Abstract

Like many other countries, the economy and society of Japan have been deeply affected by the Covid-19 outbreak, and the fishery sector is no exception. This study takes an interdisciplinary approach to analyze the economic and social impacts of the pandemic on Japanese fisheries, gauging the extent and nature of the damages incurred from Covid-19 while helping to provide tailored post-recovery recommendations for the industry. Using results from an online survey questionnaire (N = 429) and compiling additional economic information from public sources, this study revealed the overwhelmingly negative changes in sales figures and overall financial security that survey participants experienced when compared to a year earlier. High-value and fresh fish species were also significantly affected in 2020 across Japan, in line with similar trends across the developed world. Aquaculture businesses were shown to be more vulnerable to the spread of Covid-19 than small-scale fishing operations, which tend to be more diverse and flexible. Bonding social capital was also shown to be important for mutual help and human well-being, especially among small-scale fishers. This “customary nature” of Japanese fisheries, at the same time, can be seen as a barrier to the transformation of the industry. Given these results, several policy implications are discussed to help fisheries stakeholders and their communities build back better from the Covid-19 pandemic.

Keywords: Covid-19, Japanese fisheries, Social capital, Human well-being, Building better back

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

The first case of COVID-19 (infection by the SARS-CoV-2 respiratory virus) in Japan was reported by the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare on January 16, 2020. The 100th and 1000th cases were then reported one month (February 21) and two months (March 21) later, respectively. The Government of Japan issued a State of Emergency on April 7, which encouraged people in seven large cities, including Tokyo’s metropolis, to stay at home and refrain from inter-prefectural travels and non-essential outings. The State of Emergency was later expanded to all 47 prefectures. Even though the total cumulative cases in the country have remained relatively low (as of January 14, 2021), with Japan ranking 30th in the world according to WHO (https://covid19.who.int/table), daily cases have been dramatically increasing since November 2020, which marked the onset of the third wave of Covid-19 in Japan ( Fig. 1). Since then, the Japanese Government has issued a second State of Emergency on January 7, 2021.

Fig. 1.

Infection trend and major events related to Covid-19 in Japan during the year 2020 (modified from: https://github.com/CSSEGISandData/COVID-19).

Similarly to other countries, the economy and society of Japan have been significantly affected by the Covid-19 outbreak, and the fishery sector is no exception [1], [2]. Japan is known as one of the most important fishing nations in the world, especially in terms of seafood production (ranked 8th in marine capture production [3]) and consumption habits, with seafood being one of the most important sources of animal protein intake for Japanese people [4]. Several large Japanese fishing corporations were identified as the most powerful seafood suppliers in the world [5]. And even though large-scale corporations is one aspect of Japanese fisheries, it has been shown that coastal small-scale fisheries (hereinafter SSF) are more important from an economic, social and cultural standpoint, notably regarding their contribution to total production volumes and the sheer number of employees and coastal communities (beyond 6000) they sustain across the archipelago [4], [6], [7], [8].

Given the features of Japanese fisheries and associated fishing communities, this interdisciplinary study aims to offer empirical evidence on how they have been impacted by Covid-19 from an economic and social perspective. This paper will also discuss the policy implications of the outbreak and the steps needed in the recovery process. No peer-reviewed study has yet investigated the Covid-19 impacts on Japanese fisheries and coastal communities.

2. Methodology

Using a survey questionnaire and open data sources, this study examines the economic and social impacts that the coronavirus outbreak had on the Japanese fishing industry during the first year of the pandemic in 2020. The economic analysis is twofold, it first reviews the perceived effects of Covid-19 on the economic security of the survey respondents, before cross-checking them with official economic data sources. To investigate the social dimension of the impact of Covid-19, this study applies a (1) social capital, (2) human well-being and (3) free-answer analysis.

2.1. Data collection: survey design and distribution

This study was carried out by a transdisciplinary group consisting of social scientists, economists, ecologists, seafood business consultants and fishers, formed right after the first State of Emergency. To collect data from all over Japan, the group decided to create and conduct the survey online, with the help of SurveyMonkey (https://www.surveymonkey.com/), an online questionnaire tool. From the beginning of the research design process, not only scientists but also fishery sector participants were brought together to collaborate and bring diverse insights and perspectives to better understand the “real” challenges associated with Covid-19 and to enhance the prospect of Japanese fisheries.

The survey questionnaire targeted individuals working in both fishery (coastal, offshore and aquaculture) and fishery-related businesses (e.g. seafood manufacturing, wholesale, fishery cooperative employees, etc.). When distributing the questionnaire, both formal and informal institutions related to fisheries and fishery sciences were used as intermediaries, including: (1) fisheries-related academic societies and research institutions (e.g. The Japanese Society of Fisheries Science, Japanese Association for Coastal Zone Studies, The Japanese Society of Fisheries Oceanography, Japanese Society of Fisheries Economics and Japan Fisheries Research and Education Agency), (2) fisheries-related stakeholder organizations, such as JF Zengyoren (the representative of small-scale coastal fishers), the Japan Fisheries Association (the representative of all fisheries sectors), the Japan Trout Farmers Association and the Marine Eco-Label Japan Council, (3) fisheries-related media outlets (e.g. The Suisan-Keizai Daily News and The Minato Daily News) as well as (4) personal and informal networks coming from members of this study group. Through these channels, respondents were invited to join the study and take up the survey. The online survey ran from May 29 to October 18, 2020, and because it was hard for some participants located in rural areas to answer the online survey form, some samples were also collected offline through FAX, phone-based or face-to-face interviews. In such areas, several researchers within and outside the study group cooperated with offline data collection officers. However, for reliability and consistency purposes, only data collected via online forms (N = 429) were used for this study. And due to the online survey design allowing respondents to skip questions if they don’t want to or don’t feel comfortable answering, not all items have the same sample size (see Table A.1 for an overview of the questionnaire items).

2.2. Baseline economic analysis: fisheries and trade data

While the assessment of subjective or perceived economic effects from Covid-19 was performed on the survey data described above, baseline economic information on fisheries landings, unit price and trade was compiled from two different public sources. Monthly data on species- and product-specific landings (tons) and unit price (JPY/kg) were extracted and compiled from the fisheries distribution survey of the Japan Fisheries Information Service Center (JAFIC).1 The JAFIC survey includes a total of 24 different fish species, of which 10 present detailed information broken down by product type (i.e. frozen and fresh). All combinations of fish species and product types available from the JAFIC survey are used in this analysis. Results were aggregated across important fish markets in Japan, and the time period analyzed extends from January 2015 to November 2020 (last accessed on January 12, 2021). In addition, each species was assigned a particular value or grade based on historical unit price data (2015–2019). Specifically, by examining the monthly time series of each species’ unit price, species were categorized as low-value if their monthly weighted price average was below 100 JPY/kg, high-value if it was above 700 JPY/kg and medium-value if the mean weighted price fell in between both extremes. Table A.2 shows the list of species-product associations and their summary statistics.

To measure the impacts of the Covid-19 outbreak on Japanese fisheries, year-on-year changes between each month (from January to November) in 2019 and 2020 were computed and normalized accordingly. Accounting for potentially unusual fisheries trends in 2019 that might not fully reflect the pre-covid dynamics of Japanese fisheries, monthly data in 2020 was also compared to a 5-years monthly average (2015–2019).

When investigating trends in the trade of fish commodities derived from previously compiled species, data on the quantity and value of exports and imports of live,2 fresh and frozen fish products were obtained from “e-stat”, a portal site for Japanese government statistics (https://www.e-stat.go.jp/en). Disaggregated per trading country, year (2019–2020) and month (January to November), a total of 38 different fish commodities from both wild fisheries and aquaculture were identified and matched to 15 species from JAFIC. Year-on-year changes in exports and imports of fish commodities were also examined between 2019 and 2020. All data analyses pertaining to the economic aspect of this study were executed using the statistical software R (version 4.0.2) [9].

2.3. Social capital

To investigate further how Japanese fisheries have reacted to the Covid-19 outbreak, this paper looks at social capital, a concept defined as ‘features of social organization such as networks, norms and social trust that facilitate coordination and cooperation for mutual benefit’ [10]. Many studies have employed this concept, and it has recently gained traction within the disaster literature [11], [12], [13]. Inspired by these studies, closed-ended questions aimed at capturing social capital were designed for the survey. One such question notably asked to select out of 15 possible options, up to three key stakeholders that respondents felt were the most helpful during the Covid-19 outbreak. Some of these options included national, prefectural and municipal agencies, commerce and industry organizations, financial institutions, fisheries cooperatives, corporate partners and clients, NGOs and NPOs, friends and acquaintances, local community neighbors and family members, among others. The structure of this question followed the method used in Clay et al. [13], which was thought to be the most suitable and feasible one for that context. Answers were then counted for each option to identify which organizations and/or groups were the most helpful during the pandemic.

2.4. Human well-being

The pandemic and its restrictions have had a substantial impact on our societies, not only economically, but also mentally and physically, affecting life quality and human well-being [14]. Assessing subjective measures of the impacts of Covid-19 is a meaningful attempt to move beyond sole consideration of socioeconomic factors. Physical and mental health are important components of human well-being and are particularly important to fishing communities because of the physically and mentally demanding nature of their work and lifestyle [15], [16]. The concept of human well-being incorporates many aspects of individuals and communities’ quality of life, including ‘basic materials for a good life’, ‘health’, ‘good social relations’, ‘security’, and ‘freedom of choice and action’ [17].

To examine how human well-being has been affected by the Covid-19 outbreak, survey participants were asked to rate their level of satisfaction with different aspects of their daily life before and during the pandemic. Some characteristics of these well-being centered questions were informed by a multi-dimensional conceptualization of human well-being, which was applied in former studies [18], [19]. The specific aspects of this concept included in the survey were related to personal satisfaction with physical and mental health, food and essential needs security, social capital in the local community, a sense of adaptive capacity, cultural opportunities, a sense of community belonging, the ability to continue cultural practices and trust in regional, national and local organizations. Each question was scored by the respondents based on their subjective satisfaction level for each of the 12 items presented, which followed a five-point “Likert-type” scale: 5 =very satisfied, 4 =somewhat satisfied, 3 =neither satisfied or dissatisfied, 2 =dissatisfied, and 1 =very dissatisfied.

2.5. Opinions about Japanese fisheries before and during Covid-19

Open-ended questions asking respondents’ opinions about Japanese fisheries were also included, so as to gather insights on how this outbreak would change Japanese fisheries and associated coastal communities. These questions are also helpful in determining what policies and other meaningful efforts could be proposed to mitigate the negative consequences of the pandemic on the fishing sector. A mixed method of qualitative and quantitative content analysis on text data obtained by free answer questions was applied. Qualitative content analysis, such as the formation of qualitative categories [20], is an appropriate approach to gain insights into text data through a comprehensive search of the entire dataset [21]. This study also performed a quantitative content analysis using the software KH coder (https://khcoder.net/en/), thus getting a more objective categorization without being biased by the researchers’ perspectives [22]. Specifically, two close-ended questions were first asked about how satisfied survey respondents were with Japanese fisheries before and during the Covid-19 outbreak. A five-point Likert-type scale was again applied. Open-ended questions followed these guiding questions, asking why respondents selected a certain satisfaction level, and their opinion on post-covid recommendations for the industry.

3. Results

3.1. Stakeholder communication

As soon as the preliminary results of the survey were made available, the study group released a public-friendly two-pager infographic on July 27, 2020 (N = 350) (Fig. A.1). This action-oriented approach was necessary to promote and distribute key scientific results in an accessible and timely manner. This two-pager infographic gained the attention of multiple stakeholders through articles in several newspapers.3 For instance, the Japan Fisheries Association, which is the largest fishery stakeholder group representing all fisheries sectors in Japan, read and introduced the two-pager in meetings of the ruling political party (Liberal Democratic Party), to notably explain and share the impacts of Covid-19 on Japan’s fishing industry.

3.2. Survey demographics

Among the 429 surveyed individuals, around a third is working in fisheries (coastal or offshore) and aquaculture businesses, with more than half of aquaculture businesses being of corporate nature (53.6%), while small-scale coastal fishing enterprises are mainly run by families (75.4%). The remaining participants are involved in fishing-related industries such as seafood processing, wholesale and retail and food services, among others ( Figs. 2 a, b). The most represented sub-sectors include coastal fishing, aquaculture, seafood wholesale, fisheries cooperatives4 and seafood products manufacturing (Fig. 2 b). The geographical scope of the survey covers the entire archipelago, with roughly half of respondents located in the Kanto (including the greater Tokyo area) and northern regions of Japan, with the latter encompassing both Tohoku and the northernmost island of Hokkaido (Fig. 2 c). The median age of the interviewees is 48 years old5 and around 86% of them are men, with a majority residing in their hometown (Figs. A.2, A.3).

Fig. 2.

Distribution of survey respondents by (a) fishing sector (fisheries and aquaculture on one hand and fishing-related industries on the other), (b) sub-sector and (c) region across Japan.

3.3. Perceived economic losses

When asked about the impact of Covid-19 on their businesses, 259 interviewees indicated the degree of change (%) in sales they experienced during the survey period in 2020, relative to the same period in 2019.6 Results across all respondents demonstrate the overwhelmingly negative effect that the coronavirus outbreak has had on the sales figures and economic security of the Japanese fishing industry, as more than 75% of respondents reported moderate to strong decreases in total annual sales ( Fig. 3 a). When disaggregated per sector, fishers and fish farmers reported a greater proportion of strong year-on-year losses (i.e. negative changes in total annual sales greater than 50%) when compared to post-harvest and downstream industries (Fig. 3 a). Within the fisheries and aquaculture sector, corporate businesses appeared slightly more vulnerable to the spread of Covid-19 than family-run enterprises (Fig. 3 b). The aquaculture sub-sector was particularly affected, as no one reported an increase in sales in 2020 and almost half of them experienced year-on-year changes greater than 50%, while coastal fishing was one of the least impacted sub-sector during the coronavirus outbreak (Fig. 3 c). In addition, having years of experience running a fishing or aquaculture business did not provide any buffer against the pandemic shock (Fig. A.4).

Fig. 3.

Changes in total annual sales (%) attributed to the coronavirus outbreak, disaggregated per (a) sector (n = 259), (b) business type (n = 83), and (c) sub-sector (n = 151). The two business types displayed in (b) are only relevant to the fisheries & aquaculture sector. Strong changes in total annual sales are associated with changes greater than 50% when compared to the previous year, while moderate changes account for changes between 0% and 50%.

Prior to the Covid-19 outbreak, customary wholesale markets run by fishery cooperatives were the most dominant sales channels for fish producers, contributing to an average of more than 60% of total seafood sales in Japan (Fig. A.5). When questioned about the perceived driving factors behind the declines in total annual sales, individuals working in fisheries and aquaculture reported that changes in the volume of fish sold, number of promotional events and availability of sales outlets were the most influential ones ( Fig. 4 a). The latter incentivized some businesses to seek alternative modes of distribution, leading to increases in direct online sales to consumers (Fig. A.6). Changes in fish prices were also contributing significantly to the economic losses experienced by primary producers, although a quarter of respondents expressed no real concerns on that matter (Fig. 4 a). As for respondents working in post-harvest, retail and food service businesses, changes in the unit price of seafood products, number of promotional events and future market prospects were by far the most detrimental factors to their financial security during the coronavirus outbreak (Fig. 4 b). Changes in the volume of fish handled did not weigh as much as for producers, while variations in quantities of imported seafood gathered mixed, though still mainly negative reactions (Fig. 4 b).

Fig. 4.

Relative contribution of key factors in the decline of total annual sales attributed to the coronavirus outbreak, as reported from people working in (a) fisheries and aquaculture (n = 83) and in (b) fishing-related industries (n = 176). The degree of change translates the perception of each respondent, and only interviewees who reported negative changes (moderate or strong) in total annual sales are included in that figure.

3.4. Baseline economic impacts

Aggregating monthly landings and unit price data across all compiled species (Table A.1.) (regardless of the product type and fish grade) shows an inverse relationship between year-over-year changes in average landings and in mean unit price of fish ( Fig. 5). This is especially true when comparing 2020 with the 5-years average (2015–2019) and between the months of February and July, a period during which the first two waves of Covid-19 occurred. Some of the largest changes happened during the months of June and July 2020, which recorded the highest increases in landings from the Japanese fleet when compared to 2019 and to the 5-years average (Fig. 5 a), while fish prices experienced their biggest recorded drop (−30%). In addition, at the onset of the third and largest Covid-19 wave in November, landings decreased by almost 30% when compared to the 5-years average, while fish prices saw a 20% associated rise, the largest recorded in 2020. Overall, while fish landings appear to have mainly increased during the heart of the pandemic, fish prices have suffered consistent decreases when compared to both 2019 and the 5-years average.

Fig. 5.

Percentage change in mean (a) monthly landings (tons) and (b) unit price (JPY/kg) across all species and products, and compared to the same months in 2019 and with regard to the 5-years average (2015–2019). The months highlighted in red delimit the peaks of the first, second and third waves of coronavirus in Japan.

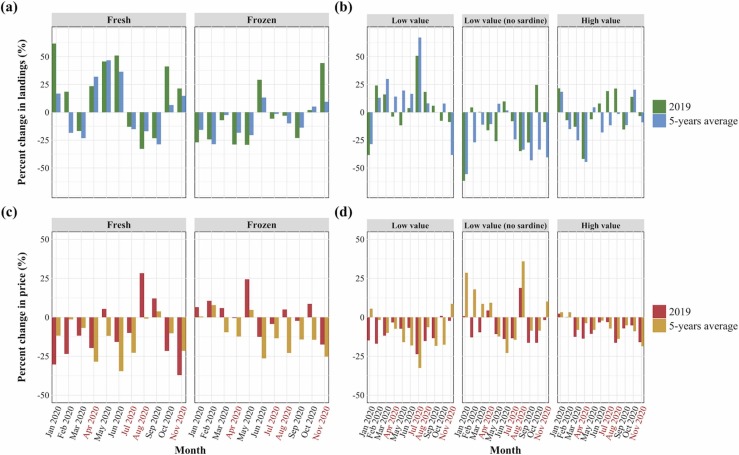

At a more granular level, fresh fish products showed greater variations in landings and unit price than frozen fish ( Figs. 6 a,c). Up to a 50% increase in landings of fresh fish was reported between the two waves of Covid-19 (April to June), before reversing during the summer (Fig. 6 a). As for its unit price, substantial declines can be observed throughout the entire year, except in August and September ( Fig. 6 c). Fish destined to be processed as frozen products were affected to a lesser degree, but both their landings and unit price experienced mainly negative changes throughout 2020 (Figs. 6 a, 6 c).

Fig. 6.

Percentage change in mean monthly landings (tons) and unit price (JPY/kg), disaggregated by (a,c) product type (frozen and fresh) and (b,d) fish grade or value, and compared to the same months in 2019 and with regard to the 5-years average (2015–2019). The months highlighted in red delimit the peaks of the first, second and third waves of coronavirus in Japan.

When broken down by fish grade (keeping only low and high-value species), two important trends can be detected (Figs. 6 b, 6 d). First, although year-on-year changes in landings of low value fish were all positive from February to October, with a strong peak in July (> 50%), the majority of that growth was attributed to one species, the Japanese sardine (Sardinops melanostictus) (Fig. 6 b). And when landings of Japanese sardine are not accounted for, the figure for low value species changes drastically, showing negative year-on-year changes for most months in 2020. Prices of low value fish have experienced non-negligible volatility when excluding the influence of Japanese sardine, with substantial decreases occurring between the first two waves of Covid-19 (Fig. 6 d).

Second, year-on-year prices of high-value species (e.g. bigeye tuna, snow crab, sea bream, etc.) have experienced a consistent decline from March to November 2020, with stronger peaks aligned with the second and third waves of Covid19 (Fig. 6 d). The fall in unit prices of high value species in March and April 2020 was also associated with large drops in volumes of landed fish (Figs. 6 b, 6 d), before the latter reversed slightly during the summer, with non-negligible increases in landings in July and August when compared to the previous year (Fig. 6 b). But regardless of the changing dynamics in the landings of these high-prized species in 2020, their unit prices kept being lower than their pre-covid averages.

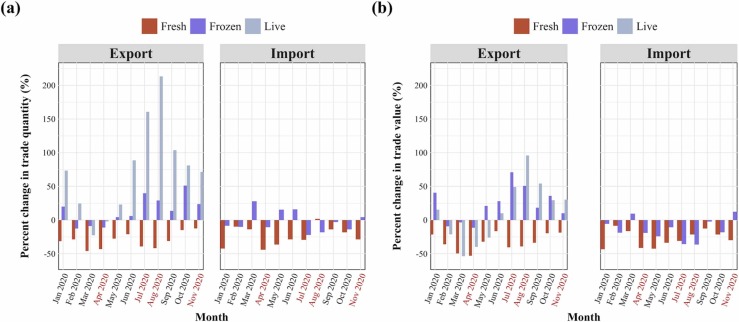

As for trade dynamics in fish commodities pertaining to the same species as above, Fig. 7 depicts overall decreases in both the quantity and value of exports and imports during the first two quarters of 2020. Imports of frozen and fresh fish products remained below their 2019 averages throughout most of the year, with fresh products suffering larger declines in imported quantities and associated values (Figs. 7 a, 7 b). While exports of fresh fish have also been negatively affected throughout 2020, frozen and especially live fish products saw substantial growth from June onwards, with export quantities of live fish increasing by more than 100% for 3 straight months (July-September) (Fig. 7 a). These exports were exclusively composed of live sea breams (Pagrus major) destined for the Republic of Korea (Fig. A.8).

Fig. 7.

Year-over-year (2019–2020) percentage changes (%) in the mean (a) quantity (kg) and (b) value (JPY1000) of monthly Japanese exports and imports, disaggregated per product type or commodity. The months highlighted in red delimit the peaks of the first, second and third waves of coronavirus in Japan.

Regarding the increase in export quantities and values of frozen fish products, evidence suggests that an unusual rise in landings of albacore tuna (Thunnus alalunga) from April to July 2020 (Fig. A.9) led to a proportional increase in both the quantity and value of its exports (Fig. A.10). Exports of albacore tuna during the summer were for the most part related to frozen products bound for Southeast Asia, namely Thailand and Vietnam (Fig. A.11).

3.5. Social capital

This section reveals the answers to questions related to social capital, specifically which organizations and/or groups of individuals were perceived to be the most helpful during Covid-19 (three top choices), with regard to both the respondents’ operating business and their daily life concerns.

Among fisheries and aquaculture businesses (N = 174), while friends and acquaintances, national agencies and fishery cooperatives were felt to be the most helpful for family operators (SSF), financial institutions as well as prefectural and national agencies were seen as the most supportive ones for corporate operators (Fig. A.14). As for support towards fishing-related businesses (N = 383), corporate partners and clients pre-Covid, national agencies and financial institutions were perceived as the most helpful by participants.

With regard to daily life support during these unprecedented times (N = 417), family, national agencies and friends and acquaintances were of greater help to small-scale fishers and fish farmers, while their corporate and larger-scale counterparts found most of their support from financial institutions, fisheries cooperatives as well as national and prefectural agencies (Fig. A.14). Participants involved in fishing-related businesses selected national agencies, corporate partners and clients pre-Covid, as well as friends and acquaintances as the most helpful ones for their daily life concerns.

A notable observation is that certain kinds of informal social relations, or bonding social capital [13], such as friends and acquaintances for SSF, and corporate partners and clients pre-Covid for fishing-related businesses, were perceived as much more helpful than official and formal agencies. One exception is corporate operators in fisheries and aquaculture, who rated financial institutions the highest (Fig. A.14).

3.6. Human well-being

Concerning the human well-being dimension of the survey, the average satisfaction scores associated with leisure and cultural opportunities as well as trust in national public agencies were the lowest recorded. In addition, the average satisfaction score for “relationship with community members and customers” was greater in family operations of the fisheries and aquaculture sector (A) than among fishing-related businesses (C) (p < 0.10). Another notable observation is the satisfaction level with “trust in local private agencies/organizations”, as (A) showed significantly higher scores than (C) (p < 0.01) ( Table 1).

Table 1.

Mean and standard deviation (SD) of a five-point satisfaction score for 12 items of human well-being, and disaggregated by sector and operating business.

| Sectors (operating business) |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Items of human well-being | A: Fisheries & aquaculture (family operations) |

B: Fisheries & aquaculture (company operations) |

C: Fishing-related businesses |

||||||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | p | |||||

| 1. Procurement of necessary food items | 3.67 | 1.06 | 3.97 | 0.83 | 3.69 | 1.07 | |||||

| 2. Procurement of daily essentials | 3.67 | 0.98 | 3.94 | 0.85 | 3.58 | 1.03 | |||||

| 3. Personal and family’s physical health | 3.82 | 1.23 | 3.74 | 1.08 | 3.60 | 1.00 | |||||

| 4. Personal and family’s mental health | 3.44 | 1.17 | 3.12 | 1.07 | 3.26 | 1.10 | |||||

| 5. Relationship with community members, customers, etc | 3.51 | 1.21 | 3.32 | 1.12 | 3.09 | 0.98 | † | A > C | |||

| 6. Flexibility to deal with the unforeseeable | 2.92 | 1.01 | 2.62 | 1.10 | 2.83 | 0.96 | |||||

| 7. Opportunities to enjoy leisure and cultural activities | 2.31 | 1.36 | 2.26 | 1.05 | 2.24 | 1.04 | |||||

| 8. Pride in being a member of the community | 3.41 | 1.23 | 3.38 | 1.07 | 3.10 | 0.80 | |||||

| 9. Linking a diversity of knowledge and customs (local ecological knowledge, traditional culture, etc) | 3.08 | 1.29 | 3.06 | 1.15 | 2.84 | 0.82 | |||||

| 10. Trust in local public agencies/organizations (municipal governments, local fisheries cooperatives, etc) | 3.00 | 1.38 | 2.82 | 1.14 | 2.69 | 0.96 | |||||

| 11. Trust in national public agencies (the Cabinet, Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, Fisheries Agency, etc) | 2.51 | 1.21 | 2.35 | 1.07 | 2.47 | 0.97 | |||||

| 12. Trust in local private agencies/organizations (residents’ association, block association, PTA, temples, shrines, churches, etc) | 3.13 | 1.10 | 3.06 | 0.98 | 2.65 | 0.83 | ** | A > C | |||

GLM (bonferroni)

Human well-being F(11, 204) = 24.90**

Sectors F(2, 214) = 1.68 n.s.

Human well-being vs Sectors F(22, 410) = 1.26 n.s.

p < 0.10†, p < 0.05*, p < 0.01**

3.7. Free answer analysis

When two close-ended questions were asked about how satisfied survey respondents were with Japanese fisheries before and during the Covid-19 outbreak, results showed that even before Covid-19, 58.7% of respondents said they were unsatisfied with the situation. During Covid-19, as much as 77.7% of respondents claimed that it had worsened ( Fig. 8). In investigating opinions on the state of fisheries before Covid-19 and on post-covid recommendations for the industry, a total of 206 participants provided open-ended answers, from which eleven subgraphs were extracted, as shown in Fig. A.15 and Table 2 (see Table. A.3 for all the keywords and interpretation of each subgraph).

Fig. 8.

Satisfaction scores about Japanese fisheries before (left) and during (right) Covid-19.

Table 2.

Subgraph classification and topic categories extracted from opinions on the state of Japanese fisheries before Covid-19 and on post-Covid-19 visions for the industry as a whole. Colored fonts show which category of challenges each subgraph belongs to: natural resources, market, fishers and fishing-related businesses (participants) and globalization. Black colored categories refer to the absence of problems before Covid-19 (S09) and to cross-cutting meanings/themes (before Covid-19 S11 and post Covid-19 S01, 03, 06, 07).

| Before Covid-19 | Post Covid-19 |

|---|---|

| S01: Profitability trend | S01: Transformation of fishery sector |

| S02: Situation of fishers | S02: Rethink of export strategy |

| S03: Fishers’ low awareness | S03: Structural challenge of fisheries sector |

| S04: Limited resource management | S04: Advanced fisheries technology |

| S05: Hard domestic situation of fisheries | S05: Sustainable production |

| S06: International market and Japan | S06: National administration |

| S07: Catch decline | S07: Corona and tradition |

| S08: Consumption decline | S08: Domestic and international market |

| S09: No problem | S09: Fishery management |

| S10: Price instability | S10: Situation of transportation |

| S11: Business assistance | S11: Ocean as nature |

When interpreting the keywords making up each group or subgraph, four topic categories were identified as major challenges for Japanese fisheries: (i) “natural resources”, (ii) “market”, (iii) “fishers and fishing-related businesses” (participants), and (iv) “globalization” (Table 2). The first challenge concerns natural resources, which originates from the fact that fishery resources have been in constant decline since the early 1990s [4], [23]. Respondents perceived fishery resource management as insufficient and not effective enough, as evidenced by the catch decline experienced by most survey participants. Second, market challenges refer to the structure of supply chains, notably transportation and consumption. There was a perception that respondents have been suffering from structural problems along the seafood supply chain in Japan. The third challenge relates to fishers and participants involved in fishing-related businesses, specifically their capacity and consciousness. They hinted at the need for their peers and colleagues in the sector to further develop and improve their capacity and overall awareness in order to better the fishing industry. Finally, the last category revolves around globalization and its challenges on international marketing strategies for Japanese fisheries. Survey respondents mentioned the need to establish a better strategy to survive in the global market and retain the economic, social and cultural values of their fishing practices.

By classifying the meaning of all identified subgraphs, four similar challenges became apparent when looking at both opinions before and after Covid-19 (Table 2). However, regarding visions for post Covid-19 Japanese fisheries, there was a clear collective call for transformative changes and a thoughtful recovery if the industry is to overcome this difficult period, as exemplified by the subgraphs: S01: Transformation of fisheries sector, S02: Rethink of export strategy and S07: Corona and tradition.

4. Discussion and conclusion

4.1. The multifaceted impacts of Covid-19 on the Japanese fishing industry

Across all survey respondents, the perceived economic effects from the coronavirus outbreak revealed overwhelmingly negative changes in 2020 sales figures when compared to a year earlier (Fig. 3). Within the fisheries and aquaculture sector, corporate businesses appeared slightly more vulnerable to the spread of Covid-19 than family-run enterprises, which could potentially be explained by the more diverse and flexible nature of small-scale fishing activities in Japan (Fig. A.13) [24]. When broken down by sub-sector, coastal fishing (primarily composed of SSF) was indeed one of the least impacted during the coronavirus outbreak, while aquaculture was found to be the most economically affected sub-sector (Fig. 3 c). In cross-checking the survey’s subjective results with objective economic information, this study confirms the perceptions of economic loss that stemmed from declines in sales volumes and unit prices (Fig. 4, Fig. 5, Fig. 6).

Taking a more granular view at the fish product and fish grade levels revealed some important underlying dynamics, such as: (i) the increased abundance of Japanese sardine that was expected in 2020 [25], and which led to an increase in fishing activity that inflated overall changes in landings of low value fish in Japan7 (Fig. 6 b); (ii) the consistent decrease in demand and price of high-value species (Figs. 6 b, 6 d), which, coinciding with voluntary stay-at-home orders and closures of high-end seafood restaurants (e.g. sushi), allowed middle class consumers to buy luxury seafood products at a more affordable price in supermarkets and other retail outlets [2], [26]; (iii) the significant decline in both imports and exports of fresh fish in 2020 when compared to their pre-covid average (Fig. 7), a trend observed across other OECD countries [1], [27]; (iv) the remarkable increase in exports of frozen albacore tuna during the summer of 2020 (Fig. A.9), which originated from the compounding effects of a reduced demand for fresh fish products and an ephemeral rise in the international price of frozen albacore, incentivizing Japanese fishers to freeze and export as much of their catch as possible (Hidetaka Kiyofuji, pers. comm.), the majority of which destined for reprocessing purposes in Southeast Asia (Fig. A.11); and (v) the exported quantities of high-value live red sea bream to South Korea (Fig. A.8), which increased by more than 100% for 3 consecutive months in the summer of 2020 (Fig. 7).

The analysis of social capital revealed that certain kinds of informal social relations or bonding social capital [13], such as friends and acquaintances for SSF operators, and corporate partners and clients pre-Covid-19 for fishing-related businesses, were felt to be more helpful than government agencies when dealing with the consequences of the pandemic (Fig. A.14). In addition, more than half of survey respondents currently reside in their hometown (around one third has never left since birth), which might also imply that Japanese fisheries, mainly represented by SSF, showed greater resilience against Covid-19 due to their customary fabric of mutual help as well as diversified target species portfolios (Fig. A.13).

The human well-being analysis also supported this “bonding” feature of Japanese fisheries, as satisfaction levels on relationships with community members were significantly higher in SSF than in fishing-related businesses ( Table 1). Finally, through the examination of opinions about the pre-Covid state and future of the Japanese fishing industry, four major topic categories were identified: “natural resources”, “markets”, “fishers and fishing-related business participants” and “globalization” (Fig. A.15, Table 2). Some of these include recurring challenges and transformative opportunities for the industry, which will need to be heeded for a just, fair and sustainable recovery, especially considering that the percentage of unsatisfied respondents with the situation around Japanese fisheries climbed from 58.7% to 77.7% during the pandemic (Fig. 8).

4.2. Monitoring Covid-19 impacts on fisheries resource stocks

Fishing fleet activities in Japan seemed relatively unscathed in 2020, especially during the first two quarters, as fish landings saw sporadic but non-negligible increases between February and August when compared to previous years (Fig. 5, Fig. 6). And with 65% of a sub-sample of surveyed fishers declaring no changes in fishing effort during the pandemic (Fig. A.12), this study does support some earlier findings from Global Fishing Watch (https://globalfishingwatch.org/news-views/covid-19-japanese-fisheries/). One potential reason is that Japan has experienced relatively mild impacts from Covid-19, including no strictly imposed lockdowns when compared to other major fishing nations such as the US, Spain and Italy. Japan’s extensive and entrenched seafood production and consumption habits [3], [4] could also have influenced this phenomenon, as people would be unlikely to radically change their consumption preferences because of Covid-19.

This paper also indicates that short-term economic incentives to ramp up landings of albacore tuna8 in the summer of 2020 (Figs. A.7,A.9), combined with natural variations in the stocks of Japanese sardine, were the most likely drivers of positive changes in landings of fish between March and August 2020 (Fig. 5, Fig. 6). This shows that increases and decreases in catch are not solely due to the effects of Covid-19. As such, continuous monitoring and analysis of updated information such as socioeconomic and fisheries statistics as well as stock assessments will be essential to scientifically clarify the “real” relationship between the Covid-19 outbreak, the behavior of Japanese fishers and the health of resource stocks.

4.3. Study limitations

The survey data used for this study were collected online, which could have potentially biased the median age of respondents downward (Fig. A.2). As such, validating the results of this work might require further investigations and cross-checking with offline collected data, which would most likely include a greater percentage of older respondents. Additionally, the transdisciplinary group of this paper is already developing in-depth, follow-up interviews with respondents who showed willingness to take part in the initial survey. The results and implications of this paper need to be also validated by other stakeholders, which could help facilitate the co-design and co-development of meaningful studies addressing challenges around the Covid-19 pandemic.

Baseline data compiled on fisheries landings and unit price covered some of the most important fish species in Japan.9 While it can be assumed that these 24 different species are representative enough of how fisheries have been impacted by the coronavirus outbreak, it is important to not lose sight of the sheer diversity (more than 400) of species caught across Japanese waters [24]. In addition, with economic data aggregated at the national level, this study does not capture potential differences in regional and prefectural responses to Covid-19. The targeted species and types of gear used differ widely across the archipelago, especially when comparing northern (Hokkaido/Tohoku) and southern (Kyushu) fishing grounds [4]. As such, investigating geographical disparities in the impacts of Covid-19 on Japanese fisheries should be part of future research work.

4.4. Policy implications

This paper implies that bonding social capital among SSF operators and fishing-related business participants helped to mitigate the negative impacts of the pandemic. Since the onset of the pandemic, several studies around the world have reported that sudden changes (e.g. halt) in existing seafood supply chains have prompted fishers to use some alternative modes of distribution, such as direct-to-consumer sales and community-supported fisheries [16], [28], [29]. In Japan, community-supported agriculture, which partly deals with seafood, has become popular since the 1970s [30], [31] and following the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake, where direct marketing for individual fishers has greatly developed in affected areas [32]. Although these community-supported fishery practices have been marginal in the distribution of fishery products, this paper shows that Covid-19 incentivized some businesses to increase direct sales to consumers (especially online) to cope with some of the losses (Fig. A.6), presumably through existing informal social relations or networks.

This “customary nature” of Japanese fisheries, which relates to the unique features and traditional characteristics of fisheries along the archipelago,10 can help the whole industry adapt to strong external shocks such as Covid-19, but it could also constitute a barrier to the sector’s transformation. Indeed, the multi-layered and seemingly immutable structure of the Japanese seafood distribution system might hinder desirable transformations along the supply chain, which is heavily reliant on traditional and customary wholesale markets [33]. Severely impacted in 2020, customary wholesale markets run by fishery cooperatives were by far the most dominant sales channels used by primary producers before the Covid-19 outbreak (Fig. A.5). The free-answer analysis also revealed that many respondents suffered from protracted challenges related to the structure of the seafood supply chain, including transportation and consumption (see Section 3.7).

Besides these structural problems, Japanese fishing communities are also facing an aging and declining population [7], complicating hopes for further transformation. Although support from the government during the pandemic included allocated funds to purchase and store fish surpluses [1], [34], the different issues raised above will need to be accounted for in post-covid recovery strategies for the fishing industry.

At the time this paper was written in late 2020, the new fisheries policy reform was just starting to be implemented. With the goal of increasing the productivity of the fisheries and aquaculture sector, two important components of this reform include the enhancement of fisheries resource management and the entry of private companies into fishery businesses (particularly large-scale aquaculture operations) [35]. Considering the economic and social disruptions caused by the Covid-19 outbreak on the fishing industry, this paper offers three post-recovery recommendations: (1) to monitor how the lingering effects of Covid-19, the health of fish stocks and the behavior of fishers and fishing-related businesses interrelate, (2) to consider the multi-dimensional aspects of the productivity-driven policies that promote large-scale aquaculture operations, which were shown to be the most vulnerable to Covid-19, and (3) to support the need for supply chain transformations, which was one of the main issues raised by survey participants when asked about their vision for the future of the Japanese fishing industry. These implications need to be heeded to build a better and more sustainable future for Japanese fishers, post-harvest workers, fishing-related businesses and coastal communities alike, both during and after the Covid-19 pandemic.

Funding

This research has not used any external funding source.

Author statement

AS and NT: Research design, data collection, stakeholder communication, AS, RR and JH: Data analysis, AS and RR: Writing and revising the manuscript, SW and MM: Advisory role in some specific topics.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely express our gratitude to all survey participants who contributed their valuable time to this work, and people who cooperated with the distribution of the questionnaires. In addition, we particularly thank Drs. Hein Mallee, Yoko Mitani, Takahiro Matsui, Shuichi Watanabe, Tetsuo Fujii, Hidetaka Kiyofuji, Noriko Ishida, Hidetomo Tajima, Ms. Megumi Kodera, Mr. Hajime Oshima and many others for their support and insights to accomplish this work. We also thank the Public Relations Unit of the Research Institute for Humanity and Nature for creating the graphic abstract and Fig. A.1.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

The data are publicly available and can be accessed here (in Japanese): http://www.market.jafic.or.jp/

Live fish are distinct from fresh fish in that they are still alive when arriving at their export destination.

The Suisan-Keizai Daily News (https://www.suikei.co.jp/%e3%82%b3%e3%83%ad%e3%83%8a%e3%81%a7%e5%a3%b2%e4%b8%8a%e3%81%923%e5%89%b2%e6%b8%9b%e3%80%81%e6%b5%81%e9%80%9a%e6%94%b9%e9%9d%a9%e3%81%ab%e6%9c%9f%e5%be%85%ef%bc%8f%e5%9c%b0%e7%90%83%e7%a0%94%e3%83%bb/?fbclid=IwAR3PkBfDrI1r_4NGbdmWEuaAlwW9UaJfjmFNROaZRMHDMqMZtvTyPKMI9LY), The Minato Daily News (https://www.minato-yamaguchi.co.jp/minato/e-minato/articles/103579)

The “fisheries cooperative” sub-sector includes cooperative employees (e.g. officers) who are mainly involved in post-harvest and management activities.

This median age is younger than the median age of fishers, which is 57 years old (https://www.jfa.maff.go.jp/j/kikaku/ wpaper/R1/01hakusyo_info/index.html). It might be due to the inclusion of participants in processing and other fishing-related businesses, and/or by the online survey style that younger generations are more familiar with.

Specifically, respondents were invited to indicate how much they thought their sales had changed by moving a cursor along a bar ranging from − 100% to + 100%, where − 100% (+100%) can be interpreted as a 2 times decrease (increase) in total sales revenues when compared to 2019. The authors acknowledge that this particular design might have prevented respondents from providing a proper and accurate assessment if their sales happened to change beyond 100%.

In addition, as Japanese sardine is usually targeted by medium- and large-scale purse seiners [4], it can be assumed that the 2020 increase in abundance did not benefit small-scale family-based fishing operations.

Albacore tuna was classified as a medium value species (see Section 2.2. and Table A.2).

Although it is worth mentioning that Pacific salmon were not included in the distribution survey.

Such as the preponderance of small-scale fishing operations, their embedment within the fabric of local communities and the targeting of seasonally diverse fish resources using multiple fishing gears (varying by region and prefecture).

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2022.105005.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

.

References

- 1.OECD, Fisheries, aquaculture and Covid-19: Issues and policy responses, OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (2020).〈http://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/fisheries-aquaculture-and-covid-19- issues-and-policy-responses-a2aa15de/〉.

- 2.Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations FAO, How is Covid-19 outbreak impacting the fisheries and aquaculture food systems and what can FAO do, FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Department (2020). 〈http://www.fao.org/3/cb1436en/cb1436en.pdf〉.

- 3.FAO, The state of world fisheries and aquaculture - Sustainability in Action, Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations, Rome. (2020) 206 pp. 〈http://www.fao.org/documents/card/en/c/ca9229en/〉.

- 4.Makino M. Springer Science & Business Media; 2011. Fisheries Management in Japan: its institutional Features and Case Studies. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Österblom H., Jouffray J.B., Folke C., Rockström J. Emergence of a global science–business initiative for ocean stewardship. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2017;114:9038–9043. doi: 10.1073/pnas. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Makino M., Watari S., Hirose T., Oda K., Hirota M., Takei A., Ogawa M., Horikawa H. A transdisciplinary research of coastal fisheries co-management: the case of the hairtail Trichiurus japonicus trolling line fishery around the Bungo Channel, Japan. Fish. Sci. 2017;83:853–864. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s12562-017-1141-x. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Teh L.C.L., Teh L.S.L., Abe K., Ishimura G., Roman R. Small-scale fisheries in developed countries: looking beyond developing country narratives through Japan’s perspective. Mar. Policy. 2020;122 https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2020.104274. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li Y., Namikawa T. 2020. In the era of big change. Essays about Japanese small-scale fisheries; p. 582.〈https://tbtiglobal.net/in-the-era-of-big-change/〉 (TBTI Global Book Series). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Core Team R. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna: 2019. 〈https://www.r-project.org〉 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Putnam R.D. Princeton University Press,; Princeton, NJ: 1993. Making Democracy Work. Civic Traditions in Modern Italy. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nakagawa Y., Rebecca S. Social capital: a missing link to disaster recovery. Int. J. Mass Emergencies Disasters. 2004;22(1):5–34. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saswata S., Routray J.K. Social capital for disaster risk reduction and management with empirical evidences from Sundarbans of India. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2016;19(May 2018):101–111. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdrr.2016.08.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clay P.M., Colburn L.L., Seara T. Social bonds and recovery: an analysis of hurricane sandy in the first year after landfall. Mar. Policy. 2016;74:334–340. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Habersaat K.B., Betsch C., Danchin M., Sunstein C.R., Böhm R., Falk A., Brewer N.T., Omer S.B., Scherzer1 M., Sah S., Fischer E.F., Scheel A.E., Fancourt D., Kitayama S., Dubé E., Leask J., Dutta M., MacDonald N.E., Temkina A., Lieberoth A., Jackson M., Lewandowsky S., Seale H., Fietje N., Schmid P., Gelfand M., Korn L., Eitze S., Felgendreff L., Sprengholz P., Salvil C., Butler R. Ten considerations for effectively managing the COVID-19 transition. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2020;4:677–687. doi: 10.1038/s41562-020-0906-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Speir C., Ridings C., Marcum J., Drexler M., Norman K. Measuring health conditions and behaviors in fishing industry participants and fishing communities using the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Survey (BRFSS) ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2020;77(5):1830–1840. doi: 10.1093/icesjms/fsaa032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.N. Bennett, N., Ban, A. Schuhbauer, D.-V. Splichalova, M. Eadie, K. Vandeborne, J., McIsaac, E. Angel, J. Charleson, S. Harper, T. Sutcliffe, E. Gavenus, R. Sumaila, T. Satterfield, Fishing for a future: Understanding access issues and wellbeing among independent fish harvesters in British Columbia, Canada, Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, 2020. https://ecotrust. ca/latest/research/fishing-for-a-future-understanding-access-issues-and-wellbeing-among-independent-fish-harvesters-in-bc-2020/ (Accessed 29 January 2021).

- 17.Hori J., Makino M. The structure of human well-being related to ecosystem services in coastal areas: a comparison among the six North Pacific countries. Mar. Policy. 2018;95:211–226. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2018.02.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ban N.C., Gurney G.G., Marshall N.A., Whitney C.K., Mills M., Gelcich S., Bennett N.J., Meehan M.C., Butler C., Ban S., Tran T.C., Cox M.E., Breslow S.J. Well-being outcomes of marine protected areas. Nat. Sustain. 2019;2:524–532. doi: 10.1038/s41893-019-0306-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaplan-Hallam M., Bennett N.J. Adaptive social impact management for conservation and environmental management. Conserv. Biol. 2018;32(2):304–314. doi: 10.1111/cobi.12985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lazarsfeld P.F., Barton A.H. In: The Policy Sciences: Recent Developments in Scope and Method. Lerner D., Lasswell H.D., editors. Stanford University Press; Stanford: 1951. Qualitative measurement in the social sciences, classification, typologies, and indices; pp. 180–188. (CA) (CA) [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saporta S., Sebeok T.A. In: Trends in Content Analysis. Pool I. d S., editor. University of Illinois Press; Urbana, IL: 1959. Linguistic and content analysis; pp. 131–150. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Higuchi K. Nakanishiya Press; Kyoto, Japan: 2014. Quantitative Content Analysis for Social Researchers: A Contribution to Content Analysis. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ichinokawa M., Okamura H., Kurota H. The status of Japanese fisheries relative to fisheries around the world. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2017;74:1277–1287. doi: 10.1093/icesjms/fsx002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Delaney A., Yagi N. In: The Small-Scale Fisheries Guidelines. Jentoft S., Chuenpagdee R., Barragán-Paladines M., Franz N., editors. vol 14. Springer; Cham: 2017. Implementing the small-scale fisheries guidelines: lessons from Japan; pp. 313–332. (MARE Publication Series). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Furuichi, S., Yukami, R., Kamimura, Y., Hayashi, A., Isu, S., and Watanabe, R. (2020). “Stock assessment and evaluation for the Pacific stock of Japanese sardine (fiscal year 2019),” in Marine Fisheries Stock Assessment and Evaluation for Japanese Waters (fiscal year 2019/2020), ed. Fisheries Agency and Fisheries Research and Education Agency of Japan (in Japanese). Available online at: 〈http://www.abchan.fra.go.jp/digests2019/details/201901.pdf〉 (accessed June 17, 2020).

- 26.K. Daigo, COVID-19 disruption puts Toyosu’s top-shelf fish in easy reach, Nippon.com (2020). 〈https://www.nippon.com/en/japan-topics/g00855/〉.

- 27.White E.R., Froehlich H.E., Gephart J.A., Cottrell R.S., Branch T.A., Agrawal Bejarano R., Baum J.K. Early effects of COVID-19 on US fisheries and seafood consumption. Fish Fish. 2020;22:232–239. doi: 10.1111/faf.12525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.S.L. Smith, A..Golden, V. Ramenzoni, D.R. Zemeckis, O.P. Jensen, Adaptation and resilience of commercial fishers in the Northeastern United States during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.J.S. Stoll, H.L. Harrison, E.D. Sousa, D. Callaway, M. Collier, K. Harrel, B. Jones, J. Kastlunger, E. Kramer, S. Kurian, A. Lovewell, S. Strobel, T. Sylvester, B. Tolley, A. Tomlinson, T. Young, P.A. Loring (in review) Alternative seafood networks during COVID-19: Implications for resilience and sustainability.

- 30.McGreevy S.R., Akitsu M. In: Genus A., editor. vol 3. Springer; Cham: 2016. Steering sustainable food consumption in Japan: trust, relationships, and the ties that bind; pp. 101–117. (Sustainable Consumption. The Anthropocene: Politik—Economics—Society—Science). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kondoh K. The alternative food movement in Japan: challenges, limits, and resilience of the Teikei system. Agric. Hum. Values. 2015;32:143–153. doi: 10.1007/s10460-014-9539-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Manabe K., Nakatsuka M. A study on actual management and development process of the magazine with food. J. Rural. Plan. Assoc. 2017;36:258–263. doi: 10.2750/arp.36.258. (in Japanese) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.N. Yagi, Value Chains of Fishery Products, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (2011). 〈http://www.fao.org/valuechaininsmallscalefisheries/participatingcountries/japan/en/〉.

- 34.Japan Fisheries Agency, Supply Leveling Project for Specified Marine Products (in Japanese). 〈https://www.jfa.maff.go.jp/j/council/seisaku/kanri/attach/pdf/200525–6.pdf〉, 2020.

- 35.Sugimoto A. An empirical study on the intentions of private companies for their entry into the fisheries business in Japan. J. Coast. Zone Stud. 2020;33(1):35–44. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.