Abstract

Background

The choice of approach to the laparoscopic repair of inguinal hernia is controversial. There is a scarcity of data comparing the laparoscopic transabdominal preperitoneal (TAPP) approach with the laparoscopic totally extraperitoneal (TEP) approach and questions remain about their relative merits and risks.

Objectives

To compare the clinical effectiveness and relative efficiency of laparoscopic TAPP and laparoscopic TEP for inguinal hernia repair.

Search methods

We searched Medline Extra, Embase, Biosis, Science Citation Index, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Journals@ Ovid Full Text and the electronic version of the journal, Surgical Endscopy. Recent conference proceedings by the following organisations were hand searched: Association of Endoscopic Surgeons of Great Britain & Ireland; International Congress of the European Association for Endoscopic Surgery; Scientific Session of the Society of American Gastrointestinal & Endoscopic Surgeons (SAGES); and the Italian Society of Endoscopic Surgery. In addition, specialists involved in research on the repair of inguinal hernia were contacted to ask for information about any further completed and ongoing trials, relevant websites were searched and reference lists of the all included studies were checked for additional reports.

Selection criteria

All published and unpublished randomised controlled trials and quasi‐randomised controlled trials comparing laparoscopic TAPP with laparoscopic TEP for inguinal hernia repair were eligible for inclusion. Non‐randomised prospective studies were also eligible for inclusion to provide further comparative evidence of complications and adverse events.

Data collection and analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the fixed effects model and the results expressed as relative risk (RR) for dichotomous outcomes and weighted mean difference (WMD) for continuous outcomes with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Main results

The search identified one RCT which reported no statistical difference between TAPP and TEP when considering duration of operation, haemotoma, length of stay, time to return to usual activity and recurrence. The eight non‐randomised studies suggest that TAPP is associated with higher rates of port‐site hernias and visceral injuries whilst there appear to be more conversions with TEP. Vascular injuries and deep/mesh infections were rare and there was no obvious difference between the groups. No studies reporting economic evidence were identified. Very limited data were available on learning effects but these data suggest that operators become experienced at between 30 and 100 procedures.

Authors' conclusions

There is insufficient data to allow conclusions to be drawn about the relative effectiveness of TEP compared with TAPP. Efforts should be made to start and complete adequately powered RCTs, which compare the different methods of laparoscopic repair.

Plain language summary

Two different laparoscopic techniques for repairing a hernia in the groin

An inguinal hernia is a weakness in the wall of the abdominal cavity that is large enough to allow escape of soft body tissue or internal organ, especially a part of the intestine. It usually appears as a lump and for some peoples can cause pain and discomfort, limit daily activities and the ability to work. If the bowel strangulates or becomes obstructed it can be life‐threatening. A hernia is repaired generally using a synthetic mesh either with open surgery or increasingly using less invasive laparoscopic procedures. The most common laparoscopic techniques for inguinal hernia repair are transabdominal preperitoneal (TAPP) repair and totally extraperitoneal (TEP) repair. In TAPP the surgeon goes into the peritoneal cavity and places a mesh through a peritoneal incision over possible hernia sites. TEP is different in that the peritoneal cavity is not entered and mesh is used to seal the hernia from outside the peritoneum (the thin membrane covering the organs in the abdomen). This approach is considered to be more difficult than TAPP but may have fewer complications. Laparoscopic repair is technically more difficult than open repair. The review authors searched the medical literature and found one controlled trial in which 52 mainly male adults were randomised to the two different laparoscopic techniques, carried out by an experienced surgeon. The trial reported that there was no clear difference between TAPP and TEP when considering duration of operation, haemotoma, length of stay, time to return to usual activity or in recurrence of a hernia in the follow‐up time of only three months. The authors also looked at non‐randomised prospective studies that included more than 500 participants and large prospective case series with greater than 1000 participants for complications and adverse events. From nine studies, a small increase in the number of hernias developing close by and injuries to internal organs were apparent with TAPP and conversions to another type of surgery were more frequent with TEP. These results were broadly consistent. Vascular injuries and deep and mesh infections were rare and there was no obvious difference between the two techniques.

Background

An inguinal hernia is a defect in the endo‐abdominal fascia of sufficient size to allow escape of intraperitoneal or pre‐peritoneal contents into the groin. Inguinal hernias usually present as a lump, with or without some discomfort, which may limit daily activities and the ability to work. They can occasionally be life‐threatening if the bowel strangulates or becomes obstructed. Hernia repairs are responsible for approximately 80,000 finished consultant episodes, 100,000 bed days and 33,000 day cases per year in England and Wales alone (HES 2003).

Open surgical techniques using a mesh prosthesis instead of sutures to repair the defect are most commonly used to repair inguinal hernia (O'Riordan 1996). However, there is a continuing increase in the number of laparoscopic procedures performed since their introduction using mesh in the late 1991(Corbitt 1991, Schultz 1991). Exact figures on the types of repair used in current surgical practice are not easy to obtain (Wellwood 1998). In 2000, an audit of the NHS in Scotland between 1 April 1998 and 31 March 1999 found that 229 (4%) of inguinal hernia repairs were carried out using laparoscopic surgery, 4612 (84%) were open mesh surgery, 65 (1%) open preperitoneal surgery, and 600 (11%) were open non‐mesh surgery (Hair 2000). Most repairs were performed using general anaesthetic on an inpatient basis and there was a significant trend to perform a laparoscopic repair or an open preperitoneal repair for patients with bilateral and recurrent hernias.

The most commonly used laparoscopic techniques for inguinal hernia repair are transabdominal preperitoneal (TAPP) repair and totally extraperitoneal (TEP) repair. TAPP requires access to the peritoneal cavity with placement of a mesh through a peritoneal incision. This mesh is placed in the preperitoneal space covering all potential hernia sites in the inguinal region. The peritoneum is then closed above the mesh leaving it between the preperitoneal tissues and the abdominal wall where it becomes incorporated by fibrous tissue. TEP repair was first reported in 1993 (Ferzli 1993). TEP is different in that the peritoneal cavity is not entered and mesh is used to seal the hernia from outside the peritoneum. This approach is considered to be more difficult than TAPP but may lessen the risks of damage to the internal organs and of adhesion formation leading to intestinal obstruction, which has been linked to TAPP.

Laparoscopic repair is technically more difficult than open repair and there is evidence of a 'learning curve' in its performance (Wright 1998). It is likely that some of the higher rates of potentially serious complications reported for laparoscopic repair are associated with learning effects, particularly for the more complex TEP repair.

Indirect comparisons between TAPP and TEP have raised questions about whether the two procedures do perform differently for some outcomes such as recurrence. Very large randomised controlled trials such as those conducted by the MRC Laparoscopic Groin Hernia Group and Neumayer and colleagues, both of which a compared a predominatly TEP arm with open repair, suggested that TEP has a higher risk of recurrence than open mesh repair. However, a systematic review comparing laparoscopic with open mesh repair found no evidence of a difference in recurrence rates between TAPP and open mesh repair (McCormack 2003; McCormack NICE 2004). While any conclusions drawn on such indirect comparisons should be treated with caution they do raise questions that can only be satisfactory addressed by well designed studies and systematic reviews of such studies that directly compare TAPP with TEP.

There is a scarcity of data directly comparing laparoscopic TAPP and laparoscopic TEP and questions remain about their relative merits and risks. In light of this, the review aims to compare TAPP and TEP directly in order to determine which method is associated with better outcomes, in particular, serious adverse events and subsequent potential consequences such as persisting pain.

Objectives

The purpose of this review was to compare the clinical effectiveness and relative efficiency of laparoscopic TAPP and laparoscopic TEP for inguinal hernia repair. The review was conducted as part of a Health Technology Assessment on behalf of the National Institute for Clinical Excellence in the UK , which also compared laparoscopic (TAPP and TEP) with open mesh repair (McCormack NICE 2004).

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All published and unpublished randomised controlled trials and quasi‐randomised controlled trials comparing laparoscopic TAPP with laparoscopic TEP were eligible for inclusion. Trials were included irrespective of the language in which they were reported. Where there was a scarcity of data, non‐randomised prospective studies with concurrent comparators, prospective comparative studies with non‐concurrent comparators including more than 500 participants and large prospective case series with greater than 1000 participants were identified in order to provide further comparative evidence of complications and adverse events.

Types of participants

Relevant participants are adult patients requiring surgery for repair of inguinal hernia (direct and indirect), children (particularly under the age of 12) were not included since laparoscopic hernia repair is currently not recommended for these patients. Where available, data were split by whether or not bilateral and recurrent inguinal hernias.

Types of interventions

Laparoscopic methods of surgical repair of inguinal hernia:

a) Laparoscopic TAPP b) Laparoscopic TEP

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes: Serious adverse events (including visceral injuries and vascular injuries) Persisting pain Hernia recurrence

Secondary outcomes: Duration of operation (min) Opposite method initiated Conversion Haematoma Seroma Wound/Superficial Infection Mesh/Deep Infection Port site hernia Length of hospital stay (Days) Time to return to usual activities (Days) Persisting numbness Quality of Life Health service resource use and costs

Search methods for identification of studies

The following search strategy was used to identify studies indexed in Medline (1999‐June week 1 2003). Since the first reported use of a prosthetic mesh in laparoscopic repair was in 1991 and TEP was not reported until 1992, searches were limited to 1990 to present.

1.hernia inguinal/su 2.(inguinal or groin).tw 3.hernioplasty.tw 4.henriorrhaphy.tw 5.(hernia adj3 repair).tw 6.2 and (3 or 4 or 5) 7.1 or 6 8.tapp.tw 9.tep.tw 10.(transabdominal or preperitoneal or transperitoneal).tw 11.extraperitoneal.tw 12.7 and (8 or 9 or 10 or 11)

This strategy was adapted for use in other electronic databases. These were Medline Extra (June 13th 2003), Embase (1990‐Week 23, 2003), Biosis (1990‐18th June 2003), Science Citation Index (1991‐21st June 2003), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (Issue 2, 2003), Journals@ Ovid Full Text (25th July 2003) and the electronic version of the journal, Surgical Endscopy (1996‐ June 2003). Only selected journals were searched in the Journals@ Ovid Full Text : Annals of Surgery 1996 ‐ July 2003, Archives of Surgery 1995 ‐ June 2003, British Journal of Surgery and Supplements 1995 ‐ June 2003 and Surgical Laparoscopy 1996 ‐ June 2003.

Recent conference proceedings by the following organisations were hand searched:

Association of Endoscopic Surgeons of Great Britain & Ireland (1999‐2003) International Congress of the European Association for Endoscopic Surgery (2000‐2002) Scientific Session of the Society of American Gastrointestinal & Endoscopic Surgeons (SAGES) (2001‐2003) Italian Society of Endoscopic Surgery

In addition, specialists involved in research on the repair of inguinal hernia were contacted to ask for information about any further completed and ongoing trials, relevant websites were searched and reference lists of the all included studies were checked for additional report.

Data collection and analysis

All abstracts identified by the above search strategies were assessed for subject relevance by two researchers. The full publications of all possibly relevant abstracts were obtained and formally assessed for inclusion. A data abstraction form was developed to record details of study design, participants, setting and timing, interventions, patient characteristics, and outcomes. Data abstraction was performed independently by two reviewers. Where a difference of opinion existed, the two reviewers consulted an arbiter. All studies that met the selection criteria were assessed for methodological quality. The system for classifying methodological quality of controlled trials was based on an assessment of the four principal potential sources of bias. These were: selection bias from inadequate concealment of allocation of treatments; attrition bias from losses to follow‐up without appropriate intention‐to‐treat analysis, particularly if related to one or other surgical approaches; detection bias from biased ascertainment of outcome where knowledge of the allocation might have influenced the measurement of outcome; and selection bias in analysis. Studies reporting health service resource use and economic measures of quality of life outcomes may be subject to additional biases. Therefore, the methodological quality of studies reporting economic data (costs, economic measures of effectiveness such as quality adjusted life years, and cost‐effectiveness) were reported additional quality assessment was performed. This quality assessment used the Drummond checklist for the critical appraisal of economic evaluations (Drummond 1997). This checklist asks a series of questions relating to the quality of the economic component of the study. These were:

1) Was a well‐defined question posed in an answerable form? Yes/No/Cannot tell 2) Was a comprehensive description of the competing alternatives given (i.e. can you tell who, did what, to whom, where, and how often)? Yes/No/Cannot tell 3) Was there evidence that the programmes effectiveness had been established? Yes/No/Cannot tell 4) Were all important and relevant costs for each alternative identified? Yes/No/Cannot tell 5) Were all important and relevant consequences for each alternative identified? Yes/No/Cannot tell 6) Were costs measured accurately in appropriate physical units? Yes/No/Cannot tell 7) Were consequences measured accurately in appropriate physical units? Yes/No/Cannot tell 8) Were costs valued credibly? Yes/No/Cannot tell 9) Were consequences valued credibly? Yes/No/Cannot tell 10) Were costs adjusted for differential timing? Yes/No/Cannot tell 11) Were consequences adjusted for differential timing? Yes/No/Cannot tell 12) Was an incremental analysis of costs and consequences of alternatives performed? Yes/No/Cannot tell 13) Did the presentation and discussion of study results include all issues of concern to users? Yes/No/Cannot tell

Studies that did not present a full economic evaluation (studies that only reported either costs or economic measures of effects) were only assessed against those questions that were relevant.

The review was conducted using the standard Cochrane software 'Revman'. We aimed to do a formal quantitative meta‐analyses of data from comparable trials using the methods described by Yusuf and colleagues (Yusuf 1985). In the event, only one randomised controlled trial was available and a narrative review was undertaken. For this reason studies using other designs were identified in order to provide further comparative evidence of complications and adverse events. Attention was focussed on vascular injuries, visceral injuries, deep/mesh infections, port site hernia, and conversions because these were deemed to be the more serious complications.

It is widely accepted that a learning effect exists for laparoscopic repair and particularly for the more complex TEP repair. This is an important consideration and therefore a separate search was carried out on MEDLINE, EMBASE and Science Citation Index databases to identify any papers reporting learning curves for TAPP and TEP.

Results

Description of studies

Number and type of studies included Only one randomised controlled trial (Schrenk 1996) was available and reported outcomes on operation time, intra‐operative and postoperative complications, length of hospital stay, time to return to work, time to return to usual activities and hernia recurrence. Five studies with concurrent comparators were identified (Cohen 1998, Felix 1995, Khoury 1995, Lepere 2000, Van Hee 1998); one with a non‐concurrent comparator (Weiser 2000); and three studies (Baca 2000, Leibl 2000, Tamme 2003) were case series (TEP, 5203 hernia repairs (Tamme 2003) and TAPP, 2500 (Baca 2000) and 5203 (Leibl 2000) hernia repairs respectively). Details of these studies can be found in the Characteristics of included studies.

Number and type of randomised studies excluded, with reasons for specific exclusions This search strategy was used in conjunction with another review. The combined number and types of randomised studies excluded, with reasons for specific exclusions are reported in McCormack 2004.

Number and type of non‐randomised studies excluded, with reasons for specific exclusions 18 articles were obtained but were excluded because they failed to meet one or more of the specified inclusion criteria in terms of study design, participants, interventions, or outcomes. Of the 18 articles excluded, six were non‐concurrent comparative studies with less than 500 participants, four were case‐series with less than 1000 participants, four studies were restrospective, 3 studies only provided the overall results for TAPP/TEP, and one study only provided descriptive information for the techniques.

Risk of bias in included studies

Only one randomised controlled trial (Schrenk 1996) was eligible for inclusion. The concealment of allocation was by sealed envelope and there were no losses to follow‐up. However, it was unclear if the outcome assessor was blinded or if analysis was by intention‐to‐treat. The mean duration of follow‐up was 3 months, hernia diagnosis was confirmed by clinical examination and the operation was reported to have been performed by an 'experienced' surgeon.

Effects of interventions

Randomised Controlled Trials The results are tabulated in Additional Table 01 (Table 1).

1. Results from study comparing effectiveness of TAPP with TEPP.

| Outcomes | TAPP (n=28) | TEP (n=24) |

| Operation time (mean/SD) | 46.0 (9.2) | 52.3 (13.9) |

| Intraoperative complications | None | None |

| Haematoma | 1/28 | 0/24 |

| Time to return to usual activities (days) (mean/SEM): | ||

| Walking | 8.6 (1.4) | 8.5 (1.3) |

| Driving a car | 10.1 (1.4) | 12.4 (1.7) |

| Sexual Intercourse | 17.7 (2.7) | 18.9 (2.6) |

| Sports | 35.5 (4.9) | 35.2 (4.6) |

| Time to return to work (weeks) (mean/SEM) | 4.9 (0.7) | 4.6 (0.6) |

| Length of hospital stay (mean/SD) | 3.7 (1.4) | 4.4 (0.9) * |

| Recurrence at 3 months | 1/28 | 0/24 |

| * Statistically significant result; SEM = Standard error of the mean; SD = Standard deviation |

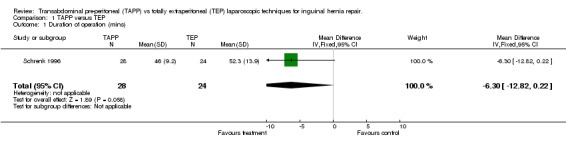

Duration of operation (minutes) The operating time was slightly longer in TEP than TAPP, however the difference was not statistically significant (Comparison 03:01: WMD ‐6.30 minutes, 95% CI ‐12.82 to 0.22; p= 0.06).

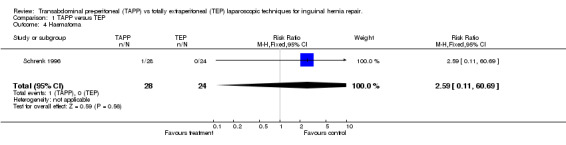

Haematoma There was only one haematoma recorded in the study and this was in the TAPP group (Comparison 03:04: RR 2.59, 95% CI 0.11 to 60.69; p=0.6).

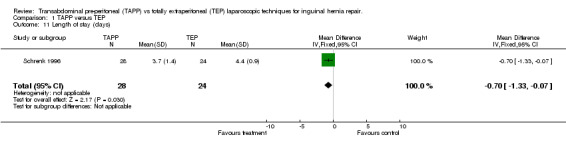

Length of stay (days) Length of stay was shorter in the TEP group (Comparison 03:11: WMD ‐0.70 days, 95% CI ‐1.33 to ‐0.07; p=0.03).

Time to return to usual activity (days) An overall figure for time to return to usual activities was not given in the paper, however several separate activities were listed. Of all of those listed there were no statistically significant differences between the TAPP and TEP groups.

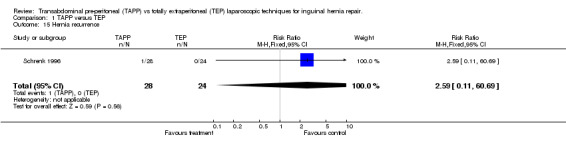

Hernia recurrence Hernia recurrence was only assessed up to three months. Within this time there was one recurrence in the TAPP group (Comparison 03:15: RR 2.59, 95% CI 0.11 to 60.69; p=0.6).

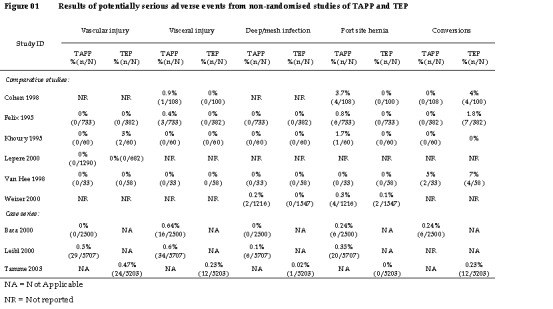

Complications/adverse events from non‐randomised studies and observational studies The results are presented in Figure 01 (Figure 1).

1.

Results of potentially serious adverse events from non‐randomised studies of TAPP and TEP

Vascular injury Seven studies reported vascular injuries (Baca 2000, Felix 1995, Khoury 1995, Leibl 2000, Lepere 2000, Tamme 2003, Van Hee 1998) including three large case series (Baca 2000, Leibl 2000, Tamme 2003) In the comparative studies, three reported no vascular injuries (Felix 1995, Lepere 2000, Van Hee 1998) whilst one reported a higher rate (3% versus 0%) in TEP, however this was only a small study of 120 patients (Khoury 1995). In the three case series, one reported no vascular injuries in TAPP (Baca 2000) while the rates from the other two case series showed similar rates for TAPP (0.5%, based on 5707 cases) (Leibl 2000) and TEP (0.47% based on 5203 cases) (Tamme 2003).

Visceral injury Seven studies reported visceral injuries (Baca 2000, Cohen 1998, Felix 1995, Khoury 1995, Leibl 2000, Tamme 2003, Van Hee 1998) including the three large case series (Baca 2000, Leibl 2000, Tamme 2003). In the comparative studies, two reported no visceral injuries (Khoury 1995, Van Hee 1998) whilst two reported a higher rate (0.9% versus 0% and 0.4% versus 0%) in TAPP than in TEP (Cohen 1998, Felix 1995). The combined number of cases in these studies was 1323. In the three case series, the two TAPP series (Baca 2000, Leibl 2000) reported similar rates of 0.64% and 0.6% with a combined case number of 8207 whilst the one TEP series reported a lower rate of 0.23% based on 5203 cases (Tamme 2003).

Mesh/deep infection Deep infections, primarily mesh infections, are potentially more serious than superficial infections and can result in removal of the mesh. These were reported in seven studies (Baca 2000, Felix 1995, Khoury 1995, Leibl 2000, Tamme 2003, Van Hee 1998, Weiser 2000). In the comparative studies, three reported no deep infections (Felix 1995, Khoury 1995, Van Hee 1998) whilst one reported rates of 0.2% and 0% for TAPP and TEP respectively (Weiser 2000). Rates for TAPP were low in the two case series (Baca 2000,Leibl 2000) i.e. 0% and 0.1%. The rate in TEP was again low, 0.02%,and did not indicate a difference between TAPP and TEP (Tamme 2003).

Port‐site hernia Eight of the nine studies reported port‐site hernia (Baca 2000, Cohen 1998, Felix 1995, Khoury 1995, Leibl 2000, Tamme 2003, Van Hee 1998, Weiser 2000). The comparative studies showed rates of 0% to 3.7% (Cohen 1998, Felix 1995, Khoury 1995, Van Hee 1998, Weiser 2000). In all four studies where cases of port‐site hernia were reported, TAPP was associated with a higher rate than TEP (Cohen 1998, Felix 1995, Khoury 1995, Weiser 2000). In three studies there were no cases of port site hernia reported in the TEP groups compared to 3.7% (Cohen 1998), 0.8% (Felix 1995) and 1.7% (Khoury 1995) in the TAPP groups. This trend was also seen in the case series where there were no reported cases of port‐site hernia amongst 5203 TEP repairs (Tamme 2003) compared to 0.24% Baca 2000) and 0.35% (Leibl 2000) amongst 8207 TAPP repairs.

Conversions The conversion rate was reported in six of the studies (Baca 2000, Cohen 1998, Felix 1995, Khoury 1995, Tamme 2003, Van Hee 1998). In three of the four comparative studies the rate was higher in the TEP group, with rates of 0% versus 4% (Cohen 1998), 0% versus 1.8% (Felix 1995) and 5% versus 7% (Van Hee 1998). The fourth comparative study was small with only 120 procedures and had no conversions (Khoury 1995). However in the large case series the conversion rates between TAPP and TEP were very similar at 0.24% (Baca 2000) and 0.23% (Tamme 2003) respectively.

Costs and costeffectivenss No study reported data on relative efficiency or on costs or economic measures of effectiveness.

Learning effects Limited data were available in the included trials describing the effects of learning of laparoscopic techniques on the relevant outcomes, although it is widely accepted that a learning effect exists for laparoscopic repair and particularly for the more complex TEP repair. It was concluded that this was an important consideration and therefore a separate search was carried out on MEDLINE, EMBASE and Science Citation Index databases to identify any papers reporting learning curves for TAPP and TEP. The following search strategy was used to identify studies indexed in MEDLINE (1966 ‐ July Week 2 2003), EMBASE (1980 ‐ Week 29 2003), Ovid Multifile Search, URL: http://gateway.ovid.com/athens

1. hernia,inguinal/su 2. (inguinal or groin).tw. 3. hernioplasty/ use emez 4. herniorrhaphy/ use emez 5. hernioplasty.tw. 6. herniorrhaphy.tw. 7. (hernia adj3 repair).tw. 8. 2 and (3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7) 9. 1 or 8 10. (tapp or transabdominal or preperitoneal or transperitoneal).tw. 11. (tep or total$ extraperitoneal).tw. 12. 2 and (10 or 11) 13. laparoscopy/ 14. laparoscopic surgery/ use emez 15. endoscopy/ 16. endoscopic surgery/ use emez 17. Video‐Assisted Surgery/ 18. (laparoscop$ or endoscop$ or video$).tw. 19. 13 or 14 or 15 or 16 or 17 or 18 20. 9 and 19 21. 12 or 20 22. clinical competence/ 23. surgical training/ use emez 24. surgery/ed use mesz 25. (learn$ adj3 curve$).tw. 26. (learn$ adj3 (effect$ or rate? or method?)).tw. 27. (skill? adj3 (acquir$ or acquisit$ or develop$)).tw. 28. (competence adj3 (acquir$ or acquisit$ or develop$)).tw. 29. (expertise adj3 (acquir$ or acquisit$ or develop$)).tw. 30. (error? or mistake?).tw. 31. (surgeon? adj3 (experience? or expertise or skill? or competence)).tw. 32. training.tw. 33. or/22‐32 34. 21 and 33 35. remove duplicates from 34

The following search strategy was used to identify studies indexed in Science Citation Index 1981 ‐ 21st June 2003, Web of Knowledge URL: http://wok.mimas.ac.uk/ (((tapp or transabdominal or preperitoneal or transperitoneal or tep or extraperitoneal) and hernia*) or ((hernia* or hernio*) and (laparoscop* or endoscop* or video*))) and ((learning same (curve* or effect* or rate* or method*) or (skill* or expertise or competence) same (acquir* or acquisit* or develop*) or (surgeon* same (experience or expertise or skill* or competence*)) or (error* or mistake* or training))

Searches identified an additional 175 reports, 37 of which were considered potentially relevant. Full text papers were obtained, where available, and formally assessed independently by two researchers to check whether they met the inclusion criteria, using a study eligibility form developed for this purpose. Any disagreements that could not be resolved through discussion were referred to an arbiter. The following inclusion criteria were applied:

Data reported for an individual operator rather than an institution

Data reported for at least three points on the learning curve

Consecutive procedures

Data reported for at least one of the relevant learning outcomes

The relevant outcomes were: duration of operation; complications; length of stay; return to usual activities; hernia recurrence; persisting pain; and persisting numbness. Seven studies were included (Lau 2002, Aeberhard 1999, Leibl 2000a, Liem 1996, Ramsay 2001, Voitk 1998, Wright 1998) although two provided the same data (Liem 1996, Wright 1998) and so results from the study with most detail are shown in the tables (Wright (1) 1998).

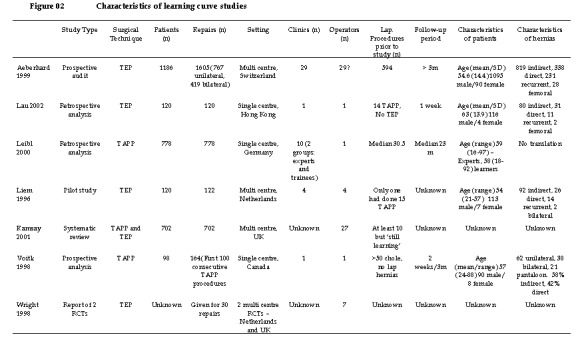

Data were abstracted using a pre‐designed and piloted data extraction form. Two reviewers extracted data independently. Any differences that could not be resolved through discussion were referred to an arbiter. Figure 02 provides details of the characteristics of the included studies (Figure 2). Two studies were prospective audits (Aeberhard 1999, Voitk 1998), two were retrospective analyses (Leibl 2000a, Lau 2002), one was a report of two RCTs (Wright 1998), and one was a systematic review (Ramsay 2001). Two studies (Leibl 2000a, Voitk 1998) considered the TAPP repair, three studies considered the TEP repair (Aeberhard 1999, Wright 1998, Lau 2002) and one considered a combination of both (Wright 1998). The number of laparoscopic procedures performed prior to the study varied, however for the majority of surgeons TAPP and/or TEP were relatively new techniques. The characteristics of patients, where given, did not vary significantly between the studies. Studies ranged in size from 120 repairs for one surgeon to 1605 repairs for 29 surgeons.

2.

Characteristics of learning curve studies

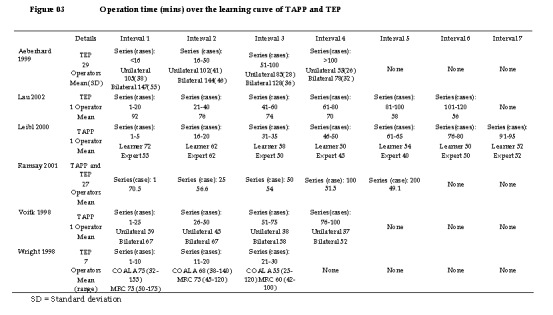

Although data were collected for several outcomes, it was considered inappropriate (due to study heterogeneity and scarcity of data) to report on any outcome other than duration of operation. This data indicate that it takes between 30 and 100 procedures to become 'expert' in performing laparoscopic hernia repair,although in the majority of the studies the figure was more likely to be closer to 50 or more procedures. However this could be misleading since surgeons performing TEP may already be experienced in TAPP. Crude interpretation of these data provide estimates for duration of operation for inexperienced operators (up to 20 procedures) to be 70 minutes for TAPP and 95 minutes for TEP. For experienced operators (between 30 and 100 procedures) the estimated duration of operation are 40 minutes for TAPP and 55 minutes for TEP. Results of operation time from the studies can be seen in Figure 03 (Figure 3).

3.

Operation time (mins) over the learning curve of TAPP and TEP

Discussion

When considering the comparison of TAPP with TEP, only one small randomised trial (Schrenk 1996) met the inclusion criteria. There appeared to be no differences between TAPP and TEP in terms of length of operation, haematomas, time to return to usual activities and hernia recurrence, but confidence intervals were all wide.

The data about complications from the additional non‐RCT studies of TAPP and TEP suggest that an increased number of port‐site hernias and visceral injuries are associated with TAPP rather than TEP whilst there appear to be more conversions with TEP. These results appear to be broadly consistent regardless of the evidence source. Vascular injuries and deep/mesh infections were very rare and there was no obvious difference between the groups, the numbers being too small to draw any conclusions.

Although it appears that it may take between 30 and 100 procedures to become expert and that generally the operation time for TAPP is less for both experienced and inexperienced operators the data may be biased as it is possible that surgeons performing TEP are already experienced in TAPP.

The limited evidence base means that questions raised by the consideration of indirect comparisons between TAPP and TEP have not been adequately addressed by secure, adequately powered randomised comparisons.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Data from robust RCTs are not available to allow conclusions to be drawn about the relative effectiveness of TAPP and TEP and as such changes in practice can not be supported by evidence on effectiveness or efficiency.

Implications for research.

Efforts should be made to undertake adequately powered RCTs or well designed observational studies that compare the different methods of inguinal hernia repair.

Feedback

Erratum in introductory BACKGROUND section

Summary

The crediting of Ferzli for the first report on TEP is not correct. The first published article I am aware of is (in French): Dulucq JL.Traitement des hernies de l'aine par mise en place d'un patch prothethique sous‐peritonal en retro‐peritoneoscopie. Cahiers de Chirurgie 1991; 79: 15‐16. Further identified in EMBASE as: Chirurgie‐‐‐Memoires‐de‐l'Academie‐de‐Chirurgie. 1992; 118(1‐2): 83‐85 with an english title

Reply

None

Contributors

Name: Bengt Novik, Email Address: bengt.novik@vgregion.se ‐ Personal Description: Occupation consultant surgeon

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 5 August 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 2, 2004 Review first published: Issue 1, 2005

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 9 November 2004 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Substantive amendment |

Acknowledgements

Funded by the UK Department of Health and administered by NHS Executive R&D Health Technology Assessment Programme as a Technology Assessment Review conducted for the National Institute for Clinical Excellence. The Health Services Research Unit and Health Economics Research Unit are funded by the Chief Scientist's Office of the Scottish Executive Health Department. Janet Wale, CCNet‐Contact, for the synopsis.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. TAPP versus TEP.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Duration of operation (mins) | 1 | 52 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐6.30 [‐12.82, 0.22] |

| 2 "Opposite" method initiated | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 3 Conversion | 1 | 52 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 4 Haematoma | 1 | 52 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.59 [0.11, 60.69] |

| 5 Seroma | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 6 Wound/superficial infection | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 7 Mesh/deep infection | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 8 Vascular injury | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 9 Visceral injury | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 10 Port‐site hernia | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 11 Length of stay (days) | 1 | 52 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.70 [‐1.33, ‐0.07] |

| 12 Time to return to usual activities (days) | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 13 Persisting numbness | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 14 Persisting pain | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 15 Hernia recurrence | 1 | 52 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.59 [0.11, 60.69] |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 TAPP versus TEP, Outcome 1 Duration of operation (mins).

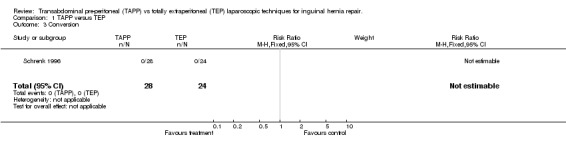

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 TAPP versus TEP, Outcome 3 Conversion.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 TAPP versus TEP, Outcome 4 Haematoma.

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1 TAPP versus TEP, Outcome 11 Length of stay (days).

1.15. Analysis.

Comparison 1 TAPP versus TEP, Outcome 15 Hernia recurrence.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Baca 2000.

| Methods | Retrospective case series | |

| Participants | 92% Male Average age 59 (range 19‐88) 32% Direct 37% Indirect 2% Femoral 12% Combined 17% Recurrent 22% Bilateral Mean Follow‐up 39 months (range 4 weeks to 7 yrs) 87% patients included in analysis | |

| Interventions | 2500 TAPP repairs | |

| Outcomes | Vascular injury Visceral injury Mesh/deep infection Port‐site hernia Conversions | |

| Notes | Germany | |

Cohen 1998.

| Methods | Prospective comparative observational study with concurrent control | |

| Participants | TAPP: 100% Male Mean age 35 (range 21‐73) ‐ Overall only 28% Unilateral 38% Bilateral 33% Recurrent TEP: 100% Male Mean age 35 (range 21‐73) ‐ Overall only 9% Unilateral 49% Bilateral 42% Recurrent | |

| Interventions | 108 TAPP repairs 100 TEP repairs | |

| Outcomes | Visceral injury Port‐site hernia Conversions | |

| Notes | Brazil | |

Felix 1995.

| Methods | Retrospective comparative observational study with concurrent control | |

| Participants | 87% male Mean age 49 (range 12‐89) Median follow‐up: 24 month (TAPP) and 9 months (TEP) 60% indirect 23.6% direct 15.3% pantaloon 1% femoral | |

| Interventions | 733 TAPP repairs 382 TEP repairs | |

| Outcomes | Vascular injury Visceral injury Mesh/deep infection Port‐site hernia Conversions | |

| Notes | USA | |

Khoury 1995.

| Methods | Prospective comparative observational study with concurrent control | |

| Participants | TAPP: 91% Male Age range (20‐76) 67% indirect 28% direct 3% femoral 2% combined TEP: 93% Male Age range (20‐73) 68% indirect 27% direct 2% femoral 3% combined | |

| Interventions | 60 TAPP repairs 60 TEP repairs | |

| Outcomes | Vascular injury Visceral injury Mesh/deep infection Port‐site hernia Conversions | |

| Notes | Canada | |

Leibl 2000.

| Methods | Retrospective case series | |

| Participants | Not reported | |

| Interventions | 5707 TAPP repairs | |

| Outcomes | Vascular injury Visceral injury Mesh/deep infection Port‐site hernia | |

| Notes | Germany | |

Lepere 2000.

| Methods | Retrospective comparative observational study with concurrent control | |

| Participants | TAPP: 87% Male overall 63% unilateral 37% bilateral 9% recurrent TEP: 87% Male overall 74% unilateral 36% bilateral 8% recurrent | |

| Interventions | 1290 TAPP repairs 682 TEP repairs | |

| Outcomes | Vascular injury | |

| Notes | France | |

Schrenk 1996.

| Methods | Single‐centre RCT 52 participants included (86 in total) Follow‐up = 3months Full text | |

| Participants | TAPP: 28/28 General Anaesthetic 0/28 Bilateral 0/28 Recurrent 9/28 Direct 19/28 Indirect Age mean (SD) 39.1(14.3) 24 Male/4 Female TEP: 24/24 General Anaesthetic 0/24 Bilateral 0/24 Recurrent 6/24 Direct 18/24 Indirect Age mean (SD) 42.3(11.9) 22 Male/2 Female | |

| Interventions | 28 TAPP repairs versus 24 TEP repairs | |

| Outcomes | Duration of operation Conversions Intraoperative complications Postoperative complications Length of hospital stay Return to work Hernia recurrence | |

| Notes | Austria | |

Tamme 2003.

| Methods | Retrospective case series | |

| Participants | Median age 53 (range 15‐89) 91% male 32% direct 57% indirect 8% combined 3% femoral 13% recurrent 35% bilateral | |

| Interventions | 5203 TEP repairs | |

| Outcomes | Vascular injury Visceral injury Mesh/deep infection Port‐site hernia Conversions | |

| Notes | Germany | |

Van Hee 1998.

| Methods | Prospective comparative observational study with concurrent control | |

| Participants | TAPP: 100% Male Mean age 58 range (20‐79) 78% unilateral 22% bilateral 43% direct 54% direct 3% combined 5% recurrent TEP: 97% Male Mean age 59 range (21‐84) 68% unilateral 32% bilateral 29% direct 59% indirect 12% combined 10% recurrent | |

| Interventions | 37 TAPP repairs 69 TEP repairs | |

| Outcomes | Vascular injury Visceral injury Mesh/deep infection Port‐site hernia Conversions | |

| Notes | Belgium | |

Weiser 2000.

| Methods | Retrospective comparative observational study | |

| Participants | Not reported | |

| Interventions | 1216 TAPP repairs 1547 TEP repairs | |

| Outcomes | Mesh/deep infection Port‐site hernia | |

| Notes | Germany | |

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Baca 1995 | Non‐concurrent comparative study with less than 500 partitcipants. |

| Blanc 1999 | Case‐series with less than 1000 participants. |

| Camps 1995 | Descriptive study. |

| Cocks 1998 | Non‐concurrent comparative study with less than 500 partitcipants. |

| Cohen (1) 1998 | Overall results for TAPP/TEP. |

| Felix 1996 | Restrospective study. |

| Felix 1998 | Restrospective study. |

| Felix 1999 | Restrospective study. |

| Fielding 1995 | Non‐concurrent comparative study with less than 500 partitcipants. |

| Fitzgibbons 1995 | Overall results for TAPP/TEP. |

| Jarhult 1999 | Non‐concurrent comparative study with less than 500 partitcipants. |

| Johanet 1999 | Overall results for TAPP/TEP. |

| Kald 1997 | Non‐concurrent comparative study with less than 500 partitcipants. |

| Keidar 2002 | Case‐series with less than 1000 participants. |

| Lodha 1997 | Case‐series with less than 1000 participants. |

| Moreno‐Egea 2000 | Case‐series with less than 1000 participants. |

| Ramshaw 1995 | Non‐concurrent comparative study with less than 500 partitcipants. |

| Ramshaw 1996 | Restrospective study. |

Contributions of authors

Tragically our colleague Bev Wake died in a car accident just before Christmas 2003. We are all shocked and saddened by this tragedy and we pass on our condolences to Bev's family. This review is dedicated to Bev.

The search strategy was developed by Cynthia Fraser. Abstract assessment and full text quality assessment were performed by BW and KMc. Data abstraction and methodological quality assessment were conducted by BW and KMc. The assessment of learning effects was performed by BW and KMc. The economic evaluation was performed by LV and JP. The data input to Revman was performed by KMc. The interpretation of results was undertaken mainly by BW. All reviewers contributed to the writing of the report, which was led by BW and KMc.

Sources of support

Internal sources

University of Aberdeen, Health Services Research Unit, UK.

External sources

National Institute of Clinical Excellence, UK.

Declarations of interest

There are no potential conflicts of interest

Edited (no change to conclusions)

References

References to studies included in this review

Baca 2000 {published data only}

- Baca I, Schultz C, Gotzen V, Jazek G. Laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair. A review of 2500 cases. In: Lomanto D, Kum CK, So JBY, Goh PMY, editors. Proceedings of the 7th World Congress of Endoscopic Surgery. 2000:425‐430.

Cohen 1998 {published data only}

- Cohen RV, Alvarez G, Roll S, Garcia ME, Kawahara N, Schiavon CA, et al. Transabdominal or totally extraperitoneal laparoscopic hernia repair?. Surgical laparoscopy and endoscopy 1998;8(4):264‐268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Felix 1995 {published data only}

- Felix EL, Michas CA, Gonzalez MH, Jr. Laparoscopic hernioplasty. TAPP vs TEP. Surgical Endoscopy 1995;9(9):984‐989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Khoury 1995 {published data only}

- Khoury N. A comparative study of laparoscopic extraperitoneal and transabdominal preperitoneal herniorrhaphy. Journal of Laparoendoscopic Surgery 1995;5(6):349‐355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Leibl 2000 {published data only}

- Leibl BJ, Schmedt CG, Kraft K, Bittner R. Laparoscopic transperitoneal hernioplasty (TAPP) ‐ efficiency and dangers. Chirurgische Gastroenterologie 2000;16(2):106‐109. [Google Scholar]

Lepere 2000 {published data only}

- Lepere M, Benchetrit S, Debaert M, Detruit B, Dufilho A, Gaujoux D, et al. A multicentric comparison of transabdominal versus totally extraperitoneal laparoscopic hernia repair using PARIETEX meshes. Journal of the Society of Laparoendoscopic Surgeons 2000;4(2):147‐153. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Schrenk 1996 {published data only}

- Schrenk P, Bettelheim P, Woisetschlager R, Rieger R, Wayand WU. Metabolic responses after laparoscoic or open hernia repair. Surgical Endoscopy 1996;10(6):628‐632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrenk P, Woisetschlager R, Rieger R, Wayand W. Prospective randomised trial comparing postoperative pain and return to physical activity after transabdominal preperitoneal, total preperitoneal or Shouldice technique for inguinal hernia repair. British Journal of Surgery 1996;83(11):1563‐1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Tamme 2003 {published data only}

- Tamme C, Scheidbach H, Hampe C, Schneider C, Kockerling F. Totally extraperitoneal endsocopic inguinal hernia repair (TEP). Surgical Endoscopy 2003;17(2):190‐195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Van Hee 1998 {published data only}

- Hee R, Goverde P, Hendrickx L, SG, Totte E. Laparoscopic transperitoneal versus extraperitoneal inguinal hernia repair: a prospective clinical trial. ACTA Chirurgica Belgica 1998;98(3):132‐135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Weiser 2000 {published data only}

- Weiser HF, Klinge B. Endoscopic hernia repair ‐ Experiences and characteristic features. Viszeralchirurgie 2000;35(5):316‐320. [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

Baca 1995 {published data only}

- Baca V, Gotzen V, Gerbatsch K‐P, Kondza G, Tokalic M. Laparoscopy in the treatment of inguinal hernias. Croatian Medical Journal 1995;36(3):166‐169. [Google Scholar]

Blanc 1999 {published data only}

- Blanc P, Porcheron J, Breton C, Bonnot P, Baccot S, Tiffet O, Cuilleret J, Balique JG. Results of laparoscopic hernioplasty A study of 401 cases in 318 patients. Chirurgie 1999;124(4):412‐418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Camps 1995 {published data only}

- Camps J, Nguyen N, Annabali R, Fitzgibbons RJ. Laparoscopic inguinal herniorrhaphy ‐ transabdominal techniques. International Surgery 1995;80(1):18‐25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Cocks 1998 {published data only}

- Cocks JR. Laparoscopic inguinal hernioplasty: a comparison between transperitoneal and extraperitoneal techniques. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Surgery 1998;68(7):506‐509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Cohen (1) 1998 {published data only}

- Cohen RV. Laparoscopic extraperitoneal repair of inguinal hernias. Surgical Laparoscopy & Endoscopy 1998;8(1):14‐16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Felix 1996 {published data only}

- Felix EL, Michas CA, Gonzalez MH, Jr. Laparoscopic repair of recurrent hernia. American Journal of Surgery 1996;172(5):580‐583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Felix 1998 {published data only}

- Felix E, Scott S, Crafton B, Geis P, Duncan T, Sewell R, McKernan B. Causes of recurrence after laparoscopic hernioplasty. A multicenter study. Surgical Endoscopy 1998;12(3):226‐231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Felix 1999 {published data only}

- Felix EL, Harbertson N, Vartanian S. Laparoscopic hernioplasty: significant complications. Surgical Endoscopy 1999;13(4):328‐331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Fielding 1995 {published data only}

- Fielding GA. Laparoscopic inguinal‐hernia repair. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Surgery 1995;65(5):304‐307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Fitzgibbons 1995 {published data only}

- Fitzgibbons RJ, Jr, Camps J, Cornet DA, Nguyen NX, Litke BS, Annibali R, Salerno GM. Laparoscopic inguinal herniorrhaphy. Results of a multicenter trial. Annals of Surgery 1995;221(1):3‐13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Jarhult 1999 {published data only}

- Jarhult J, Hakanson C, Akerud L. Laparoscopic treatment of recurrent inguinal hernias: experience from 281 operations. Surgical Laparoscopy, Endoscopy & Percutaneous Techniques 1999;9(2):115‐118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Johanet 1999 {published data only}

- Johanet H, Sorrentino J, Bellouard A, Benchetrit S. Time off of work after inguinal hernia repair. Results of a multicenter prospective study. Annales de Chirurgie 1999;53(4):297‐301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kald 1997 {published data only}

- Kald A, Anderberg B, Smedh K, Karlsson M. Transperitoneal or totally extraperitoneal approach in laparoscopic hernia repair: results of 491 consecutive herniorrhaphies. Surgical Laparoscopy & Endoscopy 1997;7(2):86‐89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Keidar 2002 {published data only}

- Keidar A, Kanitkar S, Szold A. Laparoscopic repair of recurrent inguinal hernia. Surgical Endoscopy 2002;16(12):1708‐1712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lodha 1997 {published data only}

- Lodha K, Bhattacharya P, Weston Underwood J. Laparoscopic inguinal hernia reapir. Totally extraperitoneal or transabdominal. International College of Surgeons ‐ XX European Federation Congress. 1997:87‐91.

Moreno‐Egea 2000 {published data only}

- Moreno‐Egea A, Aguayo JL, Canteras M. Intraoperative and postoperative complications of totally extraperitoneal laparoscopic inguinal hernioplasty. Surgical Laparoscopy, Endoscopy & Percutaneous Techniques 2000;10(1):30‐33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ramshaw 1995 {published data only}

- Ramshaw BJ, Tucker JG, Mason EM, Duncan TD, Wilson JP, Angood PB, Lucas GW. A comparison of transabdominal preperitoneal (TAPP) and total extraperitoneal approach (TEPA) laparoscopic herniorrhaphies. American Surgeon 1995;61(3):279‐283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ramshaw 1996 {published data only}

- Ramshaw BJ, Tucker JG, Duncan TD, Heithold D, Garcha I, Mason EM, Wilson JP, Lucas GW. Technical considerations of the different approaches to laparoscopic herniorrhaphy: an analysis of 500 cases. American Surgeon 1996;62(1):69‐72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Additional references

Aeberhard 1999

- Aeberhard P, Klaiber C, Meyenberg A, Osterwalder A, Tschudi J. Prospective audit of laparoscopic totally extraperitoneal inguinal hernia repair: a multicenter study of the Swiss Association for Laparoscopic and Thoracoscopic Surgery (SALTC). Surgical Endoscopy 1999;13(11):1115‐1120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Corbitt 1991

- Corbitt J. Laparoscopic herniography. Surgical laparoscopy and endoscopy 1991;1:23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Drummond 1997

- Drummond M, O'Brien B, Stoddart G, Torrance G. Methods for the economic evaluation of healthcare programmes. 2nd Edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997. [Google Scholar]

Ferzli 1993

- Ferzli G, Masaad A, Albert P, Worth MH. Endoscpoic Extraperitoneal Herniorrhaphy versus Conventional Hernia Repair. A comparative study.. Current Surgery 1993;50:291‐294. [Google Scholar]

Hair 2000

- Hair A, Duffy K, McLean J, Taylor S, Smith H, Walker A, et al. Groin hernia repair in Scotland. Br J Surg 2000;87(12):1722‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

HES 2003

- Department of Health. Hospital Episode Statistics. Table 5 Main Operations 1998‐2001 Vol. www.doh.gov.uk/hes/standard_data/available_tables/.

Lau 2002

- Lau H. Learning curve for unilateral endoscopic totally extraperitoneal (TEP) inguinal hernioplasty. Surgical Endoscopy 2002;16(12):1724‐1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Leibl 2000a

- Leibl BJ, Schmedt CG, Ulrich M, Kraft K, Bittner R. Laparoscopic hernia therapy (TAPP) as a teaching operation. Chirurg 2000;71(8):939‐942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Liem 1996

- Liem MS, Steensel CJ, Boelhouwer RU, Weidema WF, Clevers GJ, Meijer WS, et al. The learning curve for totally extraperitoneal laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair. American Journal of Surgery 1996;171(2):281‐285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

McCormack 2003

- McCormack K, Scott NW, Go PMNYH, Ross S, Grany AM on behalf of the EU Trialists Collaboration. Laparoscopic techniques versus open techniques for inguinal hernia repair (Cochrane Review).. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2003, Issue 2. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001785] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

McCormack NICE 2004

O'Riordan 1996

- O'Riordan DC, Morgan M, Kingsnorth AN, Black NA, Clements L, Brady H, Gray V, Parkin J, Ambrose S, Jones P, Raimes S, Taylor R, Watkins D, Devlin HB. Current surgical practice in the management of groin hernia in the United Kingdom.. Report to the Department of Health 1996.

Ramsay 2001

- Ramsay CR, Grant AM, Wallace SA, Garthwaite PH, Monk AF, Russell IT. Statistical assessment of the learning curves of health technologies. Health Technology Assessment 2001;5(12):1‐79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Schultz 1991

- Schultz L, Graber J, Pietraffita, et al. Laser laparoscopic herniorrhaphy: A clinical trial. Preliminary results.. Journal of laparoendoscopic surgery 1991;1:41‐45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Voitk 1998

- Voitk AJ. The learning curve in laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair for the community general surgeon. Canadian Journal of Surgery 1998;41(6):446‐450. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Wellwood 1998

- Wellwood J, Sculpher M, Stoker D, Nicholls GJ, Geddes C, Whitehead A, et al. Randomised controlled trial of laparoscopic open mesh repair for inguinal hernia: outcome and cost.. British Medical journal 1998;317:103‐110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Wright 1998

- Wright D, O'Dwyer P.J. The learning curve for laparoscopic hernia repair. Seminars in Laparoscopic Surgery 1998;5(4):227‐232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Yusuf 1985

- Yusuf S, Peto R, Lewis J, Collins R, Sleight P. Beta blockade during and after myocardial infarction: an overview of randomized controlled trials. Progress in Cardiovascular Disease 1985;XXVI I:335‐371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]