Abstract

Background

The demand for family caregiving in persons with chronic neurological conditions (CNCs) is increasing. Psychological resilience may empower and protect caregivers in their role. Thus, a synthesis of resilience evidence within this specific population is warranted.

Aim

In this systematic review we aimed to: (1) examine the origins and conceptualizations of resilience; (2) summarize current resilience measurement tools; and (3) synthesize correlates, predictors and outcomes of resilience in family caregivers of persons with CNCs.

Design

We sourced English articles published up to July 2020 across five databases using search terms involving CNCs, family caregivers and resilience.

Results

A total of 50 studies were retained. Nearly half (44%) of the studies used trait‐based resilience definitions, while about one third (36%) used process‐based definitions. Twelve different resilience scales were used, revealing mostly moderate to high‐resilience levels. Findings confirmed that resilience is related to multiple indicators of healthy functioning (e.g., quality of life, social support, positive coping), as it buffers against negative outcomes of burden and distress. Discordance relating to the interaction between resilience and demographic, sociocultural and environmental factors was apparent.

Conclusions

Incongruity remains with respect to how resilience is defined and assessed, despite consistent definitional concepts of healthy adaptation and equilibrium. The array of implications of resilience for well‐being confirms the potential for resilience to be leveraged within caregiver health promotion initiatives via policy and practice.

Patient or Public Contribution

The findings may inform future recommendations for researchers and practitioners to develop high‐quality resilience‐building interventions and programmes to better mobilize and support this vulnerable group.

Keywords: chronic neurological conditions, dementia, family caregivers, resilience, systematic review

1. INTRODUCTION

Chronic neurological conditions (CNCs) represent the leading cause of disability and the second most common cause of death worldwide. 1 Globally, it is estimated that approximately one billion people, roughly one in six of the world's total population, are currently living with a CNC. 1 Depending on their origin and aetiology, CNCs are typically divided into four groups: (1) sudden‐onset conditions (e.g., acquired brain injury [ABI], spinal cord injury [SCI], traumatic brain injury [TBI]); (2) intermittent conditions (e.g., epilepsy); (3) progressive conditions (e.g., dementia, multiple sclerosis [MS], Parkinson's disease [PD], motor neuron disease [MND] and other neurodegenerative disorders); and (4) stable with/without age‐related degeneration (e.g., polio or cerebral palsy). 2

CNCs have an enduring time course and are associated with various complex symptoms, including cognitive impairments, behavioural and psychological problems and marked physical deficits. 2 , 3 Neurological symptoms and their accompanying disability present challenges for the individual, as independence, functioning and the ability to manage life roles (e.g., employment) are limited. For instance, studies of progressive CNCs (e.g., MS and PD) have reported that the challenges associated with disability management contribute to increased unemployment rates. 4 These findings reflect limitations in the ability to perform occupational and social roles within affected populations. 4 , 5 , 6

CNC‐related disability results in many persons with these conditions requiring support from others to carry out in‐home tasks of everyday living. 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 This role is typically fulfilled by an informal caregiver—an individual responsible for providing unpaid care for family members or close friends. 11 Caregivers often experience role overload, financial strain and are unequipped to provide complex support for their care recipients. 8 , 12 The extent of this ongoing commitment can culminate in adverse mental and physical health outcomes. 12 , 13 For family caregivers of persons with CNCs, the caregiving role may contribute to increased stress, depression, anxiety, social isolation and poorer reported quality of life in comparison to the general noncaregiving population. 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 This phenomenon is referred to as caregiver burden. 17

Indeed, depleted caregiver well‐being, or burden, impacts the caregiver's ability to provide sufficient support, and is further linked to increased rates of institutionalization of people living with CNCs. 18 Nevertheless, the experience of caring for a loved one with a CNC is broad, dynamic and rarely uniform. 19 Despite facing difficulties, some caregivers experience fewer caregiving consequences, and report rewarding and fulfilling aspects of providing care (e.g., personal growth, strengthening of relationships, enhanced compassion) 20 , 21 and positive health outcomes (e.g., reduced depressive symptoms). 22 , 23 Such variability in experience suggests that not all caregivers are harrowed by burden, and that certain caregivers are better equipped to succeed in their role than others. Thus, further exploration of protective strategies that may buffer against the negative effects of burden is needed, and this review seeks to address this gap in knowledge.

To account for this variability, research in the caregiving field is becoming increasingly focused on a protective construct—resilience—which, when described briefly, denotes caregivers' ability to adapt to the physical and psychological requirements of their role. 24 , 25 This transition echoes a paradigm shift in research from a burden‐centred caregiving model to a strengths‐based model that fixates on healthy development in spite of health risks. 26 , 27 Still, there remains ample debate in the literature regarding how psychological resilience is defined. Traditionally, trait definitions are used to conceptualize resilience, whereby researchers illustrate resilience as a fixed personal attribute or inherent ability. 28 , 29 , 30 This distinction suggests that resilience is stable and unmalleable across the life span. 30 More recently, scholars have investigated the adaptive mechanisms underlying resilience, conceptualizing resilience as a dynamic process. 29 Defining resilience as an adaptive process accepts that resilience may fluctuate in the face of different challenges and stages of the life course and, in turn, is modifiable. 30 , 31 To further apprise the debate encircling resilience, Windle 29 conducted an extensive review of over 270 resilience‐related studies, generating the following definition: ‘Resilience is the process of negotiating, managing and adapting to significant sources of stress or trauma. Assets and resources within the individual, their life and environment facilitate this capacity for adaptation and “bouncing back” in the face of adversity. Across the life course, the experience of resilience will vary’.

Evaluation of interventions and policies intended to foster resilience is dependent upon reliable and validated measures. As a reflection of the ambiguity of the resilience construct, a number of resilience measures are available, with minimal progress towards a standardized measure for broad applications. 32 , 33 , 34 A methodological review of 15 resilience scales determined that the Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale (CD‐RISC), 32 the Resilience Scale for Adults (RSA) 35 and the Brief Resilience Scale (BRS) 36 obtained the highest ratings among authors, despite quality and psychometric deficiencies. 33 Most scales reflect the availability of assets that contribute to resilience (e.g., CD‐RISC) 37 or evaluate resilience as an outcome of the capacity to ‘bounce back’ (e.g., BRS). 33 , 34 Presently, few measures are available that account for the complexity of resilience from a multilevel and temporal perspective. 33 With limited access to quality scales developed for use in the general adult population, researchers lack robust evidence to inform their choice of resilience measure for differing target populations and contexts. 33

To understand caregiving challenges and the mechanisms by which resilience operates within the caregiving context, multiple studies 25 , 38 , 39 have used the Ecological Model of Resilience. 31 This model suggests that resilience operates fluidly across multiple interrelated levels including individual, community and society. 31 This model identifies resources and assets, existent within each of these levels, that may enhance caregiver risk or, alternatively, act to foster resilience. 31 More recently, O'Dwyer et al. 40 proposed a model of resilience in caregivers that conceptualizes resilience as a cyclical process, accounting for the subjective experience of adversity, with varying progressions and magnitudes.

Dissonance persists in the resilience and caregiving literature. A qualitative study among dementia caregivers found that caregivers did not agree on whether resilience was a trait or process, nor could they concur on the factors associated with resilience and its causal pathways. 40 Similarly, a systematic review outlined mainly individual factors as major components of resilience among dementia caregivers; however, the authors acknowledged that there is no single avenue to increase resilience. 41 A recent systematic review determined that resilience was associated with improved caregiver quality of life and alleviated caregiver burden in end‐of‐life and palliative care contexts, although the authors observed a lack of interest in other psychological aspects that may contribute to resilience. 42

Although the literature supports the notion that a broad range of factors may influence caregiver resilience, the lack of congruence with respect to the conceptualization and measurement of resilience within the literature presents a challenge for future research and practice. 40 Enhancing our understanding of resilience, its measures and associated factors will delineate how resilience capacities may be leveraged and monitored clinically, via intervention, programmes and service development, to better support CNC caregivers in their role. The objective of this systematic review was to synthesize the current scientific literature on the concept of resilience in CNC family caregivers. We aimed to (1) critically examine origins, theoretical conceptualizations and definitions of resilience; (2) summarize current resilience measurement tools; and (3) synthesize correlates predictors, and outcomes of resilience.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

Our protocol was registered in the PROSPERO database (CRD42020206662). This systematic review was performed in compliance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses (PRISMA) statement and reporting guidelines. 43

2.1. Search strategy and selection

A peer‐reviewed search strategy 44 was developed in consultation with a health sciences librarian (N. L.). Five databases (MEDLINE(R) [Ovid], Embase Classic+Embase [Ovid], PsycINFO, CINAHL [EBSCO] and Web of Science Core Collection) were searched to locate relevant articles published from inception to 27 July 2020. The databases were selected to source peer‐reviewed articles across a variety of disciplines including nursing, medicine, behavioural sciences and multidisciplinary fields. As a result of the degree of novelty of our search concepts, no limits to language or publication date were applied. Searches were limited to ‘human’, where possible. Reference lists were reviewed for additional publications. Relevant search terms were categorized into three distinct themes: CNCs, family caregivers and psychological resilience (see Appendix S1).

2.2. Eligibility criteria

Following a modified PICO (population, intervention, comparison, outcomes) framework, 45 we included quantitative, qualitative or mixed‐methods studies that focused on psychological resilience among community‐dwelling adult family caregivers (≥18 years old) of adults with CNCs (see Table 1). Articles that were not available in English were excluded. We excluded meta‐analyses, dissertations, systematic reviews, case reports, opinion pieces, commentaries and grey literature.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria based on a modified PICO framework 45

| PICoS | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Population |

Family caregivers of adult persons living with a CNC Community‐dwelling adults (≥18 years old) |

Formal/paid caregivers Caregivers of non‐CNC or paediatric populations |

| Phenomenon of interest | Psychological resilience in individual family CNC caregivers |

Resilience at the dyadic or community level Proxy or composite measures of resilience |

| Context |

Any country Primary informal home care |

Clinical or formal healthcare settings |

| Study type | Quantitative, qualitative, mixed‐methods original research in the English language |

Secondary research Unavailable in the English language |

Abbreviation: CNC, chronic neurological condition; PICO, population, intervention, comparison, outcomes.

2.3. Screening process

Retrieved articles were managed using Covidence online systematic review software (Veritas Health Innovation Ltd.). One author (N. L.) ran the initial search, and another (L. P.) merged the results into Covidence, where electronic data could be exported, tracked, deduplicated and managed. A two‐stage screening process was used to determine eligibility for inclusion. Articles were first screened for relevance by title and abstract by three reviewers (O. M., K. C., K. J.), with the intention of retaining only articles that involved resilience (i.e., resilience was directly referred to in the title or abstract). Any articles with ambiguous representations of resilience were conservatively retained to the next level of review. In the second stage, full texts were reviewed based on eligibility criteria. Agreement of two reviewers (O. M. and K. C.) was required for article inclusion at this stage, resulting in 100% interreviewer agreement. Discrepancies between reviewers were resolved by the last author (L. P.).

2.4. Data extraction

Data were extracted using an Excel template developed by the research team. The following parameters were extracted: (a) study information (i.e., author, year, country, purpose, design, recruitment setting and sample size); (b) participant characteristics (i.e., age, gender); (c) caregiving context variables (relationship with care recipient, CNC, participant eligibility criteria); and (d) resilience components (operationalized definition of resilience, source of definition, measure of resilience, resilience score, resilience‐related results). Two independent reviewers completed the data extraction (O. M. and K. C.). Once both reviewers completed their respective extractions, the results were compared, and any discrepancies were discussed in detail and clarified in a consensus meeting. If consensus among reviewers was not reached, the final decision was made by the last author (L. P.). The authors of three (6%) studies were contacted for missing resilience score data. 46 , 47 , 48 Of those contacted, we received additional data from the authors of one study. 47

3. RESULTS

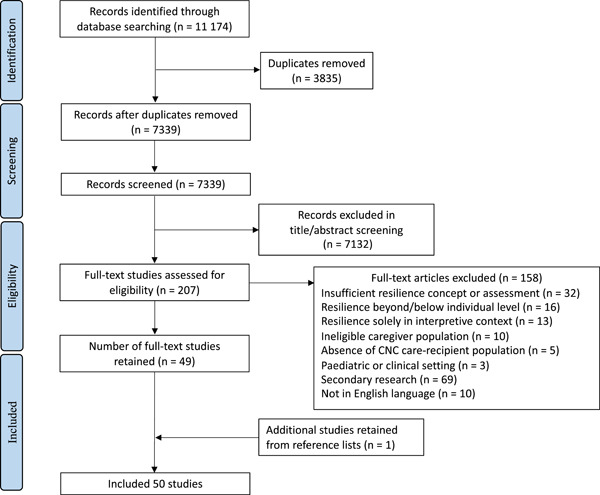

Following the removal of duplicates (n = 3835), 7339 studies remained to be screened (Figure 1). The title and abstracts of these studies were screened, and 207 articles were subjected to full‐text screening. Following our review, 49 publications fulfilled the inclusion criteria. An additional publication was located by reviewing the reference lists of included articles. Thus, a total of 50 publications were retained. Articles reporting data from the same participant population at different time points are reported together.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of the study selection process. CNC, chronic neurological condition

3.1. Study characteristics and caregiver sample demographics

3.1.1. Study characteristics

Most (n = 46, 92%) studies were published within the last 10 years of conducting our search (i.e., during or after the year 2010). The majority of studies originated from Europe (n = 20, 40%) 38 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 , 54 , 55 , 56 , 57 , 58 , 59 , 60 , 61 , 62 , 63 , 64 , 65 and North America (n = 20, 40%), 19 , 25 , 46 , 66 , 67 , 68 , 69 , 70 , 71 , 72 , 73 , 74 , 75 , 76 , 77 , 78 , 79 , 80 , 81 , 82 followed by Asia (n = 4, 8%), 83 , 84 , 85 , 86 South America (n = 4, 8%) 87 , 88 , 89 , 90 and Australia (n = 2, 4%). 91 , 92 Across studies, the sample size ranged between 18 71 and 691. 80 , 81 Most of the quantitative studies were cross‐sectional (n = 34, 68%) or longitudinal designs (n = 1, 2%). Only four studies (8%) were intervention‐based. 70 , 75 , 84 , 85 Seven studies (14%) used a qualitative design involving semi‐structured interviews, 38 , 52 , 53 , 73 , 74 open‐ended questionnaires 19 or content analysis. 25 Four (8%) studies adopted a mixed‐methods design. 54 , 71 , 72 , 86

3.1.2. Caregiver demographics

A total of 5992 caregivers were sampled across studies. As shown in Table 2, the mean age of the caregivers ranged between 40 77 and 76 78 years. Most caregivers were women (55%–97%). 68 , 87 The majority of the caregivers were cohabitating spouses/partners (n = 2898, 48%), followed by offspring or children (n = 1674, 28%), parents (n = 353, 6%), siblings (n = 167, 3%), grandchildren (n = 58, 1%) or undisclosed ‘other’ (n = 838, 14%).

Table 2.

Study and caregiver sample characteristics in the 50 studies included in the review

| Author (year) | Country | Sample size (n) | Age, mean (SD) | Gender (% F) | Relationship to care‐recipient (%) | CNC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Castellano‐Tejedor and Lusilla‐Palacios (2017) 58 | Spain | 75 | 48.55 (12.55) | 84.0 |

Spouse/partner: 44 Offspring: 39 Sibling: 8 Parent: 5 Other: 3 |

SCI |

| Senturk et al. (2018) 59 | Turkey | 103 |

56.5 (9.91) |

85.4 |

Spouse: 36.9 Mother: 42.7 Father: 16.5 Relative: 3.9 |

Dementia |

| Garity (1997) 76 | USA | 76 |

61.5 (14.1) |

71.0 |

Spouse: 43 Offspring: 42 Sister: 8 Grandchild: 7 |

AD |

| Scholten et al. (2020) 60 | The Netherlands | 157 |

55.5 (12.4) |

61.8 |

Partner: 78.3 Parent: 8.9 Child: 7 Other: 5.8 |

SCI, ABI |

| Brickell et al. (2020) 77 | USA | 346 |

40.6 (9.3) |

96.2 |

Spouse/partner: 91 Other: 9 |

TBI |

| Simpson and Jones (2013) 91 | Australia |

61 (TBI: 30 SCI: 31) |

ABI: 54 (12) SCI: 50 (14) | 90.2 |

Parent: 39.4 Spouse: 54.1 Other: 6.6 |

TBI, SCI |

| Cousins et al. (2013) 61 | UK | 27 | NIV | 74.0 |

Spouse/partner: 40.1 Offspring: 7.4 Sibling: 11.1 Parent: 3.7 |

MND |

| 57.56 (11.70) | ||||||

| Declined NIV | ||||||

| 65.88 (10.45) | ||||||

| Elnasseh et al. (2016) 62 | Spain | 105 | 57.71 (13.35) | 74.3 | NR | Dementia |

| Ertl et al. (2019) 63 | Spain | 95 |

51.1 (13.85) |

78.0 |

Spouse/partner: 60 Offspring: 26.3 Sibling: 9.5 Parent: 4.2 |

PD |

| Fitzpatrick and Vacha‐Haase (2010) 78 | USA | 30 |

76.4 (6.0) |

70.0 | Spouse: 100 | Dementia (AD or other) |

| Kimura et al. (2019) 87 | Brazil | 43 |

51.1 (15.2) |

97.1 |

Spouse: 48.8 Offspring: 34.9 Sibling: 9.3 Other: 7 |

Young‐onset AD |

| Ruisoto et al. (2020) 64 | Spain | 283 | 59.93 (14.56) | 65.7 |

Offspring: 55.5 Spouse: 40.6 Other: 3.9 |

Dementia |

| Scott (2013) 46 | USA | 110 |

63 (11) |

80.2 |

Spouse: 36 Offspring: 59.5 Other: 4 |

AD |

| Pessotti et al. (2018) 88 | Brazil | 50 |

54.7 (11.1) |

88.0 |

Wives: 32 Daughters: 54 |

Dementia |

| Wilks and Vonk (2008) 79 | USA | 304 |

63 (13.5) |

77.0 |

Spouse: 43 Offspring: 39 Friend: 4 Other: 14 |

AD |

| Rosa et al. (2020) 90 | Brazil | 106 |

57.9 (13.75) |

79.2 |

Spouse: 37.7 Offspring: 52.8 Other: 9.4 |

AD |

| Chan et al. (2019) 83 | Malaysia | 207 |

50.4 (14.5) |

79.7 | Spouse: 16.4 | AD |

| Offspring: 61.4 | ||||||

| Other: 17.4 | ||||||

| Unknown: 4.8 | ||||||

| Dias et al. (2016) 89 | Brazil | 58 |

62.5 (13.44) |

79.3 |

Spouse: 44.8 Offspring: 51.7 Other: 3.4 |

Dementia (AD, vascular dementia, mixed dementia) |

| Serra et al. (2018) 65 | Spain | 326 |

59.9 (14.6) |

65.7 |

Spouse: 55.5 Offspring: 40.6 Other: 3.9 |

Dementia |

| Sutter et al. (2016) 47 | Spain | 127 |

57.14 (13.01) |

77.2 |

Spouse/partner: 17.8 Offspring: 22.2 Sibling: 60 |

Dementia |

| Jones et al. (2018, 2019) 48 | UK | 80 | NR | 73.8 |

Spouse: 65 Other: 35 |

Dementia |

| Jones, Killett et al. (2019) 55 ; Jones, Woodward et al. (2019) 49 | UK | 110 | NR | 66.0 |

Spouse: 62 Other: 38 |

Dementia |

| Wilks et al. (2011, 2018) 80 | USA | 691 | 61a | 79.8 |

Spouse: 16.7 Offspring: 51.3 Sibling: 4.4 Grandchild: 6.6 Friend: 3.8 Other: 16.9 |

AD |

| Wilks (2008) 66 ; Wilks and Croom (2008) 82 | USA | 229 | 45a | 90.0 |

Spouse: 30 Offspring: 49 Friend: 8 Grandchild: 5 Other: 8 |

AD |

| Anderson et al. (2019) 92 | Australia | 131 |

58.2 (14.3) |

80.9 |

Spouse: 45 Parent: 44.3 Other: 10.7 |

TBI |

| Hayas et al. (2015) 50 | Spain | 237 |

55.6 (12.4) |

77.6 |

Spouse: 47.3 Parent: 28.3 Child: 14.8 Sibling: 7.2 Other: 2.5 |

ABI |

| Vatter et al. (2018, 2020) 56 , 57 | UK | 136 |

69.44 (7.62) |

85.3 |

Married: 94.9 Cohabitating: 5.1 |

PD‐related dementia |

| Ledbetter et al. (2020) 67 | USA | 312 |

42.3 (11.9) |

80.8 | Spouse/partner: 100 | SCI |

| O'Rourke et al. (2010) 68 | Canada | 105 |

69.59 (8.66) |

55.0 | Spouse: 100 | AD |

| Rivera‐Navarro et al. (2018) 51 | Spain | 326 |

60.1 (14.5) |

67.2 |

Spouse: 41.4 Offspring: 52.5 Son‐/daughter‐in‐law: 2.5 Sibling: 0.9 Other: 2.5 |

Dementia |

| Tyler et al. (2020) 69 | USA | 253 | 59.92 (14.68) | 73.1 |

Spouse: 68.8 Parent: 21.7 Friend: 1.2 Sibling: 4.3 Cousin: 0.4 Aunt/uncle: 1.2 Other: 2.4 |

PD |

| Ghaffari et al. (2019) 84 | Iran | 54 |

Control 43.4 (6.3) Intervention 42.6 (6.2) |

Control 70.0 Intervention 88.0 |

Control Spouse: 20 Offspring: 80 Intervention Spouse: 12 Offspring: 88 |

AD |

| Lavretsky et al. (2010) 75 | USA | 40 |

Control 63.3 (13.4) Intervention 60 (9.4) |

Control 55.0 Intervention 75.0 |

Spouse: 37.5 Offspring: 62.5 |

AD |

| MacCourt et al. (2017) 70 | Canada | 200 | 64.4a | 79.0 |

Spouse: 61.9 Parent: 23 Other: 5.1 |

Dementia/AD |

| Pandya (2019)b , 85 | India | 96/96 (C/I) |

Control 52.5 (10.67) Intervention 52.68 (11.03) |

Control 86.5 Intervention 81.3 |

Spouse: 54.6 Offspring: 23.3 Son/daughter in‐law: 22.1 |

AD |

| Maneewat et al. (2016) 86 | Thailand | 150 | NR | NR | NR | Dementia |

| Bull (2014) 71 | USA | 18 |

64 (14.1) |

67.0 |

Spouse: 39 Offspring: 61 |

Dementia |

| Kidd et al. (2011) 72 | USA | 20 | 60.2a | 85.0 | Spouse: 100 | Dementia |

| Bekhet and Avery (2018) 19 | USA | 80 |

57.0 (15.6) |

90.0 | NR | Dementia |

| Roberts and Struckmeyer (2018) 73 | USA | 33 | NR | 87.9 |

Spouse: 42.4 Parent: 48.5 Offspring: 6.1 Sibling: 3 |

Dementia |

| Han et al. (2019) 25 | USA | 39 | 62 (7.4) | 76.9 | Spouse/partner: 7.7 | AD and related dementias |

| Offspring: 82.1 | ||||||

| Other: 10.2 | ||||||

| Liu et al. (2020) 74 | USA | 27 | 69.04 (10.51) | 77.8 | Spouse: 46.2 | Dementia |

| Offspring: 50 | ||||||

| Sibling: 3.85 | ||||||

| Donnellan et al. (2015, 2017, 2019) 38 | UK | 23 |

75 (7.46) |

69.6 | Spouse: 100 | Dementia |

Abbreviations: ABI, acquired brain injury; AD, Alzheimer's disease; CNC, chronic neurological condition; MND, motor neuron disease; NIV, noninvasive ventilation; NR, not reported; PD, Parkinson's disease; SCI, spinal cord injury; TBI, traumatic brain injury.

SD for the total sample not reported.

Pretest values reported.

3.1.3. Chronic neurological condition

The most commonly reported CNCs were progressive conditions (n = 43, 86%). A substantial proportion (n = 37, 74%) of the progressive conditions studied were dementia, Alzheimer's disease or other dementias (e.g., mixed, vascular). The remaining progressive conditions were PD (n = 2, 4%), 63 , 69 PD‐related dementia (n = 2, 4%) 56 , 57 and MND (n = 1, 2%). 61 Few studies (n = 7, 14%) included sudden‐onset conditions including SCI, 58 , 60 , 67 , 91 ABI 50 , 60 and TBI. 77 , 91 , 92 No studies included intermittent (e.g., epilepsy) or stable (e.g., polio, cerebral palsy) conditions.

3.2. Conceptualization, measurement and levels of resilience

3.2.1. Resilience conceptualizations

Certain (n = 7, 14%) studies minimally or unclearly defined resilience, 75 , 85 briefly presenting it as a general protective psychological factor, 51 , 60 or simply in relation to stress 56 , 57 or positive coping (see Table 3). 47 The remaining articles (n = 43, 86%) offered some type of a theoretical definition of resilience. When broadly discussed, the vast majority of included articles incorporated the idea of healthy adaptation into their conceptualizations of resilience. Further, most referred to preserving some level of well‐being, equilibrium or positive functioning in the face of adversity. Many (n = 13, 26%) studies referred to the significance of internal and external resources, protective factors, and relational and situational contexts in facilitating resilience development. 38 , 48 , 52 , 53 , 54 , 55 , 59 , 65 , 67 , 74 , 78 , 82 , 92 For instance, self‐compassion was an internal resource conceptually linked to resilience. 54

Table 3.

Operationalized definitions of resilience by article included in the review

| Author (year) | Resilience model | Operationalized definition of resilience |

|---|---|---|

| Quantitative, cross‐sectional or longitudinal studies (n = 35) | ||

| Castellano‐Tejedor and Lusilla‐Palacios (2017) 58 | Hybrid (trait–process) | A range of thoughts, feelings and behaviours and a dynamic process encompassing positive adaptation within the context of significant adversity; it is also considered a personality characteristic that moderates the negative effects of stress and promotes adaptation |

| Senturk et al. (2018) 59 | Trait | The ability of a person to successfully overcome and adapt to negative conditions despite the difficult circumstances; satisfaction with social network and social support, psychological well‐being, strength and a healthy life |

| Garity (1997) 76 | Trait | A personality trait or characteristic that moderates the negative effects of stress and promotes adaptation; persons who display courage or adaptability in the face of adversity |

| Scholten et al. (2020) 60 | Trait | Psychological factor related to psychological distress |

| Brickell et al. (2020) 77 | Process | Core concepts of adversity and personal adaptation; the concept of personal adaptation allows for resilience to be a flexible rather than fixed process and may be modified over time as the individual adapts |

| Simpson and Jones (2013) 91 | Process | A multidimensional construct constituting a range of thoughts, feelings and behaviours; a dynamic process encompassing positive adaptation within the context of significant adversity |

| Cousins et al. (2013) 61 | Trait | The characteristic way in which people approach and cope with life events, described in terms of three related tendencies: commitment, where behaviour is influenced by the meaning and purpose seen in a situation; control, the ability to make one's own choices in a situation; and challenge, the tendency to perceive life events as opportunities for development, rather than threats |

| Elnasseh et al. (2016) 62 | Process | A psychological phenomenon characterized by effective coping and adaptation in the face of loss, hardship or adversity; a protective factor; and personal strength |

| Ertl et al. (2019) 63 | Trait | An individual's ability to adapt, persevere and maintain emotional equilibrium despite adversity; psychological strength |

| Fitzpatrick and Vacha‐Haase (2010) 78 | Hybrid (trait–process) | Resilient individuals are able to confront a crisis successfully and engage in positive behaviour to adjust coping strategies for effective adaptation to the situation; a multidimensional construct involving not only psychological traits but also the individual's ability to use external sources to facilitate coping |

| Kimura et al. (2019) 87 | Hybrid (trait–process) | A dynamic and complex construct that involves the interaction of both risk and protective factors, internal and external to the individual, that act to modify the effects of an adverse life event; a protective factor that enhances health by buffering the deleterious effects of stress |

| Ruisoto et al. (2020) 64 | Hybrid (trait–process) | A control‐related intrapsychic variable that may promote a more successful adaptation to care demands; personality trait, but broader approaches underline the importance of relational and situational contexts for resilience behaviour |

| Scott (2013) 46 | Process | A characteristic or developmental process in individuals that, when activated, aids in thwarting the effects of social conditions that can lead to impaired daily functioning |

| Pessotti et al. (2018) 88 | Trait | One's capacity for successful adaptation when faced with the stress of adversity; not invulnerability to stress, but, rather, the ability to recover from negative events |

| Wilks and Vonk (2008) 79 | Trait | Implies a track record of successful adaptation in the individual who has been exposed to stressful life events, and an expectation of continued low susceptibility to future stressors; reflects an outcome strength, that is, the ability to recover from the stressor successfully |

| Rosa et al. (2020) 90 | Trait | One's capacity for successful adaptation when faced with the stress of adversity |

| Chan et al. (2019) 83 | Trait | Successful adaptation and competence that results in effective functioning in the face of stressful situations |

| Dias et al. (2016) 89 | Trait | One's capacity for successful adaptation when faced with the stress of adversity; facilitates adaptation by enabling one to identify what is stressful, realistically appraise one's capacity for action and solve problems effectively; considered as a personality characteristic |

| Serra et al. (2018) 65 | Trait | The abilities and personal resources of individuals that allows them to successfully deal with adverse situations |

| Sutter et al. (2016) 47 | NR | Relates to positive coping strategies, lower depressive symptoms and positive psychosocial variables |

| Jones et al. (2018) 48 | Process | The process of adaptation to distress and is associated with the caregiver's ability to draw on personal assets in combination with the availability, suitability and use of community and societal resources |

| Jones, Killett et al. (2019a) 55 ; Jones, Woodward et al. (2019b) 49 | Process | 2019a |

| Multidimensional concept that embodies personal qualities and external support systems that enable one to thrive in the face of adversity | ||

| Process | 2019b | |

| Positive adaptation to stressful situations and encompasses both individual characteristics and extrinsic factors, including social support from their family and the wider community | ||

| Wilks et al. (2011, 2018) 80 | Trait | 2011 |

| Implies adaptational success; a characteristic of psychological well‐being, referring to the ability to recover from negative life events, leading to hope and expectation of success in the face of future adversity; reflects postadversity strength boosted by protective factors | ||

| Trait | 2018 | |

| The positive role of the ubiquitous phenomenon of individual difference in people's responses to stress and adversity reflects an outcome of strength, recovery and hardiness postadversity | ||

| Wilks (2008a) 66 ; Wilks and Croom (2008b) 82 | Trait | 2008a |

| An adaptational outcome success; suggests overcoming the odds, adapting to high risk (adversity) and recovering from adversity by adjusting successfully to negative life events | ||

| Trait | 2008b | |

| Viewed as being augmented by protective factors and defined as a psychological phenomenon referring to effective coping and adaptation although faced with loss, hardship or adversity | ||

| Anderson et al. (2019) 92 | Hybrid (trait–process) | The ability to adapt in the face of tragedy, trauma, adversity, hardship and ongoing significant life stressors; a multidimensional construct comprising a mix of personal skills and attributes, social competence, social resources and spirituality, which may be associated with reductions in morbidity and increased positive well‐being |

| Hayas et al. (2015) 50 | Process | The process of positive adaptation in the face of adversity, trauma, tragedy, threats or significant sources of stress; a dynamic process in which psychological, social, environmental and biological factors interact to enable an individual at any stage of life to develop, maintain or regain his or her mental health despite exposure to adversity |

| Vatter et al. (2018, 2020) 56 , 57 | Trait | The ability to bounce back from stress |

| Ledbetter et al. (2020) 67 | Hybrid (trait–process) | An individual's successful adaption to adversity or stressful experiences, informed by both elements of their personality and the contextual, ongoing situation in which adversity occurs, but is frequently measured at a discrete point in time; a combination of both personality and situational factors that inform how individuals cope with stress and adversity |

| O'Rourke et al. (2010) 68 | Process | The process of adaptation in response to adversity, threats or significant stress such as the diagnosis and care of a family member with a major illness |

| Rivera‐Navarro et al. (2018) 51 | Trait | Protective factor |

| Tyler et al. (2020) 69 | Process | The process of negotiating, managing and adapting to significant sources of stress or trauma; assets and resources within the individual, their life and environment facilitate this capacity for adaptation and ‘bouncing back’ in the face of adversity |

| Quantitative, intervention studies (n = 4) | ||

| Ghaffari et al. (2019) 84 | Process | Describes a situation in which a caregiver improves social performance and overcome difficulties, despite experiencing high mental pressure |

| Lavretsky et al. (2010) 75 | NR | NR |

| MacCourt et al. (2017) 70 | Trait | A positive personality characteristic that enhances individual adaptation, preserving balance and harmony |

| Pandya (2019)85 | NR | NR |

| Mixed‐methods studies (n = 4) | ||

| Maneewat et al. (2016) 86 | Process | A process of growth and adaption with a multidimensional structure; a holistic and dynamic development that encompasses the ability to cope with stress and serious situations |

| Bull (2014) 71 | Process | A dynamic process that fluctuates across time and situations and enables individuals to adjust or cope successfully despite stress or adversity |

| Jones et al. (2019) 54 | Process | A dynamic and interactive phenomenon, which is triggered by an antecedent event and developed through the interplay of risks and resources |

| Kidd et al. (2011) 72 | Trait | Human beings are engaged in goal‐directed movement that has unified patterns and utilizes creative power (resilience) to overcome obstacles; resilience is a positive psychological resource |

| Qualitative studies (n = 7) | ||

| Bekhet and Avery (2018) 19 | Trait | When homoeostasis is restored after adversity, which includes new insight and growth from a disruptive experience |

| Roberts and Struckmeyer (2018) 73 | Hybrid (trait–process) | The ability to maintain normal or enhanced functioning during times of adversity and consists of two components: the first is thriving and succeeding; the second is showing the competence in difficult situations or a situation where others often do not succeed |

| Han et al. (2019) 25 | Trait | To be able to restore balance and harmony when they encounter negative circumstances, which may be achieved by enhancing inherent adaptation |

| Liu et al. (2020) 74 | Process | The process of effectively negotiating, adapting to or managing significant sources of stress or trauma; assets of and resources available to the individual, their life and environment facilitate this capacity for adaptation and ‘bouncing back’ in the face of adversity; across the life course, the experience of resilience will vary |

| Donnellan et al. (2015, 2017, 2019) 38 , 52 , 53 | Process | The process of effectively negotiating, adapting to or managing significant sources of stress or trauma; assets of and resources available to the individual, their life and environment facilitate this capacity for adaptation or bouncing back in the face of adversity |

Abbreviation: NR, not reported.

Beyond these commonalities, researchers differed in terms of whether they defined resilience as a multidimensional process or a personality trait. On one side of this discordance, some studies (n = 8, 16%) used language that illustrated resilience as a personal quality, skill or attribute enabling caregivers to adapt in the experience of hardship. 49 , 55 , 64 , 67 , 70 , 76 , 78 , 92 Comparably, resilience was described in articles (n = 7, 14%) as an individual's ability or capacity to adjust successfully and maintain normal functioning despite adverse trauma, 63 , 65 , 73 , 79 , 80 , 88 , 89 alluding to the belief that resilience is a fixed competence. In fact, the main aim of one study was to test the hypothesis that caregiver resilience is a personality trait, after which it was concluded that resilience is, indeed, an individual characteristic. 89 Thus, a total of 22 (44%) studies explicitly advanced trait definitions of resilience. 19 , 25 , 51 , 56 , 57 , 59 , 60 , 61 , 63 , 65 , 66 , 70 , 72 , 76 , 79 , 80 , 81 , 82 , 83 , 88 , 89 , 90 In contrast, a substantial proportion (n = 18, 36%) of researchers opted for construing resilience as a dynamic process. 38 , 46 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 52 , 53 , 54 , 55 , 62 , 68 , 69 , 71 , 74 , 77 , 84 , 86 , 91 Some (n = 7, 14%) authors used a more mixed model of resilience, presenting the concept of resilience as a hybrid of both a personality characteristic and an evolving process. 58 , 64 , 67 , 73 , 78 , 87 , 92

3.2.2. Origins of resilience definitions

Authors conceptualized resilience in a diversity of forms, citing numerous sources in support of their interpretation. Many authors interpreted resilience from a combination of sources, electing to not advance a singular definition. Some studies (n = 12, 24%) specified the use of a specific resilience theory or framework. 19 , 25 , 38 , 52 , 53 , 67 , 76 , 79 , 80 , 81 , 83 , 86 Of the frameworks explicitly included, the Ecological Resilience Framework 31 applied to caregivers was most common and incorporated into four studies (8%). 25 , 38 , 52 , 53 Two sets of original resilience theorists were frequently accredited as the primary source of authors' understanding and characterization of resilience. These theorists include (1) Wagnild and Young, 37 who offer a trait‐based resilience definition, and (2) Windle et al., 29 , 31 who conceptualize resilience as an unfixed process. The former was utilized in some studies (n = 4, 8%), 70 , 76 , 88 , 90 and the latter was found in multiple studies (n = 8, 16%). 38 , 48 , 52 , 53 , 54 , 69 , 74 , 77

3.2.3. Measurement and levels of resilience

In quantitative and mixed‐methods studies, 12 different instruments were used to measure resilience. A summary of the 12 scales is presented in Table 4. Three studies (6%) used caregiver‐specific measurements. 50 , 85 , 86 The most commonly used scale was the Resilience Scale (RS) by Wagnild and Young. 37 Twelve studies (24%) 46 , 58 , 70 , 71 , 72 , 76 , 78 , 87 , 88 , 89 , 90 , 91 used the full version of the RS, whereas four studies (8%) used the short form. 66 , 80 , 81 , 82 A second common scale was the CD‐RISC. 32 , 93 , 94 Seven studies (14%) used the full version of the CD‐RISC, 51 , 64 , 65 , 75 , 79 , 84 , 92 while one (2%) study used a shortened form. 60 Another commonly used scale was the six‐item BRS, 36 reported in seven studies (14%). 47 , 56 , 57 , 63 , 67 , 69 , 83 Original validation of the included scales reported acceptable to strong internal consistency (α = .67–.95). Several of the retained studies (18%) assessed resilience scale reliability within their caregiver samples, 46 , 59 , 62 , 63 , 67 , 69 , 84 , 85 , 87 demonstrating acceptable to strong internal consistency (α = .73–.96). Three studies (6%) developed and validated instruments to measure caregiver resilience, 50 , 66 , 86 and reported strong reliability (α = .87–.96).

Table 4.

Description of resilience measures included in the review

| Scale | Author(s) | Country of origin and language | Target population | Number of dimensions (items) | Cronbach's α | Retained studies that assessed scale reliability (CNC population) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

The Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale |

Connor and Davidson (2003) 32 | USA/English | Adults | 5 (25) |

.89–.93a .87 |

Ghaffari et al. (2019) 84 (AD) |

|

The Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale (shortened version) |

Cambell‐Sills and Stein (2007) 94 | USA/English | Young adults | 1 (10) | .85a | |

| The Resilience Scale | Wagnild and Young (1993) 37 | Australia/English | Adults | 2 (25) |

.91a .80 .94 |

Kimura et al. (2019) 87 (YOAD) Scott (2013) 46 (AD) |

| The Resilience Scale (shortened version of RS) | Neill and Dias (2001) 95 |

Australia/English |

Adults | 14–15 |

.91a .96 |

Wilks (2008) 66 (AD) |

| The Brief Resilience Scale | Smith et al. (2008) 36 |

USA/English |

Adults | 1 (6) |

.80–.91a .73 .82 .89 |

Ertl et al. (2019) 63 (PD) Ledbetter et al. (2020) 67 (SCI) Tyler et al. (2020) 69 (PD) |

| The Resilience Scale for Adults | Friborg et al. (2003) 96 | Norway/Norwegian | Adults | 5 (36) | .67–.90a | |

| The Resilience Scale for Adults | Friborg et al. (2005) 97 | Norway/Norwegian | Adults | 6 (33) |

.76–.87a .96 .92 .82 |

Elnasseh et al. (2016) 62 (dementia) Pandya (2019) 85 (AD) Senturk et al. (2018) 59 (dementia) |

| TBI‐QOL Resilience Short Form | Tulsky et al. (2016) 98 | USA/English | TBI | 1 (27) | .95a | |

| The Dispositional Resilience Scale | Bartone et al. (1989) 99 | USA/English | Adults | 3 (45) | .78a | |

| The Brief Resilient Coping Scale | Sinclair and Wallston (2004) 100 | USA/English | Adults with rheumatoid arthritis | 1 (4) | .69a | |

| Questionnaire of Resilience in Caregivers of Acquired Brain Injury | Hayas et al. (2015) 50 | Spain/Spanish | Family caregivers of persons with ABI | 1 (31) | .88a | Hayas et al. (2015) 50 (ABI)b |

| The Caregiver Resilience Scale | Maneewat et al. (2016) 86 | Thailand/Thai | Family caregivers of persons with dementia | 6 (30) |

.87a .87 |

Maneewat et al. (2016) 86 , b (dementia) Pandya (2019) 85 (AD) |

Abbreviations: ABI, acquired brain injury; AD, Alzheimer's disease; PD, Parkinson's disease; YOAD, young‐onset Alzheimer's disease.

Indicates the α value reported in the original scale development and validation.

Indicates original scale validation and article retained within current review.

Most quantitative and intervention studies assessed and reported the level of resilience among sampled caregivers. However, the majority of studies (n = 22, 44%) did not interpret these resilience measures in reference to scale‐based criteria or in comparison to other populations; instead, most attended to other resilience‐related results, incorporating resilience as a modulator, outcome or into higher‐level models. Within those that did measure and interpret resilience as a continuous variable, sampled caregivers demonstrated moderate‐to‐high‐resilience levels in seven articles (14%), 58 , 71 , 76 , 82 , 83 , 87 , 89 while two articles (4%) also inferred low‐resilience levels in a minority of participants. 58 , 71 Numerous studies (n = 10, 20%) sought to categorically classify participants into different resilience groups, either as resilient or nonresilient, 38 , 52 , 53 or in some version of low‐, medium‐ or high‐resilience groups. 49 , 54 , 55 , 56 , 57 , 77 , 91

3.3. Correlates and predictors of psychological resilience

3.3.1. Sociodemographics and contextual resources

As summarized in Table 5, 12 (24%) studies examined sociodemographic or contextual factors including gender, injury or disease severity and clinical symptoms associated with resilience. 48 , 49 , 57 , 58 , 60 , 67 , 77 , 83 , 87 , 88 , 89 , 90 Our synthesis revealed heterogeneity in studies reporting the relationship between sociodemographic and clinical characteristics and resilience. Six articles (12%) demonstrated that demographic, CNC severity, clinical and health status variables were not significantly related to caregivers' resilience levels. 58 , 77 , 87 , 89 , 90 , 91 In contrast, findings from 11 studies (22%) indicated that demographic and clinical variables were significantly related to resilience, including income, 62 , 85 employment status, 83 gender, 49 , 72 , 83 , 85 ethnicity, 81 , 85 age 72 and severity of dementia. 88

Table 5.

Quantitative, mixed‐methods and qualitative articles' descriptions and summaries of resilience findings

| Author (year) | Purpose | Recruitment setting | Resilience scale or measure | Mean resilience score (SD) | Key results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quantitative, cross‐sectional or longitudinal studies (n = 35) | |||||

| Castellano‐Tejedor and Lusilla‐Palacios (2017) 58 | To describe a sample of caregivers of persons SCI, their burden of care, resilience and life satisfaction and to assess the relationships between these variables and other sociodemographic factors | SCI acute unit from a tertiary university hospital following discharge | The Resilience Scale |

141.93 (23.4) |

Half of the sample showed moderate–high resilience; few had low‐resilience scores. Resilience was not related to caregivers' demographics or SCI severity. Burden was negatively correlated with resilience. Resilience was positively correlated with relationship satisfaction |

| Senturk et al. (2018) 59 | To examine the relationship between caregiver burden and psychological resilience in caregivers of PWD | Outpatient neurology department of a university hospital | The Resilience Scale for Adults |

111.25 (23.9) |

Negative correlation between the caregiver burden index and resilience scores |

| Garity (1997) 76 | To investigate the relationship between stress level, learning style, resilience factors and ways of coping in AD family caregivers | Support groups of an AD association | The Resilience Scale | 144.4c | Participants were moderate–high on resilience scores and used problem‐ and emotion‐focused coping. Resilience positively correlated with emotion‐ and problem‐focused coping |

| Scholten et al. (2020) 60 | To identify intra‐ and interpersonal sociodemographic, injury‐related and psychological variables measured at admission of inpatient rehabilitation that predict psychological distress among dyads of individuals with SCI or ABI and their significant others 6 months after discharge |

Part of a larger study conducted in regional rehabilitation centres |

Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale Short‐form |

28.2 (6.1) |

Higher baseline psychological distress, lower scores on adaptive psychological characteristics (combination of self‐efficacy, proactive coping, purpose in life and resilience), and higher scores on maladaptive psychological characteristics (combination of passive coping, neuroticism, appraisals of threat and loss) were related to higher psychological distress, as well as crosswise between individuals with SCI or ABI and their significant others |

| Brickell et al. (2020) 77 | To examine factors related to resilience in military caregivers across health‐related caregiver QOL, caregiver sociodemographic variables and SMV injury and health status | TBI clinics at a National Military Medical Centre; Marine Corps base camp; community outreach activities | TBI‐QOL Resilience Short form |

55.6 (9) |

There were no differences across caregiver resilience groups (‘low‐moderate’, ‘moderate’, ‘moderate‐high’) for most demographics, SMV injury and health status variables. Low resilience was related to strain on employment due to caregiving duties, financial burden, caring for children, less personal time, caring for both verbal and physical irritability, anger and aggression and lower SMV functionality. Lower resilience was associated with poorer health‐related QOL scores across all groups |

| Simpson and Jones (2013) 91 | To investigate the relationship between resilience and positive affect, negative affect and burden in caregiving; the relationship between resilience and helpfulness of caregiving management strategies; and the similarities and differences in resilience among family TBI versus ABI caregivers | Review of medical records and staff caseloads | The Resilience Scale |

140.2 (18.7) |

Positive correlation between resilience and positive affect. Resilience demonstrated a negative correlation with negative affect and burden scores. No link was found between resilience and the relatives' severity of functional impairment. Participants with high‐resilience scores rated certain caregiving strategies as more helpful than those with low‐resilience scores |

| Cousins et al. (2013) 61 | To explore the influence of family caregivers on the uptake of NIV in persons with MND | Specialist neurology and respiratory clinics | The Dispositional Resilience Scale |

NIV |

Caregivers supporting NIV treatment were more resilient. Caregiver resilience (commitment) was the strongest predictor of uptake of NIV treatment |

| 88.63 (13.2) | |||||

| Decliners | |||||

| 73.50 (15) | |||||

| Elnasseh et al. (2016) 62 | To examine whether healthier family dynamics are associated with a higher sense of coherence, resilience and optimism in dementia caregivers in Latin America | Regional Neuroscience Institute | The Resilience Scale for Adults |

204.29 (21.8) |

Family dynamics explained 32% of the variance in resilience. Income was associated with resilience. Greater family empathy and decreased family problems were associated with higher resilience |

| Ertl et al. (2019) 63 | To examine whether resilience moderates the relation between perceived stress and health‐related QOL among PD caregivers in Mexico | Outpatient neuropsychological services at the National Neuroscience Institute | The Brief Resilience Scale |

21.28 (4.4) |

Resilience moderated the inverse relationship between perceived stress and mental health‐related QOL. Resilience did not moderate the relation between stress and physical health‐related QOL |

| Fitzpatrick and Vacha‐Haase (2010) 78 | To examine the relationship between resilience and marital satisfaction in caregivers of spouses with dementia | Gerontology Research Unit at regional hospital and local caregiver support groups | The Shortened Resilience Scale |

5.5 (0.8) |

Resilience was not correlated with marital satisfaction. Marital satisfaction was influenced most by caregiver burden (negative influence) and caregiver age (positive influence) |

| Kimura et al. (2019) 87 | To investigate the relationship between clinical symptoms of people with young‐onset Alzheimer disease (YOAD) and carer resilience | AD outpatient clinic at the University Institute of Psychiatry | The Resilience Scale |

141.4 (13.5) |

Carers showed moderate to high levels of resilience. No relationship was found between carer resilience and both carer and care‐recipient sociodemographic characteristics. No relationship was found between career resilience and clinical symptoms of persons with YOAD. Resilience was inversely associated with carers' depressive symptoms |

| Ruisoto et al. (2020) 64 | To examine factors that predict burden in a sample of family caregivers of PWD | Referral lists of the associations of relatives of people with AD and other dementias, neurology outpatient clinics and the national reference centre of AD | The Connor‐Davidson Resilience Scale |

73.9 (13.7) |

Caregiver burden correlated negatively with resilience. Resilience explained 18.7% of variance in social support and social support accounted for 46.11% of variance in burden. Social support partially mediated the relationship between resilience and burden in caregivers |

| Scott (2013) 46 | To examine the moderating effect of resilience between caregiver stressors and caregiver burden | Community agencies that provide education and support to AD caregivers in the region | The Resilience Scale | NR | Resilience was not identified as a moderator of the relationship between stressors and caregiver burden. An inverse relationship existed between resilience and caregiver burden |

| Pessotti et al. (2018) 88 | To evaluate family caregivers' perception of QOL, burden, resilience and religiosity and relate them with cognitive aspects and occurrence of neuropsychiatric symptoms of elderly persons with dementia | Clinical Neurology Outpatient Clinic at the regional hospital | The Resilience Scale |

135.6 (22.5) |

Resilience was associated with better perceived QOL, severity of dementia, higher intrinsic religiosity and lower occurrence of depressive symptoms |

| Wilks and Vonk (2018) 79 | To explore whether the coping method of private prayer served as a protective factor or mediator between caregiver burden and perceived resiliency among AD caregivers | Regional AD association caregiver support groups | The Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale |

73.4 (13.4) |

Burden positively affected the extent of prayer usage and negatively influenced resilience. Caregiver burden and private prayer influenced variation in resilience scores. Results support prayer as a mediator between burden and resilience |

| Rosa et al. (2020) 90 | To investigate resilience in caregivers of people with mild and moderate AD and the related sociodemographic and clinical characteristics | Outpatient clinic of the university institute of psychiatry and AD | The Resilience Scale |

140.6 (17.2) |

In persons with mild and moderate AD, caregiver resilience was inversely related to emotional problems. There was no difference between resilience in caregivers of people with mild versus moderate AD. In the mild AD group, neuropsychiatric symptoms of the person with AD and caregiver's depressive symptoms were related to caregiver resilience. In the moderate AD group, caregiver QOL and coresiding with the care‐recipient were related to resilience |

| Chan et al. (2019) 83 | To explore caregiver strain and resilience of caregivers of patients with AD in Malaysia; to determine factors associated with caregiver strains in caregivers of patients with AD; and to determine the effect of resilience on the relationship between caregiver strains and caregiver or patient factors | AD Foundation Malaysia | The Brief Resilience Scale |

19.2 (3.3) |

The sample demonstrated moderate to high resilience. Resilience was associated with gender and employment status. A negative correlation was found between resilience and caregiver strain |

| Dias et al. (2016) 89 | To investigate the relationship between resilience and sociodemographic and clinical factors of people with dementia; to test the hypothesis that caregivers' resilience is a personality trait, independent from the clinical symptoms of the person with dementia | Physicians' referral from a dementia outpatient clinic | The Resilience Scale |

137.6 (15.5) |

Participants reported moderate to high levels of resilience. Resilience was not related to gender, clinical or emotional problems. Resilience was related to caregiver QOL, and inversely associated with depressive symptoms. There was no relationship between caregivers' resilience and sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of people with dementia. The authors concluded that resilience is an individual characteristic |

| Serra et al. (2018) 65 | To investigate a set of caregiver and patient factors, such as psychosocial protective variables, linked to abuse‐related behaviour of PWD | Referrals from the associations of relatives of PWD, neurology outpatient clinics and The National Reference Centre of AD | The Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale |

73.9 (13.7) |

Resilience and social support were negatively associated with abuse scores (i.e., protective effect). Social support and resilience were associated with a lower probability of abuse |

| Sutter et al. (2016) 47 | To examine the relationships between personal strengths (optimism, sense of coherence and resilience) and mental health of dementia caregivers from Latin America | Regional neuroscience institute and university, local neurology outpatient clinics, flyers, word‐of‐mouth, local community connections | The Brief Resilience Scale | 17.4 (5.6) | More manageability, general resilience and social competence were uniquely associated with lower depression. Resilience and other variables were not predictive of caregiver burden or life satisfaction |

| Jones et al. (2018) 48 | To describe the demographic and psychosocial characteristics of caregivers who attend dementia cafes and to identify which factors influence the likelihood of family caregivers attending dementia cafes | Dementia cafes and health and well‐being events facilitated by local AD or well‐being societies | The Brief Resilient Coping Scale | NR | Caregivers who attended cafes reported higher resilience and subjective well‐being; no difference in social support was detected |

| Jones, Killett et al. (2019a) 55 ; Jones, Woodward et al. (2019b) 49 | 2019a | Adverts in newsletters, carer information events held by local charities and an online carer's forum, dementia cafes | The Brief Resilient Coping Scale | NRa | 2019a |

| To investigate factors that affect resilient coping in carers; to assess whether symptoms of distress vary between carers with differing levels of resilient coping; and to identify whether resilient coping acts as a mediator in the carer distress–well‐being relationship | ‘High’ resilient carers reported less distress than ‘low’ resilient carers. Resilient coping partially mediated the relationships between well‐being and caregiver distress (i.e., depression, anxiety, stress and burden). Carers with high resilient coping skills reported less depression, anxiety, stress and burden than those with ‘low’ resilient coping | ||||

| 2019b | 2019b | ||||

| To compare sociodemographic characteristics and the availability of social support for carers with ‘low’ and ‘high’ resilient coping and to identify if social support predicted high resilient coping in informal carers of people with dementia | The availability of emotional/informational support was most likely to predict resilient coping and tangible support was the least likely to predict resilient coping. Only gender predicted high resilient coping. No single domain of social support had a greater influence on resilient coping | ||||

| Wilks et al. (2011, 2018) 80 , 81 ) | 2011 | Mailing lists from a nonprofit AD services organisation; African American communities (e.g., churches, community centres, adult day centres, a home health agency, caregiver homes) | The Shortened Resilience Scale | 2011 | 2011 |

| This study assessed the impact of AD patients' aggressive behaviour (i.e., AD aggression) on caregiver coping strategies (task‐, emotion‐, and avoidance‐focused) and caregiver resilience, and examined whether a coping strategy moderated the AD aggression–caregiver resilience relationship | 5.9c | Aggression negatively predicted caregiver resilience. All coping strategies correlated with resilience scores. Task‐focused coping was positively related to resilience. Emotion and avoidance‐focused coping strategies separately interacted with aggression and increased their negative relationship with resilience. Task‐focused coping showed no moderating effect | |||

| 2018 | 2018 | 2018 | |||

| To understand whether spiritual support with AD caregivers acts as a moderating factor among the caregiving burden–resilience relationship in a manner similar to caregiver social support, and to observe ethnicity, African American versus Caucasian caregivers, in said moderation | 5.8c | For each ethnic group of caregivers, burden was inversely proportional to resilience. In all groups, the association between spiritual support and resilience was positive and direct. Social support did not moderate risk within either group. African American caregivers reported higher resilience than their Caucasian counterparts | |||

| Wilks (2008a) 66 ; Wilks and Croom (2008b) 82 | 2008a | Two large AD care conferences: one held in a large urban area and another held in a rural locale | The Shortened Resilience Scale |

5.5 (1.3) |

2008a |

| To evaluate psychometric properties of the shortened Resilience Scale among a sample of AD caregivers | Results confirmed the RS15 to be a psychometrically sound measure that can be used to appraise the efficacy of caregiving adaptability among the sample | ||||

| 2008b | 2008b | ||||

| To examine whether social support functions as a protective, resilience factor among AD caregivers; to examine the relationship between risk (i.e., perceived stress) to mental and physical health, an outcome of resilience and potential protective factors for resilience among caregivers | The sample reported moderate to high resilience. Perceived stress negatively influenced resilience and accounted for 43% of variance in resilience scores. Social support positively influenced resilience, and caregivers with high family support had the highest probability of elevated resilience. Social support is a protective mediator of resilience | ||||

| Anderson et al. (2019) 92 | To integrate related explanatory (personality, coping) and mediating (hope, resilience, self‐efficacy) and caregiver outcome (burden, psychological distress, quality of life) variables into a larger model and to test the role of resilience, hope and self‐efficacy among family caregivers of persons with TBI | Six regional inpatient and community rehabilitation centres | The Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale |

76.23 (12.3) |

The model accounted for 63% of the variance in resilience. Resilience had a direct effect on positive affect in caregivers. There was a strong positive association between general self‐efficacy and resilience. Problem‐focused coping had a direct positive effect on resilience. Resilience was indirectly associated with caregiver burden when mediated through social support. Resilience demonstrated a direct effect on hope that is associated with positive mental health. Resilience was associated with reduced morbidity |

| Hayas et al. (2015) 50 | To develop the Questionnaire of Resilience in Caregivers of Acquired Brain Injury (QRC‐ABI) and explore its psychometric properties | The Federation of ABI Associations and public day care centres specializing in ABI | QRC‐ABI |

43.24 (11.3) |

The QRC‐ABI showed good reliability and validity. Convergent validity was supported through positive correlations of the QRC‐ABI with QOL, positive aspects of caregiving and posttraumatic growth and a negative correlation with perceived burden |

| Vatter et al. (2018, 2020) 56 , 57 | 2018 | Nation‐wide post or as part of a larger study (ref) | The Brief Resilience Scale |

24.97 (11.9) |

2018 |

| To explore the factor structure of the Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI) in life partners of people with Parkinson's‐related dementia and to examine the relationships among the emerging factors and the demographic and clinical features | Five factors of the ZBI (i.e., social and psychological constraints, personal strain, interference with personal life, concerns about future and guilt) all negatively correlated with resilience. Lower resilience and higher negative strain and feelings of resentment were contributors to burden | ||||

| 2020 | 2020 | ||||

| To explore and compare levels of mental health, care burden and relationship satisfaction among caregiving spouses of people with mild cognitive impairment or dementia in PD (PDD) or dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) | Over 75% of respondents reported good resilience. ZBI scores correlated with resilience. Caregivers who were dissatisfied with their relationship reported lower resilience. Burden, stress, resilience, relationship satisfaction, quality of life, anxiety, depression and mental health levels did not differ between spouses of people with PDD and DLB. | ||||

| Ledbetter et al. (2020) 67 | To investigate how individual and contextual factors (i.e., caregiving tasks, resilience, timing of the SCI) moderate the extent to which receiving social support predicts psychosocial distress among SCI caregiving romantic partners | Online groups targeted at SCI caregivers | The Brief Resilience Scale |

4.05 (0.8) |

Resilience inversely predicted psychosocial distress in both the preinjury and postinjury groups. Findings revealed the benefits of resilience. Receiving high‐quality support and timing of the injury moderated resilience effects. Injuries sustained after relationship initiation threatened well‐being and closeness and altered the extent to which support and resilience were associated with health and relationship benefits |

| O'Rourke et al. (2010) 68 | To examine the three facets of psychological resilience (i.e., perceived control, commitment to living, challenge versus stability) as predictors of depressive symptoms over time among spousal caregivers of PwAD | Clinic for AD and related disorders at a regional university hospital | The Dispositional Resilience Scale | NR | Resilience was associated with depressive symptoms among caregivers. Challenge and perceived control predicted depressive symptoms 1 year later. An increase in challenges over time predicted lower levels of depressive symptoms at Time 2. Commitment was not associated with depressive symptoms at any time point |

| Rivera‐Navarro et al. (2018) 51 | To validate the Caregiver Abuse Screen (CASE) as an instrument for detecting the maltreatment of people with dementia in Spain | Local associations of relatives of people with AD and other dementia and neurology outpatient clinics | The Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale |

73.6 (13.4) |

High CASE scores were associated with greater burden, lower social support and lower resilience of caregivers. Resilience scores were negatively correlated with interpersonal abuse and neglect/dependency. The consistent negative association of CASE scores with resilience is indicative of this advantageous characteristic |

| Tyler et al. (2020) 69 | To validate a theoretical structural equation model whereby social support is associated with higher levels of resilience in PD caregivers and increased resilience is related to decreased mental health symptoms | PD clinics associated with academic university institutions in Mexico and the PD and Movement Disorders Center at a regional medical centre in the USA | The Brief Resilience Scale | NR | The model explained 11% of the variance in resilience. Higher levels of social support were associated with higher resilience, which in turn was associated with lower mental health symptoms. Resilience partially mediated the effect of social support on mental health symptoms |

| Quantitative, intervention studies (n = 4) | |||||

| Ghaffari et al. (2019) 84 | To determine the effectiveness of resilience education in the mental health of family caregivers of elderly patients with AD | Referrals from regional hospital and neurologist offices | The Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale | NR | Resilience education promoted the mental health of family AD caregivers by decreasing somatic symptoms and social dysfunction |

| Lavretsky et al. (2010) 75 | To examine the potential of an antidepressant drug (escitalopram) to improve depression, resilience to stress and quality of life in family dementia caregivers in a randomized placebo‐controlled double‐blinded trial | NR | The Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale |

60.2 (16.7) |

Measures of depression, anxiety, resilience, burden and distress and quality of life improved on escitalopram compared with placebo groups |

| MacCourt et al. (2017) 70 | To assess the structure and effectiveness of a grief management coaching intervention with caregivers of individuals with dementia | Local social media and referrals from regional AD society | The Resilience Scale |

Spouse T1: 67.9c T2: 68.9c |

For the intervention group, grief, coping, empowerment and resilience scores improved postintervention. The intervention group showed greater resilience at Time 2. Time 1 resilience scores predicted greater resilience at Time 2 |

|

Adult child T1: 66.6c T2: 71.1c |

|||||

| Pandya (2019) 85 | To report the impact of a long‐term meditation programme for enhancing self‐efficacy and resilience of home‐based caregivers of older adults with AD | Network of agencies linked to older adults, geriatric clinics and units in private hospitals | The Resilience Scale for Adults; The Caregiver Resilience Scale (CRS) |

RSA Control Pre: 99.2 (8.3) Post: 100 (8.3) Intervention Pre: 100.31 (9) Post:187.93 (14.2) |

Posttest RSA and CRS scores of the intervention group were higher than the control group and their own pretest scores. Caregiver women, spouses, Hindus, middle class, with college and higher education, homemakers, who attended at least 75% of the meditation lessons and regularly practiced meditation at home reported lower posttest perceived caregiving burden, higher self‐efficacy and resilience. Meditation was effective for increasing resilience |

|

CRS Control Pre: 30.28 (4.4) Post: 31.03 (5.3) Intervention Pre: 31.21 (4.9) Post: 58.71 (6.8) |

|||||

| Mixed‐methods studies (n = 4) | |||||

| Maneewat et al. (2016) 86 | To develop the CRS for Thai caregivers of older persons with dementia and to examine its validity and reliability | Memory Clinic, Neurological Clinic or Geriatric Clinic in the Outpatient Department at a regional hospital | The CRS; semi‐structured interviews | NR | The final version of the CRS was composed of 30 items within six domains: physical competence; relationship competence; emotional competence; cognitive competence; moral competence; and spiritual competence. The 30‐item CRS was considered a valid and reliable instrument |

| Bull (2014) 71 | To describe family caregivers' level of resilience and psychological distress and to describe the strategies that family caregivers use to persevere in their caregiving role despite the challenges encountered in caring for a family member with dementia | Five adult day centres located in a city setting | The Resilience Scale; narrative interviews |

154.3 (15.8) |

Participants had high resilience and low psychological distress. The use of self‐sustaining strategies explained the high scores on resilience and low levels of psychological distress. Caregivers used four strategies to sustain the self: drawing on past life experiences that dealt with difficult situations, nourishing the self, relying on spirituality and seeking dementia‐related information |

| Jones et al. (2019) 54 | To explore discrepancies and congruency between definitions of resilience in the academic literature and carers' own conceptualizations; to assess differences and similarities in conceptualizations of resilience between carers with high‐, medium‐ and low‐resilience scores; and to compare carers' perceived level of resilience with the level of resilience when measured on a standardized tool | Theoretical sampling recruited from participants in previous study 48 | Brief Resilient Coping Scale; semi‐structured interviews | NR | Under half (46%) of the carers had low resilience. Carers' definitions of resilience were concordant with clinical and academic definitions; however, they extended the concept and placed greater value on the role of self‐compassion. Carers recognized that the appearance of resilience may have negative consequences in terms of securing support from others. Resilience scores did not always match carers' own perceptions of their level of resilience |

| Kidd et al. (2011) 72 | To test the effectiveness of a poetry writing intervention for family caregivers of elders with dementia and to examine outcome variables of self‐transcendence, resilience, depressive symptoms and subjective caregiver burden | Support groups, churches and agencies | The Resilience Scale; interviews | NR | Women were lower in self‐transcendence and resilience, and higher in depressive symptoms and burden. Older caregivers scored higher than younger caregivers on the study variables of self‐transcendence and resilience. Poetry writing was an effective intervention that may promote resilient outcomes |

| Qualitative studies (n = 7) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author (year) | Purpose | Recruitment setting | Means of resilience assessment | Key results | |

| Bekhet and Avery (2018) 19 | To identify components of resilience theory (i.e., risk factors, protective factors, overlapping factors) from the perspective of caregivers of PWD | Regional AD Association early stage programmes | Open‐ended questions on written questionnaires | The experience of dementia caregiving involved a combination of risk factors and protective factors, suggesting that caregivers may feel conflicted. Risk factors included experiences of stress and difficulties, demanding tasks, frustration, lack of social support, exhaustion and negative feelings. Protective factors included feeling rewarded and serving a purpose. If protective factors were more predominant, then caregivers became more resilient and experienced associated positive health outcomes | |

| Roberts and Struckmeyer (2018) 73 |

To examine family caregiver perspectives on how respite programming impacts their resilience and ability to better handle the demands of their responsibilities |

Recruited as part of a larger studyb through respite providers | Semi‐structured interviews | Several themes emerged describing the path to caregiver resilience that included family dynamics, isolation, financial struggles, seeking respite and acceptance. The road to acceptance became a critical factor in the development of resilience | |

| Han et al. (2019) 25 | To identify challenges, possible solutions as resources for resilience and expected consequences from the perspective of family caregivers of hospice patients with dementia | Two large hospice agencies recruited as part of a larger clinical trial | Deductive content analysis of secondary clinical trial data | Resilience resources were identified at the individual, community and societal levels. Resources included knowledge, self‐control and appraisal, self‐care, using visual materials, having options to choose a good care facility with exemplary providers, family or friends' support, involvement in volunteer activities, legislative support, public awareness and health insurance. Identified challenges were difficulties in communication, providing care and decision‐making, lack of knowledge, emotional challenges, concern about care facility selection, death with dignity and lack of public awareness | |

| Liu et al. (2020) 74 | To investigate the resilience of a growing but largely underserved and understudied population—Chinese American dementia caregivers, whose experience is embedded in their development throughout the life span, process of migration and sociocultural contexts | Local agency providing services for dementia caregivers with a representation of Chinese clients | Semi‐structured interviews | Main themes fit within two categories, challenge and resilience, in each of the four principles—time and place, timing in lives, linked lives and agency—of the developmental life course perspective. Physical and emotional exhaustion was the most frequently mentioned challenge theme, followed by limited knowledge of dementia, navigating the healthcare system and limited time for self‐development. Three aspects of resilience—sense of mastery, access to formal and informal support and commitment to care—were salient among caregivers | |

| Donnellan et al. (2015, 2017, 2019) 38 , 52 , 53 | 2015 | Two local dementia support groups and a care home | Semi‐structured interviews | 2015 | |

| To assess whether spousal dementia carers can achieve resilience and to reveal which factors and resources facilitate or hinder resilience within the ecological framework | Carers achieve resilience via a complex multidimensional process. A resilient carer was someone who stayed positive, who maintained their relationship with their loved one's former self, who were knowledgeable, well supported and who were engaged with respite services. Facilitating community factors included friendships with common experience and social participation. Individual hindering resilience factors were negative outlook and perceived social isolation | ||||

| 2017 | 2017 | ||||

| To explore social support as a key component of resilience and to identify the availability and function of support provided to older spousal dementia carers | Social support is not always sufficient to facilitate resilience, as negative perceptions of support may moderate the effect of support on resilience. Family and friends served a wide range of functions, but were equally available to resilient and nonresilient participants | ||||

| 2019 | 2019 | ||||