Abstract

Currently, approximately 150 different brain tumour types are defined by the WHO. Recent endeavours to exploit machine learning and deep learning methods for supporting more precise diagnostics based on the histological tumour appearance have been hampered by the relative paucity of accessible digital histopathological datasets. While freely available datasets are relatively common in many medical specialties such as radiology and genomic medicine, there is still an unmet need regarding histopathological data. Thus, we digitized a significant portion of a large dedicated brain tumour bank based at the Division of Neuropathology and Neurochemistry of the Medical University of Vienna, covering brain tumour cases from 1995–2019. A total of 3,115 slides of 126 brain tumour types (including 47 control tissue slides) have been scanned. Additionally, complementary clinical annotations have been collected for each case. In the present manuscript, we thoroughly discuss this unique dataset and make it publicly available for potential use cases in machine learning and digital image analysis, teaching and as a reference for external validation.

Subject terms: CNS cancer, Cancer in the nervous system, Cancer microenvironment, CNS cancer

| Measurement(s) | Cancer Histology • Cellularity Measurement • Total Sample Tissue Area • brain neoplasm |

| Technology Type(s) | Hematoxylin and Eosin Staining Method • digital curation • Histology and Immunohistochemistry Shared Resource |

| Factor Type(s) | age • sex • location |

| Sample Characteristic - Organism | Homo sapiens |

Machine-accessible metadata file describing the reported data: 10.6084/m9.figshare.16652272

Background & Summary

Brain tumours account for a large fraction of years of potential life lost as compared with tumours from other sites1, and have a significant negative impact on patients’ quality of life2. Overall, they are relatively uncommon neoplasms with an incidence of approximately 24 per 100.000 person-years3. Current diagnostic guidelines published by the WHO define approximately 150 distinct brain tumour types and assign grades I to IV, based on malignancy and potential to malignant transformation or progression. They are mainly differentiated by their histopathological phenotypes and molecular alterations4. While the majority of tumours is diagnosed solely based on histopathology, an integrated approach is mandatory for 19 tumour types.

Still, more accurate diagnostic distinctions are needed in order to i) better assess individual patients’ prognoses and ii) support more robust therapeutic decisions4,5. Recently, diagnostic algorithms trained on DNA methylation data have been shown to significantly increase diagnostic accuracy6. Similar advances focusing on histopathological data have been hampered, so far, by the lack of freely available histopathology datasets7. Most available histopathology data such as those available through TCGA8, IvyGAP9,10 or TCIA11 focus on only a few diagnostic entities. They mostly consist of digitized fresh frozen tissue sections, which feature relatively poor tissue morphology as compared to formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded tissues. Still, even with these limited data, computational algorithms have been successfully trained - amongst others - for survival prediction12, detection of tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes13, and assessments of tumour microvessels14. However, larger datasets encompassing an even wider range of brain tumours and featuring improved cellular and morphological characteristics are necessary to further develop these algorithms and extend their applicability to the entire spectrum of brain tumour types.

Thus, we set out to compile a comprehensive resource of digitized Haematoxylin-eosin(H&E)-stained brain tumour whole slide images (WSIs) with clinical annotations (Fig. 1). We aimed to capture the complete spectrum of brain tumours as encountered in day-to-day medical diagnostic practice. Importantly, we managed to specifically digitize slides of exceedingly rare pathologies, which are usually, if ever, seen only a few times in a pathologist’s lifetime. By performing a manual review of each slide, we ensure high scan quality and actuality of provided diagnoses. We envisage this dataset to be used for advancing digital pathology-based machine learning and for teaching purposes. Importantly, this dataset can be used for (1) inter-tumour comparisons thanks to the wide inclusion of distinct brain tumour types as well as (2) within-tumour-type investigations thanks to the inclusion of a large number of samples for the common tumour types.

Fig. 1.

Overview of the data acquisition and publication process. First, histological slides and clinical records of brain tumour patients were retrieved from the biobank of the Division of Neuropathology and Neurochemistry, Medical University of Vienna. Then, slides were digitized using a Hamamatsu slidescanner. Clinical data were translated into standardized annotations. At least two experienced neuropathologists checked each slide scan to ensure conformity of the diagnosis with the current revised 4th edition of the “WHO Classification of Tumours of the Central Nervous System” and sufficient scan quality. Ambiguous cases were excluded and WSIs of inferior quality were re-scanned. Finally, data were made available via EBRAINS to the international research community. (Brain illustration adapted from Meaghan Hendricks from the Noun Project).

Methods

Sample acquisition

H&E stained tumour slides from FFPE tissues, which were collected for routine diagnostics in the time interval of 1995–2019 have been obtained from the biobank of the Division of Neuropathology & Neurochemistry, Medical University of Vienna. We digitized each slide in high magnification (40x objective, 228 nm/pixel) using a Hamamatsu NanoZoomer 2.0 HT slide-scanner. Each slide was manually reviewed to ensure high scan quality and sufficient diagnostic tumour tissue. Samples with equivocal diagnoses or missing molecular work-up otherwise needed to assign an integrated WHO 2016 diagnosis were excluded. A subset of glioblastoma scans (n = 381) has been published previously as part of the GBMatch study15.

Basic clinical annotations consisting of patient age and sex as well as tumour location and recurrence were acquired from local electronic records where available. Tumour locations have been assigned to the following 19 categories: frontal; parietal; insular; occipital; temporal; cerebellar; brain stem; spinal; lateral ventricle; diencephalon; third ventricle; fourth ventricle; sellar region; cranial nerves; basal ganglia; cerebral, NOS (not otherwise specified); posterior fossa, NOS; cranial, NOS; and other.

This study complies with the relevant ethical, legal and institutional regulations and the study protocol has been approved by the Ethics Committee of the Medical University of Vienna (EK1691–2017). Participant informed consent has been obtained as by institutional guidelines, necessitating restrictions on commercial use of the obtained data.

Estimation of cell density and scanned tissue area

Additionally, the total tissue area and the average cellularities were estimated for each scan using a custom MATLAB script (MATLAB R2017b, MathWorks) with a similar approach as previously published15,16. In summary, H&E stained WSIs were first colour-deconvoluted into separate Haematoxylin and Eosin channels17. Then, global, Phansalkar and Otsu thresholding were applied to the Haematoxylin channel to identify nuclei18,19. Watershedding was used to separate densely clustered cells20. Only cells with a minimum size of 4 pixels were kept. The total tissue area was determined by averaging all colour channels, thresholding at a threshold of 220, followed by binary close and open operations.

Data Records

Data are provided via EBRAINS21 as one ndpi-file per sample, sorted by diagnostic tumour type (in alphabetical order) for easier access. It is possible to download single files directly or all files of a specific tumour type or the whole dataset using a download manager (such as the Chrono Download Manager for the Google Chrome browser). Furthermore, supplementary clinical information, estimated cell densities and scanned tissue area is provided in a csv-spreadsheet with one row per tumour sample. An overview of all spreadsheet variables and descriptions is given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Recorded clinical variables and corresponding descriptions.

| Variable | Description |

|---|---|

| uuid | unique sample identifier |

| pat_id | unique patient identifier |

| diagnosis | primary diagnosis according to the WHO Classification of Tumours of the Central Nervous System (2016) |

| grade | WHO grade according to the WHO Classification of Tumours of the Central Nervous System (2016) |

| subtype | further specification of the histopathological subtype which is not a distinct entity as defined by the WHO, if applicable |

| secondary_diagnosis | secondary diagnosis in cases where two distinct diagnosis according to the WHO are applicable |

| control | 1 if sample is a control sample without tumour tissue |

| age | patient age at the time of surgery |

| sex | biological patient sex |

| location | list (in square brackets) of all applicable tumour locations; empty if location is unknown |

| laterality | laterality of the tumour (left or right) |

| cellularity | estimated cell density of the tissue (given in 1/mm2) |

| tissue_area | estimated scanned tissue area (in mm2) |

| recurrence | 0 if the entry corresponds to a primary tumour resection; if the entry corresponds to a tumour recurrence, the number of the recurrence is given (e.g., 2 corresponds to the second recurrence) |

| comment | notable findings that do not fit in other columns (e.g., important mutations not yet integrated in the WHO classification; other non-tumour pathologies in the control samples) |

A total of 3,115 histological slides of 2,880 patients have been scanned. A total of 126 distinct diagnostic tumour types could be included. There are 1,395 female and 1,462 male patients in the dataset. The mean patient age at brain tumour surgery was 45 years, ranging from 9 days to 92 years. 2,530 of the scanned slides originated from primary operations and 538 from re-operations. See online-only Table 1 for descriptive properties broken down by tumour type. Descriptive visualizations of patient age, sex, tumour location, cellularity, and scanned tissue area are given in Fig. 2. Of note, we also scanned exceptionally rare tumour types such as melanotic schwannomas or liponeurocytomas (Fig. 3). A total of 47 non-tumour slides from different non-tumour CNS regions and with different pathologies were included as controls.

Online-only Table 1.

Overview of the frequencies and descriptive statistics of all brain tumour types included in the DBTA.

| # of scans | Median age | Age range | Cellularity | Tissue Area | F:M ratio | Most frequent location | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adamantinomatous craniopharyngioma | 85 | 30 years | 2–79 years | 5219 ± 254/mm2 | 81 ± 7 mm2 | 1.36 | sellar region |

| Anaplastic astrocytoma, IDH-mutant | 47 | 43 years | 24–65 years | 3765 ± 282/mm2 | 162 ± 17 mm2 | 0.74 | frontal |

| Anaplastic astrocytoma, IDH-wildtype | 47 | 54 years | 12–79 years | 4633 ± 361/mm2 | 85 ± 14 mm2 | 0.57 | temporal |

| Anaplastic ependymoma | 50 | 7 years | 0.3–77 years | 5571 ± 298/mm2 | 138 ± 16 mm2 | 0.92 | fourth ventricle |

| Anaplastic ganglioglioma | 5 | 36 years | 14–70 years | 3129 ± 801/mm2 | 96 ± 44 mm2 | NA | temporal |

| Anaplastic meningioma | 46 | 63 years | 30–84 years | 6291 ± 380/mm2 | 223 ± 17 mm2 | 1.19 | frontal |

| Anaplastic oligodendroglioma, IDH-mutant and 1p/19q codeleted | 91 | 49 years | 30–78 years | 4899 ± 217/mm2 | 162 ± 11 mm2 | 0.72 | frontal |

| Anaplastic pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma | 1 | 48 years | NA | 2933/mm2 | 245 mm2 | NA | cerebral, NOS |

| Angiocentric glioma | 3 | 8 years | 3–35 years | 3519/mm2 | 138 mm2 | 2 | temporal |

| Angiomatous meningioma | 32 | 60 years | 43–79 years | 4185 ± 330/mm2 | 201 ± 14 mm2 | 1.13 | frontal |

| Angiosarcoma | 2 | 66 years | 53–79 years | 2440/mm2 | 112 mm2 | NA | cerebral, NOS |

| Astroblastoma | 7 | 40 years | 12–83 years | 5417 ± 440/mm2 | 120 ± 24 mm2 | 1.33 | frontal |

| Atypical choroid plexus papilloma | 4 | 26 years | 0.3–56 years | 6555/mm2 | 98 mm2 | 1 | lateral ventricle |

| Atypical meningioma | 83 | 58 years | 13–92 years | 6901 ± 222/mm2 | 225 ± 11 mm2 | 1.13 | frontal |

| Atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumour | 17 | 3 years | 0.3–10 years | 6846 ± 791/mm2 | 61 ± 21 mm2 | 1.29 | temporal |

| CNS ganglioneuroblastoma | 1 | 0 years | NA | 7247/mm2 | 306 mm2 | NA | frontal |

| Cellular schwannoma | 25 | 54 years | 27–79 years | 7459 ± 526/mm2 | 128 ± 20 mm2 | 1.08 | spinal |

| Central neurocytoma | 20 | 28 years | 6–41 years | 8053 ± 650/mm2 | 110 ± 22 mm2 | 0.67 | lateral ventricle |

| Cerebellar liponeurocytoma | 4 | 50 years | 43–57 years | 6924/mm2 | 125 mm2 | NA | cranial nerves |

| Chondrosarcoma | 21 | 37 years | 6–73 years | 5642 ± 621/mm2 | 132 ± 28 mm2 | 1.33 | cranial, NOS |

| Chordoid glioma of the third ventricle | 4 | 34 years | 26–42 years | 5074/mm2 | 36 mm2 | 0.33 | third ventricle |

| Chordoid meningioma | 12 | 47 years | 35–73 years | 4408 ± 776/mm2 | 210 ± 17 mm2 | 3 | cranial, NOS |

| Chordoma | 28 | 61 years | 4–85 years | 2808 ± 342/mm2 | 114 ± 16 mm2 | 0.56 | cranial, NOS |

| Choriocarcinoma | 1 | 76 years | NA | 8954/mm2 | 131 mm2 | NA | sellar region |

| Choroid plexus carcinoma | 7 | 3 years | 0.5–46 years | 6778 ± 691/mm2 | 100 ± 35 mm2 | NA | cerebral, NOS |

| Choroid plexus papilloma | 21 | 29 years | 0.2–78 years | 5454 ± 467/mm2 | 156 ± 26 mm2 | 0.91 | fourth ventricle |

| Clear cell meningioma | 13 | 39 years | 8–74 years | 5027 ± 648/mm2 | 182 ± 32 mm2 | 1.17 | sellar region |

| Crystal-storing histiocytosis | 1 | 62 years | NA | 1435/mm2 | 211 mm2 | NA | NA |

| Desmoplastic infantile astrocytoma and ganglioglioma | 11 | 1 years | 0.5–23 years | 5206 ± 642/mm2 | 180 ± 37 mm2 | 1.5 | parietal |

| Diffuse astrocytoma, IDH-mutant | 70 | 37 years | 18–60 years | 3013 ± 171/mm2 | 105 ± 12 mm2 | 0.64 | frontal |

| Diffuse astrocytoma, IDH-wildtype | 19 | 58 years | 20–77 years | 2730 ± 315/mm2 | 90 ± 23 mm2 | 0.36 | frontal |

| Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the CNS | 59 | 68 years | 9–84 years | 6021 ± 450/mm2 | 90 ± 13 mm2 | 1.46 | frontal |

| Diffuse leptomeningeal glioneuronal tumour | 1 | 2 years | NA | 8070/mm2 | 8 mm2 | NA | frontal |

| Diffuse midline glioma, H3 K27M-mutant | 21 | 19 years | 3–64 years | 4258 ± 460/mm2 | 26 ± 7 mm2 | 1.1 | brain stem |

| Dysembryoplastic neuroepithelial tumour | 25 | 31 years | 8–57 years | 2410 ± 196/mm2 | 76 ± 16 mm2 | 0.79 | temporal |

| Dysplastic cerebellar gangliocytoma | 1 | 38 years | NA | 2345/mm2 | 196 mm2 | NA | cerebellar |

| EBV-positive diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, NOS | 1 | 34 years | NA | 6595/mm2 | 5 mm2 | NA | frontal |

| Embryonal carcinoma | 1 | 39 years | NA | 4888/mm2 | 291 mm2 | NA | parietal |

| Embryonal tumour with multilayered rosettes, C19MC-altered | 3 | 2 years | 2–3 years | 6087/mm2 | 231 mm2 | 2 | parietal |

| Ependymoma | 46 | 49 years | 2–78 years | 4813 ± 347/mm2 | 94 ± 12 mm2 | 0.96 | spinal |

| Ependymoma, RELA fusion-positive | 6 | 12 years | 4–55 years | 5814 ± 1401/mm2 | 138 ± 40 mm2 | 0.5 | lateral ventricle |

| Epitheloid MPNST | 1 | 50 years | NA | 3003/mm2 | 70 mm2 | NA | other |

| Erdheim-Chester disease | 1 | 57 years | NA | 2194/mm2 | 239 mm2 | NA | NA |

| Ewing sarcoma | 4 | 6 years | 0.8–28 years | 8370/mm2 | 91 mm2 | 1 | spinal |

| Extraventricular neurocytoma | 1 | 36 years | NA | 1193/mm2 | 107 mm2 | NA | spinal |

| Fibrosarcoma | 2 | 27 years | 20–34 years | 4639/mm2 | 199 mm2 | 1 | cerebral, NOS |

| Fibrous meningioma | 57 | 58 years | 12–84 years | 6103 ± 237/mm2 | 228 ± 13 mm2 | 6.12 | cranial, NOS |

| Follicular lymphoma | 3 | 62 years | 62–64 years | 8741/mm2 | 276 mm2 | 2 | occipital |

| Gangliocytoma | 1 | 36 years | NA | 1127/mm2 | 10 mm2 | NA | occipital |

| Ganglioglioma | 88 | 21 years | 2–65 years | 2932 ± 153/mm2 | 110 ± 9 mm2 | 0.6 | temporal |

| Ganglioneuroma | 2 | 33 years | 27–39 years | 4228/mm2 | 212 mm2 | 1 | other |

| Gemistocytic astrocytoma, IDH-mutant | 6 | 38 years | 29–56 years | 2036 ± 228/mm2 | 121 ± 25 mm2 | 0.5 | temporal |

| Germinoma | 20 | 16 years | 9–33 years | 7091 ± 686/mm2 | 21 ± 6 mm2 | 0.11 | diencephalon |

| Giant cell glioblastoma | 21 | 43 years | 11–86 years | 3170 ± 301/mm2 | 181 ± 20 mm2 | 0.62 | temporal |

| Glioblastoma, IDH-mutant | 34 | 38 years | 25–73 years | 4867 ± 296/mm2 | 172 ± 19 mm2 | 1 | frontal |

| Glioblastoma, IDH-wildtype | 474 | 62 years | 17–87 years | 4481 ± 96/mm2 | 151 ± 5 mm2 | 0.66 | temporal |

| Gliosarcoma | 59 | 57 years | 9–86 years | 4794 ± 276/mm2 | 221 ± 14 mm2 | 0.44 | temporal |

| Granular cell tumour of the sellar region | 1 | 46 years | NA | 2172/mm2 | 97 mm2 | NA | sellar region |

| Haemangioblastoma | 88 | 50 years | 16–81 years | 5119 ± 185/mm2 | 109 ± 10 mm2 | 1 | cerebellar |

| Haemangioma | 30 | 51 years | 0.2–76 years | 2796 ± 292/mm2 | 133 ± 15 mm2 | 2 | cranial, NOS |

| Haemangiopericytoma | 34 | 39 years | 25–83 years | 9064 ± 489/mm2 | 186 ± 18 mm2 | 0.48 | cranial, NOS |

| Hybrid nerve sheath tumours | 3 | 58 years | 32–72 years | 3342/mm2 | 227 mm2 | 0.5 | spinal |

| Immature teratoma | 7 | 15 years | 0.0–56 years | 7927 ± 913/mm2 | 107 ± 28 mm2 | 0.4 | third ventricle |

| Immunodeficiency-associated CNS lymphoma | 5 | 53 years | 31–73 years | 5209 ± 1227/mm2 | 65 ± 34 mm2 | 0.67 | cerebral, NOS |

| Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumour | 1 | 26 years | NA | 5226/mm2 | 298 mm2 | NA | frontal |

| Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma | 2 | 70 years | 62–78 years | 1242/mm2 | 427 mm2 | NA | NA |

| Juvenile xanthogranuloma | 1 | 23 years | NA | 12519/mm2 | 75 mm2 | NA | NA |

| Langerhans cell histiocytosis | 32 | 13 years | 1–53 years | 6848 ± 565/mm2 | 104 ± 19 mm2 | 0.78 | parietal |

| Leiomyoma | 1 | 50 years | NA | 1864/mm2 | 28 mm2 | NA | cranial, NOS |

| Leiomyosarcoma | 4 | 58 years | 50–77 years | 6955/mm2 | 213 mm2 | 1 | occipital |

| Lipoma | 38 | 10 years | 0.3–76 years | 757 ± 66/mm2 | 120 ± 16 mm2 | 0.9 | spinal |

| Liposarcoma | 1 | 52 years | NA | 2697/mm2 | 107 mm2 | NA | spinal |

| Low-grade B-cell lymphomas of the CNS | 13 | 67 years | 50–83 years | 8087 ± 1088/mm2 | 86 ± 25 mm2 | 1.17 | spinal |

| Lymphoplasmacyte-rich meningioma | 2 | 46 years | 37–55 years | 9817/mm2 | 37 mm2 | 1 | cranial, NOS |

| MALT lymphoma of the dura | 5 | 68 years | 39–79 years | 9843 ± 1672/mm2 | 39 ± 23 mm2 | 1.5 | cranial, NOS |

| Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumour | 15 | 61 years | 17–81 years | 5886 ± 794/mm2 | 136 ± 28 mm2 | 0.88 | spinal |

| Mature teratoma | 6 | 10 years | 0.2–49 years | 3259 ± 760/mm2 | 135 ± 45 mm2 | 0.2 | spinal |

| Medulloblastoma, SHH-activated and TP53-mutant | 3 | 16 years | 0.5–52 years | 9539/mm2 | 117 mm2 | 2 | cerebellar |

| Medulloblastoma, SHH-activated and TP53-wildtype | 9 | 30 years | 1–75 years | 10544 ± 581/mm2 | 185 ± 38 mm2 | 0.5 | cerebellar |

| Medulloblastoma, WNT-activated | 7 | 13 years | 6–65 years | 7641 ± 954/mm2 | 79 ± 20 mm2 | 0.4 | fourth ventricle |

| Medulloblastoma, non-WNT/non-SHH | 32 | 8 years | 3–34 years | 8799 ± 412/mm2 | 113 ± 13 mm2 | 0.33 | fourth ventricle |

| Melanotic schwannoma | 3 | 64 years | 51–69 years | 3110/mm2 | 55 mm2 | 0.5 | cranial nerves |

| Meningeal melanocytoma | 5 | 51 years | 35–54 years | 8152 ± 1898/mm2 | 172 ± 60 mm2 | 0.67 | spinal |

| Meningeal melanoma | 2 | 61 years | 51–71 years | 6763/mm2 | 160 mm2 | NA | spinal |

| Meningothelial meningioma | 104 | 55 years | 25–88 years | 5951 ± 212/mm2 | 162 ± 10 mm2 | 4.47 | cranial, NOS |

| Metaplastic meningioma | 4 | 75 years | 56–85 years | 4613/mm2 | 226 mm2 | NA | frontal |

| Metastatic tumours | 47 | 58 years | 38–78 years | 5092 ± 399/mm2 | 159 ± 14 mm2 | 0.88 | spinal |

| Microcystic meningioma | 23 | 48 years | 33–75 years | 4475 ± 382/mm2 | 213 ± 23 mm2 | 2.83 | frontal |

| Mixed germ cell tumour | 5 | 20 years | 12–44 years | 4379 ± 1084/mm2 | 142 ± 45 mm2 | 0.25 | spinal |

| Myxopapillary ependymoma | 23 | 35 years | 11–71 years | 3188 ± 360/mm2 | 154 ± 16 mm2 | 0.64 | spinal |

| Neurofibroma | 16 | 44 years | 0.7–65 years | 3640 ± 446/mm2 | 151 ± 29 mm2 | 0.6 | spinal |

| Olfactory neuroblastoma | 10 | 58 years | 27–69 years | 5053 ± 780/mm2 | 213 ± 34 mm2 | 0.25 | cranial, NOS |

| Oligodendroglioma, IDH-mutant and 1p/19q codeleted | 85 | 46 years | 12–73 years | 3587 ± 174/mm2 | 136 ± 12 mm2 | 0.7 | frontal |

| Osteochondroma | 1 | 14 years | NA | 2388/mm2 | 39 mm2 | NA | spinal |

| Osteoma | 9 | 48 years | 40–69 years | 1570 ± 638/mm2 | 107 ± 33 mm2 | 1.25 | frontal |

| Osteosarcoma | 8 | 30 years | 17–54 years | 4328 ± 498/mm2 | 176 ± 20 mm2 | 3 | cerebral, NOS |

| Papillary craniopharyngioma | 13 | 61 years | 44–82 years | 4941 ± 427/mm2 | 65 ± 13 mm2 | 0.86 | sellar region |

| Papillary ependymoma | 2 | 35 years | 35–35 years | 5573/mm2 | 146 mm2 | NA | spinal |

| Papillary glioneuronal tumour | 2 | 12 years | 12–13 years | 5877/mm2 | 117 mm2 | NA | cerebral, NOS |

| Papillary meningioma | 3 | 38 years | 20–61 years | 7270/mm2 | 198 mm2 | NA | temporal |

| Papillary tumour of the pineal region | 11 | 17 years | 4–48 years | 6094 ± 807/mm2 | 82 ± 28 mm2 | 1.75 | third ventricle |

| Paraganglioma | 17 | 54 years | 25–69 years | 6734 ± 468/mm2 | 165 ± 24 mm2 | 0.89 | spinal |

| Perineurioma | 1 | 23 years | NA | 3580/mm2 | 26 mm2 | NA | other |

| Pilocytic astrocytoma | 173 | 11 years | 0.6–51 years | 3327 ± 117/mm2 | 105 ± 8 mm2 | 0.66 | cerebellar |

| Pilomyxoid astrocytoma | 24 | 7 years | 0.4–56 years | 4073 ± 362/mm2 | 45 ± 11 mm2 | 1 | cranial nerves |

| Pineal parenchymal tumour of intermediate differentiation | 6 | 44 years | 9–55 years | 9287 ± 619/mm2 | 86 ± 44 mm2 | 0.2 | diencephalon |

| Pineoblastoma | 5 | 23 years | 1–67 years | 7436 ± 1352/mm2 | 87 ± 43 mm2 | 4 | third ventricle |

| Pineocytoma | 6 | 19 years | 1–40 years | 4086 ± 1245/mm2 | 60 ± 38 mm2 | 0.5 | diencephalon |

| Pituicytoma | 3 | 47 years | 27–67 years | 5231/mm2 | 33 mm2 | 2 | sellar region |

| Pituitary adenoma | 99 | 54 years | 16–80 years | 7842 ± 225/mm2 | 56 ± 6 mm2 | 0.98 | sellar region |

| Pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma | 21 | 29 years | 5–72 years | 4215 ± 368/mm2 | 145 ± 23 mm2 | 1.38 | temporal |

| Plexiform neurofibroma | 1 | 12 years | NA | 12310/mm2 | 66 mm2 | NA | NA |

| Psammomatous meningioma | 28 | 66 years | 29–83 years | 5201 ± 372/mm2 | 125 ± 15 mm2 | 8.33 | spinal |

| Rhabdoid meningioma | 5 | 63 years | 52–89 years | 5016 ± 475/mm2 | 235 ± 62 mm2 | 0.67 | occipital |

| Rhabdomyosarcoma | 3 | 51 years | 49–62 years | 2474/mm2 | 299 mm2 | 2 | cranial, NOS |

| Rosette-forming glioneuronal tumour | 11 | 25 years | 13–47 years | 3997 ± 822/mm2 | 56 ± 21 mm2 | 1.75 | cerebellar |

| Schwannoma | 81 | 53 years | 14–78 years | 5715 ± 229/mm2 | 124 ± 10 mm2 | 0.93 | cranial nerves |

| Secretory meningioma | 41 | 58 years | 40–80 years | 6112 ± 313/mm2 | 154 ± 16 mm2 | 12.67 | cranial, NOS |

| Spindle cell oncocytoma | 1 | 47 years | NA | 4958/mm2 | 13 mm2 | NA | NA |

| Subependymal giant cell astrocytoma | 14 | 15 years | 10–33 years | 3336 ± 447/mm2 | 136 ± 31 mm2 | 0.56 | lateral ventricle |

| Subependymoma | 24 | 54 years | 8–81 years | 1829 ± 151/mm2 | 125 ± 20 mm2 | 1.18 | lateral ventricle |

| T-cell and NK/T-cell lymphomas of the CNS | 1 | 54 years | NA | 7400/mm2 | 18 mm2 | NA | cerebral, NOS |

| Tanycytic ependymoma | 1 | 41 years | NA | 5440/mm2 | 232 mm2 | NA | spinal |

| Teratoma with malignant transformation | 1 | 40 years | NA | 7202/mm2 | 122 mm2 | NA | frontal |

| Transitional meningioma | 68 | 58 years | 29–82 years | 7221 ± 213/mm2 | 203 ± 13 mm2 | 2.09 | frontal |

| Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma | 1 | 62 years | NA | 5773/mm2 | 401 mm2 | NA | cranial, NOS |

Cellularity and Tissue area are given as [mean ± SEM].

Fig. 2.

Descriptive statistics of the ‘Digital Brain Tumour Atlas’ patient cohort (not including control patients). (a) The age distribution by sex shows a bimodal distribution with most patients belonging to the higher-age categories. Since some uncommon tumour types like medulloblastoma occur mainly in children and have been strategically over-sampled, there is also a peak in younger patients. (b) The distribution of the different WHO grades shows a slight predominance of grade I and grade IV tumours. Of note, some tumour entities are not assigned WHO grades (‘NA’) and very few tumour types are assigned intermediate grades II-III (a total of five cases, not shown in the figure). (c) Tumour distribution with colour-coded locations and ratio-specific circle sizes. (Brain illustration adapted from Patrick J. Lynch, wikimedia) (d) Distribution of the cell densities of all included tumour samples by tumour grade. Note that lower-grade tumours are not necessarily less cell dense (e.g., in the case of cellular schwannoma). (e) The distribution of the scanned tissue areas (per slide).

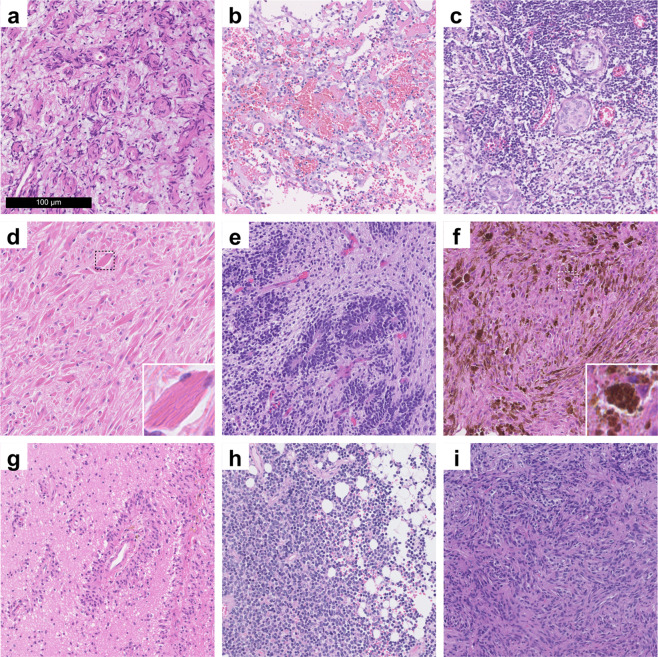

Fig. 3.

Exemplary images from exceedingly rare brain tumours, which are included in the DBTA. (a) Perineurioma component of a hybrid nerve sheath tumour. (b) Angiosarcoma. (c) Lymphoplasmacyte-rich meningioma. (d) Crystal-storing histiocytosis. (e) Embryonal tumour with multilayered rosettes. (f) Melanotic schwannoma. (g) Angiocentric glioma. (h) Cerebellar liponeurocytoma. (i) Pituicytoma.

Technical Validation

All cases were initially selected based on the given diagnosis in the diagnostic electronic records. To ensure conformity with the WHO 2016 diagnosis, all slides have been independently reviewed by two neuropathologists experienced in neuro-oncology. In disputed cases, a third senior neuropathologist was consulted. Older cases with missing necessary molecular analyses were not included in the dataset.

Inter- and intraobserver variability is one factor that contributes to misdiagnoses or discrepant diagnoses. We mitigated the risk by including only cases that had already undergone thorough routine diagnostic work-up and were additionally reviewed independently by at least two neuropathologists as described above. In this way, we also ensured excellent image quality and the presence of sufficient diagnostic tumour tissue on each WSI. Scans with suboptimal image quality were either re-scanned (if possible) or excluded.

Usage Notes

Data access

The data can be accessed via EBRAINS21. In order to download the data set, users have to register with EBRAINS and agree to the general terms of use, access policy as well as the data use agreement for pseudonymised human data (https://ebrains.eu/terms). The data are distributed under the conditions that users cite the respective DOI, adhere to EBRAINS’ Data Use Agreement and do not use the data for commercial purposes.

WSI processing

The ndp.view2 (© Hamamatsu) software can be freely used to view and annotate slide scans saved in the ndpi format22. Alternatively, most other WSI programs such as the open-source OMERO software platform23 and the open-source QuPath software24 can work directly on ndpi-files. However, most programming languages and non-specialized image processing software cannot handle ndpi-files out of the box. Thus, we also provide a toolbox of MATLAB scripts that depend on the openslide library25 and can be used to

Automatically tile large slide scans and export multiple smaller image patches in a given magnification.

Convert annotation-files (.ndpa) to overlays, which can be used to extract specific regions of interest.

Estimate the total tissue area on a WSI.

Estimate the cell density on a WSI.

Of note, slide thickness and staining intensity vary to some degree, resulting in a slightly different histological appearance of each slide. Thus, for machine learning applications, we recommend astain normalization step such as WSICS26, more recent methods employing generative adversarial networks27 or style transfer learning28. Moreover, heavy stain colour augmentation should be performed29. Of note, the stain normalization step can be omitted with only a negligible drop in performance as has been shown by Tellez et al.29.

Acknowledgements

T.R. is a recipient of a DOC Fellowship (25262) of the Austrian Academy of Sciences at the Division of Neuropathology and Neurochemistry, Department of Neurology, Medical University of Vienna. The present work has been further supported by the Austrian Science Fund 1000 ideas project TAI98-B to A.W.

Online-only Table

Author contributions

T.R. and A.W. conceived and designed the project. T.R., A.C.M., C.C.V., P.M., B.A. and R.P. collected the data. T.R., E.G., R.H., C.H., J.A.H. and A.W. reviewed the data. T.R., B.B. and G.L. performed the image analysis. T.R. and A.W. wrote the paper with contributions from all authors.

Code availability

The custom-made MATLAB toolbox for loading, viewing and processing of ndpi & ndpa files and for estimating the total tissue area and average cell density of a WSI can be accessed at: https://github.com/tovaroe/WSI_histology.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Rouse C, Gittleman H, Ostrom QT, Kruchko C, Barnholtz-Sloan JS. Years of potential life lost for brain and CNS tumors relative to other cancers in adults in the United States, 2010. Neuro. Oncol. 2015;18:70–77. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nov249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu R, Page M, Solheim K, Fox S, Chang SM. Quality of life in adults with brain tumors: Current knowledge and future directions. Neuro. Oncol. 2009;11:330–339. doi: 10.1215/15228517-2008-093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ostrom QT, et al. CBTRUS Statistical Report: Primary Brain and Other Central Nervous System Tumors Diagnosed in the United States in 2013–2017. Neuro. Oncol. 2020;22:iv1–iv96. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noaa200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.International Agency for Research on Cancer & Wiestler, O. D. WHO Classification of Tumours of the Central Nervous System. (International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2016).

- 5.van den Bent MJ, et al. A clinical perspective on the 2016 WHO brain tumor classification and routine molecular diagnostics. Neuro. Oncol. 2017;19:614–624. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/now277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Capper D, et al. DNA methylation-based classification of central nervous system tumours. Nature. 2018;555:469–474. doi: 10.1038/nature26000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Djuric U, Zadeh G, Aldape K, Diamandis P. Precision histology: how deep learning is poised to revitalize histomorphology for personalized cancer care. npj Precision Oncology. 2017;1:1–5. doi: 10.1038/s41698-017-0022-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.The Cancer Genome Atlas Program. https://www.cancer.gov/about-nci/organization/ccg/research/structural-genomics/tcga (2018).

- 9.Puchalski RB, et al. An anatomic transcriptional atlas of human glioblastoma. Science. 2018;360:660–663. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf2666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ivy Glioblastoma Atlas Project. https://glioblastoma.alleninstitute.org/ (2018).

- 11.National Cancer Institute Clinical Proteomic Tumor Analysis Consortium (CPTAC). Radiology Data from the Clinical Proteomic Tumor Analysis Consortium Glioblastoma Multiforme [CPTAC-GBM] collection. 10.7937/K9/TCIA.2018.3RJE41Q1 (2018).

- 12.Mobadersany P, et al. Predicting cancer outcomes from histology and genomics using convolutional networks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2018;115:E2970–E2979. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1717139115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spatial Organization and Molecular Correlation of Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes Using Deep Learning on Pathology Images. Cell Rep. 23, 181–193.e7 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Li X, Tang Q, Yu J, Wang Y, Shi Z. Microvascularity detection and quantification in glioma: a novel deep-learning-based framework. Lab. Invest. 2019;99:1515–1526. doi: 10.1038/s41374-019-0272-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klughammer J, et al. The DNA methylation landscape of glioblastoma disease progression shows extensive heterogeneity in time and space. Nat. Med. 2018;24:1611–1624. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0156-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roetzer T, et al. Evaluating cellularity and structural connectivity on whole brain slides using a custom-made digital pathology pipeline. J. Neurosci. Methods. 2019;311:215–221. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2018.10.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ruifrok AC, Johnston DA. Quantification of histochemical staining by color deconvolution. Anal. Quant. Cytol. Histol. 2001;23:291–299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.A Threshold Selection Method from Gray-Level Histograms. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/4310076.

- 19.Adaptive local thresholding for detection of nuclei in diversity stained cytology images. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/5739305.

- 20.Topographic distance and watershed lines. Signal Processing38, 113–125 (1994).

- 21.Roetzer-Pejrimovsky T, 2021. The Digital Brain Tumour Atlas, an open histopathology resource. EBRAINS. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.U12388-01. https://www.hamamatsu.com/us/en/product/type/U12388-01/index.html.

- 23.Allan C, et al. OMERO: flexible, model-driven data management for experimental biology. Nat. Methods. 2012;9:245–253. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bankhead P, et al. QuPath: Open source software for digital pathology image analysis. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:1–7. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-17204-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goode A, Gilbert B, Harkes J, Jukic D, Satyanarayanan M. OpenSlide: A vendor-neutral software foundation for digital pathology. J. Pathol. Inform. 2013;4:27. doi: 10.4103/2153-3539.119005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stain Specific Standardization of Whole-Slide Histopathological Images. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/7243333. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Zanjani, F. G., Zinger, S., Bejnordi, B. E., van der Laak, J. A. W. M. & de With, P. H. N. Stain normalization of histopathology images using generative adversarial networks. 2018 IEEE 15th International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI 2018)10.1109/isbi.2018.8363641 (2018).

- 28.Bug, D. et al. Context-Based Normalization of Histological Stains Using Deep Convolutional Features. in Deep Learning in Medical Image Analysis and Multimodal Learning for Clinical Decision Support 135–142 (Springer, Cham, 2017).

- 29.Quantifying the effects of data augmentation and stain color normalization in convolutional neural networks for computational pathology. Med. Image Anal. 58, 101544 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Roetzer-Pejrimovsky T, 2021. The Digital Brain Tumour Atlas, an open histopathology resource. EBRAINS. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Data Availability Statement

The custom-made MATLAB toolbox for loading, viewing and processing of ndpi & ndpa files and for estimating the total tissue area and average cell density of a WSI can be accessed at: https://github.com/tovaroe/WSI_histology.