ABSTRACT

Spontaneous severe acute exacerbation (SAE) is not uncommon in the natural history of chronic hepatitis B (CHB). Lamivudine (LAM) has the advantages of low price, quick onset, good efficacy, and no drug resistance within 24 weeks. This study aimed to compare the short-term efficacy of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) and LAM for 24 weeks followed by TDF in the treatment of CHB with severe acute exacerbation. Consecutive patients of CHB with SAE were randomized to receive either TDF (19 patients) or LAM for 24 weeks, followed by TDF (18 patients). The primary endpoint was overall mortality or receipt of liver transplantation by week 24. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the Kaohsiung Veterans General Hospital (VGHKS12-CT5-10). The baseline characteristics were comparable between the two groups. By week 24, seven (37%) and five (28%) patients in the TDF and LAM-TDF groups died or received liver transplantation (P = 0.487). Multivariate analysis showed that albumin level, prothrombin time (PT), and hepatic encephalopathy were independent factors associated with mortality or liver transplantation by week 24. Early reductions in HBV DNA of more than or equal to 2 log at 1 and 2 weeks were similar between the two groups. The biochemical and virological responses at 12, 24, and 48 weeks were also similar between the two groups. TDF and LAM for 24 weeks followed by TDF achieved a similar clinical outcome in CHB patients with SAE. (This study has been registered at ClinicalTrials.gov under identifier NCT01848743).

KEYWORDS: hepatitis B virus, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, lamivudine, acute exacerbation, exacerbation

INTRODUCTION

Chronic HBV (CHB) infection is an important global health problem, with an estimated 400 million HBV carriers worldwide (1–3). CHB with spontaneous acute exacerbation (AE) is not uncommon, and a cumulative incidence of approximately 10 to 30% annually has been reported (4–7). These exacerbations can be mild but may be accompanied by hepatic decompensation, and mortality may occur (7–9).

Lamivudine (LAM) is the first approved antiviral drug for the treatment of HBV infections (10). LAM is effective and has a good safety profile for the treatment of CHB patients who have a compensated or decompensated liver (11, 12). Several nonrandomized studies have found that LAM does not improve the survival rate of CHB patients or those with SAE (13, 14). Chien et al. (15) reported that early LAM treatment in CHB patients with SAE before their bilirubin (bil) level was >20 mg/dL and was associated with a better outcome. Another recent study by Sun et al. also showed that LAM treatment improved outcomes in patients, with a model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score of <30 (16).

However, several studies have demonstrated that LAM is associated with a high resistance rate in the treatment of CHB, especially if administered for >9 months (17–19). In several randomized studies, entecavir (ETV) resulted in better antiviral efficacy and a lower resistance rate than LAM did (20, 21). However, a recent study conducted in Hong Kong unexpectedly demonstrated that ETV increased the short-term mortality rate more than LAM did in CHB patients with SAE (22). Our recent study also showed that early ETV treatment was associated with worse outcomes than LAM in CHB patients with SAE presenting with a high viral load (23).

Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) is another potent inhibitor of HBV polymerase and has been approved for the treatment of CHB (24, 25). TDF has shown good efficacy in CHB patients with acute-on-chronic liver failure or a decompensated liver (26, 27). In a recent retrospective study, Hung et al. discovered that TDF and ETV achieved similar clinical outcomes in CHB patients with SAE (28). Park et al. also found, in a retrospective study, that LAM, ETV, and TDF showed similar clinical outcomes in CHB patients with SAE (29). Controversies exist in whether TDF or LAM should be chosen for the treatment of CHB patients with SAE. This randomized controlled study aimed to compare the short-term efficacy of TDF and LAM for 24 weeks followed by TDF in the treatment of CHB with SAE.

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics of study population.

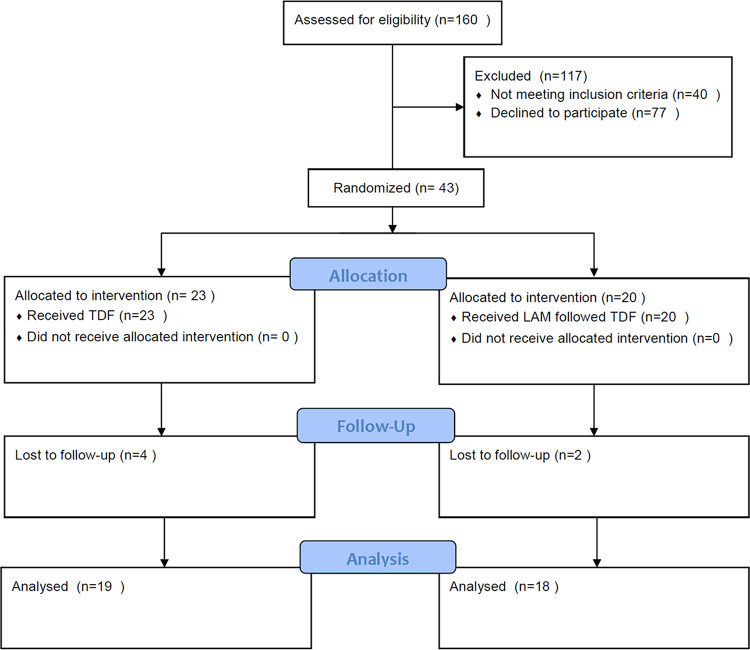

In this study, patients who fulfilled the inclusion and exclusion criteria, agreed to participate in the study, and signed informed consents were randomized to receive TDF (23 patients) and LAM for 24 weeks followed by TDF (LAM-TDF) (20 patients). However, 4 patients in the TDF group and 3 patients in the LAM-TDF group were lost to follow-up (Fig. 1). Nineteen patients who received TDF and 18 patients who received LAM followed by TDF entered the study and were analyzed. The values for baseline age, sex, alanine aminotransferase (ALT), bilirubin, prolongation of prothrombin time (PT), platelet, albumin, creatinine, HBV DNA level, MELD score, albumin-bilirubin (Albi) grade, HBeAg status, and presence of cirrhosis, ascites, or hepatic encephalopathy were similar between the two groups, but the TDF group had a higher aspartate aminotransferase (AST) level than the LAM-TDF group (Table 1).

FIG 1.

Flow of study participants who received TDF or LAM followed by TDF.

TABLE 1.

Demographic and clinical data in patients under TDF or LAM followed by TDF treatmenta

| Parameter | TDF (N = 19) | LAM-TDF (N = 18) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 57 ± 14 | 54 ± 12 | 0.268 |

| Male, n (%) | 13 (68) | 11 (61) | 0.737 |

| AST (U/liter) | 877 ± 482 | 649 ± 541 | 0.336 |

| ALT (U/liter) | 1,219 ± 704 | 1,084 ± 1,102 | 0.358 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.3 ± 0.5 | 3.4 ± 0.8 | 0.864 |

| Bilirubin (mg/dL) | 8.1 ± 6.5 | 7.5 ± 6.0 | 0.790 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 0.9 ± 0.2 | 0.116 |

| PT (INR) | 1.5 ± 0.4 | 1.5 ± 0.5 | 0.564 |

| Hb (mg/dL) | 13.9 ± 1.8 | 13.8 ± 1.9 | 0.822 |

| Platelet (cells × 109/ml) | 169 ± 90 | 171 ± 117 | 0.440 |

| HBeAg positive, n (%) | 8 (42) | 5 (28) | 0.495 |

| HBV DNA (log10 copies/ml) | 6.5 ± 2.0 | 5.0 ± 2.1 | 0.838 |

| MELD score | 15.7 ± 4.4 | 15.2 ± 5.2 | 0.736 |

| Cirrhosis, n (%) | 2 (11) | 5 (28) | 0.232 |

| Encephalopathy, n (%) | 3 (16) | 0 (0) | 0.230 |

| Ascites, n (%) | 1 (4.3) | 3 (15) | 0.340 |

| Mortality/transplantation, n (%) | 7 (37) | 5 (28) | 0.728 |

AST, Aspartate transaminase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AFP, α-fetoprotein; Hb, hemoglobin; MELD, model for end-stage liver disease.

Mortality or liver transplantation.

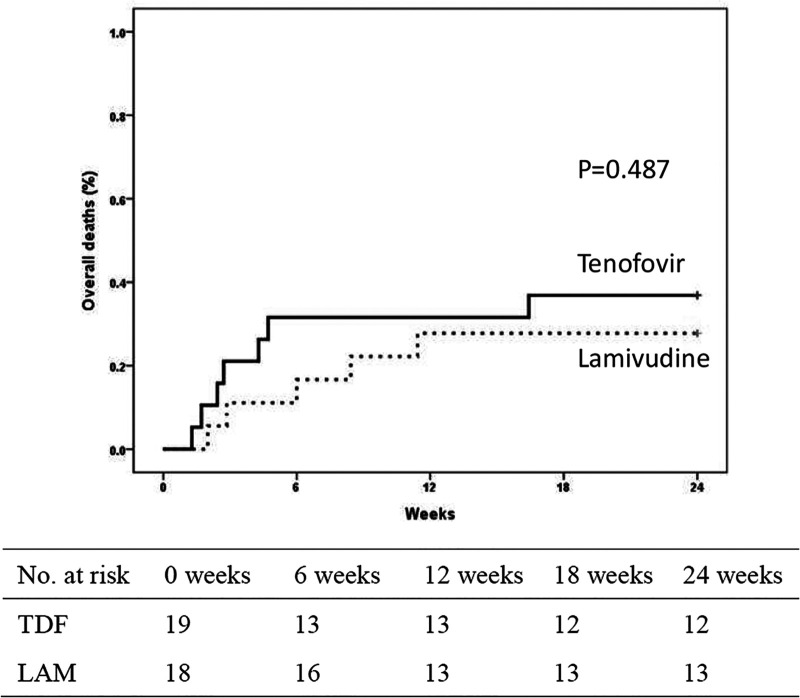

The short-term survival within 24 weeks was compared between the two groups, and 7 out of 19 (37%) patients in the TDF group and 5 out of 18 (28%) patients in the LAM-TDF group died or received liver transplantation within 24 weeks (Fig. 2). Three and 1 patient in the TDF and LAM-TDF groups, respectively, underwent liver transplantation. The observed difference in the mortality and liver transplantation rates between the TDF and LAM-TDF groups was not statistically significant (P = 0.487). The cause of all deaths in the TDF and LAM-TDF groups was liver failure.

FIG 2.

Cumulative rates of overall mortality or liver transplantation by week 24 in patients treated with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate and lamivudine.

Reduction of HBV DNA and overall mortality or liver transplantation.

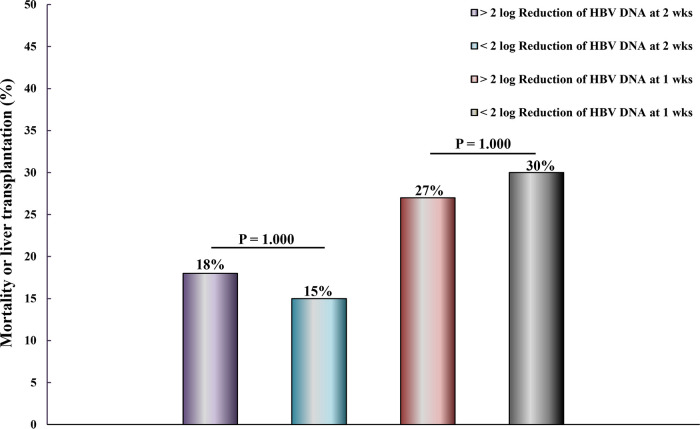

A reduction in HBV DNA of ≥2 log was observed 2 weeks after starting TDF or LAM in 17 of 30 patients. Mortality or liver transplantation within 24 weeks occurred in 3 out of 17 (18%) patients with a reduction of HBV DNA of ≥2 log and in 2 out of 13 (15%) patients with a reduction in HBV DNA of <2 log 2 weeks after starting TDF or LAM. The observed difference in the rates of mortality and liver transplantation between HBV DNA reduction of ≥2 log or <2 log at 2 weeks was not statistically significant (P = 1.000) (Fig. 3). A reduction in HBV DNA of ≥2 log was observed 1 week after starting TDF or LAM in 15 of 35 patients. Mortality or liver transplantation within 24 weeks occurred in 4 out of 15 (27%) patients with a reduction of HBV DNA of ≥2 log and in 6 out of 20 (30%) patients with a reduction in HBV DNA of <2 log 1 week after starting TDF or LAM. The observed difference in the rates of mortality and liver transplantation between HBV DNA reduction of ≥2 log or <2 log at 1 week was not statistically significant (P = 1.000) (Fig. 3).

FIG 3.

Two-log reduction in HBV DNA levels at 1 and 2 weeks and mortality or liver transplantation in TDF or lamivudine/TDF group.

Eight out of 14 (57%) and 9 out of 16 (56%) patients in the TDF and LAM-TDF groups, respectively, achieved a reduction of HBV DNA of ≥2 log 2 weeks after starting treatment (P = 1.000). Seven out of 17 (41%) and 8 out of 18 (44%) patients in the TDF and LAM-TDF groups, respectively, achieved a reduction of HBV DNA of ≥2 log 1 week after starting treatment (P = 1.000). TDF and LAM-TDF showed similar rates of HBV DNA reduction of ≥2 log 1 or 2 weeks after patients started treatment.

Factors associated with overall mortality or liver transplantation by week 24.

Baseline clinical and laboratory variables were analyzed as possible independent predictors of mortality or need for liver transplantation. The univariate analysis showed that age, albumin level, MELD score, and hepatic encephalopathy at presentation were significantly associated with mortality (Table 2). Multivariate analysis using the Cox proportional hazard model revealed that PT (hazard ratio [HR], 3.194; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.120 to 9.108; P = 0.030), albumin level (HR, 0.156; 95% CI, 0.025 to 0.966; P = 0.046), and hepatic encephalopathy (HR, 33.408; 95% CI, 0.046 to 221.19; P ≤ 0.001) were independently associated with mortality or liver transplantation within 24 weeks. Univariate and multivariate analyses showed that TDF or LAM followed by TDF had similar outcomes at 24 weeks in CHB patients with SAE.

TABLE 2.

Univariate and multivariate analyses of factors associated with mortality or liver transplantation by week 24 of treatmenta

| Parameter | Hazard ratio | 95% CI | P value (β) | Hazard ratio | 95% CI | P value (β) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 1.056 | 1.013–1.101 | 0.011 (0.27) | |||

| Sex (male vs female) | 0.749 | 0.238–2.3637 | 0.622 (0.93) | |||

| Cirrhosis (yes vs no) | 1.352 | 0.366–5.002 | 0.651 (0.94) | |||

| HBV DNA (log 10) | 1.194 | 0.878–1.622 | 0.258 (0.77) | |||

| HBeAg (positive vs negative) | 7.160 | 0.923–55.557 | 0.060 (0.08) | |||

| AFP (ng/ml) | 1.000 | 0.996–1.003 | 0.802 (0.93) | |||

| AST (U/liter) | 1.000 | 0.998–1.001 | 0.556 (0.91) | |||

| ALT (U/liter) | 0.999 | 0.998–1.000 | 0.238 (0.68) | |||

| Prothrombin time (INR) | 4.812 | 2.199–10.534 | <0.001 (0.32) | 3.194 | 1.120–9.108 | 0.030 (0.70) |

| Platelet (cells × 109/ml) | 0.995 | 0.987–1.004 | 0.281 (0.59) | |||

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.537 | 0.017–16.773 | 0.723 (0.94) | |||

| Albumin (g/dL) | 0.098 | 0.026–0.369 | 0.001 (0.04) | 0.156 | 0.025–0.966 | 0.046 (0.35) |

| Bilirubin (mg/dL) | 1.034 | 0.951–1.123 | 0.435 (0.89) | |||

| Albi grade (1 and 2 vs 3) | 0.329 | 0.099–1.093 | 0.070 (0.51) | |||

| MELD score | 1.211 | 1.043–1.406 | 0.012 (0.14) | |||

| Encephalopathy (yes vs no) | 24.289 | 3.927–150.220 | 0.001 (0.14) | 33.408 | 5.046–221.194 | <0.001 (0.09) |

| Ascites (yes vs no) | 1.714 | 0.375–7.845 | 0.487 (0.91) | |||

| Antiviral therapy (LAM-TDF vs TDF) | 0.667 | 0.212–2.104 | 0.490 (0.89) |

AST, aspartate transaminase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AFP, α-fetoprotein; MELD, model for end-stage liver disease; Albi, albumin-bilirubin. β, probability of type II error. Power = 1 − β.

Biochemical and virological response.

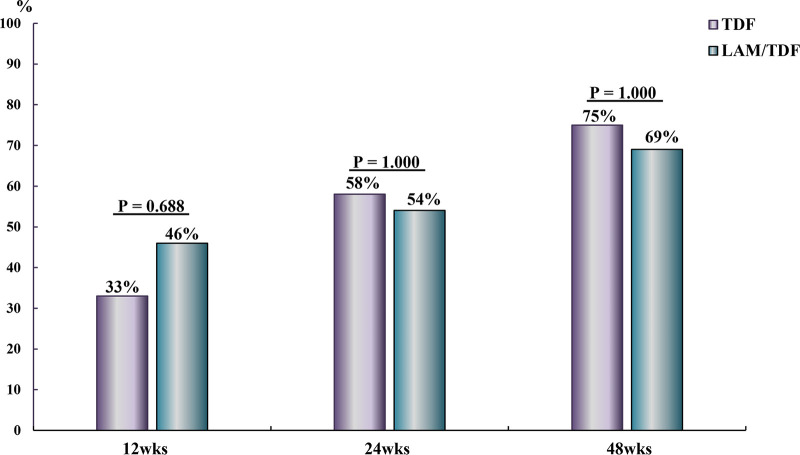

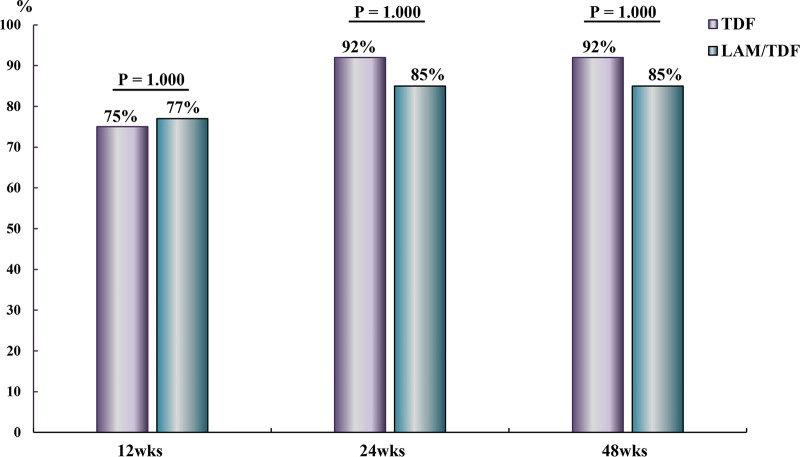

The virological responses at 12, 24, and 48 weeks were similar in the TDF and LAM-TDF groups (33% versus 46%, P = 0.688; 58% versus 54%, P = 1.000; and 75% versus 69% P = 1.000, respectively) (Fig. 4). The biochemical responses at 12, 24, and 48 weeks were also similar in the TDF and LAM-TDF groups (75% versus 77%, P = 1.000; 92% versus 85%, P = 1.000; and 92% versus 85%, P = 1.000, respectively) (Fig. 5).

FIG 4.

Virological responses at 12, 24, and 48 weeks in CHB patients with SAE who received TDF or lamivudine for 24 weeks followed by TDF.

FIG 5.

Biochemical responses at 12, 24, and 48 weeks in CHB patients with SAE who received TDF or lamivudine for 24 weeks followed by TDF.

DISCUSSION

TDF and LAM are effective anti-HBV agents that are well tolerated in patients with compensated or decompensated liver (27, 30). LAM is not a new drug for CHB, and some hepatologists appear to have forgotten its advantages, such as low price, quick onset of action, good efficacy, and no drug resistance within 24 weeks. A pharmacokinetic study of LAM in healthy Chinese participants showed that on days 1 and 7, the area under the concentration-time curve (AUC) at 0 and 24 h was 4,357 and 4,353 ng·ml−1h−1, respectively, and LAM achieved a similar AUC on days 1 and 7 (31). A pharmacokinetic study reported that the accumulation ratio of TDF was 1.51, and the maximum concentration in serum (Cmax) and AUC of TDF were significantly different between a single 300-mg dose and the corresponding multiple doses (32). Pharmacokinetic studies also showed that steady-state plasma concentrations of ETV were achieved 10 days after the first dose (33). Our recent study showed that in CHB patients with SAE with a high viral load, early LAM treatment before the bil level reached 15 mg/dL was associated with a better outcome than that of ETV (23). This finding suggested that LAM achieved a similar AUC after repeated dosing, but ETV took 10 days to show a stable AUC; thus, if administered early, LAM may show a better outcome than that of ETV. Garg et al. found that TDF reduced mortality more than the placebo did in CHB patients with SAE in a randomized study conducted in India (26). However, the efficacy of LAM versus TDF was not clear in CHB patients with SAE. In this randomized controlled study, we found that baseline characteristics were similar in both groups, and TDF and LAM for 2 weeks followed by TDF achieved similar outcomes at 24 weeks.

At 1 and 2 weeks, TDF and LAM-TDF resulted in similar degrees of HBV DNA reduction, and at 12 and 24 weeks, LAM-TDF resulted in virological and biochemical responses similar to those induced by TDF. After 24 weeks, LAM was replaced with TDF, and at 48 weeks, both groups achieved similar virological and biochemical responses, and no virological breakthrough happened in the LAM-TDF group. Our study showed that LAM administered for 24 weeks followed by TDF achieved clinical outcomes, including mortality or liver transplantation at 24 weeks and biochemical and virological responses at 24 and 48 weeks, similar to those achieved with TDF in CHB with SAE.

Mortality of CHB patients with SAE usually occurs within 24 weeks, so the administration of antiviral agents within 24 weeks is of prime importance (13, 14, 22, 28). In addition, viral resistance with LAM use within 24 weeks is extremely rare (10, 11). In clinical practice, LAM is much less expensive than TDF and, therefore, is recommended as the initial 24-week treatment option, especially in patients who have economic constraints. Although the benefits of combining more than one antiviral agent are under investigation, LAM may be a treatment option as a combinational nucleos(t)ide analog (NUC) for CHB with SAE because of its lower price, early achievement of plateau concentration (31), and equal efficacy compared with those of TDF within 24 weeks.

Garg et al. (26) found that a >2-log reduction in HBV DNA levels at 2 weeks was an independent predictor of survival in CHB patients with acute or chronic liver failure who received TDF or the placebo. However, in this study, patients who received TDF or the placebo were both included. In our study, all enrolled patients received NUCs (TDF or LAM followed by TDF), and we found that a reduction in HBV DNA of ≥2 log at 1 or 2 weeks was not associated with better outcomes at 24 weeks. We also found that LAM and TDF resulted in similar virological suppression of HBV DNA at 12 and 24 weeks. We enrolled patients who received TDF or LAM, but in these NUC-treated but not placebo-treated patients, the reduction in HBV DNA levels at 2 weeks was not an independent predictor of survival. The results of our study appeared different from those of the study by Garg et al. (26), because we enrolled only patients who received NUCs but not a placebo. Furthermore, in clinical practice, all CHB patients with SAE receive NUC treatment instead of a placebo, so our data represent real-world experience and significance.

Recent studies have identified several prognostic factors in CHB patients with SAE who received NUC treatment, including the presence of cirrhosis, ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, level of HBV DNA, bil or albumin level, PT, and high Child-Pugh Score (CTP) or MELD scores (7, 16, 22, 28). Our data indicated that albumin level, PT, and hepatic encephalopathy were independently associated with survival at 24 weeks and were consistent with previous studies. The independent factors associated with clinical outcomes in CHB patients with SAE who received TDF have seldom been discussed in large-scale studies, and there is a need to include more patients who received TDF to determine the prognostic factors in these patients.

In Taiwan, 24 weeks of TDF costs US$812 and 24 weeks of LAM costs US$296.80. TDF and LAM treatment for 24 weeks followed by TDF achieved a similar clinical outcome in CHB patients with SAE, but 24 weeks of LAM followed by TDF is more cost-effective.

The study is a randomized controlled study. Although some of the baseline characteristics seemed to be unfavorable in the TDF group, the presence of ascites and cirrhosis seemed to be unfavorable in the LAM group. There was no statistical significance in these characteristics between the two groups.

This is a prospective randomized study, but the sample size needed to prove the hypothesis was not calculated in advance. Although the sample size was small due to there being few patients, after power analysis, the power results of the parameters that were significant in the univariate analysis were acceptable (power = 1 − β; between 0.68 and 0.96) (Table 2). For the parameters that were not significant, the β value was between 0.51 and 0.94, except for HBeAg (β = 0.08), and implied that there was high probability of falsely getting insignificant results.

When multivariate analysis was performed, we included only five independent variables that were significant in the simple Cox regression analysis, and after backward logistic regression selection, only three variables were significant. There should be no overfitting problems. However, because sample size was small, there was still the problem of high probability of falsely getting insignificant results for age and MELD score.

This study has some limitations that are worth mentioning. For instance, although this was a randomized controlled study, the number of cases included was small. The rate of mortality or receipt of liver transplantation appeared to be similar in the TDF group and the LAM-TDF group in this study. However, further randomized controlled studies enrolling more patients may be required to determine whether TDF or LAM treatment produces a better treatment outcome in 24 weeks and to investigate the prognostic factors associated with NUC use in CHB patients with SAE. In addition, LAM may be incorporated into the combination therapy regimen for CHB with SAE within 24 weeks, and future studies that investigate the efficacy of the combination therapy are encouraged. Resistance-associated mutations were not investigated in this study. HBV genotypic resistance due to LAM or TDF seldom occurred within 24 weeks (17, 18, 25), so the resistance-associated mutations were not checked.

Conclusions.

Treatment with TDF or LAM followed by TDF achieved similar clinical outcomes in CHB patients with SAE. LAM is a potential treatment option for use either as a single agent or part of a combination therapy with other NUCs for CHB patients with SAE within 24 weeks.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients.

Consecutive patients who presented with CHB with SAE agreed to participate in the study and signed the informed consents from July 2013 to December 2017 were randomized to receive 300 mg TDF daily (q.d.) or 100 mg LAM q.d. for 24 weeks, followed by 300 mg TDF q.d., in Kaohsiung Veterans General Hospital. Randomization was done with a random number table. All patients had a history of HBV infection for ≥6 months. SAE was defined as an increase in alanine aminotransferase (ALT) to >5× the upper limit of normal (ULN), accompanied by a total bilirubin (bil) level of ≥2.0 mg/dL or prolongation of the prothrombin time (PT) by ≥3 s.

Patients who had used alcohol at >30 g/day, who took hepatotoxic agents, or had a history of hepatocellular carcinoma were excluded. Patients who had received antiviral treatment before, including interferon or nucleos(t)ide analogs (NUCs), were also excluded. Liver cirrhosis was diagnosed based on histological or characteristic ultrasonography findings (34).

Assessment.

Liver biochemistry studies, including complete blood counts, serum albumin, bil, aspartate aminotransferase (AST), ALT, creatinine, PT, HBeAg, anti-HBeAb, and HBV DNA, were determined following admission to the hospital. HBV DNA was subsequently determined 1 and 2 weeks after the start of TDF or LAM. The liver biochemistry data, PT, and renal function were monitored twice weekly until the patients’ conditions stabilized. Liver biochemistry, PT, and renal function were monitored every 3 months, and HBV DNA was monitored every 6 months.

All biochemical tests were performed in the Clinical Pathology Laboratories of Kaohsiung Veterans General Hospital using routine automated techniques. The serological markers HBsAg, HBeAg, IgM anti-HBc, and IgM anti-HAV were assayed using an immunoenzymatic assay (Abbott Laboratories, Ltd., Germany). Anti-HCV was assayed using an enzyme immunoassay (EIA) kit (Abbott Laboratories, Ltd., Germany). HBV DNA was quantified using real-time PCR, as previously described (35).

Statistical analysis.

Data are expressed as means ± standard deviations (SD). Categorical variables were analyzed using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate, and continuous variables were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney test. The cumulative incidences of mortality or liver transplantation were analyzed using the Kaplan-Meier method with a log rank test. Univariate and multivariate analyses using the Cox proportional hazard regression models were performed to identify independent factors associated with mortality of CHB patients with SAE. All statistical tests were two-tailed, and a P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethics.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Kaohsiung Veterans General Hospital (VGHKS12-CT5-10), and all patients provided written informed consent before enrollment.

Data availability.

The data sets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

C.M.L. conducted the study and wrote the manuscript. W.L.T. designed research topics, conducted the study, analyzed data, and wrote and revised the manuscript. J.S.C. and W.C.S. performed data analysis and data coordination. W.C.C., F.W.T., H.M.W., T.J.T., S.S.K., Y.D.L., and Y.R.L. contributed data. H.S.L. performed statistical analysis.

This study was sponsored by Gilead Sciences (IN-US-174-0190). The investigator designed the study and collected, analyzed, and interpreted the data. W.L.T. is a speaker for Gilead. Other authors declared no conflicts of interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lee WM. 1997. Hepatitis B virus infection. N Engl J Med 337:1733–1745. 10.1056/NEJM199712113372406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seto WK, Lo YR, Pawlotsky JM, Yuen MF. 2018. Chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Lancet 392:2313–2324. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31865-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tang LSY, Covert E, Wilson E, Kottilil S. 2018. Chronic hepatitis B infection: a review. JAMA 319:1802–1813. 10.1001/jama.2018.3795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lok AS, Lai CL. 1990. Acute exacerbations in Chinese patients with chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection. Incidence, predisposing factors and etiology. J Hepatol 10:29–34. 10.1016/0168-8278(90)90069-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liaw YF. 1995. Acute exacerbation and superinfection in patients with chronic viral hepatitis. J Formos Med Assoc 94:521–528. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Perrillo RP. 2001. Acute flares in chronic hepatitis B: the natural and unnatural history of an immunologically mediated liver disease. Gastroenterology 120:1009–1022. 10.1053/gast.2001.22461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tsai WL, Sun WC, Cheng JS. 2015. Chronic hepatitis B with spontaneous severe acute exacerbation. Int J Mol Sci 16:28126–28145. 10.3390/ijms161226087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sheen IS, Liaw YF, Tai DI, Chu CM. 1985. Hepatic decompensation associated with hepatitis B e antigen clearance in chronic type B hepatitis. Gastroenterology 89:732–735. 10.1016/0016-5085(85)90566-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davis GL, Hoofnagle JH. 1985. Reactivation of chronic type B hepatitis presenting as acute viral hepatitis. Ann Intern Med 102:762–765. 10.7326/0003-4819-102-6-762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lai C-L, Chien R-N, Leung NWY, Chang T-T, Guan R, Tai D-I, Ng K-Y, Wu P-C, Dent JC, Barber J, Stephenson SL, Gray DF. 1998. A one-year trial of lamivudine for chronic hepatitis B. Asia Hepatitis Lamivudine Study Group. N Engl J Med 339:61–68. 10.1056/NEJM199807093390201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Villeneuve J-P, Condreay LD, Willems B, Pomier-Layrargues G, Fenyves D, Bilodeau M, Leduc R, Peltekian K, Wong F, Margulies M, Heathcote EJ. 2000. Lamivudine treatment for decompensated cirrhosis resulting from chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology 31:207–210. 10.1002/hep.510310130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yao FY, Bass NM. 2000. Lamivudine treatment in patients with severely decompensated cirrhosis due to replicating hepatitis B infection. J Hepatol 33:301–307. 10.1016/S0168-8278(00)80371-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chan HL, Tsang SW, Hui Y, Leung NW, Chan FK, Sung JJ. 2002. The role of lamivudine and predictors of mortality in severe flare-up of chronic hepatitis B with jaundice. J Viral Hepat 9:424–428. 10.1046/j.1365-2893.2002.00385.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsubota A, Arase Y, Suzuki Y, Suzuki F, Sezaki H, Hosaka T, Akuta N, Someya T, Kobayashi M, Saitoh S, Ikeda K, Kumada H. 2005. Lamivudine monotherapy for spontaneous severe acute exacerbation of chronic hepatitis B. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 20:426–432. 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2004.03534.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chien RN, Lin CH, Liaw YF. 2003. The effect of lamivudine therapy in hepatic decompensation during acute exacerbation of chronic hepatitis B. J Hepatol 38:322–327. 10.1016/S0168-8278(02)00419-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sun LJ, Yu JW, Zhao YH, Kang P, Li SC. 2010. Influential factors of prognosis in lamivudine treatment for patients with acute-on-chronic hepatitis B liver failure. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 25:583–590. 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.06089.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yuen MF, Sablon E, Hui CK, Yuan HJ, Decraemer H, Lai CL. 2001. Factors associated with hepatitis B virus DNA breakthrough in patients receiving prolonged lamivudine therapy. Hepatology 34:785–791. 10.1053/jhep.2001.27563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liaw Y-F, Leung NWY, Chang T-T, Guan R, Tai D-I, Ng K-Y, Chien R-N, Dent J, Roman L, Edmundson S, Lai C-L. 2000. Effects of extended lamivudine therapy in Asian patients with chronic hepatitis B. Asia Hepatitis Lamivudine Study Group. Gastroenterology 119:172–180. 10.1053/gast.2000.8559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dienstag JL, Schiff ER, Wright TL, Perrillo RP, Hann H-WL, Goodman Z, Crowther L, Condreay LD, Woessner M, Rubin M, Brown NA. 1999. Lamivudine as initial treatment for chronic hepatitis B in the United States. N Engl J Med 341:1256–1263. 10.1056/NEJM199910213411702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chang T-T, Gish RG, de Man R, Gadano A, Sollano J, Chao Y-C, Lok AS, Han K-H, Goodman Z, Zhu J, Cross A, DeHertogh D, Wilber R, Colonno R, Apelian D. 2006. A comparison of entecavir and lamivudine for HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med 354:1001–1010. 10.1056/NEJMoa051285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lai C-L, Shouval D, Lok AS, Chang T-T, Cheinquer H, Goodman Z, DeHertogh D, Wilber R, Zink RC, Cross A, Colonno R, Fernandes L. 2006. Entecavir versus lamivudine for patients with HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med 354:1011–1020. 10.1056/NEJMoa051287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wong VW-S, Wong GL-H, Yiu KK-L, Chim AM-L, Chu SH-T, Chan H-Y, Sung JJ-Y, Chan HL-Y. 2011. Entecavir treatment in patients with severe acute exacerbation of chronic hepatitis B. J Hepatol 54:236–242. 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.06.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tsai W-L, Chiang P-H, Chan H-H, Lin H-S, Lai K-H, Cheng J-S, Chen W-C, Tsay F-W, Wang H-M, Tsai T-J, Yu H-C, Hsu P-I. 2014. Early entecavir treatment for chronic hepatitis B with severe acute exacerbation. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:1918–1921. 10.1128/AAC.02400-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marcellin P, Heathcote EJ, Buti M, Gane E, de Man RA, Krastev Z, Germanidis G, Lee SS, Flisiak R, Kaita K, Manns M, Kotzev I, Tchernev K, Buggisch P, Weilert F, Kurdas OO, Shiffman ML, Trinh H, Washington MK, Sorbel J, Anderson J, Snow-Lampart A, Mondou E, Quinn J, Rousseau F. 2008. Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate versus adefovir dipivoxil for chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med 359:2442–2455. 10.1056/NEJMoa0802878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heathcote EJ, Marcellin P, Buti M, Gane E, De Man RA, Krastev Z, Germanidis G, Lee SS, Flisiak R, Kaita K, Manns M, Kotzev I, Tchernev K, Buggisch P, Weilert F, Kurdas OO, Shiffman ML, Trinh H, Gurel S, Snow-Lampart A, Borroto-Esoda K, Mondou E, Anderson J, Sorbel J, Rousseau F. 2011. Three-year efficacy and safety of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate treatment for chronic hepatitis B. Gastroenterology 140:132–143. 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garg H, Sarin SK, Kumar M, Garg V, Sharma BC, Kumar A. 2011. Tenofovir improves the outcome in patients with spontaneous reactivation of hepatitis B presenting as acute-on-chronic liver failure. Hepatology 53:774–780. 10.1002/hep.24109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liaw Y-F, Sheen I-S, Lee C-M, Akarca US, Papatheodoridis GV, Suet-Hing Wong F, Chang T-T, Horban A, Wang C, Kwan P, Buti M, Prieto M, Berg T, Kitrinos K, Peschell K, Mondou E, Frederick D, Rousseau F, Schiff ER. 2011. Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF), emtricitabine/TDF, and entecavir in patients with decompensated chronic hepatitis B liver disease. Hepatology 53:62–72. 10.1002/hep.23952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hung C-H, Hu T-H, Lu S-N, Lee C-M, Chen C-H, Kee K-M, Wang J-H, Tsai M-C, Kuo Y-H, Chang K-C, Chiu Y-C, Chen C-H. 2015. Tenofovir versus entecavir in treatment of chronic hepatitis B virus with severe acute exacerbation. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:3168–3173. 10.1128/AAC.00261-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Park JG, Lee YR, Park SY, Lee HJ, Tak WY, Kweon YO, Jang SY, Chun JM, Han YS, Hur K, Lee HW, Kang MK. 2018. Tenofovir, entecavir, and lamivudine in patients with severe acute exacerbation and hepatic decompensation of chronic hepatitis B. Dig Liver Dis 50:163–167. 10.1016/j.dld.2017.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liaw Y-F, Sung JJY, Chow WC, Farrell G, Lee C-Z, Yuen H, Tanwandee T, Tao Q-M, Shue K, Keene ON, Dixon JS, Gray DF, Sabbat J. 2004. Lamivudine for patients with chronic hepatitis B and advanced liver disease. N Engl J Med 351:1521–1531. 10.1056/NEJMoa033364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jiang J, Hu P, Xie H, Chen H, Fan F, Harker A, Johnson MA. 1999. The pharmacokinetics of lamivudine in healthy Chinese subjects. Br J Clin Pharmacol 48:250–253. 10.1046/j.1365-2125.1999.00984.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lu C, Jia Y, Chen L, Ding Y, Yang J, Chen M, Song Y, Sun X, Wen A. 2013. Pharmacokinetics and food interaction of a novel prodrug of tenofovir, tenofovir dipivoxil fumarate, in healthy volunteers. J Clin Pharm Ther 38:136–140. 10.1111/jcpt.12023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yan J-H, Bifano M, Olsen S, Smith RA, Zhang D, Grasela DM, LaCreta F. 2006. Entecavir pharmacokinetics, safety, and tolerability after multiple ascending doses in healthy subjects. J Clin Pharmacol 46:1250–1258. 10.1177/0091270006293304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lin DY, Sheen IS, Chiu CT, Lin SM, Kuo YC, Liaw YF. 1993. Ultrasonographic changes of early liver cirrhosis in chronic hepatitis B: a longitudinal study. J Clin Ultrasound 21:303–308. 10.1002/jcu.1870210502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cane PA, Cook P, Ratcliffe D, Mutimer D, Pillay D. 1999. Use of real-time PCR and fluorimetry to detect lamivudine resistance-associated mutations in hepatitis B virus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 43:1600–1608. 10.1128/AAC.43.7.1600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data sets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.