Abstract

We document and evaluate how businesses are reacting to the COVID-19 crisis through August 2020. First, on net, firms see the shock (thus far) largely as a demand rather than supply shock. A greater share of firms report significant or severe disruptions to sales activity than to supply chains. We compare these measures of disruption to their expected changes in selling prices and find that, even for firms that report supply chain disruptions, they expect to lower near-term selling prices on average. We also show that firms are engaging in wage cuts and expect to trim wages further before the end of 2020. These cuts stem from firms that have been disproportionally negatively impacted by the pandemic. Second, firms (like professional forecasters) have responded to the COVID-19 pandemic by lowering their one-year-ahead inflation expectations. These responses stand in stark contrast to that of household inflation expectations (as measured by the University of Michigan or the New York Fed). Indeed, firms’ one-year-ahead inflation expectations fell precipitously (to a series low) following the onset of the pandemic, while household measures of inflation expectations jumped markedly. Third, despite the dramatic decline in firms’ near-term inflation expectations, their longer-run inflation expectations have remained relatively stable.

Keywords: Business expectations, COVID-19, Demand shock, Inflation, Pandemic, Supply shock

“Now we see a big shock to demand, and we see core inflation dropping to 1%. And I do think for quite some time we’re going to be struggling against disinflationary pressures rather than against inflationary pressures.” — Chair Powell. Post–FOMC Press Conference. July 29, 20201

1. Introduction

By mid-March 2020, it was clear that a novel coronavirus (COVID-19) had reached the shores of the United States. State-mandated lockdowns temporarily shuttered many nonessential businesses, the U.S. government instituted travel bans to many countries, and, among businesses still open, many saw depressed levels of sales activity.2 Indeed, economic activity as measured by real GDP contracted at an annualized rate of 5% in the first quarter and by an astounding 32% in the second quarter, marking the COVID-19 crisis as the swiftest and most severe economic shock the U.S. has experienced in modern times.

Amid supply chain disruptions and alongside widespread shutdowns, production has been crimped. However, demand appears to have taken a bigger hit, as those emergency shutdowns have also left households shuttered in their homes, consumer spending has fallen dramatically, and business investment spending has dried up. Given the backdrop of low inflation since the onset of the Great Recession, the behavior of inflation expectations is of particular interest. In a recent speech, Fed governor Lael Brainard noted, “With underlying inflation running below 2% for many years and COVID contributing to a further decline, it is important that monetary policy support inflation expectations that are consistent with inflation centered on 2% over time”.3

In this paper, we utilize the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta’s Business Inflation Expectations Survey to uncover how firms are perceiving and reacting to the COVID-19 pandemic. Our analysis focuses on how this shock has affected their inflation expectations going forward. First, we examine whether firms, en masse, see the pandemic as a supply or demand shock. Our results suggest that, while elements of both a supply shock and a demand shock are present, firms, on net, view the COVID-19 pandemic as a demand shock. These findings are based on a series of quarterly and special questions that assess the level of disruption that COVID-19 has inflicted on sales activity, business operations, and supply chains; quantitative assessments of firms’ sales levels relative to “normal”; firms’ expected price changes over the near-term; firms’ experienced and expected wage changes; and changes in the inflation expectations from before to during the pandemic.

The literature disentangling firms’ perceptions of the COVID-19 pandemic is nascent, mixed, and can be loosely grouped into two strains. The first strain—which argues that demand shocks dominate—takes a broad approach to uncovering the perceptions of firms regarding the nature of the pandemic, eliciting direct evidence of changes in firms’ behavior, perceptions, and expectations. Hassan, Hollander, van Lent, and Tahoun (2020) analyze transcripts of quarterly earnings calls held by public firms across the globe and find concerns over a negative demand shock are nearly twice as prevalent as mentions of supply chain disruptions. In a survey of small firms, Bartik, Bertrand, Cullen, Glaeser, Luca, and Stanton (2020) find that respondents cited reductions in demand to a much larger degree than supply chain issues as reasons for temporary closures. And Meyer, McCord, and Waddell (2020) find that firms’ most pressing concerns are overwhelmingly centered on flagging demand and declining sales revenue, with the “health of the economy” coming in at a distant second and “supply chain concerns” registered as a much lower issue.4

The other strain of literature relies largely on inference rather than direct responses from business decision makers to conclude the pandemic as a supply shock. Brinca, Duarte, and Faria-e Castro (2020) use structural econometric methods to decompose changes in hours working into supply and demand shock contributions, finding that the supply shock contribution outweighs the demand shock contribution. Candia, Coibion, and Gorodnichenko (2020) suggest that some firms (and most households) see the pandemic as a supply shock, coming to that view through the lens of aggregate inflation expectations. Dietrich, Kuester, Muller, and Schoenle (2020), while focused on households, reach the same conclusion through survey research that elicits expectations for the COVID-19 pandemic’s impact on aggregate inflation. Importantly, our results, like Hassan et al. (2020), take a more holistic and direct approach to uncovering firms’ perceptions of the pandemic.

Second, consistent with a shortfall in demand, we document that the inflation expectations of businesses (like those of professional forecasters) have fallen precipitously. In fact, both firms’ perceptions of current inflation and their year-ahead inflation expectations fell to an all-time low (going back to October 2011) in April, as the pandemic grew in severity. We also document that household survey measures of inflation expectations—specifically the University of Michigan’s Survey of Consumers and the New York Fed’s Survey of Consumer Expectations—registered sharp increases in expectations relative to the pre-COVID period. We offer evidence that suggests households are disproportionately responding to a relative price shock to grocery store items, rather than viewing the COVID-19 pandemic as a negative shock to aggregate supply.

Third, despite the magnitude of the decline in their near-term inflation perceptions and expectations, firms’ longer-run expectations appear to be relatively stable. The relationship between a firm’s change in one-year-ahead expectations and the change in its longer-run inflation expectations from the pre-COVID period to during the crisis appears to be modest at best. Moreover, while the distribution of firms’ one-year-ahead inflation expectations has shifted markedly lower, this downward shift is not evident in firms’ longer-run (five- to ten-year-ahead) inflation expectations, suggesting that firms’ longer-run expectations are reasonably well anchored.

The rest of the paper proceeds as follows. Section 2 briefly discusses the data set. Section 3 analyzes how the COVID-19 shock affects firms’ sales levels, business operations, expected price changes, and wage changes. Sections 4, 5 focus on firms’ short-run and long-run inflation expectations during the crisis. Section 6 concludes.

2. About the survey

We use the microdata and special question results from the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta’s Business Inflation Expectations (BIE) survey. The BIE is a monthly survey of firms in the Sixth Federal Reserve District (which covers most of the southeastern United States) that has been fielded continuously since October 2011. Broadly speaking, the Sixth District mirrors the US in terms of cross-industry and cross-firm size breakdowns of business activity (sales revenue and employment). By design, the panel composition of the BIE roughly reflects the makeup of the national economy at the two-digit NAICS level (see Appendix Table B.1. Panels A and B).5

Of particular interest in disentangling firms’ perceptions of the nature of the pandemic is whether COVID-19 and the efforts to control the spread of the virus impacted Sixth District firms to a similar degree as it did the nation as a whole. To that end, while there are some differences between the Sixth District and the nation in the number of COVID-19 cases and deaths attributed to the virus (see Appendix H, Figure 27), high-frequency data on the stringency of government response to the virus, measures of retail and workplace mobility, interpersonal engagement, and restaurant bookings in the Sixth District broadly mirrored the nation (see Appendix H, Figures 28, 29, and 30). The direct regional prevalence of and response to COVID-19 determine the likely disruption to business operations (i.e., mandated shutdowns, temporary closures, employee absenteeism, shift toward a remote working posture, etc.) located and headquartered in the Sixth District. However, it is important to note that many of the firms located in the U.S. southeast have a national or international sales presence and exposure to the pandemic through globally interconnected supply chains.

Since its inception, using a method popularized by Manski (2004), the BIE survey has focused on the forward-looking unit costs (nominal marginal costs) of firms, eliciting firms’ probabilistic unit cost expectations for the year-ahead on a monthly basis and longer-run (five- to ten-year-ahead) probabilistic unit-cost expectations on a quarterly frequency. To state it plainly, our view is that firms’ unit-cost expectations are their inflation expectations, and aggregating up firms’ unit-cost expectations yields a measure of inflation expectations that is consistent with firm behavior. As shown in Meyer et al. (2021), this probabilistic measure of the inflation expectations of firms covaries strongly with the inflation expectations of professional forecasters, yields an inflation perception that mirrors current inflation trends, and is highly correlated with a national measure of probabilistic inflation expectations from the Survey of Business Uncertainty (SBU).6

While this paper is about understanding how firms are responding to the COVID-19 shock, we acknowledge that many readers will view the paragraph above as incongruent with the widely cited survey literature from Coibion, Gorodnichenko, and co-authors (2018, 2020) on firms’ aggregate inflation expectations and it is necessary to lay out an alternative viewpoint.7

Much of the confusion around survey measures of inflation expectations is tied directly to the survey respondents’ understanding of the concept of “inflation” and its usefulness in their decision making (i.e., whether the respondent understands the concept, has well-formed expectations, and whether the expectations they hold meaningfully impact their behavior).8 For the BIE survey, the choice to elicit unit-cost expectation instead of “aggregate” inflation expectations (or price change expectations) was motivated by a variety of theoretical, empirical, and survey design factors.

The microfoundations of the New Keynesian Phillips Curve suggest that firms make price-setting decisions on the basis of future nominal marginal (unit) costs; see Sbordone (2005). Under general conditions, an expectation of “aggregate” inflation will be an input (embedded) into a firm’s unit cost expectations (although, from an individual firm’s perspective, this is not a necessary condition). Still, if we hold to this view, each firm’s unit cost expectation is the sum of their aggregate inflation expectations and a firm-specific error term, reflecting firm-specific cost structure.9 Under reasonable assumptions, e.g., with many firms, the averaged unit cost expectation across firms is a proxy for aggregate inflation expectations. The evidence provided in this paper shows that the aggregated unit-cost expectations of firms are strongly related to the inflation expectations of professional forecasters (see Appendix Figure 16). Moreover, we show that the aggregated unit-cost perceptions of firms covary strongly with actual inflation (see Appendix Figure 15).10

Another consideration when choosing to elicit probabilistic unit cost expectations instead of a notion of “aggregate” inflation expectations for firms is that both in cognitive interviews and survey responses (see Appendix Figures 23, 24, and 25) firms indicated that unit-costs were more directly relevant to their price-setting decisions than “aggregate” inflation.11

One further consideration that is particularly relevant at the moment is that many surveys of aggregate inflation expectations ask respondents about “prices in general” or “prices overall in the economy”. Given the vagueness of the wording, these survey questions are likely to elicit expectations about particular salient price changes (such as prices of grocery store items or of gasoline). Armantier et al., 2013, Armantier et al., 2016 provide evidence that changes in wording around the concept of inflation have a material impact on the responses. Moreover, Bryan et al. (2015) and Meyer et al. (2021) highlight that when firms are presented with language that clues them in to the idea that “aggregate” inflation or “prices in general” means changes in the Consumer Price Index, the typical biases tend to dissipate. This is also true of a new survey of firms’ inflation expectations from Olivier Coibion and Yuriy Gorodnichenko.12 As we discuss in Section 4, we view this pandemic as furthering the distinction between business and household inflation expectations.

In addition to its core focus on inflation expectations, the BIE survey elicits firms’ qualitative judgments and quantitative estimates regarding firms’ sales levels, margins, and other factors thought to drive businesses’ pricing decisions. The questionnaire also contains space for researchers to ask special questions that are policy-relevant, topical, or related to broader academic research. In this paper, we make use of firms’ quantitative assessments of their sales “gap”—current sales levels relative to normal—as well as a series of special questions designed to uncover firms’ assessments of disruptions that incurred due to the novel coronavirus, their expectations for their own price changes, and what they anticipate for the path of the virus. A detailed discussion of the data, the specific form of the questions we pose to respondents, and survey descriptions can be found in the appendix.13

3. How do firms view the COVID-19 shock?

While early news reports of empty grocery shelves have made it clear that the pandemic is crimping some supply chains, at the same time, widespread efforts to control the spread of the virus caused schools, restaurants, and hotels to temporarily close, leading many farmers and food producers to destroy unused food products amid the free-fall in demand.14

Cochrane (2020), Kharas and Triggs (2020), and others all point out that the COVID pandemic is unlike a standard recessionary (aggregate demand) shock or a typical inflationary supply shock (oil prices shock). This “health shock” has characteristics of both. Guerrieri, Lorenzoni, Straub, and Werning (2020) present a model that suggests that severe negative supply shocks (like the COVID-19 shock) can lead to a shortfall in aggregate demand that outweighs the effects of the initial supply shock. On the other hand, Abo-Zaid and Sheng (2020) present a dynamic general equilibrium model with a health shock, finding that, while health shocks have significant supply-side effects on economic activity, the demand-side effects are considerably bigger, particularly for shorter horizons and more rigid prices. In relation to both papers, the question is whether firms see the COVID shock, on net, as more of a supply shock or a demand shock. If firms view the pandemic largely as a supply shock, standard theory would expect their unit (marginal) costs to increase amid higher input prices and wages. Firms would also be likely to attempt to pass on these unit cost increases by increasing prices and, ultimately, lead firms to anticipate higher inflation in the future. Firms experiencing a demand shock would behave conversely (experience lower costs, lower wages and prices, and anticipate lower future inflation).15

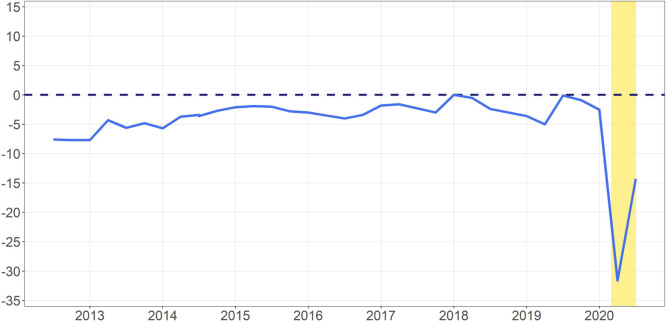

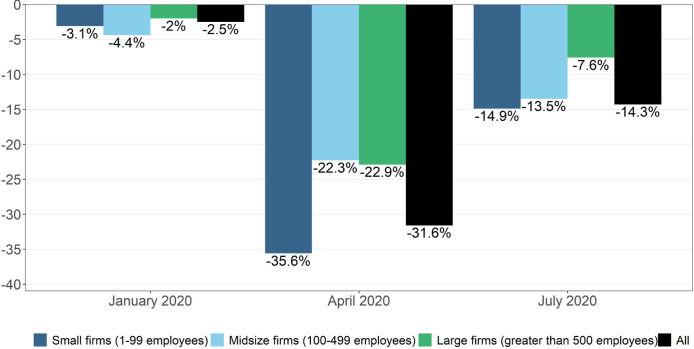

The overwhelmingly negative nature of the shock to firms’ sales levels is evident in Fig. 1. Recovering from the 2007–2009 financial crisis and recession, firms’ quantitative sales gap measure had slowly been moving toward zero (or “normal” sales levels) alongside solid gains in output growth and previously strong job gains. However, that all changed in April 2020. Firms surveyed from April 6 to 10, showed an extraordinarily large decline in sales levels relative to normal—from 2.5% below normal in the first quarter to 32% below normal in April (see the charts). The decline in sales had an impact on firms of all sizes, but smaller firms reported a much larger hit to sales than did firms with more than 100 employees, as evidenced in Fig. 2. Firms’ assessment of sales gaps rebounded somewhat in July, but remains solidly negative.

Fig. 1.

Firms’ percentage below “normal” sales levels.

Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta’s Business Inflation Expectations Survey.

Fig. 2.

Firms’ mean quantitative sales gap by firm size.

Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta’s Business Inflation Expectations Survey.

These results are very similar to the pattern we see in high-frequency and macroeconomic data we have in hand thus far into the pandemic.16 These patterns are also consistent with other business survey findings that elicit the anticipated impact the coronavirus will have in 2020 (see Altig et al. (2020b) and Bloom, Fletcher, and Yeh (2020)). Of course, a sharp widening in the sales gap could be due to either a supply shock or a demand shock.

To disentangle whether firms see COVID-19 as mainly a supply or demand shock, we asked a series of special questions starting in April 2020 as a supplement to our core survey questionnaire. Our line of questioning began with attempting to elicit direct responses on the nature of the COVID-related disruption to operations, sales activity, and supply chains. We then related their responses to these questions to changes in expected prices, actual and anticipated changes in wages, and changes to firms’ inflation perceptions and expectations.

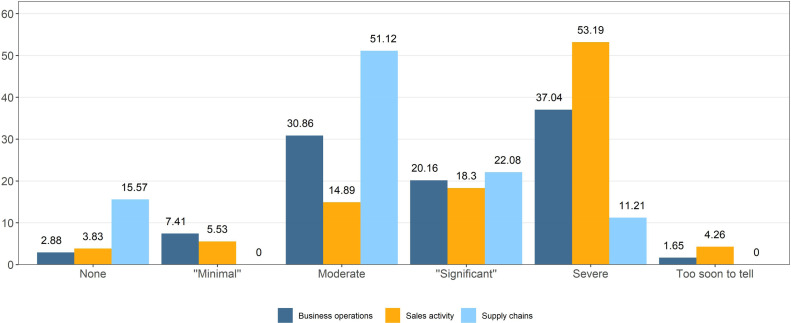

In April, we asked firms to assess the level of disruption by the pandemic to their business operations, supply chains, and sales activity on a scale of “no disruption” to “severe disruption”.17 As shown in Fig. 3, more than half the firms surveyed indicated severe disruption to their sales activity and another 18% indicated “significant” disruption to sales activity. This compares to just over 10% of firms that indicated severe disruption to supply chains. The median respondent indicated moderate disruption to supply chains stemming from the pandemic.

Fig. 3.

Level of disruption by activity type. Notes: There were 243 observations to the business operations question, 235 to the sales activity question, and 212 to the supply chains question. The supply chains questions did not contain responses corresponding to “Minimal” or “Too soon to tell”. The correlation between responses to operations and sales activity: 0.54, and the correlation between supply chains and sales activity: 0.22. The specific questions asked are given in Appendix A.

Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta’s Business Inflation Expectations Survey, April and May 2020.

Table 1 relates a firm’s response to their level of disruption across business operations, sales activity, and supply chains. The mean sales gap across these categories aligns most closely with disruption to sales activity. Indeed, even firms that indicated no supply disruption had a sharply negative sales gap. Among those firms experiencing severe disruption, sales levels fell to roughly one-half relative to normal sales conditions. Similar to Barrero et al. (2020), these results suggest that the disruption associated with the outbreak has not hit all firms equally. There is evidence of dispersion (reallocation) across firms, as a small share of firms that indicated they are experiencing low levels of disruption are seeing stronger-than-usual sales levels.18 Our findings also related favorably to a national survey of CFOs, which, in June 2020, elicited firms’ most pressing concerns over the previous three months in an open-text format, finding six times more frequent mentions of concerns over flagging demand than over supply chain concerns.19

Table 1.

Mean quantitative sales gap by level of disruption.

| Operations | Sales | Supply | |

|---|---|---|---|

| None | 3% | 7% | 16% |

| “Minimal” | 10% | 4% | – |

| Moderate | 20% | 7% | 18% |

| “Significant” | 19% | 15% | 43% |

| Severe | 51% | 52% | 55% |

Notes: Responses from the financial industry are excluded. There are 206 observations from “operations”, 193 from “sales activity”, and 166 for “supply”. The correlation between the quantitative sales gap and sales distribution, disruption to operations, and supply chain disruption is −0.64, −0.48, and −0.35, respectively. The missing value in the Supply column is due to that month’s survey having one fewer response option than the operations and sales questions. The specific questions asked are located in Appendix A.

Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta’s Business Inflation Expectations Survey, March and April, 2020.

The pandemic led firms to lower prices. In April 2020, we followed up the disruption questions with a question regarding firms’ expectations for their own selling prices over the next six months. The intention was to evaluate firms’ anticipated price changes by their disruption to sales activity. As Table 2(A) indicates, the majority of firms anticipated holding prices constant over the next six months, though nearly twice as many firms anticipated decreasing their selling price than increasing it. For those firms expecting to change their price, the magnitudes are sizeable. The median expectation among those anticipating to decrease prices over the next six months is −13.5%. For those anticipating to increase, the median expectation is a 5% increase. While, as with sales gaps, there is quite a bit of dispersion in expectations, the thrust of price pressures has a definite downside tilt. Firms, on average, anticipate lowering prices by 2.2% over the six-month period from April to October; see Table 2(B).

Table 2.

Firms’ response to expected price change questions.

| Panel A: Share of firms expecting a price change | |

| Change in price | Share of firms |

| Increase | 15.0% |

| Decrease | 26.0% |

| Remain the same | 59.0% |

| Panel B: Expected price change over the next six months | |

| Statistic | Expected price change |

| Mean | |

| Median | 0.0% |

| P10 | |

| P90 | 5.0% |

| Panel C: Expected price change by level of disruption to sales activity | |

| Level of sales disruption | Expected price change |

| None | 4.6% |

| “Minimal” | |

| Moderate | |

| “Significant” | |

| Severe | |

Note: There were 239 observations for the responses in Panels (A)–(C). The specific questions asked are located in Appendix A.

Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta’s Business Inflation Expectations Survey April 2020.

Table 2(C) also offers further evidence that firms see the pandemic as a demand shock. The right-hand table shows the mean expected price change by level of sales disruption. Firms indicating no negative disruption to sales activity anticipate increasing selling prices by 4.6% on average (nearly every firm expecting to increase prices indicated “no” negative sales disruption in April), while those experiencing severe disruption to sales activity anticipate lowering prices by 3.2% on average.

Panels (A) and (B) in Table 3 corroborate the notion that firms see COVID-19 largely as a demand shock. These tables compare mean expected price changes by variety degrees of sales gap and the severity of supply chain disruption. Interestingly, and counter to what standard theory would suggest about supply shocks, firms that indicated they were experiencing supply chain disruption anticipated lowering prices over the next six months, rather than increasing them. For firms experiencing severe supply chain disruption, the mean expected price change was a striking −15.5%. And here, a further examination of the microdata indicates that all of the firms experiencing severe supply chain disruption experienced significant or severe sales disruption as well. Firms that were doubly impacted by supply chain and sales disruptions indicated lowering prices, on average, suggesting that COVID-19 has been much more of a demand than a supply shock.

Table 3.

Firms’ expected price change by quantitative sales gap and level of supply chain disruption.

| Panel A: Expected price change by mean quantitative sales gap | |

| Sales gap | Expected price change |

| 0% | |

| 25% | |

| Panel B: Expected price change by level of disruption to supply chains | |

| Level of supply chain disruption | Expected price change |

| None | 7.3% |

| “Some” | |

| “Significant” | |

| Severe | |

Note: There were 239 observations for the responses in Panel (A) and 189 for the responses in Panel (B). Of the firms experiencing severe supply chain disruption in Panel (B), all of them noted significant or severe sales disruption as well. The specific questions asked are given in Appendix A.

Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta’s Business Inflation Expectations Survey April 2020.

Simply documenting that firms expect to lower prices, on average, over the next six months is insufficient evidence, on its own, to conclude that firms view COVID-19 as a demand shock. For one, a six-month window is short enough to be affected by nominal price-stickiness (see Bils and Klenlow (2004)), assuming price-setting behavior is time-dependent (see Klenow and Kryvtsov (2008)). Fairness considerations may also have stayed the hands of firms that would have otherwise increased prices (see Kahneman, Knetsch, and Thaler (1986)). And, as Gagnon and Lopez-Salido (2020) point out, this may be particularly true of firms’ price-setting strategies surrounding an unexpected (and large) demand shock.

Still, our evidence suggests that firms’ expected near-term pricing decisions are related to whether their sales activity has been negatively disrupted by COVID-19. This is just one piece in a collection of evidence (including firms’ direct responses to questions regarding supply and demand shocks, their current and forward-looking wage decisions, and their inflation expectations) that indicate, on net, firms’ view the pandemic as a demand shock.

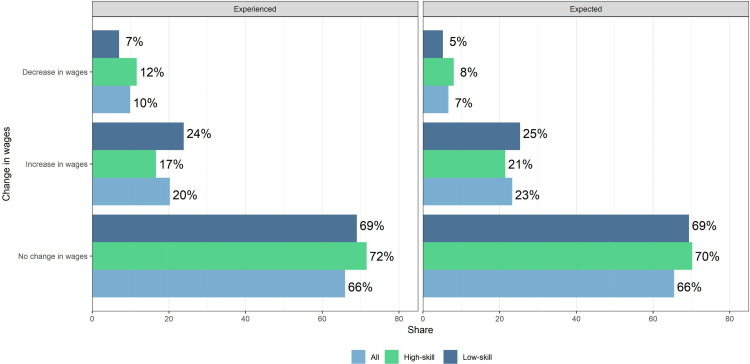

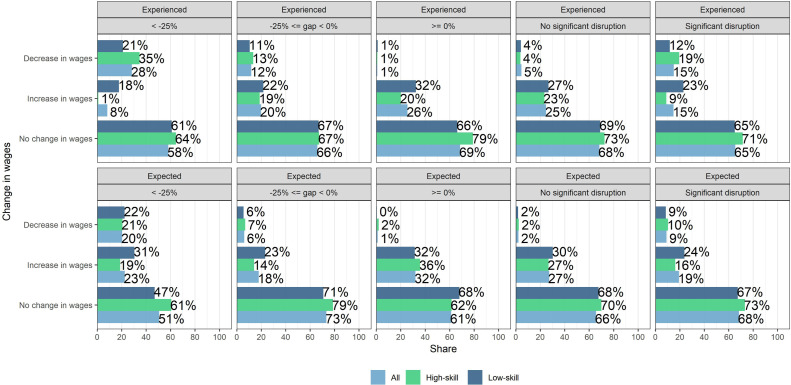

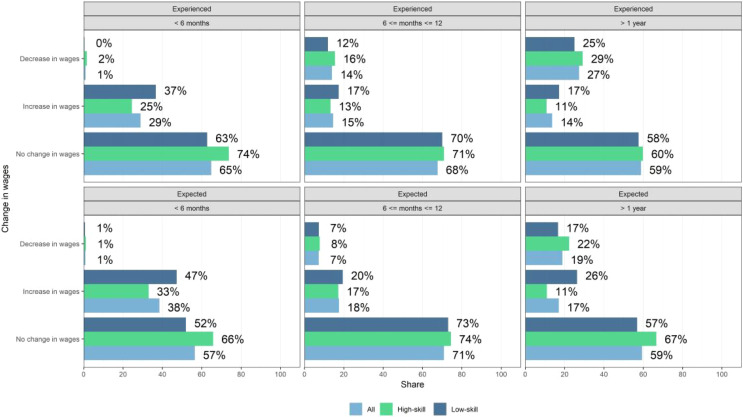

In addition to firms’ expected price changes, we also offer evidence from firms’ wage-setting behavior that corroborates the view that firms see COVID-19, on net, as a demand shock. In August 2020, we asked firms in the BIE to, first, characterize their workforce between “high-skilled” and “low-skilled” labor and followed up with questions eliciting what share of their (high-and-low skilled) workforce has seen increases, decreases, or no change in their wages since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. We followed with a similar question on anticipated wage changes from the current period until the end of 2020.20

Fig. 4 shows that firms cut nominal wages for 10% of continuing employees, a result that is nearly identical to what Cajner et al. (2020) find using administrative payroll data. The apparent lessening of downward nominal rigidity during the COVID-19 pandemic is quite unusual. As Cajner et al. note in their paper, the prevalence of these wage cuts is roughly twice what continuing employees experienced during the entirety of the Great Recession.21 Interestingly and perhaps somewhat worrisome, our results suggest that firms anticipate further negative wage adjustments by the end of the year.

Fig. 4.

Firms’ experienced and expected wage changes. Notes: Respondents were only asked about their wage changes for a skill level if they indicated the presence of a low-skill or high-skill workforce. There were 160 responses for the low-skill experienced and expected wage change, 175 for the high-skill experienced wage change, and 176 for the high-skill expected wage change. The specific questions asked are given in Appendix A.

Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta’s Business Inflation Expectations Survey, August 2020.

Fig. 5 sheds further light on the nature of the COVID-19 shock. Firms hit the hardest by the shock are those that are disproportionately engaging in wage cuts. This holds both for the severity of the sales disruption and for the severity of the shortfall in a firm’s quantitative sales gap. These responses on the part of business decision makers to cut wages given dramatic declines in sales activity and amid severe disruption due to the pandemic further bolster the claim that demand shocks are overpowering supply shocks. If supply shocks were dominating, standard theory would suggest upward pressure on wages. These results stand in contrast to the findings by Brinca et al. (2020) that use a structural Bayesian VAR to decompose changes in hours worked by sector into supply and demand shock contributions and conclude that the supply shocks dominate. Our results indicate that firms view the enormous impact that the pandemic is having on economic activity as, on net, a demand shock. On average, firms anticipate lowering prices in the near future and much of that downward price pressure is stemming from firms disproportionately impacted by the virus (even among those that noted significant or severe supply chain disruption). These findings are supported by the material (and unusually high) share of negative nominal wage adjustments that we have seen so far during this crisis and those that firms anticipate over the remainder of the year. Moreover, other business surveys, such as in Bartik et al. (2020) tell a consistent story. In fact, they note, “Respondents that had temporarily closed [early in the pandemic] largely pointed to reductions in demand and employee health concerns as the reasons for closure, with disruptions in the supply chain being less of a factor”.22 We view these results as corroborating evidence. And while the Business Response Survey shows the breadth of demand vs. supply shocks, our work is able to further disentangle how firms perceived these shocks through their behavior and expectations.

Fig. 5.

Firms’ experienced and expected wage changes by quantitative sales gap and level of sales disruption. Notes: The low-skill expected and experienced values are based on were 149 responses, 164 and 165 responses to the high-skill questions, and 332 responses for the all sales disruption category. Additionally, the sales gap category had 152 responses for the low-skill expected and experienced values, 167 and 168 responses to the high-skill questions, and 338 responses for the “all” category. The specific questions are given in Appendix A.

Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta’s Business Inflation Expectations Survey July and August 2020.

4. COVID-19’s impact on inflation expectations

Alongside the freefall in demand, COVID-19 has also had a significant impact on inflation expectations. Specifically, the pandemic has lowered businesses’ and professional forecasters’ inflation expectations over the year ahead, while simultaneously causing household inflation expectations to increase markedly. In this section, we provide evidence that firms and households view COVID-19 in fundamentally different ways, with firms and forecasters responding to the shock by ratcheting down their expectations in sharp contrast with the expectations held by households.

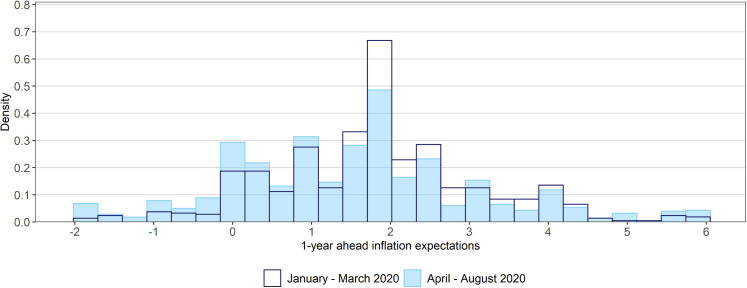

Consistent with firms’ collective judgment that COVID-19 is more of a demand than a supply shock, they have ratcheted down their inflation expectations markedly. Businesses’ probabilistic one-year-ahead inflation expectations fell to a series low of 1.4% in April 2020. Fig. 6 shows the distribution of respondents’ expected values. A clear downshift in expectations is evident starting in April 2020.23 Prior to April, the majority of firms’ expectations were centered on 2% and there was very little mass in the tails. We can also see this downshift in the mean probabilities assigned to each bin. After the onset of the pandemic, the mean probability assigned to the lowest bin (corresponding to negative cost growth) nearly doubled—from 6% to 11%.

Fig. 6.

Distribution of firms’ short-run inflation expectations from January to August 2020. Notes: There were 690 and 1,113 responses in the pre-COVID and COVID time periods, respectively. The specific question is given in Appendix A.

Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta’s Business Inflation Expectations Survey; January to August 2020.

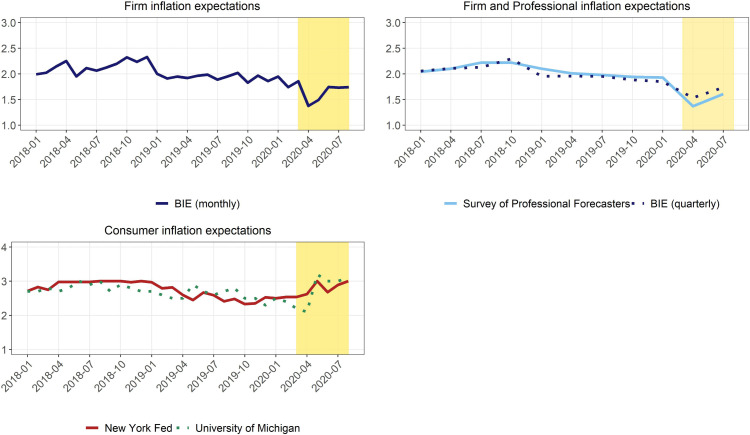

Fig. 7 compares one-year-ahead inflation expectations across businesses (from the BIE survey), professional forecasters (SPF survey), and households (from the University of Michigan and from the New York Fed’s Survey of Consumer Expectations (SCE)).24 The yellow shaded area corresponds with the COVID-19 pandemic. The stark contrast in responses between firms and professionals (sharply lowering expectations) and households (sharply increasing expectations) is clear. It is worth noting that all three of these groups held higher inflation expectations in 2018, a period marked by escalating tension over global trade, increased tariffs, and higher costs of production.

Fig. 7.

Inflation expectations of consumers, firms, and professionals. Notes: The yellow shaded regions begin in March 2020 and signal the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in the U.S.

Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta’s Business Inflation Expectations Survey, Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Survey of Consumer Expectations, Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia’s Survey of Professional Forecasters, and the University of Michigan’s Survey of Consumers.

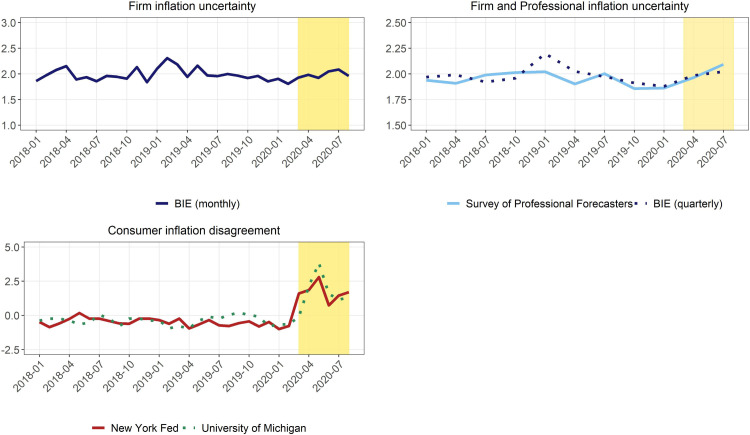

Fig. 8 plots one-year-ahead uncertainty measures from these three groups, and, again, the difference between the reaction from businesses and professionals to that of households is clear. By May 2020, household one-year-ahead inflation uncertainty in the SCE had jumped up to a series high (the series began in mid-2013). On the other hand, inflation uncertainty measures of firms and professional forecasters ticked up, but remained below their respective levels in 2018–19. Firms, in particular, do not appear to be overly uncertain about the likely direction over the coming year. Despite the severity of the crisis and consistent with lower demand, on net, firms expect inflation to slow.

Fig. 8.

Inflation uncertainty of consumers, firms, and professionals. Notes: Uncertainty for the BIE is measured as the mean of the variance of firm inflation expectations, while it is measured as the dispersion between the forecasts for the SPF. Additionally, the SPF series is re-scaled to the level of the quarterly BIE. The yellow shaded regions begin in March 2020 and signal the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in the U.S.

Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta’s Business Inflation Expectations Survey, Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Survey of Consumer Expectations and Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia’s Survey of Professional Forecasters.

These results do raise the question as to why well-known measures of household inflation expectations have risen sharply in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. Here, we highlight that the recent household survey literature around the pandemic’s impact on inflation expectations finds mixed results. A high-frequency consumer survey conducted by the Cleveland Fed, designed to understand how consumers are reacting to COVID-19, indicated early on that consumers anticipate inflation to increase by roughly five to seven percentage points over the next year as a result of the COVID-19 shock.25 Armantier et al. (2020) find the COVID-19 shock had a disparate impact on demographic groups, with higher educated (and, presumably, higher income) individuals actually lowering their inflation expectations. Following a probabilistic approach used by the BIE and in the NY Fed’s SCE, Coibion, Gorodnichenko, and Weber (2020) find that households under lockdown actually lowered their inflation expectations moderately.26 In addition Binder (2020a) finds that household inflation expectations vary by their level of concern regarding the effect of COVID-19 on the U.S. economy, with those concerned tending to have much higher inflation expectations.

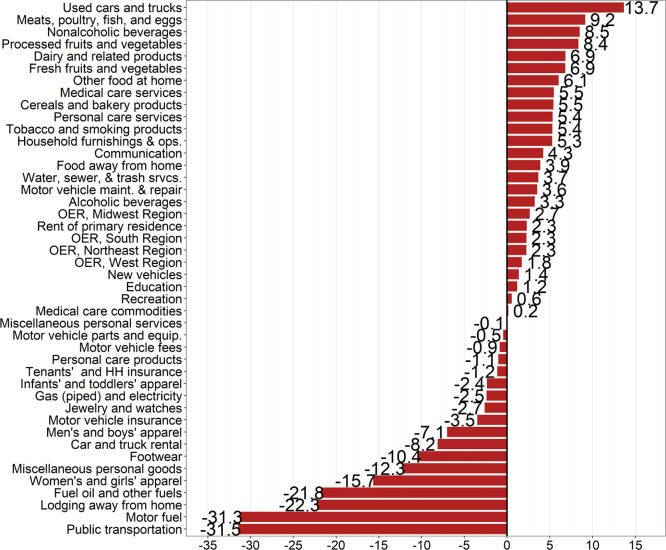

The divergence between the inflation expectations of businesses and households may be partly due to how sensitive these two groups are to particular relative price changes in the economy. Consistent with a notion forwarded in Coibion et al. (2020), households may be (over)reacting to spiking grocery store prices. Indeed, the upper tail of the Consumer Price Index price-change distribution from March through August 2020 is dominated by these salient consumer goods (see Fig. 9). Consistent with Binder (2020a), it may be the case that those most concerned by the coronavirus are those most vulnerable to spikes in food prices. Among respondents to the University of Michigan’s survey, the sharpest increase in inflation expectations has come from those individuals in the lower tercile of the income distribution. Given the substantial amount of disinflation in the overall CPI since the onset of the pandemic—slowing from a year-over-year growth rate of 2.3% in February to just 1.3% as of August—it certainly appears that households may be overreacting to surging grocery store prices.

Fig. 9.

Consumer price index component price change distribution. Note: We are reporting the annualized percent change over the time period spanning March to August 2020.

Bureau of Labor Statistics; authors’ calculations.

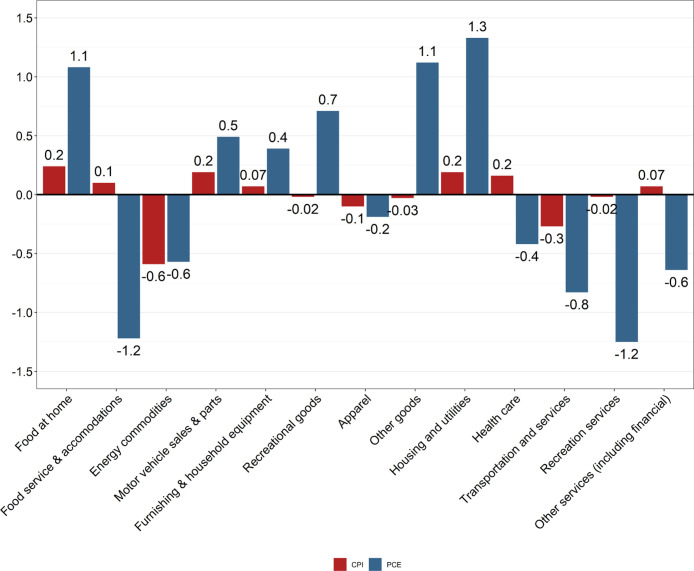

However, the COVID-19 pandemic has led to a dramatic shift in consumer preferences and expenditures—–replacing experiential spending at restaurants, tourist locations, and other service-based spending with durable goods and increase spending at the grocery store. Indeed, many of the very categories that have registered large price increases are those that are experiencing the largest changes in spending (see Fig. 10). Moreover, these changes in expenditures are not captured using the CPI’s “fixed-basket” weighting methodology. Unlike the CPI, the Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) Chained-Price Index does account for changes in spending patterns. The market-based variant of the PCE price index (the closest comparison to the CPI) has slowed by 40 basis points on a year-over-year basis, a smaller decline than the overall CPI. While this is not the central focus of the paper, the enormous impact that the pandemic has had on retail prices and consumer spending patterns has further highlighted the notion that households may be responding to salient relative price changes instead of “aggregate” inflation when asked to give their expectation about “prices in general” or “prices overall in the economy”.27

Fig. 10.

Pandemic impact on price indexes: changes in expenditure share/relative importance. Note: The data reported are in percentage points and span from December 2019 to August 2020.

Bureau of Labor Statistics; Bureau of Economic Analysis; authors’ calculations.

Firms, in contrast to households, appear to be responding to changes in their own unit costs rather than salient items in the consumer market basket. Appendix Figures 17 and 18 show that firms’ perceived changes in unit costs and unit cost expectations vary by industry group but, once aggregated, mirror changes in overall inflation and align well with the expectations of professional forecasters. One piece of evidence that corroborates the view that firms appear to be responding to changes in their own unit costs comes from an excellent decomposition of the ex food and energy (“core”) PCE price index into COVID-sensitive and insensitive sectors by Shapiro (2020). This decomposition reveals a sharp decline in COVID-sensitive inflation driven by sizeable declines in both price and quantity, consistent with a demand shock.

While it is not entirely clear what is driving common measures of household inflation expectations higher,28 it is apparent that firms, like professionals, have lowered their year-ahead inflation expectations consistent with a demand shock. We turn next to firms’ longer-run (five- to ten-year ahead) inflation expectations.

5. Long-run inflation expectations appear anchored for now

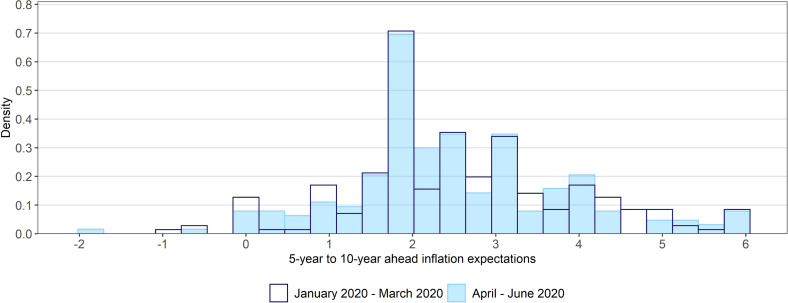

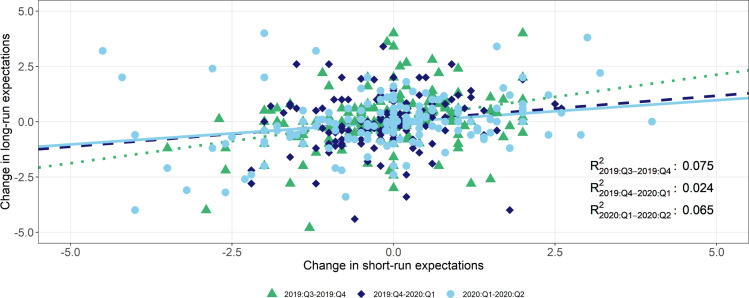

The pandemic has led firms, en masse, to lower their near-term inflation expectations in a manner consistent with a demand shock. However, as shown in Fig. 11 firms’ longer-run inflation expectations are little changed. On average, firms’ longer-run expectations ticked down by 0.1 percentage points from March 2020 to June 2020. There is little evidence of a large shift in the cross-sectional distribution during these early months of the pandemic. Perhaps more importantly, firms that lowered their inflation expectations between March 2020 and June 2020 do not appear to have ratcheted their longer-run expectations down in concert. Exploiting the panel structure of the BIE, Fig. 12 reveals no meaningful relationship over the pandemic period between a firm’s change in their short-run expectations and the change in their longer-run expectations. In the parlance of Fedspeak, businesses’ inflation expectations remain well anchored.

Fig. 11.

Distribution of firms’ long-run inflation expectations from January to June 2020. Notes: There were 228 and 204 responses in the pre-COVID and COVID time periods, respectively. The specific question is given in Appendix A.

Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta’s Business Inflation Expectations Survey, January and June 2020.

Fig. 12.

Changes in long-run and short-run inflation expectations. Notes: Both the -axis and -axis report the difference in percentage points. The solid fitted line belongs to the period December 2019 to March 2020 (pre-COVID) while the dashed fitted line belongs to the period from March to June 2020 (COVID). There were 192 respondents who completed both the September and December 2019 surveys, 188 respondents who completed the December 2019 and March 2020 surveys, and 173 respondents who completed the March and June 2020 surveys. The specific questions asked are given in Appendix A. The -axis is truncated at the [−5, 5] interval to more clearly show the variation between short- and long-run expectations. The fitted lines are computed separately as follows: . The slope of the fitted line for the period 2019:Q3 to 2019:Q4 is 0.40. The slope of the fitted line for 2019:Q4 to 2020:Q1 is 0.20. The slope of the fitted line for the period 2020:Q1 to 2020:Q2 is 0.23.

Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta’s Business Inflation Expectations Survey; September 2019, December 2019, March 2020, and June 2020.

6. Conclusion and short discussion

Since mid-March 2020, the coronavirus pandemic has had a profound impact on the U.S. as efforts to stem the spread of the virus led to shutdowns of large swaths of the economy. Business operations, sales activity, and (to a lesser extent) supply chains have all been disrupted. Our results suggest that firms, on net, have viewed this crisis largely as a demand rather than a supply shock. Responding to this demand shock, firms have lowered wages for a material share of their workforce, anticipate further wage cuts before the end of 2020, and anticipate lowering selling prices over the near-term.

Also, consistent with a demand shock, firms (like professional forecasters) lowered their one-year-ahead inflation expectations. Concurrently, inflation expectations of households have moved sharply higher, consistent with households’ keying off salient prices. Alternatively, households may be concerned with how vulnerable their nominal income is to the pandemic and their ability to manage in the face of sharp food price increases.

Our findings contribute to the rapidly emerging literature that examines direct effects of the pandemic on business ability to operate. Ramelli and Wagner (2020) show that firms’ stock prices were adversely affected when they were more dependent on international trade, global supply chains, and financial markets, with these effects becoming more pronounced by March. Alfaro, Chari, Greenland, and Schott (2020) and Fahlenbrach, Rageth, and Stulz (2020) find similar results. Bartik et al. (2020) find similar operating and liquidity concerns for small businesses that have been especially affected by enforced lockdowns yet employ nearly 50% of American workers. Dingel and Neiman (2020) also show that the effects may be heterogeneous, as the proportion of jobs that can still be done under lockdown measures varies by industry.

From a monetary policy standpoint, perhaps the only point of solace here is that longer-run inflation expectations of firms appear to be relatively well anchored. However, since mid-June, the path of the virus has accelerated and we have seen more and more hotspots emerging across the U.S. At the same time, the high-frequency data of Brave et al. (2019), Chetty et al. (2020), and other sources suggest that economic activity has flattened out and begun, in some cases, to show signs of slowing. Here our findings are, perhaps, less comforting to policymakers (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Expected number of months until business operations return to normal.

| Mean | Median | P10 | P25 | P75 | P90 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| April 2020 | 5.1 | 4.0 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 6.0 | 10.0 |

| July 2020 | 9.3 | 9.0 | 3.0 | 6.0 | 12.0 | 18.0 |

Notes: There were 220 observations in April 2020 and 198 in July 2020. The specific question is given in Appendix A.

Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta’s Business Inflation Expectations Survey, April and July 2020.

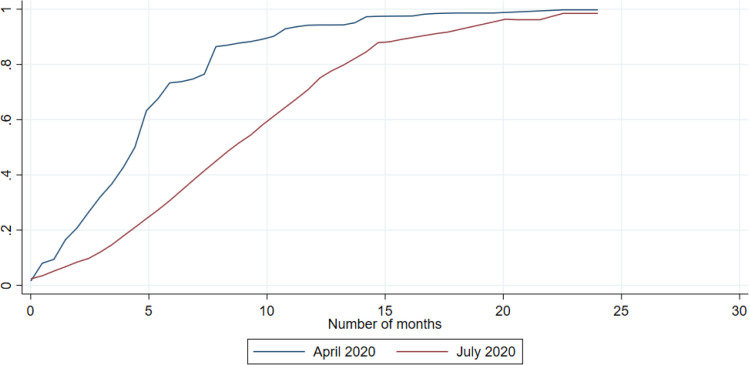

In April 2020 and again in July 2020, we asked firms to predict when the coronavirus would be behind them such that they could get back to normal operations. Back in April, firms gave us responses that aligned well with Bartik et al. (2020). At the time, half of the panel expected normal operations would resume by August 2020, and the most pessimistic firms (90th percentile) saw the coronavirus lasting until March 2021. However, firms have grown much more pessimistic since then. We repeated this question in July, and as Fig. 13 indicates, the typical firm in July expects the pandemic to continue to disrupt normal business operations until April 2021. About 10% of the firms see the crisis lasting until the beginning of 2022. Moreover, as shown in Fig. 14, firms that anticipate a longer duration of disruption from the coronavirus are also those that have indicated cutting a greater fraction of their employees’ wages. These findings suggest that firms’ expectations for the path of the virus could already be influencing their beliefs about the current and expected state of the labor market and, importantly, about future demand.

Fig. 13.

Cumulative share of the expected number of months until operations return to normal Notes: The responses are smoothed using a 1 degree polynomial smoother and are truncated at the 99th percentile. The specific question is given in Appendix A.

Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta’s Business Inflation Expectations Survey, April and July 2020.

Fig. 14.

Firms’ experienced and expected wage changes by expected duration of the pandemic. Notes: The low-skill expected and experienced values are based on 135 responses, 148 and 149 responses to the high-skill questions, and 300 for the “all” category. The specific questions asked are given in Appendix A.

Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta’s Business Inflation Expectations Survey, July and August 2020.

Should COVID-19 linger over the U.S. for another 12 months or longer, bringing with it lower demand, further shutdowns, and negative sales gaps, it could lead to lasting scars (see Portes (2020)). Firms may respond by lowering wages further, lowering inflation expectations further, or, perhaps, unanchoring longer-run expectations to the downside.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Acknowledgement: We are indebted to Nick Parker for his outstanding survey expertise and direction on question wording. We also thank Patrick Higgins, an associate editor, and two anonymous referees for helpful comments. We thank the participants at the International Institute of Forecasters (IIF) virtual workshop, titled “Economic Forecasting in Times of COVID-19” the 40th International Symposium on Forecasting and the 23rd Dynamic Econometrics conference, for their valuable comments and criticisms. We would also like to thank members of the Atlanta Fed’s research department for their comments on these findings through internal briefings. The views expressed here are the authors’ and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta or the Federal Reserve System.

Based on a new big data index developed by Brave, Butters, and Kelley (2019), Li and Sheng (2020) identify COVID-induced recession beginning in March 2020. Indeed, high-frequency data on small firm closings and activity from HomeBase (https://joinhomebase.com/blog/real-time-covid-19-data/), as well as high-frequency data from Opportunity Insights (https://tracktherecovery.org/) described in Chetty, Friedman, Hendren, and Stepner (2020), point to a sharp contraction in activity beginning in mid-March.

Lael Brainard. “Navigating Monetary Policy through the Fog of COVID”. July 14, 2020. Remarks given via webcast to the NABE. https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/brainard20200714a.htm.

Balleer, Link, Menkhoff, and Zorn (2020) find strikingly similar results to our work in a survey of German firms, finding that demand shortfalls far outweigh supply issues, leading these firms to anticipate cutting prices. These results open the possibility that the COVID-19 shock hit firms located in industrialized countries in a similar way.

Additional assurances of response quality and external validity such as survey response rates, tenure effects, the impact of question wording, responses to cognitive interviews, and the relationship of BIE responses to other national surveys can be found in Meyer, Parker, and Sheng (2021).

See Altig et al. (2020a) for an overview of the SBU survey and its properties. At the SBU’s inception, the survey elicited one-year-ahead unit-cost (inflation) expectations from firms using a question design that differed from that of the BIE in the choice to allow respondents to input both the support points and associated probabilities, rather than assigning probabilities to fixed bins. Meyer et al. (2021) evaluate the aggregate responses of the two surveys, finding that the two different methods yielded very similar expectations and uncertainty estimates.

Meyer et al. (2021) build on the survey work by Bryan, Meyer, and Parker (2015) to show: question wording matters a great deal to respondents’ interpretation of the concept of inflation; in this low inflation environment the U.S. has experienced since 2011 firms may be rationally ignorant of “prices in general” or “prices overall in the economy”; and that eliciting firms’ unit cost expectations yields a time-series inflation expectations measure that is highly correlated with professional forecasts, uncorrelated with household forecasts, and far superior in terms of forecasting ability than current household measures of inflation expectations.

See Armantier, Bruine de Bruin, van der Klaauw, Potter, Topa, and Zafar (2013) and Meyer, Parker, and Sheng (2021) for a deeper discussion of question wording (“prices in general/overall in the economy”) and expectations for aggregate inflation based on a price index (like the CPI or PCE). For evidence of the (lack of) importance firms place in aggregate inflation, see Candia et al. (2020) and Meyer et al. (2021).

Afrouzi (2020) provides evidence that firms in highly competitive environments tend to hold more well-formed “aggregate” inflation expectations.

Meyer et al. (2021) also provide evidence in the cross-section that individual firms’ unit cost expectations are correlated with their expectations for aggregate inflation based on a particular price index (the core CPI) and uncorrelated with their expectations for “prices overall in the economy” or “prices in general”.

Further evidence comes from Coibion, Gorodnichenko, and Kumar (2018). They find that managers devote few resources to collecting information about aggregate inflation measures and, instead, find information regarding aggregate inflation statistics useful for their shopping experiences.

See https://www.firm-expectations.org. The inclusion of the parenthetical “(for the Consumer Price Index)” in the question “What do you think will be the inflation rate (for the Consumer Price Index) over the next 12 months?” essentially clues firms in to the specific inflation concept the researchers wish to investigate. Incidentally, this is nearly identical to a special question posed to the BIE panel back in July 2015 (see https://www.frbatlanta.org/research/inflationproject/bie/special-questions?pub_year=2015). Importantly, in aggregate, this measure of firms’ inflation expectations falls precipitously following the onset of the pandemic, mimicking the behavior of BIE inflation expectations and running counter to the sharp increase in households’ “prices in general” expectations.

Further information can be found here: https://www.frbatlanta.org/research/inflationproject/bie.

While there are some clear examples of costs incurred by firms due to the pandemic (i.e., personal protective equipment and plexiglass barriers), it is not clear that firms impacted by these cost increases view them as higher marginal or fixed costs. Conversely, there were offsetting cost decreases for many firms (lower energy prices, movements to a work-from-home posture, and dramatically lower travel costs as external meetings moved online). As we show below, many firms experienced lower labor costs.

See Chetty et al. (2020) or visit tracktherecovery.org; Homebase data at https://joinhomebase.com/blog/an-update-on-small-business-as-covid-19-cases-rise/; Cajner et al. (2020); and Barrero, Bloom, and Davis (2020).

In April 2020, we asked about disruption to sales activity and business operations. In May 2020, we asked about disruption to sales activity, supply chains, and staffing levels.

Firms that indicated experiencing stronger-than-normal sales were disproportionately in industries that correspond to the strong shifts in demand that we have seen in Census and high-frequency data (grocers, construction firms, transportation and warehousing, non-durable goods manufacturers, etc.).

For details: https://www.richmondfed.org/research/national_economy/cfo_survey/research_and_commentary. When the topic of a survey question is wide-ranging, the open-text approach (evaluated using text analysis) tends to be less biasing than having firms choose from a set of response options.

See Appendix A for the specific wording to these and all survey questions used in this paper.

This phenomenon is also unusual in the history of the BIE. While not directly comparable to our current results, in September 2018 we elicited firms’ year-ahead probabilistic wage growth expectations. Only one respondent at the time indicated the potential for negative wage growth in a “lowest-case” expectation. See the BIE’s special question archive for 2018 (https://www.frbatlanta.org/research/inflationproject/bie/special-questions.aspx?pub_year=2018) for more details.

The BLS very recently released the results of its 2020 Business Response Survey (BRS), which finds that 56% of establishments (approximately 4.7 million) experienced a decrease in demand during the pandemic (through September 2020), while only 36% of establishments (or 3.1 million) experienced a shortage of supplies or inputs (for details, see: https://www.bls.gov/brs/2020-results.htm).

Many view the beginning of the COVID pandemic as occurring on March 13, 2020 and corresponding with shelter-in-place orders happening across the country. The March BIE was in the field from March 2–6, prior to this period. Moreover, a special question posed to the panel in March asked if the recent coronavirus outbreak had an effect on a number of aspects of business activity. The results indicated that, apart from a few firms, the majority of the business community had yet to be impacted.

For background on the SCE, see Armantier et al. (2013).

They note, “asking specifically about inflation, because asking about prices might induce individuals to think about specific items whose prices they recall rather than about overall inflation”.

It should be noted that when comparing aggregated expectations of households, firms, and professional forecasters, each group is responding to different but seemingly related economic concepts. For households in particular, the differences in their expectations for “prices in general” and the growth rate in the Consumer Price Index (CPI) have been often documented at least as far back as Bryan and Venkatu (2001).

Kamdar (2019) finds that sentiment is a key driver of household macro-expectations, and that many households equate “bad times” with “high inflation”. See also Binder (2020b).

Supplementary material related to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijforecast.2021.02.009.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary material related to this article.

Online Appendix: The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on business expectations by Meyer, Prescott and Sheng.

References

- Abo-Zaid, S., & Sheng, X. S. 2020. Health shocks in a general equilibrium model. Working paper.

- Afrouzi, H. 2020. Strategic inattention, inflation dynamics, and the non-neutrality of money. CESifo working paper No. 8218.

- Alfaro, L., Chari, A., Greenland, A., & Schott, P. 2020. Aggregate and firm-level stock returns during pandemics in real time. NBER working paper No. 26950.

- Altig D., Barrero J.M., Bloom N., Davis S.J., Meyer B.H., Mihaylov E., et al. American firms foresee a huge negative impact of the coronavirus,” macroblog. Fed. Reserve Bank Atlanta. 2020 23 March. [Google Scholar]

- Altig D., Barrero J.M., Bloom N., Davis S.J., Meyer B.H., Parker N. Surveying business uncertainty. J. Econometrics. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jeconom.2020.03.021. in press. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Armantier O., Bruine de Bruin W., van der Klaauw W., Potter S., Topa G., Zafar B. Measuring inflation expectations. Annu. Rev. Econ. 2013;5:273–301. [Google Scholar]

- Armantier O., van der Klaauw W., Topa G., Zafar B. The price is right: Updating inflation expectations in a randomized price information experiment. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2016;98(3):503–523. [Google Scholar]

- Armantier, O., Koşar, G., Pomerantz, R., Skandalis, D., Smith, K., & Topa, G., et al. 2020. How economic crises affect inflation beliefs: evidence from the COVID-19 pandemic. Federal Reserve Bank of New York staff report No. 949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Balleer A., Link S., Menkhoff M., Zorn P. Institute of Labor Economics DP No. 13568. 2020. Demand or supply? Price adjustment during the COVID-19 pandemic. [Google Scholar]

- Barrero J.M., Bloom N., Davis S.J. COVID-19 is also a reallocation shock. Forthcoming in Brookings Papers on Economic Activity. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- Bartik, A. W., Bertrand, M., Cullen, Z. B., Glaeser, E. L., Luca, M., & Stanton, C. 2020. The impact of COVID-19 on small business outcomes and expectations. Harvard Business School working paper 20–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Bils M., Klenlow P. Some evidence on the importance of sticky prices. J. Political Econ. 2004;112:947–985. [Google Scholar]

- Binder C. Coronavirus fears and macroeconomic expectations. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2020;102(4):721–730. [Google Scholar]

- Binder C. Long-run inflation expectations in the shrinking upper tail. Economics Letters. 2020;186 [Google Scholar]

- Bloom N., Fletcher R., Yeh E. 2020. Forthcoming work using the stanford-stripe survey. For slides see: https://siepr.stanford.edu/sites/default/files/Nick%20Bloom%20slides.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Brave S., Butters A., Kelley D. A new “big data” index of U.S. economic activity. Fed. Reserve Bank Chic. Econ. Perspect. 2019;43(1):1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Brinca, P., Duarte, J. B., & Faria-e Castro, M. 2020. Measuring labor supply and demand shocks during COVID-19. St. Louis Federal Reserve working paper 2020–11D. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Bryan, M., Meyer, B., & Parker, N. 2015. The inflation expectations of firms: what do they look like, are they accurate, and do they matter? Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta working paper, 2014–27a.

- Bryan M.F., Venkatu G. The curiously different inflation perspectives of men and women. Econ. Comment. Fed. Reserve Bank Cleveland. 2001 [Google Scholar]

- Cajner, T., Crane, L. D., Decker, R. A., Grigsby, J., Hamins-Puertolas, A., & Hurst, E., et al. 2020. The US labor market during the beginning of the pandemic recession. NBER working paper No. 27159.

- Candia, B., Coibion, O., & Gorodnichenko, Y. 2020. Communication and the beliefs of economic agents. In Conference draft for Kansas City Federal Reserve’s Jackson Hole Symposium. 2020.

- Chetty R., Friedman J.N., Hendren N., Stepner M., the Opportunity Insights Team . 2020. How did COVID-19 and stabilization policies affect spending and employment? A new real-time economic tracker based on private sector data. Opportunityinsights.org. [Google Scholar]

- Cochrane J. Economics in the time of COVID-19. CEPR Press; 2020. Coronavirus monetary policy; pp. 105–108. a VoxEU.org eBook. [Google Scholar]

- Coibion O., Gorodnichenko Y., Kumar S. How do firms form their expectations? New survey evidence. Am. Econ. Rev. 2018;108(9):2671–2713. [Google Scholar]

- Coibion, O., Gorodnichenko, Y., & Weber, M. 2020. Does policy communication during COVID-19 Work? Institute of Labor Economics DP No. 13355.

- Dietrich, A., Kuester, K., Muller, G., & Schoenle, R. 2020. News and uncertainty about COVID-19: survey evidence and short-run economic impact. Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland working Paper No. 20–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Dingel, J., & Neiman, B. 2020. How many jobs can be done at home? NBER working paper No. 26948.

- Fahlenbrach, R., Rageth, K., & Stulz, R. M. 2020. How valuable is financial flexibility when revenue stops? Evidence from the COVID-19 crisis. NBER working paper No. 27106.

- Gagnon E., Lopez-Salido D. Small price responses to large demand shocks. J. Eur. Econ. Assoc. 2020;18(2):792–828. [Google Scholar]

- Guerrieri, V., Lorenzoni, G., Straub, L., & Werning, I. 2020. Macroeconomic implications of COVID-19: can negative supply shocks cause demand shortages? NBER working paper No. 26918.

- Hassan, T. A., Hollander, S., van Lent, L., & Tahoun, A. 2020. Firm-level exposure to epidemic diseases: Covid-19, SARS, and H1N1. Working paper.

- Kahneman D., Knetsch J.L., Thaler R. Fairness as a constraint on profit seeking: Entitlements in the market. Am. Econ. Rev. 1986;76(4):728–741. [Google Scholar]

- Kamdar, R. 2019. The inattentive consumer: Sentiment and expectations. Working paper.

- Kharas H., Triggs A. The triple economic shock of COVID-19 and priorities for an emergency G-20 leaders meeting. Brookings Blog. 2020:2020. [Google Scholar]

- Klenow P., Kryvtsov O. State-dependent or time-dependent pricing: Does it matter for recent U.S. inflation? Q. J. Econ. 2008;123:863–904. [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Sheng X.S. Dating COVID-induced recession in the U.S. Applied Economics Letters. 2020 doi: 10.1080/13504851.2020.1852163. in press. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Manski C.F. Measuring expectations. Econometrica. 2004;72(5):1329–1376. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer B.H., McCord R., Waddell S.R. The CFO survey and firms’ expectations for the path forward. the CFO survey. Res. Comment. Note. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, B. H., Parker, N., & Sheng, X. S. 2021. Unit Cost Expectations and Uncertainty: Firms’ Perspectives on Inflation. Forthcoming Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta working paper.

- Portes J. 2020. The lasting scars of the COVID-19 crisis: Channels and impacts. VoxEu.org. [Google Scholar]

- Ramelli S., Wagner A.F. Swiss Finance Institute Research Paper; 2020. Feverish stock price reactions to COVID-19. [Google Scholar]

- Sbordone A.M. Do expected future marginal costs drive inflation dynamics? Journal of Monetary Economics. 2005;52:1183–1197. [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro, A. 2020. A simple framework to monitor inflation. Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco working paper 2020-29.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Online Appendix: The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on business expectations by Meyer, Prescott and Sheng.