Abstract

The global demand for nurses was both proven and exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. With global migration on the rise, hospitals and health systems are looking to supplement their workforces with migrant nurses. Foreign-educated nurses bring expertise and diversity, but ethical recruitment must consider the balance between “brain drain” and an individual’s right to migrate. This paper highlights the contributions of foreign-educated nurses in the United States; explores the landscape, policy perspective, and market element of nurse migration, recruitment, and retention; and identifies key considerations that chief nursing officers should make as they look to build diverse and sustainable workforces.

Key Points.

-

•

Globally, migration is on the rise, and countries and CNOs are looking to supplement their workforce with migrant nurses.

-

•

Foreign-educated nurses bring economic and cultural benefits to workforces that may encourage CNOs to diversify their workforce beyond domestically educated nurses.

-

•

Ethical considerations must reflect the delicate balance between brain drain, brain gain, and the individual migrant’s right to live and work in their country of choice.

When the COVID-19 pandemic was declared in the early spring of 2020, the United States was already in the midst of a worsening nursing shortage. With over 1 million additional nurses needed by 2030 to support America’s health system and aging population, and a faculty shortage that limits the opportunity for entry-level aspiring nurses to join the profession, burnout and retirement have been outpacing increases in our domestic supply.1 In the midst of this shortage, foreign-educated nurses have been a critical resource for the US health system—providing essential, life-saving care and representing double-digit percentages of the nursing workforce in some of the largest states in the union.2

Internationally, most countries report some type of nurse shortfall.3 Nevertheless, migration is expected to increase in the fallout of the COVID-19 pandemic and broader demographic and economic trends, putting more foreign-educated nurses on a pathway to the United States. As hospitals turn to international recruitment to fill open positions, chief nursing officers (CNOs) and health administrators must be proactive and thoughtful in developing comprehensive and robust workforce strategies that reflect the increasing foreign-educated nursing workforce and the changing recruitment landscape.

Background

Beyond the COVID-19 pandemic, global migration has been robust and increasing since the turn of the millennium. In 2020, more than 280 million people resided outside of their country of origin, a steady increase from 221 million in 2010 and 173 million in 2000.4 International migration is expected to increase due to issues ranging from climate change, conflict, and inequality, as well as opportunities in labor, education, and technology.

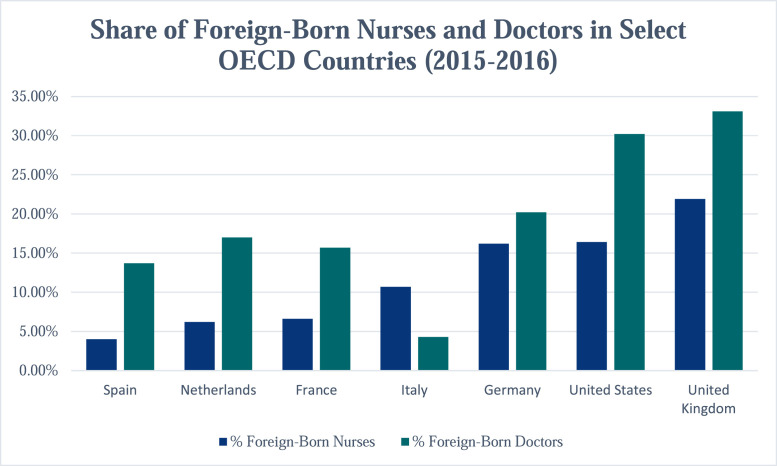

As the world grappled with the pandemic, many countries closed their borders and focused efforts inwards, impacting the mobility of migrants worldwide. Following the World Health Organization (WHO) declaring COVID-19 a pandemic in March 2020, nearly 110,000 mobility restrictions were enacted globally. At the same time, nearly 1000 exceptions have been issued for certain groups, particularly nurses and other health personnel.5 In several Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries that are among those with the highest number of confirmed COVID-19 cases in the world, foreign-educated doctors and nurses make up significant portions of their health systems (Figure 1 ).6, 3

Figure 1.

2015-2016 Data Shows that Foreign-Born Nurses and Doctors Made Up a Significant Portion of the Health Workforce in Multiple OECD Countries

Although travel and immigration restrictions froze many in place during the early stages of the pandemic, global migration is not stopping and will likely explode as the pandemic wanes. In many cases, the migration of health workers is pivotal to health systems across the developed world. Stakeholders must now grapple with the individual’s right to migrate versus the ethical concerns surrounding international recruitment, as well as the safety and sustainability of local health systems. In this context, there are several ongoing tradeoffs and competing considerations in the realm of migration and nursing workforce, both at local and global levels, that are worth exploring as we reflect on the pandemic and envision a post-pandemic world.

Considerations for Stakeholders in the Developed World

For many hospitals and health systems in developed countries, stakeholders (e.g., CNOs, nurse administrators, and staffing firms) have had to grapple with the risks and ethics of building sustainable health workforces that effectively leverage—but do not excessively rely on—a foreign-educated workforce. To prepare for a post-pandemic world, individual facilities and health systems alike need to prepare for fluctuations. COVID-19 turbocharged this reality as seen in several examples: the presence of a travel nursing workforce spiked compared to staff nurses; health systems dealt with major shifts in supply and demand (e.g., increased demand for ICU nurses, whereas nurses involved in elective surgeries faced layoffs). Nurse administrators and CNOs have always been thinking strategically about developing adaptable workforces that can meet the current and future demands of fluctuations. The pandemic has shown the dire need to develop and sustain a diverse nursing and health workforce even as the realization of that need seems more distant and unlikely than ever.

Global Policy Considerations

At the global level, policymakers and advocates must think about brain drain versus the individual’s right to make the best considerations for their families and careers. This debate has played out in several key international initiatives at both the bilateral and multilateral levels.

The UN Global Compact for Migration, signed in December 2018, recognizes the importance of migrant empowerment and its impact on inclusion and stability, while also recognizing the immense contributions of migrants to health systems, economies, and in attaining the goals of the UN’s 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Nurses play a pivotal role in migration and the compact because they are both facilitators of safe migration practices and also migrants themselves. Nurses’ knowledge, expertise, and experiences should be leveraged to attain the ambitious objectives of the Compact and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).7

The World Health Organization hosts similar debates, namely by way of the WHO Global Code of Practice on International Recruitment of Health Personnel and the outcomes of the 74th World Health Assembly (WHA) in May 2021. The WHO Code, which seeks to strengthen the understanding of ethical management of international health personnel recruitment through shared data, information, and international and multistakeholder cooperation, has been a guiding formula for ensuring adherence to ethical standards as we witness a global increase in the number of nursing and health care migrants. In May 2021, in light of over 115,000 health care worker deaths due to the pandemic, the WHA debated and adopted several resolutions that solidified the global commitment to nursing and healthcare professions, namely WHA74.14 Protecting, Safeguarding, and Investing in the Health and Care Workforce and WHA74.15 Strengthening Nursing and Midwifery: Investments in Education, Jobs, Leadership, and Service Delivery.8

Considerations for Stakeholders in the Developing World

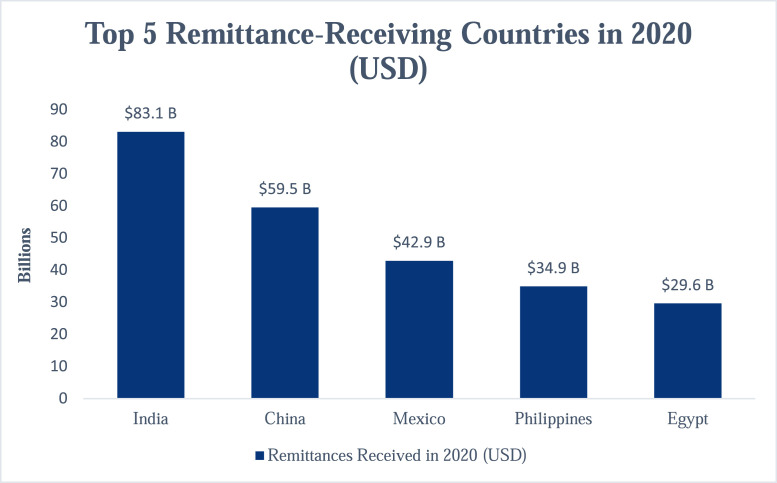

In the developing world, particularly in regions that are heavy suppliers of nurses and health workers, stakeholders (i.e., governments, regulators, nursing bodies) are grappling with their own need to maintain sustainable workforces versus the rights of their citizens to migrate and work in their country of choice. Similarly, there is a huge financial component, namely remittances, which make up large portions of national gross domestic products (GDPs) throughout the developing world.9 In the Philippines, for example, which is the world’s largest supplier of nurses, remittances comprise nearly 10% of the national GDP (Figure 2 ).10

Figure 2.

Countries with High Numbers of Migrant Workers Abroad Can Receive Billions in Remittances as Those Workers Send Money Home to Support Their Families and Communities

Foreign-Educated Nurses and Health Care Workers in the United States

The US—and global—health workforce is changing in the wake of the pandemic as stress, burnout, and job dissatisfaction are leading more health professionals to leave their professions or seek early retirement, adding to the mounting nursing shortage expected by 2030.11 With a domestic supply that will be unable to meet the coming demand for nurses, some health systems will use immigrant nurses to fill vacancies and fully staff their hospitals, clinics, and retirement homes.

In 2018, the US health workforce was composed of over 14 million workers, 18% of whom were foreign-born.2 Several US states such as New York, California, New Jersey, and Florida reported at least 30% of their health care professionals were immigrants in 2018.2 A recent survey of 1356 migrant nurses by CGFNS found that the top care settings during their employment the United States were critical care (19%), surgical/operating room (12%), and geriatric care (11%).

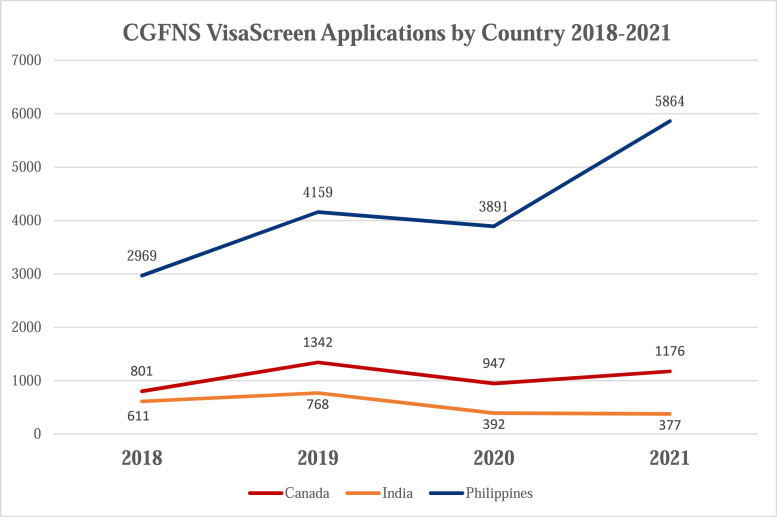

Since 2018, the biggest demographics in nurse migration to the United States have remained unchanged, with the largest percentage of migrants coming from the Philippines. The number of applicants for CGFNS’ VisaScreen program from the Philippines is triple that of the next in line, Canada, and more than quadruple of those migrating from India (Figure 3 ). From 2020 to 2021, the number of VisaScreen applications from Filipinos increased by 51%.

Figure 3.

For CGFNS VisaScreen, Applications from Filipinos Triple Those of the Next Highest Countries

A 2021 survey by CGFNS of 1356 migrant nurses found that these migrants are overwhelmingly registered nurses (94%) and over half report having more than 11 years of nursing experience. Sixty-five percent of those surveyed were under the age of 44 years and collectively report working more than 11,567 hours weekly with COVID-19 patients for the US health care system.

With the 2020 US Census confirming a shift in demographics, foreign-educated nurses not only provide critical support to our health system, but their language abilities and cultural knowledge expand access to health care and can elevate patient confidence levels and understanding.12 There has been a recent call for stronger support for bilingual education in domestic nursing students, acknowledging the need for a broader language skillset in the nursing workforce, citing the same benefits, and underlining the critical role migrant nurses play in our health system.13

Policy Perspective

Although the global border closures and travel restrictions implemented in 2020 led to a drastic drop-off in migration, the updated policies in the United States typically included exceptions for health workers. The Healthcare Workforce Resilience Act that was first introduced in 2020, sought 25,000 additional visas for nurses during the COVID emergency. In May of 2021, the American Hospital Association endorsed the bill, citing its ability to aid hospitals facing nursing shortages.

In spring of the 2021, the U.S. State Department announced a new visa prioritization system that relegated nurses and health professionals to the last tier. Since then, organizations including American Hospital Association and CGFNS had argued that there should be greater prioritization, and the State Department in an e-mail said they would allow nurses and health professionals seeking to aid the United States in response to the pandemic to request an emergency visa appointment. New legislation and policy changes have raised concerns from some stakeholders about the ethics of international recruitment as well as the impact these policies may have on work for domestic nurses, who are already overworked and often underpaid. While these concerns remain, there are ways to provide better support for all nurses, mitigating the harms of international recruitment.

Recently implemented federal and state COVID-19 vaccine mandates are further driving the need for a readily supply of nurses to fill roles vacated by those not willing to comply. States such as New York14 and Texas15 are already reporting unvaccinated staff departures, compounding the mounting nursing shortage nationwide. The mandate also affects nurses seeking to migrate, as all immigrants coming into the United States must be fully vaccinated.16

The anticipated increase in overseas recruitment of nurses and other health workers emphasizes the need to ensure ethical recruitment practices and provide better support for nurses as they navigate the migration process. Policy must consider both domestic and international nurses as the United States seeks to fill nursing shortages and continue to provide critical care during the pandemic.

Market Element

The economics of nurse migration, recruitment, and retention is complex and interconnected. The situation in the current pandemic era can best be described as a battle between acute demand versus throttled supply of foreign-born nurses and health personnel. Understanding the current state and predicting the future scenario around nurse migration and recruitment is useful for hospitals and health systems in the United States dealing with varying supply shortages and crises. There are several overlapping factors contributing to this heightened demand and limited supply including domestic nursing education deficiencies, and increased nurse retirement, burnout, and turnover, as well as restrictive international visa and migration-related barriers. Hospitals, health systems, and chief nursing officers in the United States should consider all these factors as they plan for a post-COVID world.

The pandemic has exposed the dire role nurses play in the country’s response to health crises, and from this, several deficiencies and warning signs have been highlighted. According to 2021 data, student enrollment in US schools of nursing has surged in 2020 despite difficulties faced during the pandemic. Specifically, enrollment in baccalaureate-level RN programs in the United States increased by nearly 6%, with more than 250,000 students now enrolled nationwide.17 Previously, a large contributor to the nursing shortage in the United States was declining student enrollment coupled with limited resources and nurse educators. Although the data suggest positive turns in domestic student enrollment, limitations still exist, and it is likely that even this impressive increase in student enrollment will not be sufficient to address the increasing nursing and health worker shortage.

Congruently, nursing turnover, burnout, and retirement are seemingly being intensified by the pandemic in many regions of the country. Since the start of the pandemic in March 2020, nursing turnover has increased by nearly 3%, totaling 19% in hospitals across the United States.18 A recent McKinsey & Company survey found that nearly 25% of nursing respondents indicated that they may leave their current position due to workforce strains and stresses during the pandemic.19 The average cost of turnover for a bedside nurse is roughly $40,000, with the total toll for an average hospital of $4 to $6.5 million per year.

Nurse retirement is an equally as rampant and has been accelerated by the pandemic. According to a 2020 National Council of State Boards of Nursing National Nursing Workforce Survey, the median age of RNs in the United States was 52 years old, which would assume a wave of mass retirement over the next 15 years.20 Although the pandemic has prompted many nurses to come out of retirement to aid struggling health systems or to administer vaccines, COVID-19’s impact on nurse retirement will be felt for years to come. The International Council of Nurses (ICN) suggests that the pandemic is causing mass trauma among the profession, as more than 2,200 nurses have died as a result of the pandemic, and many more have become infected, distressed, burned out, or even abused as a result.21

Although there are several domestic factors contributing to supply shortages and increased demand, several impeding visa and migration-related restrictions abroad should be noted. Most notably are the basic border shutdowns enacted as responses to the pandemic. At the height of the pandemic in 2020, 91% of the world’s population resided in countries with travel restrictions, whereas nearly 40% of the globe lived in countries with borders completely closed.22 The Republic of India, which makes up one of the largest portions of foreign-educated nurses in the United States after the Philippines, restricted travel between domestic regions and implemented a complete ban on all international flights through September 2021. Although not specifically targeted, all Indian nurses, even those who were granted visas to work abroad, were not physically able to travel and begin their contracts. Though it has since been removed, Filipino president Rodrigo Duterte issued an order barring all nurses and health workers from leaving and working abroad, an order that would have dire consequences to health systems around the world that rely on the supply of Filipino nurses as well as the Filipino economy, which relies heavily on remittances. Though this ban has been removed, an annual cap of 6,500 nurses and health worker emigrants per year remains in effect. This juxtaposes the roughly 17,000 Filipino nurses who signed overseas work contracts in 2019.23

From this complex landscape, several conclusions and lessons learned can be drawn and utilized by health systems in the United States. Although the pandemic has intensified pre-existing nursing shortages across the country due to nursing education deficiencies, burnout, retirement, and retention, reliance on and recruitment of foreign-educated nurses has been a proven solution for competent and comparable additions to suffering workforces in the United States. However, the COVID-19 situation is unique in that it fosters several conflicting and overlapping visa and migration-related restrictions that act as barriers to the mobility of said health personnel. In this light, foreign-educated nurses are not a helpful component to address immediate shocks and shortages, such as those heightened during the pandemic, but rather can help be a part of the solution for medium- to long-term needs of hospitals and health systems.

Conclusion

The demand of nurses, especially in the United States, was both proven and exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic and will likely increase for years to come without strategic and impactful intervention at local, national, and global levels.3 This is due to an array of factors such as institutional limitations of domestic nursing schools and changing domestic nursing demographics (e.g., retiring nurses and high turnover rates). As shortages persist, hospitals and health systems may increasingly look to international nurse recruitment, as they have historically done in the past during times of shortage and crisis. In this context, several concerns must be considered by chief nursing officers and nurse leaders in the United States as they look to build diverse and sustainable workforces.

-

•

The economic impacts of nurse turnover are huge, and CNOs may consider focusing efforts on retention, rather than acquisition, through empowering valuing their workforces.

-

•

At the same time, foreign-educated nurses bring several economic and cultural benefits to workforces that may encourage CNOs to diversify their workforce beyond domestically educated nurses.

-

•

Globally, migration and nurse migration are on the rise, and there is an ample supply of nurses prepared and equipped to migrate. Although international mechanisms provide guidance on how recruitment should work, US immigration law and process will impact the ability to deploy migrating nurses in the United States.

-

•

Still, ethical considerations must reflect the delicate balance between “brain drain,” “brain gain,” and the individual migrant’s right to live and work in their country of choice. Frameworks that recognize the unique characteristics of the US health care system and develop best practices that reflect those circumstances, such as the CGFNS Alliance Code, serve to ensure ethical recruitment practices and prevention of brain drain or severe shortage.

Biography

Franklin A. Shaffer, EdD, RN, FAAN, FFNMRCSI, is President and CEO of CGFNS International, Inc. in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. He can be reached at fshaffer@cgfns.org. Mukul Bakhshi, JD, is Chief of Strategy and Government Affairs at CGFNS International. Kaley Cook, MS, is Program Coordinator, Alliance for Ethical International Recruitment Practices, and Thomas D. Álvarez, MS, is Senior Research Associate to the President and CEO at CGFNS International.

References

- 1.Behring S. Healthline; August 11, 2021. Understanding the American nursing shortage.https://www.healthline.com/health/nursing-shortage Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 2.Batalova J. Migration Policy Institute (MPI); May 14, 2020. Immigrant health-care workers in the United States.https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/immigrant-health-care-workers-united-states-2018 Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buchan J, Catton H, Shaffer F. Susatin and Retain in 2022 and Beyond: The Global Nursing Workforce and the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Centre on Nurse Migration, January 2022. Available at: https://www.icn.ch/system/files/2022-01/Sustain%20and%20Retain%20in%202022%20and%20Beyond-%20The%20global%20nursing%20workforce%20and%20the%20COVID-19%20pandemic.pdf. Accessed 10 March 2022.

- 4.United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA) International Migration 2020 Highlights. December 2020. https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/sites/www.un.org.development.desa.pd/files/undesa_pd_2020_international_migration_highlights.pdf Available at:

- 5.International Organization for Migration (IOM) COVID-19 Travel Restrictions Output – 12 July 2021. July 12, 2021. https://migration.iom.int/reports/covid-19-travel-restrictions-output-12-july-2021 Available at:

- 6.Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Contribution of migrant doctors and nurses to tackling COVID-19 crisis in OECD countries. OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19) May 1, 2020. https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/contribution-of-migrant-doctors-and-nurses-to-tackling-covid-19-crisis-in-oecd-countries-2f7bace2/ Available at:

- 7.Shaffer F., Bakhshi M., Farrell N., Álvarez T. Role of nurses in advancing the objectives of the global compacts for migration and on refugees. Nurs Adm Q. 2019;43(1):10–18. doi: 10.1097/NAQ.0000000000000328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization. Seventy-Fourth World Health Assembly Resolutions and Decisions. Available at: https://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA74-REC1/A74_REC1-en.pdf#page=27. May 24, 2021. Accessed June 1, 2021.

- 9.Ratha D., Kim E.J., Plaza S., Seshan G. Global Knowledge Partnership on Migration and Development (KNOMAD) via World Bank. Resilience: COVID-19 Crisis Through a Migration Lens. Migration and Development Brief 34. May 2021. https://www.knomad.org/sites/default/files/2021-05/Migration%20and%20Development%20Brief%2034_1.pdf Available at: Accessed Novemer 15, 2021.

- 10.World Bank Personal remittances received (% of GDP) – Philippines. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/BX.TRF.PWKR.DT.GD.ZS?locations=PH Available at:

- 11.American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN) Nursing shortage fact sheet. September 2020. https://www.aacnnursing.org/news-information/fact-sheets/nursing-shortage Available at:

- 12.Krogstad J.M., Dunn A., Passel J.S. Pew Research Center; August 23, 2021. Most Americans say the declining share of White people in the U.S. is neither good nor bad for society.https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/08/23/most-americans-say-the-declining-share-of-white-people-in-the-u-s-is-neither-good-nor-bad-for-society/ Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dos Santos L.M. Developing bilingualism in nursing students: learning foreign languages beyond the nursing curriculum. Healthcare. 2021;9(3):326. doi: 10.3390/healthcare9030326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barnard A., Ashford G., Vigdor N. New York Times; October 18, 2021. These health care workers would rather get fired than get vaccinated.https://www.nytimes.com/2021/09/26/nyregion/health-workers-vaccination.html Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Public Radio (NPR) 153 Hospital workers quit or were fired because they refused to get COVID vaccines. June 22, 2021. https://www.npr.org/2021/06/22/1009268874/153-hospital-workers-quit-or-were-fired-because-they-refused-to-get-covid-vaccin Available at:

- 16.U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) COVID-19 vaccination required for immigration medical examinations. September 14, 2021. https://www.uscis.gov/newsroom/alerts/covid-19-vaccination-required-for-immigration-medical-examinations Available at:

- 17.American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN) AACN Press Release; April 1, 2021. Student enrollment surged in U.S. schools of nursing in 2020 despite challenges presented by the pandemic.https://www.aacnnursing.org/News-Information/Press-Releases/View/ArticleId/24802/2020-survey-data-student-enrollment Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 18.NSI Nursing Solutions, Inc. (NSI) 2021 NSI national health care retention & RN staffing report. March 2021. https://www.nsinursingsolutions.com/Documents/Library/NSI_National_Health_Care_Retention_Report.pdf Available at:

- 19.Berlin G., Lapointe M., Murphy M., Viscardi M. McKinsey; May 11, 2021. Nursing in 2021: retaining the healthcare workforce when we need it most.https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/healthcare-systems-and-services/our-insights/nursing-in-2021-retaining-the-healthcare-workforce-when-we-need-it-most Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smiley R.A., Ruttinger C., Oliveira C.M., et al. The 2020 National Nursing Workforce Survey. J Nurs Regul. 2021;12(1 Suppl):S1–S96. [Google Scholar]

- 21.International Council of Nurses (ICN) ICN Press Release; January 13, 2021. The COVID-19 effect: world’s nurses facing mass trauma, an immediate danger to the profession and future of our health systems.https://www.icn.ch/news/covid-19-effect-worlds-nurses-facing-mass-trauma-immediate-danger-profession-and-future-our Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 22.Connor P. Pew Research Center; April 1, 2020. More than nine-in-ten people worldwide live in countries with travel restrictions amid COVID-19.https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/04/01/more-than-nine-in-ten-people-worldwide-live-in-countries-with-travel-restrictions-amid-covid-19/ Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reuters . Reuters; June 18, 2021. Philippines raises cap on health professionals going abroad.https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/philippines-raises-cap-health-professionals-going-abroad-2021-06-18/ Available at: [Google Scholar]