Abstract

Implementation of evidence-based interventions (EBIs) can help to increase colorectal cancer screening (CRCS). Potential users of CRCS EBIs are often unclear about the specific features, logic, and core elements of existing EBIs, making it challenging to use or adapt them. We used EBI Mapping, a systematic process developed from Intervention Mapping that identifies an EBI’s components and logic, to characterize existing CRCS EBIs from the National Cancer Institute’s Evidence-Based Cancer Control Programs website. The resulting information can facilitate intervention adoption, adaptation, and/or implementation. Two trained coders independently coded intervention materials to describe intervention components and logic (n = 20). We display CRCS EBI components (potential mechanism of change) using evidence tables and heat maps. All EBIs addressed completion of at least one CRCS behavior (stool-based test, n = 9; stool-based test or another CRCS test, n = 8; colonoscopy, n = 3; colonoscopy or sigmoidoscopy, n = 1). The psychosocial determinants most frequently addressed by these interventions were knowledge (n = 19), attitudes (n = 17), risk perception/perceived susceptibility (n = 16), skills (n = 15), and overcoming barriers (n = 15). Multi-level EBIs (n = 9) attempted to change an average of 2.1 ± 1.1 conditions in the patients’ environment (e.g., accessibility of CRCS); only four EBIs used environmental change agents (e.g., providers, nurses). From the heat maps of EBIs, we describe common theoretical change methods’ (e.g., facilitation) used for addressing determinants (e.g., overcoming barriers). EBI Mapping can help users identify important components of a CRCS EBI’s logic; these proposed mechanisms of action can inform adoption, adaptation, and implementation in new settings, and facilitate scale up of EBIs.

Keywords: Program planning, Implementation, Cancer, Colorectal, Intervention Mapping

Implications.

Practice: Practitioners should consider addressing patients’ knowledge, attitudes, risk perception/perceived susceptibility, skills, and ability to overcome barriers when designing or adapting colorectal cancer screening (CRCS) interventions.

Policy: Health care organizations may need to focus on using multi-level interventions that include organizational changes to improve CRCS, as half of effective CRCS interventions attempted to change an environmental condition.

Research: Evidence-Based Intervention Mapping can help researchers identify important components of a CRCS intervention’s logic to inform selection, adoption, adaptation, and implementation.

INTRODUCTION

Colorectal cancer is the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths among men and women combined in the United States (U.S.), accounting for an estimated 53,000 deaths annually [1]. Screening plays an essential role in reducing colorectal cancer mortality, as colorectal cancer is treatable if diagnosed at a localized stage [2–4]. Despite gradual increases in screening over the past decade, colorectal cancer screening (CRCS) rates remain well below the national recommendation of 80% in every community [5, 6]. CRCS rates are around 60% for individuals 50–75 years old but are substantially lower (24.8%) among economically vulnerable individuals, such as the medically uninsured [1, 5]. Increasing national CRCS rates to 80% has the potential to prevent approximately 200,000 deaths by 2030 [7].

An effective approach to increasing CRCS rates is through the delivery of evidence-based interventions (EBIs) that have been shown to increase screening. EBIs are programs, policies, and practices with proven efficacy and effectiveness that are developed for a specific population and setting (e.g., Flu-FIT intervention) [8–10]. Yet, a recent systematic review reported that two of the top five barriers that prevent community organizations from delivering EBIs include challenges adapting the EBI (41.9% of studies) and challenges understanding how to best implement the EBI (28.1% of studies) [11]. These are important hurdles for using EBIs in practice. Consequently, identifying innovative solutions that can improve adaptation and implementation processes may help community organizations improve the delivery of EBIs in practice.

Basing EBIs (interventions with specific components, materials, and protocols) on general evidence-based approaches (EBAs), such as those recommended by the Guide to Community Preventive Services, (e.g., provider reminders), may be one approach to improving their delivery [8–10]. EBAs are categories of interventions, usually defined by delivery mode, that have been found to be effective through systematic reviews of specific EBIs (e.g., client reminders) [8–10]. For example, Prevention Care Management, a specific “packaged” EBI, is an example of the use of client reminders, an EBA from the Community Guide, to improve CRCS in women over the age of 50 at their healthcare clinics [12, 13]. Other EBAs recommended for increasing CRCS by the Community Guide include multicomponent interventions, one-on-one education, small media interventions, and reducing structural barriers [12, 14, 15].

Resources such as the National Cancer Institute’s Evidence-Based Cancer Control Programs’ (EBCCP; formerly RTIPs) website are also designed to improve the use of CRCS EBIs by making intervention information and materials accessible and summarizing information about intervention features, including characteristics of the at-risk population, level of effectiveness, setting, goals, time, cost, and staff required to deliver the intervention [16–18]. This information can clarify the intent of the EBI, its practical characteristics, and evidence base, but the EBCCP website does not provide information about the mechanisms through which the EBIs operate. Specifically, EBCCP does not provide information on the behavioral determinants that the EBI addresses, or the theoretical change methods used to address the determinants (i.e., intervention mechanisms or functions), both of which are important for understanding the logic of the intervention (Table 1) [8, 19]. Although identifying the determinants and theoretical change methods helps users to understand the form and function of the EBI, they are not yet part of standard reporting within scientific manuscripts, and they can be difficult to identify within intervention materials [8, 19]. Nevertheless, determinants and theoretical change methods may be the intervention components responsible for the EBI’s effectiveness (i.e., potential core components); thus, they are important to identify before adopting or using an EBI [20].

Table 1.

Comparison of intervention characteristics provided by EBCCP and EBI Mapping

| EBCCP-provided intervention characteristic | Definition | What EBI Mapping adds | Definition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention setting | The location of the delivered intervention | Environmental change agents | People who can bring about change in the at-risk population’s interpersonal, organizational, policy, or societal environment |

| At-risk population | Population that has a health problem or is at risk for acquiring a health problem due to a behavior or environmental exposure | Implementers | Individuals who are directly or indirectly responsible for implementing EBI components |

| Health behavior (i.e., CRCS test) | An action or set of actions performed by the at-risk population that is expected to decrease the health problem or decrease complications or increase quality of life | At-risk population’s determinants | Factors that reside within the at-risk population that influence their behaviors |

| Health problem (i.e., colorectal cancer) | A deficit of health, excess of disease or risk factor for disease in a defined population | Environmental change agents’ determinants | Factors that reside within the environmental change agents that influence their behaviors |

| Community Guide EBAs | Proven strategies for promoting colorectal cancer screening | Specific theoretical change methods | Techniques or processes for influencing positive change in specific determinants of behaviors |

| Basic theoretical change methods | General technique or process for influencing positive change in multiple determinants or an environmental condition | ||

| Practical applications | A specific technique for the practical use of a theoretical change method used by an EBI | ||

| Environmental conditions | Factors in an individual’s social or physical environment (surroundings) that influence the health of the at-risk population or their behaviors |

From EBCCP website (https://ebccp.cancercontrol.cancer.gov).

CRCS colorectal cancer screening; EBAs evidence-based approaches; EBCCP Evidence-Based Cancer Control Programs; EBI evidence-based intervention.

EBI Mapping was developed and refined over multiple editions of the Intervention Mapping textbooks and work to produce IM-Adapt Online, a tool for intervention planners that assists in EBI adaptation [20, 21]. It also helps intervention planners to better understand EBIs more generally [16, 20, 22–24]. EBI Mapping, part of the IM Adapt process, can be useful any time practitioners are planning the implementation of an EBI (whether or not they will be adapting it) because it helps identify the who (i.e., the at-risk population), what (i.e., health behavior and health problem), why (i.e., behavioral determinants), and how (i.e., theoretical change methods and practical applications) of an EBI (definitions in Table 1). EBI Mapping also arranges intervention components into a logic model that can help planners to visualize the potential mechanisms through which the EBI operates; a tool that also makes it easier to share information with community partners [16, 20, 22–24]. Further, researchers can apply EBI Mapping to gain a better understanding of programmatic features and trends across multiple EBIs, such as frequently used theoretical change methods and behavioral determinants or links between them. From an implementation science standpoint, EBI Mapping provides intervention planner a better understanding of the specific features, logic, and core elements of existing interventions, a level of detail that is currently lacking in many intervention reports but can help improve the use of EBIs in practice. Summaries such as the one presented here provide information across CRCS EBIs that can inform future work related to adapting, adopting, and implementing EBIs for a particular health problem, as well as provide data that can generate recommendations for intervention planners and/or community partners.

To provide guidance to EBI users, our team used EBI Mapping to describe components of CRCS EBIs on the EBCCP website. We also identify patterns of determinants addressed across this set of EBIs and the theoretical change methods used to influence determinants. Finally, we describe how intervention planners can use components produced from EBI Mapping to help make decisions when adopting, adapting, and planning the implementation of EBIs.

METHODS

In the spring of 2019, we identified all CRCS EBIs on the EBCCP website (N = 21) and collected their available materials and primary manuscripts [18]. Materials often included journal publications, implementation manuals, standard operating procedures, participant handbooks, websites, worksheets, videos, flyers, and so forth. From the EBCCP website, we recorded some previously defined EBI characteristics, including the intervention setting, at-risk population, health behavior, health problem, and Community Guide EBAs (Table 1). Next, coders with training in Intervention Mapping used IM-Adapt Online, an online tool for adapting interventions, to describe the important components of EBIs not already listed on the EBCCP website [16, 24]. IM-Adapt (available at https://www.imadapt.org/#/) is divided into a series of steps that are guided by drop-down menus, built-in skip logic, helpful tips, and resource materials. In Step 3 of IM-Adapt, the sub-steps include (3a) describing the important components of an EBI and (3b) making adaptation decisions by comparing the determinants of the new population with the EBI. For this project, coders specifically used Step 3a, a process we named EBI Mapping, to code CRCS EBIs.

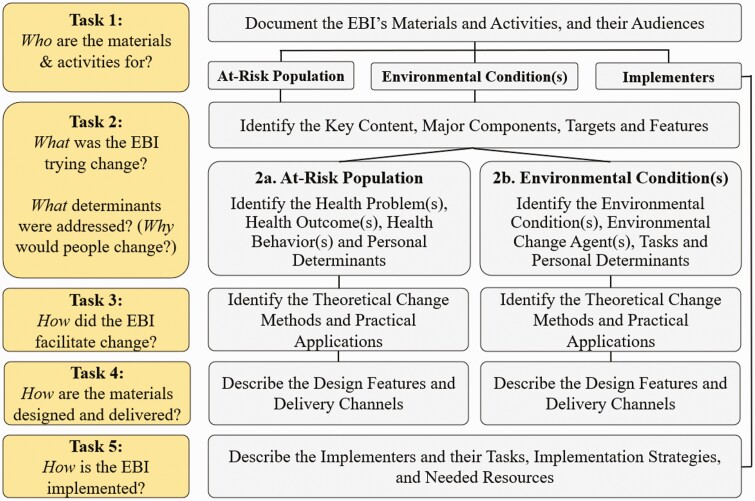

EBI Mapping comprises five tasks, including (a) documenting the EBI’s materials and activities, and their audiences (at-risk population and environmental change agents), (b) identifying the key content, major components, targets, and features of the EBI, (c) identifying the theoretical change methods and practical applications, (d) describing the design features and delivery channels, and (e) describing implementers, their tasks, and needed resources (Fig. 1). Tasks two through five are repeated for each at-risk population and environmental change agent (e.g., providers who recommend a CRCS test) included in a multi-level EBI (detailed methods are currently under review in Walker et al., EBI Mapping: A Systematic Approach to Map EBI Components and Logic).

Fig 1.

EBI Mapping tasks.

Two coders independently used EBI Mapping on an initial set of five EBIs and took notes on challenges and discrepancies discovered in the coding process. Coders met after coding each of the five interventions to resolve discrepancies through discussion to consensus and made notes to help inform agreement for future coding. Coders also met weekly with the larger research team to discuss coding challenges, which resulted in refinements to the coding process and the development of a coding workbook that provides additional guidance (https://sph.uth.edu/research/centers/chppr/research/ebi-mapping/index#sph.uth.edu). After coding the initial five EBIs, the coders independently extracted information from the remaining 15 EBIs. They continued to meet with the research team weekly and with one another as needed.

Synthesis

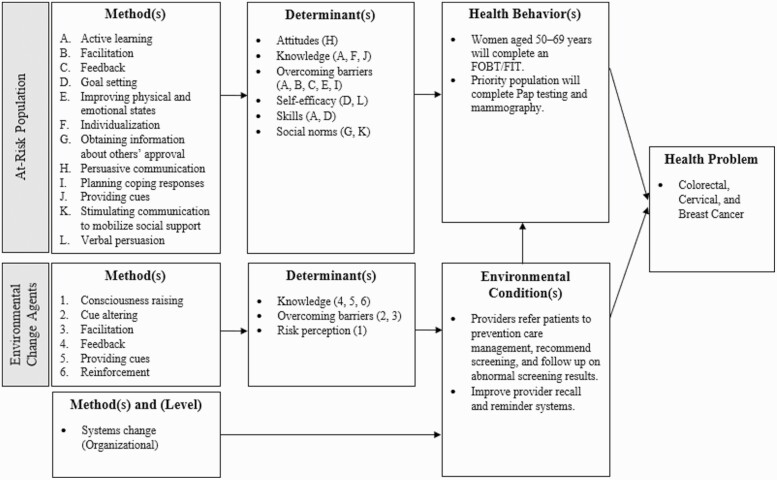

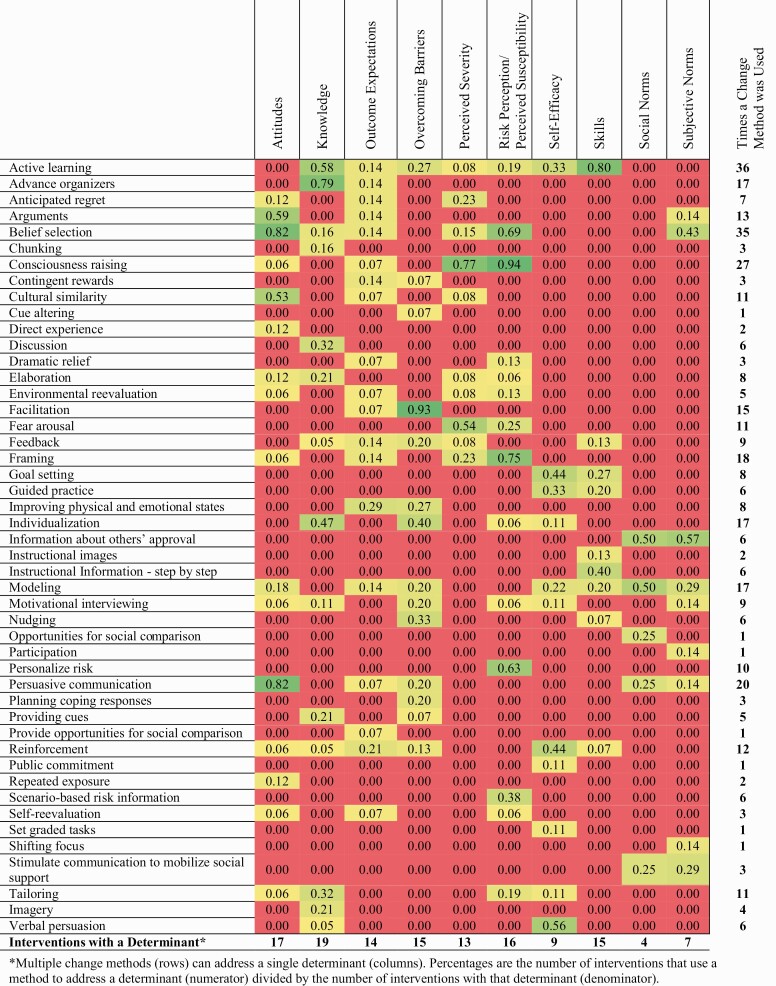

We created an evidence table to summarize the information extracted from the EBCCP website and the EBI Mapping process, as well as provide a brief overview of each CRCS intervention (Table 2). The components added through the EBI Mapping process include environmental conditions, determinants for the at-risk population and environmental change agents, and theoretical change methods and practical applications used to change those determinants for the at-risk population and environmental change agent(s). For EBIs that addressed an environmental condition, we also described their ecologic level (i.e., interpersonal, organizational, community, societal) and the theoretical change methods used to create change at each level. Theoretical change methods take two forms: (a) basic change methods, which address an environmental condition or multiple determinants of the at-risk population, and (b) specific methods, which create change by influencing specific determinants of the at-risk population or environmental change agents. For a single EBI, we display components in a logic model (Fig. 2), which is a useful way for sharing information about an EBI with community partners. We also created two heat maps—one at the level of the at-risk population (Fig. 3) and one at the level of the environmental change agents (Appendix Fig. A1)—which sum the number of times determinants and theoretical change methods were used across EBIs and display the proportion of interventions that use a theoretical change method to address a determinant (numerator) divided by the number of interventions with that determinant (denominator). Heat maps such as this can also be useful for generating information about common practices within a specific category of EBIs (i.e., CRCS).

Table 2.

Setting, at-risk population, environmental change agents, environmental conditions, determinants, methods, health behaviors, and Community Guide EBAs for interventions

| Intervention/setting | At-risk population, environmental change agents/conditions, and desired behaviors | Determinant | Methods | Community Guide EBAs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interventions that address the at-risk population only | ||||

| CRCS in Chinese Americans project Community primary care clinics with access to a bilingual health educator |

Lower-income, less-acculturated Chinese immigrants, aged 50–78 years; no FOBT <1 year; no colonoscopy <10 years; will complete an FOBT/FIT | Attitudes | Anticipated regret, belief selection, cultural similarity, direct experience, persuasive communication, repeated exposure, self-reevaluation | Small media |

| Knowledge | Active learning, advance organizers, discussion, individualization | |||

| Outcome expectations | Arguments, dramatic relief, environmental reevaluation, improving physical and emotional states, self-reevaluation | |||

| Overcoming barriers | Facilitation, modeling, nudging, persuasive communication, planning coping responses | |||

| Perceived severity | Belief selection, consciousness raising, cultural similarity, elaboration | |||

| Risk perception/perceived susceptibility | Belief selection, consciousness raising, fear arousal, framing, personalize risk, scenario-based risk information | |||

| Skills | Instructional information step by step, modeling, nudging | |||

| Social norms | Modeling, opportunities for social comparison | |||

| Subjective norms | Information about others’ approval, modeling | |||

| Mailed reminder to increase completion of fecal occult blood testing Primary care setting and in the patient’s home |

U.S. veterans aged >50 years who are not currently receiving inpatient care will complete an FOBT | Attitudes | Consciousness raising, cultural similarity | Client reminders |

| Knowledge | Advance organizers, reinforcement, imagery | |||

| Outcome expectations | Belief selection, framing, persuasive communication | |||

| Perceived severity | Consciousness raising, fear arousal | |||

| Risk perception/perceived susceptibility | Belief selection, consciousness raising, framing | |||

| Social norms | Information about others’ approval, modeling | |||

| Effect of a mailed brochure on appointment keeping for screening colonoscopy Ambulatory primary care practices, clinic |

Asymptomatic men and women aged ≥50 years who receive a provider referral will complete a colonoscopy | Knowledge | Advance organizers, individualization, tailoring |

Multicomponent

Small media Client reminder |

| Outcome expectations | Consciousness raising, feedback, framing | |||

| Perceived severity | Consciousness raising, fear arousal, feedback, framing | |||

| Risk perception/perceived susceptibility | Belief selection, consciousness raising, fear arousal, framing, personalize risk, scenario-based risk information, tailoring | |||

| Skills | Active learning | |||

| Social norms | Persuasive communication | |||

| Subjective norms | Arguments, persuasive communication | |||

| Family care (colorectal cancer awareness and risk education) project Community and clinical settings |

Adults with a family history of CRC (i.e., first-degree relative diagnosed with CRC before age 60, or first-degree relative diagnosed at age ≥60 years and additional first- or second-degree relative diagnosed at any age, will complete a colonoscopy | Attitudes | Arguments, belief selection, cultural similarity, modeling |

Multicomponent

One-on-one education Client reminder |

| Knowledge | Active learning, advance organizers, elaboration, individualization, motivational interviewing, tailoring, using imagery | |||

| Outcome expectations | Contingent rewards, improving physical and emotional states, modeling | |||

| Overcoming barriers | Contingent rewards, facilitation, nudging, planning coping responses, reinforcement | |||

| Perceived severity | Anticipated regret, consciousness raising, environmental reevaluation | |||

| Risk perception/perceived susceptibility | Active learning, belief selection, consciousness raising, framing, personalize risk, scenario-based risk information, tailoring | |||

| Self-efficacy | Goal setting, individualization, reinforcement, set graded tasks, tailoring, verbal persuasion | |||

| The colorectal health project Community healthcare clinics |

Hispanic adults aged 50–79 years who have not had a recent colorectal screening exam will complete an FOBT | Attitudes | Arguments, belief selection, cultural similarity, persuasive communication, reinforcement |

Multicomponent

Small media One-on-one education Client reminder |

| Knowledge | Active learning, advance organizers, belief selection, elaboration, individualization, providing cues, tailoring | |||

| Outcome expectations | Belief selection, reinforcement | |||

| Overcoming barriers | Facilitation, improving physical and emotional states, nudging | |||

| Perceived severity | Anticipated regret, consciousness raising | |||

| Risk perception/perceived susceptibility | Active learning, belief selection, consciousness raising, environmental reevaluation, framing, individualization, motivational interviewing, personalize risk, self-reevaluation, tailoring | |||

| Skills | Feedback, reinforcement | |||

| Subjective norms | Belief selection, information about others’ approval | |||

| Culturally tailored navigator intervention program for CRCS Urban community health centers and gastroenterology departments |

Adults aged 52–79 years with low income and low proficiency in English will complete a colonoscopy. | Attitudes | Arguments, belief selection, persuasive communication | Reducing structural barriers for clients |

| Knowledge | Active learning, advance organizers, discussion, tailoring | |||

| Outcome expectations | Active learning, reinforcement | |||

| Overcoming barriers | Facilitation, improving physical and emotional states, individualization | |||

| Perceived severity | Active learning, consciousness raising | |||

| Skills | Active learning, instructional information | |||

| Subjective norms | Belief selection, shifting focus | |||

| Colorectal cancer education, screening, and prevention program Healthcare providers with an electronic health records system |

Adults aged 50–75 years will complete an FOBT/FIT, sigmoidoscopy, or colonoscopy | Attitudes | Arguments, belief selection, persuasive communication | Group educationa |

| Knowledge | Active learning, advance organizers, discussion | |||

| Outcome expectations | Active learning, improving physical and emotional states, reinforcement | |||

| Overcoming barriers | Active learning, facilitation, feedback, individualization, nudging | |||

| Perceived severity | Fear arousal | |||

| Risk perception/perceived susceptibility | Belief selection, consciousness raising | |||

| Skills | Active learning, goal setting | |||

| FIT and colonoscopy outreach Primary care setting within urban communities |

Racially diverse and socioeconomically disadvantaged adults aged 50–64 years will complete an FOBT/FIT or colonoscopy. | Attitudes | Arguments, belief selection, persuasive communication | Small media Client reminder |

| Knowledge | Advance organizers, individualization, tailoring, using imagery | |||

| Overcoming barriers | Facilitation | |||

| Risk perception/perceived susceptibility | Belief selection, consciousness raising, framing, personalize risk | |||

| Self-efficacy | Reinforcement | |||

| Skills | Active learning, instructional information | |||

| Automated telephone call improve completion of FOBT Clinical and group-model health maintenance organization setting |

Adults (51–80 years old) at average risk for colorectal cancer and due for routine screening will complete an FOBT/FIT | Attitudes | Arguments, belief selection, environmental reevaluation, persuasive communication | Client reminder |

| Knowledge | Chunking, providing cues, using imagery | |||

| Overcoming barriers | Facilitation | |||

| Perceived severity | Consciousness raising, fear arousal, framing | |||

| Risk perception/perceived susceptibility | Belief selection, consciousness raising, dramatic relief, framing | |||

| Skills | Active learning, instructional images | |||

| Colorectal cancer screening intervention program Participants in senior centers, churches, community centers, and public health clinics |

African American adults aged ≥49 years will complete an FOBT, colonoscopy, sigmoidoscopy, double-contrast barium enema, or digital rectal exam. Program also includes reduction of risky drinking, smoking/tobacco cessation, and increasing physical activity | Attitudes | Belief selection, cultural similarity, modeling, motivational interviewing, persuasive communication | Group educationa |

| Knowledge | Chunking, discussion, elaboration | |||

| Outcome expectations | Advance organizers, feedback | |||

| Risk perception/perceived susceptibility | Belief selection, elaboration, framing | |||

| Self-efficacy | Goal setting, motivational interviewing, verbal persuasion | |||

| Skills | Active learning, goal setting | |||

| Subjective norms | Information about others’ approval, modeling, motivational interviewing, stimulate communication to mobilize social support | |||

| Healthy colon, healthy life Primary care clinics with a high proportion Latino and/or Vietnamese patients that can collaborate with a community-based organization |

Vietnamese and Hispanic or Latino adults aged ≥40 years will complete an FOBT/FIT, colonoscopy, or sigmoidoscopy | Attitudes | Belief selection, cultural similarity, elaboration, persuasive communication |

Multicomponent

Small media One-on-one education |

| Knowledge | Active learning, advance organizers, individualization, motivational interviewing | |||

| Overcoming barriers | Facilitation, individualization, motivational interviewing | |||

| Risk perceptions/perceived susceptibility | Consciousness raising | |||

| Interventions that address both an at-risk population and an environmental condition | ||||

| Filipino-American health study Community-based orgs and churches that serve Filipino-Americans |

Filipino-Americans aged 50–70 years with no CRCS within guidelines will complete an FOBT | Attitudes | Cultural similarity, direct experience, tailoring |

Multicomponent

Small media Client reminder Group education |

| Knowledge | Advance organizers, discussion | |||

| Outcome expectations | Advance organizers, cultural similarity, provide opportunities for social comparison | |||

| Overcoming barriers | Active learning, modeling, persuasive communication | |||

| Perceived severity | Consciousness raising, fear arousal, framing | |||

| Risk perception/perceived susceptibility | Active learning, consciousness raising, fear arousal, framing, personalize risk | |||

| Self-efficacy | Active learning, goal setting, public commitment, reinforcement | |||

| Skills | Active learning, goal setting, instructional (step-by-step) information, modeling | |||

| Subjective norms | Participation, stimulate communication to mobilize social support | |||

| Environmental condition (level) | Basic change methods | |||

| Increased patient accessibility to CRCS. (Organizational) | Systems change | |||

| Kukui Ahi (light the way) patient navigation Community healthcare clinics in rural settings |

Asian and Pacific Islander adults enrolled in Medicare will complete an FOBT/FIT, sigmoidoscopy, or colonoscopy. Program also includes Pap testing, mammography, and prostate cancer: informed decision. | Knowledge | Active learning, tailoring |

Multicomponent

Group education Client reminder Reducing structural barriers for clients |

| Overcoming barriers | Facilitation, individualization, providing cues | |||

| Environmental conditions (level) | Basic change methods | |||

| Improve continuity of care for patients by enhancing communication between patient navigators and providers. (Interpersonal) | Enhancing network linkages, systems change | |||

| Develop volunteer patient recruiters within community organizations. (Community) | Developing a new social network linkage | |||

| New Hampshire CRCS program Home and clinical settings in rural, suburban, and urban communities |

Men and women aged 50–64 years who are low-income (<250% of federal poverty level), uninsured, and/or underinsured patients in New Hampshire will complete a colonoscopy | Attitudes | Arguments, belief selection, elaboration, persuasive communication, repeated exposure |

Multicomponent

Small media One-on-one education Reduce structural barriers for clients |

| Knowledge | Active learning, advance organizers, individualization | |||

| Outcome expectations | Modeling | |||

| Overcoming barriers | Facilitation, improving physical and emotional states, motivational interviewing | |||

| Risk perception/perceived susceptibility | Belief selection, consciousness raising, personalize risk | |||

| Self-efficacy | Active learning, guided practice, reinforcement | |||

| Skills | Active learning, guided practice, modeling | |||

| Environmental conditions (level) | Basic change methods | |||

| Improve patient’s continuity of care by enhancing patient navigator-endoscopist communication. (Interpersonal) | Enhancing network linkages, systems change | |||

| Increase provider referral for endoscopy. (Organizational) | Systems change | |||

| Organizations partner to provide free colonoscopy screening for low-income, uninsured or underinsured individuals. (Organizational) | Forming coalitions | |||

| Smart options for screening Healthcare providers with an electronic health records system |

Adults aged 51–80 years at average risk for colorectal cancer and due for routine screening will complete an FOBT, sigmoidoscopy, or colonoscopy |

Attitudes | Arguments, belief selection, persuasive communication |

Multicomponent

Small media One-on-one education Client reminder Reduce structural barriers for clients |

| Knowledge | Advance organizers, belief selection | |||

| Outcome expectations | Contingent rewards, improving physical and emotional states | |||

| Overcoming barriers | Active learning, facilitation, feedback, individualization, nudging, reinforcement | |||

| Perceived severity | Fear arousal | |||

| Risk perception/perceived susceptibility | Consciousness raising, environmental reevaluation, personalize risk, scenario-based risk information | |||

| Skills | Active learning, guided practice | |||

| Environmental conditions (level) | Basic change methods | |||

| Improve patient’s continuity of care for by enhancing nurse-provider communication. (Interpersonal) | Enhancing network linkages, systems change | |||

| Prevention care management Clinical, urban/inner city |

Women aged 50–69 years will complete an FOBT/FIT. Program also includes Pap testing and mammography |

Attitudes | Persuasive communication | Client reminder |

| Knowledge | Active learning, individualization, providing cues | |||

| Overcoming barriers | Active learning, facilitation, feedback, improving physical and emotional states, planning coping responses | |||

| Self-efficacy | Goal setting, verbal persuasion | |||

| Skills | Active learning, goal setting | |||

| Social norms | Information about others’ approval, stimulate communication to mobilize social support | |||

| Providers will refer patients to prevention care management, recommend screening, and follow up on abnormal screening results. | Knowledge | Feedback, providing cues, reinforcement | ||

| Overcoming barriers | Cue altering, facilitation | |||

| Risk perception | Consciousness raising | |||

| Environmental conditions (level) | Basic change methods | |||

| Improve provider recall and reminder systems. (Organizational) | Systems change | |||

| Targeting cancer in African Americans Public health clinics, barber shops, hair salons, churches, and religious organizations within African American communities |

African American adults aged 18 years and older will complete an FOB/FIT, colonoscopy, or prostate cancer and Pap testing. Program also includes mammography, smoking/tobacco cessation, healthy nutrition, and physical activity | Attitudes | Arguments, belief selection, persuasive communication |

Multicomponent

Small media Group education Mass media |

| Knowledge | Active learning, advance organizers | |||

| Outcome expectations | Arguments, facilitation | |||

| Perceived severity | Consciousness raising, fear arousal | |||

| Risk perceptions/perceived susceptibility | Consciousness raising, framing, personalize risk | |||

| Self-efficacy | Active learning | |||

| Skills | Active learning, feedback, instructional information | |||

| Co-change agents (i.e., community members who have committed to helping deliver the program) host or deliver education programs, distribute educational materials, and make community referrals. | Attitudes | Persuasive communication | ||

| Knowledge | Active learning, discussion | |||

| Social norms | Belief selection, stimulate communication to mobilize social support | |||

| Environmental conditions (level) | Basic change methods | |||

| Increase awareness of cancer prevention resources and support for cancer screening in the community. (Community) | Developing new social network linkages, enhancing network linkages, forming coalitions, mass media role-modeling, mobilizing social networks, peer education, systems change | |||

| Flu-FIT and flu-FOBT program Community health centers, pharmacies, managed care organizations, and other healthcare settings that provide flu shots and offer fit/FOBT |

Adults aged 50–75 years who are due for CRCS and receive annual flu shots during primary care visits or at drop-in flu shot clinics will complete an FOBT/FIT | Attitudes | Arguments, belief selection, cultural similarity, framing, modeling, persuasive communication |

Multicomponent

Small media One-on-one education |

| Knowledge | Advance organizers, belief selection, verbal persuasion | |||

| Outcome expectations | Anticipated regret | |||

| Overcoming barriers | Cue altering, facilitation, individualization, persuasive communication | |||

| Perceived severity | Consciousness raising | |||

| Risk perception/perceived susceptibility | Consciousness raising, framing, personalized risk, scenario-based risk information | |||

| Self-efficacy | Guided practice, modeling, verbal persuasion | |||

| Skills | Active learning, guided practice | |||

| Environmental conditions (level) | Basic change methods | |||

| Increased awareness of FOBT availability. (Organizational) | Structural redesign, systems change | |||

| Improve provider recall and reminder systems. (Organizational) | Systems change, technical assistance | |||

| Reduction of logistical barriers for returning FOBT test. (organization) | Systems change | |||

| Against CRC in our neighborhoods Clinic (serving the uninsured) and community settings (e.g., churches, health fairs, food pantries, low-income housing complexes, community centers). |

Uninsured Hispanic adults aged 50–75 years who are due for CRCS will complete an FOBT or colonoscopy. | Attitudes | Anticipated regret, belief selection, cultural similarity, persuasive communication |

Multicomponent

Client reminder Reduce structural barriers for clients Group education |

| Knowledge | Active learning, advance organizers, chunking, discussion, elaboration, feedback, individualization, providing cues | |||

| Outcome expectations | Anticipated regret | |||

| Overcoming barriers | Facilitation, modeling, motivational interviewing | |||

| Perceived severity | Anticipated regret, belief selection | |||

| Risk perception/perceived susceptibility | Belief selection, consciousness raising, dramatic relief, fear arousal, framing, scenario-based risk information | |||

| Self-efficacy | Guided practice, modeling, verbal persuasion | |||

| Skills | Instructional images, step-by-step instructions | |||

| Subjective norms | Belief selection, information about others’ approval | |||

| Promotora/community health workers will develop an action plan, compile a community resource list, and identify community partners to disseminate CRC education program. | Habits | Public commitment | ||

| Knowledge | Active learning, discussion | |||

| Overcoming barriers | Active learning, participation | |||

| Self-efficacy | Set graded tasks | |||

| Environmental conditions (level) | Basic change methods | |||

| Improve patient’s continuity of care for by enhancing navigator-provider communication. (Interpersonal) | Developing a new social network linkage, enhancing network linkages | |||

| Increase the network of organizations promoting CRC education and providing resources for CRC. (Community) | Community assessment, use of lay health workers | |||

| Decease logistical and remove cost barriers for CRCS. (Community) | Forming coalitions, systems change | |||

| Increase the number of CRC positive patients with access to treatment. (Community) | Community assessment, forming coalitions | |||

| Interventions that address an environmental condition only | ||||

| Physician-oriented intervention on follow-up in colorectal cancer screening Clinic or primary care office |

Providers will perform complete diagnostic evaluation (CDE) for FOBT+ patients, attend academic visits, review CDE reminders, recommend eligible patients to get CDE, and spot abnormal FOBT results (past 60 days). | Knowledge | Active learning, discussion, elaboration, feedback | One-on-one education Client reminder |

| Overcoming barriers | Discussion, facilitation, nudging, tailoring | |||

| Environmental conditions (level) | Basic change methods | |||

| Providers who do not perform CDE screenings for FOBT+ patients; physician provides thorough CDE among patients with FOBT+ result. (Organizational) | Problem-posing education, structural redesign, systems change, technical assistance |

CRCS colorectal cancer screening; EBAs evidence-based approaches; EBCCP Evidence-Based Cancer Control Programs; EBI evidence-based intervention; FIT fecal immunochemical test; FOBT fecal occult blood test.

aGroup education has insufficient evidence as a community guide strategy when used alone.

Fig 2.

Logical model of core components from the Prevention Care Management EBI [12, 24]. Letters and numbers link methods to determinants.

Fig 3.

Heat map of theoretical change methods used to address the determinants of at-risk populations.

RESULTS

Overview

The EBCCP website contained 21 CRCS EBIs, 20 of which had available materials and were published in peer-reviewed journals from 2004 to 2017 (Table 2). Most EBIs (n = 16) focused on CRCS alone, and the remainder included at least one other cancer screening or cancer risk behavior (e.g., physical activity). About half (n = 11) addressed the at-risk population’s behaviors alone, one addressed an environmental condition alone, and the remaining (n = 8) multi-level EBIs addressed both the at-risk population’s behaviors and environmental conditions. One third (n = 8) of the EBIs aimed to increase use of a stool-based test (i.e., fecal immunochemical test [FIT] and/or fecal occult blood test [FOBT]); three, a colonoscopy; one, a colonoscopy/sigmoidoscopy; and eight included both a stool-based test and another CRCS test.

General EBAs recommended by the Community Guide that corresponded with the specific EBIs we reviewed were client reminders (n = 12) and multi-component interventions (n = 11). Although group education was used as part of a multi-component intervention (n = 4), two interventions used this general EBA alone, an application that was not recommended in the 2009 Community Guide review.

At-risk population (N =19)

The at-risk populations were defined as individuals 50 years and over, with some specified as women (n = 1), low socioeconomic status (n = 6), having a specific race/ethnicity (Asian or Pacific Islander, n = 4; Hispanic, n = 3; African American, n = 2), or other population-specific criterion (e.g., U.S. Veteran). The determinants most frequently addressed included knowledge of colorectal cancer and CRCS (n = 19), followed by attitudes (n = 17), risk perception/perceived susceptibility (n = 16), skills (n = 15), and overcoming barriers (n = 15), with self-efficacy (n = 9), subjective norms (n = 7), and social norms (n = 7) addressed less often. Theoretical change methods often used to address these determinants included belief selection and persuasive communication for attitudes, advanced organizers for knowledge, consciousness raising and framing for risk perception/perceived susceptibility, active learning for skills, and facilitation for overcoming barriers (Fig. 3). Some theoretical change methods addressed multiple determinants (e.g., active learning, modeling, reinforcement, motivational interviewing, belief selection, and feedback), whereas other EBIs used other theoretical change methods (e.g., public commitment, repeated exposure, scenario-based risk information) to address a single determinant only. Definitions of specific determinants and theoretical change methods can be found at https://www.imadapt.org/#/.

Environmental conditions (N = 9)

The EBIs that included environmental conditions frequently addressed more than one condition (averaging 2.1 ± 1.1 [range: 1–4]). Four EBIs focused on increasing patient accessibility to CRCS by reducing cost and logistical barriers or by connecting people with organizations that could provide screening. Four EBIs focused on improving patients’ continuity of care using patient navigators. Four EBIs aimed to increase provider referral and/or reminder systems for CRCS. Three EBIs focused on increasing the number of individuals and organizations in the community that link people to CRCS or provide CRCS to patients. One EBI attempted to increase awareness of an EBI by linking it to another annual procedure (i.e., flu shot).

Just over half of the EBIs addressed the environmental conditions through theoretical change methods that aimed to influence the environmental condition directly (n = 5) as opposed to through environmental change agents (n = 4). Environmental change agents included in the EBIs were providers (n = 2), community health workers (n = 1), and community members (n = 1). More than one EBI focused on providing knowledge (n = 4), overcoming barriers (n = 3), and changing attitudes (n = 2) to influence environmental change agent’s determinants, which they addressed through a variety of theoretical change methods (Appendix Fig. A1). For EBIs that focused on directly changing environmental conditions (i.e., not through an environmental change agent), commonly used theoretical change methods included systems change (n = 9), enhancing network linkages (n = 5), developing a new social network linkage (n = 3), and forming coalitions (n = 3).

Example applications

We provide three examples of how an intervention planner can use theoretical change methods and determinants to adopt, adapt, and implement EBIs.

Adoption

When conducting a needs assessment, an intervention planner may, for example, identify skills and social norms as important determinants of their at-risk population’s CRCS behaviors. Finding that these determinants are included in only three EBIs on EBCCP, the intervention planner has provisionally narrowed 20 interventions to three. Next, he or she can make an adoption decision based on the resources, staff engagement, and other needs of their organization. For example, only one EBI—Prevention Care Management—includes components directed at environmental change agents (i.e., providers) [13, 25]. The two other EBIs use small media to change the at-risk population’s behavior, but only one of the two EBIs—Mailed Brochure on Appointment Keeping for Screening Colonoscopy—uses small media plus a client reminder [26, 27]. These differences in EBI characteristics, described on the EBCCP website and identified through EBI Mapping, provide information to help intervention planners make adoption decisions. If, however, no EBIs address important determinants (e.g., skills and social norms) the user can plan adaptations and add messages or strategies to address these; thus, adapting an otherwise suitable EBI such as in the example below.

Adaptation

The Kukui Ahi Patient Navigation intervention’s at-risk population is Asian and Pacific Islander adults enrolled in Medicare [28, 29]. We found that this EBI addresses knowledge and overcoming barriers as important behavioral determinants. Thus, if knowledge and overcoming barriers are determinants that are highly relevant to an intervention planner’s at-risk population, then they may choose to use Kukui Ahi and adapt it to their population’s culture. We note, however, that a more detailed examination of intervention logic is needed to ensure that Kukui Ahi is the right intervention to adapt for the new population and setting (i.e., the same type of knowledge and barriers).

Implementation

The heat map identifies several theoretical change methods that intervention planners can use to address determinants. For example, virtually all the EBIs that address overcoming barriers include facilitation (i.e., reducing a barrier to action) as a theoretical change method. Similarly, EBIs that address perceived susceptibility include consciousness raising (i.e., providing information about the causes, consequences, or alternative for a problem behavior) as a theoretical change method. Consequently, it may be useful for intervention planners to design implementation strategies that emphasize the importance of using specific theoretical change methods to address a determinant. Further, fidelity checklists that evaluate the use of theoretical change methods for addressing determinants may also be helpful in process evaluation to assess implementation outcomes.

DISCUSSION

This study used EBI Mapping to highlight intervention components of CRCS EBIs on EBCCP, including behavioral determinants, environmental conditions, environmental change agents, and theoretical change methods used to change determinants and environmental conditions [20]. Gaining a better understanding of the details of EBIs enables us to better articulate not only the various components and content of the interventions but also the mechanisms through which interventions operate. After we consider the strength of evidence and the setting of an EBI, the additional core components that we identified in this study, which include potential mechanisms of action, provide additional criteria that users may find helpful when adopting, adapting, and implementing their interventions.

It is important to note that the inclusion of specific component(s) within an intervention, however, does not necessarily suggest that those components are responsible for creating an intervention’s effect. Nevertheless, identifying these components and articulating how (the potential mechanism) they are hypothesized to work is a necessary step in designing research that can begin to evaluate how given components affect intervention outcomes. When developing and reporting on an intervention, researchers should use systematic approaches and intervention logic models, such those provided by Intervention Mapping, that identify components of interventions and specify (a priori) how the components influence (individually or synergistically) the overall intervention effect on outcomes. Further, some study designs, such as Multiphase Optimization Strategy, step-wedge, or factorial designs, that add and/or remove specific components at different periods within a trial, can test their contribution to an intervention’s effect [30].

Across the CRCS interventions we analyzed, the most common behavioral determinants addressed in the at-risk population were knowledge, attitudes, risk perceptions/perceived susceptibility, skills, and overcoming barriers. A previous review that examined the use of three behavioral theories for improving CRCS found that determinants from the health belief model, including benefits (i.e., outcome expectations), perceived barriers, and perceived susceptibility were most commonly used to change CRCS behaviors [31]. Our analyses indicate that existing EBIs also commonly address attitudes, knowledge, and skills, especially related to tests for fecal occult blood in the stool (FIT and FOBT). Future studies should measure and evaluate these determinants to identify for which CRCS behaviors, and under what conditions, these determinants are important. Further, testing which theoretical change methods and practical applications most effectively influence these determinants can help to improve the quality and effectiveness of CRCS interventions.

In our analyses, the following theoretical change methods (potential mechanisms) were identified: active learning, belief selection (i.e., using messages to strengthen, weaken, or change beliefs), feedback, modeling, motivational interviewing, and reinforcement, were associated with five or more determinants of at-risk populations across EBIs. Intervention Mapping classifies all these methods as basic theoretical change methods (i.e., methods that address multiple determinants of the at-risk population) [20]. Similarly, EBIs used some specific theoretical change methods to address a specific determinant (e.g., discussion for changing knowledge). It is encouraging to see that interventions with evidence for their effectiveness have findings consistent with behavioral theory and that EBI developers are using these two types of methods appropriately in their development process.

Of the nine interventions that included environmental conditions, all used theoretical change methods that address the environmental condition directly, whereas only four interventions addressed environmental conditions by attempting to influence the determinants of environmental change agents. These findings may be a result of EBIs’ underspecifying determinants and theoretical change methods for environmental change agents who also serve a dual role as an intervention implementer. For example, in the Smart Options for Screening intervention, registered nurses were responsible, as intervention implementers, for making patient navigation phone calls, providing patient education, and identifying resources for patients [32]. The same EBI also addressed the continuity of care between nurses and providers as an environmental condition, but did not provide enough detail to list nurses as environmental change agents and did not specify the determinants and theoretical change methods used to address nurses’ behaviors. Consequently, we describe theoretical change methods used to address the environmental conditions directly, but determinants and theoretical change methods for addressing the nurses’ behaviors are lacking. For intervention adaptation, translation, and sustainability, it is important to document environmental changes that include intervention implementers; identification of the determinants and theoretical change methods used to improve nurse-provider coordination can improve study transparency and may be important for future efforts to deliver this EBI in another setting.

LIMITATIONS AND STRENGTHS

This study did not systematically identify all CRCS EBIs in the literature and, instead, relied on EBCCP to identify them. By specifically using EBCCP, we could ensure that intervention materials would be available and interventions would be evidence-based, which are two requirements of EBI Mapping. Although this EBI selection process was ideal for using EBI Mapping, these EBIs may not be representative of the CRCS literature. EBI Mapping users should reach out to intervention developers to obtain materials before undertaking an EBI Mapping project.

Identifying EBI components can be challenging, even with detailed implementation guides, intervention materials, and publications. While the EBI Mapping process makes this easier, those unfamiliar with Intervention Mapping may find it difficult to translate each individual intervention developer’s nomenclature to the EBI Mapping taxonomy. Specifically, details such as behavioral determinants and the theoretical change methods used to change those determinants may be difficult to determine. To improve the coding process, we used an existing online resource, developed a supplemental workbook with additional resources, and provided coders with multiple tools that are now publicly available (https://sph.uth.edu/research/centers/chppr/research/ebi-mapping/index#sph.uth.edu). For example, the workbook and online tool provide partial logic models that can help users to summarize their results after each coding task and combines these partial logic models to form a full logic model of the EBI. To improve coding consistency, we also recommend coding constructs only when the language is explicit and linked to CRCS. By taking this approach, we increased confidence in the reliability of our findings. To obtain a more complete understanding of EBIs, however, the development and use of reporting guidelines for manuscripts and intervention materials, as they relate to specifying intervention mechanisms including articulating theoretical change methods and determinants, is recommended. This type of reporting will help EBI users to better identify the form and function of the interventions, as well as potential mechanisms of action [19].

When using the EBI Mapping process, it is important to engage the local community and intervention planners in the process. EBI Mapping provides extensive detail on the logic of an intervention; however, community organizations who are adopting, adapting, or implementing CRCS interventions have implicit knowledge and experience that is highly relevant to adaptation and implementation decision-making. The concepts that are made clearer through the EBI Mapping process can be described to community partners in a more straightforward way. In doing so, EBI Mapping can help intervention planners to benefit from the knowledge and experience of their community partners.

A strength of this research is that we used a publicly available website (https://sph.uth.edu/research/centers/chppr/research/ebi-mapping/index#sph.uth.edu) combined with a systematic approach to identify the potential core components of each EBI. We also had two trained researchers code each intervention independently, and we compared entries and reconciled differences through discussion. Through this process, we provide examples and critical decision points. By documenting this systematic process, we hope that other researchers and practitioners will be able to consistently apply this process and produce replicable results.

CONCLUSIONS

EBI Mapping can be useful for coding the components, content and potential core elements of an existing EBI, which intervention planners can use to inform adoption, adaptation, and implementation of CRCS interventions. EBI Mapping also can be applied to other topic areas and contexts beyond CRCS. Given that additional materials were developed to support coding throughout the EBI Mapping process, future studies should continue to evaluate the feasibility and replicability of EBI Mapping. Additionally, more work needs to be done to determine whether the identified components are related to critical intervention outcomes, such as adoption, reach, effectiveness, implementation, and maintenance. This study illustrates a systematic way to move toward a process for identifying key features of effective interventions that can help increase the use of EBIs in practice.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Andrea Siceluff, MPH for her coding of the interventions included in this manuscript. We also acknowledge our collaboration with Drs. David Chambers, Cynthia Vinson, and Prajakta Adsul, as well as Tanuj Shroff and Annabelle Uy, MS at the National Cancer Institute for their feedback and insight into the development of the coding process.

This work was funded through a National Institutes of Health (NIH) subcontract to Dr. Fernandez (Contract HHSN26120140002B). Ms. Foster and Dr. Szeszulski were supported by NCI/NIH Grant T32/ CA057712 with additional funding for Dr. Szeszulski from the Michael & Susan Dell Center for Healthy Living. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funders. None of the funding agencies played any role in the design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, or reporting of data from this study.

APPENDIX

Fig. A1.

Heat map of methods used to address an ECAs’ determinants

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflicts of Interest: All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Human Rights: This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed Consent: This study does not involve human participants, and informed consent was therefore not required.

Welfare of Animals: This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Transparency Statement

This study and data analytic plan were not formally registered. Data, analytic code, and materials for this study are available from the authors upon request.

References

- 1. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69(1):7–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. US Preventive Services Task Force; Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, Curry SJ, et al. Screening for colorectal cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA, 2016;315(23), 2564–2575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Brenner H, Stock C, Hoffmeister M. Effect of screening sigmoidoscopy and screening colonoscopy on colorectal cancer incidence and mortality: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials and observational studies. BMJ. 2014;348:g2467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Haggar FA, Boushey RP. Colorectal cancer epidemiology: incidence, mortality, survival, and risk factors. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2009;22(4):191–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. de Moor JS, Cohen RA, Shapiro JA, et al. Colorectal cancer screening in the United States: Trends from 2008 to 2015 and variation by health insurance coverage. Prev Med. 2018;112:199–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Green, Beverly B., and Meenan Richard T.. . Colorectal cancer screening: The costs and benefits of getting to 80% in every community. Cancer. 2020;126(18), 4110–4113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Meester RG, Doubeni CA, Zauber AG, et al. Public health impact of achieving 80% colorectal cancer screening rates in the United States by 2018. Cancer. 2015;121(13):2281–2285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hawe P, Shiell A, Riley T. Complex interventions: how “out of control” can a randomised controlled trial be? BMJ. 2004;328(7455):1561–1563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rabin BA, Brownson RC, Haire-Joshu D, Kreuter MW, Weaver NL. A glossary for dissemination and implementation research in health. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2008;14(2):117–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chambers DA, Vinson CA, Norton WE, eds. Advancing the Science of Implementation Across the Cancer Continuum. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bach-Mortensen AM, Lange BCL, Montgomery P. Barriers and facilitators to implementing evidence-based interventions among third sector organisations: A systematic review. Implement Sci. 2018;13(1):103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dietrich AJ, Tobin JN, Cassells A, et al. Telephone care management to improve cancer screening among low-income women: A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(8):563–571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Breslow RA, Rimer BK, Baron RC, et al. Introducing the community guide’s reviews of evidence on interventions to increase screening for breast, cervical, and colorectal cancers. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35(suppl 1):S14–S20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sabatino SA, Lawrence B, Elder R, et al. ; Community Preventive Services Task Force . Effectiveness of interventions to increase screening for breast, cervical, and colorectal cancers: nine updated systematic reviews for the guide to community preventive services. Am J Prev Med. 2012;43(1):97–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Department of Health and Human Services. The Guide to Community Preventive Services. https://www.thecommunityguide.org/. Retrieved February 4, 2020.

- 16. Highfield L, Hartman MA, Mullen PD, Rodriguez SA, Fernandez ME, Bartholomew LK. Intervention mapping to adapt evidence-based interventions for use in practice: Increasing mammography among African American women. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:160103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Powell, B. J., Garcia, K. G., & Fernandez, M. E. Implementation strategies. In Chambers D, Vinson C,Norton WE, eds. Optimizing the Cancer Control Continuum: Advancing Implementation Research. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2018:98–120. [Google Scholar]

- 18. National Cancer Institute. Evidence-Based Cancer Control Programs. https://ebccp.cancercontrol.cancer.gov/index.do. Retrieved February 4, 2021.

- 19. Perez Jolles M, Lengnick-Hall R, Mittman BS. Core functions and forms of complex health interventions: A patient-centered medical home illustration. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(6):1032–1038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bartholomew Eldrigde LK, Markham CM, Ruiter RA, Fernández ME, Kok G, Parcel GS.. Planning Health Promotion Programs: An Intervention Mapping Approach. 4th ed.Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bartholomew LK, Parcel GS, Kok G, Gottlieb NH, Fernández ME.. Planning Health Promotion Programs: An Intervention Mapping approach. 3rd ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fernández-Esquer ME, Nguyen FM, Atkinson JS, et al. Sức Khỏe là Hạnh Phúc (Health is Happiness): Promoting mammography and pap test adherence among Vietnamese nail salon workers. Women Health. 2020;60(10):1206–1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kok G, Gottlieb NH, Peters GJ, et al. A taxonomy of behaviour change methods: An Intervention Mapping approach. Health Psychol Rev. 2016;10(3):297–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston. IM-ADAPT . https://www.imadapt.org/#/. Retrieved February 4, 2021. [PubMed]

- 25. Beach ML, Flood AB, Robinson CM, et al. Can language-concordant prevention care managers improve cancer screening rates? Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16(10):2058–2064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Denberg TD, Coombes JM, Byers TE, et al. Effect of a mailed brochure on appointment-keeping for screening colonoscopy: A randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(12):895–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tu SP, Taylor V, Yasui Y, et al. Promoting culturally appropriate colorectal cancer screening through a health educator: A randomized controlled trial. Cancer. 2006;107(5):959–966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Braun KL, Thomas WL Jr, Domingo JL, et al. Reducing cancer screening disparities in medicare beneficiaries through cancer patient navigation. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(2):365–370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Domingo JB, Davis EL, Allison AL, Braun KL. Cancer patient navigation case studies in Hawai’i: The complimentary role of clinical and community navigators. Hawaii Med J. 2011;70(12):257–261. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Collins LM, Murphy SA, Strecher V. The multiphase optimization strategy (MOST) and the sequential multiple assignment randomized trial (SMART): New methods for more potent eHealth interventions. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32(suppl 5):S112–S118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kiviniemi MT, Bennett A, Zaiter M, Marshall JR. Individual-level factors in colorectal cancer screening: A review of the literature on the relation of individual-level health behavior constructs and screening behavior. Psycho-Oncology, 2011; 20(10), 1023–1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Green BB, Wang CY, Horner K, et al. Systems of support to increase colorectal cancer screening and follow-up rates (SOS): Design, challenges, and baseline characteristics of trial participants. Contemp Clin Trials. 2010;31(6):589–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]