tool for children and families to collectively confront the RST presented in sessions. In relation, various clinical settings (e.g., primary care and pediatric wellness visits) have started considering how to integrate such racial socialization techniques in family visits to both address and start the healing process for ALANA families (e.g., Heard-Garris et al. 2018), but clinical application and implementation is still in early stages. In addition, school-based recommendations have been made for educators by students’ varying developmental stages by the NCTSN, Justice Consortium, Schools Committee, and Culture Consortium (2017). Finally, more holistic measurement and assessment of urban and/or ALANA youth ACEs, including discrimination, can make for more accurate treatment options from clinical providers (e.g., Wade et al. 2014).

Conclusions

Given the limited research focus on understanding of RST for children and adolescents, we offer a framework for unpacking how RST can influence children and adolescents’ trauma symptoms with consideration of ecological and developmental contexts. As acknowledged within the literature on racial trauma within adult populations, a discrete racially traumatic incident, or the cumulative effect of several racially stressful incidents, may trigger symptoms consistent with PTSD (Jernigan and Daniel 2011; Quintana and McKown 2008; Williams et al. 2018b). Yet the field has lacked a thorough conceptualization of racial trauma for children and adolescents of color. Given that youth’s understanding of trauma and the resulting symptoms may differ based on age (Center for Substance Abuse Treatment 2014; Green et al. 1991), we propose that the experiences, interpretations, symptoms, and behaviors of racial trauma will be different for youth at different developmental stages. In addition, consistent with the stress and coping literature, the family and community systems that a child is within can influence how youth interpret and manage racial trauma. Through the DEMYth-RT, we introduce a model for acknowledging the existence and resulting psychological symptoms of racial trauma for ALANA youth with developmental and contextual considerations. The goal of the model is to stimulate future work and contribute to knowledge that is critical in healing for ALANA children and adolescents. The recognition and treatment of racial trauma during childhood and adolescence has the potential to change one’s trajectory of well-being and help to close racial disparity gaps in health and education in adulthood. Addressing RST can benefit individuals (e.g., health), communities (e.g., productive citizens and community members), and the greater society (e.g., cost-saving, general culture of health and well-being for all). The prevention and intervention of such important health and wellness indicators starts first with acknowledging that RST is not a myth, but is indeed a reality for ALANA youth.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

References

- Abram KM, Teplin LA, Charles DR, Longworth SL, McClelland GM, & Dulcan MK (2004). Posttraumatic stress disorder and trauma in youth in juvenile detention. Archives of General Psychiatry, 61(4), 403–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association. (2009). Presidential task force on traumatic stress disorder and trauma in children and adolescents. Children and Trauma: Update for mental health professionals. Retrieved December 2018, from https://www.apa.org/pi/families/resources/update.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson AT, Jackson A, Jones L, Kennedy DP, Wells K, & Chung PJ (2015). Minority parents’ perspectives on racial socialization and school readiness in the early childhood period. Academic Pediatrics, 15(4), 405–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson RE, Jones S, Anyiwo N, McKenny M, & Gaylord-Harden N (2018a). What’s race got to do with it? Racial socialization’s contribution to black adolescent coping. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 10.1111/jora.12440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson RE, McKenny MC, & Stevenson HC (2018b). EMBRace: Developing a racial socialization intervention to reduce racial stress and enhance racial coping among black parents and adolescents. Family Process. 10.1111/famp.12412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson RE, & Stevenson HC (2019). RECASTing racial stress and trauma: Theorizing the healing potential of racial socialization in African American families. American Psychologist, 74(1), 63–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anyiwo N, Richards-Schuster, & Jerald (under review). Using critical media literacy and youth-led research to promote the sociopolitical development of Black youth: Strategies from “Our Voices”.

- Anyiwo N, Bañales J, Rowley SJ, Watkins DC, & Richards-Schuster K (2018). Sociocultural influences on the sociopolitical development of African American Youth. Child Development Perspectives. 10.1111/cdep.12276. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arseneault L, Cannon M, Fisher HL, Polanczyk G, Moffitt TE, & Caspi A (2011). Childhood trauma and children’s emerging psychotic symptoms: A genetically sensitive longitudinal cohort study. American Journal of Psychiatry, 168(1), 65–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assari S, Moazen-Zadeh E, Caldwell CH, & Zimmerman MA (2017). Racial discrimination during adolescence predicts mental health deterioration in adulthood: Gender differences among Blacks. Frontiers in Public Health, 5, 104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awad GH, Kia-Keating M, & Amer MM (2019). A model of cumulative racial–ethnic trauma among Americans of Middle Eastern and North African (MENA) descent. American Psychologist, 74(1), 76–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baca LR (2004). Native images in schools and the racially hostile environment. Journal of Sport and Social Issues, 28(1), 71–78. [Google Scholar]

- Baron AS, & Banaji MR (2006). The development of implicit attitudes: Evidence of race evaluations from ages 6 and 10 and adulthood. Psychological Science, 17(1), 53–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger M, & Sarnyai Z (2015). “More than skin deep”: stress neuro-biology and mental health consequences of racial discrimination. The International Journal on the Biology of Stress, 18(1), 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernal GE, & Domenech Rodríguez MM (2012). Cultural adaptations: Tools for evidence-based practice with diverse populations. Washington: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein KT, Ahern J, Tracy M, Boscarino JA, Vlahov D, & Galea S (2007). Television watching and the risk of incident probable posttraumatic stress disorder: A prospective evaluation. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 195(1), 41–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betancourt H, & López SR (1993). The study of culture, ethnicity, and race in American psychology. American Psychologist, 48(6), 629–637. [Google Scholar]

- Bierer LM, Bader HN, Daskalakis NP, Lehrner AL, Makotkine I, Seckl JR, et al. (2014). Elevation of 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 2 activity in Holocaust survivor offspring: Evidence for an intergenerational effect of maternal trauma exposure. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2014.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bor J, Venkataramani AS, Williams DR, & Tsai AC (2018). Police killings and their spillover effects on the mental health of black Americans: A population-based, quasi-experimental study. The Lancet, 392(10144), 302–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brave Heart M (2003). The historical trauma response among natives and its relationship with substance abuse: A Lakota illustration. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 35(1), 7–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brave Heart M, & DeBruyn LM (1998). The American Indian holocaust: Healing historical unresolved grief. American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research, 8(2), 56–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Chen YF, Murry VM, Ge X, Simons RL, Gibbons FX, et al. (2006). Perceived discrimination and the adjustment of African American youths: A five-year longitudinal analysis with contextual moderation effects. Child Development, 77(5), 1170–1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant-Davis T (2007). Healing requires recognition: The case for race-based traumatic stress. The Counseling Psychologist, 35(1), 135–143. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant-Davis T, & Ocampo C (2006). A therapeutic approach to the treatment of racist-incident-based trauma. Journal of Emotional Abuse, 6(4), 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Buka SL, Stichick TL, Birdthistle I, & Earls FJ (2001). Youth exposure to violence: Prevalence, risks, and consequences. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 71(3), 298–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter RT (2007). Racism and psychological and emotional injury: Recognizing and assessing race-based traumatic stress. The Counseling Psychologist, 35(1), 13–105. [Google Scholar]

- Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. (2014). Trauma-informed care in behavioral health services. Chapter 3 Understanding the impact of trauma. Rockville, Maryland. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman PL, & Mullis RL (2000). Racial differences in adolescent coping and self-esteem. The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 161(2), 152–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark KB, & Clark MP (1950). Emotional factors in racial identification and preference in Negro children. Journal of Negro Education, 19(3), 341–350. [Google Scholar]

- Cloitre M, Stolbach BC, Herman JL, Kolk BVD, Pynoos R, Wang J, et al. (2009). A developmental approach to complex PTSD: Childhood and adult cumulative trauma as predictors of symptom complexity. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 22(5), 399–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coard SI, Wallace SA, Stevenson HC, & Brotman LM (2004). Towards culturally relevant preventive interventions: The consideration of racial socialization in parent training with African American families. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 13(3), 277–293. [Google Scholar]

- Coll CG, & Pachter LM (2002). Ethnic and minority parenting. Handbook of Parenting: Social Conditions and Applied Parenting, 4(2), 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Comas-Díaz L (2016). Racial trauma recovery: A race-informed therapeutic approach to racial wounds. In Alvarez AN, Liang CTH, & Neville HA (Eds.), The cost of racism for people of color: Contextualizing experiences of discrimination. Cultural, racial, and ethnic psychology book series (pp. 249–272). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Comas-Díaz L, Hall GN, & Neville HA (2019). Racial trauma: Theory, research, and healing: Introduction to the special issue. American Psychologist, 74(1), 1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook A, Blaustein M, Spinazzola J, & Van der Kolk B (2003). Complex trauma in children and adolescents. White paper from the National Child Traumatic Stress Network Complex Trauma Task Force. Los Angeles, CA: National Center for Child Traumatic Stress. Retrieved December 2018, from National Child Traumatic Stress Network website. [Google Scholar]

- Cook A, Spinazzola J, Ford J, Lanktree C, Blaustein M, Cloitre M, et al. (2017). Complex trauma in children and adolescents. Psychiatric Annals, 35(5), 390–398. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper CR, García Coll CT, Bartko WT, Davis H, & Chatman C (2005). Developmental pathways through middle childhood: Rethinking contexts and diversity as resources. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Copeland EP, & Hess RS (1995). Differences in young adolescents’ coping strategies based on gender and ethnicity. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 15(2), 203–219. [Google Scholar]

- Copeland WE, Keeler G, Angold A, & Costello EJ (2007). Traumatic events and posttraumatic stress in childhood. Archives of General Psychiatry, 64(5), 577–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello EJ, Erkanli A, Fairbank JA, & Angold A (2002). The prevalence of potentially traumatic events in childhood and adolescence. Journal of Trauma Stress, 15(2), 99–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danieli Y (Ed.). (1998). International handbook of multigenerational legacies of trauma. New York: Springer Science & Business Media. [Google Scholar]

- Degruy-Leary J (1994). Post-traumatic Slave Syndrome: America’s Legacy of Enduring Injury. Caban Productions. [Google Scholar]

- Dreby J (2015). U.S. immigration policy and family separation: The consequences for children’s well-being. Social Science & Medicine, 132, 245–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglass S, Mirpuri S, English D, & Yip T (2016). “They were just making jokes”: Ethnic/racial teasing and discrimination among adolescents. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 22(1), 69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans-Campbell T (2008). Historical trauma in American Indian/Native Alaska communities: A multilevel framework for exploring impacts on individuals, families, and communities. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 23(3), 316–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher CB, Wallace SA, & Fenton RE (2000). Discrimination distress during adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 29(6), 679–695. [Google Scholar]

- Flores E, Tschann JM, Dimas JM, Pasch LA, & de Groat CL (2010). Perceived racial/ethnic discrimination, posttraumatic stress symptoms, and health risk behaviors among Mexican American adolescents. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 57(3), 264–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin AJ, Boyd-Franklin N, & Kelly S (2006). Racism and invisibility: Race-related stress, emotional abuse and psychological trauma for people of color. Journal of Emotional Abuse, 6(2–3), 9–30. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman MA (2013). The harmful psychological effects of the Washington football mascot. Oneida Indian Nation. Retrieved December 2018, from http://www.changethemascot.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/DrFriedmanReport.pd. [Google Scholar]

- Geronimus AT (1996). Black/white differences in the relationship of maternal age to birthweight: A population-based test of the weathering hypothesis. Social Science and Medicine, 42(4), 589–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons FX, Gerrard M, Cleveland MJ, Wills TA, & Brody G (2004). Perceived discrimination and substance use in African American parents and their children: A panel study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 86(4), 517–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilliam WS, Maupin AN, Reyes CR, Accavitti A, & Shic F (2016). Do early educators’ implicit biases regarding sex and race relate to behavior expectations and recommendations of preschool expulsions and suspensions?. New Haven, CT: Research Study Brief, Yale University, Yale Child Study Center. [Google Scholar]

- Giscombé CL, & Lobel M (2005). Explaining disproportionately high rates of adverse birth outcomes among African Americans: The impact of stress, racism, and related factors in pregnancy. Psychological Bulletin, 131(5), 662–683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goff PA, Jackson MC, Leone D, Lewis BA, Culotta CM, & DiTomasso NA (2014). The essence of innocence: Consequences of dehumanizing Black children. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 106(4), 526–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gone JP, Hartmann WE, Pomerville A, Wendt DC, Klem SH, & Burrage RL (2019). The impact of historical trauma on health outcomes for indigenous populations in the USA and Canada: A systematic review. American Psychologist, 74(1), 20–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green BL, Korol M, Grace MC, Vary MG, Leonard AC, Gleser GC, et al. (1991). Children and disaster: Age, gender, and parental effects on PTSD symptoms. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 30(6), 945–951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwald R (2014). Child trauma handbook: A guide for helping trauma-exposed children and adolescents. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Greeson JK, Briggs EC, Kisiel CL, Layne CM, Ake GS III, Ko SJ, et al. (2011). Complex trauma and mental health in children and adolescents placed in foster care: Findings from the National Child Traumatic Stress Network. Child Welfare, 90(6), 91–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamblen J (2001). PTSD in children and adolescents, a National Center for PTSD fact sheet. Washington, DC: National Center for PTSD. [Google Scholar]

- Hatch SL, & Dohrenwend BP (2007). Distribution of traumatic and other stressful life events by race/ethnicity, gender, SES and age: A review of the research. American Journal of Community Psychology, 40(3–4), 313–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heard-Garris NJ, Cale M, Camaj L, Hamati MC, & Dominguez TP (2018a). Transmitting trauma: A systematic review of vicarious racism and child health. Social Science and Medicine, 199, 230–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heard-Garris NJ, Williams DR, & Davis M (2018b). Structuring research to address discrimination as a factor in child and adolescent health. JAMA Pediatrics, 172(10), 910–912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heart MYHB (1999). Oyate Ptayela: Rebuilding the Lakota Nation through addressing historical trauma among Lakota parents. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 2(1–2), 109–126. [Google Scholar]

- Helms JE, Jernigan M, & Mascher J (2005). The meaning of race in psychology and how to change it: A methodological perspective. American Psychologist, 60(1), 27–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helms JE, Nicolas G, & Green CE (2012). Racism and ethnoviolence as trauma: Enhancing professional and research training. Traumatology, 18(1), 65–74. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes SC, Facemire VC, & DaFonseca AM (2016). Expanding criterion A for posttraumatic stress disorder: Considering the deleterious impact of oppression. Traumatology, 22(4), 314–321. [Google Scholar]

- Hope EC, & Jagers RJ (2014). The role of sociopolitical attitudes and civic education in the civic engagement of black youth. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 24(3), 460–470. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, & Chen L (1999). The nature of parents’ race-related communications to children: A developmental perspective. In Balter L, Tamis-LeMonda CS, Balter L, & Tamis-LeMonda CS (Eds.), Child psychology: A handbook of contemporary issues (pp. 467–490). Philadelphia, PA: Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, Rodriguez J, Smith EP, Johnson DJ, Stevenson HC, & Spicer P (2006). Parents’ ethnic-racial socialization practices: A review of research and directions for future study. Developmental Psychology, 42(5), 747–770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussey JM, Chang JJ, & Kotch JB (2006). Child maltreatment in the United States: prevalence, risk factors, and adolescent health consequences. Pediatrics, 118(3), 933–942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huynh VW (2012). Ethnic microaggressions and the depressive and somatic symptoms of Latino and Asian American adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 41(7), 831–846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaycox LH, Stein BD, Kataoka SH, Wong M, Fink A, Escudero P, et al. (2002). Violence exposure, posttraumatic stress disorder, and depressive symptoms among recent immigrant schoolchildren. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 41(9), 1104–1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jernigan MM, & Daniel JH (2011). Racial trauma in the lives of Black children and adolescents: Challenges and clinical implications. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma, 4(2), 123–141. [Google Scholar]

- Jones SC, & Neblett EW (2016). Racial-ethnic protective factors and mechanisms in psychosocial prevention and intervention programs for Black youth. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 19(2), 134–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaholokula JKA (2016). Racism and physical health disparities. In Alvarez AN, Liang CTH, & Neville HA (Eds.), The cost of racism for people of color: Contextualizing experiences of discrimination (pp. 163–188). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, Hughes M, & Nelson CB (1995). Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry, 52(12), 1048–1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kira IA (2010). Etiology and treatment of post-cumulative traumatic stress disorders in different cultures. Traumatology, 16(4), 128–141. 10.1177/1534765610365914. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krayer A, Ingledew DK, & Iphofen R (2007). Social comparison and body image in adolescence: A grounded theory approach. Health Education Research, 23(5), 892–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen SE, & Fitzgerald LF (2011). PTSD symptoms and sexual harassment: The role of attributions and perceived control. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 26(13), 2555–2567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaVeist TA (1994). Beyond dummy variables and sample selection: What health services researchers ought to know about race as a variable. Health Services Research, 29(1), 1–16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis ML, McConnico N, & Anderson RE (2018). Making meaning from trauma and violence: The influence of culture, traditional beliefs, and historical trauma. In Osofsky JD & Groves BM (Eds.), Violence and trauma in the lives of children (Vol. 2, pp. 7–23). Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger. [Google Scholar]

- Liu S, Quinn PC, Wheeler A, Xiao N, Ge L, & Lee K (2011). Similarity and difference in the processing of same-and other-race faces as revealed by eye tracking in 4-to 9-month-olds. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 108(1), 180–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAdoo HP (2002). Black children: Social, educational, and parental environments. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Minuchin P (1985). Families and individual development: Provocations from the field of family therapy. Child Development, 56, 289–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadal KL, Griffin KE, Wong Y, Hamit S, & Rasmus M (2014). The impact of racial microaggressions on mental health: Counseling implications for clients of color. Journal of Counseling & Development, 92(1), 57–66. [Google Scholar]

- Naeem F, Taj R, Khan A, & Ayub M (2012). Can watching traumatic events on TV cause PTSD symptoms? Evidence from Pakistan. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 126(1), 79–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Child Traumatic Stress Network. (2008). Psychological and behavioral impact of trauma: Middle school students. Child trauma toolkit for educators. Los Angeles, CA, and Durham, NC: National Center for Child Traumatic Stress. [Google Scholar]

- National Child Traumatic Stress Network, Justice Consortium, Schools Committee, and Culture Consortium. (2017). Addressing race and trauma in the classroom: A resource for educators. Los Angeles, CA, and Durham, NC: National Center for Child Traumatic Stress. [Google Scholar]

- O’Keefe VM, Wingate LR, Cole AB, Hollingsworth DW, & Tucker RP (2015). Seemingly harmless racial communications are not so harmless: Racial microaggressions lead to suicidal ideation by way of depression symptoms. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 45(5), 567–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Keeffe GS, & Clarke-Pearson K (2011). Clinical report-the impact of social media on children, adolescents, and families. Pediatrics, 127, 800–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen J, Tao KW, Imel ZE, Wampold BE, & Rodolfa E (2014). Addressing racial and ethnic microaggressions in therapy. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 45(4), 283–290. [Google Scholar]

- Pachter LM, & Coll CG (2009). Racism and child health: A review of the literature and future directions. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 30(3), 255–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmieri PA, & Fitzgerald LF (2005). Confirmatory factor analysis of posttraumatic stress symptoms in sexually harassed women. Journal of Traumatic Stress: Official Publication of The International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies, 18(6), 657–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piaget J, Parsons A, & Milgram S (1958). The growth of logical thinking from childhood to adolescence. New York: Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pieterse AL (2018). Attending to racial trauma in clinical supervision: Enhancing client and supervisee outcomes. The Clinical Supervisor, 37(1), 204–220. [Google Scholar]

- Pinderhughes E (1989). Understanding race, ethnicity, and power: The key to efficacy in clinical practice. New York: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pine DS, & Cohen JA (2002). Trauma in children and adolescents: Risk and treatment of psychiatric sequelae. Biological Psychiatry, 51(7), 519–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitner RO, Astor RA, Benbenishty R, Haj-Yahia MM, & Zeira A (2003). The effects of group stereotypes on adolescents’ reasoning about peer retribution. Child Development, 74(2), 413–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plomin R (2018). Blueprint: How DNA makes us who we are. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pole N, Gone JP, & Kulkarni M (2008). Posttraumatic stress disorder among ethnoracial minorities in the United States. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 15(1), 35–61. [Google Scholar]

- Priest N, Paradies Y, Trenerry B, Truong M, Karlsen S, & Kelly Y (2013). A systematic review of studies examining the relationship between reported racism and health and wellbeing for children and young people. Social Science and Medicine, 95, 115–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin DB, Way N, & Rana M (2008). The “model minority” and their discontent: Examining peer discrimination and harassment of Chinese American immigrant youth. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 2008(121), 27–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quintana SM (2007). Racial and ethnic identity: Developmental perspectives and research. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 54(3), 259–270. [Google Scholar]

- Quintana SM, & McKown C (2008). Handbook of race, racism, and the developing child. New York: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Rickwood D, Deane FP, Wilson CJ, & Ciarrochi J (2005). Young people’s help-seeking for mental health problems. Australian e-Journal for the Advancement of Mental Health, 4(3), 218–251. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts AL, Gilman SE, Breslau J, Breslau N, & Koenen KC (2011). Race/ethnic differences in exposure to traumatic events, development of post-traumatic stress disorder, and treatment-seeking for post-traumatic stress disorder in the United States. Psychological Medicine, 41(1), 71–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero AJ, & Roberts RE (1998). Perception of discrimination and ethnocultural variables in a diverse group of adolescents. Journal of Adolescence, 21(6), 641–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saleem FT, Busby DR, & Lambert SF (2018). Neighborhood social processes as moderators between racial discrimination and depressive symptoms for African American adolescents. Journal of Community Psychology, 46(6), 747–761. [Google Scholar]

- Saleem FT, English D, Busby DR, Lambert SF, Harrison A, Stock ML, et al. (2016). The impact of African American parents’ racial discrimination experiences and perceived neighborhood cohesion on their racial socialization. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 45(7), 1338–1349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saleem FT, & Lambert SF (2015). Differential effects of racial socialization messages for personal versus institutional racial discrimination for African American adolescents. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25(5), 1385–1396. [Google Scholar]

- Salter PS, Adams G, & Perez MJ (2018). Racism in the structure of everyday worlds: A cultural-psychological perspective. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 27, 150–155. [Google Scholar]

- Sanders-Phillips K (2009). Racial discrimination: A continuum of violence exposure for children of color. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 12(2), 174–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sangrigoli S, & De Schonen S (2004). Recognition of own-race and other-race faces by three-month-old infants. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 45(7), 1219–1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheeringa MS, Peebles CD, Cook CA, & Zeanah CH (2001). Toward establishing procedural, criterion, and discriminant validity for PTSD in early childhood. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 40(1), 52–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seaton EK, Caldwell CH, Sellers RM, & Jackson JS (2008). The prevalence of perceived discrimination among African American and Caribbean Black youth. Developmental Psychology, 44(5), 1288–1297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers RM, Copeland-Linder N, Martin PP, & Lewis RLH (2006). Racial identity matters: The relationship between racial discrimination and psychological functioning in African American adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 16(2), 187–216. [Google Scholar]

- Smedley A, & Smedley BD (2005). Race as biology is fiction, racism as a social problem is real: Anthropological and historical perspectives on the social construction of race. American Psychologist, 60(1), 16–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith C, & Carlson BE (1997). Stress, coping, and resilience in children and youth. Social Service Review, 71(2), 231–256. [Google Scholar]

- Spears Brown C, & Bigler RS (2005). Children’s perceptions of discrimination: A developmental model. Child Development, 76(3), 533–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer MB, & Markstrom-Adams C (1990). Identity processes among racial and ethnic minority children in America. Child Development, 61(2), 290–310. [Google Scholar]

- Stanton-Salazar R (1997). A social capital framework for understanding the socialization of racial minority children and youths. Harvard Educational Review, 67(1), 1–41. [Google Scholar]

- Steele CM (1997). A threat in the air: How stereotypes shape intellectual identity and performance. American Psychologist, 52(6), 613–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L (1990). Interdependency in the family: Autonomy, conflict, and harmony. In Feldman S & Elliot G (Eds.), At the threshold: The developing adolescent (pp. 255–276). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L, & Morris AS (2001). Adolescent development. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 83–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L, & Silk JS (2002). Parenting adolescents. In Bornstein MH (Ed.), Handbook of parenting (Vol. 1, pp. 103–133)., Children and parenting Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA]. (2014). Trauma-informed care in behavioral health services (TIP Series 57, HHS Publication No. 13–4801). Retrieved October 2018, from https://store.samhsa.gov/product/TIP-57-Trauma-Informed-Care-in-Behavioral-Health-Services/SMA14-4816. [PubMed]

- Sue DW, Capodilupo CM, Torino GC, Bucceri JM, Holder AM, Nadal KL, et al. (2007). Racial microaggressions in everyday life: Implications for counseling. American Psychologist, 62(4), 271–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sue DW, Rivera DP, Capodilupo CM, Lin AI, & Torino GC (2010). Racial dialogues and White trainee fears: Implications for education and training. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 16(2), 206–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svetaz MV, Chulani V, West KJ, Voss R, Kelley MA, Raymond-Flesch M, et al. (2018). Racism and its harmful effects on nondominant racial-ethnic youth and youth-serving providers: A call to action for organizational change: The society for adolescent health and medicine. Journal of Adolescent Health, 63(2), 257–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel H, & Turner JC (1986). The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In Worchel S & Austin WG (Eds.), Psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 7–24). Chicago: Nelson-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas AJ, & Blackmon SKM (2015). The influence of the Trayvon Martin shooting on racial socialization practices of African American parents. Journal of Black Psychology, 41(1), 75–89. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson T, & Massat CR (2005). Experiences of violence, posttraumatic stress, academic achievement and behavior problems of urban African-American children. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 22(5–6), 367–393. [Google Scholar]

- Three ZT (2005). Diagnostic classification of mental health and developmental disorders of infancy and early childhood. Washington, DC: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Tynes BM, Hiss S, Ryan AM, & Rose CA (2015). In-school versus online discrimination: Effects on mental health and motivation among diverse adolescents in the United States. In Routledge International Handbook of Social Psychology of the Classroom (pp. 140–149). Routledge. [Google Scholar]