Abstract

Introduction

Measurement for improvement is the process of collecting, analysing and presenting data to demonstrate whether a change has resulted in an improvement. It is also important in demonstrating sustainability of improvements through continuous measurement. This makes measurement for improvement a core element in quality improvement (QI) efforts. However, there is little to no research investigating factors that influence measurement for improvement skills in healthcare staff. This protocol paper presents an integrated evaluation framework to understand the training, curricular and contextual factors that influence the success of measurement for improvement training by using the experiences of trainees, trainers, programme and site coordinators.

Methods and analysis

This research will adopt a qualitative retrospective case study design based on constructivist-pragmatic philosophy. The Pressure Ulcers to Zero collaborative and the Clinical Microsystems collaborative from the Irish health system which included a measurement for improvement component have been selected for this study. This paper presents an integrated approach proposing a novel application of two pre-existing frameworks: the Model for Understanding Success in Quality framework and the Kirkpatrick Evaluation Model to evaluate an unexplored QI context and programme. A thematic analysis of the qualitative interview data and the documents collected will be conducted. The thematic analysis is based on a four-step coding framework adapted for this research study. The coding process will be conducted using NVivo V.12 software and Microsoft Excel. A cross-case comparison between the two cases will be performed.

Ethics and dissemination

The study has received an exemption from full ethical review from the Human Research Ethics Committee of University College Dublin, Ireland (LS-E-19-108). Informed consent will be obtained from all participants and the data will be anonymised and stored securely. The results of the study will be disseminated in peer-reviewed journals.

Keywords: quality in health care, education & training (see medical education & training), qualitative research

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The proposed evaluation framework focuses on the long-term sustainability of measurement for improvement skills in healthcare staff.

The proposed framework is based on the current evidence and models used by various quality improvement (QI) studies and accounts for the contextual realities of the healthcare system.

The study addresses current gaps in the methods and application of evaluation frameworks and models in QI evaluation.

The study design is responsive to the current situation and explores the role of QI education and measurement for improvement in adapting to new ways of working during COVID-19.

The major limitation of this study is recall bias as the training programmes being evaluated were completed more than 2 years ago.

Introduction

Quality in healthcare is a subjective, complex and multidimensional concept which makes it difficult to define and measure.1 The common defining attributes of healthcare quality in research include the delivery of effective and safe care to attain desired outcomes and a culture of excellence.2 In his pioneering work on healthcare quality, Donabedian described high-quality healthcare as the type of care which maximises patient welfare while accounting for the expected gains and losses using legitimate means.3 Since then, the understanding of quality has greatly evolved. The Health Foundation defines healthcare quality as the ability of healthcare services to deliver the desired health outcomes consistent with recent professional knowledge to individuals and populations.4 Similarly, there are various definitions of quality improvement (QI). One simple way to define QI is considering it an approach for improving health service systems and processes through the routine use of health and programme data to meet patient and programme needs.5 These definitions of quality and QI reveal the central role of measurement for improvement (MFI) in the improvement process. MFI refers to the process of collecting, analysing and presenting quantitative and qualitative data to demonstrate whether a change has resulted in an improvement.6 Despite its importance, MFI is a less explored topic in QI research and there is a need for further research in the area. With the growing importance of QI knowledge in healthcare, there is a developing research interest in the QI curricula content, the effectiveness of educational design and its link with organisational performance.7 However, most QI programme evaluations focus on the improvement of knowledge, skills and confidence of learners and do not offer insights into clinical and long-term effects.8 Additionally, the MFI component is rarely evaluated.

Existing models of training programme evaluation often have a narrow focus; they are effective in measuring the outputs (what works) but do not provide insights into the process that leads to training effectiveness (how it works).9 10 This highlights the need for evaluation approaches that explore the processes that led to improvements. The impact of contextual factors such as environment, management support and leadership, organisational culture and data infrastructure also remains largely unexplored.11 There is also ambiguity around the quality and effectiveness of the programmes and how the concepts and methods are taught.12 One crucial aspect of improvement work is measurement. Measurement is an important element in QI efforts as change needs to be measured to demonstrate improvement and to identify and respond to variation.13 Learning how to measure quality is an important skill for healthcare staff in general and for those involved in QI in particular.

A systematic literature review revealed that there are no QI programme evaluation studies focusing on evaluating the factors that influence the development and use of MFI skills of healthcare staff.14 There is a need to evaluate the effectiveness, sustainability and spread of MFI programmes but there is uncertainty around evaluation outcomes and methods. Measurement often gets overshadowed by the overall focus on understanding QI and on outcomes, resulting in a dearth of MFI research. Quality measurement is frequently treated as an ancillary matter in healthcare systems’ approach to QI.15 Research to explore factors that will enable healthcare staff to embrace MFI and appreciate its value in demonstrating outcomes is needed. In addition to this, many QI teams are failing to fully implement measurement tools and techniques.16 Despite this identified gap in measurement skills, there is little to no research exploring ways to develop MFI skills in staff or to better understand the factors that influence the development of these skills.

The overall aim of this research is to understand the training, curricular and contextual factors that inhibit or enable the success of MFI training by using the experiences of trainees, trainers, programme and site coordinators. The research will be conducted in the Irish health system using two QI collaboratives (Pressure Ulcers to Zero (PUTZ) and Clinical Microsystems) which included dedicated training on MFI. This paper presents an integrated evaluation framework developed to address this research aim. This research started in August 2020 and is expected to be completed by December 2021.

Methods

Theoretical underpinning

The underlying assumption of this research is that the views of stakeholders about the training programme and the context are required to make sense of this problem. This aligns with the constructivist worldview. The constructivist worldview asserts that humans construct meaning when they interact with the world and are influenced by historical and social perspectives and context.17 Another objective of this research is to investigate what works in a certain situation and why and then use this knowledge to develop solutions, linking the research outcomes to recommended actions which is a characteristic of the pragmatist worldview. The pragmatist worldview believes in the presence of multiple forms of reality and that theories are extracted from actions and then applied back in practice through an iterative process.18 This research thus contains elements from pragmatist and constructivist viewpoints.

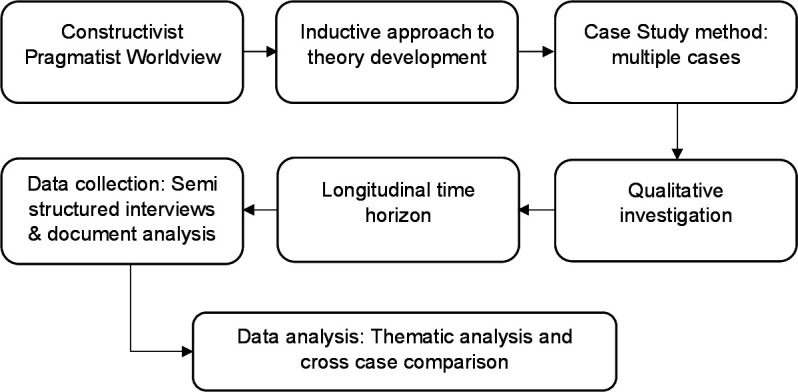

This exploratory study uses an inductive approach to understand the research problem of MFI programme effectiveness, sustainability, spread and evaluation methods.19 The pragmatic constructivist approach asserts that reality is constructed socially and experientially and propagates the use of inductive reasoning which aligns most closely with this research.20 This research explores complex contextual and human factors in a real-world healthcare setting making it suitable for a qualitative inquiry.21 This research aim requires a design that can capture the complexity of the healthcare system, the factors that impact programme development, implementation and evaluation and provide evidence for policy action. A case study design can capture the complexity of individual behaviour in institutional settings, factors that influence these, inter-relationship of actions and consequences, perceptions about programme goals from the perspective of those who designed it and those who implemented it to provide an evidence base for decision-making and explain success or failure.22 Thus, a case study design will be adopted to capture the information required to adequately address this research question.

Case study methodology is a bridge between research paradigms and offers flexibility in epistemology, ontology and methodology by providing a well-defined boundary and structure within which appropriate methods can be applied.23 The aim of this study is to gain an in-depth understanding of the factors that influence MFI skill development and use in the real-world context which makes case study research a suitable choice.24 Figure 1 summarises the research design choices in this research through an adaptation of Saunders research onion.19

Figure 1.

Flow chart of research design choices for the study through an adaptation of Saunders research onion.

Framework development process

Programme evaluation should not be considered just a set of techniques but used as an integrated approach which is intricately linked with needs assessment, course design, course presentation and transfer of training.25 It may be argued that considering these programme evaluation elements may add to strength of a study. Additionally, programme evaluation often gets neglected, with attention being narrowly focused on programme development and implementation.26 This protocol aims to avoid these common pitfalls and limitations and presents an evaluation framework which integrates these elements.

Research suggests that instead of focusing on the development of a standardised appraisal tool for quality measurement, evaluation should be guided by the purpose.27 This research aims to retrospectively understand which curricular, training and contextual factors inhibit or enable the effectiveness, sustainability and spread of the MFI training using a customised framework. Medical educators can select from various individual programme evaluation models or use a combination to develop a framework appropriate to answer their evaluation questions.28 This research draws on two evaluation models to develop a tool suitable for this case study: the Kirkpatrick Evaluation Model29 and the Model for Understanding Success in Quality (MUSIQ).30 The following sections describe the selected evaluation models and provide justification for their use.

Kirkpatrick Evaluation Model

Kirkpatrick Model measures the impact of training at four levels: reaction of participants, participant learning, change in behaviour and impact on the organisational results.29 The model employs straightforward evaluation criteria and requires measurement of a limited number of variables.31 The popularity of this model is attributed to its simplicity in outlining a system for training outcome assessment and simplifying the complex evaluation process; however, it is also criticised for being incomplete.32 The understanding about factors which impact training effectiveness has grown over the years revealing that contextual factors, individual characteristics and training design elements play a critical role in training success. However, the Kirkpatrick Model does not account for these factors.32

The model’s underlying assumptions are also a source of criticism as it assumes that each succeeding level provides more information than the previous one, each level is causally linked to the other and the correlation between the levels is positive.33 It is independent of the learner’s previous experience or learning, individual factors and other environmental and contextual factors that can impact training success.31 The Kirkpatrick Model is outcome focused and a drawback of such models is that although they provide a good understanding of what was achieved, they offer little evidence about the process through which these outputs were achieved and the related barriers and enablers. This emphasises the need to go beyond the outcome-focused Kirkpatrick Model to understand how the programme works.34 Some areas of improvement identified by previous studies in the Kirkpatrick Model include paying more attention to the teaching and learning methods31 and using all four levels of the model over a longer period, and mechanisms for exploring possible causal links among the four levels.35

Despite the criticism, the Kirkpatrick Model has remained a popular choice for evaluating learner outcomes in training programmes28 and has been used to evaluate higher education programmes, methodology workshops, professional development programmes and short-duration courses.36 This research will rely on the four levels presented by the model but will adapt it to purpose of this research and account for these criticisms through integrating the MUSIQ alongside the Kirkpatrick Model in a unified evaluation framework.

Model for Understanding Success in Quality

Context can be defined as the ‘why’ and ‘when’ of change and includes influential factors from the outer setting and internal setting.37 Factors internal to the organisation can include organisational size, teams, leadership, culture and implementation environment while external factors can include regulatory requirements, funding and professional organisations.38

The systematic literature review conducted in the exploratory phase of this research highlighted that the success of developing data skills of healthcare professional for QI is dependent on intervention design and influenced by context.14 Thus, success of a QI intervention can vary across implementation settings.39 Most studies evaluating QI programmes focus on the evaluation of the intervention and only few incorporate methods to assess the impact of contextual factors.40 The constructivist-pragmatist research problem being investigated cannot be fully addressed without incorporating context into the evaluation design.

There is an increased interest in understanding the role of context in QI initiatives and several frameworks and models have been developed to address this.41 One such model is the MUSIQ model. The model acknowledges the system as a product of individual parts and inter-relationships. It identifies 25 contextual factors and their relative influence at various levels of the healthcare system.30 The model was later revised to expand the number of contextual factors to 36. These new factors include external knowledge (general and project specific), portfolio management, specialist staff, microsystem capacity and patient engagement.30 The factors presented in this model are relevant to this research question and will be incorporated into this evaluation.

The MUSIQ model is relatively new as it was published in 2012 and has been only used by a handful of studies to date. Therefore, there is insufficient evidence to draw conclusions regarding model usefulness, though studies have confirmed the observation of all original factors in the QI initiatives being studied.42 One reported the framework and underlying assumptions useful for interrogating the research question43 and another reported that the model was useful in identifying contextual constraints.44 The Kirkpatrick Model focuses on different outcome levels while MUSIQ adds another perspective of context at healthcare system level. The MUSIQ model offers the missing link to context and relationships in the Kirkpatrick Model. The evaluation framework for this research focuses on integrating the two models to address the aim of this research.

Integrated evaluation framework

Knowing what information to collect, whom to collect it from and when to collect are critical decisions in designing a comprehensive evaluation once the purpose of the evaluation has been established.45 The proposed framework presented in table 1 combines evaluation perspectives from the two models and will be used to guide data collection through semistructured qualitative interviews and document analysis. A draft interview guide for collaborative trainees based on the evaluation framework can be found in online supplemental file 1.

Table 1.

Integrated evaluation framework

| Model components | Definitions | |

| External environment | External motivators | External factors that stimulate the organisation to focus on the QI project. |

| Project sponsorship | External entities contributing personnel, expertise, equipment, facilities or other resources for the project. | |

| Organisation | QI leadership | Senior leadership commitment to champion and support QI project. |

| Senior leader project sponsor | ||

| Culture supportive of QI | Values, beliefs and norms of an organisation that shape the behaviours of staff in pursuing QI. | |

| Maturity of organisational QI | Sophistication of the organisation’s QI programmes. | |

| Staff engagement | Steps taken by the organisation for continued staff engagement in QI. | |

| QI support and capacity | Data infrastructure | Extent to which a system exists to collect, manage and facilitate the use of data. Effective use of technology. |

| Resource availability | Support for QI, including allocation of resources, finances and staff time. | |

| Workforce focus on QI | Workforce development through training and engagement in QI. | |

| QI team and microsystem | Team diversity | Diversity of team members with respect to professional discipline, personality, motivation and perspective. |

| Physician involvement | Contribution of physicians to the QI team efforts. | |

| Subject matter expert | Team member/members knowledgeable about measurement. | |

| Prior QI experience | Prior experience with QI. | |

| Team leadership | Team leader’s ability to accomplish the goals of the improvement project by guiding the QI team. | |

| Team norms | Team establishes strong norms of behaviour about QI goal achievement. | |

| Team QI skill/capability for improvement | Team’s ability to use improvement methods to make changes. | |

| Motivation to change | Extent to which team members have a desire and willingness to improve. | |

| QI accountability | Clearly stated and communicated responsibility and accountability in the project. | |

| Trigger (training event) | Participation and reaction (Kirkpatrick level 1) | Overall satisfaction with the programme, content, delivery, logistics, facilitators, etc. |

| Knowledge, skills and attitudes (Kirkpatrick level 2) | Improvement in knowledge and skills reported by participants immediately after the intervention. | |

| Outcomes/process and system changes | Behaviour change (Kirkpatrick level 3) | Confidence in measurement skills. Maintaining and advancing the skills learnt. Continued spread and involvement in QI. |

| Learning networks | Development of QI networks among postintervention. | |

| QI capacity development | Ability of participants to initiate and lead other projects. Ability of participants to train/help other staff. |

|

| Change in organisational practice and/or patient outcomes (Kirkpatrick level 4) | Sustainability in outcomes achieved. Sustainability in practices. Process changes as a result of the training event. |

|

| Dissemination/spread | Spread of knowledge and improved practices to non-intervention units. | |

| Unintended consequences | Negative or positive unanticipated outcomes. | |

QI, quality improvement.

bmjopen-2020-047639supp001.pdf (39.1KB, pdf)

Case design

This research study will use a multiple case design.24 A multiple case design is suited for this study because MFI training occurs at a common venue where it is attended by healthcare staff from diverse backgrounds and multiple organisations. Participants then return to their own organisations to apply their learning. In Ireland, the National QI Team within the Health Service Executive (HSE) is responsible for partnering with health and social care services to promote sustainable QI. The MFI curriculum6 is one such effort to train staff in handling quantitative and qualitative data for QI. The curriculum identifies and outlines the essential components of high-quality MFI training to ensure a consistent standard of training for the Irish Healthcare staff.6 The purpose of this research is to apply the integrated framework to evaluate the MFI curriculum.

Case selection

The bounded systems are the training collaboratives in which the training was imparted. The trainees belonged to different organisations who came together for the training and then implemented the skills in their own organisational contexts. This research design therefore consists of two cases: the PUTZ collaborative and the Clinical Microsystems collaborative, which delivered MFI training. The PUTZ collaborative took place between 2016 and 2018. The aim of the collaborative was to reduce ward-acquired pressure ulcers by 50% in participating teams within 6 months and sustain the achieved results at 12 months.46 The microsystems collaborative occurred in 2017 and its aim was to improve the quality of patient care and work life of the emergency department staff participating in the collaborative.47 Both collaboratives consisted of three training days and activity periods in between, with MFI being an important component of the training content.

Researcher reflexivity statement

The lead researcher immersed herself in the work of the National QI Team of the HSE Ireland to develop a deeper understanding of their work, understand the context for MFI and the aims and objectives of the training programmes. This immersion and ethnographic observation provided invaluable opportunity to the researcher to observe and work on various other projects of the National QI Team. The researcher, therefore, developed an insider perspective about the operations and culture of the health system, something which facilitated a better understanding when participants described the aspects of the system such as bureaucracy. However, one possible drawback of this could be a preference for ‘trainer’ views due to the researcher’s familiarity with these individuals. To counter this, the researcher will structure the analysis into trainer and trainee perspectives so that both perspectives are included in a balanced analysis. As an additional quality step, the emerging findings will be presented to the research team to challenge assumptions and increase trustworthiness.

Patient and public involvement

There was no patient or public involvement in the study. The study collected data from healthcare staff about their experiences of participating in a QI training programme and did not require any data from patients or the public.

Data collection

Data collection will be conducted using multiple sources of evidence through semistructured interviews with training participants, trainers and site coordinators and document analysis. A case study database in the form of electronic files will be maintained for this case study research. The database will have two main sections: the evidence or data collected and reports of the investigators.24

The study population will include healthcare staff who were trained, those who delivered training, site coordinators of participating sites and leads of the two collaboratives in the HSE. The trainee population ranges from senior-level staff such as assistant directors of nursing to frontline staff such as healthcare assistants and nurses. This research will use a purposive sampling strategy by including participants who shared the common experience of the training and had participated in the two collaboratives.48 This is purposely kept broad as both collaboratives were completed more than 2 years ago as the researchers anticipate challenges in recruiting participants. Participation in the study will be on a voluntary basis and the researcher will describe the nature of the study in detail to the participants and answer all questions prior to any data collection. The National QI Team will serve as a gatekeeper for participant recruitment for trainees and send a letter to introduce the researcher to participants. The recruitment letter is available in online supplemental file 2. Those willing to participate would then contact the researcher and written informed consent will be obtained. The study consent form is available in online supplemental file 3.

bmjopen-2020-047639supp002.pdf (30.1KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2020-047639supp003.pdf (483.5KB, pdf)

The data collection will be conducted via semistructured interviews and document analysis. The semistructured interviews will be conducted by the lead author. The interview method will allow the researcher to capture the words, thoughts, feelings, perceptions and experiences of the participants to answer the research question.49 The first two interviews will be used as a pilot to review the interview guide and make changes if required. The collected documents will be used to inform participant reaction and learning (Kirkpatrick levels 1 and 2). These documents will include (depending on the availability) the end of collaborative reports and any feedback forms used during the collaboratives. Level 3 and 4 data along with contextual factors (from MUSIQ framework) will be collected through interviews. This research aims to recruit all trainers, both leads of the two collaboratives in the HSE and 10 participants from each collaborative.

Data processing

The interviews will be audio recorded, transcribed and anonymised. Site pseudonyms will be used. A field journal will be maintained by the researcher while interviewing which will be used to make a note of researcher’s assumptions, feelings and biases and reflections on the interviews. After each interview, the recording will be analysed to improve the researcher’s performance as an interviewer. A case database will be maintained to store all collected data.

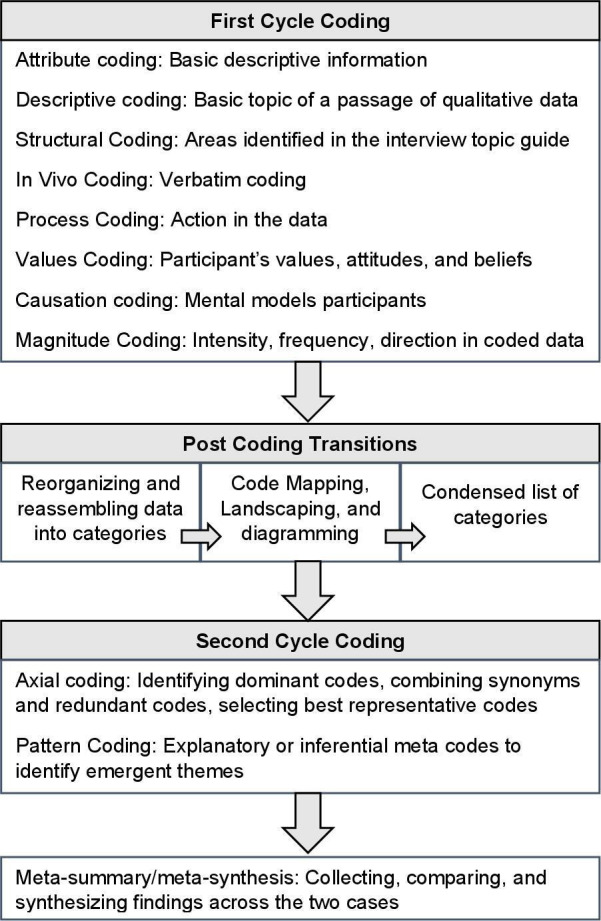

Data analysis

The data analysis of case studies involves a detailed description of the setting or individuals and analysis of the data for themes or issues.50 A detailed description of the training programme, sites and participants will be followed by a thematic analysis of the qualitative interview data and the documents collected. The coding and analysis framework is presented in figure 2.51 Coding process will be aided by the NVivo V.12 software which provides a platform for data management, querying and visualisation.52

Figure 2.

Coding and analysis framework. Description of coding and analysis steps adapted from Saldana’s coding methodology.

This qualitative analysis will rely on the same theoretical and analytical strategy to study both cases and then the patterns found in each case will be compared.24 The comparison between the two cases will be performed. This involves analysing the data in new ways, explore relationships and then cluster the data so contrasts and similarities emerge.53

Ensuring rigour

Rigour will be ensured by triangulating through multiple sources of data by including perspectives of multiple stakeholders and multiple data collection methods. Data collection and analysis methods and researcher reflexivity will be clearly documented to ensure transparency. At the analysis stage, two other researchers will review codes collectively in regular meetings.54 The researchers aim to perform member checking by contacting 10% of the participants and sharing a summary of results. The researchers also aim to perform member checking with a broader audience through an interactive webinar. The HSE regularly conducts QI webinars, and this platform would be useful for reaching healthcare professionals interested in QI and enable the researchers to obtain and incorporate feedback from a wider audience into the results. The other method of dissemination would be through peer-reviewed journal articles which would strengthen the awareness about this study. To incorporate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on this research process and the work practices of healthcare staff, questions to explore the role of QI education and MFI in adapting to new ways of working are included in the interview topic guide.

Discussion

MFI is an essential skill for healthcare staff as it can be used to monitor and support improvement and enhance the quality of care.55 This research aims to explore training, curricular and contextual factors that can help in the development and use of MFI skills in healthcare staff. To our knowledge, no previous studies have evaluated MFI programmes. Additionally, many QI programmes are not appropriately evaluated, peer reviewed or published,56 therefore it is difficult to access any work on MFI skills that may have been conducted before.

Theoretically, this research will contribute towards the current understanding of the two models. It will add to the evidence base of MUSIQ model and confirm the existence or non-existence of the contextual factors and relationships presented in the model. The study uses MUSIQ model in a qualitative design while majority of the previous studies have relied on quantitative approaches. It will study all four levels proposed in the Kirkpatrick Model which is less common in previous studies. The integrated framework is a theoretical contribution to the field and the analysis will also reflect on the useful and effectiveness of the approach.

Although qualitative research may not be generalisable, this research will be one of the few studies focusing on MFI and will reveal a multitude of avenues for future research. The results will be of importance for QI/measurement training design and for evaluation purposes and healthcare organisations and systems. There is a need for further research in the evaluation of QI programmes in terms of their immediate and long-term impacts. MFI is an important but less explored topic in programme evaluations and there is a need to expand the understanding of what to teach, how to teach and how to evaluate programmes that aim to train healthcare staff in quantitative and qualitative data skills. Programme evaluation should be viewed as a driving force for future programme design and policy. Instead of focusing on using standardised models, this study takes a customised evaluation approach, appropriate to answer this research question which is a theoretical contribution to the field. This approach is expected to expand the empirical and theoretical understanding of factors that influence the development and use of MFI skills in healthcare staff. Another expected impact of this research will be to deepen the understanding of contextual factors that impacted programme success at various levels of the healthcare system.

Ethics and dissemination

The study has received exemption from full ethical review from the Human Research Ethics Committee of University College Dublin, Ireland (LS-E-19-108). The results of the study will be disseminated in peer-reviewed journals.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: ZK developed the methodology and prepared the initial draft in consultation with ADB and EM. ADB and EM provided substantive feedback on the draft which was revised by ZK. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The corresponding author (ZK) receives a PhD funding from the Health Service Executive Ireland (project reference 57399). The study is also supported by the Irish Health Research Board (RL-2015-1588).

Disclaimer: The funding sources had no influence on the design of this study, analyses, interpretation of the data or decision to publish results.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

References

- 1.Mosadeghrad AM. A conceptual framework for quality of care. Mater Sociomed 2012;24:251–61. 10.5455/msm.2012.24.251-261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allen-Duck A, Robinson JC, Stewart MW. Healthcare quality: a concept analysis. Nurs Forum 2017;52:377–86. 10.1111/nuf.12207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Donabedian A. The definition of quality and approaches to its assessment. vol 1. explorations in quality assessment and monitoring. Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA: Health Administration Press, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 4.The Health Foundation . Quality improvement made simple: what everyone should know about health care quality improvement, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organisation . Operations manual for staff at primary health care centres. Geneva Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Quality Improvement Division . Measurement for improvement curriculum. Dublin, Ireland: Health Service Executive, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith F, Alexandersson P, Bergman B, et al. Fourteen years of quality improvement education in healthcare: a utilisation-focused evaluation using concept mapping. BMJ Open Qual 2019;8:e000795. 10.1136/bmjoq-2019-000795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O'Leary KJ, Fant AL, Thurk J, et al. Immediate and long-term effects of a team-based quality improvement training programme. BMJ Qual Saf 2019;28:366–73. 10.1136/bmjqs-2018-007894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sitzmann T, Weinhardt JM. Training engagement theory: a multilevel perspective on the effectiveness of work-related training. J Manage 2018;44:732–56. 10.1177/0149206315574596 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bates P, Mendel P, Robert G. Organizing for quality: the improvement journeys of leading hospitals in Europe and the United States. Abingdon, UK: Radcliffe Publishing, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Silver SA, McQuillan R, Harel Z, et al. How to sustain change and support continuous quality improvement. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2016;11:916–24. 10.2215/CJN.11501015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.The Health Foundation . Quality improvement training for healthcare professionals. Evidence scan. United Kingdom: The Health Foundation, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Varkey P, Reller MK, Resar RK. Basics of quality improvement in health care. Mayo Clin Proc 2007;82:735–9. 10.1016/S0025-6196(11)61194-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khurshid Z, De Brún A, Martin J, et al. A systematic review and narrative synthesis: determinants of the effectiveness and sustainability of Measurement-Focused quality improvement Trainings. J Contin Educ Health Prof 2021;41:210-220. 10.1097/CEH.0000000000000331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Austin JM, Kachalia A. The state of health care quality measurement in the era of COVID-19: the importance of doing better. JAMA 2020;324:333–4. 10.1001/jama.2020.11461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dixon-Woods M, McNicol S, Martin G. Ten challenges in improving quality in healthcare: lessons from the health Foundation's programme evaluations and relevant literature. BMJ Qual Saf 2012;21:876–84. 10.1136/bmjqs-2011-000760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crotty M. The foundations of social research: meaning and perspective in the research process. Thousands Oaks California: Sage Publications, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Christ TW. The worldview matrix as a strategy when designing mixed methods research. Int J Mult Res Approaches 2013;7:110–8. 10.5172/mra.2013.7.1.110 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saunders M, Lewis P, Thornhill A. Research methods for business students. 7th ed. Harlow: Pearson Education Limited, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Merriam SB. Qualitative research and case study applications in education. 2nd ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anderson C. Presenting and evaluating qualitative research. Am J Pharm Educ 2010;74:141–41. 10.5688/aj7408141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Simons H. Case study research in practice. London;Los Angeles: SAGE, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Luck L, Jackson D, Usher K. Case study: a bridge across the paradigms. Nurs Inq 2006;13:103–9. 10.1111/j.1440-1800.2006.00309.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yin RK. Case study research: design and methods. Third ed: SAGE Publications, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marguerite F. Evaluation of training and development programs: a review of the literature. Australas J Educ Technol 1989;5. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cook DA. Twelve tips for evaluating educational programs. Med Teach 2010;32:296–301. 10.3109/01421590903480121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yardley S, Dornan T. Kirkpatrick's levels and education 'evidence'. Med Educ 2012;46:97–106. 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2011.04076.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Frye AW, Hemmer PA. Program evaluation models and related theories: AMEE guide No. 67. Med Teach 2012;34:e288–99. 10.3109/0142159X.2012.668637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kirkpatrick DL. Techniques for evaluation training programs. Journal of the American Society of Training Directors 1959;13:21–6. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kaplan HC, Provost LP, Froehle CM, et al. The model for understanding success in quality (MUSIQ): building a theory of context in healthcare quality improvement. BMJ Qual Saf 2012;21:13–20. 10.1136/bmjqs-2011-000010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heydari MR, Taghva F, Amini M, et al. Using Kirkpatrick's model to measure the effect of a new teaching and learning methods workshop for health care staff. BMC Res Notes 2019;12:388. 10.1186/s13104-019-4421-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bates R. A critical analysis of evaluation practice: the Kirkpatrick model and the principle of beneficence. Eval Program Plann 2004;27:341–7. 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2004.04.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alliger GM, Janak EA. Kirkpatrick’S levels of training criteria: thirty years later. Pers Psychol 1989;42:331–42. 10.1111/j.1744-6570.1989.tb00661.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Parker K, Burrows G, Nash H, et al. Going beyond Kirkpatrick in evaluating a clinician scientist program: it's not "if it works" but "how it works". Acad Med 2011;86:1389–96. 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31823053f3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reio TG, Rocco TS, Smith DH, et al. A Critique of Kirkpatrick’s Evaluation Model. New Horiz Adult Educ Hum Res Develop 2017;29:35–53. 10.1002/nha3.20178 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moldovan L. Training outcome evaluation model. Procedia Technology 2016;22:1184–90. 10.1016/j.protcy.2016.01.166 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pettigrew A, Ferlie E, McKee L. Shaping strategic change ‐ the case of the NHS in the 1980s. Public Money & Management 1992;12:27–31. 10.1080/09540969209387719 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wiig S, Aase K, Johannessen T, et al. How to deal with context? A context-mapping tool for quality and safety in nursing homes and homecare (SAFE-LEAD context). BMC Res Notes 2019;12:259. 10.1186/s13104-019-4291-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hovlid E, Bukve O. A qualitative study of contextual factors' impact on measures to reduce surgery cancellations. BMC Health Serv Res 2014;14:215. 10.1186/1472-6963-14-215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Øvretveit JC, Shekelle PG, Dy SM, et al. How does context affect interventions to improve patient safety? an assessment of evidence from studies of five patient safety practices and proposals for research. BMJ Qual Saf 2011;20:604–10. 10.1136/bmjqs.2010.047035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Coles E, Wells M, Maxwell M, et al. The influence of contextual factors on healthcare quality improvement initiatives: what works, for whom and in what setting? protocol for a realist review. Syst Rev 2017;6:168. 10.1186/s13643-017-0566-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reed JE, Kaplan HC, Ismail SA. A new typology for understanding context: qualitative exploration of the model for understanding success in quality (MUSIQ). BMC Health Serv Res 2018;18:584. 10.1186/s12913-018-3348-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Griffin A, McKeown A, Viney R, et al. Revalidation and quality assurance: the application of the MUSIQ framework in independent verification visits to healthcare organisations. BMJ Open 2017;7:e014121. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Eboreime EA, Nxumalo N, Ramaswamy R, et al. Strengthening decentralized primary healthcare planning in Nigeria using a quality improvement model: how contexts and actors affect implementation. Health Policy Plan 2018;33:715–28. 10.1093/heapol/czy042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dahiya S, Jha A. Review of training evaluation. Int J Comput Commun 2011;2:11–16. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Murphy L, Browne M, Branagan O. Final report: pressure ulcers to zero collaborative: health service executive, Ireland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Toland LA, Naddy B, Crowley P. Clinical Microsysytems in the emergency department. Int J Integr Care 2017;17:547. 10.5334/ijic.3867 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Newell R, Burnard P. Research for evidence-based practice in healthcare. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Holloway I. Qualitative research in health care. Open University Press, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stake R. The art of case study research. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Saldana J. The coding manual for qualitative researchers. 3rd ed. Los Angeles: SAGE, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 52.NVivo qualitative data analysis software [program]. Version 12 version 2018.

- 53.Miles MB, Huberman M. Qualitative data analysis: an expanded source-book. 338. 2 edn. Thousand Oaks California: Sage Publications, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mays N, Pope C. Assessing quality in qualitative research. BMJ 2000;320:50–2. 10.1136/bmj.320.7226.50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shah A. Using data for improvement. BMJ 2019;364:l189. 10.1136/bmj.l189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jones EL, Dixon-Woods M, Martin GP. Why is reporting quality improvement so hard? A qualitative study in perioperative care. BMJ Open 2019;9:e030269. 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2020-047639supp001.pdf (39.1KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2020-047639supp002.pdf (30.1KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2020-047639supp003.pdf (483.5KB, pdf)