Abstract

The in vitro mating ability of Candida lusitaniae (teleomorph Clavispora lusitaniae) clinical isolates has been investigated. Studying the effects of culture conditions, we showed that ammonium ion depletion in the medium is a major trigger of the sexual cycle. Moreover, a solid support is required for mating, suggesting a role for adhesion factors in addition to the mating type gene recognition function. Monitoring of mating and meiosis efficiency with auxotrophic strains showed great variations in ascospore yields, which appeared to be strain and temperature dependent, with an optimal range of 18 to 28°C. The morphogenetic events taking place from mating to ascospore release were studied by scanning and electron microscopy, and the ultrastructure of the conjugation canal, through which intercellular nuclear exchanges occur, was revealed. Labeling experiments with a lectin-fluorochrome system revealed that the nuclear transfer was predominantly polarized, thus allowing a distinction between the nucleus donor and the nucleus acceptor strains. The direction of the transfer depended on the strain combination used, rather than on the genotypes of the strains, and did not appear to be controlled by the mating type genes. Finally, we demonstrated that all of the 76 clinical isolates used in this study were able to reproduce sexually when mated with an opposite mating type strain, and we identified a 1:1 MATa/MATα ratio in the collection. These results support the idea that there is no anamorph state in C. lusitaniae. Accordingly, the mating type test, which is easy to use and can usually be completed within 48 h, is a reliable alternative identification system for C. lusitaniae.

Candida lusitaniae is now well documented as an emerging human opportunistic pathogen (8, 22). Albeit much less frequent than other Candida species, C. lusitaniae has been described as a nosocomial agent (4, 26, 30) and can cause severe fungemia in immunocompromised hosts. In some cases, therapeutic failure has been correlated with the propensity of this yeast to acquire antifungal resistance, mainly to amphotericin B (6, 18, 23, 36) but also to azoles (1) and to flucytosine (26). Most of the resistance events can easily be explained by mutations, whose expression is favored by the haploid genetic status of this species. Surprisingly, it was recently reported that a high rate of amphotericin B resistance could also result from an unusual mechanism of switching from susceptible to resistant phenotypes (37).

In such a context, careful attention should be paid to an accurate identification of C. lusitaniae infection to avoid the danger of selecting antifungal resistance during treatment. Unfortunately, routine identification of C. lusitaniae by conventional means (colony morphology and metabolic characteristics) may prove lengthy (up to 72 h) and difficult (21). A series of misidentifications have led in the past to confusion with C. parapsilosis (9, 23, 29), C. tropicalis (6, 19), and even Saccharomyces cerevisiae (7). Identification relying upon carbon assimilation (rhamnose) and fermentation (cellobiose) may sometimes be insufficient for clear distinction from atypical C. tropicalis (5). Advances in molecular biology have provided a set of DNA-based tools for the characterization of Candida species, including C. lusitaniae. However, few of these organisms have been identified to the species level (17, 31), and the great majority of the tools have been developed for epidemiological purposes (11, 20, 26, 33, 35).

On the other hand, sexual reproduction within the genus Candida is a diagnostic element that has been underestimated thus far. Indeed, among the 21 Candida species described as human pathogens, 13 have the potential to reproduce sexually (8). Interestingly, the four species most frequently isolated from cases of fungemia, i.e., C. albicans, C. tropicalis, C. parapsilosis, and C. glabrata, have no known sexual cycle, even though recent experiments with genetically modified C. albicans strains have demonstrated that in vitro mating and in vivo mating are at least possible (10, 16). Taking advantage of this fact, we investigated whether the sexual cycle of C. lusitaniae could be used to provide additional information for its reliable identification. The teleomorph of C. lusitaniae (Clavispora lusitaniae) is a heterothallic ascomycete yeast (28). The sexual cycle is controlled by the biallelic locus MATa/MATα. Mating is possible only between two haploid cells of opposite mating types. Meiosis gives rise to clavate, echinulate ascospores that are liberated by ascus disruption (5, 12, 28). Like that of many other yeasts and fungi, the sexual cycle is triggered and completed during nutrient starvation.

In this study, we first evaluated the culture conditions supporting the in vitro sexual cycle of C. lusitaniae. The meiosis efficiency was then measured at different incubation temperatures using two different combinations of sexually compatible auxotrophic mutants. The major cytological events leading to ascospore formation were characterized by scanning and transmission electron microscopy. Labeling cells with concanavalin A (ConA)-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) before conjugation of different sexually compatible strains enabled us to distinguish the nucleus donor cell from the nucleus acceptor cell, the latter being the cell which undergoes meiosis and turns into the ascus. Finally, we studied the sexual reproduction ability and determined the mating types of a collection of 76 isolates recovered from 60 humans in a hospital context. We demonstrate that sexual reproduction can be used as a criterion for C. lusitaniae identification, and we question the existence of anamorphs in this species.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

C. lusitaniae reference strains and isolates.

Mating type determination was performed with a total of 78 strains and isolates. The collection included 2 reference strains, 6936 MATa and 5094 MATα (Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures, Baarn, The Netherlands), and 76 isolates recovered from patients hospitalized in intensive care units. Among them, 4 isolates were derived from the University of Texas—Houston Medical Center (15) and were recovered from 4 patients; 72 isolates were derived from five French medical centers, some of them already having been described (3, 21, 25), and were recovered from 56 patients (multiple isolates were obtained from some patients: 2 isolates from 8 patients, 3 isolates from 2 patients, and 5 isolates from 1 patient ). Clinical isolates were recovered from the upper respiratory tract (n = 34), mouth (n = 7), sputum (n = 4), stools (n = 9), urine (n = 9), bedsore tissue (n = 1), vagina (n = 2), blood (n = 9), and intravenous catheter (n = 1). Identification was performed by standard methods (34) and with the API 32C system (bioMérieux, Marcy l'Etoile, France).

Reference strains 6936 and 5094 were used as mating type tester strains. During the course of this study, strain 5094 MATα was replaced by clinical isolate Cl38 MATα, which exhibited a better mating ability. In addition to strains 6936 and 5094, clinical isolates Cl38, Cl52 MATα, and Cl69 MATa were also used for nutritional requirement and ConA experiments.

Auxotrophic mutants.

Auxotrophic strains 14/31 MATα Leu−, 5/31 MATa Leu−, 69/2 MATα Lys−, and 69/3 MATa Lys− were derived from ethyl methanesulfonate mutagenesis of reference strain 6936, followed by nystatin enrichment according to standard genetic methods (2). The genome of initial mutants was purified once by a genetic cross with strain 5094 MATα, and MATα auxotrophic progeny were then purified by three successive backcrosses with strain 6936 MATa. The method for isolating ascospores derived from the crosses will be described elsewhere (unpublished data). Genetic analyses showed that mutations in the leucine and lysine pathways affected a single gene, were recessive, were genetically unlinked, and were unlinked to mating type genes (data not shown).

Other yeast species.

Various yeast species were assayed in negative control mating tests with C. lusitaniae: C. albicans (ATCC 2091), C. tropicalis (CBS 94), C. parapsilosis (ATCC 22019), C. famata (Debaryomyces hansenii; CBS 1795), C. (Pichia) guillermondii (CBS 6021), C. (Metschnikowia) pulcherrima (IP 82363 [Institute Pasteur]), and S. cerevisiae FL100 MATa (ATCC 28383) and FL200 MATα (ATCC 32119).

Media and culture conditions.

C. lusitaniae was routinely cultivated on YPD medium (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 2% dextrose) at 35°C. The solid media yeast nitrogen base with amino acids and ammonium sulfate (YNB [concentration, 0.67%]; Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) and yeast carbon base (YCB [concentration, 1.17%]; Difco), supplemented or not with various nitrogen sources, were tested for their ability to induce and support the sexual cycle. YNB was also used for selecting the recombinant prototrophic meiotic products released from crosses between auxotrophic parents.

Mating type tests and crosses.

For the determination of the mating type of an unknown isolate, cells of the isolate and of the reference mating type tester strains 6936 MATa and 5094 MATα (or Cl38 MATα) were separately cultivated to stationary phase in 2 ml of liquid YPD medium under agitation (250 rpm) at 35°C for 16 h (ca. 2 × 108 cells/ml). Equal volumes of the cell suspension (typically 500 μl) from the isolate were distributed in two 1.5-ml microtubes. To one tube was added 500 μl of the MATa tester strain culture, and to the other was added 500 μl of the MATα tester strain culture. The cell mixtures were centrifuged (3 min, 1,000 × g 20°C), and the cell pellet was resuspended with 500 μl of distilled sterile water to obtain a cellular concentration of about 4 × 108 to 5 × 108 cells/ml. Aliquots of 5 μl from each mixture were spotted on solid YCB medium. After 24 to 72 h of incubation at room temperature, cells were removed from the spots with a toothpick and examined in a drop of water with a light microscope (magnification, ×400), ideally in phase contrast. The presence of asci and ascospores indicated that the two strains tested had opposite mating types; the lack of asci and ascospores indicated that the two strains tested had the same mating type. Genetic crosses were performed under the same conditions by mixing cells with opposite mating types. The mating type protocol may be modified in order to save time. Cell suspensions can be made by dispersing fresh colonies isolated from complete solid medium in sterile water.

Scanning and transmission electron microscopy.

Yeast cells were mixed in a 1.5-ml microtube with 2% low-melting-point agarose (maintained at 30°C) and centrifuged (3,000 × g, 5 min). After the sample was cooled to 15°C, the solidified pellet was dissected into 1- to 2-mm3 pieces, which were fixed in a mixture of 2% glutaraldehyde and 0.5% paraformaldehyde in pH 7 0.1 M McIlvaine citrate-phosphate buffer and postfixed in 0.5% OsO4 (24). After successive dehydration in ethanol and propylene oxide, the samples were embedded in Spurr's (32) low-viscosity resin. Ultrathin (70-nm thick) sections were collected on Formvar-coated copper grids, stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate (27), and observed at 80 kV in a Philips CM 120 electron microscope.

ConA-FITC labeling of cells.

ConA-FITC (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) labeling was performed with 10 mM MES (2[N-morpholino]ethanesulfonic acid; Sigma) buffer (pH 5.4) by mixing 50 μl of a 10-mg/ml ConA-FITC solution with 500 μl of a MES-washed overnight yeast culture. After 1 h of incubation at room temperature and three washes with 1 ml of MES buffer, labeled cells were mixed with unlabeled cells of an opposite mating type and the mixture was spotted on solid YCB medium. After 96 h of incubation, the mating reaction was observed with a Zeiss fluorescence photomicroscope.

RESULTS

Triggering and completion of the sexual cycle in vitro.

Using a mixture of cells from the 6936 MATa and 5094 MATα reference strains, we first tested the solid media previously described as supporting the sexual cycle of C. lusitaniae, i.e., Gorodkowa, sodium acetate, diluted potato dextrose agar (5), and 1% malt agar (28). None of these media was as effective in our experiments as YCB medium (12) in term of swiftness (conjugation events observed within 16 to 48 h) and quantity of ascospores released (within 24 to 72 h). In order to determine the nutritional deprivation signal that triggers the sexual cycle, we further compared the efficiencies of YCB and YNB media. The media are comparable, since they have the same composition, except for the main carbon and nitrogen sources: YCB contains 1% glucose and no ammonium sulfate, whereas YNB contains 0.5% ammonium sulfate and no glucose. Different compatible combinations of strains 6936 and 5094 and of isolates Cl38 and Cl69, together with pure cultures of each, were assayed on YNB and YCB, the latter being supplemented or not with various nitrogen sources. The production of asci and ascospores was monitored over a period of 10 days. The results obtained with the different strain combinations were comparable; only those for 6936 and 5094 are presented (Table 1). As expected, ascospores could be detected only in the 6936–5094 cellular mixture under given conditions and not from the pure cultures, a result which confirmed the heterothallic behavior of these strains. Ascospores were produced on YCB but not on YNB, a result which suggests that mating is triggered in response to nitrogen but not carbon starvation. Supplementing YCB with potassium nitrate or urea had no inhibitory effect on the mating reaction relative to the results obtained with unsupplemented YCB. On the other hand, increasing the ammonium sulfate concentration from 0.01% to either 0.1 or 0.25% resulted in mating inhibition. This result suggests that depletion of ammonium ions could be a major signal for the triggering of the sexual cycle. Nevertheless, other conditions are required for the induction of the sexual cycle. For instance, mating did not occur in liquid YCB. A solid support seems to be required for mating, either because cells of opposite mating types need a prolonged period of contact for recognition or because the morphogenetic events leading to conjugation can take place only with immobilized cells.

TABLE 1.

Effect of nutritional factors on triggering of the sexual cycle

| Strain(s) | Result obtained with culture mediuma

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YCB alone | YCB supplemented with:

|

YNB | |||||

| KNO3 at 0.5% | Urea at 0.5% | (NH4)2SO4

|

|||||

| 0.01%b | 0.1%b | 0.25%b | |||||

| 6936 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 5094 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 6936-5094 | + | + | + | + | − | − | − |

Containing 2% agar. + or −, presence or absence, respectively, of conjugating cells and ascospores. Pseudofilaments were concomitantly observed for both strains and the strain combination on all culture media, except for YCB supplemented with 0.1 or 0.25% (NH4)2SO4.

Concentration of (NH4)2SO4.

Monitoring the meiotic yield on the basis of the temperature and time of incubation.

During the study of nutritional factor requirements, we observed variations in mating efficiencies and ascospore yields depending on the strain combinations used. For example, mating between 6936 and 5094 was slower and yielded consistently fewer ascospores than mating between 6936 and Cl38. In order to better quantify the variations in mating efficiencies, we monitored the ascospore yields from two genetic crosses involving auxotrophic strains on the basis of the temperature and incubation time. Each parent of the cross harbored a single-gene recessive mutation affecting either the leucine or the lysine biosynthetic pathway. A preliminary mating experiment allowed us to select strains with high and low mating abilities.

After mating auxotrophic parents on solid YCB supplemented with both leucine and lysine, we incubated petri dishes at five different temperatures (10, 18, 23, 28, and 37°C). Controls consisted of plating of pure cultures of each auxotrophic parent under the same conditions. At the end of each incubation period (24, 48, 72, and 96 h), a whole spot was removed and cells were resuspended in 1 ml of sterile water. Appropriate dilutions were plated on complete YPD medium to determine the total number of CFU contained in the suspension and on minimal YNB medium to determine the number of prototrophic colonies. In the mating experiments, the parental cells and the ascospores that had inherited one or both parental mutations could no longer grow on YNB. Only recombinant prototrophic meiotic products that had inherited both wild-type alleles from the parents were able to grow on YNB. The parental mutations being genetically unlinked, the prototrophic progeny statistically represented 25% of the total progeny derived from meiosis.

The results obtained from both crosses (Table 2) clearly indicated that the optimal incubation temperature for mating and meiosis was within the 18 to 28°C range. Observing cells under a microscope showed that the mating reaction was considerably slower at 10°C (scarcity or lack of conjugates). Unexpectedly, almost all cells from both crosses had entered conjugation by as early as 24 h of incubation at 37°C, but very few meiotic products were released, suggesting that meiosis is inefficient at a high temperature. Results also showed great variations in ascospore yield from the two crosses tested. In the optimal temperature range, the meiotic products from the cross 14/31 × 69/3, which had a high mating potential, represented as much as 10% of the total CFU at 24 h, 30% at 48 h, and 50 to 70% at 72 to 96 h of incubation, while the cross 5/31 × 69/2, which had a low mating potential, yielded nearly 1,000 times fewer meiotic products.

TABLE 2.

Assessment of mating and meiosis efficiencies in two genetic crosses with auxotrophic mutants on the basis of temperature and incubation timea

| Cross | Temp (°C) | Incubation time (h) | Mean ± SD

|

Ratio of meiotic products to CFU (1:) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total CFU/spot (107)b | % Meiotic products/spotc | ||||

| 14/31 MATα Leu− × 69/3 MATa Lys− | 10 | 24 | 1.15 ± 0.73 | 0.00 | |

| 48 | 1.58 ± 0.35 | 0.05 ± 0.005 | 2.2 × 103 | ||

| 72 | 1.95 ± 0.22 | 0.09 ± 0.005 | 1.2 × 103 | ||

| 96 | 1.62 ± 0.68 | 0.16 ± 0.069 | 7.0 × 102 | ||

| 18 | 24 | 0.94 ± 0.40 | 13.1 ± 2.5 | 8.0 | |

| 48 | 1.59 ± 0.58 | 37.8 ± 4.6 | 2.7 | ||

| 72 | 1.57 ± 0.62 | 56.9 ± 4.8 | 1.8 | ||

| 96 | 1.76 ± 0.47 | 57.1 ± 15.0 | 1.8 | ||

| 23 | 24 | 1.16 ± 0.41 | 12.1 ± 8.9 | 7.2 | |

| 48 | 0.94 ± 0.22 | 30.3 ± 8.4 | 3.2 | ||

| 72 | 1.24 ± 0.79 | 47.2 ± 3.8 | 2.2 | ||

| 96 | 1.53 ± 0.14 | 57.2 ± 23.2 | 1.8 | ||

| 28 | 24 | 1.30 ± 0.57 | 11.5 ± 6.1 | 9.5 | |

| 48 | 1.25 ± 0.82 | 36.9 ± 6.8 | 2.6 | ||

| 72 | 0.73 ± 0.24 | 66.5 ± 9.7 | 1.6 | ||

| 96 | 1.35 ± 0.23 | 68.7 ± 5.9 | 1.5 | ||

| 37 | 24 | 1.10 ± 0.63 | 0.05 ± 0.02 | 1.9 × 103 | |

| 48 | 1.77 ± 0.59 | 0.04 ± 0.03 | 2.7 × 103 | ||

| 72 | 2.10 ± 0.46 | 0.06 ± 0.03 | 1.6 × 103 | ||

| 96 | 1.23 ± 0.32 | 0.09 ± 0.03 | 1.2 × 103 | ||

| 5/31 MATa Leu− × 69/2 MATα Lys− | 10 | 24 | 0.99 ± 0.37 | 0.00 | |

| 48 | 2.16 ± 0.45 | 0.00 | |||

| 72 | 1.64 ± 0.96 | 0.00 | |||

| 96 | 1.45 ± 0.47 | 0.00 | |||

| 18 | 24 | 1.41 ± 0.37 | 0.006 ± 0.001 | 1.6 × 104 | |

| 48 | 1.44 ± 0.28 | 0.013 ± 0.008 | 7.4 × 103 | ||

| 72 | 1.77 ± 0.12 | 0.022 ± 0.001 | 4.6 × 103 | ||

| 96 | 1.14 ± 0.28 | 0.054 ± 0.021 | 1.8 × 103 | ||

| 23 | 24 | 3.00 ± 0.84 | 0.007 ± 0.002 | 1.4 × 104 | |

| 48 | 1.53 ± 0.10 | 0.014 ± 0.008 | 8.8 × 103 | ||

| 72 | 1.72 ± 0.74 | 0.021 ± 0.005 | 4.9 × 103 | ||

| 96 | 1.76 ± 0.12 | 0.027 ± 0.011 | 3.7 × 103 | ||

| 28 | 24 | 1.20 ± 0.45 | 0.009 ± 0.006 | 1.3 × 104 | |

| 48 | 2.13 ± 0.54 | 0.027 ± 0.011 | 3.6 × 103 | ||

| 72 | 1.28 ± 0.11 | 0.016 ± 0.009 | 6.1 × 103 | ||

| 96 | 2.33 ± 0.44 | 0.014 ± 0.013 | 6.5 × 103 | ||

| 37 | 24 | 1.73 ± 0.54 | 0.0003 ± 0.0001 | 3.7 × 105 | |

| 48 | 1.72 ± 0.28 | 0.0010 ± 0.0001 | 1.0 × 105 | ||

| 72 | 1.94 ± 0.14 | 0.0015 ± 0.0004 | 6.9 × 104 | ||

| 96 | 1.33 ± 0.18 | 0.0021 ± 0.0008 | 5.0 × 104 | ||

Data were obtained from three (cross 14/31 × 69/3) and two (cross 5/31 × 69/2) independent experiments (including different precultures).

Crosses were made on solid YCB medium supplemented with leucine and lysine (40 μg/ml each). At the end of each incubation time, the total number of CFU contained in one spot was determined after suspending cells in 1 ml of sterile water and plating adequate dilutions on solid complete YPD medium.

The percentage of meiotic products derived from ascospore germination was extrapolated from the number of prototrophic Leu+ Lys+ colonies able to grow on solid minimal YNB medium. Meiotic products represented the number of prototrophs × 4, knowing that the single-gene recessive mutations carried by both parents are genetically unlinked and that the mutants are unable to spontaneously reverse to prototrophy at a frequency of less than 10−8. These results were confirmed by plating pure cultures of each parent on YNB, which did not give rise to any prototrophic colony. The number of prototrophic colonies that can arise from the growth of heterokaryotic (or diploid) conjugates becomes negligible once ascospore release has begun (unpublished observations).

Major cytological events of the sexual cycle.

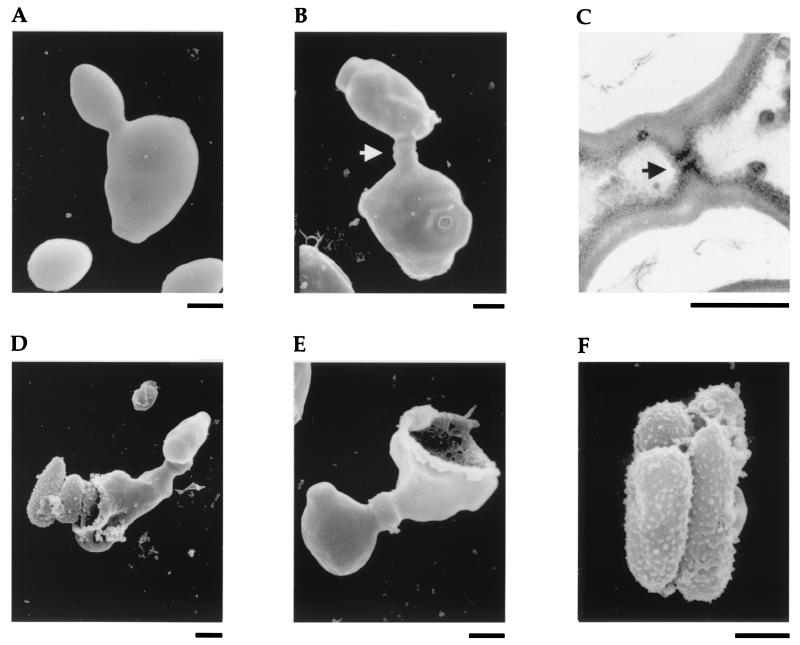

The cytological events leading to ascospore formation were characterized by scanning and transmission electron microscopy. A cross was made on YCB between reference strain 6936 MATa and clinical isolate Cl38 MATα, which were selected because they produced high levels of ascospores when mated together. Samples of cell mixtures were removed from solid YCB medium after 24, 48, and 72 h of incubation and resuspended in sterile distilled water before being processed for electron microscopy. A clear discrimination could be made between budding yeast cells (Fig. 1A) and conjugating cells (Fig. 1B), owing to the length of the bulging conjugation canal showing a slight constriction at midlength. The ultrastructure of the conjugation canal was better characterized by transmission electron microscopy (Fig. 1C). The cell walls of both partners were tightly merged and formed a perforated septum at the cell junction, through which nuclear transfer from one cell to the other could occur. Conjugated forms were predominantly observed after 24 h of incubation on YCB. Ascospores released by ascus disruption (deliquescence) were detected after 48 h of incubation (Fig. 1D). After 72 h of incubation, numerous disrupted empty asci (Fig. 1E) and free ascospores (Fig. 1F) were easily distinguishable among all other cellular forms. The photographs show that the ascospores are clavate and echinulate. A material that could be traces of ascus cytoplasm often made them stick together. Note that conjugated forms and disrupted asci are easily observable using a simple routine light microscope with a ×40 objective, preferably with phase contrast.

FIG. 1.

Major cytological events of the sexual cycle. (A) Budding yeast cell in a pure culture. (B) Conjugation between MATa and MATα cells showing the conjugation canal with its constriction at midlength (arrow). (C) Detail of the conjugation canal showing the merged cell walls and the perforated septum (arrow). (D) Release of ascospores by ascus disruption. (E) Empty ascus (right part) and its head cell (left part). (F) Tetrad of clavate, echinulate ascospores. Scale bars, 1 μm. (A, B, D, E, and F) Scanning electron microscopy. (C) Transmission electron microscopy. Magnifications were about ×11,640 (A, B, and D), ×14,550 (E), ×19,400 (F), and ×37,830 (C).

Completion of the sexual cycle in C. lusitaniae can be summarized as follows. First, cells of opposite mating types conjugate (plasmogamy). The nucleus of one cell then moves across the conjugation canal to undergo karyogamy and meiosis with the nucleus of the partner cell, which consequently turns into the ascus. Finally, the meiotic products form ascospores, which are liberated by ascus disruption.

Study of nuclear transfer.

Meiosis in C. lusitaniae leads to a clear distinction between the nucleus acceptor cell, which turns into the ascus, and the nucleus donor cell (the “head” cell), which remains unchanged. Such cellular dimorphism led us to investigate whether the nuclear transfer occurred randomly between the partners of a conjugated form or whether it was directional, i.e., did cells of one strain always act as nucleus donors and did cells of the opposite mating type always act as nucleus acceptors? In order to answer that question, cells of one strain were labeled with ConA-FITC before being mated with unlabeled cells of the opposite mating type. Three different compatible strain combinations were used, each strain being alternatively labeled, and fluorescence was detected after mating (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Location of ConA-FITC on mature disrupted conjugates from different crosses

| Cross with the following strain:

|

Location of fluorescence (% of labeled disrupted conjugatesa)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Unlabeled | Labeled | Head cell (nucleus donor) | Ascus (nucleus acceptor) |

| Cl52 MATα | 6936 MATa | 83 | 17 |

| 6936 MATa | Cl52 MATα | 5 | 95 |

| Cl52 MATα | Cl69 MATa | 95 | 5 |

| Cl69 MATa | Cl52 MATα | 5 | 95 |

| Cl38 MATα | 6936 MATa | 8 | 92 |

| 6936 MATa | Cl38 MATα | 50 | 50 |

Disrupted conjugates correspond to empty cellular structures after ascospores have been released (see Fig. 1D). For all crosses, results were confirmed by two independent experiments with ConA-FITC (three for 6936 × Cl38) and an additional experiment with ConA-peroxidase. Variations in percentages did not exceed 2%.

In the majority of cases, fluorescence was located either on the head cell (nucleus donor cell) or on the ascus (nucleus acceptor cell), depending on the labeled strain. These results indicated that nuclear transfer was predominantly polarized during mating. However, the nucleus donor strain in one cross combination could play the role of the nucleus acceptor when mated with another strain, as observed for strain 6936, which was the donor when mated with Cl52 and the acceptor when mated with Cl38. The results obtained from the cross 6936 × Cl38, which were confirmed in three independent experiments, are intriguing and remain unexplained. Labeling of strain 6936 indicated that nuclear transfer was polarized (in 92% of the conjugates, 6936 acted as the nucleus acceptor). Unexpectedly, labeling of Cl38 did not provide confirmation that this strain behaved as the nucleus donor, the nuclear transfer occurring randomly.

Determination of the mating types of clinical isolates.

In order to determine whether clinical isolates of C. lusitaniae had retained their ability to undergo meiosis, we studied the sexual cycle and attempted to determine the mating types for a collection of 76 strains isolated from 60 patients. This determination was done in two steps. In the first set of experiments, 41 strains, including 2 reference strains and 39 clinical isolates, were paired in all possible combinations {resulting in [n × (n − 1]/2 = 820 mating combinations, with n = 41}. This was done in order to verify that there was no abnormality in the mating reaction, i.e., to ascertain that each isolate was able to mate with all other isolates of the opposite mating type and not with all other isolates of the same mating type. Nevertheless, this study could not be realized with the whole sample because it would have resulted in too many mating reactions (3,003 exactly). Accordingly, in the second set of experiments, the mating types of the remaining 37 clinical isolates were determined by pairing with reference strain 6936 MATa and clinical isolate Cl38 MATα.

The results are summarized in Table 4. All clinical isolates were able to undergo meiosis when mated with a sexually compatible reference strain. From the first set of results, we could extrapolate that they were also able to reproduce sexually when mated with each other in compatible combinations. Multiple isolates from a same patient had the same mating type, consistent with the idea that they could belong to the same strain. No deviation from an equal distribution of mating types MATa and MATα could be observed in the sample of clinical isolates, either when the whole sample was considered or when the analysis was restricted to a single strain per patient. Finally, no correlation was found between the mating types of the isolates and their human biological isolation sites.

TABLE 4.

Assignment of mating types and MATa/MATα ratios in a collection of 76 C. lusitaniae clinical isolates

| Origin | Result of analysis with:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All isolates

|

A single isolate/patient

|

|||

| No. | MATa/MATα | No. | MATa/MATα | |

| Respiratory tract | 34 | 20:14 | 26 | 16:10 |

| Hemoculture | 9 | 7:2 | 8 | 6:2 |

| Urine | 9 | 3:6 | 6 | 2:4 |

| Stools | 9 | 4:5 | 8 | 3:5 |

| Mouth | 7 | 3:4 | 5 | 2:3 |

| Sputum | 4 | 2:2 | 3 | 2:1 |

| Vagina | 2 | 1:1 | 2 | 1:1 |

| Sloughed skin | 1 | 1:0 | 1 | 1:0 |

| Venous catheter | 1 | 0:1 | 1 | 0:1 |

| Total | 76 | 41:35 | 60 | 33:27 |

Specificity of the mating test.

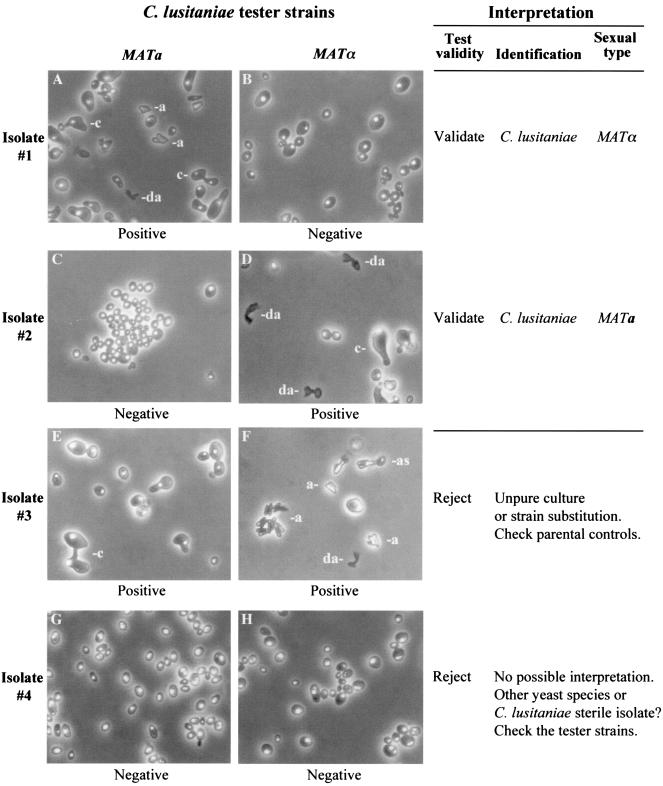

Since all 76 tested clinical isolates showed sexual reproduction, our results support the idea that the mating test could be used as a complementary identification tool for C. lusitaniae. With that idea in mind, we ascertained that other yeast species (see Materials and Methods) which are sometimes mistaken for C. lusitaniae did not react with C. lusitaniae during a mating test. Each strain was assayed in pure cultures on YCB and subjected to mating experiments with both 6936 and Cl38. No positive mating reaction comparable to those shown in Fig. 2 could be detected, even after 10 days of incubation.

FIG. 2.

Examples of positive and negative mating reactions with C. lusitaniae, as observed by phase-contrast microscopy, and proposal for interpreting all the results that could arise from mating an unknown isolate with mating type tester strains. (A, D, E, and F) Representative set of different cellular structures observable from one positive mating reaction after 24 h of incubation. (B, C, G, and H) Negative mating reactions after 96 h of incubation. a, ascospores; as, ascus; c, conjugated cells; da, disrupted ascus. Magnification, ×300.

Carrying out and interpreting a mating test in a clinical laboratory.

Carrying out a mating test means determining the mating ability and the sexual type of an unknown isolate. For a routine mating test with C. lusitaniae, it is of primary interest to select MATa and MATα tester strains having a high mating potential. This step is particularly important for rapid and easy interpretation. The test consists of mixing cells of the isolate and of both tester strains separately (two mating reactions) and spotting cell mixtures on solid YCB. Negative control reactions can be carried out by spotting a pure suspension of each strain, and positive control reactions can be carried out by mating the tester strains together. Incubation at room temperature is convenient, and it is generally not necessary to prolong incubation beyond 72 h. In our experiments, the majority of the tests could be read with a phase-contrast microscope at 24 h. Some examples of positive and negative mating reactions, with a guideline for interpretation, are presented in Fig. 2. An unknown isolate can be unambiguously identified as a C. lusitaniae strain when mating occurs with only one of the mating type tester strains. In any other situation, the test cannot be interpreted. If no mating occurs with both tester strains, one cannot conclude that the isolate belongs to another yeast species, since we cannot completely preclude the existence of mating-defective isolates of C. lusitaniae. Nevertheless, if it does exist, this phenomenon should be rare, because we never observed it within our collection of 76 clinical isolates.

DISCUSSION

Mating in C. lusitaniae is readily obtained in vitro on solid medium in response to nitrogen starvation. We showed that ammonium ions are the major nitrogen source whose depletion triggers mating, a finding which is consistent with those of previous studies (12, 38). Other nitrogenous compounds (such as nitrates and urea) had no effect on mating, consistent with the fact that C. lusitaniae cannot assimilate these sources. A key role of ammonium in some important morphogenetic pathways is not surprising. In S. cerevisiae, under nitrogen starvation conditions, an ammonium permease is involved in signaling for triggering the pseudofilamentation pathway (14), which shares a common mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade with the mating pheromone response pathway (13). It is possible that C. lusitaniae uses analogous signaling cascades for both mating and pseudofilamentation. First, we observed that the nitrogen-lacking YCB medium used for mating allowed abundant differentiation of pseudohyphae, suggesting that both pathways respond to nitrogen starvation, although pseudofilamentation also responds to carbon starvation, while mating does not. Second, following ethyl methanesulfonate mutagenesis, we selected several pseudofilamentation-defective mutants, about half of which were concomitantly defective in mating.

Depletion of ammonium is necessary but not sufficient for completion of the sexual cycle, because we failed to observe mating in liquid YCB medium. A previous work reported the apparent lack of diffusible mating factors and of sexual agglutination in both C. opuntiae and C. lusitaniae and concluded that cell-to-cell contact was required for a mating response (12). The fact that in our experiments, mating and meiosis could occur only on a solid support is consistent with that idea. Furthermore, the electron microscopy analysis revealed that complete cell fusion during mating did not occur and that cellular exchange, notably, nuclear migration, was mediated through a conjugation canal about 1 μm long. The ultrastructure of the canal is rather complex: each of both partner cells differentiates a part of the canal, and at the junction, the cell walls appear tightly merged and form a septum which is perforated for allowing communication between cells. In a turbulent liquid environment, it is possible that weak adhesion strength between cells, combined with the relatively long period of time necessary to complete canal differentiation, constitutes an obstacle to conjugation attempts. Alternatively, it is reasonable to consider that cell-to-cell contact may require additional adhesion factors whose expression would be induced in response to a solid surface.

After conjugation, one cell turns into the ascus, where karyogamy and meiosis take place, and the other cell remains unchanged. Such cellular dimorphism during sexual reproduction led us to wonder whether nuclear transfer between two strains was polarized. Our results show that nuclear transfer is predominantly polarized. Cells of one strain act as nucleus donors, and cells of the sexually compatible strain act as nucleus acceptors. Using different isolates, we demonstrated that polarity depends on the strain combination and does not seem to be directly controlled by mating type genes. The cellular message involved in the determination of the nuclear transfer direction is not known, but we suspect that the lectin ConA may disturb this message. Indeed, the contradictory results obtained by labeling alternatively each strain in one cross (6936 × Cl38) could be explained by an interfering cellular activity of ConA.

The main goal of this study was to determine whether sexual reproduction could be used as a complementary identification system for C. lusitaniae. Of the 76 isolates tested, 100% were able to mate and to undergo meiosis when mixed with a sexually compatible strain of the opposite mating type. We verified that the clinical isolates were able to mate not only with reference strains but also with each other when associated in compatible combinations. We failed to detect any other genetic system, such as cytoplasmic incompatibility, in addition to the biallelic locus MATa/MATα, which controls the mating ability of two strains. Finally, no deviation from an equal distribution of the mating types MATa and MATα were observed in the sample. These results contrast with those of previous studies (5, 28, 38) which reported either the inability of some strains to reproduce sexually (“sterile” strains) or a marked imbalance in the MATa/MATα ratio or both. It should be emphasized that these previous studies were performed with much smaller samples (13, 9, and 5 strains, respectively) and with different culture conditions. From our experience, the emergence of sterile strains may be explained in several ways. First, we observed that the mating reactivity of C. lusitaniae was variable, some isolates exhibiting a high potential to mate and others having a lower reactivity. Monitoring mating and meiosis efficiencies in two different crosses of auxotrophic mutants provided evidence that high-mating-potential strains could yield up to 70% of meiotic products (relative to the total number of CFU) within 72 to 96 h of incubation in the optimal 18 to 28°C temperature range. In contrast, the ascospore yield from low-mating-potential strains was about 1,000 times lower, even though they were derived from the same lineage as high-mating-potential strains. Obviously, the use of a nonoptimal medium for mating poorly reactive strains, resulting in the release of few ascospores, may lead to a false interpretation. Second, some mutant strains can exhibit a sterile phenotype, such as pseudofilamentation-deficient mutants and some auxotrophic mutants, which can be prevented from mating until the medium is adequately supplemented. Third, a sterile phenotype may be assigned to a strain that has been misidentified as C. lusitaniae. In light of our results, there is no argument suggesting that an anamorphic state exists in clinical specimens of C. lusitaniae; all isolates analyzed are able to reproduce sexually and belong de facto to the species Clavispora lusitaniae (28). Accordingly, there is no reason to maintain two names for a species that is constituted by a homogeneous population with regard to sex. For historical and convenience reasons, it would be more advisable to keep the name Candida lusitaniae.

Imbalance in the mating type ratio is generally interpreted as a consequence of the loss of the ability to reproduce sexually, to the benefit of asexual dissemination. The fact that a 1:1 ratio for mating types a and α was observed in our sample leads us to speculate that sexual reproduction, i.e., meiosis, could still be used by C. lusitaniae as a source of genetic variability.

In our experiments, none of the media generally described as supporting the sexual reproduction of C. lusitaniae (5) was as effective as YCB medium, whose use was reported for mating the cactophilic yeast C. opuntiae (12). Conjugating cells, asci, and free ascospores were generally observed within 24 to 48 h after mixing and incubating in the 18 to 28°C temperature range two sexually compatible strains. This medium offers other advantages: it is delivered as a preformulated dehydrated powder and is completely synthetic, a feature which minimizes lot-to-lot variations. We verified that YCB did not support cross-mating reactions with reference strains from species that are sometimes mistaken for C. lusitaniae by standard methods (21) and thus confirmed a previous comparable work done with other Candida species (28). These data make the mating test suitable for C. lusitaniae identification.

Given that a clinical laboratory has mating type tester strains with a high potential to mate, developing a mating test is easy and inexpensive (a petri dish containing solid YCB medium costs less than U.S. $0.20). With a standard phase-contrast microscope, the results are simple to interpret by observing at least disrupted asci, which are easier to detect than ascospores. During a mating test, any C. lusitaniae isolate is supposed to mate with only one tester strain and not the other, depending on its sexual type. This is the sole situation in which a yeast isolate can be unambiguously identified as C. lusitaniae from a mating test. Thus, the mating test allows easy verification that takes no longer than any other identification system, and we believe that it is a reliable complementary tool in case of doubtful identification of C. lusitaniae.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Annie Michel-Nguyen (Laboratoire de Microbiologie, Hôpital St Joseph, Marseille, France), who isolated and identified most of the strains used in this study in collaboration with Anne Favel.

REFERENCES

- 1.Blinkhorn R J, Adelstein D, Spagnuolo P J. Emergence of a new opportunistic pathogen, Candida lusitaniae. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:236–240. doi: 10.1128/jcm.27.2.236-240.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burke D, Dawson D, Stearns T. Methods in yeast genetics: a Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory course manual—2000 ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Favel A, Michel-Nguyen A, Chastin C, Trousson F, Penaud A, Regli P. In-vitro susceptibility pattern of Candida lusitaniae and evaluation of the Etest method. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1997;39:591–596. doi: 10.1093/jac/39.5.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fowler S L, Rhoton B, Springer S C, Messer S A, Hollis R J, Pfaller M A. Evidence for person-to-person transmission of Candida lusitaniae in a neonatal intensive-care unit. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1998;19:343–345. doi: 10.1086/647826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gargeya I B, Pruitt W R, Simmons R B, Meyer S A, Ahearn D G. Occurence of Clavispora lusitaniae, the teleomorph of Candida lusitaniae, among clinical isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:224–227. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.10.2224-2227.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guinet R, Chanas J, Goullier A, Bonnefoy G, Ambroise-Thomas P. Fatal septicemia due to amphotericin B-resistant Candida lusitaniae. J Clin Microbiol. 1983;18:443–444. doi: 10.1128/jcm.18.2.443-444.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hadfield T L, Smith M B, Winn R E, Rinaldi M G, Guerra C. Mycoses caused by Candida lusitaniae. Rev Infect Dis. 1987;9:1006–1012. doi: 10.1093/clinids/9.5.1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hazen K C. New and emerging yeast pathogens. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1995;8:462–478. doi: 10.1128/cmr.8.4.462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holzschu D L, Presley H L, Miranda M, Phaff H J. Identification of Candida lusitaniae as an opportunistic yeast in humans. J Clin Microbiol. 1979;10:202–205. doi: 10.1128/jcm.10.2.202-205.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hull C M, Raisner R M, Johnson A D. Evidence for mating of the “asexual” yeast Candida albicans in a mammalian host. Science. 2000;289:307–310. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5477.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.King D, Rhine-Chalberg J, Pfaller M A, Moser S A, Merz W G. Comparison of four DNA-based methods for strain delineation of Candida lusitaniae. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:1467–1470. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.6.1467-1470.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lachance M-A, Nair P, Lo P. Mating in the heterothallic haploid yeast Clavispora opuntiae, with special reference to mating type imbalances in local populations. Yeast. 1994;10:895–906. doi: 10.1002/yea.320100705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu H, Styles C A, Fink G R. Elements of the yeast pheromone response pathway required for filamentous growth of diploids. Science. 1993;262:1741–1744. doi: 10.1126/science.8259520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lorenz M C, Heitman J. Regulators of pseudohyphal differentiation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae identified through multicopy suppressor analysis in ammonium permease mutant strains. Genetics. 1998;150:1443–1457. doi: 10.1093/genetics/150.4.1443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lozano-Chiu M, Nelson P W, Lancaster M, Pfaller M A, Rex J H. Lot-to-lot variability of antibiotic medium 3 used for testing susceptibility of Candida isolates to amphotericin B. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:270–272. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.1.270-272.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Magee B B, Magee P T. Induction of mating in Candida albicans by construction of MTLa and MTLα strains. Science. 2000;289:310–313. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5477.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maiwald M, Kappe R, Sonntag H G. Rapid presumptive identification of medically relevant yeasts to the species level by polymerase chain reaction and restriction enzyme analysis. J Med Vet Mycol. 1994;32:115–122. doi: 10.1080/02681219480000161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Merz W G. Candida lusitaniae: frequency of recovery, colonization, infection, and amphotericin B resistance. J Clin Microbiol. 1984;20:1194–1195. doi: 10.1128/jcm.20.6.1194-1195.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Merz W G, Sandford G R. Isolation and characterization of a polyene-resistant variant of Candida tropicalis. J Clin Microbiol. 1979;9:677–680. doi: 10.1128/jcm.9.6.677-680.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Merz W G, Khazan U, Jabra-Rizk M A, Wu L C, Osterhout G J, Lehmann P F. Strain delineation and epidemiology of Candida (Clavispora) lusitaniae. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:449–454. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.2.449-454.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Michel-Nguyen A, Favel A, Chastin C, Selva M, Regli P. Comparative evaluation of a commercial system for identification of Candida lusitaniae. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2000;19:393–395. doi: 10.1007/pl00011231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nguyen M H, Peacock J E, Morris A J, Tanner D C, Nguyen M L, Snydman D R, Wagener M M, Rinaldi M G, Yu V L. The changing face of candidemia: emergence of non-Candida albicans species and antifungal resistance. Am J Med. 1996;100:617–623. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(95)00010-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pappagianis D, Collins M S, Hector R, Remington J. Development of resistance to amphotericin B in Candida lusitaniae infecting a human. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1979;16:123–126. doi: 10.1128/aac.16.2.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pépin R, Boumendil J. Préservation de l'ultrastructure du sclérote de Sclerotinia tuberosa (champignon discomycète). Un modèle pour la préparation des échantillons imperméables et hétérogènes. Cytologia. 1982;47:359–377. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peyron F, Favel A, Guiraud-Dauriac H, El Mzibri M, Chastin C, Dumenil G, Regli P. Evaluation of a flow cytofluorometric method for rapid determination of amphotericin B susceptibility of yeast isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:1537–1540. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.7.1537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pfaller M A, Messer S A, Hollis R J. Strain delineation and antifungal susceptibilities of epidemiologically related and unrelated isolates of Candida lusitaniae. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1994;20:127–133. doi: 10.1016/0732-8893(94)90106-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reynolds E S. The use of lead citrate at high pH as an electron opaque stain in electron microscopy. J Cell Biol. 1963;17:208–212. doi: 10.1083/jcb.17.1.208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rodrigues de Miranda L. Clavispora, a new yeast genus of the Saccharomycetales. Antonie Leeuwenhoek. 1979;45:479–483. doi: 10.1007/BF00443285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sanchez P J, Cooper B H. Candida lusitaniae sepsis and meningitis in a neonate. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1987;6:758–759. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sanchez V, Vazquez J A, Barth-Jones D, Dembry L, Sobel J D, Zervos M J. Epidemiology of nosocomial acquisition of Candida lusitaniae. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:3005–3008. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.11.3005-3008.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sandhu G S, Kline B C, Stockman L, Roberts G D. Molecular probes for diagnosis of fungal infections. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2913–2919. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.11.2913-2919.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Spurr A R. A low viscosity epoxy resin embedding medium for electron microscopy. J Ultrastruct Res. 1969;26:31–43. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5320(69)90033-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vazquez J A, Beckley A, Donabedian S, Sobel J D, Zervos M J. Comparison of restriction enzyme analysis versus pulsed-field gradient gel electrophoresis as a typing system for Torulopsis glabrata and Candida species other than C. albicans. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:2021–2030. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.8.2021-2030.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Warren N G, Hazen K C. Candida, Cryptococcus, and other yeasts of medical importance. In: Murray P R, Baron E J, Pfaller M A, Tenover F C, Yolken R H, editors. Manual of clinical microbiology. 6th ed. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1995. pp. 723–737. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xu J, Boyd C M, Livingston E, Meyer W, Madden J F, Mitchell T G. Species and genotypic diversities and similarities of pathogenic yeasts colonizing women. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:3835–3843. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.12.3835-3843.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yinnon A M, Woodin K A, Powell K R. Candida lusitaniae infection in the newborn: case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1992;11:878–880. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199210000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yoon S A, Vazquez J A, Steffan P E, Sobel J D, Akins R A. High-frequency, in vitro reversible switching of Candida lusitaniae clinical isolates from amphotericin B susceptibility to resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:836–845. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.4.836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Young L Y, Lorenz M C, Heitman J A. A STE12 homolog is required for mating but dispensable for filamentation in Candida lusitaniae. Genetics. 2000;155:17–29. doi: 10.1093/genetics/155.1.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]