Abstract

Purpose. The purpose of this study was to assess the feasibility and effectiveness of a whole food plant-based diet (WFPBD) to improve day of surgery fasting blood glucose (FBG) among patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D). Patients and Methods. Ten patients with T2D scheduled for a total hip or total knee replacement were recruited. For 3 weeks preceding their surgeries, subjects were asked to consume an entirely WFPBD. Frozen WFPBD meals were professionally prepared and delivered to each participant for the 3 weeks prior to surgery. FBG was reassessed on the morning of surgery and compared with preintervention values. Compliance with the diet was assessed. Results. Mean age of subjects and reported duration of diabetes was 65 and 8 years, respectively, average hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) was 6.6%, and 6 were women. Mean FBG decreased from 127 to 116 mg/dL (P = .2). Five of the subjects experienced improvement in glycemic control, with an average decline of 11 mg/dL. Conclusion. A WFPBD is a potentially effective intervention to improve glycemic control among patients with T2D during the period leading up to surgery. Future controlled trials on a larger sample of patients to assess the impact of a WFPBD on glycemic control and surgical outcomes are warranted.

Keywords: diabetes, perioperative, prehabilitation, whole food plant-based diet, vegan

‘Strategies to effectively improve hyperglycemia prior to day of surgery in a short span of time are needed.’

Despite improvements in surgical technique, the rate of postoperative joint infections has not improved among patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D). 1 Hyperglycemia increases the risk of postoperative infection following total joint arthroplasty, 2 likely through impairment of immune function.3-5 Additionally, hyperglycemia is an independent risk factor in postoperative mortality.6,7

The time between when the patient is cleared for surgery and the day of surgery itself may be short, not allowing for sufficient time to improve glycemic control. Data from the authors’ institution indicate that a minimum of 10 days may be needed to optimize day of surgery glucose levels. Strategies to effectively improve hyperglycemia prior to day of surgery in a short span of time are needed. Pharmacological approaches (eg, multiple daily insulin injections) could be used, but would have to be very aggressive to be effective in such a short time frame and would increase the risk of hypoglycemia. A safer potential solution (without risk of hypoglycemia) to improve glucose control prior to surgery would be a dietary modification. Therefore, we conducted a feasibility study to explore whether a whole food plant-based diet (WFPBD) intervention might be able to effectively improve blood glucose among a cohort of patients with T2D.

Methods

Subject Recruitment

At the authors’ institution, approximately 40% of all surgical patients are seen in our Preoperative Evaluation Clinic (POE) prior to the surgical date. Typically, these POE visits are for medically complex patients. Per institutional policy, any patient with T2D is seen in POE prior to surgery. A recent retrospective study found that when HbA1c is greater than 8%, the minimum amount of time needed for glucose improvement is 10 days. 8 Similarly, based on another study from 2009. 9 documenting effective reversal of T2D with a WFPBD, at least 16 days were needed, which is why this protocol employed a dietary intervention lasting 3 weeks.

Subjects were identified, screened, and consented during the POE visit. Adult (>18 years old) subjects with T2D scheduled for elective total hip arthroplasty or total knee arthroplasty were included. Candidates with unresolved substance abuse, pregnancy, history of severe mental illness, current use of warfarin (Coumadin), prior history of small bowel obstruction, or any unstable medical condition were excluded. As is our standard practice for patients with diabetes mellitus, baseline fasting blood glucose (FBG), HbA1c, and body mass index (BMI) were obtained at their POE appointment. Subjects agreed to accept and adopt dietary changes for a period of 3 weeks before surgery.

Diet Description

The WFPBD consists of maximal consumption of nutrient-dense plant foods such as vegetables, fruit, legumes, grains, nuts, and seeds, while minimizing processed foods, added sugars, oils, and animal-based foods (such as meat, fish, poultry, and dairy). 10 Participants learned about a WFPBD via an hour-long meeting face-to-face with a registered dietitian. In addition, they were given a resource sheet with recommended evidence-based readings, websites, and documentaries. Three weeks of WFPBD foods (supplied by Kitchen Therapy Inc, New York, NY), were delivered frozen to the subjects. A facilitator was available by phone for further questions. FBG was drawn again on the morning of surgery, to serve as an end of intervention data point.

Assessment of Compliance

Randomized controlled trials in the medical literature show adherence to WFPBD is at least equal to and sometimes superior to other diets. 11 In order to assess compliance during the study, subjects completed a validated Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ) and a lifestyle questionnaire before and after the intervention. Additionally, subjects filled out a daily food log. The FFQ asks 30 questions about subjects’ regular consumption of vegetables, fruits, meat, dairy, and processed foods. 12

Data Analysis

A biostatistician analyzed the descriptive analysis for the 10 subjects, including demographics, clinical characteristics, and questionnaire answers. We used a paired t test for FBG and HbA1c between the preoperative visit and the day of surgery. Data are reported as mean (SD) or percentages where applicable.

Results

Subject Characteristics

Ten subjects completed the study (6 women, 4 men). Ages ranged from 56 to 75 years with a mean age of 65 (SD = 6) years. Two patients self-identified as Latinx, 1 as Native American, and 7 as Caucasian. Self-reported duration of diabetes mellitus ranged from 1 to 24 years with a mean of 8 (SD = 7) years. One patient was using only insulin therapy, 8 patients were on insulin therapy with at least one oral hypoglycemic medication, and 1 patient was on only oral hypoglycemics.

Changes in Glycemic Control

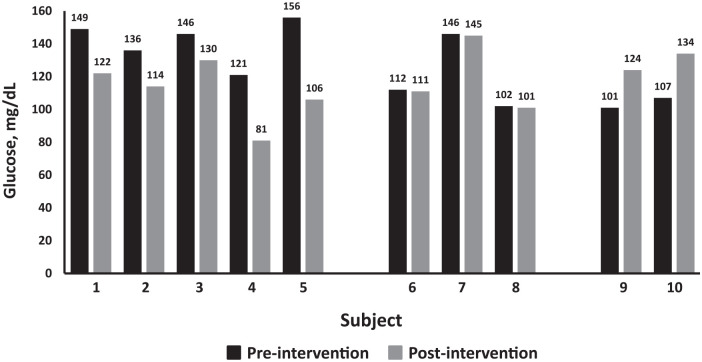

Mean HbA1c preintervention was 6.6% (SD = 0.6%) and postintervention was 6.3% (SD = 0.62%). Mean FBG preintervention was 128 (SD = 21) mg/dL and postintervention was 117 (SD = 18) mg/dL (P = 0.2). During the 3-week plant-based intervention, subjects’ FBG decreased 11 mg/dL (SD 25) points on average. HbA1c decreased by 0.36%. One subject essentially reversed his T2D and he discontinued all medication, including insulin. Additionally, subjects reported losing an average of 3.2 kg in the 3-week preoperative period. Nonetheless, not all subjects showed improvement in glucose levels. Five participants (Figure 1, subjects 1 to 5) improved their glycemic control, 3 (subjects 6 to 8) were minimally reduced (essentially unchanged), and 2 (subjects 9 and 10) showed higher glucose levels on the day of surgery compared with preintervention levels.

Figure 1.

Changes in fasting blood glucose (FBG) in 10 subjects with type 2 diabetes (T2D) prescribed a whole food plant-based diet (WFPBD) for 3 weeks leading up to total hip or total knee arthroplasty. Data are grouped into those who showed improvement, those who had no change, and individuals whose FBG was higher on day of surgery.

Relationship Between and Preoperative Glucose Improvement and Dietary Adherence

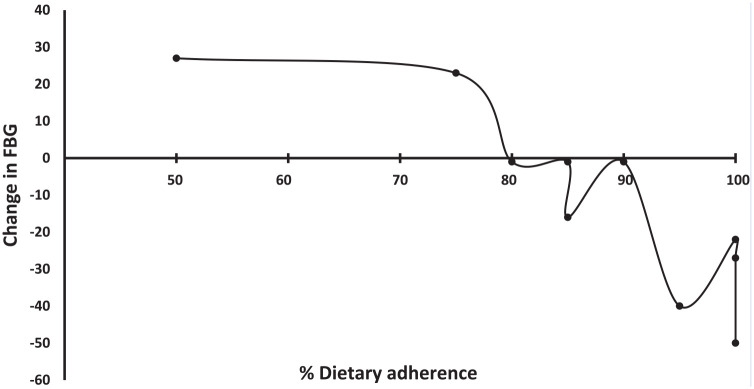

Subjects who adhered more than 80% of the time to the prescribed diet had the most improvement in glycemic control (Figure 2). Those who adhered the most to the WFPBD saw the most dramatic shifts, those who adhered less, had less glucose improvement (Pearson correlation coefficient between change of FBG and adherence: −0.85; P = .002). Of the 2 subjects whose glucose levels were higher on the day of surgery relative to the preintervention value, 1 drank apple juice, instead of fasting the morning of surgery, and the other stated she followed the prescribed diet only about 50%.

Figure 2.

Relationship between change in fasting blood glucose (FBG) with adherence to a whole food plant-based diet (WFPBD) among 10 subjects with type 2 diabetes (T2D) scheduled for total hip or total knee arthroplasty in the 3-week period prior to surgery.

Discussion

Optimizing glucose control prior to an elective surgical procedure is one of the modifiable factors that can assure better postoperative outcomes among patients with T2D. However, there is a paucity of data on how best to achieve this goal in the limited time that is often available once the poor glucose control in identified before the day of surgery. This feasibility study was undertaken to determine if use of a WFPBD could achieve rapid glucose control in preparation for surgery. This case series suggests that a WFPBD can improve fasting glucose and had another beneficial side effect in the form of weight loss. As above, dietary adherence correlated with change in FBG. One subject was able to discontinue his diabetic medications.

The beneficial effect of a WFPBD on glycemic control in T2D has been well-documented.13,14 This study is the first to look at the combined effect of a WFPBD for management of T2D in the period preceding the day of surgery. Attention to presurgical patient preparation is an emerging field of study called preoperative prehabilitation.15-22

Within the context of preoperative prehabilitation, nutrition intervention studies have been reductionist in nature, looking at individual foods or single components of foods for their beneficial effects. For example, the protective effects of flaxseed appear to reduce prostate cancer burden. 23 Moreover, polyunsaturated fatty acids have been studied for their possible effect on immune response and inflammation in subjects undergoing surgical intervention for multiple types of cancer. 24 Short-term calorie and fat restriction before liver resection reduced both steatohepatosis and steatohepatitis, but did not affect overall disease progression. 25 Severe preoperative calorie restriction was tested in subjects undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy, 26 mammoplasty, 27 and gastric bypass.28,29 While these latter interventions may enable weight loss, there could be negative consequences associated with very low calorie diets and rapid weight loss; namely, risk of preoperative hypovolemia and gallstone formation. 30

Previously, the medical literature suggested that excess carbohydrate intake was the main causative factor in T2D. 31 However, more recently, large population studies (including Adventist Health Study, Adventist Health Study 2, and European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition, which have collectively studied more than 120 000 people over 6 decades) show that a WFPBD, which may be carbohydrate-rich, is just as effective, if not more effective, than other diabetes diets in treating and preventing diabetes, as well as improving body weight and dyslipidemia.32,33 Furthermore, randomized controlled trials (RCTs), have compared the American Diabetes Association (ADA) recommendations for diet and a WFPBD, and have shown a WFPBD is more effective at glucose control, and disease reversal.14,34,35

There are several limitations to this study. The small sample size is more representative of a case series and included subjects with only T2D. Additionally, there was no control group (eg, a group that received conventional preoperative counseling regarding the importance of glycemic control without a dietary intervention). Future studies should include a larger sample size and control group. The study cohort started with a level of hyperglycemia that on average met current goals for glycemic control, and the effect on hyperglycemia may have been greater in participants with higher starting HbA1c levels. Finally, the sustainability of the WFPBD beyond surgery would be of interest.

Conclusion

Despite the limitations, this study served as a proof-of-concept study to assess the feasibility and effectiveness of WFPBD on preoperative glycemic control. From a feasibility standpoint, most subjects were able to demonstrate compliance with the diet, and had improvements in glycemic control. From a financial standpoint, health care providers and health care businesses may want to consider offering perioperative lifestyle coaching, and in particular, guidance about the benefits of a WFPBD to combat chronic disease, as the evidence is clear: Healthier patients have easier recoveries and have less morbidity and mortality perioperatively than chronically ill patients. 36 Future controlled studies of implementation of a WFPBD are warranted in a larger sample size and the effect of such an intervention on surgical outcomes are needed.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Alicia Rankin, Research Coordinator for her expertise. Additional thanks to Federico Petrelli and Kitchen Therapy for delivering the meals used for this study.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was supported by an internal grant from Mayo Clinic.

Ethical Approval: Not applicable, because this article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects.

Informed Consent: Informed consent was obtained from all patients in this study.

Trial Registration: Not applicable, because this article does not contain any clinical trials.

ORCID iD: Jennifer M. Drost  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7244-2372

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7244-2372

References

- 1.Tande AJ, Patel R. Prosthetic joint infection. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2014;27:302-345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Watts CD, Houdek MT, Wagner ER, Abdel MP, Taunton MJ. Insulin dependence increases the risk of failure after total knee arthroplasty in morbidly obese patients. J Arthroplasty. 2016;31:256-259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berrou J, Fougeray S, Venot M, et al. Natural killer cell function, an important target for infection and tumor protection, is impaired in type 2 diabetes. PLoS One. 2013;8:e62418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dronge AS, Perkal MF, Kancir S, Concato J, Aslan M, Rosenthal RA. Long-term glycemic control and postoperative infectious complications. Arch Surg. 2006;141:375-380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Underwood P, Askari R, Hurwitz S, Chamarthi B, Garg R. Preoperative A1C and clinical outcomes in patients with diabetes undergoing major noncardiac surgical procedures. Diabetes Care. 2014;37:611-616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang TK, Woodhead A, Ramanathan T, Pemberton J. Relationship between diabetic variables and outcomes after coronary artery bypass grafting in diabetic patients. Heart Lung Circ. 2017;26:371-375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Halkos ME, Lattouf OM, Puskas JD, et al. Elevated preoperative hemoglobin A1c level is associated with reduced long-term survival after coronary artery bypass surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;86:1431-1437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patel SI, Thompson BM, McLemore RY, et al. Relationship between the timing of preoperative medical visits and day-of-surgery glucose in poorly controlled diabetes. Future Sci OA. 2016;2:FSO123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crane MS, Sample C. Regression of diabetic neuropathy with total vegetarian (vegan) diet. J Nutr Med. 1994;4:431-439. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tuso P, Stoll SR, Li WW. A plant-based diet, atherogenesis, and coronary artery disease prevention. Perm J. 2015;19:62-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Trapp C, Barnard N, Katcher H. A plant-based diet for type 2 diabetes: scientific support and practical strategies. Diabetes Educ. 2010;36:33-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Institute of Health. Dietary Screener Questionnaire. https://epi.grants.cancer.gov/nhanes/dietscreen/dsq_english.pdf. Accessed September 13, 2019.

- 13.Barnard ND, Cohen J, Jenkins DJ, et al. A low-fat vegan diet improves glycemic control and cardiovascular risk factors in a randomized clinical trial in individuals with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:1777-1783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barnard ND, Cohen J, Jenkins DJ, et al. A low-fat vegan diet and a conventional diabetes diet in the treatment of type 2 diabetes: a randomized, controlled, 74-wk clinical trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89:1588S-1596S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Le Roy B, Slim K. Is prehabilitation limited to preoperative exercise? Surgery. 2017;162:192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gupta R, Gan TJ. Preoperative nutrition and prehabilitation. Anesthesiol Clin. 2016;34:143-153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dadure C, Sola C, Capdevila X. Preoperative nutrition through a prehabilitation program: A key component of transfusion limitation in paediatric scoliosis surgery. Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med. 2015;34:311-312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen BP, Awasthi R, Sweet SN, et al. Four-week prehabilitation program is sufficient to modify exercise behaviors and improve preoperative functional walking capacity in patients with colorectal cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25:33-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carli F, Feldman LS. From preoperative risk assessment and prediction to risk attenuation: a case for prehabilitation. Br J Anaesth. 2019;122:11-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cabilan CJ, Hines S, Munday J. The effectiveness of prehabilitation or preoperative exercise for surgical patients: a systematic review. JBI Database Syst Rev Implement Rep. 2015;13:146-187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boudreaux AM, Simmons JM. Prehabilitation and optimization of modifiable patient risk factors: the importance of effective preoperative evaluation to improve surgical outcomes. AORN J. 2019;109:500-507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baldini G, Ferreira V, Carli F. Preoperative preparations for enhanced recovery after surgery programs: a role for prehabilitation. Surg Clin North Am. 2018;98:1149-1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Demark-Wahnefried W, Polascik TJ, George SL, et al. Flaxseed supplementation (not dietary fat restriction) reduces prostate cancer proliferation rates in men presurgery. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:3577-3587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nakamura K, Kariyazono H, Komokata T, Hamada N, Sakata R, Yamada K. Influence of preoperative administration of omega-3 fatty acid-enriched supplement on inflammatory and immune responses in patients undergoing major surgery for cancer. Nutrition. 2005;21:639-649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reeves JG, Suriawinata AA, Ng DP, Holubar SD, Mills JB, Barth RJ., Jr. Short-term preoperative diet modification reduces steatosis and blood loss in patients undergoing liver resection. Surgery. 2013;154:1031-1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jongbloed F, de Bruin RW, Klaassen RA, et al. Short-term preoperative calorie and protein restriction is feasible in healthy kidney donors and morbidly obese patients scheduled for surgery. Nutrients. 2016;8:E306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Geiker NR, Horn J, Astrup A. Preoperative weight loss program targeting women with overweight and hypertrophy of the breast—a pilot study. Clin Obes. 2017;7:98-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kalarchian MA, Marcus MD, Courcoulas AP, Cheng Y, Levine MD. Preoperative lifestyle intervention in bariatric surgery: initial results from a randomized, controlled trial. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2013;21:254-260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Van Nieuwenhove Y, Dambrauskas Z, Campillo-Soto A, et al. Preoperative very low-calorie diet and operative outcome after laparoscopic gastric bypass: a randomized multicenter study. Arch Surg. 2011;146:1300-1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Poso T, Kesek D, Aroch R, Winsö O. Rapid weight loss is associated with preoperative hypovolemia in morbidly obese patients. Obes Surg. 2013;23:306-313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sheard NF, Clark NG, Brand-Miller JC, et al. Dietary carbohydrate (amount and type) in the prevention and management of diabetes: a statement by the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:2266-2271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Le LT, Sabate J. Beyond meatless, the health effects of vegan diets: findings from the Adventist cohorts. Nutrients. 2014;6:2131-2147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.InterAct Constorium. Dietary fibre and incidence of type 2 diabetes in eight European countries: the EPIC-InterAct Study and a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Diabetologia. 2015;58:1394-1408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barnard ND, Scialli AR, Turner-McGrievy G, Lanou AJ, Glass J. The effects of a low-fat, plant-based dietary intervention on body weight, metabolism, and insulin sensitivity. Am J Med. 2005;118:991-997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Trapp CB, Barnard ND. Usefulness of vegetarian and vegan diets for treating type 2 diabetes. Curr Diab Rep. 2010;10:152-158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carli F, Scheede-Bergdahl C. Prehabilitation to enhance perioperative care. Anesthesiol Clin. 2015;33:17-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]