Abstract

Objective:

Pediatric palliative care is a top-level care system that focuses on improving the quality of life of the child and family. Quality of life is an expression of individual well-being based on an individual's assessment of their own life. It includes satisfaction in all areas of life, including physical and mental health, environment, and social areas.

Methods:

The study was conducted with the primary caregiver parents of children admitted to the pediatric palliative care service of the Health Science University İzmir Dr. Behçet Uz Child Disease and Surgery Training and Research Hospital. The Turkish version of the World Health Organization Quality of Life WHOQOL-Bref (TR) questionnaire was applied with a personal information form containing demographic data.

Results:

Eighty-four patients were hospitalized in the specified period, and 67 primary caregiver parents agreed to participate in the study. Total scores evaluated by WHOQOL-Bref (TR); the physical domain was 19.95 ± 3.30, the mental domain was 19.95 ± 3.18, the social domain was 10.11 ± 2.40, and surrounding area was 16.38 ± 2.82. The physical and psychological subgroups' scores were statistically significantly higher in primary caregiver parents with good social support (P < .005).

Conclusion:

It has been determined that in order to increase the quality of life and care of children with life-limiting and/or threatening diseases, the quality of life of primary caregiver parents should be increased, and “social support” procurement, which has the most important effect on the quality of life, is an important need.

Keywords: Child, life quality, pediatric palliative care, WHOQOL-Bref(TR)

What is already known on this topic?

•It is known that the quality of life of individuals with life-threatening/limiting diseases and their families decreases. Pediatric palliative care is a top-level care system focused on improving the quality of life of this patient group.

What this study adds on this topic?

•In pediatric palliative care, which is a new field in our country, there are no data on the quality of life of the child and family in need of care. Our study is the first to evaluate the quality of life of primary caregiver parents and shed light on what can be done in our country.

INTRODUCTION

Pediatric palliative care (PPC) is a top-level care system that focuses on improving the child's and family's quality of life and considering the physical, mental, social, and spiritual needs. Having a child with a life-threatening or restrictive disease brings many problems regardless of its etiology. A person who takes care of an individual who is incapable of performing daily life activities due to a physical and mental illness is defined as a “caregiver” and the concept of caregiver gains importance with the technological developments in medicine.1 In our country, the care of the patients and people in need of care is generally provided by their families and it is perceived as a family responsibility. Becoming a caregiver is an unselectable and unplanned situation. Therefore, adjustment to this situation occurs after the situation occurs.2,3 Giving care can lead to many difficulties in addition to positive features such as increasing sincerity and love, finding meaning thanks to the experience of giving care, getting social support from other individuals, self-esteem, and personal satisfaction.4 In addition to the child's condition, many psychological, social, financial, and education problems may accompany.5-7

Quality of life is defined as a whole, including perception, emotion, and thought processes based on the individual's evaluation of his/her own life. It is an expression of individual well-being and includes satisfaction in all areas of life, such as physical and mental health, environment, and social areas.8 Having a child with a life-restricting or -threatening disease negatively affects the lives, feelings, thoughts, and behaviors of family members. Primary caregiver parents may need to change their duties and responsibilities, financial resources, daily activities, and behaviors.9 Increasing the quality of life provides much more adequate attention to the child's care, and this affects the lives of children with life-limiting or -threatening diseases.10 There are no data on quality of life in pediatric palliative care, a very new field in our country. This study was planned to evaluate the quality of life of primary care parents of pediatric patients admitted to the pediatric palliative care service.

METHODS

Organization of PPC Unit

Health Sciences University İzmir Dr. Behçet Uz Children Disease Research and Training Hospital is a tertiary referral hospital, and the PPC center started to serve in November 2018. Our clinic, which is the third PPC center in our country, is the largest center in the Aegean region, created by taking European and American examples into consideration. Our pediatric palliative care center has 17 beds and is an example of teamwork consisting of 3 doctors, 8 nurses, 4 staff, 1 psychologist, 1 dietician, 1 social worker, 1 physiotherapist, 1 religious worker, and 1 secretary. To our pediatric palliative care unit, children whose treatment is possible but unsuccessful (cancer, children awaiting transplantation, and complex cyanotic congenital heart disease), with potentially progressive conditions (cystic fibrosis, severe immunodeficiency, muscular dystrophy), without therapeutic options (trisomy 13, trisomy 18, osteogenesis imperfecta), children with non-progressive but irreversible disease (cerebral palsy) are accepted. Local ethics committee (2020/07/02-426) and all our patients' primary caregiver parents approval has been received.

Study Design

The study was planned as a cross-sectional descriptive questionnaire study. It was administered to the primary caregiver parents of children admitted to the pediatric palliative care service between December 2018 and June 2019. The sample consisted of primary caregiver parents whose children were admitted to the PPC service and agreed to participate in the study. Primary caregiver parents who received support from a psychologist/psychiatrist and who used antidepressants because of their mental illness were excluded from the study. Since the study aimed to evaluate the quality of life before pediatric palliative care, it was conducted on day 0 of admission to the service.

Evaluation of WHOQOL-Bref (TR)

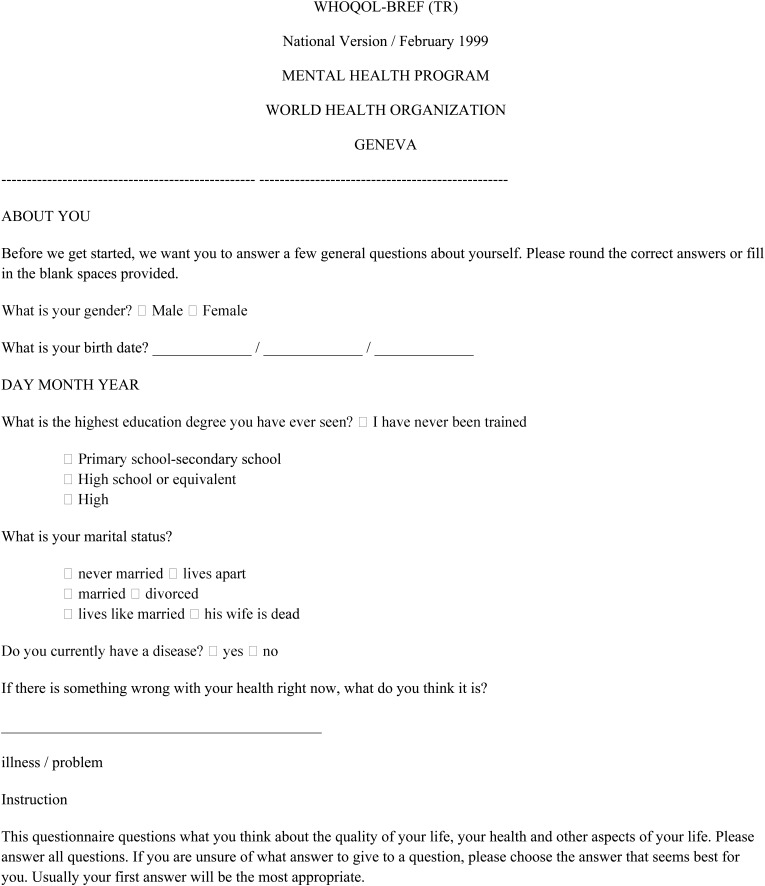

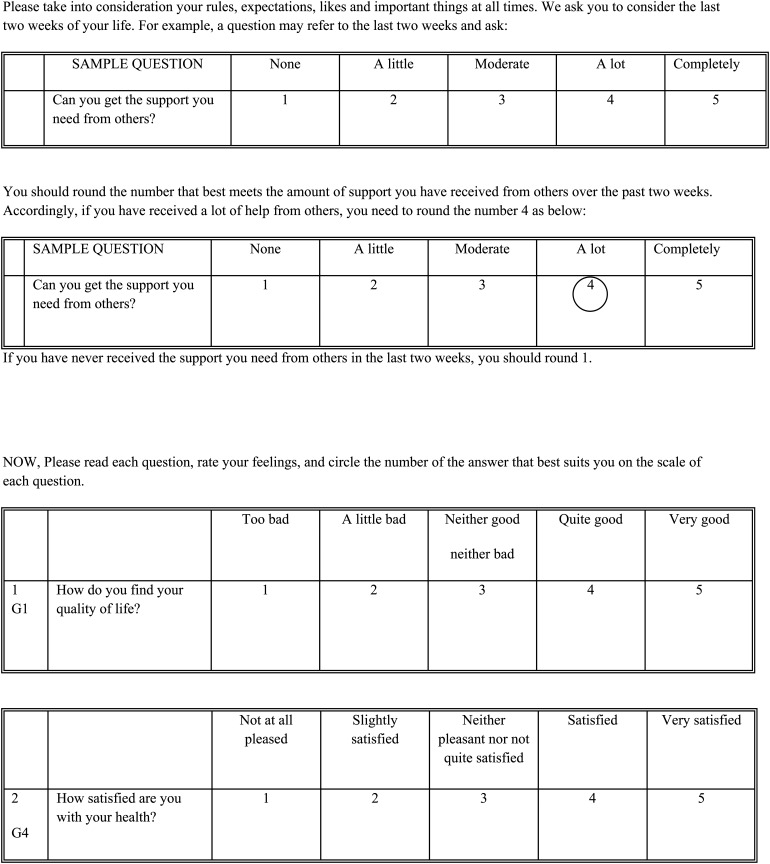

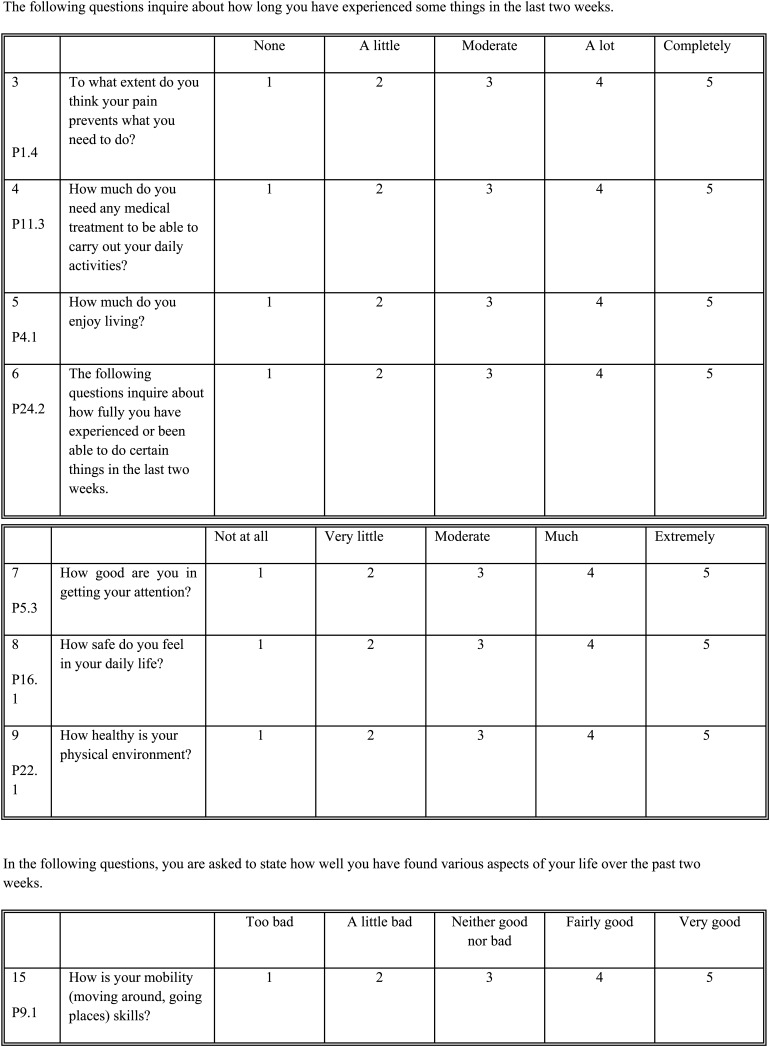

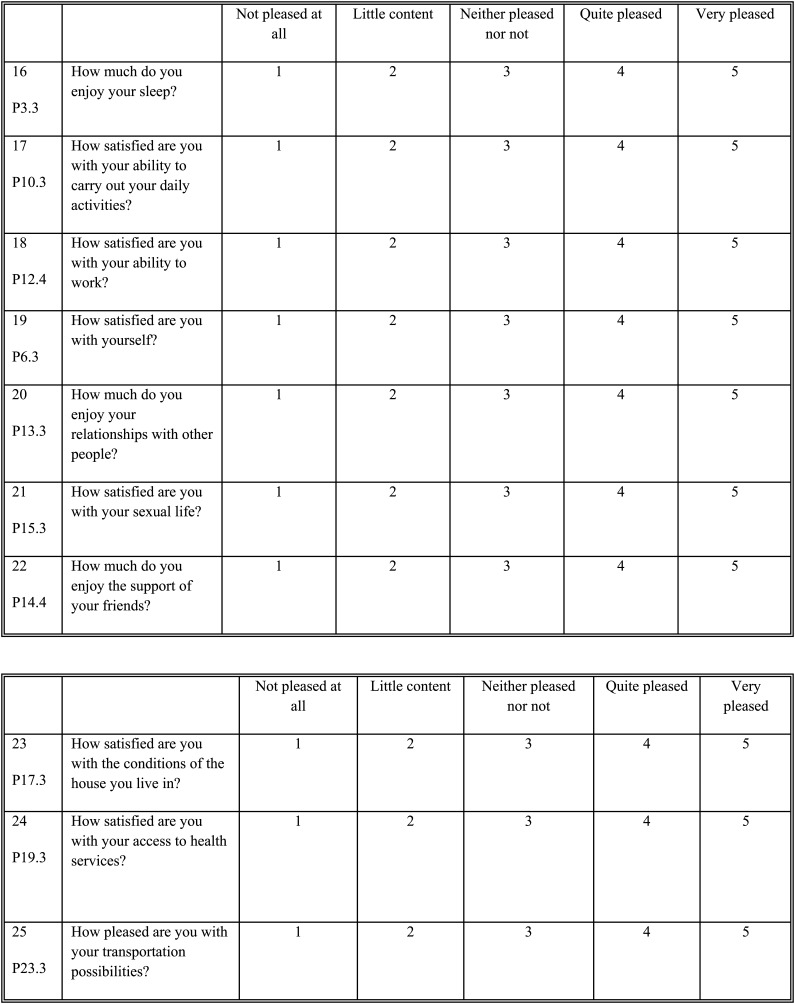

A personal information form containing demographic data and the Turkish version of the World Health Organization Quality of Life Short Form WHOQOL-Bref (TR) were used as survey questions.11 Fidaner et al.12 questionnaire was adapted to Turkish. The Turkish version consists of 27 questions along with the national extent. The scale includes 4 domains as physical (general health as 2, physical health as 7 items), psychological (6 items), social (3 items), and environment (8 items). A national (1 item) section has also been added to the adapted questionnaire.

Interpretation of the WHOQOL-Bref

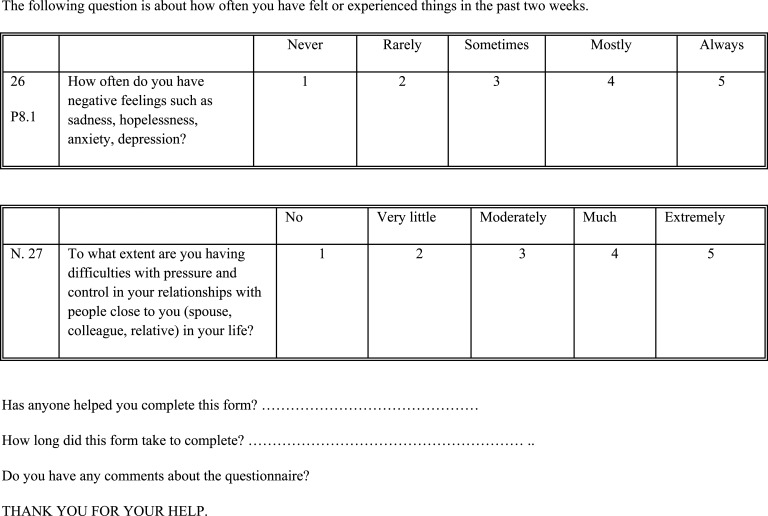

WHOQOL-Bref (TR) has a Likert-type scoring system and ranges from 1 to 5 points. The total score is obtained by multiplying these raw scores by 4 (Figure 1). Physical area evaluates an individual's ability to do daily work, addiction, vitality, fatigue, discomfort, sleep, rest, and work power. It consists of questions numbered 3, 4, 10, 15, 16, 17, and 18. The psychological area evaluates body appearances, positive or negative feelings, self-esteem, and personal beliefs. It consists of questions numbered 5, 6, 7, 11, 19, and 26. Environmental area evaluates issues related to financial resources, benefits, and accessibility in health services, the chance of acquiring knowledge and skills, leisure time, and physical environment. It consists of questions numbered 8, 9, 12, 13, 14, 23, 24, and 25. The social area evaluates the individual's social environment, communication, all interpersonal relations, and social support areas that provide emotional, material, and cognitive support to the individual when necessary. It consists of questions numbered 20, 21, and 22. The national area measures the individual's perception of social pressure. It consists of question numbered 27.

Figure 1.

WHOQOL-Bref (TR) survey.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was made with Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 21.0 (IBM SPSS Corp.; Armonk, NY, USA) program. The suitability of the variables to the normal distribution was evaluated by Kolmogorov–Smirnov, and Shapiro–Wilk tests, and it was observed that the variables did not fit the normal distribution. Comparisons between groups were made using Kruskal–Wallis, post hoc Bonferroni correction, and Mann–Whitney U-test, and results are shown as frequency, mean, standard deviation, and minimum-maximum values. Correlations of patients' subgroup scores with disease duration and number of children were evaluated using Spearman correlation analysis. A P-value of <.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Eighty-four patients were hospitalized in the specified period and 67 primary caregiver parents of them agreed to participate in the study. 97% of 67 primary caregiver parents were female (male/female = 2/65) and the mean age was 33.7 ± 7.6 years (min: 19, max: 54). 88.1% (n = 59) of the primary caregiver parents were married, 12% (n = 8) were divorced or separated. 74,6% (n = 50) were either uneducated or had a low level of education, such as primary and secondary school graduates. The number of children in the family was 2.2 ± 0.9 (min: 1, max: 5). It was found that 67.2% of the families (n = 45) lived in their own houses, and 32.8% (n = 22) were tenants. The mean disease duration of the children was 4.6 ± 4.2 years. In this study, 86.6% (n = 58) of the primary caregiver parents did not have any disease. When the total scores evaluated by WHOQOL-Bref were examined, the total score was 19.95 ± 3.30 for the physical domain, 19.95 ± 3.18 for the psychological domain, 10.11 ± 2.40 for the social domain, and 16.38 ± 2.82 for the environmental domain. In Table 1, correlations of subgroup scores of primary caregiver parents with disease duration, age, and the number of children are examined. As a result of social and cultural practice, the caregiving parents in our study were mothers, and only one father participated. Therefore, gender differences could not be studied. As a result of the analysis, the physical health score had a strong positive relationship with the psychological and social relations subgroup scores (r = 0.598, P < .001 and r = 0.775, P < .001, respectively), and there was a moderately strong positive correlation with the environmental subgroup score (r = 0.448, P < .001). The psychological subgroup score was positively correlated with the social subgroup score (r = 0.645, P < .001), and a moderately strong positive correlation was found with the environmental subgroup score (r = 0.489, P < .001). It was observed that there was a strong positive correlation (r = 0.556, P < .001) between the social relations subgroup score and the environment subgroup score. The other parameters did not have a significant relationship with each other. Table 2 shows the relationship between the subgroup scores of the patients and their marital status. Table 3 shows the relationship between the subgroup scores of the patients and their educational status. In Table 4, the relationship between the patients' subgroup scores with their home status is examined. The relationship of subgroup scores with social support intake is shown in Table 5. Significant differences in receiving social support are expressed in letters in the table. For variables with the same letter, the difference is not statistically significant. Likewise, for variables with a different letter, the difference is statistically significant. The scores of those who did not receive any social support in the physical health subgroup were found to be significantly lower than those who received moderate and high social support (P = .035 and P = .010, respectively). In the psychological subgroup, the scores of those who received much social support were significantly higher than those who received moderate and little social support and those who did not receive any social support (P = .019, P = .007, and P < .001, respectively). The scores of those who received no social support in the social relations subgroup were found to be significantly lower than those who received very little, moderate, or much social support (P = .003, P = .029, and P < .001, respectively). Besides, the scores of those who received moderate social support in the social relations subgroup were significantly lower than those who received a large amount of social support (P = .047). The scores of those who did not receive any social support in the environment sub-group were significantly lower than those who received much social support (P = .001).

Table 1.

Correlations of Patients' Subgroup Scores with Disease Duration and Number of Children

| Parameters | Psychological | Social Relations | Environment | Duration of Illness | Number of Children | Age | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Health | r | .598 | .775 | .448 | −.174 | .108 | .205 |

| P | <.001* | <.001* | <.001* | .158 | .386 | .097 | |

| Psychological | R | .645 | .489 | −.026 | .074 | .144 | |

| P | <.001* | <.001* | .835 | .550 | .246 | ||

| Social Relations | r | .556 | −.140 | .020 | .143 | ||

| P | <.001* | .259 | .873 | .247 | |||

| Environment | r | −.223 | −.159 | −.063 | |||

| P | .070 | .198 | .613 | ||||

| Duration of Illness | r | .096 | .153 | ||||

| P | .438 | .216 | |||||

| Number of Children | r | .193 | |||||

| P | .118 | ||||||

Spearman correlation analysis, * P ≤ .05.

Table 2.

Relationship of Subgroup Scores with Marital Status

| Subgroup | Marital Status | n | Mean | Standard Deviation | Minimum | Maximum | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Health | The married | 59 | 19.90 | 3.22 | 9.00 | 26.00 | .669 |

| Divorced | 4 | 19.25 | 4.72 | 16.00 | 26.00 | ||

| Living apart | 4 | 21.25 | 3.40 | 18.00 | 26.00 | ||

| Psychological | The married | 59 | 19.98 | 3.26 | 12.00 | 26.00 | .892 |

| Divorced | 4 | 20.25 | 3.78 | 17.00 | 24.00 | ||

| Living apart | 4 | 19.25 | 1.50 | 17.00 | 20.00 | ||

| Social Relations | The married | 59 | 10.24 | 2.39 | 5.00 | 15.00 | .729 |

| Divorced | 4 | 9.25 | 3.86 | 7.00 | 15.00 | ||

| Living apart | 4 | 10.00 | 1.16 | 9.00 | 11.00 | ||

| Environment | The married | 59 | 24.59 | 5.17 | 10.00 | 37.00 | .350 |

| Divorced | 4 | 22.50 | 4.93 | 17.00 | 28.00 | ||

| Living apart | 4 | 21.25 | 3.30 | 18.00 | 25.00 |

Kruskal–Wallis, post hoc Bonferroni correction.

Table 3.

. Relationship Between Subgroup Scores and Educational Status

| Subgroup | Education Status | N | Mean | Standard Deviation | Minimum | Maximum | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Health | Untutored | 7 | 21.86 | 2.48 | 19.00 | 25.00 | .082 |

| Primary-Secondary School | 43 | 19.37 | 3.43 | 9.00 | 26.00 | ||

| High school equivalent | 13 | 19.92 | 2.66 | 13.00 | 23.00 | ||

| University | 4 | 22.75 | 2.75 | 20.00 | 26.00 | ||

| Psychological | Untutored | 7 | 19.00 | 2.24 | 16.00 | 22.00 | .327 |

| Primary-Secondary School | 43 | 19.65 | 3.26 | 12.00 | 25.00 | ||

| High school equivalent | 13 | 20.92 | 3.43 | 12.00 | 26.00 | ||

| University | 4 | 21.75 | 2.36 | 20.00 | 25.00 | ||

| Social Relations | Untutored | 7 | 10.86 | 1.22 | 9.00 | 12.00 | .337 |

| Primary-Secondary School | 43 | 9.81 | 2.59 | 5.00 | 15.00 | ||

| High school equivalent | 13 | 10.46 | 2.22 | 6.00 | 15.00 | ||

| University | 4 | 11.75 | 2.06 | 9.00 | 14.00 | ||

| Environment | Untutored | 7 | 25.14 | 5.34 | 21.00 | 36.00 | .346 |

| Primary-Secondary School | 43 | 23.44 | 4.75 | 10.00 | 32.00 | ||

| High school equivalent | 13 | 25.85 | 5.49 | 18.00 | 37.00 | ||

| University | 4 | 26.50 | 6.95 | 20.00 | 36.00 |

Kruskal–Wallis, post hoc Bonferroni correction.

Table 4.

Relation of Subgroup Scores with Home Status

| Subgroup | Home Situation | N | Mean | Standard Deviation | Minimum | Maximum | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Health | Rent | 45 | 20.13 | 3.48 | 9.00 | 26.00 | .495 |

| Own house | 22 | 19.55 | 2.87 | 13.00 | 25.00 | ||

| Psychological | Rent | 45 | 19.84 | 3.13 | 14.00 | 26.00 | .687 |

| Own house | 22 | 20.18 | 3.35 | 12.00 | 25.00 | ||

| Social Relations | Rent | 45 | 10.16 | 2.26 | 5.00 | 15.00 | .967 |

| Own house | 22 | 10.18 | 2.75 | 5.00 | 15.00 | ||

| Environment | Rent | 45 | 23.67 | 5.27 | 10.00 | 36.00 | .168 |

| Own house | 22 | 25.50 | 4.56 | 19.00 | 37.00 |

Mann–Whitney U-test.

Table 5.

Relationship Between Subgroup Scores and Receiving Social Support

| Subgroup | Social Support | N | Mean | Standard Deviation | Minimum | Maximum | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Health | No | 11 | 17.18a | 4.45 | 9.00 | 25.00 | .013* |

| Very little | 23 | 20.04ab | 2.67 | 15.00 | 26.00 | ||

| Middle | 16 | 20.56b | 3.01 | 13.00 | 25.00 | ||

| Much | 16 | 21.13b | 2.66 | 16.00 | 26.00 | ||

| Psychological | No | 11 | 17.55a | 3.88 | 12.00 | 25.00 | <.001* |

| Very little | 23 | 19.61a | 2.39 | 15.00 | 23.00 | ||

| Middle | 16 | 19.69a | 2.87 | 12.00 | 23.00 | ||

| Much | 16 | 22.63b | 2.19 | 20.00 | 26.00 | ||

| Social Relations | No | 11 | 7.64a | 2.38 | 5.00 | 12.00 | <.001* |

| Very little | 23 | 10.39bc | 1.67 | 7.00 | 13.00 | ||

| Middle | 16 | 9.94c | 2.29 | 6.00 | 13.00 | ||

| Much | 16 | 11.88b | 2.09 | 9.00 | 15.00 | ||

| Environment | No | 11 | 20.46a | 5.68 | 10.00 | 32.00 | <.01* |

| Very little | 23 | 24.09ab | 5.03 | 16.00 | 36.00 | ||

| Middle | 16 | 23.88ab | 3.95 | 18.00 | 32.00 | ||

| Much | 16 | 27.75b | 3.92 | 22.00 | 37.00 |

Kruskal–Wallis, post hoc Bonferroni correction.

For variables with the same letter, the difference is not statistically significant. Likewise, for variables with a different letter, the difference is statistically significant.

* P ≤ .05.

DISCUSSION

The results of the study showed that the quality of life of primary caregiver parents of children with life-threatening or limiting diseases was affected by social relationships and receiving social support. There was no correlation with the duration of the disease, number of children, education level, age, gender of the primary caregiver parents, and parents' marital status.

When the literature is examined, health is defined as a whole, and quality of life significantly affects health. It is known that physical health is affected by psychological, social, and environmental factors. In studies conducted with mentally disabled children, when the total scores were evaluated, particularly the physical and psychological domain scores were found to be higher than the social and environmental scores, which were found similar in both child and adult caregivers.13-15 Jin-Ding et al.14 determined in their study of the caregivers of mentally disabled children in Taiwan that the quality of life area scores was lower than the healthy population but higher than the caregivers of mentally disabled adults. Similarly, in our study, physical and psychological domain scores were higher than in other domains. In our study, domain scores were found to be higher than the other studies in the literature. In our study, the fact that the field scores, especially in the physical and psychological domains, were high may be due to an emotional reason brought about by the responsibility of being a parent in the perception of usefulness and quality of life, which is an essential task in caring for their children.

Studies have shown the importance of gender, and it has been reported that the female gender has a lower quality of life.15 While studies reported that men get higher scores in the physical field, there are also studies indicating that they get higher scores in the psychological field as well.16-20 Canarslan et al.9 reported that fathers' quality of life was higher than mothers in all domains in their study with families of children with disabilities. Similarly, Coşkun et al.21 reported that they found the quality of life of mothers lower than that of fathers. In a situation where the mother who developed a neck fracture due to a traffic accident could not take care of her child, the father took over the care work. Therefore, an examination could not be made in terms of gender in our study. However, in our study, especially the gender with high physical and psychological scores were female participants. The fact that the scores were higher than in other studies may be due to providing financial support to caregiving parents, which is expressed as "care fee, " which increases the motivation of caregiving parents.

In the quality of life study of parents of children with attention-deficit and hyperactivity disorder in the literature, and it has been reported that parents over the age of 40 years, parents with insufficient income, and divorced parents have low environmental domain scores.16 Also, psychological domain scores of parents living in urban areas were lower than those of parents living in rural areas due to some stress factors.16 In our study, no difference was found between the field scores of the primary caregiver parents who had their own homes and had a better income, nor was there any difference regarding their marital status. This may be due to other factors that were not evaluated in our study.

Considering the parents' educational status, the quality of life sub-group scores of those with primary–secondary education were found to be lower in all domains. Among mothers, especially unemployed parents and low-income parents, the physical domain scores were observed to be low.16 A study conducted with patients with schizophrenia showed that as the education level increased, the burden of caregivers decreased, and the quality of life increased.22 In our study, no difference was found between education level and quality of life scores. This condition may be related to the acceptance of the mother's responsibility in our country, the holiness of motherhood, and taking care of children culturally.

Taking care of the child and fulfilling the responsibilities related to the child in a family with a life-limiting and/or threatening disease is seen as a natural socio-cultural situation in our country. When the literature is reviewed, care workers are generally confronted as a responsibility of mothers. It has been reported that mothers give up their other roles in life, participate in social activities, and decrease their social lives.23,24 It has been shown that fathers were generally more inferior to mothers in caring for these children and spending time and effort. In a study by Coşkun et al.21 comparing the mean scores of the parents in all areas of life quality, the mean scores of the mothers were lower than the fathers. The difference was statistically significant in all areas. Mothers' quality of life was shown to be affected more than fathers.25 The negative attitudes and behaviors of the parents towards their children were reported to be reduced when they had the opportunity to cope with the emotional burden and stress in the family and to relax even for a short time, especially when they were physically and mentally relieved, and even knowing the existence of someone who would support them in case of need could help and function their increased participation.25-27 In the study conducted by Meral24 with the parents of children with developmental disorders, it was reported that family social support was the variable that affected the total quality of life the most. With the increase of social support, especially mothers' perceptions of quality of life increased. In previous studies, the ability to explain and share the problem with someone was reported to increase the quality of life in all areas. The quality of life scores of those who received expert support significantly improved compared to those who did not.15,27 In our study, the lowest total score was determined as the social domain score. The physical, mental, and environmental scores of primary caregiver parents with good social support were statistically significantly higher than those who did not receive social support. The importance of social support has been clearly shown, and its effect on the quality of life has been determined, and it was thought that social environments should be created in PPB services. These findings also suggested that interviews with other family members, relatives, and friends could be activated, and primary caregiver parents should be supported in this regard.

In PPC, a small number of studies evaluate the child and family's needs, and it is crucial to evaluate the quality of life.24,28,29 Our study evaluates the needs of PPC patients and their families and shows that these patients and their families should be supported in the social field. Although some studies and questionnaires are used in the literature, it has suggested that there is much work to be done in developing shorter and more specific questionnaire items that allow the patient to be evaluated quickly and easily and meet the needs in the field of PPC.29

Study Limitations

The most important limitation of the research: the study represents only primary caregiver parents. It cannot be generalized to the whole family or other parents. In addition, outcome variables were not compared with controls, and the effect of pediatric palliative care on quality of life could not be evaluated.

CONCLUSION

This study is the first study evaluating the quality of life of primary caregiver parents who receive service in pediatric palliative care units in our country. In line with the study results, it can be said that providing mothers with “social support” has the most critical effect in increasing the quality of life and care of children with life-limiting and/or threatening diseases.

Funding Statement

The authors declared that this study has received no financial support.

Footnotes

Ethical Committee Approval: Ethical committee approval was received from the Ethics Committee of Health Science University Dr. Behçet Uz Child Disease and Surgery Training and Research Hospital (2020/07/02-426).

Informed Consent: Written informed consent was obtained from all patients' primary caregiver parents who participated in this study.

Peer Review: Externally peer-reviewed.

Author Contributions: Concept – N.H., S.A.Ö., Ü.Y.; Design - N.H., S.A.Ö., Ü.Y.; Supervision - S.A.Ö., Ü.Y., T.Ç.; Resource - N.H., S.A.Ö., Ü.,Y.; Materials - N.H., S.A.Ö., T.Ç.; Data Collection and/or Processing - N.H., S.A.Ö., T.Ç.; Analysis and/or Interpretation - N.H., S.A.Ö., T.Ç.; Literature Search - N.H., Ü.Y., S.A.Ö.; Writing - N.H., S.A.Ö., T.Ç.; Critical Reviews - N.H., S.A.Ö., Ü.Y.

Conflict of Interest: The authors have declared that no conflicts of interest exist.

References

- 1. Karahan AY, İslam S. A comparison study about caregiver burden of caregivers to physically disabled, pediatric and geriatric patients. J Marmara Univ Inst Health Sci. 2013;3:1–6.. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Eicher PS, Batshaw ML. Cerebral palsy. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1993;40(3):537–551.. 10.1016/s0031-3955(16)38549-2) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Orak OS, Sezgin S. Kanser Hastasına bakım veren Aile Bireylerinin bakım verme Yüklerinin Belirlenmesi. Psikiyatr Hemşireliği Derg. 2015;6(1):33–39.. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Özdemir KF, Şahin AZ, Küçük D. Kanserli çocuğu olan annelerin bakım verme yüklerinin belirlenmesi. Yeni Tıp Derg. 2009;26:153–158.. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Çivi S, Kutlu R, Çelik HH. Depression and factors affecting quality of life in relatives of cancer patients. Gülhane. Med J. 2011;53:248–253.. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Akandere M, Acar M, Baştuğ G. Investigating the hopelessness and life satisfaction levels of the parents with mental disabled child. Selçuk Univ Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Derg. 2009;22:23–32.. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Şıpoş R, Predescu E, Mureşan G,et al. The evaluation of family quality of life of children with autism spectrum disorder and attention deficit hyperactive disorder. Appl Med Inform. 2012;30:1–18.. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Soresi S, Nota L, Ferrari L. Considerations on supports that can increase the quality of life of parents of children with disabilities. J Policy Pract Intellect Disabil. 2007;4(4):248–251.. 10.1111/j.1741-1130.2006.00087.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Canarslan H, Ahmetoğlu E. Examining the quality of life of families with disabled children. Trakya Univ J Soc Sci. 2015;17:13–31.. [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization. Definition of palliative care. Available at: http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/print.html. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 11.The WHOQOL Group. The World Health Organization Quality of Life Assessment (WHOQOL): development and general psychometric properties. Soc Sci Med. 1998;46(12):1569–1585.. 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00009-4) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fidaner F, Fidaner C, Eser SY. WHOQOL-100 ve WHOQOL-BREF in psikometrik özellikleri. Psikiyatri Psikoloji Psikofarmakoloji;3P Dergisi, 1999;7:23–40.. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chou YC, Lin LC, Chang AL, Schalock RL. The quality of life of family caregivers of adults with intellectual disabilities in Taiwan. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil:JARID. 2007;20(3):200–210.. 10.1111/j.1468-3148.2006.00318.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lin JD, Hu J, Yen CF. Quality of life in caregivers of children and adolescents with intellectual Disabilities: use of WHOQOL-BREF survey. Res Dev Disabil. 2009;30(6):1448–1458.. 10.1016/j.ridd.2009.07.005) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tunç M. Zihinsel Engelli Çocuğa Sahip Annelerin Yaşam Kalitesini Etkileyen Etmenler: Yenimahalle İlçesi Örneği, (Yayımlanmamış yüksek lisans tezi). Ankara: Hacettepe Üniversitesi/Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Samar A, Hebatallah NE, Hend S, Mosleh I. Quality of life and family function of parents of children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. East Mediterr Health J. 2018;6:579–587.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chazan AC, Campos MR, Portekiz FB. Quality of life of medical students at the State University of Rio de Janeiro (UERJ), measured using the WHOQOL-bref: a multivariate analysis. Cien Saude Colet. 2015;20:547–556.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pagnin D, Queiroz V. Influence of burnout and sleep difficulties on quality of life among medical students. SpringerPlus. 2015;4:676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Shareef MA, AlAmodi AA, Al-Khateeb AA,et al. The interplay between academic performance and quality of life among preclinical students. BMC Med Educ. 2015;15:193. 10.1186/s12909-015-0476-1) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zhang Y, Qu B, Lun S,et al. Quality of life for medical students in China: a study using the WHOQOL-BREF. PLOS ONE. 2012;7(11):e49714. 10.1371/journal.pone.0049714) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Coşkun Y. Epilepsili çocuğa sahip anne ve babaların yaşam kalitesi (Yayınlanmamış yüksek lisans tezi). Kayseri: Erciyes Üniversitesi/Sağlık Bilimleri Enstitüsü; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Karaağaç H, Var EÇ. Investigation of the effects of care burdens on quality of life of caregivers of schizophrenia patients. Clin Psychiatry. 2019;22:16. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Duygun T, Sezgin N. The effects of stress symptoms, coping styles and perceived social support on burnout level of mentally handicapped and healthy children’s mothers. Turk J Psychol. 2003;18:37–55.. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ergüner-Tekinalp B, Akkök F. The effects of a coping skills training program on the coping skills, hopelessness, and stress levels of mothers of children with autism. Int J Adv Couns. 2004;26(3):257–269.. 10.1023/B:ADCO.0000035529.92256.0d) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Aysan F, Özben Ş. An investigation of the variables related to the quality of life of parents with disabled children. Dokuz Eylül Üniversity Buca Eğitim Fak Derg. 2007;22:1–6.. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kaner S. Engelli Çocukları Olan Ana Babaların Algıladıkları Stres, Sosyal Destek Ve Yaşam Doyumları (Yayınlanmamış Araştırma Raporu). Turkey; Ankara Üniversitesi Bilimsel Araştırma Projesi. 2004. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2017.12.484) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Meral BF. Gelişimsel Yetersizliği Olan Çocuk Annelerinin Aile Yaşam Kalitesi Algılarının İncelenmesi, (Yayınlanmamış doktora tezi). Eskişehir; Anadolu Üniversitesi Eğitim Bilimleri Enstitüsü. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Liben S, Papadatou D, Wolfe J. Paediatric palliative care: challenges and emerging ideas. Lancet. 2008;371(9615):852–864.. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61203-3) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Donnelly JP, Downing K, Cloen J,et al. Development and assessment of a measure of parent and child needs in pediatric palliative care. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;55(4):1077–1084.e2.. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2017.12.484) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Content of this journal is licensed under a

Content of this journal is licensed under a