Abstract

Introduction

Treatments other than topical and systemic antibiotics are needed to restore the dysbiosis correlated with acne onset and evolution. In this view, probiotics and botanical extracts could represent a valid adjunctive therapeutic approach. The purpose of this study was to test the efficacy of a dietary supplement containing probiotics (Bifidobacterium breve BR03 DSM 16604, Lacticaseibacillus casei LC03 DSM 27537, and Ligilactobacillus salivarius LS03 DSM 22776) and botanical extract (lupeol from Solanum melongena L. and Echinacea extract) in subjects with mild to moderate acne over an 8-week study period.

Methods

Monocentric, randomized, double-blind, four-arm, placebo-controlled clinical study involving 114 subjects.

Results

A significant (p < 0.05) effect on the number of superficial inflammatory lesions was reported over the study period in the subjects taking the study agent (group II) (−56.67%), the botanical extracts (group III) (−40.00%), and the probiotics (group IV) (−38.89%) versus placebo (−10.00%). A significant (p < 0.05) decrease in mean desquamation score, sebum secretion rate, and porphyrin mean count versus baseline was also reported, and the effect was most evident for group II. The analysis of log relative abundance after 4 and 8 weeks of treatment compared with baseline showed a significant (p < 0.01) decrease in Cutibacterium acnes and S. aureus, along with a contextually and significant (p < 0.05) increase in Staphylococcus epidermidis, especially in group II. No significant changes were reported for group I.

Conclusion

The results from this study suggest that the administration of the dietary supplement under study was effective, safe, and well tolerated in subjects with mild to moderate acne and could represent a promising optional complement for the treatment of inflammatory acne as well as for control of acne-prone skin.

Keywords: Acne, Dietary supplement, Probiotic, Ligilactobacillus salivarius LS03, Lupeol, Echinacea

Key Summary Points

| Why carry out this study? |

| Acne vulgaris (acne) is chronic inflammatory dermatosis with multifactorial etiology, affecting mainly adolescents. |

| Common therapies such as antibiotic and retinoids, both topical and oral, have many limitations. In this view, treatments other than topical and systemic antibiotics are needed to restore the dysbiosis correlated with acne onset and evolution. |

| What was learned from the study? |

| The results from this study suggest that the administration of a dietary supplement containing B. breve BR03, L. casei LC03, L. salivarius LS03, lupeol and Echinacea extract in subjects with mild to moderate facial acne is safe, well tolerated, and able to reduce total facial lesion count (GAGS score) versus placebo and probiotics and botanical extracts alone after 8 weeks of administration. |

Introduction

Acne vulgaris (acne) is chronic inflammatory dermatosis with multifactorial etiology, affecting mainly adolescents [1], although it is also reported in the adult population [2]. It is ranked among the top ten diseases worldwide [3] with almost half of all women aged 21–30 years suffering this condition [4].

Acne is an inflammatory process localized to the pilosebaceous units of the face, chest, arms, and back [5]. The alteration of keratinization within the pilosebaceous unit, resulting in the formation of comedones, increased production of sebum, proliferation of Cutibacterium acnes, and perifollicular inflammation has been hypothesized in the pathophysiology of acne [6].

The inflammation covers the entire life cycle of the acne lesion, from onset to resolution, including the formation of closed comedones, inflammatory lesions, post-inflammatory erythema (PIE) and hyperpigmentation, and scarring [7]. There are many common treatments for acne lesions depending on the severity of acne according to the European evidence-based (S3) guidelines for the treatment of acne [8]. Systemic therapy is the first-line choice that can be eventually combined with topical therapy [9]. More specifically, oral antibiotic therapy is recommended for the management of moderate and severe inflammatory acne resistant to topical treatments, but the use of systemic antibiotics should be limited to the shortest possible time, generally 3 months. Commonly used topical therapies include benzoyl peroxide, salicylic acid, retinoids, azelaic acid, antibiotics, and their combinations [8, 10].

Antibiotic and retinoid therapies, both topical and oral, have many limitations: cheilitis; xerosis of the hands and face, including the nasal mucosa; skin fragility; and sensitivity to UV radiation [8]. For instance, isotretinoin and lymecycline treatments have been reported to modify the skin microbiota in acne [11]. Therefore, the use of antibiotics has been linked to modification in both the gut and skin microbiota [12].

A new understanding of the pathophysiology of acne leads to a paradigm shift: Cutibacterium acnes is not the only microorganism involved in acne development; other bacteria, mainly Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermis, are also implicated [13].

In this view, treatments other than topical and systemic antibiotics are needed to restore the dysbiosis correlated with acne onset and evolution.

The usefulness of probiotics in acne has been reported in many in vitro and in vivo studies [14]. Probiotics have a two-way mechanism in managing acne; firstly, they rebalance the microbiota by preventing the growth of opportunistic bacteria [15]. In some cases, their inhibitory activity is mediated by antibacterial proteins and bacteriocins [14]. Probiotics were also found to inhibit cytokine interleukin-8 (IL-8) in epithelial cells and to reduce inflammation by controlling the expression of inflammatory cytokines and inhibiting pathogenic CD8 T cells [16, 17]. Among cytokines involved in acne, IL-8 has been reported as the leading proinflammatory mediator in acne.

Recently, Deidda and colleagues reported the bacteriocin-dependent activity and a targeted anti-IL-8 property of the probiotic strain L. salivarius LS03 DSM 22776 [18].

Recently, there has also been growing interest in the use of botanical extract for the management of many inflammatory skin conditions, including acne vulgaris [19, 20]. A meta-analysis of Soleymani et al. [21] investigated the mechanisms of actions of promising plant-derived secondary metabolites in the management of acne vulgaris. One plant metabolite that has been reported to target the main pathogenic features of acne is lupeol, a pentacyclic triterpene, from Solanum melongena L. [22, 23].

Another effective and safe alternative for the treatment of acne is Echinacea, a botanical extract with a long history of use in inflammatory disease due to its recognized anti-inflammatory activity [24].

The purpose of this study was to test the probiotics and botanical extracts-based supplement in a randomized, double-blind, four-arm, placebo-controlled clinical study to assess the effectiveness of the natural active substances in subjects with mild to moderate acne over an 8-week study period.

Methods

Subjects

In total, 112 adult subjects (average age 23 ± 7.15 years) of both sexes with mild to moderate acne were recruited at RS Dermatologic Clinic, Milan, Italy. The main exclusion criteria included current use of any prescription treatment (oral or topical) for acne (2 months washout allowed), pregnancy and lactation, known allergy or hypersensitivity to any of the constituents of the study product, and participation in a similar study in the last 3 months.

Compliance with Ethics

All patients were evaluated and enrolled in the study after signing informed consent. Parental consent was obtained in the case of children. This study was approved by the Independent Ethical Committee for Clinical not Pharmacological Investigation of Genoa, Italy and was in accordance with the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki of 1964.

Study Design

The study was structured in the form of a randomized double-blinded, placebo, and active-controlled, parallel groups (four arms) study. The study was performed between September 2018 and January 2019. The product under study was a probiotics-based dietary supplement herein referred to as study agent (Primak Integratore, Giuliani S.p.A., Milan, Italy). The supplement was in the form of a DUOCAM sachet containing two different blends: probiotics (Bifidobacterium breve BR03 DSM 16604, Lacticaseibacillus casei LC03 DSM 27537, and Ligilactobacillus salivarius LS03 DSM 22776 and botanical extract (lupeol from Solanum melongena L. and Echinacea extract), respectively.

Specifically, the probiotic chamber included ≥ 0.5 × 109 live cells of B. breve BR03 (DSM 16604), ≥ 0.5 × 109 live cells of L. casei LC03 (DSM 27537), and ≥ 1.0 × 109 live cells of L. salivarius LS03 (DSM 22776) (combined dose of ≥ 2 × 109 live cells), with maltodextrin used as a bulking agent to yield a final weight of 1.5 g. The probiotic sachets were analyzed by Biolab Research S.r.l., Novara, Italy, via flow cytometry [ISO 19344:2015 IDF 232:2015, ≥ 2 × 109 active fluorescent units (AFU)] and plate count method (Biolab Research Method 014-06, ≥ 2 × 109 CFU) to confirm target cell count.

Product stability was monitored to ensure minimum cell counts were maintained (data not shown).

Inserire Composizione Botanicals

Subjects were enrolled after verification of inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 1) and randomized to one of the four treatment groups: (I) placebo, (II) study agent, (III) botanical extracts, and (IV) probiotics. The ingredients in the placebo were inert.

Table 1.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| Male and female > 16 years old | Known sensitivity to any compound of the investigational product |

| Suffering from mild to moderate acne | Pregnant |

| The last treatment was at least 2 months before | Serious intercurrent infection or another active disease up to 3 months before study entry |

| Subjects not responsive to other previous treatments, either systemic and topical or phototherapy | History of concurrent malignancy |

| Subjects accepting to follow the instruction received by the investigator and disposable and able to return to the study center at the established times | Significant psychosocial or psychiatric disorders that may impair the subject’s ability to meet the study requirements |

| Subjects accepting to not receive any drugs/cosmetics treatment able to interfere with the study results | Significant concurrent medical disorders that may impair the subject’s ability to participate over the whole 1 year of the study |

| No participation in a similar study currently or during the previous 6 months | Any other medical condition that in the Investigator’s opinion would prevent the subject from participating in the study |

| Subjects for which the informed consent form has been signed |

Subjects were instructed to take the supplements once a day after breakfast for 8 weeks. Subjects were screened at baseline (T0), after 4 weeks of treatment (T1), and at the end of treatment (T2).

Efficacy Endpoints

Efficacy endpoints were evaluated at each post-baseline visit and expressed as the percent change from baseline in facial comedones, papules, pustules, and nodules measured using the global acne grading system (GAGS) score that gives a weight to each region (face and back) with a severity score (1–18, mild; 19–30, moderate; 31–38, severe) [25]. Porphyrins were also evaluated at each timepoint by the VISIA system (Canfield Scientific).

Therefore, erythema, desquamation, sebum level, and microbial dysbiosis were measured. Erythema and desquamation were measured according to a four-point qualitative scale: 0 = absent, 1 = mild 2 = moderate, and 3 = severe. Sebum level was measured by a microcamera equipped with 200× Optic system (Microcamera, APR Instruments s.r.l., Milan, Italy). An area of 1.41 × 1.0 mm was displayed. Sebum value was recorded as low, < 100 µm × cm2; medium, 100–200 µm × cm2; or high, > 200 µm × cm2. Microbial dysbiosis was expressed as the relative abundance of bacterial DNA of main bacterial species on the skin: Cutibacterium acnes, Staphylococcus epidermidis, and Staphylococcus aureus [26]. eNAT kit (1 ml eNAT transport and preservation medium and FLOQSwab) (Copan, Brescia, Italy) was used for sampling a 16 cm2 area. Samples were stored at 4 °C until DNA extraction with QIAamp UCP Pathogen Mini Kit (Qiagen, Milan, Italy) according to the manufacturer’s protocol and then amplified with microbial polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay kit (Qiagen, Milan, Italy) with gene-specific primers and TaqMan MGB probe targeting C. acnes, S. epidermidis, and S. aureus 16S rRNA gene.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad statistical software version 13.0 (La Jolla, CA, USA). Change from baseline in the clinical signs of acne, sebum level, hydration, porphyrin production, and microbial dysbiosis were compared between the groups using a t-test (95% confidence interval for the between-group difference).

The sample size was determined as a minimum of 25 evaluable subjects by treatment arm based on the hypothesis that the percentage reduction in clinical signs of acne between treatments would be at least 30% larger than in the placebo arm at the end of the treatment period. Having 25 subjects per group enables the detection of the above effect with a power of > 90% and a significance level of 5%. Therefore, according to sample size calculation, a maximum of 25% of enrolled subjects could drop out during the study period.

Results

In total, 114 of the enrolled subjects (95%) completed the study (28 in group I, 30 in group II, 29 in group III, and 27 in group IV). The mean age was 23.5 ± 8.5 years. Six subjects were withdrawn before visit T1. None of the subjects was terminated due to an adverse event. The demographics of the samples are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Demographic details at baseline

| Group I | Group II | Group III | Group IV | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age mean ± SEM (years) | 23.70 ± 7.59 | 23.53 ± 7.39 | 23.43 ± 6.61 | 23.43 ± 7.01 |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 57 (16) | 53 (16) | 52 (15) | 48 (13) |

| Female | 43 (12) | 47 (14) | 48 (14) | 52 (14) |

| GAGS score ± SEM | 23.57 ± 5.42 | 24.61 ± 8.41 | 22.98 ± 3.32 | 25.81 ± 6.17 |

n number of subjects, SEM standard error of the mean

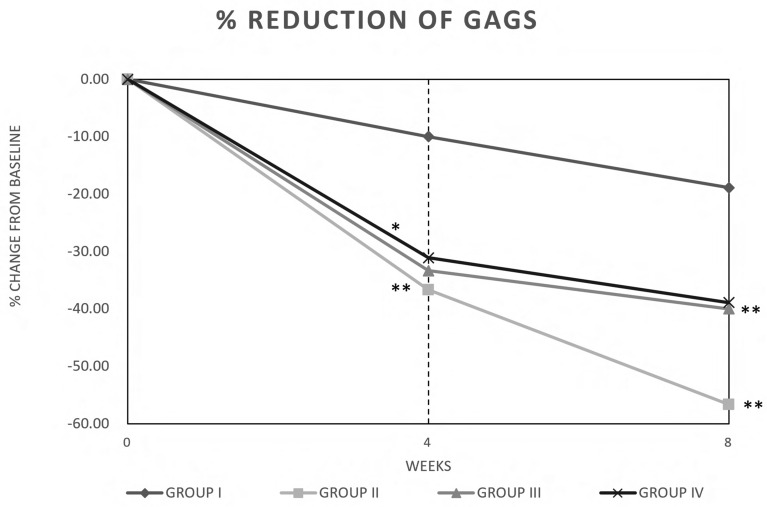

Percent changes from baseline in lesion counts (% of GAGS score reduction) are shown in Fig. 1. At week 4, there was a statistically significant decrease (p < 0.05) in the number of superficial inflammatory lesions over the study period in the subjects taking the study agent (group II), the botanical extracts (group III), and the probiotics (group IV) versus placebo (mean values −36.67%, −33.33%, and −31.11% versus − 10.00% of placebo, respectively) (Fig. 1). This effect increases from T0 to T2 (mean values −56.67%, −40.00%, and −38.89% versus −18.89% of placebo, respectively (p < 0.05). In general, the % of reduction in GAGS score was most evident for group II (study agent).

Fig. 1.

Clinical improvement of acne vulgaris expressed as global acne grading system (GAGS) score. Group (I) placebo, group (II) study agent, group (III) botanical extracts, and group (IV) probiotics. Data are expressed as % of change from baseline

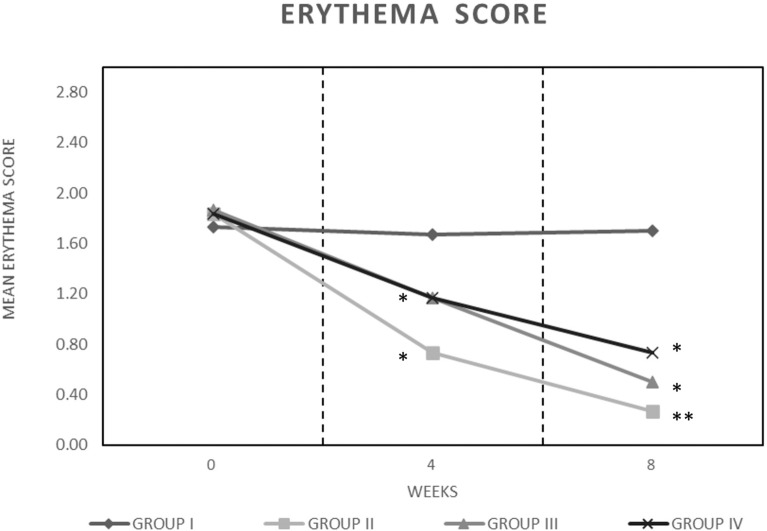

At the beginning of the study, the mean erythema score in the groups was 1.82 ± 0.06, which was subsequently reduced to 0.73 ± 0.69, 1.17 ± 0.83, and 1.30 ± 0.79, respectively, for groups II, III, and IV (Fig. 2) after 4 weeks of treatment, but the effect was not significant. After 8 weeks of treatment, a further and significant (p < 0.05) reduction of erythema score was reported for groups II–IV (0.27 ± 0.45, 0.50 ± 0.63, and 0.73 ± 0.74, respectively) (Fig. 2). Group II showed the highest reduction (85.24% reduction versus baseline). No reduction of erythema score was reported for group I during the treatment.

Fig. 2.

Mean erythema score group (I) placebo, group (II) study agent, group (III) botanical extracts, and group (IV) probiotics, during the treatment. Data are expressed according to a four-point qualitative scale: 0 = absent, 1 = mild 2 = moderate, and 3 = severe. Asterisks indicate a significant difference to the control (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01)

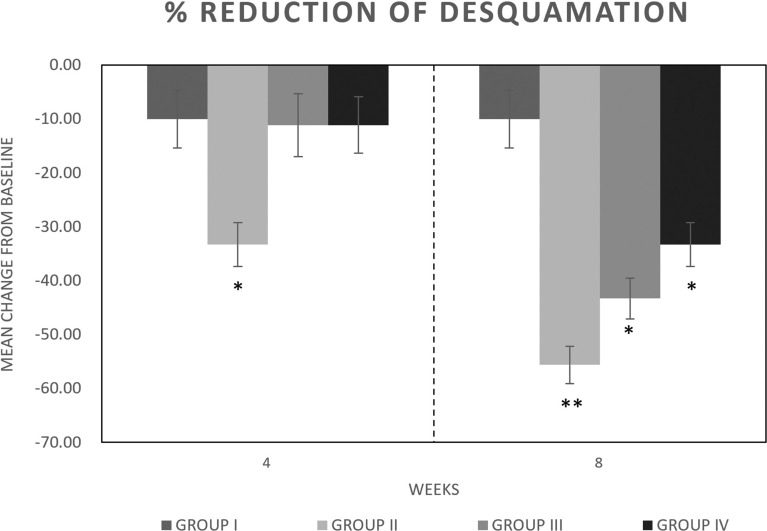

A significant (p < 0.05) decrease in mean desquamation score versus placebo (group I) was reported for group II after 4 and especially 8 weeks of treatment (Fig. 3) (−33.30% and −55.60%, respectively). A significant decrease in desquamation after 8 weeks of treatment was reported for groups III and IV (−43.30% and −33.30%, respectively) (Fig. 3). The highest effect was reported for group II. A slight (−10%) reduction in mean desquamation score was also reported for group I.

Fig. 3.

Mean desquamation score group (I) placebo, group (II) study agent, group (III) botanical extracts, and group (IV) probiotics, during the treatment. Data are expressed according to a four-point qualitative scale: 0 = absent, 1 = mild 2 = moderate, and 3 = severe. Asterisks indicate a significant difference to the control (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01)

Efficacy of the dietary supplements for acne was also measured in terms of reduction in sebum secretion rate from baseline by using a microcamera as presented in Table 3. In subjects treated with the study agent (group II) and the single components (group III and IV), the sebum secretion rate (% of subjects) was significantly reduced at the end of the study period (Table 3).

Table 3.

Sebum secretion rate (%)

| Visit | Sebum secretion rate (%, n) | Group I | Group II | Group III | Group IV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T0 | Low | 29 (8) | 10 (3) | 17 (5) | 22 (6) |

| Medium | 42 (12) | 47 (14) | 45 (13) | 48 (13) | |

| High | 29 (8) | 43 (13) | 38 (11) | 30 (8) | |

| T1 | Low | 32 (9) | 30 (9) | 38 (11) | 22 (6) |

| Medium | 50 (14) | 37 (11) | 41 (12) | 48 (13) | |

| High | 18 (5) | 33 (10) | 21 (6) | 30 (8) | |

| T2 | Low | 32 (9) | 60 (18) | 55 (16) | 63 (17) |

| Medium | 54 (15) | 27 (8) | 34 (10) | 33 (9) | |

| High | 14 (4) | 33 (4) | 11 (3) | 4 (1) |

n number of subjects

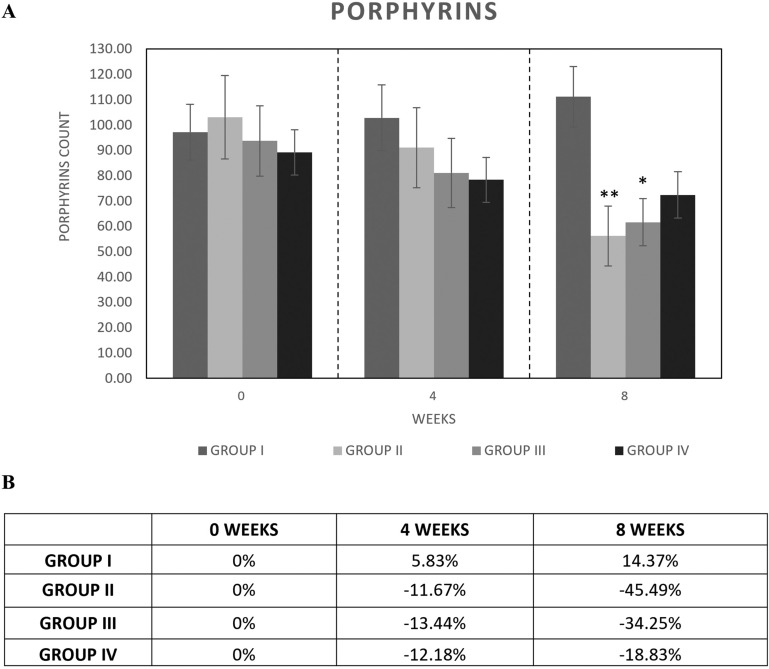

Porphyrin analysis revealed a significant (p < 0.05) reduction in the mean counts in group II after 8 weeks of use of the study agent (−45.49%) (Fig. 4). The treatment with botanical extracts (group III) produced a significant reduction in the mean porphyrin count after 8 weeks of treatment (−34.25%) compared with baseline (14.37%).

Fig. 4.

Porphyrin counts in group (I) placebo, group (II) study agent, group (III) botanical extracts, and group (IV) probiotics after 4 and 6 weeks of treatment. A Mean porphyrin counts; B % of porphyrin reduction compared with baseline. Asterisks indicate a significant difference to the control (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01)

C. acnes, S. epidermidis, and S. aureus are the three major microbial species found on the skin [27, 28].

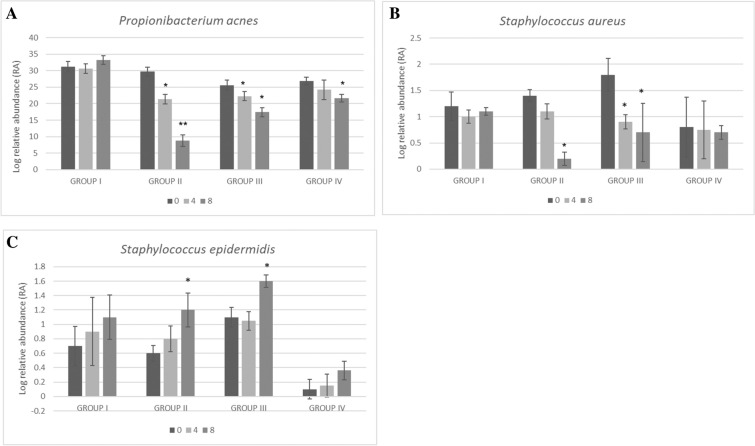

Relative abundance of predominant bacteria on the face of enrolled subjects was analyzed by mean of quantitative reverse-transcription PCR Real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR). Pan-bacteria-specific targets were used as control. Student’s t-test analysis of log relative abundance (RA) after 4 and 8 weeks of treatment compared with baseline showed a significant (p < 0.01) decrease in C. acnes (from 29.7 to 21.4 and 8.8 log RA, respectively) in group II subjects (Fig. 5A).

Fig. 5.

Relative abundance of main bacterial species on the face of enrolled subjects by RT qPCR. Log relative abundance of A C. acnes, B S. aureus, and C S. epidermidis in group (I) placebo, group (II) study agent, group (III) botanical extracts, and group (IV) probiotics after 4 and 6 weeks of treatment. Values are presented as mean ± SEM, in duplicate. Asterisks indicate a significant difference to the control (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01)

A significant (p < 0.01) but lower reduction was also reported in group III (from 25.6 to 22.3 and 17.4 log RA, respectively) and group IV (from 26.8 to 24.2 and 21.7 log RA, respectively).

Also, S. aureus was significantly (p < 0.05) reduced in group II (from 1.4 to 1.1 and 0.2 log RA, respectively) and group III (from 1.8 to 0.9 and 0.7 log RA, respectively) after 4 and especially 8 weeks of treatment (Fig. 5B). No significant changes were reported for S. aureus in group IV (Fig. 5B). Contextually, a significant (p < 0.05) increase in S. epidermidis was reported in group II (from 0.6 to 1.2 log RA) and group III (from 1.1 to 1.6 log RA) after 8 weeks of treatment (Fig. 5C).

No significant changes were reported for group I (Fig. 5).

Figure 6 shows a representative photographic evaluation of study agent acne in a volunteer of group II at baseline (Fig. 6A) and after 8 weeks of treatment (Fig. 6B).

Fig. 6.

Representative photographic evaluation of Primak Integratore acne in volunteer of group II. Notes: A Before treatment. B After 4 weeks of treatment

Discussion

There is growing evidence in support of the use of probiotics, mainly Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium strains, as treatment for acne [29]. Their effect on acne pathophysiology can be attributed to their anti-inflammatory properties [30–32] but also to their ability to maintain skin hydration [33] and barrier function [34, 35].

Moreover, probiotics are reported to be well tolerated, and an improvement in user compliance versus other therapies has been reported as well [29]. Interestingly, probiotics can synergize with antibiotics treatment [36] and counteract the side effects deriving from conventional anti-acne treatment such as isotretinoin, as reported by Fabbrocini and colleagues [37]. Another important aspect of acne treatment is preserving the microbiome, both cutaneous and intestinal [12]. Probiotics can rebalance the microbiome by boosting the levels of beneficial bacteria and controlling the growth of C. acnes, for example, by secreting bacteriocins [38].

Because traditional acne medications have various side effects, also the use of botanical extracts and secondary metabolites from medicinal plants is currently suggested as an alternative treatment [21].

A recent study by Kwon and colleagues [23] reported lupeol as a useful agent able to target most of the major pathogenic features of acne. Lupeol is reported to decrease the level of proinflammatory cytokines, modulate epidermal dyskeratosis (acting on IL-1 alpha, Toll-like receptor 2 Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR-2), and keratin 16), decrease sebum production, and reduce the synthesis of intracellular lipids via the modulation of the insulin-like growth factor type 1 receptor Insuline-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1R)/phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase (PI3K)/Akt/sterol response element-binding protein-1 (SREBP-1) signaling pathway.

Another natural alternative treatment for acne is Echinacea, for which safety and efficacy have been reported in vivo for other skin lesions, including in wound healing [39, 40]. Both antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory activity has been attributed to Echinacea. An in vitro study reported that Echinacea was able to inactivate C. acnes and inhibit the derived proinflammatory cascade. Echinacea was also reported to exhibit antioxidant activity [39–41], which could be useful to reduce the free radical production in acne. Thus, considering the in vitro and in vivo activities on different mechanisms involved in acne development reported for probiotics, lupeol, and Echinacea, a unique formulation composed of a combination of these was developed. This study compared the efficacy of a dietary supplement containing B. breve BR03 DSM 16604, L. casei LC03 DSM 27537, L. salivarius LS03 DSM 22776, lupeol, and Echinacea extract versus placebo, probiotics, or botanical extracts alone over 8 weeks of therapy in subjects with mild to moderate facial acne. It was possible to observe a significant improvement in inflammatory and noninflammatory signs of acne since 4 weeks of treatment, and this effect was further improved after 8 weeks of treatment. The observed effects may be due firstly to the anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial effects of probiotics, especially L. salivarius LS03 DSM 22776 [18]. A general higher improvement in acne symptoms was reported in subjects who took a daily oral dose of the complete dietary supplement. There was a greater than 56% reduction in the number of total facial lesions, expressed as GAGS score, after 4 and especially 8 weeks of supplementation with the dietary supplement versus placebo and single-component dietary supplement. A significant reduction also in erythema and desquamation score, porphyrins, and sebum production was reported.

Most interestingly, the dietary supplements containing both probiotics and botanical extracts acted on microbial dysbiosis by controlling the growth of C. acnes and S. aureus and simultaneously stimulating the growth of the most beneficial S. epidermidis.

In addition to clinical improvement, this study also reported good compliance with the treatment by the enrolled subjects.

Some limitations apply to the study such as its short-duration intervention, single site, relatively small population, and the possibility that noninflammatory lesions may resolve on their own.

Given that, to date, there are no published studies on the synergistic effects of probiotics, lupeol, and Echinacea on acne treatment, based on the results of this study, the combination of the above active ingredients may be a reasonably safe and compliant complementary treatment in mild to moderate acne.

Conclusion

The results from this study suggest that the administration of a dietary supplement containing B. breve BR03, L. casei LC03, L. salivarius LS03, lupeol, and Echinacea extract in subjects with mild to moderate facial acne is safe, well tolerated, and able to reduce total facial lesion count (GAGS score) versus placebo and probiotics and botanical extracts alone after 8 weeks of administration. Secondary endpoints analysis shows that the treatment significantly reduced erythema, desquamation, porphyrins, sebum, and microbial dysbiosis. Thus, the combination of effective active ingredients in a single dietary supplement seems to be a promising optional treatment to be used as an adjuvant for the treatment of inflammatory acne as well as for control of acne-prone skin. Larger randomized, placebo-controlled trials may substantiate our findings.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the participants of the study for their cooperation.

Funding

This research and the journal’s Rapid Service Fee was funded by Giuliani S.p.A.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given final approval for the version to be published.

Author Contributions

F.R. and D.P. conceptualized the study. D.P., L.M., and A.M. contributed to methodology. D.P. worked on the formal analysis. D.P. and F.R. carried out the investigation. D.P., M.P., A.A., L.M., and A.M. wrote the original draft. D.P. and F.R. reviewed and edited the manuscript. F.R. supervised the study. F.R. and G.G. acquired the funding.

Disclosure

Fabio Rinaldi serve as a consultant for Giuliani S.p.A., Daniela Pinto, Laura Marotta and Antonio Mascolo are employed by Giuliani S.p.A., Giammaria Giuliani is in the board of director of Giuliani S.p.A., Marco Pane and Angela Amoruso have nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This study was approved by the Independent Ethical Committee for Clinical not Pharmacological Investigation of Genoa, Italy and was in accordance with the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki of 1964.

Data Availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1.Heng AHS, Chew FT. Systematic review of the epidemiology of acne vulgaris. Sci Rep. 2020;10:5754. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-62715-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rocha MA, Bagatin E. Adult-onset acne: prevalence, impact, and management challenges. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2018;11:59–69. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S137794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hay RJ, Johns NE, Williams HC, Bolliger IW, Dellavalle RP, Margolis DJ, et al. The global burden of skin disease in 2010: an analysis of the prevalence and impact of skin conditions. J Investig Dermatol. 2014;134(6):1527–1534. doi: 10.1038/jid.2013.446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perkins AC, Maglione J, Hillebrand GG, Miyamoto K, Kimball AB. Acne vulgaris in women: prevalence across the life span. J Womens Health. 2012;21(2):223–230. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2010.2722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kang S, Cho S, Chung JH, et al. Inflammation and extracellular matrix degradation mediated by activated transcription factors nuclear factor-kappaB and activator protein-1 in inflammatory acne lesions in vivo. Am J Pathol. 2005;166:1691–1699. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62479-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Layton AM. Optimal management of acne to prevent scarring and psychological sequelae. Am J Clin Dermotol. 2001;2:135–141. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200102030-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kircik LH. Re-evaluating treatment targets in acne vulgaris: adapting to a new understanding of pathophysiology. J Drugs Dermatol. 2014;13:s57–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fabbrocini G, Cacciapuoiti S, Masarà A, Tedeschi A, Dall'Oglio F, Micali G. Linee Guida SIDEMAST per il trattamento dell'acne lieve e moderata. Pacini Editore Medicina eds. Pisa; 2015:1–12.

- 9.Kumasaka BH, Odland PB. Acne vulgaris. Topical and systemic therapies. Postgrad Med. 1992;92(5):181–183. doi: 10.1080/00325481.1992.11701492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zaenglein AL, Pathy AL, Schlosser BJ, Alikhan A, Baldwin HE, Berson DS, Bowe WP, Graber EM, Harper JC, Kang S, Keri JE, Leyden JJ, Reynolds RV, Silverberg NB, Stein Gold LF, Tollefson MM, Weiss JS, Dolan NC, Sagan AA, Stern M, Boyer KM, Bhushan R. Guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74(5):945–73.e33. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kelhälä HL, Aho VTE, Fyhrquist N, Pereira PAB, Kubin ME, Paulin L, Palatsi R, Auvinen P, Tasanen K, Lauerma A. Isotretinoin and lymecycline treatments modify the skin microbiota in acne. Exp Dermatol. 2018;27(1):30–36. doi: 10.1111/exd.13397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee YB, Byun EJ, Kim HS. Potential role of the microbiome in acne: a comprehensive review. J Clin Med. 2019;8(7):987. doi: 10.3390/jcm8070987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dréno B, Dagnelie MA, Khammari A, Corvec S. The skin microbiome: a new actor in inflammatory acne. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2020;21(Suppl 1):18–24. doi: 10.1007/s40257-020-00531-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goodarzi A, Mozafarpoor S, Bodaghabadi M, Mohamadi M. The potential of probiotics for treating acne vulgaris: a review of literature on acne and microbiota. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33(3):e13279. doi: 10.1111/dth.13279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu Y, Dunaway S, Champer J, Kim J, Alikhan A. Changing our microbiome: probiotics in dermatology. Br J Dermatol. 2020;182(1):39–46. doi: 10.1111/bjd.18670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hacini-Rachinel F, Gheit H, Le Luduec J-B, Dif F, Nancey S, Kaiserlian D. Oral probiotic control skin inflammation by acting on both effector and regulatory T cells. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4903. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Muizzuddin N, Maher W, Sullivan M, Schnittger S, Mammone T. Physiological effect of a probiotic on skin. J Cosmet Sci. 2012;63(6):385–395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deidda F, Amoruso A, Nicola S, Graziano T, Pane M, Mogna L. New approach in acne therapy: a specific bacteriocin activity and a targeted anti IL-8 property in just 1 probiotic strain, the L. salivarius LS03. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2018;52 Suppl 1. In: Proceedings from the 9th probiotics, prebiotics and new foods, nutraceuticals and botanicals for nutrition & human and microbiota health meeting, held in Rome, Italy from September 10 to 12, 2017, pp S78–S81. 10.1097/MCG.0000000000001053 (PMID: 29782471). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Clark AK, Haas KN, Sivamani RK. Edible plants and their influence on the gut microbiome and acne. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(5):1070. doi: 10.3390/ijms18051070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Magin PJ, Adams J, Heading GS, Pond DC, Smith W. Complementary and alternative medicine therapies in acne, psoriasis, and atopic eczema: results of a qualitative study of patients’ experiences and perceptions. J Altern Complement Med. 2006;12(5):451–457. doi: 10.1089/acm.2006.12.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Soleymani S, Farzaei MH, Zargaran A, Niknam S, Rahimi R. Promising plant-derived secondary metabolites for treatment of acne vulgaris: a mechanistic review. Arch Dermatol Res. 2020;312(1):5–23. doi: 10.1007/s00403-019-01968-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sharma N, Palia P, Chaudhary A, Shalini , Verma K, Kumar I. A review on pharmacological activities of lupeol and its triterpene derivatives. JDDT. 2020;10(5):325–332. http://jddtonline.info/index.php/jddt/article/view/4280. Accessed 8 Jul 2021.

- 23.Kwon HH, Yoon JY, Park SY, Min S, Kim YI, Park JY, Lee YS, Thiboutot DM, Suh DH. Activity-guided purification identifies lupeol, a pentacyclic triterpene, as a therapeutic agent multiple pathogenic factors of acne. J Investig Dermatol. 2015;135(6):1491–1500. doi: 10.1038/jid.2015.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sharma M, Schoop R, Suter A, Hudson JB. The potential use of Echinacea in acne: control of Propionibacterium acnes growth and inflammation. Phytother Res. 2011;25(4):517–521. doi: 10.1002/ptr.3288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Doshi A, Zaheer A, Stiller MJ. A comparison of current acne grading systems and proposal of a novel system. Int J Dermatol. 1997;36(6):416–418. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.1997.00099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pinto D, Sorbellini E, Marzani B, Rucco M, Giuliani G, Rinaldi F. Scalp bacterial shift in alopecia areata. PLoS One. 2019;14(4):e0215206. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0215206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xu Z, Wang Z, Yuan C, Liu X, Yang F, Wang T, et al. Dandruff is associated with the conjoined interactions between host and microorganisms. Sci Rep. 2016;6:24877. doi: 10.1038/srep24877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clavaud C, Jourdain R, Bar-Hen A, Tichit M, Bouchier C, Pouradier F, et al. Dandruff is associated with disequilibrium in the proportion of the major bacterial and fungal populations colonizing the scalp. PLoS One. 2013;8(3):e58203. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kober MM, Bowe WP. The effect of probiotics on immune regulation, acne, and photoaging. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2015;1(2):85–89. doi: 10.1016/j.ijwd.2015.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Azad MAK, Sarker M, Wan D. Immunomodulatory effects of probiotics on cytokine profiles. Biomed Res Int. 2018 doi: 10.1155/2018/8063647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bernini LJ, Simão ANC, De Souza CHB, et al. Effect of Bifidobacterium lactis HN019 on inflammatory markers and oxidative stress in subjects with and without the metabolic syndrome. Mineral Mag. 2018;120(6):645–652. doi: 10.1017/S0007114518001861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Benyacoub J, Bosco N, Blanchard C, Demont A, Phillippe D, Castiel-Higounenc I. Immune modulation property of Lactobacillus paracasei NCC2461 (ST11) strain and impact on skin defenses. Benef Microbes. 2014;5:129–136. doi: 10.3920/BM2013.0014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gueniche A, Phillippe D, Bastien P, Reuteler G, Blum S, Castiel-Higounenc I. Randomised double-blind placebo-controlled study of the effect of Lactobacillus paracasei NCC 2461 on skin reactivity. Benef Microbes. 2014;5:137–145. doi: 10.3920/BM2013.0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hashimoto K. Regulation of keratinocyte function by growth factors. J Dermatol Sci. 2000;24(Suppl. 1):S46–S51. doi: 10.1016/S0923-1811(00)00141-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pasonen-Seppanen S, Karvinen S, Torronen K, Hyttinen JM, Jokela T, Lammi MJ. EGF upregulates whereas TGF-beta downregulates the hyaluronan synthases Has2 and Has3 in organotypic keratinocyte cultures: correlations with epidermal proliferation and differentiation. J Investig Dermatol. 2003;120:1038–1044. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12249.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jung GW, Tse JE, Guiha I, Rao J. Prospective, randomized, open-label trial comparing the safety, efficacy, and tolerability of an acne treatment regimen with and without a probiotic supplement and minocycline in subjects with mild to moderate acne. J Cutan Med Surg. 2013;17(2):114–122. doi: 10.2310/7750.2012.12026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fabbrocini G, Cameli N, Lorenzi S, De Padova MP, Marasca C, Izzo R, Monfrecola G. A dietary supplement to reduce side effects of oral isotretinoin therapy in acne patients. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2014;149(4):441–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Silva DR, Sardi JD, de Souza Pitangui N, Roque SM, da Silva AC, Rosalen PL. Probiotics as an alternative antimicrobial therapy: current reality and future directions. J Funct Foods. 2020;73:104080. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2020.104080. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barnes J, Anderson LA, Gibbons S, Phillipson JD. Echinacea species (Echinacea angustifolia (DC.) Hell. Echinacea pallida (Nutt.) Nutt. Echinacea purpurea (L.) Moench: a review of their chemistry, pharmacology and clinical properties. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2005;57:929–954. doi: 10.1211/0022357056127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barrett B. Medicinal properties of Echinacea: a critical review. Phytomedicine. 2003;10:66–86. doi: 10.1078/094471103321648692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sharma M, Vohra S, Arnason JT, Hudson JB. Echinacea extracts contain significant and selective activities against human pathogenic bacteria. Pharm Biol. 2008;46:111–116. doi: 10.1080/13880200701734919. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.