Abstract

A series of four lactose-modified BODIPY photosensitizers (PSs) with different substituents (-I, -H, -OCH3, and -NO2) in the para-phenyl moiety attached to the meso-position of the BODIPY core were synthesized; the photophysical properties and photodynamic anticancer activities of these sensitizers were investigated, focusing on the electronic properties of the different substituent groups. Compared to parent BODIPY H, iodine substitution (BODIPY I) enhanced the intersystem crossing (ISC) to produce singlet oxygen (1O2) due to the heavy atom effect, and maintained a high fluorescence quantum yield (ΦF) of 0.45. Substitution with the electron-donating methoxy group (BODIPY OMe) results in a significant perturbation of occupied frontier molecular orbitals and consequently achieves higher 1O2 generation capability with a high ΦF of 0.49, while substitution with the electron-withdrawing nitro group (BODIPY NO2) led a perturbation of unoccupied frontier molecular orbitals and induces a forbidden dark S1 state, which is negative for both fluorescence and 1O2 generation efficiencies. The BODIPY PSs formed water-soluble nanoparticles (NPs) functionalized with lactose as liver cancer-targeting ligands. BODIPY I and OMe NPs showed good fluorescence imaging and PDT activity against various tumor cells (HeLa and Huh-7 cells). Collectively, the BODIPY NPs demonstrated high 1O2 generation capability and ΦF may create a new opportunity to develop useful imaging-guided PDT agents for tumor cells.

Subject terms: Chemistry, Materials science

Introduction

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) is a promising cancer treatment that has been applied to various cancers, such as oral, lung, bladder, brain, ovarian, and esophageal cancers1–3. The PDT process requires three key components: light, oxygen, and a photosensitizing agent4,5. In the presence of external light, the photosensitizer (PS) is photoexcited to the optically allowed S1 state and then energetically relaxed to the T1 state via intersystem crossing (ISC). The triplet excited PS can transfer the excitation energy to ground-state triplet oxygen (type II), resulting in cytotoxic reactive oxygen species (ROS), such as singlet oxygen (1O2), which directly kills tumor cells6–9. PDT can provide good selectivity and is non-invasive at the treatment region as the activity of this medical technique is only carried out when the PS is combined with light of a particular wavelength10. Recently, imaging-guided PDT has been assessed to develop specific agents for visualizing individual tumor targets, thereby enhancing therapeutic efficiency and reducing side effects11–13. However, to date, PSs that can be simultaneously applied for both imaging and treatment are not available in the clinic. Accordingly, there is an urgent need to develop PSs that can effectively produce both fluorescence and ROS14,15.

Among the different PSs, 4, 4-difluoro-4-bora-3a,4a-diaza-s-indacene (BODIPY) is a new family of fluorescent dyes with outstanding photophysical features, such as high molar extinction coefficient, high quantum efficiencies of fluorescence, and easy electronic modification of frontier molecular orbitals by substituents. BODIPYs have thus been applied as promising imaging/detection agents with high light-to-dark toxicity ratios16–19. Many dyes with a high ISC obtained from natural or synthetic sources have been employed in PDT reactions20,21. The most common design strategy employed to enhance ISC efficiency is the conjugation of heavy halogen atoms (Br or I) to promote spin–orbit coupling (SOC), which improves the 1O2 generation capability and the population of longer-lived excited triplet states22,23. However, the incorporation of heavy halogen atoms causes toxicity and fluorescence quenching24–26. Therefore, BODIPY PSs without heavy halogen atoms are preferred as theranostic agents.

Several approaches with heavy-atom-free PSs to improve the ISC, such as the use of dimer BODIPY27,28, spin converters29, and photoinduced electron transfer (PeT)30,31, have recently been reported. The formation of triplet states via photoinduced electron transfer (PeT) is a well-known process that was not employed to develop practical triplet sensitizers until recently32. The charge-transfer (CT) states comprised the donor radical cation and the acceptor radical anion are induced by PeT, which recombines the ground state via different pathways31,33,34. Owing to the different polarity between locally-excited (LE) and CT states, their relative energy levels are strongly affected by the polarity of medium and accordingly the energy relaxation dynamics much complicated. For example, in non-polar solvents, the energy level of polar CT state is usually higher than that of the LE state, resulting in very low PeT efficiency and intense fluorescence from the LE state. In contrast, for solvents with sufficient polarity, such as in an aquatic environment, the CT state is energetically mush stabilized and thus its energy level can be low lying compared to that of the LE state, causing effective PeT and ISC35.

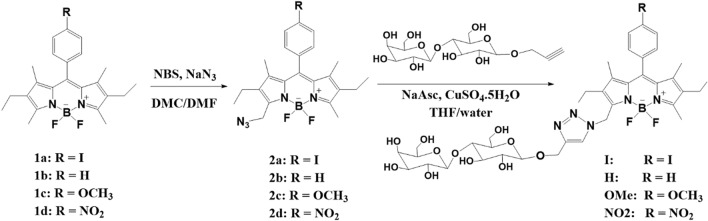

Recently, we reported a series of water-soluble BODIPY PSs attached to heavy atoms at the 2,6-position of the BODIPY core24. These BODIPY PSs showed excellent PDT ability, while exhibiting very low dark toxicity; however, they could not be used as imaging reagents due to their low fluorescence quantum yield (ΦF) resulting from the incorporation of heavy atoms. To overcome the above-mentioned issues, we aim to develop bifuntional heavy-atom-free BODIPY PSs with imaging-guided PDT properties. Herein, we present a new family of heavy-atom-free BODIPY nanoparticles (NPs) (Fig. 1) with potential applications in tumor-targeted fluorescence cell imaging and PDT. We synthesized four BODIPY PSs containing different substituent groups (-I, -H, -OCH3, and -NO2) in the para-phenyl moiety attached to the meso-position of the BODIPY core, and investigated their photophysical and photosensitizing properties according to the variation in the substituents. Among the BODIPY PSs, we used BODIPY H as an internal reference to compare the fluorescence and PDT efficiencies without substituent. In addition, BODIPY segments were connected with lactose-tethering triazole as a specific ligand for asialoglycoprotein (ASGP) in liver cancer cells36. The resulting BODIPY PSs formed NPs with a uniform size in water. Further, the cell viability, cellular imaging, and photodynamic anticancer activities of these BODIPY NPs were evaluated using HeLa and Huh-7 cells. Overall, our findings indicate that BODIPY NPs are promising tumor-targeted PDT agents, with fluorescence cell imaging properties in live cancer cell lines.

Figure 1.

The preparation of lactose-functionalized BODIPY PSs with various meso-phenyl substituents.

Results and discussion

Synthesis and photophysical characterization of BODIPY NPs

The process used to synthesize the four BODIPY PSs (I, H, OMe, and NO2) functionalized with lactose-tethering triazole is outlined in Fig. 1. The detailed procedure is provided in the Supporting Information section.

Compounds 1a–d were synthesized via condensation reactions using 3-ethyl-2, 4-dimethyl pyrrole with 4-iodobenzoyl chloride and benzaldehyde derivatives, which yielded compounds 1a and 1b–d, respectively. Compounds 2a–d modified with alkyl azide at the 3-methyl position of the BODIPY core were obtained in the same manner37. Cu(I)-catalyzed alkyne–azide cycloaddition reactions (CuAAC) were performed with compounds 2a-d and propargyl lactoside to obtain the final compounds BODIPY I, H, OMe, and NO2, respectively. The final BODIPY PSs were fully characterized by 1H, 13C NMR, and HR-MS, as shown in Fig. S8 -27.

A series of water-dispersible NPs, namely I-NPs, H-NPs, OMe-NPs, and NO2-NPs, were obtained from the corresponding BODIPY PSs I, H, OMe, and NO2 in aqueous solution, respectively, after complete evaporation of tetrahydrofuran (THF).

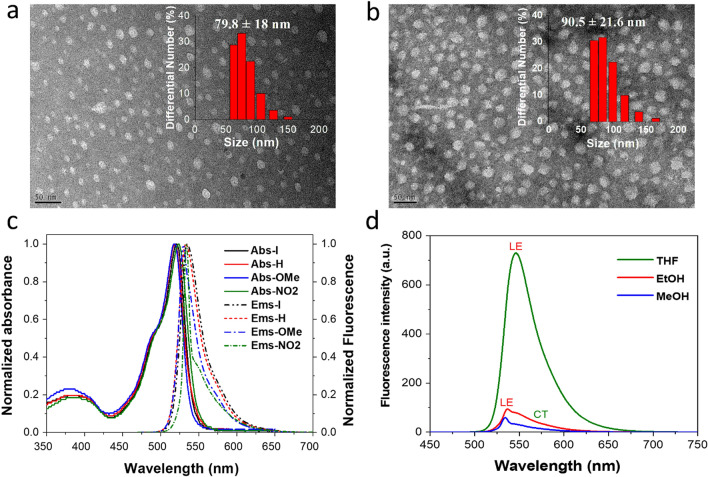

The hydrodynamic diameters of the obtained BODIPY NPs in aqueous solution were determined using dynamic light scattering (DLS) measurements. As shown in Fig. 2a,b and Figure S1, the average diameters of the H, I, OMe, and NO2-NPs were approximately 71.3, 79.8, 90.5, and 100.7 nm, respectively. The morphology and size of BODIPY NPs were also examined by transmission electron microscopy (TEM), which revealed their spherical morphology and average diameter of approximately 20–30 nm (Figs. 2a and b). Notably, the size of the fully hydrated BODIPY NPs as measured by DLS might be larger than that determined in the dried state from TEM. Many water molecules seem to be entrapped within the BODIPY NPs via interactions with hydrophilic lactose segments.

Figure 2.

Characterization of BODIPY PSs. TEM images of I-NPs (a) and OMe-NPs (b) (the scale bar: 50 nm). The inset images indicate the sizes of I-NPs and OMe-NPs based on DLS. The normalized absorption and emission spectra of I, H, OMe, and NO2 in methanolic solution at c = 5 µM (c). The emission spectra of BODIPY NO2 in various solvents at c = 5 µM (d). The solutions were excited at 490 nm.

Figure 2c shows the absorption and fluorescence spectra of the BODIPY PSs in methanol. All of the synthesized BODIPY PSs exhibit typical two absorption bands, with a robust S0 → S1 (π → π*) transition band around 518–524 nm, an extinction coefficient of 42,400–49,500 M-1·cm-1 from the boradiazaindacene chromophore38,39, and a weak broad band around 350–400 nm corresponding to the S0 → S2 (π → π*) transition, which can be attributed to the out-of-plane vibrations of the aromatic skeleton37,40. The iodine (-I) and methoxy (-OCH3) substituents incorporated into the meso-phenyl of BODIPY resulted in almost the same absorption and emission spectra as BODIPY H, indicating that these substituents have a negligible effect on the photophysical properties of the BODIPY cores37. The BODIPY dyes with H, I, and OMe exhibited a high ΦF of approximately 0.45–0.51 (Table 1), which is usually recorded for BODIPY derivatives37. Of note, the values of ΦF remained high despite the BODIPY dyes being modified with the lactose-tethering triazole and iodine substituent24,41. However, the nitro substituent (-NO2) appeared to have a more significant influence on the photophysical properties of the BODIPY dye. Although the absorption spectrum of BODIPY NO2 is similar to those of the other BODIPY PSs, its fluorescence quantum yield is largely reduced (Table 1) as well as its fluorescence intensity and spectral shape are strongly affected by the solvent polarity (Fig. 2d). In aqueous solution, BODIPY I, H, and OMe-NPs exhibited absorption and emission maxima (λabs/λem) at around 515/538 nm while the fluorescence of NO2-NPs was quenched (Figure S7).

Table 1.

The photophysical and photosensitizing properties of BODIPY I, H, OMe, and NO2 in MeOH.

| I | H | OMe | NO2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| λab (nm)a | 522 | 518 | 520 | 524 |

| λem (nm)a | 535 | 533 | 530 | 534 |

| ɛ (103 M-1 cm-1)a | 45.2 | 42.4 | 44.3 | 49.5 |

| ΦF b | 0.45 | 0.51 | 0.49 | 0.014 |

| ΦΔc | 0.1 | 0.037 | 0.073 | 0.009 |

As shown in Table S1, the emission intensities and ΦF of NO2 were largely quenched in protic polar solvents, exhibiting ΦF of 0.035 in ethanol and 0.014 in methanol compared with 0.38 in THF. The intense emission observed in THF corresponds to the fluorescence from the local excited (LE) state of the BODIPY subunit. In contrast, fluorescence is largely quenched in a polar methanol solution, owing to a nearly non-emissive CT state44. This phenomenon is expected because the population of non-emissive CT state by PeT mechanism competes with that of emissive LE state30,33,34. Details of the photophysical studies are presented in the theoretical calculation section.

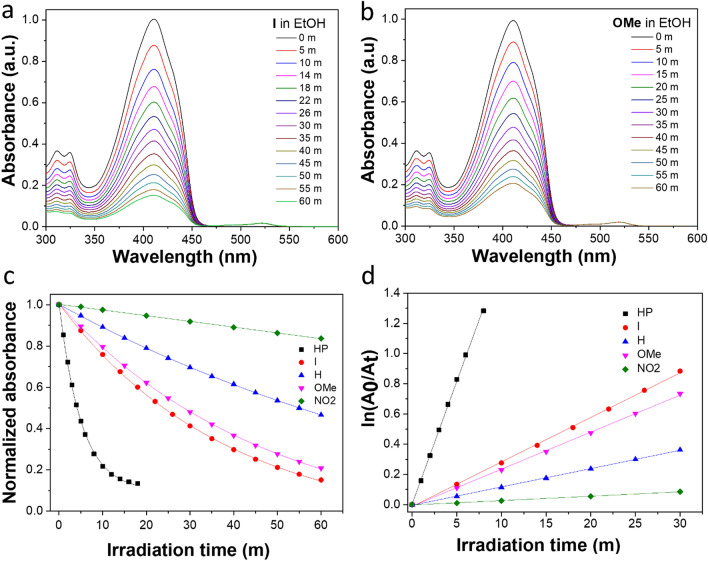

Singlet oxygen generation

The singlet oxygen (1O2) generation capabilities of I, H, OMe, and NO2 were assessed in air-saturated ethanol under irradiation at 520 nm. A commercial 1O2 probe, 1,3-diphenylisobenzofuran (DPBF), was used as an indicator, and hematoporphyrin (HP) in EtOH was used as the reference (ΦΔ = 0.53)45.

As shown in Figs. 3a–c and S3, the absorbance of DPBF at 414 nm decreased gradually in the presence of the BODIPY dyes under continuous light irradiation. According to the linear relationship of the decay curves (Fig. 3d), the 1O2 quantum yields (Φ△) of I, H, OMe, and NO2 were assigned as 0.1, 0.037, 0.073, and 0.009, respectively (Table 1). Thus, the most robust 1O2 generation ability of I among the series of PS suggested that the additional heavy iodine atom on the meso-phenyl of BODIPY induced spin–orbit perturbations on the molecules and significantly influenced its superior capability to generate singlet oxygen, as shown by the faster reducing rate of DPBF absorbance bands and a higher Φ△ than that of the other BODIPY PSs. However, the incorporation of the electron-donating group (-OCH3) at the meso-phenyl of BODIPY played an essential role in enhancing the 1O2 generation of OMe. In contrast, the introduction of a strong electron-withdrawing group (-NO2) did not lead to an efficient Φ△ of BODIPY NO2 in a polar solvent (ethanolic solution). However, as shown in Figure S4a, Φ△ could be enhanced to 0.03 in a less polar solvent (THF). Such finding indicates that the triplet state of BODIPY NO2 is strongly affected by the polarity of the media (the details are presented in the theoretical calculation). These results collectively indicate that both iodinated- meso-phenyl BODIPY I and heavy-free atom BODIPY OMe achieved an elevated 1O2 under LED illumination that facilitated singlet oxygen generation, demonstrating their potential use as efficient photosensitizers for PDT.

Figure 3.

The singlet oxygen (1O2) generation capabilities of BODIPY PSs. Absorption spectra of DPBF upon irradiation in the presence of (a) I and (b) OMe under 520 nm for different times. (c) Plots of the change in absorbance of DPBF at 414 nm at different irradiation times using hematoporphyrin (HP) as the standard in EtOH at room temperature (ΦΔ = 0.53). (d) 1O2 assay using the absorbance attenuation of DPBF in the presence of BODIPY I, H, OMe, and NO2 against HP as the standard in EtOH.

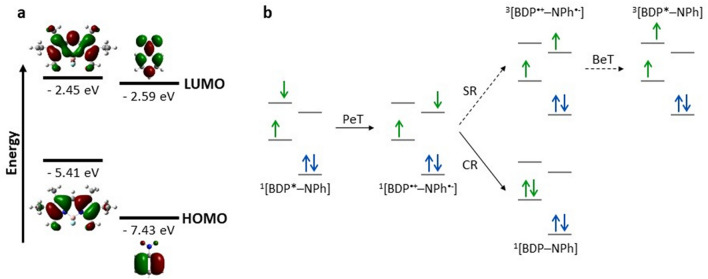

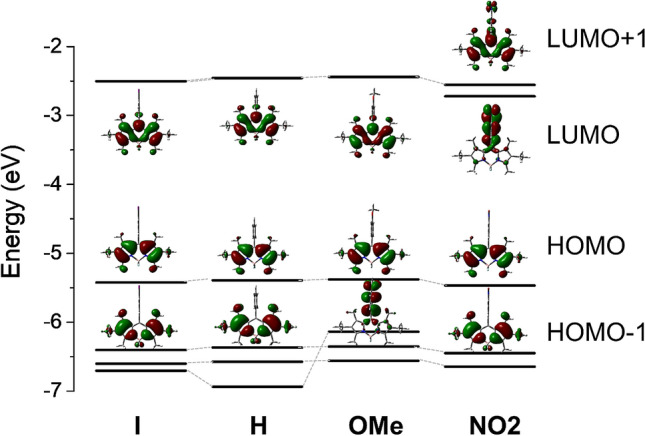

Theoretical characterization of the BODIPY derivatives

To determine the effect of meso-phenyl substituents on the electronic structure of BODIPY PSs, density functional theory (DFT) calculations were performed (see Methods for computational details). As depicted in Fig. 4, the HOMO-3 of BODIPY OMe is destabilized by electron-donating methoxy substituent and consequently HOMO-1 of BODIPY OMe is mainly concentrated on methoxyphenyl (MPh). On the other hand , the LUMO of BODIPY OMe is fully concentrated on the BODIPY (BDP) moiety, implying that upon the generation of the singlet excited state by photoexcitation, PeT may occur, leading to the CT state, 1[BDP•-–MPh•+]. This process enhances the triplet state formation efficiency, as demonstrated by the significant increase in of OMe, compared with H. The energy level of singlet CT state was approximately 0.2 eV higher in energy than that of the singlet excited state (Table S2). However, Filatov et al. suggested that even if the energy of the CT state is greater than that of the singlet excited state, PeT and the subsequent triplet state formation can occur, with a propensity that the efficiency of the processes reduces with increasing energy gap30. Hence, despite the reversal of the state energy, PeT is viewed as a valid mechanism for OMe, which facilitates the generation of the triplet state and 1O2.

Figure 4.

Energy diagram of frontier molecular orbitals of the BODIPY PSs.

The electron-withdrawing nitro group existing in NO2 causes nitrophenyl (NPh) to act as an electron acceptor, while BODIPY becomes an electron donor, as demonstrated by the HOMO and LUMO localized on BODIPY and nitrophenyl, respectively (Figs. 4 and S5). Therefore, in NO2, PeT may produce 1[BDP•+–NPh•-]. Unlike OMe, the energy level of the CT state is much lower than that of the LE state of BODIPY moiety with an energy gap of 0.49 eV, and therefore the lowest CT state dominantly contributes to the energy relaxation after photoexcitation (Table S2). The results of the DFT calculations, in conjunction with the solvent dependency of , clearly confirm the existence of PeT in NO2; however, this does not lead to efficient ISC and energy transfer to ground-state 3O2, as reflected by the very low of BODIPY NO2.

For donor–acceptor-type BODIPY dyads, comparing the frontier orbital energies of donor and acceptor units is beneficial for explaining electron movement during the PeT process44. This approach applies to NO2 because, in its optimized geometry, the two subunits are oriented almost perpendicular ( θdihedral = 87.8°) and can be considered as two independent functional groups. In this context, to elucidate the unexpected decoupling between PeT and the triplet state formation observed for NO2, the HOMO/LUMO energies of hexaalkyl-substituted BODIPY and nitrobenzene were calculated and compared, shown in Fig. 5a.

Figure 5.

(a) Frontier orbital energies of two subunits of NO2. (b) Schematic of the electron movement required for PeT-mediated triplet state generation in NO2. In (b), SR, CR, and BeT represent spin reversion, charge recombination, and back electron transfer, respectively.

As illustrated in Fig. 5b, ISC from 1[BDP•+–NPh•-] to 3[BDP*–MPh] requires the back transfer of an electron from LUMONPh to LUMOBDP, following the conversion of its spin; this process is known as the radical pair ISC (RP-ISC). However, DFT calculations revealed that E(LUMOBDP) > E(LUMONPh) (Fig. 5a), demonstrating that for NO2, back electron transfer (BeT) is an energetically unfavorable process. These findings agree with those of Zhao et al., who explored redox potentials for energetic comparison of frontier orbitals46. In addition, electron spin conversion, which must precede the above process, is often forbidden for directly linked donor–acceptor systems, such as NO2. Hence, 1[BDP•+–NPh•-] of NO2 is most likely to decay nonradiatively to the ground state. However, whether this dissipation occurs directly or via the formation of 3[BDP–NPh*] remains unclear, but it is clear that even if the 3[BDP–NPh*] mainly formed, it does not contribute to the energy transfer to the ground-state 3O2.

These results are consistent with those of Qi et al.47 The electronic properties of the meso-substituent on the BODIPY core, particularly the introduction of a suitable electron-donating group, could be fine-tuned to control the efficiency of singlet oxygen formation. For BODIPY I, the perpendicular geometry between BODIPY and iodophenyl moieties prevents strong electronic coupling between BODIPY and iodine, and accordingly BODIPY I can maintain high fluorescence quantum yield despite the substitution of heavy-atom iodine. These results suggest that BODIPY OMe can be used as a theranostic agent for cancer treatment.

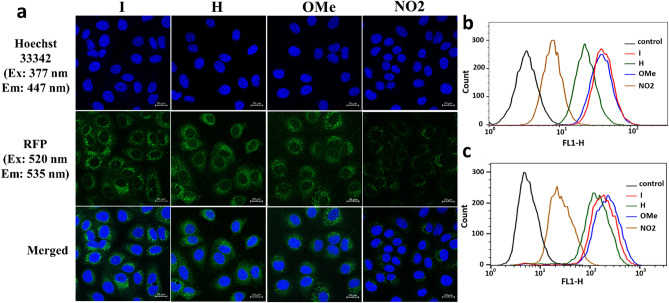

Cellular uptake and cell-imaging of BODIPY NPs

Cellular uptake behaviors of the BODIPY NPs against Huh-7 (human liver carcinoma) and HeLa (human cervix adenocarcinoma) cells were measured and compared by flow cytometry analysis. First, the cells were incubated with 2.0 μM of the BODIPY PSs for 2 h at 37 °C; then, the treated cells were collected and subjected to fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS). As depicted in Figs. 6b,c, these BODIPY NPs exhibited higher selectivity for Huh-7 cells than HeLa cells. The mean fluorescence of liver cancer cells treated with I, H, OMe, and NO2-NPs was approximately 4.6-, 6.2-, 6.1-, and fourfold higher than that of the treated HeLa cells (Fig. 6b,c and Table S3). Such finding is due to the high density of ASGP receptors on the surface of liver cancer cells, which can bind BODIPY NPs containing galactose residues and be successfully internalized into Huh-7 cells via receptor recognition48,49, which is consistent with our previous report24. This result demonstrates that BODIPY PSs with versatile functional groups can have an improved targeting ability compared to imaging-guided PDT agents which cannot be chemically modified such as 5-aminolevulinic acid (ALA)50.

Figure 6.

Cell selectivity and imaging of lactose-functionalized BODIPY PSs. Fluorescence images of Huh-7 cells were captured after a 2 h incubation with 2 µM of I, H, OMe, and NO2-NPs. After incubation, cell nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33,342 dye for 10 min. Images were captured with a 40 × objective lens and fluorescence optics (excitation at 520 nm for I, H, OMe, and NO2-NPs and 377 nm for Hoechst 33,342; and emission at 535 nm for I, H, OMe, and NO2-NPs and 447 nm for Hoechst 33,342). Scale bar = 20 μm (a). The fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis of HeLa (b) and Huh7 cells (c) treated with 2 μM of BODIPY I, H, OMe, and NO2.The incubation time was 2 h for all BODIPY NPs.

Lactose modification can provide BODIPY NPs with potential applications in specific liver cancer imaging ability. To evaluate the potential application of the fluorescent dye for cell imaging, liver cancer Huh-7 cells were treated with these dyes for 2 h and imaged by confocal microscopy. Hoechst 33,342, a fluorescent stain commonly used to visualize the nucleus, was used to confirm fluorescent dye localization within the cells. As shown in the cellular images (Fig. 6a), the targeting BODIPY NPs could be effectively transported into Huh-7 cells, which was mediated by galactose receptors, after cultivation for 2 h and firmly gathered in the cytoplasm and perinuclear region. Hoechst 33,342 resulted in blue fluorescence in the nucleus of Huh-7 cells, and the merged image revealed that these BODIPY NPs could specifically bind to Huh-7 cells and localize in their cytoplasm. Therefore, these BODIPY NPs can effectively distinguish the cytoplasm of Huh-7 cells from the nucleus.

Huh-7 cells cultured with H, I, and OMe-NPs showed stronger fluorescence, whereas those cultured with NO2-NPs displayed weaker fluorescence; this is caused by the high fluorescence of H, I, and OMe-NPs along with cellular uptake of NO2-NPs being the lowest, consistent with the FACS results. Additionally, as mentioned above, NO2-NPs exhibited PeT in polar media, resulting in the CT state, which inhibits fluorescence. As a result, NO2-NPs appeared darker in the cell-imaging than the other compounds.

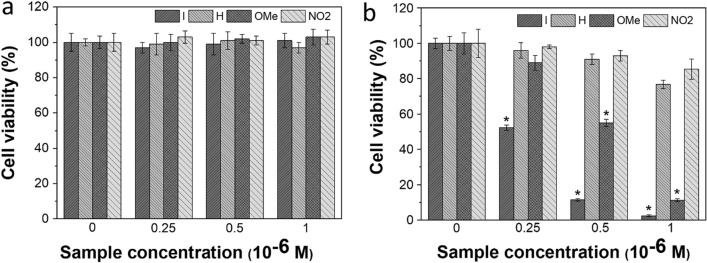

Light-induced cytotoxicity of BODIPY NPs against cancer cells

The biocompatibility of I, H, NO2, and OMe-NPs with Huh-7 and HeLa cells was determined using MTS assays. As shown in Figs. 7a and S6a, there was no cytotoxicity in any of the tested cells, and more than 97% of both Huh-7 and HeLa cells survived after 24 h of incubation. Thus, all water-soluble BODIPY PSs below a dose of 1 µM had good biocompatibility and did not induce severe cytotoxicity in fibroblasts and cancer cells, implying that BODIPY I, H, NO2, and OMe-NPs could be used in the light cytotoxicity test.

Figure 7.

Photodynamic anticancer activities of BODIPY PSs in Huh-7 cells. Cytotoxicity (a) and phototoxicity (b) of BODIPY I, H, OMe, and NO2-NPs in Huh-7 cells (hepatocellular carcinoma) under light irradiation (λirr 530 nm, 8.6 J·cm-2). The cell viabilities were detected using a CCK-8 kit after incubation with I, H, OMe, and NO2-NPs for 24 h under dark conditions. Quantitative data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (n = 4). Statistical significance based on the Student’s t-tests was considered as *p < 0.05.

For the efficient production of ROS, HeLa and Huh-7 cells were exposed to 530 nm laser irradiation at an extremely low energy of 8.6 J·cm-2, and the in vitro phototoxicity of PDT was assessed. First, there was no significant variance when HeLa and Huh-7 cells were cultured with RPMI containing 1 μM of H and NO2-NPs, not only under dark conditions but also under irradiation; this is because of their low singlet oxygen quantum yield, as mentioned above. When exposed to LED light, I and OMe-NPs resulted in high phototoxicity to tumor cells and negligible cell toxicity in the dark, as shown in Figs. 7b and S6b. Cell viability evidently decreased as the concentration of these BODIPY NPs increased. Furthermore, when HeLa cells were exposed to light in the presence of 1 μM of OMe and I-NPs, cell viability decreased by approximately 78% and 83%, respectively, while Huh-7 cells died by up to 89% and 97.7%, respectively, indicating their efficient PDT targeting ability. Besides, the half-lethal dose (IC50) of OMe-NPs for HeLa and Huh-7 cell lines was 0.62 and 0.52 μM, respectively. Notably, when exposed to light, the lactose-tethered BODIPY OMe and I-NPs killed more Huh-7 cells than HeLa cells, with IC50 values of 0.51 and 0.26 μM, respectively. These results demonstrate that BODIPY I and OMe-NPs provide better treatment efficacy with relatively low irradiation intensity than H and NO2-NPs.

Conclusion

We designed and synthesized a series of lactose-functionalized BODIPY PSs with different substituent groups at the meso-position of the BODIPY core as cancer-targeted theragnostic agents for imaging and PDT. These BODIPY PSs could aggregate into nanoparticles (I-, H-, OMe-, and NO2-NPs) in an aqueous solution and displayed a uniform size and shape, as determined by TEM and DLS. The fluorescence quantum yields of BODIPY I, H, and OMe were remarkably high, whereas that of BODIPY NO2 was significantly lower due to the PeT process in polar media. Among the four BODIPY photosensitizers, BODIPY I demonstrated high efficiency of singlet oxygen generation caused by the heavy atom effect due to the presence of an iodine atom, while BODIPY OMe containing an electron-donating methoxy group at the meso-phenyl moiety also enhanced the ISC efficiency. In contrast, the strong electron withdrawing by nitro group (NO2) caused a marked reduction in both the fluorescence quantum yield and singlet oxygen formation efficiency of BODIPY NO2 due to effective PeT in the polar media. The cellular experiments demonstrated that the water-soluble BODIPY NPs series showed good biocompatibility and cancer-specific fluorescence imaging ability. Notably, BODIPY OMe and I-NPs presented excellent phototoxicity against cancer cells, especially, liver cancer Huh-7 cells. The biocompatible BODIPY NPs have proven to be promising for developing highly efficient theragnostic agents for imaging-guided PDT for cancer treatment.

Methods

Materials instrumentations

Almost all reagents and chemicals were obtained from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Some solvents such as dichloromethane (CH2Cl2), methanol (MeOH), or MgSO4, sodium azide (NaN3), sodium ascorbate (NaAsc), Copper (II) sulfate pentahydrate (CuSO4.5H2O) were purchased from Daejung chemical (Gyeonggi-do, South Korea), and used without further purification. Lactose-propargyl was synthesized in our previous literature24.

All compounds were characterized by 1H and 13C-NMR spectroscopy on a Bruker AM 250 spectrometer (Billerica, MA, USA). The impurity of the products was checked by thin-layer chromatography (TLC, silica gel 60 mesh). UV spectra were measured on a Shimadzu UV-1650PC spectrometer, and Fluorescence spectra were carried on a Hitachi F-7000 spectrometer. The size and morphology of BODIPY NPs were analyzed by using dynamic light scattering (DLS) on Malvern Zetasizer Nano ZS90 and transmission electron microscopy (TEM). We used machine JEOL- JEM 2100F at an accelerating voltage of 200 kV. The sample for TEM was prepared according to our reported literature51.

Synthesize of water-soluble BODIPY I, H, OMe, and NO2:

According to our reported literature24, the series of water-soluble BODIPY I, H, OMe, and NO2 were prepared using the same pathway. A representative routine is presented for the compound I. Briefly, BODIPY 2a (80 mg, 0.157 mmol), lactose propargyl (66 mg, 0.173 mmol), NaAsc (156 mg, 0.785 mol), and CuSO4.5H2O (79 mg, 0.316 mmol) were dissolved in the mixture of THF/water (15/5 mL, v/v). The resulting mixture was stirred for one day at room temperature, extracted with THF and water three times, and dried over MgSO4. After removing the solvent by a rotary evaporator, the crude product was purified by recrystallization using MeOH/diethyl ether to afford an orange solid (yield 76 mg, 52% yield). 1H NMR (300 MHz, CD3OD, δ, ppm): δ 8.02 (s, 1H), 7.97- 7.95 (d, 2H), 7.17- 7.15 (d, 2H), 5.83 (s, 2H), 4.36- 4.33 (d, 2H), 3.87- 3.85 (d, 2H), 3.81- 3.80 (d, 2H), 3.76- 3.74 (d, 1H), 3.71- 3.69 (d, 1H), 3.57- 3.53 (d, 2H), 3.49- 3.48 (d, 2H), 3.31- 3.29 (d, 2H), 2.57 (s, 3H), 2.42–2.39 (q, 4H), 1.44 (s, 3H), 1.36 (s, 3H), 1.28 (s, 3H), 1.05- 1.00 (t, 3H). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CD3OD, δ, ppm): δ 162.25, 143.55, 143.24, 142.81, 140.13, 138.60, 137.3, 135.75, 134.58, 134.16, 131.48, 131.32, 105.09, 103.29, 96.18, 80.57, 77.05, 76.45, 76.29, 74.75, 74.58, 72.52, 70.38, 63.00, 62.42, 61.82, 46.12, 17.57, 17.32, 14.87, 14.76, 13.2, 12.45, 11.92. HRMS (ESI): calculated for (C38H49BF2IN5O11): m/z: [M]: 928.2613; found: 928.2619.

Compound H: BODIPY H was synthesized according to the general procedure to afford the orange solid (67 mg, 57% yield). 1H NMR (300 MHz, CD3OD, δ, ppm): δ 8.01 (s, 1H), 7.59- 7.57 (t, 3H), 7.37- 7.36 (d, 2H), 5.84 (s, 2H), 4.37- 4.33 (d, 2H), 3.87- 3.85 (d, 2H), 3.81- 3.80 (d, 2H), 3.76- 3.73 (d, 1H), 3.69- 3.66 (d, 1H), 3.59- 3.57 (d, 2H), 3.54- 3.52 (d, 2H), 3.49- 3.32 (d, 2H), 2.53 (s, 3H), 2.43–2.38 (q, 4H), 1.38 (s, 3H), 1.31 (s, 3H), 1.28 (s, 3H), 1.04- 0.99 (t, 3H). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CD3OD, δ, ppm): δ 161.82, 144.19, 143.61, 143.46, 138.71, 136.45, 134.29, 131.7, 130.75, 130.61, 129.43, 105.16, 103.36, 80.45, 77.26, 77.15, 76.41, 74.6, 72.4, 70.26, 62.96, 62.53, 61.77, 61.66, 48.07, 17.68, 14.85, 14.5, 13.16, 12.24, 11.66. HRMS (ESI): calculated for (C38H55BF2IN5O12Na): m/z: [M + Na]+: 834.3713; found: 834.3714.

Compound OMe: BODIPY OMe was synthesized according to the general procedure to afford the orange solid (55 mg, 47% yield). 1H NMR (300 MHz, CD3OD, δ, ppm): δ 8.0 (s, 1H), 7.23- 7.2 (d, 2H), 7.13- 7.1 (d, 2H), 5.87 (s, 2H), 4.37- 4.34 (d, 2H), 3.89 (s, 3H), 3.77- 3.71 (q, 3H), 3.6- 3.5 (m, 6H), 3 42- 3.39 (d, 1H), 2.56 (s, 3H), 2.4–2.38 (q, 4H), 1.43 (s, 3H), 1.36 (s, 3H), 1.28 (s, 3H), 1.01- 0.95 (t, 3H). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CD3OD, δ, ppm): δ 162.15, 144.48, 143.03, 138.59, 136.87, 134.71, 134.18, 132.17, 130.55, 128.29, 116.06, 105.04, 103.33, 80.37, 77.08, 76.53, 76.22, 74.82, 74.64, 72.64, 70.21, 63.04, 62.43, 61.75, 55.8, 46.14, 17.73, 17.44, 14.87, 14.26, 13.28, 12.53, 11.56. HRMS (ESI): calculated for (C39H52BF2N5O12Na): m/z: [M + Na]+: 854.3571; found: 854.3572.

Compound NO2: BODIPY NO2 was synthesized according to the general procedure to afford the orange solid (80 mg, 61% yield). 1H NMR (300 MHz, CD3OD, δ, ppm): δ 8.47- 8.44 (d, 2H), 8.01 (s, 1H), 7.69- 7.66 (d, 2H), 5.83 (s, 2H), 4.37- 4.34 (d, 2H), 3.86- 3.32 (d, 2H), 3.79- 3.75 (d, 2H), 3.6- 3.5 (m, 6H), 3.31- 3.29 (d, 2H), 2.59 (s, 3H), 2.41- 2.39 (q, 4H), 1.39 (s, 3H), 1.31 (s, 3H), 1.29 (s, 3H), 1.04- 0.98 (t, 3H). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CD3OD, δ, ppm): δ 163.11, 149.96, 143.16, 141.37, 138.46, 137.78, 134.63, 133.69, 131.64, 130.96, 125.76, 105.14, 103.6, 80.37, 77.35, 76.4, 76.24, 74.84, 74.35, 72.54, 70.36, 63.11, 62.44, 61.76, 46.06, 19.39, 17.86, 14.86, 14.46, 13.09, 12.63, 11.71. HRMS (ESI): calculated for (C38H49BF2N6O13Na): m/z: [M + Na]+ : 869.3316; found: 869.3318.

Measurement of photophysical properties

The Φf were measured by a comparative method using the standard reference with the already-known value of Φf as the following Eq. (1):

| 1 |

The subscript of S and R represent sample and reference, respectively. N is the refractive index of solvent. A and D are the absorbance and the integrated fluorescence area, respectively. Solutions should be optically dilute to avoid inner filter effects. The Rhodamine 6G was used as the reference sample, which possessed a known quantum yield of 0.9442.

Detection of singlet oxygen quantum yields

The quantum yields of singlet oxygen (ΦΔ) of BODIPY I, H, OMe, and NO2 were studied using diphenylisobenzofuran (DBPF) as a chemical quencher43. Briefly, a mixture of the BODIPY dye (absorption ~ 0.02 at 520 nm in EtOH) and the DPBF (absorption ~ 1.0 at 414 nm in EtOH) was irradiated with a laser light (λirr = 520 nm). The photooxidation of DPBF was monitored between 0 ~ 60 min depending on the efficiency of the PSs. The singlet oxygen quantum yield was calculated using hematoporphyrin (HP) as the reference with a yield of 0.53 in ethanol according to the following Eq. (2):

| 2 |

where is the singlet oxygen quantum yield of the reference, k is the slope of the photodegradation rate of DPBF, S means the sample, R represents the reference. F denotes the absorption correction factor, given by F = 1 – 10-OD (OD at the irradiation wavelength).

Quantum chemical calculations

Molecular structure optimizations for BODIPY derivatives were carried out using density functional theory (DFT), and their electronic states were calculated using time-dependent DFT (TD-DFT). For H, OMe, and NO2, the b3lyp functional of the Gaussian 16 program package and 6-31G(d) basis sets were chosen. For I, due to the heavy iodine atom, lanl2dz basis sets were chosen instead. All calculations were carried out in water solvent environment. The lactose-tethered triazole moiety attached to the position of the BODIPY core was confirmed to have a negligible influence on calculation results (Figure S2) and therefore was replaced by a hydrogen atom for simplicity.

Preparation of BODIPY nanoparticles (NPs)

The stock solution of each BODIPY dyes in THF (0.5 mg.ml-1) was prepared, then 50 µL of stock solution was slowly added to 5 mL of water. The mixture was stirred overnight to evaporate all of THF naturally to yield the designed nanoparticles for further experiment.

Cells and cell culture

HeLa (human cervix adenocarcinoma), Huh7 (human liver carcinoma) cells were obtained from the Korean Cell Line Bank. The cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA, USA) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) and antibiotics (100 U/mL penicillin and 100 mg/mL streptomycin) at 37 ºC in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator.

Cell proliferation assay

Cell proliferation was studied using CellTiter 96 ® Aqueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, HeLa and Huh7 (3 × 103 cells/well) were seeded in 96-well plates. After the cells were maintained for 24 h, cells were treated with BODIPY I, H, OMe, and NO2 at different concentrations (0, 0.25, 0.5, and 1 µM) for 24 h. Following 24 h of incubation, 20 µL MTS [3-(4, 5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium] reagent were added to each well and incubated for 4 h at 37 °C. The absorbance was determined at 490 nm using an ELISA plate reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA).

Assessment of cellular uptake and cellular imaging

To confirm the cellular uptake and cellular imaging by using the BODIPY I, H, OMe, and NO2, Huh-7 cells were incubated with 2 µM of BODIPY I, H, OMe, and NO2 for 2 h and washed three times with DPBS. After then, the cells were subsequently counterstained with Hoechst 33,342 for 10 min. After washing three times with DPBS, the morphologies of Huh-7 cells were taken by an automated live-cell imager (Lionheart FX, BioTek Instruments, Inc., VT, USA) with 40 × objective lens and fluorescence optics (excitation at 520 nm for BODIPY I, H, OMe, and NO2 and at 377 nm for Hoechst 33,342, and emission at 535 nm for BODIPY I, H, OMe, and NO2 and at 447 nm for Hoechst 33,342). Cellular images were analyzed using Gen5™ imager software (Ver.3.04, BioTek Instruments, Inc., VT, USA).

Photodynamic anticancer activity assessment

The HeLa and Huh7cells were seeded at 3 × 103 cells/well in a 96-well plate and incubated at 37 °C in 5% CO2. After 24 h, the cells were incubated again with various concentrations of BODIPY I, H, OMe, and NO2 (0, 0.25, 0.5, and 1 µM) at 37 °C in 5% CO2 for 2 h under dark conditions. After 2 h incubation for uptaking the BODIPY I, H, OMe, and NO2 into the cells, the media in all plates were changed with RPMI 1640 media without phenol red. Irradiation of cells was performed with a green light-emitting diode (LED) using about 9 mW (530 nm, for 20 min, 80%). After irradiation, the cells were incubated for an additional 24 h, and the cell proliferation was measured using CellTiter 96 ® Aqueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay as the same method for the cytotoxicity described above.

Cellular uptake using flow cytometry

The cells (HeLa and Huh7) were seeded at 1 × 105 cells/well in 6-well plate. After 24 h incubation at 37℃ in 5% CO2, the BODIPY I, H, OMe, and NO2 (2 μM) were treated with cells for 2 h. Then, the cell were washed with phosphate buffered saline and analyzed using flow cytometry FC500 (Beckman coulter, CA, USA).

Statistical analysis

All results are expressed as the means ± standard deviations and were compared by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA followed by Tukey’s analysis with Prism GraphPad 6 software (San Diego, CA, USA). A significance level was set at *p < 0.05.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

This work was performed with financial support from the research funds provided by Chosun University in 2021.

Author contributions

D.K.M., H.J.K. designed the protocol. D.K.M., I.W.B., and T.P.V. carried out the experiments. J.L. conducted cell experiments. C.K. studied computational modeling work. S.C., J.Y., and H.J.K. supported and advised the experiments. D.K.M., J.Y., and H.J.K. wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Duy Khuong Mai, Chanwoo Kim and Joomin Lee.

Contributor Information

Sung Cho, Email: scho@chonnam.ac.kr.

Jaesung Yang, Email: jaesung.yang@yonsei.ac.kr.

Ho-Joong Kim, Email: hjkim@chosun.ac.kr.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-022-06000-5.

References

- 1.Allison RR, Sibata CH. Oncologic photodynamic therapy photosensitizers: a clinical review. Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther. 2010;7:61–75. doi: 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2010.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baskaran R, Lee J, Yang S-G. Clinical development of photodynamic agents and therapeutic applications. Biomater. Res. 2018;22:1–8. doi: 10.1186/s40824-018-0140-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li X, Lovell JF, Yoon J, Chen X. Clinical development and potential of photothermal and photodynamic therapies for cancer. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2020;17:657–674. doi: 10.1038/s41571-020-0410-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kwiatkowski S, et al. Photodynamic therapy–mechanisms, photosensitizers and combinations. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018;106:1098–1107. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.07.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mansoori B, et al. Photodynamic therapy for cancer: Role of natural products. Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther. 2019;26:395–404. doi: 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2019.04.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benov L. Photodynamic therapy: current status and future directions. Med. Princ. Pract. 2015;24:14–28. doi: 10.1159/000362416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.dos Santos, A. l. F., de Almeida, D. R. Q., Terra, L. F., Baptista, M. c. S. & Labriola, L. Photodynamic therapy in cancer treatment-an update review. J. Cancer Metast. Treatment5 (2019).

- 8.Li L, et al. Interaction and oxidative damage of DVDMS to BSA: a study on the mechanism of photodynamic therapy-induced cell death. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:1–11. doi: 10.1038/srep43324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Naidoo C, Kruger CA, Abrahamse H. Photodynamic therapy for metastatic melanoma treatment: A review. Technol. Cancer Res. Treat. 2018;17:1533033818791795. doi: 10.1177/1533033818791795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Civantos FJ, et al. A review of photodynamic therapy for neoplasms of the head and neck. Adv. Ther. 2018;35:324–340. doi: 10.1007/s12325-018-0659-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kumar R, et al. Small conjugate-based theranostic agents: an encouraging approach for cancer therapy. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015;44:6670–6683. doi: 10.1039/c5cs00224a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sirotkina M, et al. Photodynamic therapy monitoring with optical coherence angiography. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:1–11. doi: 10.1038/srep41506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang C, et al. Microenvironment-triggered dual-activation of a photosensitizer-fluorophore conjugate for tumor specific imaging and photodynamic therapy. Sci. Rep. 2020;10:1–9. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-68847-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cai Y, et al. Organic dye based nanoparticles for cancer phototheranostics. Small. 2018;14:1704247. doi: 10.1002/smll.201704247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lan M, et al. Photosensitizers for photodynamic therapy. Adv. Healthcare Mater. 2019;8:1900132. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201900132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bui HT, et al. Effect of substituents on the photophysical properties and bioimaging application of BODIPY rerivatives with triphenylamine substituents. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2019;123:5601–5607. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.9b04782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guo Z, et al. Bifunctional platinated nanoparticles for photoinduced tumor ablation. Adv. Mater. 2016;28:10155–10164. doi: 10.1002/adma.201602738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nguyen V-N, et al. Recent developments of BODIPY-based colorimetric and fluorescent probes for the detection of reactive oxygen/nitrogen species and cancer diagnosis. Coordinat. Chem. Rev. 2021;439:213936. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang T, Ma C, Sun T, Xie Z. Unadulterated BODIPY nanoparticles for biomedical applications. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2019;390:76–85. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Plaetzer K, Krammer B, Berlanda J, Berr F, Kiesslich T. Photophysics and photochemistry of photodynamic therapy: fundamental aspects. Lasers Med. Sci. 2009;24:259–268. doi: 10.1007/s10103-008-0539-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim B, et al. In vitro photodynamic studies of a BODIPY-based photosensitizer. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2016;2017:25–28. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zou J, et al. BODIPY derivatives for photodynamic therapy: influence of configuration versus heavy atom effect. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2017;9:32475–32481. doi: 10.1021/acsami.7b07569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang Z, et al. BODIPY-doped silica nanoparticles with reduced dye leakage and enhanced singlet oxygen generation. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:12602. doi: 10.1038/srep12602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khuong Mai, D. et al. Synthesis and photophysical properties of tumor-targeted water-soluble BODIPY photosensitizers for photodynamic therapy. Molecules25 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Aoife Gorman JK, O’Shea C, Kenna T, Gallagher WM, O’Shea DF. In vitro demonstration of the heavy-atom effect for photodynamic therapy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:10619–10631. doi: 10.1021/ja047649e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Takatoshi-Yogo YU, Ishitsuka Y, Maniwa F, Nagano T. Highly efficient and photostable photosensitizer based on BODIPY chromophore. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:12162–12163. doi: 10.1021/ja0528533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lu S, et al. PEGylated dimeric BODIPY photosensitizers as nanocarriers for combined chemotherapy and cathepsin B-activated photodynamic therapy in 3D tumor spheroids. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2020;3:3835–3845. doi: 10.1021/acsabm.0c00394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen H, Bi Q, Yao Y, Tan N. Dimeric BODIPY-loaded liposomes for dual hypoxia marker imaging and activatable photodynamic therapy against tumors. J. Mater. Chem. B. 2018;6:4351–4359. doi: 10.1039/c8tb00665b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ucuncu M, et al. BODIPY-Au(I): A photosensitizer for singlet oxygen generation and photodynamic therapy. Org. Lett. 2017;19:2522–2525. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.7b00791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Filatov MA, et al. Control of triplet state generation in heavy atom-free BODIPY-anthracene dyads by media polarity and structural factors. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2018;20:8016–8031. doi: 10.1039/c7cp08472b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Callaghan S, Filatov MA, Savoie H, Boyle RW, Senge MO. In vitro cytotoxicity of a library of BODIPY-anthracene and -pyrene dyads for application in photodynamic therapy. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2019;18:495–504. doi: 10.1039/c8pp00402a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Filatov MA. Heavy-atom-free BODIPY photosensitizers with intersystem crossing mediated by intramolecular photoinduced electron transfer. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2019;18:10–27. doi: 10.1039/c9ob02170a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lingling-Li JH, Nguyen B, Burgess K. Syntheses and spectral properties of functionalized, water-soluble BODIPY derivatives. J. Org. Chem. 2008;73:1963–1970. doi: 10.1021/jo702463f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dorh N, et al. BODIPY-based fluorescent probes for sensing protein surface-hydrophobicity. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:18337. doi: 10.1038/srep18337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hisato Sunahara YU, Kojima H, Nagano T. Design and synthesis of a library of BODIPY-based environmental polarity sensors utilizing photoinduced electron-transfer-controlled fluorescence ON/OFF switching. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:5597–5604. doi: 10.1021/ja068551y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim TH, Park IK, Nah JW, Choi YJ, Cho CS. Galactosylated chitosan/DNA nanoparticles prepared using water-soluble chitosan as a gene carrier. Biomaterials. 2004;25:3783–3792. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.10.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ulrich G, Ziessel R, Haefele A. A general synthetic route to 3,5-substituted boron dipyrromethenes: applications and properties. J. Org. Chem. 2012;77:4298–4311. doi: 10.1021/jo3002408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shilei Zhu JZ, Vegesna G, Luo FT, Green SA, Liu H. Highly water-soluble neutral BODIPY dyes with controllable fluorescence quantum yields. Org. Lett. 2011;13:438–441. doi: 10.1021/ol102758z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vu TT, et al. Understanding the spectroscopic properties and aggregation process of a new emitting boron dipyrromethene (BODIPY) J. Phys. Chem. C. 2013;117:5373–5385. doi: 10.1021/jp3097555. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sun H, et al. Excellent BODIPY dye containing dimesitylboryl groups as PeT-based fluorescent probes for fluoride. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2011;115:19947–19954. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Papalia T, et al. Cell internalization of BODIPY-based fluorescent dyes bearing carbohydrate residues. Dyes Pigm. 2014;110:67–71. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Douglas-Magde RWAPGS. Fluorescence quantum yields and their relation to lifetimes of rhodamine 6G and fluorescein in nine solvents: improved absolute standards for quantum yields. Photochem. Photobiol. 2002;75(4):327–334. doi: 10.1562/0031-8655(2002)075<0327:fqyatr>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wolfgang-Spiller, H. K., Wo¨hrle, D., Hackbarth, S., Ro¨der, B. & Schnurpfeil, G. Singlet oxygen quantum yields of different photosensitizers in polar solvents and micellar solutions. J. Porphyr. Phthalocyan. 2, 145–158 (1998)

- 44.Filatov MA, et al. Generation of triplet excited states via photoinduced electron transfer in meso-anthra-BODIPY: fluorogenic response toward singlet oxygen in solution and in vitro. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017;139:6282–6285. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b00551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liane M. Rossi, P. R. S., Vono, L. L. R., Fernandes, A. U., Tada, D. B., & Baptista M.S. Protoporphyrin IX nanoparticle carrier: preparation, optical properties, and singlet oxygen generation. Langmuir24, 12534–12538 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.Hu W, et al. Can BODIPY-electron acceptor conjugates act as heavy atom-free excited triplet state and singlet oxygen photosensitizers via photoinduced charge separation-charge recombination mechanism? J. Phys. Chem. C. 2019;123:15944–15955. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Qi S, Kwon N, Yim Y, Nguyen VN, Yoon J. Fine-tuning the electronic structure of heavy-atom-free BODIPY photosensitizers for fluorescence imaging and mitochondria-targeted photodynamic therapy. Chem. Sci. 2020;11:6479–6484. doi: 10.1039/d0sc01171a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lu, Z. et al. Water-soluble BODIPY-conjugated glycopolymers as fluorescent probes for live cell imaging. Polym. Chem. 4 (2013).

- 49.Liu L, Ruan Z, Li T, Yuan P, Yan L. Near infrared imaging-guided photodynamic therapy under an extremely low energy of light by galactose targeted amphiphilic polypeptide micelle encapsulating BODIPY-Br 2. Biomater Sci. 2016;4:1638–1645. doi: 10.1039/c6bm00581k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sando Y, et al. 5-aminolevulinic acid-mediated photodynamic therapy can target aggressive adult T cell leukemia/lymphoma resistant to conventional chemotherapy. Sci. Rep. 2020;10:1–11. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-74174-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Khuong Mai, D. et al. Aggregation-induced emission of tetraphenylethene-conjugated phenanthrene derivatives and their bio-imaging applications. Nanomaterials (Basel)8 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.