SUMMARY

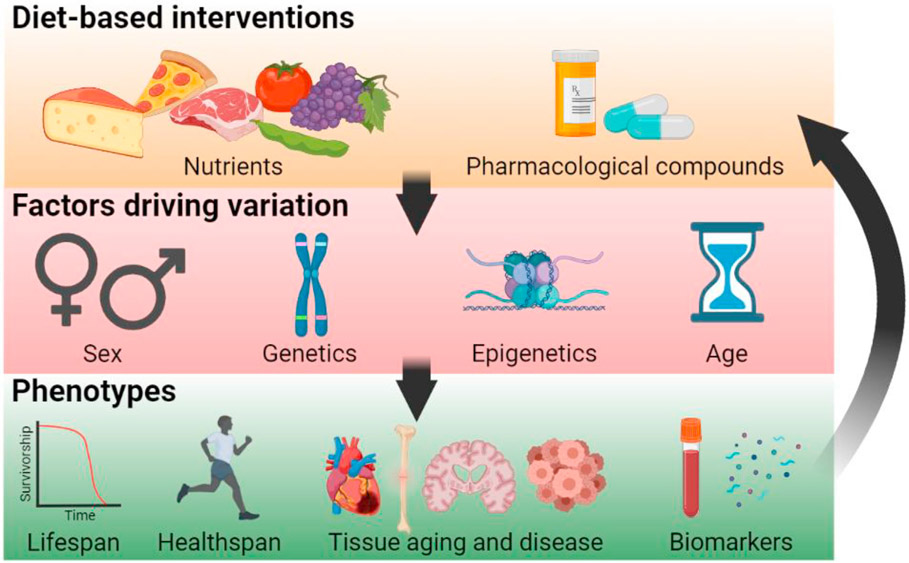

Dietary restriction (DR) has long been viewed as the most robust nongenetic means to extend lifespan and healthspan. Many aging-associated mechanisms are nutrient responsive, but despite the ubiquitous functions of these pathways, the benefits of DR often vary among individuals and even among tissues within an individual, challenging the aging research field. Furthermore, it is often assumed that lifespan interventions like DR will also extend healthspan, which is thus often ignored in aging studies. In this review, we provide an overview of DR as an intervention and discuss the mechanisms by which it affects lifespan and various healthspan measures. We also review studies that demonstrate exceptions to the standing paradigm of DR being beneficial, thus raising new questions that future studies must address. We detail critical factors for the proposed field of precision nutrigeroscience, which would utilize individualized treatments and predict outcomes using biomarkers based on genotype, sex, tissue, and age.

INTRODUCTION

In 1935, Dr. Clive McCay showed that dietary restriction (DR) in the form of calorie reduction (CR) without malnutrition prolongs mean and maximal lifespan in rats compared with those allowed to eat freely. Subsequent experiments in mice showed that ~40% of normal calorie consumption results in ~50% extension in lifespan (McCay, 1939). The potential of CR to extend lifespan has created a large subfield of aging research that promises a simple but elegant method to enhance lifespan and healthspan, the period of life in which an individual is healthy, with minimal side effects. CR is now known to extend lifespan in nearly thirty species, including nonhuman primates, and remains the most robust way to extend lifespan in the laboratory. In humans, a two-year clinical study on the effects of chronic, moderate CR showed a slowing in metabolism and decreased production of free radicals (Redman et al., 2018). Though this study indicated that changes induced by CR reduced markers of aging, the long-term effects of CR in humans remain unproven.

Distinct from CR, DR encompasses all dietary interventions that restrict intake of specific nutritional components. Thus, DR incorporates CR as well as restriction of macronutrients such as protein or amino acid residues (e.g., methionine and tryptophan) or glucose, and may also include varying fasting intervals (Table 1). Despite varying DR protocols, almost all dietary interventions have been reported to influence lifespan in at least one model organism (Table 2) and largely influence similar cellular pathways. However, differences in methodologies used to induce DR within and between species have led to disparities in cross-study comparisons. Given the variation across populations, individuals, and tissues, it is reasonable to expect an array of responses to different regimens. Further, the means of assessing aging vary greatly across studies, adding to difficulties in assessing how DR benefits longevity and health. Despite these variations in methodologies and responses, the knowledge of pathways that mediate nutrient signaling remains critical to help translate findings to humans. Precision nutrition has recently been proposed as a means to mediate health by creating personalized dietary plans (Rodgers and Collins, 2020), and a multitude of companies have aimed to maximize lifespan by precision nutrition but have not incorporated omics-based signatures to maximize individual effects. We propose that developing an individualized plan, which analyzes specific age-related biomarkers of an individual to optimize diet-based therapeutics to slow age-related biological processes, will give rise to a new form of precision-nutrition medicine, which we term “precision nutrigeroscience.” This field of study will incorporate diet-based therapeutics that are specific to an individual based on a panel of genotype-, diet-, age-, sex-, and health-specific biomarkers and will elucidate specific, individualized regimens to maximize lifespan and healthspan. Here, we detail the conserved mechanisms of DR but then delve into the complexities that influence individual responses to DR, which necessitates us to develop a framework for precision nutrigeroscience.

Table 1.

Types of dietary restrictions

| Dietary intervention | Description |

|---|---|

| Caloric restriction | Reduced caloric intake (20%–30% below average) without undergoing malnutrition during the entire period of dietary intervention. |

| Intermittent fasting | The alternate pattern of ad libitum food-intake-encompassing regimes that may include alternate-day fasting (ADF), modified ADF (limited calories supplied during fasting day), 5:2 diet (days of caloric restriction per week), or daily time-restricted feeding. |

| Fasting-mimicking diet | Four days of diet that mimics fasting (FMD) consisting of very low calorie/low protein. The ad libitum diet is fed between the period of FMD cycles. |

| Glucose and carbohydrate restriction | Carbohydrate consumption is restricted relative to the average diet and is replaced by food containing a higher percentage of fat and protein. aGlucose restriction refers to specific restriction of glucose intake instead of other forms of complex carbohydrates. |

| Protein restriction | Reduction of dietary protein intake without changing the average caloric intake. |

| Amino acid restriction | Specific restriction of amino acids that commonly include threonine, histidine, lysine, methionine, and branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs). BCAAs have an aliphatic side chain, which is a carbon atom bound to at least two other carbon atoms.The three most common BCAAs are leucine, isoleucine, and valine. |

| Micronutrient restriction | Reduced intake of vitamins and minerals.Common micronutrients whose levels have been reduced by chemical chelation or inhibiting import are calcium, iron, zinc, phosphorus, and potassium. |

| Metabolite restriction | Reduction or inhibiting biosynthesis of specific reaction intermediates or end products of physiological metabolism. Most commonly: N-acylethanolamines, folate metabolism intermediates, polyunsaturated fatty acid metabolism intermediates, tricarboxylic cycle intermediates, and co-enzyme Q. |

Very-low-carbohydrate diet (<10%), low-carbohydrate diet (<26%), moderate-carbohydrate diet (<26%–44%); values based on human studies (Feinman et al., 2015)

Table 2.

Summary of dietary restriction (DR) regimens that promote lifespan

| Intervention | Species | Effects | Specified pathways | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total caloric restriction | yeast | ↑ chronological lifespan, ↑ stress resistance | SCH9, Msn2/Msn4 | Fabrizio et al., 2001 |

| ↑ replicative lifespan | TOR, SCH9 | Kaeberlein et al., 2005 | ||

| ↑ replicative lifespan | SIR2, NAD | Lin et al., 2000 | ||

| ↑ mitochondrial respiration, ↑ autophagy, ↓ translation | – | Kapahi et al., 2017 | ||

| worm | ↑ autophagy | PHA-4, TOR | Hansen et al., 2008; Kapahi et al., 2017 | |

| ↑ ER-UPR | – | Matai et al., 2019 | ||

| ↑ NMD and alternative splicing | – | Heintz et al., 2017; Rollins et al., 2019; Tabrez et al., 2017 | ||

| ↑ PUFA and cellular detoxification | MAPK | Chamoli et al., 2014, 2020; Heestand et al., 2013 | ||

| ↑ mitochondrial network and peroxisome remodeling | AMPK | Weir et al., 2017 | ||

| ↑ innate immunity | MAPK | Wu et al., 2019 | ||

| ↑ lifespan, ↓ ER stress | HIF1α | Chen et al., 2009 | ||

| fly | ↓ protein synthesis, ↑ stress resistance, ↑ lifespan | TOR, SIR2, FOXO | Kapahi et al., 2017 | |

| ↑ lifespan, ↑ fat metabolism | circadian clocks, timeless (tim) and period (per) | Katewa et al., 2016 | ||

| ↑ lifespan | olfaction pathway | Libert et al., 2007 | ||

| ↑ lifespan, ↑ mitochondrial function | 4E-BP | Zid et al., 2009 | ||

| mouse | ↑ lifespan (40% DR) | – | Blackwell et al., 1995 | |

| ↑ lifespan (30% DR) | neuropeptide Y | Chiba et al., 2014 | ||

| ↑ lifespan (40% DR) | SIRT1 | Mercken et al., 2014 | ||

| ↑ lifespan (30% DR) | BMAL1 and IGF1 | Patel et al., 2016a | ||

| ↑ lifespan (30% DR) | FOXO3 | Shimokawa et al., 2015 | ||

| ↑ lifespan (average and maximum) | – | Swindell, 2012; Weindruch and Sohal, 1997 | ||

| IF, EOD, PF, FMD | yeast | PF: ↑ median and maximum chronological lifespan | oxidative stress resistance | Brandhorst et al., 2015 |

| worm | IF: ↑ lifespan | RHEB-1, IGF, DAF-16 | Honjoh et al., 2009 | |

| fly | ↑ improved gut health | TOR independent | Catterson et al., 2018 | |

| mouse | EOD: ↑ lifespan by delay in life-limiting neoplastic disorders | – | Xie et al., 2017 | |

| periodic FMD: ↑ median lifespan, ↑ rejuvenated immune system, ↓ visceral fat, ↓ cancer incidence, ↓ skin lesions, ↓ bone mineral density loss | IGF-1, PKA | Brandhorst et al., 2015 | ||

| daily fasting: ↑ health, ↑ lifespan | – | Mitchell et al., 2019 | ||

| Glucose and carbohydrate restriction | yeast | ↑ replicative lifespan | NAD, SIR2 | Lin et al., 2000 |

| ↑ replicative lifespan, ↓ transcription and translation of methionine metabolism | – | Zou et al., 2020 | ||

| ↓ protein synthesis, ↑ replicative lifespan | GCN4 | Mittal et al., 2017 | ||

| ↑ replicative lifespan | 60S ribosomal subunit, GCN4 | Steffen et al., 2008 | ||

| worm | ↑ mitochondrial respiration | aak-2 | Schulz et al., 2007 | |

| fly | ↑ maximum lifespan, no change in mean lifespan | – | Troen et al., 2007 | |

| asparagine and glutamate | ||||

| restriction: ↑ chronological lifespan | Msn2, Msn4 | Powers et al., 2006 | ||

| methionine restriction and low amino acid | ||||

| status: ↑ replicative lifespan | TOR | Lee et al., 2014 | ||

| methionine restriction: ↑ autophagy-dependent vacuolar | ||||

| acidification, ↑ chronological lifespan | – | Ruckenstuhl et al., 2014 | ||

| methionine restriction and glutamic acid | ||||

| yeast | addition: ↑ chronological lifespan | – | Wu et al., 2013 | |

| worm | ↓ protein synthesis | TOR | Pan et al., 2007 | |

| fly | low-protein/high-carbohydrate diet (1:16), with constant calorie: ↑ lifespan | TOR | Jensen et al., 2015 | |

| ↑ lifespan, ↑ fatty acid synthesis and breakdown | AKH | Katewa et al., 2012 | ||

| low-protein/high-carbohydrate diet (1:16): ↑ lifespan | – | Lee et al., 2008 | ||

| developmental yeast restriction: ↑ lifespan | – | Stefana et al., 2017 | ||

| low-protein/high-carbohydrate diet (1:21), with constant calorie: ↑ lifespan | – | Fanson et al., 2009 | ||

| Protein/yeast restriction | mouse | low-protein/high-carbohydrate diet: ↑ hepatic mTORC1 | BCAA and glucose metabolism | Solon-Biet et al., 2014 |

| EAA or BCAA restriction | worm | dietary sulfur amino acid restriction: ↑ DICER in intestine | – | Guerra et al., 2019 |

| fly | BCAAs/threonine, histidine, and lysine (THK) diet: ↑ lifespan, ↓ age-related intestinal pathology | – | Juricic et al., 2020 | |

| balanced EAA level diet: ↑ lifespan | – | Grandison et al., 2009a | ||

| ↑ trans-sulfuration pathway | – | Kabil et al., 2011 | ||

| methionine restriction and low amino acid status: ↑ lifespan | TOR | Lee et al., 2014 | ||

| ↑ lifespan, ↑ regulation of ISCs and gut health, ↓ age-related gut pathology | SESTRIN | Lu et al., 2021 | ||

| mouse | methionine restriction: ↑ liver mRNA for macrophage migration inhibition factor, no change in lifespan in GH-deficient mice, ↓ serum IGF-I, insulin, glucose, and thyroid hormone | – | Miller et al., 2005 | |

| methionine restriction (0.16%): ↑ lifespan | GH | Brown-Borg et al., 2014 | ||

| lifelong restriction of BCAAs: ↑ lifespan in males, ↑ healthspan, ↓ frailty | TOR signaling in liver | Richardson et al., 2021 | ||

| EAA/non-EAA balance: ↑ lifespan, ↓ DR-induced muscle weakness, ↑ renoprotection | – | Yoshida et al., 2018 | ||

| rat | methionine restriction: ↑ mean and maximum lifespan | – | Zimmerman et al., 2003 | |

| tryptophan restriction: ↑ maximum lifespan | – | Ooka et al., 1988 | ||

| methionine restriction: ↑ lifespan of male | – | Orentreich et al., 1993 | ||

| methionine restriction: ↑ mean and maximum lifespan | GSH | Richie et al., 1994 | ||

| methionine restriction: ↑ maximum lifespan, ↓ mitochondrial ROS, ↓ oxidative damage to mitochondrial DNA and protein | – | Sanz et al., 2006 | ||

| Micronutrient/metabolite restriction | yeast | ↑ lifespan, ↓ K levels | vacuolar acidity | Sasikumar et al., 2019 |

| worm | ↑ lifespan, ↓ Fe levels | proteostasis | Klang et al., 2014 | |

| ↑ lifespan, ↓ Zn levels | DAF-16 | Kumar et al., 2016 | ||

| ↑ lifespan, ↓ co-enzyme Q | – | Larsen and Clarke, 2002 | ||

| ↑ lifespan, ↓ N-acylethano-lamine levels | PHA-4 | Lucanic et al., 2011 | ||

| ↑ lifespan, ↓ folate in HT115 3-dehydroquinate dehydratase | – | Virk et al., 2016 | ||

| fly | ↓ adenosine nucleotide biosynthesis, ↑ lifespan | AMPK | Stenesen et al., 2013 | |

| phosphate restriction: ↑ lifespan | – | Bergwitz, 2012 |

4E-BP, eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E-binding protein (4E-BP1 ortholog); aak-2, AMP-activated kinase 2 (AMPK ortholog); AKH, adipokinetic hormone; AMPK, adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase; BCAA, branched-chain amino acid; BMAL, brain and muscle ARNT-like 1; CR, caloric restriction; DAF-2, abnormal dauer formation 2 (IR/IGFR ortholog); DAF-16, abnormal dauer formation 16 (FOXO ortholog); EAA, essential amino acid; EOD, every-other-day fasting; ER, endoplasmic restriction; Fe, iron; FMD, fasting-mimicking diet; FOXO3, forkhead box O3; GCN4, general control nondepressible 4; GH, growth hormone; GSH, glutathione; HIF1α, hypoxia inducible factor 1 alpha; IF, intermittent fasting; IGF-1, insulin-like growth factor 1; IIS, insulin/IGF-1 signaling; ISCs, intestinal stem cells; JNK, c-Jun N-terminal kinase; K, potassium; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; Msn2/4, multiple suppressor of SNF1 mutation 2/4; NAD, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide; NPY, neuropeptide Y; PF, periodic fasting; PHA-4, defective pharynx development 4 (FOXA ortholog); PKA, protein kinase A; RHEB-1, Ras homolog enriched in brain (RHEB ortholog); ROS, reactive oxygen species; Sch9, serine/threonine protein kinase (S6 kinase ortholog); SIR2, silent information regulator 2 (SIRT1 ortholog); SIRT1, sirtuin 1; TOR, target of rapamycin (mTOR ortholog); UPR, unfolded protein response; Zn, zinc.

MOLECULAR MECHANISMS UNDERLYING DR

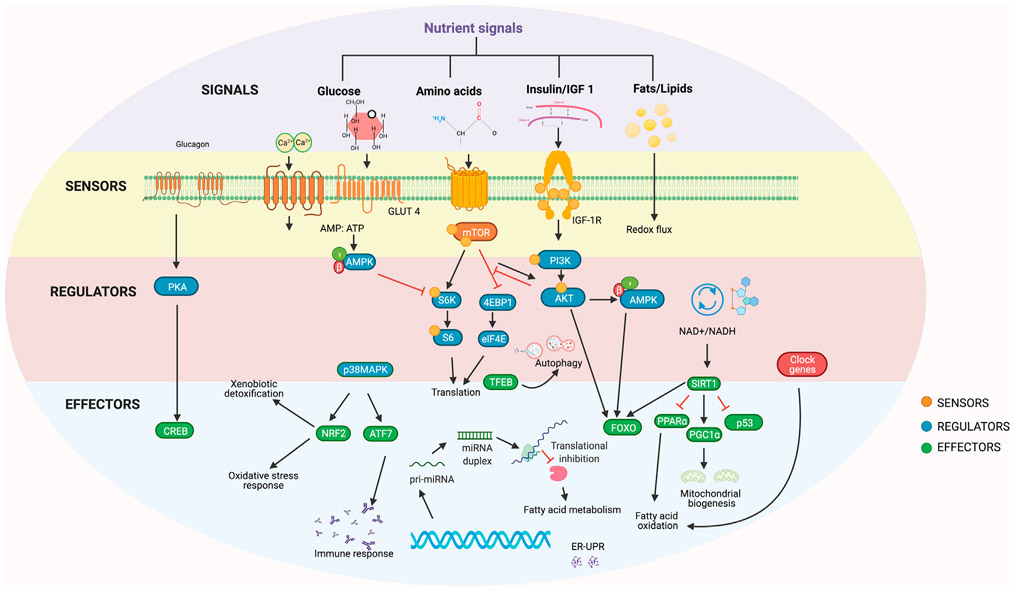

The conserved mechanisms that are generally considered universally responsible for the effects of DR on lifespan can generally be grouped into three categories (Table 2; Figure 1): (1) nutrient-sensing mechanisms, including sensory pathways that help assess an organism’s energy status; (2) DR-response regulators, including metabolic reprogramming mechanisms, which facilitate maintenance of alternative physiological states; and (3) effector mechanisms that mediate the downstream effects of DR to improve homeostasis.

Figure 1. Biochemical mechanisms of dietary restriction.

Nutrient signals (purple) are received by sensors at the cell membrane. These sensors (yellow) activate regulators (red) of diet-responsive mechanisms, which in turn regulate the effectors (blue) of stress response, cell growth, and metabolism.

Nutrient-sensing mechanisms

IGF-1-like signaling, TOR, and AMPK

Nutrients are central to an organism’s growth and reproduction. The evolutionary theory of aging suggests that when nutrient signaling is reduced, cellular growth and reproduction are halted and organisms switch to reducing damage and enhancing repair, which increases lifespan (Holliday, 1989); this theory has been experimentally demonstrated (Chen et al., 2007; Fanson et al., 2009). It is hypothesized that response to DR evolved as an adaptation to promote survival under nutrient-limiting conditions; however, a multitude of other hypotheses have also been proposed, such as that DR causes substantial biological remodeling which coincidentally extends lifespan and healthspan (Speakman, 2020), that DR is simply a laboratory artifact (Adler and Bonduriansky, 2014), or that the biological processes regulated by DR are too complex to point to specific mechanisms or pathways (Regan et al., 2020). These ideas are consistent with the finding that the inhibition of three major nutrient-sensing pathways (insulin/IGF-1-like signaling [IIS], target of rapamycin kinase [TOR], and AMP-kinase signaling) extends lifespan in multiple species ranging from yeast to mammals (Fontana and Partridge, 2015). In vertebrates, the IIS pathway responds to glucose with insulin secretion, which in turn binds to IIS receptors and regulates glucose levels by stimulating glucose uptake into muscle and fat and gluconeogenesis in the liver (Wilcox, 2005). The mTOR kinases comprise two distinct complexes, mTORC1 and mTORC2, which respond to extracellular and intracellular nutrient signals including amino acids, growth factors, stress signals, and oxygen to regulate growth and survival as well as protein and lipid synthesis (Papadopoli et al., 2019). Reduced mTOR activity extends lifespan in flies, worms, and yeast, which is not further extended by DR (Kapahi et al., 2004, 2010; Kauwe et al., 2016; Nicks et al., 2014). However, neither genetic modification of the TOR pathway nor treatment of rapamycin in Ercc1Δ/− mice is capable of granting lifespan extension similarly to DR in mice, suggesting that additional DR-mediated pathways are involved in this extension by DR (Birkisdóttir et al., 2021). AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) is a nutrient sensor molecule that is activated in response to a high AMP:ATP ratio, which reflects a cell’s energy status (Hardie et al., 2012). AMPK activation extends lifespan in multiple species (Fontana and Partridge, 2015; Greer et al., 2009; Kapahi et al., 2017). As an immediate response to low cellular energy levels, AMPK turns on catabolic pathways like glycolysis and fatty acid oxidation to replenish ATP levels (Kapahi et al., 2017; Lin and Hardie, 2018; Saxton and Sabatini, 2017). The complexity of this conserved nutrient-response pathway and the interplay between its components provide specific targets necessary to consider for precision nutrigeroscience.

Metabolic reprogramming regulators

Forkhead box O transcription factor (FOXO)

FOXO is a downstream effector of the IIS pathway that regulates metabolic homeostasis, stress response, cellular proliferation, and development (Calissi et al., 2021). The differential regulation of FOXO target genes and the pathways in response to varying environmental stimuli makes it a critical regulator of aging, but its role in DR is surprisingly not observed ubiquitously. In C. elegans, daf-16/FOXO is essential for some (but not all) DR protocols, including DR on solid-media growth plates and peptone dilutions (Greer and Brunet, 2009). Although not essential for DR-mediated lifespan, overexpression of dFOXO in the adult fat body in flies modulates DR response (Giannakou et al., 2008). In yeast, DR fails to extend the lifespan of FKH1 and FKH2 (FOXO orthologs) mutants (Postnikoff et al., 2012). In mammals, FOXO1’s mRNA levels and targets are elevated in skeletal muscles and the liver, while FOXO4 is upregulated in adipose tissue and skeletal muscles in mice subjected to DR (Furuyama et al., 2002; Kim et al., 2014; Miyauchi et al., 2019; Yamaza et al., 2010). Foxo3+/− and Foxo3−/− mice fail to show lifespan extension upon DR (Shimokawa et al., 2015). As such, some of DR’s beneficial effects on health and diseases were shown to be dependent on FOXO (Miyauchi et al., 2019; Yamaza et al., 2010). FOXO is also modulated by AMPK, sirtuins, and mTOR status (Greer et al., 2009). AMPK activation also directly phosphorylates and regulates FOXO3 transcriptional activity in mammalian cell cultures without affecting its nuclear localization (Greer et al., 2007b). Although the requirement of FOXO in regulating DR-mediated lifespan extension is well established, we still lack understanding of how FOXO regulates the gene-expression program essential for survival during DR. More importantly, identifying factors like post-translational modifications and protein partners, which regulate how FOXO signaling integrates signals originating from different environmental stimuli in vivo will be critical for understanding its role in DR. This necessitates more context-specific analysis of the role of FOXO.

Sirtuins and NAD

Sirtuins function as protein deacylases and are dependent on the levels of cellular co-enzyme nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+), a key currency of metabolism (Choudhary et al., 2014). Sir2 has been shown to modulate the DR-mediated lifespan extension in yeast (Kennedy et al., 1995; Lin et al., 2000), but in other species its role remains a matter of debate (Kaeberlein and Powers, 2007). However, Sir2 overexpression confers health benefits in other organisms including worms, flies, and mice (Chen et al., 2005; Lin et al., 2000; Tissenbaum and Guarente, 2001; Wood et al., 2004). In both worms and mammalian cells, Sir2 directly regulates transcriptional activity of DAF-16/FOXO by deacetylation, which activates FOXO-dependent transcription of stress-responsive genes and extends lifespan (Berdichevsky et al., 2006; Brunet et al., 2004). In hepatocytes, sirtuin activation increases nuclear translocation of FOXO1, leading to enhanced expression of FOXO1 target genes, including those relating to gluconeogenesis and glucose release (Frescas et al., 2005). In mice, deacetylation by hepatic Sir2/SIRT1 also regulates activity of transcription factor co-activator PGC-1α, which has emerged as a master regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis and function (Austin and St-Pierre, 2012). PGC-1α is prone to deacetylation and activation by SIRT1 when it is phosphorylated by AMPK at Thr177 and Ser538 (Cantó et al., 2009). However, other nuclear receptors and transcriptions also interact with and may recruit PGC-1α to the promoters of target genes that execute its metabolic effects, such as mitochondrial function and lipid oxidation in response to changes in nutrient fluctuation (Austin and St-Pierre, 2012).

NAD serves as a critical co-enzyme for redox reactions and as a co-factor for nonredox NAD+-dependent enzymes, including sirtuins, poly(ADP-ribose) polymerases (PARPs), and CD38 (Covarrubias et al., 2021). NAD+ levels decrease with age and multiple disorders, including metabolic diseases (Covarrubias et al., 2021). Thus, interventions boosting NAD+ levels have promising therapeutic potential in aging and age-related disease (Katsyuba et al., 2020). In this regard, DR is particularly beneficial as it increases NAD+ levels (Ramsey et al., 2009).

Circadian clock regulators

The circadian clock is an internal time-keeping system that helps maintain a 24-h rhythmic oscillation in behavior, physiology, and metabolism and is present across animals of different taxa (Green et al., 2008). The rhythmic activity of clock molecules regulates the cyclic transcription of many genes, which in turn synchronizes different cellular processes to environmental stimuli such as light. Deregulation of circadian rhythms is a major factor in aging and disease (Mattis and Sehgal, 2016). In addition to light, clock genes can derive cues from diet. DR enhances the amplitude of clock-gene mRNA expression in mice and fly models (Katewa et al., 2016; Patel et al., 2016b). Evidently, flies lacking core clock genes timeless (tim) and period (per) fail to show lifespan extension upon DR (Katewa et al., 2016). In mice, the clock transcription factor BMAL1 helps reduce blood IGF-1 levels during DR, and its absence prevents DR-mediated lifespan extension (Patel et al., 2016b). The role of clock genes in DR is an emerging area; however, how they couple with nutrient-response pathways remains to be understood. Mediators of DR, including SIRT1 and AMPK, also interact with circadian factors including BMAL1 (Lee and Kim, 2013). Studying the regulation of circadian clock genes in response to nutrient signals is challenging and requires extensive experimental analysis. Although few studies in plasma, muscle biopsies, and subcutaneous adipose tissue have been conducted (Grant et al., 2019), detailed sequential circadian transcriptomic and metabolomic analyses in several other human tissues are necessary to identify signatures of circadian metabolic function. Identifying signals and pathways that govern the variations in rhythmic molecules within individuals and how they impact health is essential for translational application of individualized circadian biology.

Non-coding RNAs

A significant proportion (~70%) of the human genome encodes non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs), which lack protein-coding potential but regulate transcription, stability, or translation of protein-coding genes (Bartel, 2009). MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are the most well studied of these ncRNAs and play central roles in metabolic pathways involved in nutrient sensing and aging (Victoria et al., 2017). Several miRNA families have been implicated in targeting mRNAs that code for components of the major nutrient-sensing pathways linked to aging, including insulin-IGF (Mariño et al., 2010; Zhu et al., 2011), mTOR (Dubinsky et al., 2014; Rubie et al., 2016), AMPK (Godlewski et al., 2010), and sirtuins (Lee et al., 2010; Menghini et al., 2009; Sharma et al., 2013). However, the relevance of the miRNA-mediated networks in promoting lifespan has not been evaluated at an organismal level for many of these miRNAs. Inappropriate expression of miRNAs and their processing factors has also been linked to many late-onset diseases and age-related functional decline (Chawla et al., 2016; Dimmeler and Nicotera, 2013; Liu et al., 2012). Additionally, the ability of miRNAs to circulate in body fluids (e.g., blood plasma, urine, tears, saliva, cerebrospinal fluid) as RNAse-resistant entities, either in extracellular vesicles or in vesicle-free form, highlights the utility of these biomolecules as noninvasive biomarkers for diagnosis and monitoring of aging and age-related diseases (Dhahbi, 2014; Turchinovich et al., 2012). In addition to specific miRNA biogenesis factors, factors that alter the access to the target site, sequence variants and single nucleotide polymorphisms in miRNAs or complementary recognition sequence may lead to creation, destruction, or alteration in the affinity of the miRNA-mRNA interaction (Sethupathy and Collins, 2008; Zorc et al., 2012). Hence, a better understanding of the role of miR-polymorphisms in response to different dietary interventions may aid in the development of population-specific or personalized nutrition-based strategies that are potentially safer. Several profiling studies have identified miRNA signatures that can be extensively correlated with lifespan interventions (Csiszar et al., 2014; Dhahbi, 2014; Masternak et al., 2004; Mercken et al., 2013; Mori et al., 2014; Pandit et al., 2014; Victoria et al., 2015) (Table 4). Emerging evidence also suggests that modulating miRNAs and their relevant targets influences lifespan (Pandey et al., 2021; Vora et al., 2013).

Table 4.

Summary of molecular biomarkers of aging that have been used in dietary restriction studies

| Biomarker | Model | Biological process | Biomarker criteria met |

Trend with DR |

Cells/tissues | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNA methylation | m, rm, h | epigenetic clocks | I, II, III, IV | ↑ | whole blood | Maegawa et al., 2017 |

| γH2A.X | h | genomic integrity | I, II, IV | ↓ | PBMCs | de Groot et al., 2015 |

| immunohistochemistry | m | lung | Li et al., 2020 | |||

| F2-isoprostanes | h | oxidative stress | I, II, III | ↓ | urine | Il’yasova et al., 2018 |

| miRNAs | r | post-transcriptional regulation of gene expression | I, II | ↑ | brain | Wood et al., 2015 |

| rm | I, II, III | ↑↓ | plasma | Schneider et al., 2017 | ||

| rm | I, II | ↑↓ | skeletal muscle | Mercken et al., 2013 | ||

| m | I, II | ↑ | adipose tissue | Mori et al., 2012 | ||

| m | I, II | ↓ | brain | Khanna et al., 2011 | ||

| M | I, II | ↑ | liver | Makwana et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2019 | ||

| m | I, II | ↑↓ | serum | Dhahbi et al., 2013 | ||

| Dm | I, II | ↑ | brain and fat tissue | Pandey et al., 2021 | ||

| Ce | I, II | ↓ | intestine | Vora et al., 2013 | ||

| Cortisol (glucocorticoid) | h | inflammation | I, II, III | ↑ | serum | Yang et al., 2016 |

| mTOR | r | nutrient sensing | I, II | ↓ | skeletal muscle | Chen et al., 2019 |

| SIRT1 | m | nutrient sensing | I, II, IV | ↑ | brain | Wahl et al., 2018 |

| h | muscle | Civitarese et al., 2007 | ||||

| IL-10 | m, h | immune signaling | I, II, IV | ↑ | hippocampus | Wahl et al., 2018 |

| h | serum | Jung et al., 2008 | ||||

| p16INK4A | m, r | cell senescence | I, II | ↓ | kidney | Krishnamurthy et al., 2004 |

| h | WI-38, IMR-90, and MRC-5 | Li and Tollefsbol, 2011 | ||||

| IL-6 | h | inflammation | I, II, III | ↓ | serum | Lettieri-Barbato et al., 2016; Reed et al., 2010 |

| Adiponectin/leptin | h | lipid metabolism | I, II, III | ↑ | serum | Lettieri-Barbato et al., 2016 |

| Dicer | m | miRNA processing | I, II | ↑ | preadipocytes | Mori et al., 2012 |

| c | intestine | Guerra et al., 2019 | ||||

| Protein carbonyls | h | oxidative stress | I, II, III, IV | ↓ | plasma | Meydani et al., 2011 |

| Protein carbonyls, ROS | m | I, II, IV | cerebral hemispheres | Dkhar and Sharma, 2014 | ||

| Protein carbonyls | brain | Forster et al., 2000 | ||||

| Insulin | h | insulin signaling | I, II, III, IV | ↓ | serum | Heilbronn et al., 2006 |

| h | plasma | Fontana et al., 2004 | ||||

| Insulin/IGF-I | h | serum | Lettieri-Barbato et al., 2016 | |||

| m | plasma | Sonntag et al., 1999 | ||||

| 8OHdG | m | oxidative stress | I, II | ↓ | skeletal muscle, brain, heart, kidney, liver | Donati et al., 2013; Ke et al., 2020; Sohal et al., 1994 |

| 8OHdG | r | oxidative stress | I, II, III | ↓ | urine | Donati et al., 2013 |

| DNA-PK | m | genomic integrity | I, II | ↑ | skin, brain | Ke et al., 2020 |

| LC3, HSP70, Beclin | h | autophagy, stress response | I, II, IV | ↑ | skeletal muscle | Yang et al., 2016 |

| LC3 | m | autophagy | SVF cells | Ghosh et al., 2016 | ||

| SA-β-gal | r | cellular senescence | I, II | ↓ | colon, heart | Fontana et al., 2018a, 2018b; Shinmura et al., 2011 |

| SA-β-gal | m, r | kidney | Krishnamurthy et al., 2004 | |||

| NF-κB | h | inflammation | I, II, IV | ↓ | skeletal muscle | Yang et al., 2016 |

| p-NF-κB | m | kidney | Mulrooney et al., 2011 | |||

| NF-κB | r | kidney | Xu et al., 2015b; Zhang et al., 2016a |

m, mouse; r, rat; rm, rhesus monkey; h, human; dm, Drosophila melanogaster; ce, C. elegans criterion I, an aging biomarker must predict the rate of aging; criterion II, an aging biomarker must monitor a basic process that underlies the aging process; criterion III, an aging biomarker must be able to be tested repeatedly without harming the person; criterion IV, an aging biomarker must be something that works in humans and in laboratory animals; PBMCs, peripheral blood mononuclear cells; mTOR, mechanistic target of rapamycin; SIRT1, sirtuin (silent mating type information regulation 2 homolog) 1; IL-10, interleukin 10; IL-6, interleukin 6; ROS, reactive oxygen species; 8OHdG, 8-hydroxy-2-deoxyguanosine; DNA-PK, DNA-dependent protein kinase; LC3, microtubule-associated proteins 1A/1B light chain 3B; HSP70, 70-kDa heat shock protein; SVF, adipose-tissue-derived stromal vascular fraction cells; SA-β-gal, senescence-associated beta galactosidase; NF-κB, nuclear factor kappa B; p-NF-κB, phosphorylated nuclear factor kappa B.

While the modulation of nutrient-responsive pathways and their regulators by nutrient restriction is well established, future research efforts focused on identification and validation of functional polymorphisms will be required for translating these findings into the development of personalized therapeutic strategies that could improve healthspan and treat late-onset diseases.

Effector mechanisms that mediate DR

Fat and lipid metabolism

Fat tissue is argued to have evolved to serve as an energy store, helping organisms counteract periods of starvation. Thus, fat metabolism is likely linked to DR. Increased fat deposition is a characteristic of aging in many organisms. Although increased fat deposit is correlated with insulin resistance, enhanced reliance on fat metabolism is often observed in long-lived mutants in the IIS and mTOR pathways (Caron et al., 2015; Hardy et al., 2012). Work in Sirt1+/− mice and in cell culture reveals that Sirt1 promotes fat mobilization in white adipocytes by repressing genes controlled by the fat regulator PPARγ (Picard et al., 2004). AMPK also regulates lipid metabolism through the phosphorylation of acetyl-CoA carboxylase 2 (ACC2) (Merrill et al., 1997). One important caveat of triglyceride measurements is that steady-state triglyceride levels are often reported, but not the flux analysis, which is more reflective of physiological function. Importantly, studies in nutrient restriction in flies and mice using tracers show an increase in both fat synthesis and breakdown, suggesting a switch toward triglyceride utilization (Bruss et al., 2010; Katewa et al., 2012). Inhibition of triglyceride synthesis by inhibition of acetyl-CoA carboxylase or mitochondrial beta-oxidation results in a loss of DR-dependent lifespan extension (Katewa et al., 2012). In flies, enhanced expression of clock genes drives fatty acid oxidation and breakdown in peripheral tissues (Katewa et al., 2016). In worms, the inhibition of genes regulating fatty acid oxidation, synthesis, and desaturation, such as nuclear hormone receptors NHR-49/PPAR-α and NHR-80/HNF4, is essential for DR-mediated longevity and ameliorates proteotoxic effects in polyQ Huntington’s models (Marcellino et al., 2018; Van Gilst et al., 2005). The increased abundance of desaturated mono- and polyunsaturated fatty acids during DR is an essential component of cell membrane structure and has been shown to upregulate prosurvival mechanisms such as cellular detoxification (Chamoli et al., 2020). These studies suggest that enhanced rates of fatty acid synthesis and breakdown are both important regulators of DR-mediated longevity, and caution should be taken when measuring the effects of DR on fatty acid metabolism. Techniques that measure lipid turnover using radiolabeled nucleotides from nuclear testing have helped measure the fat-turnover rate in humans, showing that low levels of lipid turnover are associated with unhealthy metabolic outcomes (Arner et al., 2011). Together, this suggests the importance of measuring flux analysis rather than steady-state fat levels as well as the role of genotype in assessing the contribution of fat metabolism in mediating the protective effects of DR.

Proteostasis and autophagy

Many proteins become insoluble and accumulate with age, which contributes to disease (Kaushik and Cuervo, 2015). Several of these proteins are determinants of lifespan, as their inhibition increases lifespan in C. elegans (Reis-Rodrigues et al., 2012). Whether interventions like DR could delay such global changes with accumulation of age-related insoluble proteins is yet to be determined, but evidence suggests that DR improves protein homeostasis. Work in C. elegans suggests that DR extends lifespan by inducing ER hormesis and maintaining proteostasis (Matai et al., 2019). A critical component of proteostasis is the timely degradation of toxic protein buildups, which largely requires autophagy (Chen et al., 2011), which is activated in response to nutrient scarcity (Russell et al., 2014). Many genes related to autophagic machinery are shown from yeast to humans to be essential for longevity and healthspan benefits with DR (Hansen et al., 2008; Most et al., 2017). For example, eat-2 mutants in C. elegans, a genetic model of DR, show enlarged acidic lysosomal compartments and enhanced autophagic flux, which is important for maintaining intestinal barrier function and extending lifespan (Gelino et al., 2016). Similarly, livers from mice undergoing 40% caloric restriction for 4 months have shown increased autophagic flux, measured by LC3-II/LC3-I ratio (Luévano-Martínez et al., 2017). In humans undergoing 30% CR from 3 to 15 years, autophagy genes such as LC3 and beclin are increased in skeletal-muscle biopsy samples (Yang et al., 2016). Autophagy is also important for mediating coordinated metabolic response to DR and food availability by mobilizing stored lipids via lipophagy (Singh and Cuervo, 2012). The autophagic response to DR is also, in part, mediated by inhibition of mTOR activity and upregulation of AMPK (Meijer et al., 2015) and SIRT1 activity (Farina et al., 2015). There is an intricate relationship between DR and autophagy, which ought to be better elucidated in different tissues and under different forms of DR.

Mitochondrial function

Mitochondrial function is critical for many biological processes. As such, defective mitochondrial function underlies aging and many age-related diseases (López-Otín et al., 2013). Many interventions that extend healthspan or lifespan, including DR, do so by altering mitochondrial function and quality-control mechanisms (Quiles and Gustafsson, 2020). However, there is no clear consensus as to how DR alters mitochondrial function to improve mitochondrial homeostasis and extend lifespan. In addition to variation in the experimental procedures, such as in the study design, timing of experimental readouts, and approaches used to study mitochondrial function, genetic variation could also explain these discrepancies. Several studies claim that reduced mitochondrial activity generates low ROS and thus there is less ROS-induced damage during DR (Pamplona and Barja, 2006). For example, mitochondria of the primary hepatocytes isolated from ad libitum (AL) and 40% CR rats (3–12 months) show reduced oxygen consumption, reduced membrane potential, and generation of less ROS while maintaining their critical ATP production, suggesting increased mitochondrial efficiency under CR (López-Lluch et al., 2006). The techniques used to produce these findings were unique, however, using cultured serum from animals undergoing CR, which could thus be a cause for these interesting findings (López-Lluch et al., 2006). Short-term CR in humans induces the formation of “efficient mitochondria” in skeletal muscle by inducing biogenesis of mitochondria that consume less oxygen, thus inducing reduced oxidative stress, though no enzymes typical of mitochondrial function were found to be increased in these tissues (Civitarese et al., 2007). Despite these differences in oxygen consumption rate, DR has been reported to show consistent effects on transcriptional upregulation of mitochondrial genes in multiple studies and models (López-Lluch et al., 2006; Nisoli et al., 2005; Pamplona and Barja, 2006; Zid et al., 2009).

The beneficial effects of increased mitochondrial oxygen consumption rate are well supported by the concept of mitohormesis. The initial transient upregulation of mitochondrial ROS during DR may lead to increased mitochondrial activity, which explains sustained reduced ROS under DR conditions (Sohal and Forster, 2014). This transient ROS induction upregulates cellular defense mechanisms, thus extending lifespan in C. elegans (Schulz et al., 2007). Similar to this, mitochondrial stress caused by the imbalance of mitonuclear protein, proteotoxicity, and loss in mitochondrial fitness may trigger the mitochondrial unfolded protein response (mtUPR) or other mitochondrial homeostasis mechanisms (Houtkooper et al., 2013; Naresh and Haynes, 2019). In worms, mtUPR contributes to extended longevity caused by an alteration in electron-transport chain components (Durieux et al., 2011). Growing evidence also demonstrates that DR may reduce damage caused to mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) (Lam and McKeague, 2019). In mammals, DR induces expression of several mitophagy-related markers, such as PINK1, Parkin, ubiquitin, and p62/LC3-II (Mehrabani et al., 2020), suggesting enhanced turnover of damaged mitochondria.

We postulate that under DR there is a switch in substrate utilization toward fatty acids that reduce ROS production through a variety of mechanisms. Due to differential entry points into the mitochondrial electron-transport system (ETS), for example, the reducing equivalents from fatty acids in beta-oxidation enter the ETS via electron transfer flavoprotein: ubiquinone oxidoreductase (ETF:QO; oxidizing FADH2) and the electrons are deposited to ubiquinone, thereby bypassing complex I, a major site of ROS production. On the other hand, under a rich diet, reducing equivalents from carbohydrates directly enter complex I, producing more ROS (Guarente, 2008). Altogether, evidence suggests that mitochondrial metabolism plays an essential role in DR-mediated longevity. However, studies that account for variation (genetic, age, sex) within and across species are required to understand the extent to which nutrient limitation impacts mitochondrial function in different tissues in the context of aging.

Reduction of cellular senescence and toxic molecules that enhance inflammation

DR also reduces proinflammatory molecules that build up with age by reducing senescent cell markers and associated inflammation in mouse and human tissues (Fontana et al., 2018a; Wang et al., 2010). Cells can become senescent in response to a wide range of stresses, such as genotoxic or oxidative stress, metabolic dysfunction, mitochondrial stress, epigenetic changes, oncogene induction, or loss of tumor-suppressor genes (McHugh and Gil, 2018). DR has been shown to reverse or prevent the negative impacts of many of these stresses and thus reduce the accumulation of senescent cells. These mechanisms include enhanced clearance of damaged mitochondria by autophagy (Ruetenik and Barrientos, 2015), reduced oxidative stress and ROS production (Walsh et al., 2014), and enhanced activity of DNA repair mechanisms (Cabelof et al., 2003) by DR.

Healthy, nonobese human adults undergoing 25% CR for up to 24 months also show reduced proinflammatory markers (C reactive protein, TNF-α, leptin, ICAM1) (Meydani et al., 2016). Among the multiple mechanisms proposed, reduced visceral adiposity associated with IL-6 (Fontana et al., 2007) and changes in adipokines (leptin and adiponectin) influence DR-mediated pleiotropic effects on metabolism and systematic inflammation (Carbone et al., 2012). DR reduces lipotoxic molecules, including acetyl carnitines that accumulate due to reduced beta-oxidation in nonadipose tissues, which drives insulin resistance (Yechoor et al., 2002). Recent advances in the field have recognized prominent roles for the gut microbiome and the metabolites it secretes in shaping immune health (Zhang et al., 2021). In this context, DR is likely to have a huge impact, as the gut microbiome is significantly affected by diet (von Schwartzenberg et al., 2021).

Neurogenesis

CR is reported to delay age-related cognitive decline in complex mammals including humans (Witte et al., 2009). Although detailed mechanisms of how DR prevents cognitive decline are yet to be discovered, one possible mechanism is linked to enhanced neurogenesis and neuron survival (Bondolfi et al., 2004). Age-related structural changes in neurogenesis sites in the dentate gyrus subventricular zone (SVZ) and subgranular layer (SGL) are associated with fewer neuroblasts and progenitor cells and less cell proliferation (Luo et al., 2006). Interestingly, 3 months of alternate-day DR in 8-week-old mice increased cell survival in the dentate gyrus compared with normally fed mice (Lee et al., 2002). DR animals were also found to have increased brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and neurotrophin-3 (NT-3) (Lee et al., 2002). Alternate-day DR enhanced survival of newly generated dentate gyrus cells in 3-month-old rats, suggesting enhanced neurogenesis (Lee et al., 2000). Similarly, 40% CR in mice initiated at 16 weeks of age prevented age-related loss in neurogenesis. Only young mice (6–7 months old) undergoing CR showed increased proliferation of neural stem cells and progenitor cells, whereas aged mice (12–18 months) undergoing CR showed reduced proliferation despite having neurogenesis equivalent to that of young mice. This contrast has been attributed to either increased survival of newborn neurons or a switch in cell fate to astrocytes, a mechanism seen in the hippocampus (Encinas et al., 2011). These studies further demonstrate how context-specific measurements, which take into consideration age and form of DR, are necessary to determine how it influences neurogenesis with age.

COMPLEXITIES OF MEASURING AGING IN RESPONSE TO DR

Most of the studies delineating the protective effects of DR on aging use lifespan as their metric to measure aging. However, to best assess how dietary interventions can be optimized to improve longevity, it is essential to determine the appropriate means to assess aging. The gold-standard measurement in studies that examine DR is the survival rate of a population over time. However, these lifelong measurements are often reduced to a single metric, such as mean, median, or maximum lifespan, and a change in these values is used to assess the impact of treatments (Grandison et al., 2009b). These approaches do not consider the heterogeneity in how individuals in a population with identical genotypes age and also do not give insight into when or how DR alters mortality. Determining the impact of DR on an organism’s mortality risk is an alternative approach that has been used to help elucidate its effects (Cheng et al., 2019; Good and Tatar, 2001; Mair et al., 2003).

Mortality curves, which can be represented by initial mortality (α) and rate of aging (β), have been extensively utilized to quantify aging in DR studies of many organisms (Colman et al., 2009; Good and Tatar, 2001; Gordon-Dseagu et al., 2017; Mair et al., 2003; Simons et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2016b; Zhao et al., 2017b). The species- and genotype-specific impacts of DR previously mentioned have similar variability in their impact on these parameters. In flies, for example, DR decreases mortality rate in a genotype-specific manner, as shown by the varying response across 11 Drosophila Genetic Reference Panel (DGRP) lines (McCracken et al., 2020). A study measuring the role of dietary sugar modulation in Ceratitis capitata has shown mixed results on mortality, with no significant effects of diet on “active life expectancy,” or the fraction of a fly’s life before becoming supine, despite a large impact on total lifespan (Papadopoulos et al., 2011). However, a more recent study showed significant β changes upon dietary alterations in the same species (Papanastasiou et al., 2019). Importantly, the impact of DR on mortality is conserved in mammals, though results have been variable. For example, while a meta-analysis in rodents found that only β was significantly decreased on DR (Simons et al., 2013), studies in mice revealed a decreased β and an increase in α upon DR (Garratt et al., 2016). Another recent study found a slight decrease in β for mice on DR compared with ad libitum feeding and further showed that a late-onset diet change had stronger initial effects on mortality going from DR to ad libitum than the reciprocal, though the difference disappeared over time (Hahn et al., 2019). In humans, the role of dietary macronutrients in mortality is complex; mortality risk follows a U-shaped association with dietary carbohydrate composition (Seidelmann et al., 2018), and fat consumption leads to either higher (animal fats) or lower (plant-based fats) mortality (Seidelmann et al., 2018). These differences highlight the variability in genetic response to DR, and the ability of mortality analyses to give more granular insight into the species- and genotype-specific nature of DR. The independent nature of each data point in a mortality curve allows for more flexibility and creativity when designing DR studies (Cheng et al., 2019). Incorporating mortality-rate analysis will shed light on dissecting the aging measures impacted by DR-related longevity mechanisms to better assess how individualized treatments can be applied.

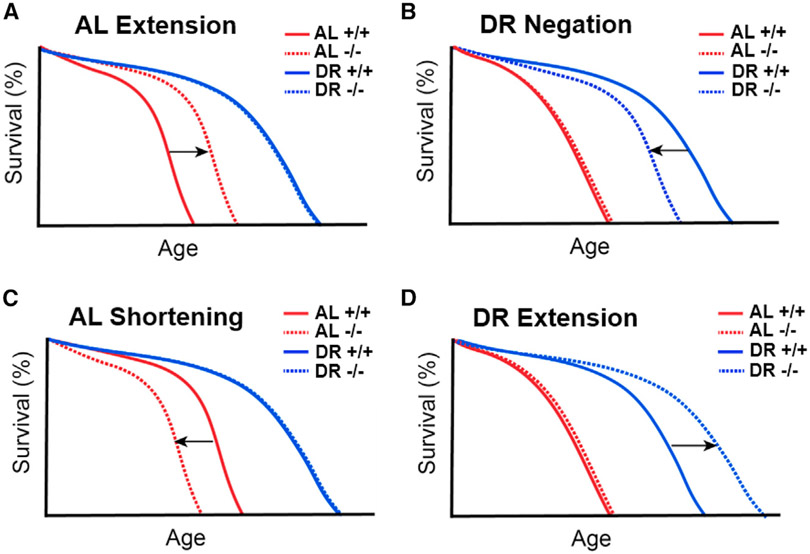

Different classes of diet-responsive genes using mortality analysis to decipher mechanisms of DR

Deciphering the genetic mechanisms of DR responses has classically relied on using mortality curves as an output in response to both dietary and genetic perturbations. Four phenotypic classes have been described to identify genetic perturbations which mediate lifespan changes under ad libitum or DR. The first class is lifespan extension in mean or median lifespan upon ad libitum conditions, but not DR (Figure 2A), as has been seen upon downregulation of genes in the mTOR and insulin/IGF-1 pathways in flies (Kapahi et al., 2017). In the second class, lifespan is shortened specifically upon DR but not under ad libitum conditions (Figure 2B), as has been shown with loss of SIR2 in yeast, AMPK in worms, or 4E-BP or IRE1 in flies (Greer et al., 2007a; Lin et al., 2000; Luis et al., 2016; Zid et al., 2009). These proteins likely regulate the genes that mediate the protective effects of DR. In a third, less examined class, gene knockout shortens lifespan specifically on a rich diet but not on DR (Figure 2C). This is seen upon loss of the urate oxidase gene in flies, which leads to the accumulation of purines (Lang et al., 2019). These genes are likely to regulate pathways that impact the buildup of toxic products on a rich diet but not on DR. Such genes have the potential to limit lifespan and enhance age-related diseases, especially on a rich diet (Lang et al., 2019). Another example of this is that mice deficient in the DNA excision-repair gene 1 Ercc-1 show a tripling of lifespan under CR, suggesting that the buildup of specific DNA damage is detrimental to lifespan in a diet-dependent manner (Vermeij et al., 2016). Additionally, the glyoxalase gene knockout results in accumulation of advanced glycation endproducts (AGEs) in C. elegans (Chaudhuri et al., 2016). This shortens lifespan, which is rescued under a fasted state. In the fourth class, a gene modulation extends lifespan upon DR, but not a rich diet (Figure 2D). One example is observed in yeast where, paradoxically, loss of Sir2 in combination with CR enhances survival under stress and starvation and has opposite effects on chronological lifespan and replicative lifespan (Fabrizio et al., 2005). These cases signify the complex relationship between DR and the genes it regulates, suggesting that further analysis is necessary to determine how modifying a specific molecular mechanism might influence longevity in different dietary contexts. Future genotype-diet interaction studies that take into account all four possibilities and their combinations would reveal further insights into how aging is modulated by diet-responsive pathways. Furthermore, in addition to using mean and median changes in lifespan, accounting for the mortality parameters α and β throughout lifespan will be instrumental in understanding which genetic pathways influence mortality parameters and age-related decline in biological function.

Figure 2. Possible gene-specific lifespan responses to dietary interventions.

Loss of a gene can lead to one of four general responses:

(A) Lifespan extension on a nutrient-rich diet, but no effect under DR.

(B) Negation of typical DR-mediated lifespan extension, but no effect on a nutrient-rich diet.

(C) Lifespan shortening under nutrient-rich conditions, but no effect under DR.

(D) DR-specific lifespan extension, but no effect under nutrient-rich conditions.

Genotype-dependent variation in responses to DR

Genetic variations in APOE and FOXO3 are known to influence the risk of age-related disease and overall mortality in humans (Broer et al., 2015; Carr et al., 2018); however, human variants for response to DR have not been identified. These genetic variations strongly influence responsiveness to DR, and thus are of paramount importance in studying precision nutrigeroscience. Studies using mice have found that not all strains tested had increased lifespan with one specific level of CR (Liao et al., 2010) and that fertility with CR also varied greatly between strains (Rikke et al., 2010). Although one form of CR is not necessarily expected to be beneficial for all genetic backgrounds and though only ~10 mice were tested for each diet, it was surprising that some strains performed poorly upon CR. We previously demonstrated that genotype influences DR responses such as starvation resistance, body mass, triglyceride levels, protein levels, and glucose levels by using the DGRP fly strains (Nelson et al., 2016). Following characterization of these strains, we used genome-wide association studies (GWAS) for the above physiological traits and found that genes associated with ceramide synthase activity, the fly huntingtin gene, and a previously uncharacterized gene, heavyweight, influenced body mass under ad libitum conditions and starvation resistance upon DR (Nelson et al., 2016). Further work with the DGRP revealed how DR impacts longevity and climbing ability. While decline in climbing ability with age was slowed by DR in nearly all strains, lifespan was not ubiquitously improved, with ~20% of strains having shorter lives under DR. We also showed that strains of flies prone to longer life under ad libitum conditions performed worse under DR (Wilson et al., 2020). Additional work utilizing the DGRP highlights how genotype-diet interactions can lead to metabolomic variability (Jin et al., 2020). While these studies uncovered new diet-responsive genes that influence lifespan (such as decima), healthspan (such as daedalus), and the metabolome (such as CCHa2-R), these findings were limited by only using measures for mean or median lifespan. Future studies to determine the effects of DR in various genotypes will require methods that capture its effects over the entire lifespan, such as mortality rates, to best determine how and when to apply diet-based therapeutic strategies.

Sexual dimorphism in the lifespan response to DR

Sex-specific differences in lifespan have been reported in many species, including humans (Gordon et al., 2017). Similarly, aging interventions such as DR also have disparate effects based on sex (Wu et al., 2020). In humans, reproductive rates have been linked to nutrient availability, and reproductive activity is shown to be negatively correlated with lifespan in some cases (Jasienska et al., 2017). Women with reduced reproduction trend toward a longer lifespan, whereas this effect is not seen in men (Bolund et al., 2016). Females display a stronger response to this reproduction-longevity trade-off largely owing to the differences in reproductive burden (Travers et al., 2015). Reduced dietary protein relative to carbohydrates can also maximize lifespan, but this is not optimal for reproduction, a response that is variable by genotype and sex (Jensen et al., 2015). It is noted that mice that are prone to lifespan extension with DR are also prone to increased litters (Rikke et al., 2010). This group further recognized genotype and sex-genotype interactive differences in lifespan and body fat (Liao et al., 2010,2011). Others have linked nonreproductive reasons to sexual disparity in diet response, such as differences in intestinal strength under DR in sheep, and noted that inducing femalelike pathology in the male gut intestine is capable of extending life (Regan et al., 2016). In rhesus macaques undergoing CR, females showed higher early-life mortality than males noted to be due to endometriosis, whereas males showed reduced serum cholesterol with age compared with females (Mattison et al., 2012). Overall, the outcomes and optimal dosage of DR differ by sex and by strain (Mitchell et al., 2016), which necessitates study into the best means to treat different sexes with DR-based treatments.

Healthspan versus lifespan debate

Though it is often assumed that lifespan extension is accompanied by healthspan extension, recent work has called this relationship into question. This debate has created two schools of thought: one which focuses on lifespan extension as the most relevant metric for slowing aging and another which uses functional changes in aging measured by healthspan metrics. One challenge in determining healthspan, however, is how to best assess this in model organisms. In humans, walking speed is often used for this (Freedman et al., 2002), though its role as a predictor of mortality is questionable (Studenski et al., 2011) because most aged humans have multiple disabilities, imposing frailty by different means (Clegg et al., 2013). Nonetheless, the period of overall functionality is used as a measure for determining overall healthspan in model organisms, particularly in response to DR. Work in C. elegans focusing on known DR-related genes such as eat-2, which restricts dietary intake in worms, and daf-2, which inhibits IGF signaling, demonstrated that lifespan extension is not necessarily accompanied by similar healthspan extension, as assessed by oxidative stress, heat resistance, and overall movement (Bansal et al., 2015), suggesting an uncoupling of lifespan and healthspan. Others, however, have analyzed functionality measures differently, such as recording movement decline relative to maximum velocity, to suggest a correlation between lifespan and healthspan in the same daf-2 mutant used in the previous study (Hahm et al., 2015). Still others continue to find no evidence of correlation between health and longevity in multiple species (Podshivalova et al., 2017). In flies, we found no correlation between measures of lifespan and healthspan in response to DR across 160 wild strains, and DR extended healthspan more consistently than lifespan (Wilson et al., 2020). We further identified genes that regulated lifespan specifically (decima) or climbing ability specifically (daedalus) in response to diet. We found that DR alters body mass and other metabolic traits (Nelson et al., 2016), but these also did not correlate with lifespan (Wilson et al., 2020). The potential separation between lifespan and health factors has also been observed in more complex mammalian systems. Work in mice has suggested aging interventions that improve healthspan or lifespan but not both conjunctively, notably with the result that downregulation of mTOR activity extended lifespan but did not affect hepatic function or insulin sensitivity (Lamming et al., 2012). Healthspan may be improved without extending lifespan with dietary optimization to incorporate nicotinamide (Mitchell et al., 2018). More recently, knockout of the stress-response gene Nrf2 resulted in reduced stress-response activation, but there was no effect on lifespan or physical performance in mice undergoing CR, further suggesting a range of potential health-related responses to CR (Pomatto et al., 2020). CR primate models also demonstrate a potential uncoupling of healthspan and lifespan in response to dietary modulation across studies; one study demonstrated benefits in healthspan measures such as triglyceride levels and disease onset as well as lifespan (Mattison et al., 2017), whereas another using a different CR regimen showed that there is an improvement in the same health measures, but not lifespan (Mattison et al., 2012), suggesting compression of morbidity but not extended lifespan. However, measurements of body mass also indicated no change between CR and control primates, suggesting that the implementation of CR in these animals may have contributed to the lack of change in lifespan (Mattison et al., 2012). These studies also emphasize the importance of diet composition when considering how DR might influence longevity and healthspan. Humans consuming reduced red meat and trans fats showed increased longevity and healthspan on average, but there was a notable compression of morbidity later in life (McCullough et al., 2002). These findings have led to the recommendation that both healthspan and lifespan traits be measured in all age-related studies to better report which interventions improve healthspan and which improve lifespan (Richardson et al., 2016). Furthermore, genotype- and environment-specific factors may also provide critical context as to how aging is driven and how age-related diseases develop. Given the heterogeneity in aging across tissues and genotypes, perhaps observing specific individuals to understand how they age is more effective than using generalized means to determine how aging influences the individual.

DR in tissue aging and disease

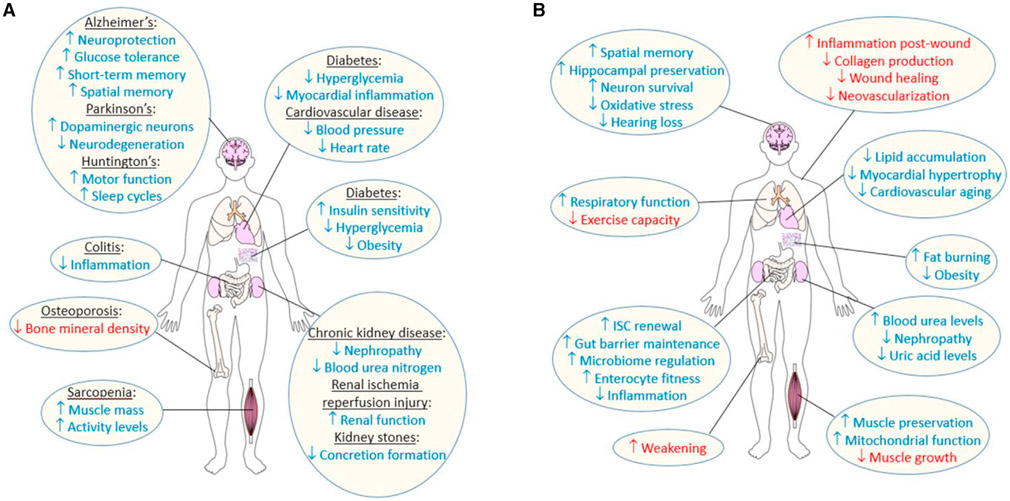

Considering that diet-responsive molecular pathways are present in all cells, one might assume that DR-derived benefits would be beneficial in all tissues of a single organism. However, DR impacts tissue aging in multiple ways and to different degrees (Figure 3) and has various effects on DR-treated disease models (Table 3), complicating how DR can be used to broadly treat age-related decline. Here, we detail how DR impacts tissues and age-related diseases, which must be considered when investigating individualized DR-based treatments.

Figure 3. Reported effects of DR on human tissues in disease and normal aging.

(A) Reported benefits and detriments of DR under different disease states in the brain, intestine, bone, muscle, heart, fat stores, and kidneys.

(B) Benefits and detriments of DR under normal tissue aging. Benefits are shown in blue, detriments in red. See text for details.

Table 3.

Effects of DR on disease models

| Disease | DR regimen |

Species | Model | Effect | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diabetes | MR | mouse | NZO | ↑ insulin sensitivity, ↑ energy expenditure | Castaño-Martinez et al., 2019 |

| PR | mouse | NZO | ↓ hyperglycemia, ↓ β cell loss | Laeger et al., 2018 | |

| CR | mouse | db/db | ↑ insulin sensitivity, ↑ β cell mass, ↑ utilization of fatty acids, ↓ apoptosis, ↓ oxidative stress, ↓ myocardial inflammation, ↓ fibrosis, ↓ inflammation | Cohen et al., 2017; Kanda et al., 2015; Waldman et al., 2018 | |

| CR and IF | mouse | NZO | ↑ protection against hyperglycemia, ↓ diacylglycerol in liver | Baumeier et al., 2015 | |

| Cardiovascular disease | CR | rat | SHROB | ↓ blood pressure, ↓ heart rate, ↓ weight | Ernsberger et al., 1994 |

| CR | mouse | db/db | ↑ iron homeostasis, ↓ myocyte hypertrophy, ↓ inflammation, ↓ fibrosis, ↓ oxidative stress | An et al., 2020 | |

| CR | mouse | ob/ob | ↑ iron homeostasis, ↓ myocyte hypertrophy, ↓ inflammation, ↓ fibrosis, ↓ oxidative stress | An et al., 2020 | |

| Colitis | MR | mouse | colitis by DSS treatment | ↑ ROS response, ↓ inflammation | Liu et al., 2017 |

| CR | mouse | colitis by trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid | ↑ balanced immunoregulation, ↓ colitis | Shibolet et al., 2002 | |

| Renal ischemia reperfusion injury | CR and PR | mouse | bilateral induction of renal ischemia reperfusion | ↑ protection from injury post-reperfusion | Robertson et al., 2015 |

| CR and STF | mouse | bilateral induction of renal ischemia reperfusion | ↑ renal function, ↑ protection against injury post-reperfusion, ↓ inflammation | Shushimita et al., 2015 | |

| Kidney stones | PR and PuR | fly | hyperuricemia by urate oxidase RNAi | ↓ concretions in malpighian tubule | Lang et al., 2019 |

| Alzheimer’s disease | PR | fly | arctic mutant Aβ42 and 4R tau overexpression | ↑ lifespan, no neuronal benefits | Kerr et al., 2011 |

| IF | rat | ovariectomized β-amyloid-infused | ↑ glucose tolerance, ↑ fat loss, ↑ short-term and spatial memory | Shin et al., 2018 | |

| IF | mouse | App NL-G-F | ↓ neuronal hyperexcitability, ↓ hippocampal synaptic plasticity deficits | Liu et al., 2019 | |

| IF | mouse | 5xFAD | ↑ brain inflammation, ↑ neuronal injury | Lazic et al., 2020 | |

| CR | yeast | expression of human α-synuclein | ↓ α-synuclein-related toxicity | Sampaio-Marques et al., 2018 | |

| CR | mouse | APPswe/ind | ↓ amyloid-β accumulation, ↓ astrocyte activation | Patel et al., 2005 | |

| CR | mouse | APPswe+PS1M146L | ↓ amyloid-β accumulation, ↓ astrocyte activation | Patel et al., 2005 | |

| CR | mouse | Tg2576 | ↓ neurite plaques, ↓ amyloid-related pathology, ↓ cognitive deficits | Schafer et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2005 | |

| CR | mouse | dtg APP/PS1 | ↓ neuropathy | Mouton et al., 2009 | |

| CR | mouse | Tg4510 | ↓ memory deficits | Brownlow et al., 2014 | |

| CR | mouse | APOE knockout | ↑ neuroprotection | Rühlmann et al., 2016 | |

| CR | mouse | hTau | ↑ tauopathy | Gratuze et al., 2017 | |

| CR | mouse | PDAPP-J20 | ↓ cognitive deficits, ↓ amyloid-β-related pathology | Gregosa et al., 2019 | |

| IF and CR | mouse | 3xTgAD | ↑ spatial memory, ↑ exploratory behavior | Halagappa et al., 2007 | |

| Parkinson’s disease | IF | rat | 6-OHDA-induced | no effects | Armentero et al., 2008 |

| CR via bacteria dilution | worm | 6-OHDA-induced | ↓ dopaminergic neuron degeneration, ↓ microglial activation | Jadiya et al., 2011 | |

| CR | monkey | MPTP-induced | ↑ striatal dopamine | Maswood et al., 2004 | |

| CR | mouse | MPTP-induced | ↑ dopaminergic neuron protection, ↓ dopaminergic neuron degeneration | Bayliss et al., 2016; Duan and Mattson, 1999 | |

| Huntington’s disease | EODF | mouse | N171-Q82 | ↑ BDNF in striatum and cortex, ↑ hsp70 in striatum and cortex | Duan et al., 2003 |

| CR | mouse | YAC128 | ↑ improved body weight, ↑ improved blood glucose, ↑ motor function, ↑ Hdac2 regulation | Moreno et al., 2016 | |

| TRF | mouse | Q175 | ↑ locomotor activity, ↑ sleep cycles, ↓ heart rate variability | Wang et al., 2018 | |

| Cancer | MR | mouse | Yoshida sarcoma transplantation | ↓ metastasis | Hoffman and Stern, 2019 |

| MR | mouse | breast carcinoma transplantation | ↑ efficacy of cisplatin | Hoffman and Stern, 2019 | |

| MR | rat | Yoshida sarcoma transplantation | ↑ efficacy of doxorubicin, ↑ efficacy of vincristine | Hoffman and Stern, 2019 | |

| PR | mouse | GL26 glioma implantation | no effects on tumor growth | Brandhorst et al., 2013 | |

| PR | mouse | LuCaP23.1 prostate cancer xenograft model | ↓ tumor growth | Fontana et al., 2013 | |

| PR | mouse | WHIM16 breast cancer xenograft model | ↓ tumor growth | Fontana et al., 2013 | |

| PR | mouse | C57B/6 with RP-B6-Myc prostate tumor transplantation | ↑ response to immunotherapies, ↑ proinflamma-tory phenotypes, ↓ tumor growth | Orillion et al., 2018 | |

| PR | mouse | C57B/6 with RENCA tumor transplantation | ↑ response to immunotherapies, ↑ proinflammatory phenotype, ↓ tumor growth | Orillion et al., 2018 | |

| EODF | mouse | p53-het/Sirt1-tg | ↑ survival, ↓ tumor onset | Herranz et al., 2011 | |

| EODF | mouse | p53 deficiency | ↑ survival, ↓ tumor onset | Herranz et al., 2011 | |

| short-term intermittent CR | mouse | BalB/C mice with 4T1 breast cancer cell transplantation | no effect on chemotherapy efficacy | Brandhorst et al., 2013 | |

| CR | mouse | Rb+/− | no benefit in delaying growth or progression of neuroendocrine tumors | Sharp et al., 2003 | |

| CR | mouse | Foxo3 deficiency | ↑ lifespan, ↓ tumors | Shimokawa et al., 2015 | |

| CR | mouse | high-fat-diet-induced Lewis lung carcinoma | ↓ proinflammatory cytokines, ↓ angiogenic factors, ↓ insulin, ↓ adiposity, ↓ tumor metastasis | Sundaram and Yan, 2016 | |

| CR | mouse | Balb/c with breast cancer cell transplantation | ↑ survival, ↓ metastasis, ↓ IGF-1R, ↓ inflammatory cytokines with cisplatin/doce-taxol treatment | Simone et al., 2018 |

6-OHDA, 6-hydroxydopamine; APOE, apolipoprotein E; BDNF, brain-derived neurotrophic factor; CR, caloric restriction; DSS, dextran sulfate sodium; EODF, every-other-day feeding; Hdac2, histone deacetylase 2; hsp70, heat shock protein 70; IF, intermittent fasting; IGF-1R, insulin growth factor 1 receptor; MPTP, 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine; MR, methionine restriction; NZO, New Zealand Obese; PR, protein restriction; PuR, purine restriction; Q85/Q175, poly-glutamine repeats in the huntingtin gene; Rb, retinoblastoma; RENCA, renal carcinoma; SHROB, Spontaneously Hypertensive Obese; STF, short-term fasting; TRF, time-restricted feeding.

Obesity and diabetes

Overnutrition contributes to tissue decline and accelerated disease progression, most notably with obesity (Must et al., 1999). DR increases leptin receptors, a satiety signal in the brain, which reduces free leptin in plasma (Yamada et al., 2019). However, leptin signaling has also been linked to improved fatty acid beta-oxidation and improved cardiovascular health. In diet-induced obese mice, restriction of branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs) induces rapid fat loss and improved cardiovascular health (Cummings et al., 2018). BCAA restriction is capable of improving health in nonobese animals as well as in humans (Fontana et al., 2016). However, these benefits do not always correlate with extended longevity (Nelson et al., 2016; Wilson et al., 2020), suggesting that DR can alter physiology without affecting lifespan. In flies, protein restriction increases triglyceride levels but also turnover, thus increasing triglyceride utilization (Katewa et al., 2012; Nelson et al., 2016). This suggests that metabolic shifts in DR can help allow for more effective utilization of fat storage.

Obesity can potentially give rise to a myriad of diseases, including diabetes, cardiovascular disease (CVD), and cancer (Low Wang et al., 2016; Massetti et al., 2017), though studies have investigated the incidence of “healthy obese” individuals who do not suffer from disease despite being obese (Stefan et al., 2013). Obesity’s targets are widespread and oftentimes lead to comorbidities within the same individual. Since dietary intake greatly contributes to obesity, DR is routinely prescribed to combat these disorders. Specifically, carbohydrate restriction improves metabolic syndrome in patients, as determined by a panel of fat-related readouts (Hyde et al., 2019). Extensive work in mouse models of type 2 diabetes has shown extensive benefits of DR (Table 3). Time-restricted feeding can also improve cardiometabolic disorders (Melkani and Panda, 2017). Additionally, dietary modulation is proposed to delay or treat liver diseases in patients (Romero-Gómez et al., 2017) such as nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, which is more prevalent with obesity (Hannah and Harrison, 2016). Protein malnutrition is a common symptom of liver cirrhosis, and thus protein restriction proves detrimental in cirrhosis patients (Toshikuni et al., 2014). Thus, while the link between dietary intake and induction of metabolic disorders is clear, in specific cases like liver cirrhosis, DR may be detrimental. This evidences the need for a case-by-case analysis for how diet can be utilized therapeutically for specific obesity-related disorders.

Cardiovascular aging and heart disease

Cardiovascular aging is closely linked to obesity, and CVD is the leading cause of death in the United States, particularly in individuals with type 2 diabetes (Jin, 2018). Diet also contributes to the onset of cardiovascular decline and CVD (Micha et al., 2017). Because of this link, research on cardiovascular health has often utilized dietary interventions. Obese ob/ob mice demonstrate rapid cardiovascular decline (Raju et al., 2006), and CR reduces lipid accumulation and reverses myocardial hypertrophy (Sloan et al., 2011; Verreth et al., 2004). CR also reduces oxidative stress, inflammation, and fibrosis in these mice (An et al., 2020). In wild-type mice fed a high-fat diet, risk of cardiovascular aging is elevated but is reversed through fasting (Tanner et al., 2010). CR also benefits cardiovascular health in primates (Colman et al., 2009, 2014; Mattison et al., 2012). Forms of DR are often utilized for individuals at risk for CVD (Brandhorst and Longo, 2019a; Mirzaei et al., 2016), as well as to slow age-related decline in cardiovascular health (Fontana, 2018; Wei et al., 2017). Rat strains such as the spontaneously hypertensive obese model have demonstrated how cardiovascular decline occurs (Ernsberger et al., 1999) and how CR can prevent this decline (Table 3) (Ernsberger et al., 1994). Though the genetics behind CVD are not well elucidated, studies in primates have helped identify novel loci associated with its onset in response to elevated nutrient load (Karere et al., 2013; Rainwater et al., 2003). Studies in CVD patients further demonstrate the benefits of DR, such as reduced low-density lipoprotein and triglyceride levels following carbohydrate restriction (Bhanpuri et al., 2018) or CR (García-Prieto and Fernandez-Alfonso, 2016). In all, complications relating to cardiovascular aging can largely be mediated, in part, through dietary interventions.

Digestive tissue and intestinal dysfunction

DR has profound effects on the intestinal tract. Intestinal homeostasis is regulated in response to diet through altered expression of transcription factors such as Myc (Akagi et al., 2018) and XBP1 in flies (Luis et al., 2016), upregulated autophagy in worms (Gelino et al., 2016), and prevention of inflammation due to intestinal microbiome leakage in flies, pigs, and humans (Fan et al., 2017; Rera et al., 2012; Santoro et al., 2018). This suggests that DR can be used to regulate intestinal health and aging (Keenan et al., 2015) as well as intestinal disorders (Tuck and Vanner, 2018). mTORC1 also plays an important role in regulating healthy intestinal stem cell function to preserve intestinal homeostasis, and continued overactivation of mTORC1 such as through overnutrition has been shown to induce age-related stem cell decline in flies (Haller et al., 2017). However, mTORC1 is also shown to be upregulated during CR to induce expansion of the intestinal stem cell (ISC) population, which ensures gut homeostasis (Igarashi and Guarente, 2016) and ISC self-renewal in mice (Yilmaz et al., 2012). These conflicting results provide a complicated interaction for maintaining health.

Patients with digestive disorders such as inflammatory bowel diseases, including Crohn’s disease and colitis, are regularly prescribed dietary interventions, particularly those low in fat or carbohydrates, to improve symptoms (Prince et al., 2016). In mouse models, methionine restriction (MR) (Liu et al., 2017) or CR (Shibolet et al., 2002) have been useful for combating the worsening of digestive disorders (Table 3). Overall, DR appears useful to maintain proper intestinal barrier function and metabolism (Lian et al., 2018), but the biochemical mechanisms involved must be closely regulated.

Excretory system and renal diseases

Renal system aging is also largely improved with DR, whereas its decline is exacerbated by overnutrition. Studies in murine models have demonstrated improved renal stress resistance under short-term DR, an effect that is, in part, regulated by IIS (Jongbloed et al., 2017), and other studies have shown altered ammonia metabolism following DR (Lee et al., 2015). Reduction of dietary AGEs alters gut-microbiome composition specifically in patients undergoing peritoneal dialysis, and these effects are suggested to potentially have a positive effect on the incidence of CVD (Yacoub et al., 2017). A meta-analysis of CR studies in rodents for chronic kidney disease identified robustly positive effects through measures such as blood urea nitrogen and degree of nephropathy (Xu et al., 2015a). Studies to determine how diet might influence renal ischemia reperfusion also show positive effects with DR (Table 3), suggesting that DR has therapeutic potential. Additionally, in a fly model for hyperuricemia, DR reduces the incidence of uric-acid concretions in the malpighian tubule, which is analogous to the human kidney, and this is regulated by IIS activity (Lang et al., 2019). In all, data demonstrate that renal dysfunction can largely be alleviated by DR.

Nervous system and neurodegenerative diseases