Abstract

Angelica furcijuga (A. furcijuga), as a material for traditional Chinese medicine, has been widely used in Asian countries, such as China, Korea, and Japan, for several centuries owing to its therapeutic effects. In this study, A. furcijuga leaves were used as starting materials to extract functional substances using supercritical carbon dioxide (SC-CO2) at pressure and temperature ranges of 20–40 MPa and 40–80 °C, respectively. The extraction process was performed in a semibatch-type system with extraction times of 15–120 min. The high-performance liquid chromatography analysis indicated that kaempferol, ferulic acid, ligustilide, and butylidenephthalide as selected functional substances were successfully extracted under these operating conditions. An operating pressure of 30 MPa with an extraction time of 60 min seems to be an appropriate pressure to extract functional components from A. furcijuga leaves. The Hansen solubility parameter values and statistical analysis showed that SC-CO2 with 10% ethanol addition is a feasible tool to isolate these selected functional substances from the A. furcijuga matrix.

Introduction

Angelica acutiloba (A. acutiloba) is a perennial plant belonging to the Umbelliferae family and is known for its medicinal properties. Its efficacy varies, and it is used as an analgesic for the treatment of dysmenorrhea, menstrual pain, and rheumatism;1−3 however, in recent years, pharmacological research has been actively conducted. In addition, there are several subspecies of A. acutiloba cultivated in Japan, each of which has a pharmacological action.4−6 Hyugatouki (A. furcijuga) is a family of A. acutiloba that has been cultivated in some areas of southern Kyushu. “Hyuga” refers to the Miyazaki prefecture in Japan. In the Japanese Pharmacopeia, the roots of A. furcijuga are registered and certified as crude drugs. The roots have a pain-reducing effect on human cancer cells, an apoptotic effect, and a preventive effect on Alzheimer’s disease and are suggested to alleviate these diseases.7−10 Conversely, parts other than the roots, such as the leaves of A. furcijuga, are not currently registered in the Pharmacopeia and are easy to utilize. Processed products, such as healthy tea, are highly evaluated for their effects. There are still few reports on the functional components present at the site of A. furcijuga. Figure 1 shows the A. furcijuga cultivated by a food company in Fukuoka Prefecture (Maruboshi Vinegar Co., Ltd., Fukuoka, Japan).

Figure 1.

(a) A. furcijuga strain and (b) cultivated farmland.

In this study, carbon dioxide under supercritical conditions was used to extract functional substances from A. furcijuga leaves. The most commonly employed techniques to extract functional substances from plant biomass are Soxhlet extraction, maceration, and soaking.11,12 However, these techniques have several disadvantages, such as large amounts of organic solvents, low selectivity or low-quality extracts, and long processing times.13,14 Degradation of sensitive functional substances may also occur. The utilization of organic solvents, such as hexane, methanol, acetone, and chloroform, during the extraction process may shift the chemical nature of the functional substance, causing them to be poisonous for human consumption.13 Hence, the development of a technique for the extraction of functional substances from plant biomass can result in high-quality products.

Carbon dioxide (CO2; Tc = 31.1 °C; Pc = 7.4 MPa) is suitable for extracting natural compounds because it has a low critical temperature, which is particularly suitable for thermally unstable components. As the favored selection of solvent, CO2 is nontoxic, nonflammable, colorless, odorless, safe, and recyclable. Under supercritical conditions, CO2 may act as a gas or liquid. It has a liquid-like density, gas-like diffusivity, and gas–liquid-like viscosity. Because of these features, supercritical carbon dioxide (SC-CO2) has become a favorable solvent for extracting functional substances from plant biomass matrices, including A. furcijuga leaves.13,15 Moreover, CO2 is gaseous under ambient conditions; thus, once the extraction process is completed, CO2 is easily removed completely from the extracts via depressurization of the extraction apparatus system. However, the polarity of CO2 is low.13,15 This causes ineffective extraction when SC-CO2 is used to extract more polar functional substances from natural sources. To solve this restriction, a cosolvent (modifier or entrainer) was employed and added in small amounts to enhance the CO2 solubilizing capacity. The addition of a cosolvent may also improve the extraction of polar functional substances.16,17 In this study, ethanol was selected as a cosolvent. This organic solvent is commonly applied as a cosolvent owing to its low toxicity and may enhance the extraction capacity of polar functional substances, such as phenolic compounds.18

Results and Discussion

Figure 2 shows the results of the extraction analysis of (a) kaempferol, (b) ferulic acid, (c) ligustilide, and (d–e) butylidenephthalide as a function of extraction time. For butylidenephthalide, there are two types of geometric isomers, that is, cis-type (Z) and trans-type (E), owing to carbon double bonds. These functional components were not obtained in the extract when the ethanol solvent was not added as a cosolvent into the SC-CO2 system during extraction of A. furcijuga leaves, mostly because of their high polarity. As aforementioned, CO2 is a nonpolar fluid, and it is the main drawback when it is employed for the isolation of these functional components. Hence, their data were not shown, and only the results of extract analysis when the extraction processes were conducted using SC-CO2 with ethanol addition as a cosolvent under various extraction conditions were presented. As shown in Figure 2, the extraction yields of kaempferol, ferulic acid, ligustilide, Z-butylidenephthalide, and E-butylidenephthalide increased as the extraction time increased from 15 to 120 min under each operating condition. In supercritical fluid extraction technology, extraction time is one of the most important parameters because the analysis of the extraction process is conducted based on the whole extraction curve (yield vs extraction time), which provides information for the time needed to realize the advantageous and economical extraction process.19,20 The target substance recovery at the highest rate with the shortest time can be observed, and thus the recovery yield efficiency information of target substances was obtained. Figure 2 shows that the amounts of kaempferol, ferulic acid, ligustilide, Z-butylidenephthalide, and E-butylidenephthalide increased significantly until 60 min. After that, it increased slightly until 120 min of extraction. At the beginning of the extraction stage, the SC-CO2–ethanol solvent easily contacted the target functional components on the easily accessible location or surface of the Hyugatouki matrix. They were then dissolved rapidly and flowed out together with the SC-CO2–ethanol solvent, resulting in a high extraction rate. Afterward, the extraction rate was constant or slightly increased because of the exhaustion of kaempferol, ferulic acid, ligustilide, Z-butylidenephthalide, and E-butylidenephthalide in the Hyugatouki matrices.17 Hence, it could be inferred that 60 min of extraction is sufficient to extract functional components from A. furcijuga leaves. Moreover, a shorter extraction time may also reduce the CO2 and cosolvent consumption and avoid thermal degradation of the extract, which can decrease the recovery yield efficiency.

Figure 2.

Extraction yields of functional components as a function of extraction time: (a) kaempferol, (b) ferulic acid, (c) ligustilide, and (d–e) butylidenephthalide.

The operating pressure is an important variable in supercritical fluids that may enhance the solvent power and have a high effect on product selectivity.21−23 At a constant operating temperature, the density of the fluid under supercritical conditions increases with increasing operating pressure. Because the solvent power is related to the fluid density, the increase in density may enhance the fluid solvent power, resulting in an increased extraction yield. Figure 3 shows the extraction yields of kaempferol, ferulic acid, ligustilide, Z-butylidenephthalide, and E-butylidenephthalide from A. furcijuga matrices under various extraction conditions. The extraction yield of each functional component increased with increasing operating pressure at the same operating temperature. This may be because of the increase in the density of CO2 under supercritical conditions, which implies that the solvent power of SC-CO2 increases when the operating pressure is increased at a constant operating temperature, resulting in an increasing amount of extracted functional components from A. furcijuga leaves.21−23 Saito et al. conducted an experiment for phenolic compound extraction using the SC-CO2 extraction system with green propolis and Brazilian red as raw material sources.21 They reported that although the extracted yield fraction depended especially on the extraction temperature and was slightly influenced by the extraction pressure, the increasing operating pressures at the constant operating temperature resulted in the increasing extracted yield fraction, including the total flavonoid content. Idham et al. also reported that the increasing operating pressure may increase the total anthocyanin content value when they carried out experiments for the natural red pigment extraction from the Hibiscus sabdariffa matrix using the SC-CO2 extraction system.22 They explained that the increasing operating pressure could give a beneficial effect due to the increasing CO2 density and diffusivity. At high operating pressures, the fluctuation of CO2 density may occur and intensify the interaction between the CO2 fluid as an extraction solvent and the H. sabdariffa matrix. Next, the functional substances in the H. sabdariffa matrix including anthocyanins were quickly released into the CO2 extraction solvent, resulting in the increasing anthocyanin content in the extract.

Figure 3.

Total extraction yields of functional components at various extraction conditions: (a) kaempferol, (b) ferulic acid, (c) ligustilide, and (d–e) butylidenephthalide.

As depicted in Figure 3, the functional component extraction yields increased at extraction pressures of 20–30 MPa. On the contrary, these extraction yields do not appear to increase, except ferulic acid and E-butylidenephthalide, even though they seem to decrease when the operating pressure is increased to 40 MPa. This indicates that at a given operating temperature, the SC-CO2 density increases with increasing operating pressure, and the solute vapor pressure decreases. Because the operating conditions may have overcome the SC-CO2 density effect, the extraction rate of the functional component was still high, resulting in a high extraction yield. However, at a higher operating pressure (40 MPa), the solute vapor pressure might decrease drastically and dominate the SC-CO2 density effects, resulting in a decrease in the extraction yield. In addition, the high operating pressure may also bring the A. furcijuga leaves to be compacted, resulting in channeling that can decrease the mass transfer and interaction between the SC-CO2 solvent and A. furcijuga matrices.24−26 Osorio-Tobon et al. reported that the increasing operating pressure at a constant operating temperature in the SC-CO2 extraction system gave a negative effect on the curcuminoid extraction yield due to the high operating pressure that may induce the raw material sources, resulting in decreasing their active surfaces and functional substances leaching from the raw material sources into the CO2 extraction solvent.24 Moreover, as the operating pressure increased, the raw material matrix bed might be compacted, and the channels might be formed. This can prevent the proper contact between the target functional substances and the extraction solvent, resulting in decreasing extraction efficiency. Dali et al. also found similar phenomena when they performed SC-CO2 extraction experiments to extract oil from olive mill wastewater.26 They reported that the increasing operating pressure may lead to a greater solid matrix compaction and may reduce the solid matrix void fraction, which can cause decreasing extraction efficiency. Next, based on these results, it appears that 30 MPa is an appropriate operating pressure for extracting functional components from A. furcijuga leaves.

Figure 3 also shows that the increased operating temperature of the SC-CO2 extraction system is followed by a change in the functional component yields because the density and the solvent power of CO2 under supercritical conditions were also affected by the changing operating temperature at a constant operating pressure. Increasing the operating temperature may improve solubility, and if the operating temperature is above the functional component melting point to be extracted, better dissolution might occur. This implies that increasing the operating temperature may improve the mass transfer and consequently increase the overall extraction yields of the functional components. Nevertheless, because the density of CO2 under supercritical conditions decreases with the increasing operating temperature at a constant operating pressure leading to the solvent power reduction, the temperature effect seems more complicated. As a result, as depicted in Figure 3, in several cases, the increasing operating temperature favors the improvement of the dissolution process, which may increase the overall extraction yields of functional components from A. furcijuga leaves. This phenomenon could be observed in the overall extraction yields of kaempferol and ferulic acid when the extraction process was performed at an operating pressure of 30 MPa and operating temperatures of 40–80 °C. Conversely, the overall extraction yields of ligustilide and Z-butylidenephthalide decreased under the same operating conditions. In this case, increasing the operating temperature at a given operating pressure reduces the SC-CO2 solvent power, resulting in decreased ligustilide and Z-butylidenephthalide recoveries from A. furcijuga leaves. Furthermore, increasing the operating temperature at a given operating pressure decreased the SC-CO2 density, leading to negative effects on the overall extraction yield. Conversely, it also improved the solute vapor pressure, which may enhance solute extraction.23,27,28 Tan et al. reported that the effect of operating temperature on the extraction yield in the SC-CO2 extraction system is quite complex when they conducted experiments for SC-CO2 extraction to extract the functional substances from the mixture of pomegranate peel-seed.27 However, they explained that, at a given operating pressure, the global yield of the functional substance decreased at the high operating temperature owing to the decreasing CO2 density, resulting in the CO2 solvent power to decrease, causing the efficiency of SC-CO2 extraction to decrease. Arias et al. performed pinocembrin extraction using the SC-CO2 extraction system with the residue of Lippia origanoides distillation as a raw material source.28 They also reported that, at a constant operating pressure, the desorption process increases rather than the solubility process when the SC-CO2 extraction process was carried out at the high operating temperature, resulting in the decreasing extraction yield. This negative impact was due to the decreasing CO2 solvent power and density at the high operating temperature.

As selected functional components, kaempferol, ferulic acid, ligustilide, and butylidenephthalide were successfully extracted from A. furcijuga leaves at various extraction conditions, and the analysis results were presented. Next, the solubility parameters of these substances and the pure solvent were determined, and the compatibility between the pure solvent and the functional components during extraction was investigated based on the experimental results. Table 1 lists the calculated dissolution parameters for the selected functional components and pure solvents. The Hansen solubility parameter (HSP) values of kaempferol, ferulic acid, ligustilide, and butylidenephthalide were similar to those of pure solvents, such as ethanol, methanol, and acetone. This indicated that the solubility of these functional components in ethanol, methanol, or acetone solvent was high. Conversely, according to the HSP values of kaempferol, ferulic acid, ligustilide, butylidenephthalide, and CO2, these selected functional components did not seem to dissolve in CO2 even under supercritical conditions. They were not extracted from Hyugatouki leaves when CO2 was employed as an extraction solvent without cosolvent addition during the extraction process. In contrast, they could be extracted from Hyugatouki leaves when the ethanol solvent (10%) was added as a cosolvent. This revealed that the addition of a cosolvent (ethanol) may enhance the solubilizing capacity of CO2 under supercritical conditions.16−18 This can be explained as follows. Although the dispersion (δd) value of ethanol does not differ significantly from the δd value of CO2 at supercritical conditions, the polar (δp) and the hydrogen bonding (δh) values of ethanol are considerably higher than the δp and δh values of CO2 at supercritical conditions. As a result, the selected functional components, that is, kaempferol, ferulic acid, ligustilide, and butylidenephthalide, which have high polarity values, can be extracted from A. furcijuga leaves because the solubilizing capacity of SC-CO2 increases.

Table 1. Hansen Solubility Parameters for Selected Functional Components and Pure Solventsa.

| solubility parameter |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| substance | δD (MPa1/2) | δP (MPa1/2) | δH (MPa1/2) | conditions |

| kaempferol | 20.3 | 9.3 | 17.2 | ordinary |

| ligustilide | 17.7 | 9.4 | 6.6 | ordinary |

| ferulic acid | 19.3 | 8.4 | 15.8 | ordinary |

| butylidenephthalide | 18.7 | 5.9 | 3.8 | ordinary |

| ethanol | 15.8 | 8.8 | 19.4 | ordinary |

| methanol | 14.7 | 12.3 | 22.3 | ordinary |

| acetone | 15.5 | 10.4 | 7 | ordinary |

| CO2 | 15.7 | 6.3 | 5.7 | ordinary |

| 10.8 | 4.5 | 4.9 | 20 MPa, 40 °C | |

| 12.0 | 4.7 | 5.1 | 20 MPa, 60 °C | |

| 12.7 | 4.8 | 5.2 | 20 MPa, 80 °C | |

| 9.0 | 4.2 | 4.6 | 30 MPa, 40 °C | |

| 10.7 | 4.5 | 4.9 | 30 MPa, 60 °C | |

| 11.6 | 4.6 | 5.1 | 30 MPa, 80 °C | |

| 7.0 | 3.8 | 4.1 | 40 MPa, 40 °C | |

| 9.3 | 4.2 | 4.6 | 40 MPa, 60 °C | |

| 10.6 | 4.4 | 4.9 | 40 MPa, 80 °C | |

| CO2 + ethanol | 11.1 | 4.8 | 5.9 | 20 MPa, 40 °C |

| 12.2 | 4.9 | 6.0 | 20 MPa, 60 °C | |

| 12.9 | 5.0 | 6.1 | 20 MPa, 80 °C | |

| 9.4 | 4.4 | 5.5 | 30 MPa, 40 °C | |

| 10.9 | 4.7 | 5.8 | 30 MPa, 60 °C | |

| 11.9 | 4.8 | 5.9 | 30 MPa, 80 °C | |

| 7.5 | 4.0 | 5.0 | 40 MPa, 40 °C | |

| 9.7 | 4.5 | 5.5 | 40 MPa, 60 °C | |

| 10.8 | 4.7 | 5.7 | 40 MPa, 80 °C | |

δD, dispersion force; δP, dipole force; δH, hydrogen-bonding force.

In this study, the statistical analysis of variance of the experimental results was performed to determine the F-test and P-value, which were used to observe the effects of operating conditions on the yield of extracted functional components from A. furcijuga leaves. Table 2 summarizes the significance of each coefficient from the F-test and the P-value calculations. A high F-test and a low P-value (P-value, <0.05) indicated a significant effect on the extracted functional component yields from A. furcijuga leaves for all extraction parameters. As shown in Table 2, the extraction yield of ferulic acid was significantly affected by the extraction temperature. The yield of E-butylidenephthalide was significantly influenced by the extraction pressure and extraction temperature; the extraction pressure and temperature did not have a significant influence on the extraction yields of kaempferol, ligustilide, and Z-butylidenephthalide. Except for the ligustilide substance, the statistical analysis seems to agree with the solubility parameters of these functional substances, which relates to the solubility of chemical compounds in the SC-CO2 extraction system. This phenomenon was probably caused by ligustilide substance degradation during the extraction process because this substance is volatile and an unstable liquid. It can shift into other phthalides via various reactions, that is, isomerization, oxidation, and dimerization.29 Judging from the results, the extraction using SC-CO2 with 10% ethanol addition is a feasible method to extract flavonoids and polyphenols from various plant matrices, especially from A. furcijuga leaves.

Table 2. Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) for Experimental Parameters.

| extraction

parameter |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| functional substance | statistical parameter | pressure | temperature |

| kaempferol | F-test | 2.6591 | 0.9535 |

| P-value | 0.1842 | 0.4585 | |

| ferulic acid | F-test | 2.8837 | 5.4213 |

| P-value | 0.1677 | 0.0476 | |

| ligustilide | F-test | 0.8358 | 0.3844 |

| P-value | 0.4974 | 0.7036 | |

| Z-butylidenephthalide | F-test | 1.3591 | 0.7661 |

| P-value | 0.3545 | 0.5228 | |

| E-butylidenephthalide | F-test | 12.354 | 63.920 |

| P-value | 0.0194 | 0.0009 | |

Conclusions

This work demonstrated that SC-CO2 with 10% ethanol as a cosolvent can be employed to extract phytochemical substances from A. furcijuga leaves. The maximum yields of kaempferol, ferulic acid, ligustilide, Z-butylidenephthalide, and E-butylidenephthalide were 0.48 (40 MPa, 40 °C), 0.03 (40 MPa, 80 °C), 6.68 (40 MPa, 40 °C), 3.84 (30 MPa, 40 °C), and 0.64 (40 MPa, 60 °C) mg/g of dried A. furcijuga leaves, respectively. However, 60 min of extraction seems to be sufficient to extract the functional components from A. furcijuga leaves. The experimental results also indicated that 30 MPa is an appropriate operating pressure to extract functional components from A. furcijuga leaves. The increasing operating temperature at a given operating pressure negatively affected the overall extraction yield. According to HSP values and statistical analysis, SC-CO2 containing 10% ethanol as an extracting solvent is a feasible tool to isolate flavonoids and polyphenols from various plant matrices including the A. furcijuga matrix.

Materials and Methods

Materials

In this study, A. furcijuga leaves were used as raw materials. The leaf sample of A. furcijuga was harvested in November 2020 and freeze-dried immediately after harvesting as a pretreatment (refer to Figure 4). As raw materials, these leaves were ground using a laboratory mill to a particle size of <2 mm and passed through 16-mesh sieves; it was then stored in a refrigerator at <6 °C. Kaempferol (K0117, LKT Labs, Inc.), ferulic acid (F1669, LKT Labs, Inc.), ligustilide (L397900, Toronto Research Chemicals Inc.), Z-butylidenephthalide (W333301, Sigma-Aldrich Japan G.K.), and E-butylidenephthalide (W333301, Sigma-Aldrich Japan G.K.) were used as chemical reference standards for chromatographic analysis. Acetonitrile (99.8%, 015-08633) and ethanol (99.5%, 05400-461) were purchased from Fujifilm Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Ltd., Osaka, Japan. Water was distilled using a distillation apparatus (Auto Still WS 200, Yamato Scientific Co., Ltd., Japan), and CO2 was obtained from Tomoe Shokai Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan.

Figure 4.

Dried A. furcijuga leaves.

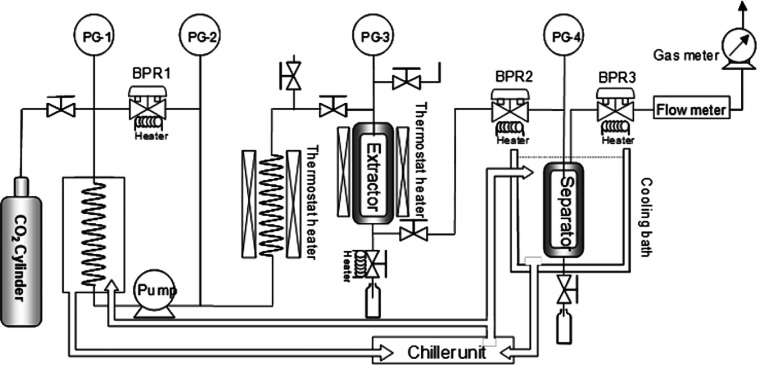

Experimental Apparatus

Figure 5 shows a schematic illustration of the SC-CO2 extractor with the cosolvent addition option. The maximum operating conditions of the device were 200 °C and 45 MPa. The pressure in the extractor was controlled using a back-pressure regulator (HBP-450; Akico Co., Ltd.). The extraction temperature was controlled in an oven. Approximately 1 g of the sample was placed in a 10 mL extraction cell (Thar Technologies, Inc., Pittsburgh, PA, USA). The conditions of the SC-CO2 extraction experiment were performed at pressures of 20–40 MPa and temperatures of 40–80 °C. Extracts were collected in screw bottles at six times of 15, 30, 45, 60, 90, and 120 min.

Figure 5.

Schematic illustration of the SC-CO2 extraction apparatus.

In this study, no CO2 flow rate variation was pumped into the extraction apparatus system during the experiments. The CO2 flow rate was 3 mL/min, and the percentage ratio of ethanol as a cosolvent was 10% of the CO2 flow rate. Next, the screw bottles containing the collected products were wrapped with aluminum foil and stored in a refrigerator at <6 °C until analysis.

Analytical Methods

A. furcijuga contains various functional components, including flavonoids and phenolic compounds. However, in this study, kaempferol, ferulic acid, ligustilide, and butylidenephthalide (refer to Figure 6) were selected as the targets of functional compounds from A. furcijuga matrices and determined quantitatively by HPLC. These compounds are widely recognized to have therapeutic potential as anti-inflammatory, anticancer, and antioxidant, have neuroprotective effects, and display antiaging effects.7−10

Figure 6.

Some selected functional components of A. furcijuga: (a) kaempferol, (b) ferulic acid, (c) ligustilide, and (d) butylidenephthalide.

The extracts were analyzed using an HPLC LC-10 AD gradient system (Shimadzu, Japan) equipped with a photodiode array detector (SDP-M10A). An Inertsil ODS-3 column (5 μm, 4.6 mm × 250 mm, GL Science, Japan) was used for separation at 35 °C. The mobile phase consisted of solvent A, 0.1% acetic acid in water, and solvent B, acetonitrile/water (75/25, v/v). The gradient elution was 0 min A-B (88:12); 18 min A-B (78:22); 28 min A-B (72:28); 35 min A-B (62:38), 48 min A-B (52:48), 58 min A-B (0:100), and 70 min A-B (88:12). The flow rate was 1.0 mL/min. To determine the content of kaempferol, ferulic acid, ligustilide, and butylidenephthalide in the extracts, the wavelengths were set at 367, 322, 326, and 310 nm, respectively.30−32 First, pure kaempferol, ferulic acid, ligustilide, and butylidenephthalide (Z- and E-type) standard functional components were introduced into the HPLC system to create a calibration curve from 50 to 200 ppm. Thereafter, the amounts in the extract were quantified using their respective calibration curves. The yields of pure kaempferol, ferulic acid, ligustilide, and butylidenephthalide were specified as the weight of the product recovered to the initial weight of dried A. furcijuga leaves loaded into the extraction apparatus system.

Hansen Solubility Parameter Calculation

The solubility theoretical knowledge of kaempferol, ferulic acid, ligustilide, and butylidenephthalide as selected functional components from A. furcijuga leaves was determined using HSP. The HSP values were predicted by HSiP 4.1.04 software, and according to this prediction, the close value of HSP between the selected functional components and the solvent might indicate high solubility. The HSP for CO2 under various conditions was calculated according to NIST data (https://webbook.nist.gov/chemistry/fluid/) and Williams et al.33

| 1 |

| 2 |

| 3 |

Here, δdref, δpref, and δhref are the HSP references (MPa1/2). Vref (39.13 cm3/mol) is the molar volume at the reference pressure (Pref, 0.1 MPa) and reference temperature (Tref, 25 °C). The dispersion interaction parameter (δd) was determined from the vaporization energy and molar volume as a function of temperature, the polar interaction parameter (δp) was based on the solvent molecule dipole moment, and the hydrogen bonding interaction parameter (δh) was determined by mitigating the dispersion and polar energies of vaporization from the total energy of vaporization. Equations 4 and 5 were used to calculate the HSP considering the temperature dependence of the liquid and the mixture of two or more solvents, respectively:34

|

4 |

| 5 |

where T is the given temperature, Tc is the critical temperature of substance i, and xi is the composition of each of the substances (CO2 and ethanol, in percentage).

Statistical Analysis

Data were presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of duplicate/triplicate determinations. Statistical calculations were performed using Microsoft Excel for Office 365. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to determine statistical differences. Differences were considered significant when the P-value was <0.05.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Kyusyu Bureau of Economy, Trade, and Industry.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- SC–CO2

supercritical carbon dioxide

- Tc

Critical temperature

- Pc

critical pressure

- CO2

carbon dioxide

- HPLC

high-performance liquid chromatography.

Author Contributions

All authors have approved the final version of the manuscript.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Tang W.; Eisenbrand G.F.. Chinese Drugs of Plant Origin Chemistry, Pharmacology, and Use in Traditional and Modem Medicine; Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg: 1992; pp. 118. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L.; Du J. R.; Wang J.; Yu D. K.; Chen Y. S.; He Y.; Wang C. Y. Z-ligustilide Extracted from Radix Angelica Sinensis Decreased Platelet Aggregation Induced by ADP Ex Vivo and Arterio-venous Shunt Thrombosis In Vivo in Rats. Yakugaku Zasshi 2009, 129, 855–859. 10.1248/yakushi.129.855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waksmundzka-Hajnos M.; Sherma J.. High Performance Liquid Chromatography in Phytochemical Analysis; CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group: Boca Raton, 2011; pp. 254. [Google Scholar]

- Kumazawa Y.; Mizunoe K.; Otsuka Y. Immunostimulating polysaccharide separated from hot water extract of Angelica acutiloba Kitagawa (Yamato Tohki). Immunology 1982, 47, 75–83. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada H.; Kiyohara H.; Jong-Chol C.; Otsuka Y. Studies on polysaccharides from Angelica acutiloba - IV. Characterization of an anti-complementary Arabinogalactan from the Roots of Angelica acutiloba Kitagawa. Mol. Immunol. 1985, 22, 295–304. 10.1016/0161-5890(85)90165-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitano N.; Nagasawa T. Improvement effect of drinking of Angelica acutiloba tea. Trace Nutrients Research 2016, 33, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Liao K. F.; Chiu T. L.; Huang S. Y.; Hsieh T. F.; Chang S. F.; Ruan J. W.; Chen S. P.; Pang C. Y.; Chiu S. C. Anti-cancer effects of radix Angelica sinensis (Danggui) and N-butylidenephthalide on gastric cancer: Implications for REDD1 activation and mTOR inhibition. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 48, 2231–2246. 10.1159/000492641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imran M.; Rauf A.; Shah Z. A.; Saeed F.; Imran A.; Arshad M. U.; Ahmad B.; Bawazeer S.; Atif M.; Peters D. G.; Mubarak M. S. Chemo-preventive and therapeutic effect of the dietary flavonoid kaempferol: A comprehensive review. Phytother. Res. 2019, 33, 263–275. 10.1002/ptr.6227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese E. J.; Agathokleous E.; Calabrese V. Ferulic acid and hormesis: Biomedical and environmental implications. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2021, 198, 111544. 10.1016/j.mad.2021.111544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X.; Zhao W.; Zhu F.; Wu H.; Ding X.; Bai J.; Zhang X.; Qian M. Ligustilide inhibits the proliferation of non-small cell lung cancer via glycolytic metabolism. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2021, 410, 115336. 10.1016/j.taap.2020.115336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma M.; Kaushik P. Vegetable Phytochemicals: An Update on Extraction and Analysis Techniques. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2021, 36, 102149. 10.1016/j.bcab.2021.102149. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mitra S.; Naskar N.; Chaudhuri P. A review on potential bioactive phytochemicals for novel therapeutic applications with special emphasis on mangrove species. Phytomed. Plus 2021, 1, 100107. 10.1016/j.phyplu.2021.100107. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arumugham T.; Rambabu K.; Hasan S. W.; Show P. L.; Rinklebe J.; Banat F. Supercritical carbon dioxide extraction of plant phytochemicals for biological and environmental applications - A review. Chemosphere 2021, 271, 129525. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.129525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geow C. H.; Tan M. C.; Yeap S. P.; Chin N. L. A Review on Extraction Techniques and Its Future Applications in Industry. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2021, 123, 2000302. 10.1002/ejlt.202000302. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Putra N. R.; Rizkiyah D. N.; Abdul Aziz A. H.; Machmudah S.; Jumakir J.; Waluyo W.; Che Yunus M. A. Procy-anidin and proanthocyanidin extraction from Arachis hypogaea skins by using supercritical carbon dioxide: Optimization and modeling. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2021, 45, e15689 10.1111/jfpp.15689. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pimentel-Moral S.; Borras-Linares I.; Lozano-Sanchez J.; Arraez-Roman D.; Martinez-Ferez A.; Segura-Carretero A. Supercritical CO2 extraction of bioactive compounds from Hibiscus sabdariffa. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2019, 147, 213–221. 10.1016/j.supflu.2018.11.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wrona O.; Rafinska K.; Mozenski C.; Buszewski B. Supercritical fluid extraction of bioactive compounds from plant materials. J. AOAC Int. 2017, 100, 1624–1635. 10.5740/jaoacint.17-0232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ameer K.; Shahbaz H. M.; Kwon J. H. Green extraction methods for polyphenols from plant matrices and their byproducts: A review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2017, 16, 295–315. 10.1111/1541-4337.12253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fornari T.; Stateva R.P.. High Pressure Fluid Technology for Green Food Processing; Springer International Publishing: Switzerland, 2015; pp. 415. [Google Scholar]

- Yahia E.M.Fruit and Vegetable Phytochemicals: Chemistry and Human Health; 2nd Edition, John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, New Jersey, 2018; pp. 750. [Google Scholar]

- Saito É.; Sacoda P.; Paviani L. C.; Paula J. T.; Cabral F. A. Conventional and supercritical extraction of phenolic compounds from Brazilian red and green propolis. Sep. Sci. Technol. 2021, 56, 3119–3126. 10.1080/01496395.2020.1731755. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Idham Z.; Putra N. R.; Aziz A. H. A.; Zaini A. S.; Rasidek N. A. M.; Mili N.; Yunus M. A. C. Improvement of extraction and stability of anthocyanins, the natural red pigment from roselle calyces using supercritical carbon dioxide extraction. J. CO2 Util. 2022, 56, 101839. 10.1016/j.jcou.2021.101839. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; (inpress)

- Dias A. L. B.; de Aguiar A. C.; Rostagno M. A. Extraction of natural products using supercritical fluids and pressurized liquids assisted by ultrasound: Current status and trends. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2021, 74, 105584. 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2021.105584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osorio-Tobon J. F.; Carvalho P. I.; Rostagno M. A.; Petenate A. J.; Meireles M. A. A. Extraction of curcuminoids from deflavored turmeric (Curcuma longa L.) using pressurized liquids: process integration and economic evaluation. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2014, 95, 167–174. 10.1016/j.supflu.2014.08.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira G. L.; Maciel L. G.; Mazzutti S.; Barbi R. C. T.; Ribani R. H.; Ferreira S. R. S.; Block J. M. Sequential green extractions based on supercritical carbon dioxide and pressurized ethanol for the recovery of lipids and phenolics from Pachira aquatica seeds. J. Cleaner Prod. 2021, 306, 127223. 10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.127223. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dali I.; Aydi A.; Stamenic M.; Kolsi L.; Ghachem K.; Zizovic I.; Manef A.; Delgado D. R. Extraction of lyophilized olive mill wastewater using supercritical CO2 processes. Alex. Eng. J. 2022, 61, 237–246. 10.1016/j.aej.2021.04.088. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tan W. K.; Lee S. Y.; Lee W. J.; Hee Y. Y.; Abedin N. H. Z.; Abas F.; Chong G. H. Supercritical carbon dioxide extraction of pomegranate peel-seed mixture: Yield and modelling. J. Food Eng. 2021, 301, 110550. 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2021.110550. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arias J.; Martinez J.; Stashenko E.; del Valle J. M.; Nunez G. A. Supercritical CO2 extraction of pinocembrin from Lippia origanoides distillation residues. 2. Mathematical modeling of mass transfer kinetics as a function of substrate pretreatment. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2022, 180, 105458. 10.1016/j.supflu.2021.105458. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tomas-Barberan F.A.; Gil M.I.. Improving the Health-Promoting Properties of Fruit and Vegetable Products; 1st Edition, Woodhead Publishing Limited: Cambridge, 2008; pp. 257. [Google Scholar]

- Chen L.; Qi J.; Chang Y. X.; Zhu D.; Yu B. Identification and determination of the major constituents in Traditional Chinese Medicinal formula Danggui-Shaoyao-San by HPLC-DAD-ESI-MS/MS. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2009, 50, 127–137. 10.1016/j.jpba.2009.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y. H.; Charles A. L.; Kung H. F.; Ho C. T.; Huang T. C. Extraction of nobiletin and tangeretin from Citrus depressa Hayata by supercritical carbon dioxide with ethanol as modifier. Ind. Crops Prod. 2010, 31, 59–64. 10.1016/j.indcrop.2009.09.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li W.; Wang H.; Tang Y.; Guo J.; Qian D.; Ding A.; Duan J. A. The quantitative comparative analysis for main bio-active components in Angelica sinensis, Ligusticum chuanxiong, and the herb pair Gui-Xiong. J. Liq. Chromatogr. Relat. Technol. 2012, 35, 2439–2453. 10.1080/10826076.2011.633678. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Williams L. L.; Rubin J. B.; Edwards H. W. Calculation of Hansen solubility parameter values for a range of pressure and temperature conditions, including the supercritical fluid region. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2004, 43, 4967–4972. 10.1021/ie0497543. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pena-Pereira F.; Tobiszewski M.. The Application of Green Solvents in Separation Processes; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, 2017; pp. 192. [Google Scholar]