Abstract

Introduction

Psoriasis is a chronic, autoimmune, inflammatory skin disease affecting 2–4% of the general population, which nowadays is even perceived as a systemic illness. The nature of this dermatosis may negatively influence patients’ general condition, life expectancy, and quality of life, which highlights the severity of the problem and the need to perform further investigation. We aimed to assess quality of life, stress severity, and physical activity of patients with psoriasis in relation to demographic and clinical data and comparison to the control group without dermatoses.

Methods

A set of surveys was conducted in 56 patients with psoriasis hospitalized at the Department of Dermatology, Medical University of Bialystok. Questionnaires used involved the Dermatology Life Quality Index, WHO Quality of Life questionnaire, International Questionnaire of Physical Activity, and a self-invented stress survey. Obtained data were compared to a sex- and age-matched control group without dermatoses. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism.

Results

Patients with psoriasis were found to be significantly less satisfied with their health and had lower scores in WHO social, environmental, and psychological domains, comparing to controls. Patients reported higher stress severity and lower satisfaction with sex life and physical appearance than controls. Patients with psoriasis also tended to perform less intensive physical activity than controls.

Conclusions

This study highlights the perception of psoriasis as not only affecting skin but also having a multifactorial impact on psychological and internal condition. Described lifestyle abnormalities can be easily evaluated with validated questionnaires, which could be introduced to patients in order to raise their awareness of comorbidities and mobilize them to modify incorrect lifestyle habits. Screening for other disorders and introduction of a holistic approach to every patient could be beneficial because the improvement of patients’ life quality is one of the most important issues.

Keywords: Psoriasis, Life quality, Social life, Physical activity, Sex life, Quality of life, Physical appearance

Key Summary Points

| Why carry out this study? |

| Psoriasis is one of the most common chronic skin diseases, which is a great medical, social, and economic problem nowadays. It leads to shorter life expectancy and is accompanied by multiple comorbidities; therefore studies investigating patients with this dermatosis are needed in order to better manage these persons. |

| We presume that patients with psoriasis have decreased quality of life, lower satisfaction with different life domains, and they require psychological support. We would like to add our own contribution to the current state of knowledge on this subject. |

| What was learned from the study? |

| Patients with psoriasis have decreased quality of life, lower satisfaction with their sexual life and physical appearance, experience greater stress, and are not able to take physical activity to the same extent as people free from skin diseases. |

| We suggest that psychosocial aspects should be analyzed in patients with psoriasis on a regular basis and they probably should undergo screening with simple tests, such as we performed, to identify subjects who require special attention. This matter requires more in-depth research on larger cohorts to establish reliable guidelines. |

Introduction

Psoriasis is a chronic autoimmune, inflammatory disease which affects 2–4% of people worldwide. It is characterized by the presence of papules, scales, infiltration, and erythema; hair scalp and nails can also be involved [1]. Skin lesions are not just an esthetic defect. They can cause severe subjective symptoms such as intensive pruritus or pain [1]. Psoriasis is also known as a systemic disease accompanied by multiple comorbidities [1]. First of all, it is associated with psoriatic arthritis (PsA) which affects about 5–40% of people with psoriasis and frequently leads to physical impairment. Not only do patients who develop PsA have to take medications but they also require time-consuming rehabilitation of the locomotor system and sometimes specific devices in order to improve moving ability [2]. Similar to PsA, a specific subtype of psoriasis—acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau—may lead to manual function impairment [3]. Besides PsA, psoriasis is also associated with different cardiometabolic disorders (CMDs) which result in high cardiovascular risk and therefore greater mortality. People with psoriasis are more frequently affected by arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus, coronary artery disease, dyslipidemia, obesity, and metabolic syndrome [4–6]. The multifactorial relation between psoriasis and obesity leads to acceleration of systemic inflammation, development of CMDs but also often to intensification of skin lesions, decreased activity, stigmatization, and poor eating habits or psychological disorders. Some publications have confirmed the decreased quality of life of patients with psoriasis [7, 8] and more frequent depression, anxiety, or alcohol abuse [4, 8]. One study reported the hazard ratio of the clinical diagnosis of depression in patients with psoriasis to be 1.39, anxiety 1.31, and suicidal thoughts 1.44 [9]. Moreover, research revealed that the quality of life of patients with psoriasis is comparable to that observed in patients with different chronic internal diseases, such as arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and cancer [10]. Psoriasis may be therefore nowadays perceived as some kind of psychosomatic disorder [8]. This skin disease has been also associated with various sleep disorders which we proved in recently published research [11]. Decreased sleep quality, increased risk of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome, and more severe symptoms of restless legs syndrome negatively influence patients’ ability to sleep and rest which exacerbates mental and also physical deterioration and worsen quality of life [12].

Taking into account subjective symptoms related to skin lesions, comorbidities and often time-consuming or cost-effective treatment have a great impact on the decreased quality of life of patients with psoriasis. It was reported that patients with psoriasis are more often absent from work and are less efficient employees, which obviously exacerbate their stress and therefore the disease [13, 14].

Considering often inconsistent information coming from medical publications regarding different issues related to the quality of patients with psoriasis, physical and mental health combined together, we decided to investigate some aspects of such patients’ everyday being and search for correlations between psoriasis severity and laboratory data.

Methods

A set of multiple surveys, both validated and original (own authorship), regarding different matters of patients’ life, was conducted in the group of 56 patients with the diagnosis of plaque psoriasis, hospitalized at the Department of Dermatology. Psoriasis severity was assessed by the same dermatologists using the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI). Applied exclusion criteria were malignancies, renal diseases, infectious diseases, anemia, pregnancy, depression, and anxiety disorders. Every volunteer signed an informed written consent before the enrollment and the study was approved by the local bioethics committee (No. R-I-002/315/2018). The study was conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Patients’ life quality was assessed using the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) [15] and WHO Quality of Life Questionnaire–short version (WHOQoL-BREF) [16]. The minimum score in DLQI is 0 and the maximum is 30 points. The higher the score in DLQI, the lower the dermatological life quality. Moreover, points have been transferred into a descriptive scale of life quality. We also analyzed three questions separately, assigning from 1 to 4 points for each answer; the higher the score, the bigger the problem. This applies to the analysis of time spent on skin care, impairment in undertaking physical activity, and embarrassment about one’s own appearance. In the WHOQoL-BREF, which consists of 26 questions, there are four domains distinguished: somatic, psychological, environmental, and social. The life quality is assessed for each domain separately by transforming the score into a scale ranging from 0 to 100, according to which the higher the score, the better the life quality. We separately evaluated subjective satisfaction with own health, healthcare, sex life, as well as acceptance of physical appearance. These parameters were assessed between 1 to 5 points, where 5 meant the best satisfaction with healthcare, sex life, and acceptance of appearance.

The ability to take physical activity and sports habits were analyzed using the short version of International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) [17]. On the basis of this tool, physical activity (walking, moderate or vigorous), performed during the past 7 days, was assessed in MET-min (metabolic equivalent) energy expenditure. Total weekly activities were expressed in MET-min/week expenditure by multiplying the ratio specific for an activity, number of days it was performed, and the number of minutes per day the activity lasted. In general, the higher the MET-min score, the more intensive the activities performed, although other variables must be taken into consideration. According to the principles of this survey, only activities lasting longer than 10 min were taken into account and the frequency of performing the activity is important because it puts every individual in a particular group of intensity in a descriptive IPAQ scale. Therefore, patients were subsequently divided into three groups regarding the intensity: low, moderate, and high level of physical activity. The high-level activity group comprised individuals who took any combination of physical activity for 7 days of total more than 3000 MET-min/week or people who took a vigorous physical activity for 3 days of total at least 1500 MET-min/week. The moderate-level activity group comprised individuals who reported at least 3 days of vigorous activity for at least 20 min per day or people who performed at least 5 days of moderate activity or walking for at least 30 min per day or who took at least 5 days of any combination of activity of total more than 600 MET-min/week. Individuals who did not meet the criteria of the aforementioned activity intensities were put into the low-level physical activity group.

Stress severity in patients and their nutritional habits were assessed in two original, self-invented surveys. Stress questionnaire contained three questions regarding potentially stressful experiences in everyday life. One question was used to evaluate stress severity on a scale from 1 to 5, where 1 means the lowest stress, and 5 means the most severe.

All obtained data were compared to a sex- and age-matched control group of 36 volunteers without dermatological disorders.

The normality of gathered data was tested using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Data with a normal distribution were analyzed using the Student t test, non-Gaussian data were subjected to Mann–Whitney non-parametric analysis, whereas binary data underwent chi-square testing. The correlations between analyzed variables were determined using Spearman’s rank correlation. The data is presented as mean ± SEM, unless otherwise stated. Two-tailed p < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant. Computations were performed using GraphPad 7 Prism Software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). The power of the analysis was estimated using StatMate2 Software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). All the heatmap graphs were drawn using GraphPad 7 Prism software.

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Medical University of Bialystok, Poland (R-I-002/315/2018, 28/06/2018). Every volunteer signed an informed written consent before the enrollment.

Results

A total of 56 patients were enrolled into the study. Baseline characteristics of patients and controls are presented in Table 1. The patients’ group consisted of 31 men and 25 women, mean age was 49.03 ± 2.2 years old. Mean BMI was 27.33 ± 0.83 which reflects overweight, although comparing to controls, the difference is not significant. Mean PASI before treatment was 14.12 ± 1.2, and after the treatment it decreased to 8.53 ± 0.86.

Table 1.

Baseline parameters in patients with psoriasis and controls

| Parameter | Controls (n = 36) | Patients with psoriasis (n = 56) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex (F/M) | 19/17 | 25/31 |

| BMI | 25.34 ± 0.58 | 27.33 ± 0.83 |

| Age | 51.40 ± 2.8 | 49.03 ± 2.2 |

| ALT | – | 24.91 ± 2.75 |

| AST | – | 26.4 ± 2.19 |

| Total cholesterol | – | 155 ± 5.1 |

| HDL | – | 42.43 ± 2.99 |

| LDL | – | 95.67 ± 11.37 |

| TG | – | 132.6 ± 8.42 |

| Uric acid | – | 5.86 ± 0.37 |

| Glucose | – | 92.64 ± 3.87 |

| CRP | – | 10.25 ± 2.43 |

PASI Psoriasis Area and Severity Index, TGs triglycerides, HDL high-density lipoproteins, LDL low-density lipoproteins, CRP C-reactive protein, ALT alanine transaminase, AST asparagine transaminase

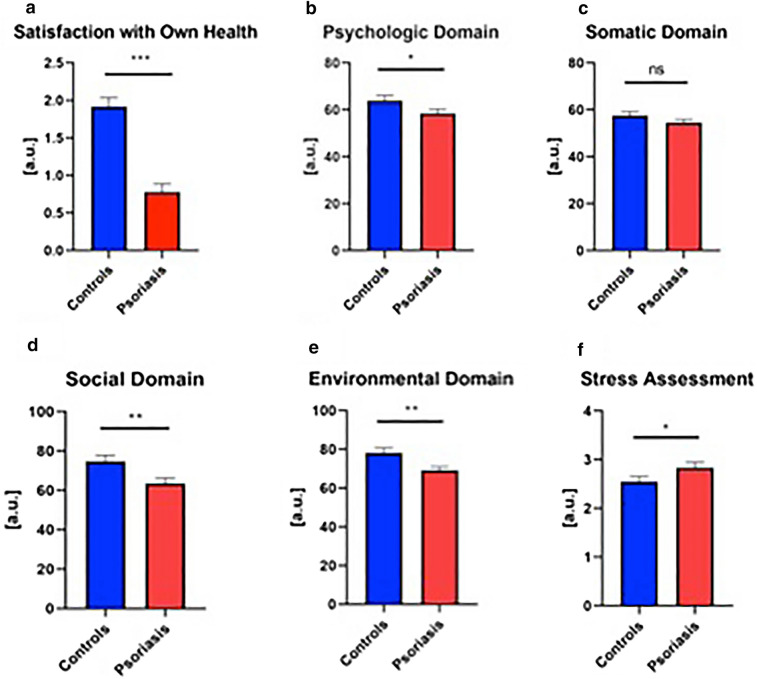

Dermatology Life Quality Assessment

The median score in the numerical scale was 10.5 points (1–28) out of a maximum 30, which indicates an effect just between “moderate” and “very large” of psoriasis on patients’ quality of life. Twelve patients (21.4%) reported an extremely large effect on their life quality and 17 patients (30.35%) a very large effect. There was no correlation between PASI and DLQI (NS). DLQI was on the other hand negatively correlated with the life quality in psychological, environmental, and social domains (R = − 0.4, p < 0.01; R = − 0.311, p = 0.0732; R = − 0.292, p < 0.05, respectively). The time spent on skin care was negatively correlated with life quality in the psychological domain (R = − 0.52, p < 0.0001) and positively with embarrassment about skin condition, difficulties in taking physical activity, as well as stress severity (R = 0.54, p < 0.01; R = 0.6, p < 0.0001; R = 0.41, p < 0.01, respectively) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Correlations between WHO domains, inability to take physical activity, stress severity, embarrassment with physical appearance, and time spent on skin care

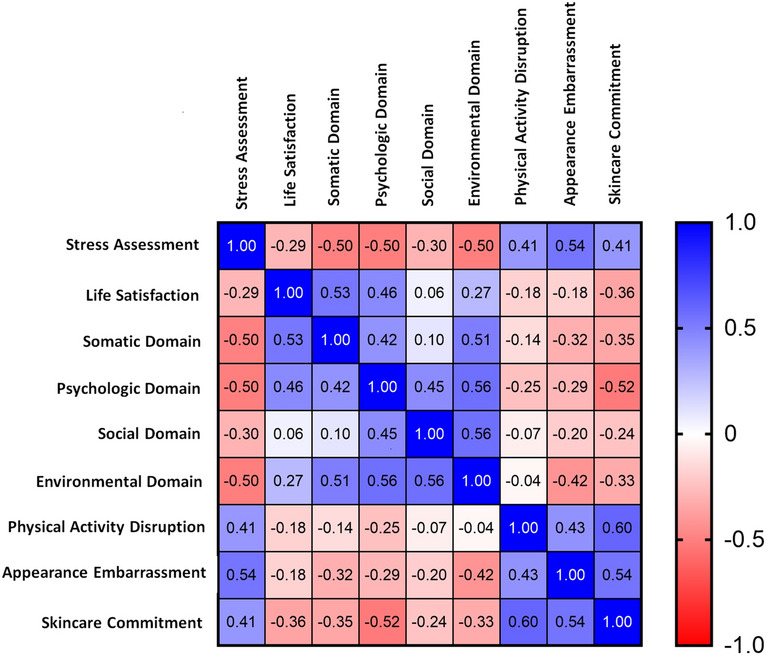

General Life Quality Assessment

General life quality assessment was performed using WHOQoL-BREF and the results are presented in Fig. 2a–f. Quality of life was evaluated in four domains and the maximum score in each domain was 100 points. The mean score was 63.61 ± 2.62, 69.28 ± 1.74, 58.46 ± 1.75, and 54.62 ± 1.33 for patients in the social, environmental, psychological, and somatic domain, respectively; and for the controls it was 74.82 ± 2.99, 78.28 ± 2.49, 63.97 ± 2.15, and 54.62 ± 1.33, respectively. The results for three of four domains were statistically significantly different from the controls—the patients reported lower satisfaction in social, psychological, and environmental domains (p < 0.001, p = 0.504, p = 0.0029). Nearly half of all patients (42.85%) reported dissatisfaction with their health: 8.9% (5/56) reported being very unsatisfied and 33.9% (19/56) unsatisfied. The mean result of satisfaction with patients’ own health was 2.82 ± 0.11 out of 5 maximum, and 3.875 ± 0.12 for the controls, which means statistically significantly poorer satisfaction with health for patients with psoriasis than controls (p < 0.0001). Satisfaction with own health was positively correlated with satisfaction in somatic and psychological domains (R = 0.48, p < 0.0001; R = 0.46, p < 0.01, respectively). Only 12.5% of patients reported being unsatisfied or very unsatisfied with the healthcare. The mean result of satisfaction with healthcare for patients was 3.55 ± 0.97 out of 5 maximum. There was no meaningful correlations between PASI and WHO domains (NS).

Fig. 2.

General quality of life and its domains according to WHO-QoL: a satisfaction with own health , b psychological domain, c somatic domain, d social domain, e environmental domain, and f stress assessment including comparison between patients and controls. Asterisks mean the existence of statistically significant difference between values in the patients’ and control group with *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.0001

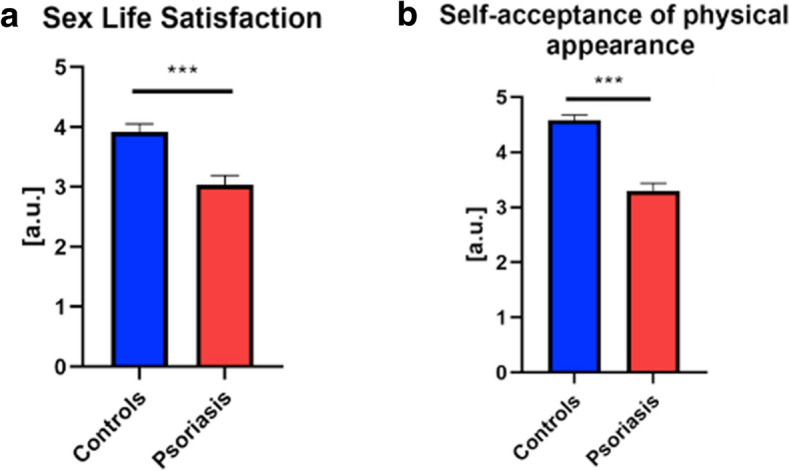

Seventeen individuals (30.35%) reported unsatisfying sex life (unsatisfied/very unsatisfied) with the mean score of 3.03 ± 0.16 points out of a maximum 5, comparing to 5.6% of unsatisfied volunteers and the mean score of 3.91 ± 0.13 out of a maximum 5 points, which was statistically significant (p < 0.0001) (Fig. 3a). Only 35.7% of all patients fully accepted their physical appearance (they were satisfied or very satisfied), with the mean score of 3.23 ± 0.137 points, comparing to healthy controls, in which 97.2% accepted their look with the mean of 4.58 ± 0.092 out of a maximum 5 points, which indicates significantly worse acceptance in patients (p < 0.0001) (Fig. 3b). Satisfaction with sex life was negatively correlated with PASI (R = − 0.36, p < 0.01), but PASI was not correlated with the acceptance of physical appearance (NS). There was a positive correlation between the satisfaction of the patients with their sex life and psychological, social, and environmental domains in the WHO questionnaire (R = 0.4, p < 0.01; R = 0.7, p < 0.0001; R = 0.5, p < 0.0001, respectively) and between the acceptance of physical appearance and life satisfaction, psychological, somatic, and environmental domains (R = 0.394, p < 0.01; R = 0.672, p < 0.0001; R = 0.4, p < 0.01; R = 0.38, p < 0.01, respectively) (Table 2). There was a negative correlation between satisfaction with sex life and age (R = − 0.421, p < 0.01).

Fig. 3.

Satisfaction with sex life (a) and physical appearance (b) in patients and controls. ***Statistically significant difference between values in the patients’ and control group with p < 0.0001

Table 2.

Correlations between satisfaction with sex life and acceptance of physical appearance and WHO life quality domains

| Parameter | Satisfaction with sex life (R/p) | Acceptance of physical appearance (R/p) |

|---|---|---|

| Satisfaction with own health | 0.139/NS | 0.394/0.0029 |

| Somatic domain | 0.245/0.0718 | 0.400/0.0024 |

| Psychologic domain | 0.401/0.0024 | 0.672/< 0.0001 |

| Social domain | 0.714/< 0.0001 | 0.223/NS |

| Environmental domain | 0.503/< 0.0001 | 0.380/0.0042 |

| Satisfaction with sex life | X | 0.231/0.076 |

| Acceptance of physical appearance | 0.231/0.076 | X |

Italic font means the existence of a trend. Bold font means statistical significance

NS non-significant, R Spearman’s rank

Stress Assessment

The results of stress assessment are presented in Fig. 1f. The mean stress score in the patients’ group was 2.84 ± 0.11 out of a maximum of 5 and it was significantly higher than in controls (2.55 ± 0.11, p < 0.05). There was no correlation between PASI and stress severity (NS). A reported stressful event preceded the eruption of psoriatic lesions in 23 patients (41%). Stress severity was positively correlated with the time spent on skin care (R = 0.54, p < 0.0001), embarrassment about skin condition, and disruption in taking physical activity (both R = 0.41, p < 0.01). Obviously, stress severity was negatively correlated with the quality of life in WHO somatic, psychological, and environmental domains (all R = − 0.5, p < 0.01).

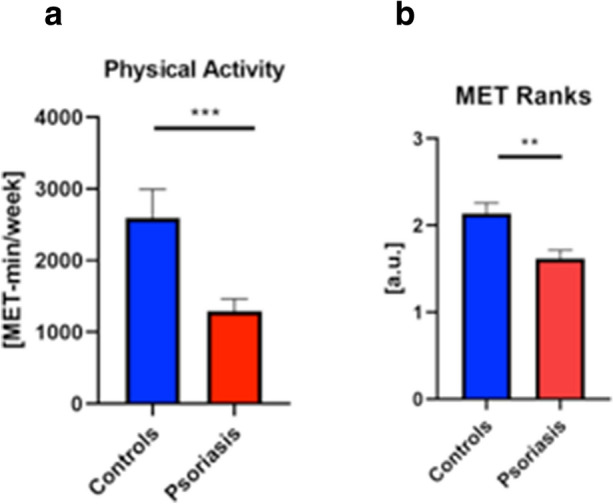

Physical Activity Assessment

Physical activity analysis is presented in Fig. 4. Every participant was evaluated in the terms of intensity of activity and expressed in MET-min/week. The majority of patients with psoriasis—27/56 (48.2%) performed low-level physical activity according to the descriptive scale, 18/56 (32.14%) performed moderate-level activity, and 11 (19.64%) performed high-level activity. Among the controls the majority—17 persons (47.22%)—took moderate physical activity, 12 (33.33%) high, and only 7 persons (19.44%) low. The median activity expressed in MET-min/week in the patients’ group was 693 (3–4158); in the subgroup of patients with low-level activity it was 198 (3–2772), in the subgroup of moderate-level activity it was 1990 (495–2829), and in the subgroup of high-level activity it was 3883 (1653–4158). For the controls it was 2106 (231–10,542) in total, and in each subgroup it was 292 (231–462), 1773 (462–2470), and 4812 (3342–10,542), respectively. There was a statistically significant difference in the physical activity intensity expressed in MET-min/week and on the descriptive scale between the patients and controls (p < 0.01, p < 0.0001, respectively). There was neither correlation between the physical activity level and PASI (NS) nor with quality of life in any of the WHO domains (except for environmental R = 0.284, p < 0.05) or the sex life quality (NS).

Fig. 4.

Physical activity assessment with comparison between patients and controls. Asterisks mean the existence of statistically significant difference between values in the patients’ and control group with **p < 0.01/***0.0001

Discussion

Food, water, shelter, sleep, and rest are the physiological human needs that are presented in Maslow’s hierarchy of needs as the most fundamental which have to be satisfied [18]. It highlights the essence of this research and the need to consider not only treatment in the psoriasis management but also other issues which affect patients’ well-being.

In our study patients with psoriasis had significantly lower scores in three out of four WHO domains: psychological, social, and environmental but surprisingly not somatic. A lower score in the environmental domain suggests worse functioning in everyday life and satisfaction with one’s own, broadly defined, surrounding environment, including home, work, and financial situation. A lower score in the psychological domain shows that patients with psoriasis experience less joy and have worse concentration than healthy individuals. Patients also reported lower scores in the social domain of life quality. Clearly, patients with psoriasis suffer from the consequences of an unsatisfactory skin condition, which not only affects their comfort in a negative way but also disturbs relationships with other people. Social withdrawal and stigmatization contribute to a higher risk of depression in patients with psoriasis as well. What is interesting is that the severity of psoriasis is not directly related to patients’ mood [19]. In this paper patients with psoriasis have significantly decreased sex life quality compared to persons free from dermatological diseases, which correlates with psoriasis severity in PASI. This issue seems difficult to investigate thoroughly since people are usually embarrassed to talk about such matters. Nevertheless, other studies confirm our outcomes that psoriasis negatively affects the sexual lives of patients with psoriasis and their partners, and the rate of sexual dysfunction is significantly higher in this group compared to healthy controls [20, 21]. Although genital psoriasis is observed in about 60% of cases, it seems not to be the only significant factor for sexual dysfunction [22]. As for the reason for such disturbances, studies show it is mainly psychogenic [20]. Current American Academy Dermatology–National Psoriasis Foundation (AAD-NPF) recommendations suggest talking about this delicate issue with patients with psoriasis [22]. In our research satisfaction with sex life was positively correlated with psychological and social life, which suggests the importance of such matters in mental health maintenance. People with psoriasis are often ashamed of their appearance and are badly perceived in social matters, which we were able to confirm as well. Acceptance of physical appearance was also positively correlated with the general satisfaction with life, psychological and somatic domains, which means it is an important issue for patients with psoriasis.

The median DLQI in the studied patients was 10.5 points which reflects just about a very large effect on patients’ life quality according to the descriptive scale of this questionnaire. Moreover, as higher DLQI was significantly associated with worse scores in psychological, environmental, and social WHO domains, it suggests that skin condition is an essential factor influencing general life quality.

Although there are various therapeutic options, psoriasis is difficult to treat, often resistant to applied agents, and recurrent. These features reflect why the mean satisfaction with healthcare of patients with psoriasis was 3.55 ± 0.97 out of a maximum 5 points, which is rather disappointing. It could be associated with worse availability of biologic drugs in our country, as well as frequently observed fear of introduction of systemic agents in patients with psoriasis. An important issue in dermatological diseases, especially psoriasis, is skin care. Not only does it require one to visit doctors often but it also involves an everyday skin care routine, which also takes a lot of time and effort. Our research confirmed this discomfort since the more time is spent on skin care, the worse the life quality in the psychological domain is, the greater the embarrassment about the skin condition, difficulties in taking physical activity, and stress severity are.

An unesthetic appearance, subjective symptoms such as pruritus or pain, time-consuming treatment, skin care, and doctors’ appointments favor stress in patients with psoriasis. In our original survey patients had significantly higher stress severity compared to controls. As in the majority of similar studies, there was no correlation between PASI and stress severity [23]. Eruptions of psoriatic lesions are well known to appear after stressful events and in our study such a situation occurred in 41% of patients [8]. Currently there are no guidelines particularly considering stress management in patients with psoriasis. AAD-NPF recommendations mention psychological care focusing on depression and anxiety in patients with psoriasis but no specific stress-detection procedures, and our local Polish recommendations do not [22]. Therefore, further investigation of this problem in patients with psoriasis and finding an optimal diagnostic tool for identifying patients who cope with a lot of stress would be reasonable. Stress is tightly associated with stigmatization and deterioration in patients’ quality of life, especially in the matter of social relationships, work, sex life, and everyday activities [23]. Our research shared this point of view, since it revealed the negative correlation between stress severity and quality of life in three WHO domains, which indicates the big influence of stress on patients’ well-being.

Almost half of patients with psoriasis reported only low-level physical activity and the smallest group of them (19.64%) reported high-level activity. Comparing to the controls, the majority of healthy persons performed moderate-level physical activity. This clearly shows that patients with psoriasis have a decreased ability to take physical exercise and choose low-intensity activity mostly, comparing to controls who significantly exercise more intensely. Moreover, patients with psoriasis had significantly lower physical activity intensity compared to controls both on the descriptive scale and in MET-min/week. This dermatosis itself leads to either physical impairment resulting in inability to do exercise or it decreases the life quality and patients’ mood so severely that they are not keen on taking such activities [24]. All of the aforementioned lead to lower physical activity, worse general condition of patients, and favor putting on weight. Excessive body weight has multiple adverse effects. It does not simply result in greater risk of metabolic syndrome and all associated diseases [5]. Extensive research confirms the negative influence of excessive body weight on the course and treatment of psoriasis. Regular physical activity, and therefore losing weight, results in improvement of skin lesions [25]. This may be associated with the anti-inflammatory impact of physical exercise and reduction of anti-inflammatory cytokines, involved also in psoriasis pathogenesis [24]. Some research revealed also significant reduction of DLQI after a course of physical activity (along with diet and stress reduction) [7]. Regular physical activity may even reduce the risk of psoriasis development [24, 26]. Accordingly, contemporary guidelines advise patients with psoriasis to exercise regularly; however, AAD-NPF guidelines for psoriasis management do not specify the quantity and frequency [22]. Psoriasis is known to be associated with different cardiovascular diseases and physical activity is one of the easiest ways of preventing such disorders. Therefore, it seems that there is a vicious circle between psoriasis, its comorbidities, and physical activity because psoriasis favors CMDs; these should be prevented by taking physical exercise which subsequently cannot be performed because of skin condition or bad attitude or psoriatic arthritis.

Dermatological patients, especially those with chronic diseases such as psoriasis, are a specific group of patients. Their disease is often easily seen by other people which implicates stigmatization and therefore lower life quality. Internal diseases, on the other hand, involve body organs and, although they are often severe in consequence, it is not frequently obvious for others to find out that an encountered individual is ill. Besides mental health impairment, psoriasis leads to physical deterioration: unpleasant subjective symptoms, multiple systemic comorbidities and their serious consequences, inability to take physical activity, and inappropriate diet or addictions.

As for limitations of our study, it was a single-center research program based only on hospitalized patients, with a relatively small number of participants included. Moreover, we encountered plenty of obstacles regarding physical activity assessment, considering the nature of IPAQ, and the direct comparison between patients and controls was difficult to perform. Also sexual activity and addictions could not be fully reliably evaluated considering patients were usually not willing to talk about such matters and stress was assessed using our own questionnaire instead of a validated instrument.

Conclusions

This study confirmed that patients with psoriasis have decreased satisfaction with their own health, social, psychological, and environmental issues as well sex life and worse acceptance of physical appearance than individuals free from this dermatosis. Patients with psoriasis also take less intensive physical activity than people without dermatological disorders, which predisposes to obesity, whose risk is already increased by the dermatosis itself. The study highlights the perception of psoriasis as not only affecting skin but also having a multifactorial impact on psychological and internal condition. Described coexisting abnormal lifestyle habits could be easily and reliably evaluated with validated questionnaires, which can be handed over to patients for efficient completion in order to raise their awareness of comorbidities and mobilize them to modify incorrect lifestyle habits. We believe doctors should not only focus on treating skin but also consider screening for other disorders and introduce a holistic approach to every patient because, all in all, the improvement of patients’ life quality is what matters most.

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants of the study.

Funding

This report required no funding during preparation. Medical University of Bialystok, Poland supported the study and the journal’s rapid service fee.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Author Contributions

J.N.: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Project administration, Resources, Formal analysis, Writing-original draft, Writing—review & editing. A.B.: Conceptualization, Data curation, Project administration, Writing—original draft preparation, Writing-review & editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition. M.L.: Investigation; P.G.: Investigation; T.W.K.: Formal analysis; Software; Visualization; Writing–review and editing. I.F.: Project administration; Supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Disclosures

Julia Nowowiejska, Anna Baran, Paulina Grabowska, Marta Lewoc, Tomasz W. Kaminski and Iwona Flisiak have nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Medical University of Bialystok, Poland (R-I-002/315/2018, 28/06/2018). Every volunteer signed an informed written consent before the enrollment.

Data Availability

Data is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Contributor Information

Julia Nowowiejska, Email: julia.nowowiejska@umb.edu.pl.

Anna Baran, Email: anna.baran@umb.edu.pl.

Paulina Grabowska, Email: paulina.dluzniewska29@gmail.com.

Marta Lewoc, Email: lewocmarta@gmail.com.

Tomasz W. Kaminski, Email: kamins1@pitt.edu

Iwona Flisiak, Email: iwona.flisiak@umb.edu.pl.

References

- 1.Gupta MA, Simpson FC, Gupta AK. Psoriasis and sleep disorders: a systematic review. Sleep Med Rev. 2016;29:63–75. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2015.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chabros P, Pietrzak A, Gągała J, Kandzierski G, Krasowska D. Psoriatic arthritis—classification, diagnostic and clinical aspects. Dermatol Rev. 2020;107:32–43. doi: 10.5114/dr.2020.93969. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nowowiejska J, Baran A, Krahel J, Flisiak I. Acrodermatitis continua Hallopeau. Dermatol Rev. 2021;108:52–58. doi: 10.5114/dr.2021.105894. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ryan C, Kirby B. Psoriasis is a systemic disease with multiple cardiovascular and metabolic comorbidities. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:41–55. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2014.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nowowiejska J, Baran A, Flisiak I. Psoriasis and cardiometabolic disorders. Dermatol Rev. 2020;107:508–520. doi: 10.5114/dr.2020.103887. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nowowiejska J, Baran A, Flisiak I. Aberrations in lipid expression and metabolism in psoriasis. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:6561. doi: 10.3390/ijms22126561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilson PB, Bohjanen KA, Ingraham SJ, Leon AS. Psoriasis and physical activity: a review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:1345–1353. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2012.04494.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martínez-Ortega JM, Nogueras P, Muñoz-Negro JE, Gutiérrez-Rojas L, González-Domenech P, Gurpegui M. Quality of life, anxiety and depressive symptoms in patients with psoriasis: a case-control study. J Psychosom Res. 2019;124:109780. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2019.109780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kurd SK, Troxel AB, Crits-Christoph P, Gelfand JM. The risk of depression, anxiety, and suicidality in patients with psoriasis: a population-based cohort study. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:891–895. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2010.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rapp SR, Feldman SR, Exum ML, Fleischer AB, Jr, Reboussin DM. Psoriasis causes as much disability as other major medical diseases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:401–407. doi: 10.1016/S0190-9622(99)70112-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nowowiejska J, Baran A, Lewoc M, Grabowska P, Kaminski TW, Flisiak I. The assessment of risk and predictors of sleep disorders in patients with psoriasis—a questionnaire-based cross-sectional analysis. J Clin Med. 2021;10:664. doi: 10.3390/jcm10040664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nowowiejska J, Baran A, Flisiak I. Sleep disorders in psoriasis. Dermatol Rev. 2020;107:272–280. doi: 10.5114/dr.2020.97780. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mansouri P, Valirad F, Attarchi M, et al. The relationship between disease, work and sickness absence among psoriasis patients. Iran J Public Health. 2015;44(11):1506–1513. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nowowiejska J, Baran A, Flisiak I. Mutual relationship between sleep disorders, quality of life and psychosocial aspects in patients with psoriasis. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:674460. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.674460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DLQI. http://luszczycowezapaleniestawow.pl/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/ocena_zaawansowania_uszczycy_-_dlqi.pdf. Accessed 10 June 2018.

- 16.WHO QoL-BREF questionnaire. https://www.who.int/tools/whoqol/whoqol-bref/docs/default-source/publishing-policies/whoqol-bref/polish-whoqol-bref. Accessed 10 June 2018.

- 17.IPAQ short version. https://www.academia.edu/19229070/Międzynarodowy_Kwestionariusz_Aktywności_Fizycznej_IPAQ_wersja_polska. Accessed 10 June 2018.

- 18.Hale AJ, Ricotta DN, Freed J, Smith CC, Huang GC. Adapting Maslow’s hierarchy of needs as a framework for resident wellness. Teach Learn Med. 2018;31:109–118. doi: 10.1080/10401334.2018.1456928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Łakuta P, Marcinkiewicz K, Bergler-Czop B, Brzezińska-Wcisło L. How does stigma affect people with psoriasis? Adv Dermatol Alergol. 2017;34:36–41. doi: 10.5114/pdia.2016.62286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alariny AF, Farid CI, Elweshahi HM, Abbood SS. Psychological and sexual consequences of psoriasis vulgaris on patients and their partners. J Sex Med. 2019;16:1900–1911. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2019.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hirotsu C, Rydlewski M, Araujo MS, Tufik S, Andersen ML. Sleep loss and cytokines levels in an experimental model of psoriasis. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:51183. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elmets CA, Leonardi CL, Davis DMR, et al. Joint AAD-NPF guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with awareness and attention to comorbidities. JAAD. 2019;80:1073–1113. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.11.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rousset L, Halioua B. Stress and psoriasis. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:1165–1172. doi: 10.1111/ijd.14032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Torres T, Alexandre JM, Mendonça D, Vasconcelos C, Silva BM, Selores M. Levels of physical activity in patients with severe psoriasis: a cross-sectional questionnaire study. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2014;15:129–135. doi: 10.1007/s40257-014-0061-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Naldi L, Conti A, Cazzaniga S, Patrizi A, Pazzaglia M, Lanzoni A. Diet and physical exercise in psoriasis: a randomized controlled trial. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170:634–642. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Frankel HC, Han J, Li T, et al. The association between physical activity and the risk of incident psoriasis. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:918–924. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2012.943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.