Abstract

Nutrient input from estuarine producers underpins coastal fisheries production and knowing which producers are the most responsible for fish diet helps effectively protect and restore coastal ecosystems. Focussing on the Richmond River in Australia as a case study, we sampled the main estuarine producers and estimated their proportional contributions of nutritional input to seven commercially important fisheries species using Bayesian isotope mixing models. We valued the dietary input of estuarine producers to the commercial fisheries by combining dietary contribution estimates with total annual catch data from commercial fishers. A conservative estimate is that estuarine producers in the Richmond River Estuary contribute at least 82 725 kg (78%) of the total annual catch of the seven commercially important fish with an estimated annual value of $AU 450 117. Sea mullet and Mud crab contributed 95% of the total catch, and 93% of the total value assigned to estuarine producers. The two highest valued estuarine producers were tidal marsh (Juncus kraussii) $AU 82 432 and seagrass (Zostera capricorni) $AU 65 423. This study demonstrates the substantial role of estuarine producers to commercial fisheries production and the fisheries economy more broadly. With large areas of estuarine producers under threat globally from land clearing for agriculture, aquaculture and urbanisation, the results presented here provide evidence to support the value of coastal habitats and benefits of their preservation and restoration.

Graphic abstract

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s13280-021-01600-3.

Keywords: Ecosystem services, Fisheries production, Monetary valuation, Natural assets, Quantification of natural capital, Socio-ecological and economic benefits of natural capital

Introduction

The coastal zone and estuaries are often densely populated areas with high and sustained population growth and associated development pressure (Lotze et al. 2006). As such, estuaries have been subject to substantial habitat degradation and loss that significantly impacts estuarine ecosystem services such as fisheries production (Brown et al. 2018). To better maintain, improve and re-establish estuarine ecosystems, quantification and valuation of the ecosystem services they provide is needed.

Estuaries contain some of the most productive ecosystems on earth (Barbier et al. 2011), where aquatic primary producers form the underlying basis for the majority of fisheries food-webs and provide refuge from predation pressure (Deegan and Garritt 1997; Christianen et al. 2017). Primary producers support fish through direct or indirect nutritional input (Garcia et al. 2017) in one or more life history stages (Le et al. 2018). Consequently, productivity of estuarine fish species is inherently linked to the productivity of producers at the base of the food chain (Phillips et al. 2014). While it is understood that estuarine ecosystems are critical for maintaining fish production, there is currently a lack of quantitative data demonstrating to what degree primary productivity is directly linked to fisheries production and the subsequent value of this (but see Qiu et al. 2018; Jänes et al. 2020a, b; Jänes et al. 2020b). However, such information is critical for informing management decisions on how the extent, quality and diversity of estuarine ecosystems links to fisheries production and human well-being (Raudsepp-Hearne and Peterson 2016).

One way to directly link estuarine producers to fisheries is by measuring their dietary contribution. Historically this has been done through direct observations of gut content analysis, or visual observations (Webb 1973; Coetzee 1982; Cadigan and Fell 1985). However, more recently, stable isotope elemental ratios (δ13C, δ15N and δ34S) of estuarine producers have been used to quantify the energy transfer from producers to fish biomass (Jennings et al. 1997; Connolly 2003; Phillips et al. 2014). The overall logic of the approach relies on the assumption that stable isotope signatures of primary producers differ from one another and that these differences are reflected in the consumer tissue. As species specific isotope ratios propagate through food-webs with consistent and predictable patterns they are currently one of the best and most commonly used methods for studying energy transfer in ecological systems (Cresson et al. 2014; Corry et al. 2018; Raoult et al., 2018). For instance, commercially and recreationally targeted penaeid prawns near Sydney Australia, show close dietary associations to tidal marsh (53%) and seagrass (40%) based on the stable isotope signatures from plant samples and prawn tissue (Hewitt et al. 2020). Proportional contributions of energy transfer from estuarine producers to fish biomass can then be combined with market prices of harvestable fish to value both ecological and economic benefits of nature to people (Taylor et al. 2018; Jänes et al. 2020a).

Previous research efforts have quantified proportional contributions of primary producers to fish production in estuaries worldwide (Marley et al. 2019; Wang et al. 2019); however, species dietary niche spaces have so far been overlooked. Better understanding of dietary niche spaces helps to detect interspecific resource competition and potential vulnerability of fish to ecosystem degradation (Phillips et al. 2014). With an increased emphasis on understanding niche dynamics in ecosystem, community and climate change contexts there is a growing need for robust methods to quantify niche space differences between taxa (Broennimann et al. 2012). Bayesian mixing model techniques now enable investigation of dietary niche spaces of species based on proportional contributions of sources. This in turn advances our understanding of the monetary value of estuarine producers from commercial fisheries because proportional source contributions can be combined with commercial fishery data and valued based on market prices of fish.

The Richmond River Estuary is a large estuary in eastern Australia, supporting a range of estuarine ecosystems from seagrass, mangroves and saltmarsh closer to the estuary mouth, to brackish and freshwater ecosystems further upstream. Since European settlement in the early 1840s, the estuary has been impacted by human activity such as timber harvesting, maritime transport, land clearing and wetland drainage for agriculture (Goulstone 1993). The fishing industry developed as transport routes improved, providing more reliable access to a wider range of markets. As a result, the Richmond District Fishermen’s Cooperative was established in the late 1940s as the commercial fishing industry developed, which provided input to the regional economy. The last 40 years have seen a decline in commercial fisheries effort in the Richmond River and adjacent offshore waters (Harrison 2010). The fleet of offshore prawn trawlers that mainly target Eastern king prawn has reduced from 15 vessels in 1991 to 3 in 2020. Recreational fishing effort has increased and the lower part of the estuary was closed to commercial fishing to provide more recreational fishing opportunities.

Despite the well-established importance of the Richmond River Estuary to people’s livelihoods, the lack of fisheries-habitat data limits the quantification of ecosystem benefits to human livelihood. In this study we sought to determine the importance of estuarine producers to commercial fisheries production in the Richmond River Estuary, Australia by quantifying nutritional contributions of primary producers to fish production by using stable isotope analysis. By conducting this study, we wanted to help resource users (commercial and recreational fishers), secondary beneficiaries (tourism industries) and coastal communities build their understanding and appreciation of the links and dependence of economies, and social and cultural values on natural infrastructure. As such, we aimed to (a) assess the relative contribution of estuarine producers to fisheries production; (b) quantify realized dietary niche space of fish; and (c) combine proportional contributions from producers with commercial fishery data and value this contribution based on market prices of fish.

Materials and Methods

Study site description

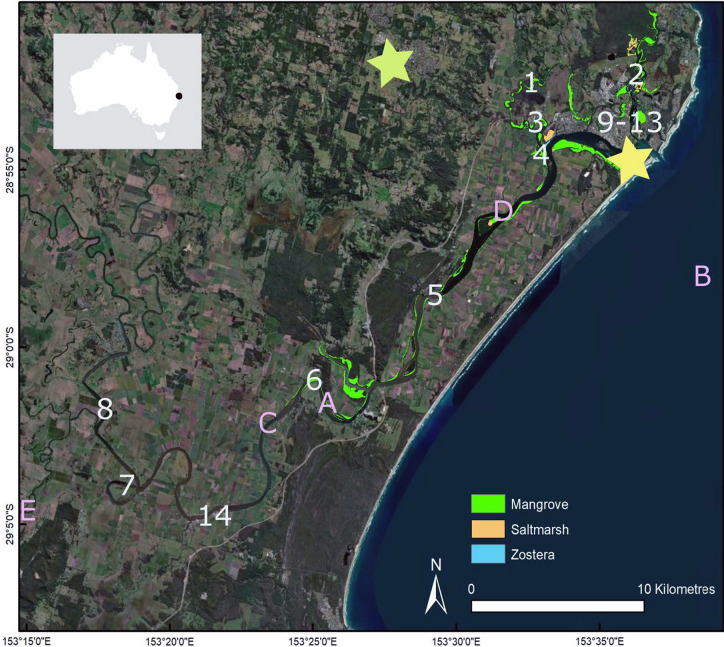

The Richmond River (153° 35′ E, 28° 53′ S) is a large river with a catchment area of 6850 km2 located in northern New South Wales connecting to the ocean at Ballina, on the east coast of Australia (Fig. 1). The river flows into a wave-dominated barrier estuary that is permanently open to the ocean via twin breakwaters and estuarine training walls constructed over 100 years ago (Steffe et al. 2007). The surface area of the river is approximately 19 km2, a volume of 67.7 × 106 m3 and with a mean depth of 4.7 m (Eyre 2000). The Richmond River contains extensive coastal ecosystems such saltmarshes, mangroves, and seagrasses but also several other estuarine primary producers. The coastal floodplain is proportionally very large compared to other coastal catchments with 1024 km2 of the catchment at elevations between 10 m above mean sea level to mean sea level. Semidiurnal tides characterize the estuary ranging from 0.5–1.5 m for neap tides to 0.2–2 m for spring tides reaching up to 60 km inwards from the estuary mouth (Fury and Harrison 2011). The river surface area and its catchment support valuable commercial and recreational fisheries together which are of considerable social and economic importance to the region (Rotherham et al. 2011).

Fig. 1.

Map of Richmond river in Australia. Numbers 1–14 indicate locations where producers were collected (see Table 1 for number–producer correspondence). Letters A–E indicate consumer catch locations (see Table 2 for letter–consumer correspondence). Yellow star on the map represents Ballina and light green Lismore. Habitat extent of three main estuarine ecosystems (mangroves, saltmarsh, and seagrass—Zostera). See section Producers and Fish sample collection for more detailed description of sample collection

The management of Richmond River Estuary for its fishery as well as nature values more broadly has been a matter of great contention over the years, with various community groups often in conflict with each other, and with the local government, about stewardship. The Richmond River has many forms of agriculture within its catchment, as well as commercial and recreational fishing, and an important tourism industry. By now, much of the floodplain has been cleared for crops or grazing, with erosion from cleared lands and developing areas causing large quantities of sediment to be flushed into the river system (Wong et al. 2011). Towns such as Lismore and Ballina, are built on the riverbanks, causing strain on where floodwaters can go. As a result, human development on the riverbank combined with changing climate conditions have caused massive habitat losses for fish and other aquatic species, as well as terrestrial species that are crucial to the balance of the coastal riverine ecosystem (Rogers et al. 2016). Very extensive drainage of the large coastal floodplain has promoted the use for agriculture of former wetlands and the encroachment of plant species intolerant to periodic flooding. For example, during 2001 and in 2009 estuary-wide fish kills have occurred primarily due to low dissolved oxygen levels in the river following deep inundation of the floodplain where decomposition of inundation of vegetation intolerant to flooding has used the oxygen in the water and created a chemical oxygen demand (Walsh et al. 2004).

Primary producers

All samples were collected in February 2019 in the Richmond River Estuary. Throughout the estuary, nine primary producers were sampled across 14 different locations to provide spatial coverage of the estuarine system (see Fig. 1 for locations and Table 1 for producers). Most primary producers were sampled from at least five different locations (n = 3 per location) starting from the estuary mouth and gradually moving upstream. Sampling locations for each primary producer were determined by their spatial distribution within the estuary as well as the tidal limit—approximately 60 km upstream from the estuary mouth. Sampling primary producers throughout the estuary enables capture of a wide spatial gradient of primary producers and potentially better highlights intra-specific variability of stable isotope values (see Data Accessibility section for a spreadsheet: “rre_raw”). However, seagrass beds (Zostera capriconi) are only present in the vicinity of the estuary mouth, hence all the sampling locations for Z. capriconi are aggregated at that location. Ruppia spp. prefers less saline waters compared to Z. capriconi and was only accessible at one upstream location. Water couch (Paspalum distichum), was also only accessible from one location, as it is a fresh water species that only occurred in floodplain wetlands, remnant meadows and in pasture land that is prone to flooding. These floodplain habitats connect directly with the Richmond River during floods providing an avenue for nutrient flushing from Water couch habitat into the Richmond River. The mangrove and saltmarsh species together with the common reed (Phragmites australis) had the widest distribution within the estuary. All primary producers were collected by hand, using scissors to cut desired parts of the plants into oven bags that were placed into an icebox until further processing in the laboratory (always the same day) (Taylor et al. 2017). Fine particulate organic matter (FBOM) was sampled by washing the sediment through sieves (4, 1, 0.5 and 0.25 mm) (Raoult et al. 2018). The top layers of the sediment were placed into the sieves by using a small hand shovel and all the material contained in the smallest sieve was considered as FBOM.

Table 1.

Overview of sampled producers and sampling location. Location numbers correspond to the location number seen on Fig. 1

| Producers | Sampling location number |

|---|---|

| Zostera capricorni (seagrass) | 9–13 |

| Avicennia marina leaves + pneumatophores (mangrove) | 1–5 |

| Aegiceras corniculatum leaves (mangrove) | 2–6, 14 |

| Phragmites australis (Reed) | 1–7 |

| Juncus kraussii (tidal marsh) | 1–5 |

| Sporobolus virginicus (tidal marsh) | 1–5 |

| Fine Benthic Organic Matter (FBOM) | 1–7 |

| Ruppia spp. (seagrass) | 7 |

| Paspalum distichum (Water couch) | 8 |

Fish sample collection

Commercially important fisheries species in the region were identified by meeting with representatives from the local Ballina Fishermen’s Co-Operative who also provided the fish from their landed catch. By that time, all sampled fish had spent a considerable proportion of their life within the estuary because of their life-cycle stage and spawning period making them ideal candidates to study the relationships between estuarine producers and fish production (see Table 2 for the list of species). However, some of the sampled fish (e.g. Luderick and Yellowfin bream) can move considerable distances (> 100 km) along the coast mainly for spawning purposes; this migration takes place between May and July whereas our sampling was done in February.

Table 2.

List of fish species with sample size (n) and collection location. The sampled fish species are all targeted fisheries species for commercial fishers, a subset of the species (those identified with *) are also targeted by recreational fishers in the region

| Species | n | Location |

|---|---|---|

| Blacktip shark (Carcharhinus limbatus) | 7 | Broadwater (A) |

| Eastern king prawn* (Melicertus plebejus) | 15 | 6 miles offshore from Ballina (B) |

| Forktail catfish (Ariidae spp.) | 15 | Riley's Hill (C) |

| Luderick* (Girella tricuspidata) | 15 | Broadwater (A) |

| Mud crab* (Scylla serrata) | 15 | Pimlico Island (D) |

| Sea mullet (Mugil cephalus) | 15 | Bungawalbin Creek (E) |

| Yellowfin bream* (Acanthopagrus australis) | 15 | Riley's Hill (C) |

Laboratory processing

Sample preparation for stable isotope analysis took place at the Wollongbar Primary Industries Institute, northern New South Wales. Each producer and consumer sample was processed individually to isolate isotopic signatures. Macro-epiphytes were removed from all producer samples prior to analysis with distilled water spray and gentle scraping by hand. In fishes, equal amounts (at least 5 g) of dorsal white muscle tissue were removed, while cheliped muscle was used for the Mud crab, and muscle from the abdomen was used for prawns (Taylor et al. 2016). Tissues from producers and fish were rinsed using distilled water to remove surface contaminants and placed in individual HCl-cleaned Petri dishes and dried in an oven at 80 °C. Tissues from producers remained in an oven for at least 48 h and fish tissue was dried for at least 72 h (Taylor et al. 2016, 2017). Dried samples were then ground into fine powder and placed into plastic vials (2–5 g per sample) with tops sealed with parafilm to prevent any air and moisture exchange between the samples and the ambient environment. Sieved FBOM material was analysed similarly to other plant matter (Raoult et al. 2018). Ground and packed samples were sent to the University of Hawaii Hilo Analytical Laboratory for stable isotope analysis.

Samples in Hawaii were weighed and encapsulated based on sample and analysis type. For carbon and nitrogen samples, animal tissue was weighed between 0.5 and 1.0 mg, plant tissue was weighed between 2.0 and 3.0 mg. For sulphur samples, animal tissue was weighed ~ 10.000 mg, plant tissue was weighed ~ 20.000 mg and a scoop of vanadium pentoxide was added to all sulphur samples to aid in the combustion of the sample. Samples were then loaded into a Costech 4010 Elemental Combustion system. Carbon and nitrogen samples were combusted and carried through with helium gas to a reactor column and then a reduction column. The left furnace was set at 1000 °C, while the right furnace is set at 800 °C. The oven temperature was set at 55 °C. The sample was then carried to the Thermo Delta V, Isotope Ratio Mass Spectrometry, where it was analysed for δ13C and δ15N. For sulphur the sample was combusted using a pre-packed reactor and the oven temperature is 1020 °C. Based on the current level of knowledge there was no evidence that carbonate could have contributed to δ13C analysis. Lipids were not extracted prior to the analysis as conservative fixed discrimination factors were applied across proportional contributions (see e.g. Reich and Worthy, 2006; Caut et al. 2008; Martinez del Rio et al. 2009).

Data analysis

Proportional contributions

Bayesian stable isotope mixing models (Parnell 2019) were used to estimate proportional contributions of estuarine producers to fish diet in the Richmond River Estuary. The δ13C, δ15N and δ34S values of the basal food sources and consumers were analyzed using SIMMR package in R (Parnell 2019). The SIMMR package uses Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods to estimate parameters from observed data and provides the user with posterior probability distributions instead of single point estimates of source contributions (Parnell 2019). Posterior probability distributions can be considered analogous to confidence intervals in frequentist’s statistics. Thus, the main advantage of Bayesian mixing models is the ability to evaluate the likelihood for the proportion of a given producer in the fish diet by considering both the mean and standard deviation in source stable isotope ratios (see Data Accessibility for details). SIMMR model fit was evaluated with a posterior predictive check (Supplementary Material, Figs. S1, S2). This is similar to a fitted value plot in a linear regression. As data points (denoted by the plot as y) broadly lie in the fitted value intervals (denoted yrep; the default is a 50% interval) then the model can be considered to be a good fit. Posterior predictive check indicated that a model fit containing δ13C and δ34S isotopes was better than a model containing δ13C and δ15N isotopes. δ13C and δ34S isotopes indicates a much narrower and tighter fit of observed and fitted values compared to δ13C and δ15N isotopes (Brown et al. 2018). Thus, all stable isotope analysis in this manuscript were performed with δ13C and δ34S isotopes.

Realized dietary niche

The isotopic realized dietary niche of seven important fisheries species was outlined by applying Stable Isotope Bayesian Ellipses (SIBER; Jackson et al. 2011). Niche space of species is defined by the standard ellipse area (SEA) as the area occupied in bi‐plot space in ‰. SIBER uses a multivariate ellipse-based approach to generate corrected SEA (SEAc) preventing the interference of sample sizes and outliers inherent to convex hulls (Jackson et al. 2011). The SEAc, representing the core isotopic niche area (containing 40% of the data, as opposed to the convex hull which includes 100% of the data), allows the comparison of groups with different sample sizes (Jackson et al. 2011). A SEAc estimate for each group is made by a Bayesian iterative process based on a subsample of the group’s stable isotope values, considering the uncertainty in the sampled data (Jackson et al. 2011). In the results section, corrected standard ellipse area (SEAc) and convex hulls are displayed, because it s useful to visualise both the core niche space as well as the total niche space area of consumers.

Economic valuation

New South Wales Department of Primary Industries fisheries dataset (2009–2019) from the Richmond River Estuary was used to calculate average annual catch (kg) and average dollar values ($AU) for each of the seven fisheries species that were analyzed with stable isotopes. This dataset is composed of catch information that commercial fishers are required to report to the Department of Primary Industries. We applied the proportional dietary contributions of estuarine producers to fisheries species, with the average annual catch and value data to estimate the proportion of total catch and value distributable for each estuarine producer:

where GVPp,s is the average gross value product (GVP) of an estuarine producer p derived from commercially harvested fish species s, Cp,s is the average contribution (C) of an estuarine producer p to consumer species s, AACVs is the average annual catch value for fish species s.

We assumed that the entire harvestable fish population benefited from the producers that the isotope results indicated, even though stable isotope analysis was only done on harvestable size fish. We have not included a valuation of the contribution to recreational fisheries, due to a lack of data at the estuary scale. By not incorporating estimates of recreational fisheries value, our estimated economic values of coastal ecosystems are conservative [all monetary values are expressed in Australian dollars ($ AUD) throughout the manuscript reflecting an average of the previous 3 years]. Across NSW the recreational fishery for Mud crab and Eastern king prawn is much smaller than the commercial catch (https://www.fish.gov.au/report/155-MUD-CRABS-2018?jurisdictionId=5 and https://www.fish.gov.au/report/172-Eastern-King-Prawn-2018?jurisdictionId=5), slightly less than the commercial catch for Luderick (https://www.fish.gov.au/report/235-Luderick-2018?jurisdictionId=5) and double the commercial catch for Yellowfin Bream (https://www.fish.gov.au/report/232-Yellowfin-Bream-2018?jurisdictionId=5).

All analyses of this manuscript were conducted using R statistical package version 3.3.3 and RStudio version 1.0.136.

Results

Proportional contributions

Proportional contributions of estuarine producers were considered as potential basal food sources for five fish species, one prawn and one crab based on their δ13C and δ34S values (Fig. 2). SIMMR analysis showed that tidal marsh species (Sporobolus virginicus and Juncus kraussii) and seagrass (Zostera and Ruppia spp.) were the most important estuarine producers as they resulted in highest individual contributions to six out of seven species (Table 3). Some of the highest producer specific median contributions originated from Zostera (seagrass) to Blacktip shark (61.8%) and from Ruppia spp. (seagrass) to Forktail catfish (49.4%) (Table 3). Ruppia spp. was also the highest contributor to Luderick with 24.9%. Tidal marsh S. virginicus had the highest single median contribution to the Eastern king prawn (68.1%) and the Mud crab (27.6%). Tidal marsh J. kraussii was the highest contributor to Sea mullet (12.6%) and Grey mangrove pneumatophores were the most important contributor to Yellowfin bream (17.4%). Phragmites, Water couch and FBOM had the lowest overall detected dietary contribution values. Species specific posterior probability distributions of each dietary source with confidence intervals can be seen on Figs. S3, S4, S5, S6, S7, S8 and S9 in Supplementary Materials.

Fig. 2.

Isospace plot of estuarine producers (n = 10) and consumers (n = 7) in Richmond River Estuary based on carbon and sulphur isotope values

Table 3.

Stable isotope analysis in R (SIMMR) results of median food source proportions of estuarine producers to fish production based on Bayesian modelling output. The highest contributing sources to each fish species have been outlined in bold. Source specific variation of proportional contributions of each fisheries species can be found in Supplementary Materials (Figs. S3, S4, S5, S6, S7, S8 and S9)

| Source | Blacktip shark | Eastern king prawn | Forktail catfish | Luderick | Mud crab | Sea mullet | Yellowfin bream |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FBOM | 1.9 | 1 | 2.4 | 2.1 | 3.6 | 4 | 3.8 |

| Grey mang leaves | 2.4 | 2 | 5.7 | 8.4 | 4.7 | 10.6 | 11.3 |

| Grey mang pneum | 2.5 | 1.8 | 7.9 | 5.8 | 4.7 | 9.7 | 17.4 |

| River mang leaves | 2.3 | 1.9 | 5.1 | 8.8 | 4.1 | 10 | 9.3 |

| Juncus kraussii | 2.5 | 2.4 | 5 | 18.5 | 4.8 | 12.6 | 9.5 |

| Phragmites | 2.2 | 1.5 | 2.7 | 3.9 | 4.3 | 6.4 | 4.3 |

| Ruppia | 3.8 | 10.5 | 49.4 | 24.9 | 7.1 | 8.5 | 16.4 |

| Sporobolus virginicus | 8.4 | 68.1 | 5.4 | 6.7 | 27.6 | 6.6 | 7.5 |

| Water couch | 2.4 | 1.1 | 8.2 | 1.9 | 5.6 | 3.6 | 6.9 |

| Zostera sp. | 61.8 | 5.4 | 3.9 | 3.8 | 24.2 | 5.1 | 5.2 |

*All reported stable isotope results are based on the total of 256 individual samples of producers and fish (see “Data accessibility” section for raw data)

Realized dietary niche of consumers

SIBER analysis using convex hull areas and standard ellipses revealed relatively small isotopic realized niche amongst some fish such as the Blacktip shark and Eastern king prawn (Figs. S3, S4—Supplementary Material). Whereas fish such as Luderick and Sea mullet had wide and overlapping niche spaces with other species (Fig. 3). The realized niche space width is also reflected by the distribution and relative contribution of individual sources as species like Luderick, Yellowfin bream and Sea mullet have more even spread of proportional contributions resulting in wider niche space (Table 3).

Fig. 3.

SIBER output δ13C and δ34S biplot of all the fish incorporated in the analysis. Convex hulls areas (solid lines) and ellipses (dotted lines) represent the calculated isotopic feeding niche widths of each species. The ellipse represents 40% of the data points whereas convex hulls represent 100% of data spread

Economic valuation

In the Richmond River Estuary, seven fish species of commercial relevance with an average annual catch of 82 745 kg and a value of $AU 450 117 were supported by estuarine producers (Table 4). This estimation is based on the isotope data. The highest quantity of catch 93 805 kg (87%) and value $AU 216 444 (54%) per year originated from Sea mullet. Mud crab was the second highest contributor with 7020 kg (7%) and a value of $AU 193 099 (35%) (Table 4). Sea mullet and Mud crab combined contributed 95% of total catch and 93% of total value assigned to estuarine producers (Table 4). Tidal marsh J. kraussii supported the highest amount of fish biomass production (12 521 kg) whereas the highest dollar value was assigned to the other tidal marsh species S. virginicus $AU 82 423 (Table 4). However, the majority of the Eastern king prawn in the Richmond River region is caught outside of the estuary between latitudes 29.0′ S and 29.9′ S. If we incorporated an average 3-year catch (155.6 tonnes) into our economic framework then an additional 3.9 million AUD (866% increase in AUD value) could be distributed between estuarine producers with S. virginicus being valued up to 2.67 million AUD. We did not include the Eastern king prawn in our analysis as the data is about ocean catch, it is impossible to be definitive about which estuary the prawns originated from but considering the catch area it is most likely to be the Richmond or Evans Estuary. Despite the definitive origin of prawns, it is crucial to emphasize the importance of S. virginicus to the Eastern king prawn in north-east Australia.

Table 4.

Annual catch in kilos (kg) per year and value ($AUD) per year in Richmond River Estuary distributable to estuarine producers based on fish‐specific proportional contributions. The highest contributing sources to each fish species have been outlined in bold

| Source | Blacktip shark | Eastern king prawn | Forktail catfish | Luderick | Mud crab | Sea mullet | Yellowfin bream | Source total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FBOM | 9 ($31) | 4 ($97) | 35 ($145) | 17 ($33) | 253 ($6952) | 3752 ($12 569) | 48 ($614) | 4118 ($20 422) |

| Grey mang leaves | 11 ($39) | 8 ($194) | 83 ($345) | 68 ($134) | 330 ($9076) | 9943 ($33 308) | 144 ($1827) | 10 587 ($44 922) |

| Grey mang pneum | 12 ($31) | 7 ($175) | 115 ($477) | 47 ($92) | 330 ($9076) | 9099 ($30 408) | 221 ($2813) | 9832 ($43 154) |

| River mang leaves | 11 ($37) | 8 ($185) | 74 ($308) | 71 ($140) | 288 ($7917) | 9381 ($31 423) | 118 ($1504) | 9951 ($41 514) |

| Juncus kraussii | 12 ($41) | 10 ($233) | 73 ($302) | 149 ($295) | 337 ($9269) | 11 819 ($39 529) | 121 ($1536) | 12 521 ($51 268) |

| Phragmites | 10 ($36) | 6 ($146) | 39 ($163) | 31 ($62) | 302 ($8303) | 6004 ($21 110) | 55 ($659) | 6447 ($29 516) |

| Ruppia | 18 ($62) | 42 ($1020) | 722 ($2986) | 201 ($397) | 498 ($13 710) | 7973 ($26 709) | 209 ($2651) | 9662 ($47 535) |

| Sporobolus virginicus | 40 ($137) | 270 ($6615) | 79 ($326) | 54 ($107) | 1937 ($53 295) | 6191 ($20 739) | 95 ($1213) | 8667 ($82 432) |

| Water couch | 11 ($39) | 4 ($107) | 120 ($496) | 15 ($30) | 393 ($10 814) | 3377 ($11 312) | 88 ($1116) | 4009 ($23 913) |

| Zostera sp. | 239 ($1006) | 21 ($525) | 57 ($236) | 31 ($61) | 1699 ($46 730) | 4784 ($16 025) | 66 ($841) | 6951 ($65 423) |

Discussion

Main findings and bigger picture

In this study we sampled and then modelled the relative contribution of eleven estuarine primary producers to fisheries diet in the Richmond River Estuary—a region of significant socio-economic importance on the east coast of Australia. δ13C and δ34S isotope values found in producer and consumer tissues indicated a large contribution of seagrass (Z. capricorni and Ruppia spp.) and saltmarsh (S. virginicus) as a dietary source for fish (5 out of 7 species). The highest producer specific median contribution originated from Z. capricorni to Blacktip shark (61.8%). Overall, we estimated that primary producers (seagrass meadows, tidal marshes, mangrove forests) within Richmond River support 82 754 kg (or 78%) of annual estuary caught commercial catch with an estimated annual value of $AU 450 117. This is important because from the perspective of fisheries sustainability, management priorities and resource allocation, it is important to acknowledge the relationships fish have with coastal ecosystems.

Specialist consumers are of particular interest because of their closely associated links to specific estuarine producers. Given these close associations it is clear that any loss of an estuarine producers may significantly impact fisheries production. For example, the Eastern king prawn receives a large dietary contribution from trophic pathways that rely on S. virginicus (68.1%), thus, it is important to maintain/protect tidal marsh ecosystems to ensure the presence of prawns in the estuary (Jänes et al. 2020a). This is because Eastern king prawn appears to be more of a specialist consumer in particularly consuming prey that in turn have large proportions of S. virginicus in their diet. Thus, if S. virginicus were to disappear from the estuary, which already has a limited distribution in the lower part of the estuary, then Eastern king prawn might also disappear from the system. Blacktip shark is similarly a more specialist consumer, as it receives 61.8% of dietary input from Z. capricorni and to Forktail catfish which receives half (49.4%) of its diet from Ruppia spp. The Mud crab receives 25% and 27% from Zostera and S. virginicus, respectively and can also be considered as a specialist species. Thus, from a longevity and sustainability perspective of these four fisheries, it is important to sustain fisheries production values by maintaining (or increasing) the presence of seagrass (Zostera and Ruppia) and tidal marsh (S. virginicus) in the Richmond River Estuary. On the contrary, Luderick, Sea mullet and Yellowfin bream all displayed a relatively even spread of dietary contributions as no single source was as heavily dominating perhaps indicating their generalist feeding behaviour as a species.

Standard ellipses (Fig. 3) revealed relatively small isotopic niche width and overlap amongst some species (Blacktip shark and Eastern king prawn) whereas Luderick and Sea mullet had wide and overlapping niche spaces with other species. Species realized niche space width and overlap could indicate potential vulnerability of species to changing environmental conditions or habitat degradation. Species with smaller and overlapping niches could be more affected if unexpected shifts in basal autotrophs occur. This is because smaller niche is likely linked to specialist behaviour and a high degree of niche space overlap suggest increased competition for resources which both increase species-specific vulnerability (Jänes et al. 2015). However, in order to provide more coherent conclusions about dietary niche space dimensions of species investigated in this study, we would need to replicate the analytical niche space approach in nearby estuarine systems.

Previous research has documented that tidal marsh S. virginicus is the dominant contributor (53%) to Eastern king prawn production near Sydney (Hewitt et al. 2020), which also correlates with our findings in regard to the importance of S. virginicus (68%). Furthermore, in the neighbouring Clarence and Hunter River Estuaries earlier findings suggest that estuarine producers such as tidal marsh and mangroves produce similar monetary value input from Sea mullet, Yellowfin bream and Luderick compared to our study (Taylor et al. 2018; Jänes et al. 2020a). However, the relatively minor monetary contribution of Eastern king prawn in our study deviates from previous findings where it has been documented that across Australia Eastern king prawns provide some of the highest monetary values to coastal vegetated ecosystems at a value of 13.6 million dollars per year (Jänes et al. 2020a). This is because we used fisheries catch data originating from Richmond River Estuary and prawn trawling fishing method is not used in the Richmond Estuary, consequently only a relatively small proportion of Eastern king prawns are actually caught within the estuary. The majority of prawn catches occur a few kilometres offshore and thus it is impossible to distinguish which estuary the prawns originated from (Taylor and Johnson 2020). With that said, our findings do provide good indication that prawns emigrating to the open waters from Richmond River Estuary display close relationships and receive notable dietary input from tidal marsh S. virginicus.

Challenges and future directions

The ongoing evolution of tracer mixing models has resulted in an array of software tools that differ in terms of model assumptions and associated input variables. Here we used the most recent Bayesian tracer (e.g. stable isotope) mixing model framework implemented as an open-source R package (Parnell 2019). Using SIMMR and SIBER as a foundation, we provided a detailed description of methodologies and how to apply the most up to date and commonly used mixing model analyses to biological data. Despite the advancements of mixing models, many study systems might have source isotope signatures that overlap broadly in isotope space and still hinder source discrimination. δ13C is commonly used as an isotope tracer, but it can struggle to separate certain species of saltmarsh and seagrass as well as some species of saltmarsh and mangroves (Raoult et al. 2018). This adds a degree of uncertainty from the original studies, specifically, in areas where ecosystems that are difficult to separate are co-occurring. It is important to bear in mind that mixing models are distributions that may have small or large error margins, and in some cases bimodality. Variation in model values is a crucial aspect for interpreting mixing models. Assessments where 90% of model predictions are within 2–3% of the median suggest consistent reliance on the ecosystem whereas models with large error margins (e.g. 30%) around the median indicate variation and possibly broader dietary preference among a population (Supplementary Material, Figs. S3, S4, S5, S6, S7, S8 and S9). For example, when observing Blacktip sharks, one could see that the median contribution of Zostera is around 58%, however, the length of error margins is quite substantial indicating somewhat large individual variability in relation to Zostera consumption. When the reader would look at the importance of Phragmites to Blacktip sharks, it becomes clear that the median contribution is negligible and the error margins are small. However, mixing models can be improved and the aforementioned shortcomings partially alleviated by using δ34S as a third tracer instead of δ15N in addition to commonly used δ13C and δ15N (Connolly et al. 2004).

In the current study the SIMMR model fit (Supplementary Material, Figs. S1, S2) was notably improved when using δ13C and δ34S for determining species specific proportional contributions as opposed to δ13C and δ15N on their own. Hence, we recommend incorporating sulphur in the analytical framework where possible, however, with current price standards, it will double overall research costs (analysis for sulphur isotopes is as expensive as carbon and nitrogen combined). This is because carbon and nitrogen isotopes can be analysed from the same sample whereas sulphur isotopes require an additional sample. However, incorporating sulphur did not affect the overall trends in terms of which producers had the highest or lowest fisheries specific proportional contributions or which species appeared generalist or specialist. Rather incorporating sulphur simply improved the model fit and reduced variation when discriminating between source contributions.

Estuarine primary producers such as aquatic macrophytes support fish through both dietary contribution (studied here) and nursery/habitat provision (Whitfield 2017). Here, we assign all of the commercial catch value based on dietary contribution which does not account for the habitat contribution in the form of residence area. For example, tidal marsh provides important dietary contribution for many fisheries species, but it is too high in the intertidal zone for the majority of fish to access. Thus, fish unable to access the tidal marsh likely occupy another habitat in lower inter—or subtidal zone for residence area. Furthermore, with stable isotopes it is difficult to quantify nursery values of coastal ecosystems, in the case where juveniles are not sampled and the majority of studies focus on adults, presumably to do their more relevant linkage to fish catch. Whilst our research sampled harvestable size fish, sampling of fish throughout various life-stages (e.g. recruits, juveniles, and adults) would provide new insights to better characterize nutritional pathways throughout a species life-cycle (Carseldine and Tibbetts 2005). As a result, it would be possible to highlight when and if dietary switches occur and how fish depend on different ecosystems at different stages of their life cycle. This would enable us to apportion the commercial catch value based on multiple life stages and would be particularly important for species that undergo large ontogenetic dietary shifts throughout their life-cycle.

Considering life histories and species-specific movement patterns of fish enables us to better understand the connectivity between coastal ecosystems and fish populations at various spatial scales. For example, Luderick undertakes spawning migrations along the coast of New South Wales between May and July, travelling in a northerly direction along beaches (Curley et al. 2013; Ferguson et al. 2013). Whereas, tagging research has shown that juveniles and adults of Yellowfin bream generally moved at scales < 6 km, although some large-scale movements (10–90 km) of adults appeared to be associated with migrations to or from spawning areas (Curley et al. 2013). Recent work from Taylor et al. (2016, 2017) sets a good example of how quantifying numerical abundance of prawns with netting and linking it with fine scale stable isotope analysis can help deciphering the source of migrating adult prawns caught at the estuary mouth. Despite these recent efforts, we are still lacking a solid framework under which dietary information coupled with other tracer methods such as tagging and routine netting could be combined. As such, further consideration of the consumer habitat and fish potential to forage along the coastline is important to fisheries managers for better understanding spatiotemporal dynamics between fish populations and coastal ecosystems.

Conclusions

Here, we have assessed the relative contribution of estuarine primary producers to fisheries production combined with market prices in Richmond River Estuary, Australia. Furthermore, we also quantified dietary niche spaces of fish based on proportional contributions from estuarine primary producers. Outlining relationships between estuarine primary producers and fisheries production can improve fisheries and fish habitat management. It can also help resource users (commercial and recreational fishers), secondary beneficiaries (tourism industries) and coastal communities build their understanding and appreciation of the links and dependence of economies, social and cultural values on natural infrastructure. It can also help decision makers prioritize often limited resources on conservation and rehabilitation measures because of the wide range of values that can be protected and reinstated. More quantitative data on the links can lead to decisions that are more informed, have broad stakeholder and community support and are defendable.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

These works are part of The Nature Conservancy's Great Southern Seascapes and Mapping Ocean Wealth Programme and supported by The Thomas Foundation, HSBC Australia, the Ian Potter Foundation, and Victorian and New South Wales governments including Parks Victoria, Department of Environment Land Water and Planning, Victorian Fisheries Authority, New South Wales Office of Environment and Heritage, and New South Wales Department of Primary Industries. Funding was also provided by an Australian Research Council Linkage Project (LP160100242). The assistance of the Ballina Fishermen’s Cooperative and its estuary fishers is appreciated and acknowledged.

Biographies

Holger Jänes

Research areas include fisheries science and ecosystem services.

Peter I. Macreadie

is a Researcher at Deakin University. His research includes coastal ecosystems and blue carbon.

Justin Rizzari

is a Researcher at Deakin University. His research focuses of fisheries science.

Daniel Ierodioconou

is a Researcher at Deakin University. His research focuses on marine spatial mapping and management.

Simon E. Reeves

is a Researcher and Project Manager at the Nature Conservancy. His research investigates coastal resource management.

Patrick G. Dwyer

is a Senior Manager of Coastal Systems in New South Wales, Australia. He has an outstanding expertise and knowledge about estuarine systems in north-east Australia.

Paul E. Carnell

is a Researcher at Deakin University. His research focuses on blue carbon and coastal ecosystem.

Data accessibility

All raw data is accessible through online data storage website CloudStor: https://cloudstor.aarnet.edu.au/plus/s/ohWs7OwCoEdaQfh. R script is available upon request.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Holger Jänes, Email: holger.janes@ut.ee.

Peter I. Macreadie, Email: p.macreadie@deakin.edu.au

Justin Rizzari, Email: justin.rizzari@deakin.edu.au.

Daniel Ierodioconou, Email: daniel.ierodioconou@deakin.edu.au.

Simon E. Reeves, Email: simon.reeves@TNC.ORG

Patrick G. Dwyer, Email: patrick.dwyer@dpi.nsw.gov.au

Paul E. Carnell, Email: paul.carnell@deakin.edu.au

References

- Barbier EBEB, Hacker SDSD, Kennedy C, Koch EWEW, Stier ACAC, Silliman BRBR. The value of estuarine and coastal ecosystem services. Ecological Monographs. 2011;81:169–193. doi: 10.1890/10-1510.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Broennimann O, Fitzpatrick MC, Pearman PB, Petitpierre B, Pellissier L, Yoccoz NG, Thuiller W, Fortin M, Randin C, Zimmermann NE, Graham CH, Guisan A. Measuring ecological niche overlap from occurrence and spatial environmental. Global Ecology and Biogeography. 2012;21:481–497. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-8238.2011.00698.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown EJ, Vasconcelos RP, Wennhage H, Bergström U, Støttrup JG, van de Wolfshaar K, Millisenda G, Colloca F, Le Pape O. Conflicts in the coastal zone: Human impacts on commercially important fish species utilizing coastal habitat. ICES Journal of Marine Science. 2018;75:1203–1213. doi: 10.1093/icesjms/fsx237. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cadigan KM, Fell PE. Reproduction, growth and feeding habits of Menidia menidia (Atherinidae) in a tidal marsh-estuarine system in southern New England. ASIH. 1985;1:21–26. doi: 10.2307/1444786. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carseldine L, Tibbetts IR. Dietary analysis of the herbivorous hemiramphid Hyporhamphus regularis ardelio: An isotopic approach. Journal of Fish Biology. 2005;66:1589–1600. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-1112.2005.00701.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Caut S, Angulo E, Courchamp F. Caution on isotopic model use for analyses of consumer diet. Canadian Journal of Zoology. 2008;86:438–445. doi: 10.1139/Z08-012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Christianen MJA, Middelburg JJ, Holthuijsen SJ, Jouta J, Compton TJ, van der Heide T, Piersma T, Sinninghe Damsté JS, van der Veer HW, Schouten S, Olff H. Benthic primary producers are key to sustain the Wadden Sea food web: Stable carbon isotope analysis at landscape scale. Ecology. 2017;98:1498–1512. doi: 10.1002/ecy.1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coetzee DJ. Stomach content analysis of the leervis, Lichia amia (L.), from the Swartvlei system, southern Cape. South African Journal of Zoology. 1982;17:177–181. doi: 10.1080/02541858.1982.11447800. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly RM. Differences in trophodynamics of commercially important fish between artificial waterways and natural coastal wetlands. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science. 2003;58:929–936. doi: 10.1016/j.ecss.2003.06.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly RM, Guest MA, Melville AJ, Oakes JM. Sulfur stable isotopes separate producers in marine food-web analysis. Oecologia. 2004;138:161–167. doi: 10.1007/s00442-003-1415-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corry M, Harasti D, Gaston T, Mazumder D, Cresswell T, Moltschaniwskyj N. Functional role of the soft coral Dendronephthya australis in the benthic food web of temperate estuaries. Marine Ecology Progress Series. 2018;593:61–72. doi: 10.3354/meps12498. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cresson P, Ruitton S, Ourgaud M, Harmelin-Vivien M. Contrasting perception of fish trophic level from stomach content and stable isotope analyses: A Mediterranean artificial reef experience. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology. 2014;452:54–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jembe.2013.11.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Curley BG, Jordan AR, Figueira WF, Valenzuela VC. A review of the biology and ecology of key fishes targeted by coastal fisheries in south-east Australia: Identifying critical knowledge gaps required to improve spatial management. Review in Fish Biology and Fisheries. 2013;23:435–458. doi: 10.1007/s11160-013-9309-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Deegan LA, Garritt RH. Evidence for spatial variability in estuarine food webs. Marine Ecology Progress Series. 1997;147:31–47. doi: 10.3354/meps147031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eyre BD. Regional evaluation of nutrient transformation and phytoplankton growth in nine river-dominated sub-tropical east Australian estuaries. Marine Ecology Progress Series. 2000;205:61–83. doi: 10.3354/meps205061. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson AM, Harvey ES, Taylor MD, Knott NA. A herbivore knows its patch: Luderick, Girella tricuspidata, exhibit strong site fidelity on shallow subtidal reefs in a temperate marine park. PLoS ONE. 2013 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fury CA, Harrison PL. Seasonal variation and tidal influences on estuarine use by bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops aduncus) Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science. 2011;93:389–395. doi: 10.1016/j.ecss.2011.05.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia AM, Claudino MC, Mont’Alverne R, Pereyra PER, Copertino M, Vieira, JP. Temporal variability in assimilation of basal food sources by an omnivorous fish at Patos Lagoon Estuary revealed by stable isotopes (2010–2014) Marine Biology Research. 2017 doi: 10.1080/17451000.2016.1206939. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goulstone, A. 1993. Development and status of the Ballina district prawn fishery. Faculty of Resource Science and Management: University of New England-Northern Rivers.

- Harrison, J. 2010. A socio-economic evaluation of the commercial fishing industry in the Ballina, Clarence and Coffs Harbour regions. FRDC Project No. 2009/054. Professional Fishermen’s Association, Inc.

- Hewitt DE, Smith TM, Raoult V, Taylor MD, Gaston TF. Stable isotopes reveal the importance of saltmarsh-derived nutrition for two exploited penaeid prawn species in a seagrass dominated system. Estuarine Coastal and Shelf Science. 2020;236:106622. doi: 10.1016/j.ecss.2020.106622. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson AL, Inger R, Parnell AC, Bearhop S. Comparing isotopic niche widths among and within communities: SIBER—Stable Isotope Bayesian Ellipses in R. Journal of Animal Ecology. 2011;80:595–602. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2656.2011.01806.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jänes H, Kotta J, Herkül K. High fecundity and predation pressure of the invasive Gammarus tigrinus cause decline of indigenous gammarids. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science. 2015;165:185–189. doi: 10.1016/j.ecss.2015.05.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jänes H, Macreadie PI, Nicholson E, Ierodioconou D, Reeves S, Taylor MD, Carnell PE. Stable isotopes infer the value of Australia’s coastal vegetated ecosystems from fisheries. Fish and Fisheries. 2020;21:80–90. doi: 10.1111/faf.12416. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jänes H, Macreadie PI, Zu Ermgassen PSE, Gair JR, Treby S, Reeves S, Nicholson E, Ierodiaconou D, Carnell P. Quantifying fisheries enhancement from coastal vegetated ecosystems. Ecosystem Services. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ecoser.2020.101105. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jennings S, Reñones O, Morales-Nin B, Polunin NVC, Moranta J, Coll J. Spatial variation in the 15N and 13C stable isotope composition of plants, invertebrates and fishes on Mediterranean reefs: Implications for the study of trophic pathways. Marine Ecology Progress Series. 1997;146:109–116. doi: 10.3354/meps146109. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Le DQ, Tanaka K, Hii YS, Sano Y, Nanjo K, Shirai K. Importance of seagrass–mangrove continuum as feeding grounds for juvenile pink ear emperor Lethrinus lentjan in Setiu Lagoon, Malaysia: Stable isotope approach. Journal of Sea Research. 2018;135:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.seares.2018.02.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lotze HK, Lenihan HS, Bourque BJ, Bradbury RH, Cooke RG, Kay MC, Kidwell SM, Kirby MX, Peterson CH, Jackson JBC. Depletion, degradation, and recovery potential of estuaries and coastal seas. Science. 2006 doi: 10.1126/science.1128035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marley G, Lawrence AJ, Phillip DAT, Hayden B. Mangrove and mudflat food webs are segregated across four trophic levels, yet connected by highly mobile top predators. Marine Ecology Progress Series. 2019;632:13–25. doi: 10.3354/meps13131. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez del Rio C, Wolf N, Carleton S, Gannes L. Isotopic ecology ten years after a call for more laboratory experiments. Biological Reviews. 2009;84:91–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-185X.2008.00064.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parnell, A. 2019. SIMMR: A Stable Isotope Mixing Model. R package version 0.4.1.

- Qiu J, Carpenter SR, Booth EG, Motew M, Zipper SC, Kucharik CJ, Loheide II SP, Turner MG. Understanding relationships among ecosystem services across spatial scales and over time. Environmental Research Letters. 2018 doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/aabb87. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips DL, Inger R, Bearhop S, Jackson AL, Moore JW, Parnell AC, Simmens BX, Ward EJ. Best practices for use of stable isotope mixing models in food-web studies. Canadian Journal of Zoology. 2014;9:823–835. doi: 10.1139/cjz-2014-0127. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Raoult V, Gaston TF, Taylor MD. Habitat–fishery linkages in two major south-eastern Australian estuaries show that the C4 saltmarsh plant Sporobolus virginicus is a significant contributor to fisheries productivity. Hydrobiologia. 2018;811:221–238. doi: 10.1007/s10750-017-3490-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Raudsepp-Hearne C, Peterson GD. Scale and ecosystem services: How do observation, management, and analysis shift with scale—Lessons from Quebec. Ecology and Society. 2016 doi: 10.5751/ES-08605-210316. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reich KJ, Worthy GAJ. An isotopic assessment of the feeding habits of free-ranging manatees. Marine Ecology Progress Series. 2006;322:303–309. doi: 10.3354/meps322303. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers K, Knoll EJ, Copeland C, Walsh S. Quantifying changes to historic fish habitat extent on north coast NSW quantifying changes to historic fish habitat extent on north coast NSW flood plains, Australia. Regional Environmental Change. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s10113-015-0872-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rotherham D, Macbeth WG, Kennelly SJ, Gray CA. Reducing uncertainty in the assessment and management of fish resources following an environmental impact. ICES Journal of Marine Science. 2011;68:1726–1733. doi: 10.1093/icesjms/fsr079. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Steffe AS, Macbeth WG, Murphy JJ. Status of the recreational fisheries in two Australian coastal estuaries following large fish-kill events. Fisheries Research. 2007;85:258–269. doi: 10.1016/j.fishres.2007.02.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor MD, Johnson DD. Evaluation of adaptive spatial management in a multi-jurisdictional trawl fishery. Regional Studies in Marine Science. 2020;35:101206. doi: 10.1016/j.rsma.2020.101206. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor MD, Smith JA, Boys CA, Whitney H. A rapid approach to evaluate putative nursery sites for penaeid prawns. Journal of Sea Research. 2016;114:26–31. doi: 10.1016/j.seares.2016.05.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor MD, Fry B, Becker A, Moltschaniwskyj N. Recruitment and connectivity influence the role of seagrass as a penaeid nursery habitat in a wave dominated estuary. Science of the Total Environment. 2017;584–585:622–630. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.01.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor MD, Gaston TF, Raoult V. The economic value of fisheries harvest supported by saltmarsh and mangrove productivity in two Australian estuaries. Ecological Indicators. 2018;84:701–709. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolind.2017.08.044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, S., C. Copeland, and M. Westlake. 2004. Major fish kills in the northern rivers of NSW in 2001: Causes, impacts and responses: 55. Fisheries Final Report Series, No. 68. New South Wales Department of Primary Industries, Ballina.

- Wang S, Liu G, Yuan Z, Lam PKS. Occurrence and trophic transfer of aliphatic hydrocarbons in fish species from Yellow River Estuary and Laizhou Bay, China. Science of the Total Environment. 2019 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.134037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Webb BF. Fish populations of the Avon-Heathcote Estuary. New Zealand Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research. 1973;7:223–234. doi: 10.1080/00288330.1973.9515469. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Whitfield AK. The role of seagrass meadows, mangrove forests, salt marshes and reed beds as nursery areas and food sources for fishes in estuaries. Review in Fish Biology and Fisheries. 2017;27:75–110. doi: 10.1007/s11160-016-9454-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wong VNL, Johnson SG, Burton ED, Bush RT, Sullivan LA, Slavich PG. Anthropogenic forcing of estuarine hypoxic events in sub-tropical catchments: Landscape drivers and biogeochemical processes. Science of the Total Environment. 2011;409:5368–5375. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2011.08.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All raw data is accessible through online data storage website CloudStor: https://cloudstor.aarnet.edu.au/plus/s/ohWs7OwCoEdaQfh. R script is available upon request.