Summary

Health promotion is thus not only a participatory practice, but a practice for empowerment and social justice. The study describes findings from a community-based participatory and challenge-driven research program. that aimed to improve health through health promotion platform in an ethnically diverse low-income neighbourhood of Malmö, Sweden. Local residents together with lay health promoters living in the area were actively involved in the planning phase and decided on the structure and content of the program. Academic, public sector and commercial actors were involved, as well as NGOs and residents. Empowerment was used as a lens to analyse focus group interviews with participants (n=322) in six co-creative health-promoting labs on three occasions in the period 2017-2019. The CBPR interview guide focused on the dimensions of participation, collaboration and experience of the activities. The CBPR approach driven by community member contributed to empowerment processes within the health promotion labs: Health promotors building trust in social places for integration, Participants motivate each other by social support and Participants acting for community health in wider circle. CBPR Health promotion program should be followed up longitudielly with community participants to be able to see the processes of change and empowerment on the community level.

Keywords: empowerment, CBPR, health promotion, urban neighbourhoods, Sweden, inequity, immigrant background

INTRODUCTION

Health promotion is an important tool for improving public health and reducing costs for national health systems. However, to achieve this potential, health promotion must empower, and match the varying needs and expectations of, the people it is oriented towards (WHO, 2017). The Jakarta Declaration thus states that

Health promotion is carried out by and with people, not on or to people. It improves both the ability of individuals to take action, and the capacity of groups, organizations or communities to influence the determinants of health. (WHO, 1997)

As part of national public health policies, as well as in the context of global and international policies, centralized management can lead to situations in which health promotion is instead framed and implemented in a top-down fashion. Assumed needs, problems and desirable changes in lifestyle or behaviours may then be primarily defined on the basis of population statistics, rather than by drawing on people’s own experiences, aspirations and preferences. Centralized approaches tend to frame people and communities as passive objects of interventions and ‘target groups’, rather than as actors in their own lives. Not only can this lead to mismatches between public policies and the populations they propose to serve (WHO, 2017), but a top-down centralized approach may also neglect the positive role that local communities can play. With respect to the European Health 2020 framework, it is therefore underlined that

Participatory approaches play a key role in addressing the link between marginalization and powerlessness, and in tackling the determinants of health inequities. [(WHO, 2017), p. 2]

The framework further emphasizes the need for local solutions to tackle the root causes of social inequities, where communities and individuals can engage as important partners in co-creating solutions (WHO, 2017).

This paper presents some of the findings from a 3-year programme in a neighbourhood in the outskirts of Malmö, Sweden, with a large proportion of inhabitants with an immigrant background. The demographic characteristics of this neighbourhood meant that many health concerns of the inhabitants were related to the status of immigrants in Swedish society. The programme aimed to develop a model for improving equitable access to health through challenge-driven innovation, using a participatory place- and community-based approach to health promotion. While programme outcomes were assessed along multiple dimensions, this paper above all focuses on the impacts of the programme in terms of empowerment, from the perspective of the involved citizens, and discusses possible implications of experiences from the participatory processes for health promotion practices more generally.

BACKGROUND

Immigration and social segregation in Sweden

In Sweden, as in other European countries, immigration is largely framed as a ‘problem’: a strain on scarce resources, a threat to social cohesion or a challenge to existing structures. The rise of far-right populist movements has contributed to stigmatizing persons of colour and Muslims [cf. (ECRI, 2018), pp 14−15]. Although anti-immigrant sentiment also affects the health sector, speaking about racism is sensitive and has been difficult to research in the Swedish context (Ahlberg et al., 2019; Bradby et al., 2019). Due to idealized perceptions of the Swedish welfare state, issues instead tend to be framed as ‘cultural’ (Eliassi, 2017), while the burden of integration is placed on the newcomers. At the same time, a lack of access to job markets and a lack of recognition of prior experiences or qualifications have contributed to downward social mobility among immigrants, as well as to economically, socially and ethnically segregated neighbourhoods (Obucina, 2014; Save the Children Sweden, 2014; Scarpa, 2015). Not only immigrants but also the areas they live in are thus exposed to stigmatization. Dahlstedt [(Dahlstedt, 2019), p. 89] points to the risk of understanding urban neighbourhoods as an ‘area of exclusion’—thus attributing causes of exclusion to the place and its inhabitants, rather than considering structural mechanisms in society at large.

Neighbourhoods with affordable housing accessible to immigrants are commonly labelled ‘socially vulnerable’ and ‘at risk’ and described as having a ‘high density of immigrants’, a term with negative connotations in Sweden (Scarpa, 2015). Such labelling, as well as a more recent discourse on ‘outsideness’ (utanförskap), contribute to the perception that these neighbourhoods and their inhabitants are problematic and somehow located ‘outside’ mainstream Swedish society (Dahlstedt, 2019). This, in turn, affects the identity, social position and future prospects of people who live there, as well as their opportunity to be heard and taken seriously in political debates. The social and cultural capital of inhabitants is not valued, while access to services and amenities may also be affected by both location and income.

While social exclusion and disempowerment related to status, class or perceived ethnicity have negative impacts on health and well-being (Haslam et al., 2012), health is also directly affected by income and environmental factors. International research suggests that people with lower socioeconomic status are more at risk for numerous health issues, and the WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health (CSDH) underlines the tremendous inequities in health caused by social injustice worldwide (WHO, 2008). Major divides exist globally, as well as within and across European countries (Dahlgren and Whitehead, 2006; WHO, 2013). For instance, Donkin et al. (Donkin et al., 2018) mention that between 45 and 60% of the variation in health status globally can be attributed to social and environmental influences, while differences in conditions lead to a 20-year gap in life expectancy between the richest and poorest parts of cities such as Glasgow, Baltimore or Washington DC.

Across numerous contexts, people with immigrant backgrounds tend to be in worse health than the general population, while also having less access to health care (Graetz et al., 2017). For instance, migrants have a higher incidence, prevalence and mortality rate for diabetes as compared with the host population (Stirbu et al., 2006), as well as a higher risk of ischaemic heart disease, hypertension and stroke (Sohail et al., 2015; Clementi et al., 2016). Access to care is hindered by language difficulties, and differences in expectations and migrants’ experiences of healthcare in their home countries are also common (Razavi et al., 2011; Luiking et al., 2019). War and violence in countries of origin are frequent causes of trauma, while mental health issues may also be connected to events during migration or post-migration conditions in the country of residence (Davies et al., 2009; Kirmayer et al., 2011; Steel et al., 2011; Mangrio et al., 2018). Importantly, the loss of their previous social circle, families and friends tends to negatively impact the mental health status of migrants (Morosanu, 2013). Both economic constraints and feelings of insecurity in their local environment [see, for instance (Putrik et al., 2015)] may contribute to social isolation and sedentary lifestyles, where inhabitants have few opportunities to go outside their own homes.

Widening inequality and the associated negative health impacts (WHO, 2013) do not only concern groups with an immigrant background in Sweden but can also be observed in phenomena such as youth unemployment, child poverty (Save the Children Sweden, 2014), the social isolation of the elderly (Larsson et al., 2017) and increasing barriers for people with disability (EU-SILC, 2018). It is particularly important to note that all these categorizations—whether regarding ethnicity, migratory background, age, gender or ability—do not correspond to homogenous groups and that the challenges and opportunities that people experience depend on contextual issues as well as on individual life stories and circumstances.

Health promotion and community empowerment

While inequality and social disparities within and across communities may drive ill health, community assets such as solidarity, mutual trust and social networks are recognized as protective factors that promote health and well-being (Stewart et al., 1999; Sherrieb et al., 2010). Health promotion is, therefore, a question of empowering communities (Wiggins et al., 2009) and supporting contexts and activities that build trust and strengthen social relationships, but it also has a structural dimension and requires supportive policies and conducive environments, as stated in the Ottawa Charter (WHO, 1986). Equally fundamental for health and health equity is the degree of control people in a community have over their environment, life situation and futures. The Ottowa Charter (WHO, 1986) thus defines health promotion as enabling people to increase control over their health, realize aspirations, satisfy needs and change or cope with the environment.

Lack of power has a dual impact on health. On the one hand, it constrains access to resources and affects the social determinants of health, such as education, occupation, poverty and social capital, leading to poor housing, dangerous jobs or exposure to pollution. It limits access to political arenas, allowing socially and economically inequitable systems to persist. On the other hand, alongside such material factors, being marginally positioned and disempowered in a society also has direct negative impacts (Haslam et al., 2012). Based on the Ottowa Charter for Health Promotion, and drawing on WHO European recommendations (WHO, 2017), the empowerment of communities and individuals is used in this study as a lens to analyse materials from the various activities of the programme. The term empowerment is here understood as a

(…) social action process, that promotes participation of people, organizations, and communities towards the goals of increased individual and community control, political efficacy, improved quality of community life and social justice. [(Wallerstein, 1992), p. 198]

The analysis also draws on Zimmerman’s (Zimmerman, 1995) definition of psychological empowerment, which includes the dimensions of people’s perceived control of their lives, their level of participation in community change and their critical awareness of social-economic or political contexts and targets for change.

The active participation of concerned community members is an essential aspect of empowerment processes in community development for health promotion (Laverack, 2006). Participation is also a crucial aspect of research on such processes. Due to power imbalances, underrepresented groups tend to be silenced not only in planning, management of practices and policy, but also in research aimed to improve their own health (Lynch, 1999).

Much of the work on supporting health equity in communities and international research in this area has been mediated by community health workers (CHW) (Fausto et al., 2011; Torres et al., 2013). The organization and funding of CHWs vary across contexts (Torres et al., 2013), but common features include proximity and strong engagement for social justice (Labonté, 2010). Trust requires continuity and long-term commitment (Labonté, 2010), something which is not easy to achieve when funding is project-based, instrumentalist and short term. There can also be tensions between the desire to professionalize community health work (Rosenthal et al., 2018) and maintaining proximity and primary loyalty to the community that is served. Belonging to the communities and speaking local languages are other factors for empowering community health work (Islam et al., 2017).

Community-based participatory research

For community-based participatory research (CBPR), participatory action research and participatory health research, participation is fundamental (Abma et al., 2017). Knowledge is understood as constructed in interaction (Wiggins et al., 2014), based on lived experience, and the approaches therefore aim to maximize participation in all stages of the research process [(Cook et al., 2017), p. 475]. CBPR empowers people and communities in an approach built upon the community members’ knowledge and skills, and starting with the partcipants’ problems and aspirations rather than the interests of researchers and professionals (Abma et al., 2017).

CBPR means much more than shared decisions between stakeholders, researchers and citizens. It is a more community-driven strategy, where the community besides participating in the research also decides research priorities and strategies and co-implements actions from findings. CBPR is also committed to social actions as part of the approach, where the community shares a common identity, and to building on the communities’ strengths with a long-term commitment and a common goal to translate knowledge into action in practice. In CBPR, favourable conditions for participation will substantially affect the outcomes of projects aiming to reduce health inequity through community empowerment (Wallerstein, 2006; Wallerstein et al., 2008). Equitable group dynamics have further been identified as a key factor for CBPR processes to support health equity (Ward et al., 2018). The WHO report on community empowerment emphasizes the significance of local organizations and social networks in these processes (WHO, 2018).

International research from a variety of contexts points to the positive long-term impacts of participatory community-based approaches to health [cf. (Laverack, 2006; Wallerstein, 2006; Salimi et al., 2012; Wiggins, 2012; Ward et al., 2018)]. Such impacts are likely to come not only from increased knowledge, better communication with healthcare providers and the development of contextually and culturally sensitive services better adapted to local needs, but also from the collective empowerment processes that participatory approaches entail. Stress is a major factor underlying and aggravating ill health and is also associated with the lack of power to act and make changes in circumstances concerning life, social relationships or work. Empowerment processes can thus be assumed to contribute to reducing stress and stress-related ill health, at the same time that empowered communities have more options to make effective positive changes to their local environments. Stronger and wider social support networks reduce pressures on the individual, contributing to psychosocial health and well-being.

The collaborative innovations for health promotion programme

As a way to reduce existing inequalities in health, the Collaborative Innovations for Health Promotion programme started in 2016, in Malmö, Sweden. Malmö is the third biggest town in Sweden and the programme took place in a neighbourhood with about 7800 residents, of whom ∼75% are first- and second-generation migrants. The average annual income for employed residents in the area in 2017 was 261 419 SEK compared with 363 942 SEK in the city of Malmö; 52% of residents aged 20–64 were employed, compared with 67% in the rest of the city (Malmö stad, 2019); 43% of the residents in the neighbourhood were born in Sweden; the five most frequent countries of birth other than Sweden were Iraq, Syria, Poland, Denmark and former Yugoslavia.

The initiative was a community-based participatory and challenge-driven research programme to create new ways to improve health through participatory and cooperative strategies in a health promotion platform. It involved five types of actors: academic (Malmö University), public sector (the region of Scania and the city of Malmö), commercial, NGOs and community members (Sjögren Forss et al., 2021). The multi-stakeholder perspective and the active involvement of local residents in the planning phase were essential to ensure community-driven processes adapted to local needs and circumstances. A total of 14 organizations and companies were involved in financing and contributing to the programme, while the Swedish national innovation agency Vinnova contributed with half of the funding (Vinnova Reg. No. 2016-00421, 2017-01272).

The initial pre-implementation of the programme—‘future workshops’

In the programme, three large ‘future workshops’ were used in the launching phase, to maximize the involvement and empowerment of the community. Future workshops were originally developed in post-war Germany (Jungk and Mullert, 1987) as a method for collective decision-making and visioning of the future. The approach has been extensively used in Sweden for participatory planning (Renblad et al., 2009). Members of the community were invited to participate and a total of 150 did so. They differed in age, gender and cultural background. Many were unemployed and had low education levels. Together they identified health promotion initiatives based on their perceived needs. The point of departure in these workshops was the open questions regarding what was promoting health in the neighbourhood (Figure 1).

Fig. 1:

The Collaborative Innovations for Health Promotion programme, Malmö Sweden.

The community members stated that their lifestyles, such as physical inactivity, poor food habits and mental health problems, had a negative impact on their self-perceived health and that they lacked the power to influence their situation. They also described having insufficient knowledge about how to promote their health and were dissatisfied with their contact with the Swedish healthcare sector. There was a clear lack of trust in the healthcare system, as well as towards authorities such as social services or the employment agency. Several lived alone, felt isolated from society and had no social context to be in.

In particular, female participants had very limited power over their own situation and life. They had the overall responsibility for their families and most of them had several children. The husbands often had more than one job, and many worked shifts to cope financially. All stated that they had a high workload with limited possibilities and time to relax, recover or take care of their body. Their current life situation in combination with memories and traumas from the past, especially from war, affected their mental health, while physical inactivity and isolation at home had a negative impact on their physical health.

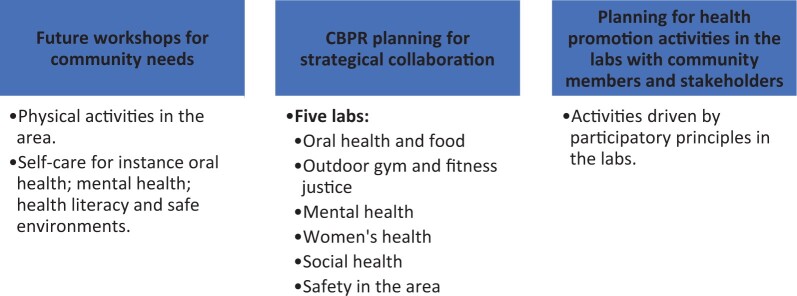

Factors identified by community members in the initial ‘future workshops’ as important aspects to focus on were: physical activities in the community; self-care of, for instance, oral health; mental health; health literacy; and safe environments. They wanted to create a sense of place and learning in co-creative living labs in social meeting places in the area. Based on the identified factors, the community members together with different stakeholders working in the area—from private, public and non-profit sectors and the academy—created a CBPR model for planning collaboration and designing the labs (verkstäder), i.e., participatory group activities aiming to promote better health for the citizens in the community as well as increased power and control over their situation.

The model was influenced by Wallerstein’s CBPR model (Wallerstein et al., 2008; Oetzel et al., 2018), focussing on factors such as empowerment and community participation, and the planning resulted in the design of six co-creative health-promoting labs: Oral health and food; Outdoor gym and Fitness Justice; Mental health (for people with disabilities); Women’s health; Social health for young adults; Safety in the area. As part of the planning, the community members and stakeholders also decided how to participate together in building trust from a community perspective. The community members were involved in the planning, implementation and evaluation of the model and were also the owners of the labs. More residents were recruited to the activities in the labs through snowball sampling, spreading information through face-to-face interactions, as well as using messages and flyers. Participants learned of the activities through hearing about them from others or through announcements. Each of the labs had a different aim but a common approach was adopted for community engagement across the activities. For example, there were families wanting culturally appropriate health information materials since the existing materials distributed by healthcare staff were based on the Swedish context and lifestyle. Therefore, one of the labs, in multistage focus group sessions, created new brochures on diet and sugar, based on foods the community used, and those brochures were disseminated at house parties, with the help of a PhD student and stakeholders from health and oral care (Ramji et al., 2020b). In the lab with physical activities, community members wanted a training programme based on their needs for free activities in the daytime where they could also test their physical health. Community members together with a health promoter performed physical activities outdoors and indoors and physical health was measured in the community setting by a researcher from the university in an intervention programme (Ramji et al., 2020a). In a lab focussing on safety in the area, school children were engaged in environmental planning, looking at secure and less secure places with photovoice (Enskär et al., 2020). The lab Mental health focussed on the participants being in a social context, meeting and socializing with others to decrease loneliness for community members with mental health problems in focus groups. Also, participants performed different social activities, for example, dancing and going on various day trips.

The health promoters facilitating the labs

The health promotional activities in the labs were coordinated by lay health promoters (N = 6) who were members in the community and had expressed interest in the programme during the initial ‘future workshops’. They were also involved in the CBPR planning and were employed by partners in the programme. All of them were first-generation immigrants, differing in gender, age and ethnic background (being, for example, from the Middle East and Eastern Europe). The lay health promoters were engaged as facilitators for the programme and sent information about the activities through social meeting places and invited community members in the neighbourhood. The health promoters did not have prior expertise in health issues but were recruited for their knowledge of the neighbourhood. They could be seen as facilitators for participant recruitment and language interpretation, as well as relationship and trust builders, since they had a continuous dialogue with the community members between the activities in the labs (Ramji et al., 2020a). The fact that the health promoters were residents of the neighbourhood and had various ethnic backgrounds was essential for trust, credibility and communication [cf. (Lugo, 1996; Aambo, 1997)]. In the initial period of recruiting participants for the labs, many joined because they knew the health promoters personally, while later on recruitment was driven by the positive experiences of the first participants.

The health promoters received training in participatory methodologies from academics and practitioners in order to document and reflect on the processes in the labs. Decisions within the labs were reached by consensus after occasionally extensive discussions. Conflicts and diverging interests sometimes emerged, and the health promoters received support from experienced practitioners to be able to jointly reflect on such tensions and maintain an open, respectful and pluralistic climate within the labs. The methods used within the labs included research circles, culture circles, photovoice, dialogue groups and storytelling. The health promoters were also engaged in the steering group, which was formed at the initial stage and included representatives from all stakeholders on a structural level. Participation in the programme involved community members in all processes and, therefore, it was important to evaluate this participation and analyse the processes of empowerment. Focus groups with community members were conducted in all labs during the programme. The results from the focus groups were presented in the steering group, in which stakeholders and community members discussed structural barriers and hindrances for the community. The stakeholders’ experiences were followed up in a study to evaluate the organization and the collaboration in the programme (Sjögren Forss et al., 2021). The present study only concerns the lab evaluations by neighbourhood residents.

METHODS

Participants

A total of 322 residents participated in the 6 co-creative health promotion labs. Three-quarters of the participants in the labs were female. Participants in the Women’s health lab were all female, and this lab had twice as many participants as the others. The majority of the participants in the Outdoor gym lab were also female, while gender distribution was almost equal in the remaining labs. The age distribution was relatively even: 110 participants were over 50; 86 were aged 30–50; 47 were aged 15–30, while 78 participants were aged 5–15. Participants’ countries of origin were Iraq, Lebanon, Korea, Syria, Pakistan, Chile, Palestine, Sweden, Finland, Algeria, Saudi Arabia, Bosnia, Morocco, Poland, Gambia, Sudan, China, Australia, Iran, Afghanistan, Serbia and Egypt.

Data collection

The material used for this study consists of 30 focus group interviews with 250 participants. The focus group interviews were conducted when the programme started, in 2017, and in Autumn 2018 and May–June 2019. All residents who had participated in the six co-creative health labs were invited to the focus group interviews, which took place in each of the six labs. Some participants were not able to take part in the interviews due to holidays, illness or other reasons. When needed, the health promoters functioned as translators. The composition of the focus groups is presented in Table 1.

Table 1:

Characteristics of participants

| Lab | Oral health and food (n = 45) | Outdoor gym and fitness justice (n = 35) | Mental health (n = 30) | Women’s health (n = 79) | Social health for young adults (n = 16) | Safety in the area (n = 45) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||||

| Range | 5 to >65 | 15 to >63 | 35 to >75 | 15 to >70 | 15 to 30 | 8 to 10 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Women (%) | 31 (69) | 32 (91) | 15 (50) | 79 (100) | 5 (31) | 20 (44) |

| Men (%) | 14 (31) | 3 (9) | 15 (50) | − | 11 (69) | 25 (56) |

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| Asian | − | 3 (9%) | − | − | − | 5 (11%) |

| European | 10 (22%) | 4 (11%) | 18 (60%) | − | 8 (50%) | 12 (27%) |

| Middle Eastern | 35 (78%) | 28 (80%) | 12 (40%) | 69 (88%) | 8 (50%) | 20 (44%) |

| Africa | − | − | − | 10 (12%) | − | 8 (18%) |

Thematic guide

To continuously evaluate how the collaboration was working and to assess whether the CBPR processes, with the support of the stakeholders, offered residents better opportunities to improve their health, community members and health promoters met in focus groups that were facilitated by researchers and the health promoters. A CBPR guide (Wallerstein, 2017) was used for the interviews focussing on the dimensions of power and trust in the collaboration, the degree of participation in the labs, the skills and resources and the outcome of the activities. This evaluation of the programme and the research activities conducted by participants was part of the CBPR approach used in the programme. It served to initiate and adjust the ongoing activities as research data and to inform discussions on the continuation after the 3-year period. The CBPR guide (Wallerstein, 2017) used in the focus-group interviews is designed to evaluate processes related to empowerment and participation in the collaboration, while research questions and evaluation criteria were decided by the participants based on the initial set of focus groups and the CBPR planning.

The CBPR approach (Wallerstein et al., 2008; Oetzel et al., 2018) adopted for the programme meant that neighbourhood residents, together with the other stakeholders, not only decided how to organize collaboration and which activities to conduct, but also which research questions to pursue and how to evaluate them. The criteria for assessing empowerment are in this sense internal to the programme, and cannot be readily compared as is the case for standardized assessment criteria. While the lack of standardized criteria is problematic for assessing the efficacy of various measures at national levels (WHO, 2018), the relevance and meaning of measures to the people involved is central to CBPR and in itself a criterion of participation. Besides the fact that the research questions and evaluation criteria grew directly out of the initial set of focus groups and the CBPR planning, participants in the co-creative health labs also decided research questions in the labs, as well as being involved in further developing them and developing solutions to the challenges that emerged during the process (Ramji et al., 2020b). Community members took part in the research findings for the various studies conducted within the programme and discussed, in the focus groups, the implications for the continuation of the programme.

Data analysis

In this study, empowerment was examined from two perspectives. On the one hand, we investigated the extent to which the programme contributed to community capacity building (Labonté and Laverack, 2001; Laverack, 2004), including levels of participation in community change (Wallerstein, 1992; Zimmerman, 1995). On the other hand, we sought to identify the specific aspects that were experienced as empowering by neighbourhood residents and how they could be strengthened. Particular attention was given in the analysis of the focus-group interviews to the moments that were experienced as significant by the participants and to those that increased their sense of control over their lives (Zimmerman, 1995).

All focus group interviews were tape-recorded and transcribed verbatim. The transcripts were read individually by the authors to get an overall understanding and to minimize the risk of prejudice (Polit and Beck, 2017). Thereafter, an inductive qualitative content analysis, inspired by Elo and Kyngäs (Elo and Kyngäs, 2008) was used in order to find the most important themes. Meaning units in the text that corresponded with the aim were condensed and coded and the coded meaning units were then interpreted and compared by the authors, as we wanted to find similarities and differences. Thereafter, the data was given to the health promoters to discuss and adjust. Finally, the codes were sorted into tentative themes without losing their content and the authors agreed on four themes: Empowerment processes within the co-creative health promotion labs; Group dynamics and mutual support; Improvements in health; and Mixing culture, language, age and gender.

Subsequently, we analysed the material from each lab separately. We were inspired by the analytical approach to case studies described by Creswell (Creswell, 2007), containing two steps. In the first step, the interviews from each lab were critically read numerous times. The text in from each lab was analysed and condensed looking for processes of participation, capacity building, community members’ sense of control and other aspects of empowerment. In the second step, we did a cross-analysis between all cases, focussing on similarities and differences, and found common processes for all the labs: Health promoters building trust in social places for integration; Participants motivate each other by social support; and Participants acting for community health in wider circles. This process was discussed with together with the health promoters in each lab. The community members were also given continuous feedback by the health promoters.

Ethical issues

Informed consent and ethics committee approval were obtained at the outset of the programme (Reg. No. 2016-00421, 2017-01272). In participatory projects, however, ethical considerations go far beyond compliance with ethics requirements (Lahman, 2018), and notably involve changing conventional power relationships between academic partners and communities (Banks and Brydon-Miller, 2019). For initiatives that aim to reduce health inequity by empowering communities, conditions for participation and equitable relationships in the processes are central issues (Wallerstein et al., 2008; Ward et al., 2018). The approach of the programme focussed on the community members’ perceived needs and what they wanted to do about them. Thus, the risk of stigmatization as well as the risk that other actors, such as the stakeholders, set the agenda for activities, was reduced.

RESULTS

Empowerment processes within the co-creative health promotion labs

While positive changes were experienced by most of those who participated in the interviews in the various co-creative health promotion labs, the effects were most noticeable for the women. In order for the programme to move beyond the core groups that were formed during the ‘future workshops’ and mobilize more widely in the community, residents from the neighbourhood, particularly women, initially needed to be persuaded by the health promoters to participate in the various activities. They agreed to participate in the activities since they knew the health promoters and trusted that they cared for their well-being and recommended activities that were appropriate for them. There was a general perception of a lack of availability and accessibility to health-promoting activities in the neighbourhood, like physical training and dietary counselling for women. The women also wanted to have the activity in the daytime and for free since they were unemployed and the families struggled with poor incomes.

Participants felt uncertain and did not show confidence in the beginning, since all activities were conducted in groups and participants knew only the health promoter. Eventually, they began to connect with other members of the group with whom they developed a social relation given that they met regularly. Participants interacted with each other even outside the times they met as a group, through meeting for coffee, having barbecues together in the area and going on excursions with their families. Besides the health benefits, the social interaction within the activity groups led to an increased sense of safety in the neighbourhood for the women, who otherwise never interacted with others when they were outside, in the supermarket or elsewhere in the neighbourhood centre. After participation in the activities, the women also believed that they could together create the environment they initially believed was lacking in the neighbourhood: a social environment open to all without differences, aiming to promote health and well-being. Participants who had initially been reluctant to participate or make changes in their lifestyle and routines had a complete change of mind, in that they believed that they could change their own lives and also be role models or change agents for families, relatives and friends within the neighbourhood. Besides spreading their knowledge within the neighbourhood, participants also informed their family and friends in their countries of origin; some of them even expressed their desire to become lay health promoters themselves.

The women said that in the labs they had the opportunity to state their opinions and that there was always someone who listened to them. In the lab, they experienced a learning process in which they supported each other to understand what they could do by themselves. Many were not used to having someone listen to their opinions:

Here is someone that listens. No one has listened to me before.

Social interaction was described as very important. The women stated that they worked for each other and for the group and they had a strong wish to help each other and to share their knowledge. As a result, they felt that they could affect their situation and by helping and learning from each other they had realized the possibility to have a stronger influence in society. They thought it was important for the future that they worked together, and pointed out that everyone could contribute in some way:

We learn from each other. Some can sew and can teach others how to do and others can help those who cannot read or write.

In the physical activity lab, the participants thought that they could act as role models to attract more residents in the neighbourhood to join in, for example, by telling others about their own experiences. As a result of newfound faith in themselves, they stated that they could act as instructors to others.

Group dynamics and mutual support

It is noteworthy that in the interviews, all participants expressed that they had felt involved in the activities in the labs and that they appreciated the discussions. The importance of being in a group was remarked on by most of the participants. Many had come to the labs since they wanted to get away from home and be together with others to break their isolation. However, some of the women were uncomfortable with participation in physical activities together with men. It was important to be in a social context and to talk and laugh together, but also to reflect on their own problems and realize that many are in the same situation of isolation.

The participants in the physical activity lab felt very positive about exercising together with others in a group and a fellowship was created, where they supported each other, laughed together and got to know new people. The group acted as a motivator, as individuals respected each other, keeping their promises to continue participating.

Those who participated in the lab about mental health highlighted the importance of being in a social context as well as meeting others and being seen as an individual even when part of a group. The isolation many had experienced before was now gone and they looked forward to coming to the lab:

I feel like a human again. Because when you are at home alone, I have tried so I know, finally you lost your own dignity. Yes, it is like this that humans are not going to be alone.

In the group, they felt able to trust each other, helped and cared for each other, and were responsive if someone needed extra support. They had found a context in which they could be alone among others, where they were accepted and did not have to live up to all of the social codes in society:

We try to be alone in a group, we are all alone but here we are alone together in the group. Here is cohesion and always someone to ask for help. And we had known each other for so long so you know what is wrong if someone acts strange.

Improvements in health

Participants stated that being engaged in the labs had contributed to changed habits. In the oral health and nutrition lab, all participants had in some positive way changed their food habits. They now ate less sugar and more vegetables. Some said that they ate less white bread and many children had fruit and vegetables for breakfast. Children also consumed less sweets candy than before, often just once per week. As a result, both parents and children stated that they felt better when compared with before. They had more energy and fewer sleeping problems and were losing overweight. The children had told classmates about what they had learned in the lab and were proud and happy that they could give their friends new knowledge.

In the lab about physical activity and fitness, all participants were more physically active as compared with before and stated that it had resulted in both better physical and mental health Their body awareness had increased; they had become more aware of how to use their body in daily life, for example, how to properly lift and carry. Some had started to do activities at home with their children and, thus, physical activity had become a greater part of their daily lives.

The participants in the mental health lab experienced better mental health; they had a place to go and were not just sitting at home alone watching television. They had found a place for individual recreation in a social context that gave them a belief in the future. In the lab about women’s health, the participants were encouraged to solve their problems and discover activities to perform through storytelling. They developed their own education by starting a health circle and inviting different professionals to discuss their problems with, e.g. professionals from primary care, a trauma consultant and lecturers from the university. The invited professionals developed an understanding of the context and the situation of the women, and the women received knowledge about a variety of health issues.

Many of the participants highlighted the importance of the labs being located in the neighbourhood, in which they felt safe and familiar. Most of the participants did not know each other before they came to the labs and appreciated that they had made new friends and met more residents in the neighbourhood. Some stated that safety in an area is built when people come together and get to know each other. The more people you get to know, the better it is. Participation in the labs improved their social networks in the area and helped them to feel safer. One participant said

To exercise in this group, with new people, it gives a real security in the area.

Mixing culture, language, age and gender

In the labs, the participants met others from different cultures, different languages were spoken and, in most of the labs, both women and men of different ages participated, which was seen as positive by participants. That the health promoters spoke different languages, mostly Swedish, English and Arabic, in the groups, was experienced as positive and some stated that it was good to be together with others speaking Swedish.

It was important to respect each other, especially since the participants came from different cultures and had different religions. In the lab about mental health, the participants focussed on what they had in common and had realized that it was a lot. One participant stated:

We assume that we are all the same, all of us are a little wacky and thus, we have the same rights. We don’t care about our origin.

Also, by meeting and talking, the participants stated that it had been easier to understand their differences but also to see what they had in common.

Processes during the programme

For the six labs, an analysis of the documentation shows that the process went through the same steps.

Health promoters building trust in social places for integration

1. The starting point was trust in the health promoters, who were all laypersons from the neighbourhood, and who had, mostly, personally invited the participants to join the lab.

2. The meeting places played a role since they were communal spaces for residents of the neighbourhood, rather than part of formal institutions such as the primary care facilities. Participants expressed that it meant a lot to find a space where issues they found important were discussed, and where their opinion mattered.

Participants motivate each other by social support

3. Much of the motivation to continue attending the gatherings came from the sense of social togetherness that participants felt in the group. Apart from the lab at the school, many participants did not know each other before and most came from quite different backgrounds.

4. The friendships that developed over time meant that participants started meeting also outside the labs, providing a strong motivation to continue to participate. The women, in particular, started supporting each other with their personal family concerns.

Participants acting for community health in wider circles

5. After having participated for a while, participants wanted to take a more active role in health promotion. They invited family members and members of their networks to the labs, as well as encouraging people they knew to adopt healthier lifestyles. Participants’ outreach was not limited to the neighbourhood; they were also concerned with giving advice to people they knew in their countries of origin, or to those who had emigrated to other countries. The active engagement of participants made the labs known in wider circles, and brought new people into the activities, including from other parts of town.

The process for the various labs thus moved from a sense of resignation and powerlessness—with little energy to undertake any activities—towards a state of increasing energy, optimism and motivation to take initiatives, not only concerning their personal lives, but also for the community and wider networks. Trust and positive interpersonal interaction during the meetings played a key role in the process. Additional impetus was given through the new friendships and social networks that developed in the neighbourhood, and through the sense of pride that the visibility of the programme had, both locally and in the wider city of Malmö.

DISCUSSION

The CBPR approach in health promotion has contributed to community-inspired outcomes and empowerment processes in six health promotion labs in a neighbourhood outside traditional health institutions, driven by community members. All the six labs followed the same steps in a process of dialogue and action empowering the community: Health promoters building trust in social places for integration, Participants motivate each other by social support and Participants acting for community health in wider circles.

Local lay health promoters were important for building trust and by promoting social support they also strengthened the community members’ motivation to continue the health promotion activities in the labs by promoting social support. The health promoters, mostly women, were the link for building trust between different groups of community members, and an important tool to achieve psychological empowerment as well as being brokers for building community capacity (Wenger, 1998; Michael et al., 2008). The social togetherness and friendship created a social sustainability over time that was important for community members’ experience of health and well-being. Earlier research has shown that residents with a migrant background often lose their social circles. Combined with economic constraint and isolation this can negatively impact mental health status (Morosanu, 2013; Putrik et al., 2015). As a result of the engagement in the labs, many community members with a migrant background experienced improvements in mental and physical health, for example, by losing weight and getting more energy, having fewer sleeping problems and experiencing less social isolation (Ramji et al., 2020a,b).

The co-creative labs were located in the local neighbourhood, close to home, with activities based on inclusion regardless of age, gender and ethnicity. As they served as physical venues in which social interaction and the formation of social ties took place, these labs could be related to the concept of third places: ‘public places that host the regular, voluntary, informal, and happily anticipated gatherings of individuals beyond the realms of home and work’ [(Oldenburg, 1999), p. 16]. Knowledge from the labs was transferred by the involved community members not only to other residents in the neighbourhood but also to other areas in the city of Malmö and to the participants’ home countries.

Addressing health inequity involves seeing people as assets rather than as ‘problems to be fixed’, and it involves empowering local communities to take greater control over factors such as service design or how the neighbourhood they live in is developed and managed [(WHO, 2017), p. 9]. As Lorenda Belone et al. (2016) argue, academic literature and experts’ papers are often built upon a certain consensus and it is important to get community input in order to assess face validity and acceptability and to strengthen community voices in health promotion research.

However, although community-based approaches have in certain contexts been able to inform policy and effect deeper changes, health promotion as such has little scope to change the underlying structural causes of unequal access to health, unless a wider mobilization is achieved and awareness is raised across broad segments of society. Among the findings in the analysis of the focus-group interviews with neighbourhood residents who participated in the labs, one of the findings was that the sense of empowerment they expressed was connected to the rapid physical health improvements that they experienced subjectively. Breaking social isolation and having an increased sense of security and safety in their immediate surroundings, were also significant outcomes that contributed to feeling empowered.

The processes of the programme, Collaborative Innovations for Health Promotion, effected positive changes in the participants’ sense of identity, both individually and in terms of belonging to the neighbourhood. Feelings of increased confidence and empowerment expressed by lab participants are similar to those expressed by community health workers in a study by Wiggins et al. (Wiggins et al., 2014) and the importance of social support found in the interviews is consistent with findings by Michael et al. (Michael et al., 2008) and Lugo (Lugo, 1996). The programme was significant in helping to break social isolation and enabling the sharing of feelings, particularly for some of the female participants [cf. (Lugo, 1996; Aambo, 1997)].

As argued by Haslam et al. (Haslam et al., 2012), health is closely linked to the status of people’s identity and their position in society. Thus, the empowerment processes of the programme had impacts not only within the different co-creative health promotion labs and for their participants but also by improving the status of the entire neighbourhood. Additionally, the involvement of multiple stakeholders offered numerous opportunities for residents to meet and engage in dialogue with local authorities. Community members were in a clear majority in the labs (compared with other stakeholders and researchers) and made decisions regarding the participation processes, handled the planning and managed the labs together with local lay health promoters. According to the participation ladder model (Arnstein, 1969), one could argue that the citizens experienced a high degree of control in this participation. However, while the outcomes of these meetings were constructive, impacts on policy have so far been limited. Despite overwhelmingly positive responses from all involved, the future is uncertain, since a minimum of funding is required to employ local health promoters and to ensure continued organization and coordination. The large number of stakeholders and the considerable investment of time and resources also posed challenges to the programme in terms of high and sometimes incompatible expectations on outcomes, prioritizing immediate measurable results over long-term holistic community development (Ortiz, 2003; Cook et al., 2017).

An initial discussion in the programme was to develop a CBPR programme that could be used in other locations to improve access to health. Although the outcomes indicate that the programme was successful in engaging and mobilizing the inhabitants of the neighbourhood, the structural issues were only partly resolved. In other words, progress was made in terms of psychological empowerment (Zimmerman, 1995), and in community capacity building (Wallerstein, 1992; Labonté and Laverack, 2001), but not in achieving a systemic shift in realizing the goals of social justice, further-reaching policy changes or impacting material conditions connected to the social determinants of health (Labonté and Laverack, 2008). It is too early to evaluate if the programme has had positive impacts in this respect. However, we wish to argue that both psychological and community empowerment (Laverack, 2004) are in themselves important aspects of the social determinants of health (Wallerstein, 1992; Haslam et al., 2012). Despite the commitment of local authorities, the experience from the programme Collaborative Innovations for Health Promotion, illustrates the difficulties in changing barriers because of the inflexibility and rigidity in the partners’ own organizations (Sjögren Forss et al., 2021). The success of any programme using this model is therefore likely to depend above all on how committed authorities are to rethinking their own structures and involving citizens as decision-makers. Findings from the programme nevertheless suggest that adopting a participatory and place-based approach does have the potential to strengthen communities, improving health conditions and quality of life (Enskär et al., 2020; Ramji et al., 2020a,b). A significant finding concerning applying insights from the Collaborative Innovations for Health Promotion initiative elsewhere, is that it was possible to jump-start the process of community-building by investing in the ‘future workshops’, before using the CBPR-planning model, and leaving sufficient time and openness for agreements to be reached. Another key aspect in enabling citizen engagement was giving the lay health promoters a wide scope of action combined with support in facilitating group processes.

Strengths and limitations

The materials analysed here originate from interviews with participants in the programme activities and thus do not cover the population of the neighbourhood as a whole, although impacts from the activities extended far beyond the groups who were directly engaged in them. Participation is likely to have depended on having available time, feeling comfortable with space and group dynamics, as well as feeling that the activities were relevant or interesting. Efforts were made to make activities accessible in terms of location, time and language.

Despite limitations deriving from the programme design, looking closer at participants’ experiences and perceptions shows aspects that have the potential to be driven further by members of the community. The analysis makes contributions to our understanding of health promotion practices and exposes areas in which a mismatch may exist between perceived benefits of these practices from the perspective of policymakers or health practitioners and the intended beneficiaries. Importantly, continued engagement in meetings and activities over time allowed participants to collectively deepen their reflections on and understandings of the processes, in ways that cannot be adequately captured through isolated surveys or pre/post studies.

Suggestions for future research

The health promotion programme should be followed up longitudinally to be able to see the processes of change and empowerment on the community level. Furthermore, the relevance of places to health and quality of life is under-researched in CBPR and should be explored in rural as well as urban settings (Lorena Belone et al; 2016)).

CONCLUSION

During the programme, the CBPR processes created an opportunity to discuss health issues with others from the neighbourhood and to collectively develop strategies for improving health for oneself and others in the neighbourhood. This contributed to better access to existing services and initiated a dialogue with authorities and care providers. The empowerment processes, grounded in trust building and social support, were the same in all the six labs, irrespective of participants’ age, ethnicity and gender and the labs’ different activities. Lay health promoters developing arenas for social interactions strengthened community members’ participation in the labs and enabled individuals to develop new resources suited to their own needs and preferences, as well as making conscious informed choices concerning various aspects of their health, such as diet, exercise and engaging in stimulating activities. The programme not only contributed to confidence and initiative-taking among participants but also improved social interaction, trust and the sense of belonging in the neighbourhood more generally. In the processes of empowerment, the location of the labs in social meeting places close to people’s homes played an important role. Integrating diverse groups in the labs increased understanding, empathy and solidarity across generations and cultural boundaries.

Contributor Information

Helen Avery, Center for Middle Eastern studies, Lund University, Lund, Sweden.

Katarina Sjögren Forss, Faculty of Health and Society, Department of Care Science, Malmö university, Malmö, Sweden.

Margareta Rämgård, Faculty of Health and Society, Department of Care Science, Malmö university, Malmö, Sweden.

REFERENCES

- Aambo A. (1997) Tasteful solutions: solution-focused work with groups of immigrants. Contemporary Family Therapy, 19, 63–79. [Google Scholar]

- Abma T., Cook T., Rämgård M., Kleba E., Harris J., Wallerstein N. (2017) Social impact of participatory health research—collaborative non-linear processes of knowledge mobilisation. Educational Action Research, 25, 489–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahlberg B., Bradby M., Hamed H.S., Thapar-Bjorkert S. (2019) Invisibility of racism in the global neoliberal era: implications for researching racism in healthcare. Frontiers in Sociology, 4, 61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnstein S. R. (1969) A ladder of citizen participation. Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 35, 216–224. [Google Scholar]

- Banks S., Brydon-Miller M. (2019) Ethics in Participatory Research for Health and Social Well-Being: Cases and Commentaries. Routledge, London. [Google Scholar]

- Bradby H., Thapar-Björkert S., Hamed S., Ahlberg B. M. (2019) Undoing the unspeakable: researching racism in Swedish healthcare using a participatory process to build dialogue. Health Research Policy and Systems, 17, 43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clementi A., Buiatti M., Mussinelli R., Salinaro F., Andreucci V. E., Balducci A. et al. (2016) Higher prevalence of hypertension in migrants in Italy. Journal of Hypertension, 34, e60–e61. [Google Scholar]

- Cook T., Boote J., Buckley N., Vougioukalou S., Wright M. (2017) Accessing participatory research impact and legacy: developing the evidence base for participatory approaches in health research. Educational Action Research, 25, 473–488. [Google Scholar]

- Dahlgren G., Whitehead M. (2006) European Strategies for Tackling Social Inequities in Health: Levelling up Part 2. World Health Organization, Copenhagen. [Google Scholar]

- Dahlstedt M. (2019) Problematizing the urban periphery: discourses on social exclusion and suburban youth in Sweden. In Keskinen S., Skaptadottír U. D., Toivanen M. (eds) Undoing Homogeneity: Migration, Difference and the Politics of Solidarity. Routledge, London, pp. 88–102. [Google Scholar]

- Davies A. A., Basten A., Frattini C. (2009) Migration: a social determinant of the health of migrants. International Organization for Migration (IOM). Geneva, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- Donkin A., Goldblatt P., Allen J., Nathanson V., Marmot M. (2018) Global action on the social determinants of health. BMJ Global Health, 3, e000603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eliassi B. (2017) Conceptions of immigrant integration and racism among social workers in Sweden. Journal of Progressive Human Services, 28, 6–35. [Google Scholar]

- Elo S., Kyngäs H. (2008) The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62, 107–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- European Commission Against Racism and Intolerance. (2018) Fifth Report on Sweden. (Adopted on 5 December 2017/published on 27 February Council of Europe, Strasbourg.

- Enskär K., Isma G., Rämgård M. (2020) Safe environments: Through the eyes of nine- yearold schoolchildren from a socially vulnerable area in Sweden. Child Care Health and Development, 47, 1,57–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fausto M. C., Giovanella L., de Mendonça M. H., de Almeida P. F., Escorel S., de Andrade C. L. et al. (2011) The work of community health workers in major cities in Brazil: mediation, community action, and health care. The Journal of Ambulatory Care Management, 34, 339–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graetz V., Rechel B., Groot W., Norredam M., Pavlova M. (2017) Utilization of health care services by migrants in Europe – a systematic literature review. British Medical Bulletin, 121, 5–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haslam C., Jetten J., Alexander S. H. (2012) The Social Cure: Identity, Health and Well-Being. Psychology Press, Hove, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Islam N., Shapiro E., Wyatt L., Riley L., Zanowiak J., Ursua R. et al. (2017) Evaluating community health workers’ attributes, roles, and pathways of action in immigrant communities. Preventive Medicine, 103, 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jungk R., Mullert N. (1987) Future Workshops: How to Create Desirable Futures. Institute for Social Inventions, London. [Google Scholar]

- Kirmayer L. J., Narasiah L., Munoz M., Rashid M., Ryder A. G., Guzder J. et al. ; Canadian Collaboration for Immigrant and Refugee Health (CCIRH). (2011) Common mental health problems in immigrants and refugees: general approach in primary care. Cmaj: Canadian Medical Association Journal = Journal de L'association Medicale Canadienne, 183, E959–E967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labonté R., Laverack G. (2001) Capacity building in health promotion, Part 1: for whom? And for what purpose? Critical Public Health, 11, 111–127. [Google Scholar]

- Labonté R., Laverack G. (2008) Health Promotion in Action: From Local to Global Empowerment. Palgrave Macmillan, London. [Google Scholar]

- Labonté R. (2010) Health promotion and empowerment: reflections on professional practice. In Black J. M., Furney S., Graf H. M., Nolte A. E. (eds) Philosophical Foundations of Health Education. Jossey-Bass, pp. 179−195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahman M. K. E. (2018) Ethics in Social Science Research: Becoming Culturally Responsive. SAGE, Thousand Oaks, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Larsson H., Rämgård M., Bolmsjö I. (2017) Older persons’ existential loneliness as interpreted by their significant others—an interview study. BMC Geriatrics, 17, 138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laverack G. (2004) Health Promotion Practice: Power and Empowerment. Sage, London. [Google Scholar]

- Laverack G. (2006) Improving health outcomes through community empowerment: a review of the literature. Journal of Health, Population, and Nutrition, 24, 113–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenda Belone J.E., Lucero J.E., Duran B., Tafoya G., Baker E.A., Chan D., Greene-Moton J.E., Kelley M., Wallerstein N. (2016) Community-Based Participatory Research Conceptual Model: Community Partner Consultation and Face Validity. Quality Health Research, 26(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luiking M.‐L., Heckemann B., Ali P., Doorn C., Ghosh S., Kydd A. et al. (2019) Migrants’ healthcare experience: a meta-ethnography review of the literature. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 51, 58–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lugo N. R. (1996) Empowerment education: a case study of the resource sisters/Compañeras program. Health Education Quarterly, 23, 281–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch K. (1999) Equality studies, the academy and the role of research in emancipatory social change. Economic and Social Review, 30, 41–70. [Google Scholar]

- Malmö stad [(2019) Malmö City]. https://malmo.se/Fakta-och-statistik/Statistik-for-Malmos-omraden.html (last accessed 11 June 2020).

- Mangrio E., Zdravkovic S., Carlson E. (2018) A qualitative study of refugee families’ experiences of the escape and travel from Syria to Sweden. BMC Research Notes, 11, 616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morosanu L. (2013) Between fragmented ties and ‘soul friendships’: the cross-border social connections of young Romanians in London. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 39, 353–372. [Google Scholar]

- Michael Y. L., Farquhar S. A., Wiggins N., Green M. K. (2008) Findings from a community-based participatory prevention research intervention designed to increase social capital in Latino and African American communities. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 10, 281–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obucina O. (2014) Paths Into and Out of Poverty Among Immigrants in Sweden. Acta Sociologica, 57, 5–23. [Google Scholar]

- Oetzel J., Wallerstein N., Duran B., Sanchez-Youngman S., Nguyen T., Woo K. et al. (2018) Impact of participatory health research: a test of the CBPR conceptual model: pathways to outcomes within community. Academic Partnerships. Biomedical Research International, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Oldenburg R. (1999) The Great Old Place. Merlow, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz L. M. (2003) Multicultural Health Brokering: Bridging Cultures to Achieve Equity of Access to Health. Doctoral dissertation, University of Alberta.

- Polit D. F., Beck C. T. (2017) Nursing research. Generating and Assessing Evidence for Nursing Practice. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA. [Google Scholar]

- Putrik P., de Vries N. K., Mujakovic S., van Amelsvoort L., Kant I., Kunst A. E. et al. (2015) Living environment matters: relationships between neighborhood characteristics and health of the residents in a Dutch municipality. Journal of Community Health, 40, 47–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renblad K., Henning C., Jegermalm M. (2009) Future Workshop as a Method for Societally Motivated Research and Social Planning. In Henning C., Renblad K. (eds) Perspectives on Empowerment, Social Cohesion and Democracy: An International Antology. School of Health Sciences, Jönköping, Sweden, p. 185. [Google Scholar]

- Ramji R., Carlson E., Kottorp A., Shleev S., Awad E., Rämgård M. (2020a) Development and evaluation of a physical activity intervention informed by participatory research-a feasibility study. BMC Public Health, 20, 112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramji R., Carlson E., Brogårdh-Roth S., Olofsson A. N., Kottorp A., Rämgård M. (2020b) Understanding behavioural changes through community-based participatory research to promote oral health in socially disadvantaged neighbourhoods in Southern Sweden. BMJ Open, 10, e035732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Razavi M. F., Falk L., Bjorn A., Wilhelmsson S. (2011) Experiences of the Swedish healthcare system: an interview study with refugees in need of long-term healthcare. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 39, 319–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal E. L., Menking P., St. John J. (2018) The Community Health Worker Core Consensus (C3) Project: a Report of the C3 Project Phase 1 and 2. Together Leaning toward 3 the Sky: A National Project to Inform CHW Policy and Practice. Texas Tech University HealthSciences Center, El Paso. [Google Scholar]

- Salimi Y., Shahandeh K., Malekafzali H., Loori N., Kheiltash A., Jamshidi E. et al. (2012) Is community-based participatory research (CBPR) useful? A systematic review on papers in a decade. International Journal of Preventive Medicine, 3, 386. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Save the Children Sweden. (2014) Barnfattigdom i Sverige, Årsrapport 2014 [Child Poverty in Sweden: Annual Report 2014]. Save the Children Sweden, Stockholm. [Google Scholar]

- Scarpa S. (2015) The Spatial Manifestation of Inequality: Residential Segregation in Sweden and Its Causes. Doctoral dissertation. Linnaeus University. [Google Scholar]

- Sherrieb K., Norris F. H., Galea S. (2010) Measuring capacities for community resilience. Social Indicators Research, 99, 227–247. [Google Scholar]

- Sjögren Forss K., Kottorp A., Rämgård M. (2021) Collaborating in a penta-helix structure within a community based participatory research programme: ‘wrestling with hierarchies and getting caught in isolated downpipes’. Archives of Public Health, 79, 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohail Q. Z., Chu A., Rezai M. R., Donovan L. R., Ko D. T., Tu J. V. (2015) The risk of ischemic heart disease and stroke among immigrant populations: a systematic review. The Canadian Journal of Cardiology, 31, 1160–1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steel Z., Momartin S., Silove D., Coello M., Aroche J., Tay K. W. (2011) Two year psychosocial and mental health outcomes for refugees subjected to restrictive or supportive immigration policies. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 72, 1149–1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart M., Reid G., Buckles L., Edgar W., Mangham C., Tilley N. (1999) A Study of Resiliency in Communities. Health Canada, Office of Alcohol, Drug and Dependency Issues, Ottawa, ON. [Google Scholar]

- Stirbu I., Kunst A. E., Bos V., Mackenbach J. P. (2006) Differences in avoidable mortality between migrants and the native Dutch in the Netherlands. BMC Public Health, 6, 78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres S., Spitzer D. L., Labonté R., Amaratunga C., Andrew C. (2013) Community health workers in Canada: innovative approaches to health promotion outreach and community development among immigrant and refugee populations. The Journal of Ambulatory Care Management, 36, 305–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein N. (1992) Powerlessness, empowerment, and health: implications for health promotion programs. American Journal of Health Promotion: Ajhp, 6, 197–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein N. (2006) What is the Evidence on Effectiveness of Empowerment to Improve Health? WHO Regional Office for Europe (Health Evidence Network Report), Copenhagen. http://www.euro.who.int/en/data-and-evidence/evidence-informed-policy-making/publications/pre2009/what-is-the-evidence-on-effectiveness-of-empowerment-to-improve-health (last accessed 11 June 2020).

- Wallerstein N., Oetzel J., Duran B., Tafoya G., Belone L., Rae R. (2008) What predicts outcomes in CBPR. In Minkler M., Wallerstein N. (eds) Community-Based Participatory Research for Health: From Process to Outcomes. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, pp. 371−–392.. [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein N. (2017) CBPR Research for Improved Health Study Team. July 2011. Focus Group Interview Guide, Research for Improved Health: A National Study of Community-Academic Partnerships. Qualitative Study Instrument, University of New Mexico Center for Participatory Research. From: NARCH V (Indian Health Service/NIGMS/NIH U261HS300293 2009-2013) Reconstructed 2017. https://cpr.unm.edu/research-projects/cbpr-project/index.html (last accessed 11 June 2020).

- Ward M., Schulz A. J., Israel B. A., Rice K., Martenies S. E., Markarian E. (2018) A conceptual framework for evaluating health equity promotion within community-based participatory research partnerships. Evaluation and Program Planning, 70, 25–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenger E. (1998) Communities of Practice. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. [Google Scholar]

- WHO (1986). Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion. Adopted at an international conference on health promotion, The Move Towards a New Public Health, Ottawa, 17−21 November. http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/129532/Ottawa_Charter.pdf

- WHO. (1997) The Jakarta Declaration on Leading Health Promotion into the 21st Century. Fourth International Conference on Health Promotion, Jakarta. https://www.who.int/healthpromotion/conferences/previous/jakarta/declaration/en/

- WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health, World Health Organisation. (2008) Closing the Gap in a Generation: Health Equity through Action on the Social Determinants of Health: Commission on Social Determinants of Health Final Report. World Health Organization, Geneva. [Google Scholar]

- WHO Regional Office for Europe. (2013) Review of Social Determinants and the Health Divide in the WHO European Region: Final Report, Copenhagen.

- WHO Regional Office for Europe. (2017) Engagement and Participation for Health Equity. Reducing Health Inequities: Perspectives for Policymakers and Planners.

- WHO Regional Office for Europe. (2018) What Quantitative and Qualitative Methods Have Been Developed to Measure Community Empowerment at a National Level? Health Evidence Network Synthesis Report No. 59. [PubMed]

- Wiggins N., Johnson D., Avila M., Farquhar S. A., Michael Y. L., Rios T. et al. (2009) Using popular education for community empowerment: perspectives of CommunityHealth Workers in the Poder es Salud/Power for Health program. Critical Public Health, 19, 11–22. [Google Scholar]

- Wiggins N. (2012) Popular education for health promotion and community empowerment: a review of the literature. Health Promotion International, 27, 356–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiggins N., Hughes A., Rios-Campos T., Rodriguez A., Potter C. (2014) La Palabra es Salud (The Word is Health): combining mixed methods and CBPR to understand the comparative effectiveness of popular and conventional education. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 8, 278–298. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman M. A. (1995) Psychological empowerment: issues and illustrations. American Journal of Community Psychology, 23, 581–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]