Key Points

Question

What are the 10-year outcomes and costs of off-pump (“beating heart”) vs on-pump coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG)?

Findings

This randomized clinical trial of 2203 veterans found that, compared with patients who underwent on-pump CABG, those who underwent off-pump CABG had reduced time to the 10-year composite (defined as all-cause death or repeated revascularization). Across all other primary and secondary end points, no advantages of off-pump CABG were identified.

Meaning

For veterans, in the absence of contraindications, the traditional on-pump CABG technique should not be supplanted by an off-pump CABG approach.

Abstract

Importance

The long-term benefits of off-pump (“beating heart”) vs on-pump coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) remain controversial.

Objective

To evaluate the 10-year outcomes and costs of off-pump vs on-pump CABG in the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Randomized On/Off Bypass (ROOBY) trial.

Design, Setting, and Participants

From February 27, 2002, to May 7, 2007, 2203 veterans in the ROOBY trial were randomly assigned to off-pump or on-pump CABG procedures at 18 participating VA medical centers. Per protocol, the veterans were observed for 10 years; the 10-year, post-CABG clinical outcomes and costs were assessed via centralized abstraction of electronic medical records combined with merges to VA and non-VA databases. With the use of an intention-to-treat approach, analyses were performed from May 7, 2017, to December 9, 2021.

Interventions

On-pump and off-pump CABG procedures.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The 10-year coprimary end points included all-cause death and a composite end point identifying patients who had died or had undergone subsequent revascularization (ie, percutaneous coronary intervention [PCI] or repeated CABG); these 2 end points were measured dichotomously and as time-to-event variables (ie, time to death and time to composite end points). Secondary 10-year end points included PCIs, repeated CABG procedures, changes in cardiac symptoms, and 2018-adjusted VA estimated costs. Changes from baseline to 10 years in post-CABG, clinically relevant cardiac symptoms were evaluated for New York Heart Association functional class, Canadian Cardiovascular Society angina class, and atrial fibrillation. Outcome differences were adjudicated by an end points committee. Given that pre-CABG risks were balanced, the protocol-driven primary and secondary hypotheses directly compared 10-year treatment-related effects.

Results

A total of 1104 patients (1097 men [99.4%]; mean [SD] age, 63.0 [8.5] years) were enrolled in the off-pump group, and 1099 patients (1092 men [99.5%]; mean [SD] age, 62.5 [8.5] years) were enrolled in the on-pump group. The 10-year death rates were 34.2% (n = 378) for the off-pump group and 31.1% (n = 342) for the on-pump group (relative risk, 1.05; 95% CI, 0.99-1.11; P = .12). The median time to composite end point for the off-pump group (4.6 years; IQR, 1.4-7.5 years) was approximately 4.3 months shorter than that for the on-pump group (5.0 years; IQR, 1.8-7.9 years; P = .03). No significant 10-year treatment-related differences were documented for any other primary or secondary end points. After the removal of conversions, sensitivity analyses reconfirmed these findings.

Conclusions and Relevance

No off-pump CABG advantages were found for 10-year death or revascularization end points; the time to composite end point was lower in the off-pump group than in the on-pump group. For veterans, in the absence of on-pump contraindications, a case cannot be made for supplanting the traditional on-pump CABG technique with an off-pump approach.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01924442

This randomized clinical trial evaluates the 10-year outcomes and costs of off-pump vs on-pump coronary artery bypass grafting in the Department of Veterans Affairs Randomized On/Off-Bypass trial.

Introduction

During the 20 years since off-pump coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) gained widespread renewed interest,1,2,3 the benefits and risks of an off-pump vs on-pump approach have been debated. Proponents of off-pump CABG cite potentially lower rates of post–cardiopulmonary bypass complications, such as neurologic and kidney sequelae.4,5 Advocates of on-pump CABG raise concerns of potentially lower rates of completeness and effectiveness of revascularization as well as higher off-pump reintervention rates.6,7

Across off-pump vs on-pump CABG clinical trials comparing 1-year or 5-year outcomes, the advantages of an off-pump approach have not been convincing. The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Randomized On/Off Bypass (ROOBY) trial’s 1-year outcomes of 2203 veterans randomly assigned to off-pump (n = 1104) vs on-pump (n = 1099) CABG procedures documented a higher composite rate of death, myocardial infarction, and repeated revascularization among those who underwent off-pump CABG.8 This difference, which persisted at 5 years, was largely driven at the later time point by a higher mortality rate among those in the off-pump group.9 The ROOBY trial’s findings were not universal, however; a meta-analysis of trials with intermediate follow-up, including results from the CABG Off or On Pump Revascularization Study (CORONARY),10,11 suggested that there may be a slight survival advantage among those who underwent on-pump CABG.12 To further investigate whether there may be long-term differences, the Department of Veterans Affairs separately funded the ROOBY Follow-up Study (ROOBY-FS) to specifically compare 10-year clinical trial outcomes and post-CABG costs between off-pump and on-pump treatments.

Methods

Design and Population

The ROOBY-FS design and 5-year outcomes were previously reported (trial protocol in Supplement 1).8,9 For nonemergency CABG procedures, the VA ROOBY trial was a 2-group, parallel trial (1:1 ratio) designed to evaluate the superiority of the off-pump (“beating heart”) approach compared with the traditional on-pump surgical approach (ie, using a heart-lung machine for cardiopulmonary bypass). Per the ROOBY-FS protocol, the 10-year clinical outcomes and costs were monitored for veterans historically randomly assigned to undergo off-pump (n = 1104) vs on-pump (n = 1099) CABG procedures at 18 VA medical centers from February 27, 2002, to May 7, 2007. Designed as a phase 4 trial, the ROOBY-FS had null hypotheses stating that there would be no differences found between off-pump and on-pump treatment-related effects on veterans’ clinical outcomes or post-CABG costs for up to 10 years after their index CABG procedure. With centralized follow-up and analysis coordinated jointly by the Perry Point Cooperative Studies Program Coordinating Center (CSPCC) and the VA Palo Alto Health Economic Resource Center teams, ROOBY-FS institutional review board approvals (including waiver of informed consent and waiver of Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act authorization requirements) were obtained from the Northport VA Medical Center institutional review board (Northport, New York), the Colorado Multiple institutional review board for the Rocky Mountain Regional VA Medical Center (Aurora), and Stanford University (Palo Alto, California). This study was designed in accordance with the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) reporting guidelines.

Clinical Outcomes

Evaluated as both dichotomous and time-to-event end points, the 10-year ROOBY-FS primary outcomes included all-cause death and a composite end point based on either all-cause death or repeated revascularization occurring. Repeated revascularization was defined as a percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or a repeated CABG procedure. Secondary 10-year clinical outcomes included the composite end point’s subcomponents (ie, PCI and repeated CABG) and post-CABG cardiac symptom changes using the New York Heart Association (NYHA) and the Canadian Cardiovascular Society (CCS) assessment tools. Comparing baseline class level with 10-year follow-up class level, the CCS and NYHA class changes were evaluated as (1) no change in symptoms, (2) improvement of symptoms, and (3) worsening of symptoms. If a 10-year revascularization procedure was performed, these patients were assumed to have worsened 10-year cardiac symptoms. In addition, 10-year atrial fibrillation rates were compared between patients who had developed new postoperative atrial fibrillation (POAF) and those who did not.

To identify ROOBY-FS 10-year clinical outcomes, centralized medical record abstractions were performed by dedicated VA Perry Point CSPCC nurse coordinators accessing veterans’ electronic medical records. The VA (eg, the VA Corporate Data Warehouse) and non-VA databases (eg, Medicare Part A and B files) were searched to identify clinical outcomes using billing codes including Current Procedural Terminology, International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision, and diagnostic related group codes. Both 10-year death rates and 10-year time-to-death days were identified using a combination of VA and non-VA death registries; the accuracy of this combined approach has been independently reported as approximately 99.7%.13,14,15

Because veterans may have received non-VA care (eg, through Medicare Advantage or other commercial insurance), the loss-to-follow-up rates for surviving veterans were assessed within 180 days and 365 days from the date of their postrandomization 10-year anniversary. Of the 1483 ten-year survivors, 1.8% (26 patients; 15 on-pump and 11 off-pump) were lost to follow-up within 180 days of their 10-year postrandomization anniversary and 1.5% (22 patients; 12 on-pump and 10 off-pump) were lost to follow-up within 365 days of their 10-year postrandomization anniversary. With no treatment-related differences in loss to follow-up, the completeness rate for the primary composite outcome (either death or a subsequent revascularization procedure) was estimated at approximately 98.5% (1461 of 1483). For event-related differences found for death and repeated revascularization, the end points committee adjudicated all initial discrepancies identified between medical record review and database findings.15

Among 10-year survivors (n = 1483), the cardiac symptom changes from baseline to 10-year follow-up were evaluated for all patients based on their latest electronic medical records. For 10-year angina symptoms, 5.0% of survivors (74 of 1483) had insufficient data to assign a 10-year CCS angina class. Details to support assessments for NYHA functional class changes from baseline to 10-year follow-up were missing for 4.7% of survivors (69 of 1483). Similarly, 4.7% of 10-year survivors (69 of 1483) were missing electronic medical record details required to determine the presence of chronic, persistent atrial fibrillation; the latest electrocardiogram at the last follow-up was used for verification. Patients with missing data were removed from these 10-year secondary outcome analyses, as appropriate.

Cost Estimates

The 10-year CABG-related costs were a secondary outcome estimated for off-pump vs on-pump treatments. Per the ROOBY trial’s cost evaluation methods published previously,16 we extracted the patients’ post-CABG activity-based cost estimates from VA Managerial Cost Accounting data, VA purchased care files, and Medicare Fee-for-Service (Part A and B) files.17 For these latter 2 databases, estimated costs were based on payments recorded. The 10-year costs aggregated the VA and non-VA costs from the date of index CABG procedure to the 10-year follow-up anniversary. For patients with hospital stays bridging 2 calendar-year periods, their calendar-year–specific costs were allocated as previously published using the calendar-year–specific proportion of their hospital stay.16,18 For equitable comparisons, costs were standardized to 2018 US dollars using the general consumer price index.

Statistical Analysis

With the use of an intention-to-treat approach, statistical analyses were performed from May 7, 2017, to December 9, 2021. Because patients’ baseline risk factors were balanced, the χ2 test or the Fisher exact test was used to compared dichotomous end points across treatment groups. After the index CABG, we compared treatment-related survival curves using the log-rank test. Given the inherent nature of the primary end points, both relative risk (ie, for dichotomous end points, including all-cause death and the composite end point) and hazard ratios (ie, for survival) were calculated using the on-pump group as the reference population. For 3 randomized patients who did not undergo CABG, we used the randomization date in lieu of the surgery date. To evaluate for statistical significance when testing this study’s superiority hypotheses, 2-tailed statistical tests used P ≤ .05 for primary outcome comparisons and P ≤ .01 for secondary outcome comparisons.

After comparing different cost modeling approaches (ie, generalized estimating equations, linear, and semi-log models), there were no major differences; thus, the cost analyses used a generalized estimating equations model with a log link and a gamma distribution. These cost models extended our prior work, controlling for variations across participating VA medical centers in their estimated costs, adjusting these costs’ SEs for repeated measures over time.18 The estimated costs reported were similar, independent of the model choice.

Given that intraoperative conversions were more common in the off-pump group,19 sensitivity analyses reanalyzed all 10-year primary and secondary study end points without conversions; our final findings were confirmed as robust. Protocol-driven, preestablished high-risk subgroup (eg, patients with diabetes) analyses were performed. Last, a sensitivity analysis evaluated the effect of surgeons’ prestudy off-pump caseload experience (ie, ≤50 vs >50 cases).

Results

Patient Characteristics

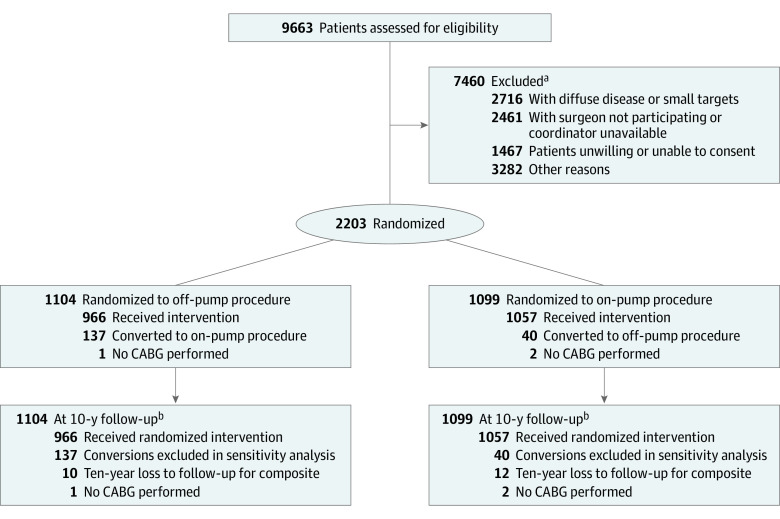

A total of 1104 patients (1097 men [99.4%]; mean [SD] age, 63.0 [8.5] years) were enrolled in the off-pump group, and a total of 1099 patients (1092 men [99.5%]; mean [SD] age, 62.5 [8.5] years) were enrolled in the on-pump group. Patient screening, enrollment, randomization, and follow-up details for the 2203 ROOBY-FS patients are provided in Figure 1. Per prior publications, patient baseline characteristics were balanced between the 2 randomized groups with respect to mean age; group incidence of diabetes, stroke, and other cardiovascular-related comorbidities; severity of coronary artery disease; and 30-day estimated mortality risk (Table 1).8,9

Figure 1. Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials Flow Diagram (N = 2203).

CABG indicates coronary artery bypass grafting.

aMore than 1 reason for exclusion was permitted.

bThere was no loss to follow-up for the coprimary end point of all-cause death.

Table 1. Characteristics of Patientsa.

| Characteristic | Patients, No./total No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Off-pump group (n = 1104) | On-pump group (n = 1099) | |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 63.0 (8.5) | 62.5 (8.5) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 1097/1104 (99.4) | 1092 (99.4) |

| Female | 7 (0.6) | 6 (0.5) |

| Unknown | 0 | 1 (0.1) |

| Race and ethnicity | ||

| Black | 77/1104 (7.0) | 93/1098 (8.5) |

| Hispanic | 71/1104 (6.4) | 52/1098 (4.7) |

| White | 931/1104 (84.3) | 926/1098 (84.3) |

| Other | 25/1104 (2.3) | 27/1098 (2.5) |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 628/1102 (57.0) | 642/1096 (58.6) |

| Divorced or separated | 328/1102 (29.8) | 308/1096 (28.1) |

| Other | 146/1102 (13.2) | 146/1096 (13.3) |

| Urgent status | 179/1104 (16.2) | 156/1099 (14.2) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 220/1104 (19.9) | 238/1099 (21.7) |

| Creatinine level >1.5 mg/dL | 94/1104 (8.5) | 79/1099 (7.2) |

| Stroke | 82/1104 (7.4) | 88/1099 (8.0) |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 179/1104 (16.2) | 163/1099 (14.8) |

| Diabetes | 470/1104 (42.6) | 491/1099 (44.7) |

| Hypertension | 948/1104 (85.9) | 952/1099 (86.6) |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction | ||

| <35% | 61/1065 (5.7) | 61/1062 (5.7) |

| 35%-44% | 122/1065 (11.5) | 132/1062 (12.4) |

| 45%-54% | 249/1065 (23.4) | 253/1062 (23.8) |

| >54% | 633/1065 (59.4) | 616/1062 (58.0) |

| History of depression | 146/792 (18.4) | 120/785 (15.3) |

| History of atrial fibrillation | 52/1104 (4.7) | 41/1099 (3.7) |

| Estimated 30-d mortality risk, mean (SD), %b | 1.9 (1.8) | 1.8 (1.8) |

SI conversion factor: To convert creatinine to micromoles per liter, multiply by 88.4.

No differences in baseline characteristics between treatment groups were found at P ≤ .05.

Calculated risk based on the Department of Veterans Affairs Surgical Quality Improvement Program.

Primary Outcomes

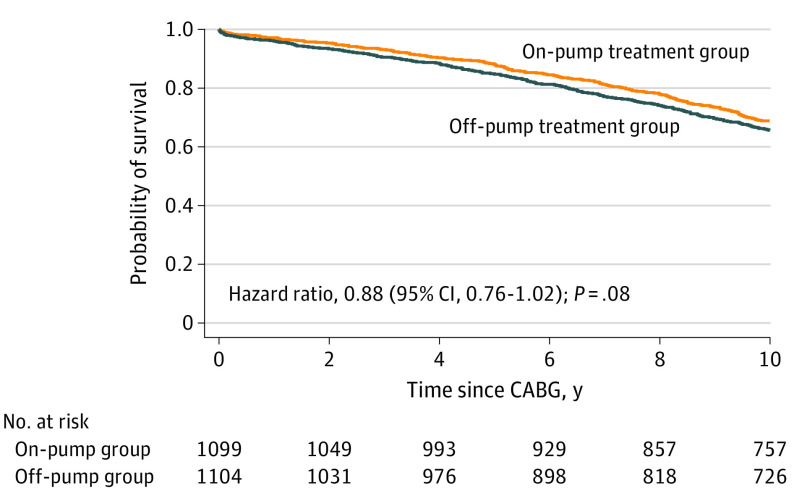

Ten-year all-cause death rates (Table 2) were comparable between the off-pump (378 [34.2%]) and on-pump (342 [31.1%]) patient subgroups, with an absolute 3.12% difference (relative risk, 1.05; 95% CI, 0.99-1.11; P = .12). Ten-year Kaplan-Meier curves compared the time to death after randomization for both groups. No difference was found between the mean (SD) time to death for the off-pump group (5.3 [3.0] years) and the on-pump group (5.7 [2.9] years) (Figure 2; log-rank test; hazard ratio, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.76-1.02; P = .08). The median time to death in the off-pump group was 5.6 years (IQR, 2.8-8.0 years), whereas the median time to death in the on-pump group was 6.1 years (IQR, 3.3-8.3 years). Treatment-specific times to events are reported in eTable 1 in Supplement 2.

Table 2. Ten-Year Assessments, According to Treatment Group.

| Outcome | Patients, No. (%) | Absolute difference, % | Relative risk | P valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Off-pump group (n = 1104) | On-pump group (n = 1099) | ||||

| Primary outcomes at 10 y | |||||

| Death | 378 (34.2) | 342 (31.1) | 3.12 (−0.80 to 7.03)b | 1.05 (0.99 to 1.11)b | .12 |

| Repeated revascularization or death | 548 (49.6) | 501 (45.6) | 4.05 (−0.12 to 8.22)b | 1.09 (1.00 to 1.19)b | .06 |

| Secondary outcomes at 10 y | |||||

| Repeated revascularization | 227 (20.6) | 210 (19.1) | 1.45 (−1.88 to 4.78)c | 1.02 (0.98 to 1.06)c | .39 |

| Post-CABG PCI | 210 (19.0) | 201 (18.3) | 0.73 (−2.52 to 3.99)c | 1.04 (0.87 to 1.24)c | .66 |

| Repeated CABG | 25 (2.3) | 13 (1.2) | 1.08 (−0.00 to 2.17)c | 1.91 (0.98 to 3.72)c | .05 |

Abbreviations: CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

The P values are equivalent for both absolute differences and the relative risks reported.

The 95% CIs were reported for treatment group differences.

With 99% CI.

Figure 2. Ten-Year Post–Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting (CABG) Survival by Treatment Group (N = 2203).

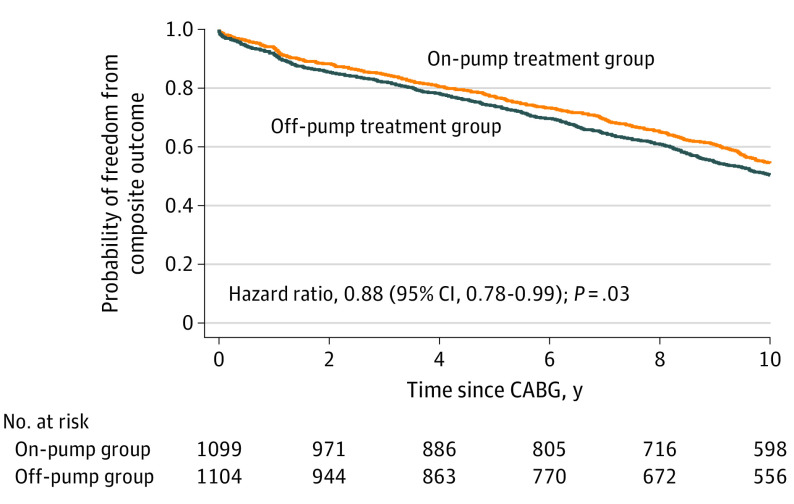

The off-pump composite end point rate was 49.6% (n = 548) in the off-pump group vs 45.6% (n = 501) in the on-pump group (relative risk, 1.09; 95% CI, 1.00-1.19; P = .06) (Table 2). The mean (SD) time to first composite event was 4.6 (3.2) years in the off-pump group and 4.9 (3.2) years in the on-pump group, representing a mean difference of approximately 3.3 months. The median time to the composite end point was 4.6 years (IQR, 1.4-7.5 years) in the off-pump group and 5.0 years (IQR, 1.8-7.9 years) in the on-pump group, representing a median on-pump advantage of approximately 4.3 months for the freedom from death or repeated revascularization end point. Ten-year Kaplan-Meier curves demonstrated that, for the coprimary time to composite outcome, this treatment group difference was significant (Figure 3; log-rank test; hazard ratio, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.78-0.99; P = .03).

Figure 3. Ten-Year Post–Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting (CABG) Freedom From Death or Repeated Revascularization by Treatment Group (N = 2203).

Secondary Outcomes

None of the secondary outcomes met the prespecified P value threshold of .01 or less for statistical significance. The 10-year repeated revascularization rate was comparable between the 2 groups (off-pump group, 227 [20.6%]; on-pump group, 210 [19.1%]; P = .39) (Table 2). Post-CABG PCI rates were 19.0% for the off-pump group (n = 210) and 18.3% for the on-pump group (n = 201) (P = .66). The 10-year repeated CABG rate was 2.3% for the off-pump group (n = 25) and 1.2% for the on-pump group (n = 13) (P = .05).

Among 10-year survivors, 487 of 696 patients (70.0%) in the off-pump group and 509 of 713 patents (71.4%) in the on-pump group sustained improvements from their baseline angina CCS class (P = .77) (eTable 2 in Supplement 2). With the evaluation of heart failure symptoms, the 10-year NYHA functional class improvement rate was 62.6% (435 of 695) for the off-pump group vs 62.0% (446 of 719) for the on-pump group (P = .85).

Of the 551 patients with POAF, late atrial fibrillation rates for 10-year survivors (338 of 551) were not different between the on-pump and off-pump groups (35 of 166 [21.1%] vs 29 of 172 [16.9%]; P = .32) (eTable 2 in Supplement 2). For survivors without POAF, the 10-year atrial fibrillation rate was not different between the on-pump and off-pump groups (36 of 540 [6.7%] vs 25 of 508 [4.9%]; P = .23). Ten-year late atrial fibrillation rates were higher among patients with POAF than among those without POAF (64 of 338 [18.9%] vs 61 of 1048 [5.8%]; P < .001); this finding was consistent for the on-pump group (POAF, 21.1% [35 of 166] vs non-POAF, 6.7% [36 of 540]; P < .001) and the off-pump group (POAF, 16.9% [29 of 172] vs non-POAF, 4.9% [25 of 508]; P < .001).

Ten-year CABG annual postoperative costs, adjusted to 2018 dollars, are shown in eFigure 1 in Supplement 2. These costs trended similarly for both the off-pump and on-pump CABG groups. Costs were highest in the first year, which included the initial post-CABG hospitalization costs. Costs during years 2 through 10 were substantially lower than those during the first year, at a mean of approximately $20 000 per person for year 2. Between year 2 and year 10, these mean costs slowly increased, but there was no significant difference between the on-pump and off-pump groups. Details for the billing codes used to extract data for the cost comparison and the annual comparison of treatment-related costs have been provided in eTables 3 and 4 in Supplement 2.

Sensitivity Analyses

Analysis of primary and secondary clinical end points for nonconverted patients (ie, patients who received only the originally randomized treatment) showed 10-year mortality rates of 33.1% (320 of 967) for the off-pump group vs 29.8% (316 of 1059) for the on-pump group (P = .12) (eTable 5 in Supplement 2). For nonconverted patients, survival rates were not different between the off-pump group and the on-pump group (hazard ratio, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.75-1.02; P = .09) (eFigure 2 in Supplement 2). For nonconverted patients, the 10-year composite outcome rates were 49.0% (474 of 967) for the off-pump group and 44.6% (472 of 1059) for the on-pump group (P = .05) (eTable 5 in Supplement 2). For nonconverted patients, event-free (ie, PCI or repeated CABG) survival was again lower for the off-pump group compared with the on-pump group (hazard ratio, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.77-0.99; P = .03) (eFigure 3 in Supplement 2). Furthermore, no treatment-related differences were found for any high-risk patient subpopulations. Sensitivity analyses confirmed that surgeons’ prestudy caseload of off-pump CABG procedures did not influence this study’s findings (eTable 6 in Supplement 2).

Discussion

This large-scale VA trial found that the median time to 10-year composite end point was reduced for the off-pump group by approximately 4.3 months. There was no advantage to the off-pump CABG procedure identified across any 10-year secondary outcomes studied or post-CABG costs. Removing converted patients and evaluating for surgeons’ prestudy caseload experience with off-pump CABG procedures, sensitivity analyses documented these findings to be robust.

During the past decade, the debate between off-pump and on-pump CABG has persisted. In general, multicenter studies have documented either no treatment difference or a clinically subtle but statistically significant advantage for on-pump revascularization.20,21,22 Overall, the lack of any advantage to off-pump CABG appears to be a robust finding, even after accounting for surgeons’ prestudy experience with off-pump CABG procedures.23,24 Among high-risk patients, no additional benefit to off-pump CABG procedures was uncovered in this investigation. In addition, among surgeons in the ROOBY trial, higher prestudy off-pump CABG caseload experience did not alter these 10-year findings. These 2 operative techniques may be considered complementary, as part of a cardiac surgeon’s armamentarium. In certain situations (ie, a patient with a heavily calcified aorta), an off-pump approach by an experienced surgeon may be the preferred—if not the only potentially viable—option available for surgical revascularization.

Our ROOBY-FS report builds on prior publications by providing, to our knowledge, the first multicenter, randomized, controlled off-pump vs on-pump clinical trial reporting a comprehensive set of 10-year end points. These results concur with the 2015 consensus statement by the International Society for Minimally Invasive Cardiothoracic Surgery that off-pump CABG procedures may be associated with an increased long-term risk of reintervention and death.25

Beyond the traditional end points of death and repeated revascularization, the 10-year symptomatic benefit among patients who underwent CABG was not influenced by the treatment approach. With no off-pump vs on-pump differences documented, 10-year CCS anginal class improvements from baseline occurred in approximately 70% of both treatment groups; similarly, 10-year NYHA class improvements in heart failure symptoms from baseline occurred in approximately 62% of patients.

Historically, POAF has been associated with higher late atrial fibrillation rates.26,27 As the first multicenter, controlled clinical trial comparing long-term recurrent atrial fibrillation rates among patients who underwent off-pump vs on-pump CABG, the ROOBY trial found no difference between groups.28 With no treatment-related difference, the recurrent 10-year atrial fibrillation rate was approximately 20% for 10-year POAF survivors; this 10-year rate of recurrent atrial fibrillation was approximately 3-fold higher than that observed for 10-year survivors without POAF.

Despite pressure from health care insurers, program administrators, and policy makers to maximize value, our findings showed similar health care costs between the 2 treatment groups; thus, costs do not provide data-driven guidance when deciding between on-pump or off-pump procedures. As previously reported, the ROOBY 1-year cost analyses identified that an off-pump approach was initially more expensive than an on-pump approach; however, after excluding conversions, there were no differences found in 1-year treatment-related costs.17 As in other large-scale trials conducted during a similar time frame, no cost differences were seen for the current 10-year follow-up comparison of off-pump and on-pump treatment.11,18,29 Thus, minimizing post-CABG perioperative complications and postdischarge 30-day readmissions may have a greater effect on long-term cost reductions than differential selection of the off-pump vs on-pump approach.30,31

Limitations

This VA-based, 10-year follow-up study has several important limitations. The enrolled veteran population was predominately male, presenting with multiple, complex comorbidities; thus, these results may not be generalizable to women or nonveteran patient populations with different baseline risk characteristics. Historically, VA research reports have documented inherent limitations with using administrative databases to assess myocardial infarction events.32 Given that no 1-year or 5-year myocardial infarction treatment-related differences had been found, 10-year myocardial infarction rates were not further assessed. Because death-related clinical details were not available, 10-year cause of death could not be reliably determined.

Conclusions

This final report of ROOBY-FS represents, to our knowledge, the largest US-based, multicenter, randomized, clinical, single-blinded trial comparing off-pump vs on-pump CABG procedures, with nearly 100% complete 10-year primary and secondary end point follow-ups. ROOBY-FS documented slightly shorter revascularization-free survival among patients in the off-pump group. For most patients undergoing CABG who present as a viable candidate for either revascularization option, moreover, no tangible long-term advantages of the off-pump CABG procedure were identified compared with the traditional on-pump strategy.

Trial Protocol

eTable 1. Ten-Year Primary End Points: Post-CABG Time-to-Event (Years)

eTable 2. Ten-Year Cardiac Symptoms, According to Treatment Group

eTable 3. CSP 517 Cost Analyses Revascularization-related Codes

eTable 4. Detailed Cost Data (see Figure 3)

eTable 5. Ten-Year Assessments, According to Treatment Group among Nonconverted Patients (n=2026)

eTable 6. Ten-Year Assessments Stratified by Participating Surgeon’s Prestudy Total Off-Pump Caseload Experience (>50 vs ≤50 Cases)

eFigure 1. Ten-Year Adjusted Mean Costs (2018 dollars) by Treatment Arm (n=2203)

eFigure 2. Ten-Year Post-CABG Survival by Treatment Group (Nonconverted Patients; n = 2026)

eFigure 3. Ten-Year Post-CABG Freedom From Death or Repeat Revascularization by Treatment Group (Nonconverted Patients; n = 2026)

eAppendix. ROOBY Trial’s Participating Centers and Ten-Year Committees

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Hirose H, Amano A, Yoshida S, Takahashi A, Nagano N. Off-pump coronary artery bypass: early results. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2000;6(2):110-118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mack MJ, Pfister A, Bachand D, et al. Comparison of coronary bypass surgery with and without cardiopulmonary bypass in patients with multivessel disease. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2004;127(1):167-173. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2003.08.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Omeroğlu SN, Kirali K, Güler M, et al. Midterm angiographic assessment of coronary artery bypass grafting without cardiopulmonary bypass. Ann Thorac Surg. 2000;70(3):844-849. doi: 10.1016/S0003-4975(00)01567-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dominici C, Salsano A, Nenna A, et al. Neurological outcomes after on-pump vs off-pump CABG in patients with cerebrovascular disease. J Card Surg. 2019;34(10):941-947. doi: 10.1111/jocs.14158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abu-Omar Y, Taghavi FJ, Navaratnarajah M, et al. The impact of off-pump coronary artery bypass surgery on postoperative renal function. Perfusion. 2012;27(2):127-131. doi: 10.1177/0267659111429890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hattler B, Messenger JC, Shroyer AL, et al. ; Veterans Affairs Randomized On/Off Bypass (ROOBY) Study Group . Off-pump coronary artery bypass surgery is associated with worse arterial and saphenous vein graft patency and less effective revascularization: results from the Veterans Affairs Randomized On/Off Bypass (ROOBY) trial. Circulation. 2012;125(23):2827-2835. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.069260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thakur U, Nerlekar N, Muthalaly RG, et al. Off- vs. on-pump coronary artery bypass grafting long-term survival is driven by incompleteness of revascularisation. Heart Lung Circ. 2020;29(1):149-155. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2018.11.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shroyer AL, Grover FL, Hattler B, et al. ; Veterans Affairs Randomized On/Off Bypass (ROOBY) Study Group . On-pump versus off-pump coronary-artery bypass surgery. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(19):1827-1837. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0902905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shroyer AL, Hattler B, Wagner TH, et al. ; Veterans Affairs ROOBY-FS Group . Five-year outcomes after on-pump and off-pump coronary-artery bypass. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(7):623-632. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1614341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lamy A, Devereaux PJ, Prabhakaran D, et al. ; CORONARY Investigators . Off-pump or on-pump coronary-artery bypass grafting at 30 days. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(16):1489-1497. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lamy A, Devereaux PJ, Prabhakaran D, et al. ; CORONARY Investigators . Five-year outcomes after off-pump or on-pump coronary-artery bypass grafting. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(24):2359-2368. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1601564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smart NA, Dieberg G, King N. Long-term outcomes of on- versus off-pump coronary artery bypass grafting. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(9):983-991. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.12.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cowper DC, Kubal JD, Maynard C, Hynes DM. A primer and comparative review of major US mortality databases. Ann Epidemiol. 2002;12(7):462-468. doi: 10.1016/S1047-2797(01)00285-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sohn MW, Arnold N, Maynard C, Hynes DM. Accuracy and completeness of mortality data in the Department of Veterans Affairs. Popul Health Metr. 2006;4:2. doi: 10.1186/1478-7954-4-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Quin JA, Hattler B, Shroyer ALW, et al. ; Department of Veteran Affairs (CSP#517-FS) ROOBY Follow-up Study’s Endpoints Committee . Concordance between administrative data and clinical review for mortality in the randomized on/off bypass follow-up study (ROOBY-FS). J Card Surg. 2017;32(12):751-756. doi: 10.1111/jocs.13379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wagner TH, Hattler B, Bishawi M, et al. ; VA #517 Randomized On/Off Bypass (ROOBY) Study Group . On-pump versus off-pump coronary artery bypass surgery: cost-effectiveness analysis alongside a multisite trial. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;96(3):770-777. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.04.074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barnett PG. An improved set of standards for finding cost for cost-effectiveness analysis. Med Care. 2009;47(7)(suppl 1):S82-S88. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31819e1f3f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wagner TH, Hattler B, Bakaeen FG, et al. ; VA #517 Randomized On/Off Bypass (ROOBY) Study Group . Costs five years after off-pump or on-pump coronary artery bypass surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2019;107(1):99-105. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2018.07.075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Novitzky D, Baltz JH, Hattler B, et al. Outcomes after conversion in the Veterans Affairs Randomized On versus Off Bypass trial. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;92(6):2147-2154. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2011.05.122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taggart DP, Gaudino MF, Gerry S, et al. ; Arterial Revascularization Trial Investigators . Ten-year outcomes after off-pump versus on-pump coronary artery bypass grafting: insights from the Arterial Revascularization Trial. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2021;162(2):591-599.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2020.02.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Deutsch MA, Zittermann A, Renner A, et al. Risk-adjusted analysis of long-term outcomes after on- versus off-pump coronary artery bypass grafting. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2021;33(6):857-865. doi: 10.1093/icvts/ivab179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim JB, Yun SC, Lim JW, et al. Long-term survival following coronary artery bypass grafting: off-pump versus on-pump strategies. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(21):2280-2288. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.02.584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chikwe J, Lee T, Itagaki S, Adams DH, Egorova NN. Long-term outcomes after off-pump versus on-pump coronary artery bypass grafting by experienced surgeons. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72(13):1478-1486. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.07.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Squiers JJ, Schaffer JM, Banwait JK, Ryan WH, Mack MJ, DiMaio JM. Long-term survival after on-pump and off-pump coronary artery bypass grafting. Ann Thorac Surg. Published online August 17, 2021. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2021.07.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Puskas JD, Martin J, Cheng DCH, et al. ISMICS consensus conference and statements of randomized controlled trials of off-pump versus conventional coronary artery bypass surgery. Innovations (Phila). 2015;10(4):219-229. doi: 10.1097/imi.0000000000000184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee SH, Kang DR, Uhm JS, et al. New-onset atrial fibrillation predicts long-term newly developed atrial fibrillation after coronary artery bypass graft. Am Heart J. 2014;167(4):593-600.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2013.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Park YM, Cha MS, Park CH, et al. Newly developed post-operative atrial fibrillation is associated with an increased risk of late recurrence of atrial fibrillation in patients who underwent open heart surgery: long-term follow up. Cardiol J. 2017;24(6):633-641. doi: 10.5603/CJ.a2017.0073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Almassi GH, Pecsi SA, Collins JF, Shroyer AL, Zenati MA, Grover FL. Predictors and impact of postoperative atrial fibrillation on patients’ outcomes: a report from the Randomized On Versus Off Bypass Trial. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012;143(1):93-102. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2011.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scudeler TL, Hueb WA, Farkouh ME, et al. Cost-effectiveness of on-pump and off-pump coronary artery bypass grafting for patients with coronary artery disease: results from the MASS III Trial. Int J Cardiol. 2018;273:63-68. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2018.08.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mehaffey JH, Hawkins RB, Byler M, et al. ; Virginia Cardiac Services Quality Initiative . Cost of individual complications following coronary artery bypass grafting. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2018;155(3):875-882.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2017.08.144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shah RM, Zhang Q, Chatterjee S, et al. Incidence, cost, and risk factors for readmission after coronary artery bypass grafting. Ann Thorac Surg. 2019;107(6):1782-1789. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2018.10.077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Best WR, Khuri SF, Phelan M, et al. Identifying patient preoperative risk factors and postoperative adverse events in administrative databases: results from the Department of Veterans Affairs National Surgical Quality Improvement Program. J Am Coll Surg. 2002;194(3):257-266. doi: 10.1016/S1072-7515(01)01183-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

eTable 1. Ten-Year Primary End Points: Post-CABG Time-to-Event (Years)

eTable 2. Ten-Year Cardiac Symptoms, According to Treatment Group

eTable 3. CSP 517 Cost Analyses Revascularization-related Codes

eTable 4. Detailed Cost Data (see Figure 3)

eTable 5. Ten-Year Assessments, According to Treatment Group among Nonconverted Patients (n=2026)

eTable 6. Ten-Year Assessments Stratified by Participating Surgeon’s Prestudy Total Off-Pump Caseload Experience (>50 vs ≤50 Cases)

eFigure 1. Ten-Year Adjusted Mean Costs (2018 dollars) by Treatment Arm (n=2203)

eFigure 2. Ten-Year Post-CABG Survival by Treatment Group (Nonconverted Patients; n = 2026)

eFigure 3. Ten-Year Post-CABG Freedom From Death or Repeat Revascularization by Treatment Group (Nonconverted Patients; n = 2026)

eAppendix. ROOBY Trial’s Participating Centers and Ten-Year Committees

Data Sharing Statement