Abstract

Background

The term “cancer” is imbued with identity signals that trigger certain assumed sociocultural responses. Clinical practice with hematological cancer patients suggests the experience of these patients may be different than that of solid tumor cancer patients.

Objective

We sought to explore the research question: How are identity experiences described and elucidated by adult hematological cancer patients?

Methods

This qualitative study was guided by interpretive description as the methodological framework.

Results

Preexisting identity labels and assumptions assigned to the overarching “cancer” diagnosis were viewed by patients as entirely inadequate to fully describe and inform their experience. Instead, findings revealed the propensity of adult hematology oncology patients to co-create and enact new identities increasingly reflective of the nonlocalized nature of their cancer subtype. Three themes that arose from the data included the unique cancer-self, the invasion of cancer opposed to self, and the personification of the cancer within self.

Conclusions

Hematology oncology patients experience and claim a postdiagnosis identity that is self-described as distinct and highly specialized, and are distinct to solid tumor patients in aspects of systemic and total consumption of the self. This uniqueness is extended to the specific hematological cancer subtype down to genetics, indicating a strong “new” sense of self.

Implications for Practice

The manner in which hematology oncology patients in this study embraced notions of transformed self and isolating uniqueness provides practitioners with a lens through which new and innovative interventions can be constructed to improve patient care and psychosocial outcomes.

KEY WORDS: Hematological cancers, Hematology, Identity, Interpretive description, Nursing, Oncology, Oncology nursing, Patient experience, Qualitative research

Cancer is a life-altering diagnosis steeped in sociocultural and historical context. The term “cancer” carries with it certain notions about signaling identity that encompass the overarching nature of a catch-all term applied to more than 100 separate diseases.1 However, clinical practice and anecdotal evidence suggest that cancer identity is sensitive to diagnostic subtypes. Identity is an expression of the person (Being) colliding with an abstract embodiment of cancer that constitutes an imperfect co-creation of an individual living immersed within society.2 In examining adolescent cancer patients, McElearney3 found that a cancer diagnosis reflected sociocultural languaging in motion. Therefore, to take the entire catalog of cancer diagnoses and lump them homogenously into “cancer” is both useful (medically and socially speaking) and potentially erroneous. This article describes a layered qualitative research study that sought to answer the overarching research question: How are identity experiences described and elucidated by adult hematological cancer patients?

Literature Review

Describing the many nuances and manifestations of cancer-as-cancer is deeply historical, extending to the Greeks and the application of the term oncos and karkinos to ulcer- and non–ulcer-forming tumors. Jan Swammerdam and Antony van Leeuwenhoek observed and described blood cells using early microscope technology in the late 1600s.4 Another hundred years passed before disorders of these cells were observed and adequately documented, thereby allowing researchers to realize that so-called cancer malignancies could exist in a variety of forms beyond traditional solid tumors. The naming of white blood cell disorders in 1847 as leukämie by German physician Rudolph Virchow5 was radical in the sense that it revolutionized thinking about cancer—not a mass, but as a malignancy of blood. Medically speaking, cancer was branched into hematological cancers and solid tumor cancers, but sociocultural languaging, symbolism, tradition, and beliefs around cancer have persevered.6

The label “cancer” immediately disturbs, and irrevocably alters, taken-for-granted assumptions about the relationship between body, self, and identity.7 The gray literature contains many examples of patients exploring issues pertaining to identity and self, but significant knowledge gaps persist in the academic literature specifically around hematology cancers, adults, and studies specific to nursing practice. Most of the research on identity work and self has occurred in the context of sociology and psychology. Symbolic interactionism methodology has been used to explore the nature of cancer embodiment from a general population of cancer patients.8,9 Similar studies focusing on the body and embodiment are in the literature and describe the corporeal experience of the body-with-cancer and body image disturbance.10,11 Park et al12 explored languaging of identity through a mixed method study that explored label frequency adopted by cancer survivors. An outcome from this study was the understanding that the patient assumed a specific label to describe their cancer journey ranging from “person who has had cancer” to “patient” to “victim,” which each label deeply saturated with deep sociocultural norms and expectations.

Several researchers have demonstrated the taking-up of a new way of thinking about self is different from identify shifts that occur in other life transformations and, in the post–cancer-diagnosis phase, this imposed shift in thinking about oneself may affect many (if not all) aspects of patient care.13,14 In addition, the lens of identity research has focused on adolescents experiencing a cancer diagnosis.14,15 Most of these academic studies, however, deal exclusively with solid tumor cancer patients, and the need for hematology-specific research was noted. Many studies have confirmed that identity and questions of social place can be significantly affected by a cancer diagnosis, which can in turn shape a person's adjustment to cancer and how they construct meaning about having the disease.12,16–29 The uptake of a cancer-specific identity by patients may provide insights about how clinicians can improve care and well-being.30 Aspects of the care environment that are affected include interactions with healthcare providers, communication, reliability and availability of support networks, treatment decisions, clinical trial participation, and survivorship issues around palliative care and end-of-life choices.

Research Design and Methods

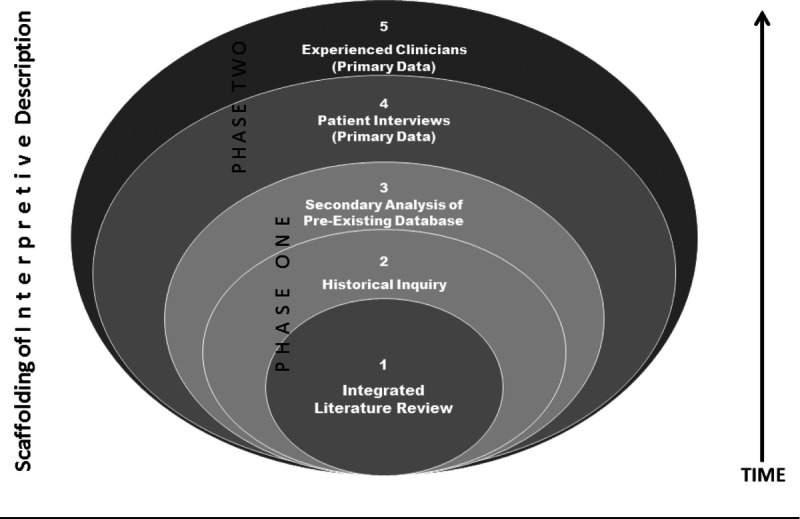

This article represents the summation of analysis and discussion that resulted from a larger layered research project focused on the experience of identity for adult hematology oncology patients, and this particular study represents primary interviews with patient participants (phase 2, layer 4; Figure).

Figure.

This figure demonstrates the interconnected nature of the 5 layers of data collection and analysis that constituted this study.

Data Collection

Informed by the integrated literature review, historical analysis, and secondary analysis of a preexisting set of interview data (phase 1, layers 1-3), we created semistructured interview guides drawing on phenomenological methods including open-ended questioning, pregnant pauses, and encouragement for expansion of answers (see Table 1). The protocol was approved by the ethics review boards of the University of British Columbia, the BC Cancer Agency, and the Vancouver Coastal Health Authority. The primary researcher was an experienced and long-time oncology nurse specializing in hematology cancers and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, and the coauthor is an oncology nurse researcher and a qualitative research expert. Convenience and purposeful sampling were used to generate a sample of 14 participants who completed the in-depth interviews. Purposeful recruitment occurred as the study progressed and constituted seeking participants with new hematological oncology diagnoses that were not yet represented. Inclusion criteria included patients who were adults (older than 18 years), spoke English, and had been given a diagnosis of a hematological cancer or cancer precursor. The goal of this study was to generate data around the hematology cancer experience, and thus the driving factor for inclusion was diagnosis. For this reason, demographic factors such as gender or age were important in that they informed the data and provided context.

Table 1.

Semistructured Interview Guide

| Preamble: Thank you for meeting with me. The purpose of this interview to explore and reflect on how a diagnosis of hematological cancer has impacted your vision of yourself. I am very interested in how your concepts around your body and self-identity have changed and appreciate thoughts on what affect this has on how you function and relate to the world. |

| Potential interview questions: |

| 1. Tell me about yourself. [Demographical: family component, career, retirement, pets, lifestyle choices, religious background, social background, geographical history, schooling] |

| 2. How was your cancer diagnosed? What kind of cancer do you have, and where are you in terms of treatment? [Note: How specific will they be about using the disease name vs “cancer” vs something else?] |

| 3. What does it mean to have a blood cancer? Have you heard of [patient's cancer type] before and in what context? |

| 4. For some cancers, such as prostate or breast, people have an identifiable body part to locate their cancer in. In a hematological cancer such as yours, it is not quite like that. How has it been for you to have a form of cancer that is not located in a specific body part? |

| 5. In your cancer experience, has having cancer had any influence on how you think or feel about yourself? In what way? Would you say your sense of yourself has changed in any way as a result of having this kind of cancer? [Note: Will they use the term “cancer” or will they reference it by its disease name, such as lymphoma?] |

| 6. What do you think about your cancer journey so far? How would you describe the changes you have noticed in how you feel about yourself? [Note: Are they talking about their cancer in terms of self (“I,” “me,”), or are they using group terms (“we,” “us”)? Ask for clarification around any group references.] |

| 7. How do you talk about [cancer type] to other people? Is it difficult for you to describe what it is like to have this type of cancer in comparison to other cancers? What kinds of questions do people ask you about [cancer type]? What do you tell them, and do you think your responses have changed over your cancer journey? |

| 8. Since your cancer diagnosis, have you changed your mind about major philosophical or lifestyle choices such as purpose of life, goals, spirituality, religion, and values? Please elaborate on these changes and how you came to them. [Note: For example, this could include if the patient has become religious or changed religions, or if they lived one way before the diagnosis and then changed to another way (such as unhealthy vs healthy, or omnivorous vs vegetarian).] |

| 9. Is there anything else you want me to know about you and your cancer journey, specifically in reference to your sense of self? |

| 10. Why did you choose to be a part of this study? |

Table 2 provides study participant characteristics. Most participants (n = 10) were between the ages of 50 and 70 years. Half of the participants had received transplantation as part of their care journey (n = 7, 2 autologous and 5 allogeneic). Half of the participants were within the first 3 years of their cancer diagnosis (n = 7). In an effort to adequately reflect hematology cancer statistics, a majority of participants had leukemia (acute myeloid leukemia [AML], acute lymphocytic leukemia, chronic myeloid leukemia [CML], or chronic lymphocytic leukemia). Other represented hematology blood cancers (including disorders described to participants as blood cancers or precancers) were lymphoma (n = 3), multiple myeloma (n = 1), myeloproliferative neoplasms (n = 1), and myelodysplastic syndrome (n = 1).

Table 2.

Demographic Qualities of the Hematology Oncology Patient Participants

| Hematological Cancer Patient Cohort (N = 14) | |

|---|---|

| Current age range, y | |

| <30 | 2 |

| 30-50 | 2 |

| 50-70 | 10 |

| Gender | |

| Male | 5 |

| Female | 9 |

| Diagnoses (primary) | |

| Multiple myeloma | 1 |

| Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma | 3 |

| Chronic leukemia (CML, CLL) | 3 |

| Acute leukemia (ALL, AML) | 5 |

| Myeloproliferative neoplasma | 1 |

| Myelodysplastic syndrome | 1 |

| Hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients | |

| Autologous | 2 |

| Allogeneic | 5 |

| N/A | 7 |

| Stage of cancer journey when interviewed | |

| Diagnosis to 1 y | 0 |

| From 1 to 3 y | 7 |

| 3-5 y | 2 |

| >5 y | 5 |

| Major day-to-day activity | At the time of diagnosis |

| At the time of the interview | |

| Retired/unemployed | 6 |

| 11 | |

| Employed full-time | 6 |

| 1 | |

| Homemaker | 1 |

| 1 | |

| Attending university | 1 |

| 1 | |

| Relationship status | |

| Divorced | 2 |

| 3 | |

| Married | 9 |

| 8 | |

| Not married (single or with partner) | 3 |

| 3 | |

| Family status | |

| No children | 4 |

| 4 | |

| School-age children | 2 |

| 2 | |

| Grandparent | 8 |

| 8 |

Abbreviations: ALL, acute lymphocytic leukemia; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; CML, chronic myeloid leukemia.

a The inclusion of a patient with myeloproliferative neoplasm was made because the patient was told by her hematologist that this was a “chronic blood cancer.”

“N/A” indicates “no transplant” or “did not receive transplant.”

Each face-to-face interview was conducted by the primary investigator and lasted 60 to 90 minutes. Written and verbal consent was obtained from each participant, and the interviews were digitally recorded. The recordings were then transcribed using a naturalistic transcription technique by both the primary researcher and a hired professional transcriptionist. One participant requested interactive written interviewing through a series of emails that allowed for responses to be clarified and elaborated on, and the final transcript constituted the content of the email communication. All interview transcripts were copied into a continuous MS Word file and into the NVivo software program to allow multiple and diverse opportunities for data analysis. Additional to individual interviews, the use of collateral materials allowed some participants to expand on the notion of self and identity in an expressive manner. This material included digitally scanned photographs, letters, scrapbooks, journals, and other items that were offered freely by the participant to illustrate ideas arising during the interview. The digital images of these materials were also housed in the NVivo database to complement data analysis.

Methodological Approach and Data Analysis

The overlying qualitative methodological scaffolding for this research was interpretive description.31 Per Thorne,31,32 interpretive description is a constructivist and naturalistic guide for inquiry specific to disciplinal epistemology, which makes it an ideal strategy for knowledge generation within applied sciences such as nursing. Using the grounded theory method of constant comparative analysis, intensive reading of the transcripts was performed to analyze and code transcribed data through generating high-level generalized categories and themes.33,34 As these themes were identified and clarified, reexamination of the transcripts ensured their basis was grounded in the data. NVivo was used to assist in sorting, indexing, and managing specific instances or references to self and identity. Deeper analysis of the transcripts constituted further rereading of the transcripts, listening to key audio moments, and continued reflection on field notes and collateral data. The iterative process of constant comparative analysis led to deeper insights and strengthened validation of research findings.35,36

Rigor and trustworthiness in this qualitative study were addressed several ways including through logical study development and systematic yet flexible sampling. In addition, participants had the ability to speak openly during interviews, and accurate transcription was performed to capture every pause and sound. Constant comparison offered ongoing attention to content and facilitated data-driven coding.

Results

Reflective analysis of the primary interview data suggested 3 themes: the unique cancer-self, the invasion of cancer opposed to self, and the personification of the cancer within self. These themes introduced multidimensional and multifaceted notions of identity experienced by the adult hematological cancer patient.

The Unique Cancer-Self

During the interviews, each participant was asked to describe in detail how they told people about their blood cancer. None used the word “cancer” by itself. Instead, all of the participants named their cancer type (ie, leukemia, T-cell lymphoma, hairy cell leukemia, CML). One participant noted, “I say lymphoma, and if people do not understand what lymphoma is, I tell them it's a blood cancer.” Another said, “We say CML all the time. We do not say cancer.” And yet another said, “this is the kind of leukemia I have…. I did not really like the label of cancer.” Another gentleman noted, “if someone does not have my same lymphoma [diffuse large B-cell], they cannot possibly identify with my experience. They just will not know me.” Another participant noted that she endlessly searched blog posts for others with the same lymphoma so that she could find out how to act, how to think, and what to hope for.

Another aspect of origination is that of the creation, or attempt to create, a unique identity based on the generalized notion of “cancer.” The participants emphasized a desire to be recognized as special (the individual with cancer) and of being a part of a particular disease (the individual having a specific blood cancer). A patient with leukemia noted, “It is also odd to go to the Leukemia Society meetings where all the leukemias are so different that I have no idea of some of their stories, and some of the things that people are talking about do not relate to my condition at all.” Another person with CML expressed a similar sentiment about support group meetings saying:

I would want to go and have somebody like me who's gone through it tell—like, kind of, you know, give their own kind of story of how they went through it and—because you have a similar blood cancer. So in a way, for—after going through it, yeah, I mean, I would hear other people's other types of blood cancer stories, but if prior, I would probably prefer to be in a leukemia group…like, people wouldn't be able to relate as well because they might have different procedures and stuff like that to go through that may not be similar to theirs, and so they can't really relate their blood cancer.

An aspect of transforming identity in this study was participants further drilling down into the generalized diagnosis to their specific type of cancer based on genetic analysis. For example, 1 older male participant with angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma explained that after he was done with active treatment, he reached out for support. Finding someone exactly like himself proved difficult. He recounted:

I need to talk to people that have been through what I've been through, and especially having what I have. Because at hockey, I talk to a guy that had the B-cell lymphoma, so I was able to talk to him, and I found that very useful. It's not the same kind. So I got ahold of her [at the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society] and I said, “Can you put me in touch with people that have my cancer, who have been through the same thing?” So she did, and I guess we're—we are such a rare breed that one guy was in New York City, one guy's in Seattle, Washington, and then there's a gal over in Coquitlam. And so I got all excited. Oh, I got some people I can talk to!

Identity within this context gave patients a distinct sense of a coming together with people they could best relate to and communicate with who would understand their “unique experience” of having a specific blood cancer. Juxtaposed alongside the context of a hyperindividualist expression of being special and specific in the world of cancer, the participant narratives revealed a tension between wanting to be part of the unique blood cancer cohort while at the same time desiring to be special in their own experience of their disease.

The Invasion of Cancer Opposed to Self

Unlike a solid tumor, a blood cancer had no place and was invisible. This language was used over and over again by participants as a way to not only talk about their cancer but to also differentiate themselves from other cancers. One participant noted, “So it's different from, like, if you have a breast cancer or something which are very visible kind of cancers.” Another explained, “If you say prostate cancer, people can envision what a prostate is, or breast cancer, people have a vision of a tumor, mass inside of a breast, and it's very easy for us to have a conversation.” A participant with AML voiced her concern that:

...you kind of feel sorry for yourself with a blood cancer because it's flowing, right? You got something here that—you know, you got a hunk on your nose, so they can take it off, they can, you know, get it out. But when it's blood, I mean, it's insidious, right? I mean, where's it hiding now, you know? Like, so that was a bit scary, about having a blood cancer.

In this example, the transmission of sentient qualities of cancer is highlighted, harkening to historic notions of cancer personification.

Another participant confirmed the differences by agreeing that “because that's the stigmatism between having a tumor, you get it removed, you know, the mass is gone.” Another participant explained the frustrating nature of having a blood cancer that did not have a “place” associated with it. He talked about troubles convincing others he was sick, saying:

When you say you have an issue, like you have a disease, how can they [society] identify? Like, there's no identification. If you say you have cancer—that was the big thing. Oh, you have a tumor. Okay, great, you can work on that tumor. But when there's nothing visible, it's like having an invisible disability, that you look fine. You look fine. Oh, you're a bit tired, yeah, but there's nothing else wrong with me that we can see. And it's really hard to explain to someone.

This statement shows an innate societal relationship to cancer as one of visibility, both of tumor (mass) and of expectations around appearance (weak, pale, and thin, for example). Social meaning remained lacking around a blood or “invisible” cancer. The systemic quality of hematological cancers led participants to wonder about the qualities that made up a blood cancer. An older woman with a myeloproliferative neoplasm contemplated the nature of her malignancy, articulating that:

I would say my cancer is in my blood. It's all over me. So yeah, I would—like you said, it was all over me. It was—it was not limited to a certain area, to a certain time of day that it would, like, hit me harder. Like, it was constant. Constant, and I was covered in it.

This same patient also thought that the systemic nature of her disease was responsible for a variety of diffuse symptoms: “It's throughout my whole body. It impacts—I get headaches where I've never had headaches before, and they come—they come without notice. Boom, you know. And it's my whole body. Sometimes my legs will not work right, sometimes my arms will not.” The nature of the cancer being everywhere gave some participants a sense that they were being consumed, echoing historic sentiment about the active agency of cancer and of being eaten alive. The cancer in their blood (cancer as blood), comprising blood permeating the body, brought a sense of self and meaning distinct in both the world of cancer and of other diseases.

The lack of a corporeal place that could be identified with a signifier seemed to be a central concern, and this also arose in the origination phase. One of the participants explained:

I was just—you know, I wasn't aware of—like, that's the thing is, like, now, having to go through the leukemia, my family didn't—like, nobody really knows blood cancers very well. Like, you know, they're expecting you have a lump on your, like, that's cancerous or you know, like, some sort of mass inside you that's, like, a tumor or—like, or they don't necessarily get the blood cancer. And so especially since it's not as prevalent, like it's not so, like, visible either, right? So—and then—yeah, so I definitely had to educate myself for one, as well as my family and friends because they weren't—like, leukemia is not talked about as much as, like, breast cancer or like, you know, other things like, you know, prostate cancers or skin cancers. Like, you tell somebody you got skin cancer, they, you know, are very, like, aware of what that is, and kind of what it entails.

Participants routinely lamented a general social dearth of understanding of blood cancers, which significantly added to their anxiety and stalled sense of self-making.

All of the participants in this study deeply felt an existential pain around the abstract, insidious, mysterious, and unseen nature of their cancer. A participant with AML highlighted the disadvantage of a blood cancer: “Yeah, because it's harder. You cannot point to something and say, ‘This is what it looks like.’” An older male participant stated, “My knowledge of blood cells had been just from, like, science class. So I knew sort of that there were different parts.” An emphasis on the cell that was the originator of the cancer (at least as understood by many participants) became a near obsession. Many asked, what is a cell? What does it look like, and what are the qualities of the cells that are cancerous? These questions drove most participants in this study to necessarily envision the cell in their mind to make the abstract real. One male participant with leukemia said:

I need[ed] to do something, so I started to visualize the—a black—like, a big, overlarge blood vessel with a lot of healthy red things and then black things, and to me the black things were the leukemia, and I started to either look at them getting devoured, blown up or shrunk or some—as a way to kind of feel like I was doing something for myself. And I—but when I spoke to other people, I don't think I really vocalized it as a blood disorder, but that's how I internalized it, was in my mind, was I was always looking at healthy red instead of not healthy black.

A participant explained that tumors can be surgically removed whereby, “that tumor is gone. Whereas the blood, like, how do you know what's happening to my blood? Like, where is any potential cancer problem? It's still there. But with a tumor, at least, it's gone. Like, the baseline is zero.” The presence of blood cancer was a value higher than zero, an abstract number that could only be measured through laboratory work and interpreted by a health professional. Abstractification of the disease into cells seemed to serve as a coping strategy but also a search strategy to envision the cancer in a way that provided meaning.

Personification of Cancer Within Self

All of the participants described an anthropomorphic process that served to personify cells into something that could be better understood as opposed to their (normal) self. These personified cells could be named, talked to, described, bargained with, manipulated, and rationalized in a way that provided a sense of coping. One participant noted:

I had heard about leukemia, but I did not know very much about it. I knew it was a disease or a cancer, but to me, I had no knowledge of diseases and cancers, and sort of the only knowledge was that some could be treated by, like—like Terry Fox [reference to a well-known Canadian athlete who had osteosarcoma], amputating his leg, stuff like that, like, where—and then other stuff, in terms of leukemia with the blood, you can't amputate blood.

One middle-aged woman with leukemia recounted that:

It's in my blood. Yeah, in my blood. Yeah. I also had a tumor. I called him Tommy. Tommy the tumor. And Tommy and Luke [sic. Leukemia] came to the party and they weren't invited, so I had to evict them, and they left. And they took their shitty friends with them.

Another participant with lymphoma described how she had envisioned the cancer like an invader in her body, having entered into her from the outside. She stated:

I almost thought of it as, like, a terrorist in my body. Like, you know—you know when you talk about—because you hear a lot of news about terror attacks, and it's about, like, something that's, like, in your body and it can go away, but then it could come back at any time, and so you're always on alert. Like, you're like—yeah, that's kind of how I pictured it, like this invader….

A lymphoma participant with 2 swollen lymph nodes in her neck confirmed that she had named the unwelcomed visitors and spoke with them regularly. She said:

We named them Hansel and Gretel because we—I understood they were from Germany, and so Hansel and Gretel became, “How are Hansel and Gretel today?” and “How are they moving in your body?” Like, it just—it really was about just visualization. It wasn't about battling, it wasn't about winning. It was about, oh, so how are they today? Where are your neutrophils, where are your red blood cell? Oh, they must be moving in, they must be getting comfortable….

In a similar way of personifying cancer, within the deconstruction phase of identity building, the data provided evidence of the realization that the cancer cells were self. One woman with leukemia said, “I was a co-creator to this.... So I always felt that I had to bathe it in light, I had to give it healing energy, I had to love it, rather than the enemy approach that just does not fit me.” Another man with leukemia related a similar feeling saying, “I really feel I worked with my cancer. Being my own body and being part of me, I always felt I had—we had to cooperate, rather than be enemies.” Therefore, deconstruction constituted a process where cancer did not erase personal identity or sense of self but, rather, initiated a process of discovery and dissection of self, which pushed participants to create meaning and a new sense of a self.

A cancer diagnosis marked a loss of control, but through the action of personification of the cancer itself (and of the cells that were malignant), responsibility for the cancer was transferred to the cancer-self. One participant explained that it was “just take a couple bad cells and start going crazy.... It's just body out of control.” For participants in this study, the powerlessness was manifest through a profound sense of isolation and an unwanted entrance into the medical system. Entering the healthcare system is one of relinquishing control over mortality and physical being to the “other.” A young man with leukemia explained, “They put in my Hickman line tube and a bunch of stuff immediately to sort of get my diagnosis under control because it was insane. But I—yeah, no, I did not really know what was going on.” Another patient with leukemia said the diagnosis had made her realize, “We do not have as much control as sometimes we maybe want to think we do over things.” One participant described how, during treatment of lymphoma, he totally lost control over his own body: “So the night sweats and chills, which is really scary thing to happen to you where you get so hot and then you are instantly frozen cold, and you are just uncontrollably shivering and shaking. You cannot stop that.” For all of the participants in this study, regaining control when feeling so isolated (physically and mentally) was expressed as finding a way to be alone with the cancer in a way that could ease anxiety and produce meaning.

Depersonalizing the cancer into a being-sans-self allowed, at least for a few of the participants, some semblance of control and an effort to form an identity beyond being a cancer patient. One participant noted, “I do not call it ‘my cancer.’ It's not mine. It occurred to me. I do not possess it. And that helps a lot.” A younger woman stated that she felt more like “herself” when she regained power over her leukemia. She did this through visualization saying, “I especially visualized my cells being healthy and being able to help me through this. I sent lots of positive thoughts and feelings to my harvested cells to be strong and well.” Another middle-aged woman with leukemia related that she decided to enact control on her cells by embracing positivity:

I want you and everybody to know that there's life after cancer. You're not dying of cancer. You're living with something that happened, and it’s not a death sentence. And just don't give up. Don't give up. It's worth not giving up. It's worth it.

Participants also explained how regaining themselves by embracing control happened when they actively engaged with the treatment process in the only ways they could: visualization and using the imagination. After abstracting the cancer into cellular components and, in some cases, personalizing these cells into a being that could be reasoned or communicated with, many participants sought to regain their self by attempting to control the cancer.

Discussion

In her work with terminally ill cancer patients, Perry37 captured the cancer experience as time based and related to the goal of finding a new normal that would signal a new identity. General social ignorance around hematological cancers generated anxiety for participants who had to search for the way they were supposed to be. Without having an immediately recognizable diagnosis, participants in this study had to struggle with meaning and creation of a personal identity. The historically and culturally embedded identity of “cancer patient” never seemed appropriate to them because they were that but so much more. Hematological cancer patients convey multiple identities arising from being a cancer patient (macro level) and beyond the writ large cancer patient (micro level). This multilayered identity is based on having cancer, having hematological cancer (systemic) in a way that is exclusively cellular. To have a blood cancer seemed to capture both the universal nature of cancer but at a broad corporeal level (systemic) that resulted from the cellular level of disease to the point of being both self (ie, cells) and nonself (cancer as cells). It is around this complex dichotomy that the participants in this study seemed to build a notion of being infiltrated at a fundamental level with cancer (ie, blood is everywhere) while developing or maintaining a hypothetical separation between the cancer cells and the “self” cells. The invisible nature of hematology cancer hindered body image considerations, which became related to signs and symptoms of disease and to treatment rather than directly attributed to the disease itself. This invisible nature of hematology cancer runs parallel to the grotesque body described for solid tumor patients by Waskul and van der Riet.9

To convey this transition from being the self (singular, noncancer) into the plural (self with cancer-selves), deep narrative around the genesis story was critical. This seemed to be not only about that pivotal diagnosis moment where the news was delivered by an oncologist but instead was more about who they were and what they were before the diagnosis moment. In each case, the participant had an innate desire to demonstrate a transition point within their tapestry of life in which the “this is who I was” transitioned to “this is who I am now.” In this way, identity was not a “thing” but rather a journey. Sontag and Edwards38 called this the entrance into the kingdom of the sick and the resumption of the label “patient.” Other factors including self-concept, self-esteem, body image, and self-perception collide to create a vastly complex amalgam of identity.

The participants in this study proudly referred to self-education about their blood cancer, which seemed linked to a longing to find that new identity (beyond patient, cancer patient, or blood cancer patient). Reflecting on these interviews, it seemed the individual could only start grappling with a new self after forming a mental construct of their specific disease. They absolutely could not comfortably relate with other patients also under the umbrella cancer or even a “blood cancer.” For this reason, the patients could never find the “right” support group or “right” patient buddy (self-perception and self-concept). The overarching label “blood cancer,” leukemia, lymphoma, or myelodysplastic syndrome was not specific enough for most patients seeking support. They complained about wanting more: more specificity, more commonality, and more likeness to self. This demonstrated an identity beyond cancer, beyond gender and all of our sociocultural labels, and seemed to reflect an intense focus on finding someone intimately and genetically similar was a response to unease with identifying with the larger cancer community. The participants noted, if they could just find that other person with Philadelphia-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia, then they would know how to “be.” This person would truly understand their identity and experience and who they were (now). This intense sense of extreme uniqueness, and of needing to find others who were similarly special to find a way of being, seemed to signify a desire to find not only community but also identity. If identity is a social phenomenon—an outward expression of an embodied self-situated within society—then participants in this research were seeking a community to co-create and enact a new identity defined specifically by their precise hematology cancer diagnosis. The irony comes, then, in that even upon finding another with a similar genetic typology of disease, the micro-nature of the community failed to enact a precise enough definition of identity that satisfied. Through knowledge-gathering about their specific disease, and embracing the abstract, cellular nature of their condition, patients sought to embrace this difference to create a new identity for themselves, and this process not only accentuated both loneliness in uniqueness but also manufactured a sense of longing for an “other” to identify with. If anything, this study has suggested that a lack of hematology cancer identity emphasizes a fluctuating and transitory quality associated with perpetual creation of self-identity.

Limitations of This Study

The literature concerning psychosocial care of the oncology patient acknowledges the role that nurses have in providing this care.39–42 This study embraces the belief that the researching patient experience can both support clinical nursing practice and strengthen positive patient outcomes. Nursing research on self-concept by Drench and colleagues43 affirmed the role self-concept and delineated associated terms such as self-esteem, identity, body image, and self-perception as important factors in chronic disorders and healthier lifestyle choices. Therefore, probing questions around identity for patients are not only appropriate, but necessary, as a central aspect of nursing practice.

Other concerns inherent for qualitative research such as transferability (or applicability) of research findings relating to external validity were considered in this study through purposeful sampling, which focused on hematology cancer subtypes over other sociodemographic factors. By focusing on the disease and the relationships, differences, and similarities of the experiences described by these patients, the intention was to build a foundation of work around identity that would be useful for further work more specifically honed. For example, with a rich description of a fundamental experience of self within hematology cancers, research studies can branch to examine identity within the context of gender, age, or ethnic considerations.

There are inherent limits arising from a single qualitative study such as this, and it can be assumed that the sample will not have captured all possible options for identity making. Despite this limitation, this study has introduced valuable knowledge around existential concerns of the hematological cancer patient in a way that can inform oncology practice and care. Of primary concern for nurses in practice is recognizing and acknowledging the person as patient. This corresponds to the idea of “being known,” whereby patients seek varying degrees of human connection with a caregiver. Thorne and colleagues44 explored this notion as an element arising from effective and ineffective communication scenarios arising from a cancer patient perspective. Nurses use communication as a means to assess, understand, and assist patients throughout their care journey, and understanding how patients might be communicating their experience of identity is an important component toward improving patient care. Simple, genuine acknowledgment of a forced identity shift resulting from a blood cancer diagnosis may ease some of the concern, fear, and anxiety over what the person is going through. Speaking to the precise location of chromosomes (eg, “I am a Philadelphia positive acute lymphocytic leukemia patient”) or being able to generate mental imagery of abstract cellular types (T-cells, B-cells, etc) provided participants the ability to assemble and claim a new self-identity.

Implications for Practice

This study supports broad findings by other researchers, which suggest that the healthcare provider might grant the patient an ability to create their own identity that they will then directly, or indirectly, communicate about.12,17,24,45,46 Asking and remembering the response to “What would you like me to call you?” is a simple yet shockingly effective strategy in removing the patient from the immediate cancer-focused environment by acknowledging an identity (name) that is beyond cancer or being a cancer patient. Research into self-concept specifically of hematology patients is useful in supporting nursing practice to support positive health behaviors such as reclaiming self-identity, educating around specific diagnostic factors that might otherwise seem abstract, and bolstering hope through community building.

This study supports the desire of participants to link with others in their diagnosis peer group. Developing relationships with others sharing similar experiences also allows patients to take cues and signals about next steps in identity formation around the blood cancer diagnosis. The literature is replete with examples of how to create, and foster, peer support mechanisms for cancer patients.47–50 Nurses, social workers, and physicians are in the exclusive position to have intimate knowledge about patients and their contemporaries in a way that highlights specific pathophysiological components of a diagnosis. By linking specific patients through personal introductions, support meeting invites, online forums, disease-specific blogs, and website recommendations, the healthcare team can facilitate a cooperative network and collaborative environment in which to socialize and make interpersonal connections.

Finally, half of the participants in this study underwent hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. The transplantation experience could potentially have impacted identity concerns, and indeed, there are studies around solid organ transplantation that suggest there is some influence. Within this study, we felt it important to represent the entire journey of hematology patients (both those who receive transplantation and those who did not). The data around identity did not seem to adequately reflect a significant deviation or discrepancy between these 2 groups.

Conclusion

Identity can be imbued with dominant sociocultural concerns around “who am I” and “who am I becoming,” and as such, identity concerns have significant implications for clinical practice. The 3 themes arising from this study included the unique cancer-self, the invasion of cancer opposed to self, and the personification of the cancer within self. The findings from this research have highlighted the importance of co-embracing existential and biological aspects of blood cancers as emphasized by patients describing their illness experience. Using a lens of identity, informed by these findings, we reflect on how nurses and other healthcare practitioners might better support hematology cancer patients.

Footnotes

This research was partially funded by a Canadian Institute for Health Research Frederick Banting and Charles Best Canada Graduate Scholarship. Publication was partially funded by Athabasca University (ARF) Publications funding.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Canadian Cancer Society . What is cancer?. https://www.cancer.ca/en/cancer-information/cancer-101/what-is-cancer/?region=qc. Accessed January 23, 2021.

- 2.Buckingham D. Introducing identity. In: Buckingham D, ed. Youth, Identity, and Digital Media. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press; 2008:1–24. [Google Scholar]

- 3.McElearney PE. Cancer's uncertain identity: a narrative and performative model for coping. Qual Inq. 2019;25(9/10):979–988. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thomas X. First contributors in the history of leukemia. World J Hematol. 2013;2(3):62–70. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Virchow R. Zur pathologischen physiologie des blutes. II. Weisses blut. [On the pathological physiology of the blood. II. White blood]. Arch Pathol Anat Phys. 1847;1:563–572. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stephens JM. Exploring Issues of Identity for Adult Hematology Oncology Patients [dissertation]. Vancouver, BC: University of British Columbia; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Charmaz K. The body, identity, and self: adapting to impairment. Sociol Q. 1995;36(4):657–680. [Google Scholar]

- 8.van der Riet P. Ethereal embodiment of cancer patients. Aust J Holist Nurs. 1999;6(2):20–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Waskul DD, van der Riet P. The abject embodiment of cancer patients: dignity, selfhood, and the grotesque body. Symb Interact. 2002;25(4):487–513. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ellingson LL, Borofka KGE. Long-term cancer survivors' everyday embodiment. Health Commun. 2020;35(2):180–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Esplen MJ, Trachtenberg L. Online interventions to address body image distress in cancer. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2020;14(1):74–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park CL, Zlateva I, Blank TO. Self-identity after cancer: "survivor", "victim", "patient", and "person with cancer". J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(suppl 2):S430–S435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hubbard G, Kidd L, Kearney N. Disrupted lives and threats to identity: the experiences of people with colorectal cancer within the first year following diagnosis. Health (London). 2010;14(2):131–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Madan-Swain A Brown RT Foster MA, et al. Identity in adolescent survivors of childhood cancer. J Pediatr Psychol. 2000;25(2):105–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jones BL, Parker-Raley J, Barczyk A. Adolescent cancer survivors: identity paradox and the need to belong. Qual Health Res. 2011;21(8):1033–1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bellizzi KM, Blank TO. Cancer-related identity and positive affect in survivors of prostate cancer. J Cancer Surviv. 2007;1(1):44–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheung SY, Delfabbro P. Are you a cancer survivor? A review on cancer identity. J Cancer Surviv. 2016;10(4):759–771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clarke C, Mccorry NK, Dempster M. The role of identity in adjustment among survivors of oesophageal cancer. J Health Psychol. 2011;16(1):99–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deimling GT, Bowman KF, Wagner LJ. Cancer survivorship and identity among long-term survivors. Cancer Invest. 2007;25(8):758–765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Wet R, Tandon A, Augustson B, Joske D, Lane H. “It is a journey of discovery”: living with myeloma. Support Care Cancer. 2019;27(7):2435–2442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gallia KS, Pines EW. Narrative identity and spirituality of African American churchwomen surviving breast cancer survivors. J Cult Divers. 2009;16(2):50–55. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Greenblatt A, Lee E. Cancer survivorship and identity: what about the role of oncology social workers? Soc Work Health Care. 2018;57(10):811–833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gurevich M, Bishop S, Bower J, Malka M, Nyhof-Young J. (Dis)embodying gender and sexuality in testicular cancer. Soc Sci Med. 2004;58(9):1597–1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller LE. “People don't understand that it is not easy being a cancer survivor”: communicating and negotiating identity throughout cancer survivorship. South Commun J. 2015;80(1):1–19. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pounders K, Mason M. Embodiment, illness, and gender: the intersected and disrupted identities of young women with breast cancer. In: Cross SNN, Ruvalcaba C, Venkatesh A, Belk RW, eds. Consumer Culture Theory. Vol. 19 of Research in Consumer Behavior. Bingley, United Kingdom: Emerald Publishing; 2018:111–122. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reynolds F, Prior S. The role of art-making in identity maintenance: case studies of people living with cancer. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2006;15(4):333–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tomaszewski EL Fickley CE Maddux L, et al. The patient perspective on living with acute myeloid leukemia. Oncol Ther. 2016;4(2):225–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Willig C. `Unlike a rock, a tree, a horse or an angel…’: reflections on the struggle for meaning through writing during the process of cancer diagnosis. J Health Psychol. 2009;14(2):181–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zebrack BJ. Cancer survivor identity and quality of life. Cancer Pract. 2000;8(5):238–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sparks L, Mittapalli K. To know or not to know: the case of communication by and with older adult Russians diagnosed with cancer. J Cross Cult Gerontol. 2004;19(4):383–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thorne S. Interpretive Description: Qualitative Research for Applied Practice. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Routledge; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thorne S, Kirkham SR, O’Flynn-Magee K. The analytic challenge in interpretive description. Int J Qual Methods. 2004;3(1):1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guba EG, Lincoln YS. Effective Evaluation: Improving the Usefulness of Evaluation Results Through Responsive and Naturalistic Approaches. New York, NY: Jossey-Bass; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic Inquiry. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thomas E, Magilvy JK. Qualitative rigor or research validity in qualitative research. J Spec Pediatr Nurs. 2011;16(2):151–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thorne SE, Hislop TG, Armstrong E-A, Oglov V. Cancer care communication: the power to harm and the power to heal? Patient Educ Couns. 2008;71(1):34–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Perry B. Through the Valley: Intimate Encounters with Grief. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Association of Nurses in Oncology; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Edwards L. In the Kingdom of the Sick: A Social History of Chronic Illness in America. New York, NY: Bloomsbury; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mahendran R Chua J Peh CX, et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and practice behaviors (KAPb) of nurses and the effectiveness of a training program in psychosocial cancer care. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22(8):2049–2056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nicholas DR. Psychosocial Care of the Adult Cancer Patient: Evidence-Based Practice in Psycho-Oncology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Regan T, Levesque JV, Lambert SD, Kelly B. A qualitative investigation of health care professionals', patients' and partners' views on psychosocial issues and related interventions for couples coping with cancer. PLoS One. 2015;10(7):e0133837. 10.1371/journal.pone.0133837. Accessed January 23, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stanton AL, Rowland JH, Ganz PA. Life after diagnosis and treatment of cancer in adulthood: contributions from psychosocial oncology research. Am Psychol. 2015;70(2):159–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Drench M, Noonan A, Sharby N, Ventura S. Psychosocial Aspects of Healthcare. 3rd ed. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thorne SE, Kuo M, Armstrong E-A, McPherson G, Harris SR, Hislop TG. ‘Being known’: patients' perspectives of the dynamics of human connection in cancer care. Psychooncology. 2005;14(10):887–898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Assing Hvidt E Hvidt NC Graven V, et al. An existential support program for people with cancer: development and qualitative evaluation. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2020;46:101768. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S146238892030048X. Accessed May 2, 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Morris BA, Lepore SJ, Wilson B, Lieberman MA, Dunn J, Chambers SK. Adopting a survivor identity after cancer in a peer support context. J Cancer Surviv. 2014;8(3):427–436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Medeiros EA Castañeda SF Gonzalez P, et al. Health-related quality of life among cancer survivors attending support groups. J Cancer Educ. 2015;30(3):421–427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Meyer A, Coroiu A, Korner A. One-to-one peer support in cancer care: a review of scholarship published between 2007 and 2014. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2015;24(3):299–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Niela-Vilén H, Axelin A, Salanterä S, Melender H-L. Internet-based peer support for parents: a systematic integrative review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2014;51(11):1524–1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang S, Bantum EO, Owen J, Bakken S, Elhadad N. Online cancer communities as informatics intervention for social support: conceptualization, characterization, and impact. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2017;24(2):451–459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]