Abstract

Objectives

Examining the social risks that influence the health of patients accessing emergency care can inform future efforts to improve health outcomes. The optimal modality for screening in the emergency department (ED) has not yet been identified. We conducted a mixed methods evaluation of the impact of screening modality on patient satisfaction with the screening process.

Methods

Patients were enrolled at a large urban academic ED and randomized to verbal versus electronic modalities following informed consent. Participants completed a short demographic survey, a brief validated health literacy test, and a social need and risk screening tool. Participants were purposively sampled to complete qualitative interviews balanced across 4 groups defined by health literacy scores (high vs limited) and screening modality. Quantitative outcomes included screening results and satisfaction with the screening process; qualitative questions focused on experience with the screening process, barriers, and facilitators to screening.

Results

Of 554 patients assessed, 236 were randomized (115 verbal, 121 electronic). Participants were 23% Hispanic, 6% non‐Hispanic Black, 58% non‐Hispanic White, 38% publicly insured, and 57% privately insured. Two‐thirds (67%) identified social needs and risks and the majority (81%) reported satisfaction with the screening. Screening modality was not associated with satisfaction with screening process after adjustment for language, health literacy, and social risk (adjusted odds ratio, 0.74; 95% confidence interval, 0.32, 1.71).

Conclusion

Screening modality was not associated with overall satisfaction with screening process. Future strategies can consider the advantage of multimodal screening options, including the use of electronic tools to streamline screening and expand scalability and sustainability.

Keywords: health‐related social risks, multimodal screening strategy, patient satisfaction, screening modalities

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1. Background and significance

Social determinants of health (SDoH) have been defined as “conditions in which people are born, grow, work, live, and age, and the wider set of forces and systems shaping the conditions of daily life. 1 SDoH can shape heath for better or worse and determine access to these resources and to exposures that contribute to health inequities across individuals and communities. 2 Adverse social determinants of health (aSDoH), such as poverty and housing insecurity, can be categorized as social risk, when measured by screening items, or social need, when measured by individual preferences, priorities and requests. 3 Recognizing the impact of SDoH on health services utilization, treatment adherence, and health outcomes, US health care reform has placed a growing emphasis on understanding them as drivers of health disparities in the last decade. 4 , 5

The emergency department (ED) is an ideal setting for examining the impact of SDoH on health outcomes and health service utilization. 6 , 7 , 8 Because ED patients are vastly diverse with regard to socioeconomic demographics and are likely to have higher rates of health‐related social needs, EDs are particularly well‐positioned to study and address social underpinnings of health inequities. Research has shown that reasons for using the ED as a primary access point for health care, even when insured, include challenges related to low socioeconomic status (eg, transportation, work release, and childcare for multiple visits), greater ability of EDs to meet patient time constraints (eg, single visit or “one‐stop shop” service, 365/24/7 availability), and barriers to primary care (eg, difficulty keeping appointments, problems with after‐hours coverage, scarcity of urgent appointments). 9 , 10 Additionally, the presence of unmet social needs has been identified as a risk factor for high ED use 11 , 12 , 13 and yet often these remain unidentified and unaddressed in the ED. 14

The majority of research to date on screening strategies for identifying aSDoH has been conducted in primary care settings. 15 , 16 , 17 The optimal strategy for aSDoH screening in the ED is not yet known, as some studies have shown that electronic strategies may be superior, 18 , 19 but concerns remain about whether disparities in health and digital literacy may limit the applicability of that strategy within the ED.

1.2. Goals of this investigation

The purpose of this study was to compare verbal and electronic strategies for screening for aSDoH. Because there are no “gold‐standard” outcomes for ED screening, we chose to complete a mixed‐methods pilot study to use both quantitative (patient satisfaction, as a marker of willingness to engage in screening) and qualitative (in‐depth interviews) to assess screening modalities and barriers to screening.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study design, setting, and participant recruitment

Using both quantitative and qualitative methods, the current study design combines a prospective randomized controlled trial with a modified grounded theory approach to exploratory qualitative investigation. 20 , 21 , 22 The study was conducted in the ED of a large urban academic medical center with >110,000 annual visits from May through August 2019. ED patients (or parents/legal guardians of pediatric‐age patients) were eligible for study inclusion if they were English‐ or Spanish‐speaking, ≥18 years old, and able to consent. Exclusion criteria included: (1) patients unwilling to have an audio‐recorded interview, (2) medically and psychiatrically unstable patients, and (3) emotionally distressed patients such as those presenting for sexual assault. Patients who declined to be audio‐recorded were excluded to ensure that all participants enrolled in the trial were equally eligible for purposive sampling for the qualitative portion of the study.

2.2. Screening tool

Because this was a pilot study of screening within the health system, we chose to use the tool that was being implemented elsewhere in the system. The tool was developed for the primary care setting by the health system in which the study was conducted (available in English and Spanish). This screening tool was designed to identify SDoH related to 9 major categories: transportation, food, housing, ability to pay utility bills, ability to pay for medications, employment, education, childcare, and elder care.

2.3. Intervention protocol

Participants were approached in person and enrolled by a bilingual research assistant during shifts that were distributed across time of day and day of week during times when a research assistant was available. Research assistants introduced their roles in the ED to patients and reviewed the purpose of the study. Patients were assured that study participation was entirely voluntary and would have no bearing on their care. To reduce the barriers to participation, the research assistant completed a verbal consent process with each participant followed by a brief demographic questionnaire and an assessment of health literacy (Newest Vital Sign [NVS]). 23 Enrollment and interviews were conducted either in a private room or private area (hallway space) within the ED. Through use of a pre‐generated random allocation list, participants were then randomized in a 1:1 ratio to 1 of 2 arms: (1) in‐person or verbal delivery of the social need and risk screening tool, or (2) iPad self‐completion of an electronic version of the tool.

Following completion of the screener, participants completed a brief verbal post‐screening questionnaire to gauge satisfaction with the process, the presence of additional social needs and risks not captured by the screener, and perspectives on social needs and risk screening in the ED. A subset of participants purposively sampled to balance recruitment across 4 groups defined by health literacy scores (adequate vs limited) and screening strategy (verbal vs electronic) was invited to participate in an additional qualitative interview.

Interview questions were pilot tested and then interviews were conducted by GC, a female master level (MPH) clinical research coordinator, and 2 additional research assistants trained in qualitative methods and supervised by the study team. Interviews lasted approximately 5–10 minutes. Participants completing this additional interview received a $20 gift card to a convenience drugstore chain as compensation for their time. Interviews were audio‐recorded and professionally transcribed. No field notes were taken, no repeat interviews were necessary, no interview transcripts were returned for participant review, and participants were not asked to provide feedback on findings. This study was reviewed and approved by the local institutional review board (protocol 2019P000128) and exempted from further review. The study was registered prior to initiation of enrollment (NCT03834441).

2.4. Outcome measures

The primary quantitative outcome was satisfaction with screening process (“Please tell us how satisfied you were with the questionnaire you just took”) as measured by a 5‐point Likert‐type scale (5 = Extremely, 4 = Quite a bit, 3 = Somewhat, 2 = A little bit, 1 = Not at all) subsequently grouped into a binary measure of “extremely or quite a bit” versus “somewhat/a little bit/not at all” satisfied.

The qualitative outcomes were obtained through a semi‐structured exploratory interview guide comprised of open‐ended questions. The interview guide was developed to allow the participant and research assistant the flexibility to explore new themes in the course of the interview. Domains examined included screening preferences and attitudes, comfort with screening modality, appropriateness of screening in the ED, facilitators and barriers to disclosure, and missed social needs and risks (see interview guide in the Supporting Information Appendix S1).

The Bottom Line.

In a randomized trial of 236 patients, electronic and verbal screening modalities for social risks that influence the health of patients presenting to the emergency department (ED) were evaluated. The majority (81%) of patients reported satisfaction with the screening process, with no preference toward the delivery method of screening. Two‐thirds (67%) of patients identified social needs and risks, highlighting the opportunity for screening for social determinants with multimodal approaches in the ED.

2.5. Data analysis

Because of the mixed‐methods and exploratory nature of this pilot study, we aimed to enroll 200 patients in the trial portion, and used purposive sampling to determine the qualitative sampling size. Qualitative interviews are continued until thematic saturation is reached; there is not a pre‐determined sample size. Data were collected in the secure online REDCap system and analyzed using SAS (Cary, NC). Patients with missing data on the primary outcome or covariates of interest were excluded. We used standard descriptive statistics to compare rates of satisfaction with screening process between verbal and electronic survey groups. Randomized trials are not always free of confounding or selection bias. 24 Given the anticipated small sample size in this single‐center trial, and the importance of language and literacy in relation to satisfaction with the screening modality, we adjusted for health literacy and language, which were chosen a priori as the primary covariates of interest. No interaction terms were considered. We used multivariable logistic regression to estimate odds ratios and confidence intervals for high satisfaction with screening process adjusting for language, health literacy, and presence of an aSDoH.

Following review of a subset of interview transcripts, dominant emergent themes were identified using a modified grounded theory approach. 25 A code book was developed over several iterations using a hybrid approach 26 to ensure the inductive identification of codes and a deductive development of an organizing framework. All interview transcripts were manually coded independently by 2 research team members (MSK and GC, English transcripts). Spanish transcripts (n = 3) were coded by the 2 members of the research team with fluency (GC and WMK). Discrepancies in coding were resolved through collaborative review and consensus.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Characteristics of study population

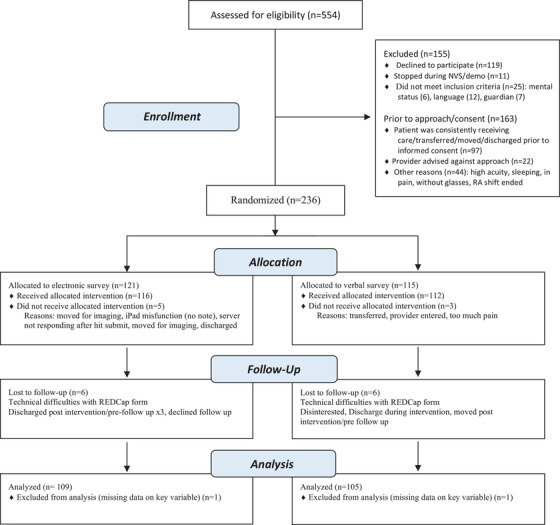

Of a total of 554 patients assessed for eligibility, 236 (42.6%) were randomized and 318 (57.4%) were excluded. Of the excluded patients, 163 (51%) were excluded before approach or consent, primarily because of care needs or the patient being discharged before being able to be consented (n = 97). Figure 1 provides the full study flow diagram and reasons for exclusion for all participants. Of those excluded after approach by a research assistant, the majority (n = 119) were excluded due to declining to participate in the study. Of the 236 randomized, 115 were randomized to the verbal modality and 121 to the electronic modality arm. Data from 105 of 115 participants randomized to the verbal group were included in the analysis and 109 of 121 assigned to the electronic group, with losses due to lost to follow‐up and missing data.

FIGURE 1.

CONSORT flow diagram

Participant mean age was 40 (15) years old, 136 (57%) were female (of which 72 [63%] were randomized to verbal and 64 [53%] to electronic screening), 53 (22%) were Hispanic, 14 (6%) were non‐Hispanic Black, and 137 (58%) were non‐Hispanic White. Only 17 (7%) were primarily Spanish‐speaking of which 9 (8%) completed the verbal and 8 (7%) completed the electronic screening. More than half of participants had private insurance (n = 134, 57%) whereas 38% had state/public insurance (n = 89) and 3% (n = 7) were uninsured/self‐pay. A majority of participants had at least some college education (n = 183, 77%), whereas 22% (n = 50) had a high school or lower level of education. Regarding proficiency with health information, 60% (n = 141) had adequate literacy (NVS score, 4–6), whereas 37% (n = 88) had limited literacy (NVS, score 0–3). Literacy levels were comparable across the screening modalities. Table 1 provides a comprehensive description of study participants.

TABLE 1.

Study participant characteristics

| Variable | Verbal, n (%) or mean (SD), (N = 115) | Electronic, n (%) or mean (SD), (N = 121) | All, n (%) or mean (SD), (N = 236) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Respondent | |||

| Patient | 66 (57) | 85 (70) | 151 (64) |

| Parent/Guardian | 46 (40) | 36 (30) | 82 (35) |

| Missing | 3 (3) | 0 (0) | 3 (1) |

| Age | |||

| Mean age, y | 41 (15) | 39 (15) | 40 (15) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Any Hispanic | 25 (22) | 28 (23) | 53 (22) |

| White non‐Hispanic | 65 (57) | 72 (60) | 137 (58) |

| Black non‐Hispanic | 9 (8) | 5 (4) | 14 (6) |

| Other non‐Hispanic | 14 (12) | 16 (13) | 30 (13) |

| Missing/declined to answer | 2 (1) | – | 2 (1) |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 42 (36) | 55 (45) | 97 (41) |

| Female | 72 (63) | 64 (53) | 136 (57) |

| Other | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Missing | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 2 (1) |

| Education | |||

| <12 y | 8 (7) | 7 (6) | 15 (7) |

| Completed high school | 18 (15) | 17 (14) | 35 (15) |

| Some college | 32 (28) | 35 (29) | 67 (28) |

| Completed college | 33 (29) | 40 (33) | 73 (31) |

| Graduate degree | 22 (19) | 21 (17) | 43 (18) |

| Missing/decline to answer | 2 (2) | 1 (1) | 3 (1) |

| Health insurance | |||

| State or public | 43 (37) | 46 (38) | 89 (38) |

| Self‐pay or uninsured | 4 (3) | 3 (2) | 7 (3) |

| Private | 64 (56) | 70 (58) | 134 (57) |

| Not sure/decline to answer | 2 (2) | 1 (1) | 3 (1) |

| Missing | 2 (2) | 1 (1) | 3 (1) |

| Health literacy (NVS score) | |||

| Adequate (scores 4–6) | 69 (60) | 72 (60) | 141 (60) |

| Limited (scores 0–3) | 42 (37) | 46 (38) | 88 (37) |

| Missing | 4 (3) | 3 (2) | 7 (3) |

| Survey language | |||

| English | 106 (92) | 113 (93) | 219 (93) |

| Spanish | 9 (8) | 8 (7) | 17 (7) |

Abbreviation: NVS, newest vital sign.

Two‐thirds of all participants (n = 158, 67%) had an identified aSDoH. Food (n = 56, 24%) and housing (n = 44, 18%) were the 2 most common social needs or risks identified using the established screening tool. Of the other domains screened, transportation needs (13.2%), employment assistance (12.3%), and assistance with bills (medication needs 12.5%, utility needs 11.3%) were also identified though to a lesser extent. A breakdown of the social needs and risks identified by screening modality, health literacy, and primary language spoken is available in Tables 2 and 3.

TABLE 2.

Adverse social determinants of health and satisfaction by screening modality

| aSDoH domain | Screening question | Response | Verbal, n (%), (N = 115) | Electronic, n (%), (N = 121) | All, n (%), (N = 236) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transportation | Has lack of transportation kept you from medical appointments or from getting medications? | Yes | 15 (13) | 15 (12) | 30 (13) |

| No | 97 (84) | 101 (84) | 198 (84) | ||

| Missing | 3 (3) | 5 (4) | 8 (3) | ||

| Food | FQ1: Within the past 12 months we worried whether our food would run out before we got money to buy more. | Never true | 92 (80) | 84 (69) | 176 (75) |

| Sometimes/often true | 19 (17) | 32 (27) | 51 (21) | ||

| Missing | 4 (3) | 5 (4) | 9 (4) | ||

| FQ2: Within the past 12 months the food we bought just didn't last and we didn't have money to get more. | Never true | 94 (82) | 93 (77) | 187 (79) | |

| Sometimes/often true | 16 (14) | 23 (19) | 39 (17) | ||

| Missing | 5 (4) | 5 (4) | 10 (4) | ||

| Food insecurity overall | Yes | 22 (19) | 34 (28) | 56 (24) | |

| No | 88 (77) | 82 (68) | 170 (72) | ||

| Missing | 5 (4) | 5 (5) | 10 (4) | ||

| Housing | HQ1: What is your housing situation today? | I do not have housing | 6 (5) | 6 (5) | 12 (5) |

| I have housing | 105 (91) | 104 (86) | 209 (89) | ||

| Missing/decline to answer | 4 (4) | 11 (9) | 15 (6) | ||

| HQ2: How many times have you moved in the past 12 months? | 2+ times | 11 (9) | 11 (9) | 22 (9) | |

| 0–1 time | 101 (88) | 103 (85) | 204 (86) | ||

| Missing/decline to answer | 3(3) | 7(6) | 10 (4) | ||

| HQ3: Are you worried that in the next 2 months, you may not have your own housing to live in? | Yes | 14 (12) | 15 (12) | 29 (12) | |

| No | 98 (85) | 99 (82) | 197 (84) | ||

| Missing/decline to answer | 3(3) | 7 (6) | 10 (4) | ||

| Housing insecurity overall | Yes | 25 (22) | 19 (16) | 44 (18) | |

| No | 87 (76) | 92 (76) | 179 (76) | ||

| Missing | 3 (2) | 10 (8) | 13 (6) | ||

| Utility bills | Do you have trouble paying your heating or electricity bill? | Yes | 10 (9) | 15 (12) | 25 (11) |

| No | 101 (88) | 97 (80) | 198 (84) | ||

| Missing/decline to answer | 4 (3) | 9 (7) | 13 (6) | ||

| Medications | Do you have trouble paying for medicines? | Yes | 13 (11) | 15 (12) | 28 (12) |

| No | 99 (86) | 97 (80) | 196 (83) | ||

| Missing/decline to answer | 3 (3) | 9 (7) | 12 (5) | ||

| Employment | Are you currently unemployed and looking for work? | Yes | 14 (12) | 14 (12) | 28 (12) |

| No | 98 (85) | 101 (83) | 199 (84) | ||

| Missing/decline to answer | 3 (3) | 6 (5) | 9 (4) | ||

| Education | Are you interested in more education? | Yes | 61 (53) | 61 (50) | 122 (52) |

| No | 51 (44) | 53 (44) | 104 (44) | ||

| Missing/decline to answer | 3 (3) | 7(6) | 10 (4) | ||

| Child and dependent elder care | Do you have trouble with childcare or the care of a family member? | Yes | 12 (10) | 7 (6) | 19 (8) |

| No | 100 (87) | 107 (88) | 207 (88) | ||

| Missing/decline to answer | 3 (3) | 7 (6) | 10 (4) | ||

| Would you like information today about any of the following topics? | None | 70 (61) | 93 (77) | 163 (69) | |

| At least 1 | 45 (39) | 28 (23) | 73 (31) | ||

| Transportation | 13 (11) | 7 (6) | 20 (8) | ||

| Paying utility bills | 15 (13) | 5 (4) | 20 (8) | ||

| Education | 21 (18) | 7 (6) | 28 (12) | ||

| Food | 16 (14) | 10 (8) | 26 (11) | ||

| Paying for medications | 13 (11) | 6 (5) | 19 (8) | ||

| Childcare | 9 (8) | 4 (3) | 13 (6) | ||

| Housing | 16 (14) | 10 (8) | 26 (11) | ||

| Job search or training | 14 (88) | 5 (4) | 19 (8) | ||

| Care for elder or disabled | 12 (10) | 1 (1) | 13 (6) | ||

| In the last 12 months, have you received assistance from an organization or program to help you with any of the following? | None | 80 (70) | 94 (78) | 174 (69) | |

| At least 1 | 35 (30) | 27 (22) | 62 (31) | ||

| Transportation | 3 (3) | 4 (3) | 7 (3) | ||

| Paying utility bills | 9 (8) | 4 (3) | 13 (6) | ||

| Education | 2 (2) | 4 (3) | 6 (3) | ||

| Food | 16 (14) | 9 (7) | 25 (11) | ||

| Paying for medications | 8 (7) | 1 (1) | 9 (4) | ||

| Childcare | 3 (3) | 1 (1) | 4 (2) | ||

| Housing | 7 (6) | 2 (2) | 9 (4) | ||

| Job search or training | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | 4 (2) | ||

| Care for elder or disabled | 7 (6) | 2 (2) | 9 (4) | ||

| (Post‐screener questionnaire) | How satisfied were you with the questionnaire? | Extremely/quite a bit | 94 (82) | 97 (80) | 191 (81) |

| Somewhat/a little/not at all | 12 (10) | 15 (12) | 27 (11) | ||

| Missing | 9 (8) | 9 (7) | 18 (8) |

Abbreviation: aSDoH, adverse social determinants of health.

Note: Columns 1, 2, and 3 describe the domain, specific question, and response, respectively; columns 4 and 5 display the comparison by screening modality while column 6 displays the aggregate data. All questions except those marked (post‐screener questionnaire) were asked as part of the initial aSDOH assessment.

TABLE 3.

Adverse social determinants of health by health literacy and primary language spoken

| aSDoH Domain | Screening question and response | Adequate HL, n (%) | Limited HL, n (%) | English, n (%) | Spanish, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transportation | Has the lack of transportation kept you from medical appointments or from getting medications? | ||||

| Yes | 17 (19) | 13 (9) | 25 (11) | 5 (29) | |

| No | 70 (80) | 126 (89) | 189 (86) | 9 (53) | |

| Missing | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | 5 (3) | 3 (18) | |

| Food | FQ1: Within the past 12 months we worried whether our food would run out before we got money to buy more. | ||||

| Sometimes/often true | 30 (34) | 21 (15) | 44 (20) | 7 (41) | |

| Never true | 57 (65) | 117 (83) | 169 (77) | 7 (41) | |

| Missing | 1 (1) | 3 (2) | 6 (3) | 3 (18) | |

| FQ2: Within the past 12 months the food we bought just didn't last and we didn't have money to get more. | |||||

| Sometimes true/often true | 26 (30) | 13 (9) | 34 (16) | 5 (29) | |

| Never true | 60 (68) | 125 (89) | 178 (81) | 9 (53) | |

| Missing | 2 (2) | 3 (2) | 7 (3) | 3 (18) | |

| Food insecurity overall: | |||||

| If answered “Sometimes true” or “Often true” to at least 1 of the 2 food security questions: | |||||

| Yes | 35 (40) | 21 (15) | 48 (22) | 8 (47) | |

| No | 51 (58) | 117 (83) | 164 (75) | 6 (35) | |

| No answer/missing | 2 (2) | 3 (2) | 7 (3) | 3 (18) | |

| Housing | HQ1: What is your housing situation today? | ||||

| I do not have housing | 8 (9) | 4 (3) | 12 (5) | 0 (0) | |

| I have housing | 74 (84) | 133 (95) | 196 (90) | 13 (76) | |

| No answer/missing | 6 (7) | 4 (2) | 11 (5) | 4 (24) | |

| HQ2: How many times have you moved in the past 12 months? | |||||

| 2 or more times | 11 (12) | 11 (8) | 20 (9) | 2 (12) | |

| 0–1 time | 75 (84) | 127 (90) | 192 (88) | 12 (70) | |

| No answer/missing | 2 (4) | 3 (2) | 7 (3) | 3 (18) | |

| HQ3: Are you worried that in the next 2 months, you may not have your own housing to live in? | |||||

| Yes | 17 (19) | 12 (9) | 21 (9) | 8 (47) | |

| No | 68 (77) | 127 (90) | 192 (88) | 5 (29) | |

| No answer/missing | 3 (4) | 2 (1) | 6 (3) | 4 (24) | |

| Housing insecurity overall: | |||||

| If answered “I do not have housing” (HQ1) or “2 or more times” (HQ2) or “Yes” (HQ3): | |||||

| Yes | 25 (28) | 19 (13) | 35 (16) | 9 (54) | |

| No | 59 (67) | 118 (84) | 175 (80) | 4 (23) | |

| No answer/missing | 4 (5) | 4 (3) | 9 (4) | 4 (23) | |

| Utility bills | Do you have trouble paying your heating or electricity bill? | ||||

| Yes | 18 (21) | 7 (5) | 20 (9) | 5 (29) | |

| No | 67 (76) | 129 (91) | 190 (87) | 8 (47) | |

| No answer/missing | 3 (3) | 5 (4) | 9 (4) | 4 (24) | |

| Medications | Do you have trouble paying for medicines? | ||||

| Yes | 16 (18) | 12 (9) | 25 (12) | 3 (18) | |

| No | 68 (77) | 126 (89) | 187 (85) | 9 (53) | |

| No answer/missing | 4 (5) | 3 (2) | 7 (3) | 5 (29) | |

| Employment | Are you currently unemployed and looking for work? | ||||

| Yes | 16 (18) | 12 (9) | 24 (11) | 4 (23) | |

| No | 70 (80) | 127 (90) | 189 (86) | 10 (59) | |

| No answer/missing | 2 (2) | 2 (1) | 6 (3) | 3 (18) | |

| Education | Are you interested in more education? | ||||

| Yes | 54 (61) | 68 (48) | 110 (50) | 12 (75) | |

| No | 31 (35) | 71 (50) | 102 (47) | 4 (25) | |

| No answer/missing | 3 (4) | 2 (2) | 7 (3) | 0 (0) | |

| Child and dependent elder care | Do you have trouble with childcare or the care of a family member? | ||||

| Yes | 12 (14) | 7 (5) | 16 (7) | 3 (18) | |

| No | 75 (85) | 130 (92) | 196 (90) | 11 (64) | |

| No answer/missing | 5 (1) | 4 (3) | 7 (3) | 3 (18) | |

| Would you like information today about any of the following topics? | |||||

| Overall (any of the below) | 41 (47) | 26 (18) | 58 (26) | 15 (88) | |

| None (none of the below) | 47 (53) | 115 (82) | 161 (74) | 2 (12) | |

| Transportation | 13 (15) | 7 (5) | 16 (7) | 4 (24) | |

| Paying utility bills | 14 (16) | 6 (4) | 13 (6) | 7 (41) | |

| Education | 17 (19) | 11 (8) | 19 (9) | 9 (53) | |

| Food | 15 (17) | 11 (8) | 20 (9) | 6 (35) | |

| Paying for medications | 12 (14) | 7 (5) | 14 (6) | 5 (29) | |

| Childcare | 9 (10) | 4 (3) | 9 (4) | 4 (24) | |

| Housing | 15 (17) | 11 (8) | 22 (10) | 4 (24) | |

| Job search or training | 13 (13) | 6 (4) | 13 (6) | 6 (35) | |

| Care for elder or disabled | 7 (8) | 5 (4) | 9 (4) | 4 (24) | |

| In the last 12 months, have you received assistance from an organization or program to help you with any of the following: | |||||

| Overall (any of the below) | 30 (34) | 27 (19) | 52 (24) | 10 (59) | |

| None (none of the below) | 58 (66) | 114 (81) | 167 (76) | 7 (41) | |

| Transportation | 6 (7) | 1 (1) | 7 (3) | 0 (0) | |

| Paying utility bills | 7 (8) | 6 (4) | 11 (5) | 0 (0) | |

| Education | 3 (3) | 3 (2) | 6 (3) | 0 (0) | |

| Food | 13 (15) | 12 (9) | 23 (11) | 2 (12) | |

| Paying for medications | 3 (3) | 6 (4) | 7 (3) | 2 (12) | |

| Childcare | 2 (2) | 2 (1) | 4 (2) | 0 (0) | |

| Housing | 5 (6) | 4 (3) | 8 (4) | 1 (6) | |

| Job search or training | 4 (5) | 0 (0) | 4 (2) | 0 (0) | |

| Care for elder or disabled | 6 (7) | 3 (2) | 9 (4) | 0 (0) |

Abbreviation: aSDoH, adverse social determinants of health.

Note: Columns 1 and 2 describe the domain and specific question, columns 3 and 4 display the comparison by literacy, and columns 5 and 6 display the comparison by language.

Following completion of the survey, all participants were asked an open‐ended question to identify social concerns that were not captured by the established screening tool. Living conditions and social situations, such as residential co‐inhabitants, domestic violence, marital/relationship status, dependent status, sexual orientation, gender identity, occupational difficulties, and immigration issues were identified, as well as community level factors such as lengthy distances between home and resources (eg, stores), non‐availability of home health aides, and limited space for physical activity.

3.2. Quantitative outcome: Satisfaction with screening process

A large majority of participants (n = 191, 81%) reported satisfaction with the screening process. In total, 94 (82%) in the verbal screening group reported high satisfaction (extremely or quite a bit satisfied) and 97 (80%) in the electronic group. Screening modality was not associated with satisfaction with screening process after adjustment for language, health literacy, and aSDoH (aOR, 0.74; 95% confidence interval, 0.32, 1.71). Similarly, none of the other variables (language, health literacy, and aSDoH) were associated with high satisfaction with screening process in the adjusted model (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Adjusted model of association with outcome of satisfaction with screening process

| Variable | OR | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Screening modality | Verbal | Ref | |

| Electronic | 0.739 | 0.320, 1.708 | |

| Language spoken | English | Ref | |

| Spanish | 0.894 | 0.219, 3.643 | |

| Health literacy | Limited | Ref | |

| Adequate | 0.523 | 0.218, 1.253 | |

| aSDoH | None | Ref | |

| 1 or more | 0.615 | 0.216, 1.756 | |

Abbreviations: aSDoH, adverse social determinants of health; CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

Note: The above table depicts the results of the multivariable logistic regression model to estimate ORs and CIs for high satisfaction with screening process adjusting for language, health literacy and presence of an aSDoH; the screening modality was not significantly associated with satisfaction after adjustment.

3.3. Qualitative outcomes

Of the 236 randomized participants, 27 participants across the 4 predetermined groups were purposively sampled to complete the qualitative interview. Distribution across each sampling group was as follows: 7 (26%) adequate health literacy (HL)‐verbal, 4 (15%) limited HL‐verbal, 7 (26%) adequate HL‐electronic, and 9 (33%) limited HL‐electronic. Interview themes included facilitators and barriers to screening (eg, potential for embarrassment, confidentiality and privacy concerns, and modality of screening), missed health‐related social needs/risks (eg, interpersonal stressors, domestic violence), and concerns about feasibility of screening (eg, logistics, timing, ED location, and technical requirements for an electronic modality). Table 5 provides a sample of quotes illustrative of the emerging themes.

TABLE 5.

Illustrative quotes by theme from select participant interviews a

| Themes | Electronic screening experience | Verbal screening experience | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adequate health literacy | Limited health literacy | Adequate health literacy | Limited health literacy | |

| 1. Embarrassment, confidentiality and privacy concerns, concerns related to screening modality |

Quote 1: “I think it's smarter to have it electronically because if someone does have an issue, they may not want to say it to someone. Whereas if you kind of have it privately and only you can see it on the iPad, people are more likely to be truthful about what their needs are or concerns or difficulties. Whereas if you ask someone, they could be embarrassed or for another reason, just not tell the truth…”. Quote 2: “Yeah. I mean, one of the questions says, “Do you have enough money to feed your kids?” And I think a lot of people might not tell the truth, right? Because nobody wants to be in the position of not being able to feed their kids, right? So, I think electronic is much better than verbal.” |

Quote 1: “Well, for me, I do like verbally better because, when you asked me what I thought, everything that I didn't mention on the form? I told you. I told you my income, I told you how I'm struggling, but it made it more clear to you than if… it was better for the researcher to hear it verbally because I gave more information.” |

Quote 1: “I think doing it in person is a lot more fun. And I think you could get a lot—for me, I was able to be a little more thoughtful with the dialogue sharing between people.” Quote 2: “I can certainly imagine a situation in which someone did have a need but was, perhaps, embarrassed to share that in an oral survey and would be more inclined to be truthful if they were taking it in a more anonymous fashion.” |

Quote 1: “Just because it's on paper instead of just saying it, so you just read it… Probably people who are homeless or struggling with money situations and all that. It's a little embarrassing to be going through stuff like that sometimes for some people, so I feel like it would be better for them.” |

| 2. Missed HRSN in the formal survey |

Quote 1: “You would probably get more information from me if you were interviewing me face‐to‐face because you probably can add some questions to my answers. So, in that sense, yes. But I know what you're maybe asking about. Not having someone in front of me and feeling like maybe it's confidential and I'm just giving my answers to the iPad, not to the person, maybe it would be easier for me to open up if I really had some issues. You know what I mean?” Quote 2: “I don't know. Because it really depends on the person. I think doing the first screening here like you did with the iPad is nice because you can kind of find out that maybe there are some issues and then follow up with someone like if a person that comes in and talks, then I think that would be the best in my opinion.” |

Quote 1 a : R: “Do you think that it would have been different if we weren't asking you these questions but maybe the doctor was asking you or a nurse?” P: “Yeah, because sometimes I don't talk problems with doctors. Sometimes I hold back a little bit, which is not good because you're supposed to be able to talk to your doctor about everything. But it's just awkward.” |

Quote 1 a : R: “Do you think there's any information that we would have missed using an electronic survey or in the verbal survey, as well?” P: “I couldn't have told my story. Things like that. If someone wants to add– as a researcher, I think it's a benefit to hear additional things people might share…I mean, a lot of times it's the money issues. I know of people that forgo medicine because they don't have the money for it.” |

|

| 3. Concerns about feasibility, including logistics, timing, location of screening, and technical skills |

Quote 1: “Make sure they're comfortable with the electronics. Give them the option of a paper one if they don't want to do electronic one that you can [inaudible] later. So, if they're not comfortable with that or they've never seen an iPad or don't have one, don't know how to scroll through the questions together. Click on the box to get the keyboard to get the numbers or whatever. That might make them feel uncomfortable and maybe not want to proceed with the survey…”. Quote 2 a : R: “Do you think we should be asking these questions?” P: “Yes. I think so.” Quote 3: “I mean, not everybody goes to primary care doctor. Sometimes they cannot afford it and they go to emergency room. So probably asking in this setting is a good idea because you have a lot of people who just come here when they have emergencies, but they don't usually have someone who follows them up…”. |

Quote 1: “Because it's high anxiety and the pain and everything else you're experiencing being in an emergency room. And your mind is not really focused on answering questions, to be honest.” |

Quote 1: “I think that it's a really important tool to get information, as you said, about the community that the hospital, specifically, the emergency room is serving. I, personally, am not at risk for a lot of situations that were addressed in the survey. But I know that a lot of people are, and it's good for the hospital to be aware of that and be able to provide resources for those that are in need…”. |

Quote 1 a : R: “Speaking of those types of questions. Do you believe that we should be asking such questions of patients in an emergency department?” P: “Yes, it's fine. Yes, I like this, yes.” R: “Why?” P: “Well, because many times one doesn't know about things that would interest them. You, you are informed about this, about these programs. So, it's good. Yes, I like it.” R: “Okay. And do you believe that it is our job as a health system, that we should be asking our patients about their needs?” P: “Yes, it's fine. Yes, it's good. Yes, it doesn't bother me. It's fine.” Quote 2 a : R: “Okay. Okay. Do you think that it's better done here in the emergency department, or do you think it'd be better maybe in a primary care or in another situation?” P: “Probably the emergency room.” R: “Okay. Why do you think so?” P: “Because everybody comes here, and if you're homeless you're more likely maybe to come here because it's easier to get sick or get injured in any type of way, so.” |

Abbreviations: HRSN, health‐related social needs; P, participant; R, researcher.

In dialogue quotes.

3.3.1. Theme 1: facilitators and barriers

Regarding privacy, many participants discussed that the electronic survey might be less embarrassing to complete with more honest answers provided: “Yeah. I would say maybe written and electronic. I think if somebody was answering maybe like yes to any of those questions, it might be embarrassing or they might not feel comfortable saying that they had trouble getting food, or that they're worried about paying their bills. So, you might get more honesty if it's written or on an iPad” (adequate HL‐electronic). Participants had mixed preferences for survey modality (Table 5), although the preferred modality frequently coincided with the experienced modality.

3.3.2. Theme 2: missed aSDoH

Following the post‐survey open‐ended question on missed aSDoH, qualitative interview participants infrequently identified additional missed aSDoH. One participant did identify an important relational social risk not addressed by the established screener that is worth noting, and suggests that perhaps an electronic screener may have advantages for disclosure privacy: “So you addressed transportation. That's a big one. And then food needs, housing needs. And then there's domestic violence. But, again, I'm not sure how much people are going to be willing to talk about that in an oral interview. But that could potentially contribute I imagine” (adequate HL‐verbal).

3.3.3. Theme 3: feasibility of screening

Participants were open to the notion of ED screening, particularly in the role of capturing patients who were missed in the primary care setting: “I would think that the primary care setting might be a little bit more ideal because there's a long‐term relationship between the primary care team and the patient. But, on the other hand, there are plenty of patients out there in the community that don't really have that type of relationship with their PCP, and the emergency room could, certainly, be a safety net for them. A good place to catch those patients” (adequate HL‐verbal).

4. LIMITATIONS

Several limitations are worth noting. First, our findings may not be generalizable to the broader ED patient population. In the current analysis, the study cohort is recruited from a single academic medical center and is predominantly non‐Hispanic White and educated with adequate health literacy. These characteristics are more likely to be associated with individuals who have lower levels of aSDoH and greater ease with electronic surveys and technology in general, potentially skewing the data toward patient satisfaction with screening process regardless of screening modality. The screening tool was developed for use within our health system, with the choice of included SDoH driven by institutional consensus, and has not been externally validated. Additionally, the tool was delivered by a research assistant and additional work is needed to investigate how verbal or electronic screening would perform as part of routine ED practice.

Additionally, the study lacked sufficient power to perform an analysis based on primary language spoken. Participants for whom Spanish was the primary language accounted for a small percentage (8%) of the larger cohort. As a result, the study may be underpowered to detect any significant differences in satisfaction with screening process or disparities in social risks specifically related to limited English proficiency as compared to race/ethnicity. However, we were able to adjust for health literacy across both linguistic groups and conduct qualitative assessments in English and Spanish.

Third, reported satisfaction with screening process in the ED may be subject to social desirability bias. In this case, participants may report higher levels of satisfaction with the screening process than actually experienced. Social desirability bias may have also inhibited the sharing of important feedback about the screening program during the compensated qualitative interviews, or potentially caused patients to report a preference for the screening method they experienced. We recognize the limitations of satisfaction as a measure of screening success, but given the absence of gold standard outcomes for screening and our interest in understanding patient preferences among verbal versus electronic screening modalities, we felt that was the optimal quantitative outcome, and acknowledge the important contextual information provided by the qualitative interviews to enhance our understanding of the participant experience in screening.

In addition, it is worth noting that although health insurance is often present with other beneficial SDoH, under the Affordable Care Act mandate and within the state of Massachusetts where a universal health plan has been in place since 2006 (ie, MassHealth), access to health insurance is not necessarily associated with higher levels of income, education, and health literacy or with favorable living and work conditions. Unfortunately, because of an exceedingly low number of uninsured and self‐pay participants (3%), it is difficult to determine from this study whether insurance status plays a role in the number and types of unmet aSDoH reported, although overall, this cohort of ED patients had high rates of social need and social risk.

Finally, the responses provided by ED patients who chose to enroll in the study may differ significantly from those who elected not to participate. The motivations for participation in the study population as well as the barriers to participation in those who declined enrollment may be worthwhile investigating to understand if individuals with higher levels of aSDoH are disproportionately missed by this study design.

5. DISCUSSION

This study demonstrates that screening for health‐related social needs and risks in the ED was acceptable to patients, with a large majority, 81%, reporting satisfaction with the screening process in the quantitative survey, and satisfaction was not associated with screening modality, language or health literacy. In the qualitative data, participants offered potential barriers relevant to the alternative modality. The verbal screening modality was more likely to raise concerns about embarrassment and privacy, whereas the electronic screening modality was felt to be limiting in that tailored questioning could not take place and therefore additional information would not be revealed. Similarly, a prior qualitative study on preferences for food insecurity screening emphasized the importance of anonymity and privacy. 19 These findings are consistent with research on patient screening preferences for intimate partner violence (IPV) where computer‐based screening has been associated with increased detection of IPV, 27 , 28 , 31 but mixed results from interviews with IPV survivors suggest differing advantages of both face‐to‐face and computer‐based screening. 32 , 33 , 34

A prior study examining screening modalities in the pediatric setting found higher rates of disclosure in the computer‐based group as compared to the face‐to‐face group. 18 The difference between this study and our study, in part, may be due to differences in questions asked as we did not include questions on substance use in the home or request that participants disclose their annual household income. Additionally, there was much higher uptake of screening in the study by Gottlieb et al 18 with only 14% refusing screening, potentially suggesting differential willingness to participate in social screening in pediatric versus adult care settings, although additional work is needed to further investigate this distinction.

Given the time and resource constraints of the ED, additional work is needed to develop strategies to best match patient needs and preferences to the optimal screening modality. Some patients prefer the privacy of the electronic system, but others with limited vision, reading, or technological literacy would benefit from verbal screening. Beyond optimizing the screening modality, additional work is needed to develop strategies for effectively addressing identified social risk and need within the ED setting. Finally, development and validation of a brief, ED‐specific tool may provide more opportunities for streamlined screening. 35

Another salient outcome of this study is the support it lends to the increasing screening among ED patients. Only 39% of EDs within our region are screening for social needs. 6 Despite the favorable insurance profile in our ED (94.5% insured), likely due to the enrollment within Massachusetts, two‐thirds of the 236 participants, 67% (n = 158), reported social needs or risks in this study.

In our data, food (24%) and housing (18%) were the most commonly reported aSDoH. Prior studies rates of food insecurity above 20% and have rates of 18%–44% for unstable housing. 36 This suggests that rates may be higher in populations without insurance or with lower educational attainment than our study population. Such unmet basic needs carry profound implications on health outcomes and health care utilization, including increased hospitalization rates in patients with food and housing insecurity, 37 , 38 , 39 difficulty traveling to and from health appointments,38 difficulty obtaining employer‐subsidized health insurance coverage, barriers to prescribed medication adherence,39 and inability to refrigerate medicines like insulin (electricity) and keep warm in the winter months (heat). An open‐ended question inquiring about social needs and risks not covered in the screener resulted in the identification of interpersonal relational risks (eg, domestic violence), stigma (eg, sexual orientation/gender identity), occupational troubles, immigration issues, limited access to material (eg, stores) and human resources (eg, home health aides), and inadequate space for physical activity. These findings support a more robust and systematic effort to conduct social screenings in the ED through which patients can be linked to appropriate social supports and resources.

This study demonstrates that both verbal and electronic screening processes were acceptable to patients, and that multimodal screening options may be beneficial to meet the widely varied needs and preferences for patients around social screening. With increasing emphasis on screening, it is of key importance to ensure that such screening is patient‐centered, acceptable to the community served, and able to extract the relevant information to enable linkage to services and improved health outcomes. Future ED‐based screening efforts can consider use of electronic tools to streamline the screening process and expand scalability and sustainability.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

WMK and MSK conceived and designed the study. WMK, GC, and MSK supervised the conduct of the study. GC and MSK collected the data. AM provided statistical support and analyzed the data. WMK and MSK interpreted the data and WMK drafted the manuscript. GC and MSK contributed to critical revisions and all authors approved the final manuscript draft. WMK takes responsibility for the paper as a whole.

Supporting information

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank research assistants Arthur Ramirez, Jennifer Manzano, Anna Thorndike, Chevonne Parker, Vianelly Garcia, Cynthia De Leon, Megan Halloran, Brianna Rutty, and Danae Webster for consenting and enrolling participants into the study as well as conducting the verbal health‐related social needs surveys and overseeing the use of the electronic survey modality. The authors would like to further thank Anna Thorndike and Chevonne Parker for also conducting qualitative interviews with a subset of participants. This study was financially supported by grant funding from the Massachusetts General Hospital Executive Committee on Community Health. The funding source had no influence over the design, conduct, or analysis of this study.

Biography

Wendy Macias‐Konstantopoulos, MD, MPH, is an Associate Professor of Emergency Medicine at Harvard Medical School and attending physician in the Department of Emergency Medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH). She is Director of the Center for Social Justice and Health Equity and Founding Executive Director of the MGH Freedom Clinic.

Macias‐Konstantopoulos W, Ciccolo G, Muzikansky A, Samuels‐Kalow M. A pilot mixed‐methods randomized controlled trial of verbal versus electronic screening for adverse social determinants of health. JACEP Open. 2022;3:e12678. 10.1002/emp2.12678

Supervising Editor: Chadd Kraus, DO, DrPH.

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03834441

REFERENCES

- 1. Social determinants of health. World Health Organization. Accessed March 29, 2020. 2018. https://www.who.int/social_determinants/en/on. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Braveman P, Gottlieb L. The social determinants of health—it's time to consider the causes of the causes. Public Health Rep. 2014;129(2):19‐31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Samuels‐Kalow ME, Ciccolo GE, Lin MP, Schoenfeld EM, Camargo CA. The terminology of social emergency medicine: measuring social determinants of health, social risk, and social need. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. 2020;1(5):852‐856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Accountable Health Communities model. Accessed February 25, 2021 https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/ahcm/on.

- 5. Alley DE, Asomugha CN, Conway PH, Sanghavi DM. Accountable Health Communities—addressing social needs through Medicare and Medicaid. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(1):8‐11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Samuels‐Kalow ME, Boggs KM, Cash RE, et al. Screening for health‐related social needs of emergency department patients. Ann Emerg Med. 2021;77(1):62‐68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Molina MF, Li CN, Manchanda EC, et al. Prevalence of emergency department social risk and social needs. West J Emerg Med. 2020;21(6):152‐161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shah R, Della Porta A, Leung S, et al. A scoping review of current social emergency medicine research. West J Emerg Med. 2021;22(6):1360‐1368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Capp R, Kelley L, Ellis P, et al. Reasons for frequent emergency department use by Medicaid enrollees: a qualitative study. Acad Emerg Med. 2016;23(4):476‐481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fredrickson DD, Molgaard CA, Dismuke SE, Schukman JS, Walling A. Understanding frequent emergency room use by Medicaid‐insured children with asthma: a combined quantitative and qualitative study. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2004;17(2):96‐100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rodriguez RM, Fortman J, Chee C, Ng V, Poon D. Food, shelter and safety needs motivating homeless persons' visits to an urban emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;53(5):598‐602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Baggett TP, Singer DE, Rao SR, O'Connell JJ, Bharel M, Rigotti NA. Food insufficiency and health services utilization in a national sample of homeless adults. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(6):627‐634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Basu S, Berkowitz SA, Seligman H. The monthly cycle of hypoglycemia: an observational claims‐based study of emergency room visits, hospital admissions, and costs in a commercially insured population. Med Care. 2017;55(7):639‐645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Losonczy L, Hsieh D, Hahn C, Fahimi J, Alter H. More than just meds: national survey of providers’ perceptions of patients’ social, economic, environmental, and legal needs and their effect on emergency department utilization. Soc Sci Med. 2015;9(1):22‐28. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Vaz LE, Wagner DV, Ramsey KL, et al. Identification of caregiver‐reported social risk factors in hospitalized children. Hosp Pediatr. 2020;10:20‐28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Buitron de la Vega P, Losi S, Sprague Martinez L, et al. Implementing an EHR‐based screening and referral system to address social determinants of health in primary care. Med Care. 2019;57(Suppl 6 Suppl 2):S133‐S139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Garg A, Sheldrick RC, Dworkin PH. The inherent fallibility of validated screening tools for social determinants of health. Acad Pediatr. 2018;18:123‐124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gottlieb L, Hessler D, Long D, Amaya A, Adler N. A randomized trial on screening for social determinants of health: the iScreen study. Pediatrics. 2014;134(6):e1611‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cullen D, Woodford A, Fein J. Food for thought: a randomized trial of food insecurity screening in the emergency department. Acad Pediatr. 2019;19(6):646‐651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Davis K, Minckas N, Bond V, et al. Beyond interviews and focus groups: a framework for integrating innovative qualitative methods into randomised controlled trials of complex public health interventions. Trials. 2019;20(1):329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. O'Cathain A, Thomas KJ, Drabble SJ, Rudolph A, Goode J, Hewison J. Maximising the value of combining qualitative research and randomised controlled trials in health research: the QUAlitative Research in Trials (QUART) study—a mixed methods study. Health Technol Assess. 2014;18(38):1‐197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Report F, Storey M, Porter A, Snooks H, Jones K, Peconi J, et al. Qualitative research within trials: developing a standard operating procedure for a clinical trials unit. Trials. 2013;14:54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Osborn CY, Weiss BD, Davis TC, et al. Measuring adult literacy in health care: performance of the newest vital sign. Am J Health Behav. 2007;31(1):S36‐46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hernan MA, Hernandez‐Diaz S, Robins JM. Randomized trials analyzed as observational studies. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159(8):560‐562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. Chicago, IL: Aldine Publishing; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bradley EH, Curry LA, Devers KJ. Qualitative data analysis for health services research: developing taxonomy, themes, and theory. Health Serv Res. 2007;42(4):1758‐1772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ahmad F, Hogg‐Johnson S, Stewart DE, Skinner HA, Glazier RH, Levinson W. Computer‐assisted screening for intimate partner violence and control: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(2):93‐102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rhodes KV, Drum M, Anliker E, Frankel RM, Howes DS, Levinson W. Lowering the threshold for discussions of domestic violence: a randomized controlled trial of computer screening. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(10):1107.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rhodes KV, Lauderdale DS, He T, Howes DS, Levinson W. Between me and the computer”: increased detection of intimate partner violence using a computer questionnaire. Ann Emerg Med. 2002;40(5):476.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. MacMillan HL, Walthen CN, Jamieson E, et al. Approaches to screening for intimate partner violence in healthcare settings: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2006;296(5):530‐536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Trautman DE, McCarthy ML, Miller N, et al. Intimate partner violence and emergency department screening: computerized screening versus usual care. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;49:526‐534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Chang JC, Dado D, Schussler S, et al. In person versus computer screening for intimate partner violence among pregnant patients. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;88(3):443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ciccolo GE, Curt A, Camargo C, Samuels‐Kalow M. Improving understanding of screening questions for social risk and social need for emergency department patients. West J Emerg Med. 2020;21(5):1170–1174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Malecha PW, Williams JH, Kunzler NM, Goldfrank LR, Alter HJ, Doran KM. Material needs of emergency department patients: a systematic review. Acad Emerg Med. 2018;25(3):330‐359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Samuel LJ, Szanton SL, Cahill R, et al. Does the supplemental nutrition assistance program affect hospital utilization among older adults? The case of Maryland. Popul Health Manag. 2018;21(2):88‐95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Thomas KS, Dosa D. More Than a Meal: Results from a Pilot Randomized Control Trial of Home‐Delivered Meal Programs. Providence, RI: Brown School of Public Health; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hunter SB, Harvey M, Briscombe B, Cefalu M. Evaluation of Housing for Health Permanent Supportive Housing Program. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chaiyachati KH, Hubbard RA, Yeager A, et al. Rideshare‐based medical transportation for Medicaid patients and primary care show rates: a difference‐in‐difference analysis of a pilot program. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33:863‐868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hensley C, Heaton PC, Kahn RS, Luder HR, Frede SM, Beck AF. Poverty, transportation access, and medication nonadherence. Pediatrics. 2018;141(4):e20173402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

SUPPORTING INFORMATION