Abstract

Background

Heat and cold are commonly utilised in the treatment of low‐back pain by both health care professionals and people with low‐back pain.

Objectives

To assess the effects of superficial heat and cold therapy for low‐back pain in adults.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Back Review Group Specialised register, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (The Cochrane Library Issue 3, 2005), MEDLINE (1966 to October 2005), EMBASE (1980 to October 2005) and other relevant databases.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials and non‐randomised controlled trials that examined superficial heat or cold therapies in people with low‐back pain.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently assessed methodological quality and extracted data, using the criteria recommended by the Cochrane Back Review Group.

Main results

Nine trials involving 1117 participants were included. In two trials of 258 participants with a mix of acute and sub‐acute low‐back pain, heat wrap therapy significantly reduced pain after five days (weighted mean difference (WMD) 1.06, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.68 to 1.45, scale range 0 to 5) compared to oral placebo. One trial of 90 participants with acute low‐back pain found that a heated blanket significantly decreased acute low‐back pain immediately after application (WMD ‐32.20, 95%CI ‐38.69 to ‐25.71, scale range 0 to 100). One trial of 100 participants with a mix of acute and sub‐acute low‐back pain examined the additional effects of adding exercise to heat wrap, and found that it reduced pain after seven days. There is insufficient evidence to evaluate the effects of cold for low‐back pain, and conflicting evidence for any differences between heat and cold for low‐back pain.

Authors' conclusions

The evidence base to support the common practice of superficial heat and cold for low back pain is limited and there is a need for future higher‐quality randomised controlled trials. There is moderate evidence in a small number of trials that heat wrap therapy provides a small short‐term reduction in pain and disability in a population with a mix of acute and sub‐acute low‐back pain, and that the addition of exercise further reduces pain and improves function. The evidence for the application of cold treatment to low‐back pain is even more limited, with only three poor quality studies located. No conclusions can be drawn about the use of cold for low‐back pain. There is conflicting evidence to determine the differences between heat and cold for low‐back pain.

Plain language summary

Superficial heat or cold for low back pain

There is moderate evidence that heat wrap therapy reduces pain and disability for patients with back pain that lasts for less than three months. The relief has only been shown to occur for a short time and the effect is relatively small. The addition of exercise to heat wrap therapy appears to provide additional benefit. There is still not enough evidence about the effect of the application of cold for low‐back pain of any duration, or for heat for back pain that lasts longer than three months.

Heat treatments include hot water bottles, soft heated packs filled with grain, poultices, hot towels, hot baths, saunas, steam, heat wraps, heat pads, electric heat pads and infra‐red heat lamps. Cold treatments include ice, cold towels, cold gel packs, ice packs and ice massage.

Background

Low‐back pain is a common complaint with the lifetime prevalence reported as ranging from 11% to 84% (Walker 2000). The cause of pain is non‐specific in about 95% of people presenting with acute low‐back pain, with serious conditions being rare (Hollingworth 2002). Chronic low‐back pain is a well documented disabling condition, costly to both individuals and society (Carey 1995; Frymoyer 1991; Maniadakis 2000).

Different health care disciplines commonly use heat and cold treatments for the treatment of low‐back pain (Battie 1994; Car 2003; Geffen 2003; Hamm 2003; Jette 1996; Li 2001; Rush 1994; Stanos 2004). Both therapies are simple to apply and are inexpensive. They may be used by people with low‐back pain at home, or may be employed by practitioners as part of a treatment regimen.

Traditionally, ice has been recommended for acute injury and heat has been recommended for longer term injuries (Grana 1993; Michlovitz 1996). Superficial heat modalities convey heat by conduction or convection. Superficial heat elevates the temperature of tissues and provides the greatest effect at 0.5 cm or less from the surface of the skin. However, deep heating is achieved by converting another form of energy to heat, for example, shortwave diathermy, microwave diathermy and ultrasound (Vasudevan 1997). Superficial heat includes such modalities as hot water bottles, heated stones, soft heated packs filled with grain, poultices, hot towels, hot baths, saunas, steam, heat wraps, heat pads, electric heat pads and infra‐red heat lamps. Cold therapy is used to reduce inflammation, pain and oedema. Superficial cold includes cryotherapy, ice, cold towels, cold gel packs, ice packs and ice massage.

Various national guidelines for the management of low‐back pain have conflicting recommendation for heat and cold therapy. The US Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality guidelines found no evidence of benefit from the application of ice or heat for acute low‐back pain, however recommended self‐application of heat or cold for patients to provide temporary relief of symptoms (Bigos 1994). Other guidelines give different recommendations (ACC 1997; ICSI 2004; AAMPGG 2003; Europe 2004).

Objectives

The objective of this review was to determine the efficacy of superficial hot or cold therapies in reducing pain and disability in low‐back pain in adults, aged 18 and older.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and non‐randomised controlled clinical trials (CCTs) comparing superficial hot or cold therapy to placebo, no therapy or to other therapies.

Types of participants

Studies were selected that included participants aged 18 years or over, with the complaint of non‐specific low‐back pain. Trials that included participants with pathological causes of low‐back pain and low‐back pain with radiculopathy were excluded. For the purpose of this review, the duration of back pain was defined as acute (less than six weeks), sub‐acute (six weeks to 12 weeks) or chronic (longer than 12 weeks), as defined by the Cochrane Back Review Group (van Tulder 2003).

Types of interventions

Trials were included in which superficial heat or cold therapy was administered to at least one group within the trial. Trials in which co‐interventions (eg. exercise) were given were only included if the co‐interventions were similar across comparison groups. If co‐interventions were given, trials were excluded if we could not isolate the effects of heat or cold from the effects of the other therapies delivered. Trials of spa therapy (balneotherapy) were excluded because that intervention is being assessed by another Cochrane review. At the time of publication of our review, the protocol for the balneotherapy review had only proceeded to the editorial review stage.

Types of outcome measures

Trials were included that used at least one of the five outcomes considered to be important in low‐back pain research: pain (eg. measured by visual analogue scale (VAS)), disability/function (eg. measured by Oswestry, Roland Disability Scale), overall improvement, patient satisfaction and adverse effects. The primary outcomes for this review were pain and physical functional status. Some included trials measured other outcomes, eg. trunk flexibility or skin temperature, however, these results are not included in the analysis because they are out of the scope of this review.

Search methods for identification of studies

Data Sources

The following sources were accessed and searched:

1. The Cochrane Controlled Trials Register (Central) (The Cochrane Library Issue 3, 2005)

2. MEDLINE (1966 to October 2005)

3. EMBASE (1980 to October 2005)

4. CINAHL (1982 to October 2005)

5. PEDro (Physiotherapy Evidence Database ‐ www.pedro.fhs.usyd.edu.au, accessed October 2005)

6. Back Review Group Specialised register (May 2005)

7. SPORTDiscus (1830 to October 2005)

8. OLDMEDLINE (1950 to 1965, searched October 2005)

Search strategy

The search strategy was based on that recommended by the Cochrane Back Review Group (van Tulder 2003).

The search strategies for MEDLINE, EMBASE and CENTRAL are included as appendices (Appendix 1; Appendix 2; Appendix 3). Search strategies for the remaining databases were adapted accordingly. We also screened references of identified articles.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

One author (SF) conducted the searches and compiled all of the abstracts retrieved by the above search strategy. Two authors (SF and BW) then independently applied the inclusion criteria to all of these abstracts. If the eligibility of the study was not clear from the abstract, then the full text of the article was obtained and assessed independently by the two authors. Any disagreement between the authors was resolved by discussion and consensus. For excluded studies that required retrieval of the full text for a decision of their eligibility, details of the reasons for exclusion are given in the Table of Excluded Studies.

Data extraction and management

Two authors (SF and MC) independently extracted the data onto a standard form. The data extraction form was pilot tested on one trial to minimise misinterpretation. Any disagreement between the authors was resolved by discussion and consensus. We requested additional study details and data from trial authors when the data reported were incomplete. Some data from the Nadler studies (Nadler 2002; Nadler 2003a; Nadler 2003b) and from the Mayer study (Mayer 2005) were received from the authors and were incorporated into the Table of Included Studies and the results.

Assessment of methodological quality of included studies

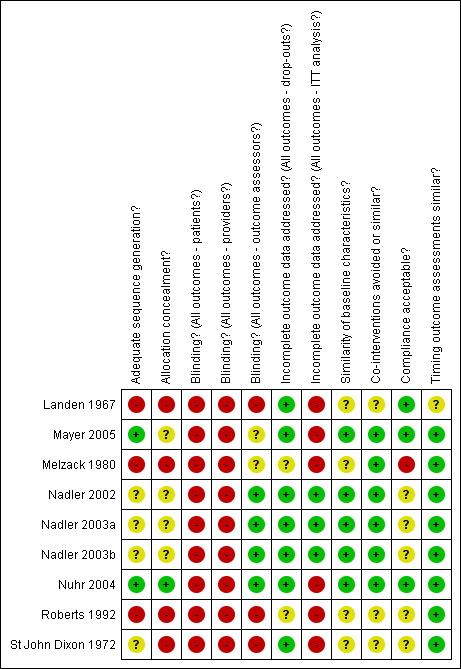

The methodologic quality of the included trials was independently assessed by two authors (SF and MC) and checked by a third author (JR). The assessment of methodologic quality was performed according to the methodologic criteria list recommended by the Cochrane Back Review Group (Table 1), and scored as a "yes (+)", "no (‐)" or "don't know (?)" (Figure 1). There were 11 criteria relevant to the internal validity of the study, against which each trial was assessed, including selection bias, performance bias, attrition bias and detection bias. The methodological quality assessment of the trials was used to grade the strength of the evidence. Higher quality trials were defined as fulfilling six or more of the 11 methodological quality criteria. Lower quality trials were defined as fulfilling fewer than six criteria.

1. Criteria for the Risk of Bias Assessment.

| Criteria | Criteria for a judgment of yes for the sources of risk of bias |

| Was the method of randomisation adequate? | A random (unpredictable) assignment sequence. Examples of adequate methods are computer generated random number table and use of sealed opaque envelopes. Methods of allocation using date of birth, date of admission, hospital numbers, or alternation would not be regarded as appropriate. |

| Was the treatment allocation concealed? | Assignment generated by an independent person not responsible for determining the eligibility of the participants. This person has no information about the persons included in the trial and has no influence on the assignment sequence or on the decision about eligibility of the participant. |

| Was the patient blinded to the intervention? | The review author determined when enough information about the blinding is given in order to score a 'yes'. |

| Was the care provider blinded to the intervention? | The review author determined when enough information about the blinding is given in order to score a 'yes'. |

| Was the outcome assessor blinded to the intervention? | The review author determined (per outcome parameter) when enough information about blinding is given in order to score a 'yes'. |

| Was the drop‐out rate described and acceptable? | The number of participants who were included in the study but did not complete the observation period or were not included in the analysis must be described and reasons given. If the percentage of withdrawals and drop‐outs does not exceed 20% for immediate and short‐term follow‐ups, 30% for intermediate and long‐term follow‐ups and does not lead to substantial bias a "yes" was scored. |

| Did the analysis include an intention‐to‐treat analysis? | All allocated participants are reported/analysed for the most important moments of effect measurement (minus missing values) irrespective of non compliance and co‐interventions. |

| Were the groups similar at baseline regarding the most important prognostic indicators? | To receive a "yes," groups must be similar at baseline regarding age, duration of complaints, percentage of patients with radiating pain, and value of main outcome measure(s). |

| Were co‐interventions avoided or similar? | Cointerventions should either be avoided in the trial design or similar between the index and control groups. |

| Was the compliance acceptable in all groups? | The review author determined when the compliance to the interventions is acceptable, based on the reported intensity, duration, number, and frequency of sessions for both the index intervention and control intervention(s). |

| Was the timing of the outcome assessment in all groups similar? | Timing of outcome assessment should be identical for all intervention groups and for all important outcome assessments. |

1.

Summary of risks of bias

Data analysis

Only a small proportion of the data in the included trials were available for pooling. For the majority of comparisons and outcomes it was not possible to pool results.

A qualitative method recommended by the Cochrane Back Review Group (van Tulder 2003), using Levels of Evidence for data synthesis was performed:

Strong evidence*: consistent findings among multiple high quality RCTs

Moderate evidence: consistent findings among multiple low quality RCTs or controlled clinical trials (CCTs) and/or one high quality RCT

Limited evidence: one low quality RCT and/or CCT

Conflicting evidence: inconsistent findings among multiple trials (RCTs and/or CCTs)

No evidence from trials: no RCTs or CCTs

*There is consensus among the Editorial Board of the Back Review Group that strong evidence can only be provided by multiple higher quality trials that replicate findings of other researchers in other settings.

Clinical relevance

Two authors (SF and JR) independently judged the clinical relevance of each trial, using the five questions recommended by the Cochrane Back Review Group, and scored each one as a "yes (+)", "no (‐)" or "don't know (?)":

1. Are the patients described in detail so that you can decide whether they are comparable to those that you see in your practice? 2. Are the interventions and treatment settings described well enough so that you can provide the same for your patients? 3. Were all clinically relevant outcomes measured and reported? 4. Is the size of the effect clinically important? 5. Are the likely treatment benefits worth the potential harms?

Results

Description of studies

The search strategy identified 1178 potentially eligible studies. Of these, 123 were retrieved in full text. We identified nine trials involving 1117 participants suitable for inclusion. All nine trials were published in English.

Included studies

See the table of 'Characteristics of Included Studies' for full details. The median number of participants in each trial was 90 (range 36 to 371). One of the trials included acute low‐back pain participants (Nuhr 2004), four included a mix of acute and sub‐acute low‐back pain participants (Mayer 2005; Nadler 2002; Nadler 2003a; Nadler 2003b), three included chronic low‐back pain participants (Melzack 1980; Roberts 1992; St John Dixon 1972) and one had a mix of acute, sub‐acute and chronic participants (Landen 1967).

The nature of the interventions differed between the trials. Two trials compared hot packs to ice massage (Landen 1967, Roberts 1992), one trial compared ice massage to transcutaneous electrical stimulation (Melzack 1980), one trial compared a full body active warming electric blanket to passive warming by way of a woollen blanket (Nuhr 2004) and one trial compared a wool body belt that provided warmth to a lumbar corset (St John Dixon 1972).

Four trials assessed the effect of a heated lumbar wrap compared to various interventions. Three of these trials compared the heated wrap to pain relief medication and to a non‐heated wrap (Nadler 2002; Nadler 2003a; Nadler 2003b) and one trial compared the heated wrap alone to exercise alone, to heat plus exercise and to an educational booklet (Mayer 2005). The heat wrap is a disposable product made of layers of cloth‐like material that contain heat‐generating ingredients (iron, charcoal, table salt and water). These ingredients heat up when exposed to oxygen and provide heat (40 degrees C) for at least eight hours. The heat wrap is applied to the lumbar region of the torso and is secured with a velcro‐like closure, thus allowing it to be worn while remaining mobile. It can be worn during the day or night. The single use heat wrap costs approximately US$6.00 to $8.00 for a packet of two.

The outcomes assessed and the timing of outcomes varied. Pain was assessed in all trials, however for only five trials were pain data available for meta‐analysis. Three trials only measured pain immediately after the treatment (Melzack 1980; Nuhr 2004; Roberts 1992), four trials measured pain over four to seven days (Mayer 2005; Nadler 2002; Nadler 2003a; Nadler 2003b), one trial measured pain at the time of hospital discharge (Landen 1967) and one after two weeks (St John Dixon 1972). A validated disability measure was used in four trials (Mayer 2005; Nadler 2002; Nadler 2003a; Nadler 2003b). None of the trials assessed overall improvement or participant satisfaction.

Four of the trials declared industry funding (Mayer 2005; Nadler 2002; Nadler 2003a; Nadler 2003b). The three Nadler trials were all conducted by the same research team and were funded by the manufacturer of the heat wrap device. The authors of each of these trials were either employees or paid consultants of the company that manufactures the heat wrap device. Correspondence from the authors indicated that these three trials are completely separate studies with each of them including different participants.

Excluded studies

See the table of 'Characteristics of Excluded Studies' for details.

Risk of bias in included studies

The included trials were of varying methodological quality (see Figure 1). Applying the criteria of six or more equalling a high quality study, five of the trials were of high quality (range 6 to 8) and four low quality (range 1 to 5). Five of the trials were reported as randomised (Mayer 2005; Nadler 2002; Nadler 2003a; Nadler 2003b; Nuhr 2004). In the Nadler series of trials, the method of randomisation was not described. One trial was a non‐randomised CCT (Landen 1967) and three were non‐randomised cross‐over trials (Melzack 1980; Roberts 1992; St John Dixon 1972). Washout of the interventions was not considered in any of the cross‐over trials. Trial population sizes were generally small (median sample size = 90, range 36 to 371). Five of the trials reported clear inclusion and exclusion criteria (Mayer 2005; Nadler 2002; Nadler 2003a; Nadler 2003b; Nuhr 2004), two trials reported brief inclusion and exclusion criteria (Landen 1967; Melzack 1980) and two trials did not state exclusion criteria (Roberts 1992; St John Dixon 1972). Allocation concealment was adequate in only one of the trials (Nuhr 2004), and in the remaining trials was either not reported or was inadequate. Blinded outcome assessment was carried out in four trials (Nadler 2002; Nadler 2003a; Nadler 2003b; Nuhr 2004) and was either not done or was unclear in the remaining five trials. Blinding of participants to the interventions of heat or cold was not possible in most cases. Most trials had an acceptable loss to follow‐up, however, only three of the trials reported if an intention‐to‐treat analysis was undertaken (Nadler 2002; Nadler 2003a; Nadler 2003b).

Effects of interventions

Nine trials involving 1117 participants were included in this review. Only four of these trials had pain data in a form that could be extracted and combined in a meta‐analysis (Mayer 2005; Nadler 2002; Nadler 2003a; Nadler 2003b), and this was only possible after obtaining further data from the authors of the studies. All of these trials examined a heat wrap as the main intervention. One trial had pain data that could be extracted (Nuhr 2004), however it was absolute pain data as compared to change in pain data used in the other heat wrap trials. The remaining four trials did not present data in a form that could be extracted for meta‐analysis (Landen 1967; Melzack 1980; Roberts 1992; St John Dixon 1972). Despite attempts to contact all authors, only additional data for the three Nadler trials and the Mayer trial were obtained.

Comparison 01: Heated wrap versus oral placebo or non‐heated wrap

Four higher quality trials assessed a heated wrap or heated blanket versus either an oral placebo tablet, or a non‐heated wrap (Nadler 2002; Nadler 2003a; Nadler 2003b; Nuhr 2004) in participants with a mix of acute and sub‐acute (less than three months) low‐back pain. It was only possible to combine the data from a maximum of two trials.

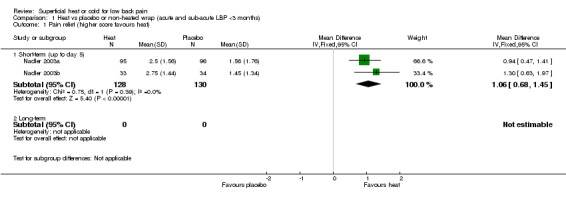

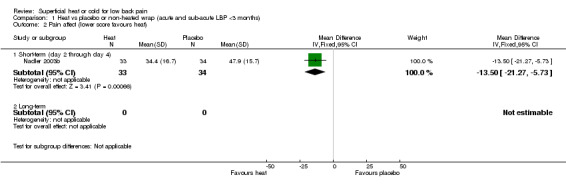

Pain relief data were extracted from two of the trials with 258 participants that compared a heated wrap to oral placebo (Nadler 2003a; Nadler 2003b). The short‐term pain relief was significantly greater for the heated back wrap than for the oral placebo (weighted mean difference (WMD) 1.06, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.68 to 1.45 scale range zero to five). Pain relief was only measured for up to five days after randomisation. This result indicates an approximate 17% reduction in pain after five days with a heated back wrap compared to oral placebo. Pain data measuring the degree of "unpleasantness" were only available for one trial (Nadler 2003b) and indicated a significant decrease in the short‐term (WMD ‐13.50, 95%CI ‐21.27 to ‐5.73, scale range zero to 100).

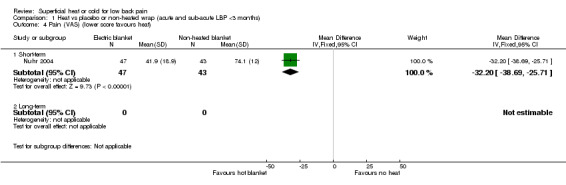

Absolute pain data were only available in one trial of 90 participants (Nuhr 2004). This trial demonstrated a statistically significant benefit of a heated blanket compared to a non‐heated blanket immediately after treatment in acute (less than six hours) low‐back pain (WMD ‐32.20, 95%CI ‐38.69 to ‐25.71, scale range zero to 100). Pain was only measured immediately after the heat was applied for approximately 25 minutes, and no further follow‐up occurred.

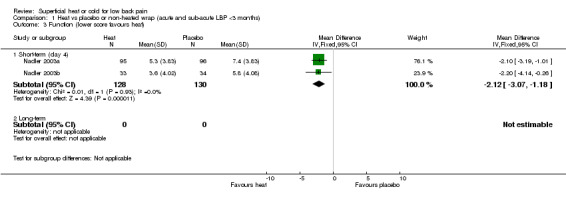

Only two trials provided data on disability (Nadler 2003a; Nadler 2003b), measured with the Roland‐Morris Disability Questionnaire. The short‐term (four days) reduction in disability was significantly greater for the heated back wrap than for oral placebo (WMD ‐2.10, 95%CI ‐3.19 to ‐1.01, scale range zero to 24).

Adverse effects were minor for the heated back wrap. Two trials provided data on the adverse effect of "skin pinkness" after use of the heated wrap (Nadler 2003a; Nadler 2003b). A total of six out of 128 participants experienced this outcome in the heated back wrap group, compared to one participant out of 130 in the placebo group.

No trials were located that examined this comparison for chronic low‐back pain or for the medium or long‐term effects of this intervention.

Comparison 02: Cold versus placebo or no cold

No studies were located that examined this comparison.

Comparison 03: Heat versus cold

Two lower quality trials evaluated heat versus cold in the form of hot packs versus ice massage (Landen 1967; Roberts 1992). Unfortunately there were very little data available in either of these trials to extract. Both of these trials were non‐randomised, one a controlled trial (Landen 1967) and the other a cross‐over trial (Roberts 1992). One trial concluded that hot packs and ice massage were not significantly different for participants with a mix of acute, sub‐acute and chronic low‐back pain. The other concluded that ice massage was superior to hot packs in participants with chronic low‐back pain.

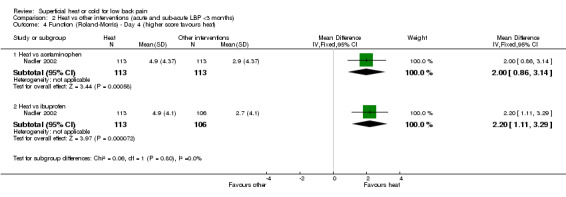

Comparison 04: Heat versus other interventions

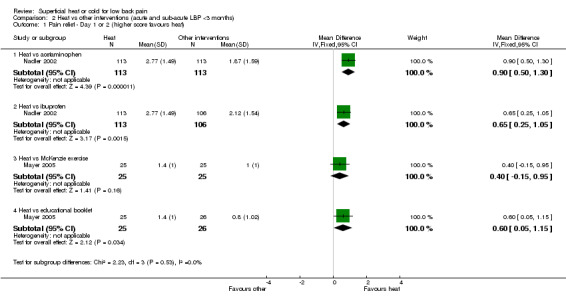

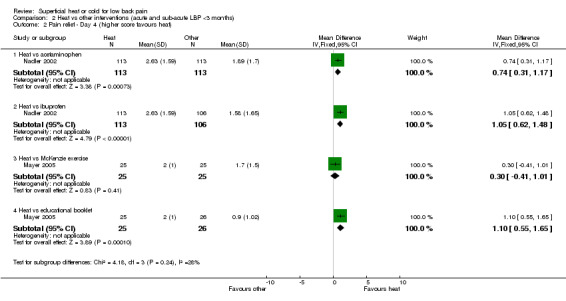

Three higher quality trials compared a heated back wrap to oral ibuprofen (Nadler 2002; Nadler 2003a; Nadler 2003b), and one of these trials also included a comparison group that took oral acetaminophen (Nadler 2002). Unfortunately, none of these trials presented data in a way that could be combined in a meta‐analysis. One trial (Nadler 2002) found that a heated back wrap provided significantly greater pain relief and improved function than oral ibuprofen and oral acetaminophen after both one day and four days of treatment. The other two Nadler trials did not provide results for this comparison.

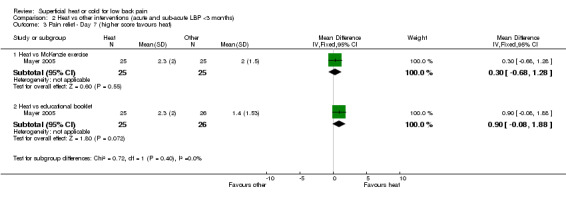

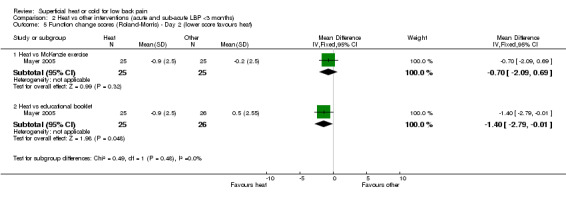

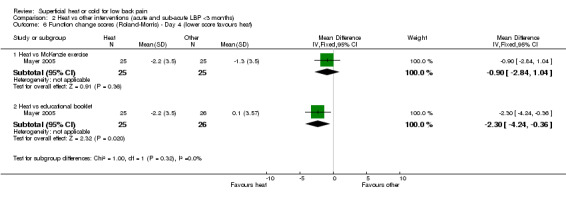

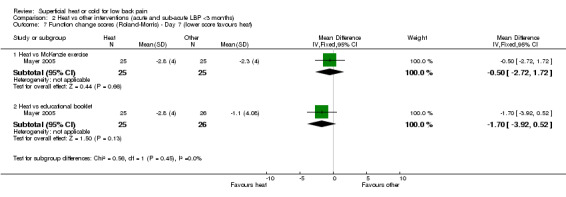

One high quality trial of 100 participants compared a heated back wrap alone to exercise alone and to an education booklet (Mayer 2005). Measured at one and four days after randomisation, the heat wrap provided significantly more pain relief than an educational booklet (Day 2: WMD 0.60, 95%CI 0.05 to 1.15, scale range 0 to 5); Day 4: WMD 1.10, 95%CI 0.55 to 1.65)) but not more than McKenzie exercise (Day 2: WMD 0.40, 95%CI ‐1.15 to 0.95); Day 4: WMD 0.30, 95%CI ‐0.41 to 1.01)). At seven days after randomisation, there were no significant differences in pain relief between the groups. The heat wrap provided significantly improved function compared to an educational booklet at Day 2 (WMD ‐1.40, 95%CI ‐2.79 to ‐0.01, scale range 0 to 24) and Day 4 (WMD ‐2.30, 95%CI ‐4.24 to ‐0.36)) but not at Day 7 (WMD ‐1.70, 95%CI ‐3.92 to 0.52)). There was no significant difference in function between heat wrap and McKenzie exercise at either Day 2, Day 4 or Day 7.

One lower quality non‐randomised cross‐over trial compared a wool body belt providing warmth to a lumbar corset in chronic low‐back pain participants (St John Dixon 1972). No pain results were provided.

Comparison 05: Cold versus other interventions

Only one low quality non‐randomised cross‐over trial examined this comparison (Melzack 1980). This trial compared ice massage to transcutaneous electrical stimulation (TES) in chronic low‐back pain participants. The trial concluded that ice massage and TES were equally effective in reducing pain.

Comparison 06: Heat plus exercise versus other interventions

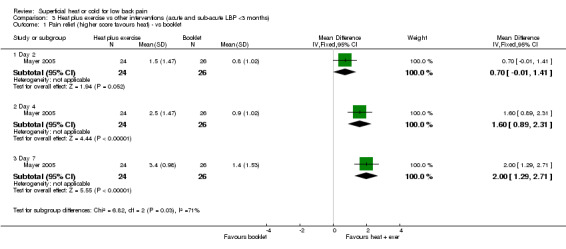

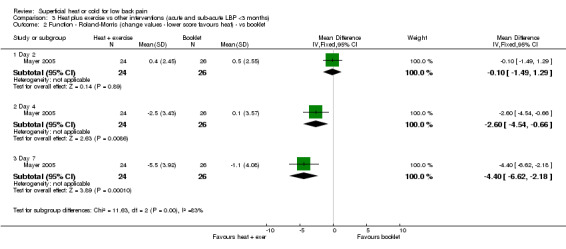

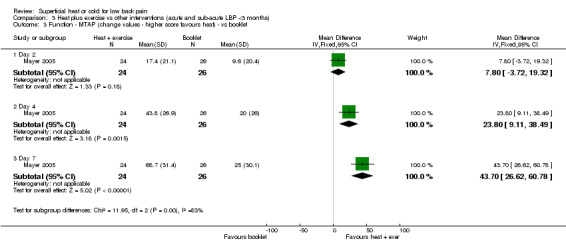

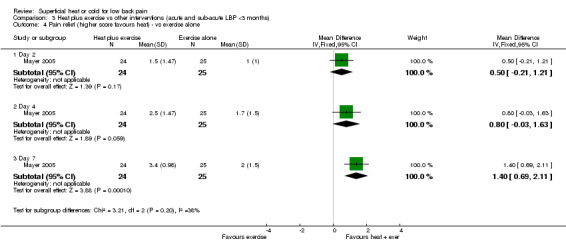

One higher quality trial of 100 participants combined a heated back wrap with exercise and compared this to heat alone, exercise alone and to an educational booklet, in participants with a mix of sub‐acute and acute low‐back pain (Mayer 2005). Heat wrap plus exercise provided significantly more pain relief than an educational booklet at Day 4 (WMD 1.60, 95%CI 0.89 to 2.31, scale range 0 to 5) and Day 7 (WMD 2.00, 95%CI 1.29 to 2.71)), and also for function (Roland Morris) (Day 4: WMD ‐2.60, 95%CI ‐4.54 to ‐0.66); Day 7: WMD ‐4.40, 95%CI ‐6.62 to ‐2.18)). Heat wrap plus exercise also provided significantly more pain relief and improvement in function than either heat or exercise alone at Day 7. This improvement in pain and function was not evident at the earlier time periods measured (Day 2 or Day 4).

Clinical relevance

Additional table Table 2 shows the clinical relevance assessment. The median score for the trials was three out of five. The higher quality trials generally had a higher clinical relevance score.

2. Clinical relevance.

| Item | Landen 1967 | Mayer 2005 | Melzack 1980 | Nadler 2002 | Nadler 2003a | Nadler 2003b | Nuhr 2004 | Roberts 1992 | St John Dixon 1972 |

| Patients | ‐ | + | + | + | + | + | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Interventions | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Relevant outcomes | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Size of effect | ? | ? | + | + | + | + | + | + | ? |

| Benefits and harms | ? | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ? |

| Score | 1/5 | 3/5 | 4/5 | 4/5 | 4/5 | 4/5 | 3/5 | 3/5 | 1/5 |

Discussion

Only a few studies have been published evaluating the effects of superficial heat or cold for low‐back pain. We found nine trials involving 1117 participants that were suitable for inclusion in this review. Of these, six trials examined heat compared to no heat or other interventions, one compared cold to another intervention and two trials compared heat to cold. The included trials were very heterogeneous in terms of interventions used, control treatments, outcome measures, timing of follow‐up and presentation of data. Therefore, it was not possible to perform any meaningful meta‐analyses, and it was difficult to reach firm conclusions for most types of treatments.

According to the qualitative criteria for levels of evidence, for a mixed population with acute and sub‐acute low‐back pain, there is moderate evidence that a heated wrap applied for eight hours, or an electric blanket applied for 25 minutes, are both better than no heat for pain in the short‐term (four days). There is moderate evidence (one small high quality RCT) that heat wrap is better for pain and function than an educational booklet during the early stages of treatment (days two to four), but not after seven days. There is moderate evidence that combining heat wrap with McKenzie exercises is better for pain relief and function after seven days than an educational booklet and either heat wrap or exercise alone. The effect of these treatments was small. If the short‐term beneficial effects of this therapy can be verified in further high quality trials, then its use would be valuable.

There is empirical data that indicate that industry‐funded studies are more likely to be positive than non‐funded studies (Bhandari 2004; Djulbegovic 2000; Kjaergard 2002). The results of the Nadler series of studies and the Mayer study of heat wrap therapy should be considered with this in mind, and independent studies would be useful to verify their results. Also, considering the cost of the disposable heat wraps, it would be useful to include a cost‐effectiveness analysis in future trials.

No randomised controlled trials were located that examined the effects of cold for low‐back pain. Given that this it is a commonly held belief that cold is beneficial for recent onset musculoskeletal injuries (Bleakley 2004), it was surprising that no studies were located that applied cold treatment to acute low‐back pain. In fact, in the trials conducted with participants with acute and sub‐acute low‐back pain, heat was applied. The trials that were located for cold treatment used cold for chronic low‐back pain and were of poor methodological quality. No conclusions can be drawn for the use of cold treatment in low‐back pain.

There is conflicting evidence when comparing heat treatment to cold treatment. Two low quality non‐randomised trials of chronic low‐back pain participants were located. One concluded that hot packs and cold packs were equally effective and the other concluded that ice massage was better than either hot packs or cold packs.

There were no major adverse events reported in any of the trials. Some minor events were reported with the heat wrap therapy, in the form of "skin pinkness" that resolved quickly.

There are methodological challenges when conducting high quality trials into these therapies. For example, it is questionable whether or not participants can be blinded to these interventions. The Nadler series of studies and the Nuhr study attempted to blind participants by including a non‐heated wrap or blanket and an oral placebo group, however the investigators did not measure whether participants could determine if they were receiving an active therapy or not. Also, outcome assessors should be blinded to the allocation of the participants to at least improve the quality of this aspect of the trials. It is recommended that these methodological issues are considered in future trials.

Heat and cold are modalities that are commonly used in practice in conjunction with other interventions, especially in the physical therapy professions. We only found one small study that evaluated the use of heat combined with exercise, and we found no study that examined cold in this context. Thus, no conclusions can be drawn regarding the use of heat or cold in combination with other therapies, other than in combination with exercise.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Heat and cold are commonly recommended by clinicians for low‐back pain. The evidence base to support this common practice is not strong. There is moderate evidence that continuous heat wrap therapy reduces pain and disability in the short term, in a mixed population with acute and sub‐acute low back pain (up to three months), and that the addition of exercise to heat wrap therapy further reduces pain and improves function. This evidence is limited to a small number of trials using a relatively small number of participants, and the size of the effect is small. The application of cold treatment to low‐back pain is even more limited, with only three poor quality studies located. No conclusions can be drawn about the use of cold for low‐back pain. There is conflicting evidence to determine the differences between heat and cold for low‐back pain.

Implications for research.

Many of the studies were of poor methodological quality and there certainly is a need for future higher‐quality RCTs. Also, many trials were poorly reported, and we recommend that authors use the CONSORT statement as a model for reporting RCTs (www.consort‐statement.org). The results of the majority of the studies could not be pooled with other studies because of the way the authors reported the results. Therefore, we suggest that the publications of future trials report, for continuous measures, means with standard deviations or means with standard error of means, and for dichotomous measures, number of events and total participants analysed.

Future research should focus on areas where there are few or no trials, for example, simple heat applications like hot water bottles, ice massage versus no cold and heat versus cold treatment, and trials in chronic low‐back pain participants. The classification of duration of low‐back pain was not consistent in the different studies, and in the future, authors should be clear on the definition of acute, sub‐acute and chronic low‐back pain, and report the duration of pain in their results. Future studies should be adequately powered and have both a short‐term follow‐up (for acute pain) and a long‐term follow‐up (for chronic pain).

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 19 January 2011 | Amended | Contact details updated. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 2, 2004 Review first published: Issue 1, 2006

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 16 March 2010 | Amended | Contact details updated. |

| 17 February 2010 | Amended | Contact details updated. |

| 23 November 2009 | Amended | Contact details updated. |

| 13 June 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 12 October 2005 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Substantive amendment |

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Judy Clarke, Laura Coe, Carla Cooper, Yngve Falck‐Ytter, Anne Keller, Peter Kroeling, Suzanna Mitrova, Wu Taixiang and Simona Vecchi for translation of non‐English language articles. We thank Ashoke Mitra and Kurt Weingand for providing us with information regarding the Nadler studies, and John Mayer for the extra data from his trial. We thank the Back Review Group, and in particular Vicki Pennick, for their ongoing encouragement and assistance while carrying out this review.

Appendices

Appendix 1. MEDLINE search strategy

1. randomized controlled trial.pt. 2. controlled clinical trial.pt 3. Randomized Controlled Trials/ 4. Random Allocation/ 5. Double‐Blind Method/ 6. Single‐Blind Method/ 7. or/1‐6 8. Animal/ not Human/ 9. 7 not 8 10. clinical trial.pt. 11. exp Clinical Trials/ 12. (clin$ adj25 trial$).tw. 13. ((singl$ or doubl$ or trebl$ or tripl$) adj25 (blind$ or mask$)).tw. 14. Placebos/ 15. placebo$.tw. 16. random$.tw. 17. Research Design/ 18. (latin adj square).tw. 19. or/10‐18 20.19 not 8 21. 20 not 9 22. Comparative Study/ 23. exp Evaluation Studies/ 24. Follow‐Up Studies/ 25. Prospective Studies/ 26. (control$ or prospective$ or Volunteer$).tw. 27. Cross‐Over Studies/ 28. or/22‐27 29. 28 not 8 30. 29 not (9 or 21) 31. 9 or 21 or 30 32. low back pain/ 33. low back pain.tw. 34. backache.tw. 35. lumbago.tw. 36. or/32‐35 37. 31 and 36 38. (heat$ or hot or warm$).tw. 39. (infrared or infra‐red).tw. 40. poultice.tw. 41. (spa$ or sauna$ or shower$ or steam$).tw. 42. Cryotherapy/ 44. (cryotherapy or ice or cool or cold).tw. 44. or/38‐43 45. 37 and 44

Appendix 2. EMBASE search strategy

1. clinical article/ 2. clinical study/ 3. clinical trial/ 4. controlled study/ 5. randomized controlled trial/ 6. major clinical study/ 7. double blind procedure/ 8. multicenter study/ 9. single blind procedure/ 10. crossover procedure/ 11. placebo/ 12. Or/1‐11 13. allocat$.ti,ab 14. assign$.ti,ab 15. blind$.ti,ab 16. (clinic$ adj25 (study or trial)).ti,ab 17. compare$.ti,ab 18. control$.ti,ab 19. cross?over.ti,ab 20. factorial$.ti,ab 21. follow?up.ti,ab 22. placebo$.ti,ab 23. prospectiv$.ti,ab 24. random$.ti,ab 25. ((singl$ or doubl$ or trebl$ or tripl$) adj25 (blind$ or mask$)).ti,ab 26. trial.ti,ab 27. (versus or vs).ti,ab 28. Or/13‐27 29. 12 or 28 30. human/ 31. nonhuman/ 32. animal/ 33. animal experiment/ 34. 31 or 32 or 33 35. 30 and 34 36. 29 not 34 37. 29 and 35 38. 36 or 37 39. low back pain/ 40. back pain.tw 41. backache.tw 42. lumbago.tw 43. Or/39‐42 44. (heat$ or hot or warm$).tw 45. (infrared or infra‐red).tw 46. poultice.tw 47. (spa$ or sauna$ or shower$ or steam$).tw 48. Cryotherapy/ 49. (cryotherapy or ice or cool or cold).tw 50. Or/44‐49 51. 38 and 43 and 50

Appendix 3. CENTRAL search strategy

1. BACK PAIN explode all trees (MeSH) 2. back pain or backache or lumbago 3. #1 or #2 4. CRYOTHERAPY explode all trees (MeSH) 5. cryotherapy or ice or cool or cold 6. heat* or hot or warm* or infrared or infra‐red or poultice or spa* or sauna* or shower* or steam* 7. #4 or #5 or #6 8. #3 and #7

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Heat vs placebo or non‐heated wrap (acute and sub‐acute LBP <3 months).

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Pain relief (higher score favours heat) | 2 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 Short‐term (up to day 5) | 2 | 258 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.06 [0.68, 1.45] |

| 1.2 Long‐term | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 2 Pain affect (lower score favours heat) | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 2.1 Short‐term (day 2 through day 4) | 1 | 67 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐13.5 [‐21.27, ‐5.73] |

| 2.2 Long‐term | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 3 Function (lower score favours heat) | 2 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 3.1 Short‐term (day 4) | 2 | 258 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐2.12 [‐3.07, ‐1.18] |

| 3.2 Long‐term | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 4 Pain (VAS) (lower score favours heat) | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 4.1 Short‐term | 1 | 90 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐32.20 [‐38.69, ‐25.71] |

| 4.2 Long‐term | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Heat vs placebo or non‐heated wrap (acute and sub‐acute LBP <3 months), Outcome 1 Pain relief (higher score favours heat).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Heat vs placebo or non‐heated wrap (acute and sub‐acute LBP <3 months), Outcome 2 Pain affect (lower score favours heat).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Heat vs placebo or non‐heated wrap (acute and sub‐acute LBP <3 months), Outcome 3 Function (lower score favours heat).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Heat vs placebo or non‐heated wrap (acute and sub‐acute LBP <3 months), Outcome 4 Pain (VAS) (lower score favours heat).

Comparison 2. Heat vs other interventions (acute and sub‐acute LBP <3 months).

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Pain relief ‐ Day 1 or 2 (higher score favours heat) | 2 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 Heat vs acetaminophen | 1 | 226 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.90 [0.50, 1.30] |

| 1.2 Heat vs ibuprofen | 1 | 219 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.65 [0.25, 1.05] |

| 1.3 Heat vs McKenzie exercise | 1 | 50 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.40 [‐0.15, 0.95] |

| 1.4 Heat vs educational booklet | 1 | 51 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.60 [0.05, 1.15] |

| 2 Pain relief ‐ Day 4 (higher score favours heat) | 2 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 2.1 Heat vs acetaminophen | 1 | 226 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.74 [0.31, 1.17] |

| 2.2 Heat vs ibuprofen | 1 | 219 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.05 [0.62, 1.48] |

| 2.3 Heat vs McKenzie exercise | 1 | 50 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.30 [‐0.41, 1.01] |

| 2.4 Heat vs educational booklet | 1 | 51 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.1 [0.55, 1.65] |

| 3 Pain relief ‐ Day 7 (higher score favours heat) | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 3.1 Heat vs McKenzie exercise | 1 | 50 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.30 [‐0.68, 1.28] |

| 3.2 Heat vs educational booklet | 1 | 51 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.90 [‐0.08, 1.88] |

| 4 Function (Roland‐Morris) ‐ Day 4 (higher score favours heat) | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 4.1 Heat vs acetaminophen | 1 | 226 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.00 [0.86, 3.14] |

| 4.2 Heat vs ibuprofen | 1 | 219 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.2 [1.11, 3.29] |

| 5 Function change scores (Roland‐Morris) ‐ Day 2 (lower score favours heat) | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 5.1 Heat vs McKenzie exercise | 1 | 50 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.7 [‐2.09, 0.69] |

| 5.2 Heat vs educational booklet | 1 | 51 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐1.4 [‐2.79, ‐0.01] |

| 6 Function change scores (Roland‐Morris) ‐ Day 4 (lower score favours heat) | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 6.1 Heat vs McKenzie exercise | 1 | 50 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.90 [‐2.84, 1.04] |

| 6.2 Heat vs educational booklet | 1 | 51 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐2.30 [‐4.24, ‐0.36] |

| 7 Function change scores (Roland‐Morris) ‐ Day 7 (lower score favours heat) | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 7.1 Heat vs McKenzie exercise | 1 | 50 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.5 [‐2.72, 1.72] |

| 7.2 Heat vs educational booklet | 1 | 51 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐1.70 [‐3.92, 0.52] |

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Heat vs other interventions (acute and sub‐acute LBP <3 months), Outcome 1 Pain relief ‐ Day 1 or 2 (higher score favours heat).

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Heat vs other interventions (acute and sub‐acute LBP <3 months), Outcome 2 Pain relief ‐ Day 4 (higher score favours heat).

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Heat vs other interventions (acute and sub‐acute LBP <3 months), Outcome 3 Pain relief ‐ Day 7 (higher score favours heat).

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Heat vs other interventions (acute and sub‐acute LBP <3 months), Outcome 4 Function (Roland‐Morris) ‐ Day 4 (higher score favours heat).

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Heat vs other interventions (acute and sub‐acute LBP <3 months), Outcome 5 Function change scores (Roland‐Morris) ‐ Day 2 (lower score favours heat).

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Heat vs other interventions (acute and sub‐acute LBP <3 months), Outcome 6 Function change scores (Roland‐Morris) ‐ Day 4 (lower score favours heat).

2.7. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Heat vs other interventions (acute and sub‐acute LBP <3 months), Outcome 7 Function change scores (Roland‐Morris) ‐ Day 7 (lower score favours heat).

Comparison 3. Heat plus exercise vs other interventions (acute and sub‐acute LBP <3 months).

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Pain relief (higher score favours heat) ‐ vs booklet | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 Day 2 | 1 | 50 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.7 [‐0.01, 1.41] |

| 1.2 Day 4 | 1 | 50 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.6 [0.89, 2.31] |

| 1.3 Day 7 | 1 | 50 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.0 [1.29, 2.71] |

| 2 Function ‐ Roland‐Morris (change values ‐ lower score favours heat) ‐ vs booklet | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 2.1 Day 2 | 1 | 50 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.10 [‐1.49, 1.29] |

| 2.2 Day 4 | 1 | 50 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐2.6 [‐4.54, ‐0.66] |

| 2.3 Day 7 | 1 | 50 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐4.4 [‐6.62, ‐2.18] |

| 3 Function ‐ MTAP (change values ‐ higher score favours heat) ‐ vs booklet | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 3.1 Day 2 | 1 | 50 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 7.80 [‐3.72, 19.32] |

| 3.2 Day 4 | 1 | 50 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 23.80 [9.11, 38.49] |

| 3.3 Day 7 | 1 | 50 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 43.7 [26.62, 60.78] |

| 4 Pain relief (higher score favours heat) ‐ vs exercise alone | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 4.1 Day 2 | 1 | 49 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.5 [‐0.21, 1.21] |

| 4.2 Day 4 | 1 | 49 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.80 [‐0.03, 1.63] |

| 4.3 Day 7 | 1 | 49 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.4 [0.69, 2.11] |

| 5 Function ‐ Roland‐Morris (change values ‐ lower score favours heat) ‐ vs exercise alone | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

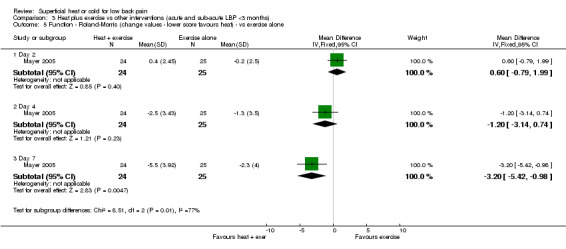

| 5.1 Day 2 | 1 | 49 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.60 [‐0.79, 1.99] |

| 5.2 Day 4 | 1 | 49 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐1.2 [‐3.14, 0.74] |

| 5.3 Day 7 | 1 | 49 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐3.20 [‐5.42, ‐0.98] |

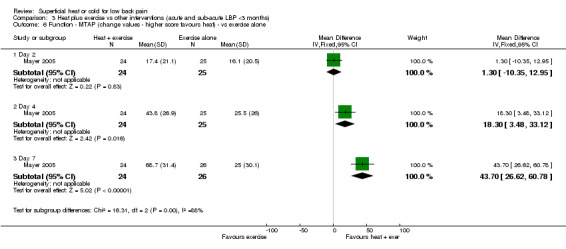

| 6 Function ‐ MTAP (change values ‐ higher score favours heat) ‐ vs exercise alone | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 6.1 Day 2 | 1 | 49 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.30 [‐10.35, 12.95] |

| 6.2 Day 4 | 1 | 49 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 18.30 [3.48, 33.12] |

| 6.3 Day 7 | 1 | 50 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 43.7 [26.62, 60.78] |

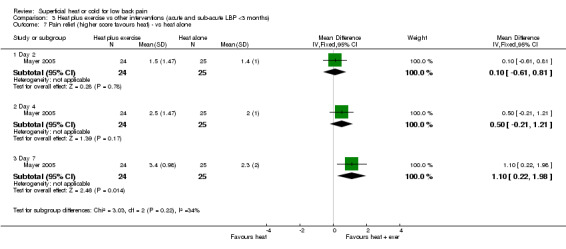

| 7 Pain relief (higher score favours heat) ‐ vs heat alone | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 7.1 Day 2 | 1 | 49 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.10 [‐0.61, 0.81] |

| 7.2 Day 4 | 1 | 49 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.5 [‐0.21, 1.21] |

| 7.3 Day 7 | 1 | 49 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.1 [0.22, 1.98] |

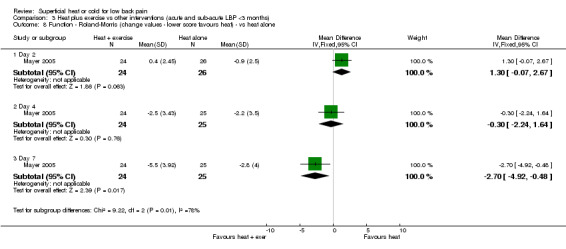

| 8 Function ‐ Roland‐Morris (change values ‐ lower score favours heat) ‐ vs heat alone | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 8.1 Day 2 | 1 | 50 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.3 [‐0.07, 2.67] |

| 8.2 Day 4 | 1 | 49 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.30 [‐2.24, 1.64] |

| 8.3 Day 7 | 1 | 49 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐2.7 [‐4.92, ‐0.48] |

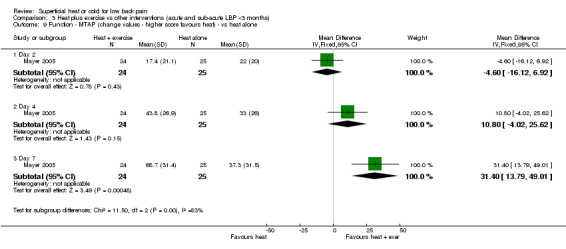

| 9 Function ‐ MTAP (change values ‐ higher score favours heat) ‐ vs heat alone | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 9.1 Day 2 | 1 | 49 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐4.60 [‐16.12, 6.92] |

| 9.2 Day 4 | 1 | 49 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 10.80 [‐4.02, 25.62] |

| 9.3 Day 7 | 1 | 49 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 31.40 [13.79, 49.01] |

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Heat plus exercise vs other interventions (acute and sub‐acute LBP <3 months), Outcome 1 Pain relief (higher score favours heat) ‐ vs booklet.

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Heat plus exercise vs other interventions (acute and sub‐acute LBP <3 months), Outcome 2 Function ‐ Roland‐Morris (change values ‐ lower score favours heat) ‐ vs booklet.

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Heat plus exercise vs other interventions (acute and sub‐acute LBP <3 months), Outcome 3 Function ‐ MTAP (change values ‐ higher score favours heat) ‐ vs booklet.

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Heat plus exercise vs other interventions (acute and sub‐acute LBP <3 months), Outcome 4 Pain relief (higher score favours heat) ‐ vs exercise alone.

3.5. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Heat plus exercise vs other interventions (acute and sub‐acute LBP <3 months), Outcome 5 Function ‐ Roland‐Morris (change values ‐ lower score favours heat) ‐ vs exercise alone.

3.6. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Heat plus exercise vs other interventions (acute and sub‐acute LBP <3 months), Outcome 6 Function ‐ MTAP (change values ‐ higher score favours heat) ‐ vs exercise alone.

3.7. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Heat plus exercise vs other interventions (acute and sub‐acute LBP <3 months), Outcome 7 Pain relief (higher score favours heat) ‐ vs heat alone.

3.8. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Heat plus exercise vs other interventions (acute and sub‐acute LBP <3 months), Outcome 8 Function ‐ Roland‐Morris (change values ‐ lower score favours heat) ‐ vs heat alone.

3.9. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Heat plus exercise vs other interventions (acute and sub‐acute LBP <3 months), Outcome 9 Function ‐ MTAP (change values ‐ higher score favours heat) ‐ vs heat alone.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Landen 1967.

| Methods | Non‐randomised CCT ‐ Alternate allocation ‐ Setting: US Army General Hospital, Germany ‐ Funding: not reported ‐ Follow‐up: not reported | |

| Participants | 143 participants with mix of acute and chronic low‐back pain Gender and age not described. 117 participants completed follow‐up. Inclusion criteria: Non‐specific low back pain. Exclusion criteria: Definite diagnosis of disk herniation | |

| Interventions | 1) Hot packs: twice daily for 20 mins, across lumbosacral area (n = 59). 2) Ice massage: twice daily with cubes of ice across lumbosacral area, moved slowly until numbing occurred, usually 10 to 12 mins (n = 58). Cointerventions: All participants also performed flexion exercises. | |

| Outcomes | 1) Pain ‐ participant reported change in symptoms ‐ minimal, moderate or marked increase or decrease in pain, or no change. 2) Length of hospitalisation 3) Muscular spasm ‐ not described how measured Timing of outcome measures: time of discharge | |

| Notes | Language: English Additional information from authors: No Author conclusions: "Ice massage and hot packs seem equally effective in the symptomatic relief of low back pain." | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | High risk | |

| Allocation concealment? | High risk | Alternate allocation |

| Blinding? All outcomes ‐ patients? | High risk | |

| Blinding? All outcomes ‐ providers? | High risk | |

| Blinding? All outcomes ‐ outcome assessors? | High risk | |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes ‐ drop‐outs? | Low risk | |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes ‐ ITT analysis? | High risk | |

| Similarity of baseline characteristics? | Unclear risk | Unclear from text |

| Co‐interventions avoided or similar? | Unclear risk | Cointerventions: All participants also performed flexion exercises. |

| Compliance acceptable? | Low risk | |

| Timing outcome assessments similar? | Unclear risk | Unclear from text |

Mayer 2005.

| Methods | RCT ‐ allocation method not described ‐ Setting: outpatient medical facilities in California, United States ‐ Funding: Procter and Gamble, manufacturer of heat wrap ‐ Follow‐up: 92% at 7 days | |

| Participants | 100 participants (29M, 71F) with acute (less than 3 months) nonspecific low back pain; duration of pain not reported; mean age 31.2 yrs Inclusion criteria: pain more than 2 days and less than 3 months duration with at least a 2‐month pain‐free period before the current episode; 18 to 55 yrs; no traumatic injury within 48 hrs of enrollment; low‐back pain intensity score of moderate or greater on a 6‐point verbal rating scale (2 or more); rating of perceived capacity from the MTAP less than 70%; fewer than 3 Waddell’s Non‐Organic Signs; candidate for active exercise; ambulatory; if female of child‐bearing potential, had a negative urine pregnancy test and was using an acceptable form of contraception. Exclusion criteria: evidence or history of radiculopathy (eg, numbness, tingling, or shooting pain extending below the knee) or other neurological deficits (eg, abnormal straight leg raise test, patellar reflexes, and/or bowel and bladder function); history of spinal surgery, kidney problems, neuromuscular disorders, fibromyalgia, osteoporosis, diabetes mellitus, bleeding diseases, arthritis, malignancy, systemic disease, inflammatory disease, abnormal heat or cold sensitivity, poor circulation, peripheral vascular disorders; active tuberculosis; skin lesions (eg, rash, bruising, laceration) on the low back region, or skin conditions in other regions that were spreading (eg, poison ivy, urticaria); psychiatric or psychological disorders; history of alcohol and/or drug abuse within the past year; cardiovascular or orthopedic contraindications to flexibility exercise; resting blood pressure values outside of 90‐140/60‐90 mm Hg; applied topical medication to the low back within 24 hrs of enrollment; current involvement in a workers’ compensation, disability, or personal injury claim; spinal injection treatment within 6 mths before enrollment; participated in an investigational drug or device trial within 4 wks of enrollment. | |

| Interventions | 1) Heat wrap alone. Disposable ThermaCare Heat Wrap applied to lumbar area, 40 degrees C for 8 hrs per day for 5 consecutive days (n = 25).

2) McKenzie exercise alone (n = 25).

3) Heat wrap plus McKenzie exercise (n = 24).

4) Educational booklet. Participants were advised to closely follow the recommendations, except that they were asked to refrain from performing specific exercises for the low back, using heat or cold modalities, and receiving spinal manipulation (n = 26). Cointerventions not allowed, except for medication as required. |

|

| Outcomes | 1) Functional improvement: MTAP

2) Disability: Roland Morris

3) Pain relief: 6‐point verbal rating scale Timing of outcome measures: 2 days, 4 days and 7 days after randomisation. |

|

| Notes | Language: English Additional information from authors: Yes Author conclusions: "Combining continuous low‐level heat wrap therapy with directional preference‐based exercise therapy offers distinct advantages over either therapy alone for the treatment of acute low back pain. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Low risk | |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear; Allocation method not described |

| Blinding? All outcomes ‐ patients? | High risk | |

| Blinding? All outcomes ‐ providers? | High risk | |

| Blinding? All outcomes ‐ outcome assessors? | Unclear risk | Unclear from text |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes ‐ drop‐outs? | Low risk | |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes ‐ ITT analysis? | High risk | |

| Similarity of baseline characteristics? | Low risk | |

| Co‐interventions avoided or similar? | Low risk | Cointerventions not allowed, except for medication as required. |

| Compliance acceptable? | Low risk | |

| Timing outcome assessments similar? | Low risk | |

Melzack 1980.

| Methods | Non‐randomised cross‐over trial. ‐ alternate allocation ‐ Washout: not described. ‐ Setting: Pain centre, Canada ‐ Funding: Not reported ‐ Follow‐up: 100% at 2 wks, 68% at 1 to 12 months | |

| Participants | 44 participants (23M, 21F) with chronic low‐back pain, unresponsive to conventional care; mean duration of pain 7.4 yrs; aged 18 to 73. Majority of participants had undergone previous surgery. Inclusion criteria: chronic low back pain which failed to respond to conventional treatment. Exclusion criteria: Severe emotional problems as determined by Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory. | |

| Interventions | 1) Ice massage: ice cube was gently massaged on the skin for a maximum 7 mins at 3 sites (midline low back, lateral malleolus and popliteal space) with 3 mins between applications, with a total treatment time of 30 mins. The ice massage was administered by a "technician" 2) Transcutaneous electrical stimulation (TES): 2 treatments of TES at the same 3 sites and time interval. The stimulation voltage was adjusted to a mildly painful level and administered simultaneously at all 3 sites for 30 mins Interventions were administered on 2 occasions at 1to 2 week intervals. The treatment for each group was reversed after the initial 2 treatment sessions with a further 2 treatments of the alternate intervention. Cointerventions not reported. | |

| Outcomes | 1) Pain ‐ McGill pain questionnaire. Conducted immediately after treatment sessions.

2) Preferred treatment Timing of outcome measures: pain measured before and after each treatment session, then 1 to 12 months after completing treatment |

|

| Notes | Language: English Additional information from authors: No Author conclusions: "ice massage is an effective therapeutic tool, and is more effective than TES for some patients". | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | High risk | Non‐randomised cross‐over trial |

| Allocation concealment? | High risk | alternate allocation |

| Blinding? All outcomes ‐ patients? | High risk | |

| Blinding? All outcomes ‐ providers? | High risk | |

| Blinding? All outcomes ‐ outcome assessors? | Unclear risk | Unclear from text |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes ‐ drop‐outs? | Unclear risk | Unclear from text |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes ‐ ITT analysis? | High risk | |

| Similarity of baseline characteristics? | Unclear risk | Unclear from text |

| Co‐interventions avoided or similar? | Low risk | Cointerventions not reported. |

| Compliance acceptable? | High risk | |

| Timing outcome assessments similar? | Low risk | |

Nadler 2002.

| Methods | RCT ‐ allocation method not described ‐ Setting: clinical research sites ‐ Funding: Procter and Gamble, manufacturer of heat wrap ‐ Follow‐up: 98% at Day 4 | |

| Participants | 371 participants (155M, 216F) with acute (less than 3 months) non‐specific low‐back pain; duration of pain not reported; mean age 36.0 yrs Inclusion criteria: Pain (2 or more on 6‐point scale), 18 to 55 yrs, ambulatory, no low‐back trauma within last 48 hrs, and yes to "do muscles in your low back hurt?" Exclusion criteria: Evidence or history of radiculopathy or other neurologic deficits (eg, abnormal straight‐leg‐raise test results, patellar reflexes, or bowel or bladder function), or a history of back surgery, fibromyalgia, diabetes mellitus, peripheral vascular disease, osteoporosis, gastrointestinal ulcers, gastrointestinal bleeding or perforation, renal disease, pulmonary edema, cardiomyopathy, liver disease, intrinsic coagulation defects, bleeding diseases or anticoagulant therapy (eg, warfarin), daily back pain for more than three consecutive months, or hypersensitivity to acetaminophen, NSAIDs, or heat. | |

| Interventions | 1) Heat wrap (ThermaCare Heat Wrap; Procter and Gamble) that wraps around lumbar region of torso, heats to 40 degrees C within 30 mins exposure to air & maintains this temp continuously for 8h. Worn for approx 8h per day (n = 113)

2) Oral ibuprofen: 2 tablets 3 times daily for a total dose of 1200 mg, plus oral placebo 1 time daily (n = 106)

3) Oral acetaminophen: 2 tablets 4 times daily for a total of 4000 mg dose (n = 113)

4) Oral placebo: 2 tablets 4 times daily (n = 20)

5) Unheated back wrap: (n = 19) Cointerventions not allowed |

|

| Outcomes | 1) Pain: 6‐point verbal scale of pain relief

2) Muscle stiffness: 101‐point scale

3) Disability: Roland‐Morris (0 to 24 scale)

4) Lateral trunk flexibility

5) Adverse effects Timing of outcome measures: pain relief and disability measured daily for 4 days post‐randomisation |

|

| Notes | Language: English Additional information from authors: Yes Author conclusions: "continuous low‐level topical heat wrap therapy is superior to both acetaminophen and ibuprofen, supporting its recommendation as a first‐line therapy for the treatment of acute muscular low back pain" | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | Unclear from text |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear; allocation method not described |

| Blinding? All outcomes ‐ patients? | High risk | |

| Blinding? All outcomes ‐ providers? | High risk | |

| Blinding? All outcomes ‐ outcome assessors? | Low risk | |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes ‐ drop‐outs? | Low risk | |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes ‐ ITT analysis? | Low risk | |

| Similarity of baseline characteristics? | Low risk | |

| Co‐interventions avoided or similar? | Low risk | Cointerventions not allowed |

| Compliance acceptable? | Unclear risk | Unclear from text |

| Timing outcome assessments similar? | Low risk | |

Nadler 2003a.

| Methods | RCT ‐ allocation method not described ‐ Setting: clinical research sites ‐ Funding: Procter and Gamble, manufacturer of heat wrap ‐ Follow‐up: 95% at Day 5 | |

| Participants | 219 participants (100M, 119F) with acute (less than 3 months) non‐specific low‐back pain; duration of pain not reported; mean age 36.1 yrs Inclusion criteria: Acute nonspecific LBP with pain intensity of moderate or higher (more than 1 on 6‐point scale), age 18‐55 years, ambulatory, no traumatic injury within the previous 48h, with an answer "yes" to the question, "Do the muscles in your low back hurt?" Exclusion criteria: Pregnancy, evidence or history of radiculopathy (eg, sciatica extending below the knee [numbness, tingling, shooting pain]) or other neurologic deficits (eg, abnormal straight‐leg raising test, patellar reflexes, bowel and/or bladder function), history of back surgery, fibromyalgia, diabetes mellitus, peripheral vascular disease, osteoporosis, gastrointestinal ulcers, gastrointestinal bleeding or perforation, renal disease, pulmonary edema, cardiomyopathy, liver disease, intrinsic coagulation defects, bleeding diseases, or anticoagulant therapy (eg, warfarin), subjects enrolled in any investigational drug or device trials, skin lesions (eg, rash, bruising, swelling, irritation, laceration, excoriation, ulceration) on the lumbar region, history of alcohol and/or drug abuse, current litigation or a worker's compensation claim involving low back disability, back pain daily for more than 3 consecutive months, hypersensitivity to NSAIDs or heat. | |

| Interventions | 1) Heat wrap (ThermaCare Heat Wrap) that wraps around lumbar region of torso, heats to 40°C within 30 mins of exposure to air and maintains this temperature continuously for 8h. Worn for 3 consecutive days, approx 8h per day (n = 95)

2) Oral placebo: 2 tablets, 3 times daily, spaced 6h apart (n = 96)

3) Oral ibuprofen: 200mg, 2 tablets, 3 times daily, spaced 6h apart (n = 12)

4) Unheated wrap: (n = 16) Cointerventions not allowed |

|

| Outcomes | 1) Pain: 6‐point verbal scale of pain relief

2) Muscle stiffness: 101‐point scale

3) Disability: Roland‐Morris (0 to 24)

4) Lateral trunk flexibility

5) Skin quality: 4‐point scale Timing of outcome measures: pain relief and disability measured daily for 4 days post‐randomisation |

|

| Notes | Language: English Additional information from authors: Yes Author conclusions: "Continuous low‐level heatwrap therapy was shown to provide significant therapeutic benefits in patients with acute nonspecific LBP, as indicated by increased pain relief and trunk flexibility, and it provided decreased muscle stiffness and disability when compared with placebo. No serious or significant adverse effects were observed during the use of the heatwrap." | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | Unclear from text |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear; allocation method not described |

| Blinding? All outcomes ‐ patients? | High risk | |

| Blinding? All outcomes ‐ providers? | High risk | |

| Blinding? All outcomes ‐ outcome assessors? | Low risk | |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes ‐ drop‐outs? | Low risk | |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes ‐ ITT analysis? | Low risk | |

| Similarity of baseline characteristics? | Low risk | |

| Co‐interventions avoided or similar? | Low risk | Cointerventions not allowed |

| Compliance acceptable? | Unclear risk | Unclear from text |

| Timing outcome assessments similar? | Low risk | |

Nadler 2003b.

| Methods | RCT ‐ allocation method not described ‐ Setting: clinical research sites ‐ Funding: Procter and Gamble, manufacturer of heat wrap ‐ Follow‐up: 92% at Day 5 | |

| Participants | 76 participants (27M, 49F) with acute (less than 3 months) nonspecific LBP; duration of pain not reported; mean age 41.4 yrs Inclusion criteria: pain intensity of moderate or higher, age 18 to 55 yrs, ambulatory status, muscular LBP of atraumatic origin (eg, no major traumatic injury within 48h of enrollment), and an answer of "yes" to the question "Do the muscles in your low back hurt?" Exclusion criteria: Pregnancy, regular insomnia for more than 1 wk or inability to remain sleeping for at least 6h at a time, evidence or history of radiculopathy or other neurologic deficits of the lower extremities, history of back surgery, fibromyalgia, diabetes mellitus, poor circulation, peripheral vascular disease, osteoporosis, gastrointestinal ulcers, gastrointestinal bleeding or perforation, renal disease, pulmonary edema, cardiomyopathy, liver disease, intrinsic coagulation defects, bleeding diseases or anticoagulant therapy, skin lesions (eg, rash, bruising, swelling, irritation, laceration, excoriation, ulceration) on the lumbar region, history of alcohol and/or drug abuse within the past year, current litigation or a worker's compensation claim involving low back disability, daily back pain for more than 3 consecutive months, and hypersensitivity to NSAIDs or heat. | |

| Interventions | 1) Heat wrap (ThermaCare Heat Wrap) that wraps around lumbar region of torso, heated to 104°F (40°C) within 30 mins of exposure to air and maintains this temperature continuously for 8h. Applied approx 15 to 20 mins before participants retired to bed for the night and worn during sleep for approximately 8h each night for 3 consecutive nights (n = 33).

2) Oral placebo: 2 tablets, administered approx 15 to 20 mins before participants retired to bed each night for 3 consecutive nights (n = 34).

3) Oral ibuprofen: 2 tablets; total dose, 400mg, administered approx 15 to 20 minutes before patients retired to bed each night for 3 consecutive nights (n = 4).

4) Unheated wrap, applied approx 15 to 20 mins before participants retired to bed for the night and were worn during sleep for approx 8h each night for 3 consecutive nights (n = 5). Cointerventions not allowed |

|

| Outcomes | 1) Pain relief ‐ 6‐point verbal rating scale

2) Muscle stiffness ‐ 101‐point numeric rating scale

3) Pain affect ‐ 101‐point numeric rating scale

4) Disability ‐ Roland‐Morris (0 to 24)

5) Lateral trunk flexibility

6) Subjective measures of sleep quality and difficulty in sleep onset ‐ 6‐point scale Timing of outcome measures: days 1 to 4 after commencement of treatment |

|

| Notes | Language: English Additional information from authors: Yes Author conclusions: "Continuous low‐level heatwrap therapy was shown to provide effective daytime pain relief after overnight use in subjects with acute nonspecific LBP. Additional therapeutic benefits included reduction of muscle stiffness, increased trunk flexibility, decreased disability, and improved sleep quality and onset of sleep. The heatwrap showed a good safety profile when worn during sleep and should be considered as an initial treatment strategy for patients with acute LBP". | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | Unclear from text |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear; allocation method not described |

| Blinding? All outcomes ‐ patients? | High risk | |

| Blinding? All outcomes ‐ providers? | High risk | |

| Blinding? All outcomes ‐ outcome assessors? | Low risk | |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes ‐ drop‐outs? | Low risk | |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes ‐ ITT analysis? | Low risk | |

| Similarity of baseline characteristics? | Low risk | |

| Co‐interventions avoided or similar? | Low risk | Cointerventions not allowed |

| Compliance acceptable? | Unclear risk | Unclear from text |

| Timing outcome assessments similar? | Low risk | |

Nuhr 2004.

| Methods | RCT ‐ randomisation was obtained with computer‐generated codes, which were sealed in sequentially numbered opaque envelopes. ‐ Setting: emergency site in Austria ‐ Funding: Vienna Red Cross ‐ Follow‐up: 100% immediately post‐treatment, no further follow‐up | |

| Participants | 90 participants (57M, 33F) with first episode acute (less than 6 hrs) low‐back pain; mean age 36.8 yrs (+/‐ 8.2). Inclusion criteria: low back pain greater then 60mm on a 100mm visual analog scale with no projection to the legs and less than 6 hours before the arrival of the emergency team. Exclusion criteria: analgesic medication for any reason within the last 48 hours, neurologic impairment of the legs, cognitive impairment and/or inability to communicate with the paramedics, an American Society of Anesthesiologists score greater than 3 (indicating systemic disease), low back pain from causes other than spinal or musculoskeletal disorders. Total initial enrolments was 100, however 10 participants excluded from analysis because subsequent investigations revealed pain was from other than spinal or muscular disorders. | |

| Interventions | 1) Resistive heating of 42 degrees C via a carbon‐fiber electric heating blanket (ThermaMed GmbH, Bad Oeynhausen, Germany) which was in turn covered by a single woolen blanket. The active heating component covered an area of 148 X 40 cm. Mean duration of treatment 24.8 +/‐ 8.1 mins. (n = 47)

2) Passive warming: Participant was covered with same carbon‐fiber electric heating blanket , which was in turn covered by a single woolen blanket. Heating of the electric blanket was not activated. Mean duration of treatment 26.2 +/‐ 9.3 mins. (n = 43)

For both groups, covers were positioned at the emergency site and remained in place until the participant arrived at the hospital. Cointerventions not allowed |

|

| Outcomes | 1) Pain measured on 100 point VAS, measured at arrival at hospital

2) Tympanic thermocouple (core temperature)

3) Skin thermosensors on the skin, and intracutaneous thermosensors at 4 mm depth next to the third lumbar processus spinosus. Additional skin sensors were placed on the forearm and finger to monitor indirect signs of vasodilation or vasoconstriction as a nonspecific measure of stress

4) Adverse effects All measurements were recorded by the same independent investigator blinded to the treatment with the electrical blanket, which he/she was forbidden to touch. Timing of outcome measures: all measured at arrival to hospital |

|

| Notes | Language: English Additional information from authors: No Author conclusions: "...local active warming is an effective and easy‐to‐learn emergency care treatment for acute low back pain that could be used by emergency physicians as well as by paramedical personnel". | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Low risk | Randomisation was obtained with computer‐generated codes, which were sealed in sequentially numbered opaque envelopes |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

| Blinding? All outcomes ‐ patients? | High risk | |

| Blinding? All outcomes ‐ providers? | High risk | |

| Blinding? All outcomes ‐ outcome assessors? | Low risk | |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes ‐ drop‐outs? | Low risk | |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes ‐ ITT analysis? | High risk | |

| Similarity of baseline characteristics? | Low risk | |

| Co‐interventions avoided or similar? | Low risk | Cointerventions not allowed |

| Compliance acceptable? | Low risk | |

| Timing outcome assessments similar? | Low risk | |

Roberts 1992.

| Methods | Non‐randomised cross‐over trial ‐ alternate allocation ‐ Setting: Pain centre, United States ‐ Funding: not reported ‐ Follow‐up: not reported | |

| Participants | 36 participants (17M, 19F), with chronic low‐back pain; mean duration of pain 4.6 yrs; aged 24 to 72 yrs (mean 40.4). All participants had failed to respond to traditional medical management. Inclusion criteria: Primary diagnosis of chronic low‐back pain. Exclusion criteria: Not reported. | |

| Interventions | 1) Hot pack (160 degrees F) with 6 to 8 layers of towels for 20 mins

2) Cold packs (0 degrees F) with 2 layers damp towels for 20 mins

3) Ice massage ‐ lightly rubbing low‐back with cake of ice 4.2 X 2 X 4.5 inches

Over 2‐week period, each participant was given two applications with each of the three interventions. Cointerventions: During study all participants were participating in a comprehensive pain rehabilitation program, including medication. |

|

| Outcomes | 1) Pain ‐ VAS (0 to 20) immediately after and 1 hour after intervention | |

| Notes | Language: English Additional information from authors: No Author conclusions: "Ice massage was found to be significantly more effective than either hot packs or cold packs for relief of chronic low‐back pain. The difference was still apparent 1h after treatment." | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | High risk | Non‐randomised cross‐over trial |

| Allocation concealment? | High risk | alternate allocation |

| Blinding? All outcomes ‐ patients? | High risk | |

| Blinding? All outcomes ‐ providers? | High risk | |

| Blinding? All outcomes ‐ outcome assessors? | High risk | |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes ‐ ITT analysis? | High risk | |

| Co‐interventions avoided or similar? | Unclear risk | Cointerventions: During study all participants were participating in a comprehensive pain rehabilitation program, including medication. |

| Timing outcome assessments similar? | Low risk | |

St John Dixon 1972.

| Methods | Non‐randomised cross‐over trial ‐ allocation not described ‐ Washout: not described. ‐ Setting: Orthopaedic outpatient department in United Kingdom ‐ Funding: Not described, although angora wool body belts provided by manufacturer ‐ Follow‐up: not reported | |

| Participants | 38 participants (12M, 24F) with chronic non‐specific low‐back pain; mean duration of pain 17 yrs (range 0.5 to 40 yrs); aged 30 to 80 yrs (mean 61 yrs) Inclusion criteria: chronic non‐specific low‐back pain. Exclusion criteria: Not described | |

| Interventions | 1) Medima angora wool body belt ("giving insulation and warmth without support")

2) Remploy "instant" lumbosacral corset ("giving support but little insulation")

Participants instructed to wear each intervention for one week Cointerventions not described. |

|

| Outcomes | 1) Preference for type of support

2) Pain (but no data reported)

3) Adverse effects Timing of outcome measures: All measured after one and two weeks |

|

| Notes | Language: English Additional information from authors: No Author conclusions: "The findings of this study call into question the common practice of prescribing a lumbosacral support for chronic, non‐specific, low back pain. Many patients fare equally well with a simple warm body belt." | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | Non‐randomised cross‐over trial |

| Allocation concealment? | High risk | Not described |

| Blinding? All outcomes ‐ patients? | High risk | |

| Blinding? All outcomes ‐ providers? | High risk | |