Summary

Background

HIV-TB treatment integration reduces mortality. Operational implementation of integrated services is challenging. This study assessed the impact of quality improvement (QI) for HIV-TB integration on mortality within primary healthcare (PHC) clinics in South Africa.

Methods

An open-label cluster randomized controlled study was conducted between 2016 and 2018 in 40 rural clinics in South Africa. The study statistician randomized PHC nurse-supervisors 1:1 into 16 clusters (eight nurse-supervisors supporting 20 clinics per arm) to receive QI, supported HIV-TB integration intervention or standard of care (control). Nurse supervisors and clinics under their supervision, based in the study health districts were eligible for inclusion in this study. Nurse supervisors were excluded if their clinics were managed by municipal health (different resource allocation), did not offer co-located antiretroviral therapy (ART) and TB services, services were performed by a single nurse, did not receive non-governmental organisation (NGO) support, patient data was not available for > 50% of attendees. The analysis population consists of all patients newly diagnosed with (i) both TB and HIV (ii) HIV only (among patients previously treated for TB or those who never had TB before) and (iii) TB only (among patients already diagnosed with HIV or those who were never diagnosed with HIV) after QI implementation in the intervention arm, or enrolment in the control arm. Mortality rates was assessed 12 months post enrolment, using unpaired t-tests and cox-proportional hazards model. (Clinicaltrials.gov, NCT02654613, registered 01 June 2015, trial closed).

Findings

Overall, 21 379 participants were enrolled between December 2016 and December 2018 in intervention and control arm clinics: 1329 and 841 HIV-TB co-infected (10·2%); 10 799 and 6 611 people living with Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV)/ acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) (PLWHA) only (81·4%); 1 131 and 668 patients with TB only (8·4%), respectively. Average cluster sizes were 1657 (range 170–5782) and 1015 (range 33–2027) in intervention and control arms. By 12 months, 6529 (68·7%) and 4074 (70·4%) were alive and in care, 568 (6·0%) and 321 (5·6%) had completed TB treatment, 1078 (11·3%) and 694 (12·0%) were lost to follow-up, with 245 and 156 deaths occurring in intervention and control arms, respectively. Mortality rates overall [95% confidence interval (CI)] was 4·5 (3·4–5·9) in intervention arm, and 3·8 (2·6–5·4) per 100 person-years in control arm clusters [mortality rate ratio (MRR): 1·19 (95% CI 0·79–1·80)]. Mortality rates among HIV-TB co-infected patients was 10·1 (6·7–15·3) and 9·8 (5·0–18·9) per 100 person-years, [MRR: 1·04 (95% CI 0·51–2·10)], in intervention and control arm clusters, respectively.

Interpretation

HIV-TB integration supported by a QI intervention did not reduce mortality in HIV-TB co-infected patients. Demonstrating mortality benefit from health systems process improvements in real-world operational settings remains challenging. Despite the study being potentially underpowered to demonstrate the effect size, integration interventions were implemented using existing facility staff and infrastructure reflecting the real-world context where most patients in similar settings access care, thereby improving generalizability and scalability of study findings.

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by South African Medical Research Council (SAMRC), and UK Government's Newton Fund through United Kingdom Medical Research Council (UKMRC).

Keywords: Mortality, Quality improvement, HIV, TB/HIV integration, Cluster randomized trial, Primary healthcare

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

Initially in 2013, Medline via PubMed was searched for articles published between 2003 and 2013 reporting on search terms: “epidemiology of HIV-TB co-infection”; “integrated HIV-TB care, TB case finding among people living with Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV)/ acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) (PLWHA)”; “isoniazid preventive therapy (IPT) and antiretroviral therapy (ART) uptake”; and “strategies for improving TB outcomes among patients HIV-TB in resource limited settings”, yielding 288 relevant published articles that suggested that co-location of TB and HIV services was alone insufficient to substantially improve integrated services, recommending additional interventions such as quality improvement (QI) targeting health systems performance improvements for evaluation. In 2015, an expanded search for articles published between 2003 and 2015, evaluating impact of QI mediated integrated TB and HIV services on improved patient outcomes, using the terms 'Quality Improvement' AND 'resource-constrained' AND 'HIV' AND tuberculosis, OR TB yielded zero findings. Since our search, two new trials have been published: the Merge trial found no patient outcome improvement with placement of additional staff supporting integrated HIV-TB care, and the TB-Fast Track trial found no short-term mortality reduction among PLWHA despite substantial increases in TB diagnosis and treatment coverage. Evidence guiding “how to” effectively implement integrated services at the frontline will optimize implementation of integrated services and help address persistently high mortality rates among HIV-TB coinfected individuals in resource limited settings.

Added value of this study

This is the first randomised trial to test a scalable HIV-TB integration strategy using QI methods. Despite the intervention, similarly high mortality rates among HIV-TB co-infected patients were found. Demonstrating mortality benefit from health systems process improvements in real-world operational settings remains challenging, with this study highlighting the high level of health systems planning and organization required for delivery of complex QI supported HIV-TB integration interventions. Having rural clinics with their existing facility staff participate in this research enabled a better understanding of whether the QI intervention could be translated irrespective of resources or setting. Despite failing to show an impact on HIV-TB mortality rates the study found the health system to be responsive to strategic implementation support, showing overall improvements in performance.

Implications of all the available evidence

Growing evidence shows that affordable and sustainable QI strategies offer strengthened integrated HIV-TB service delivery through establishment of clear guidelines that address weaknesses in PHC clinic systems. This trial evaluated the effect of QI intervention to optimise delivery of integrated TB and HIV services and improve patient health outcomes. Incorporation of QI strategies into routine support for PHC clinics to sustain improved patient health outcomes yielded no added benefit to patient outcomes.

Alt-text: Unlabelled box

Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB) is a leading opportunistic infection among people living with Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV)/ acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) (PLWHA). In 2018, 21% of the 1·2 million TB deaths occurred in PLWHA.1 In South Africa, approximately 300,000 new TB cases are notified each year with approximately 70% of cases occurring in PLWHA.2

Multiple clinical trials demonstrated survival benefits in PLWHA with cluster of differentiation 4 (CD4) < 50 cells/mm3 from early antiretroviral therapy (ART) initiation during TB therapy, providing impetus for integrated HIV and TB services.3, 4, 5 Guidelines from World Health Organization (WHO) recommend earlier ART initiation for everyone with TB and HIV, accounting for programmatic, logistical, and patient preference reasons.1

Additional interventions that reduce mortality among PLWHA include HIV and TB case detection, and Isoniazid preventative therapy (IPT).6 Despite adoption of these interventions in TB and HIV policies and treatment guidelines globally, knowledge on the extent to which implementation of integrated HIV and TB services occurs and its subsequent impact on mortality, remains elusive.

Prevention of TB disease among PLWHA remains a key strategy in reducing HIV-associated TB mortality. Published studies consistently report a statistically significant association between TB preventive therapy (TPT) uptake among PLWHA and reduced TB mortality.7 Despite widescale access to TPT, delays in facility level TPT policy implementation and inadequacies in health care worker (HCW) capacity commonly contribute to inadequate TPT uptake among PLWHA residing in resource limited settings.8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13

Universal health coverage would ensure that all eligible patients access the required TB and HIV related health services, that services are of high quality and sufficiently comprehensive to reduce morbidity and mortality. Delivery of comprehensive integrated services can be optimised through ongoing performance assessment and improvement using key indicators. This will help achieve alignment of integrated HIV and TB service delivery with population health profiles and clinical outcomes. Defining a scalable strategy to address shortcomings in TB and HIV screening, TB diagnostic testing, timely ART initiation, and TPT will help strengthen and support delivery of integrated TB and HIV services in endemic resource limited settings. The Scaling Up TB, and HIV Treatment Integration (SUTHI) study, assessed the impact of quality improvement (QI) supported TB and HIV treatment integration on mortality and clinical outcomes within 40 rural Primary Healthcare (PHC) clinics in South Africa.

Methods

Study design

This open-label, cluster randomized-controlled study, published elsewhere, was conducted over 18-months in the rural Ugu and King Cetshwayo districts, KwaZulu-Natal (KZN), South Africa.14,15 In this study, a cluster was defined as a PHC nurse supervisor. This individual typically managed one to five PHC clinics. The University of KwaZulu-Natal Biomedical Research Ethics Committee (UKZN BREC) approved the study, with waiver of participant informed consent {(ref no. BF108/14) and Clinicaltrials.gov, NCT02654613, registered 01 June 2015}.14

Participants and randomization

A master list of PHC nurse supervisors and their respective clinics within the selected local health districts were screened for study inclusion as per eligibility criteria published elsewhere.14 A total of 16 eligible PHC supervisors, each serving as a unit of randomization, were included in the study, and randomized 1:1 using computer-generated randomization code that was developed by a Statistician in SAS (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina) version 9.4. statistical software. No matching or stratification was used in the randomisation process. The randomization list was kept in a password protected file and the random allocation was sent to the study coordinator when all the preparations to enrol each PHC nurse supervisor and their respective clinic(s) were completed. Upon receipt of the randomization arm, the study coordinator initiated the documentation of the study arm allocation and shared that information with the study team including the statistician for verification purposes. Eight PHC nurse supervisors (n=eight clusters), supporting 20 clinics (total of 40 clinics in the study) were allocated to the QI intervention and standard of care (SOC) arms, respectively. Supervisors were excluded if their clinics were managed by municipal health (different resource allocation), did not offer co-located ART and TB services, services were performed by a single nurse, did not receive non-governmental organisation (NGO) support, patient data was not available for > 50% of attendees. As each PHC nurse supervisor managed multiple clinics, randomization at the PHC supervisor level helped address contamination of the control clinics by the studies’ intervention effects.

Study intervention implemented in intervention arm clinics

In this study, the QI intervention adopted the Breakthrough Series Collaborative (BTSC) model to support key aspects of HIV-TB service integration as published elsewhere.14,15 A collaborative was formed by PHC nurse supervisors, and QI teams comprising a clinic appointed QI champion supported by selected staff members including the clinics’ operations manager. This collaborative was expected to improve clinic performance on routine HIV-TB integration services measured by the following process indicators: HIV testing (especially in TB patients), TB screening, IPT initiation in new ART patients, ART initiation in TB patients, viral load testing at month 12, and implementation of an integrated electronic HIV and TB database as published elsewhere.15 The study QI intervention package comprised three key elements aimed at embedding HIV-TB integration within the clinics’ services: (i) healthcare worker training and capacity building; (ii) in-person QI mentorship; and (iii) Data quality improvement for improved completeness and reliability of routinely collected clinic data, published elsewhere.14,15 It is important to note that QI Interventions aimed at optimizing HIV-TB integration performance were not offered in a bundled approach. Time of introduction of tailored interventions corresponded to the urgency of the required intervention. Hence, interventions were initiated at various time points over the study period. Upstream activities in the HIV and TB care cascade took priority and were addressed in the first few months of implementing the study intervention. Tuberculosis and HIV process indicators that reached or exceeded 90% were considered “optimally performing” with no direct intervention implemented except for ongoing tracking and action should indicator performance drop to below 90%. Clinics prioritized indicator selection, based on baseline performance and ease of access to data.

Standard of care implemented in control arm clinics

South African Department of Health (DoH) guidelines recommend integrated HIV and TB services as SOC (control) and conducts programme monitoring through electronic medical records. Standard support for integrated HIV-TB services in SOC clinics included quarterly visits by the assigned PHC supervisor and district Health Management team, with performance review using routinely collected clinic data. In addition, the ministry of health convened monthly data review meetings called ‘Nerve centre meetings’, a platform for all facilities, i.e., both intervention and non-intervention clinics, to share performance on targeted HIV-TB service delivery indicators. NGO provided technical support to control clinics was not discouraged. Factors influencing background SOC were systematically recorded and accounted for in the final analysis.

Outcomes

All-cause mortality at 12-months from enrolment among newly diagnosed HIV-TB co-infected patients was the primary outcome of this study. To ascertain the primary outcome the rate of mortality in each cluster was calculated as the number of patients who died, divided by the total number of person-years at risk of mortality. Deaths were ascertained through tracing by facility staff, family member reports, clinic charts annotation, or through review of the South African national death registry, the only available national death registry. Reliability of the South African Death registry is, based on a deceased person having a valid South African ID. Hence, the system may not include immigrants or South African residents that demised without a valid South African ID. Follow-up time for each patient was calculated from date of enrolment to 12-months of longitudinal follow-up, or sooner if date of death, patient transfer-out, patient's last clinic visits in those lost-to-follow-up from care occurred before 12-months.

Data collection

Patient level data was collected six months prior to study enrolment (baseline) and follow-up study period for patients. Patients participating in this study included those: at least 18 years of age; newly diagnosed HIV-TB co-infected patients based on any bacteriologically confirmed or clinically diagnosed case of TB with a positive result or from HIV testing conducted at the time of TB diagnosis or other documented evidence of enrolment in HIV care; diagnosed with TB only based on a diagnosis with bacteriologically confirmed TB or who was started on TB treatment by a health care worker based on positive smear, microscopy, culture or rapid diagnostic tests for TB bacilli, clinical presentation, and/or radiologic evidence of TB; confirmed HIV-infected only based on two rapid HIV tests.3,16 Reports on HIV-TB integration process indicator performance were generated monthly from each clinics electronic data management systems. A roving study data team provided continuous data management QI activities in all intervention and control clinics. Data improvement activities included supervision of clinical staff and data capturers, training in accurate interpretation and capture of clinical and laboratory information, accurate completion of laboratory request forms, and support in capturing file backlogs onto electronic databases. Feedback on metrics of data quality were provided to clinic staff throughout study implementation. Quality assurance was achieved through regular patient chart review comparison against electronic records. Electronic records from intervention and control clinics were used in this analysis.

Statistical analysis

A case fatality rate of 15% in the control arm was assumed based on published local data.17 We assumed that the SUTHI study intervention would achieve at least half the mortality reduction of 56% achieved in clinical studies.3, 4, 5 We anticipate that about 6000 HIV-positive patients will be diagnosed with active TB in the study population during a 12-month period. This is based on the assumption that between 100 and 200 new TB and HIV co-infected patients are seen in each of the 40 clinics per year. This translates to an average of 350 patients per cluster (cluster sizes are expected to be unequal). Therefore, with eight clusters per arm, a between-cluster coefficient variation (CV) of 0·25 and a type I error of 5%, we estimated the power to detect a 30% reduction in all-cause mortality would be approximately 80%. When the CV is increased to 0.35, power drops drastically to 57%.

All analyses were performed according to the intention-to-treat (ITT) principle. This analysis population consists of all patients newly diagnosed with (i) both TB and HIV (ii) HIV only (among patients previously treated for TB or those who never had TB before) and (iii) TB only (among patients already diagnosed with HIV or those who were never diagnosed with HIV) after QI implementation in the intervention arm or enrolment in the control arm. No adjustments for multiple comparisons were carried out.

The demographic and clinical characteristics were summarized at an individual level and adjusted for clustering. At an individual level, descriptive summary measures were expressed as frequencies, and percentages for all variables, while the adjusted summaries were calculated as geometric means (GM) of cluster-specific proportions. Among HIV-TB co-infected patients, the timing of TB treatment or ART initiation was summarised and estimates not adjusted for clustering as inferential statistics were not drawn from these analyses.

Time at risk of death for each patient was calculated from the date of enrolment into care (which could be the date of HIV test, date of ART or TB treatment initiation, whichever occurred first), to either the date of patient death, transfer out, last clinic visit if lost-to-follow-up, or the month-12 cut-off date, whichever occurred first.

Mortality rate in each cluster was calculated as the number of patients who died, divided by the total number of person-years at risk of death. Thereafter, mortality rates in each of the intervention and control arms were calculated as GM of cluster-specific rates. Log cluster-specific mortality rates between study arms were compared using unpaired t-tests, with the confidence limits for mortality rates based on t-distribution. Mortality rate ratio (MRR), derived as a ratio of intervention to control arm mortality rates, was used to assess the effect of the intervention on mortality. Standard error for differences in log cluster-specific mortality rates between arms were obtained, and the 95% confidence interval (CI) from this standard error, using t-statistic with 14° of freedom were calculated. The t-test is robust in analysing cluster randomised studies with small number of clusters. This method has its own limitations because it gives equal weight to each cluster, meanwhile the calculation of weights is not always recommended for studies with a small number of clusters due to possible inaccuracies in between-cluster variance.18 However, due to huge variation in cluster sizes, we conducted a weighted cluster-level sensitivity analysis where optimal weights were calculated using the inverse variance method. A weighted t-test was used when comparing mortality rates between study arms.

A two-stage approach based on cluster level summaries was used to calculate an adjusted MRR. The potential confounders such as age, gender, baseline CD4 count (for newly diagnosed HIV patients) and the municipality district where clusters are located were included in the model. Since not all patients are expected to have CD4 count measurements, we fitted one model with and the other without the CD4 count. In the first stage, we ignored the clustering at PHC supervisor level and used multivariable Poisson regression with all potential confounders included in the model except for the study arm, to obtain the ratio of observed to expected events (i.e., log-residuals) for each cluster. In the second stage, we compared the log-residuals between the study arms by calculating the GM of the log-residuals in each arm and these were used in the derivation of the adjusted MRR. Inferences were also based on t-distribution. This analytical approach described is recommended for cluster randomized trials with small (<15) number of clusters per arm.18

Even though individual-level regression methods are not robust for cluster randomized studies with fewer clusters, we conducted a secondary analysis using Cox proportional hazards regression with random effects (frailty models) to determine the effect of QI on mortality after adjusting for baseline characteristics. These models take clustering by PHC clinic supervisor into account through the random effects and adjust for age, sex, baseline CD4 count (for newly diagnosed PLWHA), and district. Kaplan-Meier plots of cumulative probability of death were provided for exploratory purposes.

Performance of HIV-TB process indicators at baseline and post-intensive phase in the intervention and control arms were calculated as follows: First, the proportions per cluster were calculated by summation of numerators divided by the sum of the denominators of all respective clinics in a cluster per month. A proportion of zero was replaced with 0·00001 (or 0·001 when using percentages). If a denominator was zero (i.e., no one was eligible), then that month was ignored. Second, we calculated cluster-specific GM across months associated with a phase. Third, study arm-specific GM were calculated as cluster-specific proportions per phase. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina) version 9.4.

Role of funding source

The funders, South African Medical Research Council (SAMRC), and UK Government's Newton Fund through the United Kingdom Medical Research Council (UKMRC) had no role in the study design, study execution, analyses, data interpretation, or decisions to submit the study findings for publication. Kogieleum Naidoo, Santhanalakshmi Gengiah, Nonhlanhla Yende-Zuma, Regina Mlobeli, Jacqueline Ngozo, Nhlakanipho Memela, Nesri Padayatchi, Pierre Barker, Andrew Nunn, and Salim S. Abdool Karim decided to submit the paper for publication. Access to this studies’ dataset and data dictionary can be made via an online request lodged on the CAPRISA website: www.caprisa.org.

Results

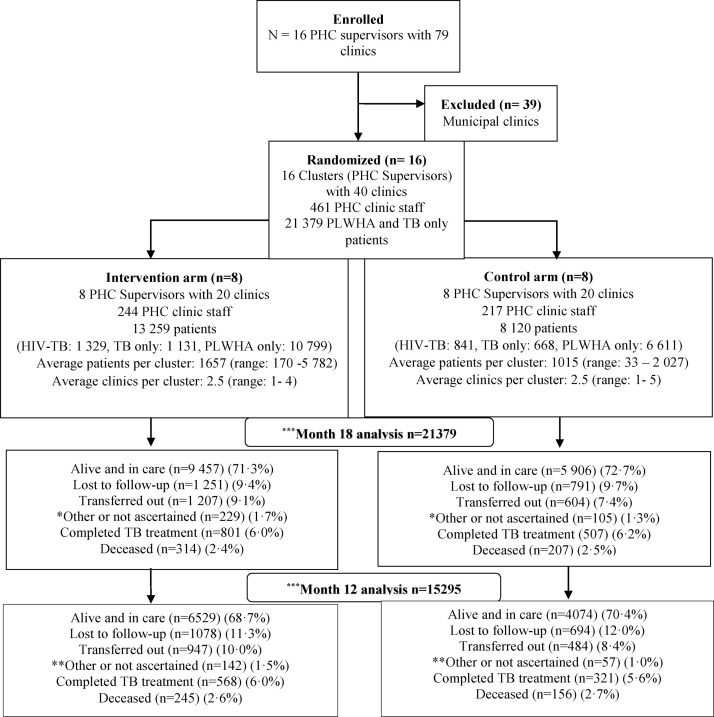

Between December 2016 and December 2018, 21 379 participants were enrolled: 13 259 (62·0%) in the intervention and 8 120 (38·0%) in control arms. Of the total enrolled: 2 170 (10·2%) were HIV-TB co-infected, 1 799 (8·4%) had TB only, and 17 410 (81·4%) were PLWHA (Figure 1 and Table 1).

Figure 1.

Randomization and follow-up of HIV-TB co-infected patients, TB only, and PLWHA only attending PHC clinics that were supervised by 16 PHC nurse supervisors (clusters) in the SUTHI study.

Table 1.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics in intervention and control arms patients enrolled under the ITT population in PHC clinics in the SUTHI study.

| Characteristics | Category | Intervention arm (N = 13,259) |

Control arm (N = 8120) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted n(%) | Adjusted for clustering (%) | Unadjusted n (%) | Adjusted for clustering (%) | ||

| Gender, n (%) | Female | 8465 (63·8%) | 64·4% | 5045 (62·1%) | 61·70% |

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 31 (25–39) | 30 (24–38) | |||

| Age group (years) at enrolment, n (%) | ≤15 | 336 (2·5%) | 3·1% | 320 (3·9%) | 4·6% |

| 16 - 25 | 3040 (22·9%) | 24·6% | 2178 (26·8%) | 26·7% | |

| 26 - 35 | 5452 (41·1%) | 38·1% | 3044 (37·5%) | 35·2% | |

| 36 - 45 | 2776 (20·9%) | 20·1% | 1501 (18·5%) | 18·3% | |

| > 45 | 1655 (12·5%) | 13·3% | 1077 (13·3%) | 13·8% | |

| Status, n (%) | HIV-TB co-infected | 1329ձ (10·0%) | 10·8% | 841ձ (10·4%) | 10·6% |

| TB only | 1131 (8·5%) | 8·2% | 668 (8·2%) | 9·10% | |

| PLWHA | 10,799γ (81·4%) | 80·40% | 6611γ 81·4%) | 78·80% | |

| CD4 count (cells/µL) among newly diagnosed HIV positive patients† | <200 | 1821 (15·5%) | 16·3% | 1192 (16·5%) | 16·7% |

| 200–350 | 1764 (15·0%) | 15·2% | 1168 (16·2%) | 17·8% | |

| 351–500 | 1565 (13·3%) | 14·3% | 959 (13·3%) | 11·8% | |

| >500 | 2242 (19·1%) | 19·3% | 1416 (19·6%) | 22·2% | |

| Ineligible for CD4* | 4324 (36·8%) | 30·9% | 2445 (33·8%) | 23·7% | |

| Missing* | 49 (0·4%) | 0·5% | 45 (0·6%) | 0·7% | |

| District, n (%) | King Cetshwayo | 7798 (58·8%) | … | 4162 (51·3%) | … |

| Ugu | 5461 (41·2%) | … | 3958 (48·7%) | … | |

| Area, n (%) | Urban | 7979 (60·2%) | … | 2864 (35·3%) | … |

| Rural | 5280 (39·8%) | … | 5256 (64·7%) | … | |

Excludes 1799 TB positive patient with no record of HIV infection and 590 HIV-TB co-infected patients who were not newly diagnosed with HIV at enrolment (i.e., either tested positive for HIV or started ART more than 6 months before clinic enrolment).

Amongst those with absent or missing CD4 count (n = 6 863): 56·9% were from the urban area; 67·2% were females; 90·6% were between the ages of 16 and 49 years and 56·0% are from KCD district.

8 HIV-TB co-infected patients in the intervention arm and 13 in the control arm did not initiate ART.

201 PLWHA (people living with HIV/AIDS) in the intervention arm and 160 in the control arm did not initiate ART.

€Classification of clinics into urban and rural was from a pre-exiting DoH classification received from the respective district office. IQR: interquartile range.

At baseline, the two study arms had similar demographic and clinical characteristics including rates of

HIV-TB co-infection, and proportion with advanced HIV at ART initiation (Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1). All participants in this study were Black African. Median CD4 count among newly initiated ART patients randomized to the intervention and control arms was 360 [interquartile range (IQR) 202–551], and 352 (IQR 198–545) cells/µL, respectively (data not shown). Median duration of follow-up for patients with TB only was 5.5 months (IQR 2·0–6·0), HIV-TB co-infected patients was 8·2 months (IQR: 4·2–12·8), and PLWHA only was 6.5 (IQR: 2·5–12·1) months (data not shown).

Average number of patients per cluster was 1657 (range 170–5782) and 1015 (range 33–2027), with 63·8% (8465) and 62·1% (5045) female patients, in the intervention and control arms, respectively (Figure 1). Average number of clinics per cluster was 2.5 in both study arms (Figure 1). More intervention arm patients lived in urban areas and more control arm patients lived in rural areas, 60·2% (7979) vs 64.7% (5256), and retention rates at study completion, retention was 89% in both arms (Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1).

Adherence to the QI intervention

The series of learning sessions that introduced QI interventions to learning collaboratives commenced on 01 December 2016 for the first session and involved six PHC clinics, followed by the second and third sessions on 23 February 2017 and 8 June 2017 for nine and five PHC clinics, respectively. A total of 510 out of an anticipated 600 QI visits (85%) were conducted published elsewhere.15 Specific HIV-TB services in intervention clinics that were already achieving optimal performance levels benefitted from study supported performance monitoring only. Intervention clinics that were already achieving optimal performance levels of HIV-TB services e.g., 17 clinics benefitted from study supported performance monitoring only and did not receive direct QI intervention for optimally performing these services. Within the intervention arm, active QI intervention was required in three clinics to improve ART initiation, 12 clinics to improve HIV testing, 17 clinics to improve TB screening, and in all 20 clinics to improve IPT initiation (data not shown).

Minimal improvement intervention was required for ART initiation in eligible patients (Supplementary Table 4), whereas TB screening and viral load testing performance required active QI intervention yielding performance improvements of 83·4%and 72·2% respectively in both services. IPT initiation improved by 45% in the intervention arm compared to 9% in the control arm (Supplementary Table 2).

Timing of ART in TB patients

Among 1329 intervention arms HIV-TB co-infected patients: 740 (55·7%) were diagnosed with either HIV or TB and started ART and TB treatment after enrolment; 545 (41·0%) started ART before enrolment and started TB treatment after enrolment; 44 (3·3%) started TB treatment before enrolment and ART thereafter (data not shown). Among 740 co-infected patients that initiated therapy after enrolment, 449 (60·7%) were newly diagnosed TB and started TB treatment first, followed by ART at a median of 18 days (IQR 14–30) (data not shown). All other patients were known PLWHA in care diagnosed with TB and initiated on TB therapy at varying points after enrolment. Among PLWHA in the intervention arm 8/1329 HIV-TB co-infected, 201/10799 PLWHA only, did not initiate ART (Table 1).

Among the 841 co-infected control arm patients: 485 (57·7%) were diagnosed with either HIV or TB and started ART and TB treatment after enrolment; 331 (39·4%) started ART before enrolment and started TB treatment after enrolment; 25 (3·0%) started TB treatment before enrolment and ART thereafter (data not shown). Among 485 co-infected patients, only 285 (58·0%) started TB treatment followed by ART at a median of 18 days (IQR 14–28) (data not shown). People living with HIV/AIDS in care were diagnosed with TB and initiated on therapy at varying points after enrolment (data not shown). Among PLWHA in the control arm 13/841 HIV-TB co-infected, 160/6611 PLWHA only, did not initiate ART (Table 1).

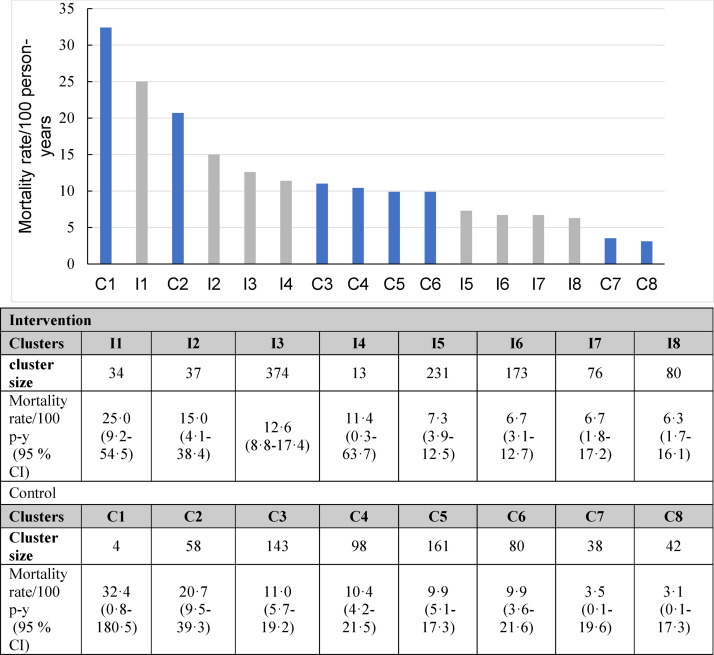

Mortality analysis within 12 months of study enrollment

A total of 245 and 156 deaths occurred over 6406 and 3880 person-years of follow-up, in the intervention and control arms, respectively (Table 2). Cluster-specific mortality rates among HIV-TB co-infected patients ranged from 6·3 to 25·0 per 100 person-years in the intervention arm and 3·1 to 32·4 to per 100 person-years in the control arm (Figure 2). The overall between-cluster coefficient of variation (CV) derived across all 16 clusters was 0.78 (data not shown). After combining all patients irrespective of their TB and HIV status, the cluster-specific mortality rates ranged among all from 2·9 to 7·4 per 100 person-years in the intervention arm and 2·1 to 6·2 per 100 person-years in the control arm (Supplementary Figure 1). Supplementary Figure 2 (A and B) shows timing of deaths after enrollment in both study arms.

Table 2.

Mortality rates in person-years (p-y) per study arm from the ITT population: overall and stratified by TB and HIV status at enrolment.

| All patients |

HIV-TB co-infected |

PLWHA only |

TB only | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention arm | Control arm | Intervention arm | Control arm | Intervention arm | Control arm | Intervention arm | Control arm | |

| Number of participants | 9509 | 5786 | 1018 | 624 | 7714 | 4744 | 777 | 418 |

| Deaths/person-years | 245/6406·14 | 156 /3880·33 | 77/781·22 | 48 /465·11 | 119/5286·57 | 72 /3216·93 | 49/338·36 | 36 /198·28 |

| Main analyses: Cluster-adjusted estimates (unweighted) | ||||||||

| Mortality rate/ 100 p-y (95% CI) | 4·5 (3·4–5·9) | 3·8 (2·6–5·4) | 10·1 (6·7–15·3) | 9·8 (5·0–18·9) | 2·6 (1·8–3·7) | 2·2 (1·2–4·3) | 18·2 (10·8 –30·7) | 18·3 (13·9–24·1) |

| Mortality rate ratio (95% CI) | 1·19 (0·79–1·80) | 1·04 (0·51–2·10) | 1·16 (0.59–2·26) | 0·99 (0·58–1·70) | ||||

| Sensitivity analyses: Cluster-adjusted estimates (inverse variance weighted) | ||||||||

| Mortality rate/ 100 p-y (95% CI) | 4·4 (3·4––5·8) | 3·7 (2·6–5·3) | 9·7 (6·5–14·6) | 9·1 (5·0–16·8) | 2·6 (1·8–3·7) | 2·2 (1·2–4·1) | 16·1 (10·0–25·9) | 17·5 (14·1–21·7) |

| Mortality rate ratio (95% CI) | 1·19 (0·79–1·80) | 1·07 (0·55–2·09) | 1·17 (0·59–2·30) | 0·92 (0·59–1·44) | ||||

PLWHA: people living with HIV/AIDS.

Figure 2.

Cluster-specific mortality rates in the intervention (I) and control (C) arm clinics among HIV-TB co-infected, with confidence interval (CI), person-years (p-y) and colours gray and blue representing clusters in the intervention and control arms, respectively.

Main analyses

Among HIV-TB co-infected patients overall mortality rate was 10·1 (95% CI 6·7–15·3) cases per 100 person-years in the intervention arm and 9·8 (95% CI: 5·0–18·9) per 100 person-years in the control arm, (mortality-rate ratio, 1·04; 95% CI, 0·51 to 2·10) (Table 2). Using two-stage approach, an adjusted MRR of 1·76 (95% CI: 0·62–4·96) and 2·05 (95% CI: 0·66–6·34) was obtained when modelled with and without CD4 count data (data not shown).

Sensitivity analyses

Weighted mortality rates were 9·7 (95% CI: 6·5–14·6) and 9·1 (95% CI: 5·0–16·8) cases per 100 person-years; mortality rate-ratio, 1·07 (95% CI: 0·55–2·09) (Table 2). Similarly, results from the two-stage approach produced weighted MRRswere 1·39 (95% CI: 0·62–3·12) and 1·54 (95% CI: 0·63–3·74) when modelled with and without CD4 count data (data not shown). Results for PLWHA only and TB only patients are shown in Table 2. Moreover, cluster-adjusted mortality rates, stratified by different baseline characteristics are shown in Supplementary Table 3.

Secondary analyses

In a secondary multivariable analyses of HIV-TB co-infected patients, the hazard of death was 8% lower in the intervention arm compared to the control arm (model without CD4 count; adjusted hazard ratio (HR)=0·92, 95% CI: 0·63–1·33) (Supplementary Table 4). The model with CD4 count data produced similar results (Supplementary Table 4). Within the ITT population, additional analysis of crude case fatality rates by demographic and clinical characteristics was 1.3% vs 3.4% in urban vs rural control arm clinics, was 8.6% vs 6.3% among TB only patients in control versus intervention arm clinics, and 4.9% vs 5.7% among PLWHA with CD4 counts < 200 cells/µL in intervention versus control arm clinics, respectively (Supplementary Table 5).

Discussion

Published guidelines for collaboration of TB and HIV services encourages physical integration of HIV-TB services, incorporation of TB diagnostic services into HIV care, and appropriate TB and HIV treatment, however implementation of these guidelines are variable and often sub-optimal.2 This study demonstrated that a QI-mediated model of integrated HIV-TB services had no statistically significant impact on mortality rates compared to the standard approach to HIV-TB services. Similarity in mortality rates observed in the study arm by 12-months follow-up show very high rates of ART and TB treatment initiation and relatively low death rates in both arm in both intervention and control clinics. Possible explanations for the lack of statistically significant differences include the high quality of HIV-TB integration in the control arm, a positive reflection of the South African DoH efforts. In addition, mortality outcomes are complex and driven by several healthcare and patient-related factors, which suggests that a QI-intervention alone may not be sufficient to reduce deaths in HIV-TB patients. Other reasons for study arms not following the hypothesized mortality rates include (i) extremely large clinic sizes with large staff complement and less organised services within intervention arm clinics potentially diluting the impact of the QI intervention, (ii) potential contamination of control arm clinics through data quality improvement efforts, (iii) sharing of change ideas at joint meetings attended by both intervention and control clinic staff, and NGO support staff, (iv) bias in data collection i.e. more deaths being recorded in the intervention arm via more intense retention efforts, and (v) the health system reflected in SOC clinics was already using a fair amount of QI methodology as SOC, this could have been compounded by the potential bias of the study's exclusion criteria to select SOC clinics that were already optimally performing in delivery of process indicators. Furthermore, rural, and urban imbalances, created by randomizing at the PHC level likely influenced HIV-TB service delivery creating differential impact of the intervention on mortality.

Other implementation science intervention studies aimed at reducing HIV-TB mortality rates by improving integrated services through other non-QI health system interventions showed similar results to those observed in this study.13,19 Importantly, mortality rates observed in this operational study is higher than mortality rates observed among patients receiving integrated HIV-TB treatment within controlled clinical trial.3, 4, 5 In this study, we observed a 4% harm, however a protection ranging from 49% protection to a 110% harm was compatible with our data. In the MERGE cluster-randomized study conducted in South African PHC clinics, additional clinical staff supporting integration TB and HIV provided no added hospitalisation, death, or retention rate benefit in the intervention arm clinics.12 Incidence of hospitalisation or death at 12 months of follow-up observed in the MERGE study in PLWHA, of whom 16·5% were co-infected with TB, and among TB patients, approximately 80% of whom were PLWHA, was 12·5 and 17·1 per 100 person-years, respectively.12 Additional data from a cluster randomized study evaluating improved quality of care through on-site educational outreach to nurses providing TB and HIV care in 15 primary health care clinics found little survival benefit from improved quality of integrated care.20 Lower mortality rates among both SUTHI study arms compared to other published literature emphasises South Africa's robust efforts to attain the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) 90-90-90 goals for epidemic control and improve population level impact of public access to ART services.

Integrated TB case finding and IPT initiation among PLWHA did not result in statistically significant difference in mortality rates between intervention and control arms in our study. Published literature reporting the effectiveness of TB screening and prevention services on mortality of PLWHA only individuals receiving care in operational settings are few. While we observed mortality rates among PLWHA to be far lower than 83·2 per 1000 person-years observed in historic cohorts, levels of 2·6 per 100 person-years observed in our study is still far higher than the UNAIDS estimates of HIV related mortality of 0·06 per 1000 infected patients for our setting.21,22 Our data undoubtedly reflects the true performance of the local ART treatment programme evident in our finding of similar HIV mortality rates observed in the intervention and control arms of this study. Comparable mortality rates of 2·1–2·8 per 100 person-years in 2012 and 2017 was also observed in Canada, Ethiopia, and elsewhere in South Africa, whereas data from studies conducted in Georgia and Japan were surprisingly two-fold and ten-fold higher respectively, highlighting that favourable ART outcomes are achievable in high burden resource limited settings.23, 24, 25, 26, 27

Data from randomized controlled clinical trials collectively demonstrate impact of ART in HIV-TB co-infected patients, TB and HIV case finding and entry into the continuum of care, and IPT to reduce HIV-associated TB mortality and morbidity.3, 4, 5,7 Conversely, data from operational research demonstrates that strengthened service delivery measured by improved HIV-TB integration process indicators did not confer a consistent or substantial reduction in mortality.28,29 This suggests that to improve outcomes in TB and HIV services, a combination of comprehensive coverage of service coupled with higher levels of systems performance in implementing the most effective and appropriate processes, is required. Strengthening quality of care for TB patients and PLWHA through robust coverage of requisite process indicators, i.e., timely patient identification, treatment initiation and retention in care may enable health systems to perform better in impacting health outcomes and reducing death.

We do however acknowledge several limitations in the study and in the intervention. The study was likely underpowered to detect 30% effect size or any other clinically meaningful effect size. The observed between-cluster coefficient of 0·78 was higher than 0.25 that was used in sample size and power calculations. In as much as heterogenous clusters may increase the generalisability of our findings. However, a huge between-cluster coefficient of variation is likely to reduce the power and precision of the trial more especially when there are fewer clusters. Furthermore, our cluster sizes were smaller than expected which resulted in a further reduced likelihood of showing an effect since the cluster size and statistical power are positively correlated, while the coefficient of variation and statistical power are inversely correlated. Unfortunately, the shortage of cluster randomised trials that have published coefficient of variation estimates may have led to a potentially underpowered study. The progressive reduction in TB caseloads seen provincially and nationally over the study period, undermined our ability to enrol the anticipated 6000 HIV-TB co-infected participants, limiting our ability to show differences in mortality between study arms. At Nurse supervisors were not matched to patient volume, hence, clusters have both high and low volume clinics. Nurse supervisors are allocated clinics based on geographic location, creating an urban rural bias in cluster distribution. The rural and urban imbalance between the arms likely influenced clinic size and ability to identify and address gaps in the care cascade. While it is possible that staff working in smaller clinics are better able to coordinate efforts and improve service delivery this study is unable to comment on impact of clinic size on outcomes. We note the shift in differences of mortality rates and performance outcomes between intervention and control arm clinics, initially large at the start of the study but reduced over time. This may indicate possible contamination of the intervention effects to control arm clinics with convergence in performance and outcomes observed around month eight. Additional study limitations included inadequate resource provision for data management support. Process indicators evaluating impact, outcome, and remedial interventions for complex study interventions require intensive data management investments to augment the prevailing weak systems within health facilities. Insufficient data management investments by the study and the health department, contributed to delayed detection of health systems inadequacies in implementing HIV-TB integration, and delayed deployment of interventions to address these. Poor routine clinic data management systems also weakened health facilities’ action for tracing patients undermining retention- in-care efforts. Lack of unique patient identifiers that facilitate linking patients between databases, and between facilities likely contributed to loss-to-follow-up overestimation. Study intervention limitations include introduction of HIV-TB integration interventions at various points in the study leading to inability to assess the true impact of interventions commencing close to clinic exit from the study. This may be especially true for assessing the impact of our interventions on the primary endpoint. Outside of the time constrained research setting, it may be possible to test an alternate QI strategy or evaluate whether critical parts of the process pathway selected, were missed. Variance in cluster size in this study may have introduced bias in our results, as suggested in published literature.30 However, it is unlikely to have resulted in significant bias as cluster size and mortality rates observed in this study are not correlated. In addition, the intervention arms comprised large clusters, resulting in large weights being assigned. Incorporating weights in the analyses did not change the direction of the results since the smaller clusters of HIV-TB co-infected participants in both armshad high mortality rates. While weighting could improve precision, our small number of clusters, and high variability between clusters, it is possible that weights were not properly calculated. This was further compounded by lack of available reliable estimates of between-cluster variance.

Our observation of converging probability of death in the intervention and control arms at approximately 8 months post study start suggests contamination of the intervention effects on the control arm. Randomization at the level of the PHC supervisor was done to align with their traditional support role and to reduce contamination. However, involvement of district leadership and management may have inadvertently introduced contamination to control arm clinics, undermining our ability to show outcome differences between study arms.

Despite these limitations there are several important strengths of this study worth noting. Firstly, integration interventions were implemented through capacitating existing facility staff to help identify and develop local solutions to address individual clinic needs and organisational shortcomings in delivering integrated HIV-TB services. Secondly, the cluster randomised study design enabled evaluation of the effectiveness and scalability of the integration intervention conducted at a community level. Thirdly, the study was conducted in both rural and urban PHC clinics reflecting the real-world context where most patients in endemic resource limited settings access care, improving generalizability of the study findings to similar settings. Lastly, the length of study follow-up enabled assessment of the durability of the intervention effects to help inform scale-up.

Furthermore, the SUTHI study contributes many learned lessons for future QI research and for implementation of integrated HIV-TB services delivery. While HIV-TB co-infected patients did not benefit from this simple intervention, it is both practical and implementable to support guideline translation within clinical settings using evidence-based QI implementation strategies. Cluster randomized trials on integrated HIV-TB services have not demonstrated appreciable reductions in mortality due to the substantive interaction of clinical, operational, and environmental variables. We further highlight the need for tailored health systems support interventions guided by facility type, geographic area, existing staff, skill, and resources to ensure sustained optimal performance.

Patients accessing care for HIV and TB disease in endemic settings require additional routine systematic tuberculosis and HIV screening, rapid TB treatment initiation, timely ART initiation, and implementation of IPT, requiring high levels of health systems performance to achieve sustained quality of care. Our study found no difference in reduction in mortality among HIV-TB co-infected patients receiving QI supported HIV-TB integration. Notwithstanding, our study highlights the need for consistent, sustained support for optimised integrated HIV-TB services delivery. Aligned with the principles of universal health coverage, improvements in health systems performance in finding and appropriately treating TB and HIV is urgently warranted to address the persistently high morbidity and mortality rates from these diseases in endemic settings.

Declaration of interests

Kogieleum Naidoo, Santhanalakshmi Gengiah, Nonhlanhla Yende-Zuma, Regina Mlobeli, Nhlakanipho Memela, Nesri Padayatchi, and Salim S. Abdool Karim report grants from Newton Fund through UKMRC and SAMRC, during the conduct of the study. The authors declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

Contributors

KN, AN, PB, SSAK, NYZ designed the study. KN is the grant holder. KN drafted the manuscript. KN, SG, and NM led the study implementation, participant recruitment and data collection. NYZ conducted statistical analysis and management of all study data. NYZ, KN, and SSAK analysed and interpreted all study data. All authors critically reviewed this manuscript for important intellectual content and approved publication.

Data sharing

CAPRISA has an established procedure to make its research data more broadly available. Information on the process for requesting and obtaining data is available on the CAPRISA website (www.caprisa.org). Datasets used for the analyses for the CAPRISA research article that has been published, can be requested by any investigator through an online request lodged on the CAPRISA website the request will be assessed by the CAPRISA Scientific Review Committee, and once approved the datasets, study protocol and statistical analysis plan will be made available to interested investigators making the request. In line with standard data access principles, CAPRISA will ensure that metadata on the datasets and other relevant documents will be made available. Measures to ensure anonymization of participant data will be taken to protect individual and personally identifiable information in shared datasets. In addition, summary results of the trial will also be made publicly available in a timely manner by posting to the results section of the clinical trial registry and papers will be made available through UKZN's research space (for non-NIH studies) within 12 months of publication.

Acknowledgments

The research reported in this publication was supported by the South African Medical Research Council with funds received from the South African National Department of Health, and the UK Medical Research Council, with funds received from the UK governments Newton Fund. This UK funded award is part of the EDCTP2 programme supported by the European Union.

We acknowledge the Ugu and KCD District Management Teams including PHC clinic staff and nurse supervisors, the KZN TB program, Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) staff who participated in this study providing QI support, SUTHI field teams in the Ugu and KCD Districts, Dr Anneke Grobler for her input into study design, Dr Kelechi Elizabeth Oladimeji for her assistance with study set-up, and BroadReach Healthcare for their supportive role within study clinics as specified in their health systems strengthening (HSS) grant awarded to them by USAID (Cooperative Agreement No. AID-674-A-12-00016).

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.eclinm.2022.101298.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.World Health Organization . World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2019. Global Tuberculosis Report 2019. World Health Organization. Available from http://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/en/. Last Accessed December 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Naidoo K., Rampersad S., Karim S.A. Improving survival with tuberculosis & HIV treatment integration: a mini review. Indian J Med Res. 2019;150(2):131. doi: 10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_660_19. Last Accessed December 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abdool Karim S.S., Naidoo K., Grobler A., et al. Timing of initiation of antiretroviral drugs during tuberculosis therapy. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(8):697–706. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0905848. Last Accessed December 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Havlir D.V., Kendall M.A., Ive P., et al. AIDS clinical trials group study A5221. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(16):1482–1491. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1013607. Last Accessed December 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blanc F.X., Sok T., Laureillard D., et al. Earlier versus later start of antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected adults with tuberculosis. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(16):1471–1481. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1013911. Last Accessed December 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Telisinghe L., Ruperez M., Amofa-Sekyi M., et al. Does tuberculosis screening improve individual outcomes? A systematic review. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;40 doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.101127. Last Accessed December 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Temprano ANRS 12136 Study Group A study of early antiretrovirals and isoniazid preventive therapy in Africa. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(9):808–822. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1507198. Last Accessed December 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ayele H.T., van Mourik M.S., Bonten M.J. Effect of isoniazid preventive therapy on tuberculosis or death in persons with HIV: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Infect Dis. 2015;15(1):334. doi: 10.1186/s12879-015-1089-3. Last Accessed 7 July 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ousley J., Soe K.P., Kyaw N.T.T., et al. IPT during HIV treatment in Myanmar: high rates of coverage, completion, and drug adherence. PHA. 2018;8(1):20–24. doi: 10.5588/pha.17.0087. Last Accessed December 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Avoka V.A., Osei E. Evaluation of TB/HIV collaborative activities: the case of South Tongu District, Ghana. Tuberc Res Treat. 2020;2020 doi: 10.1155/2020/4587179. Last Accessed December 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wiysonge C.S, Middelkoop K, Naidoo K, Nicol L, Padayatchi N. Evidence to inform South Africa tuberculosis policies (EVISAT) project. A systematic review of the epidemiology of and programmatic response to tuberculosis in HIV-infected patients in South Africa. UNAIDS 2014. Last Accessed December 2021

- 12.Kufa T., Fielding K.L., Hippner P., et al. An intervention to optimise the delivery of integrated tuberculosis and HIV services at primary care clinics: results of the MERGE cluster randomised study. Contemp Clin Stud. 2018;72:43–52. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2018.07.013. Accessed December 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grant A.D., Charalambous S., Tlali M., et al. Algorithm-guided empirical tuberculosis treatment for people with advanced HIV (TB fast track): an open-label, cluster-randomised study. Lancet HIV. 2020;7(1):e27–e37. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(19)30266-8. Last Accessed December 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Naidoo K., Gengiah S., Yende-Zuma N., et al. Addressing challenges in scaling up TB and HIV treatment integration in rural primary healthcare clinics in South Africa (SUTHI): a cluster randomized controlled trial protocol. Implement Sci. 2017;12(1):129. doi: 10.1186/s13012-017-0661-1. Last Accessed December 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gengiah S., Barker P.M., Yende-Zuma N., et al. A cluster-randomized controlled trial to improve the quality of integrated HIV-tuberculosis services in primary healthcare clinics in South Africa. J Int AIDS Soc. 2021;24(9):e25803. doi: 10.1002/jia2.25803. Last Accessed December 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.World Health Organization . World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2013. Definitions and Reporting Framework for Tuberculosis–2013 Revision: updated December 2014 and January 2020.https://www.who.int/tb/publications/2019/diagnose_tb_hiv/en/ Last Accessed December 2021; Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 17.Massyn N., Peer N., Padarath A., Barron P., Day C. Health Systems Trust; Durban: 2015. District Health Barometer 2014/2015.https://www.hst.org.za/publications/District%20Health%20Barometers/District%20Health%20Barometer%202014-15.pdf Last Accessed December 2021; Available from. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hayes R.J., Moulton L.H. Chapman and Hall/CRC; 2009. Cluster Randomised Studies. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bassett I.V., Coleman S.M., Giddy J., et al. Sizanani: a randomized study of health system navigators to improve linkage to HIV and TB care in South Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;73(2):154. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001025. Last Accessed December 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zwarenstein M., Fairall L.R., Lombard C., et al. Outreach education for integration of HIV/AIDS care, antiretroviral treatment, and tuberculosis care in primary care clinics in South Africa: PALSA PLUS pragmatic cluster randomised study. BMJ. 2011;342 doi: 10.1136/bmj.d2022. d2022. Last Accessed December 2021; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnson L.F., Mossong J., Dorrington R.E., et al. Life expectancies of South African adults starting antiretroviral treatment: collaborative analysis of cohort studies. PLoS Med. 2013;10(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001418. Last Accessed December 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.UNAIDS, 2020. UNAIDS global HIV & AIDS statistics–2019 fact sheet. Geneva, Switzerland: UNAIDS. Last Accessed 29 October 2020; Available at: https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/fact-sheet

- 23.Belay H., Alemseged F., Angesom T., Hintsa S., Abay M. Effect of late HIV diagnosis on HIV-related mortality among adults in general hospitals of Central Zone Tigray, northern Ethiopia: a retrospective cohort study. HIV/AIDS(Auckl) 2017;9:187. doi: 10.2147/HIV.S141895. Last Accessed December 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cheung C.C., Ding E., Sereda P., et al. Reductions in all-cause and cause-specific mortality among HIV-infected individuals receiving antiretroviral therapy in British Columbia, Canada: 2001–2012. HIV Med. 2016;17(9):694–701. doi: 10.1111/hiv.12379. Last Accessed December 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vandormael A., Cuadros D., Kim H.Y., Bärnighausen T., Tanser F. The state of the HIV epidemic in rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa: a novel application of disease metrics to assess trajectories and highlight areas for intervention. Int J Epidemiol. 2020;49(2):666–675. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyz269. Last Accessed December 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chkhartishvili N., Chokoshvili O., Bolokadze N., et al. Late presentation of HIV infection in the country of Georgia: 2012-2015. PLoS One. 2017;12(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0186835. Last Accessed December 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nishijima T., Inaba Y., Kawasaki Y., et al. Mortality and causes of death in people living with HIV in the era of combination antiretroviral therapy compared with the general population in Japan. AIDS (London, England) 2020;34(6):913. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000002498. Last Accessed December 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pepper D.J., Schomaker M., Wilkinson R.J., de Azevedo V., Maartens G. Independent predictors of tuberculosis mortality in a high HIV prevalence setting: a retrospective cohort study. AIDS Res Ther. 2015;12(1):35. doi: 10.1186/s12981-015-0076-5. Last Accessed December 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Burnett S.M., Zawedde-Muyanja S., Hermans S.M., Weaver M.R., Colebunders R., Manabe Y.C. Effect of TB/HIV integration on TB and HIV indicators in rural Ugandan health facilities. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2018;79(5):605. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001862. Last Accessed December 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lauer S.A., Kleinman K.P., Reich N.G. The effect of cluster sizevariability on statistical power in cluster-randomized study. PLoS One. 2015;10(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0119074. Last Accessed December 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.