Abstract

This paper analyzes restaurant closure patterns during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. Using establishment-level data from Yelp and SafeGraph, I describe restaurant and location characteristics related to the closure decisions. Lower-rated restaurants and restaurants located closer to the city center were more likely to close in 2020.

Keywords: Restaurant closures, COVID-19 pandemic, Turnover

1. Introduction

During 2020, the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, restaurants suffered from reduced consumer traffic due to multiple factors: lockdowns, operations restrictions and social distancing. Which restaurants were more likely to exit the industry in this challenging time? I provide descriptive evidence on this question in the context of major US urban areas using data from the review platform Yelp and the location data company SafeGraph. Specifically, I explore location- and restaurant-specific characteristics that explain variation in restaurant closure decisions.

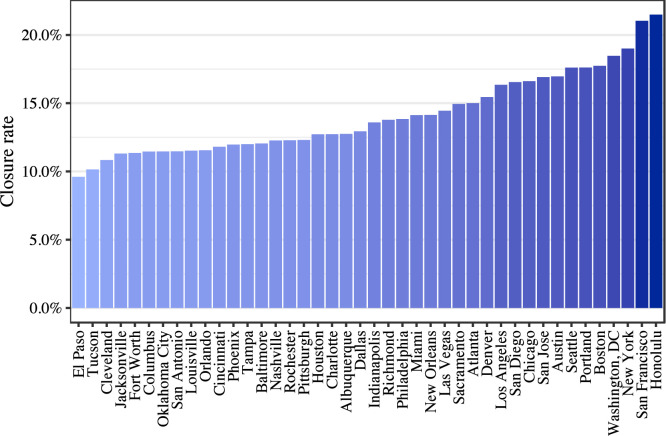

First, I document the across-cities differences in observed restaurant exit rates, which range from 9.6% in El Paso to 21.5% in Honolulu. Next, I estimate binary response econometric models and summarize the association between restaurant characteristics and exit. I find that higher rating scores and review counts are robustly associated with lower restaurant exit probabilities. A 1-star increase in the restaurant’s rating is associated with a roughly 1.2% lower chance of restaurant closure. Additional 100 reviews at the beginning of the observation period are associated with a lower probability of restaurant exit. Also, restaurants relying on the foot traffic generated due to their within-city location were relatively less likely to survive the pandemic year. While the exit data I use is likely imperfect in a way that complicates measuring the overall exit rate levels (which is a limitation of this paper), I view the latter results associating exit and restaurant characteristics as this paper’s main findings.

This paper contributes to several strands of literature. First, it adds to the growing research on business disruptions during the pandemic highlighting (1) the fragility of small businesses at the pandemic onset expressed in high closure and layoff rates (see Bartik et al. (2020), Fairlie (2020)); (2) the impact of government-imposed restrictions (e.g. Goolsbee and Syverson (2021), Koren and Peto (2020)); and (3) the methodological aspects of tracking business impact in a fast-changing environment (see Crane et al. (2021)). Belitski et al. (2021) provide a systematic literature review. This paper contributes to the research above by offering a unique focus on the restaurant industry enabled by establishment-level data. Closely related is the paper by Glaeser et al. (2021) studying how imposing and lifting stay-at-home orders can affect restaurant-related activities through consumer learning. Second, this paper expands the research describing factors specifically related to restaurant exit decisions (e.g. Parsa et al. (2011), Luo and Stark (2014), Parsa et al. (2021)) by employing Yelp and SafeGraph data from multiple major US cities and by concentrating on restaurant closures during the COVID-19 pandemic. Next, this paper is related to the IO literature dealing with turnover and firm entry/exit decisions (see early surveys by Geroski (1995) and Caves (1998) and subsequent updates by e.g., Audretsch et al. (2000), Agarwal and Audretsch (2001), Fackler et al. (2013)). Finally, this paper’s finding on a negative association between restaurant rating and exit during the pandemic contributes to the existing evidence that lower-rated businesses are also more heavily affected by economic shocks (see Luca and Luca (2019) on the minimum wage changes, Foster et al. (2008) is another related paper).

The rest of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 presents key facts about the data. Section 3 describes the econometric analysis of factors related to restaurant exit decisions. Section 4 concludes.

2. Data

Three data sources are used for the analysis discussed in this paper. The data from the Yelp restaurant review platform provides information on restaurant characteristics and exit decisions. I also use data from the location data company SafeGraph, which collects information on US points-of-interest (defined as places outside of home where people spend time and/or money), and the U.S. Census to construct additional covariates related to restaurant location characteristics. The combined dataset covers 128,285 restaurants in 42 major US cities.

The timing of Yelp data collection allows me to concentrate on the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. The data on restaurants’ names, locations and characteristics was first collected in late 2019 using a scraping routine that systematically parsed Yelp Fusion API.1 The second round of data collection was done in early 2021, using the previously gathered set of unique Yelp restaurant identifiers. The target element of interest during the second round was the restaurant-closed indicator, which I view as the ground truth on restaurant exit for the purposes of this paper.2

Next, thanks to the July 2019 extract of SafeGraph data, I can observe the locations of roughly 4.4 mln US establishments across multiple industries and quantify the proximity of restaurants to other businesses (see Abbiasov and Sedov (2021) or Sedov (2021) for a more detailed description of the SafeGraph dataset). Specifically, I use the counts of establishments in the 500-meter radius of each sample restaurant to quantify the likely restaurant reliance on the traffic generated by nearby establishments. Table 1, Manson et al., 2021, Sink, 2020 provides the summary statistics on the resulting dataset.

Table 1.

Restaurants dataset summary statistics. Number of observations: 128,285.

| % NA | Q10 | Q25 | Med | Q75 | Q90 | Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Closed | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 0.2 | 0.4 |

| Price | 16.6 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 1.6 | 0.6 |

| Rating | 0.0 | 2.5 | 3.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 4.5 | 3.6 | 0.9 |

| Reviews | 0.0 | 4.0 | 14.0 | 54.0 | 177.0 | 425.0 | 168.5 | 365.3 |

| # categories | 0.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 0.8 |

| City center dist. (km) | 0.0 | 1.3 | 3.2 | 7.3 | 12.9 | 18.7 | 8.9 | 7.4 |

| Est. nearby | 0.0 | 17.0 | 33.0 | 63.0 | 137.0 | 332.0 | 136.8 | 210.5 |

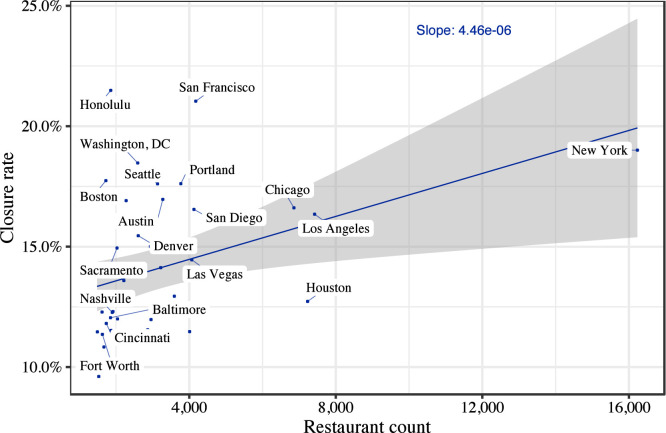

Several facts about the data are worth stating. 15.2% of restaurants in the sample closed in 2020. To illustrate the geographic variation in restaurant closures, Fig. 1 depicts the exit rates across sample cities. Honolulu featured the highest exit rate of 21.5% among the sample cities, while El Paso’s exit rate was the lowest at 9.6%. Fig. 2 displays the relationship between market size (measured as restaurant count on the city level) and restaurant closure rates. Larger markets have experienced higher restaurant exit rates: a 1000-increase in restaurant count is associated with a 0.46% increase in the restaurant closure rate. The positive relationship between market size and closure rates also survives controlling for variables that partially capture the possible differences in Yelp data quality across cities: (1) the city-level share of restaurants claimed by owners on Yelp’s platform and (2) the city-level population–restaurant ratio.

Fig. 1.

Restaurant closure rates across major US cities between late 2019 and early 2021.

Fig. 2.

Restaurant closure rates by market size (restaurant count).

It should be noted that the imperfection of Yelp’s exit data remains a limitation of this paper. I thus view the results of the next section, which focuses on the differences in observed closure rates by restaurant characteristics, as relatively more credible compared to the results on the observed levels of closure rates described in the paragraph above.

3. Exit-related factors

To understand the role of different factors shaping restaurant exit decisions, I estimate binary response models (LPM, logit and probit) linking closures and restaurant characteristics. In my empirical specification, restaurant characteristics include variables related to both the features of a restaurant itself and to the features of its location. Restaurant-specific characteristics include dummies for price categories, Yelp rating score and review count, primary cuisine category dummy and the total number of restaurants’ cuisine categories. Restaurant location features consist of city dummies, latitude and longitude, the count of nearby establishments as well as the distance from the city center.

Table 2 presents the coefficient estimates for the alternative binary response variables. Column (1) represents the LPM with city and cuisine category fixed effects, while column (2) represents the LPM with the interacted city–cuisine fixed effects. Column pairs (3)–(4) and (5)–(6) show the analogous estimates for logit and probit models respectively. The estimated coefficient signs are the same across specifications for all variables of interest. Moreover, the coefficient estimates appear to be robust to the alternative sets of fixed effects.

Table 2.

Coefficient estimates for the binary response models. Standard errors clustered at the FE levels for the LPM models. Latitude and longitude were included as covariates in all of the specifications but were omitted from the table; the corresponding coefficient estimates were insignificant. 4 observations were omitted from the analysis due to missing latitude/longitude.

| Dependent variable: restaurant closed |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

LPM |

Logit |

Probit |

||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| $ | −0.020 | −0.020*** | −0.118*** | −0.115*** | −0.077*** | −0.076*** |

| (0.017) | (0.005) | (0.025) | (0.025) | (0.013) | (0.014) | |

| $$ | 0.012 | 0.012* | 0.207*** | 0.206*** | 0.096*** | 0.095*** |

| (0.011) | (0.006) | (0.024) | (0.025) | (0.014) | (0.014) | |

| $$$ | 0.016 | 0.016 | 0.269*** | 0.273*** | 0.127*** | 0.128*** |

| (0.012) | (0.009) | (0.047) | (0.048) | (0.027) | (0.027) | |

| $$$$ | 0.002 | 0.003 | 0.145 | 0.161 | 0.061 | 0.067 |

| (0.014) | (0.014) | (0.096) | (0.097) | (0.054) | (0.055) | |

| Rating | −0.014** | −0.014*** | −0.099*** | −0.103*** | −0.054*** | −0.056*** |

| (0.005) | (0.002) | (0.010) | (0.010) | (0.006) | (0.006) | |

| Reviews (100s) | −0.009*** | −0.009*** | −0.140*** | −0.143*** | −0.067*** | −0.068*** |

| (0.001) | (0.000) | (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.002) | (0.002) | |

| Est. nearby (100s) | 0.012*** | 0.012*** | 0.069*** | 0.069*** | 0.042*** | 0.042*** |

| (0.003) | (0.002) | (0.004) | (0.004) | (0.002) | (0.003) | |

| City center dist. (km) | −0.002*** | −0.002*** | −0.024*** | −0.024*** | −0.012*** | −0.012*** |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.001) | (0.001) | |

| # categories | −0.007 | −0.007*** | −0.034*** | −0.035*** | −0.020*** | −0.021*** |

| (0.005) | (0.001) | (0.010) | (0.010) | (0.005) | (0.006) | |

| City FE | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Category FE | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| City-Category FE | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Observations | 128,281 | 128,281 | 128,281 | 128,281 | 128,281 | 128,281 |

| R2 | 0.026 | 0.033 | ||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.025 | 0.026 | ||||

| Log Likelihood | −52765.3 | −52217.4 | −52811.5 | −52267.0 | ||

Note:; ; .

I first discuss the restaurant characteristics coefficient estimates. The coefficient on the $-dummy is negative, indicating that, relative to the missing price label, $-priced restaurants were less likely to close in 2020. The coefficients on $$, $$$ and $$$$ are positive: higher-priced restaurants were more likely to close relative to the baseline. The coefficient on the $$$$-dummy, however, is not significant at the 5% level across all specifications. The rating and review count coefficients are negative and significant, implying that higher-quality and more frequently reviewed restaurants were less likely to close during the observation period. The total number of cuisine categories was estimated to have negative coefficients: restaurants with more diverse food were more likely to survive during 2020.

Several coefficients on the location-specific restaurant features provide additional insight. The coefficient on the count of nearby establishments is positive, indicating that restaurants that are located close to many other businesses were more likely to close. These restaurants likely relied on the foot traffic generated by the nearby establishments, and probably suffered relatively more from the pandemic, which is one of the channels that could result in higher exit rates among such restaurants. The negative coefficient on the variable measuring the distance from the city center indicates that centrally located restaurants were more likely to exit the business. Again, this may be related to a relatively higher fall of foot traffic to central city areas during the 2020 pandemic. To get further insight into this result, I estimate additional LPM specifications reported in Table 3. First, the distance from the city center has a weaker relationship with the restaurant exit probability in larger-area cities as indicated by the positive interaction term coefficient in column (1). The likely interpretation is that the same change in the nominal distance from the city center is linked to a higher activity change in smaller relative to larger cities. Second, the marginal change in the exit probability related to a unit change in distance falls as the distance from the city center increases, indicated by the positive sign of the quadratic distance term in column (2): the reliance on the downtown foot traffic is likely most important for central-most restaurants, quickly goes down with distance initially and at a slower rate for further-away restaurants. Finally, according to the estimates in column (2), restaurants in denser areas (measured by the population per km in the restaurants’ Census Block Groups) were more likely to close business, while restaurants in CBGs with a higher share of population below 25 years old were less likely to shut down. While denser areas likely saw stronger resident outflows and similarly higher closure rates during the pandemic, the younger population was relatively less affected by COVID and could have continued to patronize local restaurants.

Table 3.

Coefficient estimates for LPMs with an extended set of location controls. Specifications include all restaurant-level controls listed in Table 2, those coefficients are largely unchanged and omitted here. Standard errors clustered at the FE level.

| Dep. var.: restaurant closed |

||

|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | |

| City center dist. (km) | −0.004*** | −0.003*** |

| (0.0005) | (0.0004) | |

| City center dist. (km) | 0.00001*** | |

| (0.000002) | ||

| City center dist. (km) × City size (thsd km) | 0.002*** | |

| (0.0004) | ||

| Pop. dens. (thsd per km in CBG) | 0.001*** | |

| (0.0001) | ||

| Share of population below 25 | −0.048*** | |

| (0.010) | ||

| Est. nearby (100 s) | 0.011*** | 0.011*** |

| (0.002) | (0.002) | |

| City-Category FE | ✓ | ✓ |

| Rest. characteristics controls | ✓ | ✓ |

| Observations | 128,281 | 128,281 |

| R2 | 0.033 | 0.034 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.027 | 0.027 |

Note:; ; .

To compare the alternative models presented in Table 2, I also report the Average Partial Differences (APDs) corresponding to the variables of interest in Table 4. APDs describe the average change in the probability of restaurant closure conditional on a marginal increase in the respective variable (or a change from the baseline to the target value in case of a dummy variable). Formally, an Average Partial Difference is defined exactly as an Average Partial Effect (see Wooldridge (2010)), but substituting effect with difference since the estimates of this paper are meant to be purely descriptive.

Table 4.

Average Partial Differences for the binary response models. Standard errors clustered at the FE level in LPM specifications.

| Response: probability of restaurant closing |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

LPM |

Logit |

Probit |

||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| $ | −0.020* | −0.020*** | −0.014*** | −0.014*** | −0.017*** | −0.017*** |

| (0.017) | (0.005) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | |

| $$ | 0.012* | 0.012* | 0.027*** | 0.026*** | 0.023*** | 0.022*** |

| (0.011) | (0.006) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | |

| $$$ | 0.016* | 0.016* | 0.036*** | 0.037*** | 0.030*** | 0.031*** |

| (0.012) | (0.009) | (0.007) | (0.007) | (0.007) | (0.007) | |

| $$$$ | 0.002 | 0.003 | 0.018* | 0.021* | 0.014* | 0.016* |

| (0.014) | (0.014) | (0.013) | (0.013) | (0.013) | (0.013) | |

| Rating | −0.014** | −0.014*** | −0.012*** | −0.013*** | −0.012*** | −0.013*** |

| (0.005) | (0.002) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | |

| Reviews (100 s) | −0.009*** | −0.009*** | −0.018*** | −0.018*** | −0.015*** | −0.015*** |

| (0.001) | (0.000) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | |

| Est. nearby (100 s) | 0.012*** | 0.012*** | 0.009*** | 0.009*** | 0.010*** | 0.010*** |

| (0.003) | (0.002) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | |

| City center dist. (km) | −0.002*** | −0.002*** | −0.003*** | −0.003*** | −0.003*** | −0.003*** |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| # categories | −0.007* | −0.007*** | −0.004*** | −0.004*** | −0.005*** | −0.005*** |

| (0.005) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | |

| City FE | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Category FE | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| City-Category FE | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

Note:; ; .

The estimated APDs appear to be of similar magnitude in the LPM, logit and probit models. The change from the reference price category (missing) to the $-category is associated with a 1.4%–2% drop in the closure probability. In turn, the change from the baseline to $$ category is associated with a 1.2–2.7% increase in the probability of restaurant exit. A restaurant with an extra star of the rating score can be expected to have a 1.2–1.4% higher probability of survival. A restaurant with an additional cuisine category is observed to be 0.4–0.7% less likely to close. The APD associated with the review count (in 100s) is between and depending on the specification. A 100-increase in the number of nearby establishments is associated with a roughly 1% higher exit probability. Finally, a restaurant located 1 km further from the city center is expected to have a 0.2–0.3% lower closure probability.

4. Conclusion

This paper describes the restaurant exit patterns during 2020, the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. Using data from Yelp and SafeGraph, I determine the restaurant- and location-specific factors related to closure decisions.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

I thank the Editor, Joseph E. Harrington, and an anonymous reviewer for useful suggestions. I also thank Timur Abbiasov, Anna Algina, Gaston Illanes, Robert Porter and Mar Reguant for helpful discussions. Thanks to Jonathan Wolf and the SafeGraph team for access to data and thoughtful remarks. I am grateful to the Editor of Covid Economics, Charles Wyplosz, and an anonymous reviewer for their comments on an earlier version of this paper.

Footnotes

An earlier version of this paper has appeared in issue 82 of Covid Economics paper series. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

The initial set of restaurants was obtained from the SafeGraph database of points-of-interest and complemented with a search for “food” around a dense grid of points corresponding to Census Block Group centroids.

Yelp describes this field as indicating “whether business has been (permanently) closed”. While this indicator is likely an imperfect signal of a business shutdown, there are several reasons to believe it performed well during the period of interest. First, Yelp collects information from business owners, platform users and third-party providers to construct this indicator, allowing for several data check layers; by the time of my second data collection, the data quality from these sources has likely been restored relative to the initial pandemic disruption. Second, while it is hard to find another dataset to double-check closures on the restaurant level, the overall closure rate computed using Yelp (15.2%) is largely consistent with a survey by The National Restaurant Association (December 2020) (17%). Third, in October 2021, I recollected Yelp data for a random subsample (1000) of restaurants marked as permanently closed in early 2021. The vast majority (98.5%) of these restaurants were still marked as closed, confirming that the restaurant-closed field is indeed informative of permanent closure.

References

- Abbiasov, T., Sedov, D., 2021. Do Local Businesses Benefit from Sports Facilities? the Case of Major League Sports Stadiums and Arenas. Working Paper.

- Agarwal R., Audretsch D.B. Does entry size matter? The impact of the life cycle and technology on firm survival. J. Ind. Econ. 2001;49(1):21–43. [Google Scholar]

- Audretsch D.B., Houweling P., Thurik A.R. Firm survival in the netherlands. Rev. Ind. Org. 2000;16(1):1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Bartik A.W., Bertrand M., Cullen Z., Glaeser E.L., Luca M., Stanton C. The impact of COVID-19 on small business outcomes and expectations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2020;117(30):17656–17666. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2006991117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belitski M., Guenther C., Kritikos A.S., Thurik R. Economic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on entrepreneurship and small businesses. Small Bus. Econ. 2021:1–17. doi: 10.1007/s11187-021-00544-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caves R.E. Industrial organization and new findings on the turnover and mobility of firms. J. Econ. Lit. 1998;36(4):1947–1982. [Google Scholar]

- Crane L.D., Decker R.A., Flaaen A., Hamins-Puertolas A., Kurz C. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System; Washington: 2021. Business Exit During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Non-Traditional Measures in Historical Context: Finance and Economics Discussion Series 2020-089r1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fackler D., Schnabel C., Wagner J. Establishment exits in Germany: the role of size and age. Small Bus. Econ. 2013;41(3):683–700. [Google Scholar]

- Fairlie, R.W., 2020. The Impact of COVID-19 on Small Business Owners: Continued Losses and the Partial Rebound in May 2020. NBER Working Paper.

- Foster L., Haltiwanger J., Syverson C. Reallocation, firm turnover, and efficiency: Selection on productivity or profitability? Amer. Econ. Rev. 2008;98(1):394–425. doi: 10.1257/aer.98.1.394. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Geroski P.A. What do we know about entry? Int. J. Ind. Organ. 1995;13(4):421–440. [Google Scholar]

- Glaeser E.L., Jin G.Z., Leyden B.T., Luca M. Learning from deregulation: The asymmetric impact of lockdown and reopening on risky behavior during COVID-19. J. Reg. Sci. 2021;61(4):696–709. doi: 10.1111/jors.12539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goolsbee A., Syverson C. Fear, lockdown, and diversion: Comparing drivers of pandemic economic decline 2020. J. Public Econ. 2021;193 doi: 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koren M., Peto R. Business disruptions from social distancing. Covid Econ. 2020;1(2):13–31. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0239113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luca D.L., Luca M. National Bureau of Economic Research; 2019. Survival of the Fittest: The Impact of the Minimum Wage on Firm Exit: Working Paper Series, 25806. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Luo, T., Stark, P.B., 2014. Only the Bad Die Young: Restaurant Mortality in the Western US. Technical Report, arXiv:1410.8603.

- Manson S., Schroeder J., Van Riper D., Kugler T., Ruggles S. 2021. IPUMS national historical geographic information system: Version 16.0 [dataset]. Minneapolis, MN: IPUMS. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parsa H.G., Kreeger J.C., van der Rest J.-P., Xie L.K., Lamb J. Why restaurants fail? Part v: Role of economic factors, risk, density, location, cuisine, health code violations and GIS factors. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2021;22(2):142–167. [Google Scholar]

- Parsa H., Self J., Sydnor-Busso S., Yoon H.J. Why restaurants fail? Part II: The impact of affiliation, location, and size on restaurant failures: Results from a survival analysis. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2011;14(4):360–379. [Google Scholar]

- Sedov, D., 2021. How Efficient are Firm Location Configurations? empirical Evidence from the Food Service Industry. Working Paper.

- Sink V. The National Restaurant Association; 2020. Restaurant Industry in Free Fall; 10,000 Close in Three Months. Archived at https://web.archive.org/web/20211001065610/https://restaurant.org/news/pressroom/press-releases/restaurant-industry-in-free-fall-10000-close-in. (Accessed 10 January 2021) [Google Scholar]

- Wooldridge J. MIT Press; 2010. Econometric Analysis of Cross Section and Panel Data. [Google Scholar]