Abstract

Objectives:

To measure the cortical and cancellous bone densities of the palatal area in adolescents and adults and to compare bone quality among placement sites of temporary anchorage devices.

Materials and Methods:

One hundred twenty cone beam computerized tomography scans were obtained from 60 adolescents (mean age, 12.2 ± 1.9 years) and 60 adults (24.7 ± 4.9 years). The measurements of palatal bone density were made in Hounsfield units (HU) at 72 sites at the intersections of eight mediolateral and nine anterioposterior reference lines using InVivoDental software. Repeated-measures analysis of variance was used to analyze intragroup and intergroup differences.

Results:

The cortical and cancellous bone densities in the adults (816 and 154 HU, respectively) were significantly higher than those in the adolescents (606 and 135 HU; P < .001 and P = .032, respectively). However, the anterior portion of the cortical bone in adolescents had similar density values to the posterior portion of the cortical bone in adults. Gender comparison revealed that females had greater cortical bone densities (769 HU) than their male counterparts did (654 HU; P < .001).

Conclusions:

Palatal bone densities were significantly higher in adults than in adolescents, and the anterior palatal areas of adolescents were of similar values to those at the posterior palate of adults.

Keywords: Bone density; Palate, CBCT; Adolescents

INTRODUCTION

The recent advent of temporary anchorage devices (TADs) has allowed increased efficacy in molar distalization mechanics with minimum untoward effects in correction of noncompliant Class II malocclusion.1–4 However, TADs are also known to be frequently associated with higher failure rates among adolescents when compared with adults, which suggests that age may be a contributing factor. It has been speculated that it may be due to thinner cortical layers coupled with immature bone qualities in adolescents.5 The challenges of placing TADs in younger patients may involve incomplete obliteration of the midpalatal suture as well as reduced target areas with smaller interradicular spaces, which are most pronounced during the mixed-dentition stage.6–11

The palate has become a popular site for placement of TADs because of its easy access, presence of rich keratinized tissue, and low risk potential for root injury among adolescents.12–16 Recently, several investigators have evaluated the use of palatal mini-implants, which served as anchors for maxillary molar distalization. Both Benson et al.17 and Sandler et al.18 have conducted randomized clinical trials and concluded that anchorage reinforcement by palatal mini-implants is as effective as a headgear. More recently, Kook et al.19 reported that the palatal plate appliance could be used as an anchorage for full-arch distalization among adolescent patients in a mixed-dentition stage.

The palate was reported to be a reliable and stable placement site for TADs because it offers both a sufficient quality and quantity of bone.20–23 Previous investigations have mainly focused on the quantity of palatal cortical bone. Gracco et al.24 found no significant differences in palatal bone thickness between adults and adolescents. However, studies on palatal bone density, one of defining elements of bone quality, have been limited to adults only.25–28

Therefore, the purpose of this study was to measure the cortical and cancellous bone densities of the palatal area in adolescents and adults and to compare bone quality among potential placement sites for TADs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The sample consisted of cone beam computerized tomography (CBCT) scans (i-CAT, Hatfield, Penn) from 60 adolescent and 60 adult randomly selected patients who had visited the dental department of Seoul St. Mary's Hospital, The Catholic University of Korea. The adolescent group included 32 boys and 28 girls (mean age, 12.2 ± 1.9 years; range, 9–15 years), while the adult group consisted of 20 men and 40 women (mean age, 24.7 ± 4.9 years; range, 18–36 years). Exclusion criteria included any patients with general diseases, pathologic lesions in the palate, or previous use of any medication that could affect bone density. The Institutional Review Board of the Catholic University of Korea reviewed and approved the study.

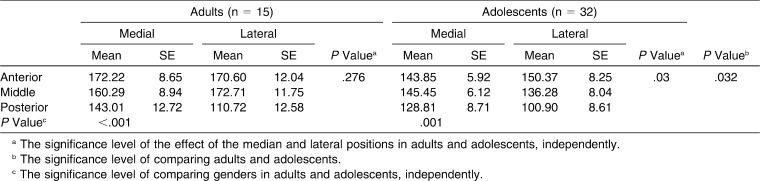

InVivoDental (Anatomage Inc, San Jose, Calif.), a volumetric imaging software, was used to measure bone density in Hounsfield units (HU), which are directly associated with tissue attenuation coefficients.29,30 The cortical and cancellous bone densities of the palate were measured at 2, 4, 6, and 8 mm proximal to the midpalatal suture on the coronal plane and at 3-mm intervals from 0 to 24 mm moving posteriorly from the most posterior margin of the incisive foramen on the sagittal plane (Figure 1). The measurements were made over a set of equally sized grids formed by 72 sites covering 384 mm2 of the palate, which is the area of interest. To measure the cortical bone density, the midpoint of the cortical bone thickness was selected to represent its density at each point. Also, the density of the cancellous bone was measured at the trabeculae, located halfway inciso-apically between the two cortical plates. To test the intraexaminer reliability, 10 randomly selected scans were measured 2 weeks later by the same person.

Figure 1.

Reference lines for measuring the palatal bone density. (A) Occlusal view. (B) Sagittal view.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS 16.0.2.1 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Ill). The measured bone density values were averaged for the subjects, keeping specific to the designated area divided by anterior (0–6 mm), middle (9–15 mm), and posterior (18–24 mm) as well as medial (2 and 4 mm) and lateral (6 and 8 mm) segments. Repeated-measures analysis of variance (RM ANOVA) was used to test the intragroup and intergroup differences of the bone density. Intergroups are two groups of adolescents and adults, and females and males. Intragroups are two positions of medial and lateral and three areas of anterior, middle, and posterior. Statistical significance was determined at P < .05.

RESULTS

The results of the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) test revealed high reliability between the two assessments (ICC > .8). Since there were no significant statistical differences between the left- and the right-side measurements, the measured data from the two halves were combined (P = .088).

Evaluation of the cortical bone density showed that the adults displayed significantly higher density (816 ± 15 HU) than did adolescents (606 ± 14 HU; P < .001). Also, the females demonstrated a higher bone density (769 ± 14 HU) than their male counterparts did (654 ± 16 HU; P < .001). However, no significant interaction between age and gender was found (P = .063).

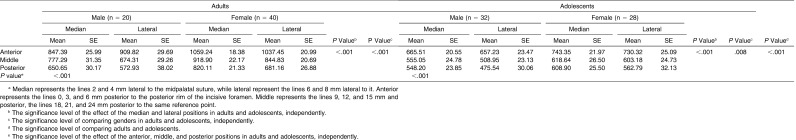

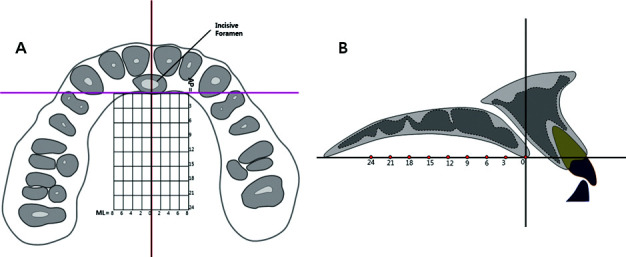

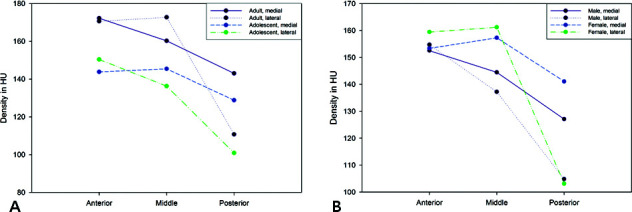

With no significant interaction between mediolateral positional changes and gender, the overall bone density difference of the lateral position was significantly greater than that of the medial position (P < .001). In both adult and adolescent groups, the cortical bone showed significant gradient changes moving in the anteroposterior and mediolateral directions (P < .001). At the same time, the cortical bone revealed a significant interaction between the two directional factors (P < .01). In the adolescent group, however, the cortical bone density differences between the middle and posterior of the three areas disappeared throughout medial as well as lateral positions in both males and females (P = .207). In addition, females displayed higher bone densities than males did in the adult and adolescent groups (P = .008 and <.001, respectively; Table 1; Figure 2).

Table 1.

Comparison of Cortical Bone Density Between Adults and Adolescents (Unit: Hounsfield)a

Figure 2.

Comparison of cortical bone density according to palatal area. (A) Adult vs adolescent. (B) Male vs female.

Similar to cortical bone, cancellous bone in adults displayed a significantly higher bone density (154 ± 7 HU) than in adolescents (135 ± 5 HU; P = .032). However, unlike cortical bone, cancellous bone in adolescents revealed no significant difference in bone density with regard to gender (P = .546).

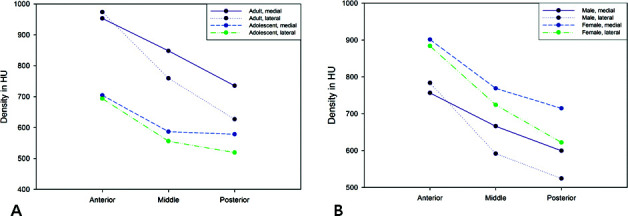

In the adult group, the anterior and middle areas had significantly higher cancellous bone densities than the posterior area did (P = .002 and .009, respectively). However, the effect of mediolateral positional changes and the interaction between the anteroposterior and mediolateral positions were not significant (P = .276 and .059, respectively; Table 2; Figure 3).

Table 2.

Comparison of Cancellous Bone Density Between Adults and Adolescents (Unit: Hounsfield)

Figure 3.

Comparison of cancellous bone density according to palatal area. (A) Adult vs adolescent. (B) Male vs female.

In the adolescent group, the cancellous bone density showed a significant effect of the anteroposterior and mediolateral positions (P = .001 and .03, respectively) and a significant interaction between both factors (P = .004) due to low densities in the lateral posterior position. Also, significantly higher cancellous bone densities were found in the anterior and middle areas than in the posterior area (P = .005 and .029, respectively; Table 2).

DISCUSSION

In adolescent patients with Class II malocclusion, application of TADs for molar distalization prevents the undesirable reciprocal effects and eliminates the dependence on the patient's cooperation.19 The aim of our study was to assess bone quality at the potential placement sites in adolescents. The cortical and cancellous bone densities in adults were higher than those in adolescents. The means of the cortical bone density in the adult group of our study ranged between 1059 and 573 HU, approximately corresponding to the D2 (850–1250 HU) and the upper range of the D3 (350–850 HU) categories in classification of bone tissue by Misch.31 Likewise, the cortical bone density in the adolescent group fell into the D3 category, ranging between 743 and 476 HU.

The paramedian palatal area has been recommended for placement of TADs due to sufficient cortical bone amount and adequate thickness of keratinized soft tissue.9,32 Placement of TADs in this area also tends to minimize the potential interaction with the growth of the midpalatal suture in adolescents.7,9,32,33 In our study, the palatal cortical bone density of the adult group was similar to that of Moon et al.,28 showing a tendency to decrease laterally and posteriorly. On the other hand, our results differed from those of Lai et al.,34 who reported that density tends to decrease laterally and anteriorly. However, they limited their measurements to only 12 mm anteroposteriorly. Also, they applied K-mean cluster analysis, which arranges the data in a way to maximize the difference but was limited by absence of a validation set of data for classification groups.

In addition, Bernhart et al.35 reported that the most suitable area in adults for implant placement in the palate was located 6 to 9 mm posterior to the incisive foramen and 3 to 6 mm para-median to the suture. However, our results indicated that the area of high density in cortical bone extended 15 mm posterior to the incisive foramen in the medial half of the measured area and 6 mm in the lateral half. In clinical practice, it may be helpful to recognize that this area closely approximated the second premolar region in most of the cases.

The bone density of our adult group was consistent with the report by Wehrbein,36 who concluded that the density of the median palate was high enough to support mini-implants. He also suggested that the reported 10% failure rate of micro-implants inserted in the palatal area37,38 may be attributed to factors other than bone density.

Since the number of TADs currently being used in adolescents is increasing, identification and selection of the higher bone density areas in this younger age group should be worthwhile. According to Table 1, the anterior cortical bone density in adolescents ranged from 657.23 HU to 743.35 HU, which was comparable to those of the posterior area of the adults. Therefore, it could be recommended to focus placement of TADs in the anterior region if they are considered for adolescent patients.

This investigation found significant gender differences only in the cortical bone density. In accordance with Moon et al.,28 our results showed that adult females had significantly greater palatal cortical bone density than adult males did. However, Chun and Lim26 did not find any significant difference, suggesting that the presence of gender difference may be dependent on the specific sites being examined in the palate.

Figure 2 shows that the cortical bone density decreases in the lateral and posterior directions. Also, a quantitative interaction was reported, which indicated unequal magnitude of differences in bone density between the medial and lateral positions in the anterior area. However, the pattern of higher density in the medial area is in general consistent, except for the anterior area, where values are closer to each other. This pattern also shows that the densities in the middle lateral and the posterior medial areas are similar. Clinically, if TADs-assisted molar distalization for Class II correction is planned in adolescents, the palatal area near the second premolar may be considered as the placement site of choice. Accordingly, the force delivery system could be modified for efficient treatment results by changing appliance design or modifying extension arms.

In both adult and adolescent groups, Figure 3 shows that there were little changes from the anterior and middle in the cancellous bone densities. However, the difference became more noticeable in the posterior area.

In our study, cancellous bone density could not be measured in all of the 72 sites of the palate, especially in the posterior and lateral areas due to sinus pneumatization and the presence of unerupted premolars. However, the application of RM ANOVAs that use intersubject variation in statistical testing resulted in sufficient power to obtain meaningful results.

Interestingly, Gracco et al.24 reported that they found no significant differences in the thickness of the palatal bone between adults and adolescents and recommended the palate as the site of choice for the placement of miniscrews. On the contrary, our study found that adolescents were presented with significantly lower cortical and cancellous bone density, mainly in the posterior area. Therefore, if TADs are indicated in adolescent patients and the palatal regions are identified as potential recipient sites, it may be important to evaluate the different areas of the palate as these results may provide useful information about bone density of the region. These findings may be helpful for the clinicians to apply TADs to the palate.

CONCLUSIONS

Palatal bone densities were significantly higher in adults than in adolescents, and the densities of the anterior palate in adolescents were of similar value to those of the posterior palate in adults.

In both adults and adolescents, females had greater cortical bone densities than their male counterparts.

Acknowledgments

This study was partly supported by the alumni fund of the Department of Dentistry and Graduate School of Clinical Dental Science, Catholic University of Korea, and Mr Kim Kee-Hyeon of InVivoDental (Anatomage Inc).

REFERENCES

- 1.Bos A, Kleverlaan C. J, Hoogstraten J, Prahl-Andersen B, Kuitert R. Comparing subjective and objective measures of headgear compliance. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2007;132:801–805. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2006.01.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kinzinger G. S, Eren M, Diedrich P. R. Treatment effects of intraoral appliances with conventional anchorage designs for non-compliance maxillary molar distalization: a literature review. Eur J Orthod. 2008;30:558–571. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cjn047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McSherry P. F, Bradley H. Class II correction-reducing patient compliance: a review of the available techniques. J Orthod. 2000;27:219–225. doi: 10.1179/ortho.27.3.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoste S, Vercruyssen M, Quirynen M, Willems G. Risk factors and indications of orthodontic temporary anchorage devices: a literature review. Aust Orthod J. 2008;24:140–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen Y. J, Chang H. H, Huang C. Y, Hung H. C, Lai E. H, Yao C. C. A retrospective analysis of the failure rate of three different orthodontic skeletal anchorage systems. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2007;18:768–775. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2007.01405.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Revelo B, Fishman L. S. Maturational evaluation of ossification of the midpalatal suture. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1994;105:288–292. doi: 10.1016/S0889-5406(94)70123-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schlegel K. A, Kinner F, Schlegel K. D. The anatomic basis for palatal implants in orthodontics. Int J Adult Orthodon Orthognath Surg. 2002;17:133–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wehrbein H, Merz B. R, Diedrich P, Glatzmaier J. The use of palatal implants for orthodontic anchorage: design and clinical application of the orthosystem. Clin Oral Implants Res. 1996;7:410–416. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0501.1996.070416.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bernhart T, Freudenthaler J, Dortbudak O, Bantleon H. P, Watzek G. Short epithetic implants for orthodontic anchorage in the paramedian region of the palate: a clinical study. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2001;12:624–631. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0501.2001.120611.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Melsen B. Palatal growth studied on human autopsy material: a histologic microradiographic study. Am J Orthod. 1975;68:42–54. doi: 10.1016/0002-9416(75)90158-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Knaup B, Yildizhan F, Wehrbein H. Age-related changes in the midpalatal suture: a histomorphometric study. J Orofac Orthop. 2004;65:467–474. doi: 10.1007/s00056-004-0415-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kyung S. H, Lee J. Y, Shin J. W, Hong C, Dietz V, Gianelly A. A. Distalization of the entire maxillary arch in an adult. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2009;135(4 suppl):S123–S132. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2008.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tamamura N, Kuroda S, Sugawara Y, Takano-Yamamoto T, Yamashiro T. Use of palatal miniscrew anchorage and lingual multi-bracket appliances to enhance efficiency of molar scissors-bite correction. Angle Orthod. 2009;79:577–584. doi: 10.2319/031708-152.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kook Y. A, Kim S. H. Treatment of Class III relapse due to late mandibular growth using miniscrew anchorage. J Clin Orthod. 2008;42:400–411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ludwig B, Glasl B, Kinzinger G, Walde K, Lisson J. The skeletal frog appliance for maxillary molar distalization. J Clin Orthod. 2011;45:77–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Watanabe Y, Miyamoto K. A palatal locking plate anchor for orthodontic tooth movement. J Clin Orthod. 2009;43:430–437. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Benson P. E, Tinsley D, O'Dwyer J. J, Majumdar A, Doyle P, Sandler P. J. Midpalatal implants vs headgear for orthodontic anchorage—a randomized clinical trial: cephalometric results. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2007;132:606–615. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2006.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sandler J, Benson P. E, Doyle P, et al. Palatal implants are a good alternative to headgear: a randomized trial. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2008;133:51–57. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2007.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kook Y. A, Kim S. H, Chung K. R. A modified palatal anchorage plate for simple and efficient distalization. J Clin Orthod. 2010;44:719–730. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Deguchi T, Nasu M, Murakami K, Yabuuchi T, Kamioka H, Takano-Yamamoto T. Quantitative evaluation of cortical bone thickness with computed tomographic scanning for orthodontic implants. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2006;129:721e7–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2006.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kang S, Lee S. J, Ahn S. J, Heo M. S, Kim T. W. Bone thickness of the palate for orthodontic mini-implant anchorage in adults. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2007;131(4 suppl):S74–S81. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2005.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.King K. S, Lam E. W, Faulkner M. G, Heo G, Major P. W. Vertical bone volume in the paramedian palate of adolescents: a computed tomography study. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2007;132:783–788. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2005.11.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stockmann P, Schlegel K. A, Srour S, Neukam F. W, Fenner M, Felszeghy E. Which region of the median palate is a suitable location of temporary orthodontic anchorage devices? A histomorphometric study on human cadavers aged 15–20 years. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2009;20:306–312. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2008.01647.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gracco A, Lombardo L, Cozzani M, Siciliani G. Quantitative cone-beam computed tomography evaluation of palatal bone thickness for orthodontic miniscrew placement. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2008;134:361–369. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2007.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Park H. S, Lee Y. J, Jeong S. H, Kwon T. G. Density of the alveolar and basal bones of the maxilla and the mandible. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2008;133:30–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2006.01.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chun Y. S, Lim W. H. Bone density at interradicular sites: implications for orthodontic mini-implant placement. Orthod Craniofac Res. 2009;12:25–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-6343.2008.01434.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shahlaie M, Gantes B, Schulz E, Riggs M, Crigger M. Bone density assessments of dental implant sites: 1. Quantitative computed tomography. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2003;18:224–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moon S. H, Park S. H, Lim W. H, Chun Y. S. Palatal bone density in adult subjects: implications for mini-implant placement. Angle Orthod. 2010;80:137–144. doi: 10.2319/011909-40.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aranyarachkul P, Caruso J, Gantes B, et al. Bone density assessments of dental implant sites: 2. Quantitative cone-beam computerized tomography. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2005;20:416–424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shapurian T, Damoulis P. D, Reiser G. M, Griffin T. J, Rand W. M. Quantitative evaluation of bone density using the Hounsfield index. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2006;21:290–297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Misch C. E. Density of bone: effect on treatment plans, surgical approach, healing, and progressive boen loading. Int J Oral Implantol. 1990;6:23–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gracco A, Lombardo L, Cozzani M, Siciliani G. Quantitative evaluation with CBCT of palatal bone thickness in growing patients. Prog Orthod. 2006;7:164–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tosun T, Keles A, Erverdi N. Method for the placement of palatal implants. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2002;17:95–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lai R. F, Zou H, Kong W. D, Lin W. Applied anatomic site study of palatal anchorage implants using cone beam computed tomography. Int J Oral Sci. 2010;2:98–104. doi: 10.4248/IJOS10036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bernhart T, Vollgruber A, Gahleitner A, Dortbudak O, Haas R. Alternative to the median region of the palate for placement of an orthodontic implant. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2000;11:595–601. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0501.2000.011006595.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wehrbein H. Bone quality in the midpalate for temporary anchorage devices. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2009;20:45–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2008.01600.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Crismani A. G, Bernhart T, Schwarz K, Celar A. G, Bantleon H. P, Watzek G. Ninety percent success in palatal implants loaded 1 week after placement: a clinical evaluation by resonance frequency analysis. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2006;17:445–450. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2005.01223.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wehrbein H, Feifel H, Diedrich P. Palatal implant anchorage reinforcement of posterior teeth: a prospective study. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1999;116:678–686. doi: 10.1016/s0889-5406(99)70204-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]