Abstract

Objective:

To experimentally study the effects of altering implant length, outer diameter, cortical bone thickness, and cortical bone density on the primary stability of orthodontic miniscrew implants (MSIs).

Materials and Methods:

Maximum insertion torque (IT) and pullout strength (POS) of 216 MSIs were measured in synthetic bone with different cortical densities (0.64 g/cc or 0.55 g/cc) and cortical thicknesses (1 mm or 2 mm). Three MSIs were evaluated: 6-mm long/1.75-mm outer diameter, 3-mm long/1.75-mm outer diameter, and 3-mm long/2.0-mm outer diameter. To test POS, a vertical force was applied at the rate of 5 mm/min until failure occurred.

Results:

The 6-mm MSIs displayed significantly (P < .001) higher IT and POS than the 3-mm MSIs did. The 3-mm MSIs with 2.0-mm outer diameters showed significantly higher (P < .001) IT and POS than the 3-mm MSIs with 1.75-mm outer diameters. The IT and POS were significantly (P < .001) greater for the MSIs placed in thicker and denser cortical bone.

Conclusion:

Both outer diameter and length affect the stability of MSIs. Increases in cortical bone thickness and cortical bone density increase the primary stability of the MSIs.

Keywords: Miniscrew implants, Insertion torque, Pullout strength, Cortex, Density

INTRODUCTION

Orthodontic miniscrew implants (MSIs) have become an important tool in the orthodontists' armamentarium; MSIs provide absolute anchorage, are affordable, can be quickly placed at various sites, and are easily removed.1–3 However, MSIs have proven to be less stable than other endosseous implants that osseointegrate. Both screw and the host factors affect the stability of MSIs.

The screw factors are related to the screws' design. Implant diameter has been shown to be one of the most important factors for maximizing pullout strength (POS) of orthopedic screws.4,5 Longer orthopedic screws demonstrate greater POS than shorter screws do.6 The MSI literature pertaining to the effects of MSI length remains controversial.7–9 Previous studies often compare MSIs that differ in more than one characteristic, which limits their ability to evaluate the effects of diameter and length.

The host factors are related to the quantity (cortical thickness) and quality (cortical density) of the bone.3,10 Because maximum stress occurs at the cortical level,11 it has been recommended that cortical bone at MSI insertion sites should be at least 1.0-mm thick.12 Increased cortical thickness has been associated with significantly greater MSI success.13 Bone mineral density is also important for ensuring the stability of endosseous implants.14 Bone density has been positively correlated with both insertion torque (IT) and POS.15,16

Few studies have simultaneously evaluated the IT and POS of MSIs. Both must be quantified because they provide different information about primary, mechanical stability. IT and POS do not respond in the same way to experimental effects.15 The ideal MSI should minimize IT (less potential bone damage) and maximize POS (greater holding power).

The primary aim of this study is to evaluate the effects of altering implant length, outer diameter, cortical bone thickness, and cortical bone density on the primary stability of orthodontic MSIs. Given the potential root damage that can be caused by MSIs,17,18 it is especially important to determine the stability of the shorter 3-mm MSIs that have been recently introduced.19–22 The secondary aim was to determine if cortical thickness and density interact with MSI length and diameter.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

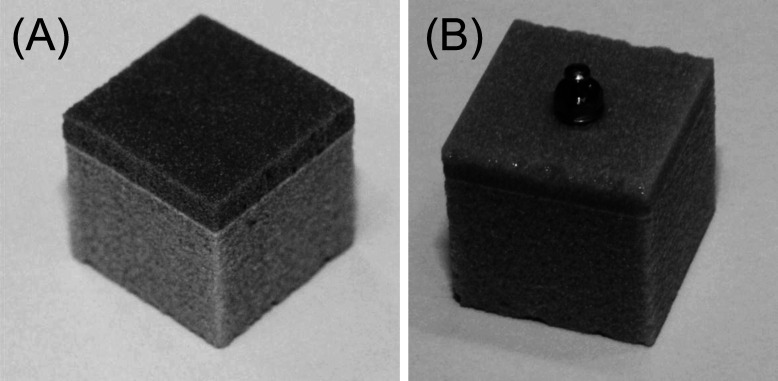

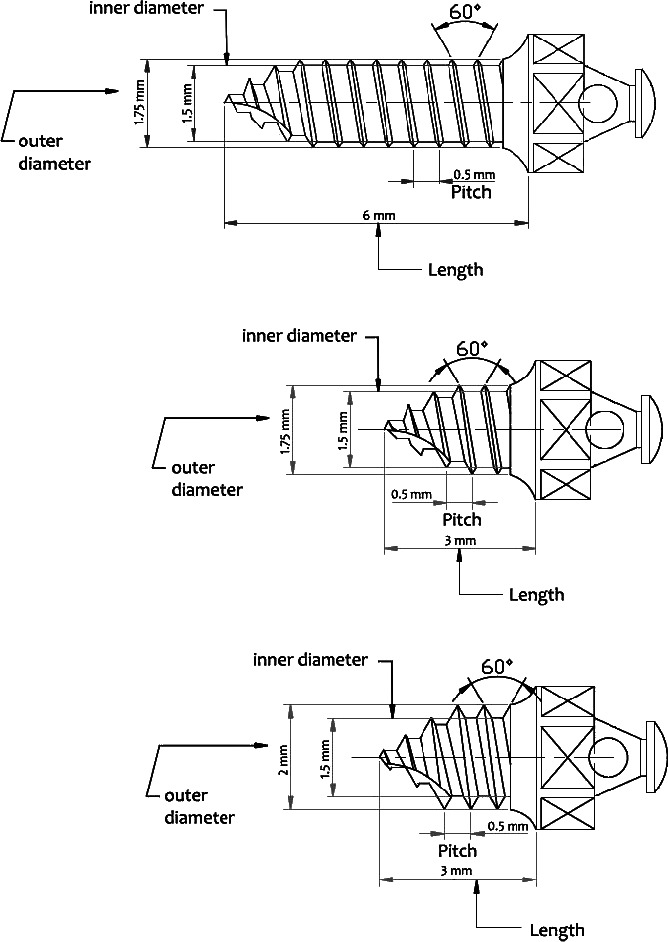

Three different MSIs were specifically fabricated by Dentos (Daegu, Korea). They were either 3-mm or 6-mm long; the 6-mm MSIs had an outer diameter of 1.75 mm; the 3-mm MSIs had outer diameters of either 1.75 mm or 2 mm. Other than length and outer diameter, the MSIs were identical in terms of all other design features (Figure 1); all inner diameters were 1.5 mm, all had 0.5-mm pitch, the apical 1.5 mm of all MSIs was tapered, all MSIs were self-drilling, and all were self-tapping. The threaded portions of the 6-mm and the 3-mm MSIs were 5.5 mm and 2.5 mm, respectively.

Figure 1.

(A) Six-millimeter-long miniscrew implant (MSI) with an outer diameter of 1.75 mm. (B) Three-millimeter-long MSI with an outer diameter of 1.75 mm. (C) Three-millimeter-long MSI with an outer diameter of 2 mm.

Synthetic Bone

Because of the variability of cadaver and animal bone,23 synthetic bone has become the standard for evaluating the primary stability of endosseous implants and MSIs because of its uniform material properties.5,24

Blocks of synthetic polyurethane bone (Sawbones, Vashon, WA) were used to test the IT and POS of the MSIs. The density of the cortical layer was 0.64 g/cc or 0.55 g/cc; the cortical density of the human mandible has been reported to be 0.64 g/cc.25 Density of the cancellous layer was 0.48 g/cc for all of the specimens. The cortical layers were either 1-mm or 2-mm thick.

Testing Groups

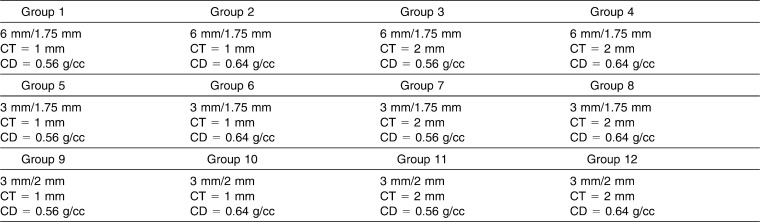

The larger bone blocks were cut into 11-mm cubes for testing purposes (Figure 2). The three MSIs were inserted into four different types of bone (two densities and two cortical thicknesses), resulting in 12 test groups. There were a total of 216 MSIs, with 18 MSIs randomly allocated to each group (Table 1).

Figure 2.

Synthetic bone cubes used showing (A) cortical and cancellous layers and (B) miniscrew implant.

Table 1.

Groupings of the Three Miniscrew Implants According to Cortical Bone Thickness (CT) and Cortical Bone Density (CD)

Insertion Torque

Each synthetic bone cube was placed in a base that secured five of its sides. The sixth side was secured with a jig attached to the base, which also served as a guide for inserting the MSIs into the center of the bone cube. The jig was attached to a motor, which rotated the bone cube and automatically inserted the MSIs at a constant speed of nine revolutions per minute.

A drill press was modified to secure a Mecmesin Advanced Force and Torque Indicator (Mecmesin Ltd, West Sussex, UK), which measured IT. The Torque Indicator and the MSI were lowered onto the rotating bone cube with a 3-lb weight attached to the arm of the drill press. A video camera recorded IT; the video was used to determine IT at the point of initial engagement and when 25%, 50%, 75%, and 100% of the MSIs' threaded portions had been inserted.

Pullout Strength

To evaluate POS, each bone block, along with an embedded MSI, was placed in a custom metal base of approximately the same dimensions as the bone blocks and secured with a lid. Pullout was performed by attaching an adapter to the miniscrew head; the adapter was secured to an Instron machine model 1011 (Instron Corp, Canton, MA), which exerted a vertical force (5 mm/min) parallel to the long axis of the MSI until failure occurred. Peak load at failure of the MSI was recorded in kilograms.

Statistical Analysis

MSIs were randomly sorted to test IT and POS. Skewness and kurtosis statistics showed that the variables were normally distributed. Because of significant interactions, separate analyses of variance of each bone type were performed to compare the three MSIs, followed by Bonferroni post hoc tests. Separate analyses of each MSI were also performed for evaluate the effects of cortical thickness and density.

RESULTS

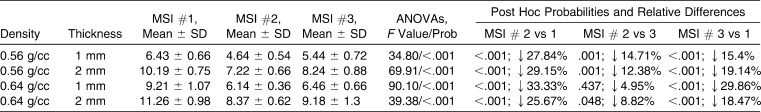

The IT of the MSIs ranged from 4.6 Ncm to 11.3 Ncm (Table 2). The 3-mm MSIs had significantly (P < .001) lower ITs than the 6-mm MSIs; the 3 mm MSIs with outer diameters of 1.75 mm and 2 mm had ITs that were 26%–33% and 15%–30% less than the 6-mm MSIs. Except for the cortical bone that was 1-mm thick and had a density of 0.64 g/cc, the wider (2 mm) 3-mm MSIs showed significantly higher IT than the narrower (1.75 mm) 3-mm MSIs.

Table 2.

Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) of Differences in Insertion Torque (Ncm), Measured at 100% of Insertion, of Miniscrew Implant (MSI) #1 (6-mm Length, 1.75-mm Outer Diameter), MSI #2 (3-mm Length, 1.75-mm Outer Diameter), and MSI #3 (3-mm Length, 2-mm Outer Diameter), With Post Hoc Pairwise Comparisons

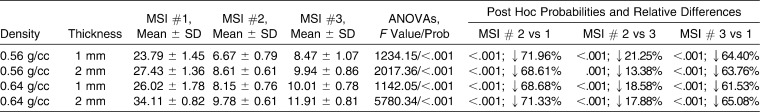

Depending on the MSI and material properties of the bone, POS at failure ranged from 6.7–34.1 kg (Table 3). POS was significantly (P < .001) lower for the 3-mm than for the 6-mm MSIs. The POSs of 3-mm MSIs with an outer diameter of 1.75 mm and 2.0 mm were 69%–72% and 62%–65% lower, respectively, than the POS of the 6-mm MSIs. POS was also significantly lower (13%–21%) for the narrower (1.75 mm) than wider (2 mm) 3-mm MSIs.

Table 3.

Analyses of Variance (ANOVAs) Evaluating Differences in Pullout Strength (kg) of Miniscrew Implant (MSI) #1 (6-mm Length, 1.75-mm Outer Diameter), MSI #2 (3-mm Length, 1.75-mm Outer Diameter), and MSI #3 (3-mm Length, 2-mm Outer Diameter) With Post Hoc Pairwise Comparisons

Bone Characteristics

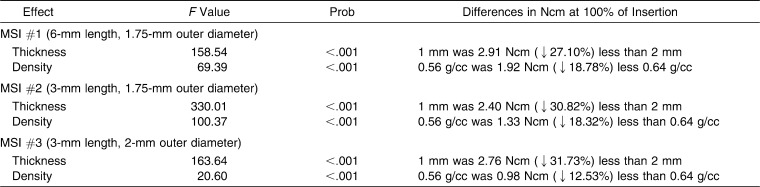

IT and POS were significantly (P < .001) greater for MSIs placed in 2-mm- than in 1-mm-thick cortical bone (Table 4). Reducing cortical thickness by 50% (from 2 mm to 1 mm) decreased IT by 27.1%–31.7%. Reducing density by 14% (from 0.64 g/cc to 0.56 g/cc) decreased IT by 12.5%–18.8%.

Table 4.

Analyses of Variance Evaluating the Effects of Cortical Bone Thickness (1 vs 2 mm) and Density (0.56 vs 0.64 g/cc) on Insertion Torque for Each Miniscrew Implant (MSI)

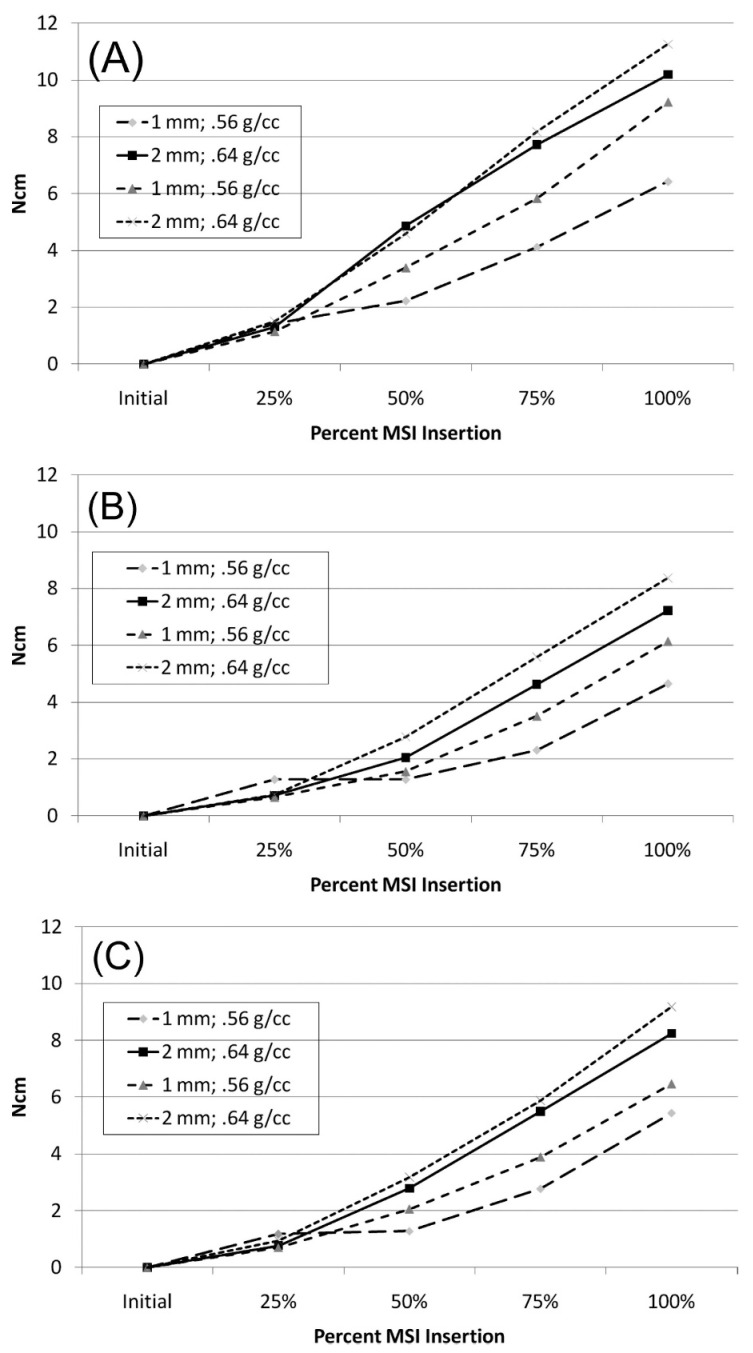

IT increased in a curvilinear fashion as the MSIs were inserted, with the greatest increases generally occurring during the last 25% of MSI insertion (Figure 2). The effects of cortical thickness and density (↑ IT with ↑ thickness and ↑ density) were well established after the MSI had been inserted 50% of its length and increased thereafter.

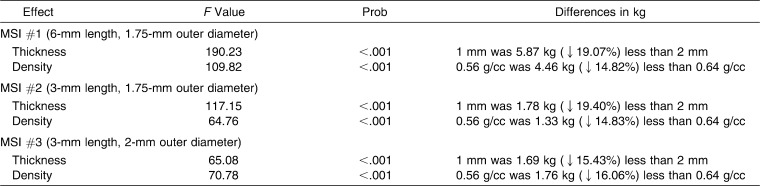

POS was also significantly (P < .001) greater when MSIs were placed in thicker, more dense, cortical bone (Table 5). The POS of MSIs placed into the 1-mm-thick cortex were 1.7–5.9 kg or 15.4%–19.1% less than when placed into 2-mm-thick cortical bone. Compared with more dense cortical bone, the POS was reduced 1.8–4.5 kg or 14.8%–16.1% when placed in less dense bone.

Table 5.

Analyses of Variance Evaluating the Effects of Cortical Bone Thickness (1 vs 2 mm) and Density (0.56 vs 0.64 g/cc) on Pullout Strength for Each Miniscrew Implant (MSI)

Intercorrelations

IT and POS were significantly and positively correlated for the 6-mm MSIs (r = .73; P < .001), the 3-mm long 1.75-mm wide MSIs (r = .81; P < .001), and the 3-mm long 2.0-mm wide MSIs (r = .65; P < .001). After controlling for cortical thickness and density, none of the MSIs showed statistically significant correlations between IT and POS.

DISCUSSION

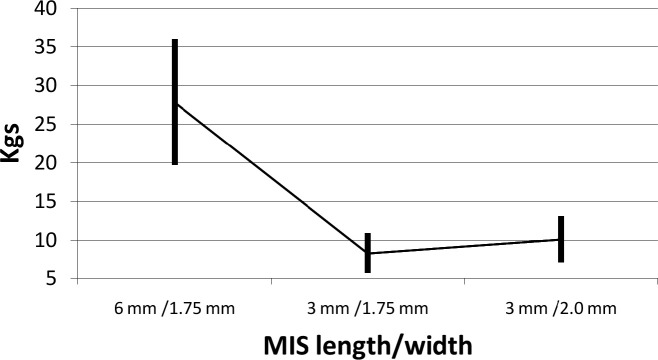

While the 3-mm MSIs showed less IT and POS than the 6-mm MSIs did, the values were consistently above limits previously recommended for stability. IT in the present study was consistently greater than the 4 Ncm needed to provide sufficient anchorage for MSIs.26 More importantly, the pullout forces of the 3-mm MSIs, especially those 2-mm wide, were also all substantially above the ranges of orthodontic forces typically applied for tooth movements (0.03–0.40 kg) and skeletal changes (0.5–1 kg).27,28 Importantly, MSIs are not typically subjected to axial loads such as those used in the present experiment to standardize testing techniques; MSIs might be expected to fail at even lower loads when forces are delivered from other directions. Even after reducing POS by 34%, as suggested to more closely approximate the POSs of the same screws tested in the tangential (cantilever) mode,29 the stability of the 3-mm MSIs is still more than sufficient to withstand orthodontic loads (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Temporal changes in insertion torque from the initial engagement through 25%, 50%, 75%, and 100% of engagement for (A) 6-mm-long, 1.75-mm-wide miniscrew implants (MSIs); (B) 3-mm-long, 1.75-mm-wide MSIs; and (C) 3-mm-long, 2.0-mm-wide MSIs.

There have been in vivo studies that support the clinical use of the 3-mm MSIs. Mortensen et al.19 recently reported success rates of 60% for 3-mm long, 1.75-mm wide, mandibular MSIs loaded with 900 or 600 g of force in dogs. After they eliminated the screws whose tips had sheared off during insertion and all the MSIs from one unusually active dog that regularly chewed its bowl and cage bars, the net success rates increased to 95.2%. In a series of experiments using rabbits, Liu et al. loaded 170 MSIs that were 3-mm long, 1.75-mm wide with continuous forces of up 200 g and had an overall success rate of 91.1%.20–22

The 3-mm MSIs with 2-mm outer diameters provided greater primary stability than those with a 1.75-mm outer diameter. When inserted into bone with a cortical density of 0.56 g/cc, the 0.25-mm difference in width resulted in a 12.4%–14.7% difference in IT. The positive effects that the outer diameter has on primary stability of MSIs have been previously emphasized.5,30,31 Because the wider outer diameter displaces more bone during insertion, it produces greater friction at the bone-screw interface, leading to greater IT. Interestingly, the same screws showed much smaller (5%–8.8%) differences in IT when they were inserted into denser cortical bone. This indicates that increases in purchase power associated with increases in the outer diameter of MSIs have less of an effect on denser bone.

Importantly, differences in POS related to MSI diameter were greater than the differences in IT (Figure 4). This indicates that the positive effects of the wider MSIs (ie, greater resistance to pullout) outweigh the potentially negative effects (ie, increased IT). These differences emphasize the importance of measuring both insertion torque and pullout in experiments performed to optimize MSI designs.

Figure 4.

Pullout strengths (means ± 2 standard deviations) of 6-mm and 3-mm miniscrew implants.

The results of this study indicate that the wider 3-mm MSIs provide a feasible alternative to the longer MSIs typically used by orthodontists. The drawbacks of longer screws pertain to the surrounding anatomic limitations.32,33 When MSIs are inserted into the periosteum or teeth, abnormal or no healing often takes place; it is not uncommon to find a lack of periodontal ligament or lack of bone regeneration, bone degeneration in the furcation area, ankylosis, or a total lack of healing associated with inflammatory infiltrate or pulpal invasion.17,18 The small increase in the outer diameter of a 3-mm MSI substantially compensates for the reduction in its length, providing an alternative that potentially avoids damage to the teeth and surrounding structures.

Significant increases of IT and POS occurred when MSIs were inserted into thicker cortical thickness. Decreasing cortical thickness by 50% (2 mm vs 1 mm) reduced IT and POS by 27%–32% and 15%–19%, respectively. Motoyoshi et al.13 and Huja et al.3 previously showed decreases in IT and POS with decreases in cortical thickness. Because the effects of cortical thickness were relatively greater on IT than POS, care must be taken when MSIs are placed in excessively thick cortical bone. For example, the cortical bone in the mandibular posterior region can be up to 3-mm thick33–35; thicker bone might be expected to increase strains and microfractures during insertion, which could affect healing and compromise secondary stability.

The IT of MSIs placed in high-density cortical bone was 13%–19% greater than IT of screws placed in low-density cortical bone; POS was 15%–16% greater. Increases in IT with greater bone density are well established in the prosthodontic and orthodontic literature.15,16,36,37 Greater bone density implies greater bone quantity, which requires higher torsional forces to advance the MSIs during insertion.24 Greater amounts of bone also increase the amount of bone-to-implant contact and greater engagement of bone by MSI threads, both of which contribute to increases in the POS.36

CONCLUSIONS

The shorter 3-mm MSIs had ITs and POSs that were 26%–33% and 69%–72% lower, respectively, than 6-mm MSIs.

Increasing the outer diameter by 0.25 mm significantly increased the primary stability; the 3 mm MSIs that were 1.75-mm wide had ITs and POSs that were 12%–14% and 13%–21% lower, respectively, than the 2.0-mm-wide MSIs.

Decreasing cortical thickness by 50% produced IT values that were 27%–32% lower and POS values that were 15%–19% lower.

Decreasing cortical density from 0.64 g/cc to 0.56 g/cc (12.5%) decreased IT and POS by 12%–19% and 5%–16%, respectively.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kyung H, Park H, Bae S, Sung J, Kim I. Development of orthodontic micro-implants for intraoral anchorage. J Clin Orthod. 2003;37:321–328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilmes B, Rademacher C, Olthoff G, Drescher D. Parameters affecting primary stability of orthodontic mini-implants. J Orofac Orthop. 2006;67:162–174. doi: 10.1007/s00056-006-0611-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huja S. S, Litsky A. S, Beck F. M, Johnson K. A, Larsen P. E. Pull-out strength of monocortical screws placed in the maxillae and mandibles of dogs. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2005;127:307–313. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2003.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hughes A. N, Jordan B. A. The mechanical properties of surgical bone screws and some aspects of insertion practice. Injury. 1972;4:25–38. doi: 10.1016/s0020-1383(72)80007-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DeCoster T. A, Heetderks D. B, Downey D. J, Ferries J. S, Jones W. Optimizing bone screw pullout force. J Orthop Trauma. 1990;4:169–174. doi: 10.1097/00005131-199004020-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hitchon P. W, Brenton M. D, Coppes J. K, From A. M, Torner J. C. Factors affecting the pullout strength of self-drilling and self-tapping anterior cervical screws. Spine. 2003;28:9–13. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200301010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen C, Chang C, Hsieh C, et al. The use of microimplants in orthodontic anchorage. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;64:1209–1213. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2006.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lim J. K, Kim W. S, Kim I. K, Son C. Y, Byun H. I. Three dimensional finite element method for stress distribution on the length and diameter of orthodontic miniscrew and cortical bone thickness. Korea J Orthod. 2003;33:11–20. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuroda S, Sugawara Y, Deguchi T, Kyung H, Takano-Yamamoto T. Clinical use of miniscrew implants as orthodontic anchorage: success rates and postoperative discomfort. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2007;131:9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2005.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Salmória K. K, Tanaka O. M, Guariza-Filho O, et al. Insertional torque and axial pull-out strength of mini-implants in mandibles of dogs. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2008;133:790.e15–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2007.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dalstra M, Cattaneo P. M, Melsen B. Load transfer of miniscrews for orthodontic anchorage. J Orthod. 2004;1:53–62. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Motoyoshi M, Inaba M, Ono A, Ueno S, Shimizu N. The effect of cortical bone thickness on the stability of orthodontic mini-implants and on the stress distribution in surrounding bone. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;38:13–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2008.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Motoyoshi M, Yoshida T, Ono A, Shimizu N. Effect of cortical bone thickness and implant placement torque on stability of orthodontic mini-implants. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2007;22:779–784. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beer A, Gahleitner A, Holm A, Tschabitscher M, Homolka P. Correlation of insertion torques with bone mineral density from dental quantitative CT in the mandible. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2003;14:616–620. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0501.2003.00932.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hung E, Oliver D, Kim K. B, Kyung H, Buschang P. H. Effects of pilot hole size and bone density on miniscrew implants' stability. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res. In press doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8208.2010.00269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang Z, Zhao Z, Xue J, et al. Pullout strength of miniscrews placed in anterior mandibles of adult and adolescent dogs: a microcomputed tomographic analysis. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2010;137:100–107. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2008.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brisceno C. E, Rossouw P. E, Carrillo R, Spears R, Buschang P. H. Healing of the roots and surrounding structures after intentional damage with miniscrew implants. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2009;135:292–301. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2008.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hembree M, Buschang P. H, Carrillo R, Spears R, Rossouw P. E. Effects of intentional damage of the roots and surrounding structures with miniscrew implants. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2009;135:280.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2008.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mortensen M. G, Buschang P. H, Oliver D. R, Kyung H. M, Behrents R. G. Stability of immediately loaded 3- and 6-mm miniscrew implants in beagle dogs—a pilot study. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2009;136:251–259. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2008.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu S. S, Kyung H, Buschang P. H. Continuous forces are more effective than intermittent forces in expanding sutures. Eur J Orthod. 2010;32:371–380. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cjp103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu S. S, Opperman L. A, Buschang P. H. Effects of recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 on midsagittal sutural bone formation during expansion. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2009;136:768.e1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2009.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu S. S, Opperman L. A, Kyung H. M, Buschang P. H. Is there an optimal force level for sutural expansion. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2011;139:446–455. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2009.03.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schwartz-Dabney C. L, Dechow P. C. Edentulation alters material properties of cortical bone in the human mandible. J Dent Res. 2002;81:613–617. doi: 10.1177/154405910208100907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carano A, Lonardo P, Velo S, Incorvati C. Mechanical properties of three different commercially available miniscrews for skeletal anchorage. Prog Orthod. 2005;6:82–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kido H, Schulz E. E, Kumar A, Lozada J, Saha S. Implant diameter and bone density: effect on initial stability and pull-out resistance. J Oral Implantol. 1997;23:163–169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Motoyoshi M, Uemura M, Ono A, et al. Factors affecting the long-term stability of orthodontic mini-implants. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2010;137:588.e1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2009.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ren Y, Maltha J. C, Kuijpers-Jagtman A. M. Optimum force magnitude for orthodontic tooth movement: a systematic literature review. Angle Orthod. 2003;73:86–92. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(2003)073<0086:OFMFOT>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Proffit W. Contemporary Orthodontics 4th ed. St Louis, Mo: Mosby; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pierce W. A, Sucato D. J, Young S, Picetti G, Morgan D. M. Axial and tangential pullout strength of uni-cortical and bi-cortical anterior instrumentation screws. Trans Orthop Res Soc. 2003;28:abstract 543. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morarend C, Qian F, Marshall S. D, et al. Effect of screw diameter on orthodontic skeletal anchorage. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2009;136:224–229. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2007.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lim S, Cha J, Hwang C. Insertion torque of orthodontic miniscrews according to changes in shape, diameter and length. Angle Orthod. 2008;78:234–240. doi: 10.2319/121206-507.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Park J, Cho H. J. Three-dimensional evaluation of interradicular spaces and cortical bone thickness for the placement and initial stability of microimplants in adults. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2009;136:314.e1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2009.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Poggio P. M, Incorvati C, Velo S, Carano A. “Safe zones”: a guide for miniscrew positioning in the maxillary and mandibular arch. Angle Orthod. 2006;76:191–197. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(2006)076[0191:SZAGFM]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ono A, Motoyoshi M, Shimizu N. Cortical bone thickness in the buccal posterior region for orthodontic mini-implants. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;37:334–340. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2008.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Farnsworth D, Rossouw P. E, Ceen R. F, Buschang P. H. Cortical bone thickness at common mini-screw implant placement sites. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop. 2011;139:495–503. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2009.03.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Friberg B, Sennerby L, Gröndahl K, et al. On cutting torque measurements during implant placement: a 3-year clinical prospective study. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res. 1999;1:75–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8208.1999.tb00095.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cha J, Kil J, Yoon T, Hwang C. Miniscrew stability evaluated with computerized tomography scanning. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2010;137:73–79. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2008.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]