Abstract

Susceptibility of influenza A viruses to baloxavir can be affected by changes at amino acid residue 38 in the polymerase acidic (PA) protein. Information on replicative fitness of PA-I38-substituted viruses remains sparse. We demonstrated that substitutions I38L/M/S/T not only had a differential effect on baloxavir susceptibility (9- to 116-fold) but also on in vitro replicative fitness. Although I38L conferred undiminished growth, other substitutions led to mild attenuation. In a ferret model, control viruses outcompeted those carrying I38M or I38T substitutions, although their advantage was limited. These findings offer insights into the attributes of baloxavir-resistant viruses needed for informed risk assessment.

Keywords: baloxavir acid, influenza, drug resistance, ferret, polymerase acidic protein

Baloxavir marboxil is a new 1-dose oral influenza antiviral. Its active metabolite, baloxavir acid (baloxavir), potently inhibits the cap-dependent endonuclease activity of polymerase acidic (PA) subunit of viral ribonucleic acid (RNA) polymerase [1]. In clinical trials, baloxavir showed low barrier to resistance emergence [2, 3]. The most common change was observed at residue 38 in the PA enzyme active site where conserved isoleucine (I) is substituted with threonine (T), methionine (M), phenylalanine (F), or serine (S) [3] (Emi Takashita, Written personal communication, July 16, 2019). Changes at PA-38 can also occur spontaneously, albeit at low frequencies [3–5].

Information on replicative fitness of baloxavir-resistant influenza viruses is needed to assess public health risk associated with their potential emergence and spread. Therefore, we wanted to investigate the replicative fitness of PA-I38-substituted viruses using cell cultures and the ferret model. We used an A(H3N2) virus carrying I38M and an A(H1N1)pdm09 virus carrying I38L, which were detected at low frequencies (0.03% and 0.15%, respectively) during premarket surveillance in the United States [4]. In addition, we tested an A(H3N2) virus with I38T, which emerged during virus passage, and 2 A(H1N1)pdm09 viruses carrying either I38T or I38S, which were generated by culturing a wild-type virus in the presence of baloxavir. All PA-I38-substituted viruses and their control counterparts used in this study are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

In Vitro Characterization of Influenza A Viruses Used in This Study

| Predicted Amino Acid Substitution vs Controlaa |

Virus Titer, AUC8-72 Mean ± SE (%Difference)e |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subtype | Virus | PA Proteinb | Other Proteins | Sequence Accessionc EPI_ISL_ | Baloxavir EC50, nM, Mean ± SD (Fold Increase vs Control)d | MDCK | MDCK-SIAT1 |

| H1N1pdm09 | A/Illinois/08/2018 | Control | Control | 315855 | 1.82 ± 0.39 (1) | 364.6 ± 8.5 | 334.8 ± 13.4 |

| I38Tf | HA: K119N | 348120 | 92.00 ± 12.00 (51) | 321.8 ± 15.5 (−12)* | 316.0 ± 4.1 (−6) | ||

| I38Sf | - | 365522 | 94.13 ± 9.82 (52) | 327.8 ± 9.4 (−10)* | 300.5 ± 4.7 (−10) | ||

| A/Illinois/37/2018 | I38L | PA-X: E209G | 315856 | 16.69 ± 6.41 (9) | 382.2 ± 4.3 (+5) | 350.0 ± 6.8 (+5) | |

| H3N2 | A/Louisiana/50/2017 | Control | Control | 315857 | 1.31 ± 0.35 (1) | 342.6 ± 11.8 | 358.5 ± 11.4 |

| A/Louisiana/49/2017 | I38M | - | 315858 | 13.58 ± 2.59 (10) | 317.8 ± 11.6 (−7) | 323.6 ± 7.0 (−10)* | |

| A/Bangladesh/3007/2017g | Control | Control | 340421 | 1.33 ± 0.39 (1) | 212.5 ± 9.8 | 238.8 ± 6.8 | |

| I38T | NA: T71I | 340405 | 153.82 ± 15.90 (116) | 185.0 ± 9.5 (−13) | 218.7 ± 4.6 (−8)* | ||

Abbreviations: AUC8–72, area under the curve for 8–72 hours postinfection; EC50, 50% effective concentration; HA, hemagglutinin; MDCK, Madin-Darby canine kidney cells; NA, neuraminidase; PA, polymerase acidic protein; PA-X, PA-X protein; SD, standard deviation; SE, standard error.

Comparison of the codon-complete genome sequences of a PA-I38-substituted virus and its respective control virus. Only amino acid substitutions are shown.

PA and PA-X proteins share the same amino acid at residue 38; only additional changes in PA-X are shown in Table 1.

Genome sequences deposited to Global Initiative on Sharing All Influenza Data ([GISAID] https://www.gisaid.org/); PA-I38-substituted viruses have 1–4 silent nucleotide changes compared with the genomes of their respective control viruses.

Baloxavir EC50 results are shown as mean ± SD of at least 3 independent tests. The fold increase was determined by comparing the EC50 of PA-substituted virus with the respective control virus.

The percentage difference was determined by comparing the mean AUC value of PA-substituted virus with that of the respective control virus (set at 100%).

indicates statistical significant (P < .05) difference between AUC8–72 for PA-I38-substituted virus and its control.

Viruses carrying I38T and I38S were selected in MDCK cells in the presence of baloxavir and purified by limiting dilution.

A/Bangladesh/3007/2017 virus isolate (GISAID ID: S2 isolate EPI_ISL_286069; original specimen EPI_ISL_282881) contained viral subpopulations with I38 or I38T in PA protein, which were separated by limiting dilution.

METHODS

Viruses

Influenza viruses were submitted to the Collaborating Center for Surveillance, Epidemiology and Control of Influenza, at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (Atlanta, GA) by laboratories participating in the World Health Organization (WHO) Global Influenza Surveillance and Response System (GISRS). A(H1N1)pdm09 viruses were propagated in Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells (ATCC, Manassas, VA), whereas A(H3N2) viruses were propagated in MDCK-SIAT1 (kindly provided by M. Matrosovich, Institute of Virology, Marburg, Germany) cells. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) analysis identified a mixture of PA-38I/T (39% of T) in the A/Bangladesh/3007/2017 (H3N2) virus isolate (passage S2), from which viruses with I38 and I38T were separated by limiting dilution (Table 1). I38T was not detected in the matching clinical specimen; passage S1 isolate was not available for analysis.

A(H1N1)pdm09 viruses carrying either PA-I38S or PA-I38T were obtained by culturing A/Illinois/08/2018 (control virus) in MDCK cells for 5 passages in the presence of increasing concentrations of baloxavir (1–100 nM); they were then purified by limiting dilution. All virus stocks used in this study were analyzed by NGS before phenotypic testing.

Next-Generation Sequencing and Pyrosequencing

Codon-complete genome sequences of viruses were obtained by NGS using Illumina platform and analyzed by the IRMA (iterative refinement meta-assembler) approach with single-nucleotide variant threshold of 5% [6]. Pyrosequencing was performed to identify amino acid polymorphism at residue 38 in PA as previously described [4]. PyroMark Q96 ID software was used to quantify a single-nucleotide polymorphism.

Determination of Baloxavir Susceptibility

Virus isolates were tested by high-content imaging neutralization test (HINT) as previously described [4], and baloxavir EC50 (50% effective concentration that reduces the number of virus-infected cells by half) was determined.

Evaluation of Replicative Capacity of Viruses in Cell Culture

The MDCK and MDCK-SIAT1 cell monolayers were inoculated at a multiplicity of infection of 0.0001, and virus was allowed to adsorb for 1 hour at 37°C in 5% CO2. Virus inoculum was removed, virus growth media supplemented with 3 μg/mL TPCK-trypsin was added, and cells were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 72 hours. The culture supernatants were collected at indicated time points and infectious virus titers were determined. The area under the curve (AUC) for viral titers was calculated by the trapezoidal rule (GraphPad Prism 5; GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA), using viral titers at 8–72 hours postinfection (hpi). The AUC8–72 for controls and respective PA-I38-substituted viruses were compared by unpaired t test with Welch’s correction.

Replicative Capacity in a Ferret Model

Animal experiments were conducted in strict compliance with the guidelines of the CDC Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee in association with the PHS Policy, the Animal Welfare Act (US Department of Agriculture), and the Guide for Animal Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Male ferrets (Mustela putorius furo) aged 3 to 5 months (Triple F Farms, Gillett, PA) and serologically negative for currently circulating seasonal viruses by hemagglutination inhibition assay were used in this study. Ferrets (4 per group) were intranasally (i.n.) inoculated with 103 50% tissue culture infectious dose (TCID50) of virus diluted in 1 mL sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), under anesthesia. Nasal washes were collected daily under anesthesia for 8 days postinfection (dpi) by flushing nostrils with 1 mL sterile PBS as previously described [7].

For competitive virus growth experiments, ferrets (4 per group) were i.n. inoculated with a mixture of 2 viruses, control, and its PA-I38-substituted counterpart, at ratios 10:90, 30:70, or 70:30 (confirmed by pyrosequencing). Each animal received 103 TCID50 of virus mixture in 1 mL PBS. Nasal washes were collected at indicated dpi, and proportion of the respective virus populations was determined by pyrosequencing.

RESULTS

Effect of Polymerase Acidic-I38 Substitutions on Baloxavir Susceptibility of A(H1N1)pdm09 and A(H3N2) Viruses

In this study, we characterized 5 PA-I38-substituted influenza A viruses that emerged either naturally or under selective pressure of baloxavir in cell culture. Matching control viruses (PAI38) were included for comparison (Table 1). The baloxavir EC50 values determined for the 3 control viruses ranged 1.3–1.8 nM. Viruses carrying I38M and I38L displayed elevated EC50, 13.6 and 16.7 nM, respectively. In A(H1N1)pdm09 background, I38S and I38T conferred higher EC50 (92.0–94.1 nM); to our knowledge, the effect of I38S on susceptibility has not yet been reported. The I38T in A(H3N2) background conferred the highest EC50 (153.8 nM), leading to 116-fold decrease in baloxavir susceptibility. Overall, the data supports previous findings that various substitutions at PA residue 38 confer differential effects on baloxavir susceptibility [3].

In Vitro Replicative Fitness of Polymerase Acidic-I38-Substituted A(H1N1) pdm09 and A(H3N2) Viruses

Next, we assessed the growth kinetics of PA-I38-substituted viruses and their respective controls (paired viruses) in MDCK and MDCK-SIAT1 at 8–72 hpi. Paired viruses replicated to similar peak titers by 48 hpi in both cell lines (Supplementary Figure S1). Except for A(H1N1)pdm09-I38L, the other 4 PA-I38-substituted viruses (I38M/S/T) grew slower at early time points (8–24 hpi) compared with their controls. The delayed growth varied between viruses and cell lines. These 4 PA-I38-substituted viruses (I38M/S/T) displayed a decrease in titers by ≥1 log10 TCID50/mL at 1 or more time points in MDCK-SIAT1 cells. However, in MDCK cells, this was only observed for the A(H1N1)pdm09 (I38S/T) viruses (Supplementary Figure S1).

Next, we compared the overall growth of paired viruses by measuring AUC8–72 of virus titers (Table 1). A(H1N1)pdm09I38L displayed a small gain (5%) in both cells, but the difference was not statistically significant. A(H1N1)pdm09 viruses carrying I38T or I38S showed 6%–12% reduction in AUC8–72 (Table 1). Similarly, A(H3N2) viruses carrying I38M or I38T displayed 7%–13% reduction in AUC8–72 (Table 1). Thus, with exception of I38L, all PA-I38-substituted viruses (I38M/S/T) showed slightly decreased AUC8–72, indicating mild attenuation in virus growth.

Replicative Capacity of Polymerase Acidic-I38-Substituted A(H3N2) Viruses in Ferrets

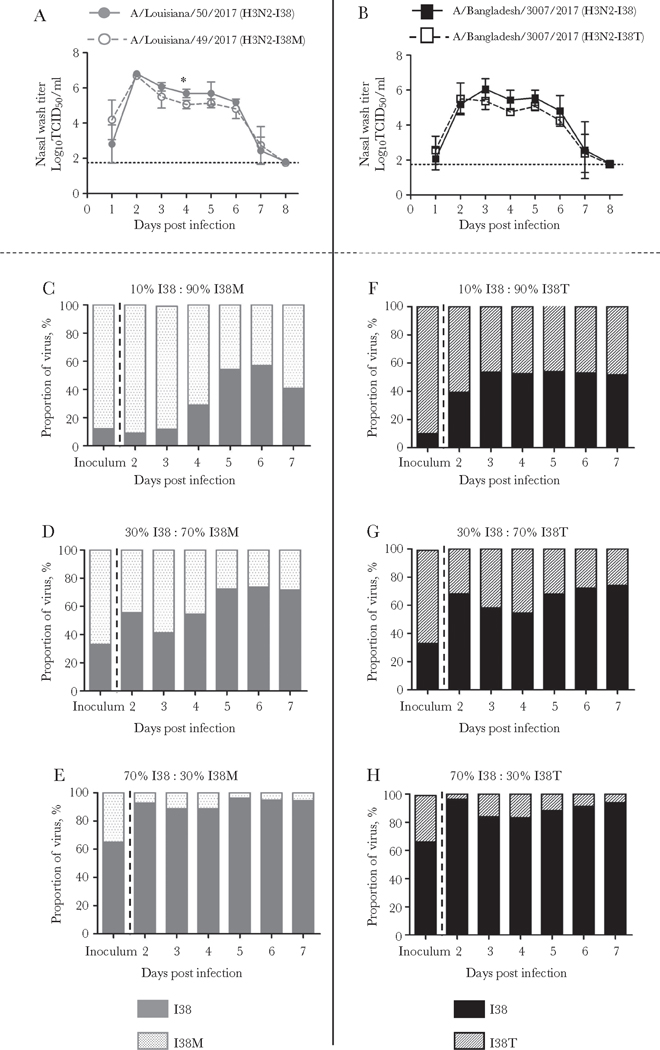

Next, the viral fitness of A(H3N2) viruses with I38M or I38T, which showed mild attenuation in vitro, was tested using a ferret model along with their respective controls. After inoculation with the virus, nasal washes were collected daily and used to determine infectious virus titers and to check viral PA sequences at codon 38. Ferrets from all 4 groups shed infectious virus for 7 consecutive days with titers peaking on 2 dpi (Figure 1A and B). No reversion to I38 was detected in viruses collected from ferrets inoculated with either I38M or I38T, indicating that these substitutions are genetically stable (Supplementary Figure S2).

Figure 1.

(A and B) Effect of polymerase acidic (PA) substitutions I38M and I38T on A(H3N2) virus replication in ferrets. Animals (4 per group) were intranasally inoculated with 103 50% tissue culture infectious dose (TCID50) of virus, (A) control I38 and I38M viruses, and (B) control I38 and I38T viruses. Nasal washes were collected at indicated days postinfection (dpi) and virus titers were determined. Dotted line indicates the lower limit of virus detection, 1.75 log10 TCID50/mL. Data shown are mean ± standard deviation, and the unpaired t test with Welch’s correction was used for statistical comparisons (*, P < .05). (C–H) Proportions of virus subpopulations in the nasal washes of ferrets. Ferrets (4 per group) were inoculated with 103 TCID50 containing control and PA-I38-substituted A(H3N2) virus mixed at ratios 10:90, 30:70, or 70:30; (C–E) control I38 and I38M viruses and (F–H) control I38 and I38T viruses. Nasal washes were collected at indicated dpi, and proportion of the respective PA subpopulations were determined by pyrosequencing using single-nucleotide polymorphism analysis.

Numerically, the virus titers of the I38M group were slightly lower; however, statistical significance (P = .01) was only seen on 4 dpi. Moreover, there was no difference between the viral titer AUC1–8 (21.9 ± 0.9 vs 20.7 ± 1.2; P = .39) (Figure 1A). A similar pattern of lower nasal wash titers was seen in the I38T group (Figure 1B), but, again, the difference was not statistically significant (AUC1–8, 19.3 ± 1.5 vs 17.2 ± 1.2; P = .28). Overall, there were no substantial differences in disease symptoms between the paired virus groups (results not shown).

To gain further insight into replicative fitness of the baloxavir-resistant A(H3N2) viruses, we performed competitive growth experiments in the ferret model. To this end, control virus and the respective PA-substituted counterpart were mixed at ratios 10:90, 30:70, or 70:30 and used to infect ferrets. Nasal washes were collected daily to determine the proportion of the respective PA subpopulations. Expectedly, the proportion of I38 virus population increased incrementally over time in all groups, indicating control virus as a better-fit virus. This trend was observed in both virus pairs used in this study, I38/I38M and I38/I38T. However, the within-host replicative advantage of I38 viruses was limited, because the I38-substituted subpopulations remained detectable as late as 7 dpi (Figure 1C–H).

DISCUSSION

The reports on replicative fitness of baloxavir-resistant viruses remain sparse. In this study, both A(H3N2) viruses with I38T or I38M displayed genetic stability during the course of infection in ferrets. In the competitive growth experiments, the control viruses had growth advantage over their respective baloxavir-resistant counterparts in the ferret upper respiratory tract, although the difference was small. These results were consistent with our in vitro results, where I38T and I38M substitutions were associated with ~1 log10-reduced titers in MDCK-SIAT1 cells at early time points; the difference was marginal in MDCK cells. It is notable that I38T was associated with ~1- to 3-log10 reduction in virus titers, depending on experimental conditions and genetic background [1, 3]. Likewise, I38M in a swine A(H6N6) virus did not affect replication in MDCK cells and mice [8], whereas in an A(H1N1) background it was associated with ~2-log10 reduction [3]. In the present study, I38L in A(H1N1)pdm09 background did not attenuate virus replication in either cell line, whereas I38S conferred up to 1.6-log10 reduction at early time points in both cells. One of the study’s limitations is the presence of an additional single amino acid substitution in genomes of 3 PA-substituted viruses (Table 1); to our knowledge, these substitutions are unlikely to influence virus growth.

Overall, PA-I38 substitutions (I38M/S/T) attenuated virus replication. However, this conclusion seems to counter other observations. Also of note, Takashita et al [9] reported that culturing A(H3N2) viruses collected from baloxavir-treated patients favored the growth of PA-I38-substituted viruses. In our study, although I38T subpopulation was not detected in the A/Bangladesh/3007/2017 (H3N2) clinical specimen, it comprised 39% of the S2 virus isolate, thus indicating a growth advantage (S1 isolate was not available). Besides PA-I38T, 2 other substitutions, HA-N45T and NA-T71I, were detected in this isolate; however, their impact on growth kinetics is unknown. We suggest that the increase in the proportion of PA-I38M/T viruses during passage is not necessarily a result of their better growth. It may be a consequence of prolonged propagation. We showed that PA-I38-substituted viruses replicated slower at early time points, but their infectious titers were similar at 72 hpi (Supplementary Figure S1). Considering that newly synthesized viruses may undergo inactivation in cell culture supernatants, a late harvest of isolates could favor the slower replicating PA-I38-substituted viruses, because fewer of them would be inactivated. Because PA-I38 substitutions can emerge during virus propagation, it is prudent to confirm the presence of the substitution in the clinical specimen.

The residue 38 is part of the enzyme active site and is positioned to interact with the RNA substrate and baloxavir [3, 10]. The amino acid leucine at this position conferred the least effect on baloxavir susceptibility and had no apparent effect on virus growth. All other substitutions (I38M/S/T) in this study had an effect on baloxavir susceptibility that was either similar to I38L or more pronounced, but they showed slightly impaired replication at early time points. It is worth noting that both I38T and I38S were associated with ~50- to 116-fold decreased susceptibility to baloxavir.

CONCLUSIONS

In this study, we provided data on replicative fitness of baloxavir-resistant viruses that are needed to inform public health risk assessment. Replication of the PA-I38-substituted viruses was only mildly impaired, yet it may reduce their airborne transmission. This assumption needs to be investigated. Moreover, PA-I38-substituted viruses may rapidly restore full replicative capacity by acquiring compensatory changes. They can also gain evolutionary advantage via antigenic drift or shift. Therefore, it is essential to closely monitor the emergence of PA-I38-substituted viruses and their spread in communities.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We are most grateful to Shionogi and Co., LTD. for kindly providing baloxavir acid for phenotypic testing. We are thankful to US public health laboratories and other laboratories of the World Health Organization (WHO) Global Influenza Surveillance and Response System (GISRS) for timely submission of influenza viruses to the virological surveillance conducted by the WHO Collaborating Center (Atlanta, GA). We are also thankful to the Comparative Medicine Branch at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) for quality animal husbandry. We thank and acknowledge the valuable contributions of Drs. John Barnes and Samuel Shepard for assistance in analyzing next-generation sequencing data.

Disclaimer. The findings and conclusions of this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the funding institution.

Financial support. This work was funded by the Influenza Division, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Footnotes

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at The Journal of Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts of interest. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest.

References

- 1.Noshi T, Kitano M, Taniguchi K, et al. In vitro characterization of baloxavir acid, a first-in-class cap-dependent endonuclease inhibitor of the influenza virus polymerase PA subunit. Antiviral Res 2018; 160:109–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hayden FG, Sugaya N, Hirotsu N, et al. Baloxavir marboxil for uncomplicated influenza in adults and adolescents. N Engl J Med 2018; 379:913–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Omoto S, Speranzini V, Hashimoto T, et al. Characterization of influenza virus variants induced by treatment with the endonuclease inhibitor baloxavir marboxil. Sci Rep 2018; 8:9633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gubareva LV, Mishin VP, Patel MC, et al. Assessing baloxavir susceptibility of influenza viruses circulating in the United States during the 2016/17 and 2017/18 seasons. Euro Surveill 2019; 24:1800666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stevaert A, Dallocchio R, Dessì A, et al. Mutational analysis of the binding pockets of the diketo acid inhibitor L-742,001 in the influenza virus PA endonuclease. J Virol 2013; 87:10524–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shepard SS, Meno S, Bahl J, Wilson MM, Barnes J, Neuhaus E. Viral deep sequencing needs an adaptive approach: IRMA, the iterative refinement meta-assembler. BMC Genomics 2016; 17:708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marjuki H, Mishin VP, Chesnokov AP, et al. Neuraminidase mutations conferring resistance to oseltamivir in influenza A(H7N9) viruses. J Virol 2015; 89:5419–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tan L, Su S, Smith DK, et al. A combination of HA and PA mutations enhances virulence in a mouse-adapted H6N6 influenza A virus. J Virol 2014; 88:14116–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takashita E, Kawakami C, Ogawa R, et al. Influenza A(H3N2) virus exhibiting reduced susceptibility to baloxavir due to a polymerase acidic subunit I38T substitution detected from a hospitalised child without prior baloxavir treatment, Japan, January 2019. Euro Surveill 2019; 24:1900170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jones JC, Kumar G, Barman S, et al. Identification of the I38T PA substitution as a resistance marker for next-generation influenza virus endonuclease inhibitors. MBio 2018; 9:e00430–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.