Abstract

Despite the desire of gynecologic oncology (GO) patients to speak openly about their sexual health experience with nurses, nurses often feel ill equipped to engage in these conversations. There are very few educational interventions available to GO nurses to improve sexual health communication with patients. The purpose of this narrative review is to identify and summarize existing educational interventions in this field. A literature search conducted in three databases, for the years 2010 through 2020, identified 11 papers. The results of the review indicate a mix of nurse training modalities and explore the potential for improving this communication. Existing training programs vary in terms of mode of delivery (online or in person), length, type of instructor, learning strategies and themes addressed. Overall, however, the results show a general lack of sexual health training for nurses caring for GO patients.

Keywords: gynecologic cancer, sexual health, nurse, communication, oncology, intervention

INTRODUCTION

In Canada, gynecologic cancers (e.g., ovarian cancer, uterine cancer) account for 10.8% of all women’s cancers (Comité consultatif des statistiques canadiennes sur le cancer/Canadian Cancer Statistics Advisory Committee, 2019). These types of cancer and the associated treatments (e.g., radiation therapy, chemotherapy, surgery) can lead to sexual disorders of a physical nature (e.g., dyspareunia, loss of libido) or a psychosocial nature (e.g., changes in body image, relationship conflicts) (Vanlerenberghe et al., 2015). Sexual health, the state of biopsychosocial well-being, as defined by the World Health Organization (2020), can therefore be threatened both during and after cancer. Sexual problems related to cancer are rarely addressed by nurses with their gynecologic oncology (GO) patients (Cathcart-Rake et al., 2020). According to the Canadian Association of Nurses in Oncology (2020), it is important that nurses have the knowledge and competencies required to initiate discussions with cancer patients and support them should any sexual problems arise. However, many nurses, including those who work with GO patients, do not feel sufficiently comfortable or equipped to engage in these patient conversations (Krouwel et al., 2015). A lack of sexual health training and knowledge is one of the main obstacles to this communication (O’Connor et al., 2019). Yet many nurses are interested in advanced instruction in this area (O’Connor et al., 2019). To the best of our knowledge, only a handful of studies have described the characteristics of educational interventions developed to improve communication between nurses and GO patients about this topic. The purpose of this paper is therefore to present a narrative review of existing educational interventions to help improve sexual health communication between nurses and GO patients.

METHOD

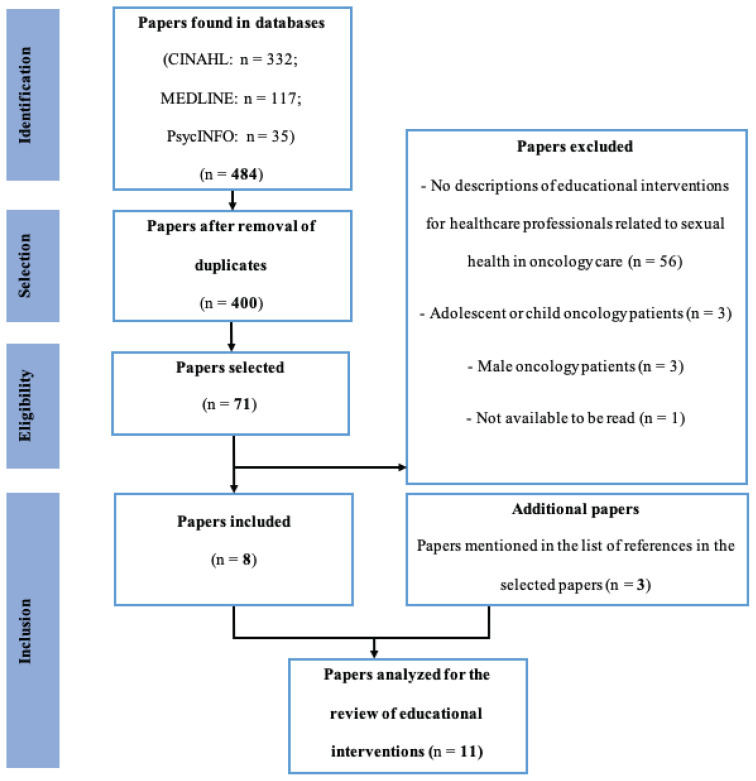

A narrative review was undertaken to provide an overview of the current state of knowledge on the issue (Snyder, 2019). A literature search was conducted by HM in three databases (CINAHL, MEDLINE and PsycINFO). The keywords used were linked to four concepts: 1) communication (e.g., discussion, counselling); 2) nursing (e.g., nurse); 3) sexual health (e.g., sex, sexual health); and 4) cancer (e.g., neoplasm). The keyword cancer was used to broaden the search and target more papers dealing with sexual health in oncology care. The inclusion criteria were: 1) research paper; 2) paper written in French or English; 3) paper published between January 1, 2010, and December 31, 2020; 4) target population: nurses working with adult female cancer patients; and 5) paper describing the details of educational interventions related to sexual health in oncology care. The exclusion criteria have been incorporated into a flow chart (Figure 1). The titles and abstracts of the papers from the initial search results were then read by HM and their eligibility assessed. The references listed in the selected papers were also reviewed by HM. Data were extracted by two of the co-authors (HM and BV) independently. Any differences were resolved by consensus of both investigators. The quality of the papers was not assessed, in that the purpose of narrative reviews is to summarize the current state of knowledge, irrespective of the quality of the selected studies (Grant & Booth, 2009). The presentation of the results is consistent with the recommendations of the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) in order to facilitate the data extraction and analysis required for a detailed description of the interventions provided (Hoffmann et al., 2014). The flow chart in Figure 1 outlines the research process.

Figure 1.

Flow Chart

RESULTS

A total of 484 papers were initially identified. This was reduced to 400 after duplicates were removed. Following a review of the titles and abstracts, this selection was narrowed down to 71 papers. These were then subjected to the stated eligibility requirements, following which eight studies remained. Further examination of the references listed in the selected studies revealed three additional papers of interest, bringing the total to 11. Of these 11, two were systematic reviews (Albers et al., 2020; Papadopoulou et al., 2019) and nine were primary studies (i.e., one randomized controlled trial, seven pre-experimental quantitative studies and one descriptive qualitative study). Table 1 outlines the specific features of these interventions, formatted as per TIDieR guidelines (e.g., population, mode of delivery, training activities, intervention providers) (Hoffmann et al., 2014).

Table 1.

Educational interventions in sexual health in oncology care

| Study | Population and oncology experience | Mode of delivery | Training activities | Length of intervention | Intervention providers and fields of expertise | Training materials |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Afiyanti et al. (2016) | - N = 46 oncology nurses - Varying experience in oncology |

Group training, in person | Interactive classes; group discussions; role playing; mentoring program | 35 hrs/5 days | Psychiatric nurse, nurse specializing in women’s health, sociologist specializing in sexuality | - Readings on sexual health in oncology care, the role of nurses, communication skills; PLISSIT model (Annon, 1976) - PowerPoint presentation |

| Jonsdottir et al. (2016) | - N = 134: 108 nurses and 26 physicians working partially in GO care - Varying experience in oncology |

Group training, in person | - Readings, group discussions, case studies, role playing related to communication and sexual issues | 2 workshops × 5 hrs + 20–30 min of group discussions | Medical team working in oncology and palliative care; lead instructors: one gynecologist and one psychotherapist | - Guide on the assessment of sexual problems and communication about sexual health; use of the BETTER sexual health communication model (Mick et al., 2004) - Website on cancer and sexual health |

| Kim & Shin (2014) | - N = 31 oncology nurses - Oncology experience between 5 months and 27.5 years |

Group training, online | Problem-based online learning, with 8 tutorials and simulations focusing on nursing practices | 1–2 hrs/week × 8 | Investigators and a scenario developer (no details on instructors’ field of expertise) | Readings, quizzes and simulations (video) related to sexual problems for oncology patients (e.g., breast cancer, endometrial cancer, colorectal cancer, prostate cancer, testicular cancer) |

| Quinn et al. (2019) * | N = 233 clinical nurses working with AYA cancer survivors | Group training, online | 8 modules with lectures, readings, case studies and group discussions on reproductive and sexual health for AYA cancer survivors and communication strategies | - 1–1.5 hrs/module - 1 module/week for 8 weeks |

Not mentioned | Each online module includes a site to review, with readings |

| Reese et al. (2019) | - N = 7: 5 physicians, 1 specialized nurse practitioner and 1 oncology medical assistant - Varying experience in oncology |

Group training, in person | - 1 theory module on the sexual health of patients with breast cancer, with explanations of the PLISSIT model (Annon, 1976) - Group discussion on challenges in sexual health in oncology care, communication strategies and sexual health referrals |

1.25 hrs: 15 min for theory and 1 hr for group discussions | Principal investigator for the study (no details on the instructors’ field of expertise) | - Fact sheets on sexual health in oncology care - Video on female sexual response - PLISSIT model (Annon, 1976) - Lists of communication strategies and referrals for sexual health services |

| Smith & Baron (2015) | N = 29 nurses working in oncology (no data on oncology units) | Group training, in person | - Lecture and interactive activity on sexual health for cancer patients (mainly breast cancer patients) and communication strategies - Group discussions and role playing |

1 hr: 20 min for the lecture + 40 min for role playing | Multidisciplinary team with 1 nurse from a breast care centre, 1 specialized clinical nurse and 2 social workers | - Slideshow on sexual problems stemming from breast cancer - Sexual health communication models: PLISSIT (Annon, 1976) and BETTER (Park et al., 2009) - Algorithm for referring patients to the appropriate sexual health resources - Information booklet and regular communications on women’s sexuality and cancer |

| Vadaparampil et al. (2016) | N = 77 clinical nurses working in AYA cancer care | Group training, online | Same activities as the study by Quinn et al. (2019) | Same length as the study by Quinn et al. (2019) | Not mentioned | Same learning materials as the study by Quinn et al. (2019) |

| Wang et al. (2015) | N = 71: 9 physicians and 62 other healthcare professionals (including nurses working with female patients with breast cancer) | Group training, in person | Didactic instruction on breast cancer and women’s sexual health, including a presentation on the Cancer, Ask, Resources, Document sexual dysfunction assessment tool, role playing to practise communication skills and discussions about clinical cases | 30–45 min | Study’s principal investigator (no details on the instructors’ field of expertise) | Cancer, Ask, Resources, Document tool to assess sexual challenges for cancer patients |

| Winterling et al. (2020) * | N = 140 nurses working with oncology patients | Group training, in person | - 1 mandatory session to watch a video on sexual challenges for AYAs with cancer; group discussions; readings on the impact of cancer on sexuality and fertility; role playing - 1 optional session to share experiences about sexual health in oncology care and participate in group discussions. |

- Mandatory session: 2 hours - Optional session: no length provided |

Instructors (no details on their fields of expertise) | - Video - Short readings on the impact of cancer on sexuality and fertility - Three role playing scenarios focusing on commonly encountered clinical situations in cancer care |

AYAs: Adolescents and young adults.

Study not included in the systematic reviews by Albers et al. (2020) and Papadopoulou et al. (2019).

Description of Educational Interventions

In terms of study location and population, most of the primary studies included in this analysis (6/9) were carried out in the United States (Quinn et al., 2019; Reese et al., 2019; Smith & Baron, 2015; Vadaparampil et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2015; Winterling et al., 2020). Some (3/9) were interdisciplinary in nature, simultaneously targeting different healthcare professionals, including nurses working in various areas of oncology. Three studies focused on specific groups of cancer patients, namely adolescent and young adult cancer survivors (Quinn et al., 2019; Vadaparampil et al., 2016) and breast cancer patients (Wang et al., 2015). Only one study (Jonsdottir et al., 2016) also included nurses specializing in GO care. None of the educational interventions analyzed focused exclusively on nurses working with GO patients.

As regards the mode of delivery and length of the interventions, many of the primary studies analyzed (6/9) examined in-person group training (Afiyanti et al., 2016; Jonsdottir et al., 2016; Reese et al., 2019; Smith & Baron, 2015; Wang et al., 2015; Winterling et al., 2020). Three online group training programs were also identified (Kim & Shin, 2014; Quinn et al., 2019; Vadaparampil et al., 2016). In most of the studies (7/9), the interventions involved sessions (between one and eight). Total training time varied in length between 30 minutes and 35 hours. The training modalities used in sexual health in oncology care are, therefore, heterogeneous.

Concerning the type and field of expertise of the intervention providers, the systematic literature review of Papadopoulou et al. (2019) notes that interventions are often delivered by more than one provider. Indeed, more than half of the primary studies analyzed (5/9) involved multi-provider interventions (Afiyanti et al., 2016; Jonsdottir et al., 2016; Kim & Shin, 2014; Smith & Baron, 2015; Winterling et al., 2020). There were several types of providers: principal investigators, interdisciplinary teams with or without a nurse, and one medical team. The providers’ fields of expertise also varied (e.g., oncology, sexology, psychiatry).

The interventions often included both theoretical and practical components. Theoretical activities including readings (Afiyanti et al., 2016; Jonsdottir et al., 2016; Quinn et al., 2019; Vadaparampil et al., 2016; Winterling et al., 2020) and instructional videos (Reese et al., 2019; Winterling et al., 2020). Among the themes addressed were reproductive health, sexual health (for breast cancer patients), the impact of cancer on sexuality and the assessment of post-cancer sexual issues. None of the interventions focused exclusively on sexual health among GO patients. As for the practical components, which involved a more active approach for participants, most used a variety of methods, such as group discussions (Afiyanti et al., 2016; Jonsdottir et al., 2016; Quinn et al., 2019; Reese et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2015; Vadaparampil et al., 2016) and role playing (Afiyanti et al., 2016; Jonsdottir et al., 2016; Smith & Baron, 2015; Wang et al., 2015; Winterling et al., 2020). The goal of these activities was essentially to have participants practise communication strategies (e.g., acquisition of communication skills). Most interventions (8/9) were multimodal, featuring a mix of training activities. A combination of role playing and group discussions was often used (Afiyanti et al., 2016; Jonsdottir et al., 2016; Smith & Baron, 2015; Wang et al., 2015; Winterling et al., 2020). Only one intervention (Kim & Shin, 2014) was based on a single learning method, i.e., problem-based online learning.

In terms of training materials, all of the interventions studied used a variety of materials to guide and support healthcare professionals in their learning. The resources used included videos (Kim & Shin, 2014; Reese et al., 2019; Winterling et al., 2020), targeted readings in sexual health (Afiyanti et al., 2016; Jonsdottir et al., 2016; Reese et al., 2019; Smith & Baron, 2015; Winterling et al., 2020), an intervention algorithm (Smith & Baron, 2015) and lists of sexual health referrals (Reese et al., 2019). Sexual health–focused communication tools were also employed in five studies, namely the Permission, Limited Information, Specific Suggestions and Intensive Therapy (PLISSIT, Annon, 1976) model (Afiyanti et al., 2016; Reese et al., 2019; Smith & Baron, 2015) and the Bringing up the topic of sexuality, Explaining, Telling, Timing, Recording (BETTER, Mick et al., 2004) model (Jonsdottir et al., 2016; Smith & Baron, 2015).

Effects of Educational Interventions

A summary of the effects of the educational interventions identified (e.g., effects on knowledge and self-efficacy) is presented in Table 2, which describes the results of the nine primary studies analyzed in this review.

Table 2.

Summary of effects of educational interventions (n = 9) in sexual health

| Effect | Knowledge | Self-efficacy | Attitudes | Communication skills | Clinical practice | Discussion frequency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Study | ||||||

| Afiyanti et al. (2016) | ↑a | ↑ | ↑ | ---- | ∅︀ | ---- |

| Jonsdottir et al. (2016) | ↑b | ---- | ---- | ---- | ↑ | ↑ |

| Kim et Shin (2014) | ↑a | ---- | ∅︀ | ---- | ∅︀ | ---- |

| Quinn et al. (2019) | ↑a | ↑ | ---- | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ |

| Reese et al. (2019) | ---- | ↑ | ---- | ---- | ---- | ↑ |

| Smith et Baron (2015) | ↑b | ↑ | ---- | ---- | ↑ | ---- |

| Vadaparampil et al. (2016) | ↑a | ↑ | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- |

| Wang et al. (2015) | ↑b | ↑ | ---- | ---- | ↑ | ↑ |

| Winterling et al. (2020) | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- |

↑: Significant improvement

↑a: Significant improvement of knowledge assessed via a questionnaire

↑b: Significant improvement of knowledge assessed via participants’ perceptions

----: Not documented; ∅︀: No improvement

It is important to note that the various effects or indicators (e.g., knowledge, self-efficacy, attitudes) were assessed using a range of instruments (e.g., questionnaire, Likert scale, survey). The validity of the instruments was documented in only two studies (Jonsdottir et al., 2016; Kim & Shin, 2014).

As illustrated in Table 2, a significant improvement in knowledge related to sexual health in oncology care was observed in four studies, based on the results of pre- and post-intervention assessments (Afiyanti et al., 2016; Kim & Shin, 2014; Quinn et al., 2019; Vadaparampil et al., 2016). In six of the nine studies, the participants’ perception of self-efficacy increased considerably (p < .05) following educational intervention (Afiyanti et al., 2016; Quinn et al., 2019; Reese et al., 2019; Smith & Baron, 2015; Vadaparampil et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2019). Furthermore, in four studies, the interventions significantly improved (p < .05) sexual health care in oncology (i.e., initiation of discussions about sexual health, sexual health referrals) (Jonsdottir et al., 2016; Quinn et al., 2019; Smith & Baron, 2015; Wang et al., 2015). Finally, even though the frequency of discussions about sexual health was shown to increase in some studies (4/9) (Jonsdottir et al., 2016; Quinn et al., 2019; Reese et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2015), the effects of the interventions on improving communication skills or changing attitudes were not documented in the majority of cases.

DISCUSSION

This narrative review provides a description of the characteristics and potential effects of educational interventions related to sexual health in cancer patients. It reveals that some interventions had not been developed exclusively for oncology nurses but instead were intended for use by a broader array of healthcare professionals (e.g., physicians). This interdisciplinary training perspective can be justified by the fact that communication about sexual dysfunction is a responsibility that is shared by multiple healthcare professionals, doctors and nurses chief among them (de Vocht et al., 2011). Given the clinical realities of nurses, however, and the development of their skills in oncology, there is a need for training programs to explicitly articulate their roles from the perspective of an interdisciplinary and collaborative approach to sexual health care. Williams et al. (2017) concluded in their qualitative study that nurses see the roles and responsibilities of interdisciplinary psychosexual health care as challenging. They indicate that there is a lack of clarity for nurses in defining and exercising their role within an interdisciplinary team. The authors therefore recommended the creation of a training program aimed first and foremost at oncology nurses to help improve attitudes, communication skills, and knowledge about sexual health.

Additionally, none of the selected studies focused exclusively on nurses working with GO patients. The themes addressed in the training programs were varied (e.g., reproductive health, impact of cancer on sexuality) and did not specifically delve into sexual issues affecting GO patients. Yet the current state of knowledge indicates that sexual problems are different for patients undergoing GO care (e.g., dyspareunia, vaginal dryness) and are often more frequent and more intense compared to other types of cancer patients (Maiorino et al., 2016). These problems are rarely discussed with healthcare professionals despite the desire and readiness of GO patients to address them (Cathcart-Rake et al., 2020). The specific features and needs of this group further emphasize the importance of developing specialized training for GO nurses so they can better support their patients.

In the studies analyzed, the mode of delivery varied from one training program to another (e.g., in person, online, group) and often entailed multiple sessions. The integrative review conducted by Bluestone et al. (2013) underscores the need for repeat training to maximize knowledge retention among healthcare professionals. All of the interventions in these studies were group interventions. They appear to have been designed from a social constructivist perspective, which guides learners to build their knowledge through interactions and sharing of ideas with their peers (Ménard & St-Pierre, 2014). It is also noteworthy that the interventions in these studies were by and large multimodal (e.g., group discussions, role playing). Group discussions are a popular strategy and the preferred professional development method for nurses (Cunningham et al., 2019). Role playing is also a technique nurses appreciate and one they feel has the power to improve care related to sexual dysfunction among oncology patients (Fitch et al., 2013). However, there is a lack of evidence as to the added value of the use of multimodal interventions compared to unimodal interventions (Squires et al., 2014). The efficacy and number of learning strategies to be adopted by healthcare professionals for professional development purposes seem to be contingent on various factors (e.g., learning culture, participants’ level of involvement) (Harvey & Kitson, 2015).

On the other hand, despite improvements in knowledge, self-efficacy and the frequency of discussions about sexual health in oncology care in many of the training programs, it is difficult to determine the exact effect of the interventions on the improvement of attitudes and communication skills in sexual health in oncology care. Active learning methods (e.g., role playing, group discussions) used in many of the identified interventions, reportedly led to an improvement in aspects such as nurses’ attitudes and communication skills (Bluestone et al., 2013). Interactive learning, which stimulates participants’ involvement and engagement, is a promising strategy for the long-term integration of learning (Lasnier, 2014). It nevertheless remains difficult, in light of the effects of the interventions analyzed in this study, to determine the most effective learning methods to improve nurses’ communication about sexual health, when caring for GO patients.

Strengths and Limitations

This narrative review provides a summary and general description of the various educational interventions aimed at improving how nurses communicate with oncology patients about sexual health. The results are complementary to those of the systematic reviews of Albers et al. (2020) and Papadopoulou et al. (2019) in that they add recent studies and build further on their work by providing detailed information about the characteristics of the interventions used. This review also highlights a lack of educational interventions in sexual health for GO nurses. Furthermore, the description of the interventions in this review, which was built around the guidelines in the TIDieR checklist (Hoffmann et al., 2014), can be used by clinicians and researchers to determine better how to plan sexual health interventions, by taking into consideration the training modalities that have already been studied and the anticipated effects.

One limitation of this narrative review is that it was restricted to three databases and to studies performed in the past ten years. Additional interventions might have been identified had other databases, grey literature or a longer publication time span been used. Moreover, the work of selecting the studies for this review was done by a single investigator. Other studies might have been found with a dual independent literature search. Considering these limitations, the results of this narrative review should be interpreted with caution.

Recommendations

This narrative review indicates the need for further research to develop, test, and assess the efficacy of innovative sexual health educational interventions aimed specifically at nurses working with GO patients. In addition, comparative studies or meta-analyses should be performed to pinpoint the best learning strategies for increasing nurses’ knowledge and comfort levels in this regard. Professional development programs focusing on the assessment of, and response to, sexual problems should be encouraged to support the work of nurses in initiating discussions on this topic (Maree & Fitch, 2019). In this respect, leading-edge training programs such as those with a clinical simulation component, may be explored (MacLean et al., 2017).

CONCLUSION

This narrative review identifies the range of educational interventions (e.g., in-person training, online training) available to nurses working with oncology patients. It also reveals a lack of interventions available to nurses specializing in GO care. It is, therefore, important to determine and develop training programs that take the realities of GO patients into account as well as the specific learning needs of nurses serving this population.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful for the financial support of the Ministère de l’Éducation et de l’Enseignement supérieur (MEES)—Universités partnership, the Faculty of Nursing at the Université de Montréal (Dr. Alice Girard Award) and the Quebec Network on Nursing Intervention Research (RRISIQ).

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest or competing interests in relation to this paper.

REFERENCES

- Afiyanti Y, Keliat B, Ruwaida I, Rachmawati IN, Agustini N. Improving quality of life on cancer patient by implementation of psychosexual health care. Jurnal Ners. 2016;11(1):7–16. doi: 10.20473/jn.V11I12016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Albers LF, Palacios LAG, Pelger RCM, Elzevier HW. Can the provision of sexual healthcare for oncology patients be improved? A literature review of educational interventions for healthcare professionals. Journal of Cancer Survivorship. 2020;14(6):858– 866. doi: 10.1007/s11764-020-00898-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Annon JS. Behavioral treatment of sexual problems: Brief therapy. Harper & Row; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Association canadienne des infirmières en oncologie. La survivance au cancer chez les adultes : Module d’autoformation pour les infirmières. 2020. https://www.cano-acio.ca/

- Bluestone J, Johnson P, Fullerton J, Carr C, Alderman J, BonTempo J. Effective in-service training design and delivery: evidence from an integrative literature review. Human Resources for Health. 2013;11(51):1–26. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-11-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cathcart-Rake E, O’Connor J, Ridgeway JL, Breitkopf CR, Kaur JS, Mitchell J, Leventakos K, Jatoi A. Patients’ perspectives and advice on how to discuss sexual orientation, gender identity, and sexual health in oncology clinics. The American Journal of Hospice & Palliative Care. 2020;37(12):1053–1061. doi: 10.1177/1049909120910084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comité consultatif des statistiques canadiennes sur le cancer. Statistiques canadiennes sur le cancer 2019. 2019. https://www.cancer.ca/~/media/cancer.ca/CW/cancer%20information/cancer%20101/Canadian%20cancer%20statistics/Canadian-Cancer-Statistics-2019-FR.pdf?la=fr-CA .

- Cunningham DE, Alexander A, Luty S, Zlotos L. CPD preferences and activities of general practitioners, registered pharmacy staff and general practice nurses in NHS Scotland—A questionnaire survey. Education for Primary Care. 2019;30(4):220–229. doi: 10.1080/14739879.2019.1617644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vocht H, Hordern A, Notter J, van de Wiel H. Stepped skills: A team approach towards communication about sexuality and intimacy in cancer and palliative care. The Australasian Medical Journal. 2011;4(11):610–619. doi: 10.4066/AMJ.2011.1047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitch MI, Beaudoin G, Johnson B. Challenges having conversations about sexuality in ambulatory settings: Part II— Health care provider perspectives. Canadian Oncology Nursing Journal. 2013;23(3):182–196. doi: 10.5737/1181912x233182188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant MJ, Booth A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information & Libraries Journal. 2009;26(2):91–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey G, Kitson A. Translating evidence into healthcare policy and practice: Single versus multi-faceted implementation strategies - is there a simple answer to a complex question? International Journal of Health Policy and Management. 2015;4(3):123–126. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2015.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I, Milne R, Perera R, Moher D, Altman DG, Barbour V, Macdonald H, Johnston M, Lamb SE, Dixon-Woods M, McCulloch P, Wyatt JC, Chan AW, Michie S. Better reporting of interventions: Template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ. 2014;348:1–12. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonsdottir JI, Zoëga S, Saevarsdottir T, Sverrisdottir A, Thorsdottir T, Einarsson GV, Gunnarsdottir S, Fridriksdottir N. Changes in attitudes, practices and barriers among oncology health care professionals regarding sexual health care: Outcomes from a 2-year educational intervention at a University Hospital. European Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2016;21:24–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2015.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J-H, Shin J-S. Effects of an online problem-based learning program on sexual health care competencies among oncology nurses: A pilot study. Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing. 2014;45(9):393–401. doi: 10.3928/00220124-20140826-02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krouwel EM, Nicolai MP, van Steijn-van Tol AQ, Putter H, Osanto S, Pelger RC, Elzevier HW. Addressing changed sexual functioning in cancer patients: A cross sectional survey among Dutch oncology nurses. European Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2015;19(6):707–715. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2015.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasnier F. Les compétences, de l’apprentissage à l’évaluation. Guérin 2014 [Google Scholar]

- MacLean S, Kelly M, Geddes F, Della P. Use of simulated patients to develop communication skills in nursing education: An integrative review. Nurse Education Today. 2017;48:90–98. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2016.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maiorino MI, Chiodini P, Bellastella G, Giugliano D, Esposito K. Sexual dysfunction in women with cancer: A systematic review with meta-analysis of studies using the Female Sexual Function Index. Endocrine. 2016;54(2):329–341. doi: 10.1007/s12020-015-0812-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maree J, Fitch MI. Parler sexualité avec des patients atteints de cancer : regard croisé Canada-Afrique de professionnels de la santé. Canadian Oncology Nursing Journal. 2019;29(1):70–76. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6516237/ [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ménard L, St-Pierre L. Se former à la pédagogie de l’enseignement supérieur. Chenelière Éducation 2014 [Google Scholar]

- Mick J, Hughes M, Cohen MZ. Using the BETTER Model to assess sexuality. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2004;8(1):84–86. doi: 10.1188/04.Cjon.84-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor SR, Connaghan J, Maguire R, Kotronoulas G, Flannagan C, Jain S, Brady N, McCaughan E. Healthcare professional perceived barriers and facilitators to discussing sexual wellbeing with patients after diagnosis of chronic illness: A mixed-methods evidence synthesis. Patient Education and Counseling. 2019;102(5):850–863. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2018.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Organisation mondiale de la Santé. Thèmes de santé Santé sexuelle. 2020. https://www.who.int/topics/sexual_health/fr/

- Papadopoulou C, Sime C, Rooney K, Kotronoulas G. Sexual health care provision in cancer nursing care: A systematic review on the state of evidence and deriving international competencies chart for cancer nurses. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2019;100:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2019.103405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park ER, Norris RL, Bober SL. Sexual health communication during cancer care: Barriers and recommendations. The Cancer Journal. 2009;15(1):74–77. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0b013e31819587dc\aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn GP, Bowman Curci M, Reich RR, Gwede CK, Meade CD, Group EEW, Vadaparampil ST. Impact of a web-based reproductive health training program: ENRICH (Educating Nurses about Reproductive Issues in Cancer Healthcare) [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural] Psycho-Oncology. 2019;28(5):1096–1101. doi: 10.1002/pon.5063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reese JB, Lepore SJ, Daly MB, Handorf E, Sorice KA, Porter LS, Tulsky JA, Beach MC. A brief intervention to enhance breast cancer clinicians’ communication about sexual health: Feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary outcomes. Psychooncology. 2019;28(4):872–879. doi: 10.1002/pon.5036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith A, Baron RH. A workshop for educating nurses to address sexual health in patients with breast cancer. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2015;19(3):248–250. doi: 10.1188/15.CJON.248-250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder H. Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines. Journal of Business Research. 2019;104:333–339. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0148296319304564 . [Google Scholar]

- Squires JE, Sullivan K, Eccles MP, Worswick J, Grimshaw JM. Are multifaceted interventions more effective than single-component interventions in changing health-care professionals’ behaviours? An overview of systematic reviews. Implementation Science. 2014;9(152):1–22. doi: 10.1186/s13012-014-0152-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vadaparampil ST, Gwede CK, Meade C, Kelvin J, Reich RR, Reinecke J, Bowman M, Sehovic I, Quinn GP. ENRICH: A promising oncology nurse training program to implement ASCO clinical practice guidelines on fertility for AYA cancer patients. Patient Education and Counseling. 2016;99(11):1907– 1910. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2016.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanlerenberghe E, Sedda AL, Ait-Kaci F. Cancers de la femme, sexualité et approche du couple. Bulletin du cancer. 2015;102:454–462. doi: 10.1016/j.bulcan.2015.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang LY, Pierdomenico A, Lefkowitz A, Brandt R. Female sexual health training for oncology providers: New Applications. Sexual Medicine. 2015;3(3):189–197. doi: 10.1002/sm2.66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams NF, Hauck YL, Bosco AM. Nurses’ perceptions of providing psychosexual care for women experiencing gynaecological cancer. European Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2017;30:35–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2017.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winterling J, Lampic C, Wettergren L. Fex-Talk: A short educational intervention intended to enhance nurses’ readiness to discuss fertility and sexuality with cancer patients. Journal of Cancer Education. 2020;35(3):538–544. doi: 10.1007/s13187-019-01493-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]