Abstract

Background

Hundreds of candidate genes have been associated with coronary artery disease (CAD) through genome-wide association studies (GWAS). However, a systematic way to understand the causal mechanism(s) of these genes, and a means to prioritize them for further study, has been lacking. This represents a major roadblock for developing novel disease- and gene-specific therapies for CAD patients. Recently, powerful integrative genomics analyses (IGA) pipelines have emerged to identify and prioritize candidate causal genes by integrating tissue/cell-specific gene expression data with GWAS datasets.

Methods

We aimed to develop a comprehensive IGA pipeline for CAD and to provide a prioritized list of causal CAD genes. To this end, we leveraged several complimentary informatics approaches to integrate summary statistics from CAD GWAS (from UK Biobank and CARDIoGRAMplusC4D) with transcriptomic and expression quantitative trait loci data from nine cardiometabolic tissue/cell types in the STARNET study.

Results

We identified 162 unique candidate causal CAD genes, which exerted their effect from between one and up to seven disease-relevant tissues/cell types, including the arterial wall, blood, liver, skeletal muscle, adipose, foam cells and macrophages. When their causal effect was ranked, the top candidate causal CAD genes were CDKN2B (associated with the 9p21.3 risk locus) and PHACTR1; both exerting their causal effect in the arterial wall. A majority of candidate causal genes were represented in cross-tissue gene regulatory co-expression networks that are involved with CAD, with 22/162 being key drivers in those networks.

Conclusions

We identified and prioritized candidate causal CAD genes, also localizing their tissue(s) of causal effect. These results should serve as a resource and facilitate targeted studies to identify the functional impact of top causal CAD genes.

Keywords: Coronary artery disease, genetics, atherosclerosis, systems biology

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have been remarkably informative and provided lists of hundreds of variants that are associated with coronary artery disease (CAD).1-3 Based largely on proximity, researchers have somewhat arbitrarily inferred the genes that are most likely to be associated with these variants.4,5 Despite the success of GWAS, this raises a number of concerns. To begin with, these inferences assigning genes that are associated with these variants rely on several assumptions and are not always correct.4,5 Furthermore, for most of these genes we do not know which are truly causal, rather than just being associated with CAD. In addition, at present there is no overall prioritized ranking of these genes based upon which are the most important for causing CAD.

Yet another issue arising from GWAS is the lack of knowledge of which disease-relevant tissue(s) a given CAD-related gene exerts its effect in. For example, genes that might cause CAD can exert effect(s) in adipose, liver, inflammatory cells, the arterial wall, and other tissues/cell types. This lack of knowledge of both the prioritized importance of CAD genes, and also their tissue(s) of causal effect, is a major obstacle to scientific efforts to understand atherosclerosis and CAD. Indeed, at present, of the almost 300 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) known from GWAS to be associated with CAD,1-3 there are limited insights into the specific genes and tissues involved in modulating their CAD risk effect.1-3 On the other hand, a prioritized list of causal CAD genes, and knowledge of their tissues of causal effect, would be a key resource that would allow targeted studies to identify the functional impact of the top causal genes for CAD in appropriate tissues.

As an important advance, powerful techniques have emerged for integrating tissue and cell-specific data with GWAS datasets. These integrative genomics analysis (IGA) methodologies include the Transcriptome-Wide Association Study (TWAS), Summary-based Mendelian Randomization (SMR),6,7 MetaXcan8 and Coloc.9 IGA approaches integrate GWAS datasets with gene expression measurements (e.g. expression quantitative trait loci (eQTLs)), which permit the identification of specific genes and variants that are not only associated with CAD but which also directly govern aspects of disease pathobiology. Furthermore, IGA methodologies have the potential to determine causality and are well suited to the agnostic prioritization of causal mediators of disease pathobiology.10

In terms of resources that could be used to undertake an IGA for CAD, as well as publicly available GWAS datasets, STARNET (Stockholm-Tartu Atherosclerosis Reverse Network Engineering Task) is a genetics-of-gene expression study that now includes >1000 CAD subjects and >250 controls of European ancestry.11,12 From each subject, venous blood (BLOOD) as well as biopsies from atherosclerotic aortic wall (AOR), pre/early-atherosclerotic mammary artery (MAM), liver (LIV), skeletal muscle (SKLM), subcutaneous fat (SF) and visceral fat (VAF) were obtained and RNA was extracted. BLOOD was also used to obtain macrophages (MP) and foam cells (FC). The STARNET datasets have been extensively curated and already provided significant insights on CAD pathobiology,5,13 and in particular on gene regulatory co-expression networks (GRNs) that contribute to CAD heritability.12 Here, we used next-generation RNA sequencing data from blood and up to 8 different tissues/cell types that were collected from STARNET CAD subjects, and intersected this with CAD GWAS datasets,1,2 to develop a comprehensive IGA pipeline for CAD in a disease-relevant context. Resulting from this, and as a key scientific resource, we provide a prioritized list of 162 candidate causal CAD genes and the tissues in which they govern CAD risk.

METHODS

As a key resource in this study, the STARNET study has been extensively described.5,11-15 Briefly, after providing written informed consent, patients with angiographically proven CAD who were eligible for open-thorax surgery and control subjects without CAD were enrolled into this institutional review committee approved protocol (Ethics Review Committee on Human Research of the University of Tartu). The STARNET data is accessible through Database of Genotypes and Phenotypes (dbGAP), accession phs001203.v1.p1. The subsequent IGA incorporated two data sources: GWAS summary statistics from an interim release of UK Biobank (UKBB) data1 or CARDIoGRAMplusC4D2 and tissue/cell-specific eQTLs from STARNET11 and these datasets are available through those sources. Datasets used in this study are also summarized in Supplemental Table I. All methods are described in the Supplemental Methods, or where mentioned in prior STARNET publications.5,11-15 The corresponding authors are also willing to address queries regarding the data or results upon reasonable request.

RESULTS

Proof-of-concept studies to determine causal tissues and cell types for CAD

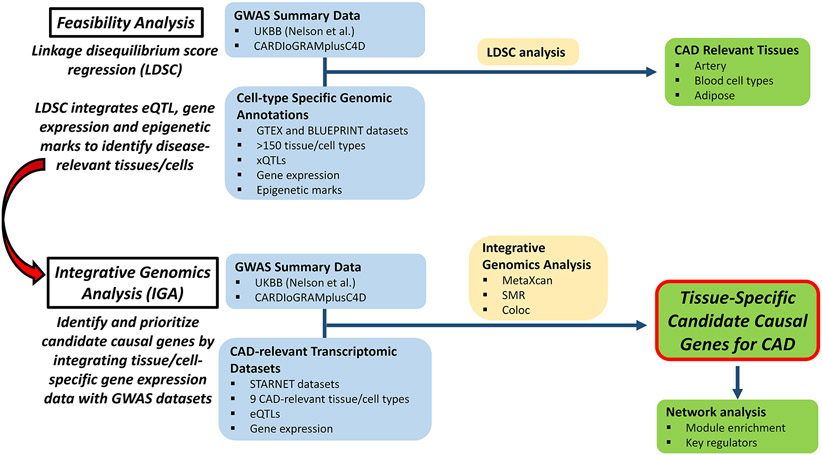

A study overview is shown in Figure 1. To ascertain the feasibility of determining the tissues/cells in which genes identified by GWAS exert their effects in promoting CAD, we performed a linkage disequilibrium score regression (LDSC) analysis by leveraging publicly available data from BLUEPRINT16,17 and GTEx (the Genotype-Tissue Expression project),18 and GWAS data from either UKBB1 or CARDIoGRAMplusC4D.2 LDSC integrates eQTL, gene expression and epigenetic marks to identify disease-relevant tissues/cells. From the multiple diverse tissues represented in this analysis, the majority of which are not related to the heart or vasculature, we identified a clear tissue enrichment signal that the pathobiology of CAD is predominantly driven by tissues/cells of the cardiovascular and immune systems (Supplemental Tables II and III). This unbiased analysis indicates that it is possible to determine the tissues/cells that promote CAD by integrating GWAS and epigenomic datasets.

Figure 1. Flow diagram and study design.

IGA identifies and prioritizes candidate causal genes for CAD

Our IGA pipeline incorporated two sources of data: GWAS summary statistics (from both UKBB and CARDIoGRAMplusC4D) and tissue/cell-specific eQTLs from STARNET. Our IGA employed three methods from two broad classes: MetaXcan and SMR (class 1) and Coloc (class 2). We intersected the results of class 1 and 2 methods to identify a set of likely causal CAD genes. In total, 197,888 class 1 tests (MetaXcan and SMR, Supplemental Table IV) were conducted, on which we calibrated the FDR. Findings at ≤ 5% FDR were further filtered by genetic co-localization posterior probability estimated by Coloc.

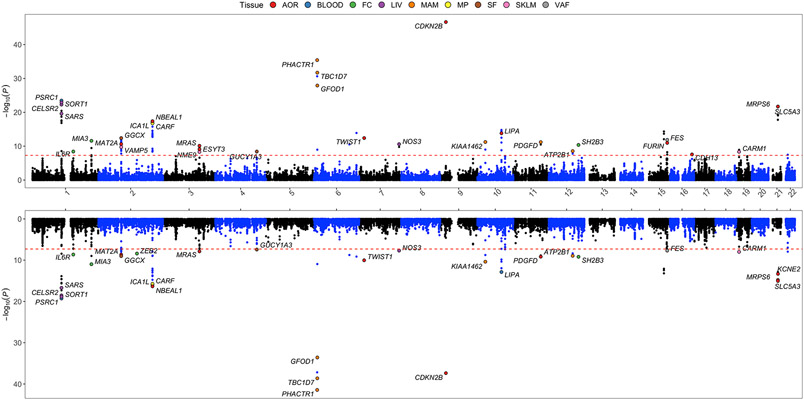

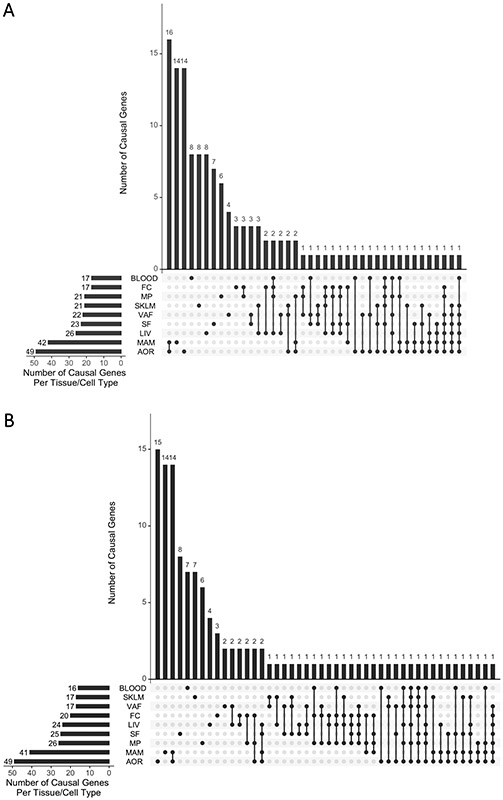

Using the UKBB and CARDIoGRAMplusC4D GWASs, our IGA pipeline revealed 129 and 121 candidate CAD causal genes, respectively (Supplemental Tables V and VI). Genes demonstrating the strongest MetaXcan evidence (P < 5x10−8) were visualized in Figure 2. The STARNET eQTLs and this IGA pipeline allowed us to pinpoint the tissue-specificity of causal genes (Figure 3), and candidate causal CAD genes were identified as exerting their effect in differing numbers of tissue/cell types which ranged from 1 up to 7 types. Notably, arterial wall tissues (AOR and MAM) yielded the greatest number of candidate causal CAD genes. For example, the IGA integrating AOR eQTLs with UKBB or CARDIoGRAMplusC4D GWASs both yielded 49 candidate causal genes; while the IGA involving MAM eQTLs with UKBB or CARDIoGRAMplusC4D GWASs yielded 42 and 41 candidate causal CAD genes, respectively (Figure 3). These findings indicate that the arterial wall is of major importance with respect to CAD pathogenesis.

Figure 2. Manhattan plot of IGA and MetaXcan results demonstrating tissue-specific gene expression associated with CAD genetic risk loci.

Upper panel, candidate CAD causal genes identified by integrating STARNET eQTLs (9 tissue/cell types) and UKBB GWAS data.1 Y axis denotes −log10(MetaXcan P value). Only genes with a MetaXcan P value < 5x10−8 (dashed red line) are shown. The tissue where the most significant MetaXcan P value was observed is color coded. Lower panel, candidate CAD causal genes identified using the same IGA pipeline by integrating STARNET eQTLs and CARDIoGRAMplusC4D CAD GWAS.

Figure 3. Summary of IGA and MetaXcan results.

(A) MetaXcan results based on UKBB GWAS data. The X axis shows different tissue/cell types, and combinations of these different tissue/cell types, from among the 9 tissue/cell types sampled in STARNET. The Y axis shows the number of genes identified by MetaXcan for that combination of tissue/cell types. (B) As per (A), showing MetaXcan results based on CARDIoGRAMplusC4D GWAS data.

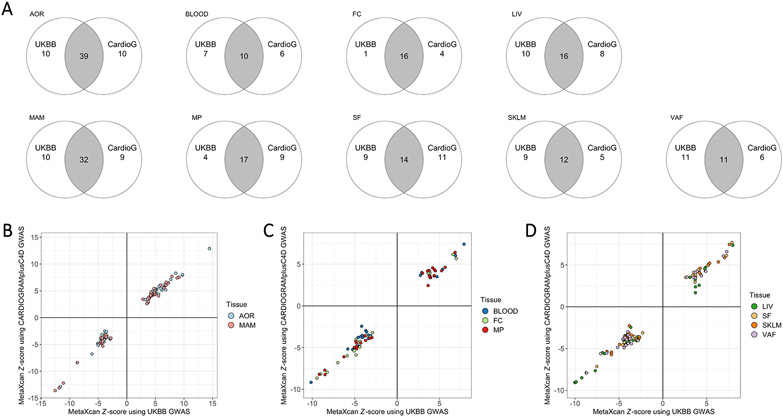

In comparing the IGA results using GWAS data from UKBB versus CARDIoGRAMplusC4D, there was reasonably strong overlap for most of the 9 tissue/cell types (Figure 4A). In addition, we found a high degree of concordance for Z-score results generated using MetaXcan alone for UKBB versus CARDIoGRAMplusC4D GWAS data when integrated with STARNET eQTL data. Importantly, this concordance was not only in terms of the specific candidate causal genes identified, but also both the tissues in which they are likely to be causal and the directionality of their association with CAD (Figures 4B - 4D).

Figure 4. Concordance of IGA using STARNET with alternate GWAS datasets.

(A) Venn diagrams showing the number of candidate causal CAD genes, for each tissue/cell type in STARNET, identified in an IGA using STARNET with either UKBB or CARDIoGRAMplusC4D (CardioG). (B) x-y plots of Z-score results generated using MetaXcan alone for UKBB versus CARDIoGRAMplusC4D GWAS data when integrated with STARNET eQTL data for AOR and MAM. (C) x-y plot as per (B) but using STARNET eQTL data for BLOOD, FC and MP. (D) x-y plot as per (B) but using STARNET eQTL data for LIV, SF, SKLM and VAF.

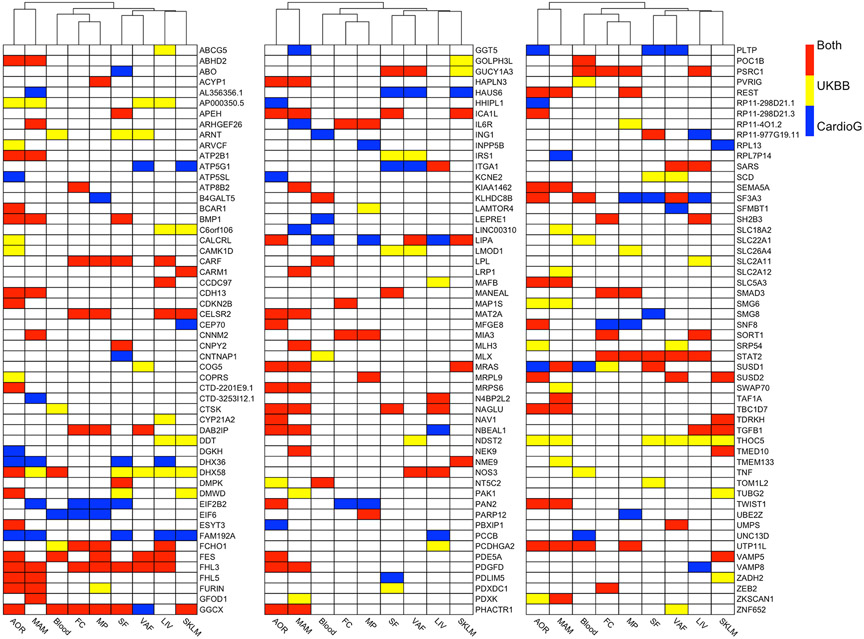

In considering the number of candidate causal CAD genes across the IGAs performed using either UKBB or CARDIoGRAMplusC4D with STARNET (129 and 121 genes, respectively), there were a total of 162 unique candidate causal CAD genes across both IGAs. These 162 candidate causal CAD genes were then ranked by P value and the top 25 are presented in Table 1, with all 162 ranked genes presented in Supplemental Table VII. These 162 candidate causal CAD genes were found to exert their effects across a mean of 1.9 ± 1.4 tissue/cell types (mean ± SD) (Figure 5, Supplemental Table VII).

Table 1. Top 25 prioritized candidate causal genes for CAD identified using our IGA pipeline with either UKBB1 with STARNET,12 or, CARDIoGRAMplusC4D2 with STARNET.12.

Candidate causal genes were prioritized based on the smallest P value for the class 1 analyses (MetaXcan or SMR), however, for all of these top 25 candidate causal genes the most significant P value was obtained with MetaXcan (as opposed to SMR). Full results for all 162 candidate causal genes are in Supplemental Table VII.

| Candidate casual CAD gene |

Most significant P value |

Tissue with most significant P value |

GWAS used in IGA with most significant P value (UKBB or CaridoG) |

Causal in that tissue in UKBB, CaridoG, or Both |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CDKN2B | 2.16x10−47 | AOR | UKBB | Both |

| PHACTR1 | 3.65x10−42 | MAM | CardioG | Both |

| TBC1D7 | 2.40x10−39 | MAM | CardioG | Both |

| GFOD1 | 2.64x10−34 | MAM | CardioG | Both |

| PSRC1 | 3.40x10−24 | BLOOD | UKBB | Both |

| SORT1 | 1.18x10−23 | LIV | UKBB | Both |

| CELSR2 | 5.19x10−23 | LIV | UKBB | Both |

| MRPS6 | 1.96x10−22 | AOR | UKBB | Both |

| SLC5A3 | 1.96x10−22 | AOR | UKBB | Both |

| SARS | 2.42x10−20 | LIV | UKBB | Both |

| KCNE2 | 8.19x10−20 | AOR | UKBB | CardioG |

| NBEAL1 | 4.04x10−18 | AOR | UKBB | Both |

| ICA1L | 1.08x10−17 | AOR | UKBB | Both |

| CARF | 1.79x10−17 | MP | UKBB | Both |

| LIPA | 1.58x10−15 | LIV | UKBB | Both |

| GGCX | 3.94x10−13 | SF | UKBB | Both |

| TWIST1 | 3.97x10−13 | AOR | UKBB | Both |

| VAMP5 | 1.11x10−12 | MP | UKBB | Both |

| VAMP8 | 1.13x10−12 | FC | UKBB | CardioG |

| FES | 1.39x10−12 | VAF | UKBB | Both |

| MIA3 | 2.56x10−12 | FC | UKBB | Both |

| KIAA1462 | 5.86x10−12 | MAM | UKBB | Both |

| PDGFD | 6.28x10−12 | MAM | UKBB | Both |

| FURIN | 1.07x10−11 | AOR | UKBB | Both |

| MAT2A | 2.33x10−11 | AOR | UKBB | Both |

Figure 5. Heatmap showing 162 candidate causal CAD genes and the tissue(s) in which they exert their causal effect.

Candidate causal genes are shown for the IGA performed using STARNET with UKBB or CARDIoGRAMplusC4D GWASs. Genes are listed alphabetically, and tissue/cell types have been clustered. This is a visual summary of the genes listed in Supplemental Table VII, but also indicates all tissues in which these genes exert their causal effect (Supplemental Tables V and VI).

Of the 163 independent CAD association peaks previously compiled by Erdmann et al,4 56 of these were identified in our IGA as being linked to causal CAD genes (Supplemental Table VIII). While the genes nominated by our IGA were in high agreement with this literature,4 we also identified novel candidate causal genes. For example, at a GWAS peak around rs2022938 the previously attributed gene was HDAC9.4 Our analysis clarified that rather than HDAC9, the adjacent gene TWIST1 is the likely causal CAD gene (Supplemental Table VIII). The reassignment of this GWAS peak from HDAC9 to TWIST1 as the likely causal candidate CAD gene is corroborated by another recent study by Nurnberg et al. conducted in smooth muscle cells.19 Of importance, our IGA also pinpointed the tissue-specificity of the candidate causal genes (Figure 5, Supplemental Table VII). Taking the same example, our IGA found that TWIST1 plays a causal role for CAD in AOR and MAM (Figure 5). Because the predominant cell type in AOR and MAM (i.e. the arterial wall) is smooth muscle cells, this finding adds further corroborative evidence to the study by Nurnberg et al.19

Various potential pathways and aspects of CAD and atherosclerosis were represented by these 162 genes and the corresponding tissues in which they exert their effects. For example, CDKN2B (cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor 2B) residing in the strongest genetic locus for CAD, 9p21.3,20 was the top ranked candidate causal gene for CAD (Table 1). CDKN2B is known to have strong effects on vascular cells,21,22 which is consistent with the single tissue of effect for CDKN2B in this IGA being AOR (Figure 5). Other candidate causal CAD genes that involved only a single tissue included PDE5A (phosphodiesterase type 5A) in AOR, TNF (tumor necrosis factor) in BLOOD, and CCDC97 (coiled-coil domain-containing protein 97) in LIV (Figure 5). Of the 31 genes that were associated with 2 tissue/cell types, 15 were associated with AOR and MAM (with both AOR and MAM being arterial wall) including PDGFD (platelet derived growth factor D), TWIST1 (twist-related protein 1) and PHACTR1 (phosphatase and actin regulator 1), with PHACTR1 being the second top ranked candidate causal gene for CAD (Table 1). Three genes were associated with VAF and SF (both adipose tissue), including SCD (stearoyl-CoA desaturase) and IRS1 (insulin receptor substrate 1). Furthermore, 2 genes were associated with MP and FC (closely related inflammatory cell types), being SMAD3 (mothers against decapentaplegic homolog 3) and MIA3 (MIA SH3 domain ER export factor 3) (Figure 5).

Validation of IGA using an alternate transcriptomic dataset

As further validation we substituted transcriptomic data from GTEx18 for the STARNET dataset that was originally used. Although GTEx contained 48 tissues in its datasets, many of these tissues are unlikely to be related to CAD (e.g. uterus, bladder, esophagus, tibial nerve). Therefore, we only considered the following GTEx tissues that have biologic plausibility for causing CAD: SF, VF, AOR, LIV, SKLM, BLOOD and coronary artery (COR – which was not obtained in STARNET). Note that while GTEx allowed us to include COR, and to also analyze SF, VF, AOR, LIV, SKLM and BLOOD that were all in STARNET, on the other hand GTEx does not have MAM, MP or FC and therefore these tissues/cell types were excluded from this GTEx validation analysis.

Interestingly, when GTEx was used rather than STARNET fewer causal genes were identified, with only 47 candidate causal CAD genes identified with UKBB and GTEx (Supplemental Table IX) and 53 with CARDIoGRAMplusC4D and GTEx (Supplemental Table X). Despite there being less than half the number of candidate causal genes identified when GTEx was used rather than STARNET, many of the candidate causal genes identified using GTEx were also identified using STARNET (Supplemental Table XI).

As stated, unlike STARNET, GTEx includes COR. Using UKBB and GTEx for the IGA, candidate causal CAD genes identified in COR were: THOC5, MRAS, NBEAL1 and PHACTR1 (Supplemental Table IX). As an alternative, using CARDIoGRAMplusC4D and GTEx, candidate causal CAD genes in COR were: SF3A3, FHL3, MRAS, NBEAL1, ADAMTS7, PHACTR1 and INPP5B (Supplemental Table X). Demonstrating the similarity of COR and AOR in their predisposition to atherosclerosis, the majority of these were also identified as candidate causal CAD genes using AOR in STARNET (Supplemental Tables V and VI), with the only exceptions being ADAMTS7 and INPP5B.

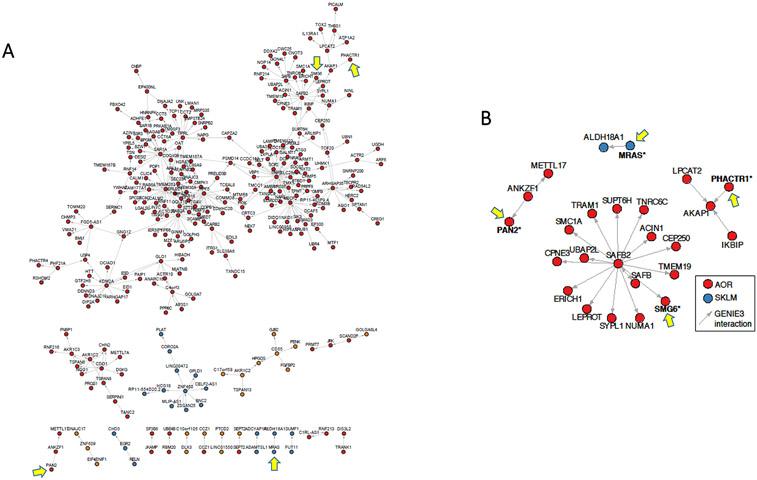

Most candidate causal genes are involved in CAD gene regulatory co-expression networks

To identify potential pathways and mechanisms of how these genes cause CAD, we queried the GRNs that have been inferred from the STARNET datasets.5,11,12,14,15 We focused on identifying GRNs where the tissue of potential causality from the IGA matched the tissue of effect for that gene in the GRN. On this basis, for the 162 candidate causal CAD genes identified in the IGA using STARNET (Figure 5) we found that 144 (144/162 = 88.9%) were represented in at least one GRN, in the same tissue (Figures 6 and 7, Supplemental Table XII).

Figure 6. Key GRNs and inferred regulatory interactions of candidate causal CAD genes.

(A) In STARNET, GRN 154 is a cross-tissue module with 940 genes of which 61.3% are co-expressed in AOR, 31.3% in MAM, 5.6% in SKLM, and <1% each in VAF, SF, BLOOD and LIV. This IGA identified multiple candidate causal CAD genes in this GRN: PAN2, PHACTR1, SMG6, THOC5 (all in AOR), and MRAS in SKLM (Supplemental Table XII). The visualized network shows inferred gene regulatory interactions among key drivers and their related genes of GRN 154, comprising 372 inferred interactions between 281 genes (out of 940). In this GRN, the candidate causal CAD genes (yellow arrows) were found in non-key driver roles. (B) Close-up view of the second-order network neighborhood of PAN2, PHACTR1, SMG6 and MRAS in GRN 154.

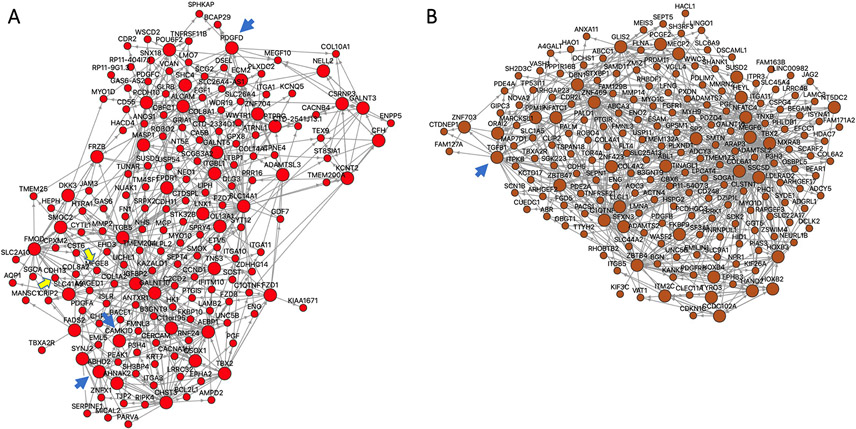

Figure 7. Certain candidate causal CAD genes function as key drivers in GRNs.

(A) STARNET GRN 39, which is exclusively in AOR and contains 182 genes. GRN 39 includes 3 candidate causal CAD genes with a key driver role: ABHD2, CAMK1D, PDGFD, which are each highlighted by a blue arrow (Table 2). In addition, in non-key driver roles GRN 39 includes CDH13 and MFGE8 (Supplemental Table XII), which are highlighted by yellow arrows. (B) STARNET GRN 171, which is exclusively in LIV and contains 200 genes. GRN 171 includes only 1 causal CAD gene with a key driver role, being TGFβ1 (blue arrow) (Table 2). There are no other candidate causal CAD genes in this GRN.

There are 224 GRNs in the current analysis of the STARNET datasets. To ensure that the above finding was not by chance (i.e. that 88.9% of candidate causal genes identified in our IGA are in GRNs), we performed a hypergeometric test for the 224 GRNs tested in relation to the 162 candidate causal genes. In total, there were 9 GRNs that were significantly enriched (FDR < 0.05) for the 162 genes identified by IGA. In contrast, running this analysis using 162 randomly selected genes consistently identified only 0 – 2 significant GRNs.

Candidate causal CAD genes as key drivers in CAD gene regulatory co-expression networks

We also explored which candidate causal CAD genes are key drivers of GRNs. From the 162 candidate causal CAD genes, there were 22 (22/162, 13.6%) that were key drivers in GRN(s) where the tissue of causality in the IGA matched the tissue of effect of that gene in the GRN (Table 2, Figure 7).

Table 2. Candidate causal CAD genes that are also key drivers of a GRN in the same tissue.

Candidate causal CAD genes in this table represent those identified in the IGA performed using STARNET and either UKBB or CARDIoGRAMplusC4D, where the tissue of causality in the IGA is the same tissue where the gene is also a key driver of a GRN. Note that STARNET does not yet have curated GRNs for MP and FC. Therefore this table only considered AOR, MAM, LIV, BLOOD, VAF, SF and SKLM. BMI, body mass index; CAD DGE, the enrichment of differential gene expression in the module between cases and controls; WHR, waist-hip ratio.

| Candidate causal CAD gene |

Causal gene using UKBB or CardioG |

Tissue(s) of effect in IGA |

Tissue in which causal gene is operative in STARNET GRN |

STARNET GRN number |

Number of genes in GRN |

Top phenotypic associations of GRN |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABHD2 | UKBB, CardioG | AOR, MAM | AOR | 39 | 182 | BMI, LDL-C, HDL-C, HBA1C |

| AP000350.5 | UKBB | AOR, LIV, MAM, VAF | VAF | 175 | 569 | BMI, WHR, TG, Chol |

| ARNT | UKBB | BLOOD, SF, VAF | VAF | 36 | 307 | BMI, LDL-C, TG, HBA1C |

| SF | 137 | 299 | BMI, LDL-C, HDH-C, WHR | |||

| ARVCF | UKBB | AOR | AOR | 74 | 124 | LDL-C, HDL-C, BMI, CRP |

| ATP5G1 | CardioG | SKLM, VAF | VAF | 75 | 95 | WHR, TG, HBA1C, CRP |

| CAMK1D | UKBB | AOR | AOR | 39 | 182 | BMI, LDL-C, HDL-C, HBA1C |

| CNNM2 | UKBB, CardioG | MAM | MAM | 191 | 169 | BMI, CRP, LDL-C, HDL-C |

| CTD-3253I12.1 | CG | MAM | MAM | 120 | 795 | CRP, CAD DGE, WHR, BMI |

| DHX58 | UKBB, CardioG | AOR, BLOOD, LIV, MAM, SF, SKLM, VAF | AOR | 139 | 104 | BMI, LDL-C, CRP, TG |

| EIF2B2 | CG | FC, MAM, MP, SF | SF | 198 | 1624 | BMI, WHR, HDL-C, LDL-C |

| FAM192A | CG | AOR, LIV, MAM, SF, SKLM | MAM | 110 | 283 | CRP, LDL-C, BMI, WHR |

| SF | 118 | 214 | CAD DGE, BMI, LDL-C, TG | |||

| FCHO1 | UKBB, CardioG | BLOOD, FC, LIV, MP | BLOOD | 133 | 57 | WHR, TG, Duke, BMI |

| LIPA | UKBB, CardioG | AOR, BLOOD, LIV, MP, SKLM, VAF | VAF | 67 | 98 | BMI, WHR, TG, HBA1C |

| AOR | 150 | 64 | LDL-C, Chol, Duke, BMI | |||

| NT5C2 | UKBB, CardioG | AOR, BLOOD | AOR | 177 | 407 | BMI, LDL-C, HDL-C, Syntax |

| PDGFD | UKBB, CardioG | AOR, MAM | AOR | 39 | 182 | BMI, LDL-C, HDL-C, HBA1C |

| PLTP | CardioG | AOR, SF, VAF | AOR | 122 | 766 | LDL-C, Chol, BMI, Duke |

| REST | UKBB, CardioG | AOR, MAM, MP | AOR | 35 | 223 | HDL-C, LDL-C, CRP, Duke |

| SARS | UKBB, CardioG | LIV, VAF | LIV | 92 | 72 | BMI, WHR, TG, CRP |

| SCD | UKBB | SF, VAF | SF | 78 | 1403 | BMI, HBA1C, WHR, TG |

| STAT2 | UKBB, CardioG | FC, LIV, MP, SF, VAF | SF | 60 | 457 | BMI, LDL-C, HDL-C, WHR |

| TGFβ1 | UKBB, CardioG | LIV, SKLM | LIV | 171 | 200 | LDL-C, BMI, TG, HBA1C |

| THOC5 | UKBB | AOR, LIV, MAM, SF, SKLM, VAF | VAF | 140 | 89 | BMI, LDL-C, WHR, TG |

| SF | 60 | 457 | BMI, LDL-C, HDL-C, WHR |

PHACTR1 is a top causal gene for CAD

CDKN2B and PHACTR1 were the top 2 candidate causal genes for CAD in this study (Table 1). While a great deal of research has been conducted on CDKN2B and the related 9p21.3 locus,20-22 much less is known about PHACTR1. Accordingly, we probed STARNET and the GWASs explored here to gain additional insights on this gene. In STARNET using FDR < 5%, we identified 4 index eQTLs (the best associations for this gene per tissue) for PHACTR1 and 2 further independent but non-index eQTLs by stepwise regression (Table 3). Among these, rs9349379 was an index eQTL for PHACTR1 in both MAM and AOR. Notably, the statistical significance of the index eQTLs at rs9349379 were many orders of magnitude stronger than other eQTLs for PHACTR1 in this analysis (Table 3). Apart from MAM and AOR, there were no eQTLs at rs9349379 for PHACTR1 in any other tissues (at FDR 5%). While there were 3 additional cis-eQTLs at rs9349379 for other genes, at FDR 5% these were of marginal significance (GFOD1 in AOR, Padj = 0.047; AL008729.2 in BLOOD, Padj = 0.0003; AL008729.2 in SF, Padj = 0.02). Importantly, rs9349379 is a common SNP in the third intron of the PHACTR1 gene, and was found to be associated with risk of CAD in both UKBB data1 and CARDIoGRAMplusC4D.2 Furthermore, we found no SNPs in proximity to rs9349379 that are in linkage disequilibrium with rs9349379 itself. Taken as a whole, these results indicate that rs9349379 is likely to be the causal PHACTR1-associated SNP, and that the CAD-causal effects of rs9349379 and PHACTR1 arise in the arterial wall (i.e. AOR, MAM and COR in our analyses).

Table 3. Genome-wide significant eQTLs involving PHACTR1.

At genome-wide significance, four lead eQTLs for PHACTR1 were identified (the best associations for this gene per tissue), with stepwise regression revealing 2 additional non-lead eQTLs.

| Tissue | Locus | Location on chromosome 6 |

P value | Beta |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lead eQTLs | ||||

| Aorta | rs9349379 | 12903725 | 9.37 x 10−17 | 0.49 |

| Internal Mammary Artery | rs9349379 | 12903725 | 1.95 x 10−56 | 0.86 |

| Blood | rs413120 | 13280409 | 1.8 x 10−8 | 0.41 |

| Subcutaneous Adipose | rs386406198 | 13060791 | 3.63 x 10−8 | 0.45 |

| Non-lead eQTLs | ||||

| Aorta | rs6458568 | 12961440 | 1.33 x 10−9 | |

| Subcutaneous Adipose | rs20499 | 13294772 | 5.09 x 10−5 | |

PHACTR1 is known to have multiple isoforms. To understand which are potentially the most important for causing CAD, we queried STARNET for isoform-specific eQTLs of PHACTR1 at rs9349379 (thereby avoiding the need to correct for multiple comparisons). As shown in Supplemental Table XIII, we identified 15 isoform-specific eQTLs for PHACTR1 at rs9349379, with 13 of these being in AOR or MAM. Interestingly, these eQTLs coded for both protein and non-protein coding PHACTR1 isoforms. However, the strongest eQTLs to emerge, and thus by inference the strongest causal candidate isoforms for CAD, were PHACTR1 isoforms 201, 206 and 207.

DISCUSSION

The pathobiology of CAD and atherosclerosis are profoundly complex, but until now there have been few insights as to which causal mechanisms are most important. This study directly addressed this concern and developed an IGA pipeline that provided a prioritized list of candidate causal CAD genes, and the tissues in which these genes exert their effect. This will enable a sharp refocusing of research efforts, both with respect to which genes are most critical for causing CAD and also where their effects are mediated.

Our IGA pipeline (Figure 1) integrated large eQTL and GWAS datasets. Several methods can be applied for this purpose, which belong to two broad classes.8 Class 1 includes TWAS, MetaXcan and SMR, while class 2 includes Coloc and eCAVIAR (only MetaXcan, SMR and Coloc were used in this study). It has been reported that the results of these classes do not fully overlap,23 which was corroborated by our study. Accordingly, our methodology was conservative, requiring candidate causal genes to be identified both using Coloc and either MetaXcan or SMR. While this likely led to the exclusion of additional causal genes that did not meet these conservative criteria, as the first systematic CAD IGA it provided assurance that the candidate causal genes identified are valid and correct. Furthermore, when our IGA pipeline was applied to different GWAS datasets (UKBB versus CARDIoGRAMplusC4D) or different eQTL datasets (STARNET versus GTEx), the results were comparable. Presumably, any differences in the candidate causal genes identified between these alternate datasets were related to differences between the subjects enrolled and their demographic features. However, another difference was that STARNET samples were from living subjects undergoing coronary artery bypass surgery and that after procurement these samples were immediately placed into solutions to stabilize RNA.12 Conversely, GTEx samples18 were obtained at autopsy, and additional factors such as end-of-life treatment modality,24 sequencing contamination,25 and other technical factors have been shown to influence gene expression in this dataset.24,25

As one of the main readouts of this IGA, we prioritized candidate causal CAD genes based on the smallest P value for the class 1 analyses (MetaXcan or SMR) (Table 1 and Supplemental Table VII). This is important to consider, because it means the prioritization was on the basis of the strengths of the correlations between the eQTL and GWAS results. While this gives assurance that the top ranked genes have very robust statistical associations to support their causal status, it does not imply that the top genes are those with the strongest effect on CAD. Ranking the strength of effect on CAD for the hundreds of genes identified by GWAS, across multiple different tissues, will be a major undertaking that might require added layers of data to be considered such as burden of CAD, the role of gene enhancer or promoter elements,26 and other aspects. At the present time we are not aware that this has been attempted using GWAS and other large-scale datasets.

While we believe our study is the first systematic, large-scale IGA for CAD, it is important to acknowledge a recent study that undertook a more restricted analysis for the association of 51 loci with CAD based on evidence from experimental and in silico studies, but which also included an SMR analysis using GTEx.27 While the analytic strategy was very different from that applied here, a likely causal gene was identified for 36 of 51 loci, and several genes were validated as being potentially causal for CAD across that study and ours, including PHACTR1, FURIN, IL6R, LPL, LIPA, MRAS, KIAA1462 (also known as JCAD), GUCY1A3, SH2B3 and PDGFD.27

It was reassuring in our study that CDKN2B was one of the top two candidate causal genes (Table 1). This is consistent with CDKN2B being among the closest coding genes to the 9p21.3 CAD risk locus and that the 9p21.3 locus influences CDKN2B expression.28 In turn, 9p21.3 is known to be a powerful common genetic risk factor for CAD.20 Our finding that CDKN2B is only potentially causal for CAD in AOR corroborates previous studies in mice21 and in humans whereby regulatory elements in coronary artery smooth muscle cells were linked to CDKN2B expression.22 These findings should guide research efforts to focus on the effects of this gene and the 9p21.3 CAD risk locus in the arterial wall, while other candidate genes at 9p21 (e.g. CDKN2A or long non-coding RNA ANRIL) may still exert causal effects at the epigenetic or post-transcriptional levels.29

Our results prioritized PHACTR1 as the other of the top two candidate causal CAD genes. As a CAD risk locus with largely unknown function, rs9349379, which resides in the 3rd intron of the PHACTR1 gene, had already emerged as likely having a critical role in vascular pathobiology.1,2,11,30 Our results extend the knowledge-base regarding rs9349379 and PHACTR1, showing that PHACTR1 is a likely causal gene for CAD and that this causality is most likely to be mediated through the arterial wall. Furthermore, our study highlights the profound complexity of rs9349379 in terms of its regulation of the expression levels (i.e. eQTLs) of at least 10 PHACTR1 isoforms, which include protein coding and non-coding isoforms (Supplemental Table XIII). Despite these complexities, it is clear given its ranking as among the top candidate causal CAD genes, that redoubled research efforts on PHACTR1 are justified and urgently needed.

Many other novel findings emerged from this analysis. For example, after PHACTR1 and CDKN2B, two of the next most significant candidate causal CAD genes were TBC1D7 (causal in AOR and MAM) and GFOD1 (causal in MAM) (Table 1). Apart from the fact that they have been associated with CAD through GWAS,1,2 almost nothing is known about how these genes might be causal for CAD. Our study localized the tissue of likely causality to the arterial wall for both these genes. Furthermore, both genes are involved in GRNs; GFOD1 in STARNET GRN 82 and TBC1D7 in STARNET GRNs 167 and 217 (Supplemental Table XII).

As another novel finding, our study found that most candidate causal CAD genes were in CAD GRNs, but only a minority were key drivers (Table 2). The fact that only a minority of candidate causal genes were GRN key drivers is consistent with our understanding of how gene networks and their key drivers cause disease. A leading explanation is that hub nodes (governed by key drivers) tend to be essential for life and are evolutionarily conserved, and that ‘disease genes’ do not typically encode hubs.31 Nonetheless, for the 22 candidate causal CAD genes that were found to be key drivers (Table 2), the mechanism of CAD causality appears to be at least partially evident via their key driver role in modulating the effects of those GRNs. For other candidate causal genes it appears plausible that some participate in GRNs but in a non-key driver role. While elucidating the precise mechanisms of effect of all causal CAD genes is beyond the scope of the present study, the many network associations of these candidate causal genes (Table 2, Supplemental Table XII) is an important starting point for future research efforts.

There are certain limitations of this study. Firstly, IGA methodologies for integrating GWAS and eQTL data continue to evolve, and with further improvements to these methodologies the causal gene list for CAD could be refined. Secondly, we used STARNET as our main transcriptomic dataset, with GTEx as a validation dataset. Because it collected samples from living individuals, STARNET does not include coronary artery samples, rather the arterial samples collected in STARNET were the atherosclerosis-prone AOR and pre/early-atherosclerotic MAM. As CAD is characterized by atherosclerotic plaques in coronary arteries, atherosclerotic aortic tissue might not be the ideal arterial tissue to study CAD. However, since atherosclerosis is a systemic disease, AOR should reflect ongoing disease patterns in differing vascular beds. Furthermore, GTEx does not contain MAM, MP or FC – therefore these tissues/cells could not be included in the validation analyses. In addition, both STARNET and GTEx used bulk (whole tissue) RNA sequencing, and did not use state-of-the-art single cell RNA sequencing. Hopefully, future large-scale efforts to create CAD-relevant single cell transcriptomic datasets will bring even greater clarity to the causal genes and cell types for CAD and other diseases. As another possible limitation, CAD was defined differently across STARNET and the GWAS datasets. STARNET applied a rigorous definition using coronary angiography, and CAD cases were those with severe CAD requiring coronary artery bypass graft surgery.11,12 In contrast, for the UKBB dataset a “soft” but inclusive CAD definition was used that incorporated self-reported angina or other evidence of chronic coronary disease, but also including more stringently defined phenotypes such as myocardial infarction and/or revascularization.1 Similarly, the CARDIoGRAMplusC4D GWAS dataset also used an inclusive definition of CAD (see Supplemental Table I).2 The impact of these differing definitions on this study is unknown, although, the fact that STARNET applied a stringent CAD definition provides reassurance of the validity of our findings.

In conclusion, we developed an informatics pipeline and thus conducted a large-scale IGA of GWAS and transcriptomic data using advanced computational methods to generate a refined list of candidate causal genes for CAD, which also localizes the tissue of causal effect. These results should serve as an important resource, facilitating the focusing of research efforts toward the most powerful causal CAD genes, and to the tissues and mechanisms that are most critical for that causal effect.

Supplementary Material

SOURCES OF FUNDING

Ke Hao acknowledges support from NIH (1R01ES029212-01). Clint Miller acknowledges support from NIH (R01HL148239, R00HL125912) and Fondation Leducq. Johan Björkegren acknowledges support from NIH R01HL125863, Swedish Research Council (2018-02529) and Heart Lung Foundation (20170265), Foundation Leducq (PlaqueOmics, 18CVD02; and CADgenomics, 12CVD02]) and Astra-Zeneca. Jason Kovacic acknowledges support from NIH (R01HL130423, R01HL135093, R01HL148167-01A1), New South Wales health grant RG194194 and the Bourne Foundation.

NON-STANDARD ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS

- AOR

aorta

- BLOOD

venous blood

- COR

coronary artery

- CAD

coronary artery disease

- eQTL

expression quantitative trait loci

- FC

foam cell(s)

- GWAS

genome-wide association studies

- GRN

gene regulatory co-expression network

- GTEx

Genotype-Tissue Expression (project)

- IGA

integrative genomics analysis

- LDSC

linkage disequilibrium score regression

- LIV

liver

- MAM

internal mammary artery

- MP

macrophage(s)

- SF

subcutaneous fat

- SKLM

skeletal muscle

- SMR

summary-based Mendelian randomization

- SNP

single nucleotide polymorphism

- STARNET

Stockholm-Tartu Atherosclerosis Reverse Network Engineering Task

- TWAS

transcriptome-wide association study

- UKBB

UK Biobank

- VF

visceral fat

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

Johan Bjorkegren and Arno Ruusalepp are shareholders in Clinical Gene Network AB that has an invested interest in STARNET. The remaining authors have nothing to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Nelson CP, Goel A, Butterworth AS, Kanoni S, Webb TR, Marouli E, Zeng L, Ntalla I, Lai FY, Hopewell JC, et al. Association analyses based on false discovery rate implicate new loci for coronary artery disease. Nat Genet. 2017;49:1385–1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nikpay M, Goel A, Won HH, Hall LM, Willenborg C, Kanoni S, Saleheen D, Kyriakou T, Nelson CP, Hopewell JC, et al. A comprehensive 1,000 Genomes-based genome-wide association meta-analysis of coronary artery disease. Nat Genet. 2015;47:1121–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bjorkegren JL, Kovacic JC, Dudley JT and Schadt EE. Genome-wide significant loci: how important are they? Systems genetics to understand heritability of coronary artery disease and other common complex disorders. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65:830–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Erdmann J, Kessler T, Munoz Venegas L and Schunkert H. A decade of genome-wide association studies for coronary artery disease: the challenges ahead. Cardiovasc Res. 2018;114:1241–1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ma L, Chandel N, Ermel R, Sukhavasi K, Hao K, Ruusalepp A, Bjorkegren JLM and Kovacic JC. Multiple independent mechanisms link gene polymorphisms in the region of ZEB2 with risk of coronary artery disease. Atherosclerosis. 2020;311:20–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burgess S, Butterworth A and Thompson SG. Mendelian randomization analysis with multiple genetic variants using summarized data. Genet Epidemiol. 2013;37:658–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhu Z, Zhang F, Hu H, Bakshi A, Robinson MR, Powell JE, Montgomery GW, Goddard ME, Wray NR, Visscher PM, et al. Integration of summary data from GWAS and eQTL studies predicts complex trait gene targets. Nat Genet. 2016;48:481–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barbeira AN, Dickinson SP, Bonazzola R, Zheng J, Wheeler HE, Torres JM, Torstenson ES, Shah KP, Garcia T, Edwards TL, et al. Exploring the phenotypic consequences of tissue specific gene expression variation inferred from GWAS summary statistics. Nature communications. 2018;9:1825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giambartolomei C, Vukcevic D, Schadt EE, Franke L, Hingorani AD, Wallace C and Plagnol V. Bayesian test for colocalisation between pairs of genetic association studies using summary statistics. PLoS Genet. 2014;10:e1004383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zheng J, Baird D, Borges MC, Bowden J, Hemani G, Haycock P, Evans DM and Smith GD. Recent Developments in Mendelian Randomization Studies. Curr Epidemiol Rep. 2017;4:330–345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Franzen O, Ermel R, Cohain A, Akers NK, Di Narzo A, Talukdar HA, Foroughi-Asl H, Giambartolomei C, Fullard JF, Sukhavasi K, et al. Cardiometabolic risk loci share downstream cis- and trans-gene regulation across tissues and diseases. Science. 2016;353:827–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zeng L, Talukdar HA, Koplev S, Giannarelli C, Ivert T, Gan LM, Ruusalepp A, Schadt EE, Kovacic JC, Lusis AJ, et al. Contribution of Gene Regulatory Networks to Heritability of Coronary Artery Disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73:2946–2957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Michelis KC, Nomura-Kitabayashi A, Lecce L, Franzen O, Koplev S, Xu Y, Santini MP, D'Escamard V, Lee JTL, Fuster V, et al. CD90 Identifies Adventitial Mesenchymal Progenitor Cells in Adult Human Medium- and Large-Sized Arteries. Stem cell reports. 2018;11:242–257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hartman RJG, Owsiany K, Ma L, Koplev S, Hao K, Slenders L, Civelek M, Mokry M, Kovacic JC, Pasterkamp G, et al. Sex-Stratified Gene Regulatory Networks Reveal Female Key Driver Genes of Atherosclerosis Involved in Smooth Muscle Cell Phenotype Switching. Circulation. 2021;143:713–726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cohain AT, Barrington WT, Jordan DM, Beckmann ND, Argmann CA, Houten SM, Charney AW, Ermel R, Sukhavasi K, Franzen O, et al. An integrative multiomic network model links lipid metabolism to glucose regulation in coronary artery disease. Nature communications. 2021;12:547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stunnenberg HG, International Human Epigenome C and Hirst M. The International Human Epigenome Consortium: A Blueprint for Scientific Collaboration and Discovery. Cell. 2016;167:1145–1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen L, Ge B, Casale FP, Vasquez L, Kwan T, Garrido-Martin D, Watt S, Yan Y, Kundu K, Ecker S, et al. Genetic Drivers of Epigenetic and Transcriptional Variation in Human Immune Cells. Cell. 2016;167:1398–1414 e24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.GTEx Consortium. Human genomics. The Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) pilot analysis: multitissue gene regulation in humans. Science. 2015;348:648–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nurnberg ST, Guerraty MA, Wirka RC, Rao HS, Pjanic M, Norton S, Serrano F, Perisic L, Elwyn S, Pluta J, et al. Genomic profiling of human vascular cells identifies TWIST1 as a causal gene for common vascular diseases. PLoS Genet. 2020;16:e1008538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gransbo K, Almgren P, Sjogren M, Smith JG, Engstrom G, Hedblad B and Melander O. Chromosome 9p21 genetic variation explains 13% of cardiovascular disease incidence but does not improve risk prediction. J Intern Med. 2013;274:233–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Visel A, Zhu Y, May D, Afzal V, Gong E, Attanasio C, Blow MJ, Cohen JC, Rubin EM and Pennacchio LA. Targeted deletion of the 9p21 non-coding coronary artery disease risk interval in mice. Nature. 2010;464:409–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller CL, Pjanic M, Wang T, Nguyen T, Cohain A, Lee JD, Perisic L, Hedin U, Kundu RK, Majmudar D, et al. Integrative functional genomics identifies regulatory mechanisms at coronary artery disease loci. Nature communications. 2016;7:12092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peng S, Deyssenroth MA, Di Narzo AF, Cheng H, Zhang Z, Lambertini L, Ruusalepp A, Kovacic JC, Bjorkegren JLM, Marsit CJ, et al. Genetic regulation of the placental transcriptome underlies birth weight and risk of childhood obesity. PLoS Genet. 2018;14:e1007799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McCall MN, Illei PB and Halushka MK. Complex Sources of Variation in Tissue Expression Data: Analysis of the GTEx Lung Transcriptome. American journal of human genetics. 2016;99:624–635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nieuwenhuis TO, Yang SY, Verma RX, Pillalamarri V, Arking DE, Rosenberg AZ, McCall MN and Halushka MK. Consistent RNA sequencing contamination in GTEx and other data sets. Nature communications. 2020;11:1933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boix CA, James BT, Park YP, Meuleman W and Kellis M. Regulatory genomic circuitry of human disease loci by integrative epigenomics. Nature. 2021;590:300–307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shadrina AS, Shashkova TI, Torgasheva AA, Sharapov SZ, Klaric L, Pakhomov ED, Alexeev DG, Wilson JF, Tsepilov YA, Joshi PK, et al. Prioritization of causal genes for coronary artery disease based on cumulative evidence from experimental and in silico studies. Sci Rep. 2020;10:10486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lo Sardo V, Chubukov P, Ferguson W, Kumar A, Teng EL, Duran M, Zhang L, Cost G, Engler AJ, Urnov F, et al. Unveiling the Role of the Most Impactful Cardiovascular Risk Locus through Haplotype Editing. Cell. 2018;175:1796–1810 e20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Holdt LM and Teupser D. Long Noncoding RNA ANRIL: Lnc-ing Genetic Variation at the Chromosome 9p21 Locus to Molecular Mechanisms of Atherosclerosis. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2018;5:145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gupta RM, Hadaya J, Trehan A, Zekavat SM, Roselli C, Klarin D, Emdin CA, Hilvering CRE, Bianchi V, Mueller C, et al. A Genetic Variant Associated with Five Vascular Diseases Is a Distal Regulator of Endothelin-1 Gene Expression. Cell. 2017;170:522–533 e15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barabasi AL, Gulbahce N and Loscalzo J. Network medicine: a network-based approach to human disease. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12:56–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moore KJ, Koplev S, Fisher EA, Tabas I, Bjorkegren JLM, Doran AC and Kovacic JC. Macrophage Trafficking, Inflammatory Resolution, and Genomics in Atherosclerosis: JACC Macrophage in CVD Series (Part 2). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72:2181–2197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dobin A, Davis CA, Schlesinger F, Drenkow J, Zaleski C, Jha S, Batut P, Chaisson M and Gingeras TR. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:15–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shabalin AA. Matrix eQTL: ultra fast eQTL analysis via large matrix operations. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:1353–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Talukdar HA, Foroughi Asl H, Jain RK, Ermel R, Ruusalepp A, Franzen O, Kidd BA, Readhead B, Giannarelli C, Kovacic JC, et al. Cross-Tissue Regulatory Gene Networks in Coronary Artery Disease. Cell Syst. 2016;2:196–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Langfelder P and Horvath S. WGCNA: an R package for weighted correlation network analysis. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9:559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huynh-Thu VA, Irrthum A, Wehenkel L and Geurts P. Inferring regulatory networks from expression data using tree-based methods. PLoS One. 2010;5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Arneson D, Bhattacharya A, Shu L, Makinen VP and Yang X. Mergeomics: a web server for identifying pathological pathways, networks, and key regulators via multidimensional data integration. BMC Genomics. 2016;17:722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shannon P, Markiel A, Ozier O, Baliga NS, Wang JT, Ramage D, Amin N, Schwikowski B and Ideker T. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome research. 2003;13:2498–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Finucane HK, Bulik-Sullivan B, Gusev A, Trynka G, Reshef Y, Loh PR, Anttila V, Xu H, Zang C, Farh K, et al. Partitioning heritability by functional annotation using genome-wide association summary statistics. Nat Genet. 2015;47:1228–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hormozdiari F, Gazal S, van de Geijn B, Finucane HK, Ju CJ, Loh PR, Schoech A, Reshef Y, Liu X, O'Connor L, et al. Leveraging molecular quantitative trait loci to understand the genetic architecture of diseases and complex traits. Nat Genet. 2018;50:1041–1047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ehret GB, Ferreira T, Chasman DI, Jackson AU, Schmidt EM, Johnson T, Thorleifsson G, Luan J, Donnelly LA, Kanoni S, et al. The genetics of blood pressure regulation and its target organs from association studies in 342,415 individuals. Nat Genet. 2016;48:1171–1184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Myers TA, Chanock SJ and Machiela MJ. LDlinkR: An R Package for Rapidly Calculating Linkage Disequilibrium Statistics in Diverse Populations. Front Genet. 2020;11:157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.