Abstract

Objective:

To evaluate the literature on different methods of scoring plaque in patients with fixed orthodontic appliances.

Materials and Methods:

A systematic electronic and hand search using MEDLINE and PubMed was conducted.

Results:

Most orthodontic trials have used the original Silness and Löe plaque index. Indices vary in several potentially important aspects. Only two papers have reported reproducibility of methods of plaque scoring in orthodontic patients.

Conclusion:

Some plaque indices are inappropriate for orthodontic patients. Newer digital planimetric methods are promising if more complex. There is a need to further assess the reproducibility and practicability of the advocated methods.

Keywords: Fixed appliance, Plaque scoring, Systematic review

INTRODUCTION

Dental plaque is a highly complex organization in a biofilm form and is considered the main causative factor in dental caries and periodontal disease. Orthodontic treatment with fixed appliances is a risk factor for plaque accumulation.1 Assessment of dental plaque is therefore essential in evaluation of the oral hygiene of individual patients undergoing fixed appliance treatment and in clinical studies measuring plaque.

One approach to scoring plaque is planimetric plaque analysis, which expresses the plaque area as a percentage of the tooth surface covered with plaque.2 However, the most common basis for plaque scoring is the use of a numeric categorical scale (ie, an index). Several such indices have been developed over the years, most notably those advocated by Silness and Löe,3 O'Leary,4 and Quigley and Hein,5 and its modification, the Turesky index.6 These subjective visual evaluations are generally based on plaque extent and thickness near the gingival margin and coronal extension of plaque. They were designed to reflect the typical pattern of progression of plaque accumulation.

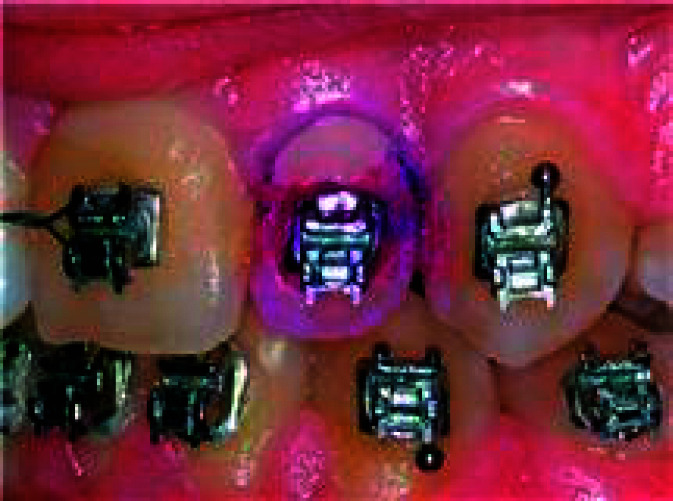

However, with fixed orthodontic appliances in place, the pattern of plaque accumulation is significantly affected by the presence of bonded attachments and archwires7; the suitability of these indices for bracketed orthodontic patients must therefore be questioned (Figure 1). In relation to the occurrence and severity of gingivitis and periodontal disease, traditional indices may still be appropriate when orthodontic appliances are in place, but with regard to enamel decalcification, these indices are unlikely to satisfactorily reflect the pattern of plaque accumulation. The aim of this paper was to review the literature on methods of quantifying plaque accumulation for patients wearing fixed appliances.

Figure 1.

Disclosed plaque on a bracketed tooth showing distribution predominantly behind the archwire.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Reporting Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses) protocol was followed to report this systematic review.8,9 The search was confined to articles in the English language. An electronic search using MEDLINE and PubMed was conducted using the following free-text terms: orthodontics, orthodontic (preventive, corrective, and interceptive), orthodontic brackets, dental plaque, and dental plaque index.

In addition, a hand search was carried out from 1980 to 2011 in American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics; The Angle Orthodontist; European Journal of Orthodontics and Journal of Orthodontics. The studies that were sought were clinical trials of patients receiving fixed orthodontic treatment wherein the plaque accumulation was quantified. Exclusion criteria included studies where other aspects of dental plaque were examined (eg, where orthodontic ligatures were examined with scanning electron microscopy) and studies in which plaque was subjected to microbial analysis. The method of plaque scoring in each study was scrutinized for evidence of its merits and deficiencies and was assessed for any data related to reproducibility of the method.

RESULTS

The electronic and hand search initially identified a total of 115 abstracts. These were screened for eligibility, and 53 were accepted as potentially meeting the inclusion criteria. Independent examination by two reviewers produced 40 articles that met the criteria.

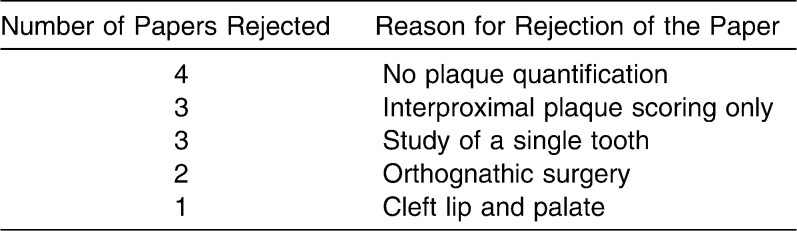

Table 1 contains the number of papers that were excluded with the reasons. Table 2 presents the method of plaque quantification used for the included papers.

Table 1.

Number of and Reasons for Rejected Papers

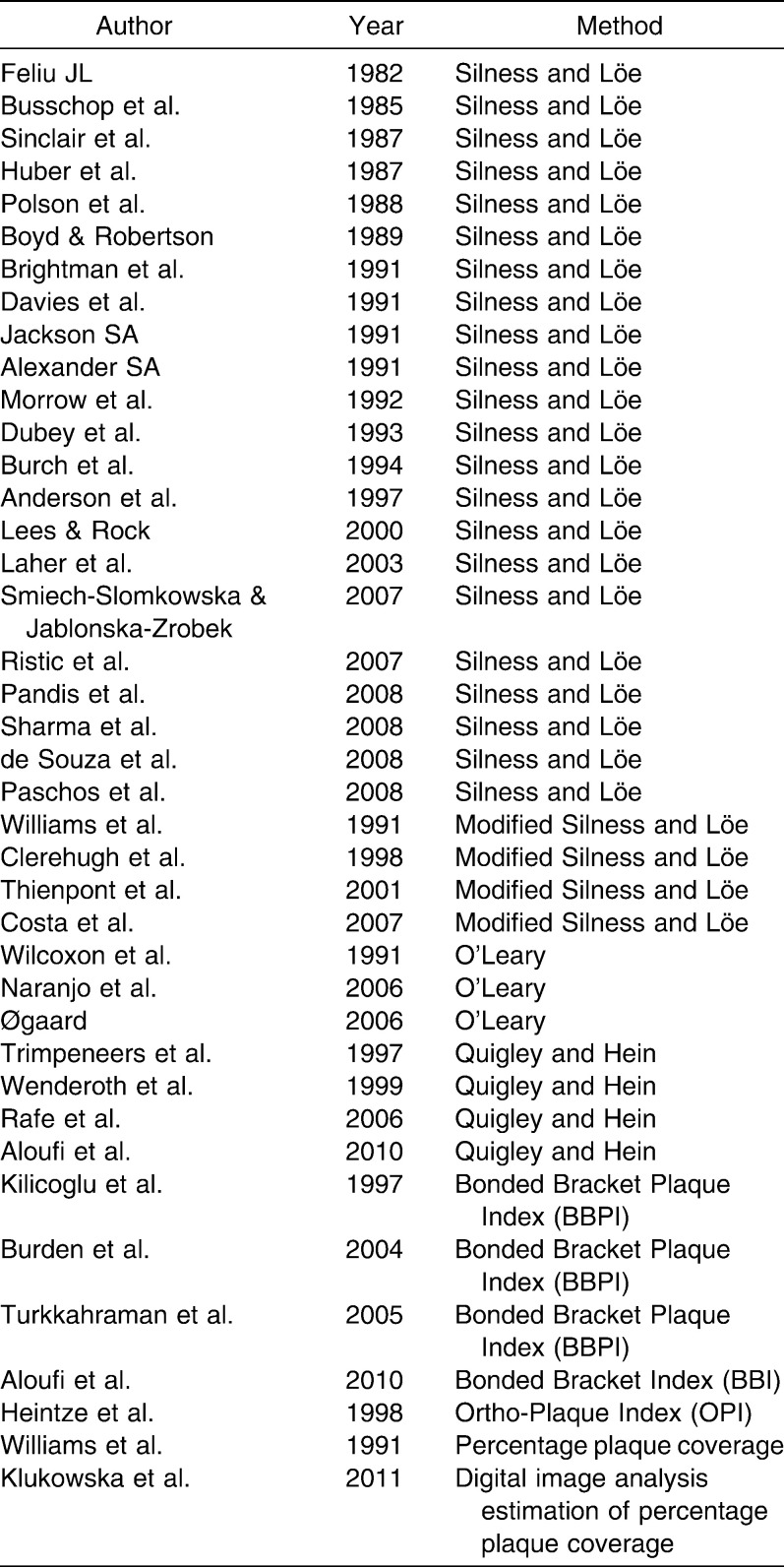

Table 2.

Studies of Plaque Accumulation in Patients Wearing Fixed Orthodontic Appliances

DISCUSSION

Table 2 shows that a significant majority of trials involving patients wearing fixed orthodontic appliances10–31 have used the plaque index originally described by Silness and Löe. This index is a categorical scale. Code 0 is given when there is no plaque accumulation, code 1 when plaque can be removed from the gingival third, code 2 when there is visible plaque, and code 3 when there is a heavy accumulation of plaque. This index has the merits of simplicity and wide usage throughout dentistry. However, with only four categories, it has relatively poor discrimination. It reflects the common pattern of progression of plaque accumulation in the absence of an orthodontic bracket, so it is inherently less appropriate for the categorization of plaque on bracketed teeth.

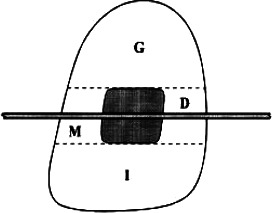

Williams et al.32 addressed the shortcomings of the Silness and Löe index for bracketed teeth by modifying it to take into account the pattern of plaque accumulation in orthodontic patients. In this index, the tooth is divided into medial, distal, gingival, and incisal regions in relation to the bracket (Figure 2). Plaque is then scored in each area based on the four codes used in the original Silness and Löe index, and values summed to obtain a total score, which can therefore range between 0 and 16 for each tooth. This index was also used by Clerehugh et al.,33 Costa et al.,34 and Thienpont et al.35 in studies of patients with fixed orthodontic appliances. This index acknowledges the usual effects of orthodontic appliances on plaque distribution and has much greater categorical discrimination than the Silness and Löe index. These advantages must be viewed as substantial and as justifying discontinuation of the unmodified Silness and Löe index in orthodontic patients.

Figure 2.

Diagram showing modification of the Silness and Löe index as described by Williams. The tooth is divided into mesial (M), distal (D), gingival (G), and incisal (I) regions for plaque measurement.

A few studies have used the O'Leary4 index in orthodontic patients. This index scores plaque separately on mesial, midpoint, and distal aspects of both facial and lingual surfaces for each tooth. All visible plaque is scored, even if slight, and plaque scores are expressed as a percentage of the total number of potential sites. Naranjo et al.,36 Wilcoxon et al.,37 and Øgaard et al.38 used this index. This index has a maximum score of 3 on a given tooth surface and therefore is less discriminatory than the Silness and Löe index or its modification already described. The appropriateness for orthodontic patients of the divisions of the tooth surface into three vertical sections may also be considered less appropriate for bracketed teeth than the modification advocated by Williams et al.32 (Figure 2).

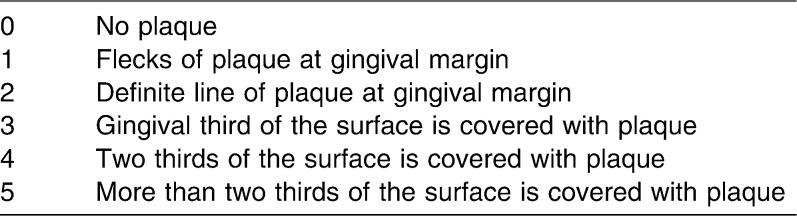

The Quigley and Hein5 plaque index and its modification as the Turesky Index6 measure the progressive coronal extension of plaque covering the tooth surface and are scored as in Table 3. These indices again fail to reflect the typical pattern of progressive plaque accumulation in the presence of an orthodontic bracket. If, for example, there is a line of plaque behind the archwire, but no other plaque on the tooth, what score should be allocated?

Table 3.

The Quigley and Hein Index

Trimpeneers et al.,39 Wenderoth et al.,40 and Rafe41 used the Quigley and Hein index in studies of orthodontic patients. Wenderoth et al. were studying the effectiveness of fluoride-releasing sealant in reducing decalcification during orthodontic treatment. The index they used clearly was not well suited to that purpose because it is based on a distribution of plaque that is more relevant to gingivitis than to decalcification when a bracket is in situ.

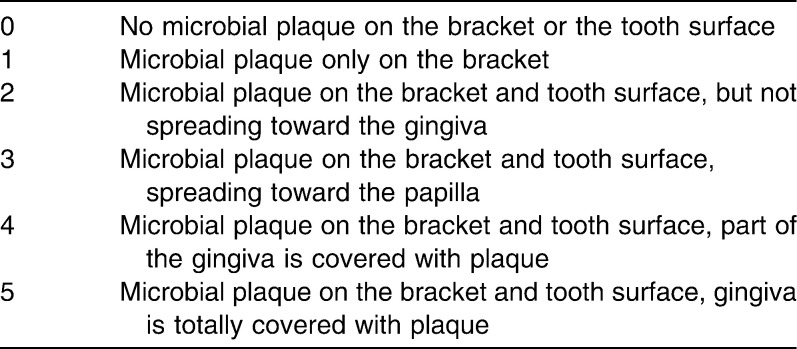

The Bonded Bracket Plaque Index (BBPI) was advocated by Kilicoglu et al.42 and has been used in three studies.42–44 Plaque is scored as in Table 4. This index aims to take account of the effect of an orthodontic bracket on plaque distribution. However, it can be seen that some codes in this index are ambiguous or perhaps illogical to apply. Although it refers to an orthodontic bracket, the categories put emphasis on spread toward and contact with the gingiva. This emphasis is perhaps appropriate in the study by Turkkahraman et al.,44 who used the index to compare the periodontal condition using two ligation methods. However, it is less suited to studies of the relationship between plaque and decalcification.

Table 4.

The Bonded Bracket Plaque Index (BBPI) (After Kilicoglu et al.

A study by Aloufi et al.45 used the Quigley-Hein index to compare groups, but an index they named the Bonded Bracket Index (BBI) was also advocated. Category definitions in the BBI are very similar to those in the BBPI, but no category can be used to describe an absence of plaque, and the highest grade of accumulation is reached at a lower area of coverage. The BBI can therefore be considered less discriminatory than the BBPI.

The Ortho-Plaque Index (OPI) was described by Heintze et al.46 Each bracketed tooth has three sites for measuring plaque: (I) cervical to the bracket toward the gingiva, (II) the region of the “shadow” of the archwire and mesial and distal to the bracket, and (III) coronal to the bracket. This zoning of the tooth is very similar to zoning for the modified Silness and Löe index and similarly has much to recommend its use in orthodontic patients, because the gingival zone is appropriate for studies of gingivitis and the middle zone reflects the tendency for plaque to accumulate behind an archwire. This index does not appear to have been used by other authors, possibly because of its relative complexity of calculation when compared, for example, with the modified Silness and Löe index.

The methods so far discussed are all categorical indices that are entirely dependent on visual estimation. The other potential approach is actual measurement of the percentage area covered by plaque using digital image analysis of photographs. Smith et al.47 were among the first of several to report such a method. The advantages of a photograph are that it can be assessed at leisure, is a permanent record, and can be viewed on multiple occasions, enabling assessment of reproducibility, which was found to be excellent in this study. However, this study was not carried out on patients with orthodontic appliances in place. Williams et al.32 had previously used standardized photographic views of disclosed teeth to measure the percentage area of plaque coverage in fixed appliance patients. They compared these results with those obtained using their modification of the Silness and Löe index and concluded that either method could be of value in studies involving fixed appliances, the choice depending on factors of convenience, methodologic considerations, and cost.

It is interesting to note that percentage area measurement of plaque has been used in only one subsequent study—that by Klukowska et al.48 The relative lack of orthodontic studies using this method is probably related to the longer time required—even though direct digital measurement and computation are now used—and the greater technical complexity of the method.

It should be noted that area measurement is not completely immune from an element of subjective judgment and other potential sources of error. These potential errors are probably small in relation to those associated with visual estimation for a categorical index, but they are nevertheless a factor. Klukowska et al.48 used an expert analyst to adapt and apply the pixel color discrimination method of Smith et al. They reported very high reproducibility of the “masking” protocol for identifying tooth boundaries. One potentially powerful refinement of area measurement is a separate analysis for different regions of the labial tooth surface, which Klukowska et al.48 reported and which confirmed the high levels of plaque accumulation behind an archwire.

CONCLUSIONS

Most orthodontic trials have used the original Silness and Löe plaque index. A few more recent studies have used indices specifically designed to score plaque in patients wearing fixed appliances; these are inherently more appropriate if a categorical index is used. The modified Silness and Löe index may be considered the most valid and discriminatory.

Only two papers have reported the reproducibility of measurements of plaque coverage in orthodontic patients. Digital photographs of disclosed teeth greatly facilitate such analysis.

Direct digital measurement of percentage plaque coverage is more complex but is likely to prove more valid and more reproducible than categorical indices.

REFERENCES

- 1.Zachrisson S, Zachrisson B. U. Gingival condition associated with orthodontic treatment. Angle Orthod. 1972;42:26–34. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(1972)042<0026:GCAWOT>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Addy M, Willis L, Sterry A. Effect of toothpaste rinses compared with chlorhexidine on plaque formation during a 4-day period. J Clin Periodontol. 1983;10:89–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1983.tb01270.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Silness J, Löe H. Periodontal disease in pregnancy: correlation between oral hygiene and periodontal condition. Acta Odontol Scand. 1964;22:121–135. doi: 10.3109/00016356408993968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O'Leary T. J, Drake R. B, Naylor J. E. The plaque control record. J Periodontol. 1972;43:38. doi: 10.1902/jop.1972.43.1.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Quigley G. A, Hein J. W. Comparative cleansing of manual and power brushing. J Am Dent Assoc. 1962;65:26–29. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1962.0184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Turesky S, Gilmore N, Glichman T. Reduced plaque formation by the chloromethyl analogue of vitamin C. J Periodontol. 1970;41:41–43. doi: 10.1902/jop.1970.41.41.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klöehn J. S, Pfeifer J. S. The effect of orthodontic treatment on the periodontium. Angle Orthod. 1974;44:127–134. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(1974)044<0127:TEOOTO>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman D. G. The PRISMA Group Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-Analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liberati A, Altman D. G, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-Analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:W1–W30. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brightman L. J, Terezhalmy G. T, Greenwell H, Jacobs M, Enlow D. H. The effects of a 0.12% chlorhexidine gluconate mouthrinse on orthodontic patients aged 11 through 17 with established gingivitis. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1991;100:324–329. doi: 10.1016/0889-5406(91)70069-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davies T. M, Shaw W. C, Worthington H. V, Addy M, Dummer P, Kingdon A. The effect of orthodontic treatment on plaque and gingivitis. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1991;99:155–162. doi: 10.1016/0889-5406(91)70118-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Busschop J. L, Van Vlierberghe M, De Boever J, Dermaut L. The width of the attached gingiva orthodontic treatment: a clinical study in human patients. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1985;87:224–229. doi: 10.1016/0002-9416(85)90043-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sinclair P. M, Berry C. W, Bennett C. L, Israelson H. Changes in gingiva and gingival flora with bonding and banding. Angle Orthod. 1987;57:271–278. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(1987)057<0271:CIGAGF>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burch J. G, Lanese R, Ngan P. A two-month study of the effects of oral irrigation and automatic toothbrush use in an adult orthodontic population with fixed appliances. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1994;106:121–126. doi: 10.1016/S0889-5406(94)70028-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smiech-Slomkowska G, Jablonska-Zrobek J. The effect of oral health education on dental plaque development and the level of caries-related Streptococcus mutans and Lactobacillus spp. Eur J Orthod. 2007;29:157–160. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cjm001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alexander S. A. Effects of orthodontic attachments on the gingival health of permanent second molars. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1991;100:337–340. doi: 10.1016/0889-5406(91)70071-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pandis N, Vlahopoulos K, Polychronopoulu A, Madiasnos P, Eliades T. Periodontal condition of the mandibular anterior dentition in patients with conventional and self-ligating brackets. Orthod Craniofac Res. 2008;11:211–215. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-6343.2008.00432.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ristic M, Vlahovic Svabic M, Sasic M, Zelic O. Clinical and microbiological effects of fixed orthodontic appliances on periodontal tissues in adolescents. Orthod Craniofac Res. 2007;10:187–195. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-6343.2007.00396.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sharma N. C, Lyle D. M, Qaqish J. G, Galustians J, Schuller R. Effect of dental water jet with orthodontic tip on plaque and bleeding in adolescent patients with fixed orthodontic appliances. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2008;133:565–571. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2007.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Souza R. A, de Araujo Magnani M. B. B, Nouer D. F, da Silva C. O, Klein M. I, Sallum E. A, Goncalves R. B. Periodontal and microbiologic evolution of 2 methods of archwire ligation: ligature wires and elastomeric rings. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2008;134:506–512. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2006.09.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jackson C. L. Comparison between electric toothbrushing and manual toothbrushing with and without oral irrigation, for oral hygiene of orthodontic patients. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1991;99:15–20. doi: 10.1016/S0889-5406(05)81675-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boyd R. L, Robertson P. B. Effect of rotary electric toothbrush versus manual toothbrush on periodontal status during orthodontic treatment. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1989;96:342–347. doi: 10.1016/0889-5406(89)90354-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morrow D, Wood D. P, Speechley M. Clinical effect of subgingival chlorhexidine irrigation on gingivitis in adolescent orthodontic patients. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1992;101:408–413. doi: 10.1016/0889-5406(92)70113-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dubey R, Jalili V. P, Garg S. Oral hygiene and gingival status in orthodontic patients. J Pierre Fauchard Acad. 1993;7:43–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lees A, Rock W. P. A comparison between written, verbal, and videotape oral hygiene instructions for patients with fixed appliances. J Orthod. 2000;27:323–328. doi: 10.1093/ortho/27.4.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Laher A, Kroon J, Booyens S. J. Effectiveness of four manual toothbrushes in a cohort of patients undergoing fixed orthodontic treatment in an academic training hospital. SADJ. 2003;58:231, 234–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paschos E, Limbach M, Teichmann M, Huth K. C, Folwaczny M, Hickel R, Rudzki-Janson I. Orthodontic attachments and chlorhexidine-containing varnish on gingival health. Angle Orthod. 2008;78:908–916. doi: 10.2319/090707-422.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Feliu J. L. Long-term benefits of orthodontic treatment on oral hygiene. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1982;82:473–477. doi: 10.1016/0002-9416(82)90315-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Anderson G. B, Bowden J, Morrison E. C, Caffesse R. G. Clinical effects of chlorhexidine mouthwashes on patients undergoing orthodontic treatment. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1997;111:606–612. doi: 10.1016/s0889-5406(97)70312-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Polson A. M, Subtelny J. D, Meitner S. W, Polson A. P, Sommers E. W, Iker H. P, Reed B. E. Long-term periodontal status after orthodontic treatment. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1988;93:51–58. doi: 10.1016/0889-5406(88)90193-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huber S. J, Vernino A. R, Nanda R. S. Professional prophylaxis and its effect on the periodontium of full banded orthodontic patients. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1987;91:321–327. doi: 10.1016/0889-5406(87)90174-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Williams P, Clerehugh V, Worthington H. V, Shaw W. C. Comparison of two plaque indices for use in fixed orthodontic appliance patients. J Dent Res. 1991;70:703. Abstract 276. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Clerehugh V, Williams P, Shaw W. C, Worthington H. V, Warren P. A practice-based randomised controlled trial of the efficacy of an electric and a manual toothbrush on gingival health in patients with fixed orthodontic appliances. J Dent. 1998;26:633–639. doi: 10.1016/s0300-5712(97)00065-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Costa M. A, Silva V. C, Miqui M. N, Sakima T, Spolidorio D. M. P, Cirelli J. A. Efficacy of ultrasonic, electric and manual toothbrushes in patients with fixed orthodontic appliances. Angle Orthod. 2007;77:361–366. doi: 10.2319/0003-3219(2007)077[0361:EOUEAM]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thienpont V, Dermaut L. R, Van Maele G. Comparative study of 2 electric and 2 manual toothbrushes in patients with fixed orthodontic appliances. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2001;120:353–360. doi: 10.1067/mod.2001.116402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Naranjo A. A, Trivino M. L, Jaramillo A, Betancourth M, Botero J. E. Changes in the subgingival microbiota and periodontal parameters before and three months after bracket placement. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2006;130:275.e17–275.e22. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2005.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wilcoxon D. B, Ackerman R. J, Killoy W. J, Love J. W, Sakumura J. S, Tira D. E. The effectiveness of a counterrotational-action power toothbrush on plaque control in orthodontic patients. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1991;99:7–14. doi: 10.1016/S0889-5406(05)81674-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Øgaard B, Afzelius Alm A, Larsson E, Adolfsson U. A prospective, randomised clinical study on the effects of an amide fluoride/stannous fluoride toothpaste/mouthrinse on plaque, gingivitis, and initial caries lesion development in orthodontic patients. Eur J Orthod. 2006;28:8–12. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cji075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Trimpeneers L. M, Wijgaerts I. A, Grognard N. A, Dermaut L. R, Adriaens P. A. Effect of electric toothbrushes versus manual toothbrushes on removal of plaque and periodontal status during orthodontic treatment. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1997;111:492–497. doi: 10.1016/s0889-5406(97)70285-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wenderoth C. J, Weinstein M, Borislow A. J. Effectiveness of a fluoride-releasing sealant in reducing decalcification during orthodontic treatment. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1999;116:629–634. doi: 10.1016/s0889-5406(99)70197-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rafe Z, Vardimon A, Ashkenazi M. Comparative study of 3 types of toothbrushes in patients with fixed orthodontic appliances. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2006;130:92–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2006.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kilicoglu H, Yildirim M, Polater H. Comparison of the effectiveness of two types of toothbrushes on oral hygiene of patients undergoing orthodontic treatment with fixed appliances. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1997;111:591–594. doi: 10.1016/s0889-5406(97)70309-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Burden D. J, Coulter W. A, Johnston C. D, Mullally B, Stevenson M. The prevalence of bacteraemia on removal of fixed orthodontic appliances. Eur J Orthod. 2004;26:443–447. doi: 10.1093/ejo/26.4.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Turkkahraman H, Sayin O, Bozkurt F. Y, Yetkin Z, Kaya S, Onal S. Archwire ligation techniques, microbial colonization and periodontal status in orthodontically treated patients. Angle Orthod. 2005;75:227–232. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(2005)075<0227:ALTMCA>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Aloufi F, Giancio S. G, Shibley O. Plaque accumulation in adolescent orthodontic patients: bonded versus banded teeth. Dental Learning. 2010;4(suppl 1) [Google Scholar]

- 46.Heintze S. D, Jost-Brinkmann P. G, Finke C, Miethke R. R. Oral Health for the Orthodontic Patient 1st ed. Hanover Park, Ill: Quintessence Publishing Co; 1998. pp. 67–70. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Smith R. N, Brook A. H, Elcock C. The quantification of dental plaque using an image analysis system: reliability and validation. J Clin Periodontol. 2001;28:1158–1162. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2001.281211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Klukowska M, Bader A, Erbe C, Bellamy P, White D. J, Anastasia M. K, Wehrbein H. Plaque levels of patients with fixed orthodontic appliances measured by digital plaque image analysis. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2011;139:e463–e470. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2010.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]