Abstract

Implementation strategies are systematic approaches to improve the uptake and sustainability of evidence-based interventions. They frequently focus on changing provider behavior through the provision of interventions such as training, coaching, and audit-and-feedback. Implementation strategies often impact intermediate behavioral outcomes like provider guideline adherence, in turn improving patient outcomes. Fidelity of implementation strategy delivery is defined as the extent to which an implementation strategy is carried out as it was designed. Implementation strategy fidelity measurement is under-developed and under-reported, with the quality of reporting decreasing over time. Benefits of fidelity measurement include the exploration of the extent to which observed effects are moderated by fidelity, and critical information about Type-III research errors, or the likelihood that null findings result from implementation strategy fidelity failure. Reviews of implementation strategy efficacy often report wide variation across studies, commonly calling for increased implementation strategy fidelity measurement to help explain variations. Despite the methodological benefits of rigorous fidelity measurement, implementation researchers face multi-level challenges and complexities. Challenges include the measurement of a complex variable, multiple data collection modalities with varying precision and costs, and the need for fidelity measurement to change in-step with adaptations. In this position paper, we weigh these costs and benefits and ultimately contend that implementation strategy fidelity measurement and reporting should be improved in trials of implementation strategies. We offer pragmatic solutions for researchers to make immediate improvements like the use of mixed methods or innovative data collection and analysis techniques, the inclusion of implementation strategy fidelity assessment in reporting guidelines, and the staged development of fidelity tools across the evolution of an implementation strategy. We also call for additional research into the barriers and facilitators of implementation strategy fidelity measurement to further clarify the best path forward.

Keywords: Implementation research, Implementation strategies, Implementation strategy fidelity, Implementation trials, Implementation research reporting

Implementation strategy fidelity, or the extent to which an implementation strategy is carried out as it was designed, is under-developed and under-reported, and the quality of reporting is decreasing over time. This position paper describes the costs and benefits of implementation strategy fidelity. We ultimately call for the continuation and improvement of implementation strategy fidelity measurement while offering pragmatic solutions to noted challenges. Future research is needed regarding the barriers and facilitators to implementation strategy fidelity measurement and reporting, the costs and cost-benefits of implementation strategy fidelity measurement, and the relationship between implementation strategy fidelity and implementation and clinical outcomes.

Lay Summary/Implications.

Implementation strategy fidelity is under-developed and under-reported, and the quality of reporting is decreasing over time.

This position paper describes the costs and benefits of implementation strategy fidelity. We ultimately call for the continuation and improvement of implementation strategy fidelity measurement while offering pragmatic solutions to noted challenges.

Future research is needed regarding the barriers and facilitators to implementation strategy fidelity measurement/reporting, the costs and cost–benefits of implementation strategy fidelity measurement, and the extent to which implementation strategy fidelity moderates the relationship between an implementation strategy and implementation outcomes.

BACKGROUND

This paper examines the state of implementation strategy fidelity measurement and argues for its improvement. We begin by framing the importance of implementation strategy fidelity by first defining fidelity as it is classically understood, in relation to intervention fidelity measurement, before expanding that definition to consider fidelity of implementation strategies. We then describe the benefits and challenges related to its measurement and suggest action steps implementation researchers might take to overcome them. We ultimately conclude that the benefits of implementation strategy fidelity measurement outweigh the costs, and call for changes at multiple levels and future research that might facilitate better measurement.

Intervention fidelity

Fidelity to an intervention represents an important implementation outcome in both research and practice settings [1–3]. Defined as the extent to which an intervention is implemented as originally intended, fidelity plays a central role in the assessment of a Type-III research error [2–5]. A Type-III error is defined as failure to implement an intervention as planned, leading to an erroneous conclusion that null results are due to attributes of the intervention itself, rather than to its mal-implementation [5]. Intervention fidelity also operates as a moderator of main effects pathways, such that efficacious interventions carried out with higher fidelity tend to yield better clinical outcomes compared to the same interventions delivered with lower fidelity [2, 6]. Intervention fidelity remains an important means of quality assurance in practice settings and in implementation research. Poor fidelity often explains why interventions that perform well in controlled research settings show worse outcomes in practice settings [7, 8]. Reviews of implementation outcome measurement also describe intervention fidelity as one of the most common targets of implementation strategies [9–11].

Implementation strategies

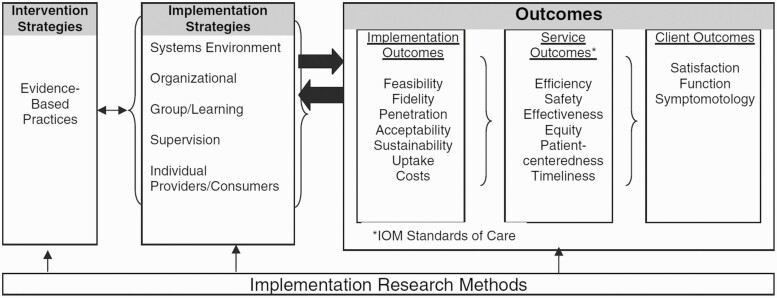

Implementation strategies are “deliberate and purposeful efforts to improve the uptake and sustainability of [evidence-based interventions (EBIs)],” to proximally affect implementation outcomes (e.g., adoption, appropriateness, feasibility, acceptability) that in turn distally affect service system and clinical outcomes through the successful implementation of an EBI [12]. Implementation strategies span multiple levels and categories [13, 14]. Examples include the restructuring of physical or virtual spaces, financial incentives, training, supervision, etc. Strategies address specific barriers to implementation of an EBI. For instance, if a team of providers newly trained in cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) are struggling to maintain fidelity in their sessions with clients, implementation strategies like promoting supervision or audit-and-feedback might re-enforce the counselors’ quality of CBT delivery, in-turn improving CBT fidelity, and ultimately lead to better client outcomes. The relationship among implementation strategies, implementation outcomes, and clinical or service outcomes are depicted in the Conceptual Model of Implementation Research developed by Proctor et al. (2009) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Conceptual model of implementation research. Proctor, E. K., Landsverk, J., Aarons, G., Chambers, D., Glisson, C., & Mittman, B. (2009). Implementation Research in Mental Health Services: an Emerging Science with Conceptual, Methodological, and Training challenges. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 36(1), 24–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-008-0197-4.

Because implementation research regularly aims to improve clinical practice (e.g., clinical guideline adherence), some of the most common implementation strategies are inextricably linked to human behavior change (e.g., training, coaching, audit-and-feedback) [15–17]. A recent review by Lewis and colleagues (2020) found that implementation strategies were most commonly: (1) utilized in behavioral/community mental health settings, (2) targeted at improving behavioral EBIs, and (3) informed by behavior change theory [18]. Because behavior change efforts in healthcare are often complex, Lewis et al. (2018) focus on the importance of identifying mechanisms within implementation strategies most responsible for causing change. The authors ultimately call for improvements in several areas related to implementation strategy specification and measurement, including the measurement of moderating variables like implementation strategy fidelity [19].

Implementation strategy fidelity

Similar to intervention fidelity, fidelity to an implementation strategy is defined as carrying out the strategy as it was designed [20]. Despite its importance, measurement of implementation strategy fidelity is both under-developed and under-reported [20, 21]. In their scoping review of fidelity measurement to implementation strategies, Slaughter et al. (2015) concluded that fidelity domains were on average inadequately measured across trials, and that few reports of implementation strategy fidelity existed [20]. The authors also found that the quality of reporting on fidelity to implementation strategies demonstrated a statistically significant decline over time and suggested their results may be due to a lack of measurement tools [20]. The poor reporting on descriptions of implementation strategies, combined with the lack of fidelity description regarding those same strategies, compound to create an environment where it is not always clear which strategies were performed nor how well they were performed. Given these challenges, it is understandable that implementation strategy fidelity has yet to take on a consistent focus within trials of implementation strategies.

In this position paper, we describe a confluence where a desire for conceptual and methodological rigor (e.g., fidelity instruments with demonstrated psychometric properties), runs into common logistical research challenges (e.g., the measurement of a complex variable and data collection costs). In the sections below, we carefully consider the benefits and challenges regarding the value of implementation strategy fidelity measurement and reporting. We ultimately argue that both measurement and reporting need to improve, and we offer pragmatic short-term solutions and structural long-term remedies.

DISCUSSION

Benefits of implementation strategy fidelity measurement

Like fidelity measurement of intervention delivery, fidelity measurement of implementation strategy delivery strengthens the quality of implementation trials. Fidelity measurement facilitates the assessment of a Type-III research error in clinical trials, a paradigm that extends to implementation research [2–5]. Without implementation strategy fidelity assessment, researchers cannot be assured that implementation strategies (or the mechanisms most responsible for change within them), are responsible for impacts on implementation or clinical outcomes. Or conversely, that lack of impact on clinical outcomes is due to limitations of an implementation strategy’s mechanisms as opposed to limitations in its fidelity.

A lack of implementation strategy fidelity measurement may in part explain variations in effectiveness reported across trials of implementation strategies. Although reviews of implementation strategies tend to show significant and positive impacts on outcomes in expected directions, such reviews often note wide variations in effectiveness among studies. Prior et al. (2008) and Hakkennes et al. (2008) describe this phenomenon in the context of their reviews focused on medical guideline implementation strategies. Prior et al. (2008) found that multifaceted and reminder-system strategies displayed the most positive results on guideline implementation, however their effectiveness ranged from 0% to 60% and 0% to 56%, respectively [22]. Hakkennes et al. (2008) found that reviewed studies showed only small to moderate effects with wide variations as well [23]. The authors ultimately call for the use of process measures in future trials of implementation strategies. Similarly, Powell et al. (2014) reviewed trials of implementation strategies to improve mental health EBI implementation. The authors concluded that 64% of the reviewed strategies resulted in statistically significant positive impacts, but similarly found wide variations in effectiveness among studies [24]. The authors note their inability to assess the fidelity of implementation strategies as a limitation and call for further research into fidelity measurement [24].

Implementation strategy fidelity measurement provides an opportunity to explore a moderation pathway. Intervention fidelity moderates the positive relationship between an EBI and its clinical outcomes, such that EBIs with higher fidelity tend to yield better clinical outcomes compared to EBIs with lower fidelity [2, 6]. It is plausible that implementation strategy fidelity similarly moderates the relationship between implementation strategies and implementation outcomes (and thereby clinical outcomes as well).

The quality and clarity of implementation research may additionally benefit from increased measurement and reporting of implementation strategy fidelity. Implementation strategy fidelity measurement requires a detailed account of implementation strategies themselves and their adaptations [20]. The quality of such descriptions has been criticized in the past and is discussed later in this article [25, 26]. Improving implementation strategy fidelity measurement may provide an additional benefit by nudging researchers toward improved implementation strategy specification.

Challenges in implementation strategy fidelity measurement

While implementation strategy fidelity holds both conceptual and methodological importance, it also introduces an additional, complex, and potentially costly variable to measure. In their description of intervention fidelity, Carroll et al. (2007) detail four main fidelity domains (details of content, coverage, frequency, and duration) along with four additional domains that affect the level of fidelity (comprehensiveness of component description, implementation strategies, quality of delivery, and participant responsiveness) [27]. While the domains of content, coverage, frequency, and duration may be straightforward to assess, domains focused on measuring behavior like quality of delivery, or on attitudes like participant responsiveness, may require more complex scale development like the creation of items, item-responses, or reliability/validity evaluation. Comprehensive fidelity measurement requires an assessment of each domain.

Fidelity domains vary regarding their level of effort and cost to measure, some often more challenging than others. Intervention fidelity measurement reviews commonly describe how “structural” fidelity domains like coverage, frequency, and duration are measured and reported more readily compared to elements that required the development or use of additional scales, like quality or participant responsiveness which often require more labor-intensive data collection (e.g., observation by trained fidelity raters) [21, 28–30].

Despite its associated costs and effort regarding measure development and subsequent inter-rater reliability testing, observation is often viewed as a gold standard data collection modality for domains like quality and participant responsiveness [31, 32]. Clinician self-report, or client report on clinician behavior, is often less costly but can also introduce positive-response bias [21]. In their work on fidelity measurement in behavioral research, Ledford et al. (2014) highlight how implementers regularly overestimated their own adherence to implementation procedures. To mitigate these challenges, recommendations have been made to utilize multiple data sources when measuring fidelity domains (e.g., pairing self-report with observation) [33, 34]. While an all-encompassing approach to fidelity measurement may appeal to researchers theoretically, the costs and stakeholder burden associated with intensive fidelity measurement may be prohibitive in the context of some implementation trials. The differing degrees between costs and effort to measure various fidelity domains may result in no or partial fidelity measurement, leading to results that may be challenging to interpret.

Similar to interventions, implementation strategies regularly undergo adaptations to fit different contexts and require a similar account of each adaptation [35, 36]. In fact, numerous authors have noted the importance of prospectively tracking implementation strategies carefully to document changes over time and report them in ways that are consistent with reporting recommendations for implementation strategies [18, 29, 37–40]. This is particularly important for strategies like facilitation, that are tailored to address site-specific needs. While tracking adaptations improves our understanding of implementation strategies’ inner-workings, adaptation necessitates change to the fidelity measurement of each adapted implementation strategy, potentially posing additional effort and costs. For example, Haley et al. (2021) describe the tracking of a facilitation strategy meant to increase the adoption of social determinants of health screening and referral activities. The authors utilize several implementation frameworks to specify implementation strategies, describe implementation barriers, and the modifications to strategies used to overcome them. They ultimately describe several adaptations including (1) the reduced frequency of peer support meetings, (2) additional information sharing between study clinics, and (3) additional items included in a data collection tool [40]. Adaptations of implementation strategy fidelity assessment could include (1) participant responsiveness to the new frequency of peer support meetings, (2) the receipt and additional content of the new information shared between study clinics, and (3) the receipt and content of the new questions added to the data collection tool.

The transition from implementation strategy fidelity measurement in research to its measurement in practice represents additional challenges as well. Bond et al. (2011) describe this challenge in-part through their case study measuring fidelity of Individual Placement and Support (IPS), an intervention that improves employment outcomes for individuals with mental health disorders. The authors describe the multiple purposes of fidelity measurement: (1) as a latent, unobservable variable assessing intervention receipt in the context of a trial, (2) as a quality assurance metric that healthcare agencies use to ensure they are “getting the intervention they paid for” in practice, and (3) as a tool for supervisors to track and build the treatment capacity of individual clinicians delivering the intervention [41]. Bond et al. describe how a fidelity tool developed to assess intervention receipt during a research phase, may require adaptation when used as a means of ensuring the quality of individual clinicians delivering the intervention in practice [41]. In addition to the knowledge, time, and effort required to adapt a fidelity tool from a research setting to a practice setting, the costs associated with fidelity measurement are also likely be transferred from a research team to the organization that takes-up and sustains that implementation strategy.

Moving implementation strategy fidelity measurement forward

Despite the challenges inherent in implementation strategy fidelity measurement and reporting, we believe that the pursuit of improving both are not only worthwhile, but necessary to enhance the quality of implementation research. The recommendations herein include pragmatic actions that implementation researchers can take immediately, calls for future research to further develop implementation strategy fidelity measurement, and structural changes at the funding and publication levels.

Table 1 depicts the current state of implementation strategy fidelity measurement challenges alongside our recommendations for improvements. To give readers a sense of the state of implementation strategy fidelity measurement compared to intervention fidelity measurement, these challenges and recommendations are shown side-by-side with Toomey et al.’s (2020) work on challenges of and recommendations to intervention fidelity measurement improvements [30]. Overall, the state of implementation strategy fidelity is not at the level of intervention fidelity, and more work is required to understand the specific barriers and facilitators to implementation strategy fidelity measurement. One similarity is shared between the two regarding challenges in defining and conceptualizing fidelity, which may serve as a good starting place for implementation strategy fidelity efforts.

Table 1.

A comparison of challenges and recommendations for improving intervention fidelity (Toomey et al., 2020) and implementation strategy fidelity

| Toomey et al. 2020 (intervention fidelity) | Implementation strategy fidelity | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Overarching issue | Specific recommendations | Overarching issue | Specific recommendations |

| Lack of standardization regarding how fidelity is conceptualized and defined | Clarify how fidelity is defined and conceptualized | Lack of standardization regarding how fidelity is conceptualized and defined | Build consensus definition and conceptualization of implementation strategy fidelity |

| Limited focus beyond assessing of fidelity of delivery | Consider fidelity beyond intervention delivery 2b. Consider both enhancement and assessment strategies explicitly | Limited focus on assessing implementation strategy fidelity | Increase understanding of barriers and facilitators to implementation strategy fidelity assessment |

| Limited use of existing fidelity frameworks or guidance | Make use of existing frameworks | Increase focus on implementation strategy fidelity incrementally throughout the strategy’s evolution | |

| Lack of focus on quality and comprehensiveness of fidelity assessment strategies | Consider the psychometric and implementation properties of mixed method fidelity assessment strategies | Utilize mixed methods approaches to fidelity assessment | |

| Consider the use of the Implementation Strategy Fidelity Checklist (throughout study timeline) | |||

| Lack of explicit focus on the balance between fidelity and adaptation | Consider the need for balance between fidelity and adaptation a-priori | Poor reporting on implementation strategy and mechanism specification | Make use of existing implementation strategy specification frameworks |

| Poor reporting of how intervention fidelity is addressed | Comprehensively report use of strategies to enhance and assess fidelity and results of fidelity assessments | Poor reporting on implementation strategy and mechanism adaptation | Make use of adaptation tracking techniques, assess fidelity to adapted implementation strategies |

| Cost of implementation strategy fidelity measurement | Develop innovations to facilitate less costly implementation strategy fidelity measurement | ||

While we note the challenge of quantitative fidelity measure development and assessment, mixed methods approaches may facilitate measurement more readily while possibly increasing the quality of fidelity measurement overall. Techniques like triangulation, sequential analysis, or ethnography can be used to describe fidelity domains in combination with quantitative results [42–44]. For example, Williams et al. used mixed methods to evaluate fidelity of a physical activity intervention delivered by primary care physicians. The authors measured the structural domains quantitatively, and participant responsiveness and quality of delivery qualitatively [45]. Williams et al. conclude that the use of mixed methods helped facilitate a more holistic understanding of fidelity than would have been provided by quantitative or qualitative measurement alone [45]. Mixed methods have also been used in the assessment of implementation strategy fidelity. When assessing fidelity to a practice facilitation implementation strategy meant to improve provider guideline adherence, Berry et al. measured the fidelity domains of content, frequency, duration, coverage, and quality quantitatively, but assessed participant responsiveness qualitatively [46]. The use of qualitative and mixed methods is common among implementation trials, and opportunities may exist to add questions that tap specific implementation strategy fidelity domains within already-planned qualitative activities [47].

Innovations in fidelity measurement may additionally facilitate less costly or labor-intensive data collection efforts. Beidas et al. describe their trial comparing different types of fidelity measurement to youth CBT, a therapist delivered EBI addressing a range of mental health outcomes. Their protocol outlines a four-group trial where various fidelity data collection modalities are compared to the gold standard of direct observation [48]. The results of this study, and others like it, can help determine the costs and cost-effectiveness of different modalities. It also might not always be necessary to rate an entire data set to accurately measure fidelity. Caperton et al. examined the amount of raw data required to measure fidelity to therapist delivered motivational interviewing (MI) sessions, an EBI to improve substance abuse outcomes. The authors found that rating just one-third of an MI session was sufficient to determine the fidelity of the entire session [49]. Due to their focus on inter-personal relationships, many implementation strategies (e.g., training, facilitation, coaching, audit-and-feedback) share similarities with the interventions described above. Implementation strategy fidelity measurement could, therefore, draw from fidelity measurement of behavioral interventions like MI or CBT in terms of how to conceptualize and measure fidelity of behavior implementation strategies [50–52].

While improvements in measurement are necessary, improvements in reporting are equally important. Slaughter et al. call for researchers to apply the Implementation Strategy Fidelity Checklist, a tool that assesses the quality of fidelity reporting in implementation trials, to their trial manuscripts prior to publication so that under-reported fidelity domains might be highlighted and improved [20]. While researchers may find that some fidelity domains have not been fully measured during their trials, the application of the checklist may still prompt researchers to improve reporting on what fidelity data they might have available.

We further suggest that the Implementation Strategy Fidelity Checklist could be applied at the study design phase when measures are first selected or developed. A preassessment of a study’s ability to report on implementation strategy fidelity may highlight measurement gaps for certain fidelity domains at the outset. We recognize that while comprehensive fidelity measurement exists as a theoretical ideal, it is often unfeasible in the context of many study budgets or timelines and may not always be necessary. Bond et al. reviewed the fidelity of several interventions to improve mental health outcomes. They found that team-based interventions, whose fidelity were determined mostly by organizational factors like staffing or receipt of services, achieved higher levels of fidelity compared to interventions that focused more on individual clinician behavior (like adherence to a counseling intervention) [53]. It could be that implementation strategies that focus more on organizational structural change require less attention to fidelity domains like quality or participant responsiveness compared to strategies that rely more on interpersonal interactions. Hankonen’s work on participant reception and enactment, or the extent to which participants connect with and enact the knowledge/skills learned through a health intervention, help highlight the importance of comprehensive fidelity measurement when EBI components focus on changing individuals’ behavior. The author notes that when the target of an EBI encompasses individual behavior change, the need to measure participants’ reception and enactment of intervention content becomes critical [54]. Fidelity indicators like “number of sessions delivered” or “adequate content delivered” may tell us that an actor delivered structural intervention components as intended, but such indicators may not tell us about how well the components were received by their targets, nor how able the targets were to utilize what they learned [54]. Relating back to implementation strategies and their fidelity, this point highlights again the need to adequately describe implementation strategies, their action targets, and their mechanisms most responsible for change in implementation outcomes [19]. A clear understanding of the inner workings of a strategy help to define the fidelity domains most essential to their success.

Recent reviews of intervention fidelity call for the development and utilization of higher quality fidelity measures [55, 56]. We share these sentiments as they relate to implementation strategy fidelity. However, while high quality fidelity tools may serve as an end goal, we recognize that implementation strategy fidelity tools may be best suited for development in stages given the challenges outlined above. For example, researchers piloting a new implementation strategy may only have the ability to measure if their strategy was delivered and to what extent. The burden of collecting, analyzing, and reporting this information is likely to be low given such that data are often collected during the execution of the implementation strategy itself [57]. The later stages of an implementation strategy’s evolution may be best suited for more robust fidelity measurement, including psychometric evaluation. Stockdale et al. suggest that implementation strategy fidelity measures might be validated in the context of Hybrid 3 trials given their tendencies to utilize larger sample sizes [58]. Incremental improvements over time likely pose the most realistic path toward improved measurement. The addition of an implementation strategy fidelity measurement step to Proctor et al. (2009)’s Conceptual Model of Implementation Research (Fig. 1) may help facilitate further measurement [12].

CONCLUSION

In this position article, we describe the benefits and challenges inherent in implementation strategy fidelity measurement. The most recent review of implementation strategy fidelity describes measurement as under-developed, under-reported, and decreasing in quality over-time; recent guidance on implementation trials also calls for the inclusion of implementation strategy process evaluation (inclusive of fidelity measurement) [20, 59]. Explanations regarding the state of implementation strategy fidelity measurement are not yet fully understood, and more research into the specific barriers and facilitators that influence implementation researchers are necessary. In the conclusion of their review on the history of intervention fidelity, Bond et al. ultimately determine that the benefits of fidelity measurement outweigh the costs. The authors describe research and clinical care that lack fidelity measurement as a prescientific “black box” era where an intervention, its components, and their impact on clinical outcomes are not made explicitly clear [28]. We share this sentiment as it relates to implementation strategy fidelity measurement and describe the need to better understand the inner workings of causal chains under examination in implementation trials. Clearer specifications of implementation strategies and their mechanisms most responsible for change, the degrees of fidelity they achieve, and the extent to which implementation strategy fidelity acts as a main effects moderator will help to move implementation research moving forward.

Funding

C.F.A. and B.W.P. were supported by the National Institute of Mental Health through 3U19MH113202-04S1 (Pence, PI). V.G., B.J.P., and M.X.B.N. were supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse through 1R01DA047876 (Go, PI). B.J.P. was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health through K01MH113806 (Powell, PI).

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest: C.F.A., B.J.P., B.W.P., M.X.B.N., C.G., and V.G. declare that they have no competing interests.

Human Rights: This article does not contain any study of human participants.

Informed Consent: This study does not involve human participants.

Welfare of animals: This article does not contain any study of animals.

Study Registration: N/A.

Analytic Plan Preregistration: N/A.

Analytic Code Availability: N/A.

Materials Availability: N/A.

Data Availability

N/A – This position paper does not include data.

References

- 1. Mowbray CT, Holter MC, Teague GB, Bybee D. Fidelity criteria: Development, measurement, and validation. Am J Eval. 2003;24(3):315–340. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dusenbury L, Brannigan R, Falco M, Hansen WB. A review of research on fidelity of implementation: implications for drug abuse prevention in school settings. Health Educ Res. 2003;18(2):237–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gearing RE, El-Bassel N, Ghesquiere A, Baldwin S, Gillies J, Ngeow E. Major ingredients of fidelity: a review and scientific guide to improving quality of intervention research implementation. Clin Psychol Rev. 2011;31(1):79–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Summerfelt WT. Program strength and fidelity in evaluation. Appl Dev Sci. 2003;7(2):55–61. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dobson D, Cook TJ. Avoiding type III error in program evaluation: Results from a field experiment. Eval Program Plann. 1980;3(4):269–276. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dane AV, Schneider BH. Program integrity in primary and early secondary prevention: are implementation effects out of control? Clin Psychol Rev. 1998;18(1):23–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bellg AJ, Borrelli B, Resnick B, et al. ; Treatment Fidelity Workgroup of the NIH Behavior Change Consortium . Enhancing treatment fidelity in health behavior change studies: best practices and recommendations from the NIH Behavior Change Consortium. Health Psychol. 2004;23(5):443–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Elliott DS, Mihalic S. Issues in disseminating and replicating effective prevention programs. Prev Sci. 2004;5(1):47–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wagenaar BH, Hammett WH, Jackson C, Atkins DL, Belus JM, Kemp CG. Implementation outcomes and strategies for depression interventions in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Glob Ment Health (Camb). 2020;7:e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lewis CC, Fischer S, Weiner BJ, Stanick C, Kim M, Martinez RG. Outcomes for implementation science: An enhanced systematic review of instruments using evidence-based rating criteria. Implement Sci. 2015;10:155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Proctor E, Hiie S, Raghavan R, et al. . Outcomes for implementation research: Conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Adm Policy Ment Heal. 2010;38:65–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Proctor EK, Landsverk J, Aarons G, Chambers D, Glisson C, Mittman B. Implementation research in mental health services: an emerging science with conceptual, methodological, and training challenges. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2009;36(1):24–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Powell BJ, Waltz TJ, Chinman MJ, et al. . A refined compilation of implementation strategies: results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) project. Implementation Science. 2015;10(1):1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Waltz TJ, Powell BJ, Matthieu MM, et al. . Use of concept mapping to characterize relationships among implementation strategies and assess their feasibility and importance: results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) study. Implement Sci. 2015;10(1):1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Spoon D, Rietbergen T, Huis A, et al. . Implementation strategies used to implement nursing guidelines in daily practice: A systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2020;111:103748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kovacs E, Strobl R, Phillips A, et al. . Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of the effectiveness of implementation strategies for non-communicable disease guidelines in primary health care. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(7):1142–1154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Girlanda F, Fiedler I, Becker T, Barbui C, Koesters M. The evidence-practice gap in specialist mental healthcare: systematic review and meta-analysis of guideline implementation studies. Br J Psychiatry. 2017;210(1):24–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lewis CC, Boyd MR, Walsh-Bailey C, et al. . A systematic review of empirical studies examining mechanisms of implementation in health. Implement Sci. 2020;15(1):1–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lewis CC, Klasnja P, Powell BJ, et al. . From classification to causality: Advancing understanding of mechanisms of change in implementation science. Front Public Heal. 2018;6:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Slaughter SE, Hill JN, Snelgrove-Clarke E. What is the extent and quality of documentation and reporting of fidelity to implementation strategies: a scoping review. Implement Sci. 2015;10:129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Walton H, Spector A, Tombor I, Michie S. Measures of fidelity of delivery of, and engagement with, complex, face-to-face health behaviour change interventions: A systematic review of measure quality. Br J Health Psychol. 2017;22(4):872–903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Prior M, Guerin M, Grimmer-Somers K. The effectiveness of clinical guideline implementation strategies—a synthesis of systematic review findings. J Eval Clin Pract. 2008;14(5):888–897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hakkennes S, Dodd K. Guideline implementation in allied health professions: a systematic review of the literature. Qual Saf Health Care. 2008;17(4):296–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Powell BJ, Proctor EK, Glass JE. A systematic review of strategies for implementing empirically supported mental health interventions. Res Soc Work Pract. 2014;24(2):192–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rudd BN, Davis M, Beidas RS. Integrating implementation science in clinical research to maximize public health impact: a call for the reporting and alignment of implementation strategy use with implementation outcomes in clinical research. Implement Sci. 2020;15(1):1–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wilson PM, Sales A, Wensing M, et al. . Enhancing the reporting of implementation research. Implement Sci. 2017;12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Carroll C, Patterson M, Wood S, Booth A, Rick J, Balain S. A conceptual framework for implementation fidelity. Implement Sci. 2007;2:40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bond GR, Drake RE. Assessing the fidelity of evidence-based practices: History and current status of a standardized measurement methodology. Adm Policy Ment Heal Ment Heal Serv Res. 2020;47(6):874–884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. O’Shea O, McCormick R, Bradley JM, O’Neill B. Fidelity review: a scoping review of the methods used to evaluate treatment fidelity in behavioural change interventions. Phys Ther Rev. 2016;21(3–6):207–214. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Toomey E, Hardeman W, Hankonen N, et al. . Focusing on fidelity: narrative review and recommendations for improving intervention fidelity within trials of health behaviour change interventions. Health Psychol Behav Med. 2020;8(1):132–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Schoenwald SK, Garland AF, Chapman JE, Frazier SL, Sheidow AJ, Southam-Gerow MA. Toward the effective and efficient measurement of implementation fidelity. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2011;38(1):32–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Schoenwald SK. It’s a Bird, It’s a Plane, It’s... Fidelity measurement in the real world. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 2011;18(2):142–147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ledford JR, Gast DL. Measuring procedural fidelity in behavioural research. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2014;24(3-4):332–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Mowbray CT, Megivern D, Holter MC. Supported education programming for adults with psychiatric disabilities: results from a national survey. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2003;27(2):159–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Powell BJ, Beidas RS, Lewis CC, et al. . Methods to improve the selection and tailoring of implementation strategies. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2017;44(2):177–194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Walsh-Bailey C, Palazzo LG, Jones SM, et al. . A pilot study comparing tools for tracking implementation strategies and treatment adaptations. Implement Res Pract. 2021;2:26334895211016028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bunger AC, Powell BJ, Robertson HA, MacDowell H, Birken SA, Shea C. Tracking implementation strategies: a description of a practical approach and early findings. Health Res Policy Syst. 2017;15(1):15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Boyd MR, Powell BJ, Endicott D, Lewis CC. A method for tracking implementation strategies: An exemplar implementing measurement-based care in community behavioral health clinics. Behav Ther. 2018;49(4):525–537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Miller CJ, Barnett ML, Baumann AA, Gutner CA, Wiltsey-Stirman S. The FRAME-IS: a framework for documenting modifications to implementation strategies in healthcare. Implement Sci. 2021;16(1):1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Haley AD, Powell BJ, Walsh-Bailey C, et al. . Strengthening methods for tracking adaptations and modifications to implementation strategies. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2021;21:133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bond GR, Becker DR, Drake RE. Measurement of fidelity of implementation of evidence-based practices: Case example of the IPS fidelity scale. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 2011;18(2):126–141. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Toomey E, Matthews J, Hurley DA. Using mixed methods to assess fidelity of delivery and its influencing factors in a complex self-management intervention for people with osteoarthritis and low back pain. BMJ Open. 2017;7(8):e015452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hanckel B, Ruta D, Scott G, Peacock JL, Green J. The Daily Mile as a public health intervention: a rapid ethnographic assessment of uptake and implementation in South London, UK. BMC Public Heal. 2019;19(1):1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Smith-Morris C, Lopez G, Ottomanelli L, Goetz L, Dixon-Lawson K. Ethnography, fidelity, and the evidence that anthropology adds: supplementing the fidelity process in a clinical trial of supported employment. Med Anthropol Q. 2014;28(2):141–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Williams SL, McSharry J, Taylor C, Dale J, Michie S, French DP. Translating a walking intervention for health professional delivery within primary care: A mixed-methods treatment fidelity assessment. Br J Health Psychol. 2020;25(1):17–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Berry CA, Nguyen AM, Cuthel AM, et al. . Measuring implementation strategy fidelity in healthyhearts NYC: A complex intervention using practice facilitation in primary care. Am J Med Qual. 2021;36(4):270–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Southam-Gerow MA, Dorsey S. Qualitative and mixed methods research in dissemination and implementation science: introduction to the special issue. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2014;43(6):845–850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Beidas RS, Maclean JC, Fishman J, et al. . A randomized trial to identify accurate and cost-effective fidelity measurement methods for cognitive-behavioral therapy: Project FACTS study protocol. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16(1):1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Caperton DD, Atkins DC, Imel ZE. Rating motivational interviewing fidelity from thin slices. Psychol Addict Behav. 2018;32(4):434–441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Jelsma JG, Mertens VC, Forsberg L, Forsberg L. How to measure motivational interviewing fidelity in randomized controlled trials: Practical Recommendations. Contemp Clin Trials. 2015;43:93–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Haddock G, Beardmore R, Earnshaw P, et al. . Assessing fidelity to integrated motivational interviewing and CBT therapy for psychosis and substance use: the MI-CBT fidelity scale (MI-CTS). J Ment Health. 2012;21(1):38–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Hartley S, Scarratt P, Bucci S, et al. . Assessing therapist adherence to recovery-focused cognitive behavioural therapy for psychosis delivered by telephone with support from a self-help guide: psychometric evaluations of a new fidelity scale. Behav Cogn Psychother. 2014;42(4):435–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Bond GR, Drake RE, McHugo GJ, Rapp CA, Whitley R. Strategies for improving fidelity in the National Evidence-Based Practices Project. Res Soc Work Pract. 2009;19(5):569–581. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Hankonen N. Participants’ enactment of behavior change techniques: a call for increased focus on what people do to manage their motivation and behavior. Health Psychol Rev. 2021;15(2):185–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Lambert JD, Greaves CJ, Farrand P, Cross R, Haase AM, Taylor AH. Assessment of fidelity in individual level behaviour change interventions promoting physical activity among adults: a systematic review. BMC Public Heal. 2017;17(1):1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Begum S, Yada A, Lorencatto F. How has intervention fidelity been assessed in smoking cessation interventions? A Systematic Review. J Smok Cessat. 2021;2021:6641208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Proctor EK, Powell BJ, McMillen JC. Implementation strategies: recommendations for specifying and reporting. Implement Sci. 2013;8:139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Stockdale SE, Hamilton AB, Bergman AA, et al. . Assessing fidelity to evidence-based quality improvement as an implementation strategy for patient-centered medical home transformation in the Veterans Health Administration. Implement Sci. 2020;15(1):18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Wolfenden L, Foy R, Presseau J, et al. . Designing and undertaking randomised implementation trials: guide for researchers. Bmj. 2021;372:m3721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

N/A – This position paper does not include data.