Abstract

A series of thiazol-4-one/thiophene-bearing pyrazole derivatives as pharmacologically attractive cores were initially synthesized using a hybridization approach. All structures were confirmed using spectra analysis techniques (IR, 1H NMR, and 13C NMR). In vitro antimicrobial activities, including the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC), minimum bactericidal/fungicidal concentration (MBC/MFC), and time-kill assay, were evaluated for the most active derivatives 4a, 5a, 7b, 10, and 13. These derivatives were significantly active against the tested pathogens, with compound 7b as the most active derivative (MIC values range from 0.22 to 0.25 μg/mL). In the MBC and MFC, the active target pyrazole derivatives showed -cidal activities toward the pathogenic isolates. Further, the inhibition of biofilm formation of Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis was also carried out. Additionally, these derivatives displayed significant antibiofilm potential with a superior % reduction in the biofilm formation compared with Ciprofloxacin. The target derivatives behaved synergistically with Ciprofloxacin and Ketoconazole, reducing their MICs. Hemolytic results revealed that these derivatives were nontoxic with a significantly low hemolytic activity (%lysis range from 3.23 to 15.22%) compared with Triton X-100 and showed noncytotoxicity activity with IC50 values > 60 μM. In addition, these derivatives proved to be active DNA gyrase and DHFR inhibitors with IC50 ranging between 12.27–31.64 and 0.52–2.67 μM, respectively. Furthermore, compound 7b showed bactericidal activity at different concentrations in the time-kill assay. Moreover, a gamma radiation dose of 10.0 kGy was efficient for sterilizing compound 7b and enhancing its antimicrobial activity. Finally, molecular docking simulation of the most promising derivatives exhibited good binding energy with different interactions.

1. Introduction

Bacterial infection is among the top 10 causes of death and the first infectious disease-causing mortality worldwide.1 The evolution of drug-resistant strains, viz., methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and Staphylococcus epidermidis (MRSE), has unfortunately augmented both nosocomial and inherent mortality rates, which poses an imperative threat to human health.2 Nowadays, the development of new antibacterial compounds to combat human bacterial infections has become a big challenge, and that may be related to the explicit and repeated use of antibiotics.3,4 Recently, only four new classes of antibiotics have been approved by FDA over the past 17 years, while most current drugs have the same well-understood target.5,6 The thiazole moiety is found in several substances, including thiamine (vitamin B1), thiamine pyrophosphate (TPP), bacitracin, amoxicillin, cefotaxime, and sulfathiazole.7−10 Additionally, thiazole derivatives have emerged as a new class of potent antimicrobial agents, which are reported to inhibit bacteria by many different mechanisms such as blocking the biosynthesis of certain bacterial lipids11 and inhibiting DNA gyrase B12,13 and dihydrofolate reductase.14

Pyrazole is one of the most prevalent nitrogen heterocyclic cores in many biologically active natural and synthetic compounds, which has received substantial attention in medicinal chemistry and drug design research.15,16 Some drugs with pyrazole pharmacophores such as Celecoxib and Lonazolac (anti-inflammatory), Betazole (H2-receptor agonist), and Fezolamine (antidepressant) have been used in clinical applications.17

Furthermore, persistent biofilms are a key virulence factor, which is recognized as the principal cause of chronic and frequent bacterial infections ensuing an estimated 17 million new biofilm infections and more than five hundred thousand deaths each year.18 Biofilms make the bacteria resistant to conventional antibiotics by around 1000-fold.19 Subsequently, there is an urgent need to counter biofilm formation and develop new antibacterial agents to exert anti-biofilm activities.20 This situation requires the development of new antibacterial drugs with entirely distinct chemical structures, which may have a different mode of action than currently available therapeutic medications.21

DNA gyrase is composed of two subunits, GyrA and GyrB, forming a complex in the active form of the enzyme to which DNA binds. Both subunits interact with DNA; the GyrA subunit contains the tyrosine required for DNA cleavage, while the GyrB subunit contains the ATPase active site.22,23 The crucial role of DNA gyrase in the bacterial and mycobacterial viability and its lack in the higher eukaryotes make this enzyme a proper target for developing potential drugs from the viewpoint of selective toxicity.24−26

Sterility of the different pharmaceutical products is a serious aspect of ensuring their safe and effective use upon administration via the parenteral route. Sterilization by gamma irradiation has shown significant applicability for a wide range of pharmaceutical agents and has been approved by the European Pharmacopeia. Additionally, gamma sterilization is a very attractive method for terminal sterilization, considering its ability to attain a 10–6 probability of microbial survival without causing excessive product heating or exposure to toxic chemicals.27

Hybridizing two or more scaffolds in one molecule to create a new hybrid molecule is useful for developing new therapeutic agents.28−34 Based on these things mentioned above, herein, we report the design and synthesis of novel series of pyrazole derivatives incorporating thiazol-4-one/thiophene in one molecule via conventional synthetic approaches to obtain new pyrazole derivatives (Figure 1). The new hybrid molecules were screened against three Gram-positive, three Gram-negative bacteria, and two Candida albicans isolates. The five most active derivatives were used to determine the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC), minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC), and minimum fungicidal concentration (MFC) using the broth microdilution technique, Staphylococcus biofilm mass reduction, synergistic effect, time-kill kinetic assay, in vitro cytotoxic activity against three normal cell lines, and finally study of their mode of action using two different mechanisms as DNA gyrase and DHFR inhibitors. A molecular docking study was performed to confirm the binding mode and confirm the target’s action.

Figure 1.

Structures of the antibiotics containing pyrazole or thiazole/tetrahydrothiazole moieties as bioactive cores and our designed derivatives.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Chemistry

The synthetic strategy pathway of the new pyrazole derivatives is depicted from Schemes 1–4. First, 2-(4-oxothiazolidin-2-ylidene) derivatives (1a and 1b)35 were used as precursor builders to synthesize many biologically and pharmaceutically active heterocycles.14,36 The thiazolidin-4-one derivatives 1a and 1b were coupled with 1,3-diaryl-1H-pyrazole-4-carboxaldehyde derivatives 2a and 2b(37) in the presence of ethanol catalyzed with piperidine to produce 4-oxo-5-((substituted-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)methylene)thiazolidin-2-ylidene derivatives (3a38,39 and 3b–d) and failed to obtain 2-(4-oxo-4,5-dihydrothiazol-2-yl)-3-(1-,3-(diaryl)-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)acryl derivatives 4a–d. The condensation reaction proceeds through the endocyclic methylene rather than the exocyclic one.40 The structures of 3a–d were confirmed with the help of analytical and spectroscopic data. Thus, the IR spectrum of pyrazole derivative 3b showed significant stretching absorption bands at υ 3199, 2202, and 1718 cm–1 owing to NH, cyano (CN), and carbonyl (C=O) groups, respectively. The 1H NMR spectrum of pyrazole derivative 3b showed characteristic singlet signals at δ 2.34 ppm, corresponding to a methyl group, and δ 4.96, 7.92, 8.78, and 11.99 ppm due to two methylinic protons (methine-H), pyrazole-H, and one exchangeable NH proton. In addition, nine aromatic protons ranged between δ 7.41 and 8.09 ppm, which displayed two triplet and three doublet signals. Also, the 13C NMR spectra of compound 3d assigned significant signals at δ 20.81, 14.21, 59.55, and 166.68 ppm corresponding to methyl, ethoxy, and carbonyl groups.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of Pyrazole Derivatives Containing Thiazol-4-one Moieties.

Scheme 4. Synthesis of 4-Oxothiazoles and Thiazolo[3,2-a]pyridine Derivatives Having a Pyrazole Scaffold.

Scheme 2. Synthesis of Thiazolin-4-one and 4-Aminothiophene-3-carboxylate Derivatives Containing Pyrazole Moieties.

Additionally, synthesizing thiazol-4-ones with bis-arylmethylidine scaffolds 5a–c can happen via refluxing the 5-arylmethylidino-4-thiazolidinone derivative 3a with different aromatic aldehydes in the presence of ethanol containing a catalytic amount of piperidine. The structures of 3-(aryl)-2-(5-((1H-pyrazol-4-yl)methylene)-4-oxo-4,5-dihydro-thiazol-2-yl)acrylonitrile 5a–c were established through correct elemental analysis and spectroscopic data (Scheme 1). The IR spectra of acrylonitrile derivatives 5a–c furnished characteristic absorption bands for cyano and carbonyl groups at υ 2197–2199 and 1710–1721 cm–1 and absent bands at nearly 3135–3388 cm–1 for the NH group. The 1H NMR spectrum of acrylonitrile derivative 5a (DMSO-d6) exhibited characteristic signals at δ 7.64, 7.94, 9.14, and 10.02 ppm corresponding to two methine-H, pyrazole-H, and hydroxyl groups, respectively. Furthermore, the 13C NMR spectrum of compound 5b displayed signals at δ 153.54, 154.17, 155.74, and 162.62 ppm attributed to C=C, C=N, S–C=N, and C=O groups, respectively.

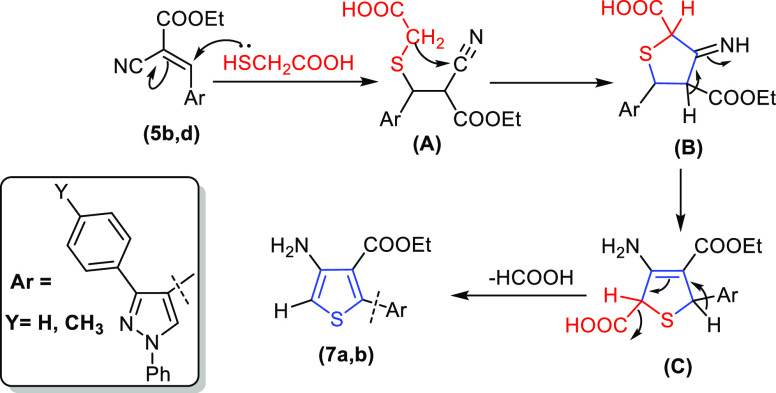

The formation of thiazolin-4-one derivatives 4a–d was supposed to proceed by reaction of 2-((1,3-diaryl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)methylene)malononitrile or ethoxy carbonyl malononitrile 6a–d(37) with sulfanylacetic acid in dimethyl formamide (DMF) that contains catalytic amounts of piperidine, but the reaction proceeds by two different pathways. Cyclization of 2-((1,3-diaryl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)methylene)malononitrile 6a and6b formed 3-(1,3-diaryl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)-2-(4-oxo-4,5-dihydrothiazol-2-yl)acrylonitrile 4a and 4b, while ethyl 2-cyano-3-(1,3-diaryl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)acrylate 6c and 6d formed ethyl 4-amino-2-(1,3-diaryl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)thiophene-3-carboxylate 7a and 7b (the suggested mechanism is illustrated in Scheme 3).

Scheme 3. Suggested Mechanism with the Intermediates (A, B, and C) for the Synthesis of 4-Amino-thiophene-3-carboxylate Derivatives Containing Pyrazole Moieties 7a and 7b.

The structures of both 2-(4-oxo-4,5-dihydrothiazol-2-yl)acrylonitrile 4a and 4b and 4-amino-2-(substituted)thiophene-3-carboxylate 7a and 7b were confirmed by spectroscopic data and elemental analysis. The IR spectra of compounds 4a and 4b displayed absorption bands at υ 2202–2210 and 1714–1720 cm–1 related to the cyano and carbonyl of thiazolin-4-one. Conversely, the IR spectra of compounds 7a and 7b showed the absence of absorption bands for the cyano and carbonyl of thiazolin-4-one and presented new bands at υ 3345–3432, 1685–1686 cm–1 corresponding to the amino and carbonyl of ester groups. The 1H NMR spectrum of 2-(4-oxo-4,5-dihydrothiazol-2-yl)acrylonitrile derivative 4b demonstrated four singlet signals at δ 2.49, 4.72, 8.80, and 8.85 ppm due to methyl, methylene groups, methine-H, and pyrazole-H, respectively. On the other hand, the 1H NMR spectra of the thiophene-3-carboxylate derivative 7b displayed triplet and quartet signals due to five protons at δ 1.30 and 4.31 ppm for the ethoxy group and three singlet signals at δ 2.39, 8.09, and 9.13 ppm corresponding to methyl, two protons of a methine group, and a pyrazole moiety. In addition, the singlet signal at δ 7.49 ppm was related to an amino group that was exchangeable with D2O and the absence of methylene singlet signal at nearly δ 4.72 ppm. The 13C NMR spectra of the thiophene-3-carboxylate 7a are characterized by signals at δ 13.96, 62.13, 155.20, and 161.83 ppm, assignable to an ethoxy group, C-NH2, and carbonyl group (C=O), respectively.

Moreover, it was interesting to synthesize a 4-oxothiazole derivative having 4-aminoantipyrine scaffold 8, and this happened via cyano acetylation of 4-aminoantipyrene41 followed by cyclization with sulfanylacetic acid to afford N-(1H-pyrazol-4-yl)-2-(4-oxo-4,5-dihydrothiazol-2-yl)acetamide derivative 10 (Scheme 4). In a diazo coupling reaction, the diazonium salt of 4-aminoantipyrine 11 acted as an electrophile and reacted with malononitrile to form the pyrazolo-hydrazonoyl dicyanide derivative 12(42) that underwent cyclization with sulfanylacetic acid under reflux conditions to produce N-substituted-4-oxo-4,5-dihydrothiazole-2-carbohydrazonoyl cyanide derivative 13. The IR spectrum of compound 10 showed bands at υ 3436, 3061, 2917, 1688, and 1659 cm–1 due to NH, CH-aromatic, CH-aliphatic, and carbonyl groups, respectively. The 1H NMR spectra of compound 10 revealed signals at δ 2.19 and 3.08 ppm for two methyl groups of an antipyrine derivative and signals at δ 3.23 and 4.34 ppm owing to two methylene groups, in addition to the exchangeable signal at δ 7.17 ppm corresponding to NH and five aromatic protons that appeared between δ 7.36 and 7.50 ppm. Additionally, coupling the 4-oxothiazole derivative 1a with the diazonium salt of 4-aminoantipyrine 11(42) attacked the endocyclic methylene group in position five to afford 2-(5-hydrazonyl-4-oxo-4,5-dihydrothiazol-2-yl)acetonitrile derivative 14.

Furthermore, the acetonitrile derivative 14 was condensed with different aromatic aldehydes (1:1 molar ratio) in ethanol with drops of piperidine to give the corresponding 3-aryl-2-(5-(2-substituted-hydrzono)-4-oxo-4,5-dihydrothiazol-2-yl)acrylonitrile derivatives 15a and 15b. The IR spectra of compounds 15a and 15b displayed bands at υ 3181–3200, 2196–2205, and 1703–1708 cm–1 corresponding to NH, CN, and carbonyl groups, respectively. The 1H NMR spectrum of compound 14 presented signals at δ 2.54, 3.31, 4.04, and 7.39 ppm corresponding to the two methyl groups of an antipyrine moiety, methylene, and NH groups. In a similar manner, the 1H NMR spectra of compound 15a presented four singlet signals at δ 2.49, 3.01, 7.35, and 8.37 ppm owing to two methyl groups of an antipyrine derivative, a methylinic proton, and a NH group, in addition to 10 aromatic protons ranging between δ 7.42 and 7.66 ppm. The 13C NMR spectrum of compound 15a showed signals at δ 10.91 and 34.11 ppm related to two methyl groups and δ 143.37, 148.91, 157.84, and 174.93 ppm corresponding to C=N, S–C=N, and two carbonyl groups, in addition to the aromatic carbons that were observed between δ 105.89 and 134.52 ppm.

Finally, the cyclization of 3-aryl-2-(5-(2-substituted-hydrzono)-4-oxo-4,5-dihydrothiazol-2-yl)acrylonitrile derivatives 15a and 15b with malononitrile in catalyzed ethanol piperidine produced the 2,3-dihydro-7H-thiazolo[3,2-a]pyridine-6,8-dicarbonitrile derivatives 16a and 16b. Similarly, the thiazolo[3,2-a]pyridine-6,8-dicarbonitrile derivatives 16a and 16b were formed by either one-pot reaction of 2-(5-hydrazonyl-4-oxo-4,5-dihydrothiazol-2-yl)acetonitrile derivative 14 with aromatic aldehyde and malononitrile or by refluxing with arylidene-malononitrile in absolute ethanol having a little amount of piperidine (three drops). The structures of the prepared compounds 16a and 16b were proven through accurate analysis. The IR spectrum of 2,3-dihydro-7H-thiazolo[3,2-a]pyridine-6,8-dicarbonitrile derivative 16a revealed absorption bands in the zones of υ 3442, 3318, 3117, 2201, and 1700 cm–1 corresponding to an amino, imine, cyano, and significant carbonyl for thiazolidine-4-one, respectively. Its 1H NMR spectrum (DMSO-d6) showed a notable singlet signal of pyridine-H at δ 4.02 ppm, in addition to two exchangeable signals at δ 5.24 and 7.35 ppm for NH and NH2 protons. Moreover, the 13C NMR spectrum (DMSO-d6) exhibited significant singlet signals at δ 10.61, 34.37, 38.63, 144.63, 150.11, 154.24, and 156.51 ppm for two methyl groups of an antipyrine derivative, pyridine-H4, C=N, carbon attached to the amino group, and two carbonyl groups, respectively (Scheme 4).

2.2. Biological Activity

2.2.1. Antimicrobial Sensitivity Assay by an Agar Well-Diffusion Method

Screening was carried out for the in vitro antimicrobial activity against three Gram +ve and three Gram -ve bacteria as well as two C. albicans isolates. The broad-spectrum antibiotics, Ciprofloxacin, and Ketoconazole were used as positive controls. The zones of inhibition are presented in Table 1 in mm. According to the given data, five pyrazole derivatives 4a, 5a, 7b, 10, and 13 displayed excellent activities with inhibition zones ranging from 25 to 33 mm against the bacterial pathogens and ranging from 28 to 32 mm against the fungal pathogens in comparison with the reference drugs. On the other hand, the rest of the compounds showed moderate to no antimicrobial activity.

Table 1. Inhibition Zone (IZ) in mm ± Standard Deviation of Pyrazole Derivatives and Reference Drugs against the Pathogenic Microbesa.

| Gram +ve bacteria |

Gram -ve bacteria |

fungi |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cpd. No. | S. aureus | S. epidermidis | B. subtilis | E. coli | A. baumannii | K. pneumoniae | C. albicans100 | C. albicans200 |

| 3a | -ve | -ve | -ve | -ve | -ve | -ve | -ve | -ve |

| 3b | 15 ± 0.63 | 17 ± 0.21 | 12 ± 0.50 | 16 ± 0.34 | 14 ± 0.50 | 16 ± 0.77 | 13 ± 0.22 | 15 ± 0.80 |

| 3c | 13 ± 0.46 | 15 ± 0.70 | 14 ± 0.80 | 18 ± 0.33 | 12 ± 0.32 | 14 ± 0.60 | 15 ± 0.45 | 14 ± 0.30 |

| 3d | 15 ± 0.78 | 16 ± 0.10 | 13 ± 0.47 | 15 ± 0.67 | 11 ± 0.23 | 13 ± 0.11 | 13 ± 0.60 | 16 ± 0.22 |

| 4a | 31 ± 0.18 | 28 ± 0.13 | 29 ± 0.42 | 26 ± 0.33 | 26 ± 0.14 | 27 ± 0.16 | 29 ± 0.23 | 31 ± 0.22 |

| 4b | 20 ± 0.20 | 19 ± 0.31 | 21 ± 0.50 | 22 ± 0.60 | 20 ± 0.30 | 21 ± 0.12 | 22 ± 0.10 | 23 ± 0.22 |

| 5a | 29 ± 0.22 | 27 ± 0.24 | 25 ± 0.37 | 28 ± 0.14 | 25 ± 0.11 | 26 ± 0.20 | 28 ± 0.40 | 30 ± 0.60 |

| 5b | 24 ± 0.20 | 21 ± 0.10 | 22 ± 0.55 | 22 ± 0.56 | 20 ± 0.42 | 21 ± 0.32 | 23 ± 0.26 | 25 ± 0.77 |

| 5c | 22 ± 0.66 | 24 ± 0.28 | 23 ± 0.22 | 21 ± 0.45 | 19 ± 0.23 | 22 ± 0.76 | 21 ± 0.52 | 24 ± 0.13 |

| 7a | 24 ± 0.40 | 21 ± 0.12 | 23 ± 0.11 | 22 ± 0.41 | 20 ± 0.12 | 22 ± 0.60 | 21 ± 0.32 | 25 ± 0.33 |

| 7b | 33 ± 0.32 | 31 ± 0.16 | 28 ± 0.22 | 30 ± 0.50 | 29 ± 0.12 | 27 ± 0.30 | 31 ± 0.11 | 32 ± 0.32 |

| 10 | 27 ± 0.21 | 26 ± 0.4 | 26 ± 0.32 | 25 ± 0.22 | 26 ± 0.31 | 25 ± 0.66 | 28 ± 0.88 | 30 ± 0.55 |

| 12 | -ve | -ve | -ve | -ve | -ve | -ve | -ve | -ve |

| 13 | 27 ± 0.82 | 25 ± 0.45 | 26 ± 0.35 | 28 ± 0.55 | 27 ± 0.44 | 25 ± 0.4 | 29 ± 0.25 | 28 ± 0.36 |

| 14 | 16 ± 0.21 | 19 ± 0.23 | 14 ± 0.44 | 17 ± 0.35 | 15 ± 0.34 | 15 ± 0.44 | 18 ± 0.66 | 20 ± 0.88 |

| 15a | 16 ± 0.59 | 18 ± 0.56 | 17 ± 0.23 | 15 ± 0.77 | 16 ± 0.33 | 14 ± 0.98 | 16 ± 0.44 | 20 ± 0.58 |

| 15b | 18 ± 0.44 | 16 ± 0.25 | 17 ± 0.56 | 16 ± 0.85 | 13 ± 0.42 | 16 ± 0.67 | 16 ± 0.34 | 18 ± 0.76 |

| 16a | -ve | -ve | -ve | -ve | -ve | -ve | -ve | -ve |

| 16b | -ve | -ve | -ve | -ve | -ve | -ve | -ve | -ve |

| CIP | 23 ± 0.3 | 24 ± 0.12 | 22 ± 0.33 | 20 ± 0.24 | 21 ± 0.2 | 19 ± 0.11 | NA | NA |

| KCA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 21 ± 0.23 | 24 ± 0.54 |

| DMSO | -ve | -ve | -ve | -ve | -ve | -ve | -ve | -ve |

CIP: Ciprofloxacin (no activity (≤18 mm), moderate activity (19–24 mm), and strong activity (≥25 mm)); KCA: ketoconazole (no activity (≤20 mm), moderate activity (21–27 mm), and strong activity (≥28 mm)); DMSO: dimethyl sulfoxide; NA: non-applicable. The reference drugs and compounds were prepared in a concentration of 100 mg/mL.

2.2.2. Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) and Minimum Bactericidal/Fungicidal Concentration (MBC/MFC) Determination

The MIC values of the most active pyrazole derivatives 4a, 5a, 7b, 10, and 13 were measured in vitro using the broth microdilution technique, as presented in Table 2 and Table S1. It was noticed that the pyrazole containing thiophene-3-carboxylate derivative 7b exhibited the highest MIC value among the other derivatives over all the tested pathogens, with MICs ranging between 0.22 and 0.25 μg/mL. Moreover, the pyrazolo-thiazolin-4-one derivatives 4a and 5a were equally potent with the reference, Ciprofloxacin, against E. coli (MIC = 0.45 and 0.46 μg/mL, respectively), and A. baumannii (MIC = 0.44 and 0.48 μg/mL, respectively) and exhibited a two-fold increase in the potency compared to the standard Ketoconazole against the C. albicans200 (MIC = 0.22 and 0.24 μg/mL, respectively). Additionally, pyrazolo-thiazolin-4-one derivatives 4a and 5a displayed MIC values of 0.45 and 0.43 μg/mL, respectively, close to that of Ketoconazole (MIC = 0.49 μg/mL) against the C. albicans100. Furthermore, 1,5-dimethylpyrazol-3-one incorporating thiazolin-4-one derivatives 10 and 13 demonstrated a good antibacterial activity against the Gram-negative bacteria used in this study with MIC values 0.43–0.98 μg/mL and against Gram-positive bacteria with MIC = 0.95–0.98 μg/mL compared with Ciprofloxacin (0.46–0.49 μg/mL). All the remaining derivatives demonstrated promising to moderate antimicrobial activity. It was interesting to show the antimicrobial activity of the tested derivatives considered as bactericidal or fungicidal depending on whether the MBC or MFC is not more than four-fold the MIC value.43,44 Regarding the MBC and MFC, our pyrazole derivatives had prominent MBC/MIC and MFC/MIC that were approximately ≤4, indicating their bactericidal/fungicidal effect.

Table 2. MIC Values in μg/mL and Ratios (MBC/MIC or MFC/MIC) of the Most Potent Pyrazole Derivatives 4a, 5a, 7b, 10, and 13 and Positive Controls (CIP and KCA) against the Tested Pathogensa.

| MIC (mean

± SEM) (μg/mL) (MBC/MIC or

MFC/MIC) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gram + ve bacteria |

Gram -ve bacteria |

fungi |

||||||

| Cpd. No. | S. aureus | S. epidermidis | B. subtilis | E. coli | A. baumannii | K. pneumoniae | C. albicans100 | C. albicans200 |

| 4a | 0.43 ± 0.4 (0.5) | 0.48 ± 0.2 (1) | 0.45 ± 0.5 (0.5) | 0.45 ± 0.2 (0.5) | 0.44 ± 0.3 (1) | 0.49 ± 0.1 (0.5) | 0.45 ± 0.3 (1) | 0.22 ± 0.2 (0.5) |

| 5a | 0.48 ± 0.1 (1) | 0.49 ± 0.4 (0.5) | 0.49 ± 0.2 (1) | 0.46 ± 0.3 (1) | 0.48 ± 0.5 (0.5) | 0.46 ± 0.2 (1) | 0.43 ± 0.5 (0.5) | 0.24 ± 0.4 (1) |

| 7b | 0.22 ± 0.3 (0.5) | 0.24 ± 0.2 (0.5) | 0.23 ± 0.6 (1) | 0.23 ± 0.1 (0.5) | 0.24 ± 0.1 (1) | 0.25 ± 0.5 (1) | 0.25 ± 0.2 (1) | 0.23 ± 0.3 (0.5) |

| 10 | 0.95 ± 0.2 (1) | 0.97 ± 0.4 (1) | 0.98 ± 0.1 (2) | 0.46 ± 0.4 (1) | 0.45 ± 0.3 (0.5) | 0.45 ± 0.2 (1) | 0.95 ± 0.3 (2) | 0.47 ± 0.1 (1) |

| 13 | 0.98 ± 0.2 (1) | 0.99 ± 0.3 (1) | 0.98 ± 0.5 (2) | 0.49 ± 0.2 (0.5) | 0.43 ± 0.3 (0.5) | 0.98 ± 0.4 (2) | 0.99 ± 0.2 (2) | 0.98 ± 0.3 (2) |

| CIP | 0.48 ± 0.1 (1) | 0.47 ± 0.2 (1) | 0.48 ± 0.3 (1) | 0.46 ± 0.4 (0.5) | 0.47 ± 0.2 (0.5) | 0.49 ± 0.5 (1) | NA | NA |

| KCA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.49 ± 0.3 (1) | 0.45 ± 0.3 (0.5) |

SEM: standard error mean; each value is the mean of three values; CIP: Ciprofloxacin; KCA: Ketoconazole; NA: non-applicable.

2.2.3. Staphylococcus Biofilm Mass Reduction

Biofilms formed by bacterial pathogens are one of the major health problems. They are life-threatening blood infections associated with both high morbidity and mortality rates, as well as high treatment costs.45S. aureus and S. epidermidis are responsible mostly for several invasive infections due to their capability to form biofilms. What worsens the case is that the traditional antibiotics are not effective enough to disrupt the biofilms due to their high resistance to most agents. It becomes essential to develop new antimicrobials capable of disrupting these biofilms and therefore overcome the increasing resistance.46

In our study, the ability of the potent pyrazole derivatives to reduce the biofilm formation was analyzed, and the findings are illustrated in Figure 2. The data obtained confirmed that the most promising pyrazole derivatives 4a, 5a, 7b, 10, and 13 all significantly disrupted the biofilm-forming Staphylococcal isolates at their MIC, reducing the S. aureus biofilm formation by 74.3, 89.1, 67, 55.6, and 51.2%, respectively. At the same time, the S. epidermidis biofilm formations were reduced by 64.8, 79.5, 58, 53.3, and 47.8%, respectively. These pyrazole derivatives showed superior antibiofilm activity to the reference antibiotic, Ciprofloxacin, by 43.2% for S. aureus and 38% for S. epidermidis.

Figure 2.

Reduction % of biofilm-forming S. aureus and S. epidermidis by the potent compounds 4a, 5a, 7b, 10, and 13 compared with Ciprofloxacin.

2.2.4. Single-Step Resistance Assessment

Upon confirming the rapid -cidal activities of pyrazole derivatives 4a, 5a, 7b, 10, and 13 against the different pathogenic isolates tested, it was essential to assess the probability of these pathogens to develop resistance to these compounds. Table 3 presents the mutation frequencies produced against each tested agent. Interestingly, thiophene-3-carboxylate derivative 7b showed a mutation frequency range from 1.34 × 10–6 to 1.67 × 10–7 compared with Ciprofloxacin (2.82 × 10–7 to 3.31 × 10–9) and Ketoconazole (3.19 × 10–8 to 3.42 × 10–9). Additionally, the mutation frequency of the most active derivatives ranged as follows: for 4a (1.58 × 10–7 to 1.54 × 10–9), for 5a (2.21 × 10–7 to 2.71 × 10–8), for 10 (2.41 × 10–8 to 3.50 × 10–8), and for 13 (2.71 × 10–7 to 2.92 × 10–9).

Table 3. Single-Step Resistance Frequencies for Thiazole-Pyrazole Compounds 4a, 5a, 7b, 10, and 13, Ciprofloxacin, and Ketoconazole against Clinical Pathogenic Isolatesa.

| Gram +ve

bacteria |

Gram -ve bacteria |

fungi |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cpd. No. | S. aureus | S. epidermidis | B. subtilis | E. coli | A. baumannii | K. pneumoniae | C. albicans100 | C. albicans200 |

| 4a | 1.61 × 10–7 | 2.43 × 10–7 | 2.20 × 10–8 | 1.20 × 10–9 | 1.00 × 10–9 | 1.54 × 10–9 | 1.40 × 10–8 | 1.58 × 10–7 |

| 5a | 3.22 × 10–7 | 2.71 × 10–8 | 2.93 × 10–7 | 2.21 × 10–7 | 1.80 × 10–8 | 1.90 × 10–8 | 2.10 × 10–8 | 4.40 × 10–7 |

| 7b | 1.34 × 10–6 | 1.62 × 10–6 | 1.30 × 10–7 | 1.90 × 10–6 | 2.11 × 10–6 | 1.67 × 10–7 | 2.51 × 10–6 | 3.10 × 10–6 |

| 10 | 2.41 × 10–8 | 3.00 × 10–8 | 3.50 × 10–8 | 2.60 × 10–8 | 2.53 × 10–8 | 2.61 × 10–8 | 3.33 × 10–8 | 3.50 × 10–8 |

| 13 | 2.73 × 10–8 | 4.15 × 10–8 | 1.66 × 10–9 | 2.90 × 10–8 | 2.71 × 10–7 | 3.22 × 10–8 | 2.92 × 10–9 | 3.20 × 10–8 |

| CIP | 2.17 × 10–8 | 3.62 × 10–9 | 5.22 × 10–8 | 2.82 × 10–7 | 3.40 × 10–7 | 3.31 × 10–9 | NA | NA |

| KCA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 3.42 × 10–9 | 3.19 × 10–8 |

CIP: Ciprofloxacin; KCA: Ketoconazole; NA: non-applicable.

2.2.5. Synergistic Effect

The extensive use of antibiotics increases the rate of resistance to pathogens. The combination therapy of commercially used antibiotics with other antimicrobials has been used in the medical system to reduce the emergence of resistant isolates to these antibiotics.47 The most potent pyrazole derivatives 4a, 5a, 7b, 10, and 13 were further evaluated to act as an adjunct to potentiate a reduction in the MIC of Ciprofloxacin and Ketoconazole against the clinical isolates. A checkerboard dilution assay has been used to determine the active compounds’ fractional inhibitory concentration index (FICI). A ΣFICI ≤ 0.5 indicates synergism between the antibiotic and the compound and shows partial synergism if greater than 0.5 and less than 1.

As shown in Table 4, we observed the ΣFICI range from 0.25 to 0.75 in the drug combinations reported, indicating synergistic and partial synergistic effects between the compounds and the reference antibiotics. There was a substantial reduction in the MIC of both Ciprofloxacin and Ketoconazole against the pathogenic bacteria and fungi. Three compounds 4a, 5a, and 7b exhibited synergistic relationships with Ciprofloxacin and Ketoconazole against all the tested pathogens with ΣFICI ≤ 0.5 ranging from 0.25 and 0.5 able to re-sensitize the pathogenic isolates to antibiotics, reducing their MICs. The N-(1H-pyrazol-4-yl)-2-(4-oxo-4,5-dihydrothiazol-2-yl)acetamide derivative 10 has behaved synergistically with Ciprofloxacin against S. aureus, E. coli, and A. baumannii and with Ketoconazole against C. albicans200. Also, the synergistic effect was observed between compound 13 and Ciprofloxacin against A. baumannii and with Ketoconazole against the two Candida isolates.

Table 4. Synergistic Effects of Compounds 4a, 5a, 7b, 10, and 13 with Antibiotics Ciprofloxacin and Ketoconazole against the Different Pathogensa.

| fractional

inhibitory concentration index (FICI)/effect |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gram +ve

bacteria |

Gram -ve bacteria |

fungi |

||||||

| Cpd. No. | S. aureus | S. epidermidis | B. subtilis | E. coli | A. baumannii | K. pneumoniae | C. albicans100 | C. albicans200 |

| 4a | 0.25/S | 0.5/S | 0.5/S | 0.25/S | 0.25/S | 0.5/S | 0.5/S | 0.5/S |

| 5a | 0.5/S | 0.5/S | 0.25/S | 0.5/S | 0.5/S | 0.25/S | 0.25/S | 0.5/S |

| 7b | 0.25/S | 0.25/S | 0.5/S | 0.5/S | 0.25/S | 0.5/S | 0.5/S | 0.25/S |

| 10 | 0.5/S | 0.75/P | 0.75/P | 0.5/S | 0.5/S | 0.75/P | 0.75/P | 0.5/S |

| 13 | 0.75/P | 0.75/P | 0.75/P | 0.75/P | 0.5/S | 0.75/P | 0.5/S | 0.5/S |

S: synergism; P: partial synergism.

2.2.6. Hemolytic Assay

The development of new antimicrobial agents requires the assurance of their safety to be used. Many compounds can be biologically active, but they also can exert several toxic effects such as hemolysis (i.e., rupture the RBCs), causing damage to vital organs such as the kidney, liver, and heart.48,49

In our study, the results of the hemolytic activity of the five active compounds 4a, 5a, 7b, 10, and 13 in Table 5 rendered that they were nontoxic with low hemolytic activity. Compound 7b was the least cytotoxic due to its lowest hemolytic activity (3.23%) relative to standard Triton X-100 with 95.12% as the positive control. Compounds 4a and 5a showed hemolytic activities of 7.55 and 9.67%, respectively. For compound 10, hemolysis was observed with %lysis of 11.66, while compound 13 showed a %lysis of 15.22. CIP and KCA showed RBCs hemolysis of 16.2 and 15.38%, respectively. The lowest hemolytic activity of the active derivatives can be attributed to the position of the different functional groups that might impact the hemolytic effect. It has been postulated that the electron-withdrawing and electron-donating nature of the attached groups could affect the hemolytic activity of different compounds.50

Table 5. Hemolytic Activity of Synthesized Compound.

| Cpd. No. | %lysis of RBCs |

|---|---|

| 4a | 7.55 ± 0.63 |

| 5a | 9.67 ± 0.31 |

| 7b | 3.23 ± 0.58 |

| 10 | 11.66 ± 0.231 |

| 13 | 15.22 ± 0.43 |

| CIP | 16.2 ± 0.5 |

| KCA | 15.38 ± 0.32 |

| Triton X-100 | 95.12 ± 0.721 |

2.2.7. Inhibitory Effects against DNA Gyrase and DHFR Enzymes

The most active pyrazole derivatives 4a, 5a, 7b, 10, and 13 were evaluated for their inhibitory activities, and their mechanisms against DNA gyrase and DHFR enzymes were explored compared with Ciprofloxacin and Trimethoprim. The obtained results are depicted as IC50 values of enzyme inhibition in μM in Table 6.

Table 6. In Vitro Inhibitory Activities of the Screened Compounds 4a, 5a, 7b, 10, and 13 against DNA Gyrase and DHFR Enzymesa.

| IC50 (mean ± SEM) (μM) |

||

|---|---|---|

| Cpd. No. | DNA gyrase | DHFR |

| 4a | 18.25 ± 0.67 | 0.98 ± 0.11 |

| 5a | 22.13 ± 0.30 | 1.11 ± 0.15 |

| 7b | 12.27 ± 0.34 | 0.52 ± 0.20 |

| 10 | 28.88 ± 0.12 | 1.42 ± 0.23 |

| 13 | 31.64 ± 0.17 | 2.67 ± 0.14 |

| CIP | 47.68 ± 0.17 | |

| TMP | 5.16 ± 0.23 | |

SEM: standard error mean; each value is the mean of three values; DHFR: dihydrofolate reductase; CIP: Ciprofloxacin; TMP: Trimethoprim.

The order of the inhibitory activity of the most active derivatives against DNA gyrase and DHFR can be represented as 7b > 4a > 5a > 10 > 13. All of the most active derivatives exhibited DNA gyrase inhibitory potential with IC50 values ranging between 12.27 ± 0.34 and 31.64 ± 0.17 μM, lower than Ciprofloxacin (IC50 = 47.68 ± 0.17 μM). Also, the promising pyrazole derivatives displayed inhibitory activity against DHFR with IC50 values 0.52 ± 0.20 to 2.67 ± 0.14 μM, lower than Trimethoprim (IC50 = 5.16 ± 0.23 μM). As shown in Table 6, pyrazole derivatives 4a and 7b proved to be the highest active inhibitors with IC50 values 18.25 and 12.27 μM for DNA gyrase and with IC50 values of 0.98 and 0.52 μM for DHFR, respectively. However, compounds 5a and 10 revealed a moderately high inhibitory activity for DNA gyrase (IC50 = 22.13 and 28.88 μM, respectively) and moderate inhibitory activity for DHFR with IC50 of 1.11 and 1.42 μM, respectively. Moreover, compound 13 expressed a DNA gyrase inhibitory activity with an IC50 of 31.64 μM and a DHFR inhibitory activity with an IC50 of 2.67 μM.

Finally, the above results confirmed the validity of our design, and the hybridization of pyrazole derivatives containing thiazol-4-one or thiophene could result in compounds with excellent antibacterial activities.

2.2.8. In Vitro Cytotoxic Activity on Normal Cell Lines

In order to evaluate the safety of the five synthesized active compounds 4a, 5a, 7b, 10, and 13 toward the normal cells, in vitro cytotoxic activity evaluation was carried out on three normal noncancerous cell lines (BNL, Vero, and H9C2) to investigate the toxicity and selectivity of these new derivatives, as presented in Table 7. To our delight, the five compounds were found to be noncytotoxic with IC50 values > 60 μM to the three normal cell lines. The most active pyrazole derivatives revealed nontoxic activity with IC50 value ranges of 79.53–103.49 μM, 70.06–86.93 μM, and 61.58–103.3 μM against the three normal cell lines, namely, mouse normal liver cells (BNL), green monkey kidney (Vero), and rat heart/myocardium (H9C2), respectively. Furthermore, compounds 7b and 4a showed the highest IC50 values for the three cell lines with selectivity index (SI) against DNA gyrase (8.41and 5.44) against BNL, (6.42 and 4.76) against Vero, and (8.28 and 5.66) against H9C2. Additionally, the two active derivatives 4a and 7b displayed the highest SI against DHFR, 101.44 and 198.65, 88.70 and 151.61, and 105.40 and 195.44 against the three noncancer cell lines (BNL, Vero, and H9C2), respectively. The order of safety and selectivity of these derivatives can be ordered as 7b > 4a > 5a > 10 > 13. Finally, the effect of the five derivatives on the noncancerous cells revealed a large safety margin on the normal cells, as shown by their SI values (Table 7).

Table 7. In Vitro Cytotoxicity (IC50 and SI) of Active Compounds 4a, 5a, 7b, 10, and 13 against Normal Noncancerous Cell Linesc.

| IC50 (μM ± S.D)

and SI against DNA gyrase and DHFR |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BNL |

Vero |

H9C2 |

|||||||

| Cpd. No. | IC50 | SIa | SIb | IC50 | SIa | SIb | IC50 | SIa | SIb |

| 4a | 99.42 ± 1.04 | 5.44 | 101.44 | 86.93 ± 0.97 | 4.76 | 88.70 | 103.3 ± 1.50 | 5.66 | 105.40 |

| 5a | 103.49 ± 1.44 | 4.67 | 93.23 | 80.24 ± 1.79 | 3.62 | 72.28 | 99.21 ± 2.29 | 4.48 | 89.37 |

| 7b | 103.30 ± 1.51 | 8.41 | 198.65 | 78.84 ± 1.10 | 6.42 | 151.61 | 101.63 ± 1.39 | 8.28 | 195.44 |

| 10 | 98.9 ± 1.54 | 3.42 | 69.64 | 70.06 ± 0.34 | 2.42 | 49.33 | 99.78 ± 1.84 | 3.45 | 70.26 |

| 13 | 79.53 ± 1.67 | 2.51 | 29.78 | 74.82 ± 2.12 | 2.36 | 28.02 | 61.58 ± 1.64 | 1.94 | 23.06 |

Selectivity index against DNA gyrase.

Selectivity index against DHFR.

S.D.: standard deviation, each value is the mean of three values; BNL: mouse normal liver cells; Vero: green monkey kidney; H9C2: rat heart/myocardium; selectivity index = (IC50 of normal cell)/(IC50 of DNA gyrase or DHFR).

2.2.9. Time-Kill Kinetic Assay

Determination of the time-kill kinetics of the synthesized compounds is essential to evaluate the efficacy and killing rate of these antimicrobial agents. The time-kill kinetic profiles of pyrazole derivative 7b displayed bactericidal and fungicidal activities toward all the pathogenic isolates tested, showing ≥3log10 reduction in the viable cell count relative to the initial inoculum with the reference antibiotics (Figures 3 and 4). The bacterial cells of S. aureus, E. coli, and A. baumannii were rapidly reduced at 2 × MIC after 8, 4, and 8 h, respectively, and after 12 h for S. epidermidis, B. subtilis, and K. pneumoniae. For C. albicans100 and C. albicans200, the maximum killing rate was observed after 16 h, respectively. The maximum reduction in the viable cell counts was observed with Ciprofloxacin at the MIC after 20, 24, 24, 12, 24, and 20 h for S. aureus, S. epidermidis, B. subtilis, E. coli, A. baumannii, and K. pneumoniae, respectively. Alternatively, the reduction in the colony-forming units was detected against C. albicans100 and C. albicans200 with Ketoconazole after 48 h. At 1/2 × MIC, only S. aureus and E. coli showed a maximum reduction after 24 h. Contrariwise, the remaining bacterial isolates and C. albicans200 showed continuous growth up to 24 h. Also, it was noticed that Candida albicans100 showed growth reduction after 24 h followed by an increase after 48 h.

Figure 3.

In vitro time-kill evaluation of (a) 7b and (b) CIP against clinical bacterial isolates at 2 × MIC.

Figure 4.

In vitro time-kill evaluation of (a) 7b and (b) KCA against clinical Candida isolates at 2 × MIC.

2.2.10. Effect of Gamma Sterilization on the Antimicrobial Activity of the Active Compound

Gamma radiation is considered a conventional sterilization method for a wide range of pharmaceuticals either in their dry form or as raw materials.51 It has been reported that gamma radiation doses up to 25.0 kGy were sufficient to sterilize the pharmaceutical products without causing any physico/chemical changes.52 The active pyrazole derivative 7b was exposed to an array of gamma irradiation doses ranging from 1.0 to 20.0 kGy. The data obtained revealed that the gamma irradiation dose of 15.0 kGy was the minimum adequate dose to sterilize the target compound, i.e., yield SAL < 10–6. Table 8 shows that the antimicrobial activity of the derivative tested remained unchanged at gamma irradiation doses 1.0 and 5.0 kGy. Contrariwise, the activity was increased at gamma doses of 10.0, 15.0, and 20.0 kGy.

Table 8. In Vitro Antimicrobial Activity of Compound 7b Expressed as MIC in μg/mL before and after Radiationa.

| gamma radiation doses in kGy MIC (mean ± SEM) (μg/mL) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| microorganisms | 0 | 1 | 5 | 10 | 15 | 20 |

| S. aureus | 0.22 ± 0.3 | 0.22 ± 0.2 | 0.22 ± 0.3 | 0.123 ± 0.3 | 0.124 ± 0.2 | 0.124 ± 0.4 |

| S. epidermidis | 0.24 ± 0.2 | 0.24 ± 0.3 | 0.24 ± 0.4 | 0.124 ± 0.5 | 0.124 ± 0.3 | 0.123 ± 0.5 |

| B. subtilis | 0.23 ± 0.6 | 0.23 ± 0.4 | 0.23 ± 0.5 | 0.124 ± 0.4 | 0.124 ± 0.6 | 0.124 ± 0.3 |

| E. coli | 0.23 ± 0.1 | 0.23 ± 0.2 | 0.23 ± 0.1 | 0.122 ± 0.2 | 0.122 ± 0.5 | 0.123 ± 0.3 |

| A. baumannii | 0.24 ± 0.1 | 0.24 ± 0.1 | 0.24 ± 0.1 | 0.123 ± 0.1 | 0.124 ± 0.3 | 0.124 ± 0.5 |

| K. pneumoniae | 0.25 ± 0.5 | 0.25 ± 0.5 | 0.25 ± 0.2 | 0.123 ± 0.3 | 0.125 ± 0.2 | 0.125 ± 0.3 |

| C. albicans100 | 0.25 ± 0.2 | 0.25 ± 0.2 | 0.25 ± 0.2 | 0.124 ± 0.5 | 0.125 ± 0.4 | 0.125 ± 0.4 |

| C. albicans200 | 0.23 ± 0.3 | 0.23 ± 0.3 | 0.23 ± 0.2 | 0.123 ± 0.2 | 0.125 ± 0.1 | 0.125 ± 0.2 |

SEM: standard error mean; each value is the mean of three values.

2.3. Molecular Docking Study

Owing to the favorable results obtained by previous studies, molecular docking simulation of the most promising derivatives 4a, 5a, 7b, 10, and 13 were performed inside the active sites of S. aureus DNA gyrase (PDB: 2XCT) and dihydrofolate reductase (PDB: 1DLS).53 The docking process was performed using Molecular Operating Environmental (MOE) 10.2008.54,55 Results obtained from the docking study are presented in Table 9 and Figures 5a,b, 6, and 7a,b. These results exhibited that the most promising pyrazole-thiazol-4-one or pyrazole-thiophene derivatives can recognize the active site of the protein and make different types of interactions (H-bond, arene–cation, and arene–arene) with the key amino acids in the active site of the pocket.

Table 9. Molecular Docking Study of the Most Promising Derivatives 4a, 5a, 7b, 10, and 13 inside the Active Sites of S. aureus DNA Gyrase (PDB: 2XCT) and Dihydrofolate Reductase (PDB: 1DLS)a.

| Docking inside the S. aureus DNA Gyrase (PDB: 2XCT) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cpd. No. | S (Kcal/mol) | residue | interacting groups | distance (Å) | strength (%) |

| 4a | –18.90 | Arg1048 | nitrogen of a cyano group | 3.11 | 26 |

| His1081 | phenyl at C3 of pyrazole | - | - | ||

| 5a | –17.39 | Lys1043 | carbonyl of thiazolinone | 2.73 | 41 |

| Arg1092 | phenyl of aldehyde | - | - | ||

| Arg1033 | phenyl at C3 of pyrazole | - | - | ||

| 7b | –20.68 | Lys1043 | nitrogen of pyrazole | 3.14 | 16 |

| Glu1088 | NH2 of thiophene | 2.98 | 41 | ||

| Arg1092 | phenyl at N1 of pyrazole | - | - | ||

| 10 | –16.74 | His1079 | carbonyl of thiazolinone | 2.74 | 41 |

| Lys1043 | carbonyl of acetamide | 2.58 | 32 | ||

| Lys1043 | carbonyl of acetamide | 2.69 | 33 | ||

| Arg1092 | phenyl at N1 of pyrazole | - | - | ||

| 13 | –16.40 | Lys1043 | carbonyl of pyrazole | 2.72 | 16 |

| Gln1267 | nitrogen of a cyano group | 3.43 | 12 | ||

| Ile1175 | carbonyl of thiazolinone | 3.05 | 12 | ||

| CIP | –10.58 | His1081 | oxygen of carboxylate | 2.30 | 37 |

| Tyr580 | nitrogen of piprazine | 2.35 | 48 | ||

| Docking inside the Active Site of Dihydrofolate Reductase (PDB: 1DLS) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cpd. No. | S (Kcal/mol) | residue | interacting groups | distance (Å) | strength (%) |

| 4a | –19.74 | Trp24 | carbonyl of thiazolinone | 2.60 | 27 |

| Ala9 | nitrogen of a cyano group | 2.72 | 86 | ||

| 5a | –18.83 | Val115 | hydroxy group | 2.47 | 30 |

| Phe31 | pyrazole ring | -- | -- | ||

| 7b | –20.17 | Ile7 | NH2 of a thiophene moiety | 3.07 | 11 |

| Val115 | NH2 of a thiophene moiety | 2.75 | 47 | ||

| 10 | –16.21 | Asn64 | carbonyl of acetanilide | 2.80 | 22 |

| Phe34 | phenyl at N1 of pyrazole | -- | -- | ||

| 13 | –15.46 | Tyr121 | nitrogen of a cyano group | 3.11 | 23 |

| Phe31 | phenyl at N1 of pyrazole | -- | -- | ||

| TMP | –19.92 | Val115 | amino of a pyrimidine derivative | 2.85 | 24 |

| Glu30 | amino of a pyrimidine derivative | 2.49 | 30 | ||

| Ser59 | oxygen of a methoxy group | 2.94 | 38 | ||

| MTX | –23.47 | Arg70 | C=O of carboxylate oxygen of carboxylate oxygen of carboxylate | 2.96 | 36 |

| Arg70 | 2.35 | 60 | |||

| Asn64 | 2.92 | 32 | |||

| Arg28 | C=O of carboxylate | 2.91 | 17 | ||

| Asn64 | C=O of amide | 2.49 | 20 | ||

| Val115 | NH2 of pyrimidine | 2.75 | 35 | ||

| Lle7 | NH2 of pyrimidine | 3.16 | 13 | ||

| Gln30 | NH2 of pyrimidine | ||||

| Phe34 | pyrazine ring | 2.83&2.7 | 39&63 | ||

| -- | -- | ||||

CIP = Ciprofloxacin, MTX = Methotrexate, TMP: Trimethoprim; (-) arene–cation interaction, (--) arene–arene interaction.

Figure 5.

(a) 2D and 3D binding mode of compound 7b inside the active site of DNA gyrase (2XCT). (b) 2D and 3D binding mode of compound 5b inside the active site of DNA gyrase (2XCT).

Figure 6.

2D and 3D binding mode of compound 4a inside the active site of DHFR (1DLS)

Figure 7.

(a) 2D and 3D binding mode of compound 10 inside the active site of DHFR (1DLS). (b) 2D and 3D binding mode of compound 7b inside the active site of DHFR (1DLS).

First, the most active derivatives 4a, 5a, 7b, 10, and 13 displayed binding energies from S = −16.40 Kcal/mol to S = −20.68 Kcal/mol compared to Ciprofloxacin having S = −10.58 Kcal/mol. The 4-amino-2-(1-phenyl-3-(p-tolyl)-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)thiophen derivative 7b showed the lowest binding energy S = −20.68 Kcal/mol through one hydrogen bond donor between Glu1088 and amino of thiophene (bond length = 3.14 Å), a hydrogen bond acceptor between Lys1043 and nitrogen of pyrazole derivatives (bond length = 2.98 Å), and arene–cation interaction between Arg1092 and phenyl at N1 of the pyrazole moiety Figure 5a.

Additionally, 3-(1H-pyrazol-4-yl)-2-(4-oxo-4,5-dihydrothiazol-2-yl)acrylonitrile derivative 4a revealed a good binding energy S = −18.90 Kcal/mol through one hydrogen bond sidechain acceptor with Arg1048 with a bond length 3.11 Å and strength 26%. Additionally, the residue His1081 formed an arene–cation interaction with a phenyl ring at C3 of pyrazole in compound 4a, as described in Figure 5b.

On the other hand, pyrazolo-thiazolin-4-one derivative 5a demonstrated a binding energy S = −17.39 Kcal/mol through only one hydrogen bond sidechain acceptor between the residue Lys1043 and carbonyl of thiazoline-4-one. (All figures of the docking study are shown in the Supporting Information).

In addition, N-(1H-pyrazol-4-yl)-2-(4-oxo-4,5-dihydrothiazol-2-yl)acetamide derivative 10 exhibited a binding energy S = −16.74 Kcal/mol through three hydrogen bond sidechain acceptors with His1079 and Lys1043 and one arene–cation interaction between Arg1092 with phenyl at N1 of the pyrazole moiety. Furthermore, N-(1H-pyrazol-4-yl)-4-oxo-4,5-dihydrothiazole-2-carbohydrazonoyl derivative 13 demonstrated the lowest binding energy S = −16.74 Kcal/mol through two hydrogen bond sidechain acceptors between Lys1043 and carbonyl of pyrazole derivatives and Gln1267 with the nitrogen of the cyano group with bond lengths 2.72 Å (strength = 16%) and 3.43 Å (strength = 12%), respectively. In addition, there is one hydrogen bond backbone acceptor between Ile1175 with the carbonyl of the thiazolin-4-one core with a bond length 3.05 Å (strength = 12%). (All figures for the docking study are shown in the Supporting Information).

On the other hand, to study the activity of the most promising derivatives 4a, 5a, 7b, 10, and 13 against the DHFR enzyme, a molecular docking study inside the active site of dihydrofolate reductase (PDB: 1DLS) was performed. Trimethoprim as another positive control (used in the in vitro study) displayed a binding energy S = −19.92 Kcal/mol through a two hydrogen bond donors between the residue Val115 and amino group at position four in the pyrimidine ring (backbone donor) with a bond length 2.85 Å and strength 24%, in addition to the residue Glu30 and the other amino group at position two in the pyrimidine ring (side chain donor) with a bond length 2.49 Å and strength 30%. Also, there is one hydrogen bond sidechain acceptor between Ser59 and oxygen of a methoxy group with a bond length 2.94 Å and strength 38%. (All figures are shown in the SI).

The most promising derivatives 4a, 5a, 7b, 10, and 13 exhibited a good binding energy from S = −20.17 Kcal/mol to S = −15.46 Kcal/mol with different types of interactions in comparison to Methotrexate having S = −23.47 Kcal/mol and Trimethoprim having S = −19.92 Kcal/mol. 3-(1H-Pyrazol-4-yl)-2-(4-oxo-4,5-dihydrothiazol-2-yl)acrylonitrile derivative 4a displayed a binding energy score S = −19.74 Kcal/mol. Additionally, compound 4a fitted inside the active site through two hydrogen bond sidechain acceptors between Trp24 with the carbonyl of thiazolin-4-one and Ala9 with the nitrogen of a cyano group with bond lengths 2.60 and 2.72 Å as well as hydrophobic interaction that appears on phenyl of the pyrazole scaffold and cyano group Figure 6. Moreover, the docking results of 2-(5-((1H-pyrazol-4-yl)methylene)-4-oxo-4,5-dihydro-thiazol-2-yl)acrylonitrile derivative 5a and N-(1H-pyrazol-4-yl)-2-(4-oxo-4,5-dihydrothiazol-2-yl)acetamide derivative 10 exhibited binding energies S = −18.83 and −16.21 Kcal/mol with one hydrogen bond and arene–arene interactions, respectively. The interaction of compound 10 inside the active site of DHFR (PDB: 1DLS) is presented in Figure 7a. Meanwhile, the thiophene derivative 7b revealed an interesting interaction with a binding energy S = – 20.17 Kcal/mol by its ability to form two hydrogen bond sidechain acceptors between Ile7 and Val115 with the amino of thiophene with bond lengths 3.07 and 2.75 Å, respectively (Figure 7b). Also, the N-(1H-pyrazol-4-yl)-4-oxo-4,5-dihydrothiazole-2-carbohydrazonoyl derivative 13 showed a binding energy S = −15.46 Kcal/mol through one hydrogen bond sidechain acceptor between Tyr 121 with the nitrogen of a cyano group with a bond length 3.11 Å and strength 23%, as well as the arene–arene interaction between Phe31 and phenyl of a pyrazole ring.

Finally, the docking results confirmed the validity of the most promising derivatives 4a, 5a, 7b, 10, and 13 against DNA gyrase and dihydrofolate reductase. In addition, the hybridization of thiazol-4-one or thiophene with pyrazole could improve the antibacterial activities with a lower binding energy and through different types of interactions such as hydrogen bonds and arene–arene and arene–cation interactions with bond lengths not exceeding 3.43 Å.

3. Conclusions

We herein reported a novel route for synthesizing some new pyrazole derivatives containing thiazol-4-one/thiophene. The newly synthesized derivatives are based on the reaction of 1,3-diaryl-4-formyl pyrazole or 4-amino antipyrine derivatives with different chemical reagents. The formyl pyrazole derivatives 2a and 2b were condensed with thiazolidine-4-one derivatives 1a and 1b to form 5-arylmethylidine derivatives 3a and 3b that reacted with the further aromatic aldehyde to produce bis-aryl methylidene derivatives 5a and 5c. The pyrazolo-arylidene derivatives 6a–d reacted with sulfanylacetic acid to produce thiazoline-4-one 4a and 4b and thiophene derivatives 7a and 7b depending on the active methylene of arylidene. Further, 4-aminoantipyrine was used as a precursor substance for the synthesis of thiazolo-pyrazole 10, 13, 14, 15a, and 15b depending on the conversion of the amino group by cyanoacylation or diazotization and then reacted with sulfanylacetic acid. Also, this article includes the synthesis of some thiazolo[3,2-a]pyridine derivatives 16a and 16b that were designed and synthesized by reacting the mono- and bis-aryl methylidene derivatives 14 and 15a and 15b with arylidene-malononitrile or malononitrile, respectively. Additionally, all the synthesized analogs were examined for their in vitro antimicrobial activities against eight isolate pathogens. Among them, five pyrazole derivatives 4a, 5a, 7b, 10, and 13 revealed the ability to inhibit the growth of the screened panel of eight isolates with excellent MICs and MBCs/MFCs values compared with Ciprofloxacin and Ketoconazole with a low resistance rate and potential for resistance. Moreover, the in vitro inhibitory activity for the biofilm formation illustrated these derivatives as the most potent biofilm inhibitors compared with the reference drugs against two strains, S. aureus and S. epidermidis. Furthermore, the most active derivatives 4a, 5a, 7b, 10, and 13 showed synergistic effects when combined with Ciprofloxacin and Ketoconazole, reducing their MICs and reducing their resistance frequency. The five active compounds have low hemolytic activity compared with CIP, KCA, and Triton X-100, which makes them safe to be used as antimicrobial agents. The enzyme inhibitory activity of the active agents exhibited their significant activity against the DNA gyrase and DHFR enzymes with lower IC50 values compared with Ciprofloxacin and Trimethoprim. Moreover, all the five promising derivatives showed noncytotoxic activity against three normal noncancerous cell lines, indicating their safety margin to the normal cells. In addition, the results also showed that gamma radiation could be safely used in the sterilization of antimicrobial agents and can enhance their antimicrobial activity. Finally, the molecular docking simulation was performed inside the active site of both DNA gyrase (2XCT) and dihydrofolate reductase (1DLS) and exhibited agreement with in vitro DNA gyrase and DHFR inhibition results with low binding energy.

4. Experimental Section

4.1. Chemistry

Melting points are uncorrected. The IR spectra were recorded on a Shimadzu 440 infrared spectrophotometer (υ/cm–1) using the KBr technique (Shimadzu, Japan). 1H NMR spectra were recorded on a Varian Gemini spectrometer (δ/ppm) 300 and 400 MHz using TMS as an internal standard. Mass spectra were recorded on a Jeol-JMS-600 mass spectrometer. 13C NMR spectra were run at 75 and 101 MHz. Micro analytical data were obtained from the Micro Analytical Research Centre, Faculty of Science, Cairo University. The reactions were monitored by thin layer chromatography (TLC) using TLC sheets with UV fluorescent silica gel Merck 60f254 plates using a UV lamp and different solvents as mobile phases. 2-(4-Oxothiazolidin-2-ylidene)acetonitrile (1a) and ethyl-2-(4-oxothiazolidin-2-ylidene)acetate (1b) were prepared according to the reported method.35 Furthermore, 1,3-diphenyl-1H-pyrazole-4-carbaldehyde (2a), 1-phenyl-3-(p-tolyl)-1H-pyrazole-4-carbaldehyde (2b),37 2-cyano-N-(1,5-dimethyl-3-oxo-2-phenyl-2,3-dihydro-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)acetamide (9),41,56 and N-(1,5-dimethyl-3-oxo-2-phenyl-2,3-dihydro-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)carbonohydrazonoyldicyanide (12)42 were also prepared.

4.1.1. Synthesis of 2-(4-Oxo-5-((1-phenyl-3-(aryl)-1H-pyrazol-4-Yl)methylene)thiazolidin-2-ylidene)acetonitrile or Ethyl Acetate Derivatives (3a–d)

A mixture of 1-phenyl-3-(aryl)-1H-pyrazole-4-carbaldehyde derivatives (2a and 2b) (0.01 mol) in 20 mL of ethanol was refluxed for 2 h with thiazolidin-4-one derivatives (1a and 2b) (0.01 mol) in the presence of piperidine as a catalyst (three drops). The solid products formed were collected by filtration and recrystallized from ethanol.

4.1.2. 2-(5-((1,3-Diphenyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)methylene)-4-oxothiazolidin-2-ylidene)acetonitrile (3a)

3a was prepared according to a previously reported method.39

4.1.3. 2-(4-Oxo-5-((1-phenyl-3-(p-tolyl)-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)methylene)thiazolidin-2-ylidene)acetonitrile (3b)

Orange powder (EtOH); Yield 73%; M.p: 200–202 °C; IR (KBr, ν/cm–1): 3199 (NH), 3063 (CH-arom.), 2927 (CH-aliph.), 2202 (C≡N) and 1718 (C=O thiazolidinone), 1599 (C=N); 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ/ppm 2.34 (s, 3H,CH3), 4.96 (s, 1H, methine-H), 7.41 (t, J = 6.6 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.61 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 7.85 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 7.92 (s, 1H, methine-H), 8.03 (t, 2H, Ar-H), 8.09 (d, 2H, Ar-H), 8.78 (s, 1H, pyrazole-H), 11.99 (s, 1H, NH, exchangeable by D2O); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ/ppm 21.10 (CH3), 118.21, 118.54, 119.64, 119.80, 126.22, 126.62, 127.64, 128.18, 128.68, 128.92, 129.36, 129.68, 129.97, 137.87, 139.31, 150.29, 153.64, 162.44 (C=O); MS (EI, 70 eV): m/z (%) = 384.08 (M+) (36.90%), 283.64 (100%); Anal. Calcd. for C22H16N4OS (384.46): C, 68.73; H, 4.20; N, 14.57 Found: C, 68.23; H, 4.52, N, 15.12.

4.1.4. Ethyl 2-(5-((1,3-Diphenyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)methylene)-4-oxothiazolidin-2-ylidene)acetate (3c)

Yellow powder (EtOH); Yield 71%; M.p: 230–232 °C; IR (KBr, ν/cm–1): 3388 (NH), 3061 (CH-arom.), 2996, 2877, 2792 (CH-aliph.), 1688 (C=O thiazolidinone and ester), 1599 (C=N); 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ/ppm 1.25 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H, CH3CH2-), 4.16 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H, CH3CH2-), 5.65 (s, 1H, methine-H), 7.40 (s, 1H, methine-H), 7.45 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.55 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 7.61 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 3H, Ar-H), 7.66 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 8.01 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 8.68 (s, 1H, pyrazole-H), 12.08 (s, 1H, NH, exchangeable by D2O); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ/ppm 14.23 (CH3CH2-), 59.55 (CH3CH2-), 89.65, 115.87, 119.18, 119.26, 122.85, 127.35, 127.76, 128.35, 128.85, 129.65, 131.43, 138.80, 151.65, 153.17, 166.68 (C=O); Anal. Calcd. for C23H19N3O3S (417.48): C, 66.17; H, 4.59; N, 10.07; Found: C, 66.43; H, 4.21, N, 9.82.

4.1.5. Ethyl-2-(4-oxo-5-((1-phenyl-3-(p-tolyl)-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)methylene)thiazolidin-2-ylidene)-acetate (3d)

Yellow powder (EtOH); Yield 69%; M.p. 275–277 °C; IR (KBr, ν/cm–1): 3135 (NH), 3064 (CH-arom.), 2977, 2869 (CH-aliph.), 1686 (C=O thiazolidinone and ester), 1594 (C=N); 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ/ppm 1.25 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H, CH3CH2-), 2.40 (s, 3H, CH3), 4.17 (q, J = 7.3 Hz, 2H, CH3CH2-), 5.64 (s, 1H, methine-H), 7.36 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 7.43 (s, 1H, methine-H), 7.54 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 7.60 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 3H, Ar-H), 7.99 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 8.65 (s, 1H, pyrazole-H), 12.25 (s, 1H, NH, exchangeable by D2O); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ/ppm 14.21 (CH3CH2-), 20.81 (CH3), 59.55 (CH3CH2-), 89.59, 115.79, 118.85, 119.19, 119.32, 122.57, 123.10, 127.28, 127.63, 128.42, 128.54, 128.69, 129.40, 129.62, 130.87, 138.40, 138.80, 151.64, 153.23, 166.68 (C=O); MS (EI, 70 eV): m/z (%) = 431.52 (M+) (29.20%), 229.23 (100%); Anal. Calcd. for C24H21N3O3S (431.51): C, 66.80; H, 4.91; N, 9.74; Found: C, 66.51; H, 4.22, N, 9.63.

4.2. Synthesis of 2-(4-Oxo-4,5-dihydrothiazol-2-yl)-3-(1-,3-(diaryl)-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)acrylnitrile Derivatives (4a and 4b) and Ethyl 4-Amino-2-(1-phenyl-3-(aryl)-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)thiophene-3-carboxylate Derivatives (7a and 7b)

A mixture of 2-((1-phenyl-3-(aryl)-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)methylene)malononitrile (6a and 6b; 0.01 mol) and ethyl-2-cyano-3-(1-phenyl-3-(aryl)-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)acrylate (6c and 6d; 0.01 mol) was added to sulfanylacetic acid (0.01 mol) in 10 mL of DMF that contains piperidine (0.5 mL), and finally, the reaction mixture was heated under reflux for 2–4 h. The solid products formed were collected by filtration and recrystallized from ethanol.

4.2.1. 3-(1,3-Diphenyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)-2-(4-oxo-4,5-dihydrothiazol-2-yl)acrylonitrile (4a)

Brown powder (EtOH); Yield: 67%; M.p.: 100–102 °C; IR (KBr, ν/cm–1): 3057 (CH-arom.), 2978 (CH-aliph.), 2202 (C≡N) and 1714 (C=O thiazolino-4-one), 1598 (C=N); 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ/ppm 4.72 (s, 2H, CH2), 7.34 (d, J = 7.50 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.42 (t, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.46 (t, 1H, Ar-H), 7.53 (t, 1H, Ar-H), 7.57 (d, J = 7.80 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.62 (t, 1H, Ar-H), 7.95 (t, 2H, Ar-H), 8.06 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 8.80 (s, 1H, methine-H), 8.86 (s, 1H, pyrazole-H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ/ppm 43.75 (CH2), 107.12, 115.22, 117.70, 118.14, 119.63, 121.00, 123.00, 126.60, 127.79, 128.58, 129.51, 131.20, 132.69, 138.90, 142.27, 147.51, 153.72, 154.76 (2C=C), 162.34 (S–C=N), 164.85 (C=O); Anal. Calcd. for C21H14N4OS (370.43): C,68.09; H, 3.81; N, 15.13 Found: C, 568.76; H, 3.43, N, 15.56.

4.2.2. 2-(4-Oxo-4,5-dihydrothiazol-2-yl)-3-(1-phenyl-3-(p-tolyl)-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)acrylonitrile (4b)

Brown powder (EtOH); Yield: 67%; M.p.: 110–112 °C ; IR (KBr, ν/cm–1): 3057 (CH-arom.), 2978 (CH-aliph.), 2210 (C≡N) and 1720 (C=O thiazolino-4-one), 1595 (C=N); 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ/ppm 2.49 (s, 3H, CH3), 4.72 (s, 2H, CH2), 7.36 (t, J = 7.35 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.49 (t, J = 7.65 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.56 (d, 1H, Ar-H), 7.63 (t, J = 7.05 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.89 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 8.00 (d, 1H, Ar-H), 8.06 (d, J = 7.80 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 8.80 (s, 1H, methine-H), 8.85 (s, 1H, pyrazole-H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ/ppm 22.73 (CH3), 44.52 (CH2), 115.19, 116.10, 117.96, 119.82, 122.39, 127.55, 128.42, 128.75, 129.55, 129.88, 130.25, 130.25, 131.17, 139.15, 143.15, 143.27, 147.46, 153.68, 164.84 (S–C=N), 169.21 (C=O); Anal. Calcd. for C22H16N4OS (384.46): C, 68.73; H, 4.20; N, 14.57; Found: C, 68.23; H, 4.52, N, 15.12.

4.2.3. Ethyl 4-Amino-2-(1,3-diphenyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)thiophene-3-carboxylate (7a)

Yellow powder (EtOH); Yield 69%; M.p. 150–152 °C; IR (KBr, ν/cm–1): 3432, 3345 (NH2), 3060 (CH-arom.), 2974, 2862 (CH-aliph.), 1685 (C=O ester), 1594 (C=N); 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ/ppm 1.30 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H, CH3CH2-), 4.31 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H, CH3CH2-), 7.48 (t, J = 7.35 Hz, 3H, Ar-H), 7.55 (s, 2H, NH2, exchangeable by D2O), 7.59 (d, 2H, Ar-H), 7.64 (t, 3H, Ar-H), 7.92 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 8.11 (s, 1H, thiophene-H), 9.16 (s, 1H, pyrazole-H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ/ppm 13.95 (CH3CH2-), 62.13 (CH3CH2-), 99.94, 114.26, 115.96, 119.67, 128.14, 128.89, 129.00, 129.43, 129.62, 129.84, 130.51, 138.40, 144.51, 145.56, 155.20 (C–NH2), 161.83 (C=O); Anal. Calcd. for C22H19N3O2S (389.47): C, 67.85; H, 4.92; N, 10.79; Found: C, 67.55; H, 5.01; N, 10.87.

4.2.4. Ethyl 4-Amino-2-(1-phenyl-3-(p-tolyl)-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)thiophene-3-carboxylate (7b)

Yellow powder (EtOH); Yield 69%; M.p. 150–152 °C; IR (KBr, ν/cm–1): 3432, 3357 (NH2), 3060 (CH-arom.), 2918, 2865 (CH-aliph.), 1686 (C=O ester), 1593 (C=N); 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ/ppm 1.30 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H, CH3CH2-), 2.39 (s, 3H, CH3), 4.31 (q, J = 6.9 Hz, 2H, CH3CH2-), 7.38 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 7.44 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 7.49 (s, 2H, NH2, exchangeable by D2O), 7.61 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 3H, Ar-H), 7.91 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 8.09 (s, 1H, thiophene-H), 9.13 (s, 1H, pyrazole-H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ/ppm 13.96 (CH3CH2-), 20.86 (CH3), 62.11 (CH3CH2-), 99.71, 114.19, 115.99, 119.62, 127.63, 128.63, 128.75, 129.55, 129.81, 138.41, 139.08, 143.83, 145.63, 155.22 (C-NH2), 161.95 (C=O); Anal. Calcd. for C23H21N3O2S (403.50): C, 68.46; H, 5.25; N, 10.41; Found C, 68.59; H, 5.03; N, 10.56.

4.3. Synthesis of Thiazolin-4-one Derivatives (5a–c)

A mixture of 5-arylmethylidine-4-thiazolidinone derivative (3a) (0.01 mol) was added to different aromatic aldehydes (0.01 mol) in 20 mL of absolute ethanol in the presence of piperidine (three drops) as a catalyst, and the reaction mixture was heated under reflux for 2–6 h. The solid products formed were collected by filtration and recrystallized from ethanol.

4.3.1. 3-(2-Hydroxyphenyl)-2-(5-((1,3-diphenyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)methylene)-4-oxo-4,5-dihydro-thiazol-2-yl)acrylonitrile (5a)

Brown powder (EtOH); Yield: 69%; M.p.: 230–232 °C; IR (KBr, ν/cm–1): 3059 (CH-arom.), 2199 (CN), 1710 (C=O thiazolin-4-one), 1598 (C=N); 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ/ppm 7.42 (d, 1H, Ar-H), 7.44 (t, 2H, Ar-H), 7.47 (d, 1H, Ar-H), 7.48 (d, 1H, Ar-H), 7.49 (d, 2H, Ar-H), 7.51 (t, 2H, Ar-H), 7.54 (t, 2H, Ar-H), 7.56 (d, 1H, Ar-H), 7.63 (t, 2H, Ar-H), 7.64, 7.94 (s, 2H, 2methine-H), 9.14 (s, 1H, pyrazole-H), 10.02 (s, 1H, OH, exchangeable by D2O), 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ/ppm 104.54, 114.46, 115.69, 116.04, 117.18, 119.15, 122.09, 127.67, 126.61, 125.89, 128.88, 128.83, 128.32, 129.16, 129.54, 129.80, 130.88, 131.42, 134.78, 136.41, 138.72, 139.20, 141.61, 152.62, 153.30 (C–OH), 154.45 (S–C=N), 162.51 (C=O); Anal. Calcd. for C28H18N4O2S (474.54): C, 70.87; H, 3.82; N, 11.81 Found: C, 70.57; H, 3.98; N, 11.95.

4.3.2. 3-(4-Chlorophenyl)-2-(5-((1,3-diphenyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)methylene)-4-oxo-4,5-dihydrothiazol-2-yl)acrylonitrile (5b)

Brown powder (EtOH); Yield: 69%; M.p.105–107 °C; IR (KBr, ν/cm–1): 3059 (CH-arom.), 2960 (CH-aliph.), 2197(CN) and 1721 (C=O thiazolino-4-one), 1596 (C=N); 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ/ppm 7.43 (d, J = 7.20 Hz, 6H, Ar-H), 7.64 (t, 4H, Ar-H), 7.95 (t, J = 7.35 Hz, 4H, Ar-H), 7.99, 8.05 (s, 2H, 2methine-H), 9.29 (s, 1H, pyrazole-H), 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ/ppm 100.01, 114.63, 115.93, 118.35, 119.27, 119.56, 122.25, 127.76, 128.61, 128.75, 128.99, 129.24, 129.40, 129.65, 129.75, 129.90, 130.81, 131.22, 131.37, 132.43, 134.87, 138.71, 138.96, 141.73, 153.54 (C=C), 154.17 (C=N), 155.74 (S–C=N), 162.62 (C=O); Anal. Calcd. for C28H17ClN4OS (492.98): C, 68.22; H, 3.48; N, 11.37; Found: C, 68.82; H, 3.76, N, 11.03.

4.3.3. 2-(5-((1,3-Diphenyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)methylene)-4-oxo-4,5-dihydrothiazol-2-yl)-3-(4-nitrophenyl)acrylonitrile (5c)

Brown powder (EtOH); Yield: 67%; M.p.: 100–102 °C; IR (KBr, ν/cm–1): 3061(CH-arom.), 2932 (CH-aliph.), 2199 (CN) and 1716 (C=O thiazolin-4-one), 1596 (C=N); 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ/ppm 7.42 (s, 1H, methine-H), 7.60 (d, J = 7.60 Hz, 4H, Ar-H), 7.65 (t, 3H, Ar-H), 7.86 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 7.96 (s, 1H, methine-H), 8.08 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H, Ar-H), 8.18 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 8.44 (s, 1H, pyrazole-H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ/ppm 110.12, 116.76, 118.35, 119.35, 119.65, 124.38, 127.61, 128.67, 128.80, 129.07, 129.30, 129.83, 130.21, 130.74, 134.26, 136.17, 138.29, 138.76, 142.69, 153.54 (C=C), 154.21 (C=N), 156.54 (S–C=N), 162.42 (C=O); Anal. Calcd. for C28H17N5O3S (503.54): C, 66.79; H, 3.40; N, 13.91 Found: C, 66.43; H, 3.71, N, 14.23.

4.3.4. N-(1,5-Dimethyl-3-oxo-2-phenyl-2,3-dihydro-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)-2-(4-oxo-4,5-dihydrothiazol-2-yl)acetamide (10)

A solution of cyanoacetamide derivative 9 (0.01 mol) in absolute ethanol (15 mL) was added to sulfanylacetic acid (0.01 mol) and the reaction mixture was heated under reflux for 8 h. The solid product formed was collected by filtration and recrystallized from ethanol.

Brown powder (EtOH); Yield 67%; M.p.:160–162 °C; IR (KBr, ν/cm–1): 3436 (NH), 3061 (CH-arom.), 2917 (CH-aliph.), 1688, 1659 (C=O), 1592 (C=N); 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ/ppm 2.19 (s, 3H, CH3), 3.08 (s, 3H, N-CH3), 3.23 (s, 2H, CH2), 4.34 (s, 2H, CH2), 7.17 (s, 1H, NH, exchangeable by D2O), 7.36 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 7.50 (t, J = 7.15 Hz, 3H, Ar-H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ/ppm 13.52 (CH3), 29.24 (N-CH3), 34.72, 35.62 (2CH2), 109.26, 119.63, 123.54, 124.50, 126.63, 128.90, 129.12, 130.32, 145.71 (S–C=N), 156.49, 162.19, 167.83 (3C=O); Anal. Calcd. for C16H16N4O3S (344.39): C, 55.80; H, 4.68; N, 16.27; Found: C, 56.12; H, 4.81, N, 15.97.

4.3.5. Synthesis of N-(1,5-Dimethyl-3-oxo-2-phenyl-2,3-dihydro-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)-4-oxo-4,5-dihydrothiazole-2-carbohydrazonoyl cyanide (13)

A mixture of N-(pyrazol-4-yl)carbonohydrazonoyldicyanide derivative (12) (0.01 mol) in absolute ethanol (20 mL) and sulfanylacetic acid (0.01 mol) having few drops of piperidine was refluxed for 8 h. The solid product formed was collected by filtration and recrystallized from ethanol/DMF.

Brown powder (EtOH/DMF); Yield: 67%; M.p.160-162C; IR (KBr, ν/cm–1): 3331 (NH), 3064 (CH-arom.), 2993 (CH-aliph.), 2217(CN), 1723 (C=O), 1594 (C=N); 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ/ppm 2.54 (s, 3H, CH3), 3.31 (s, 3H, N–CH3), 3.97 (s, 2H, CH2), 7.37 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.41 (s, 1H, NH exchangeable by D2O), 7.45 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.57 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 3H, Ar-H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ/ppm. 9.91 (CH3), 33.94 (N-CH3), 34.21 (CH2), 106.73, 113.76, 121.03, 126.38, 128.14, 128.33, 129.52, 129.74, 133.20, 149.35, 151.58 (C=N), 159.31, 174.55 (2C=O); Anal. Calcd. for C16H14N6O2S (354 .09): C,54.23; H, 3.98; N, 23.71 Found: C, 54.31; H, 4.11, N, 23.11.

4.3.6. 2-(5-(2-(1,5-Dimethyl-3-oxo-2-phenyl-2,3-dihydro-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)hydrazono)-4-oxo-4,5-dihydrothiazol-2-yl)acetonitrile (14)

A solution of thiazolidin-4-one derivative (1a) (0.01 mol) in absolute ethanol (20 mL) was added to a diazotized 4-aminoantipyrine solution (11) (0.01 mol). The mixture was stirred for 2 h at 0 °C and a further 2 h at room temperature. The solid product formed was collected by filtration and recrystallized from ethanol.

Brown powder (EtOH); Yield 70%; M.p.: 165–167 °C; IR (KBr, ν/cm–1): 3442, 3324 (2NH), 3065 (CH-arom.), 2990, 2940 (CH-aliph.), 2207(CN), 1720 (C=O), 1615 (C=N); 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ/ppm 2.54 (s, 3H, CH3), 3.31 (s, 3H, -N–CH3), 4.04 (s, 2H, CH2), 7.37 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 7.39 (s, 1H, NH exchangeable by D2O), 7.57 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 3H, Ar-H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ/ppm 11.03 (CH3), 33.76 (CH2), 34.37 (N-CH3), 111.81, 122.28, 125.82, 125.97, 127.13, 127.74, 128.96, 129.24, 133.33, 149.16 (C=N), 155.36 (S–C=N), 157.36, 172.17 (2C=O); MS (EI, 70 eV): m/z (%) = 354.04 (M+) (27.26%), 178.20 (100%); Anal. Calcd. for C16H14N6O2S (354 .09): C, 54.23; H, 3.98; N, 23.71; Found: C, 54.31; H, 4.11, N, 23.11.

4.4. Synthesis of 3-Aryl-2-(5-(2-(1,5-dimethyl-3-oxo-2-phenyl-2,3-dihydro-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)hydr-zono)-4-oxo-4,5-dihydrothiazol-2-yl)acrylonitrile Derivatives (15a and 15b)

A solution of 2-(5-(2-hydrazono)-4-oxo-4,5-dihydrothiazol-2-yl)acetonitrile derivative (14) (0.01 mol) in absolute ethanol (20 mL) having few drops of piperidine with different aromatic aldehydes (0.01 mol) was added to the reaction mixture, and then the solution was heated under reflux for 6–8 h. The solid products formed were collected by filtration and recrystallized from ethanol.

4.4.1. 2-(5-(2-(1,5-Dimethyl-3-oxo-2-phenyl-2,3-dihydro-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)hydrazono)-4-oxo-4,5-dihydrothiazol-2-yl)-3-phenylacrylonitrile (15a)

Brown powder (EtOH); Yield: 73%; M.p.: 195–197; IR (KBr, ν/cm–1): 3200 (NH), 3031 (CH-arom.), 2942 (CH-aliph.), 2205 (CN), 1708 (C=O), 1599 (C=N); 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ/ppm 2.49 (s, 3H, CH3), 3.01 (s, 3H, -NCH3), 7.35 (s, 1H, methine-H), 7.42 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 3H, Ar-H), 7.51 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 7.61 (t, 3H, Ar-H), 7.66 (d, 2H, Ar-H), 8.37 (s, 1H, NH exchangeable by D2O); 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ/ppm 10.91 (CH3), 34.11 (N–CH3), 105.89, 113.59, 123.15, 125.09, 125.47, 125.95, 127.13, 127.33, 128.07, 128.70, 129.14, 129.41, 130.84, 131.99, 132.57, 133.58, 134.52, 143.37 (C=N), 148.91 (S–C=N), 157.84, 174.93 (2C=O); Anal. Calcd. for C23H18N6O2S (442.50): C, 62.43; H, 4.10; N, 18.99; Found: C, 62.55; H, 4.42, N, 18.32.

4.4.2. 3-(4-Chlorophenyl)-2-(5-(2-(1,5-dimethyl-3-oxo-2-phenyl-2,3-dihydro-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)hydrazono)-4-oxo-4,5-dihydrothiazol-2-yl)acrylonitrile (15b)

Brown powder (EtOH); Yield 73%; M.p.; 225–227 °C; IR (KBr, ν/cm–1): 3181 (NH), 3061 (CH-arom.), 2938 (CH-aliph.), 2196 (CN), 1703 (C=O), 1590 (C=N);1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ/ppm 2.56 (s, 3H, CH3), 3.26 (s, 3H, N-CH3), 7.41 (t, J = 8.4 Hz, 3H, Ar-H), 7.47 (s, 1H, methine-H), 7.55 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 7.59 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 7.65 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 8.31 (s, 1H, NH exchangeable by D2O); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ/ppm 11.16 (CH3), 34.99 (N-CH3), 105.79, 114.68, 117.40, 122.76, 123.81, 125.81, 126.02, 127.96, 128.14, 129.10, 129.44, 130.74, 131.47, 132.94, 133.76, 134.81, 148.28, 154.13 (2C=N), 158.66 (S–C=N), 167.14, 178.39 (2C=O); Anal. Calcd. for C23H17ClN6O2S (476.94): C, 57.92; H, 3.59; N,17.62; Found: C, 58.22; H, 4.14, N, 17.32.

4.5. Synthesis of 2,3-Dihydro-7H-thiazolo[3,2-a]pyridine-6,8-dicarbonitrile Derivatives (16a and 16b)

4.5.1. Method (1)

To a solution of 15a and 15b (0.01 mol) in absolute ethanol (20 mL) having few drops of piperidine, malononitrile (0.01 mol) was added. The solution was refluxed for 2–4 h, and solid products formed were collected by filtration and were recrystallized from ethanol.

4.5.2. Method (2)

To a solution of 2-(5-(2-hydrazono)-4-oxo-4,5-dihydrothiazol-2-yl)acetonitrile derivative (14) (0.01 mol) in absolute ethanol (20 mL) having few drops of piperidine, arylidine malononitrile derivatives (0.01 mol) was added. The solution was heated under reflux conditions for 4–8 h, and solid products formed were collected by filtration and recrystallized from ethanol.

4.5.3. 5-Amino-2-(2-(1,5-dimethyl-3-oxo-2-phenyl-2,3-dihydro-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)hydrazono)-3-oxo-7-phenyl-2,3-dihydro-7H-thiazolo[3,2-a]pyridine-6,8-dicarbonitrile (16a)

Brown powder (EtOH); Yield: 73%; M.p.: 195–197 °C; IR (KBr, ν/cm–1): 3442, 3318, 3117 (NH2, NH), 3011 (CH-arom.), 2914 (CH-aliph.), 2201 (CN), 1700 (C=O), 1589 (C=N); 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ/ppm 2.55 (s, 3H, CH3), 3.31 (s, 3H, N-CH3), 4.02 (s, 1H, Pyridine-H), 5.24 (s, 1H, NH exchangeable by D2O), 7.35 (s, 2H, NH2 exchangeable by D2O), 7.40 (d, 2H, Ar-H), 7.45 (d, 2H, Ar-H), 7.52 (t, 3H, Ar-H), 7.72 (t, 3H, Ar-H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ/ppm 10.61 (CH3), 34.37 (N-CH3), 38.63 (pyridine-C), 59.67, 74.91 (2C-CN), 106.20, 111.91, 122.38, 125.94, 126.21, 127.9, 127.87, 128. 58, 129.23, 129.27, 131.13, 131.44, 132.65, 134.11, 134.18, 144.63 (C=N), 150,11 (C–NH2), 154.24, 156,51 (2C=O); Anal. Calcd. for C26H20N8O2S (508.56): C, 61.41; H, 3.96; N, 22.03; Found: C, 61.11; H, 4.21; N, 22.35.

4.5.4. 5-Amino-7-(4-chlorophenyl)-2-(2-(1,5-dimethyl-3-oxo-2-phenyl-2,3-dihydro-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)hydrazono)-3-oxo-2,3-dihydro-7H-thiazolo[3,2-a]pyridine-6,8-dicarbonitrile (16b)

Brown powder (EtOH); Yield 78%; M.p.:205–207 °C; IR (KBr, ν/cm–1): 3577, 3318, 3173 (NH2, NH), 3017 (CH-arom.), 2927 (CH-aliph.), 2203 (CN), 1702 (C=O), 1591 (C=N); 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ/ppm 2.59 (s, 3H, CH3), 3.25 (s, 3H, N–CH3), 4.12 (s, 1H, pyridine-H), 5.24 (s, 1H, NH exchangeable by D2O), 7.29 (s, 2H, NH2 exchangeable by D2O), 7.43 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 7.38 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H, Ar–H), 7.44 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 7.51 (t, 1H, Ar-H), 7.58 (t, 2H, Ar-H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ/ppm 10.70 (CH3), 34.48 (N–CH3), 38.67 (pyridine-C), 69.53, 76.81 (2C-CN), 106.15, 122.76, 123.61, 125.97, 126.07, 126.94, 127.77, 127.90, 128.99, 129.28, 129.40, 130.37, 131.09, 131.43, 132.89, 134.24, 134.55, 143.62 (C=N), 149.91 (C–NH2), 161.12, 166.24 (2C=O); Anal. Calcd. for C26H19ClN8O2S (543.00): C,57.51; H, 3.53; N, 6.53; Found: C, 57.82; H, 3.82, N, 6.21.

4.6. Biological Activity

4.6.1. Antimicrobial Sensitivity Assay by an Agar Well-Diffusion Method

All the synthesized compounds were individually tested against a panel of clinical Gram-positive [S. aureus (MDR00231), S. epidermidis (MDR00223), and B. subtilis (MDR00423)], Gram-negative [E. coli (MDR00501), A. baumannii (MDR00521), and K. pneumoniae (MDR00244)] bacterial pathogens and two C. albicans (MDR00100) and (MDR00200) fungal isolates from different UTIs clinical samples obtained from the Central Laboratories, El-Demerdash Hospital, Ain-Shams University, Cairo, Egypt. The antimicrobial tests were carried out by the agar well-diffusion method45,57 using a suspension containing 1 × 108 CFU/mL of each tested bacteria and 1 × 106 CFU/mL of yeast on tryptic soya agar (TSA) and Sabouraud dextrose agar (SDA) plates, respectively. Wells of 10 mm were made and loaded with 50 μL of each tested compound and the reference drugs (100 mg/mL) dissolved in DMSO. The plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h for bacteria and at 28 °C for 48–72 h for yeast. Ciprofloxacin and Ketoconazole were employed as standard references for antibacterial and antifungal activities, respectively. The antimicrobial activity was evaluated by measuring the zones of inhibition (IZs), expressed in mm, against the pathogens and compared with the standards. The test was carried out in triplicate, and the average zone of inhibition (AZOI) was determined.

4.6.2. Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) and Minimum Bactericidal/Fungicidal Concentration (MBC/MFC) Determination

The MIC of the target compounds (having inhibition zones > 9 mm) was then determined using the broth microdilution method.58 Two-fold serial dilutions of the tested compounds were prepared to give a concentration range 0.125–128 μg/mL. Sterile test tubes containing the target compounds were placed in sterile TSB medium for bacteria and sterile SDB for the fungi. The TSB and SDB tubes with and without the compounds were used as controls. The MIC was detected as the lowest concentration of the compound showing no visible growth of the tested organisms. The experiment was performed in triplicate, and the data was analyzed using the SPSS 20.0 software. To determine the MBC and MFC for each test tube in the MIC determination, a loopful of 5 μL was collected from those tubes that showed no growth and inoculated on sterile TSA and SDA plates by streaking. The plates were then incubated with bacteria and fungi at 37 °C for 24 h and at 28 °C for 48 h, respectively. The lowest concentration at which no visible growth was observed was noted as the MBC or MFC.59 In addition, MBC/MIC and MFC/MIC ratios were determined, and if the tested agent yields an MBC or MFC/MIC ratio ≤ 4, then it is considered to be -cidal, but if it yields a ratio > 4, then it will be -static.60

4.6.3. Staphylococcus Biofilm Mass Reduction Determination

The microtiter dish biofilm formation assay47,61 was employed to assess the ability of the compounds to disrupt the biofilm formed by the Staphylococcal isolates (S. aureus and S. epidermidis). Each tested bacterial isolate was transferred to TSB and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h60 followed by further dilution using the TSB with 1% glucose to reach a concentration of 1:200. For each bacterial isolate, the suspension was transferred onto the wells of a 96-well microtiter plate and incubated to allow biofilm formation. The planktonic bacterial cells were removed by washing the wells three times using PBS. The synthesized compounds and Ciprofloxacin were added to the wells and serially diluted. After incubation at 37 °C for 24 h, the plate was washed three times using water, stained by 0.1% crystal violet, and then left for 20 min before addition of 95% ethanol for decolorization. Using a microtiter plate reader, the optical density of each well at 595 nm was measured. The % of biofilm mass reduction was calculated for each treatment compared with the control (wells with no treatment).

4.6.4. Single-Step Resistance Selection

The frequency of single-step resistance of the most active pyrazole compounds 4a, 5a, 7b, 10, and 13 and antibiotics (Ciprofloxacin and Ketoconazole) for the tested bacterial and fungal isolates was determined as reported.47,62 In brief, cultures of 1 × 109 CFU/mL were spread onto TSA and SDA plates containing each compound and each antibiotic at 4 × MIC concentration. The plates were incubated at 37 °C (for bacteria) and at 28 °C (for fungi) for 48 h. the frequency of resistance was calculated by counting the number of resistant colonies per inoculum.

4.6.5. Combination Therapy Analysis of Active Pyrazole Derivatives with Antibiotics

The combination between active pyrazolo-thiazole derivatives 4a, 5a, 7b, 10, and 13 and antibiotics (Ciprofloxacin and Ketoconazole) was assessed via a standard checkerboard assay63 and represented as the fractional inhibitory concentration index (ΣFICI) i.e., the sum of the FIC for each compound. Bacterial suspensions were prepared in PBS equivalent to the 0.5McFarland standard. The bacteria were then diluted in TSB to achieve a starting bacterial density of 1 × 105 CFU/mL. The MIC of each test compound in combination with each antibiotic studied was determined as the lowest concentration of each combination in which no visible growth was observed. The fractional inhibitory concentration index (ΣFICI) was calculated for each combination using the following equation:

FICI ≤ 0.5 (synergism); 0.5 < FICI <1 (partial synergism); 1 ≤ FICI <2 (indifference); and FICI ≥2 (antagonism).

4.6.6. Hemolytic Assay