Over the past decades, the political tensions that regularly plague WHO have undermined its authority. Every time an international public health emergency has arisen, WHO has faced internal political gridlock.1 Confidence in the UN agency has dwindled with every health crisis. Today, no one disputes that the political functioning of WHO is an impediment to fulfilling its role as a global health crisis coordinator and promoter of science-based standards. The UN system is still dependent on world politics,2 the failings of which were far too evident during the first months of the COVID-19 crisis.3 In the near future, a comprehensive reform of global health governance will require bold changes, not cosmetic reforms.

Calls for reforming multilateral institutions have flourished in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.4 One way to rebuild the normative authority of WHO is to anchor the organisation in a renewed architecture that will give scientific communities greater influence in the global health ecosystem. Therefore, we advocate the creation of a new model of multilateral governance on the basis of the experience gained in two other areas of global public goods governance—climate change and biodiversity.

Since its creation in 1988, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has been instrumental in the emergence of a transnational epistemic community, putting governments under constant pressure from its projections and analyses on climate change.5 Contrary to widespread belief, the IPCC is not an independent cluster of scientists. It is a hybrid multilateral entity comprising 195 states. However, the substantive work of the IPCC is to do in-depth scientific reviews and produce assessment reports on the basis of a multiyear knowledge development process. It involves 2500 top scholars and researchers from a variety of disciplines, institutions, and geographical origins. The IPCC model has inspired the global governance for biodiversity. In 2013, the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) was established with a similar institutional structure, under the aegis of the UN.

Today the IPCC and IPBES experiences are generating a pioneering model for integration of science and policy at a global scale.6 Their authority stems from the establishment of independent working groups that use contradictory debate and peer-review methods. They operate within a worldwide scientific network protected from political pressure or bureaucratic interference. Admittedly, since the IPCC and IPBES remain intergovernmental entities, their reports sometimes end up with incomplete conclusions.7 However, their findings are usually unanimously approved and serve as a basis for negotiations at the Conference of the Parties on climate change and the Convention on Biological Diversity. They are also taken up in most organisations implementing the Sustainable Development Goals.

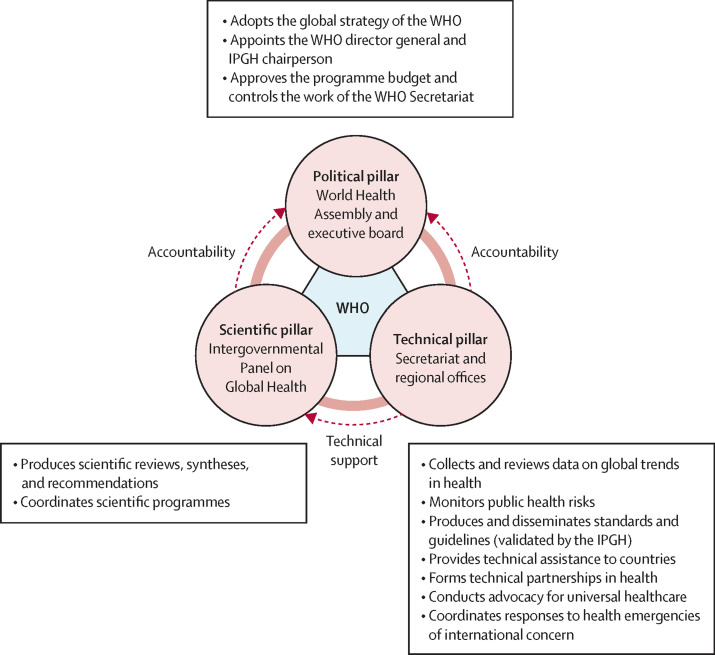

Future global health governance reform should draw on such institutional experiences. WHO should be overhauled with the creation of a new pillar—possibly called the Intergovernmental Panel on Global Health—involving a large network of scientists from various countries and disciplines (figure ). This network would be responsible for developing scientific consensus on major global health issues, which could serve as inputs to the development of the global agenda. The panel would be divided into three or four main permanent working groups reflecting major areas of knowledge in global health. These groups would be placed under the leadership of scientists, with technical support by the WHO coordination. They would be established on a parity basis ensuring a balanced representation of high-income and low-income countries. They would incorporate the existing WHO expert advisory groups and committees. A bureau elected by the World Health Assembly would supervise and coordinate the groups. Acting as a scientific steering body, the bureau would comprise the working group chairpersons and would be headed by an internationally renowned scientist for a fixed term. It would report scientific recommendations to the Assembly, with no intermediation by the WHO Director-General.

Figure.

A tripolar architecture for WHO

IPGH=Intergovernmental Panel on Global Health.

The panel would work as a highly decentralised global expert network, not as a technostructure parallel to the Geneva secretariat. The scientific secretariat of the working groups could be provided by universities. This polycentric model would ensure geographical diversity and greater connection to national research institutions, the media, cities, civil society organisations, and local communities. The model would foster global health awareness and education in various national contexts, putting upward pressure on those governments most reluctant to follow evidence-based approaches to health.

The panel could hold consultations with civil society organisations, as science cannot be separated from societal demands, but it would work independently from governments and private sector industries. It would not be accountable to the secretariat, whose role would be to concentrate the other activities of WHO, under the leadership of the Director-General, including international advocacy, guidelines and standards dissemination, technical assistance to countries, and coordination of international responses to health emergencies.

WHO should be revitalised in the future reform of global health governance, as it remains the only organisation with the capacity to transcribe shared scientific insights into international policy standards endorsed by governments. Depoliticising the WHO is the only way for governments to build international institutions that better protect their populations from global health threats. Giving a voice to the global scientific community would result in a more ambitious, consensual, and inclusive decision-making process in the global health ecosystem, putting the wisdom of science ahead of state politics and industrial lobbying.

We declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Gostin LO, Sridhar D, Hougendobler D. The normative authority of the World Health Organization. Public Health. 2015;129:854–863. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2015.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoffman SJ, Røttingen J-A. Split WHO in two: strengthening political decision-making and securing independent scientific advice. Public Health. 2014;128:188–194. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2013.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fidler DP. The World Health Organization and pandemic politics. The good, the bad, and an ugly future for global health. April 10, 2020. https://www.thinkglobalhealth.org/article/world-health-organization-and-pandemic-politics

- 4.Nay O. Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies; Geneva: 2020. The global health we need, the WHO we deserve. Global Health Centre Working Paper; pp. 1–47. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beck S, Mahony M. The IPCC and the new map of science and politics. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Clim Change. 2018;9:e547. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Borie M, Mahony M, Hulme M. Somewhere between everywhere and nowhere: the institutional epistemologies of IPBES and the IPCC. Resource Politics 2015, Institute of Development Studies; Sept 7–9, 2015.

- 7.De Pryck K. Expertise under controversy: the case of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). PhD thesis in political science, Sciences-Po Paris, 2018.